Abstract

With the continuous development of the medical field, drugs for cancer treatment are emerging in an endless stream. Many kinds of natural plant, animal, and microbial extracts and some specific screened and synthesized drugs have been identified in vitro with anticancer biological activity. However, the application of 90% of newly developed solid drugs with anticancer effects is limited because of their low solubility and low bioavailability. On the one hand, improving the solubility and bioavailability of drugs scientifically and rationally can enhance the therapeutic effect of cancer; on the other hand, it can promote the rational use of resources. At present, great progress has been made in the ways to improve the solubility of drugs, which play an important role in anticancer effects. We will focus on the classification and application of the solubilization methods of anticancer drugs and provide an effective guide for the next drug research in this review.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Cancer is considered to be the second most deadly disease [1,2]. At present, the main treatments for cancer are chemotherapy [3], radiotherapy [4], and surgery [5]. With the continuous in-depth research on various types of cancer mechanisms and treatment options, various drugs for cancer treatment have also been developing. It includes drugs targeting tumor tissue [6,7,8], drugs that inhibit DNA replication [9,10,11], anti-angiogenesis drugs [12,13,14], anti-metabolite drugs [15,16,17], immunomodulatory drugs [18,19,20], etc. Fortunately, more and more natural plants [21,22], animals [23], and microorganisms [24] which have good antitumor properties have been discovered for their medicinal value, which have good antitumor properties. Due to their natural advantages of high biocompatibility, low toxicity, and side effects, they have become potential candidate drug groups [25].

Although there are many types and quantities of anticancer drugs, the application of most anticancer drugs are facing a common problem, that is, poor solubility [26,27]. Common anticancer drugs, such as paclitaxel, camptothecin (CPT), curcumin, 5-fluorouracil, and doxorubicin, all have the same disadvantage of poor solubility, resulting in terrible therapeutic effect. The solubility of a drug is directly related to its absorption and bioavailability in the human body, which will affect the concentration and exposure of the drug in the blood when the drug enters the circulatory system. When the solubility of some anticancer drugs is very low, the anticancer effect of them will be terrible [28]. Based on this, related researchers are not only looking for new and more effective anticancer drugs but also working on ways to increase the solubility and bioavailability of anticancer drugs. At present, several commonly used solubilization methods for anticancer drugs mainly include the following, which are cyclodextrin inclusion technology, drug cocrystal technology, microenvironment pH regulation technology, solid dispersion technology, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) technology, micronization technology, and polymeric micelle (PM) technology. For these different kinds of solubilization methods of anticancer drugs, their mechanisms and latest applications will be summarized in this review, respectively.

2 Several different kinds of anticancer drug solubilization technologies

2.1 Cyclodextrin inclusion technology

Cyclodextrin is a cyclic oligosaccharide formed by starch degradation. As is shown in Figure 1, it is a chemical structure with a hydrophilic cavity outside and a hydrophobic cavity inside. It has the potential to encapsulate hydrophobic compounds and serve as drug carriers. Cyclodextrin inclusion technology can not only prolong the circulation time of drugs in the blood and improve the solubility of hydrophobic drugs but also control the drug release pattern and protect the degradation of drugs in vivo [29,30].

Schematic diagram of cyclodextrin inclusion technology.

Namgung et al. [31] designed a nanoassembly composed of polymeric cyclodextrin (pCD) and polymeric paclitaxel (pPTX). Among them, CD and PTX molecules were connected to the polymer backbone through degradable ester groups, and the polymer backbone was a copolymer of maleic anhydride, which reacted with the hydroxyl groups of CD or PTX to form esters bond and carboxyl group. The average radius of the nano-assembly in water was 54.6 ± 11.6 nm. And the nano-assembly comprised small ellipsoidal particles. The formation of carboxylate ions significantly improved the water dispersibility of the formed nanoassemblies, and the CD-wrapped PTX increased the drug loading and water solubility. This nanoassembly showed significant antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo on human colon cancer cells HCT-8. In addition, the AP-1 peptide was considered to target the interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor overexpressed on the cell surface of MDA-MB-231 (PTX-induced apoptosis-insensitive cancer cells), so the use of an AP-1 peptide targeting IL-4 to optimize the above-mentioned carrier system induced efficient cellular uptake, and the AP-1-conjugated pPTX/pCD nano-assembly was highly stable in blood and exhibited long-term antitumor effects for MDA-MB-231cells.

Due to the targeting and size effect of magnetic nanoparticles, Ramasamy et al. [32] coated a novel hybrid β-cyclodextrin-dextran conjugate with synthesized nickel ferrite (Ni1.04Fe1.96O4) nanoparticles and found that 88% of CPT could be loaded in the nanoparticles, and the release time of CPT was as long as 500 min. Moreover, the drug release rate would be faster when the environmental pH value drops from 7.4 to 6.0. They also found that the CPT magnetic nanoparticles had an obvious cytotoxic effect on HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and A549 cells with low LD50 values. The cytotoxicity was even higher than that of cisplatin and fluorouracil.

l-Asparaginase is a substance with anticancer activity, but its bioavailability is very low. Chitosan is a polysaccharide composed of 2-amino-2-deoxy-β-d-glucan linked by glycosidic bonds. It is a positively charged adhesive with biocompatibility, which can be decomposed into amino sugar and has no toxic side effects on the body. Studies have shown that chitosan can act as a penetration enhancer to open epithelial tight junctions so that nanobiocomposites containing chitosan can prolong the residence time of drugs at the absorption site. Based on this, Baskar and Sree [33] incorporated l-asparaginase into a nanobiocomposite synthesized using β-cyclodextrin and chitosan by vacuum freeze-drying method. The size was found to be 40–80 nm and was spherical in shape, and found that these nanocomposites had good anticancer activity against prostate cancer (PCa) and lymphoma cells.

Didymin, isosakuranetin-7-beta-rutinoside, a dietary glycoside commonly found in citrus, bergamot, orange, and other fruits or plants, which can act as adjuvant drugs for anticancer sensitization. However, its poor water solubility leads to low bioavailability in the human body. Yao et al. [34] prepared the inclusion complexes of didymin with β-cyclodextrin and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin by a saturated aqueous solution method, respectively. It improved the solubility and bioavailability of the drug and played a chemosensitizing effect and enhanced the cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin (DOX) for MCF-7/ADR cells with drug resistance.

DOX has been used in the systemic treatment of advanced liver cancer [35]. miR-122 can play a tumor-suppressive role in liver cancer by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell growth [36]. The repair of miR-122 can sensitize liver cancer cells to various chemotherapeutic drugs by regulating the expression of resistance-related genes [37]. Xiong et al. [38] synthesized novel copolymer nanoparticles that made hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) and pH-sensitive poly-2-(dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate (PDMAEMA) as arms and pCD as the core part. In these nanoparticles, PEG can form a surface shell to resist the adsorption of serum proteins and achieve the purpose of enhancing tumor site aggregation. The hydrophobic cavity of the CD at the core encapsulated DOX. The outer PDMAEMA chain interacted with miR-122 electrostatically to condense miR-122. The first released miR-122 directly induced apoptosis by regulating its downstream target genes. Then, miR-122 inhibited the expression of the ATP-binding cassette efflux transporter, resulting in an increase in the concentration of DOX, which played a potent cytotoxic effect on HepG2 cells (Table 1).

Summary of several kinds of anticancer drugs using cyclodextrin inclusion technology [31,32,33,34,38]

| Hydrophobic drug carrier | Anticancer drug | Treatment of cancer types |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclodextrin | Paclitaxel | MDA-MB-231cells |

| β-cyclodextrin | Camptothecin | HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and A549 cells |

| β-cyclodextrin | l-asparaginase | Prostate cancer and lymphoma cells |

| β-Cyclodextrin and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin | Didymin | MCF-7/ADR cells |

| Cyclodextrin | Doxorubicin | HepG2 cells |

2.2 Drug cocrystal technology

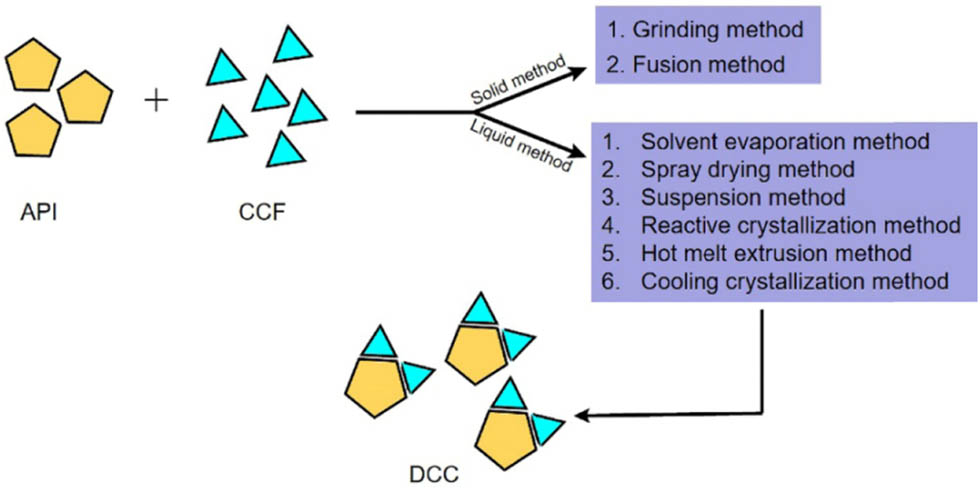

Studies have shown that cocrystals can change the physical and chemical properties of certain substances, such as crystallinity, melting point, and stability [39,40]. As shown in Figure 2, the mechanism of drug cocrystal technology to improve the water solubility of poorly soluble drugs is that the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the cocrystal former form a stable complex through non-covalent interactions (mainly hydrogen bonds) in a stoichiometric ratio, which will not affect its inherent biological activity but improve the solubility of the drug [41,42,43].

Schematic diagram of the preparation of drug co-crystals (DCC).

Curcumin is a pure natural substance with low solubility and low bioavailability extracted from the rhizome of turmeric with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-proliferative, anti-angiogenesis, and anti-cancer effects. Sanphui et al. [44] prepared a 1:1 cocrystal of curcumin with resorcinol and pyrogallol by liquid-assisted grinding, and the dissolution rates of curcumin-resorcinol and curcumin-pyrogallol were found to be faster than curcumin itself.

Niclosamide (NIC) can produce biological activity against lung cancer, ovarian cancer, PCa, and breast cancer by interfering with multiple intracellular signaling pathways. However, the drug is practically insoluble in water and soluble in small amounts in several solvents, such as ethyl acetate, diethyl ether, and tetrahydrofuran. Nicotinamide (NCT) is a type of vitamin B3 containing CONH2 and N aromatic functional groups. Cocrystals containing NCT may present (OH·O), (OH·NH2), or (OH·N aromatic) synthons, which are particularly versatile super molecular units for crystal engineering applications. Based on this, Ray et al. [45] prepared NIC–NCT drug cocrystals by spray drying technique. The drug particles were uniform and small in size. Compared with the pure drug, the solubility of the drug was increased to 14.8 times, and the anti-proliferative activity on human lung adenoma cell A549 was stronger.

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a cell cycle inhibitor, most of which are widely used in the treatment of solid tumors. At the same time, it can also be used in combination with other drugs to treat ovarian, gastric, and head and neck cancers. Zhang et al. [46] synthesized 5-FU–NCT cocrystals with a two-dimensional layered hydrogen-bonded structure at room temperature by solvent evaporation and liquid-phase-assisted milling, and the solubility of the cocrystal was found to be higher than that of 5-FU alone. The results showed that 5-Fu–NCM cocrystals had stronger lethality to HCT116 cells than 5-FU. In the related xenograft model, 5-FU–NCM cocrystals showed a stronger antitumor effect compared to API alone.

Apigenin (Agn) is a flavonoid widely found in common vegetables and fruits and has various pharmacological activities such as antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory. Daidzein (Dai) is one of the main isoflavones found in soybeans and other legumes and has biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, phytoestrogen, anticancer, and antioxidant. The bioavailability and clinical application of flavonoids are often limited because of their poor water solubility. Huang et al. [47] adopted the slow evaporation method and used theophylline (Thp) as an auxiliary agent to cocrystallize the above two substances, respectively. The solubility, intrinsic dissolution rate, and permeability of the synthesized Agn–Thp cocrystals and Dai–Thp cocrystals were found to be improved compared to the pure substances.

Quercetin (QUE) is a plant extract drug with anticancer, antibacterial, and antiviral activities. Because the low water solubility of QUE limits its clinical application, Smith et al. [48] synthesized four new QUE cocrystals through different preparation methods, and they were QUE:caffeine, QUE:caffeine:methanol, QUE:isonicotinamide, and QUE:theobromine dihydrate. These cocrystals were able to overcome the water insolubility of QUE, showing solubility to a certain extent (Table 2).

| Drug cocrystal | Anticancer drug | Treatment of cancer types |

|---|---|---|

| Resorcinol/pyrogallol | Curcumin | |

| Nicotinamide | Niclosamide | Human lung adenoma cell A549 |

| Nicotinamide | 5-Fluorouracil | HCT116 cells |

| Theophylline | Apigenin | |

| Theophylline | Daidzein | |

| Caffeine | QUE | |

| Caffeine:methanol | QUE | |

| Isonicotinamide | QUE | |

| Theobromine dihydrate | QUE |

2.3 Microenvironment pH regulation technology

The tumor microenvironment is mostly slightly acidic. In general, the pH of normal tissue cells is around 7.4, and the pH of the tumor microenvironment is between 5.5 and 6.5. As shown in Figure 3, some modified nano-drugs that are sensitive to the tumor environment have been designed. It is beneficial to the action of the drug at a specific site and the massive release of the drug. The pH-sensitive drug carrier includes liposomes [49], micelles [50], and dendrimers and drug-polymer conjugates [51].

Schematic diagram of nanomedicine-related microenvironment pH regulation technology. Due to the changes of microenvironment pH, the anticancer drug assemblies will disintegrate to release the anticancer drugs and play a role in their anticancer effects if they enter the tumor tissue.

Licciardi et al. [52] utilized a permanent hydrophilic block composed of 2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC) residues and pH-sensitive hydrophobic blocks comprising 2-(diisopropylamino)ethylmethacrylate residues to prepare the diblock copolymer. Then, folic acid (FA) was conjugated to the end of the MPC block to prepare FA-MPC-DPA copolymer. In the process of pH-induced self-assembly, two hydrophobic anticancer drugs, tamoxifen and PTX, were packaged in the center of the copolymer to form micelles. The novel assembled drug realized the solubilization effect of anticancer drugs and realized the function of stable existence at physiological pH and triggered drug release at lower pH such as 5. The FA groups made these micelles carry on targeted therapy for tumors containing FA receptors.

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has a very high incidence in lung cancer cases. It is a viable option for targeted therapy based on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Erlotinib (ERL) is an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which achieves the purpose of treating NSCLC by inhibiting various sensitizing EGFR mutations. However, its use is plagued by low water solubility, severe toxicity, drug resistance, and many other factors. Bevacizumab (BEV) is a recombinant monoclonal antibody against VEGF or VEGF receptor. Hyaluronic acid (HA) can specifically bind to a membrane protein CD44 that is overexpressed in the tumor area and has the function of being degraded by the abundant hyaluronidase in tumor tissue. Pang et al. [53] synthesized pH-sensitive HA nanomaterials by acylation of HA with adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH) and conjugation with CHO-PEG-NH2. Then, they prepared PH-sensitive lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPH NPs) of HA-ERL/BEV-LPH by ultrasonic method, realizing high-efficiency drug loading of ERL and BEV, achieving pH-controlled drug release at a lower pH such as 5.5 and tumor targeting, so HA-ERL/BeV-LPH can effectively inhibit the growth of tumor cells.

PTX can be used as a sensitizer for radiotherapy, but it is insoluble in water and requires a toxic solvent to dissolve it. Based on this, Jung et al. [54] introduced PTX into pH-sensitive block copolymer micelles, in which the pH-sensitive block was composed of poly(β-aminoester) and PEG components and found that the drug micelles released PTX faster under acidic conditions (pH 6.5) and were more stable under physiological conditions (pH 7.4). It provided the possibility that it may trigger the massive release of PTX in the acidic environment of the tumor site. A large number of experiments have also verified that these drug micelles had obvious radiosensitization effects on human NSCLC A549 cells, and these micelles combined with radiotherapy can significantly delay the growth of tumors.

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (BTZ) is the first-line treatment for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. Because the water solubility of BTZ is very poor, Kumar et al. [55] developed a liposome-based nanohybrid carrier dendron to deliver the proteasome inhibitor BTZ, that was, a nano-drug carrier composed of liposomes and dendrimers. The novel drug carrier not only achieved the solubilization and high-efficiency loading of BTZ but also exhibited a rapid release mode of BTZ at acidic pH such as 5.4 and had a significant inhibitory effect on lung cancer A549 cells. More importantly, because the dendrimers are rich in cationic groups, the traditional dendrimer drug carriers have high blood toxicity. But the blood toxicity of this new nanomedicine was smaller than that of the traditional dendrimer drug carriers.

Lignin is a natural biological material mainly extracted from the waste of the pulp and paper industry. Its relative molecular mass is small (<10 kD), and it has the potential to be used as a nano-drug carrier with a size effect. Histidine is a pH-responsive small molecule. Zhao et al. [56] prepared a new pH-responsive self-assembled nanomedicine based on aminated lignin-histidine conjugate and 10-hydroxycamptothecin. It was found that the particle size was not more than 40 nm, and the pH-responsive property achieved the contact release of the drug at the tumor site (pH 5.5) and showed an effective inhibitory effect on breast tumor growth (Table 3).

Summary of several kinds of anticancer drugs using microenvironment pH regulation technology [52,53,54,55,56]

| A pH-sensitive hydrophobic blocks | Anticancer drug | Treatment of cancer types |

|---|---|---|

| 2-(Diisopropylamino)ethylmethacrylate residues | Tamoxifen and paclitaxel | |

| Acylation of HA with ADH and conjugation with CHO-PEG-NH2 | ERL | NSCLC |

| Composed of poly(β-aminoester) and PEG components | Paclitaxel | Human non-small-cell lung cancer A549 cells |

| Composed of liposomes and dendrimers | Proteasome inhibitor BTZ | Lung cancer A549 cells |

| Histidine | 10-Hydroxycamptothecin | Breast tumor growth |

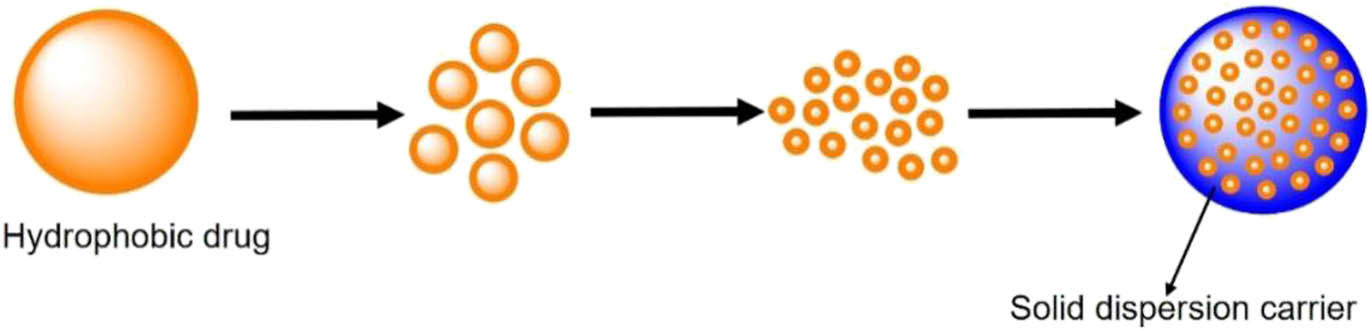

2.4 Solid dispersion technology

As is shown in Figure 4, solid dispersion technology refers to a method of dispersing a poorly soluble drug in a solid carrier with a high degree of uniform dispersion in a molecular, colloidal, microcrystalline, or amorphous state. In this process, substances with strong water solubility and hydrophilicity are often used as solid dispersion carriers. Common preparation methods of solid dispersions include melting method [57], solvent method [58], solvent-melting method [59], grinding method [60], and spray drying method [61]. At the same time, some new technologies have also been developed, such as hot melt extrusion technology [62], supercritical fluid technology [63], and electrostatic suspension method [64]. It increases the specific surface area of the drug and accelerates the dissolution rate of the drug, thereby improving the bioavailability of the drug through solid dispersion technology [65].

Schematic diagram of solid dispersion technology.

Lycopene is a natural hydrophobic compound extracted from tomatoes and other red fruits and vegetables. It has functions of antioxidant, anticancer, and hypolipidemic. Because its insolubility leads to low bioavailability in the human body, Chang et al. [66] prepared lycopene dropping pills based on PEG 6000 by melting method, which significantly improved the solubility and dissolution of lycopene, and the bioavailability of the optimized dropping pills were approximately improved 6 times.

Chrysin (5,7-dihydroxyflavone) is a natural flavonoid with various pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antihypertensive, antidiabetic, and anticancer. It is one of the most effective breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) inhibitors. To improve the water solubility of chrysin, Lee et al. [67] used a solvent method to prepare a solid dispersion containing chrysin with hydrophilic Brij®L4 and pH regulator aminoclay as a carrier. The solubility of chrysin can be increased by 13–53 times with the formula of different proportions, and the dissolution and release of the drug can be significantly improved. Meanwhile, chrysin solid dispersion exhibited higher cytotoxicity than chrysin in HT29 cells. The solid dispersion formulations of chrysin significantly improved oral exposure of topotecan in rats, while the untreated chrysin had no effect. Thereby, it exerted its effect of inhibiting BCRP-mediated efflux of anticancer drugs and improved the bioavailability of the anticancer drug topotecan.

Garcinia glycosides is chemically modified from the natural product gambogic acid, but it is also an insoluble antitumor drug. Chen et al. [68] used a solvent melting method to utilize a water-soluble carrier PEG as a solid dispersion of gambogic glycosides, which can improve the solubility, dissolution rate, and bioavailability of gambogic glycosides.

Luteolin, 3,4,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavonoid, which is a common phytochemical flavonoid found in plants such as celery, chrysanthemum, sweet pepper, carrot, onion leaves, and broccoli. To overcome the shortcomings of poor water solubility, Dong et al. [69] used different proportions of water and ethanol as dissolution media respectively to prepare complexes of lactose and luteolin through spray drying technology. The drug powder prepared was indeed effective to improve the solubility and dissolution rate of luteolin.

Athira et al. [70] prepared a water-soluble octenyl succinylated cassava starch-curcumin nanoformulation with higher bioavailability and anticancer potential by wet grinding method, with a size smaller than 50 nm, which overcame the water insolubility of curcumin and realized the slow-release characteristics of anti-cancer drugs, which increased the bioavailability of curcumin by about 71.27%. It is found to be non-toxic to L929 cells but showed anti-cancer potential to HeLa cells (Table 4).

| Hydrophobic drug carrier | Anticancer drug | Preparation method |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene glycol 6000 | Lycopene | Melting method |

| Brij®L4 and pH regulator aminoclay | Chrysin | Solvent method |

| Polyethylene glycol | Garcinia Glycosides | Solvent melting method |

| Lactose | Luteolin | Spray drying technology |

| Octenyl succinylated cassava starch | Curcumin | Wet grinding method |

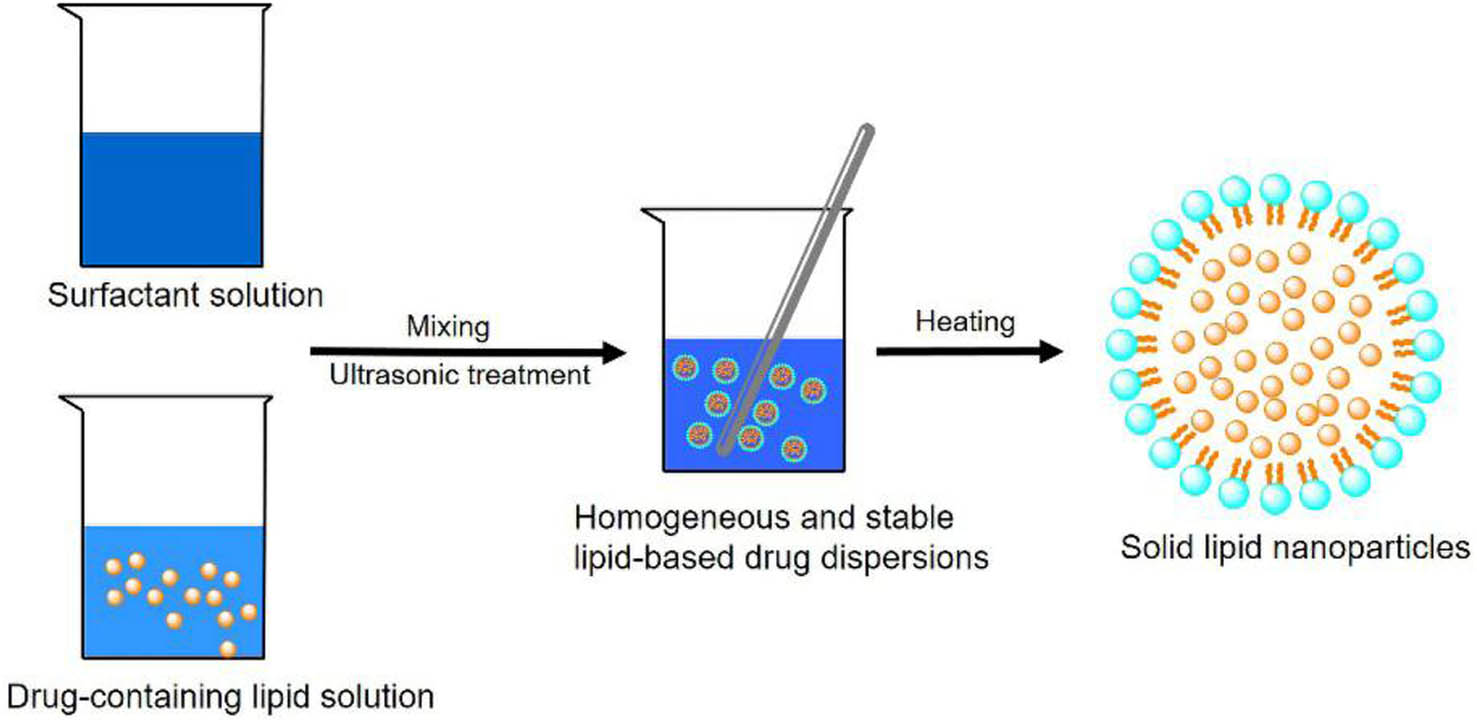

2.5 Solid lipid nanoparticle technology

As is shown in Figure 5, SLNs refer to prepared solid colloidal drug delivery system that encapsulates or embeds drugs in the lipid core with particle size in the range of 10–1,000 nm. The carriers of solid natural or synthetic lipids are usually lecithin, triacylglycerol, and so on. It has the advantage of low toxicity, good biocompatibility, and biodegradable [71]. The preparation methods of SLNs include thermal homogenization method, warm microemulsion method, emulsification-solvent evaporation, emulsification-solvent diffusion phase inversion, multiple emulsification method, microemulsion precipitation method, ultrasonic method, film shrinkage, etc. We should pay attention to several key process parameters such as high temperature, high pressure, toxic solvents, and high emulsifier concentrations in the process of preparing SLNs [72].

Schematic diagram of the preparation of SLNs by phacoemulsification.

PTX is effective in the treatment of various cancers, but its low water solubility (0.3 μg/mL) hinders its intravenous administration, thus limiting its clinical efficacy. Pedro et al. [73] used cholesterol, compritol, and medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) in appropriate ratios to prepare synthetic nanostructures lipid drug particles by hot melt homogenization and phacoemulsification in the presence of PTX. The novel lipid drug nanoparticles not only had a very high drug loading rate and encapsulation rate for PTX but also increased the accumulation of PTX in the tumor site and reduced the cytotoxic effect on normal cells (L929 and erythrocytes) while enhancing the cytotoxic and anti-clonogenic effects on breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231).

Zataria multiflora Bioss is a medicinal plant. Z. multiflora essential oil (ZMEO) has a variety of biological activities, including anti-cancer and antioxidant effects. However, the hydrophobicity of ZMEO is not conducive to human absorption. Alireza et al. [74] used high-pressure homogenization to prepare ZMEO-containing solid lipid nanoparticles (ZMSLN) through stearic acid, surfactants, and other materials. ZMSLN can significantly inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells MAD-MB-468 and melanoma cells A-375 cells, and the survival rate of both cells decreased to less than 13% after treatment with 75 μg/mL ZMSLN.

Aloe-emodin (AE) has significant antitumor activity against various tumors such as lung cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer, and many other cancers. Due to the low water solubility and low bioavailability of AE, Chen et al. [75] used a high-pressure homogenization method to prepare AE-containing SLNs through materials of glyceryl monostearate, surfactant Tween 80, etc., in a suitable ratio. The nanoparticles achieved the effect of sustained release of the nanomedicine. Compared with the AE solution, the new drug particles significantly enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and human liver cancer HepG2 cells and had no obvious toxicity on human breast epithelial MCF-10A cells.

CPT is an important topoisomerase I targeting anticancer drug, but its oral administration has many problems such as low bioavailability, serious toxic, and side effects. Du et al. [76] synthesized lipid-CPT conjugates by coupling CPT with palmitic acid via disulfide bonds, and then loaded the redox-sensitive lipid-CPT conjugates into SLNs. Stable nanoparticles were prepared by high shear homogenization and ultrasonic technology and materials such as glycerin monostearate and poloxamer 188. It was found that anticancer drugs from nanoparticles can be released through reduction reactions in a simulated tumor intracellular environment. In the Caco-2 cell model experiment, they had high anticancer activity and promoted the absorption of Caco-2 cells.

Myricetin (MYR) has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor effects. To overcome its poor water solubility, Nafee et al. [77] first prepared the complex of MYR and phospholipid Lipoid-S100 by a two-step method. It was then embedded in SLN of Gelucire-based and surfactant-free, followed by a carbohydrate carrier and spray-drying to prepare respirable microparticles. In this process, not only the drug loading of myricetin was increased but also its antitumor activity was enhanced in the human lung epithelial cancer cell line A549, and the preparation of inhalable microparticles also provided an effective way for the effective treatment of lung cancer (Table 5).

| Hydrophobic drug carrier | Anticancer drug | Preparation method | Treatment of cancer types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol, compritol, and MCT | Paclitaxel | Hot melt homogenization and phacoemulsification | MDA-MB-231 |

| Stearic acid, surfactants | Z. multiflora essential oil | High-pressure homogenization | Breast cancer cells MAD-MB-468 and melanoma cells A-375 cells |

| Glyceryl monostearate, surfactant Tween 80 | AE | High-pressure homogenization method | Human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and human liver cancer HepG2 cells |

| Glycerin monostearate and poloxamer 188 | Camptothecin | High shear homogenization and ultrasonic technology | Caco-2 cells |

| Gelucire based and surfactant free | Myricetin | Spray-drying method | Lung cancer |

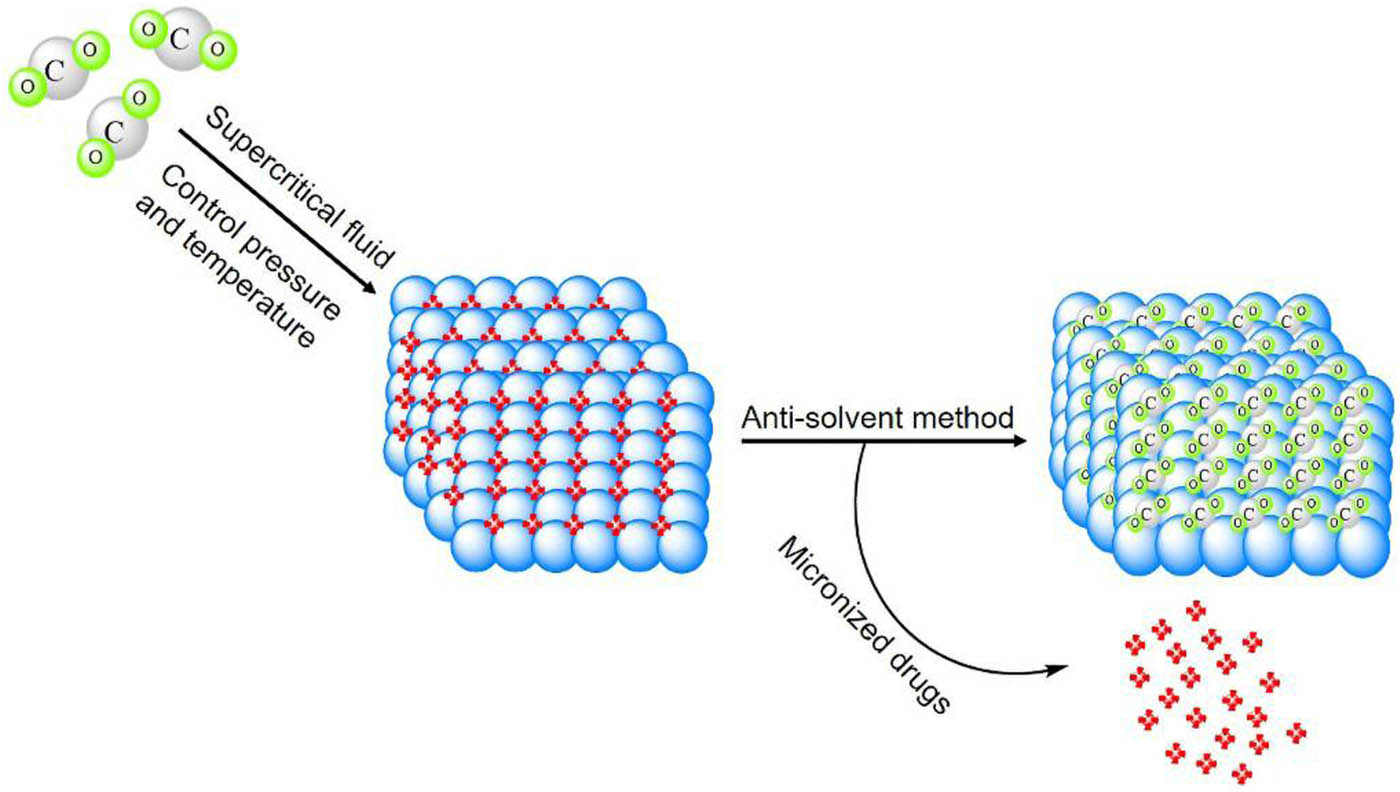

2.6 Micronization technology

Micronized drugs have the advantages of small particles, high surface reactivity, many active centers, high catalytic efficiency, and strong adsorption capacity. Since the drug micronization can increase the specific surface area of the drug, this method is also often used to change the physical structure of the compound, for example, changing the dissolution rate, solubility, and bioavailability of the drug. Traditional pulverization techniques mainly include jet pulverization, spray drying, freeze-drying, and solution crystallization, but these methods have problems such as large thermal stress, thermal degradation, wide particle size distribution, and more residual solvent in the final product. The new technology (as shown in Figure 6), which uses supercritical fluid to micronize the drug, overcomes the above difficulties [78,79,80].

Schematic diagram of the preparation of target drugs by anti-solvent method in supercritical fluid micronization technology.

El-Gendy and Berkland [81] obtained PTX nanosuspension by ultrasonicating the acetone solution of PTX, and slowly injecting different surfactants and cisplatin aqueous solution into the suspension to prepare a combined chemotherapy preparation. l-Leucine was added to the nanosuspension as a colloidal stabilizer to obtain nanoparticle agglomerates after homogenization, and finally freeze-dried to obtain corresponding freeze-dried powder. The dissolution rate of PTX was greatly improved through this method, and it also provided an effective way for local treatment of lung cancer.

dos Santos et al. [82] made luteolin into micronization through gas-antisolvent technology of supercritical fluid micronization technology, using CO2 as an antisolvent and acetone as an organic solvent by controlling pressure and temperature conditions. The micronization of luteolin reduced the average particle size by 10 times in this way. After verification by in vitro tests, it was found that the water solubility, dissolution rate, and antioxidant activity of luteolin have been improved.

Wang et al. [83] used ethylcellulose (EC) as the oil-phase polymer while gum Arabic as the emulsifier and water-phase encapsulation (wall material) to synthesize a novel oral drug delivery system to encapsulate curcumin. The curcumin-loaded oil-in-water emulsion was treated by ultrasonic emulsification first and then converted from liquid to solid by improved supercritical CO2-assisted atomization technology to obtain stable curcumin micronized oral drugs. It was found that this method can improve the solubility of the chemotherapeutic anticancer drug curcumin and improve the stability of the drug.

Artemisinin (ART) has anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects, but its clinical application is limited due to its poor water solubility. Zhang et al. [84] used the supercritical anti-solvent precipitation method and the rapid expansion supercritical solution method in the supercritical CO2 technology to prepare ART ultrafine fibers and ART microparticles, respectively, which can improve the anticancer effect of artemisinin on 4T1 cells and U87 cells.

Disulfiram (DSF) is a copper-dependent antitumor drug. To overcome the problems of poor water solubility and poor stability, Tang et al. [85] prepared DSF micronized particles and DSF-Cu complex by supercritical solution rapid expansion process, using polyvinylpyrrolidone and methoxy b-poly(l-lactide) 2000-poly(ethylene glycol) 2000 solution to coat these complexes to improve their suspending ability. This novel nano-powder improved the dissolution rate of DSF, and the DSF-Cu complex significantly enhanced the anti-tumor effect of DSF in MDA-MB-231 cells (Table 6).

| Preparation method | Anticancer drug | Treatment of cancer types |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic emulsification and freeze drying method | Paclitaxel | Lung cancer |

| Gas-antisolvent technology | luteolin | |

| Ultrasonic emulsification and supercritical CO2-assisted atomization technology | Curcumin | |

| Supercritical anti-solvent precipitation method and the rapid expansion supercritical solution method | Artemisinin | 4T1 cells and U87 cells |

| Supercritical solution rapid expansion method | Disulfiram | MDA-MB-231 cells |

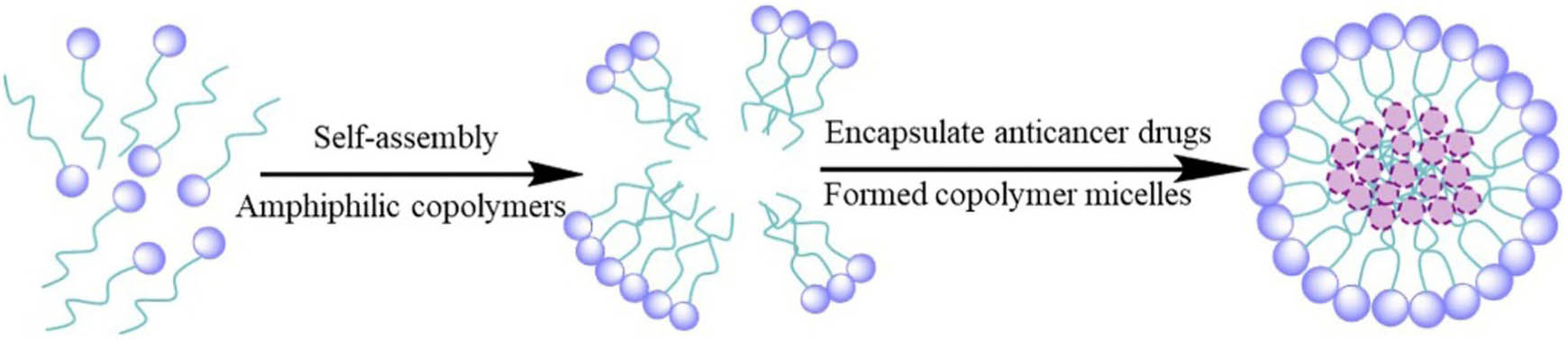

2.7 PM technology

As shown in Figure 7, the PM technology refers to the formation of micelles through the self-assembly of amphiphilic copolymers, which act as carriers of poorly soluble drugs to encapsulate the hydrophobic drugs in the hydrophobic micelle core to improve the water solubility of poorly soluble drugs. When micelles are used as drug carriers, they have the advantages of size effect, thermodynamic stability, long cycle time, and easy production [86].

Schematic diagram of PM technology.

Flutamide (Flt) is an effective drug for the treatment of PCa. Its bioavailability after oral administration is low due to its poor solubility in aqueous solution and low permeability. Casein (CAS) is a major milk protein that is biodegradable and does not elicit an immune response. Since CAS is an amphiphilic substance with hydrophobic or hydrophilic amino acid residues, Elzoghby et al. [87] used genipin to cross-link 28 CAS micelles and successfully prepared novel CAS micelles of Flt by freeze-drying and significantly prolonged the circulation of Flt in plasma.

Tetronic® 1307 is a hydrophilic ethylene oxide (EO)–propylene oxide star block copolymer with long EO chains (total MW-18000 and 70% EO). Patidar et al. [88]added glucose during the formation of micelles to promote the self-assembly of micelles, while curcumin and QUE-loaded micelles showed improved controlled release kinetics and cytotoxicity in CHO-K1 cell lines.

Numerous studies have shown that high concentrations of nitric oxide (NO) have significant anti-tumor effects, and can also improve the sensitivity of chemotherapy. Furoxan is a type of thiol-based heterocyclic NO donor, which can interact with glutathione transferase in the human body and be catalyzed to generate NO, thereby exerting anti-cancer effect. Li et al. [89] reacted furan with valproyl chloride to form a mixed acid anhydride, which was then coupled with mPEG-PLA to obtain mPEG-PLA-NO ester, which was purified by filtration in cold ethanol and freeze-dried. Then, the PLA-NO polymer and PTX were dissolved in solution to form water micelles, and finally, freeze-dried to obtain PTX (NO/PTX) micelles, during which the solubility and anticancer activity (HCT116, SW480 and SGC-7901 cells) of PTX were improved.

Halofuginone hydrobromide (HF) is a synthetic analog of the naturally occurring quinazolinone alkaloid febrifugine, which has potential therapeutic effects against breast cancer. However, its poor water solubility limits its clinical application. d-α-Tocopherol PEG 1000 succinate (TPGS) is a water-soluble derivative of vitamin E. Based on this, Zuo et al. [90] prepared HF-loaded TPGS polymer micelles by thin-film sonication. It not only had small size, narrow distribution, good stability, and sustained-release behavior but also had a stronger inhibitory effect on triple-negative breast cancer than free HF.

LA67 is a derivative of triptolide with strong antitumor activity, but its clinical application is limited by its poor water solubility. Cui et al. [91] prepared LA67-loaded polymer micelles by thin-film hydration using mPEG2000-PLA1300 copolymer as a carrier. The preparation was completely dispersed in an aqueous solution and showed slow and sustained LA67 release. This drug micelle can inhibit tumor growth and distant organ metastasis more than free LA67 in C26 cells (Table 7).

| Hydrophobic drug carrier | Anticancer drug | Treatment of cancer types |

|---|---|---|

| Casein and genipin | Flutamide | |

| Tetronic® 1307 and glucose | Curcumin and quercetin | |

| mPEG-PLA-NO ester | Paclitaxel | HCT116, SW480, and SGC-7901 cells |

| D-α-tocopherol PEG 1000 succinate | Halofuginone hydrobromide | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| mPEG2000-PLA1300 copolymer | LA67 | C26 cells |

2.8 Other technologies

In addition, there are many effective ways to deliver drugs. Nanorobots are a relatively efficient way to transport drugs in recent years. Pacheco et al. [92] used polycaprolactone (PCL), iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4), and coated polyethyleneimine (PEI) micelles containing the anticancer drug DOX to make microspheres. The magnetic microrobots are based on PCL and incorporate magnetic nanoparticles that allow them to navigate biological media in a guided, controlled way through the application of a transversal rotating magnetic field. PCL-Fe3O4/PEI@DOX magnetic microrobots release DOX through the enzymatic action of lipase, naturally overexpressed in pancreatic cancer cells, which then kills the cancer cells. Khezri et al. [93] made machines contain reduced nanographene oxide (n-rGO) as an outer layer and platinum (Pt) as a catalytic inner layer. n-rGO/Pt micromachines were loaded with DOX by physical adsorption (via π–π stacking) with high loading efficiency. It was found that electron injection into DOX@n-rGO/Pt micromachines leads to the controlled release of DOX from micromachines in motion within only a few seconds. An in vitro study confirms this efficient release mechanism in the presence of cancerous cells. The n-rGO/Pt micromotor enables effective DOX release, enhances the therapeutic efficiency, and reduces the side toxicity toward the healthy tissue.

Meanwhile, wrapping drugs in a hydrogel system is also a good way to deliver drugs. Almawash et al. [94] prepared a simple stable hydrogel system by using the polymerized β-cyclodextrin and a branched PEG end-capped with a hydrophobic moiety of cholesterol in a simple inclusion reaction. Then, a rapid rehydration process with PBS was utilized in the incorporation and careful distribution of a 5-FU/methotrexate mixture into the prepared hydrogel base. The in vitro release results and in vivo studies showed the utility of the constructed hydrogel system for loading and controlling the sustained release behavior of both the two investigated chemotherapies for more than 4 weeks. It demonstrated its efficacy and novelty in loading and delivering important chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of breast cancer. Abdellatif et al. [95] prepared hydrogels with chitosan, β-glycerophosphate, and Pluronic F127 copolymers loaded with 5-FU. The prepared hydrogel system showed an extended and controlled drug release (30 days) with good physicochemical properties. It has a good therapeutic effect on breast cancer.

Nano-based systems can be used to deliver active drugs to specific parts of the body. In the last few decades, a new generation of nanoparticles has emerged, which can overcome most of the challenges in drug delivery, such as low water solubility and low bioavailability. These include nanocrystals, liposomes, lipid nanoparticles, PEG polymer nanoparticles, protein nanoparticles, and metal nanoparticles [96]. We have talked about a lot of different kinds of nanoparticles. The nanomedicine system based on this method is still developing and improving. Cetuximab (CTX) is known to have cytotoxic effects on several human cancer cells in vitro; however, CTX is poorly water soluble. Abdellatif et al. [97] developed (PEG-4000) polymeric nanoparticles (PEGNPs) loaded with CTX using the solvent evaporation technique and evaluated their in vitro cytotoxicity and anticancer properties against human lung (A549) and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells. The results indicated that CTX-PEGNP was an improved formulation than CTX alone to induce apoptosis and DNA damage and inhibit cell proliferation through the downregulation of P21 and stathmin-1 expression. Abdellatif et al. [98] conjugated CTX and octreotide (OCT) using a solvent evaporation method. And the conjugated CTX-OCT was then loaded onto Ca-alginate beads (CTX-OCT-Alg). Alginate was used to coat CTX to facilitate delivery to the gastrointestinal tract. The in vitro release results showed that CTX-OCT-Alg had a low drug release rate after 1 h in 0.1 HCl 1.2 pH, while in phosphate buffer pH 7.4, all drug contents were released over 5 h. The results demonstrate CTX-OCT-Alg beads to have excellent gastro-resistant activity and efficiently deliver anti-cancer drugs to the higher pH environments of the colon with higher antiproliferative activity compared to free drugs (HCT-116, HepG-2, and MCF-7). Etoposide (ETO) has an anticancer activity used for treating various tumors, such as lymphoma, small-cell lung cancer, and leukemia; however, its aqueous solubility and permeability is insufficient. EC is a polymer that pH dependent with a high solubility at pH 7.4. It is a suitable polymer for loading acid-sensitive drugs or drugs that harm the stomach. Abdellatif et al. [99] improve the solubility of ETO–EC microparticles using the freeze-drying technique. The freeze-dried ET–ETO microparticles provide significant antiproliferative activity compared to free ETO against the tested cell lines (MCF-7 and Caco-2). The ETO coating with EC enhanced the activity of ETO by forming a barrier layer. EC microparticles loaded with ETO can target a specific area in the gastrointestinal tract at pH 7.4 with potential anticancer activity.

3 Conclusion

At present, most of the drugs are lipophilic and their water solubility are not ideal [100]. Poor drug solubility not only slows drug absorption but also leads to mucosal toxicity in the gastrointestinal tract due to drug deposition [101]. At the same time, it is not enough to consider the solubility of improvement in terms of the effectiveness of cancer drugs. We also need to consider the biocompatibility of drugs, the selectivity of tumor tissue, and the toxic and side effects of drugs. Although there are many ways to improve the water solubility and bioavailability of drugs, their effects still need to be strengthened, and we still have a long way to go for the solubilization of anticancer drugs. Although the following method can improve the anticancer drugs’ solubilization to a certain extent, there are still some shortcomings about them.

For cyclodextrin inclusion technology, while improving drug solubility, cyclodextrin inclusion complexes can form complexes with cell membrane components (such as cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, and proteins), thereby changing the lipid barrier, to enhance the absorption of the drug. This method can improve the chemical stability of the drug through the inclusion effect, and the oxidation, photolysis, and hydrolysis of some drugs are significantly weakened after the inclusion of some drugs by cyclodextrin. However, the solubility of natural cyclodextrin is very poor, and most of the currently used cyclodextrin derivatives are synthesized from β-cyclodextrin. In general, the complexation efficiency of this method is relatively low, so a relatively large amount of cyclodextrin is usually required to achieve the solubilization effect of the drug. For some cyclodextrin complexes, dilution of the system may lead to precipitation. The crystal forms of diverse inclusion complexes are very different, so the dissolution rates are also different, and the polymorphism of the drug is also one of the key reasons that affect its physicochemical properties and therapeutic effect [102]. Studies have also shown that cyclodextrins may have nephrotoxicity in the human body [103]. Drug co-crystal technology is particularly beneficial for drugs that are easily degraded under harsh acidic or basic conditions or drugs that lack strong acid and basic sites. Before using the co-crystal method, we can combine molecular simulation technology to make a preliminary judgment on selecting drug molecules, which can save time and cost. However, some drug particles prepared by DCC technology are not very stable in aqueous solution, and some are even insufficient in purity due to improper methods or are easy to crystallize [104]. Drugs designed based on changes in the pH of the microenvironment can not only achieve the aim of sustained release and targeted effects but also these drugs are not easily degraded. However, the body is a complex process, and the environment of the gastrointestinal tract is also acidic, so such drugs are easily released and absorbed here, which will affect the therapeutic effect of cancer; therefore, we should take into account the unique targeting of the tumor when designing such drugs. At the same time, the microenvironment pH regulation technology also needs to consider whether the pH-sensitive substances have no toxic and side effects and whether they can be metabolized by the human body [105]. Solid dispersion technology has the advantages of a simple preparation method and good reproducibility. Moreover, as an intermediate, the solid dispersion can be made into various dosage forms such as capsules, tablets, pellets, drop pills, ointments, suppositories, and injections according to actual needs. However, the use of solid dispersion technology to prepare solid dispersion drugs is generally only suitable for drugs with small doses. The common disadvantage of solid dispersion technology is that the stability of the drug dispersion state is not good, and long-term storage is prone to aging. That is, after a long period of storage, the solid dispersion may experience increased hardness, precipitation of crystallization, crystal coarsening, and decreased drug dissolution [106]. For the SLN technology, the liposome has good cell affinity and tissue compatibility, which can reduce the side effects on the body, and the prepared drugs have good dispersibility, which is beneficial to the body’s absorption and improves the drug’s bioavailability efficacy. However, it has the disadvantages of difficult industrial production, high price and unstable drug properties. And SLN technology also faces many problems that need to be solved, such as low drug loading, gelation, and drug precipitation [107]. For micronization technology, drugs are processed into micron or even nano-scale powders through ultra-fine powder technical means such as grinding and dispersion, which can significantly improve the bioavailability of drugs. However, when the drug powder is too fine, it will also amplify the toxic and side effects of the drug. Therefore, we should strictly control the particle size range of the drug particles when using micronization technology. The difficulty faced by micronization technology is that it has high technical requirements, and there are some tough issues like low yield, low purity, and many impurities [108]. Generally speaking, for the polymer micelle method, the structure of micelles is very simple, and the micelles are usually formed by self-assembly in an aqueous solution. The preparation process is very simple, and the formed system is generally relatively stable. Moreover, when the particle size of the micelle is in the range of 10–100 nm, it is not easy to be recognized and captured by the endothelial reticulum system in the blood circulation system, so it can exist stably in the blood for a long time. At the same time, the most amazing thing about this method is that passive targeting of tumor sites is achieved through the enhanced permeability and retention effect for PMs. Generally, the drug carrier with small particle size also help to improve the production yield. In the production process, filter elements with 0.45- and 0.22-μm pore size can be used to control the sterility of the drug. However, it has high requirements for concentration and temperature. For example, if the solution is diluted, the micelles will be easily degraded [109].

Moreover, the solubilization research of traditional anticancer drugs not only faces a long research cycle but also is not friendly to limited resources. Computational methods such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation can effectively solve the problems of drug screening and functional prediction in drug design and development [110,111,112]. For example, we can use it to judge whether the two substances have the property of enhancing the water solubility of the target drug after being complexed together or to predict the absorption effect of cells on the drug in the in vivo environment through simulation. These calculation methods can help us in the solubilization process and have a clear target for the drug you want to study before research, reduce the time of trial, and speed up drug development. Based on this, we can even develop a new program to perform unified model calculations on similar compounds, sum up the corresponding laws, and find their commonalities and characteristics.

In addition, we should not only consider water solubility in the treatment of cancer. It is hoped that in the future, targeted therapy [113], immunotherapy [114], and combination therapy [115] should also be considered to design a more scientific and comprehensive anti-cancer drug when improving the solubilization of anticancer drugs. It means that we should comprehensively think about multiple factors that affect treatment, for example, whether there is interaction between various substances, whether the combined treatment function can be achieved, and whether the drug can maximize the multifunctional treatment while reducing the damage to the human body. I believe that with the continuous development of science, the truth of various drugs will be gradually revealed, and cancer will be conquered 1 day.

Acknowledgments

The author is extremely grateful to Gao Feng for his assistance in collecting information.

-

Funding information: This project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. T2241002, 32271298), the opening grants of the Innovation Laboratory of Terahertz Biophysics (No. 23-163-00-GZ-001-001-02-01), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (No. 23QA1404200), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFA1200402), and Wenzhou Institute of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (WIUCASQD2021003, WIUCASQD20210011).

-

Author contributions: Feng Zhang, Xuewen Jin, and LiPing Wang guided and reviewed the manuscript, providing numerous valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript. Min Wu completed a lot of research in related fields and completed the writing of the manuscript. Xiaofang Li searched and collected relevant references. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Pérez-Herrero E, Fernández-Medarde A. Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: Drug nanocarriers, the future of chemotherapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;93:52–79.10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.03.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca-Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.10.3322/caac.21492Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Dutt R, Garg V, Khatri N, Madan AK. Phytochemicals in anticancer drug development. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2019;19(2):172–83.10.2174/1871520618666181106115802Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Jackson M, Falzone N, Vallis K. Advances in anticancer radiopharmaceuticals. Clin Oncol. 2013;25(10):604–9.10.1016/j.clon.2013.06.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Igarashi T, Okamoto K, Teramoto K, Kaku R, Ishida K, Ueda K, et al. Clinical outcome of posterior fixation surgery in patients with vertebral metastasis of lung cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:770–4.10.3892/mco.2017.1199Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Maleki M, Aidy A, Karimi E, Shahbazi S, Safarian N, Abbasi N. Synthesis of a copolymer carrier for anticancer drug luteolin for targeting human breast cancer cells. J Tradit Chin Med. 2019;39(4):474–81.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Skalickova S, Docekalova M, Stankova M, Uhlirova D, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Fernandez C, et al. Zinc modified nanotransporter of anticancer drugs for targeted therapy: biophysical analysis. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2019;19(5):2483–8.10.1166/jnn.2019.15870Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Hjk A, Jyl B, Thk CDG, Jhp B, Jmo A. Radioisotope and anticancer agent incorporated layered double hydroxide for tumor targeting theranostic nanomedicine - ScienceDirect. Appl Clay Sci. 2020;186(1):105454–62.10.1016/j.clay.2020.105454Search in Google Scholar

[9] Huang Q, Wang X, Chen A, Zhang H, Yu Q, Shen C, et al. Design synthesis and anti-tumor activity of novel benzothiophenonaphthalimide derivatives targeting mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) G-quadruplex. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;201:115062.10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Lisi L, Chiavari M, Ciotti GMP, Lacal PM, Navarra P, Graziani G. DNA inhibitors for the treatment of brain tumors. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2020;16(3):195–207.10.1080/17425255.2020.1729352Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Liu Y, Zhang J, Feng S, Zhao T, Li Z, Wang L, et al. A novel camptothecin derivative 3j inhibits Nsclc proliferation via induction of cell cycle arrest by topo I-mediated DNA damage. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2019;19(3):365–74.10.2174/1871520619666181207102037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Gold M, Khler L, Lanzloth C, Andronache I, Schobert R. Synthesis and bioevaluation of new vascular-targeting and anti-angiogenic thieno[23-d]pyrimidin-4(3H)-ones. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;189:112060.10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112060Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Cho SM, Kwon HJ. Acid ceramidase an emerging target for anti-cancer and anti-angiogenesis. Arch Pharmacal Res. 2019;42:232–43.10.1007/s12272-019-01114-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Ji H, Li Y, Jiang F, Wang X, Zhang J, Shen J, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta/SMAD signal by MiR-155 is involved in arsenic trioxide-induced anti-angiogenesis in prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1541–9.10.1111/cas.12548Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Sukjoi W, Ngamkham J, Attwood PV, Jitrapakdee S. Targeting cancer metabolism and current anti-cancer drugs. Rev N Drug Targets Age-Relat Disord. 2021;1286:15–48.10.1007/978-3-030-55035-6_2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Rom K, Ayelet E. Arginine and the metabolic regulation of nitric oxide synthesis in cancer. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11(8):dmm033332.10.1242/dmm.033332Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Bunik VI. Interplay between thiamine and p53/p21 axes affects antiproliferative action of cisplatin in lung adenocarcinoma cells by changing metabolism of 2-oxoglutarate/glutamate. Front Genet. 2021;12:658446.10.3389/fgene.2021.658446Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Patra AR, Hajra S, Baral R, Bhattacharya S. Use of selenium as micronutrients and for future anticancer drug: a review. Nucl. 2019;63:107–18.10.1007/s13237-019-00306-ySearch in Google Scholar

[19] Deng Q, Li X, Fang C, Li X, Zhang J, Xi Q, et al. Cordycepin enhances anti-tumor immunity in colon cancer by inhibiting phagocytosis immune checkpoint CD47 expression. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;107:108695.10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108695Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Shi R, Zhao K, Wang T, Yuan J, Zhang D, Xiang W, et al. 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine potentiates anti-tumor immunity in colorectal peritoneal metastasis by modulating ABC A9-mediated cholesterol accumulation in macrophages. Theranostics. 2022;12(2):875.10.7150/thno.66420Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mohamed A, Karima S, Nadia O. The use of medicinal plants against cancer: An ethnobotanical study in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra Region in Morocco. Eur J Integr Med. 2022;52:102137.10.1016/j.eujim.2022.102137Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kumar P, Sharma R, Garg N. Withania somnifera-A magic plant targeting multiple pathways in cancer related inflammation. Phytomedicine. 2022;101:154137.10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154137Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Verma MK, Xavier F, Verma YK, Sobha K. Evaluation of cytotoxic and anti-tumor activity of partially purified serine protease isolate from the Indian earthworm Pheretima posthuma. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3(11):896–901.10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60175-6Search in Google Scholar

[24] Wang YN, Meng LH, Wang BG. Progress in research on bioactive secondary metabolites from deep-sea derived microorganisms. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(12):614.10.3390/md18120614Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Pathak K, Pathak MP, Saikia R, Gogoi U, Sahariah JJ, Zothantluanga JH, et al. Cancer chemotherapy via natural bioactive compounds. Curr Drug Discovery Technol. 2022;19(4):e310322202888.10.2174/1570163819666220331095744Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ackova DG, Smilkov K, Bosnakovski D. Contemporary formulations for drug delivery of anticancer bioactive compounds. Recent Pat Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery. 2019;14(1):19–31.10.2174/1574892814666190111104834Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Wei W, Yue ZG, Qu JB, Yue H, Su ZG, Ma GH. Galactosylated nanocrystallites of insoluble anticancer drug for liver-targeting therapy: an in vitro evaluation. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:589–96.10.2217/nnm.10.27Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Herbrink M, Groenland SL, Huitema A, Schellens J, Beijnen JH, Steeghs N, et al. Solubility and bioavailability improvement of pazopanib hydrochloride. Int J Pharm. 2018;544(1):181–90.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.04.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Gèze A, Chau LT, Choisnard L, Mathieu JP, Wouessidjewe D. Biodistribution of intravenously administered amphiphilic β-cyclodextrin nanospheres. Int J Pharm. 2007;344(1–2):135–42.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.06.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Hirayama F, Minami K, Uekama K. Design and evaluation of colon-specific drug delivery system based on cyclodextrin conjugates. Proceedings of the Ninth International Symposium on Cyclodextrins; 1999. p. 247–50.10.1007/978-94-011-4681-4_57Search in Google Scholar

[31] Namgung R, Lee YM, Kim J, Jang Y, Lee BH, Kim IS, et al. Poly-cyclodextrin and poly-paclitaxel nano-assembly for anticancer therapy. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3702.10.1038/ncomms4702Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Ramasamy SVMV, Enoch I, Rajakumar SDRJ. Polymeric cyclodextrin-dextran spooled nickel ferrite nanoparticles: Expanded anticancer efficacy of loaded camptothecin - ScienceDirect. Mater Lett. 2020;261:127114–23.10.1016/j.matlet.2019.127114Search in Google Scholar

[33] Baskar G, Sree NS. Synthesis characterization and anticancer activity of β-cyclodextrin-Asparaginase nanobiocomposite on prostate and lymphoma cancer cells. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2019;55:101417.10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101417Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yao Q, Lin MT, Lan QH, Huang ZW, Zheng YW, Jiang X, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of didymin cyclodextrin inclusion complexes: characterization and chemosensitization activity. Drug Delivery. 2019;27(1):54–65.10.1080/10717544.2019.1704941Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Olweny CL, Toya T, Katongole‐Mbidde E, Mugerwa J, Kyalwazi SK, Cohen H. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with adriamycin. Preliminary communication. Cancer. 1975;36(4):1250–7.10.1002/1097-0142(197510)36:4<1250::AID-CNCR2820360410>3.0.CO;2-XSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Xu J, Zhu XM, Wu LJ, Yang R, Yang ZR, Wang QF, et al. MicroRNA-122 suppresses cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by directly targeting Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Liver Int. 2012;32:752–60.10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02750.xSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Xu Y, Feng X, Ma L, Shan J, Shen J, Yang Z, et al. MicroRNA-122 sensitizes HCC cancer cells to adriamycin and vincristine through modulating expression of MDR and inducing cell cycle arrest. Cancer Lett. 2011;310(2):160–9.10.1016/j.canlet.2011.06.027Search in Google Scholar

[38] Xiong Q, Bai Y, Shi R, Wang J, Xu W, Zhang M, et al. Preferentially released miR-122 from cyclodextrin-based star copolymer nanoparticle enhances hepatoma chemotherapy by apoptosis induction and cytotoxics efflux inhibition. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(11):3744–55.10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.03.026Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ning S, Zaworotko MJ. The role of cocrystals in pharmaceutical science. Drug Discovery Today. 2008;13(9–10):440–6.10.1016/j.drudis.2008.03.004Search in Google Scholar

[40] Schultheiss N, Newman A. Pharmaceutical cocrystals and their physicochemical properties. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9(6):2950–67.10.1021/cg900129fSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Cheney ML, Weyna DR, Shan N, Hanna M, Wojtas L, Zaworotko MJ. Coformer selection in pharmaceutical cocrystal development: A case study of a meloxicam aspirin cocrystal that exhibits enhanced solubility and pharmacokinetics. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(6):2172–81.10.1002/jps.22434Search in Google Scholar

[42] Good DJ, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Solubility advantage of pharmaceutical cocrystals. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9(5):2252–64.10.1021/cg801039jSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Parwati RD. Challenges and progress in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs co-crystal development. Molecules. 2021;26:4185–222.10.3390/molecules26144185Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Sanphui P, Goud NR, Khandavilli U, Nangia A. Fast dissolving curcumin cocrystals. Cryst Growth Des. 2011;11(9):4135–45.10.1021/cg200704sSearch in Google Scholar

[45] Ray E, Vaghasiya K, Sharma A, Shukla R, Verma RK. Autophagy-inducing inhalable co-crystal formulation of niclosamide-nicotinamide for lung cancer therapy. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21:260.10.1208/s12249-020-01803-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Zhang Z, Yu N, Xue C, Gao S, Han S. Potential anti-tumor drug: co-crystal 5-fluorouracil-nicotinamide. ACS Omega. 2020;5(26):15777.10.1021/acsomega.9b03574Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Huang S, Xue Q, Xu J, Ruan S, Cai T. Simultaneously improving the physicochemical properties dissolution performance and bioavailability of apigenin and daidzein by co-crystallization with theophylline. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(9):2982.10.1016/j.xphs.2019.04.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Smith AJ, Kavuru P, Wojtas L, Zaworotko MJ, Shytle RD. Cocrystals of quercetin with improved solubility and oral bioavailability. Mol Pharm. 2011;8(5):1867–76.10.1021/mp200209jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Chen D, Jiang X, Liu J, Jin X, Zhang C, Ping Q. In vivo evaluation of novel pH-sensitive mPEG-Hz-Chol conjugate in liposomes: pharmacokinetics tissue distribution efficacy assessment. Artif Cell Blood Substitutes Biotechnol. 2010;38(3):136–42.10.3109/10731191003685481Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Salmaso S, Bersani S, Pirazzini M, Caliceti P. pH-sensitive PEG-based micelles for tumor targeting. J Drug Target. 2011;19(4):303–13.10.3109/1061186X.2010.499466Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Kim JK, Garripelli VK, Jeong UH, Park JS, Repka MA, Jo S. Novel pH-sensitive polyacetal-based block copolymers for controlled drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2010;401(1–2):79–86.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.08.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Licciardi M, Giammona G, Du J, Armes SP, Tang Y, Lewis AL. New folate-functionalized biocompatible block copolymer micelles as potential anti-cancer drug delivery systems. Polymer. 2006;47(9):2946–55.10.1016/j.polymer.2006.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[53] Pang J, Xing H, Sun Y, Feng S, Wang S. Non-small cell lung cancer combination therapy: Hyaluronic acid modified epidermal growth factor receptor targeted pH sensitive lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles for the delivery of erlotinib plus bevacizumab. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;125:109861.10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109861Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Jung J, Kim MS, Park SJ, Chung HK, Choi J, Park J, et al. Enhancement of radiotherapeutic efficacy by paclitaxel-loaded pH-sensitive block copolymer micelles. J Nanomater. 2012;2012:2817–27.10.1155/2012/867036Search in Google Scholar

[55] Kumar V, Khan I, Gupta U. Lipid-dendrimer nanohybrid system or dendrosomes: evidences of enhanced encapsulation solubilization cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of bortezomib. Appl Nanosci. 2020;10:4049–62.10.1007/s13204-020-01515-7Search in Google Scholar

[56] Zhao J, Zheng D, Tao Y, Li Y, Lei J. Self-assembled pH-responsive polymeric nanoparticles based on lignin-histidine conjugate with small particle size for efficient delivery of anti-tumor drugs. Biochem Eng J. 2020;156(15):107526.10.1016/j.bej.2020.107526Search in Google Scholar

[57] Wong WS, Lee CS, Er HM, Lim WH. Preparation and evaluation of palm oil-based polyesteramide solid dispersion for obtaining improved and targeted dissolution of mefenamic acid. J Pharm Innov. 2017;12:76–89.10.1007/s12247-017-9271-3Search in Google Scholar

[58] Huang BB, Liu DX, Liu DK, Wu G. Application of solid dispersion technique to improve solubility and sustain release of emamectin benzoate. Molecules. 2019;24(23):4315.10.3390/molecules24234315Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Agarwal V, Kumar V, Sharma PK. Dissolution enhancement of eplerenone using solvent melt method. Drug Delivery Lett. 2021;11(1):71–80.10.2174/2210303110999201007164919Search in Google Scholar

[60] Devi S, Kumar A, Kapoor A, Verma V, Yadav S, Bhatia M. Ketoprofen–FA Co-crystal: in vitro and in vivo investigation for the solubility enhancement of drug by design of expert. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2022;23:101.10.1208/s12249-022-02253-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Ha ES, Choi DH, Baek IH, Park H, Kim MS. Enhanced oral bioavailability of resveratrol by using neutralized eudragit E solid dispersion prepared via spray drying. Antioxidants. 2021;10(1):90.10.3390/antiox10010090Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Hwang I, Renuka V, Lee JH, Weon KY, Park JB. Preparation of celecoxib tablet by hot melt extrusion technology and application of process analysis technology to discriminate solubilization effect. Pharm Dev Technol. 2020;25(5):525–34.10.1080/10837450.2020.1723023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Misra SK, Pathak K. Supercritical fluid technology for solubilization of poorly water soluble drugs via micro-and naonosized particle generation. Admet Dmpk. 2020;8(4):355–74.10.5599/admet.811Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Verreck G, Chun I, Peeters J, Rosenblatt J, Brewster ME. Preparation and characterization of nanofibers containing amorphous drug dispersions generated by electrostatic spinning. Pharm Res. 2003;20:810–7.10.1023/A:1023450006281Search in Google Scholar

[65] Leuner C, Dressman J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:47–60.10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00076-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Chang CW, Wang CY, Wu YT, Hsu MC. Enhanced solubility dissolution and absorption of lycopene by a solid dispersion technique: The dripping pill delivery system. Powder Technol. 2016;301:641–8.10.1016/j.powtec.2016.07.013Search in Google Scholar

[67] Lee SH, Lee YS, Song JG, Han HK. Improved in vivo effect of chrysin as an absorption enhancer via the preparation of ternary solid dispersion with BrijL4 and aminoclay. Curr Drug Delivery. 2019;16(7):86–92.10.2174/1567201815666180924151458Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Chen Y, Li S, Ji J, Chen Y, Liu J, Wang Y, et al. The preparation of Garcinia Glycosides solid dispersion and intestinal absorption by rat in situ single pass intestinal perfusion. J Pharm Biopharm Res. 2019;1(1):15–20.10.25082/JPBR.2019.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[69] Dong L, Wang B, Chen L, Luo M. Solubilization and in vitro physical and chemical properties of the amorphous spray-dried Lactose-Luteolin system. J Nanomater. 2022;2022:2137188.10.1155/2022/2137188Search in Google Scholar

[70] Athira GK, Jyothi AN, Vishnu VR. Water soluble octenyl succinylated Cassava starch-curcumin nanoformulation with enhanced bioavailability and anticancer potential. Starch-Strke. 2018;70(7–8):1700178.10.1002/star.201700178Search in Google Scholar

[71] Göke K, Bunjes H. Drug solubility in lipid nanocarriers: Influence of lipid matrix and available interfacial area. Int J Pharm. 2017;529(1–2):617–28.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.07.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Wang T, Ning W, Zhang Y, Shen W, Gao X, Li T. Solvent injection-lyophilization of tert-butyl alcohol/water cosolvent systems for the preparation of drug-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. 2010;79(1):254–61.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.04.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Pedro ID, Almeida OP, Martins HR, de Alcântara Lemos J, de Barros AL, Leite EA, et al. Optimization and in vitro/in vivo performance of paclitaxel-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for breast cancer treatment. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2019;54:101370.10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101370Search in Google Scholar

[74] Valizadeh A, Khaleghi AA, Roozitalab G, Osanloo M. High anticancer efficacy of solid lipid nanoparticles containing Zataria multiflora essential oil against breast cancer and melanoma cell lines. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;22:1–7.10.1186/s40360-021-00523-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[75] Chen R, Wang S, Zhang J, Chen M, Wang Y. Aloe-emodin loaded solid lipid nanoparticles: formulation design and in vitro anti-cancer study. Drug Delivery. 2015;22(5):666–74.10.3109/10717544.2014.882446Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Du Y, Ling L, Muhammad I, Wei H, Xia Q, Zhou W, et al. Redox sensitive lipid-camptothecin conjugate encapsulated solid lipid nanoparticles for oral delivery. Int J Pharm. 2018;549(1–2):352–62.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.08.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[77] Nafee N, Gaber DM, Elzoghby A,O, Helmy MW, Abdallah OY. Promoted antitumor activity of myricetin against lung carcinoma via nanoencapsulated phospholipid complex in respirable microparticles. Pharm Res. 2020;37(82):82–106.10.1007/s11095-020-02794-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[78] Esfandiari N, Ghoreishi SM. Synthesis of 5-Fluorouracil nanoparticles via supercritical gas antisolvent process. J Supercrit Fluids. 2013;84:205–10.10.1016/j.supflu.2013.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[79] Reverchon E, Porta GD, Spada A, Antonacci A. Griseofulvin micronization and dissolution rate improvement by supercritical assisted atomization. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56(1):1379–87.10.1211/0022357044751Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Salehi H, Karimi M, Raofie F. Micronization and coating of bioflavonoids extracted from Citrus sinensis L. peels to preparation of sustained release pellets using supercritical technique. J Iran Chem Soc. 2021;18:3235–48.10.1007/s13738-021-02262-4Search in Google Scholar

[81] El-Gendy N, Berkland C. Combination chemotherapeutic dry powder aerosols via controlled nanoparticle agglomeration. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1752–63.10.1007/s11095-009-9886-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[82] dos Santos AE, Dal Magro C, de Britto LS, Aguiar GP, de Oliveira JV, Lanza M. Micronization of luteolin using supercritical carbon dioxide: characterization of particles and biological activity in vitro. J Supercrit Fluids. 2021;181:105471.10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105471Search in Google Scholar

[83] Wang ZD, Peng HH, Guan YX, Yao SJ. Supercritical CO2 assisted micronization of curcumin-loaded oil-in-water emulsion promising in colon targeted delivery. J CO2 Util. 2022;59:101966.10.1016/j.jcou.2022.101966Search in Google Scholar

[84] Zhang H, Li G, Yang J, Chen AZ, Xie M. Supercritical-derived artemisinin microfibers and microparticles for improving anticancer effects. J Supercrit Fluids. 2021;175:105276.10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105276Search in Google Scholar

[85] Tang HX, Cai YY, Liu CG, Zhang JT, Kankala RK, Wang SB, et al. Sub-micronization of disulfiram and disulfiram-copper complexes by Rapid expansion of supercritical solution toward augmented anticancer effect. J CO2 Util. 2019;39:101187.10.1016/j.jcou.2020.101187Search in Google Scholar

[86] Yu G, Ning Q, Mo Z, Tang S. Intelligent polymeric micelles for multidrug co-delivery and cancer therapy. Artif Cell Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:1476–87.10.1080/21691401.2019.1601104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Elzoghby AO, Helmy MW, Samy WM, Elgindy NA. Spray-dried casein-based micelles as a vehicle for solubilization and controlled delivery of flutamide: Formulation characterization and in vivo pharmacokinetics. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;84:487–96.10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.01.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Patidar P, Pillai SA, Sheth U, Bahadur P, Bahadur A. Glucose triggered enhanced solubilisation release and cytotoxicity of poorly water soluble anti-cancer drugs fromT1307 micelles. J Biotechnol. 2017;254:43–50.10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.06.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Li H, Fang Y, Li X, Tu L, Yang Z. Evaluation of novel paclitaxel-loaded NO-donating polymeric micelle for improved therapy of gastroenteric tumor. N J Chem. 2021;45(31):13763–74.10.1039/D1NJ00979FSearch in Google Scholar

[90] Zuo R, Zhang J, Song X, Hu S, Gao X, Wang J, et al. Encapsulating halofuginone hydrobromide in TPGS polymeric micelles enhances efficacy against triple-negative breast cancer cells. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:1587–600.10.2147/IJN.S289096Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Cui M, Jin M, Han M, Zang Y, Yin X. Improved antitumor outcomes for colon cancer using nanomicelles loaded with the novel antitumor agent LA67. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:3563–76.10.2147/IJN.S241577Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[92] Pacheco M, Mayorga-Martinez CC, Viktorova J, Ruml T, Escarpa A, Pumera M. Microrobotic carrier with enzymatically encoded drug release in the presence of pancreatic cancer cells via programmed self-destruction. Appl Mater Today. 2022;27:101494.10.1016/j.apmt.2022.101494Search in Google Scholar

[93] Khezri B, Mousavi S, Krejcova L, Heger Z, Sofer Z, Pumera M. Ultrafast electrochemical trigger drug delivery mechanism for nanographene micromachines. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29(4):1806696.10.1002/adfm.201806696Search in Google Scholar

[94] Almawash S, El Hamd MA, Osman SK. Polymerized β-cyclodextrin-based injectable hydrogel for sustained release of 5-fluorouracil/methotrexate mixture in breast cancer management: in vitro and in vivo analytical validations. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(4):817.10.3390/pharmaceutics14040817Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[95] Abdellatif AA, Mohammed AM, Saleem I, Alsharidah M, Al Rugaie O, Ahmed F, et al. Smart injectable chitosan hydrogels loaded with 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of breast cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(3):661.10.3390/pharmaceutics14030661Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[96] Abdellatif AA, Alsowinea AF. Approved and marketed nanoparticles for disease targeting and applications in COVID-19. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):1941–77.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0115Search in Google Scholar

[97] Abdellatif AA, Tolba NS, Alsharidah M, Al Rugaie O, Bouazzaoui A, Saleem I, et al. PEG-4000 formed polymeric nanoparticles loaded with cetuximab downregulate p21 & stathmin-1 gene expression in cancer cell lines. Life Sci. 2022;300:120581.10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120581Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[98] Abdellatif AA, Ibrahim MA, Amin MA, Maswadeh H, Alwehaibi MN, Al-Harbi SN, et al. Cetuximab conjugated with octreotide and entrapped calcium alginate-beads for targeting somatostatin receptors. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4736.10.1038/s41598-020-61605-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[99] Abdellatif AA, Aldhafeeri MA, Alharbi WH, Alharbi FH, Almutiri W, Amin MA, et al. Freeze-drying ethylcellulose microparticles loaded with etoposide for in vitro fast dissolution and in vitro cytotoxicity against cancer cell types, MCF-7 and Caco-2. Appl Sci. 2021;11:9066.10.3390/app11199066Search in Google Scholar

[100] Tawar M, Raut K, Chaudhari R, Jain N. Novel methods to enhance solubility of water insoluble drugs. Asian J Res Pharm Sci. 2022;12:151–6.10.52711/2231-5659.2022.00026Search in Google Scholar

[101] Boussios S, Pentheroudakis G, Katsanos K, Pavlidis N. Systemic treatment-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: incidence clinical presentation and management. Ann Gastroenterol. 2012;25:106–18.Search in Google Scholar

[102] Jeong SH, Youn YS, Shin BS, Park ES. Drug polymorphism and its importance on drug development process. J Pharm Invest. 2010;40:9–17.10.4333/KPS.2010.40.S.009Search in Google Scholar

[103] Wang H, Xie X, Zhang F, Zhou Q, Tao Q, Zou Y, et al. Evaluation of cholesterol depletion as a marker of nephrotoxicity in vitro for novel β-cyclodextrin derivatives. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(6):1387–93.10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[104] Wong SN, Chen YCS, Xuan B, Sun CC, Chow SF. Cocrystal engineering of pharmaceutical solids: therapeutic potentials and challenges. CrystEngComm. 2021;23(40):7005–38.10.1039/D1CE00825KSearch in Google Scholar

[105] Li X, Yang X, Wu R, Dong N, Lu X, Zhang P. Research progress of response strategies based on tumor microenvironment in drug delivery systems. J Nanopart Res. 2021;23(64):1–14.10.1007/s11051-020-05136-7Search in Google Scholar

[106] Bhore SD. A review on solid dispersion as a technique for enhancement of bioavailability of poorly water soluble drugs. Res J Pharm Technol. 2014;7:1485–91.Search in Google Scholar

[107] Hirlekar R, Bulbule P, Kadam V. Innovation in drug carriers: supercooled smectic nanoparticles. Curr Drug Ther. 2012;7:56–63.10.2174/157488512800389173Search in Google Scholar

[108] Leleux J, Williams RO. Recent advancements in mechanical reduction methods: particulate systems. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2014;40(3):289–300.10.3109/03639045.2013.828217Search in Google Scholar PubMed