Abstract

Clathrate hydrates find diverse significant applications including but not limited to future energy resources, gas storage and transport, gas separation, water desalination, and refrigeration. Studies on the nucleation, growth, dissociation, and micro/nanoscale properties of clathrate hydrates that are of utmost importance for those applications are challenging by experiments but can be accessible by molecular simulations. By this method, however, identification of cage structures to extract useful insights is highly required. Herein, we introduce a hierarchical topology ring (HTR) algorithm to recognize cage structures with high efficiency and high accuracy. The HTR algorithm can identify all types of complete cages and is particularly optimized for hydrate identification in large-scale systems composed of millions of water molecules. Moreover, topological isomers of cages and n × guest@cage can be uniquely identified. Besides, we validate the use of HTR for the identification of cages of clathrate hydrates upon mechanical loads to failure.

1 Introduction

Clathrate hydrates are solid compounds composed of water and small molecules termed as guest molecules (such as methane, carbon dioxide, and so on), in which guest molecules are encased in solid cage-like water structures. According to conservative estimates, the energy, mainly methane, contained in the global accumulation of natural gas hydrate is twofold as that of currently recoverable fossil fuels [1] on the earth. Hydrates mainly occur in the deep-sea sediments, where high-pressure and low-temperature conditions facilitate their formation [2,3,4]. With the continuous maturity of technology, the mining of gas inclusion compounds has gradually become a hot topic, and these mineral resources are expected to become an important part of the energy supply in the world. Inclusion complex hydrates are also involved in various scientific fields such as the storage of greenhouse gases [5,6,7,8], the storage of energy gases [9], and the study of antifreeze protein principles [10,11,12]. Due to the important role of clathrate hydrates in a series of important scientific and technical issues in the field of energy, environment, and geological disaster prevention, the research of gas hydrates has become a lasting and important topic [1]. In addition, the formation of hydrates is likely to cause a series of problems such as pipeline blockage during natural gas transportation [13]; therefore, further research on the thermal and mechanical aspects of clathrate hydrates is of essential importance.

Currently, the researches of clathrate hydrate are mainly carried out through experiments and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. In the research on the nucleation and mechanical properties of clathrate hydrates, it is not easily accessible to obtain molecular information on the nanometer length scale and microsecond time scale through experimental methods. With the aid of computational modeling, some phenomena that cannot be observed in experiments may be discovered [14]. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct clathrate hydrate research by MD simulations [15]. Debenedetti and Sarupria [16] realized the spontaneous nucleation of hydrates by MD, and it is inspired by the use of MD methods to study the nucleation and growth of hydrates, making the MD simulation popular in the study of clathrate hydrate [17,18,19,20]. In addition, although great efforts have been made in hydrate nucleation, the path is not clear, and nucleation seems to occur through multiple competitive paths to varying degrees [21]. Consequently, it is essential to recognize the cage structure form in the MD trajectories to extract useful insights. As a result, there have been several cage recognition algorithms proposed. For instance, Jacobson et al. [8] connected particles by identifying rings by treating water as vertices in an undirected graph. After determining the relationship between rings, the algorithm searches a five-element ring, which connects five other pentagonal rings at each edge. This structure is a half dodecahedral cage, which is called a “cup.” A complete dodecahedral cage was obtained by merging these cups. Guo et al. [22,23] designed an algorithm called face-saturated incomplete cage analysis (FSICA) and identified 1,258 complete cages and 7,015 face-saturated incomplete cages (FSICs). The recognition accuracy of FSICA is quite high, and FSICA can recognize the surface-unsaturated cage, which cannot be achieved by other algorithms. Nguyen and Molinero [24] designed the CHILL + algorithm that uses staggered and overlapping water bond numbers to identify water molecules in ice and clathrate hydrates. Mahmoudinobar and Dias [25] presented the GRADE algorithm to identify the hydrates of the 512 and 51262 cage structures through the combination of the upper and lower cup-shaped half cages or the combination of four cup-shaped cages to identify the 51264 structure. Recently, Hao et al. [26] proposed the iterative cup overlap (ICO) algorithm, which can identify hydrate cages by combining multiple semicage structures. However, it still remains deficiencies for these algorithms yet, such as fewer types of recognizable cages, low recognition efficiency, and inability to accurately recognize deformed cages.

To address these issues, we proposed the HTR algorithm. The HTR algorithm is written in Java that can identify any type of water cage. Its advantage is that it has excellent cross-platform performance while maintaining high-speed code execution. The compiled “.class” file package can be run directly on all platforms where the Java virtual machine is installed without repeated compilation. By comparing with other algorithms, HTR shows higher efficiency advantages on the basis of accurate identification, particularly for large systems composed of hundreds of thousands or even tens of millions of water molecules. In addition, HTR only requires the least hardware cost in the identification process because it does not need to read the atomic information in the entire system into the memory at one time when identifying the cage structure for a larger hydrate system.

2 Algorithm

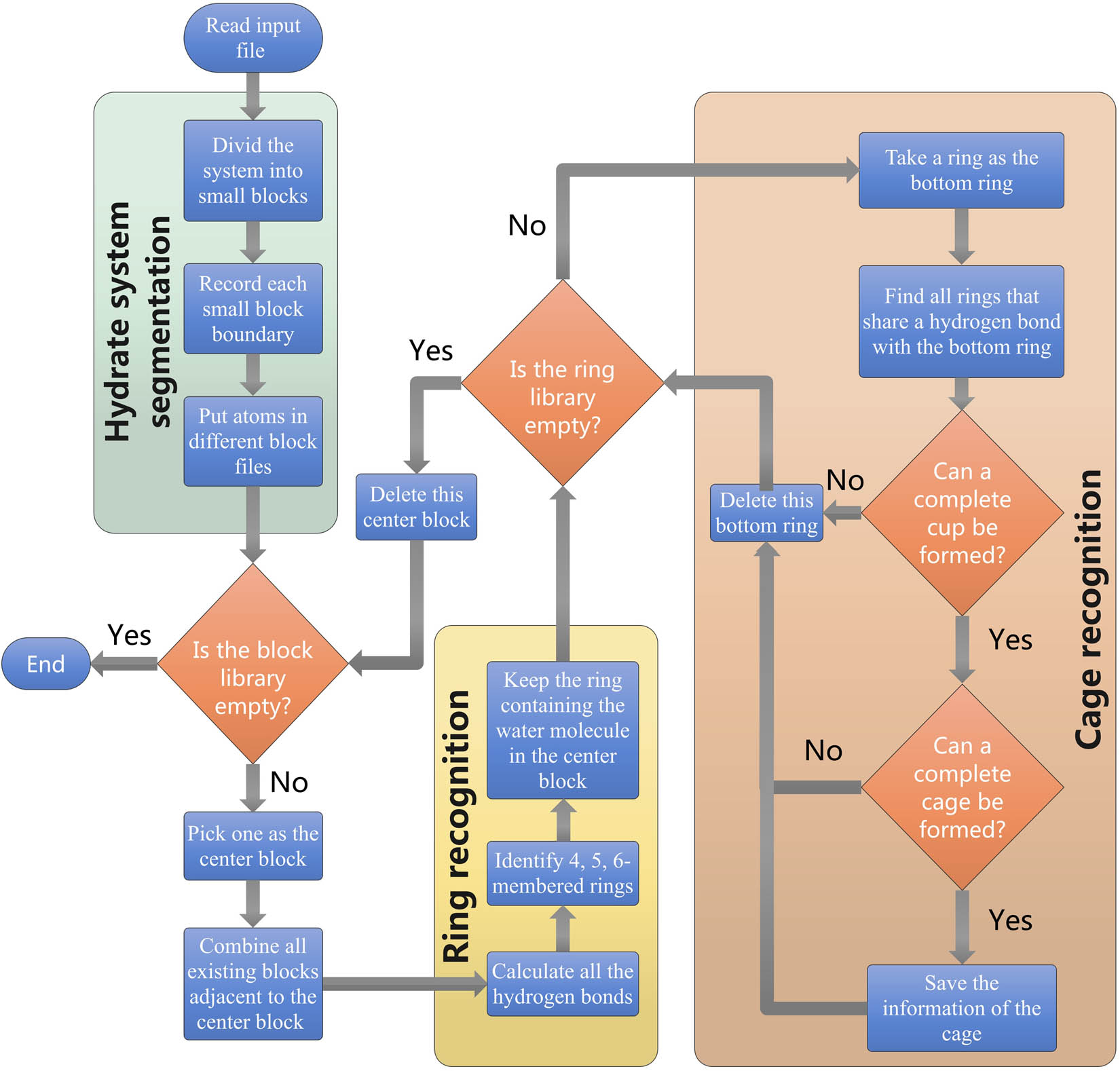

To improve the maintainability of the program and reduce the degree of coupling between functions, the HTR algorithm divides the hydrate identification into three steps, including (i) the segmentation of the clathrate hydrate system, (ii) the identification of the rings through the water molecule, and (iii) the identification of the cages through the identified ring (refer to Figure 1 for more details).

General flow chart of HTR. The algorithm is mainly divided into three processes: (i) hydrate system segmentation, (ii) ring recognition, and (iii) cage recognition.

2.1 Identification of the rings

The ring recognition algorithm by the GRADE [25] is on the basis of the breadth-first search (BFS) method, which should be the most accurate method for ring recognition at present. However, the problem brought by this method is that it will identify many severely deformed rings. GRADE filters out severely deformed rings because they seldom form a cage, and only identifies the relatively stable cages of 512, 51262, and 51264. At the same time, a phenomenon was discovered in our study of the structure of hydrate cages, that is, severely deformed rings usually appear in some unconventional cages. Therefore, filtering out this part of the rings will inevitably reduce the accuracy of recognition. Moreover, these unconventional cages are of great importance in the studies of clathrate hydrate nucleation and thermodynamic properties. After referring to the various ring deformation conditions proposed by Matsumoto et al. [27], HTR retains all deformed rings when calculating cages to ensure the accuracy of identifying unconventional cages. According to the current general judgment conditions for hydrogen bond formation, HTR uses a cutoff of 3.5 Å and ∠HOO at 45° as the hydrogen bond formation conditions. The reason for setting the hydrogen bond judgment condition is that Laage and Hynes [28] proposed that the cutoff should not be greater than 4.0 Å and the bond angle should be less than 50°, and GRADE [25] also adopted this set of parameters. Using 45° as the bond angle can minimize the inaccurate identification caused by the serious deformation of the cage in the process of hydrate nucleation. The cage identification is based on the MD simulations with coarse-grained model of water, where the bond length is determined only by the distance [29,30].

In this study, the hydrate cage studied mainly contains two characteristics, one of which is that the cage only contains four-, five-, and six-membered rings, and the other is that the cage is surface saturated, as shown in Figure 1. Regardless of the type of clathrate hydrate, it usually contains only four-, five-, and six-membered rings.

2.2 Identification of the cages

The process of HTR recognition of cages can be mainly divided into two parts: (i) the recognition of the cup-shaped half-cage structure and (ii) the topology of rings. Jacobson et al. [8] defined a cup as a half-cage composed of five-membered and six-membered rings sharing some hydrogen bonds. Since the HTR algorithm needs to identify all types of cages, the four-membered ring is also included in the definition of the cup.

2.2.1 Recognition of the cup

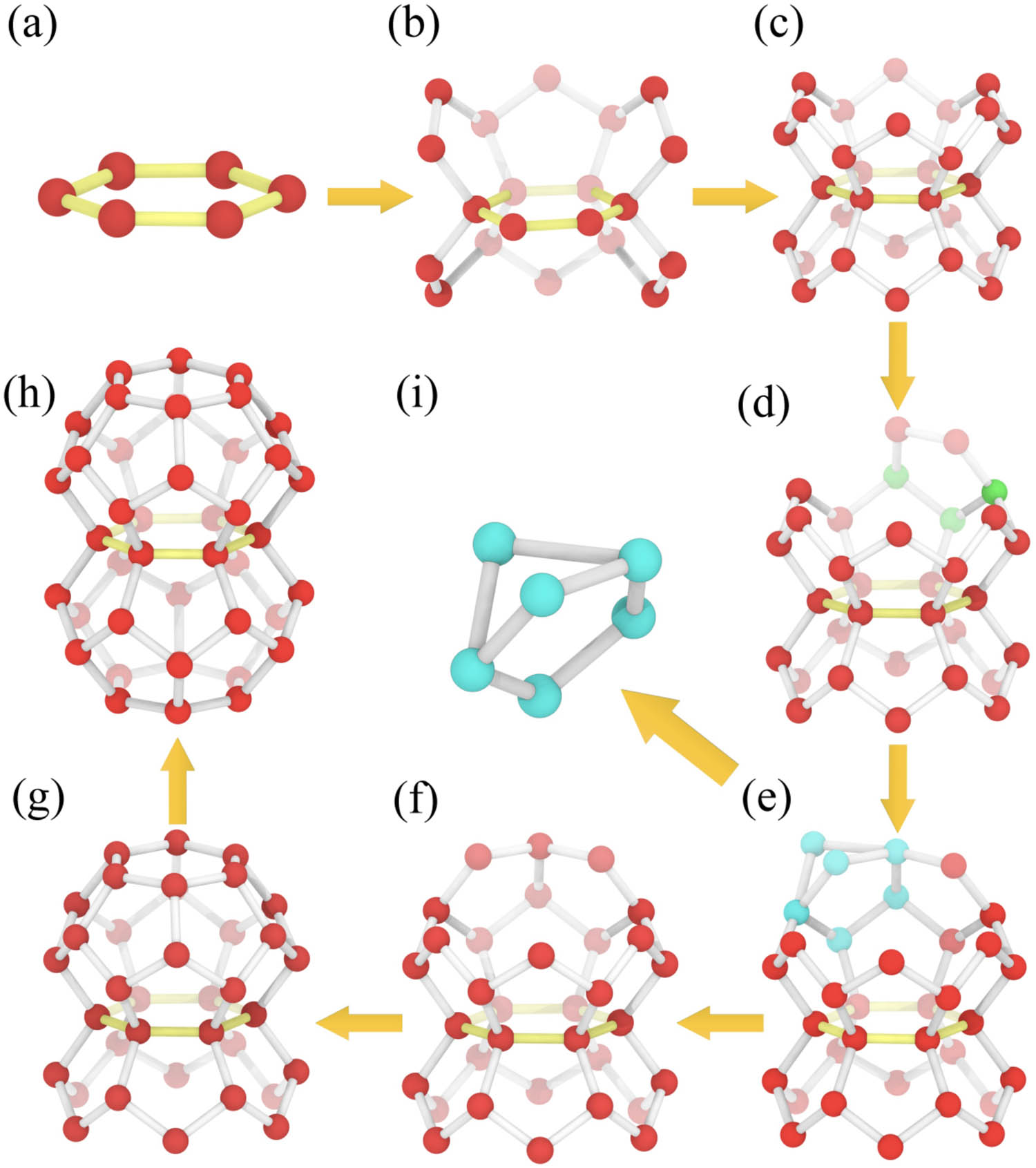

According to the order in which the rings are stored in the memory, each ring must be used as a bottom ring (Figure 2a). After selecting a certain ring as the bottom ring, the ring library that shares a hydrogen bond with the bottom ring is generated. All the rings can identify the upper and lower cups that share the same ring (Figure 2c).

Scheme of HTR algorithm. Choosing a ring (a) as the bottom ring, we can find all the rings that share a hydrogen bond with this ring. Through the process (b), the algorithm can find all the rings that share a hydrogen bond with this ring and obtain the two half-cage structures that share the same ring in (c). Select one of the half cages for the topology of rings, and the three green water molecules at the edge of the upper half of the cage in (d) can generally be located in the unique ring from the identified ring library. Repeat the ring topology process, and if the cage cannot be closed, go back to step (e) to use another ring for topology. If the cage is closed, as shown in (g), repeat the aforementioned topological process for the lower half of the cage and finally get a double-cage structure sharing a ring in (h). If the two rings in (i) share more than three water molecules, the HTR algorithm will first select one of the rings to obtain the structure (f) and then proceed to the next topology.

2.2.2 Topology of the ring

From the geometrical perspective, two straight lines that intersect at one point can uniquely determine a plane, and similarly, it can be uniquely positioned to a ring through two hydrogen bonds formed by three adjacent water molecules. When this happens, the HTR algorithm will first use one of the rings to perform topology calculations (Figure 2f). If the current ring cannot be topped with a complete cage, it will switch to another ring to perform the topology again. After repeating the aforementioned ring topology process, when the cage is finally closed (Figure 2g), the HTR then determined that the identification of the cage is completed, otherwise it is considered that it is not a complete cage. Then, the aforementioned topological process for the lower cup is repeated, and one can get the structure of two cages sharing a ring, as shown in Figure 2h. At this point, the bottom ring has completed its mission and will no longer appear in other cages (because a ring can only belong to two cages at most).

The hydrate cage is a polyhedral structure, and the contact surface of two convex polyhedral cages is a ring. Since a cage contains multiple rings, the selection of different rings on the same cage as the bottom ring for cage topology will surely find the same cage. To ensure that the same cage will not be identified repeatedly, a very clever algorithm to prevent misidentification has been added to the HTR. In Figure 3, as the left and middle cages are identified by the left yellow ring, the yellow ring is shielded from the ring library. When the middle cage is identified by the red ring on the right, the yellow ring on the left can no longer be obtained, thereby the cage is deemed incomplete and the problem of the repeated identification is avoided.

Mechanisms of HTR algorithm to prevent duplicate identification. The yellow ring is at the intersection of two adjacent cages. When the middle cage is recognized by the yellow ring on the left, it can no longer be recognized by the yellow ring on the right.

2.3 Acceleration of HTR algorithm

After referring to the previous hydrate cage identification algorithms, a common feature can be summarized, that is, hydrates in large systems cannot be effectively identified, especially for the MD trajectories with a large number of frames and water molecules. The efficiency issue of large-scale system recognition is that the recognition of each cage needs to traverse the spatial coordinates of all water molecules to determine which are adjacent water molecules. This means that when a larger system is presented, more particles are needed to be traversed to identify a cage. Therefore, a power or exponential relationship between the number of particles and time is shown, which means that it will be very hard to recognize the cage structures for large systems.

To solve this issue, HTR divides the system into multiple blocks, identifies the cage structures separately, and hence greatly improves the recognition efficiency. As illustrated in Figure 4, a clathrate hydrate system is divided into 4

Cross-sectional view of segmentation of the clathrate hydrate system by HTR algorithm. Adjacent blocks are distinguished by different colors. The water molecules of different colors in the partially enlarged view come from the blocks adjacent to the central green block.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 High efficiency of HTR on cage recognition of clathrate hydrate

According to the algorithm section, when HTR running on the green subblock in Figure 4, the time to identify all the rings in the block is t r, and the time to identify all the cages in the small block through the rings is t c. Then, the recognition time of the rings of the 27 subblocks centered on the green block is 27t r, and the recognition time of the cages is t c (only cages in the green block are recognized). The total cost time on the green subblock is 27t r + t c. Assuming that the hydrate system is divided into n blocks, the total identification time will be n(27t r + t c). The recognition time of the entire system can be accurately predicted only by the number of subblocks and the recognition time of a subblock. A perfect 5 × 8 × 10 supercell of sI-type clathrate hydrate system was selected for testing, which is shown in Figure 5.

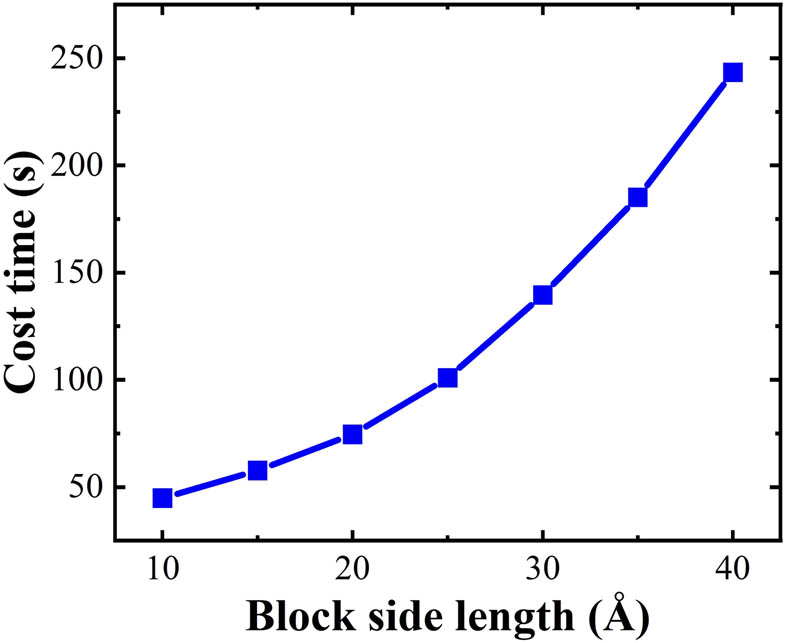

Cage recognition cost time by HTR algorithm as a function of block size (system: 5 × 8 × 10 sI-type clathrate hydrate, 18,400 water molecules).

Figure 5 shows that there is a strong relationship between the block size and the cost time on cage recognition for the clathrate hydrate system by HTR. After try-error tests, a subblock size of 12 Å was chosen. The numbers of 512 and 51262 cages in a 5 × 8 × 10 supercell of sI-type clathrate hydrate system are recognized to be 8,000 and 24,000, respectively, verifying the accuracy of the HTR algorithm.

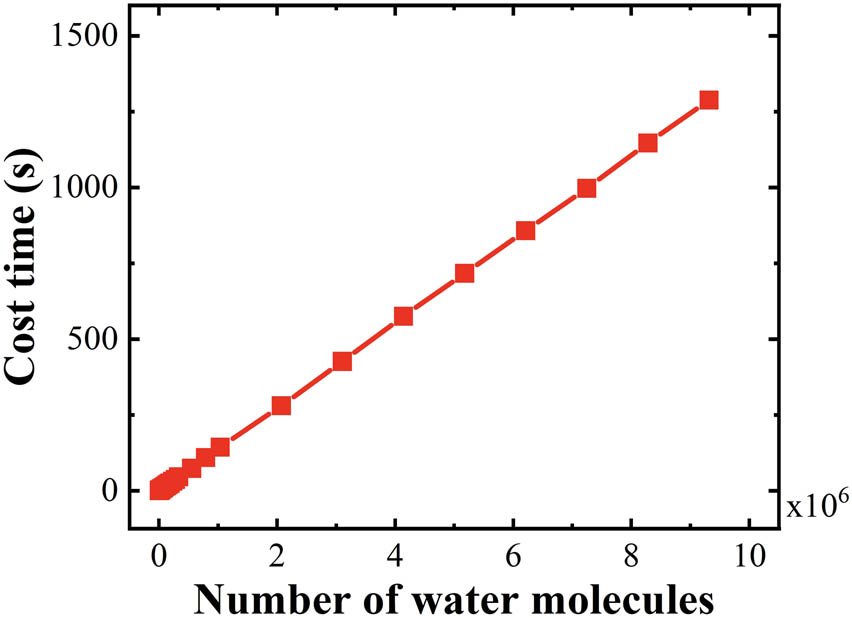

To verify the recognition efficiency of the HTR algorithm, the sI-type clathrate hydrate systems with different dimensions were identified. The cost time of each system as a function of water molecules was plotted in Figure 6, which is approximately linear with a slope of 1.38 × 10−4. The HTR algorithm exhibits an extremely high efficiency and linear advantages for the cage identification of clathrate hydrate large systems. Here, the computer configuration parameters are as follows: operating system: Ubuntu 18.04.5 LTS; hardware architecture: ×86_64; Kernel: Linux 5.4.0-81-generic; CPU: Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6128 CPU@3.40 GHz 6 cores; memory: 32 G.

Cost time of cage recognition by HTR as a function of water molecules in sI-type clathrate hydrate systems.

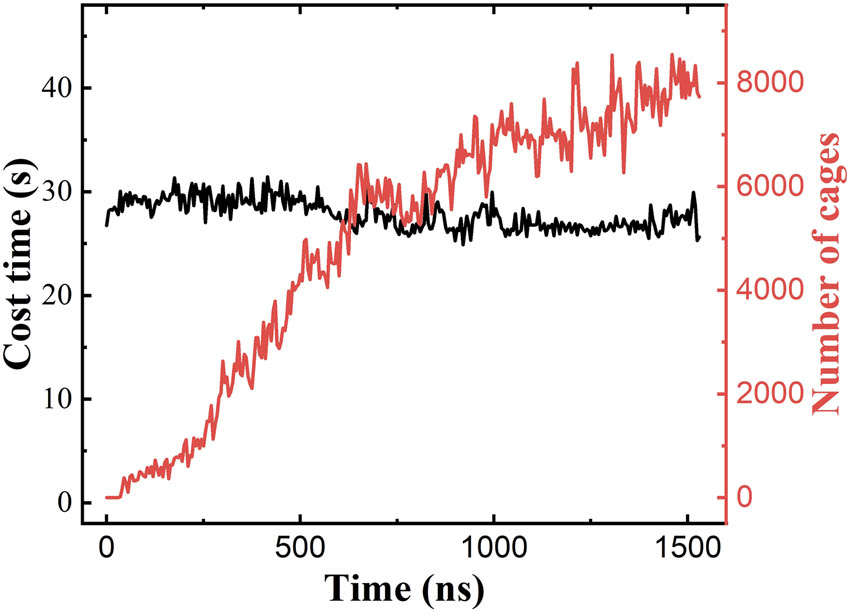

In the research area of clathrate hydrates, nucleation and growth are important research topics. HTR algorithm was first applied to the nucleation and growth process of clathrate hydrates. Figure 7 shows the variation in the number of cages recognized by HTR with the MD simulation time in a homogeneous nucleation process of methane hydrate systems at a temperature of 250 K and confining pressure of 500 bar, in which the simulation system is composed of 1,242 water molecules and 216 methane molecules. As is indicated, the cage recognition speed by HTR is very efficient, that is, the recognition time of each frame of MD trajectory is in the millisecond level. To be rigorous, the simulation system was expanded to be 5 × 6 × 6 times for the cage recognition by HTR algorithm. It is tested that the cost time for cage recognition does not change with the cage numbers, suggesting that the system size (the number of water molecules) is the only factor for the computational efficiency of HTR algorithm.

Cost time (black) and number of cages (red) by HTR algorithm along with the simulation time of clathrate hydrate nucleation.

It is summarized from Figure 7 that HTR is able to accurately predict the time required for cage recognition as the input files are different. Table 1 lists the cost time of cage recognition for a similar system by HTR, as well as literature-reported FSICA [22], GRADE [25], and ICO [26] algorithms. Note that the MD trajectory with 50 frames is shared by FSICA, GRADE, and ICO for cage recognition. The information data such as the time required for cage recognition and the number of cages are provided by Hao et al. and Zhang et al. Because we are not able to have the same MD trajectory and the FSICA, GRADE, and ICO source codes, a system with similar molecular composition and 50-frame MD trajectories was achieved by us for the comparison test of the performance of HTR. The number of water molecules in the system by HTR is 3,726, while the number of water molecules in the system by FSICA, GRADE, and ICO algorithms is 3,487. It is found that the time consumed to identify cage recognition by HTR is not sensitive to the number of cages in the system.

In a hydrate system with basically the same number of water molecules, the comparison of the time is required for the four algorithms to identify. Among them, HTR is the data of this work, and the other three sets of data are from other articles

| Algorithm | Total cages | Cost time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| HTR | 15,724 | 26 |

| FSICA | 13,691 | 16,480 [26] |

| ICO | 13,695 | 691 [31] |

| GRADE | 4,410 | 449 [31] |

As indicated by Table 1, HTR shows dozens of times higher efficiency in the cage recognition for small systems than FSICA, GRADE, and ICO, although it shows high efficiency in the cage recognition for large systems that are challenging for FSICA, GRADE, and ICO. It is worth noting that HTR and other algorithms (FSICA, GRADE, and ICO) do not use the same MD trajectory. The issues of recognition accuracy and identifiable cage types will be discussed further in the following section.

3.2 Accuracy of HTR algorithm on cage recognition of clathrate hydrate

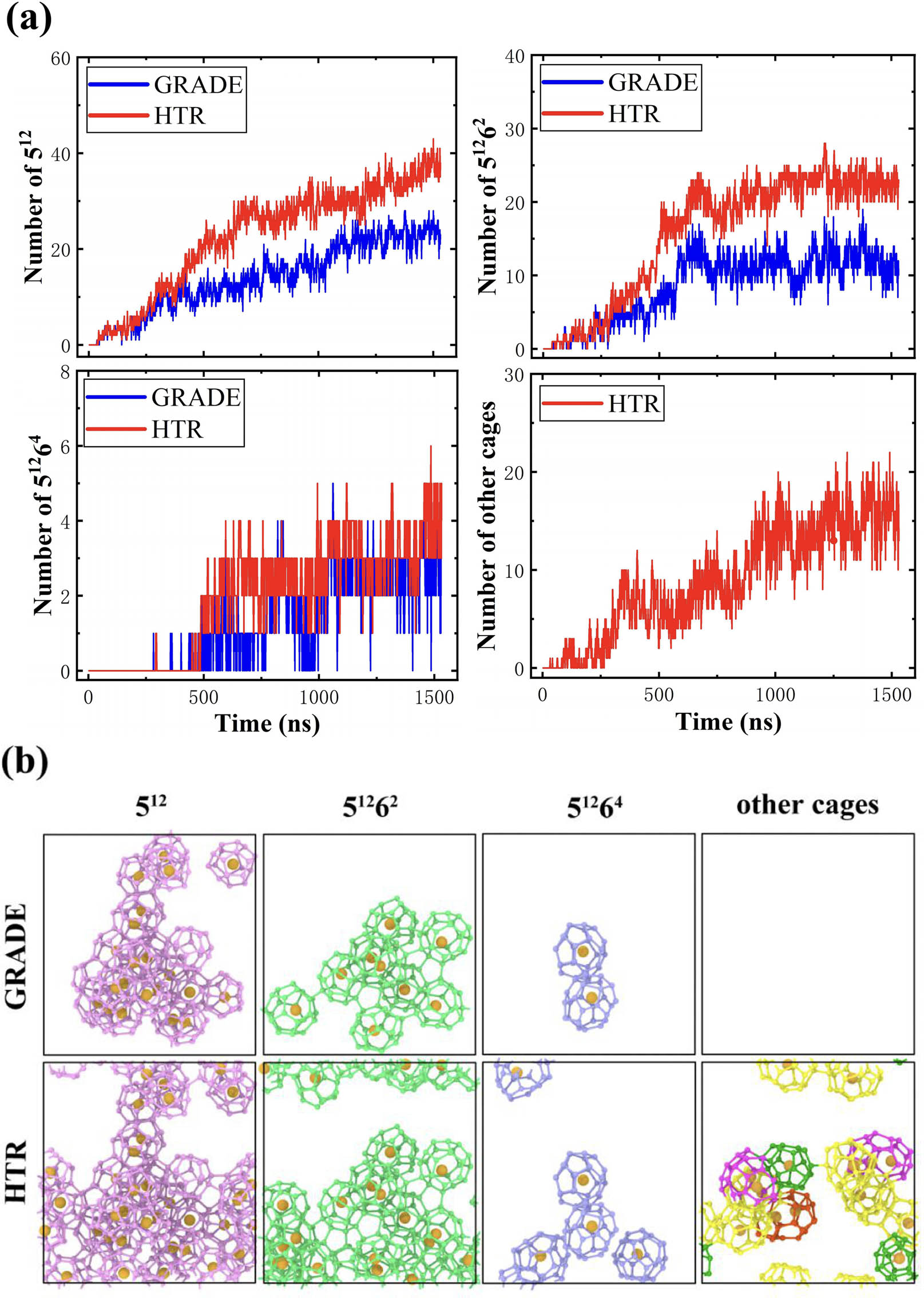

To verify the accuracy of cage recognition by HTR, the hydrate nucleation simulation system composed of 1,242 water molecules and 216 methane molecules was used for HTR and GRADE to analyze the simulation trajectory with 1,000 ns. HTR was evaluated by comparing the results of cage recognition with GRADE. As is known, the performance of GRADE on cage recognition also depends on the setting of filter conditions δ1 and δ2. To ensure the accuracy of recognition, δ1 and δ2 are set to be 3 Å [8]. Figure 8a compares the variation in the numbers of 512, 51262, 51264, and other cages identified by HTR and GRADE with MD simulation time. For GRADE, there is no curve for “other cages” because GRADE only recognizes three types of cages including 512, 51262, and 51264. However, HTR recognizes more types of cages, that is, besides the common 512, 51262, and 51264 cages, there are other cages that can be identified by HTR.

(a) Numbers of 512, 51262, 51264, and other cages identified by the HTR algorithm and the GRADE algorithm in the entire trajectory. (b) A snapshot of each cage identified by HTR and GRADE at 1,000 ns.

To check whether there is over recognition of cages by HTR, the snapshots of cages recognized by HTR and GRADE are captured in Figure 8. Apparently, it can be seen that all the cages identified by GRADE can be also identified by HTR. However, there are more cages that are recognized by HTR. This is because GRADE does not consider the periodic boundary conditions and thereby is not able to identify the cages across the boundaries of the simulation box, while HTR recognizes the cages across the boundaries. This also further verifies the accuracy of HTR recognition.

3.3 Application of HTR algorithm in nucleation and micro/nanomechanics of clathrate hydrate

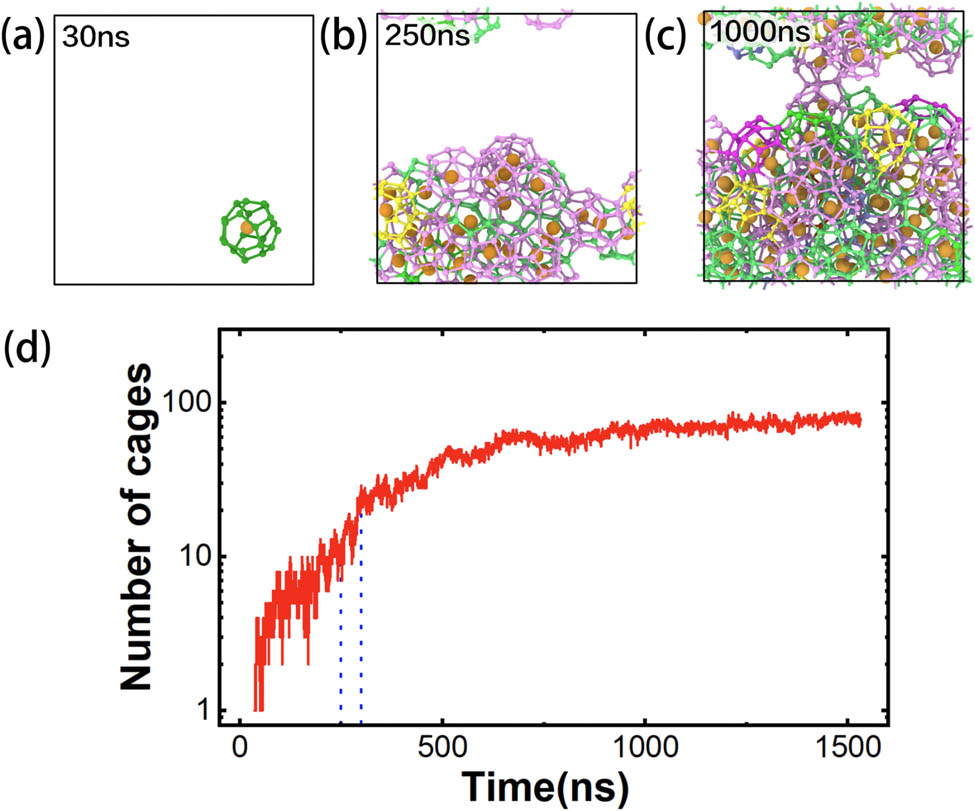

Figure 9 shows the snapshots of cage structures recognized by HTR for a methane hydrate nucleation system. As shown in Figure 9a, a 4151062 cage appeared at 30 ns and disappeared within a short simulation time due to the fluctuation of the system before the nucleation process. The number of cages gradually increases along with the simulation time. At about 250–300 ns, the fluctuation in the number of newly formed cages decreased rapidly and plateaued (Figure 9d), indicating that the nucleation process has been completed. After the simulation of 500 ns, the number of cages reached a plateau (Figure 9d) due to the fact that nearly all the space of the system were occupied by the cages (Figure 9c). It is noticed that the unconventional cages of hydrate appeared throughout the trajectory, especially for the period of 250–300 ns (shown in Figure 8a), where the number of newly formed unconventional cages increased significantly. These results suggest that the unconventional cages are closely related to the nucleation process of hydrate, which is consistent with the previous report: the nucleation/growth path can be well predicted according to some unconventional cage structures [32]. It should be pointed out that due to the complexity of the hydrate nucleation mechanism, one cannot draw a clear conclusion about the nucleation of hydrate based on such a simple test. While, despite the importance of the unconventional cages on hydrate nucleation, there is no effective algorithm for the recognition of unconventional cages. Thus, the HTR algorithm can provide crucial data for the nucleation mechanism study of hydrate.

(a)–(c) snapshots at different times during the nucleation of clathrate hydrate. The different types of cage recognized by the HTR algorithm are represented by different colors: light green, pink, Roland purple, and other colors for 512, 51262, 51264, and other types of cages, respectively. (d) Number of newly formed cages in the system along with time.

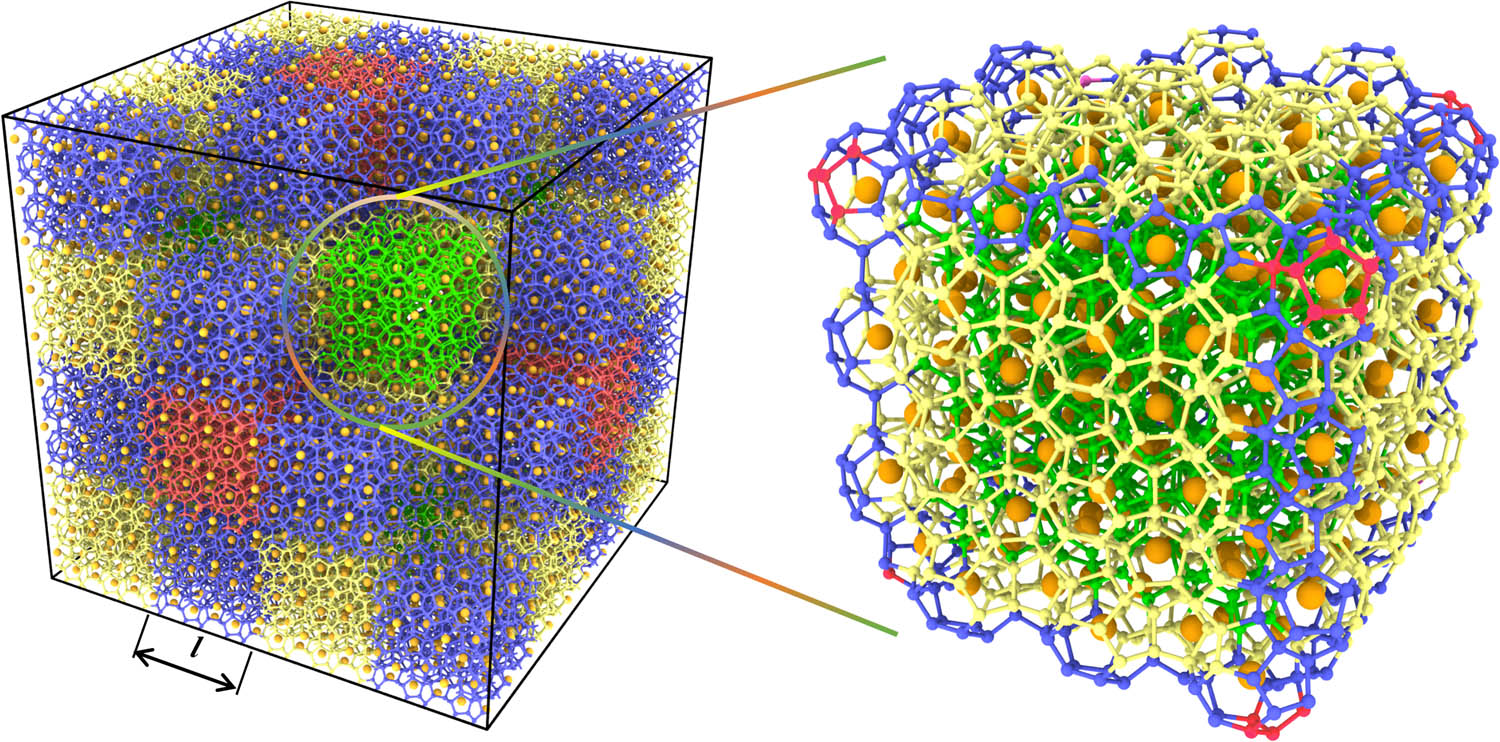

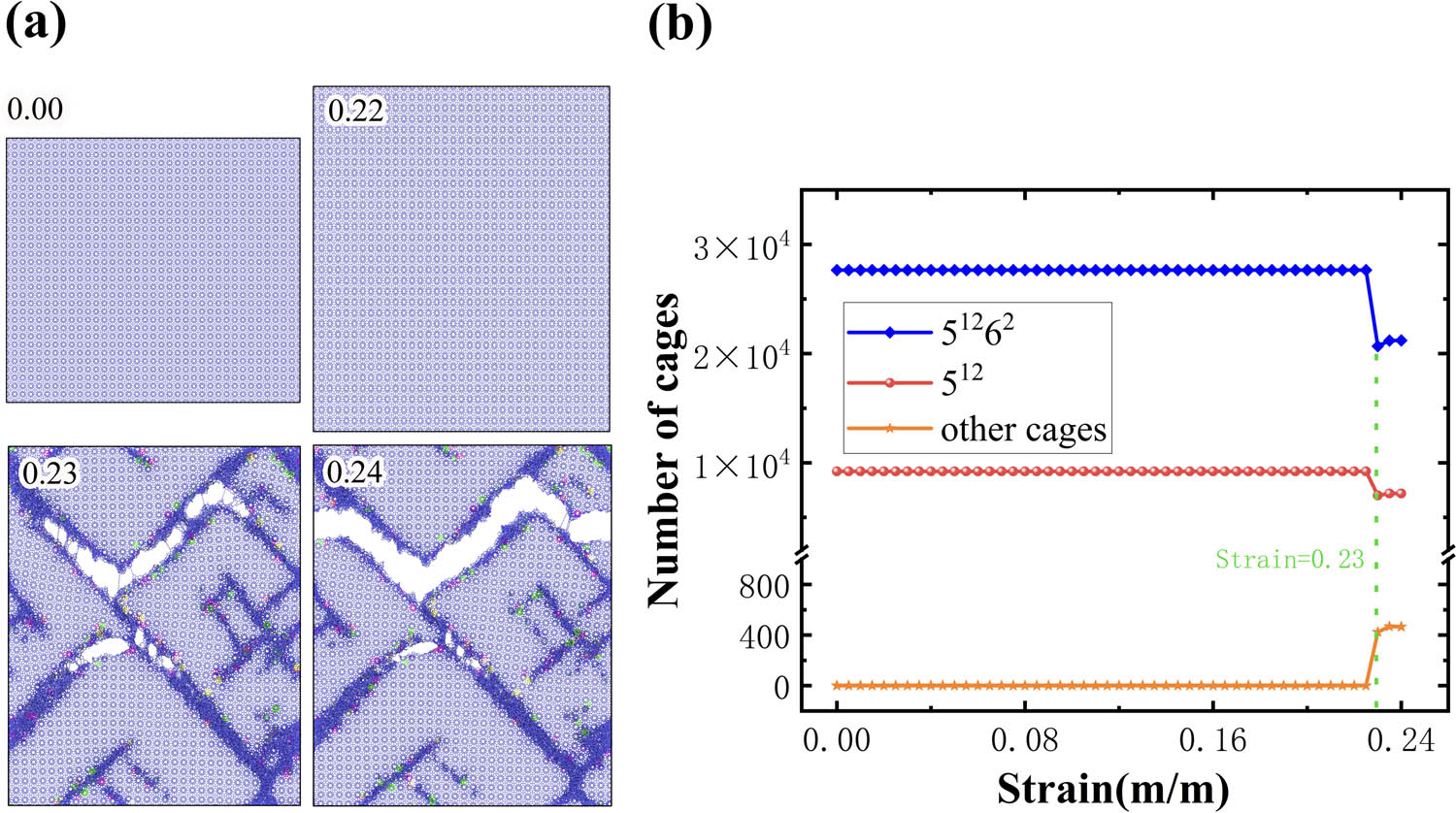

Micro/nanomechanics is another hot research topic in the study of the clathrate hydrate system. To expand the scope of the application of HTR, cage recognition of mechanically deformed sI methane hydrate system with dimensions of ∼46.5 Å3 × 418.8 Å3 × 374.6 Å3, containing 36,864 methane molecules and 211,968 water molecules, was performed. Figure 10a shows the side views of the system at four uniaxial strains of 0.00, 0.22, 0.23, and 0.24. As the uniaxial strain is imposed from 0.00 to 0.22, the methane hydrate underwent elastic deformation. As a result, there is no dissociation of 512 and 51262 cages. In this deformational stage, both 512 and 51262 cages in the system are deformed. As indicated by Figure 10b, although they are mechanically deformed, they can be identified by HTR. For example, the number of 512 and 51262 cages identified by HTR before failure (strain varying from 0.00 to 0.22) remains to be 9,216 and 27,648, indicating that HTR can be applied to recognize highly deformed clathrate cages, which is of importance in the application of micro/nanomechanics study of clathrate hydrate. As the strain is applied to around 0.23, the methane hydrate fails via brittle cracks in the crystal. The brittle cracks can be characterized by local dissociation by both 512 and 51262 cages in the system, which is explained by the sudden drop in the number of 512 and 51262 cages, as illustrated in Figure 10b. Intriguingly, other types of clathrate cages form at the crack boundaries, which can be indicated by Figure 10a and b. (In Figure 10a, blue indicates 512 and 51262 cages, and other different colors indicate different types of newly generated cages.) As the uniaxial strain is imposed to 0.24, the system tends to be stable because the number of all kinds of clathrate cages remains constant.

(a) Snapshots of strains ε = 0.00, 0.22, 0.23, and 0.24 of the sI-type clathrate hydrate system (with 211,968 water molecules). (b) Number of different cages identified by the HTR algorithm as a function of strains.

3.4 Recognition of special cage structures in clathrate hydrate by HTR algorithm

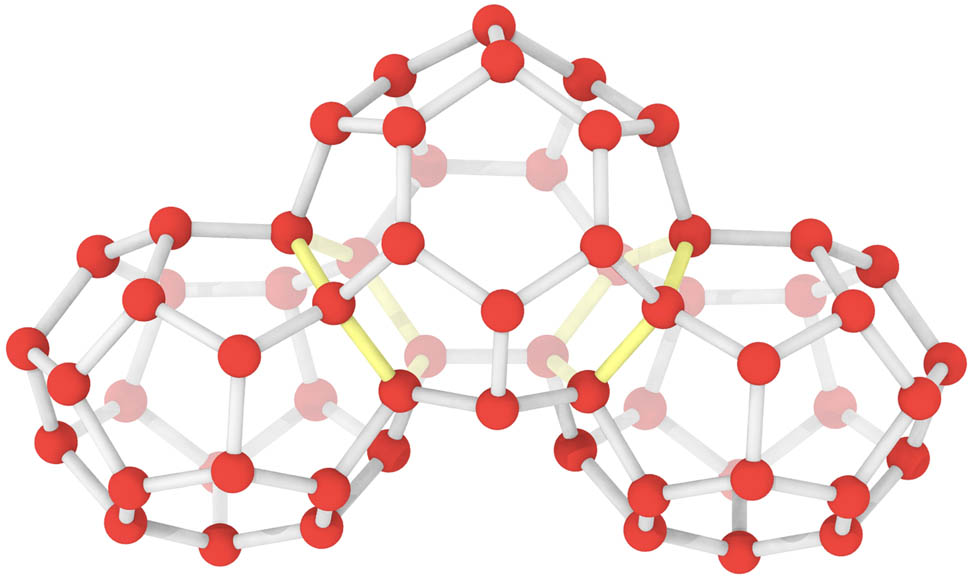

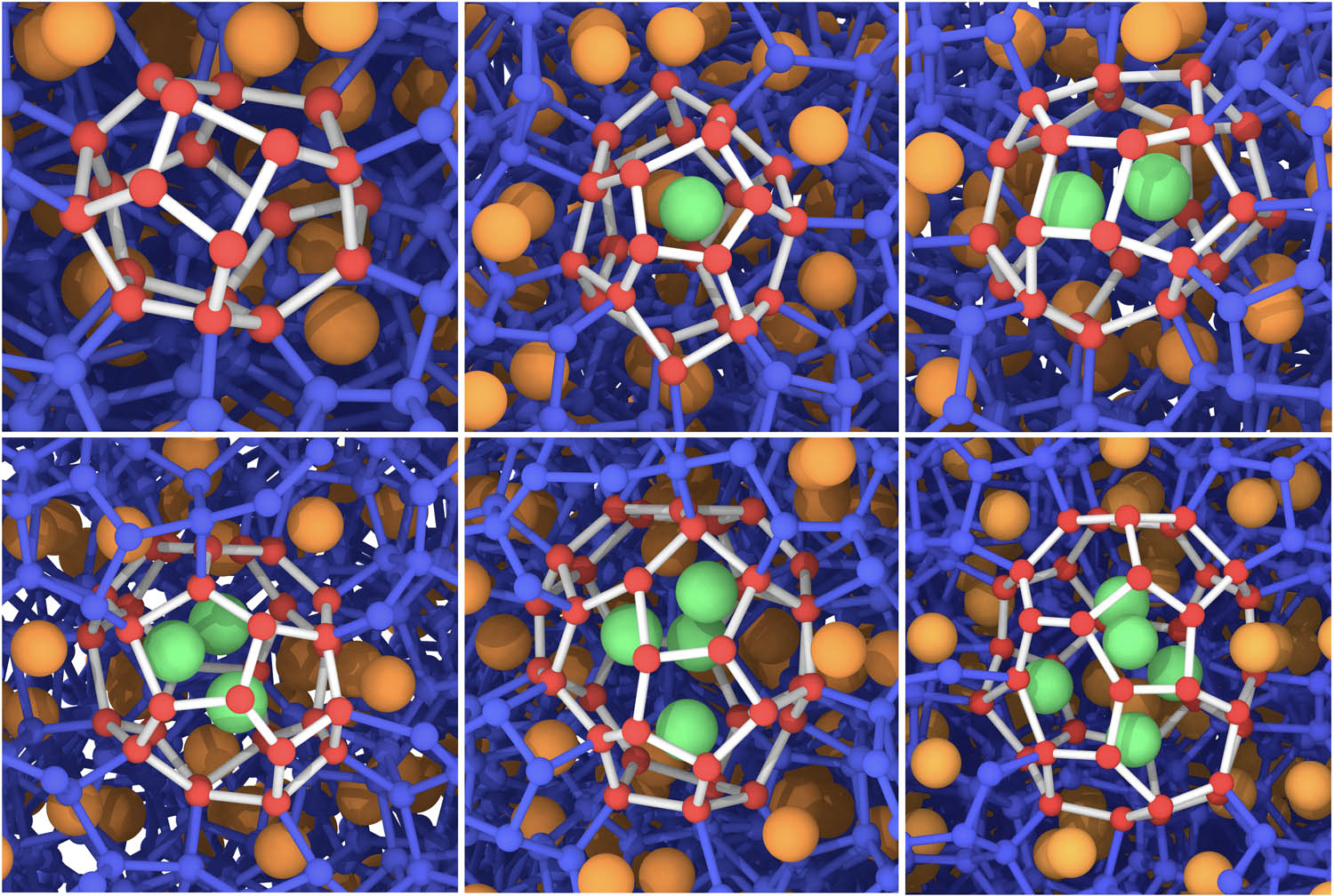

The movement and distribution of guest molecules in clathrate cages play a vital role in the study of thermodynamics of clathrate hydrates. For example, Liang et al. [33] revealed the jumping mechanism of CO2 hydrate near the dissociation temperature (310–320 K at 100 MPa) by MD simulations. Lo et al. [34] discovered the migration of guest molecules from one cage to another at a much lower temperature under melting conditions. Lu et al. [35] studied the behavior of guest molecules in the nucleation and growth of CO2 hydrate in the presence of soluble ionic organic matter. To address this topic, HTR also integrates the function of tracking and locating the guest molecules, by calculating the center of mass (CoM) coordinates of each cage and searching for guest molecules in a sphere centered on the CoM of each cage. With this function, HTR can identify cages encapsulate none or multiple guest molecules. Here, a sI-type polycrystalline methane hydrate composed of 314,664 coarse-grained water molecules was generated to test this function. As illustrated by Figure 11, one clathrate hydrate cage at the grain boundaries of a polycrystal is able to encapsulate different numbers of guest molecules (from 0 to 5). Note that multiple guest molecules@cage is instantaneously captured, and it is a metastable structure.

Snapshots from empty cages to quadruple-occupied cages in clathrate hydrate systems.

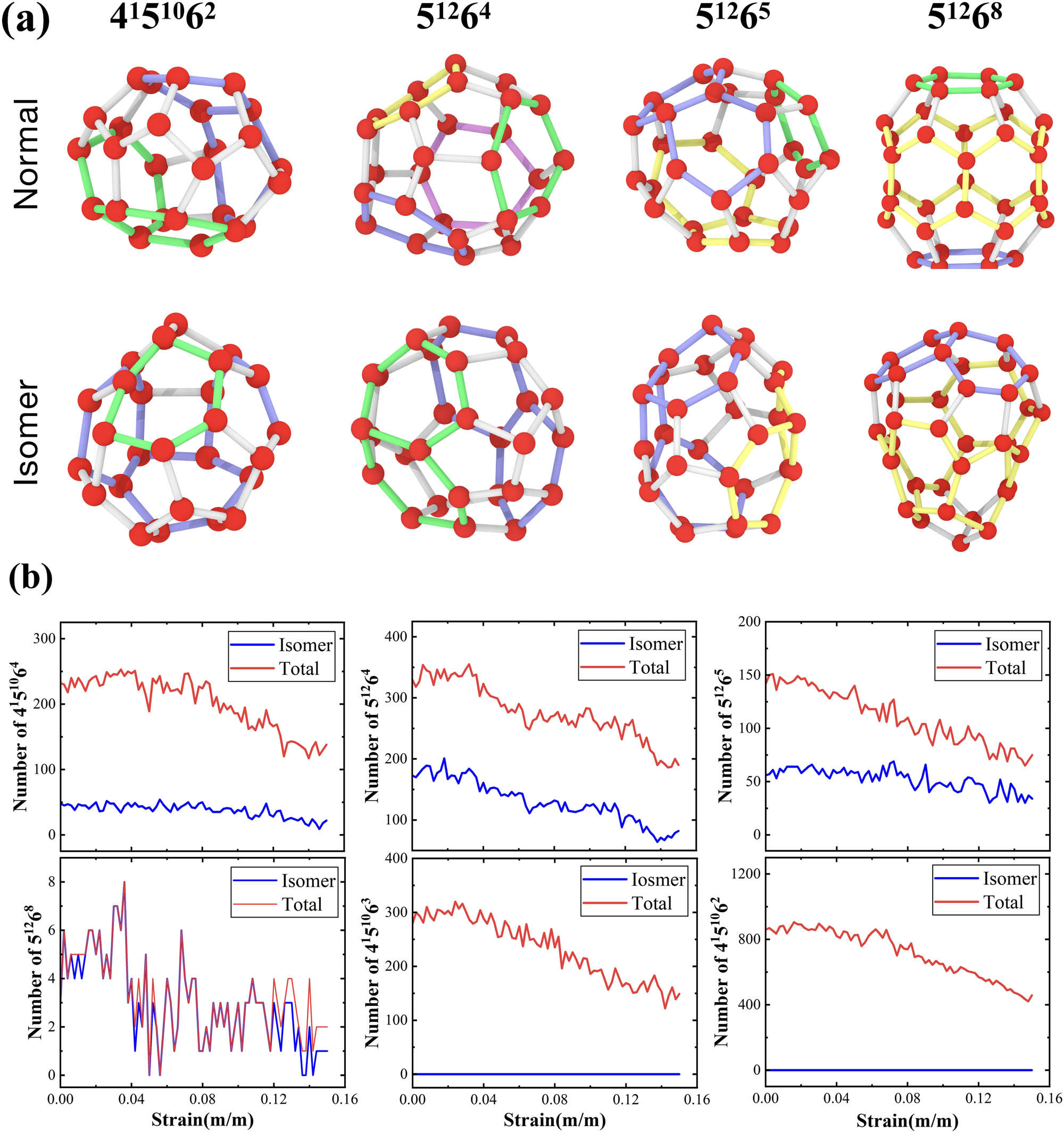

Another integrated function in HTR is the recognition of isomers cages. Commonly, the naming of one clathrate hydrate cage is defined according to the number of four-, five-, and six-membered rings in the cage, while the topology of the rings is ignored. From the topological perspective, a cage shows several possible arrangements of four-, five-, and six-membered rings, although it is composed of a specific number of polygonal rings. As such, a cage with identical polygonal compositions but different topology is termed as topological isomers of the cage. In HTR, the arrangement of the rings neighboring the four- and six-membered rings is the key to recognize isomers. Since HTR recognizes cages based on the topology of the ring, the arrangement of the rings around each ring can be easily determined, and thereby isomers of cages can be identified. In this study, the aforementioned large-scale polycrystalline methane hydrate sample subjected to uniaxial tension was employed to explore the isomers of the clathrate cage. As is known for 512 cage, there is no isomer of the clathrate cage due to the fact that it is only composed of five-membered rings.

Figure 12a shows the topological isomers of several clathrate cages (4151064, 51264, 51265, and 51268) identified from the deforming polycrystalline sample. For clarification of topological isomers in the cages, the six-membered rings are highlighted, and the two adjacent six-membered rings that share a hydrogen bond are identically colored. Apparently, for each type of the aforementioned clathrate cages, there are topological isomers. Figure 12b shows the variations in the total number of cages and the number of isomers of cages in the polycrystalline system subjected to uniaxial strain. Apparently, there is a reduction tendency in the total number of all types of clathrate cages. For the case of the isomers of cages, there is a negligible change in the number of topological isomers of 4151064 and 51268 clathrate cages, while the number of topological isomers of 51264 and 51265 clathrate cage is changeable with uniaxial strain, and the change range of the number of isomers of 51265 is small. However, it is identified that there are no topological isomers of 4151062 and 4151063 clathrate cages. By comparing with the conventional cages, the topological isomers of 51268 clathrate cages are predominated, while the topological isomers of 4151064 clathrate cages are the least.

HTR identified isomer cages in the polycrystalline stretching process of a system of 314,664 water molecules. (a) The colored rings are all six-membered rings, and two six-membered rings that share a hydrogen bond are represented by the same color. (b) Number of isomers and total cages along with the stretching process.

4 Conclusion

In this study, an efficient, accurate, and multifunctional HTR algorithm is introduced for the recognition of clathrate cages in a hydrate-based system. HTR is based on ring topology to identify cage structures, and the efficiency of cage recognition by HTR is innovatively improved via the splitting method, leading to the recognition time–the system size relationship changing from exponential to linear one. As a result, HTR can be effectively used for cage recognition of large-scale systems. HTR avoids overidentification of clathrate cages, and the accuracy and efficiency of cage identification by HTR were verified with other popular algorithms. Uniquely, HTR is able to identify multiple guests@cages and topological isomer structures of clathrate cages, as well as clathrate cages subjected to mechanical loads. The presented HTR algorithm is accessible for extracting helpful insights into the information of clathrate cages in a large-scale system of MD simulations.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help with the high-performance computer from Y. Yu and Z. Xu from Information and Network Center of Xiamen University.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11904300, 12172314, 11772278, and 11502221), the Jiangxi Provincial Outstanding Young Talents Program (Grant No. 20192BCBL23029), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Xiamen University: Grant No. 20720210025), and the Norwegian Metacenter for Computational Science (NOTUR NN9110K and NN9391K).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Sloan Jr ED, Koh CA. Clathrate hydrates of natural gases. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007.10.1201/9781420008494Search in Google Scholar

[2] Macdonald GJ. The future of methane as an energy resource. Annu Rev Energy. 1990;15:53–83.10.1146/annurev.eg.15.110190.000413Search in Google Scholar

[3] Koh CA, Sum AK, Sloan ED. Gas hydrates: unlocking the energy from icy cages. J Appl Phys. 2009;106:9.10.1063/1.3216463Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sum AK, Koh CA, Sloan ED. Clathrate hydrates: from laboratory science to engineering practice. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2009;48:7457–65.10.1021/ie900679mSearch in Google Scholar

[5] Kim SM, Lee JD, Lee HJ, Lee EK, Kim Y. Gas hydrate formation method to capture the carbon dioxide for pre-combustion process in IGCC plant. Int J Hydrogen Energ. 2011;36:1115–21.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.09.062Search in Google Scholar

[6] Dashti H, Thomas D, Amiri A. Modeling of hydrate-based CO2 capture with nucleation stage and induction time prediction capability. J Clean Prod. 2019;231:805–16.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.240Search in Google Scholar

[7] Park Y, Kim DY, Lee JW, Huh DG, Park KP, Lee J, et al. Sequestering carbon dioxide into complex structures of naturally occurring gas hydrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12690–4.10.1073/pnas.0602251103Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Jacobson LC, Hujo W, Molinero V. Thermodynamic stability and growth of guest-free clathrate hydrates: a low-density crystal phase of water. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:10298–307.10.1021/jp903439aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Mao WL, Mao HK, Goncharov AF, Struzhkin VV, Guo QZ, Hu JZ, et al. Hydrogen clusters in clathrate hydrate. Science. 2002;297:2247–9.10.1126/science.1075394Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] ten Wolde PR, Frenkel D. Enhancement of protein crystal nucleation by critical density fluctuations. Science. 1997;277:1975–8.10.1126/science.277.5334.1975Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Maddah M, Maddah M, Peyvandi K. Investigation on structural properties of winter flounder antifreeze protein in interaction with clathrate hydrate by molecular dynamics simulation. J Chem Thermodyn. 2021;152:106267.10.1016/j.jct.2020.106267Search in Google Scholar

[12] Pandey HD, Leitner DM. Thermodynamics of hydration water around an antifreeze protein: a molecular simulation study. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121:9498–507.10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b05892Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Mu L, Ramløv H, Søgaard TMM, Jørgensen T, de Jongh WA, von Solms N. Inhibition of methane hydrate nucleation and growth by an antifreeze protein. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2019;183:106388.10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106388Search in Google Scholar

[14] Yin ZY, Chong ZR, Tan HK, Linga P. Review of gas hydrate dissociation kinetic models for energy recovery. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2016;35:1362–87.10.1016/j.jngse.2016.04.050Search in Google Scholar

[15] Liu H, Kumar SK, Douglas JF. Self-assembly-induced protein crystallization. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103:018101.10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.018101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Debenedetti PG, Sarupria S. Chemistry. Hydrate molecular ballet. Science. 2009;326:1070–1.10.1126/science.1183027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Walsh MR, Rainey JD, Lafond PG, Park DH, Beckham GT, Jones MD, et al. The cages, dynamics, and structuring of incipient methane clathrate hydrates. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:19951–9.10.1039/c1cp21899aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Christiansen RL, Sloan ED. Mechanisms and kinetics of hydrate formation. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 1994;715:283–305.10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb38841.xSearch in Google Scholar

[19] Sloan ED, Fleyfel F. A molecular mechanism for gas hydrate nucleation from ice. Aiche J. 1991;37:1281–92.10.1002/aic.690370902Search in Google Scholar

[20] Yin ZY, Khurana M, Tan HK, Linga P. A review of gas hydrate growth kinetic models. Chem Eng J. 2018;342:9–29.10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.120Search in Google Scholar

[21] Khurana M, Yin ZY, Linga P. A review of clathrate hydrate nucleation. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2017;5:11176–203.10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03238Search in Google Scholar

[22] Guo GJ, Zhang YG, Li M, Wu CH. Can the dodecahedral water cluster naturally form in methane aqueous solutions? A molecular dynamics study on the hydrate nucleation mechanisms. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:194504.10.1063/1.2919558Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Guo GJ, Zhang YG, Liu CJ, Li KH. Using the face-saturated incomplete cage analysis to quantify the cage compositions and cage linking structures of amorphous phase hydrates. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:12048–57.10.1039/c1cp20070dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Nguyen AH, Molinero V. Identification of clathrate hydrates, hexagonal ice, cubic ice, and liquid water in simulations: the CHILL + algorithm. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:9369–76.10.1021/jp510289tSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Mahmoudinobar F, Dias CL. GRADE: a code to determine clathrate hydrate structures. Comput Phys Commun. 2019;244:385–91.10.1016/j.cpc.2019.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[26] Hao Y, Xu Z, Du S, Yang X, Ding T, Wang B, et al. Iterative cup overlapping: an efficient identification algorithm for cage structures of amorphous phase hydrates. J Phys Chem B. 2021;125:1282–92.10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c08964Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Matsumoto M, Baba A, Ohmine I. Topological building blocks of hydrogen bond network in water. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:134504.10.1063/1.2772627Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Laage D, Hynes JT. A molecular jump mechanism of water reorientation. Science. 2006;311:832–5.10.1126/science.1122154Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Dias CL, Ala-Nissila T, Grant M, Karttunen M. Three-dimensional “Mercedes-Benz” model for water. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:054505.10.1063/1.3183935Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Mahmoudinobar F, Dias CL, Zangi R. Role of side-chain interactions on the formation of alpha-helices in model peptides. Phys Rev E. 2015;91:032710.10.1103/PhysRevE.91.032710Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Zhang Z, Guo G-J. Comment on “iterative cup overlapping: an efficient identification algorithm for cage structures of amorphous phase hydrates”. J Phys Chem B. 2021;125:5451–3.10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c03705Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Li LW, Zhong J, Yan YG, Zhang J, Xu JF, Francisco JS, et al. Unraveling nucleation pathway in methane clathrate formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:24701–8.10.1073/pnas.2011755117Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Liang S, Liang D, Wu N, Yi L, Hu G. Molecular mechanisms of gas diffusion in CO2 hydrates. J Phys Chem C. 2016;120:16298–304.10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b03111Search in Google Scholar

[34] Lo H, Lee M-T, Lin S-T. Water vacancy driven diffusion in clathrate hydrates: molecular dynamics simulation study. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121:8280–9.10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00853Search in Google Scholar

[35] Lu Y, Sun L, Guan D, Yang L, Zhang L, Song Y, et al. Molecular behavior of CO2 hydrate growth in the presence of dissolvable ionic organics. Chem Eng J. 2022;428:131176.10.1016/j.cej.2021.131176Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Yisi Liu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials