Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

-

Ahmed A. H. Abdellatif

, Asmaa T. Ali

Abstract

Sorafenib (SFB) is an anticancer drug with sparingly water solubility and reduced bioavailability. Nanoformulation of SFB can increase its dissolution rate and solubility. The current study aimed to formulate SFB in nanoparticles to improve their solubility. The sorafenib nanoparticles (SFB-PNs) were synthesized using the solvent evaporation method, then evaluated for their particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), zeta-potential, morphological structure, and entrapment efficiency (EE%). Further, the anticancer efficacy in A549 and Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) cancer cell lines was evaluated. The SFB-NPs were uniform in size, which have 389.7 ± 16.49 nm, PDI of 0.703 ± 0.12, and zeta-potential of −13.5 ± 12.1 mV, whereas transmission electron microscopy showed a well-identified spherical particle. The EE% was found to be 73.7 ± 0.8%. SFB-NPs inhibited the cell growth by 50% after 48 h incubation, with IC50 of 2.26 and 1.28 µg/mL in A549 and MCF-7, respectively. Additionally, SFB-NPs showed a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in p21, and stathmin-1 gene expression levels in both cell lines. Moreover, SFB-NPs showed a significant increase in DNA damage of 25.50 and 26.75% in A549 and MCF-7, respectively. The results indicate that SFB-NPs are a potential candidate with an effective anticancer agent compared with free drugs.

1 Introduction

Sorafenib (SFB) is a drug taken orally and is approved to treat advanced renal cell carcinoma, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, and advanced thyroid cancer [1]. SFB is a small molecule that acts as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibiting v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF), rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase) (C-RAF), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, proto oncogene predictive biomarker (RET), receptor tyrosine kinase (c-KIT), and oncogene responsible for Feline McDonough Sarcoma (FMS)-like tyrosine kinase-3 [2]. Antitumor mechanisms may include preventing tumor growth and progression, preventing metastasis and angiogenesis, and inhibiting mechanisms that protect tumors from apoptosis [3]. SFB’s clinical application is based on its angiogenesis inhibition activity, such as other antiangiogenetic agents. Because targeting angiogenesis is effective in the treatment of advanced breast cancer, the role of SFB was studied for this indication as well [2,4]. The current study sought to assess the role of SFB in the treatment of breast cancer, particularly its efficacy and safety profile, using evidence from clinical trials. A recent study of the SFB effect on Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) breast cancer cell line investigated its effect on proliferation, migration, and invasion. It proved that SFB is active against breast cancer and could improve the survival of patients with this cancer type by inhibiting their invasive and metastatic characteristics [5].

SFB is a drug that is poorly soluble in an aqueous solution. The greatest solubility in ordinary water is between ∼10 and 20 µg/mL, challenging its bioavailability [6]. Formulating poorly soluble medications is one of the most difficult challenges in the pharmaceutical industry. The use of nanotechnology in medicine formulation improves solubility and efficacy of hydrophobic pharmaceuticals [7]. Kwok and Chan [8] reported that many newly discovered therapeutic compounds have low aqueous solubility, leading to reduced bioavailability in humans. Making them into nanoparticles increases their surface area and thus their dissolving rate and solubility.

Nanoparticles are one of several nanosized carriers developed for drug delivery applications [9]. The solvent evaporation method is used for producing nanoparticles. Water-miscible solvents such as acetone or methanol and water-immiscible organic solvents such as chloroform or dichloromethane were used as an oil phase in this method. At the same time, polymer and emulsifying agents are dispersed rapidly in the aqueous phase. This technique has several advantages, including that it is quick and simple to implement, as the entire procedure can be completed in a single step [10]. Developing a nanocarrier that enables targeted medication delivery and regulates the release of effective agents might reduce the major drawbacks of using anticancer drugs. Polymeric nanoparticulate drug delivery methods have been found to be effective in sustaining drug release and targeting [11]. Doxorubicin (DOX) loaded polyethylene glycol (PEG)–poly D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLDA)–Au nanoparticles with a cytostatic drug content of 3.9% were developed to enable a combination treatment based on chemotherapy and heat therapy by near-infrared radiation to be used in the treatment of cancer [12].

Studying the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs in different types of cancer is an essential goal. This can be achieved by determining the specific DNA damage mechanism utilized by cancer cells, which will likely be coupled with an overly vigorous p53-mediated cell cycle control pathway (such as the p53-activated poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase or PARP) and activation of the antiapoptotic molecule p21 [13]. p21 protein in the cytoplasm suppresses apoptosis and functions as an oncogene [14]. However, DNA damage decreases p21 expression, and cell death proceeds by apoptosis [15]. Stathmin-1 (STMN1) is a microtubule destabilizer protein that controls microtubule dynamics, cell cycle progression, proliferation, and motility, and is associated with overall survival [16,17]. STMN1 is a critical node in the convergence of several oncogenic signaling pathways, and its involvement in the genesis and progression of cancer has been debated in recent years [18]. Aronova et al. [19] recently revealed that STMN1 is abundantly expressed in different types of cancer cells and that inhibiting STMN1 decreases cells clonogenicity, tolerance to serum deprivation, and migration. In contrast, this study sheds light on the role of p21 and STMN1 in the tumorigenesis of the lung and breast cancer cells, respectively. The current study attempts to enhance the efficacy of SFB through nanoparticle formulation. SFB was formulated into nanoparticles via integration within the PEG-4000 polymer, aided by glycerol, which acts as a wetting agent, cosolvent to enhance the solubility of SFB. The produced nanoparticles were characterized for their size, zeta-potential, and efficiency of release. Moreover, in vitro anticancer biological activity studies were compared to free SFB. Furthermore, SFB-NPs were clinically validated to prove the possible therapeutic for lung and breast anticancer activity.

2 Material and method

2.1 Material

SFB was purchased from Biosynth Carbosynth (Compton, Berkshire, United Kingdom). Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), insulin, and penicillin–streptomycin, methanol, glycerol, polyethylene glycol (PEG-4000), and RNAse-free DNAse used for RNA extraction and complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis from lung and breast cell lines were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). The adenocarcinomas human alveolar basal epithelial cells (EML4-ALK Fusion-A549 Isogenic Cell Line Human) [M-5655] A549 and MCF-7 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The RNeasy Mini Kit and DNase I (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The gene expression was measured using the StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System from Applied Biosystems (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit and agarose were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM reconstituted vials of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from TaKaRa, Biotech, Co, Ltd (Orchard Parway, San Jose, CA, USA). All other chemicals and analytical reagents were of analytical grades and used as received.

2.2 Preparation of SEB polymeric nanoparticle

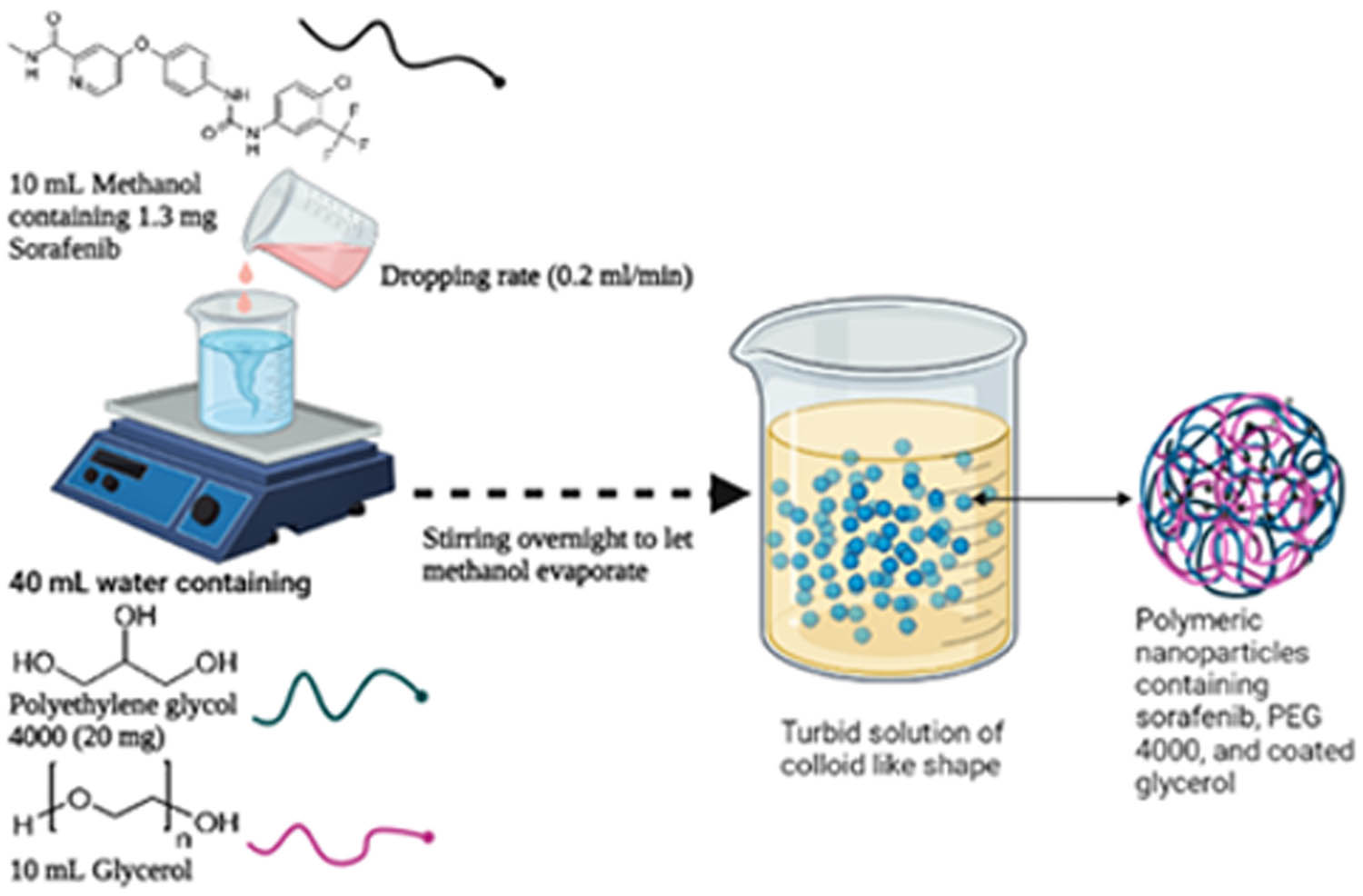

The SFB nanoparticles were prepared through the solvent evaporation method at a concentration of 50 µM. Briefly, 1.3 mg of SEB was dissolved in 10 mL methanol at room temperature (25°C; solution I). The aqueous phase (40 mL) contained the water-soluble polymer PEG-4000 in a drug: polymer ratio of 1:1, and 10 mL glycerol as a stabilizer and viscosity modifier to stabilize the prepared SFB-NPs (solution II). The solution I was dropped into the aqueous phase solution II using a syringe positioned with the needle directly and subsequently stirred at 600 rpm on a magnetic stirrer to allow the methanol to evaporate [20]. The prepared formula was then purified via centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min to separate the formulated polymeric nanoparticles from any nonreacting molecules present. The prepared formula was stored at 4°C for the next work.

2.3 Evaluation of particle size and zeta potential

SEB-NP size distribution was measured using the laser light scattering technique Malvern Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments GmbH, Herrenberg, Germany). A total of 1 mL of the diluted nanoparticle suspension was vortex mixed for 5 min then was measured for the size, the zeta-potential, and the PDI [21].

2.4 Morphological study by transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM (JEOL 100CX; JEOL Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) with an accelerating voltage of 80 kV was used to characterize the morphology of the SFB-NPs. SFB-NPs formula was diluted from 1 to 0.01% w/w then treated in an ultrasonic bath (Model 3510, Branson, MS) to decrease the particle aggregation on the copper grid. One drop of the SFB-NPs was spread onto a carbon-coated copper grid, which was then dried for TEM analysis [22,23]. The distribution of SFB-NPs dimensions was evaluated from TEM images using Image J 1.45k software (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ; USA, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.5 FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR was utilized to determine the compatibility of all components; thus, we intended to discover any drug–polymer interaction by collecting the data between 400 and 4,000 cm−1. SFB, PEG, SFB and PEG physical mix, and SFB-NPs were subjected to FTIR (FTIR-Spectrometer, Tensor 27, Bruker, USA) [24].

2.6 Entrapment efficiency (EE%)

The formulated SFB-NPs were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. Then 5 mL of supernatant was distributed with 5 mL methanol. The amount of unbound drug present in the supernatant was measured to determine the amount of entrapped SFB. The absorbance of the diluted supernatant solution was measured at λ max 264 nm using a single beam UV spectrophotometer (Genesis 10 UV, Thermo-electron Corporation, USA) against methanol as a blank. Drug content was calculated by subtracting the amount of free SFB from the total amount of SFB used and divided on the total amount of SFB used in the synthesis (the starting drug loaded) according to equation (1). The experiment was performed in triplicate for each batch and the average was calculated [25].

2.7 Physical stability

A 3-month storage period at 25.0 ± 0.5 and 4.0 ± 0.5°C was used to evaluate the physical stability of the prepared SFB-NPs. To determine the stability of SFB-NPs were loaded by SFB, the physical parameters such as color, shape, particle size, and zeta-potential were measured before and after storage to determine their stability [26].

2.8 Anticancer evaluation

2.8.1 Cell culture protocol

ATCC breast cancer (MCF-7) and adenocarcinomas human alveolar basal epithelial cells (A549 cells) were collected and grown according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (ATCC, VA, USA). For this study, MCF-7 cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, in addition to 10% FBS. Control cells were MCF-7 cells that were not treated with SFBNPs served as negative control cells [27,28].

The culture media was transferred to a centrifuge tube and a quick rinse with 0.25% (w/v). Trypsin 0.53 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution was administered to the cell layer to eliminate any remnants of serum containing trypsin inhibitor. Approximately 2.0–3.0 mL of trypsin EDTA solution was added to the flask, and cells were examined under an inverted microscope until the cell layer dissolved (usually within 5–15 min). About 6–8 mL of full growth media was added, and cells were gently aspirated using a pipette. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were treated with successive concentrations of the chemical to be evaluated. After 48 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were inspected under an inverted microscope, and the MTT assay was performed [28].

2.8.2 Cytotoxicity assay protocol

MTT (3(4,5dimethylthiazol-2yl)2,5diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) technique was used to assess the in vitro inhibitory effects of the SFB and SFB-NPs on A549 and MCF-7 cells growth. We investigated the antiproliferative and inhibitory cytotoxic effects of SFB-NPs versus free SFB, DOX, and tamoxifen (Tam) on lung (A549) and breast (MCF-7) carcinoma cell lines. Mosmann’s MTT technique using specifically, a medium containing 10 × 103 cells (A549 and MCF-7 cells) in a new complete growth media were seeded within each well of a 96-well microplate, followed by the addition of the chemical solution in triplicate wells. For 72 h, the plate was incubated at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 in a water-coated carbon dioxide incubator (TC2323; Sheldon, Cornelius, OR) [29]. The media was aspirated and replaced with a new medium (without serum). Cells were incubated alone (as a negative control) or with increasing sample concentrations to get final concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, 1.56, and 0.78 µg/mL. After 48 h, the medium was aspirated and 200 mL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in deionized water was added to each well. The wells were then incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. Then, 200 mL of 10% SDS in deionized water was added to each well to halt the reaction and solubilize any remaining MTT formazan, followed by overnight incubation at 37°C. DOX (100 µg/mL), a well-characterized natural cytotoxic drug, was used as a positive control as it demonstrated 100% mortality under identical circumstances. Additionally, 100 mL of 0.02 N HCl/50% N,N-dimethylformamide and 20% SDS were used to solubilize any remaining MTT formazan. The optical density of each well was determined at 575 nm (OD575) using a microplate multiwell reader (model 3350; Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA).

2.8.3 Gene expression analysis/RNA isolation

According to the kit instructions, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit from each kind of treated and controlled cancer cell line. The samples were treated with RNAse-free DNAse to remove any DNA contamination. Although the RNA’s integrity was evaluated using formaldehyde-containing agarose gel electrophoresis, its amount and purity were measured using photospectrometric measurements at 260 nm. Then, aliquots of isolated RNA were kept at −80°C [30].

2.8.4 Reverse transcription (RT) reaction

The extracted messenger RNA from the treated and control cancer cell lines was synthesized using the RevertAid TM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. The kit’s handbook instructions for reaction setup and incubation were followed for a reaction including oligo-dT as a primer and 5 µg of RNA in a 20 µL total volume. Following that, the cDNA samples were kept at a temperature of −80°C [31,32].

2.8.5 Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) method

The number of cDNA copies in A549 and MCF-7 cell lines was determined using the Applied Biosystems StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System. PCR reactions were carried out in 25 µL reaction mixtures comprising 12.5 µL 1× SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM, 0.5 µL 0.2 µM sense primer, 0.5 µL 0.2 µM antisense primer, 6.5 µL distilled water, and 5 µL cDNA template. Three phases were assigned to the response program. The initial step was 3 min at 95.0°C. The second phase consisted of 40 cycles, each of which was broken into three steps: (a) 15 s at 95.0°C, (b) 30 s at 55.0°C, and (c) 30 s at 72.0°C. The third phase consisted of 71 cycles that began at 60.0°C and rose by approximately 0.5°C every 10 s until reaching 95.0°C. After each semi-quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (sqRT-PCR), a melting curve analysis at 95.0°C was conducted to determine the quality of the primers used. Each experiment included a control with distilled water. Table 1 contains the sequences of particular primers for lung p21 (CDKN1A genes) and breast (STMN1 and tubulin genes) cancer-related genes. After each qPCR, a melting curve analysis at 95.0°C was done to determine the quality of the primers used. The 2−ΔΔCT technique was used to determine the target’s relative quantification to an earlier study [33].

Primers sequence used for RT-qPCR of lung and breast cancer cell lines

| Gene | Forward | GenBank accession no |

|---|---|---|

| p21* | F: CCTGTGTGTGTTTGCCATCA | J00277.1 |

| R: TGAGAGGTGGAAAGCGAGAG | ||

| Stathmin | F: GTCTTCCAGAGTCACACCCA | NM_001276310.2 |

| R: TGAGTCCCACAAAAGCCAGA | ||

| β-actin | F: CATGGAATCCTGTGGCATCC | HQ154074.1 |

| R: CACACAGAGTACTTGCGCTC |

*p21: protein 21; CDKN1A: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A.

2.8.6 DNA damage using the comet assay

The DNA damage to A549 and MCF-7 cancer cell lines was evaluated using the comet assay [34]. Following trypsin digestion to get a single cell suspension, about 1.5 × 104 cells were embedded in 0.75% low-gelling-temperature agarose and quickly pipetted onto a precoated microscope slide. After 4 h at 50°C in 0.5% SDS, 30 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, samples were lysed. After overnight in Tris/borate/EDTA buffer, pH 8.0, materials were electrophoresed for 25 min at 0.6 V/cm and stained with propidium iodide. The slides were examined using a fluorescent microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device- Digital camera systems (CCD) camera, and 150 unique comet pictures from each sample were evaluated for the tail moment, DNA content, and tail percentage DNA. Around 100 cells were analyzed in each sample to identify the percentage of DNA damage that resembled comets. The nonoverlapping cells were randomly chosen and visually scored on an arbitrary scale of 0–3 (class 0 = no detectable DNA damage and no tail; class 1 = tail with a length less than the diameter of the nucleus; class 2 = tail with a length between 1 × and 2 × the diameter of the nucleus; and class 3 = tail longer than 2 × the diameter of the nucleus) based on perceived comet tail length [35].

2.8.7 DNA fragmentation assay

The DNA fragmentation test in A549 and MCF-7 cell lines was proceeded following Yawata’s et al. [36] with minor changes. After 24 h of exposure to the investigated drugs on various Petri dishes (60 mm × 15 mm, Greiner), the cells were trypsinized, suspended, homogenized, and centrifuged in 1 mL of medium (10 min at 800 rpm). Approximately 1 × 106 cells were grown and subjected to various treatments with the tested chemicals. Trypsinization was used to collect all cells (including floating cells), then washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline. For 30 min on ice, cells were lysed with 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100. Vortexing and centrifugation at 10,000g for 20 min were used to clarify lysates. Fragmented DNA was extracted from the supernatant using an equal volume of neutral phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and electrophoretically separated on 2% agarose gels containing 0.1 μg/mL ethidium bromide.

2.9 Statistical evaluations of in vitro experiments

All experiments were conducted three times for validity and precision. This example of data presentation presents the information as the mean (average) and standard deviation (a common measure of dispersion) of three separate trials. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). To compare data, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. P-value less than 0.05 was determined to be statistically significant [37,38]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, or ***p < 0.001 denote statistically significant differences.

3 Results and discussion

The food and drug administration (FDA) has endorsed SFB as a first-line therapy option based on its survival benefits in clinical trials for many types of cancer [39]. However, the drug’s poor pharmacokinetic qualities severely restricted its future clinical application in cancer therapy. A nanoscale SFB delivery system has been developed using nanotechnology [40]. The solvent evaporation method was used to prepare the SFB-NPs, and it was purified via centrifugation to separate the formulated SFB-NPs from any nonreacting molecules found. Although this technique may cause loss of nanoparticles less than 100 nm, it was considered better than filter paper as filter paper causes losing a lot of particles by sticking to its surface [41].

The SFB-NPs were evaluated for their pharmaceutical characteristics. They were found to have a nanosize spherical particle with an accepted EE% and cytotoxic activity on different cell line cancer cells. SFB-NPs were prepared using the solvent evaporation method suited for most of the poorly soluble drugs [41]. The glycerol is used as a surfactant, to increase the viscosity, and to stabilize the prepared SFB-NPs. Rapid solvent evaporation produced SFB-NPs almost instantly. Once the methanol evaporates, the SFB hides inside the polymer, forming the SFB-NPs (Figure 1). The rates of the addition of the methanol as a nonaqueous phase into the aqueous phase affect the particle size. It was observed that a decrease in both particle size and drug entrapment occurs as the rate of mixing of the two-phase increases [42].

Schematic illustrating the preparation of SFB-NPs formation.

PEG is used in drug delivery and nanotechnology due to its reported biocompatibility. PEG is considered to help drug delivery and, therefore, extend circulation lifetimes [43]. PEG enhances the circulatory half-life with no protein binding [44,45]. Moreover, PEG-4000 is considered freely water and ethanol soluble [46]. The solubility of drugs can be enhanced by PEG-4000, as PEG-4000 is considered a good surfactant [47]. The PEG increases hydrodynamic size of NPs, thereby prolonging their circulation duration by decreasing renal clearance [48].

The SFB-NPs are considered to be copolymer nanoparticles that were produced by the use of a solvent evaporation technique. This is an easy process for encapsulating hydrophilic and hydrophobic medications in nanoparticles, and it has been used successfully using a cosolvent in a modified solvent evaporation method. It is possible to either boost the drug’s EE% in nanoparticles or lower the mean particle size of the nanoparticles [49]. Although PEG-4000 is mostly used as a coating polymer, it may also be utilized primarily for polymeric insertion to increase the solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble pharmaceuticals. It has been described and used to formulate highly responsive networks for the improvement of meloxicam solubility by cross-linking polymerization, among other things [50]. It was also used as a carrier material to increase the solubility of the medication andrographolide, among other things [51]. Another study revealed that the coprecipitation approach was used to develop Fe3O4 nanoparticles using PEG-4000 polymer as a solubilizing material. SFB-NPs is not considered nanocrystal, due to the nanocrystals are formed in the form of crystals smaller than a nanometer and loaded with 100% of drug. Moreover, there is no carrier material in polymeric nanoparticles [52]. Glycerol was used in this study as a humectant, thickener, and emulsifier. Glycerol can change the repellent and attractive forces determining an emulsion’s stability and rheological qualities. The inclusion of glycerol in the emulsion formulation affects the optical qualities of emulsions as well as their stability and rheological properties [53].

3.1 EE%

The loading efficiency is based on the combination of polymer–drug and the method used [54]. The EE% was found to be 73.7 ± 0.8%. It is indicating that SFB could efficiently entrap within PEG-4000 polymer. This percent of entrapment was achieved with the addition of glycerol during the preparation process, which acts as a surfactant. The surfactant generally reduces the surface tension and eases the entrapment process. However, in our study, glycerol was used for this purpose to increase the particle wetting and facilitate its entrapment within the polymer [20].

The EE% has no upper limit; it is usually determined by the drug’s solubility (the soluble drug has low EE% and vice versa). Also, polymer ratios affect EE%; the higher the polymer ratio, the lower the EE%. Therefore, the EE% of SFB in PNs was sufficient; and could not increase due to SFB’s solubility in aqueous media, which allowed SFB to escape from PNs [55]. However, this percentage is considered appropriate and has been agreed upon Khaira et al. observed that the medication concentration of various types of nanoparticle formulations ranged between 50 and 70%. They noticed that increasing the drug–polymer ratio (1:5) resulted in an increase in drug content. Meanwhile, the medication content may be lowered due to the polymer’s separation capacity [56].

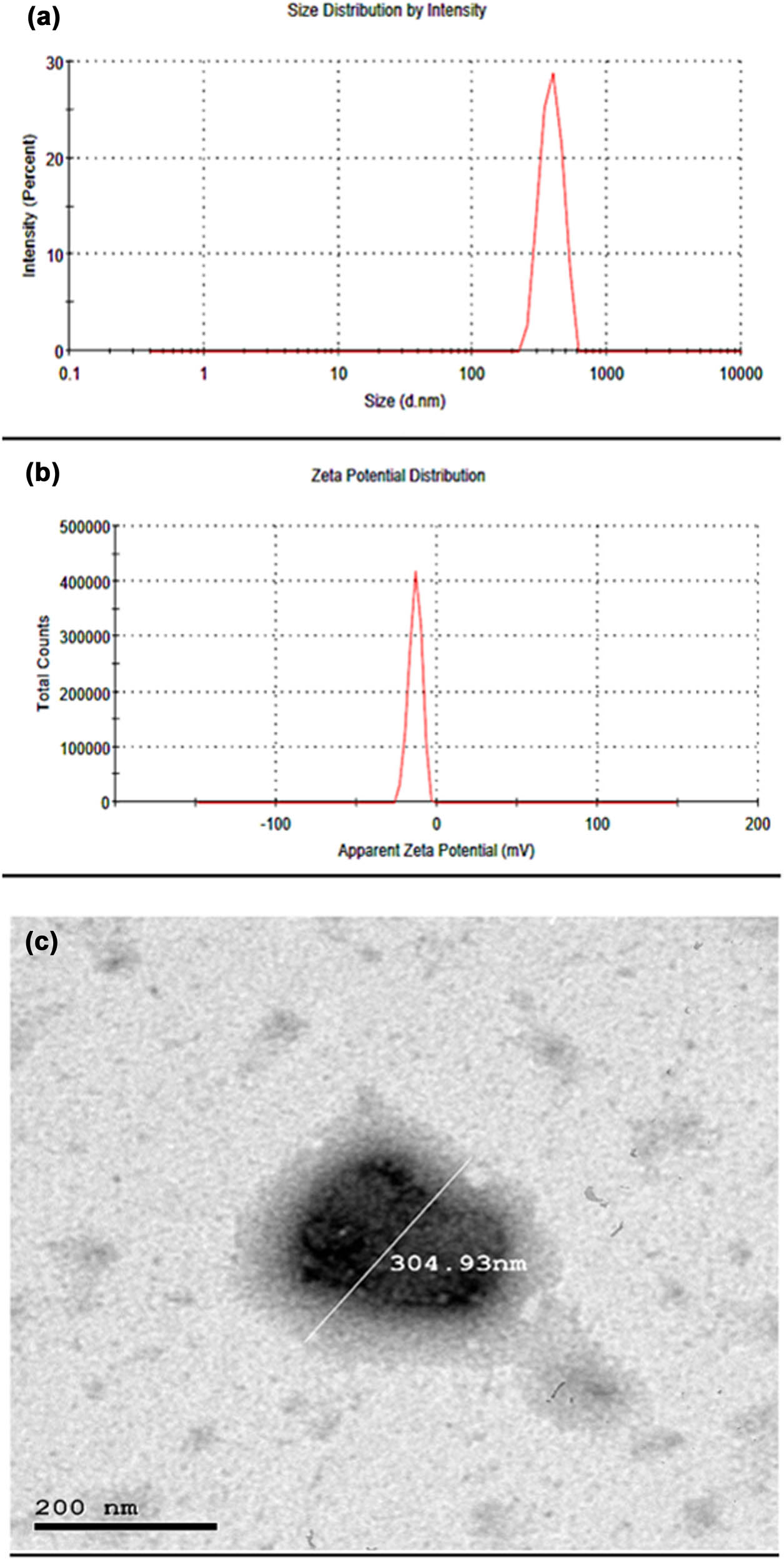

3.2 Evaluation of particle size and zeta potential

The particle size analysis of the prepared formula SFB-NPs showed an average particle size of 389.7 ± 16.49 nm (Figure 2a) with an acceptable nanometer range [57]. The technique used in the preparation process involves rapid mixing with a stirrer to achieve homogeneous supersaturation conditions and regulated SFB precipitation within the PEG-4000 polymer. Rapid mixing conditions are reached via precipitation geometries with two impinging fluid streams. The organic stream containing the SFB, as well as the antisolvent streams, are combined in a restricted chamber to induce homogeneous and fast precipitation of all components, resulting in NPs that are sterically stabilized by the glycerol [58,59]. The size distribution of the nanoparticles produced by this technique ranges from 30 to 300 nm, our formulated SFB-NPs falling with this range. Fine-tuning the kinetics of micromixing (flow rates and mixer geometry), solute nucleation and growth, and block copolymer structure may all be done quickly [60]. Moreover, PDI was 0.703 ± 0.12, which is less than 1 indicates that the particle size distribution is uniform. Ideally, the PDI of range (0.05–0.7) is used by various size distribution algorithms [61]. The zeta-potential of the SFB-NPs was recorded by dynamic light scattering (DLS) to be −13.5 ± 12.1 mV (Figure 2b), which confirms the stability of SFB-NPs. Positive or negative charges with a higher number increase the repulsive interaction, resulting in more stable particles, which prevents the particles aggregation [62]. The resulted value can make repulsion enough to prevent the flocculation and dispersion of particles together [63]. Also, SFB-NPs had a relatively accepted zeta-potential due to the hydrophilic polymer chain shielding effect of PEG-4000 [6,22]. This size is an appropriate size to internalize the cell membrane. This size can penetrate the cell membrane. Other studies showed NPs could internalize with sizes smaller than 50 nm. The NPs uptake is decreased for a smaller size of 15–30 nm and bigger of 70–240 nm [64]. Larger size could be internalized by phagocytosis [65]. Other studies showed that a smaller microsphere can also attach to cell membranes faster and stronger [66,67]. Moreover, the particles of smaller sizes have rapid internalization in cells [68]. Comparatively, microrod particles showed nonspecific cell uptake, whereas spherical particles showed a stronger apoptotic signal and proliferation inhibition, as well a higher rate of apoptosis [69]. It has been discovered that upon endocytosis, different particles spatially segregate in the cytoplasm according to their size and shape [70]. In mice, a study using spheres and elliptical disks of varying sizes (0.1–10 μm) and shapes (spheres vs elliptical disks) indicates that spheres were endocytosed more rapidly, whereas disks circulated longer in the blood with a higher targeting specificity [69,71].

(a) SFB-NPs particle size distribution, (b) SFB-NPs zeta potential as measured using dynamic light scattering using Malvern zetasizer nano, and (c) TEM image of SFB-NPs with a well-identified spherical particle and uniform size.

3.3 TEM

The average sizes of nanoparticles and the particle morphology were estimated by TEM (Figure 2c). TEM micrographs showed nanosized, and well-identified spherical particles. The showed size was ≅304.93 nm. These findings are agreed with the results obtained from zetasizer (DLS) equipment, which recorded ≅389.7 ± 16.49 nm. Because the surfactant interfered with the hydrodynamic diameter, it was expected that DLS mean and median values would be slightly higher than TEM. However, DLS-numbers are similar to TEM results, although DLS-intensity differs significantly from TEM. The existence of larger particles may contribute to an increase in light scattering, moving the observed particle size toward larger values because the particle size distribution is not narrow [72].

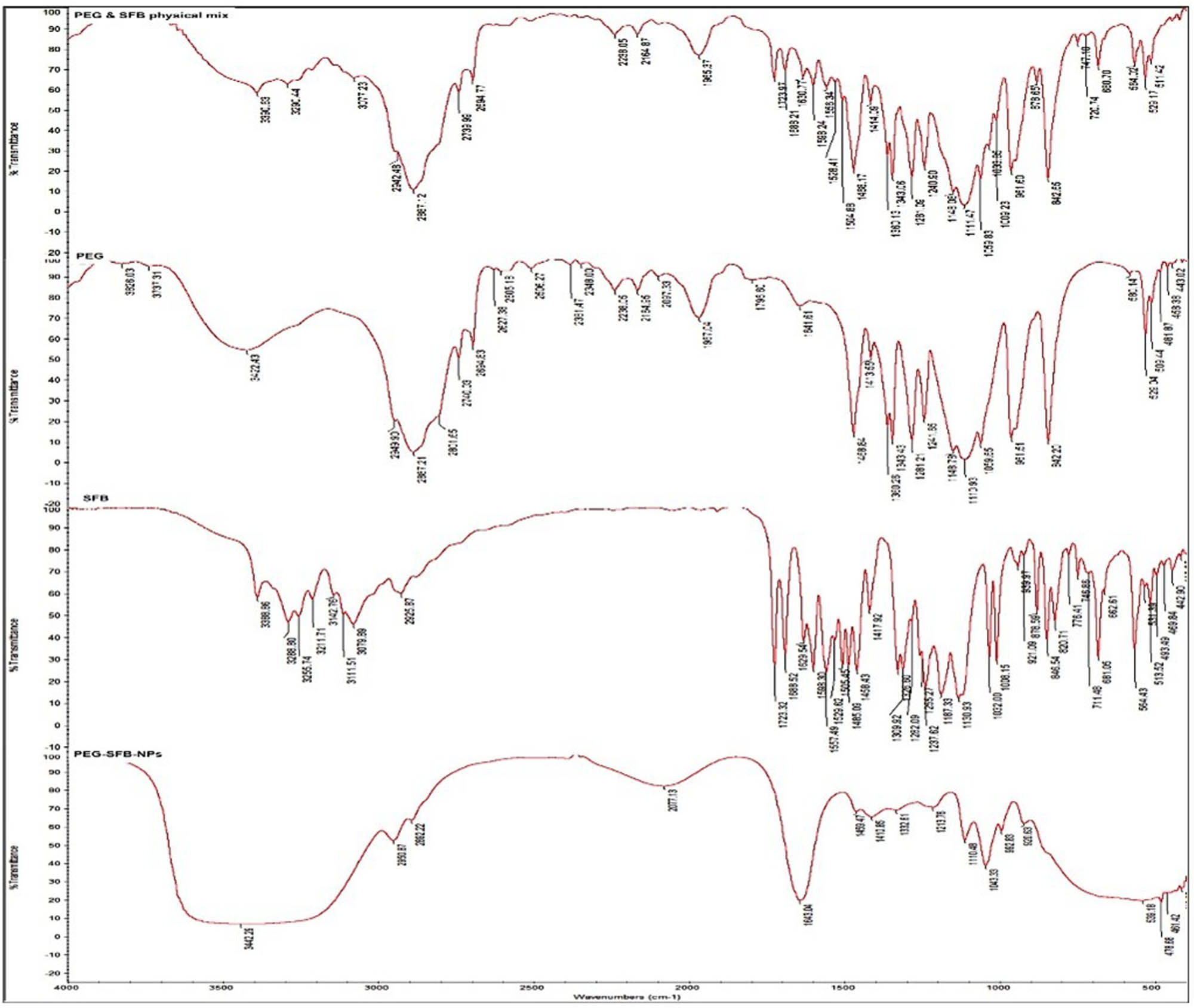

3.4 FTIR

FTIR analysis was used to corroborate the structure of the final product and synthesis intermediates (Figure 3). Due to the C–H stretching in the PEG chain, the pure PEG spectra exhibit two prominent peaks between 2694.83 and 3422.43 cm−1. In the region of 3422.43 cm−1, the OH stretching vibration is recorded, revealing an intermolecular hydrogen bonding nature. Due to the N–H stretching of amide, the spectra of SFB exhibits two distinct peaks at 3079.89 and 3388.86 cm−1. The measured peaks at 3079.89 and 2925.87 cm−1 correspond to the aromatic and aliphatic CH C–H stretching bands, respectively. The peak at 1688.52 cm−1 represents the amide C═O group. The broad peak was given to the –OH group in the region of 3442.29 cm−1 attributable to the produced sample’s water content [73,74,75]. The physical mixture spectrum shows all characteristic peaks in all of the individual compounds with no new unwanted peaks compared with SFB-NPs that confirm the compatibility of SFB and PEG. Moreover, the formulated PEG-SEB-NPs showed no unwanted peaks to verify that the SFB can release from the formed NPs. Furthermore, the SFB characteristic peaks at 3079.89 and 3388.86 cm−1 peaks were disappeared in the formula due to the complete entrapment of SFB in SFB-NPs. The absorption bands revealed no significant interaction between the two SFB and PEG, all materials were compatible with those of their raw powders. These results are agreed with previously reported results by Fu et al. [76]. The SFB-NPs showed an improved solubility in distilled water and phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) at 37.5°C. This is owing to the presence of polymer PEG-4000 in the formula, which is known to enhance the drug solubility [77]. In addition to the SFB NP’s size, which is in the nanorange, this nanosize can efficiently enhance the solubility of poorly soluble drugs such as SFB [78].

FTIR of PEG, SFB, physical mixture of PEG and SFB, and the formulated SFB-NPs.

3.5 Physical stability

The physical stability of all prepared SFB-NPs was investigated for 3 months at 25 ± 1 and 4.0 ± 1°C, respectively. The results revealed that there was no difference in color or morphology between the two conditions studied. Furthermore, using the previously prepared SFB-NPs, a nonsignificant (p ≥ 0.05; ANOVA/Tukey) change in particle sizes and potentials was observed. Fernando et al. [79] stated that the nanoparticles can be stabilized by storing at room temperature. The prepared nanoparticles were stabilized for an extended period, which agreed with our results. It could be concluded that SFB-NPs generated utilizing the polymeric SFB-NPs were stable for 3 months at the two temperatures that were tested.

3.6 In vitro anticancer biological activities

In our study, we used DOX as a positive control in A549 cell lines because it is considered as the most common and effective anticancer drug in lung cancer treatment regimens [80]. Similarly, we used Tam as positive control in MCF-7 cell lines as it is a powerful anticancer drug that is considered estrogen antagonist [81]. Tam has found to have cytostatic (producing G0–G1 arrest) and cytotoxic (inducing apoptosis) effects [82,83]. The cleavage of caspase-3 and its downstream target PARP indicates that Tam-induced growth suppression of 5-aza-dC/trichostatin A – pretreated cells involves apoptosis. Moreover, Tam caused Bcl-2 downregulation in MDA-MB-231 cells that reexpressed ER without any changes in Bax expression, as reported previously for MCF7 cells [84], showing that the Bcl-2 family is involved in Tam-mediated apoptosis. Therefore, we want to evaluate our formula using two positive control; one was the SFB free drug, whereas the other was most widely used lung and breast cancer treatment regimens.

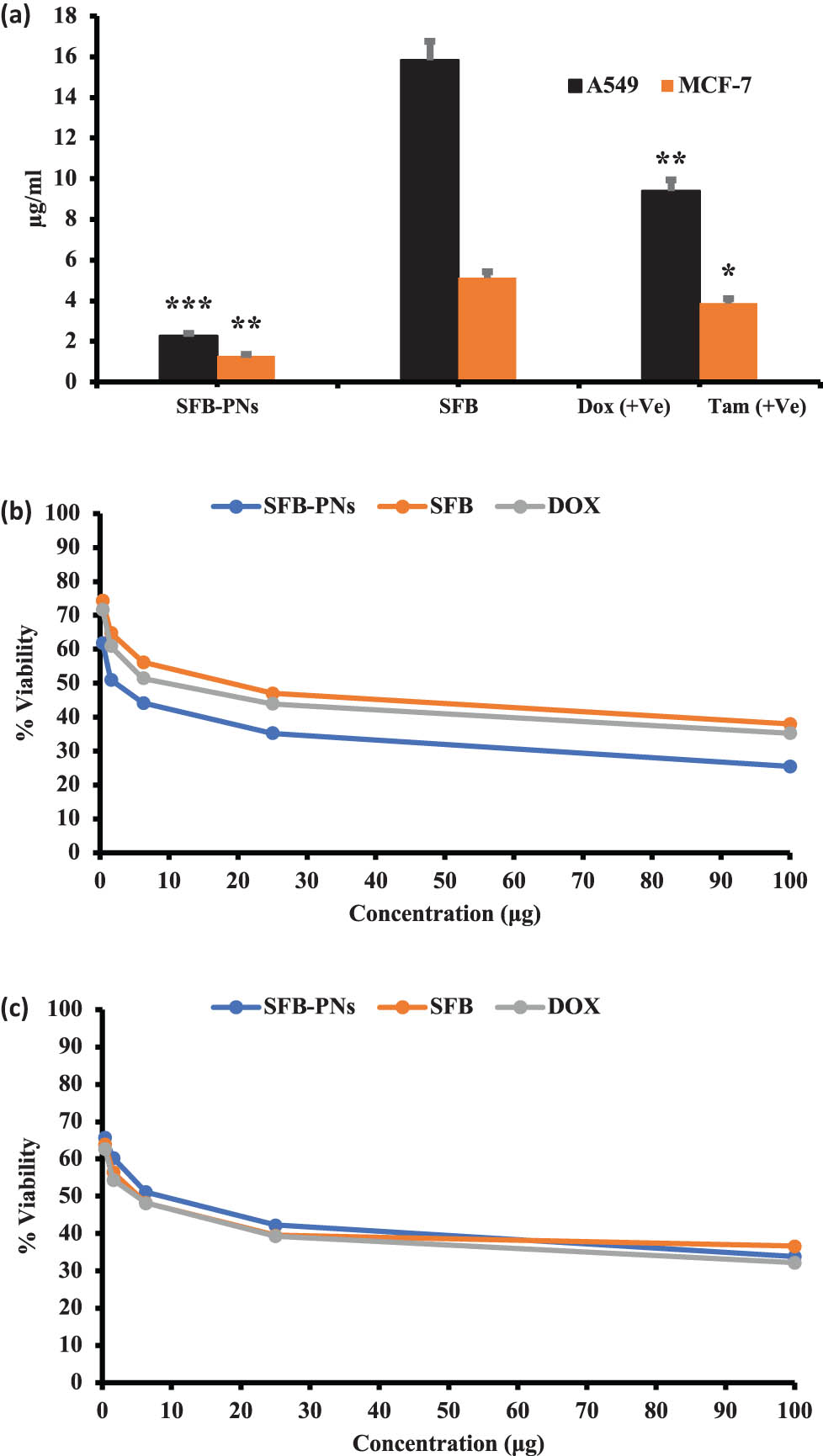

3.6.1 Cell viability assay and antiproliferative activity

The median inhibitory concentration (IC50) was estimated using the T Graph Pad Prism program. The IC50 results are given in Figure 4, SFB-NPs inhibited cell proliferation in A549 and MCF-7 cells after 48 h of treatment in a dose-dependent manner 1.28–2.26 µg/mL (Figure 4a). The results indicated that SFB and SFB-NPs had a differential impact on the A549 cancer cell line, with IC50 values of (2.26 and 15.83 µg/mL) compared to the reference medication DOX, which had an IC50 value of 9.39 µg/mL (Figure 4b). Additionally, SFB-NPs had a reduced IC50 of 1.28 µg/mL compared to MCF-7 cells, with a high IC50 of 5.12 and 3.87 µg/mL for SFB and positive control Tam, respectively (Figure 4c). SFB-NPs showed IC50 value of 2.26 µg/mL and decreased cell viability in A549 cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner with a concentration range from 100 to 0.39 µg/mL after 48 h of incubation to show cell viability from 25.48 to 61.81% compared to SFB free drug from 38 to 74.26% and DOX from 35.24 to 71.65%. Furthermore, SFB-NPs showed IC50 value of 1.28 µg/mL and decreased cell viability in MCF-7 breast cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner with a concentration range from 100 to 0.39 µg/mL after 48 h of incubation to show cell viability from 33.83 to 65.74% compared to SFB free drug from 36.66 to 63.97% and DOX from 32.21 to 62.77%. This demonstrates the fact that NP can considerably improve cytotoxicity, and it can deliver a sufficient amount of SFB with a high rate of release and bioavailability, which actively targeted against cancer once entering the cell, indicating its anticancer effectiveness compared to free-BB, which exhibited significantly lower cytotoxicity in both A549 and MCF-7 cells [85,86,87].

Cytotoxicity-IC50 of A549 and MCF-7 cell lines treated with SFB-NPs. Cells were treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of anticancer drugs. (a) IC50 of concurrent drugs for both cell lines. Cells were treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of SFB, SFB-PNs, DOX, and Tam on (b) cell viability dose response curve of A549 cell lines, and (c) cell viability dose response curve of MCF-7 cancer cell lines, respectively. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, or ***p ≤ 0.001 denote statistically significant differences compared to control cells.

DOX and Tam are the most widely used chemotherapy in the treatment protocols of different types of cancer. We designed and prepared a nanoparticle delivery system for SFB antitumor drug in vitro to evaluate its antitumor activity in two different types of cancer, which found to be related and linked somehow with each other as breast cancer, which has the potential to spread to the lungs or the area between the lung and the chest wall, causing fluid to build up around the lung. Based on recent studies, women who have had breast cancer have a much higher chance of acquiring lung cancer later in life, probably due to a link between radiotherapy and smoking [88]. Furthermore, it has been reported that 60–70% of breast cancer patients who eventually died were diagnosed with lung metastasis [89].

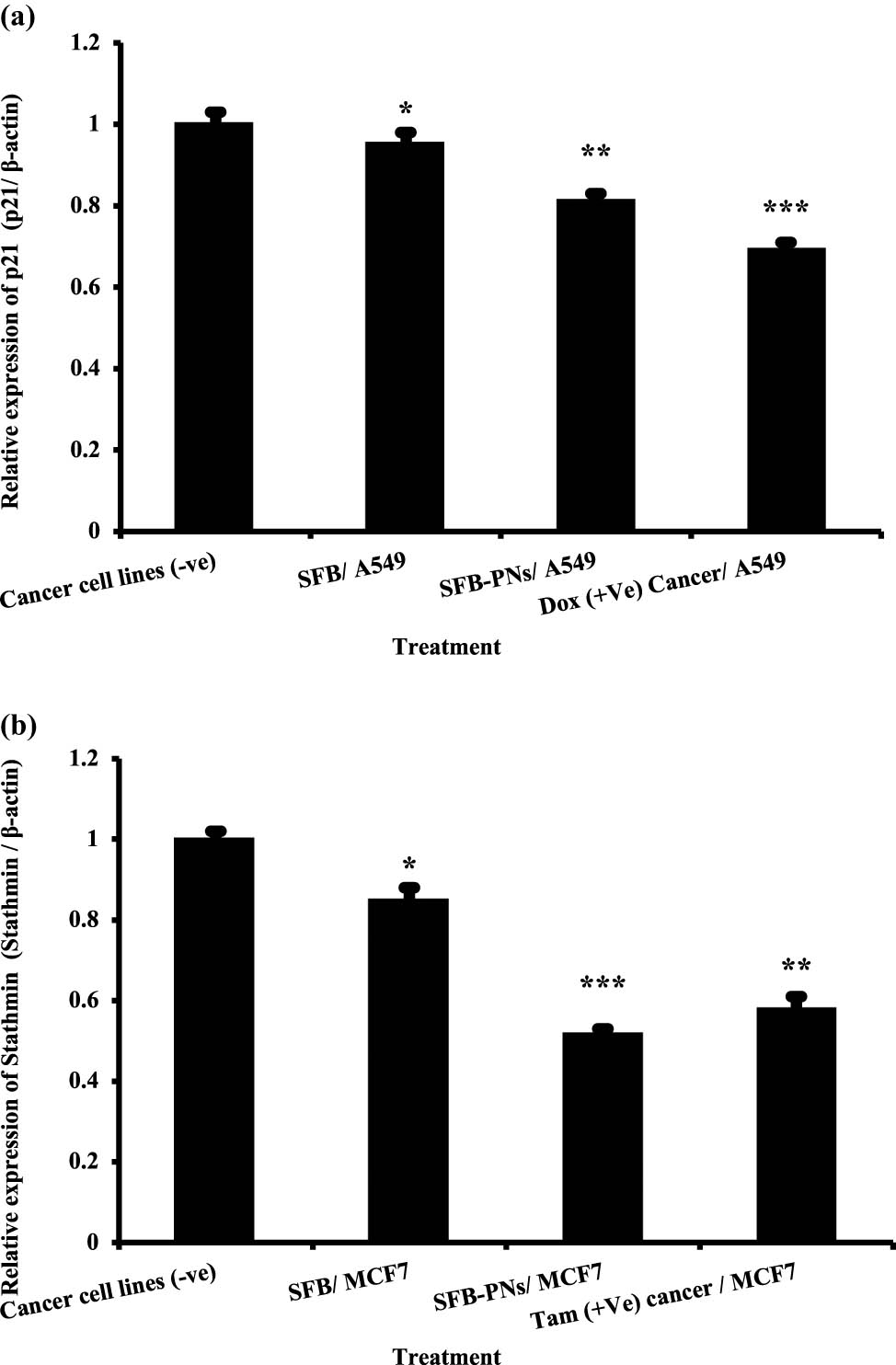

3.6.2 Gene expression in lung and breast cell line

In each case, the gene expression study of lung and breast cancer markers was carried out using two cancer-related genes, namely p21 and STMN1. Results (Figure 5a) demonstrated that the expression levels of the p21 gene were significantly higher in negative samples of lung cancer cell lines when compared to treated cell lines. As opposed to this, when A549 cell lines were treated with SFB or SFB-NPs, the expression levels of the p21 gene were significantly decreased compared to negative samples of lung cancer cell lines. Furthermore, when comparing the negative control MCF-7 cells to the positive control (Tam-treated) breast cancer cells, it was discovered that the STMN1 genes were decreased significantly in MCF-7 cell lines treated with SFB-NPs by approximately two-fold in the negative control cells MCF-7 cells (Figure 5b). A549 and MCF-7 cancer cells exposed to SFB-NPs had lower levels of proliferation and increased levels of apoptosis by showing downregulation significantly in the expression levels of p21 and STMN1 that suppresses the cell viability, which reflects the growth states of cancer cells via shutting down the signaling pathway that controls the activation of the Rat sarcoma/oncogene encodes an intracellular signal-transduction protein (RAS)/mitogen-activated protein kinase/ signal transduction pathway (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway [90]. SFB showed no significant variation in the rate of A549 and MCF-7 cell growth inhibition when evaluated in vitro at varying concentrations compared with cell inhibition by SFB-NPs, which reached a maximum at a certain level of NPs incorporation. Moreover, inhibition increased in proportion to the increase in nanoparticle concentration, indicating that nanoparticle incorporation effectively inhibited cell proliferation. Our results are parallel to Liu et al. [91], who revealed that SFB could suppress the proliferation of PLC/PRF/5 and HepG2 HCC cells by blocking the Raf kinase and MEK/ERK signaling pathway, resulting in a decreased level of cyclin D. To make apoptosis happen, the enzyme Raf was inhibited, which caused the level of elF4E phosphorylation to decrease, and Mcl-1 expression to be suppressed. These results agreed with Edwards et al. [92], who stated that the nanoformulation showed enhanced penetration resulting of suppression in cell growth, and p21 accompanied cell cycle arrest. The nanoparticles have increased absorbability and biological activity due to the size distribution and large surface area. Therefore, these particles have a wide variety of advantageous features that make them good drug-delivery vehicles. These features increase absorption, utilization, and stability, helping medicine target, last longer, and eliminate unwanted effects [93]. Based on these observations, it appears that the efficacy of SFB-NPs in targeting and inhibiting the growth and viability of cancer cells was significantly greater than that of free SFB.

(a) The expression of p21 gene in lung cancer cell lines treated with SFB, SFB-NPs, and DOX. Expression levels were standardized using the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Mean values within tissue with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (p < 0.05). (b) The expression of Stathmin-1 gene in breast cancer cell lines treated with SFB, SFB-NPs, and Tam. Expression levels were standardized using the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Mean values within tissue with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0.05). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, or ***p ≤ 0.001 denote statistically significant differences compared to control cells.

STMN1 has been identified as a possible target for the therapy of solid malignant tumors. Specifically, a number of target-specific anti-STMN1effectors, such as ribozymes, monoclonal antibodies, shRNA, and siRNA, have been utilized extensively in vitro and in vivo to examine STMN1-targeted treatment methods [94]. STMN1 is commonly overexpressed in human malignancies, and anti-STMN1 therapy lowers cell proliferation, clonal expansion, cell motility, metastasis, and enhances apoptosis. Kang et al. demonstrated that STMN1 expression is reduced in cancer cells. Cell proliferation, colony formation, cell invasion, and migratory ability are dramatically reduced, and cells are arrested in the G1 phase [95]. As a result, chemotherapeutic agents, which decrease expression of STMN1 could be a viable option for treating malignant tumors as breast cancer [96]. A growing amount of evidence suggest that p21 is involved in promoting a proliferative response to chemotherapy. p21 contributes to DNA repair in two ways: indirectly, by slowing cell cycle advancement to allow time for DNA repair, and directly, by controlling the connections between repair pathway components [97]. p21 has been demonstrated to improve chemotherapy-induced DNA damage repair and protect glioma cells from apoptosis [98]. Furthermore, the radiation-induced p53-independent overexpression of p21 in stem cells prevented damage accumulation and boosted stem cell pool development. These findings support the alternative idea that early, high levels of p21 expression in therapy promote a proliferative cell destiny in the end [99]. Chien-Hsiang et al. demonstrated that p21 levels were low in S/G2 – the cell-cycle phases with the highest amounts of DNA damage and a major reservoir of senescence-destined cells – during drug treatment. Chk1 activity and proteasomal degradation were identified as biological mechanisms that inhibited p21 expression in highly damaged cell-cycle phases using genetic and pharmacological perturbations [100]. The reported inhibitory regulation of p21 expression in S/G2 cells would serve to raise the DNA damage threshold for activating the p21 response, allowing only cells with substantial DNA damage to exit the cell cycle. Other p21 regulatory mechanisms, such as miRNA and p21 phosphorylation, are not known to be involved in modifying the p21 induction threshold across the cell cycle [101].

3.6.3 DNA damage in lung and breast cell lines

Human A549 lung and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines were treated as monotherapies using SFB-NPs, SFB, Tam, or DOX. Various drug activities changed even among different forms of cancer, indicating the significant differences between cancer types. Comet assay was used to test for DNA damage in A549 cancer cell lines, as shown in Table 2. The data revealed that untreated cell lines with a proven history of lung and breast cancer produced significant reductions in DNA damage levels with 9.50 and 10.25%, respectively. On the contrary, cancer cells treated with SFB-NPs had the highest amounts of DNA damage with a value of 25.50 and 26.75% when compared with free drugs SFB, DOX positive control, Tam positive control in both cell lines as illustrated in Table 2. These findings suggest that SFB-NPs hold more cellular absorption and greater effectiveness causing higher cytotoxicity by showing a significant increase in DNA damage, which essentially promotes apoptosis when compared to free SFB. A five-grade scale ranging from 0 to 4 is used to calculate comet visual grading. Grade 4 comet cells have DNA distributed throughout the tail, head, and middle; however, grade 0 comet cells have all the DNA concentrated in the head. For example, with a scale ranging from 0 to 400, comet counts can yield a quantitative measurement for 100 cells. Higher cell destruction suggests that the majority of the DNA is in the tail, as well. Unfragmented cells [102] indicate a reduction in the score.

Visual score of DNA damage in lung and breast tumor cell lines treated with SFB, SFB-NPs, DOX, and Tam

| Treatment | No. of cells | Class** | DNA damaged cells% (mean ± SEM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of samples | Analyzed* | Comets | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Lung tumor cell lines (A549) | ||||||||

| Cancer cell lines (−ve) | 4 | 400 | 38 | 362 | 23 | 11 | 4 | 9.50 ± 1.55d |

| SFB – A549 | 4 | 400 | 58 | 342 | 29 | 17 | 12 | 14.51 ± 1.04c |

| SFB-PNs – A549 | 4 | 400 | 102 | 298 | 30 | 28 | 44 | 25.50 ± 1.04a |

| DOX (+ve) Cancer | 4 | 400 | 95 | 305 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 23.75 ± 1.13ab |

| Breast tumor cell lines (MCF-7) | ||||||||

| Cancer cell lines (−ve) | 4 | 400 | 41 | 359 | 25 | 10 | 6 | 10.25 ± 1.49d |

| SFB-MCF-7 | 4 | 400 | 69 | 331 | 33 | 21 | 15 | 17.27 ± 0.86bc |

| SFB-PNs – MCF-7 | 4 | 400 | 107 | 293 | 36 | 31 | 40 | 26.75 ± 0.86a |

| Tam (+ve) MCF-7 | 4 | 400 | 98 | 302 | 34 | 35 | 29 | 24.50 ± 1.04ab |

*: Number of cells examined per a group, **: class 0 = no tail; 1 = tail length <diameter of nucleus; 2 = tail length between 1× and 2× the diameter of nucleus; and 3 = tail length >2× the diameter of nucleus. Means with different superscripts (a, b, c, d) between treatments in the same column are significantly different at p < 0.05.

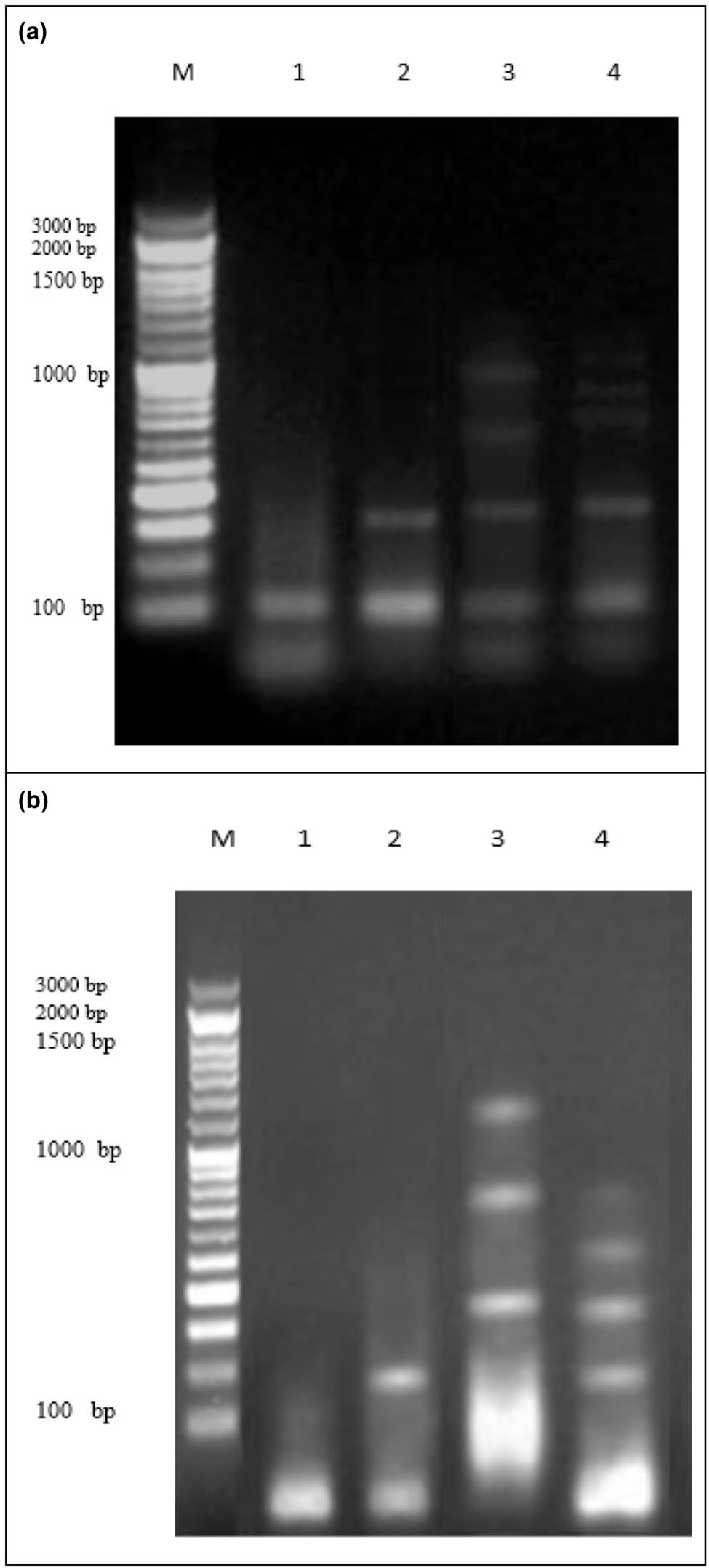

3.6.4 Measurement of DNA fragmentation in lung and breast cancer cell lines

The rate of DNA fragmentation determined in A549 and MCF-7 cancer cell lines are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 6a. The results show that negative samples of lung cancer cell lines exhibited a significant decrease in DNA fragmentation rates compared with those in treated samples (SFB-NPs, SFB, DOX (+ve) lung cell line, and Tam (+ve) breast cell line). The results showed that the rate of DNA fragmentation was increased significantly in positive control (DOX-treated) lung cancer cell lines. In addition to cell lines treated with SFB-NPs, compared with freeSFB and negative control cancer cell lines. Moreover, the effect of the SFB-NPs treatments on the percentage of DNA fragmentation in the breast cancer cell lines was investigated (Table 3 and Figure 6b). DNA fragmentation rates in negative samples of breast cancer cell lines were significantly lower than in treated samples with SFB, SFB-NPs, or Tam(+ve) cell lines. In contrast, the effect of the SFB-NPs treatments on the percentage of DNA fragmentation in the breast cancer cell had higher DNA damage values (P < 0.01), than those treated with Tam (positive control) and SFB.

DNA fragmentation detected in lung & breast cancer cell lines treated with SFB, SFB-NPs, DOX, and Tam

| Treatment | DNA fragmentation% M ± SEM | Change | Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung breast tumor cell lines (A549) | |||

| Cancer cell lines (−ve) | 9.1 ± 0.23c | 0 | 0 |

| SFB – A549 | 17.1 ± 0.54 b | 8 | −42.85 |

| SFB-NPs – A549 | 26.5 ± 0.47a | 17.4 | 24.28 |

| DOX (+ve) cancer | 23.1 ± 0.17ab | 14 | 0 |

| Breast tumor cell lines (MCF-7) | |||

| Cancer cell lines (−ve) | 10.2 ± 0.26c | 0 | 0 |

| SFB-MCF-7 | 19.2 ± 0.28c | 9 | −40.79 |

| SFB-NPs-MCF-7 | 28.9 ± 0.35a | 18.7 | 23.02 |

| Tam (+ve) MCF-7 | 25.4 ± 0.25ab | 15.2 | 0 |

Means with different superscripts (a, b, c) between treatments in the same column are significantly different at p < 0.05.

(a) DNA fragmentation detected with agarose gel in lung cancer cell lines treated with SFB, SFB-NPs, DOX. M: represent DNA marker, lanes 1: represents cancer cell lines (−ve), lane 2: represents SFB-A549, lane 3: represents SFB-NPs-A549, lane 4: represents DOX (+ve) cancer. (b) DNA fragmentation detected with agarose gel in breast cancer cell lines treated with SFB, SFB-NPs, Tam. M: represent DNA marker, lanes 1: represents cancer cell lines (−ve), lane 2: represents SFB, lane 3: represents SFB-NPs, lane 4: represents Tam (+ve) MCF-7.

Nuclear DNA fragmentation, characterized by the appearance of distinctive ladder DNA fragments of 180–200 base pairs and multiples thereof on an agarose gel, is one of the biochemical hallmarks of the apoptotic process [103]. However, random DNA breakage in necrotic cells results in a diffuse smear on DNA electrophoresis. As a result, the DNA gel electrophoresis method was used to confirm the likely mode of SFB-NPs-induced cell death. DNA fragmentation and nuclear condensation are two characteristics of late apoptosis [104].

4 Conclusions

In a simple and reproducible synthesis technique, homogeneously dispersed nanoparticles were prepared with acceptable size, PDI values, and zeta potential. Moreover, the particles showed good stability during the whole study. MTT assay, RNA isolation and RT reaction, qPCR, DNA fragmentation measurements, and comet assay indicate that the drug produces a large decrease in overall cell number. Moreover, a significant down expression of nuclear protein P21 gene in lung cancer cell line (A549) and STMN1 gene in breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) was demonstrated as an important factor for the proliferation, differentiation, and death of both cells. The results also confirmed that the cytotoxic effect of SFB-NPs treatment allows the development of apoptotic DNA fragments on the agarose gel compared to the free SFB. Based on these promising results, additional clinical trials should be conducted on using this polymeric nanoparticle (SFB-NPs) formulation as a unique treatment for lung and breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University, for supporting this project. The authors also thank Qassim University for providing technical support.

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research (project number QU-IF-1-2-1).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] White PT, Cohen MS. The discovery and development of sorafenib for the treatment of thyroid cancer. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10(4):427–39.10.1517/17460441.2015.1006194Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Gauthier A, Ho M. Role of sorafenib in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatol Res. 2013;43(2):147–54.10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01113.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Tang W, Chen Z, Zhang W, Cheng Y, Zhang B, Wu F, et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):87.10.1038/s41392-020-0187-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Gao JJ, Shi ZY, Xia JF, Inagaki Y, Tang W. Sorafenib-based combined molecule targeting in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(42):12059–70.10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12059Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Dattachoudhury S, Sharma R, Kumar A, Jaganathan BG. Sorafenib Inhibits Proliferation, Migration and Invasion of Breast Cancer Cells. Oncology. 2020;98(7):478–86.10.1159/000505521Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Choi I, Park SY, Lee SW, Kang Z, Jin YS, Kim IW. Dissolution enhancement of sorafenib tosylate by co-milling with tetradecanol post-extracted using supercritical carbon dioxide. Pharmazie. 2020;75(1):13–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Abdellatif AAH, El-Telbany DFA, Zayed G, Al-Sawahli MM. Hydrogel containing PEG-coated fluconazole nanoparticles with enhanced solubility and antifungal activity. J Pharm Innov. 2018;14(2):112–22.10.1007/s12247-018-9335-zSuche in Google Scholar

[8] Kwok PC, Chan HK. Nanotechnology versus other techniques in improving drug dissolution. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(3):474–82.10.2174/13816128113199990400Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Bhatia S. Nanoparticles types, classification, characterization, fabrication methods and drug delivery applications. Nat Polym Drug Delivery Syst. 2016;33–93. ISBN: 978-3-319-41129-3.10.1007/978-3-319-41129-3_2Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Salatin S, Barar J, Barzegar-Jalali M, Adibkia K, Kiafar F, Jelvehgari M. Development of a nanoprecipitation method for the entrapment of a very water soluble drug into Eudragit RL nanoparticles. Res Pharm Sci. 2017;12(1):1–14.10.4103/1735-5362.199041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Liu J, Boonkaew B, Arora J, Mandava SH, Maddox MM, Chava S, et al. Comparison of sorafenib-loaded poly (lactic/glycolic) acid and DPPC liposome nanoparticles in the in vitro treatment of renal cell carcinoma. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104(3):1187–96.10.1002/jps.24318Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Lee SM, Park H, Yoo KH. Synergistic cancer therapeutic effects of locally delivered drug and heat using multifunctional nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2010;22(36):4049–53.10.1002/adma.201001040Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Weiss RH. p21Waf1/Cip1 as a therapeutic target in breast and other cancers. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(6):425–9.10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00308-8Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Asada M, Yamada T, Ichijo H, Delia D, Miyazono K, Fukumuro K, et al. Apoptosis inhibitory activity of cytoplasmic p21(Cip1/WAF1) in monocytic differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18(5):1223–34.10.1093/emboj/18.5.1223Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Cmielova J, Rezacova M. p21Cip1/Waf1 protein and its function based on a subcellular localization [corrected]. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(12):3502–6.10.1002/jcb.23296Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Nemunaitis J. Stathmin 1: a protein with many tasks. New biomarker and potential target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(7):631–4.10.1517/14728222.2012.696101Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Belletti B, Baldassarre G. Stathmin: a protein with many tasks. New biomarker and potential target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15(11):1249–66.10.1517/14728222.2011.620951Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Biaoxue R, Xiguang C, Hua L, Shuanying Y. Stathmin-dependent molecular targeting therapy for malignant tumor: the latest 5 years’ discoveries and developments. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):279.10.1186/s12967-016-1000-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Aronova A, Min IM, Crowley MJP, Panjwani SJ, Finnerty BM, Scognamiglio T, et al. STMN1 is overexpressed in adrenocortical carcinoma and promotes a more aggressive phenotype in vitro. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(3):792–800.10.1245/s10434-017-6296-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Farghaly Aly U, Abou-Taleb HA, Abdellatif AA, Sameh Tolba N. Formulation and evaluation of simvastatin polymeric nanoparticles loaded in hydrogel for optimum wound healing purpose. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:1567–80.10.2147/DDDT.S198413Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Abdellatif AAH. A plausible way for excretion of metal nanoparticles via active targeting. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46(5):744–50.10.1080/03639045.2020.1752710Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Abdellatif AAH, Hennig R, Pollinger K, Tawfeek HM, Bouazzaoui A, Goepferich A. Fluorescent nanoparticles coated with a somatostatin analogue target blood monocyte for efficient leukaemia treatment. Pharm Res. 2020;37(11):217.10.1007/s11095-020-02938-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] de Moura MR, Avena-Bustillos RJ, McHugh TH, Krochta JM, Mattoso LH. Properties of novel hydroxypropyl methylcellulose films containing chitosan nanoparticles. J Food Sci. 2008;73(7):N31–7.10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00872.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Abdellatif AAH, Alturki HNH, Tawfeek HM. Different cellulosic polymers for synthesizing silver nanoparticles with antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):84.10.1038/s41598-020-79834-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Shid RL, Dhole SN, Kulkarni N, Shid SL. Formulation and evaluation of nanosuspension formulation for drug delivery of simvastatin. Int J Pharm Sci Nanotechnol. 2014;7(4):2650–65.10.37285/ijpsn.2014.7.4.7Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Onuki Y, Machida Y, Yokawa T, Seike C, Sakurai S, Takayama K. Magnetic resonance imaging study on the physical stability of menthol and diphenhydramine cream for the treatment of chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2015;63(6):457–62.10.1248/cpb.c15-00192Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Abdellatif AAH, Rasheed Z, Alhowail AH, Alqasoumi A, Alsharidah M, Khan RA, et al. Silver citrate nanoparticles inhibit PMA-induced TNFalpha expression via deactivation of NF-kappaB activity in human cancer cell-lines, MCF-7. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:8479–93.10.2147/IJN.S274098Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Abdellatif AAH, Alsharidah M, Al Rugaie O, Tawfeek HM, Tolba NS. Silver nanoparticle-coated ethyl cellulose inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha of breast cancer cells. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:2035–46.10.2147/DDDT.S310760Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63.10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Hadzsiev K, Komlosi K, Czako M, Duga B, Szalai R, Szabo A, et al. Kleefstra syndrome in Hungarian patients: additional symptoms besides the classic phenotype. Mol Cytogenet. 2016;9:22.10.1186/s13039-016-0231-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Takahashi S, Fukui T, Nomizu T, Kakugawa Y, Fujishima F, Ishida T, et al. TP53 signature diagnostic system using multiplex reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction system enables prediction of prognosis of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer. 2021;28(6):1225–34.10.1007/s12282-021-01250-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Fujita K, Omori T, Hara H, Shinno N, Yamamoto M, Aoyama Y, et al. Clinical importance of carcinoembryonic antigen messenger RNA level in peritoneal lavage fluids measured by transcription-reverse transcription concerted reaction for advanced gastric cancer in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2021;1–18. 10.1007/s00464-021-08539-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Yang Q, Feng M, Ma X, Li H, Xie W. Gene expression profile comparison between colorectal cancer and adjacent normal tissues. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(5):6071–8.10.3892/ol.2017.6915Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Olive PL, Banath JP, Durand RE. Heterogeneity in radiation-induced DNA damage and repair in tumor and normal cells measured using the “comet” assay. 1990. Radiat Res. 2012;178(2):AV35–42.10.1667/RRAV04.1Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Collins A, Dusinska M, Franklin M, Somorovska M, Petrovska H, Duthie S, et al. Comet assay in human biomonitoring studies: reliability, validation, and applications. Env Mol Mutagen. 1997;30(2):139–46.10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1997)30:2<139::AID-EM6>3.0.CO;2-ISuche in Google Scholar

[36] Yawata A, Adachi M, Okuda H, Naishiro Y, Takamura T, Hareyama M, et al. Prolonged cell survival enhances peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer cells. Oncogene. 1998;16(20):2681–6.10.1038/sj.onc.1201792Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Khan AA, Mudassir J, Akhtar S, Murugaiyah V, Darwis Y. Freeze-dried lopinavir-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for enhanced cellular uptake and bioavailability: statistical optimization, in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(2):97. 10.3390/pharmaceutics11020097. Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Chen R, Guo X, Liu X, Cui H, Wang R, Han J. Formulation and statistical optimization of gastric floating alginate/oil/chitosan capsules loading procyanidins: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;108:1082–91.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.032Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Gyawali B, Prasad V. Me too-drugs with limited benefits – the tale of regorafenib for HCC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(1):62.10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.190Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Baeza A, Ruiz-Molina D, Vallet-Regi M. Recent advances in porous nanoparticles for drug delivery in antitumoral applications: inorganic nanoparticles and nanoscale metal-organic frameworks. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14(6):783–96.10.1080/17425247.2016.1229298Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Itoh N, Santa T, Kato M. Rapid and mild purification method for nanoparticles from a dispersed solution using a monolithic silica disk. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1404:141–5.10.1016/j.chroma.2015.05.047Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Abdellatif AAH, Ibrahim MA, Amin MA, Maswadeh H, Alwehaibi MN, Al-Harbi SN, et al. Cetuximab conjugated with octreotide and entrapped calcium alginate-beads for targeting somatostatin receptors. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4736.10.1038/s41598-020-61605-ySuche in Google Scholar

[43] Verhoef JJ, Anchordoquy TJ. Questioning the use of PEGylation for drug delivery. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2013;3(6):499–503.10.1007/s13346-013-0176-5Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Johnstone SA, Masin D, Mayer L, Bally MB. Surface-associated serum proteins inhibit the uptake of phosphatidylserine and poly(ethylene glycol) liposomes by mouse macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1513(1):25–37.10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00292-9Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Dos Santos N, Allen C, Doppen AM, Anantha M, Cox KA, Gallagher RC, et al. Influence of poly(ethylene glycol) grafting density and polymer length on liposomes: relating plasma circulation lifetimes to protein binding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768(6):1367–77.10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.12.013Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Haglund BO. Solubility studies of polyethylene glycols in ethanol and water. Thermochim Acta. 1987;114(1):97–102.10.1016/0040-6031(87)80246-0Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Tang Y, Li Z, He N, Zhang L, Ma C, Li X, et al. Preparation of functional magnetic nanoparticles mediated with PEG-4000 and application in Pseudomonas aeruginosa rapid detection. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2013;9(2):312–7.10.1166/jbn.2013.1493Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Jokerst JV, Lobovkina T, Zare RN, Gambhir SS. Nanoparticle PEGylation for imaging and therapy. Nanomed (Lond). 2011;6(4):715–28.10.2217/nnm.11.19Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Yadav KS, Sawant KK. Modified nanoprecipitation method for preparation of cytarabine-loaded PLGA nanoparticles. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2010;11(3):1456–65.10.1208/s12249-010-9519-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Khan KU, Minhas MU, Sohail M, Badshah SF, Abdullah O, Khan S, et al. Synthesis of PEG-4000-co-poly (AMPS) nanogels by cross-linking polymerization as highly responsive networks for enhancement in meloxicam solubility. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2021;47(3):465–76.10.1080/03639045.2021.1892738Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Zeng Q, Ou L, Zhao G, Cai P, Liao Z, Dong W, et al. Preparation and characterization of PEG4000 Palmitate/PEG8000 palmitate-solid dispersion containing the poorly water-soluble drug andrographolide. Adv Polym Technol. 2020;2020:1–7.10.1155/2020/4239207Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Arista D, Rachmawati A, Ramadhani N, Eko Saputro R, Taufiq A, Sunaryono A. Antibacterial performance of Fe3O4/PEG-4000 prepared by co-precipitation route. IOP Conf Series: Mater Sci Eng. 2019;515(1):012085.10.1088/1757-899X/515/1/012085Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Mirhosseini H, Tan CP, Taherian AR. Effect of glycerol and vegetable oil on physicochemical properties of Arabic gum-based beverage emulsion. Eur Food Res Technol. 2008;228(1):19–28.10.1007/s00217-008-0901-3Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Abbulu K, Mohan Varma M, Betala S. Formulation and evaluation of polymeric nanoparticles of an antihypetensive drug for gastroretention. J Drug Delivery Therapeutics. 2018;8(6):82–6.10.22270/jddt.v8i6.2018Suche in Google Scholar

[55] El-Say KM. Maximizing the encapsulation efficiency and the bioavailability of controlled-release cetirizine microspheres using Draper-Lin small composite design. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:825–39.10.2147/DDDT.S101900Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Khaira R, Sharma J, Saini V. Development and characterization of nanoparticles for the delivery of gemcitabine hydrochloride. Sci World J. 2014;2014:560962.10.1155/2014/560962Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Padhye SG, Nagarsenker MS. Simvastatin solid lipid nanoparticles for oral delivery: formulation development and in vivo evaluation. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2013;75(5):591–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Essa D, Choonara YE, Kondiah PPD, Pillay V. Comparative nanofabrication of PLGA-chitosan-PEG systems employing microfluidics and emulsification solvent evaporation techniques. Polym (Basel). 2020;12(9):1882. 10.3390/polym12091882.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Dos Santos KM, Barbosa RM, Vargas FGA, de Azevedo EP, Lins A, Camara CA, et al. Development of solid dispersions of beta-lapachone in PEG and PVP by solvent evaporation method. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2018;44(5):750–6.10.1080/03639045.2017.1411942Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Hickey JW, Santos JL, Williford JM, Mao HQ. Control of polymeric nanoparticle size to improve therapeutic delivery. J Control Rel. 2015;219:536–47.10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A, et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57. 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Mahalingam M, Krishnamoorthy K. Fabrication, physicochemical characterization and evaluation of in vitro anticancer efficacy of a novel pH sensitive polymeric nanoparticles for efficient delivery of hydrophobic drug against colon cancer. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2015;5(11):135–45.10.7324/JAPS.2015.501123Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Zanela da Silva Marques T, Santos-Oliveira R, Betzler de Oliveira de Siqueira L, Cardoso VDS, de Freitas ZMF, Barros R, et al. Development and characterization of a nanoemulsion containing propranolol for topical delivery. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:2827–37.10.2147/IJN.S164404Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Foroozandeh P, Aziz AA. Insight into cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2018;13(1):339.10.1186/s11671-018-2728-6Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Rajendran NK, Kumar SSD, Houreld NN, Abrahamse H. A review on nanoparticle based treatment for wound healing. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2018;44:421–30.10.1016/j.jddst.2018.01.009Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Shinde Patil VR, Campbell CJ, Yun YH, Slack SM, Goetz DJ. Particle diameter influences adhesion under flow. Biophys J. 2001;80(4):1733–43.10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76144-9Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Lamprecht A, Schafer U, Lehr CM. Size-dependent bioadhesion of micro- and nanoparticulate carriers to the inflamed colonic mucosa. Pharm Res. 2001;18(6):788–93.10.1023/A:1011032328064Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Desai MP, Labhasetwar V, Walter E, Levy RJ, Amidon GL. The mechanism of uptake of biodegradable microparticles in Caco-2 cells is size dependent. Pharm Res. 1997;14(11):1568–73.10.1023/A:1012126301290Suche in Google Scholar

[69] He Y, Park K. Effects of the microparticle shape on cellular uptake. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(7):2164–71.10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00992Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Xu ZP, Niebert M, Porazik K, Walker TL, Cooper HM, Middelberg AP, et al. Subcellular compartment targeting of layered double hydroxide nanoparticles. J Control Rel. 2008;130(1):86–94.10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Muro S, Garnacho C, Champion JA, Leferovich J, Gajewski C, Schuchman EH, et al. Control of endothelial targeting and intracellular delivery of therapeutic enzymes by modulating the size and shape of ICAM-1-targeted carriers. Mol Ther. 2008;16(8):1450–8.10.1038/mt.2008.127Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[72] Souza TGF, Ciminelli VST, Mohallem NDS. A comparison of TEM and DLS methods to characterize size distribution of ceramic nanoparticles. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2016;733:012039.10.1088/1742-6596/733/1/012039Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Elsayed MM, Mostafa ME, Alaaeldin E, Sarhan HA, Shaykoon MS, Allam S, et al. Design and characterisation of novel sorafenib-loaded carbon nanotubes with distinct tumour-suppressive activity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:8445–67.10.2147/IJN.S223920Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Ebadi M, Buskaran K, Bullo S, Hussein MZ, Fakurazi S, Pastorin G. Drug delivery system based on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with (polyvinyl alcohol-zinc/aluminium-layered double hydroxide-sorafenib). Alex Eng J. 2021;60(1):733–47.10.1016/j.aej.2020.09.061Suche in Google Scholar

[75] Steinfeld B, Scott J, Vilander G, Marx L, Quirk M, Lindberg J, et al. The role of lean process improvement in implementation of evidence-based practices in behavioral health care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2015;42(4):504–18.10.1007/s11414-013-9386-3Suche in Google Scholar

[76] Fu K, Griebenow K, Hsieh L, Klibanov AM, Langer R. FTIR characterization of the secondary structure of proteins encapsulated within PLGA microspheres. J Control Rel. 1999;58(3):357–66.10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00192-8Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Mazumder S, Dewangan AK, Pavurala N. Enhanced dissolution of poorly soluble antiviral drugs from nanoparticles of cellulose acetate based solid dispersion matrices. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2017;12(6):532–41.10.1016/j.ajps.2017.07.002Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Kalepu S, Nekkanti V. Improved delivery of poorly soluble compounds using nanoparticle technology: a review. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2016;6(3):319–2.10.1007/s13346-016-0283-1Suche in Google Scholar

[79] Fernando I, Qian T, Zhou Y. Long term impact of surfactants & polymers on the colloidal stability, aggregation and dissolution of silver nanoparticles. Env Res. 2019;179(Pt A):108781.10.1016/j.envres.2019.108781Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Grossi F, Gridelli C, Aita M, De Marinis F. Identifying an optimum treatment strategy for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67(1):16–26.10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.12.002Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Furr BJ, Jordan VC. The pharmacology and clinical uses of tamoxifen. Pharmacol Ther. 1984;25(2):127–205.10.1016/0163-7258(84)90043-3Suche in Google Scholar

[82] Chen H, Tritton TR, Kenny N, Absher M, Chiu JF. Tamoxifen induces TGF-beta 1 activity and apoptosis of human MCF-7 breast cancer cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61(1):9–17.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960401)61:1<9::AID-JCB2>3.0.CO;2-ZSuche in Google Scholar

[83] Osborne CK, Boldt DH, Clark GM, Trent JM. Effects of tamoxifen on human breast cancer cell cycle kinetics: accumulation of cells in early G1 phase. Cancer Res. 1983;43(8):3583–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Zhang GJ, Kimijima I, Onda M, Kanno M, Sato H, Watanabe T, et al. Tamoxifen-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells relates to down-regulation of bcl-2, but not bax and bcl-X(L), without alteration of p53 protein levels. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(10):2971–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[85] Trindade AC, de Castro P, Pinto B, Ambrosio JAR, de Oliveira Junior BM, Beltrame Junior M, et al. Gelatin nanoparticles via template polymerization for drug delivery system to photoprocess application in cells. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2021;1–18. 10.1080/09205063.2021.1998819.Suche in Google Scholar

[86] Agnello L, Tortorella S, d’Argenio A, Carbone C, Camorani S, Locatelli E, et al. Optimizing cisplatin delivery to triple-negative breast cancer through novel EGFR aptamer-conjugated polymeric nanovectors. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):239.10.1186/s13046-021-02039-wSuche in Google Scholar

[87] Bonaccorso A, Pellitteri R, Ruozi B, Puglia C, Santonocito D, Pignatello R, et al. Curcumin Loaded Polymeric vs Lipid Nanoparticles: Antioxidant Effect on Normal and Hypoxic Olfactory Ensheathing Cells. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(1):159. 10.3390/nano11010159.Suche in Google Scholar

[88] Prochazka M, Granath F, Ekbom A, Shields PG, Hall P. Lung cancer risks in women with previous breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(11):1520–5.10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00089-8Suche in Google Scholar

[89] Jin L, Han B, Siegel E, Cui Y, Giuliano A, Cui X. Breast cancer lung metastasis: Molecular biology and therapeutic implications. Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19(10):858–68.10.1080/15384047.2018.1456599Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[90] Park SH, Wang X, Liu R, Lam KS, Weiss RH. High throughput screening of a small molecule one-bead-one-compound combinatorial library to identify attenuators of p21 as chemotherapy sensitizers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(12):2015–22.10.4161/cbt.7.12.7069Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, Zhang X, McNabola A, Wilkie D, et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66(24):11851–8.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Edwards K, Yao S, Pisano S, Feltracco V, Brusehafer K, Samanta S, et al. Hyaluronic Acid-Functionalized Nanomicelles Enhance SAHA Efficacy in 3D Endometrial Cancer Models. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(16).10.3390/cancers13164032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[93] Sheng X, Huang T, Qin J, Li Q, Wang W, Deng L, et al. Preparation, pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and antitumor effect of sorafenib-incorporating nanoparticles in vivo. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(5):6163–9.10.3892/ol.2017.6934Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[94] Baquero MT, Hanna JA, Neumeister V, Cheng H, Molinaro AM, Harris LN, et al. Stathmin expression and its relationship to microtubule-associated protein tau and outcome in breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(19):4660–9.10.1002/cncr.27453Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[95] Kang W, Tong JH, Chan AW, Lung RW, Chau SL, Wong QW, et al. Stathmin1 plays oncogenic role and is a target of microRNA-223 in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33919.10.1371/journal.pone.0033919Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[96] Long M, Yin G, Liu L, Lin F, Wang X, Ren J, et al. Adenovirus-mediated Aurora A shRNA driven by stathmin promoter suppressed tumor growth and enhanced paclitaxel chemotherapy sensitivity in human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19(4):271–81.10.1038/cgt.2011.89Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[97] Cazzalini O, Scovassi AI, Savio M, Stivala LA, Prosperi E. Multiple roles of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(CDKN1A) in the DNA damage response. Mutat Res. 2010;704(1–3):12–20.10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.01.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[98] Ruan S, Okcu MF, Ren JP, Chiao P, Andreeff M, Levin V, et al. Overexpressed WAF1/Cip1 renders glioblastoma cells resistant to chemotherapy agents 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea and cisplatin. Cancer Res. 1998;58(7):1538–43.Suche in Google Scholar

[99] Insinga A, Cicalese A, Faretta M, Gallo B, Albano L, Ronzoni S, et al. DNA damage in stem cells activates p21, inhibits p53, and induces symmetric self-renewing divisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(10):3931–6.10.1073/pnas.1213394110Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[100] Hsu CH, Altschuler SJ, Wu LF. Patterns of early p21 dynamics determine proliferation-senescence cell fate after chemotherapy. Cell. 2019;178(2):361–73 e12.10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[101] Jung YS, Qian Y, Chen X. Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity. Cell Signal. 2010;22(7):1003–12.10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[102] Olive PL, Banath JP. The comet assay: a method to measure DNA damage in individual cells. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(1):23–9.10.1038/nprot.2006.5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[103] Hosseinzadeh H, Younesi HM. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Crocus sativus L. stigma and petal extracts in mice. BMC Pharmacol. 2002;2:7.10.1186/1471-2210-2-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[104] Samarghandian S, Afshari JT, Davoodi S. Chrysin reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis in the human prostate cancer cell line pc-3. Clin (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(6):1073–9.10.1590/S1807-59322011000600026Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2022 Ahmed A. H. Abdellatif et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances