Abstract

Pure and Ag@AgCl modified TiO2 were synthesized by one-step hydrothermal method, which exhibit anatase/rutile/brookite (A/R/B) triphasic structure. The photocatalysts were characterized by X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscope, transmission electron microscope, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, photoluminescence, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, photocurrent response, and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, and the photocatalytic activity was evaluated by taking 100 mL (10 mg/L) methylene blue (MB) aqueous solution as the target pollutant. The results show that Ag@AgCl modification is beneficial for the separation of photogenerated charges and the absorption in visible region. The degradation degree of MB increases from 75.7% for pure TiO2 to 97.3% for Ag@AgCl modified TiO2.

1 Introduction

As one of the new green environmental protection technologies, photocatalytic technology can be applied for the degradation of organic pollutants [1,2,3,4,5]. Among many photocatalytic materials, TiO2 shows the advantages of low cost, mild reaction conditions, high chemical stability, and no secondary pollution [6,7,8,9,10]. However, due to the shortcomings of TiO2, such as low sunlight utilization and fast recombination of photogenerated charges, its photocatalytic degradation effect is greatly limited [11,12,13]. When noble-metals and semiconductors are combined, Schottky junctions will be formed on the interfaces, which promote the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. On the other hand, the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of noble-metal can enhance visible light absorption, advancing the photocatalytic performance [14,15,16,17]. Moreover, Ag@AgCl modification can further improve the photocatalytic activity on the basis of Ag modification. Wang et al. [18] prepared Ag@AgCl/TiO2 photocatalyst and found that the recombination of photoinduced electrons and holes is retarded and the absorption in visible region is enhanced through Ag@AgCl modification. Therefore, Ag@AgCl/TiO2 shows higher photocatalytic activity than pure TiO2 and Ag/TiO2.

It is generally believed that TiO2 with mixed crystal exhibits better photocatalytic performance than single structure owing to the mixed crystal effect. Anatase/rutile TiO2 is the focus of mixed TiO2 and has been widely studied. Basis of two-phase mixed crystal, anatase/rutile/brookite triphasic TiO2 exhibits higher photocatalytic activity than two-phase and monophase TiO2 [19,20,21]. It is reported by Mutuma et al. [22] that the photocatalytic activity of anatase/rutile/brookite three-phase mixed crystal TiO2 is higher than that of anatase/rutile two-phase mixed crystal TiO2.

In our previous work, it has been proved that the anatase/rutile/brookite triphase TiO2 shows better activity than two-phase and monophase TiO2 [20]. In the present work, the advantages of TiO2 with triphase and Ag@AgCl modification were combined to prepare Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite TiO2 composite by one-step hydrothermal method. The effect of Ag@AgCl modification on the structure and photocatalytic performance of anatase/rutile/brookite triphasic TiO2 were investigated.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of photocatalyst materials

Polyethylene glycol (analytical reagent, AR), butyl titanate (AR), anhydrous ethanol (AR), hydrochloric acid (AR), silver nitrate (AR), and methylene blue (MB) (AR) were purchased from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagent Factory (PR China).

10 mL of butyl titanate was added to 30 mL anhydrous ethanol to obtain solution A. 30 mL of deionized water, 1 mL of hydrochloric acid, and 1 mL of polyethylene glycol were mixed evenly to obtain solution B, which was added to solution A dropwise to obtain a mixture. Then, the mixture was transferred to a hydrothermal reaction kettle for hydrothermal treatment at 190°C for 15 h. The obtained powder was washed several times to neutral, and dried at 80°C in an oven. Finally, after grinding, the pure TiO2 was prepared, which is marked as ARB.

Ag@AgCl modified TiO2 marked as Ag@AgCl–ARB can be obtained by adding certain amount of AgNO3 in solution B, and keeping the other steps same as the preparation procedure of ARB. The molar ratio of Ag/Ti is 2%.

2.2 Characterization

The crystal structure and phase information were studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a DX-2700 X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation as the X-ray source, the scan range 2θ was 20–70° and scan speed was 0.06°/s (Dandong Haoyuan Instrument Co. Ltd, Dandong, China). The morphology was observed by a JEM-F200 transmission electron microscope (TEM and HRTEM) and a Hitachi SU8220 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA). The composition and valence of elements were analyzed by an XSAM800 multifunctional surface analysis system (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, XPS) (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha, Kratos Ltd, Manchester, UK). The photoluminescence (PL) spectra were measured using an F-4600 fluorescence spectrum analyzer with an Xe lamp at an excitation wavelength of 320 nm (Shimadzu Group Company, Kyoto, Japan). The photocurrent response (PC) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were measured by a DH-7000 electrochemical workstation (Beijing Jinyang Wanda Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China). The optical absorption was analyzed by a UV-3600 ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Group Company, Kyoto, Japan).

2.3 Photocatalytic activity test

The photocatalytic activity of samples was evaluated by measuring the decomposition of MB. 100 mL of 10 mg/L MB aqueous solution and 0.05 g sample powder were mixed together and stirred in dark for 30 min to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium. Then, the irradiation was carried out using a 250 W Xe lamp as the light source. After centrifugal separation, the solution was taken every 15 min and the absorbance at 664 nm was measured. The degradation degree was calculated by formula (A 0 – A t )/A0 × 100%.

On the basis of the MB degradation system, 2 mL (0.1 mol/L) of p-benzoquinone (BQ, ·

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phase composition

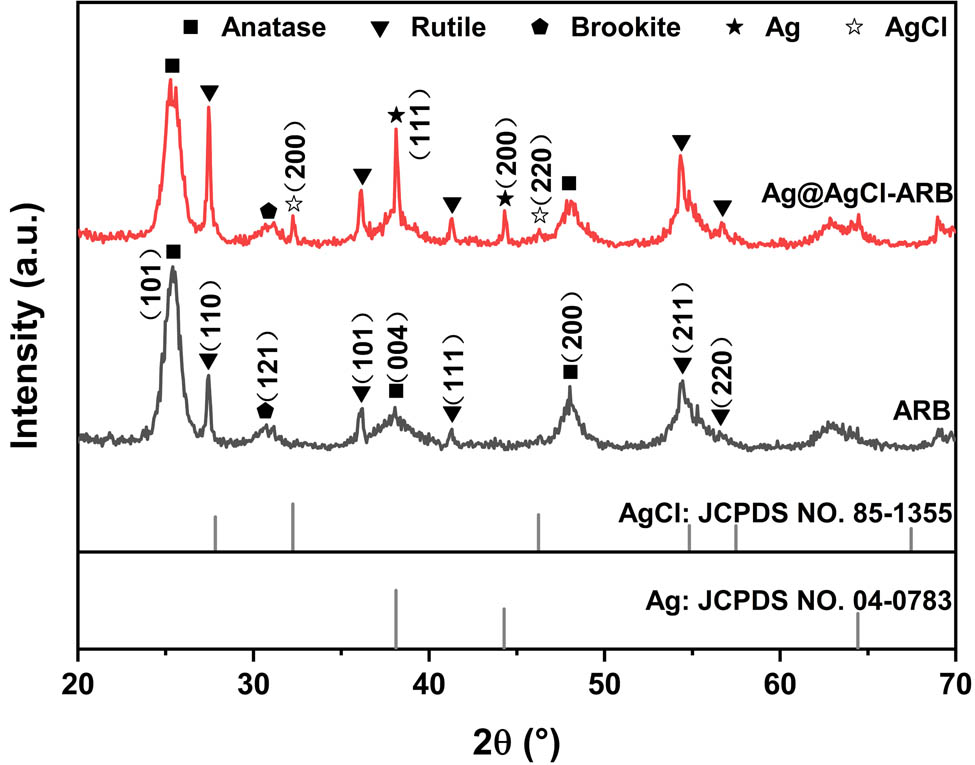

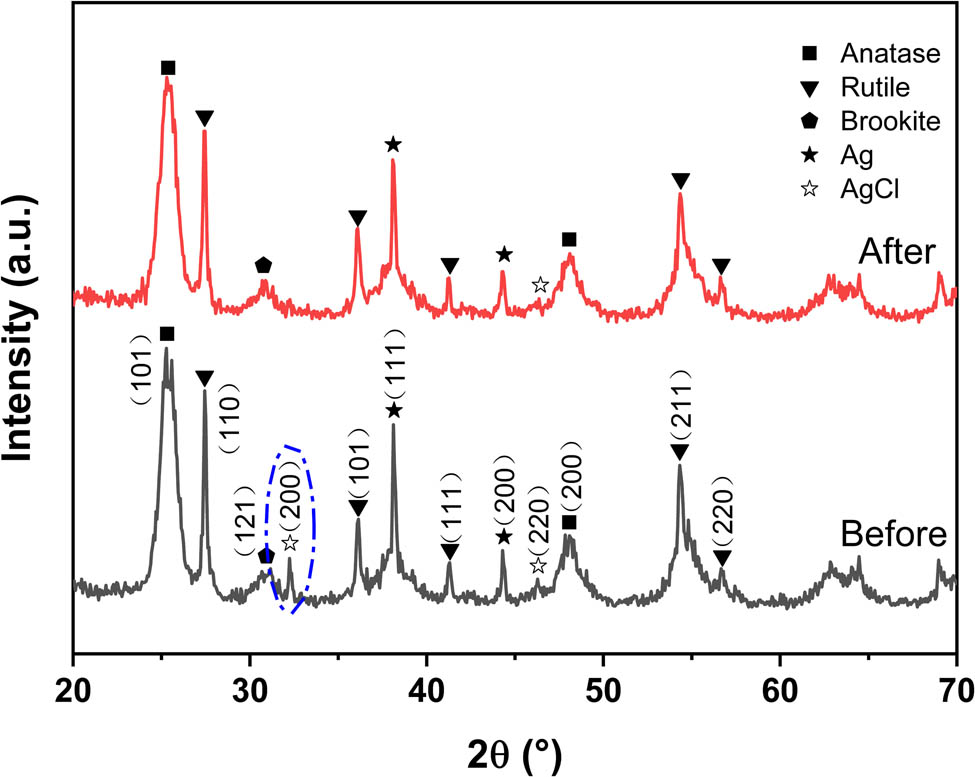

Figure 1 presents the XRD patterns of samples. The diffraction peaks of ARB at 25.4, 38.0, and 48.0° are indexed to the (101), (004), and (200) planes of anatase. The diffraction peaks at 27.4, 36.2, 41.3, 54.4, and 56.6° are indexed to the (110), (101), (111), (211), and (220) planes of rutile. In addition, the diffraction peak corresponding to the (121) planes of brookite appears at 31.1°, implying that the prepared ARB is composed of three phases, namely, anatase, rutile, and brookite [23]. As for Ag@AgCl–ARB, besides the anatase, rutile, and brookite phase, new diffraction peaks at 38.1 and 44.4° are indexed to the (111) and (200) planes of metallic Ag [24], and peaks at 32.3 and 46.3° correspond to the (200) and (220) planes of AgCl, respectively [19].

XRD patterns of the samples.

3.2 Morphology

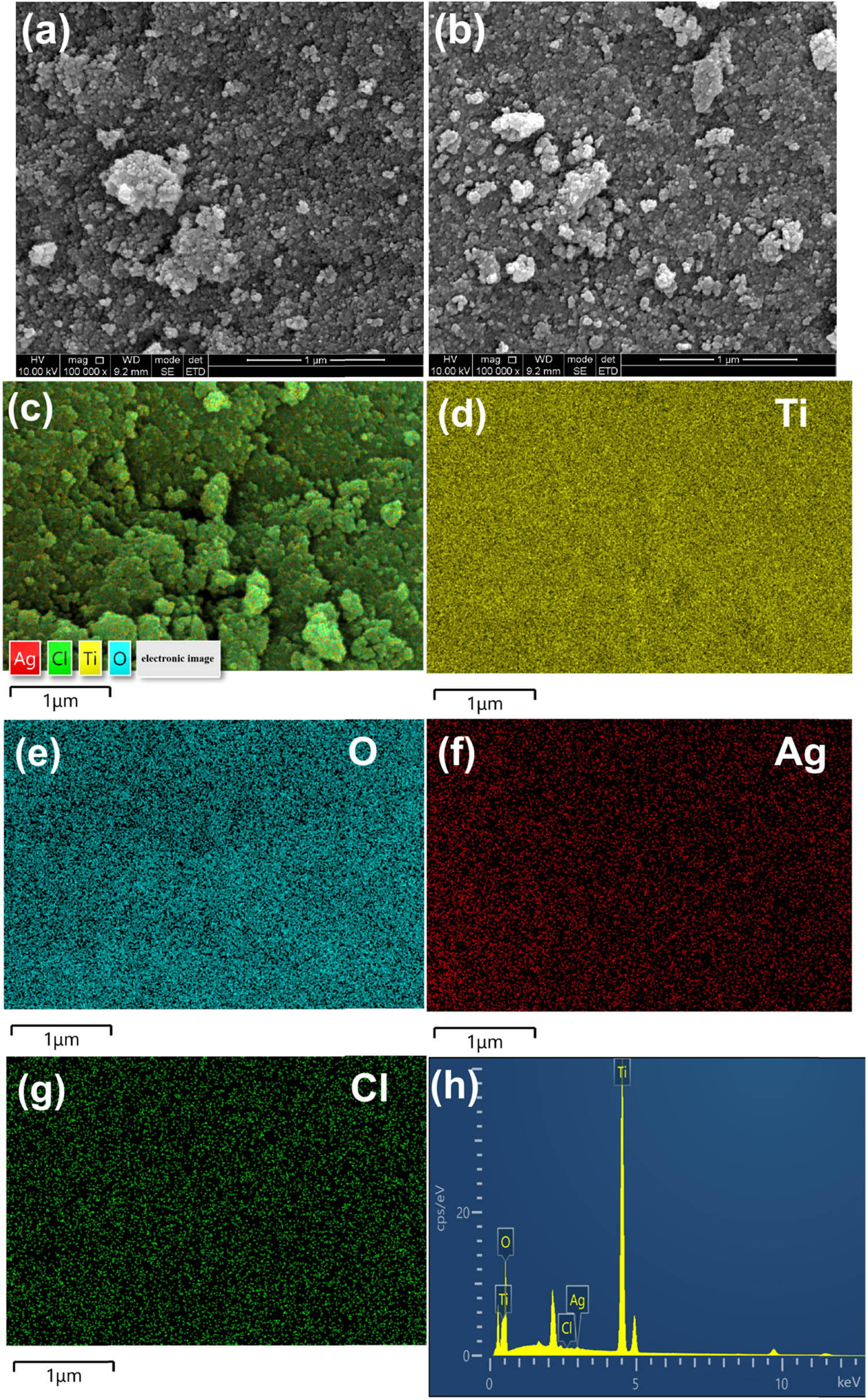

Figure 2 depicts the SEM images of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB. Both the samples are irregular in shape and ranging in size from ten to tens of nanometers. ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB present almost the same morphology, implying that Ag@AgCl modification has no distinct influence on the morphology. Figure 2(c) and (h) are the element mappings of Ag@AgCl–ARB. The Ag@AgCl–ARB is mainly composed of Ti, O, Ag, and Cl, distributed uniformly in the sample, which demonstrates that Ag and Cl elements are present in Ag@AgCl–ARB.

SEM images of ARB (a), Ag@AgCl–ARB (b), element mappings (c–g), and EDS analysis of Ag@AgCl–ARB (h).

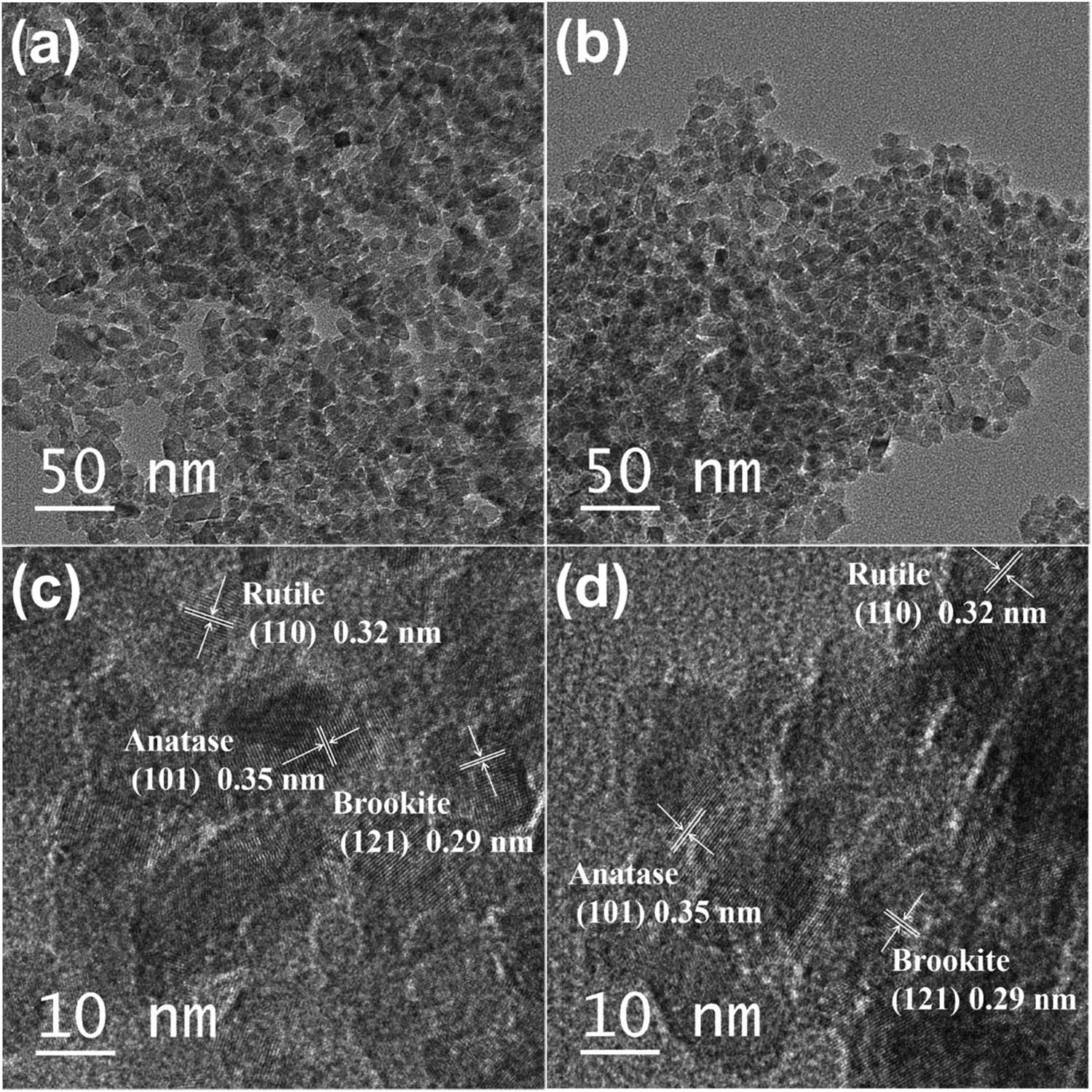

Figure 3 shows TEM and HRTEM images of the samples. From Figure 3(a), it can be observed that the single particle is roughly granular, and the size is between 10–20 nm. The crystal plane spacings marked in Figure 3(c) 0.35, 0.32, and 0.29 nm can be attributed to the (101) plane of anatase, the (110) plane of rutile, and the (121) plane of brookite [20,25,26], respectively, indicating that ARB consists of anatase, rutile, and brookite phase, which is in accordance with the XRD results. Figure 3(d) shows the HRTEM images of Ag@AgCl–ARB, the crystal lattice fringes 0.35, 0.32, and 0.29 nm correspond to the crystal plane of anatase (101), rutile (110), and brookite (121), respectively.

TEM images of ARB (a), Ag@AgCl–ARB (b), HRTEM images of ARB (c), and Ag@AgCl–ARB (d).

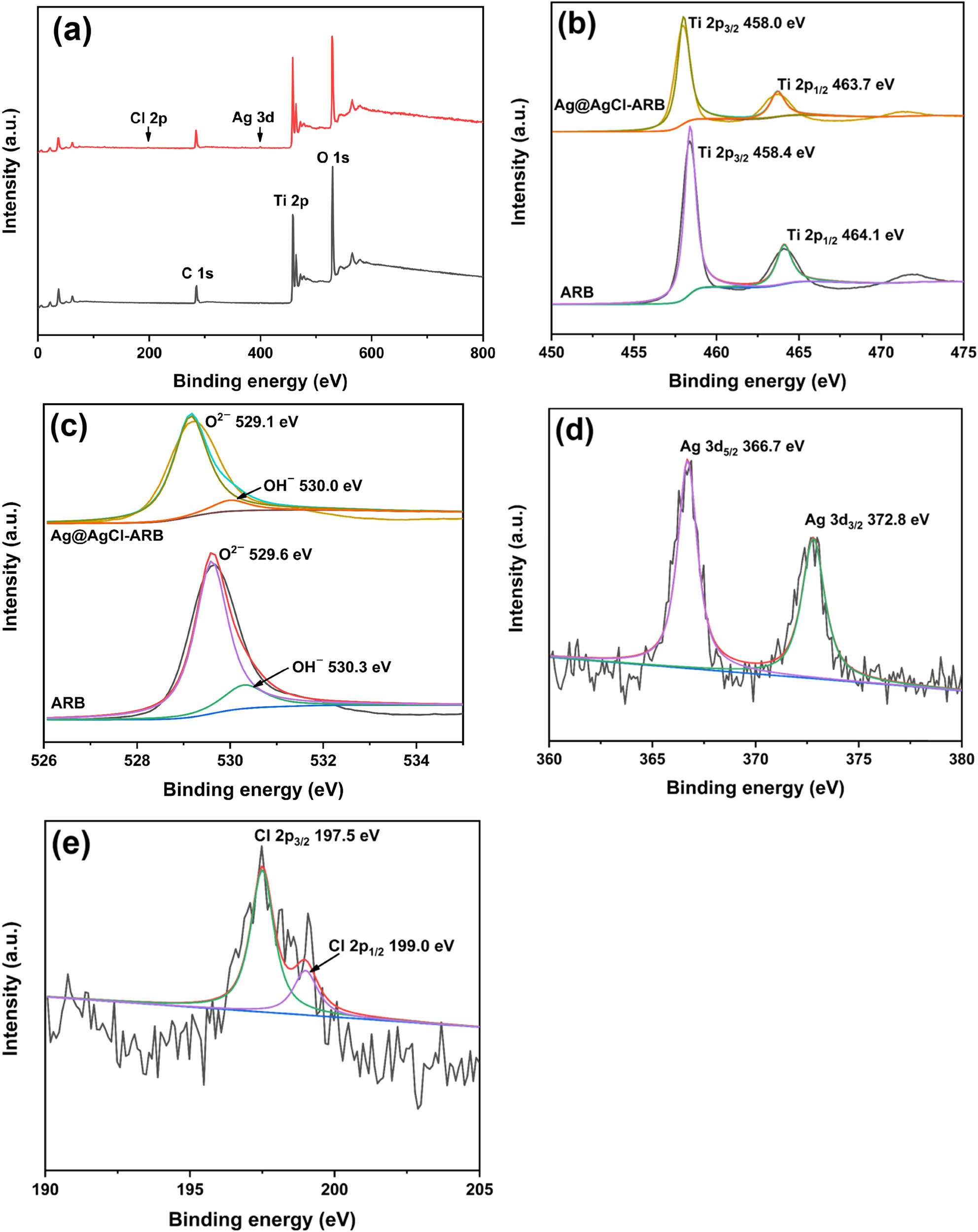

3.3 Element composition

Figure 4(a) shows the full XPS spectra of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB. The Ag@AgCl–ARB is mainly composed of Ti, O, Ag, and Cl. No other impurity peaks were detected in ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB, indicating the high purity of samples. Figure 4(b) shows the high resolution spectra of Ti 2p. Two peaks at 458.4 and 464.1 eV in the spectrum of ARB are indexed to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2, verifying that the Ti element exists in 4+ valence state [27,28]. In Figure 4(c), the O 1s peaks of ARB are located at 529.6 and 530.3 eV, corresponding to lattice oxygen (O2−) and surface hydroxyl group (OH−), respectively [28]. After Ag@AgCl modification, the binding energies of Ti 2p and O 1s shift to lower position, which can be ascribed to the interaction between Ag, Cl elements, and Ti, O elements [29,30]. The peaks at Ag 3d5/2 366.7 and Ag 3d3/2 372.8 eV are attributed to metals Ag0 and Ag+ in Figure 4(d) [31,32]. As demonstrated in Figure 4(e), the characteristic peaks of Cl 2p3/2 and Cl 2p1/2 of Cl element are located at 197.5 and 199.0 eV, respectively, which indicate that Cl element is in −1 valence state [31].

XPS survey of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB (a), high resolution spectra of Ti 2p (b), O 1 s (c), Ag 3d (d), and Cl 2p (e).

3.4 Photogenerated charges separation analysis

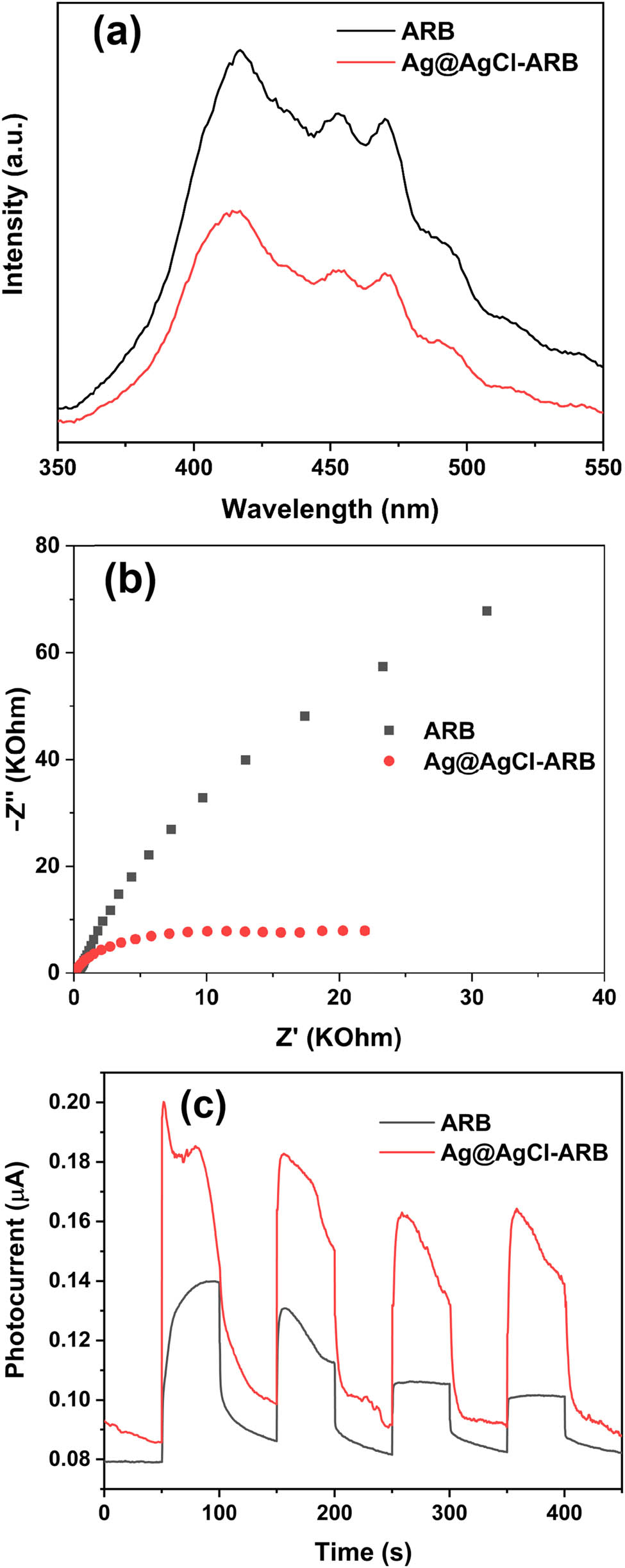

Figure 5(a) shows the PL spectra of samples. Since the PL peaks are responsible for the recombination between photogenerated electrons and holes, the stronger the PL peak intensity, the higher the recombination of photogenerated charge [33]. Compared with ARB, although the PL peak positions of Ag@AgCl modified ARB does not change, the peak intensity is significantly lower than that of ARB, implying that Ag@AgCl modification retards the recombination effectively.

PL spectra (a), EIS (b), and PC curves (c) of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB.

Figure 5(b) shows the EIS Nyquist plots of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB. According to Nyquist theorem, the arc radius of Ag@AgCl–ARB is smaller than ARB, which indicates that Ag@AgCl–ARB possesses lower charge movement resistance [34,35,36]. Figure 5(c) shows the PC curves of samples. Generally, the higher the photocurrent, the stronger the photoinduced electrons and holes separation ability [35,37]. Both ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB produce photocurrent under light irradiation. Nevertheless, Ag@AgCl–ARB shows higher photocurrent density, implying that Ag@AgCl modification is beneficial to the separation of photoinduced charges. The electrochemical test results are consistent with PL spectra.

3.5 Optical absorption analysis

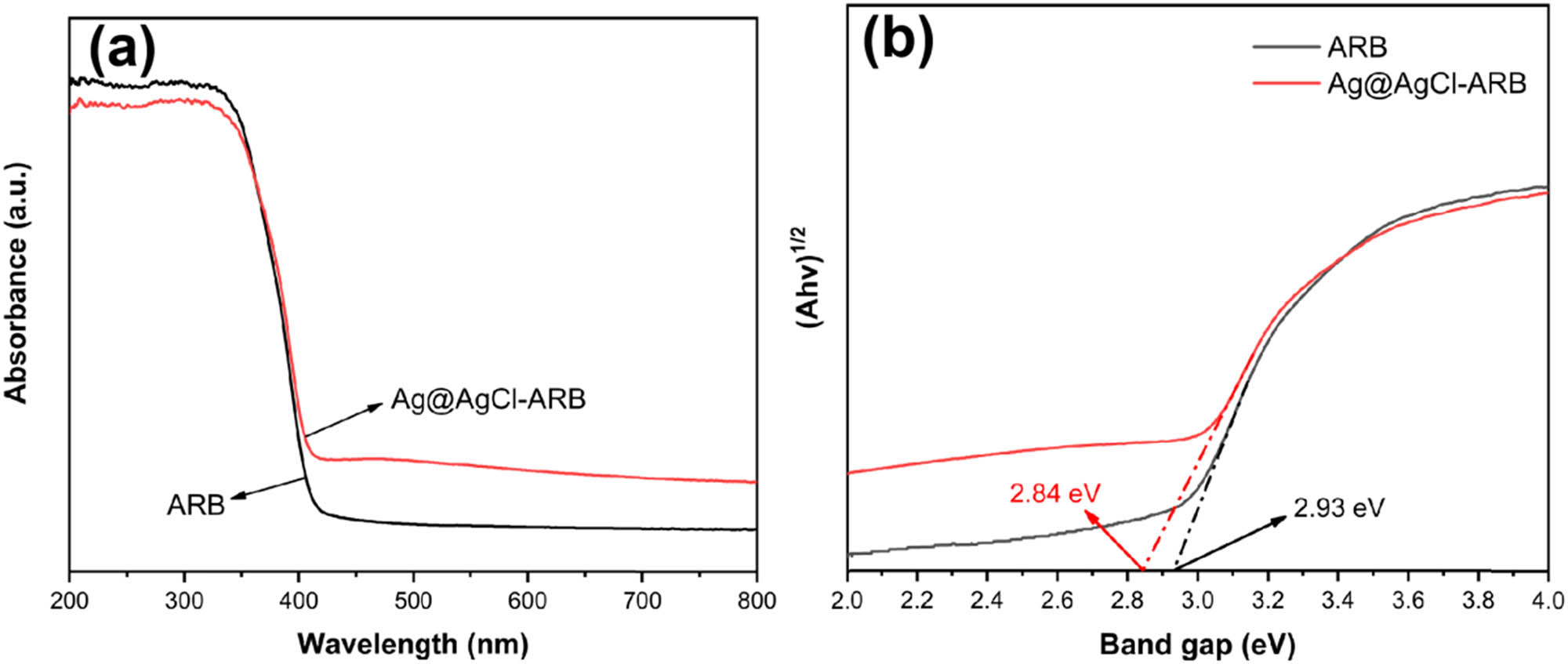

Figure 6 presents the UV-visible absorption spectra and band gap of the samples. It can be found in Figure 6(a) that the absorption edges of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB are basically the same, both showing absorption edges at 400 nm approximately. Figure 6(b) shows the (αhv)1/2–hv curves of the samples. The band gap width of the semiconductor can be estimated by Tauc-plot [38,39,40]. The gap width of Ag@AgCl–ARB (2.84 eV) is smaller than that of ARB (2.93 eV). In the visible region, Ag@AgCl–ARB shows higher absorption than that of ARB, indicating that the plasma resonance effect caused by Ag particles is beneficial to increasing the absorption of visible light [41].

UV-visible absorption spectra (a) and band gap (b) of the samples.

3.6 Photocatalytic activity

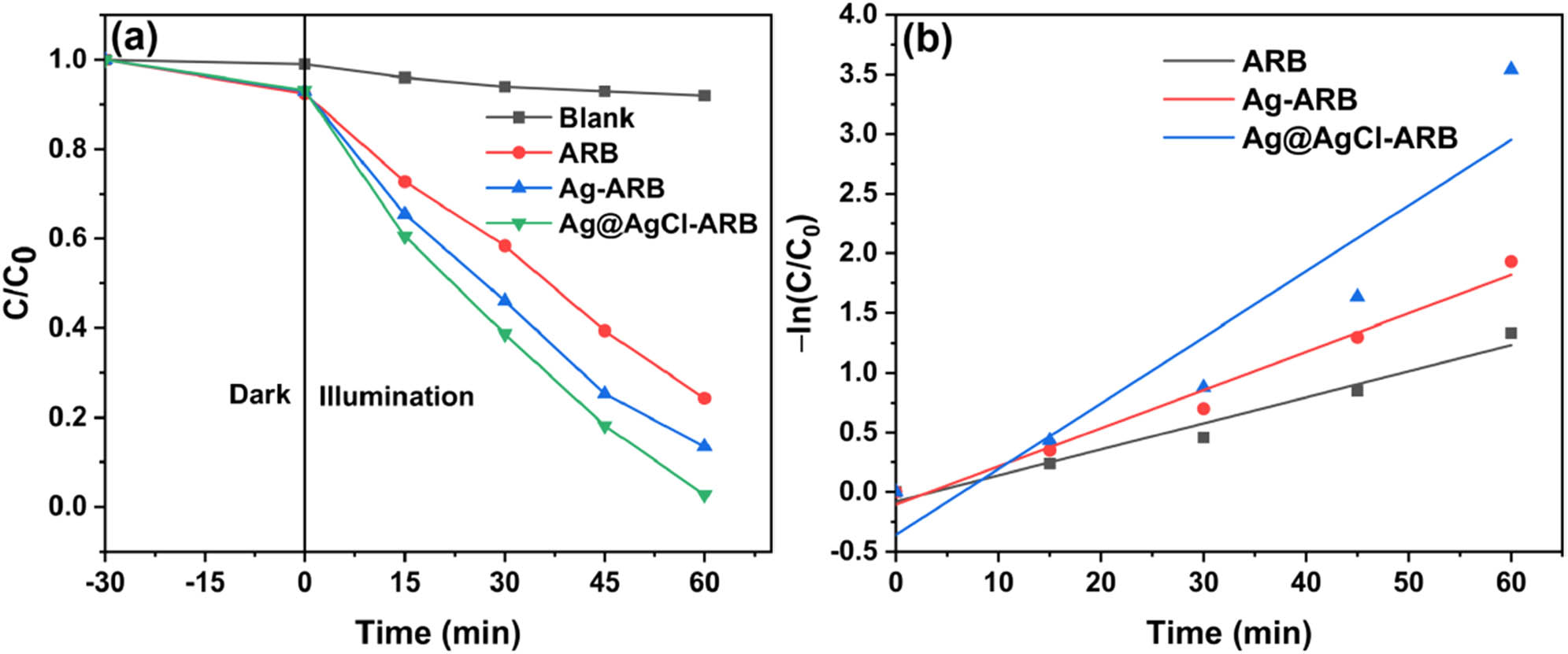

Figure 7(a) presents the degradation degree curves of MB. The self-degradation of MB without photocatalyst is 8%, which is relatively low in the degradation process. Therefore, the degradation of MB is mainly derived from the presence of photocatalysts under irradiation. After illumination for 60 min, the degradation degree of MB by ARB is 75.7%, and it is 97.3% for Ag@AgCl–ARB, indicating that the photocatalytic efficiency is significantly improved for Ag@AgCl modification. For comparison, Ag–ARB (Ag/Ti = 2%) was prepared, which shows a degradation degree of 86.5%. It is proved that Ag modification improves the photocatalytic activity of TiO2, but the effect is inferior to Ag@AgCl modification.

Degradation degree curves (a) and kinetic curves (b) of ARB, Ag-ARB, and Ag@AgCl–ARB.

The kinetics fitting results are shown in Figure 7(b). It can be found that the time t shows a linear relationship with –ln(C/C0), which suggests that the reaction of photocatalytic degradation of MB conforms to the first-order reaction [42]. The higher the reaction rate constant, the higher the photocatalytic activity. The first-order reaction rate constants of ARB, Ag–ARB, and Ag@AgCl–ARB are 0.022, 0.032, and 0.055 min−1, respectively. Ag@AgCl–ARB shows the highest k value, which is in line with the photocatalytic degradation results.

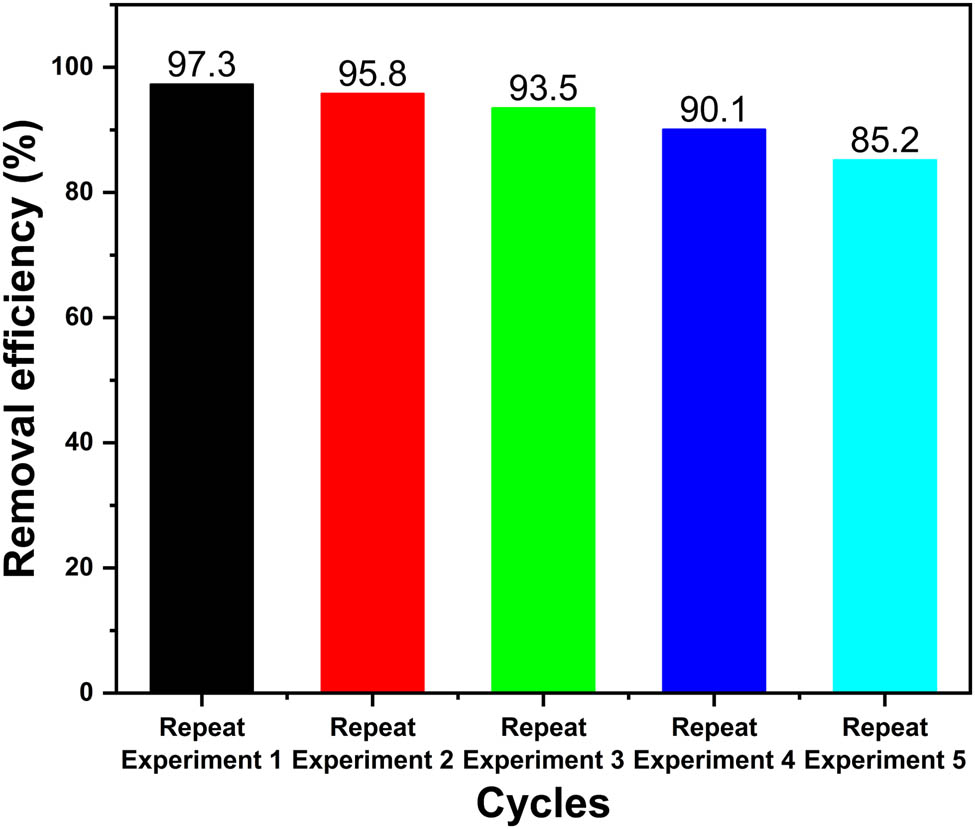

To study the reusability of Ag@AgCl–ARB photocatalyst, the cycling experiment of degradation MB was carried out. The experimental results are shown in Figure 8. As the number of cycles increases, the degradation degree of MB decreases slightly. After 5 cycles, the degradation degree of Ag@AgCl–ARB composite decreases from 97.3 to 85.2%.

The reuse experiment of Ag@AgCl–ARB photocatalyst for MB degradation.

The XRD pattern of Ag@AgCl–ARB composite photocatalyst after five cycles is shown in Figure 9. Compared with the initial sample, it is found that the diffraction peak intensity of AgCl (200) crystal plane at 32.3° decreases after cycle experiment, implying that part of AgCl is decomposed during the photocatalytic experiment [43]. The positions of other peaks are unchanged; however, the peak intensity decreases slightly, which may be caused by a small amount of undegraded MB molecules covering the surface of Ag@AgCl–ARB [44,45]. Meanwhile, it also causes the decline in photocatalytic activity, which is consistent with the cycling experimental results.

XRD patterns of Ag@AgCl–ARB photocatalyst before and after the photocatalytic experiment.

Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer was used to investigate the silver ion leached out from the photocatalyst in the supernatant after reaction. It is measured to be 0.0660 ± 0.0003 mg/L in the solution, indicating that a small amount of Ag ion was leached into the solution.

3.7 Photodegradation mechanism

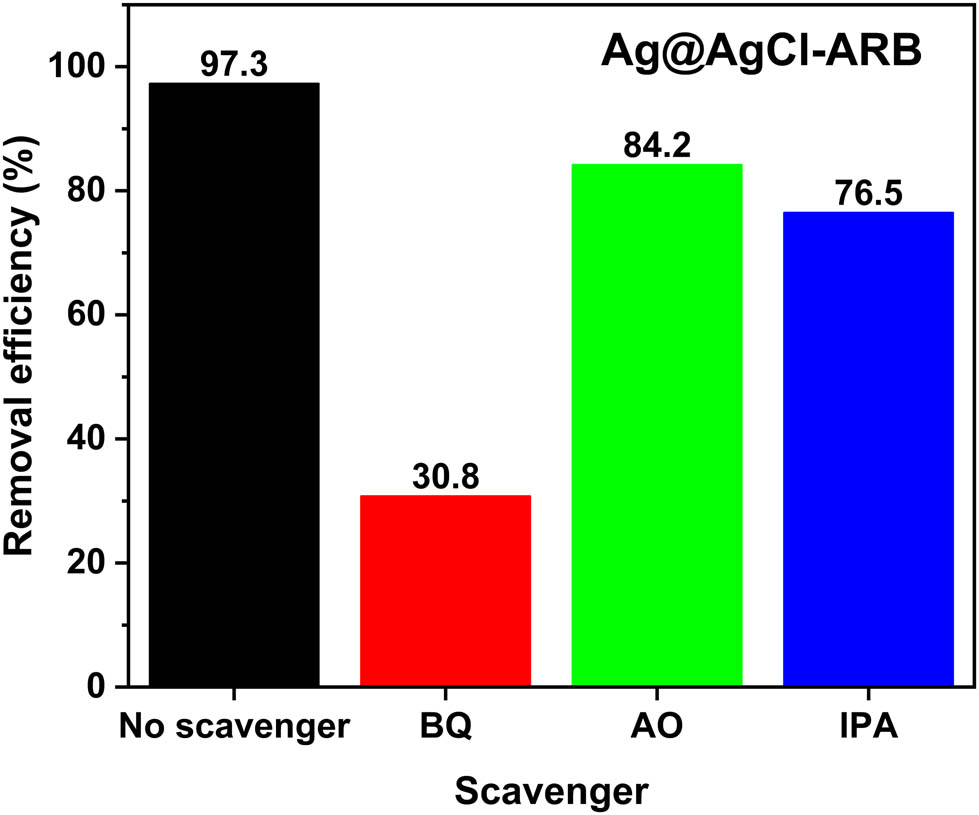

Figure 10 shows the results of active group capture experiment of Ag@AgCl–ARB. After adding BQ, IPA, and AO in MB degradation system, the order of photocatalytic degradation degrees of MB in the samples are BQ (30.8%) < IPA (76.5%) < AO (84.2%) < no Scavenger (97.3%), which suggests that ·

Active species experiment of Ag@AgCl–ARB.

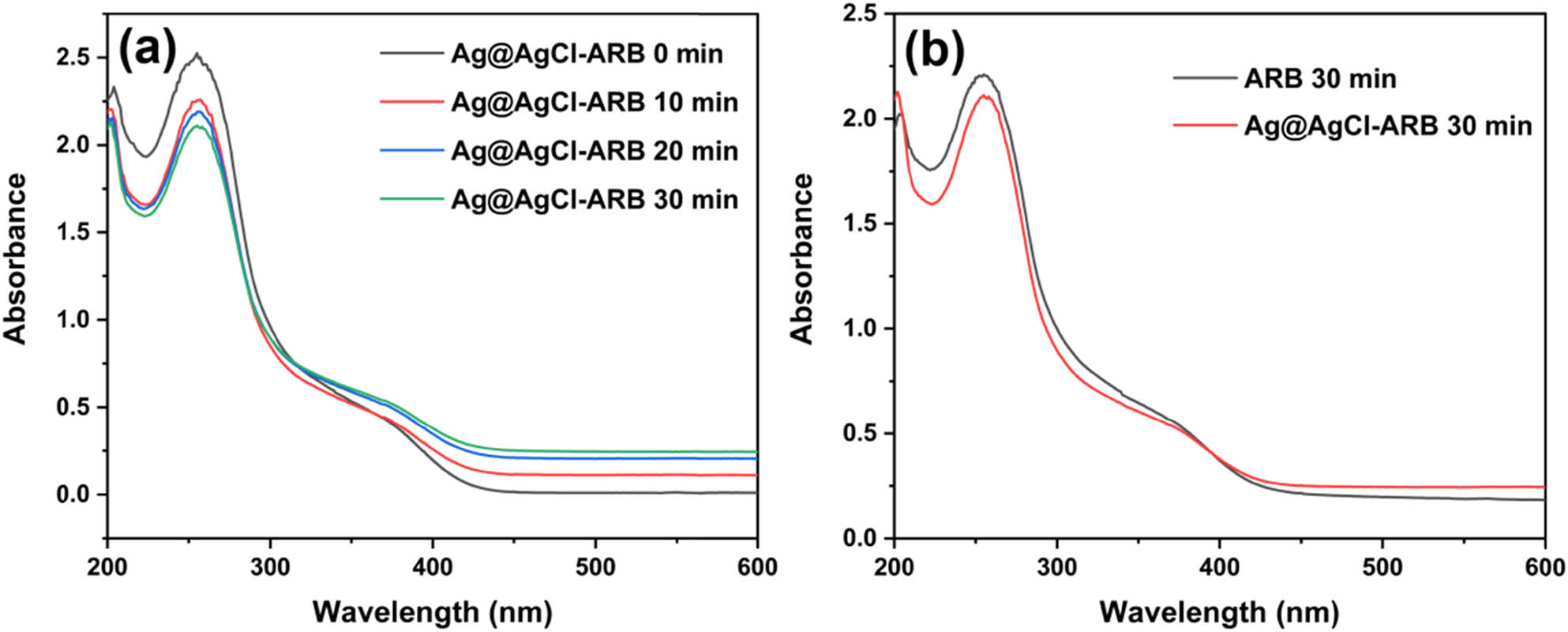

The formation of ·

The NBT absorbance curves of Ag@AgCl–ARB with increasing time (a) and the comparison of ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB (b).

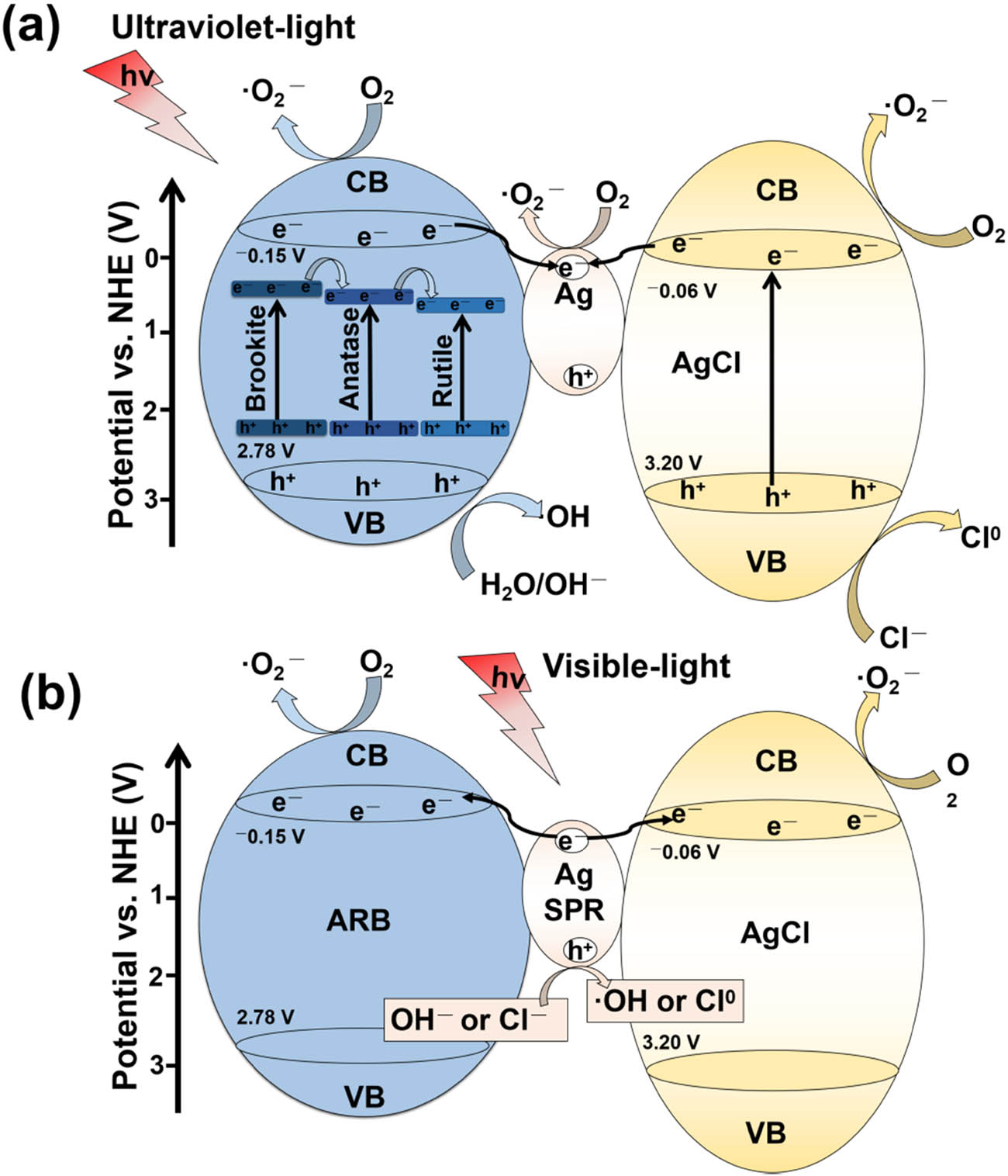

The band potential can be estimated through the electronegativity equation of E

CB = X – E

0 – E

g/2 and EVB = E

g + E

CB, where E

VB is the valence band potential, E

CB is the conduction band potential, E

0 is the free electron energy on the hydrogen scale (E

0 = 4.5 eV), E

g is the bandgap energy of the photocatalytic material, and X is the absolute electronegativity of the semiconductor [49,50,51]. Based on the DRS result (the band gap of ARB = 2.93 eV), the E

CB and E

VB of ARB are –0.15 and 2.78 eV, respectively. ARB consists of anatase, rutile, and brookite, and brookite shows the highest conduction band, followed by anatase and rutile [20,44,52,53]. On the other hand, the E

CB and E

VB of AgCl are determined to be −0.06 and 3.2 eV [54]. Based on the above content, a possible mechanism of the photogenerated charges separation and transfer for Ag@AgCl–ARB is proposed, as shown in Figure 12. In UV light region, photogenerated charges are generated, as TiO2 is three phase mixed crystal structure, which can accelerate the migration of carriers [52,53]. Moreover, the conduction bands of TiO2 and AgCl are higher than the Fermi level of metallic Ag, and the photogenerated electrons generated in TiO2 and AgCl will transfer to Ag particles, further inhibiting the recombination [54,55,56,57]. In visible light region, due to the SPR effect of Ag, the hot-electrons generated in Ag particles can be transferred to the conduction band of TiO2 and AgCl, which are captured by O2 to generate ·

Schematic illustration of the charge separation and transfer in the Ag@AgCl–ARB photocatalysts under ultraviolet light (a) and visible light irradiation (b).

4 Conclusion

ARB and Ag@AgCl–ARB were prepared by one step hydrothermal method. ARB shows a three-phase mixed crystal structure composed of anatase, rutile, and brookite. Ag@AgCl modification does not change the crystal structure of ARB. The formation of Ag@AgCl–ARB heterojunctions is advantageous to the separation of photogenerated charges and the absorption of visible light, which can be explained by the fact that Ag@AgCl–ARB exhibits the highest photocatalytic activity.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the Higher Education Talent Quality and Teaching Reform Project of Sichuan Province (JG2021-1104), the Talent Training Quality and Teaching Reform Project of Chengdu University (cdjgb2022033), and the Key Research and Development Projects of Liangshan Prefecture Science and Technology Bureau of Sichuan Province (21ZDYF0202).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Mahmoodi NM, Taghizadeh M, Taghizadeh A. Activated carbon/metal-organic framework composite as a bio-based novel green adsorbent: preparation and mathematical pollutant removal modeling. J Mol Liq. 2019;277:310–22.10.1016/j.molliq.2018.12.050Search in Google Scholar

[2] Mahmoodi NM. Dendrimer functionalized nanoarchitecture: synthesis and binary system dye removal. J Taiwan Inst Chem E. 2014;45(4):2008–20.10.1016/j.jtice.2013.12.010Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mahmoodi NM. Manganese ferrite nanoparticle: synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic dye degradation ability. Desalin Water Treat. 2015;53(1):84–90.10.1080/19443994.2013.834519Search in Google Scholar

[4] Yu XJ, Zhang J, Zhang J, Niu JF, Zhao J, Wei YC, et al. Photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using Zn-doped Cu2O particles: analysis of degradation pathways and intermediates. Chem Eng J. 2019;374:316–27.10.1016/j.cej.2019.05.177Search in Google Scholar

[5] Li FH, Kang YP, Chen M, Liu GG, Lv WY, Yao K, et al. Photocatalytic degradation and removal mechanism of ibuprofen via monoclinic BiVO4 under simulated solar light. Chemosphere. 2016;150:139–44.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.045Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Mahmoodi NM, Limaee NY, Arami M, Borhany S, Mohammad-Taheri M. Nanophotocatalysis using nanoparticles of titania mineralization and finite element modelling of solophenyl dye decolorization. J Photoch Photobio A. 2007;189:1–6.10.1016/j.jphotochem.2006.12.025Search in Google Scholar

[7] Li M, Zhang JY, Zhang Y. First-principles calculation of compensated (2N, W) codoping impacts on band gap engineering in anatase TiO2. Chem Phys Lett. 2012;527:63–6.10.1016/j.cplett.2012.01.009Search in Google Scholar

[8] Chen Y, Xiang ZY, Wang DS, Kang J, Qi HS. Effective photocatalytic degradation and physical adsorption of methylene blue using cellulose/GO/TiO2 hydrogels. RSC Adv. 2020;10:23936–43.10.1039/D0RA04509HSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Lin XX, Rong F, Fu DG, Yuan CW. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of fluorine doped TiO2 loaded with Ag for degradation of organic pollutants. Powder Technol. 2012;219:173–8.10.1016/j.powtec.2011.12.037Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bousiakou LG, Dobson PJ, Jurkin T, Marić I, Aldossary O, Ivanda M. Optical, structural and semiconducting properties of Mn doped TiO2 nanoparticles for cosmetic applications. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2022;34:101818.10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101818Search in Google Scholar

[11] Asahi R, Taga Y, Mannstadt W, Freeman AJ. Electronic and optical properties of anatase TiO2. Phys Rev B. 2000;61(11):7459–65.10.1103/PhysRevB.61.7459Search in Google Scholar

[12] Serga V, Burve R, Krumina A, Romanova M, Kotomin EA, Popov AI. Extraction-pyrolytic method for TiO2 polymorphs production. Crystals. 2021;11:431.10.3390/cryst11040431Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ziarati A, Badiei A, Luque R. Black hollow TiO2 nanocubes: Advanced nanoarchitectures for efficient visible light photocatalytic applications. Appl Catal B-Environ. 2018;238:177–83.10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.07.020Search in Google Scholar

[14] Hou CT, Liu HY, Bakhtari MF. Preparation of Ag SPR-promoted TiO2-{001}/HTiOF3 photocatalyst with oxygen vacancies for highly efficient degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride. Mat Sci Semicon Proc. 2021;136:106142.10.1016/j.mssp.2021.106142Search in Google Scholar

[15] Hu HH, Qian DG, Lin P, Ding ZX, Cui C. Oxygen vacancies mediated in-situ growth of noble-metal (Ag, Au, Pt) nanoparticles on 3D TiO2 hierarchical spheres for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from water splitting. ScienceDirect. 2020;45:629–39.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.10.231Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhu XD, Liu H, Wang J, Dai HL, Bai Y, Feng W, et al. Investigation of photocatalytic activity of Ag-rutile heterojunctions. Micro Nano Lett. 2020;15(15):1130–3.10.1049/mnl.2020.0253Search in Google Scholar

[17] Xu XY, Wu CB, Guo AY, Qin BP, Sun YF, Zhao CM, et al. Visible-light photocatalysis of organic contaminants and disinfection using biomimetic-synthesized TiO2-Ag-AgCl composite. Appl Surf Sci. 2022;588:152886.10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.152886Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wang YF, Zhang M, Li J, Yang HC, Gao J, He G, et al. Construction of Ag@AgCl decorated TiO2 nanorod array film with optimized photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic performance. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;476:84–93.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.01.086Search in Google Scholar

[19] Azizi-Toupkanloo H, Karimi-Nazarabad M, Amini GR, Darroudi A. Immobilization of AgCl@TiO2 on the woven wire mesh: sunlight-responsive environmental photocatalyst with high durability. Sol Energy. 2020;196:653–62.10.1016/j.solener.2019.12.046Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhu XD, Zhou Q, Xia YW, Wang J, Chen HJ, Xu Q, et al. Preparation and characterization of Cu-doped TiO2 nanomaterials with anatase/rutile/brookite triphasic structure and their photocatalytic activity. J Mater Sci-Mater El. 2021;32(16):21511–24.10.1007/s10854-021-06660-5Search in Google Scholar

[21] Preethi LK, Mathews T, Nand M, Jha SN, Gopinath CS, Dash S. Band alignment and charge transfer pathway in three phase anatase-rutile-brookite TiO2 nanotubes: an efficient photocatalyst for water splitting. Appl Catal B-Environ. 2017;218:9–19.10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.033Search in Google Scholar

[22] Mutuma BK, Shao GN, Kim WD, Kim HT. Sol-gel synthesis of mesoporous anatase-brookite and anatase-brookite-rutile TiO2 nanoparticles and their photocatalytic properties. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2015;442:1–7.10.1016/j.jcis.2014.11.060Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Zhou GB, Jiang L, Dong YL, Li R, He DP. Engineering the exposed facets and open-coordinated sites of brookite TiO2 to boost the loaded Ru nanoparticle efficiency in benzene selective hydrogenation. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;486:187–97.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.029Search in Google Scholar

[24] Ding MZ, Miao XL, Cao LJ, Zhang CM, Ping YX. Core-shell nanostructured SiO2@a-TiO2@Ag composite with high capacity and safety for Li-ion battery anode. Mater Lett. 2022;308:131276.10.1016/j.matlet.2021.131276Search in Google Scholar

[25] Padmini M, Balaganapathi T, Thilakan P. Mesoporous rutile TiO2: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic performance studies. Mater Res Bull. 2021;144:111480.10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111480Search in Google Scholar

[26] Granbohm H, Kulmala K, Iyer A, Ge YL, Hannula S-P. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of quaternary GO/TiO2/Ag/AgCl nanocomposites. Water Air Soil Poll. 2017;228(4):1–16.10.1007/s11270-017-3313-9Search in Google Scholar

[27] Sun Y, Gao Y, Zhao BS, Xu S, Luo CH, Zhao Q. One-step hydrothermal preparation and characterization of ZnO-TiO2 nanocomposites for photocatalytic activity. Mater Res Exp. 2020;7:085010.10.1088/2053-1591/abaea4Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zhang Y, Wang T, Zhou M, Wang Y, Zhang ZM. Hydrothermal preparation of Ag-TiO2 nanostructures with exposed {001}/{101} facets for enhancing visible light photocatalytic activity. Ceram Int. 2017;43:3118–26.10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.127Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lu LY, Wang GH, Xiong ZW, Hu ZF, Liao YW, Wang J, et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light by the synergistic effects of plasmonics and Ti3+ -doping at the Ag/TiO2-x heterojunction. Ceram Int. 2020;46:10667–77.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.01.073Search in Google Scholar

[30] Yin HY, Wang XL, Wang L, Nie QL, Zhang Y, Yuan QL, et al. Ag/AgCl modified self-doped TiO2 hollow sphere with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J Alloy Compd. 2016;657:44–52.10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.10.055Search in Google Scholar

[31] Liu SM, Zhu DL, Zhu JL, Yang Q, Wu HJ. Preparation of Ag@AgCl-doped TiO2/sepiolite and its photocatalytic mechanism under visible light. J Env Sci. 2017;60:43–52.10.1016/j.jes.2016.12.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Zhu LD, Opulencia MJC, Bokov DO, Krasnyuk II, Su CH, Nguyen HC, et al. Synthesis of Ag-coated on a wrinkled SiO2@TiO2 architectural photocatalyst: new method of wrinkled shell for use of semiconductors in the visible light range and penicillin antibiotic degradation. Alex Eng J. 2022;61:9315–34.10.1016/j.aej.2022.03.009Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ali T, Ahmed A, Alam U, Uddin I, Tripathi P, Muneer M. Enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial activities of Ag-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under visible light. Mater Chem Phys. 2018;212:325–35.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.03.052Search in Google Scholar

[34] Zheng S, Li XJ, Zhang JY, Wang JF, Zhao CR, Hu X, et al. One-step preparation of MoOx/ZnS/ZnO composite and its excellent performance in piezocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B under ultrasonic vibration. J Env Sci. 2023;125:1–13.10.1016/j.jes.2021.10.028Search in Google Scholar

[35] Feng Z, Zeng L, Zhang QL, Ge SF, Zhao XY, Lin HJ, et al. In situ preparation of g-C3N4/Bi4O5I2 complex and its elevated photoactivity in methyl orange degradation under visible light. J Env Sci. 2020;87:149–62.10.1016/j.jes.2019.05.032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Chen PF, Chen L, Ge SF, Zhang WQ, Wu MF, Xing PX, et al. Microwave heating preparation of phosphorus doped g-C3N4 and its enhanced performance for photocatalytic H2 evolution in the help of Ag3PO4 nanoparticles. Int J Hydrog Energ. 2020;45:14354–67.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.03.169Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zeng L, Zhe F, Wang Y, Zhang QL, Zhao XY, Hu X, et al. Preparation of interstitial carbon doped BiOI for enhanced performance in photocatalytic nitrogen fixation and methyl orange degradation. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2019;539:563–74.10.1016/j.jcis.2018.12.101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Haryński L, Olejnik A, Grochowska K, Siuzdak K. A facile method for Tauc exponent and corresponding electronic transitions determination in semiconductors directly from UV-Vis spectroscopy data. Opt Mater. 2022;127:112205.10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112205Search in Google Scholar

[39] Soumya S, Joe IH. A combined experimental and quantum chemical study on molecular structure, spectroscopic properties and biological activity of anti-inflammatory glucocorticosteroid drug, dexamethasone. J Mol Struct. 2021;1245:130999.10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130999Search in Google Scholar

[40] Shkir M, Khan ZR, Khan A, Chandekar KV, Sayed MA, AlFaify S. A comprehensive study on structure, opto-nonlinear and photoluminescence properties of Co3O4 nanostructured thin films: An effect of Gd doping concentrations. Ceram Int. 2022;48:14550–59.10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.01.348Search in Google Scholar

[41] Xu WC, Lai SF, Pillai SC, Chu W, Hu Y, Jiang XD, et al. Visible light photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline with porous Ag/graphite carbon nitride plasmonic composite: degradation pathways and mechanism. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2020;574:110–21.10.1016/j.jcis.2020.04.038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Oveisi M, Mahmoodi NM, Asli MA. Facile and green synthesis of metal-organic framework/inorganic nanofiber using electrospinning for recyclable visible-light photocatalysis. J Clean Prod. 2019;222:669–84.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.066Search in Google Scholar

[43] Prakash K, Kumar PS, Pandiaraj S, Saravanakumar K, Karuthapandian S. Controllable synthesis of SnO2 photocatalyst with superior photocatalytic activity for the degradation of methylene blue dye solution. J Exp Nanosci. 2016;11(14):1138–55.10.1080/17458080.2016.1188222Search in Google Scholar

[44] Tang M, Xia YW, Yang DX, Lu SJ, Zhu XD, Tang RY, et al. Ag decoration and SnO2 coupling modified anatase/rutile mixed crystal TiO2 composite photocatalyst for enhancement of photocatalytic degradation towards tetracycline hydrochloride. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:873.10.3390/nano12050873Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Wang Y, Qiao MZ, Lv J, Xu GQ, Zheng ZX, Zhang XY, et al. g-C3N4/g-C3N4 isotype heterojunction as an efficient platform for direct photodegradation of antibiotic. Fuller Nanotub Car N. 2018;26(4):210–7.10.1080/1536383X.2018.1427737Search in Google Scholar

[46] Zhu XD, Wang J, Yang DX, Liu JW, He LL, Tang M, et al. Fabrication, characterization and high photocatalytic activity of Ag-ZnO heterojunctions under UV-visible light. RSC Adv. 2021;11:27257–66.10.1039/D1RA05060ESearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Li J, Wan YJ, Li YJ, Yao G, Lai B. Surface Fe(III)/Fe(II) cycle promoted the degradation of atrazine by peroxymonosulfate activation in the presence of hydroxylamine. Appl Catal B-Environ. 2019;256:117782.10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.117782Search in Google Scholar

[48] Qin JX, Wang J, Yang JJ, Hu Y, Fu ML, Ye DQ. Metal organic framework derivative-TiO2 composite as efficient and durable photocatalyst for the degradation of toluene. Appl Catal B-Environ. 2020;267:118667.10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.118667Search in Google Scholar

[49] Ren FZ, Zhang JH, Wang YX. Enhanced photocatalytic activities of Bi2WO6 by introducing Zn to replace Bi lattice sites: A first-principles study. RSC Adv. 2015;5:29058–65.10.1039/C5RA02735GSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Wen XJ, Niu CG, Ruan M, Zhang L, Zeng GM. AgI nanoparticles-decorated CeO2 microsheets photocatalyst for the degradation of organic dye and tetracycline under visible-light irradiation. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2017;497:368–77.10.1016/j.jcis.2017.03.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Alhaddad M, Ismail AA, Alghamdi YG, Al-Khathami ND, Mohamed RM. Co3O4 nanoparticles accommodated mesoporous TiO2 framework as an excellent photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic properties. Opt Mater. 2022;131:112643.10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112643Search in Google Scholar

[52] Wang HL, Gao XY, Duan GR, Yang XJ, Liu XH. Facile preparation of anatase-brookite-rutile mixed-phase N-doped TiO2 with high visible-light photocatalytic activity. J Env Chem Eng. 2015;3:603–8.10.1016/j.jece.2015.02.006Search in Google Scholar

[53] Benjwal P, De B, Kar KK. 1-D and 2-D morphology of metal cation co-doped (Zn, Mn) TiO2 and investigation of their photocatalytic activity. Appl Surf Sci. 2018;427:262–72.10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.08.226Search in Google Scholar

[54] Yang QL, Hu MY, Guo J, Ge ZH, Feng J. Synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Ag/AgCl/TiO2 nanocomposites prepared by ion exchange method. J Materiomics. 2018;4:402–11.10.1016/j.jmat.2018.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[55] Xue XL, Gong XW, Chen XY, Chen BY. A facile synthesis of Ag/Ag2O@TiO2 for toluene degradation under UV-visible light: Effect of Ag formation by partial reduction of Ag2O on photocatalyst stability. J Phys Chem Solids. 2021;150:109799.10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109799Search in Google Scholar

[56] Chen L, Zhang WQ, Wang JF, Li XJ, Li Y, Hu X, et al. High piezo/photocatalytic efficiency of Ag/Bi5O7I nanocomposite using mechanical and solar energy for N2 fixation and methyl orange degradation. Green Energy Env. 2021. 10.1016/j.gee.2021.04.009.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Li ZY, Zhang QL, Wang LK, Yang JY, Wu Y, He YM. Novel application of Ag/PbBiO2I nanocomposite in piezocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B via harvesting ultrasonic vibration energy. Ultrason Sonochem. 2021;78:105729.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105729Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Zhang GH, Wang JC, Zhang HR, Zhang TY, Jiang S, Li B, et al. Facile synthesize hierarchical tubular micro-nano structured AgCl/Ag/TiO2 hybrid with favorable visible light photocatalytic performance. J Alloy Compd. 2021;855(2):157512.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157512Search in Google Scholar

[59] Mahmoodi NM, Taghizadeh A, Taghizadeh M, Abdi J. In situ deposition of Ag/AgCl on the surface of magnetic metal-organic framework nanocomposite and its application for the visible-light photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine dye. J Hazard Mater. 2019;378:120741.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.06.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Xiaodong Zhu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption