Abstract

Patchy interactions and heterogeneous charge distribution make nanoclay (NC) a promising biomaterial to interact with different biomolecules, polymers, and biological components. Many researchers have studied the polymer/clay nanocomposites in recent years. However, some deficiencies, such as poor impact strength, limit the application of polymer/clay nanocomposites in different fields. As a result, many attempts have been made to resolve this problem. Also, researchers have developed calcium carbonate (CaCO3) nanoparticles as biomedical materials. The nontoxic properties and biocompatibility of both CaCO3 and NC make their nanocomposites ideal for biomedical applications. In this article, a detailed review of the ternary polymer nanocomposites containing NC and CaCO3 is presented. The morphological, thermal, mechanical, and rheological characteristics, in addition to the modeling of behavior and foam properties, are studied in this article. In addition, the potential challenges for ternary nanocomposites and their biomedical applications are discussed.

1 Introduction

The development of industrial and economic activities results in continuous requirements for new, low-cost, low-weight, and high-performance materials, which can meet different conditions. Polymers are good candidates for many fields, but they should be developed for special requirements [1,2,3,4,5,6]. With the advent of nanotechnology, nanocomposites with ultrafine phase dispersion of nanofiller show many unique properties along with various technological and economic opportunities [4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The large surface area and the big aspect ratio of nanoparticles, together with the good interfacial interactions among polymer and nanoparticles, lead to exceptional behavior in polymer nanocomposites [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

To progress the effectiveness of nanocomposites in industrial applications, it is vital to concurrently improve the overall properties such as modulus, strength, toughness, heat distortion temperature, etc., without sacrificing the processability and economical considerations. Nanoclay (NC) is a layered biomaterial with a defined structure at the nanoscale. NC commonly deteriorates the impact strength of polymer nanocomposites [40,41]. It limits the application of polymer/NC nanocomposites in various areas. Some researchers applied rubber to solve the problem, but it decreased the modulus and strength of nanocomposites [42,43,44,45].

In recent years, a strong emphasis has been carried out on the development of ternary nanocomposites due to the high potential of nanotechnology. Two dissimilar particles can handle the performances of the nanocomposites creating very exceptional features in the behavior of materials [46,47,48,49,50]. A great number of researchers have reported the advantages of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) in nanocomposites [51,52,53,54]. Rajan et al. [55] investigated the in vitro cytotoxicity of high-density polyethylene composite reinforced with CaCO3 nanoparticles. Their results showed that CaCO3 nanoparticles provide high mechanical and tribological properties in nanocomposites. In another study, Gayer et al. [56] developed a composite by PLA and CaCO3 for the selective laser sintering process of bone tissue engineering scaffolds and successfully demonstrated the modified additive manufacturing system.

The addition of CaCO3 nanoparticles to NC nanocomposites would not deteriorate the advantages of nanocomposites, such as low-cost, low-weight, high-performance, and ease of processing, because the addition of both NC and CaCO3 to the polymer matrix causes better dispersion of nanoparticles and more mechanical properties, due to the stiffening effects of both nanoparticles and increment of mixture viscosity. Moreover, the price of CaCO3 is much lower than NC. Therefore, by replacing a part of clay with CaCO3 in the composite, the price of the product can be reduced.

The binary nanocomposites containing NC or CaCO3 have been reviewed in the previous article. In this review article, a detailed study of the ternary nanocomposites containing NC and CaCO3 is presented, and also, the potential opportunities are explained for future studies. Ternary samples include the advantages of both NC and CaCO3, improving the mechanical, thermal, barrier, and flame-retardant properties. So, it is important to discuss the specific properties of ternary nanocomposites. Moreover, exceptional cyto-compatibility, biocompatibility, big surface area, and charge characteristics of NC as well as high osteo-conductivity and slow biodegradability of CaCO3 provide the biomedical applications of ternary samples in tissue engineering, wound healing, implant, and medical devices. Here, the morphological, thermal, mechanical, and rheological properties along with the modeling of properties and their foamability properties are investigated.

2 Biomedical applications of polymer/NC/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposites

NC is emerging as a biomaterial with a layered shape, nanosized, and well-defined structure [57,58]. A range of biomolecules, polymers, and biological components can physically interact with atomically thin NC due to its heterogeneous charge distribution and patchy interactions. Compared to other classes of nanomaterials, NC has excellent cyto-compatibility and biocompatibility. The high surface area and charged characteristics of NC allow it to interact with a range of small and large biomolecules and to be used for sustained and prolonged therapeutic delivery [59]. A range of synthetic and natural polymers have been combined with NC to obtain nanocomposites for biomedical applications [59]. For example, it was established that the addition of a small amount of NC to polymeric binder forms shear-thinning hydrogels [60], which are extensively used in the biomedical discipline for cells and therapeutic delivery, tissue regeneration, and adhesives [61]. In contrast, CaCO3 nanoparticles have been developed as a material with interesting biomedical applications [62,63]. They are used in drug delivery (as templates for the encapsulation of bioactive compounds), the construction of biosensors, bone replacement grafts in human periodontal osseous defects, bio-mineralization, and enzyme immobilization. Due to its high osteo-conductivity, ease of production, and slow biodegradability, it has also been utilized in medicine as a bone-filling material [64]. Fadia et al. [65] stated that CaCO3 nanoparticles are chemically inert and widely considered in the field of biosensing and drug delivery. CaCO3 has unusual properties such as biocompatibility, big surface-to-volume ratio, easy synthesis, strong nature, and surface functionalization, making them a perfect candidate for biomedical requests. Actually, due to the nontoxic nature and biocompatibility of both NC and CaCO3, their composites have the potential for biomedical requests such as bone tissue engineering, wound healing, implant, 3D bioprinting, medical devices, and enzyme immobilization.

3 Morphological properties

When NC interacts with polymer matrix, batch separation, intercalation, and exfoliation can occur in nanocomposites [66]. The main peaks in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of polypropylene (PP)/NC/CaCO3 and poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC)/NC/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposites shift to the inferior 2θ values than the peak of pristine NC [67,68,69,70,71]. Furthermore, the intensity of main peaks decreases, which reveals the penetration of polymer chains into the NC galleries, leading to disordered NC layers, i.e. mixed morphology of intercalated/exfoliated in many samples. Also, the images obtained by microscopy demonstrate the uniform dispersion of both NC and CaCO3 particles in the matrix [67,68,69,70,71]. Some samples such as PP4/2/14 (An/x/y sample: A is the type of polymer matrix, n is the melt flow index [MFI] of polymer medium, x and y are the weight percentages of NC and CaCO3, respectively) and PP2.5/4/5 show a completely exfoliated NC in the matrix [67,69].

The ternary nanocomposites show broader peaks in comparison to the binary specimens (Figure 1a), which indicates the higher level of exfoliated NC. TEM images also verify the observations [68]. A good dispersion of NC layers in the melt mixing process is affected by three factors, including the interaction between NC platelets and matrix, mechanical shear stress, and molecular diffusion. The high shear stress aids in removing the kinetic restrictions regarding the breakup of agglomerated NC and moving the NC platelets in the sample. The high shear stress can be obtained from the higher viscosity of melt mixing provided by the larger chains of polymer (smaller MFI). Nevertheless, the penetration of larger chains into the NC galleries is difficult. CaCO3 particles can enhance the viscosity and provide a balance between diffusion and shear stress causing a high exfoliation degree [72,73]. Zare et al. [67,74] have also confirmed that the samples containing higher CaCO3 contents show smaller peak intensities in XRD images, indicating the superior exfoliated platelets in the polymer matrix (Figure 1b).

The noble dispersion of nanoparticles has been reached using the maleic anhydride grafted PP (PPgMA) as a compatibilizer and stearic acid-treated CaCO3, which produce more interfacial interactions [67,68,69,70,71]. The TEM images of PVC/NC/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite are illustrated in Figure 2 [71]. The darker strips and the larger spots show the NC layers and CaCO3 nanoparticles, respectively. The disordered NC platelets and well-dispersed CaCO3 nanoparticles are evidently observed in the PVC matrix.

![Figure 2

TEM pictures of (a) PVC/2/8 and (b) PVC/2/16 samples (reproduced from the study of Sadegh Roshanravan [71] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_002.jpg)

TEM pictures of (a) PVC/2/8 and (b) PVC/2/16 samples (reproduced from the study of Sadegh Roshanravan [71] with permission).

Tang et al. [69] developed PP/montmorillonite (MMT)/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposites in a twin screw extruder by melt processing. As exposed in Figure 3, the diffraction peaks of the nanocomposite have been removed compared with the pristine MMT. The MMT nanofiller is thereby properly dispersed and exfoliated within the PP matrix. In another study, Dai et al. [70] developed a ternary nanocomposite based on high-density polyethylene (HDPE). Figure 4 illustrates a synergistic effect that MMT and CaCO3 fillers could produce. Long chains of HDPE are suggested to intercalate into the MMT interlayer. The CaCO3 nanofillers are simultaneously wrapped in this long chain, and a link between the HDPE chains and two different inorganic fillers is created.

![Figure 3

XRD patterns for MMT and its nanocomposite (reproduced from the study of Tang et al. [69] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_003.jpg)

XRD patterns for MMT and its nanocomposite (reproduced from the study of Tang et al. [69] with permission).

![Figure 4

The synergistic effects of MMT and CaCO3 in HDPE matrix (reproduced from the study of Dai et al. [70] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_004.jpg)

The synergistic effects of MMT and CaCO3 in HDPE matrix (reproduced from the study of Dai et al. [70] with permission).

Asadi et al. [75] have reported that the distance between NC sheets in ternary nanocomposite is higher than neat NC. The communication of hydroxyl groups of NC and carboxyl groups of PLA seems to cause the separation of NC layers and their intercalation in ternary nanocomposites. In addition, CaCO3 facilitates the NC layer opening, which is thought to occur by increasing the polymer viscosity, thereby increasing the shear stress on the nanofillers. By a two-step melt mixing technique, Alavitabari et al. [76] proposed a nanocomposite with an HDPE matrix and two nanofillers, including NC and CaCO3. XRD results demonstrated that as the PEgMA linking agent was increased in the samples, XRD peaks shifted to smaller angles, and their intensity decreased. Incorporating CaCO3 also increased the distance between NC layers by causing the peaks to shift toward low angles.

In another work [77], it was discovered that in dual-filler samples, peak intensity is much smaller than that of binary systems based on the XRD technique. Furthermore, they investigated the effect of adding CaCO3 nanofillers to the NR matrix on the dispersion of silicate nanolayers. Also, FESEM analysis revealed the excellent dispersion of both nanofillers into the polymer matrix [78]. In another study, Kapole et al. [79] prepared a nanocomposite containing a hybrid polymer composed of acrylic polyol–polyurethane and nanofillers of NC and CaCO3 by in situ polymerization. They observed that adding two nanofillers to the polymeric system using in situ technique improved nanofiller dispersion into the polymeric matrix. The addition of both NC (platelet shape) along with CaCO3 increases the viscosity of samples, which improves the dispersion of nanoparticles without aggregation. Conclusively, both intercalation and exfoliation of NC layers are observed in the ternary samples, because polymer chains are placed between the layers increasing their spacing. Increasing the distance between layers is called intercalation. However, when the order of the NC layers is disrupted along with the increase in distance, this is called exfoliation. Exfoliation is the most ideal dispersion mode for nanoparticles in the polymer matrices, because the exfoliated layers have the significant surface area involving the polymer chains to improve the mechanical properties of nanocomposites. The distance between NC layers is increased by the presence of CaCO3 nanoparticles in ternary samples. The increase in distance can be explained by the shift of peak related to NC toward low angles in the XRD diagram, which indicates intercalation. Moreover, NC layers may be disordered in the ternary samples indicating the exfoliation. The presence of CaCO3 may increase the viscosity of samples, helping for exfoliation. Nevertheless, nanoparticles such as NC and CaCO3 have high surface energy, causing aggregation/agglomeration in the nanocomposites [80,81,82]. In other words, nanoparticles are aggregated/agglomerated in the polymer matrix, weakening their performance for stiffening. In a hydrophobic polymer matrix, the hydrophilic character of clay minerals prevents its exfoliation into discrete monolayers. This can be overcome by compatibilization, which consists of a cation exchange within the interlayer space [83]: cations of alkali metals or alkaline earth metals are substituted by voluminous organic ones, most frequently an alkylammonium. Clay mineral organophilization facilitates the penetration of polymer chains into the interlayer space, as well as the formation of an intercalated or exfoliated (delaminated) nanocomposite structure. Additionally, polymer matrix and nanoparticles should be compatible to achieve well-dispersed nanoparticles and exfoliated layers in spite of aggregation/agglomeration. In order to increase the compatibility between components, it is necessary to functionalize the surface of nanoparticles or use a compatibilizer such as PPgMA. However, filler functionalization and using compatibilizer increase the cost of nanocomposite manufacturing. Actually, both NC and CaCO3 have more tendency of high aggregation/agglomeration in polyolefin polymers such as PP and LDPE, because the nanofillers are polar and polyolefin are non-polar; therefore, there is no good interaction between them, that is the reason of using compatibilizer in the system.

4 Thermal properties

4.1 Melting and crystallization

The nucleation effect of nanoparticles affects the melting and crystallization performance. Since crystallization has a key impact on the features of composites, crystallization analysis is much more important to study. Table 1 shows the peak temperature of crystallization (T c), the degree of crystallinity (X c), and the peak temperature of melting (T m) for different ternary nanocomposites. Obviously, the crystallization process shifts toward the higher temperature, and also, X c increases due to the irregular nucleation impact of nanofillers. The effect of MFI of the polymer matrix (chain size of polymer) on the X c is studied in PP4/4/8 and PP16/4/8 examples. It is known that two major factors, including the nucleation of nanoparticles and the development of spherulites, affect the crystallization. The smaller chains (higher MFI) encourage the earlier and more nucleation together with extra and easier activities. Consequently, further chains can be arranged into the crystal cells, and thus, further crystallinity is developed. X c values of PP4/4/8 and PP16/4/8 examples validate this statement. From Table 1, although NC layers deliver numerous nucleation places, the increasing NC content reduces T c and X c. It can be due to the good spreading of NC layers in the matrix, which mechanically involves the polymer chains and restricts the molecular movements. In addition, higher CaCO3 content increases the dispersion of NC, which limits the chain mobilities. For this reason, increasing CaCO3 content slightly decreases the X c.

Crystallization and melting characteristics of ternary nanocomposites (reproduced from [68,70,84,85] with permission)

| No. | Samples | T c (°C) | X c | T m (°C) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PP14.5 | 116 | 53 | 165 | [68] |

| 2 | PP14.5/2/2 | 121 | 54 | 164 | [68] |

| 3 | PP14.5/4/2 | 120 | 48 | 163 | [68] |

| 4 | PP14.5/2/4 | 120 | 50 | 164 | [68] |

| 5 | HDPE0.27 | 121.2 | 39.7 | 135.7 | [70] |

| 6 | HDPE0.27/3/12.3 | 115.3 | 50.3 | 130 | [70] |

| 7 | PP4 | 116.8 | 43.6 | 163 | [84] |

| 8 | PP4/4/8 | 127.2 | 45.7 | 164.2 | [84] |

| 9 | PP16/4/8 | 129.4 | 49.1 | 165.5 | [84] |

| 10 | PP4/2/14 | 129.3 | 47.1 | 164.4 | [84] |

| 11 | PP4/6/14 | 128.1 | 45.1 | 163.8 | [84] |

| 12 | PP4/4/20 | 130.4 | 45 | 164.2 | [84] |

| 13 | PP3.2 | — | 46.6 | — | [85] |

| 14 | PP3.2/3/15 | — | 51.5 | — | [85] |

| 15 | PP3.2/5/15 | — | 52.5 | — | [85] |

| 16 | PP3.2/7/15 | — | 51.7 | — | [85] |

The crystallization rate was also evaluated by temperature and time [84]. It was found that the slowest and the fastest crystallization processes occurred in PP4 and PP4/6/14 ternary nanocomposites, respectively [84].

The obtained n as Avrami exponent for many ternary samples are near to 2, indicating two-dimensional developments of crystals. n value for the PP4/2/14 sample is between 2 and 3 (2.12), illustrating the immediate nucleation with diffusion handling in the crystal growth [86]. The K values are consistent with the calculated results by the curves of the crystallization rate.

As observed in Table 1, the variation of T m is more negligible compared to T c. The melting curves of ternary samples show a main peak at 165°C mentioning the α-crystal and a much smaller peak at 151°C due to the β-crystal (Figure 5) [87].

![Figure 5

Melting of ternary samples (reproduced from the study of Zare and Garmabi [84] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_005.jpg)

Melting of ternary samples (reproduced from the study of Zare and Garmabi [84] with permission).

The peak intensity exposes that the volume of the β-phase is too lower than the α-crystal, while NC and CaCO3 can significantly encourage the nucleation of the β-phase [88,89,90]. As a result, β-nucleation of NC and CaCO3 is disregarded as they are simultaneously used in a polymer matrix, as reported in several works [68,74,84]. Chen et al. [68] have reported that a PP/CaCO3 sample with 4 wt% of CaCO3 contains 40% of the β-phase, but the ternary nanocomposites only display the α-phase. Possibly, the dissimilarity between two nanofillers induces such behavior. The NC layers are platy with higher aspect ratio and many nucleation sites per unit surface area, while CaCO3 is spherical with much fewer nucleation sites and aspect ratio [89].

A DSC curve for neat HDPE and nanocomposite is shown in Figure 6. Dai et al. [70] also showed that in the ternary nanocomposite, several small crystals are formed by two nanofillers acting as nucleating agents. This leads to a greater degree of crystallinity and a faster crystallization time than pure HDPE.

![Figure 6

Differential scanning calorimetry plots for pure HDPE and ternary nanocomposite (reproduced from the study of Dai et al. [70] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_006.jpg)

Differential scanning calorimetry plots for pure HDPE and ternary nanocomposite (reproduced from the study of Dai et al. [70] with permission).

4.2 Flammability and thermal stability

The flammability properties of the PP ternary sample were characterized in terms of the heat release rate (HRR). The peak HRR of PP/4/5 was reduced by about 53.5% in comparison with that of pure PP [69]. The main mechanism of reduction in HRR depends on the condensed phase process, and therefore, NC layers play a more significant role in the flame retardancy of ternary samples [69]. Also, it was found that the efficiency of NC for HRR drop is better than that of CaCO3 owing to the layer structure of NC, which sandwiches the polymer chains. Furthermore, the high level of dispersion along with the small diameters of CaCO3 nanoparticles improves the flame retardancy greater than the micron-sized particles [69].

The inorganic nanofillers with high specific surface area protect the polymer medium and thus, the thermal stability of nanocomposites improves compared to neat matrices [69,70,71,85]. The ternary nanocomposite of PP/4/5 showed a top weight loss temperature of 462.5°C and 5% loss temperature of 414.6°C, while a top weight loss temperature of 336.4°C and 5% loss temperature of 440.8°C were reported for neat PP [69]. It was found that the addition of NC from 2 to 6 wt% did not have a positive effect on the degradation temperature of PVC/NC/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite [71]. It may be due to the poor nanoparticle dispersion, which results in the inferior barrier properties. In addition, the enhancement of CaCO3 loading increases the thermal stability. Two reasons can be suggested for this phenomenon: first, the absorption of hydrochloric acid by CaCO3 nanoparticles, and second, the high dispersion of NC in the attendance of high content of CaCO3, as mentioned before in Section 3. Alavitabari et al. [76] also verified that the nanocomposites were not ruined during mixing, and both NC and CaCO3 might enhance the thermal stability of the PEgMA compatibilizer (Figure 7).

![Figure 7

Results of OIT tests for various materials (reproduced from the study of Alavitabari et al. [76] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_007.jpg)

Results of OIT tests for various materials (reproduced from the study of Alavitabari et al. [76] with permission).

5 Mechanical properties

NC particles have a strong impact on the modulus and stiffness of polymers, while the CaCO3 particles seem to significantly improve the toughness [91,92,93,94]. In this regard, the simultaneous addition of both nanofillers has a synergistic effect on the stiffness. It is proposed that the long chains of polymer intercalate into the NC interlayer. CaCO3 nanoparticles are enwound by this long chain simultaneously. Two different inorganic fillers are linked by polymer molecules, which provide an opportunity for two fillers to have a synergistic effect on the properties of ternary composites [70].

The mechanical features of different binary and ternary nanocomposites are illustrated in Table 2. The modulus of ternary nanocomposites containing NC and CaCO3 is better than that of binary nanocomposites in total cases due to the strengthening impact of nanofillers. The highest improvement of modulus is found in the HDPE 0.27/3/12.3 sample by 300% [70]. The tensile strength shows minor variation in many binary and ternary samples. The impact strength of clay-filled samples is commonly reduced, but ternary systems have higher impact strength than binary nanocomposites except for PP/NC/CaCO3 samples in Chen et al.’s work [68]. The maximum enhancement of impact strength is obtained for the PP2.5/4/5 ternary sample by 75% [69]. The influences of various parameters on the stiffness of ternary nanocomposites are extensively discussed in the following.

Mechanical performances of nanocomposites (reproduced from previous studies [68–70] with permission)

| No. | Samples | Tensile modulus (GPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Impact strength | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PP14.5 | 1.75 | 31.8 | 1.8 (kJ/m2) | [68] |

| 2 | PP14.5/2/0 | 2.12 | 35.7 | 1.73 | [68] |

| 3 | PP14.5/4/0 | 2.91 | 35.85 | 1.68 | [68] |

| 4 | PP14.5/0/2 | 1.85 | 32.2 | 2.17 | [68] |

| 5 | PP14.5/0/4 | 1.97 | 31 | 2.78 | [68] |

| 6 | PP14.5/2/2 | 2.43 | 36.9 | 1.77 | [68] |

| 7 | PP14.5/2/4 | 2.53 | 36 | 1.74 | [68] |

| 8 | PP14.5/4/2 | 2.82 | 36.7 | 1.71 | [68] |

| 9 | PP2.5 | — | 34.6 | 3.4 (kJ/m2) | [69] |

| 10 | PP2.5/4/0 | — | 34.8 | 3.8 | [69] |

| 11 | PP2.5/0/5 | — | 35.4 | 4.7 | [69] |

| 12 | PP2.5/4/5 | — | 35.2 | 5.9 | [69] |

| 13 | HDPE0.27 | 0.16 | 15.1 | 437.1 (J/m) | [70] |

| 14 | HDPE0.27/3/0 | 0.321 | 31.1 | 309.4 | [70] |

| 15 | HDPE0.27/0/12.3a | 0.091 | 10.3 | 321 | [70] |

| 16 | HDPE0.27/0/12.3b | 0.308 | 17.4 | 564.2 | [70] |

| 17 | HDPE0.27/3/12.3b | 0.645 | 33.9 | 556.2 | [70] |

aUntreated CaCO3. bTreated CaCO3.

5.1 MFI of polymer matrix

The large improvement of tensile modulus in the PP/NC/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite was found in the smaller MFI of PP due to the superior dispersion of nanoparticles [67]. The highest impact strength is found by the medium MFI (10 g/10 min).

5.2 NC content

The positive result of NC amount on the modulus of different ternary nanocomposites was reported [67,68,69,70,71]. Furthermore, the minor enhancement of tensile strength and the dropping of impact strength were shown owing to the restriction of macromolecules. The similar effects of NC amount on the modulus and impact strength of PVC/NC/CaCO3 samples were also expressed [71].

5.3 NC type

Sorrentino et al. [85] have evaluated the NC types in the ternary samples containing 15 wt% of PPgMA and 15 wt% of micro-CaCO3. The higher content of Dellite 72T NC showed an increase in the ultimate strain together with a minor variation in the tensile strength. But, Nanofil 5 exhibited a reduction of ultimate strain and a growth in the tensile strength. Also, over the 5 wt% of NC, Nanofil 5 improved the modulus, while the Dellite 72T had an inverse role. Only for nanocomposites prepared with Nanofil, a further increase of Young’s modulus was obtained by raising the NC concentration to 7 wt%. The main reason can be explained by the higher ability of Nanofil clay to be intercalated compared to Dellite 72T. Actually, there are strong interfacial interactions between PP and Nanofil 5, resulting in the intercalation and exfoliation of NC, while the poor interfacial interaction between PP and Dellite 72T cannot cause the intercalated/exfoliated layers weakening the properties.

5.4 CaCO3 content

CaCO3 content improved the tensile modulus of ternary specimens based on the PP [67,68] and PVC [71]. Although CaCO3 nanoparticles promote various toughening mechanisms in the binary nanocomposites [95,96], the decline of impact strength with the growing CaCO3 content is unexpectedly found in the ternary systems. When the CaCO3 amount increases, the acquired dispersion of NC induces the reduction of molecular chain mobilities and, thus, the impact strength. The same behavior was wonderfully illustrated in the PVC/NC/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite [71].

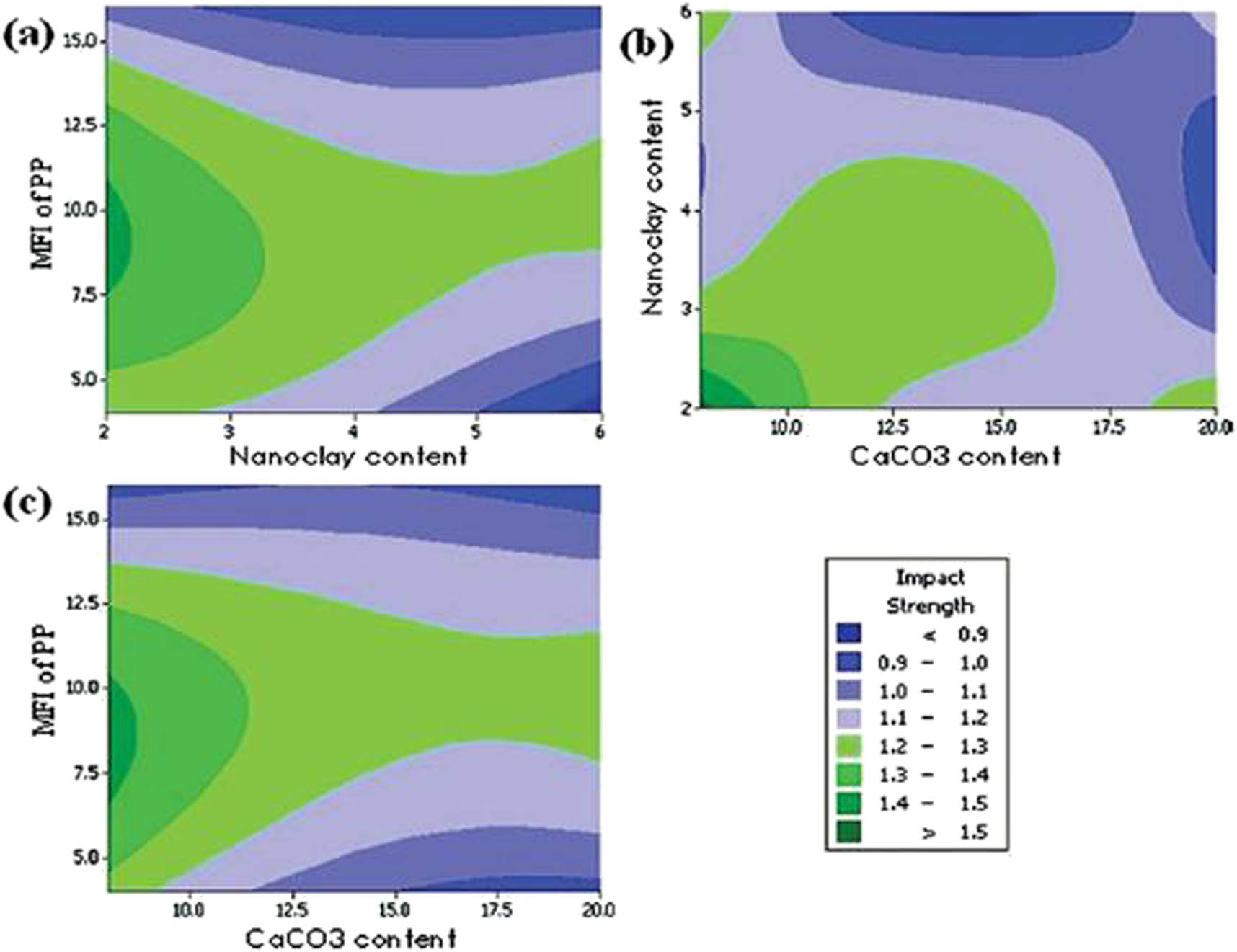

Figure 8 shows 2D schemes of impact strength for PP/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposite [67]. It displays that to attain the greatest impact results, MFI of 8–10 g/10 min, the NC content of 2 wt%, and the CaCO3 loading of 8 wt% are required. The tensile strength shows a minor enhancement below the CaCO3 concentration of 15 wt%. By increasing the level of CaCO3 to 20 wt%, a slight reduction of tensile strength is observed. It is suggested that the high content of nanofillers limits the chain movement and also decreases the adhesion at the interface, reducing the tensile strength. In addition to the stiffening effect of CaCO3 nanoparticles, they increase the melt viscosity of the mixture, causing more shear stress to the NC layers. The higher shear stress promotes more individual NC layers, improving the dispersion of NC [67]. In addition, the contour plots for impact strength of PVC/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposite demonstrated that the top results are attained at smaller contents of NC and CaCO3 [71].

The impact strength for PP/NC/CaCO3 samples at different levels of (a) nanoclay content and MFI of PP, (b) CaCO3 content and nanoclay content and (c) CaCO3 content and MFI of PP.

5.5 Feeding rate

The feeding rate is a more effective parameter in the extrusion process [97]. More feeding rate decreases the residence time in the extruder causing imperfection breakup and dispersion of nanoparticles. On the other hand, the lower feeding rate induces further empty space in the mixing zones along with the application of low shear stress on the melt mixing, which lastly results in weak-quality mixing. Also, the degradation of materials may occur to more residence time in the extruder. Therefore, obtaining an optimized level of feeding rate is a main subject in the extrusion process. PP10/4/14 samples were prepared at different feeding rates [74]. The mechanical properties of the samples are presented in Table 3. The tensile properties slightly change at different feeding rates, but the impact strength becomes much superior at the higher feeding rate of 3 kg/h.

Mechanical performance of nanocomposite prepared in different feeding rates of twin screw extruder [74]

| No. | Feeding rate (kg/h) | Tensile modulus (GPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Impact strength (kJ/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2.52 | 38 | 2.83 |

| 2 | 2 | 2.54 | 38.2 | 2.54 |

| 3 | 3 | 2.48 | 38.1 | 3.2 |

Tang et al. [69] found that the combination of nanoscale CaCO3 with PP/MMT samples improved the mechanical features of the samples such as tensile properties and notch impact tests. In other words, a close contact between PP chain and the nanofiller forms a stronger interphase and, consequently, better mechanical properties for the ternary nanocomposite. Generally, an interphase is created between polymer chains and nanoparticles due to the big surface area of nanoparticles and strong interfacial interaction between polymer and filler [4,98,99,100,101,102,103]. Since the interphase is stronger than the polymer matrix, it plays a stiffening role in the nanocomposite. Actually, a thicker and tougher interphase causes a stronger nanocomposite and the mechanical properties of nanocomposites directly link to the interphase characteristics. The mechanical properties of ternary samples mainly depend on the interphase characteristics, and literature reports have studied this topic well. Jahan et al. [104] reported a ternary nanocomposite consisting of PVDF polymer matrix, CaCO3, and MMT applicable as a piezoelectric material. Figure 9 shows the stress–strain diagrams of the prepared samples. They found that hybrid fillers (CaCO3 and MMT) had negative effects on tensile strength due to weaker affinity between untreated CaCO3 and PVDF because of the lower surface energy of PVDF. In addition, PVDF nanocomposites had a lower Young’s modulus than neat PVDF. PVDF nanocomposite was thus made more flexible and deformable under load, thus improving its piezoelectric properties.

![Figure 9

Tensile curves of neat PVDF and its composites (reproduced from the study of Jahan et al. [104] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_009.jpg)

Tensile curves of neat PVDF and its composites (reproduced from the study of Jahan et al. [104] with permission).

Compared to pure PLA, ternary nanocomposites had higher modulus and better tensile strength [75]. By using two kinds of nanofillers in the PLA matrix, the ternary nanocomposite can achieve remarkable improvements in mechanical properties.

In a study by Alavitabari et al. [76], they found that by increasing the NC loading, the tensile modulus of nanocomposites increases. In addition, shear stresses during melt compounding may be increased due to the presence of CaCO3. Consequently, NC platelets can be intercalated and exfoliated into the HDPE matrix.

In addition, in another study [77], it was concluded that NR-based hybrid nanocomposites containing MMT and CaCO3 had a 445% growth in tensile strength, a 144% enhancement in stress at 100% strain, and only a 3% growth in elongation at break compared to neat NR. The excellent mechanical properties could be due to the appropriate distribution of MMT and CaCO3 in the medium. Accordingly, they concluded that it was necessary to use a second filler, and especially to use MMT to improve filler dispersion.

In a recent study, Ayaz [105] investigated the impact and flexural power of a nanocomposite composed of PP, NC, and CaCO3 with PPgMA. The incorporation of NC into the nanocomposite reduced the impact strength but enriched the flexural strength. As confirmed by SEM images, they found that incorporating PPgMA into the nanocomposite significantly enhanced the dispersion of NC and CaCO3 and thus enhanced the impact and flexural powers. Ghari et al. [78] also analyzed the nanocomposites containing NR, NC (Cloisite 15A), and CaCO3. Figure 10 shows that hybrid nanocomposites have a higher modulus at all elongations than single-phase nanocomposites. Moreover, strain-induced crystallization occurs in hybrid nanocomposites. Actually, Young’s modulus and tensile strength increase when two fillers are added to NR.

![Figure 10

Stress–strain curves of NR/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposites (reproduced from the study of Ghari et al. [78] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_010.jpg)

Stress–strain curves of NR/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposites (reproduced from the study of Ghari et al. [78] with permission).

Kapole et al. [79] observed that CaCO3 plays a key character in the improved characteristics of the acrylic polyol–polyurethane/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposite such as abrasion resistance and hardness. Furthermore, NC incorporation enhances abrasion resistance, moisture resistance, and scratch hardness. Ahmed et al. [106] prepared a nanocomposite composed of HDPE and a combination of two nanofillers (CaCO3 and bentonite). It was found that all of the stress-softened samples contained excessive amounts of NC and CaCO3. When rigid nanofillers are present in sufficient quantities, they entirely contribute to the toughness jump. In another study, Awan et al. [107] developed a ternary nanocomposite based on HDPE, CaCO3, and NC by melt blending. The hardness value of ternary nanocomposites increased compared to neat HDPE. By incorporating spherical CaCO3 nanofillers into the nanocomposite, mechanical properties were increased, while NC nanofillers affected the chain structure and mobility.

6 Modeling of mechanical properties

Response surface methodology can present a suitable relation between variables and outputs [44,108,109]. The links between the responses comprising tensile modulus and impact strength and the polymer MFI, NC, and CaCO3 amounts were obtained for PP/NC/CaCO3 system [67]. The tensile modulus was also examined using simple models [110]. It has been shown that some models such as Hirsch, Inverse rule of mixtures, Kerner-Nielsen, and Halpin-Tsai can successfully predict the tensile modulus. Halpin-Tsai predictions are matched to the experimented data at smaller aspect ratios. Probably, CaCO3 raises the shear stress during mixing and thus, reduce the aspect ratio of NC layers.

It was also found that some parameters such as the Poisson ratio of polymer and maximum packing filler fraction have not a strong effect on the Kerner–Nielsen predictions [110]. Therefore, the modified equation of the Kerner–Nielsen model was modified and the calculated modulus by this model is well matched to the experimented results (Figure 11) [110]. Besides, the predictions of tensile modulus by the Takayanagi model are much more than the experimental data [110]. As a result, the Takayanagi model was modified for the ternary system. The agreement among theoretical and tentative data is very outstanding using the modified Takayanagi model.

![Figure 11

Experimental data and predicted tensile modulus by modified Kerner-Nielsen model at NC contents of (a) 2 wt%, (b) 4 wt%, and (c) 6 wt% (reproduced from the study of Zare and Garmabi [110] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_011.jpg)

Experimental data and predicted tensile modulus by modified Kerner-Nielsen model at NC contents of (a) 2 wt%, (b) 4 wt%, and (c) 6 wt% (reproduced from the study of Zare and Garmabi [110] with permission).

Based on Ji model, Zare and Garmabi [111] planned a model to predict the modulus and interphase features of ternary systems comprising two nanoparticles (NC and CaCO3). They compared the results by the proposed model with the experimented data. The experimental tensile moduli match well to the developed model, whereas the original Ji model shows considerable disagreement. Thus, the planned model suitably reflects the impressions of interphase and filler dispersion on the modulus.

Zare et al. [112] recommended a model for determining the interphase properties of ternary nanocomposites. They revealed that the interphase depth differently links to filler dimensions and concentrations of filler and interphase. Also, it was stated that the interphase strength straightly links to filler–polymer interface bonding. Furthermore, this group developed the Hashin–Shtrikman model for approximating Young’s modulus of ternary nanocomposites made of PP, NC, and CaCO3 [113]. By ignoring interphase, the Hashin–Shtrikman model underestimates the bulk, shear, and Young’s moduli of samples. However, the proposed model is capable of predicting Young’s moduli of ternary nanocomposite by considering the deepness and power of interphases.

Zare and Garmabi [114] studied the interface adhesion between MMT and CaCO3 and PP matrix using a mechanical property model. Based on the faultless adhesion among nanofillers and PP, the Sato–Furukawa model was advanced for the tensile moduli of ternary nanocomposites. There is a fine arrangement among experimented grades and the proposed model that suggests the filler–filler and polymer–nanofiller contacts in the samples (Figure 12). Additionally, it was reported that the highest interface bonding is formed in the composites encompassing 4 wt% of NC, and various CaCO3 amounts up to 20 wt%.

![Figure 12

The calculations of relative modulus by modified Sato–Furukawa model in NC concentrations of (a) 2 wt%, (b) 4 wt%, and (c) 6 wt% (reproduced from the study of Zare and Garmabi [114] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_012.jpg)

The calculations of relative modulus by modified Sato–Furukawa model in NC concentrations of (a) 2 wt%, (b) 4 wt%, and (c) 6 wt% (reproduced from the study of Zare and Garmabi [114] with permission).

7 Rheological characterizations

The rheological behavior of PP/NC/CaCO3 system was described in the study of Sorrentino et al. [85]. The agreement between measured data and fitted complex viscosity was outstanding. The viscosity of samples increases much more with the addition of NC layers associated with the platelet content or aggregates hindering the polymer chain rotations and movements (Figure 13). Also, the complex viscosity of the ternary system is higher than that of the micro-composite [115]. A distinct shear thinning behavior of ternary nanocomposite is demonstrated in the low frequency. The neat polymers have a same viscosity at a big range of shear rates. However, the samples with filler amount higher than a specified range display shear thinning at whole shear rates (Figure 13) [116,117].

![Figure 13

The complex viscosity of binary and ternary nanocomposites at different shear rates (reproduced from the study of Sorrentino et al. [85] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_013.jpg)

The complex viscosity of binary and ternary nanocomposites at different shear rates (reproduced from the study of Sorrentino et al. [85] with permission).

The unlimited enhancement of viscosity is caused by the network as the shear rate reaches zero leading to yield stress. The trend is due to the dispersed filler, which can be connected to make a network [115]. The complex viscosity of PLA was greatly improved when NC and CaCO3 were added simultaneously [75]. In comparison with neat PLA, ternary nanocomposites have a higher complex viscosity. Based on observations of Asadi et al. [75], it can be concluded that concurrently using NC and CaCO3 results in a significant increase in PLA viscosity.

Alavitabari et al. [76] discovered that at smaller frequencies, the viscoelasticity is further sensitive to the quantity of nanofillers in HDPE/NC/CaCO3 samples. By increasing the NC percentage, storage modulus became less dependent on frequency, and thus viscoelasticity altered from liquid-like to solid-like. However, as CaCO3 content increased, complex viscosity and storage modulus also increased. CaCO3 has a higher percolation threshold than NC due to its lower aspect ratio and smaller surface area than NC, and therefore, has a slighter influence on the viscoelastic behavior. Nanofillers form three-dimensional structures, which reduce the polymer chain mobility and increase energy storage. Evaluation of linear viscoelastic features indicates that the presence of secondary nanofillers contributes to the fine dispersion of layered nanofillers.

8 Foam properties

Lian et al. [118] prepared a nanocomposite foam based on polystyrene (PS) with various concentrations of NC and CaCO3 by CO2 as a blowing agent. They systematically examined the effects of dual nanofillers, foaming pressure, and temperature on the foams and their cellular structure. G′, G″, and η* improved by incorporating nanofillers in the entire scanning frequencies range. NC has a higher enhancement of PS rheological properties than CaCO3 at the same concentration of the nanofillers. All PS/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposites exhibit pseudo-plastic fluid characteristics. In addition, the higher modulus of ternary nanocomposites resulted from the improved melt strength, which increases the stability of cellular structure during the foaming process. Hence, CaCO3 and NC reveal a substantial synergistic influence on the improvement of foaming properties attributed to the diverse roles of nanofillers during cell nucleation and development.

Mohammad Mehdipour et al. [119] prepared a ternary nanocomposite foam based on branched PP, CaCO3, and NC by a solid-state foaming process. A schematic of foam preparation is shown in Figure 14. Several variables affecting the morphology of foams were studied, including temperature and saturation pressure. By the use of NC during foaming, the density of the cells was increased, the cell size was reduced, and melt strength, and cell stability were improved.

![Figure 14

A schematic for manufacturing of PP/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposite foam (reproduced from the study of Mohammad Mehdipour et al. [119] with permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0186/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0186_fig_014.jpg)

A schematic for manufacturing of PP/NC/CaCO3 nanocomposite foam (reproduced from the study of Mohammad Mehdipour et al. [119] with permission).

By adding CaCO3, foamability and cell density were improved. By simultaneously combining NC and CaCO3, foams had a higher cell density and a smaller cell size. Moreover, DSC analysis demonstrated that foamed nanocomposites had a higher crystallinity than unfoamed samples, and DMTA analysis indicated that foamed nanocomposites had a higher tan δ than unfoamed samples. Although the biomedical applications of ternary nanocomposite foams were not studied in the literature, it was stated that low cytotoxic potential, good biocompatibility, cellular structure, and mechanical properties of nanocomposite foams are suitable for scaffolds in bone tissue engineering and wound dressing materials [120,121,122].

9 Conclusions and prospective challenges

This review article studied the ternary systems including polymer, NC, and CaCO3. A comprehensive study was conducted on the impacts of CaCO3 and NC on the structure, mechanical features, thermal behavior, foamability, and rheological characteristics of this system. According to the reports, nanofillers with a complete dispersion in a polymer matrix improved the physical and rheological properties of nanocomposites. However, a challenge is the distribution of nanofillers in the polymer mediums. Poor dispersion weakens the interfacial interphase reducing the final properties of nanocomposite. Therefore, the dispersion quality of nanofillers is one of the key parameters in the ternary samples. Much attempt is necessary to develop the nanocomposites as industrial products. However, the development of processing technologies in terms of quantity, quality, and cost for business is one of the main challenges for ternary nanocomposites. The potential applications of ternary nanocomposites include automobile, aerospace, household, construction, transportation, consumer products, and packaging in the food industry. The ternary nanocomposites can offer an extraordinary combination of stiffness, toughness, ease of processing, and cheapness that is difficult to obtain with other materials. As mentioned, NC can interact with a wide range of polymers and biological components. Also, CaCO3 can be used in drug delivery, enzyme immobilization, encapsulation of bioactive compounds, biosensors, and tissue engineering. Generally, the nontoxic nature and biocompatibility of both NC and CaCO3 provide the biomedical applications of polymer/NC/CaCO3 samples in bone tissue engineering, wound healing, implants, 3D bioprinting, drug delivery, medical devices, and enzyme immobilization. The interest in these nanocomposites has grown recently since their configuration and structure can be changed to provide the desirable aims. It is expected that the ternary nanocomposites can be more developed for various biomedical requests.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2022R1A2C1004437). It was also supported by the Korea government (MSIT) (2022M3J7A1062940).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Liu Q, Fu J, Wang J, Ma J, Chen H, Li Q, et al. Axial and lateral crushing responses of aluminum honeycombs filled with EPP foam. Compos Part B: Eng. 2017;130:236–47.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.07.041Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kazemi F, Naghib SM, Zare Y, Rhee KY. Biosensing applications of polyaniline (PANI)-based nanocomposites: A review. Polym Rev. 2021;61(3):553–97.10.1080/15583724.2020.1858871Search in Google Scholar

[3] Rahimzadeh Z, Naghib SM, Zare Y, Rhee KY. An overview on the synthesis and recent applications of conducting poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)(PEDOT) in industry and biomedicine. J Mater Sci. 2020;55:7575–611.10.1007/s10853-020-04561-2Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zare Y, Rhee KY. Significances of interphase conductivity and tunneling resistance on the conductivity of carbon nanotubes nanocomposites. Polym Compos. 2020;41(2):748–56.10.1002/pc.25405Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zare Y, Gharib N, Rhee KY. Influences of graphene morphology and contact distance between nanosheets on the effective conductivity of polymer nanocomposites. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;25:3588–97.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.06.124Search in Google Scholar

[6] Behera AK. Mechanical and biodegradation analysis of thermoplastic starch reinforced nano-biocomposites. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing; 2018. p. 012001.10.1088/1757-899X/410/1/012001Search in Google Scholar

[7] Boraei SBA, Nourmohammadi J, Mahdavi FS, Zare Y, Rhee KY, Montero AF, et al. Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly (lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):1901–10.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0113Search in Google Scholar

[8] Madani M, Hosny S, Alshangiti DM, Nady N, Alkhursani SA, Alkhaldi H. Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11:731–59.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0034Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ghahramani P, Behdinan K, Moradi-Dastjerdi R, Naguib HE. Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):55–64.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0006Search in Google Scholar

[10] Sharma S, Patyal V, Sudhakara P, Singh J, Petru M, Ilyas R. Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):65–85.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0005Search in Google Scholar

[11] Nazrin A, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM, Tawakkal ISMA, Ilyas RA. Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly (lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):86–95.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0007Search in Google Scholar

[12] Farzaneh A, Rostami A, Nazockdast H. Thermoplastic polyurethane/multiwalled carbon nanotubes nanocomposites: effect of nanoparticle content, shear, and thermal processing. Polym Compos. 2021;42(9):4804–13.10.1002/pc.26190Search in Google Scholar

[13] Farzaneh A, Rostami A, Nazockdast H. Mono-filler and bi-filler composites based on thermoplastic polyurethane, carbon fibers and carbon nanotubes with improved physicomechanical and engineering properties. Polym Int. 2022;71(2):232–42.10.1002/pi.6314Search in Google Scholar

[14] Tajdari A, Babaei A, Goudarzi A, Partovi R, Rostami A. Hybridization as an efficient strategy for enhancing the performance of polymer nanocomposites. Polym Compos. 2021;42(12):6801–15.10.1002/pc.26341Search in Google Scholar

[15] Murtaja Y, Lapčík L, Sepetcioglu H, Vlček J, Lapčíková B, Ovsík M, et al. Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):312–20.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0023Search in Google Scholar

[16] Kamarian S, Yu R, Song J-I. Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;11(1):252–65.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0014Search in Google Scholar

[17] Lu H, Yao Y, Huang WM, Hui D. Noncovalently functionalized carbon fiber by grafted self-assembled graphene oxide and the synergistic effect on polymeric shape memory nanocomposites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2014;67:290–5.10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.07.022Search in Google Scholar

[18] Naghib SM, Behzad F, Rahmanian M, Zare Y, Rhee KY. A highly sensitive biosensor based on methacrylated graphene oxide-grafted polyaniline for ascorbic acid determination. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):760–7.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0061Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zare Y, Rhim S, Garmabi H, Rhee KY. A simple model for constant storage modulus of poly (lactic acid)/poly (ethylene oxide)/carbon nanotubes nanocomposites at low frequencies assuming the properties of interphase regions and networks. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;80:164–70.10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.01.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Vatani M, Zare Y, Gharib N, Rhee KY, Park S-J. Simulating of effective conductivity for grapheme–polymer nanocomposites. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):5907.10.1038/s41598-023-32991-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Zare Y, Kim T-H, Gharib N, Chang Y-W. Effect of contact number among graphene nanosheets on the conductivities of tunnels and polymer composites. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9506.10.1038/s41598-023-36669-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Zare Y, Rhee KY. Development of a model for modulus of polymer halloysite nanotube nanocomposites by the interphase zones around dispersed and networked nanotubes. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–12.10.1038/s41598-022-06465-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Mohammadpour-Haratbar S, Zare Y, Rhee KY, Park S-J. A review on non-enzymatic electrochemical biosensors of glucose using carbon nanofiber nanocomposites. Biosensors. 2022;12(11):1004.10.3390/bios12111004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Mosallanejad B, Zare Y, Rhee KY, Park S-J. Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2022;61(1):744–55.10.1515/rams-2022-0251Search in Google Scholar

[25] Behera AK, Srivastava R, Das AB. Mechanical and degradation properties of thermoplastic starch reinforced nanocomposites. Starch-Stärke. 2022;74(3–4):2100270.10.1002/star.202100270Search in Google Scholar

[26] Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Bouchani Z, Zare Y, Gharib N, Rhee KY. A model for predicting tensile modulus of polymer nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals. Cellulose. 2023;30(15):9261–70.10.1007/s10570-023-05456-6Search in Google Scholar

[27] Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Zare Y, Rhee KY. A review on drug delivery systems containing polymer nanocomposites for breast cancer treatment. Polym Rev. 2023;1–38.10.1080/15583724.2023.2262542Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zare Y. Modeling the strength and thickness of the interphase in polymer nanocomposite reinforced with spherical nanoparticles by a coupling methodology. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;465:342–6.10.1016/j.jcis.2015.09.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Ramesh S, Khandelwal S, Rhee KY, Hui D. Synergistic effect of reduced graphene oxide, CNT and metal oxides on cellulose matrix for supercapacitor applications. Compos Part B: Eng. 2018;138:45–54.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.11.024Search in Google Scholar

[30] Lee JH, Marroquin J, Rhee KY, Park SJ, Hui D. Cryomilling application of graphene to improve material properties of graphene/chitosan nanocomposites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2013;45(1):682–7.10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.05.011Search in Google Scholar

[31] Rostami A, Vahdati M, Nowrouzi M, Karimpour M, Babaei A. Morphology and physico-mechanical properties of poly (methyl methacrylate)/polystyrene/polypropylene ternary polymer blend and its nanocomposites with organoclay: The effect of nature of organoclay and method of preparation. Polym Polym Compos. 2022;30:09673911221107811.10.1177/09673911221107811Search in Google Scholar

[32] Syafiq RMO, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM, Othman SH, Ilyas RA. Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):423–37.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0028Search in Google Scholar

[33] Molaabasi F, Zare Y, Rhee KY. Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):874–82.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0053Search in Google Scholar

[34] Pan S, Feng J, Safaei B, Qin Z, Chu F, Hui D. A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):1658–69.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0107Search in Google Scholar

[35] Song D, Wang B, Tao W, Wang X, Zhang W, Dai M, et al. Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):3020–30.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0480Search in Google Scholar

[36] Li H, Cheng B, Gao W, Feng C, Huang C, Liu Y, et al. Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):2928–64.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0484Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zare Y, Rhee KY, Park S-J. Predictions of micromechanics models for interfacial/interphase parameters in polymer/metal nanocomposites. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2017;79:111–6.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2017.09.015Search in Google Scholar

[38] Arjmandi SK, Khademzadeh Yeganeh J, Zare Y, Rhee KY. Development of Kovacs model for electrical conductivity of carbon nanofiber–polymer systems. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):7.10.1038/s41598-022-26139-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Zare Y, Rhee KY. Simulation of electrical conductivity for polymer silver nanowires systems. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):5.10.1038/s41598-022-25548-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Niyaraki MN, Mirzaei J, Taghipoor H. Evaluation of the effect of nanomaterials and fibers on the mechanical behavior of polymer-based nanocomposites using Box–Behnken response surface methodology. Polym Bull. 2023;80(9):9507–29.10.1007/s00289-022-04517-3Search in Google Scholar

[41] Chen B, Evans JR. Impact strength of polymer-clay nanocomposites. Soft Matter. 2009;5(19):3572–84.10.1039/b902073jSearch in Google Scholar

[42] Mostafapour A, Naderi G, Nakhaei MR. Effect of process parameters on fracture toughness of PP/EPDM/nanoclay nanocomposite fabricated by novel method of heat assisted friction stir processing. Polym Compos. 2018;39(7):2336–46.10.1002/pc.24214Search in Google Scholar

[43] Lim J, Hassan A, Rahmat A, Wahit M. Rubber-toughened polypropylene nanocomposite: Effect of polyethylene octene copolymer on mechanical properties and phase morphology. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;99(6):3441–50.10.1002/app.22907Search in Google Scholar

[44] Ramezani-Dakhel H, Garmabi H. A systematic study on notched impact strength of super-toughened polyamide 6 nanocomposites using response surface methodology. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;118(2):969–79.10.1002/app.32458Search in Google Scholar

[45] Nakhaei MR, Mostafapour A, Dubois C, Naderi G, Reza Ghoreishy MH. Study of morphology and mechanical properties of PP/EPDM/clay nanocomposites prepared using twin-screw extruder and friction stir process. Polym Compos. 2019;40(8):3306–14.10.1002/pc.25188Search in Google Scholar

[46] Xu Z, Zhang Z, Yin H, Hou S, Lin H, Zhou J, et al. Investigation on the role of different conductive polymers in supercapacitors based on a zinc sulfide/reduced graphene oxide/conductive polymer ternary composite electrode. RSC Adv. 2020;10(6):3122–9.10.1039/C9RA07842HSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Ehsani A, Heidari AA, Shiri HM. Electrochemical pseudocapacitors based on ternary nanocomposite of conductive polymer/graphene/metal oxide: an introduction and review to it in recent studies. Chem Rec. 2019;19(5):908–26.10.1002/tcr.201800112Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Zhang H, Zhang G, Tang M, Zhou L, Li J, Fan X, et al. Synergistic effect of carbon nanotube and graphene nanoplates on the mechanical, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of polymer composites and polymer composite foams. Chem Eng J. 2018;353:381–93.10.1016/j.cej.2018.07.144Search in Google Scholar

[49] Chen Y, Bai J, Yang D, Sun P, Li X. Excellent performance of flexible supercapacitor based on the ternary composites of reduced graphene oxide/molybdenum disulfide/poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene). Electrochim Acta. 2020;330:135205.10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135205Search in Google Scholar

[50] Kamińska G, Dudziak M, Kudlek E, Bohdziewicz J. Preparation, characterization and adsorption potential of grainy halloysite-CNT composites for anthracene removal from aqueous solution. Nanomaterials. 2019;9(6):890.10.3390/nano9060890Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Ling Y, Zhang P, Wang J, Taylor P, Hu S. Effects of nanoparticles on engineering performance of cementitious composites reinforced with PVA fibers. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):504–14.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0038Search in Google Scholar

[52] Li Z, Guo T, Chen Y, Liu Q, Chen Y. The properties of nano-CaCO3/nano-ZnO/SBR composite-modified asphalt. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):1253–65.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0082Search in Google Scholar

[53] Tiwari S, Gehlot CL, Srivastava D. Epoxy/Fly ash from Indian soil Chulha/nano CaCO3 nanocomposite: Studies on mechanical and thermal properties. Polym Compos. 2020;41(8):3237–49.10.1002/pc.25615Search in Google Scholar

[54] Shijie F, Jiefeng Z, Yunling G, Junxian Y. Polydopamine-CaCO3 modified superhydrophilic nanocomposite membrane used for highly efficient separation of oil-in-water emulsions. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2022;639:128355.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.128355Search in Google Scholar

[55] Rajan S, Marimuthu K, Ayyanar CB, Khan A, Siengchin S, Rangappa SM. In-vitro cytotoxicity of zinc oxide, graphene oxide, and calcium carbonate nano particulates reinforced high-density polyethylene composite. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;18:921–30.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.03.012Search in Google Scholar

[56] Gayer C, Ritter J, Bullemer M, Grom S, Jauer L, Meiners W, et al. Development of a solvent-free polylactide/calcium carbonate composite for selective laser sintering of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;101:660–73.10.1016/j.msec.2019.03.101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Peña-Parás L, Sánchez-Fernández JA, Vidaltamayo R. Nanoclays for biomedical applications. Handb Ecomater. 2018;5:3453–71.10.1007/978-3-319-68255-6_50Search in Google Scholar

[58] Murali A, Lokhande G, Deo KA, Brokesh A, Gaharwar AK. Emerging 2D nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Mater Today. 2021;50:276–302.10.1016/j.mattod.2021.04.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Gaharwar AK, Cross LM, Peak CW, Gold K, Carrow JK, Brokesh A, et al. 2D nanoclay for biomedical applications: Regenerative medicine, therapeutic delivery, and additive manufacturing. Adv Mater. 2019;31(23):1900332.10.1002/adma.201900332Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Wang Q, Mynar JL, Yoshida M, Lee E, Lee M, Okuro K, et al. High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and a dendritic molecular binder. Nature. 2010;463(7279):339–43.10.1038/nature08693Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Gaharwar AK, Peppas NA, Khademhosseini A. Nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111(3):441–53.10.1002/bit.25160Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Render D, Rangari VK, Jeelani S, Fadlalla K, Samuel T. Bio-based calcium carbonate (CaCO3) nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. Int J Biomed Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;3(3):221–35.10.1504/IJBNN.2014.065464Search in Google Scholar

[63] Seifan M, Sarabadani Z, Berenjian A. Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation to design a new type of bio self-healing dental composite. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104(5):2029–37.10.1007/s00253-019-10345-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Biradar S, Ravichandran P, Gopikrishnan R, Goornavar V, Hall JC, Ramesh V, et al. Calcium carbonate nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2011;11(8):6868–74.10.1166/jnn.2011.4251Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Fadia P, Tyagi S, Bhagat S, Nair A, Panchal P, Dave H, et al. Calcium carbonate nano-and microparticles: synthesis methods and biological applications. 3 Biotech. 2021;11:1–30.10.1007/s13205-021-02995-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Zeng Q, Yu A, Lu G, Paul D. Clay-based polymer nanocomposites: Research and commercial development. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2005;5(10):1574–92.10.1166/jnn.2005.411Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Zare Y, Garmabi H, Sharif F. Optimization of mechanical properties of PP/Nanoclay/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite using response surface methodology. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011;122:3188–200Search in Google Scholar

[68] Chen H, Wang M, Lin Y, Chan CM, Wu J. Morphology and mechanical property of binary and ternary polypropylene nanocomposites with nanoclay and CaCo3 particles. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;106(5):3409–16.10.1002/app.27017Search in Google Scholar

[69] Tang Y, Hu Y, Zhang R, Wang Z, Gui Z, Chen Z, et al. Investigation into poly (propylene)/montmorillonite/calcium carbonate nanocomposites. Macromol Mater Eng. 2004;289(2):191–7.10.1002/mame.200300157Search in Google Scholar

[70] Dai X, Shang Q, Jia Q, Li S, Xiu Y. Preparation and properties of HDPE/CaCO3/OMMT ternary nanocomposite. Polym Eng Sci. 2010;50(5):894–9.10.1002/pen.21608Search in Google Scholar

[71] Sadegh Roshanravan HG. Investigation of mechanical properties of PVC/nanoclay/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite. Amirkabir University of Technology; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Fornes T, Yoon P, Keskkula H, Paul D. Nylon 6 nanocomposites: The effect of matrix molecular weight. Polymer. 2001;42(25):09929–40.10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00552-3Search in Google Scholar

[73] Liu W, Hoa SV, Pugh M. Fracture toughness and water uptake of high-performance epoxy/nanoclay nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol. 2005;65(15–16):2364–73.10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.06.007Search in Google Scholar

[74] Zare Y, Garmabi H, Sharif F. Preparation and investigation of mechanical properties of PP/nanoclay/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite. MSc. dissertation. Amirkabir University of Technology; 2010.10.1002/app.34378Search in Google Scholar

[75] Asadi Z, Javadi A, Mohammadzadeh F, Alavi K. Investigation on the role of nanoclay and nano calcium carbonate on morphology, rheology, crystallinity and mechanical properties of binary and ternary nanocomposites based on PLA. Int J Polym Anal Charact. 2021;26(1):1–16.10.1080/1023666X.2020.1836459Search in Google Scholar

[76] Alavitabari S, Mohamadi M, Javadi A, Garmabi H. The effect of secondary nanofiller on mechanical properties and formulation optimization of HDPE/nanoclay/nanoCaCO3 hybrid nanocomposites using response surface methodology. J Vinyl Addit Technol. 2021;27(1):54–67.10.1002/vnl.21783Search in Google Scholar

[77] Ghari HS, Shakouri Z. Natural rubber hybrid nanocomposites reinforced with swelled organoclay and nano-calcium carbonate. Rubber Chem Technol. 2012;85(1):132–46.10.5254/1.3672436Search in Google Scholar

[78] Ghari HS, Arani AJ, Shakouri Z. Mixing sequence in natural rubber containing organoclay and nano–calcium carbonate ternary hybrid nanocomposites. Rubber Chem Technol. 2013;86(2):330–41.10.5254/rct.13.87967Search in Google Scholar

[79] Kapole SA, Kulkarni RD, Sonawane SH. Performance properties of acrylic and acrylic polyol–polyurethane based hybrid system via addition of nano-caco3 and nanoclay. Can J Chem Eng. 2011;89(6):1590–5.10.1002/cjce.20480Search in Google Scholar

[80] Zare Y, Rhee KY. A simulation work for the influences of aggregation/agglomeration of clay layers on the tensile properties of nanocomposites. JOM. 2019;71(11):3989–95.10.1007/s11837-019-03768-2Search in Google Scholar

[81] Zare Y. Modeling the yield strength of polymer nanocomposites based upon nanoparticle agglomeration and polymer–filler interphase. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;467:165–9.10.1016/j.jcis.2016.01.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Zarei Darani S, Naghdabadi R. An experimental study on multiwalled carbon nanotube nanocomposite piezoresistivity considering the filler agglomeration effects. Polym Compos. 2021;42(9):4707–16.10.1002/pc.26180Search in Google Scholar

[83] Kotal M, Bhowmick AK. Polymer nanocomposites from modified clays: Recent advances and challenges. Prog Polym Sci. 2015;51:127–87.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.10.001Search in Google Scholar

[84] Zare Y, Garmabi H. Nonisothermal crystallization and melting behavior of PP/nanoclay/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;124:1225–33.10.1002/app.35134Search in Google Scholar

[85] Sorrentino L, Berardini F, Capozzoli M, Amitrano S, Iannace S. Nano/micro ternary composites based on PP, nanoclay, and CaCO3. J Appl Polym Sci. 2009;113(5):3360–7.10.1002/app.30241Search in Google Scholar

[86] Huang JW. Poly (butylene terephthalate)/clay nanocomposite compatibilized with poly (ethylene-co-glycidyl methacrylate). I. Isothermal crystallization. J Appl Polym Sci. 2008;110(4):2195–204.10.1002/app.28819Search in Google Scholar

[87] Chan CM, Wu J, Li JX, Cheung YK. Polypropylene/calcium carbonate nanocomposites. Polymer. 2002;43(10):2981–92.10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00120-9Search in Google Scholar

[88] Thio Y, Argon A, Cohen R, Weinberg M. Toughening of isotactic polypropylene with CaCO3 particles. Polymer. 2002;43(13):3661–74.10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00193-3Search in Google Scholar

[89] Avella M, Cosco S, Di Lorenzo M, Di Pace E, Errico M, Gentile G. Nucleation activity of nanosized CaCO3 on crystallization of isotactic polypropylene, in dependence on crystal modification, particle shape, and coating. Eur Polym J. 2006;42(7):1548–57.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2006.01.009Search in Google Scholar

[90] Medellín-Rodríguez F, Mata-Padilla J, Hsiao B, Waldo-Mendoza M, Ramírez-Vargas E, Sánchez-Valdes S. The effect of nanoclays on the nucleation, crystallization, and melting mechanisms of isotactic polypropylene. Polym Eng Sci. 2007;47(11):1889–97.10.1002/pen.20902Search in Google Scholar

[91] Zare Y. Recent progress on preparation and properties of nanocomposites from recycled polymers: A review. Waste Manag. 2012;33:598–604.10.1016/j.wasman.2012.07.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Roghani-Mamaqani H, Haddadi-Asl V, Najafi M, Salami-Kalajahi M. Preparation of nanoclay-dispersed polystyrene nanofibers via atom transfer radical polymerization and electrospinning. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011;120(3):1431–8.10.1002/app.33119Search in Google Scholar

[93] Hatami L, Haddadi-Asl V, Roghani-Mamaqani H, Ahmadian-Alam L, Salami-Kalajahi M. Synthesis and characterization of poly (styrene-co-butyl acrylate)/clay nanocomposite latexes in miniemulsion by AGET ATRP. Polym Compos. 2011;32(6):967–75.10.1002/pc.21115Search in Google Scholar

[94] Khezri K, Haddadi-Asl V, Roghani-Mamaqani H, Salami-Kalajahi M. Synthesis and characterization of exfoliated poly (styrene-co-methyl methacrylate) nanocomposite via miniemulsion atom transfer radical polymerization: an activators generated by electron transfer approach. Polym Compos. 2011;32:1979–8710.1002/pc.21229Search in Google Scholar

[95] Weon JI, Gam KT, Boo WJ, Sue HJ, Chan CM. Impact-toughening mechanisms of calcium carbonate-reinforced polypropylene nanocomposite. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;99(6):3070–6.10.1002/app.22909Search in Google Scholar

[96] Lin Y, Chen H, Chan C-M, Wu J. High impact toughness polypropylene/CaCO3 nanocomposites and the toughening mechanism. Macromolecules. 2008;41(23):9204–13.10.1021/ma801095dSearch in Google Scholar

[97] Wang D, Min K. In-line monitoring and analysis of polymer melting behavior in an intermeshing counter-rotating twin-screw extruder by ultrasound waves. Polym Eng Sci. 2005;45(7):998–1010.10.1002/pen.20364Search in Google Scholar

[98] Peng W, Rhim S, Zare Y, Rhee KY. Effect of “Z” factor for strength of interphase layers on the tensile strength of polymer nanocomposites. Polym Compos. 2019;40(3):1117–22.10.1002/pc.24813Search in Google Scholar

[99] Zare Y, Rhee KY. Dependence of Z parameter for tensile strength of multi-layered interphase in polymer nanocomposites to material and interphase properties. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12(1):1–7.10.1186/s11671-017-1830-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[100] Razavi R, Zare Y, Rhee KY. A two-step model for the tunneling conductivity of polymer carbon nanotube nanocomposites assuming the conduction of interphase regions. RSC Adv. 2017;7(79):50225–33.10.1039/C7RA08214BSearch in Google Scholar

[101] Zare Y, Rhee KY. Simulation of Tensile Strength for Halloysite Nanotube-Filled System. JOM. 2022;75:1–11.10.1007/s11837-022-05488-6Search in Google Scholar

[102] Zare Y, Rhee KY. An innovative model for conductivity of graphene-based system by networked nano-sheets, interphase and tunneling zone. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–9.10.1038/s41598-022-19479-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[103] Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Zare Y, Gharib N, Rhee KY. Effect of interphase region on the Young’s modulus of polymer nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals. Surf Interfaces. 2023;39:102922.10.1016/j.surfin.2023.102922Search in Google Scholar

[104] Jahan N, Mighri F, Rodrigue D, Ajji A. Synergistic improvement of piezoelectric properties of PVDF/CaCO3/montmorillonite hybrid nanocomposites. Appl Clay Sci. 2018;152:93–100.10.1016/j.clay.2017.10.036Search in Google Scholar

[105] Ayaz M. Evaluation of the impact and flexural strength of PP/clay/CaCO3/MAPP ternary nanocomposites by application of full factorial design of experiment. J Thermoplast Compos Mater. 2018;34:0892705718808566.10.1177/0892705718808566Search in Google Scholar

[106] Ahmed T, Ya HH, Khan R, Hidayat Syah Lubis AM, Mahadzir S. Pseudo-ductility, morphology and fractography resulting from the synergistic effect of CaCO3 and bentonite in HDPE polymer nano composite. Materials. 2020;13(15):3333.10.3390/ma13153333Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[107] Awan MO, Shakoor A, Rehan MS, Gill YQ. Development of HDPE composites with improved mechanical properties using calcium carbonate and NanoClay. Phys B: Condens Matter. 2021;606:412568.10.1016/j.physb.2020.412568Search in Google Scholar

[108] Box GEP, Draper NR. Empirical model-building and response surfaces. USA: John Wiley & Sons; 1987.Search in Google Scholar

[109] Saeb M, Garmabi H. Investigation of styrene-assisted free-radical grafting of glycidyl methacrylate onto high-density polyethylene using response surface method. J Appl Polym Sci. 2009;111(3):1600–5.10.1002/app.29123Search in Google Scholar

[110] Zare Y, Garmabi H. Analysis of tensile modulus of PP/nanoclay/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite using composite theories. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;123:2309–19.10.1002/app.34741Search in Google Scholar

[111] Zare Y, Garmabi H. A developed model to assume the interphase properties in a ternary polymer nanocomposite reinforced with two nanofillers. Compos Part B: Eng. 2015;75:29–35.10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.01.031Search in Google Scholar

[112] Zare Y, Rhee K, Park S-J. Simple models for interphase characteristics in polypropylene/montmorillonite/CaCO3 nanocomposites. Phys Mesomech. 2020;23(2):182–8.10.1134/S1029959920020101Search in Google Scholar

[113] Zare Y, Rhee KY. Development of Hashin-Shtrikman model to determine the roles and properties of interphases in clay/CaCO3/PP ternary nanocomposite. Appl Clay Sci. 2017;137:176–82.10.1016/j.clay.2016.12.033Search in Google Scholar

[114] Zare Y, Garmabi H. Modeling of interfacial bonding between two nanofillers (montmorillonite and CaCO3) and a polymer matrix (PP) in a ternary polymer nanocomposite. Appl Surf Sci. 2014;321:219–25.10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.09.156Search in Google Scholar

[115] Zhang QX, Yu ZZ, Xie XL, Mai YW. Crystallization and impact energy of polypropylene/CaCO3 nanocomposites with nonionic modifier. Polymer. 2004;45(17):5985–94.10.1016/j.polymer.2004.06.044Search in Google Scholar

[116] Krishnamoorti R, Yurekli K. Rheology of polymer layered silicate nanocomposites. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;6(5–6):464–70.10.1016/S1359-0294(01)00121-2Search in Google Scholar

[117] Solomon MJ, Almusallam AS, Seefeldt KF, Somwangthanaroj A, Varadan P. Rheology of polypropylene/clay hybrid materials. Macromolecules. 2001;34(6):1864–72.10.1021/ma001122eSearch in Google Scholar

[118] Lian X, Mou W, Kuang T, Liu X, Zhang S, Li F, et al. Synergetic effect of nanoclay and nano-CaCO3 hybrid filler systems on the foaming properties and cellular structure of polystyrene nanocomposite foams using supercritical CO2. Cell Polym. 2020;39(5):185–202.10.1177/0262489319900948Search in Google Scholar

[119] Mohammad Mehdipour N, Garmabi H, Jamalpour S. Effect of nanosize CaCO3 and nanoclay on morphology and properties of linear PP/branched PP blend foams. Polym Compos. 2019;40(S1):E227–41.10.1002/pc.24611Search in Google Scholar

[120] Schmitt H, Creton N, Prashantha K, Soulestin J, Lacrampe MF, Krawczak P. Preparation and characterization of plasticized starch/halloysite porous nanocomposites possibly suitable for biomedical applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132(4):1–9.10.1002/app.41341Search in Google Scholar

[121] Bužarovska A, Dinescu S, Lazar AD, Serban M, Pircalabioru GG, Costache M, et al. Nanocomposite foams based on flexible biobased thermoplastic polyurethane and ZnO nanoparticles as potential wound dressing materials. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;104:109893.10.1016/j.msec.2019.109893Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[122] Delabarde C, Plummer CJ, Bourban P-E, Månson J-AE. Biodegradable polylactide/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite foam scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2012;23(6):1371–85.10.1007/s10856-012-4619-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption