A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

-

Mohammadmahdi Akbari Edgahi

, Amirhossein Emamian

Abstract

In this paper, we reviewed the recent advances in nanoscale modifications and evaluated their potential for dental implant applications. Surfaces at the nanoscale provide remarkable features that can be exploited to enhance biological activities. Herein, titanium and its alloys are considered as the main materials due to their background as Ti-based implants, which have been yielding satisfactory results over long-term periods. At first, we discussed the survivability and the general parameters that have high impacts on implant failure and the necessities of nanoscale modification. Afterward, fabrication techniques that can generate nanostructures on the endosseous implant body are categorized as mechanical, chemical, and physical methods. These techniques are followed by biomimetic nanotopographies (e.g., nanopillars, nanoblades, etc.) and their biological mechanisms. Alongside the nanopatterns, the applications of nanoparticles (NPs) including metals, ceramics, polymers, etc., as biofunctional coating or delivery systems are fully explained. Finally, the biophysiochemical impacts of these modifications are discussed as essential parameters for a dental implant to provide satisfactory information for future endeavors.

1 Introduction

Dental implants are the mainstream solution for lost teeth. They are fabricated to mimic the function of teeth and return the lost confidence to the patients. In the early 1980s, a 5 to 10 year follow-up on the survivability of dental prosthesis indicated an 81 and 91% survival rate in maxilla and mandible, respectively [1]. In this term, the definitions of survival rate and success rate are different. The survival rate represents the sustainability of the dental implants but the success rate also includes the patients’ general satisfaction. Therefore, after 40 years, statistics still show complications, especially in patients with diabetes or smoking background, which implies the necessities for the development of dental implants [2,3,4,5].

From the beginning of the 21st century, nanoscale modifications have been of great interest [6,7,8]. Materials at nanoscale display unique properties that can significantly enhance the characteristics of dental implants and further osteogenic responses [9]. These modifications have a key role in controlling essential parameters of an implant. Additionally, remarkable modifications can be obtained by the utilization of different nanoparticles (NPs) or nanopatterns, whereas manifold techniques can produce microscale surfaces, there is only a limited number of commercial techniques that grant nanoscale structures. These techniques, according to their performing conditions, are categorized as mechanical, chemical, and physical methods [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Considering the transgingival nature of dental implants, they form three main interfaces with the host’s biological system that consists of (i) the subgingival hard tissue interface of the endosseous implant body, (ii) the soft tissue transgingival interface at the implant neck and platform, and (iii) the interface to the oral cavity with its salivary environment at the transgingival and the supragingival region [17].

At the implant interface, where most complications are laid on, researchers have been evaluating the responses of bone to various NPs and nanopatterns [19,20,21,22]. Coating the implant surface with nanoscale particles surpassed the restriction of produced residues for some metallic elements (e.g., Cu) or extended their applications. Herein, NPs are classified as (i) metallic-based, (ii) ceramic-based, (iii) polymer-based, (iv) carbon-based, (v) protein-based, and (vi) drug-based [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Utilization of these NPs may either provide a suitable environment for biological agents or restrict the harmful agents from disturbing the biological system. Respecting these issues, a long-lasting coating with both promotive and restrictive functions is the optimal requirement for dental implants.

Aside from the inherent function of NPs, by engineering their characteristics, especially ceramic- and polymer-based materials, they can be used as delivery systems for a broad range of biomaterial or biomolecules with biogenic or biocidal activities [23]. Drug delivery in implants mainly occurs under degradation, diffusion, or osmosis mechanisms. Hence, the role of solubility in both the material matrix and payload is highlighted. Designing delivery systems create a suitable environment for these biomolecules to release at a controlled rate and maintain their function over a longer period. Therefore, a desirable drug delivery system can aid us to conquer several bone diseases and secure the success of implantation.

In addition to multifunctional coatings, surface nanotopographies are tremendously useful for biomedical applications that offer a broad spectrum of properties like mechano-bactericidal activity, which leads to the formation of multifunctional modifications. This activity was first found in nature by assessing bugs’ wings like Psaltoda claripennis against Gram-negative bacteria and it was completely related to physical antibacterial mechanisms and not chemical ones [34]. Technically, the mechano-bactericidal function of the surface belongs to the physical geometries of the nanopatterns that increase the stress beyond the elastic tolerance of the membrane [19]. Therefore, the quantity of biomaterials and subsequent adsorption rate are not involved in the elimination of bacteria, which help the surface to maintain its antibacterial function for longer periods than chemical compounds.

In this review, we cover some uses of nanotechnology for the modification of the endosseous implant body. Modifying an implant does not have a gold standard and every method may display acceptable results. However, utilization of state-or-art procedures provides the opportunity to combat the current challenges and guarantees success with higher satisfaction for patients. In the following sections, we provide pieces of information to fulfill the demands for optimizing dental implants.

2 Nanofabrication techniques

To modify the surface morphology of the implant, diverse techniques can be performed (Table 1). The utilization of these techniques, depending on the procedure and performing conditions, results in different surface characteristics. From a broad range of modification techniques, the following ones are frequently used to develop nanoscale surfaces at the endosseous body and can be commercially applicable. Of these techniques, mechanical methods are the initial stage of processing and they target the roughness and grain size of the surface layer. By including the acid etching (AE) from chemical methods, the average roughness (R a) of the surface can be predicted. The second stage is the accompaniment of either chemical or physical methods. Chemical methods refer to the use of chemical solutions, while physical methods are considered as the formation of materials under dry conditions.

A summary of nanofabrication techniques and their advantages for dental implants [101]

| Mechanical methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | Surface morphology | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Machining | 0.3–1 µm R a with 10 nm oxide layer | • Enhanced cell adhesion and osteointegration | • Fabricating imperfect surfaces that prolong the healing process | |

| Grinding | Less than 1 µm R a | • Improved osteointegration, hydrophilicity, density, and viscosity | • May cause several damages to the surface | |

| • Difficult operation for dental implants | ||||

| Polishing | ∼ 350 nm R a | • Improved osteointegration and surface quality | • Performing multiple steps | |

| • The potential to use different chemicals within the slurry | ||||

| SB | 0.3–3 µm R a | • Enhanced osteointegration | • Particles remain on the surface | |

| • Controllable surface roughness | ||||

| SP | 25–80 nm grains | • Increased cell adhesion, differentiation, and viability | • Superficial grain refinement | |

| • Higher surface quality | • Limited particle size for dental application | |||

| Attrition | Less than 100 nm grains | • Higher surface quality | • Not applicable for dental implant | |

| • Deeper grain refinement | • Increased hydrophobicity at smaller scales | |||

| Chemical methods | ||||

| Technique | Surface morphology | Advantages | ||

| AE | 0.3–1 µm R a with 10 nm oxide layer | • Increase anchorage of fibrin and osteogenic cells | ||

| • Potential of fabricating nanotopography | ||||

| HPT | Less than 10 nm inner oxide layer | • Improved biocompatibility | ||

| Up to 40 nm outer porous layer | • Ability to form apatite | |||

| AT | ∼1 µm layer of sodium titanate (Na2TiO3) gel | • Improved cell differentiation | ||

| • Ability to form apatite | ||||

| Sol–gel | Less than 10 µm of a thin layer of ceramic | • Wide selectivity of biomaterials | ||

| • Ability to deposit complex compounds | ||||

| • Easy processes | ||||

| • Highly bioactive surface | ||||

| Electrochemical treatment | ∼ 10 nm–10 µm layer of uniform TiO2 | • Enhanced bioactivity and corrosion resistance | ||

| • Potential of fabricating nanotopographies | ||||

| CVD | ∼1 µm layer of TiC, TiN, TiCN, diamond-like carbon, and diamond NPs | • Enhanced biocompatibility | ||

| • Significantly high surface quality | ||||

| SAMs | — | • Highly improved biogenic and/or biocidal activities | ||

| Physical methods | ||||

| Technique | Surface morphology | Advantages | ||

| PS | Less than 100 nm layer of metallic, ceramic, or polymer compounds | • Improved surface quality and biocompatibility | ||

| • Wide selectivity of biomaterials | ||||

| SD | Less than 1 µm layer of TiC, TiN, TiCN, and amorphous carbon | • Enhanced biocompatibility | ||

| • Significantly high surface quality | ||||

| IBAD | ∼10 nm of a modified layer with/without TiN or TiO2 | • Enhanced biocompatibility | ||

| • Significantly high surface quality | ||||

| Lithography | ∼60 nm layer of ultrafine nanotopography | • Potential of fabricating specific nanotopographies | ||

| • Enhanced bioactivity | ||||

| • Improved bone-implant contact | ||||

| Laser treatment | — | • Ability to fabricate multiphase composition at micro- and nanoscale | ||

| • Improved cell adhesion and overall biogenic activities | ||||

Bear in mind that despite the potential of producing the same surface (e.g., HAp-coated Ti) by the same or two different techniques, the ultimate result and performance may be different [35,36]. Hence, nanofabrication techniques and their performing conditions should be wisely selected.

2.1 Mechanical methods

Of the initial manufacturing processes of implants, mechanical methods were commonly used until the 1990s. Gradually, by the development of surface morphology at smaller scales, machining, grinding, polishing, and sandblasting (SB) are employed to modify the surface and enhance the general roughnesses, whereas shot peening (SP) and attrition are used as surface-improving methods to refine the grain size of the top surface.

2.1.1 Machining

Back in the 1990s, machining was an essential step of dental implant treatment and it refers to the lathing, milling, or threading of manufacturing processes. The R a values obtained by machining on the Ti surface were 300 nm to 1 µm with 2–10 nm thickness of the amorphous TiO2 layer [37]. This imperfect surface generated by machining can promote cell adhesion and increase osteointegration but it simultaneously prolongs the healing period [38]. Salou et al. produced a regular array of TiO2 nanotubes with a diameter of 37 nm and thickness of 160 nm by machining and it displayed notable enhancements in osteogenesis and osteointegration [39].

2.1.2 Grinding

Grinding involves diverse methods of abrasive activities to treat metallic surfaces. Generally, there are two frequently used procedures by either utilization of a belt machine with the help of a robotic arm or a grinding wheel with coarse particles to abrade the surface. The belt machine is at disadvantage to producing nanoscale surfaces but the grinding wheel with abrasive grade 60 is able to produce R a values of less than 1 µm [40].

In spite of its simplicity, grinding low thermal conductive metals or alloys like Ti grade-5 could cause issues including thermal damage, surface burn, residual stresses, and grit dislodgement [41]. Therefore, conducting parameters in each procedure should be carefully adjusted. Madarkar et al. abraded Ti grade-5 by using ultrasonic vibration-assisted minimum quantity lubrication (UMQL) and conventional MQL (CMQL) to improve the quality of the surface. They reported that the variation of vegetable oil in UMQL led to different hydrophilicity, density, and viscosity as well as a reduction in cutting forces compared to CMQL. However, resulting roughnesses from UMQL were slightly higher than those of CMQL [42].

2.1.3 Polishing

Alike grinding, polishing is a cost-efficient method that follows similar protocols but with the use of fine abrasive particles. Generally, polishing is conducted through multiple processes using coarse abrasive SiC paper with 50 to 220 grit for the initial step and then finer abrasive SiC papers above 600 grit for the next step to obtain a mirror-like surface [40]. In chemical mechanical polishing, the produced R a values are highly dependent on the slurry. In this case, alumina (Al2O3), silica (SiO2), and diamond slurry are frequently used since they should be chemically inert [43,44,45]. Ozdemir et al. evaluated the influence of pad types to optimize the roughness while forming an oxide layer on the surface. They reported that the lowest roughness, R a of 350 ± 30 nm, was obtained via alumina slurry with 3 wt% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [44].

2.1.4 Sandblasting (SB)

SB, also known as grit blasting, is a commonly used method to treat the surface and modify the R a values. Despite machining, surface topography achieved by SB is highly dependent on the particle size [46]. Generally, SB refers to the projection of micro/NPs such as Al2O3, silica, titania (TiO2), and CaP bioceramics through a nozzle onto the surface by compressed air to erode the surface (Figure 1). R a values of blasted Ti were 300 nm to 3 µm [32]. More importantly, the particles used should be chemically stable and not cause further complications [47]. SB is a more favorable technique due to its capability of controlling surface roughness. This advantage became noteworthy as Jamet et al. found that the accumulation of bacteria on a rougher surface is higher than a smoother surface [48]. Schupbash et al. analyzed the surface of seven different dental implant manufacturers. They reported that the presence of particles made by SB on implants is different and not all manufacturers control the remaining particles on their implant surfaces [49].

![Figure 1

Schematic illustration of the SB process [49]. Copyright 2014, Hindawi.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_001.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the SB process [49]. Copyright 2014, Hindawi.

2.1.5 SP

SP, also known as shot blasting, is a surface-improving method that promotes performance and reduces maintenance of the metallic components with a cost-effective solution. SP is a similar action as SB but with sufficient force strikes to create a plastic deformation. Herein, large metallic or ceramic balls with 0.25–1 mm diameter at 20–150 m/s velocity bombard the surface [50]. Technically, peening is employed to refine the grain structure of the surface by inducing residual compressive stress through a projection of high quality and inert particles to remove unfavorable tensile stresses from the surface [51]. With SP, it is possible to obtain 25–80 nm grains on the surface layer [52]. Deng et al. and Ganesh et al. studied the physiobiological effect of SP on Ti surfaces. The results displayed that utilization of different particles can fairly or significantly change the roughness, yet it can always increase hardness and fatigue resistance. Also, a treated surface can enhance cell adhesion, differentiation, and viability [51,53].

2.1.6 Attrition

Surface mechanical attrition treatment (SMAT) is a derived version of the SP method with a higher potential to produce a nanocrystalline surface layer. In SMAT, 2–10 mm diameter particles at 5–15 m/s velocity project multidirectionally to the surface, and consequently, create multidirectional severe plastic deformations. Compared to SP, SMAT has higher kinetic energies that lead to the formation of a thicker nanocrystalline surface layer and deeper residual compressive stress [54]. Jamesh et al. investigated the effects of SMAT on the CP-Ti surface using 8 mm diameter Al2O3 for 900, 1,800, and 2,700 s. They reported that at each time interval, the roughness of the surface increased whereas the level of hydrophilicity decreased. Also, they mentioned that the 900 s projection was not able to form apatite until the 28th day [55].

2.2 Chemical methods

To alter the topography of the implant surface, chemical methods are the best choices. These methods include several techniques that change an inert surface of an implant to a bioactive surface via oxidation, deposition, coating, or immobilization. Chemical solutions and their compounding ratios are the vital parts of the chemical surface treatment that can result in different physiobiological responses [56].

Primarily, chemical methods consist of AE, hydrogen peroxide treatment (HPT), alkali treatment (AT), sol–gel, electrochemical treatment, chemical vapor deposition, and biochemical methods, which form a nanolayer on the implant surface. Moreover, these methods are composed of other diverse techniques like esterification, coupling agent, and surface grafting that grant improvement in the biological activity of the surface, but, herein, they are omitted due to the inability to generate nanostructures [10].

2.2.1 AE

AE is used to clean and remove any oxide contamination from the layer and produce a homogenous surface (Figure 2). Chemical acids such as sulfuric acid (H2SO4), hydrochloric acid (HCl), hydrofluoric acid (HF), and nitric acid (HNO3) are commonly used acids to produce the R a values of 300 nm to 1 µm with approximately 10 nm thickness of the amorphous TiO2 layer [57]. AE is commercially a popular technique and is usually accompanied by another acid as dual AE or another technique (e.g., pre-SB or double AE) to improve osteoconductivity [58].

![Figure 2

Schematic illustration of the AE process [49]. Copyright 2014, Hindawi.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_002.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the AE process [49]. Copyright 2014, Hindawi.

Typically, etching an implant surface changes the R a values that lead to increasing anchorage of fibrin and osteogenic cells [59]. To obtain favorable roughness, diverse parameters including bulk material, material phases, surface structure, surface impurities, acid, temperature, and soaking time must be taken into account. Variola et al. reported that a nanopit network with different diameters ranging from 20 to 100 nm can be fabricated via a combination of strong acids or bases and oxidants on CP-Ti [60]. Lamolle et al. etched Ti implants with HF acid and reported that by controlling the aforementioned parameters and solution contents, it is possible to fabricate micro- and nanoscale topography to increase biocompatibility and provide a suitable substrate for cell growth [61].

2.2.2 HPT

HPT is a technique to enhance the bioactivity of Ti implants by the formation of a gel-like anatase layer on the implant. Anatase permits the bone-like apatite to deposit after the immersion in simulated body fluid (SBF) [62]. The altered surface escalates the osteoblast-like cells and subsequently accelerates osteointegration [63]. Wang et al. fabricated an amorphous layer of TiO2 on the CP-Ti sheets by the combination of HPT with AE, followed by thermally treating up to 800°C (Figure 3). They concluded that the optimal solution contents and heating temperature to obtain the highest bioactivity were H2O2/0.1 M HCl (1 M X/0.1 M Y)-solution and 400–500°C [35]. Khodaei et al. evaluated the addition of F− or Cl− to H2O2 solution and concluded that the addition of different ions to oxidizing ions can affect the phase morphology and wettability [64].

![Figure 3

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of hydroxyapatite deposited on the Ti surface (a and b) using HPT and (c and d) sol–gel techniques. The newly formed apatite layer depending on different conditions, pH, temperature, and time led to (a and c) initial and (b and d) complete stages of HAp formation. [35] Copyright 2002, Elsevier; [36] Copyright 2020, Medico-Legal Update.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_003.jpg)

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of hydroxyapatite deposited on the Ti surface (a and b) using HPT and (c and d) sol–gel techniques. The newly formed apatite layer depending on different conditions, pH, temperature, and time led to (a and c) initial and (b and d) complete stages of HAp formation. [35] Copyright 2002, Elsevier; [36] Copyright 2020, Medico-Legal Update.

2.2.3 AT

AT is the use of basic solutions (e.g., NaOH) to form a bioactive nanostructured layer like sodium titanate (Na2O7Ti3) on the implant surface [65]. Upon immersion in SBF, sodium ions in the layer are exchanged with H3O+ from the adjacent fluid and form Ti–OH groups; these groups interact with Ca2+ ions and produce amorphous calcium titanate (CaTiO3), and ultimately, with phosphate polyatomic ions (e.g., HPO4 2−), they form amorphous bone-like apatite on the implant surface. The formation of the apatite layer on the Ti surface provides a favorable substrate for bone marrow cell differentiation [66].

Pattanayak et al. found that exposing Ti to the strong acid solutions (pH < 1.1) or strong basic solutions (pH > 13.6) can form bone-like apatite on the surface after immersion in SBF within 3 days. Also, they observed immediate apatite formation after the heat treatment process. Generally, the generation of the apatite layer relates to the magnitude of the positive or negative surface charge developed on the Ti surface (Figure 4) [67]. Wang et al. developed an economical surface treatment via a combination of AE and AT techniques to enhance hydrophilicity and osteoconductivity of poly(etheretherketone) (PEEK). They used 98 wt% H2SO4 as an AE solution for 5–90 s and 6 wt% NaOH for 20 s. The best enhancement was observed at 30 s etching, which decreased the contact angle (CA) from 78° to 37° [68].

![Figure 4

FE-SEM images of the Ti surface exposed to solutions with different pH values and subsequently immersed in SBF for 3 days (a) before and (b) after heat treatment [67]. Copyright 2012, The Royal Society.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_004.jpg)

FE-SEM images of the Ti surface exposed to solutions with different pH values and subsequently immersed in SBF for 3 days (a) before and (b) after heat treatment [67]. Copyright 2012, The Royal Society.

2.2.4 Sol–gel

Sol–gel, also called wet chemical deposition, is a widely used technique to enhance the bioactivity of the implant surface (Figure 5). The sol–gel technique is based on colloidal suspensions in a liquid solution that generates a solid layer by deposition of micro/NPs on a substrate. Simply, it is used to coat a thin film of biomimetic compounds (e.g., CaP compounds) to subsequently increase osteointegration [69].

![Figure 5

Schematic illustration of the sol–gel techniques [72]. Copyright 2020, Frontiers.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_005.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the sol–gel techniques [72]. Copyright 2020, Frontiers.

Of the notable benefits of this technique, it is possible to maintain the activity of biomolecules and deposit more complex compounds (e.g., compounds with the incorporation of drugs) on the implant surface [70]. Moreover, sol–gel has the potential to deposit an extended range of metal oxides such as TiO2, TiO2–CaP composite, or silica-based coatings on metallic/nonmetallic surfaces [71]. Esmael et al. successfully coated HAp and chitosan NPs on the Ti surface and immersed it in SBF. They reported that utilization of HAp has a synergetic impact on both the bioactivity and new apatite formation (Figure 3) [36].

2.2.5 Electrochemical treatment

Electrochemical treatment mainly refers to the three techniques, namely, anodic oxidation (AO), macro-arc oxidation, and electrophoretic deposition, which are commonly used in dental implant surface treatments.

2.2.5.1 AO

AO, also known as anodization, is a technique to fabricate nanostructured surfaces via potentiostatic or galvanostatic anodization by controlling several parameters including electrolyte composition, electric current, anode potential, temperature, and distance between the anode and cathode (Figure 6). Herein, implant as the anode is immersed in a homogenous electrolyte containing strong acids such as phosphoric acid (H3PO4), ammonium fluoride (NH4F), H2SO4, HF, or HNO3 or inhomogeneous electrolytes such as NaCl:NH4F [73] and NaHSO4:HF:NaF [74] with the passage of a high current density or voltage.

![Figure 6

Schematic illustration of the AO process [77]. Copyright 2017, Journal Teknologi.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_006.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the AO process [77]. Copyright 2017, Journal Teknologi.

AO enhances the corrosion resistance of metals (e.g., CP-Ti or Ta) by the formation of thick oxide layers. Moreover, the fluoride ions present in the electrolyte results in a nanotubular structure on titania [75]. Fialho et al. compared single and double AO on the Ta surface with the incorporation of Ca2+, PO4 3−, and Mg2+ ions on the surface; after the first anodization, enhancements in roughness and hydrophilicity were observed but after the second one, they also formed an amorphous tricalcium phosphate (TCP) on the surface [76].

2.2.5.2 Micro-arc oxidation (MAO)

MAO, also called plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO), is the modified version of the AO technique with the assistance of plasma and high voltage to fabricate oxide protective layers on metallic surfaces like Ti, Ta, Mg, Al, and Zr and their alloys [78]. Alike AO, the implant as the anode and the stainless steel as the cathode are immersed in an electrolyte and a high voltage is applied on the electrolyte that gradually coats an oxide layer on the implant surface [79].

In MAO, the electrolyte composition is the key parameter that defines the final composition, porosity, and thickness of the coated layer. Sedelnikova et al. fabricated the Sr–Si–CaP and Ag–CaP incorporated coatings with different ratios of electrolytes and reported that the Ag–CaP coating contained pores and isometric particles of β-TCP uniformly distributed but the Sr–Si–CaP coating had spheroidal elements and open pores on their surfaces [80].

2.2.5.3 Electrophoretic deposition (ED)

ED is a cathode-based electrochemical method. ED refers to the deposition of colloidal particles on the substrate by passing a high voltage in a suspension (Figure 7). This method has the potential to coat HAp NPs with 18 nm thickness on the surface within 30 min [81]. Moreover, the combination of MAO and ED can generate a top layer of phase-pure HAp and an interlayer of anticorrosive TiO2 [82]. Hashim et al. evaluated the syntheses and deposition of TiO2, ZnO, and Al2O3 by rapid breakdown anodization (RBA) and ED. They reported that Ti, TiO2 and Zn, ZnO particles were able to form bone-like apatite using the RBA technique but Al2O3 did not have the potential [83].

![Figure 7

Schematic illustration of the electrophoretic deposition process [84]. Copyright 2015, ACS.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_007.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the electrophoretic deposition process [84]. Copyright 2015, ACS.

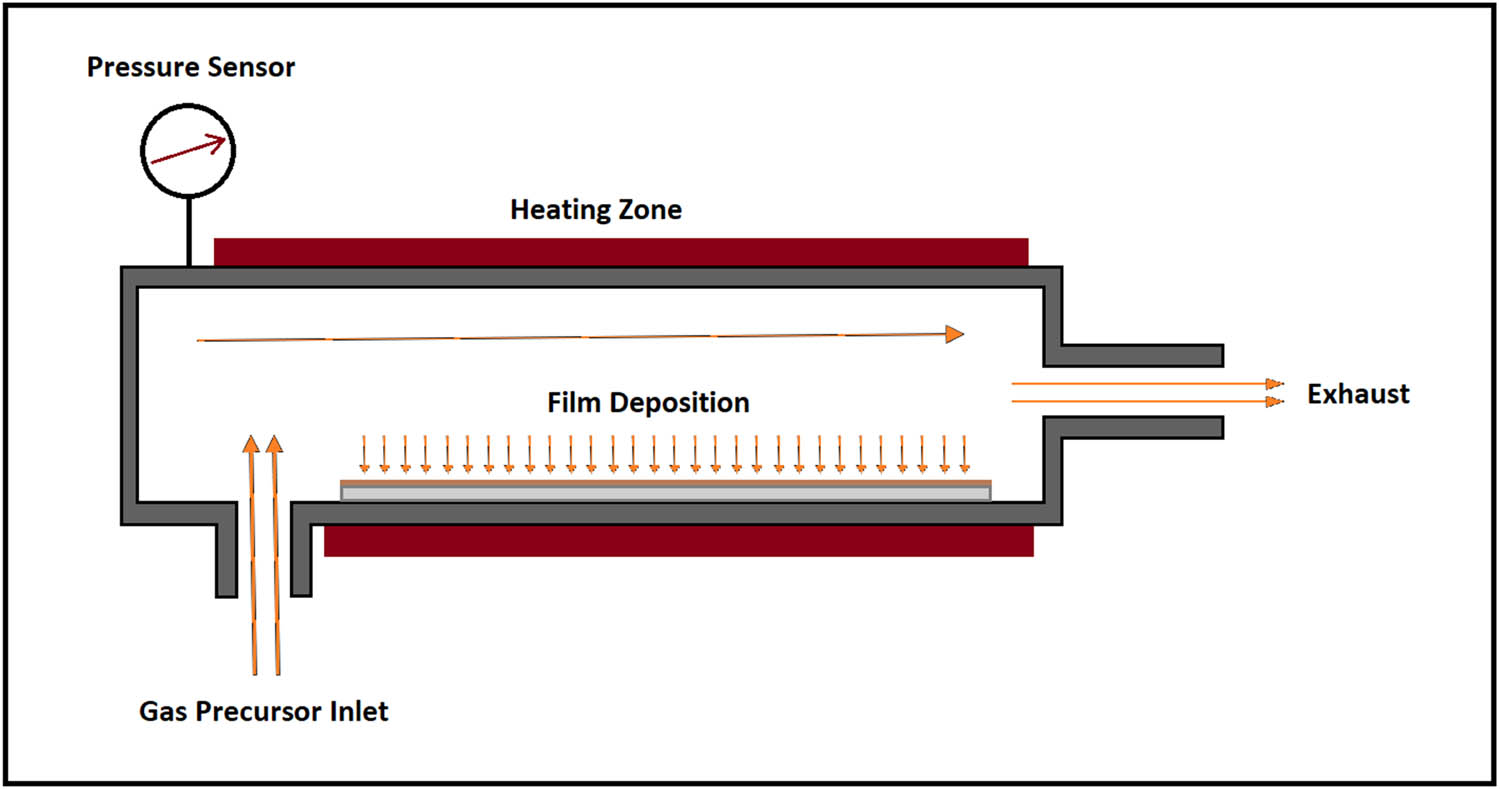

2.2.6 Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)

CVD is used to form thin layers on the implant surface by gaseous compounds. CVD involves chemical reactions between gas-phase chemicals and the surface that deposits nonvolatile compounds on the surface (Figure 8). Kania deposited diamond NPs on Ti orthopedic implants and observed notable increases in hardness, toughness, and adhesion [85]. CVD can be performed by many approaches and include atmospheric-pressure CVD (APCVD), low-pressure CVD (LPCVD), plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD), and laser-enhanced CVD (LECVD). Moreover, a combination of CVD and PVD as a hybrid method was also developed [11].

Schematic illustration of a chemical vapor deposition system.

CVD is capable of metalloceramic coatings by which it is possible to form nanocrystalline metallic bonds at the interlayer and hard-ceramic bond on the surface that subsequently overcomes adhesion problems in ceramic hard coatings on metallic substrates [86]. Chen et al. evaluated enhanced fluorine and oxygen mono/dual CVD to produce nanoscale coatings with antibacterial activity on the Ti surface. They found that fluorine deposited surface is able to kill Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) bacteria. Also, the presence of F and O elements has synergetic impacts on antibacterial activity, promotion in cell spreading, improvement in corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility [87].

2.2.7 Biochemical methods

To modify the implant surface with superior biological activities, biomolecular cues (BMCs) and antibacterial agents or drugs are the best candidates. The utilization of these large molecules is classified under biochemical methods, which is a subgroup of chemical methods. Hence, sole or incorporation of different biological materials with biomaterials has been seen, like BMCs with osteoinductive effect (e.g., cell adhesive proteins), nano CaP compounds with BMCs or antibacterial drugs, or direct coating of antibacterial agents or drugs. It should be noted that obtaining the aforementioned coatings can also be achieved via methods like sol–gel and magnetron sputtering (MS). However, SAMs are technically used to coat nanoscale biochemical molecules on the implant.

2.2.7.1 Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)

SAMs can spontaneously coat nanoscale biochemical molecules by exposing specific substrates and functional end groups (Figure 9). SAMs are formed by the adsorption and self-assembly of molecules (e.g., alkane phosphate) and biomolecules [e.g., growth factors like bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2)] at the interface, which may either accelerate or provide different bioactivities [88,89,90]. Herein, surface roughness has a superior impact on the anchorage of fibroblast cells than wettability [15]. Moreover, surface modification techniques and molecular grafting have a synergetic role to increase the reactiveness between the outward surface and tailored ends of SAM molecules [91].

![Figure 9

Schematic illustration of the SAM process, preparing, and analyzing antibacterial activity of cefotaxime sodium-decorated Ti by coating polydopamine (PDA). The possible chemical structure, as well as the suggested reaction mechanism, is also shown [96]. Copyright 2014, Journal of the Royal Society Interface.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_009.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the SAM process, preparing, and analyzing antibacterial activity of cefotaxime sodium-decorated Ti by coating polydopamine (PDA). The possible chemical structure, as well as the suggested reaction mechanism, is also shown [96]. Copyright 2014, Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

SAMs have the potential to immobilize biocompatible molecules on the surface (linking function) that helps the ECM components (e.g., laminin [92], fibronectin [93], heparin [94], collagen [95], antibiotics [96], and growth factors [97]) to covalently bound onto the Ti surface. Urface et al. self-assembled arginine-glycine-aspartic-cysteine (RGDC) on the gold-coated Ti surface and observed enhancements in cell attachment, spreading, and proliferation [98].

2.3 Physical methods

Physical methods of modification are the transformation of an inert surface to a bioactive one under dry processes. These methods include a variety of single/hybrid procedures which generate a bioactive surface via the formation of layers of material on the surface or decontaminating it. Primarily, physical methods include plasma spray (PS), physical vapor deposition, ion-beam deposition, lithography, and laser treatment.

2.3.1 Plasma spray (PS)

PS is the most widely used technique to coat biomaterials on the implant surface. PS is the process of projection and condensation of high-temperature molten droplets on the surface (Figure 10). The temperature achieved by PS is much higher than similar procedures, which vary its applications of coating an extended group of materials such as Au, Ag, Ti, Zr, as well as other metals, ceramics, and polymers with the thickness of <100 nm [21,66,99]. Wang et al. coated Ti surface with Ta after two-step of AO and reported that Ta/TiO2 nanotubes were fabricated at micro- and nanoscales. Also, numerous enhancements in roughness, wettability, adhesion, differentiation, mineralization, and osteogenesis-related gene were observed [100].

![Figure 10

Schematic illustration of the PS process [72]. Copyright 2020, Frontiers.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_010.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the PS process [72]. Copyright 2020, Frontiers.

2.3.2 Physical vapor deposition (PVD)

PVD is used to produce metal particles that react with reactive gases to form compounds deposited on the implant surface. Technically, high-energy ions are ejected in a vacuum chamber that changes the surface of the substrate and form thin films (Figure 11).

![Figure 11

Schematic illustration of the physical vapor deposition process, sputtering, for deposition of target coatings [103]. Copyright 2021, MDPI.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_011.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the physical vapor deposition process, sputtering, for deposition of target coatings [103]. Copyright 2021, MDPI.

PVD includes three techniques, namely, evaporation, ion plating, and sputtering. Herein, sputtering, also known as sputtering deposition (SD), and derived techniques of ion plating are the most commonly used methods to deposit nanostructured films on the implant surface. Moreover, the development of SD led to more advanced techniques called ion beam sputtering (IBS) and MS (Figure 12) [101]. Huang et al. evaluated the incorporation of antibacterial agents onto the surface of the implant via the MS technique. They observed an acceptable bactericidal effect under optimum processing parameters [102].

![Figure 12

Schematic illustration of the MS process [104]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_012.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the MS process [104]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry.

2.3.3 Ion-beam-assisted deposition (IBAD)

IBAD is the combination of ion implantation and SD. In the IBAD technique, the implant surface is covered with an elemental cloud that is formed by ion bombarded precursors and targeted by highly energetic gas ions (e.g., inert Ar+ ions or reactive O2+ ions) to collide the gaseous ions to substrate ions and decrease the energy of the precursors in the elemental cloud to form a thin layer of material on the surface (Figure 13).

![Figure 13

Schematic illustration of the IBAD system and process [105]. Copyright 2011, Elsevier™.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_013.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the IBAD system and process [105]. Copyright 2011, Elsevier™.

This technique has several potentials including synthesis of the highly pure layer under ultraclean process and notable adhesion between the deposited layer and implant; also the process does not change the bulk properties of the substrate and it can be performed under controlled conditions [105]. The variables such as time, temperature, and amount of the water vapor present are considered as the main contributors to favorable crystallinity. Usually, this method is accompanied by heat treatment to change the amorphicity of the deposited layer to a crystalline phase. Miralami et al. fabricated ZrO2 and TiO2 coatings on the Ti surface. They found that nanostructures generated by IBAD enhanced bone-associated gene expression at initial cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [106].

2.3.4 Lithography

Lithography is a favorable technique in electronic industries and is used to pattern specific models on a rigid substrate. Lithography consists of both top-down and bottom-up procedures to fabricate nanostructures. In top-down procedures, three widely used techniques including photolithography, electron beam lithography, and colloidal lithography are used and in bottom-up procedures, techniques like polymer phase separation, colloidal lithography, and block copolymer lithography are well-known [20,107]. The concept of patterning is simple, for example in photolithography, a predefined pattern is fabricated on a mask and locates upon the substrate that has been coated by a photoresist layer (e.g., chromium) and after the exposure of ultraviolet (UV) radiations, the pattern will transfer into the surface and the remaining photoresist layer can be chemically etched (Figure 14) [13]. Generating nanostructures with photolithography smaller than 100 nm is restricted by its diffraction limits [108]. However, electron beam lithography has overcome the limitation and has the potential to fabricate nanostructures down to 5–7 nm [109,110].

![Figure 14

Schematic illustration of photolithography [111]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier™.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_014.jpg)

Schematic illustration of photolithography [111]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier™.

2.3.5 Laser treatment

Laser treatment uses high-energy beams to generate 3D structures at the micro/nanoscale. This technique is capable of producing complex selective surface topography with high resolution [112]. Moreover, laser treatment is a rapid and ultraclean nanofabrication technique that has precise, targeted, and guided surface roughening that can be performed under controlled conditions for the selective changes in implants [66]. Chang et al. used 3D laser-printed porous Ti grade-5 and reported that porous dental implant had the active new bone formation and good osteointegration. Also, its biomechanical parameters are significantly higher than the commercially controlled samples [113].

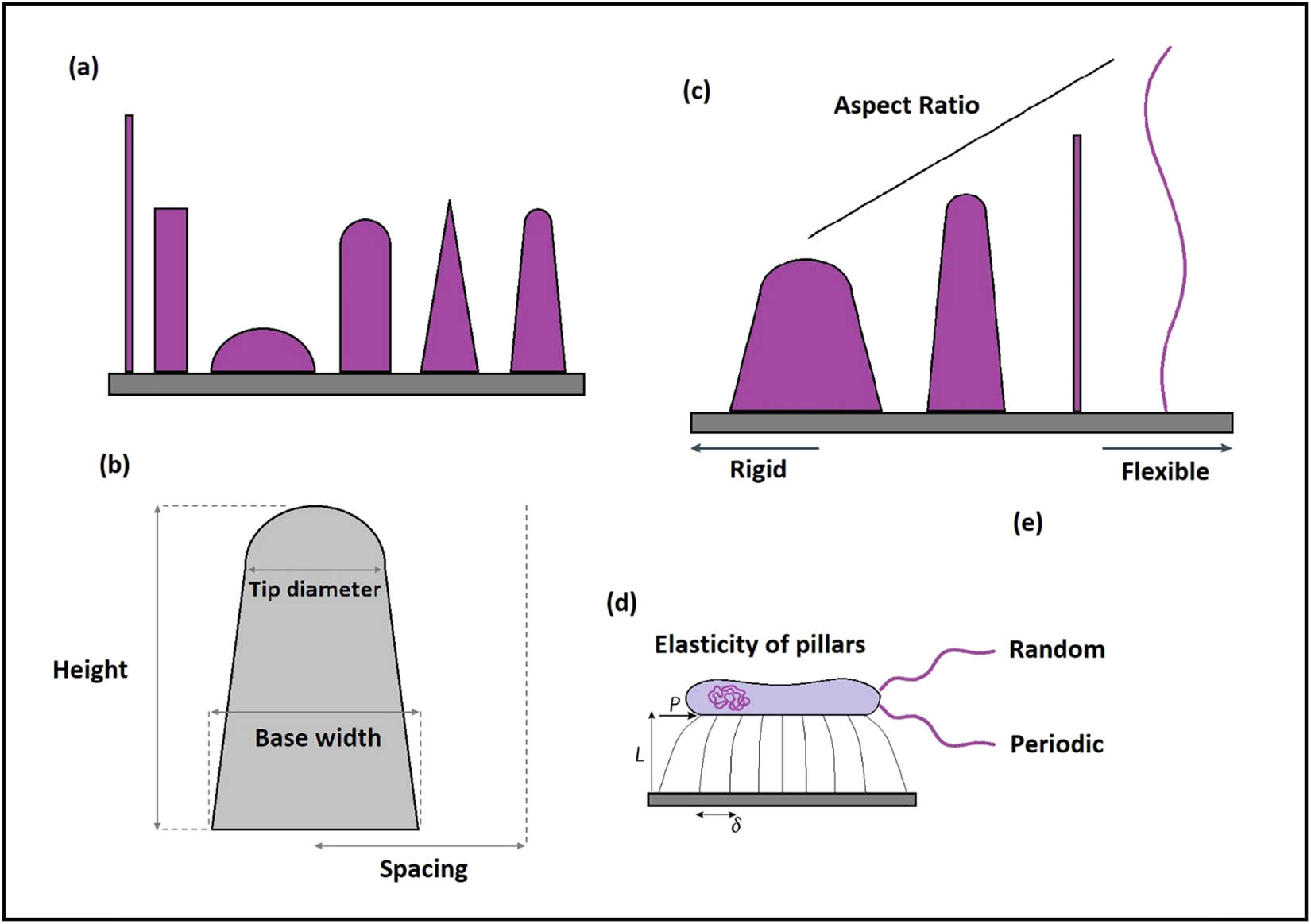

3 Surface nanotopography

Recent advances in implant development have led to nanoscale topographies. Nanotopography is a characteristic of a surface that implies a specific physiobiological interaction between the nanopatterns and the environment. At the nanoscale, better interaction with the cell membrane has been reported [114]. Generally, numerous nanopatterns have been developed for bone regeneration applications (Figure 15). Therefore, biomimetic nanotopographies with mechano-bactericidal activity attracted a lot of attention as they can rupture the cell membrane through physical forces (Figure 16). This group is categorized into two subclasses: (i) nanopillars and (ii) nanoblades and their derivations. The first consists of nanopillars, nanospikes, nanotubes, nanocones, nanospears, nanoneedles, nanowires, and spinules. The latter includes nanoblades and nanocolumns [19,115].

![Figure 15

Schematic illustration of some nanopatterns [121]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier™.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_015.jpg)

Schematic illustration of some nanopatterns [121]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier™.

![Figure 16

Schematic illustration of the mechano-bactericidal function of the surface. (a) Contacts of a bacteria cell with the wing nanopillar surface. (b) Adsorption of the membrane to the surface protrusions leads to stretching of the cell membrane. (c) Gradual progress of adsorption leads to broad stretching at the contact regions and ultimately (d) cell death [122]. Copyright 2013, Elsevier™.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_016.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the mechano-bactericidal function of the surface. (a) Contacts of a bacteria cell with the wing nanopillar surface. (b) Adsorption of the membrane to the surface protrusions leads to stretching of the cell membrane. (c) Gradual progress of adsorption leads to broad stretching at the contact regions and ultimately (d) cell death [122]. Copyright 2013, Elsevier™.

The efficacy of bactericidal activity of nanopillars is dependent on several parameters but only four key geometric parameters including spacing, base diameter, tip diameter, and height are considered for the measurements (Figure 17) [116]. However, obtaining the optimum results requires considering the finite size and shape of bacteria plus the geometry of the nanopattern on the degree of bacterial membrane stretching using parameters such as bacterial stretching modulus, bending modulus, adhesion energy of the cell membrane, as well as radius, height, and spacing of the nanopillars [117].

Schematic illustration of the physical parameters affecting the mechano-bactericidal activity of nanopillars and their derivations. (a) Examples of different nanopatterns with varied biocide levels. (b) The geometric characteristics are simplified based on the spacing, base diameter, tip diameter, and height. (c) Increasing the aspect ratio changes the rigid nanopillar to a flexible one, and subsequently, is accompanied by different cellular and antibacterial responses. (d) According to the aforementioned parameters, the strength of each individual nanopattern to impose physical forces on the cell membrane is related to the geometries. (e) Fabrication of nanopatterns can be either in random or periodic arrays. Therefore, the optimized mechano-bactericidal function demands significant attention to the geometric parameters and cautious fabrication.

Normally, nanopatterns are biocompatible yet decreasing in parameters like the tip diameter can reversely affect the osteogenic cells [118]. Therefore, utilization of nanotopographies with no bactericidal potential may be a sensible option as they are still able to chemically interact with bacteria and eliminate them. Of this group, nanopillars, nanotubes, nanofibers, nanogrooves, nanopits, and nanorods demonstrated higher cellular affinity [20,119,120].

3.1 Nanopillars

Nanopillars can be fabricated on the Ti surface by the AO technique with different states in arrangement [123,124]. The mechano-bactericidal activity of this nanotopography was first found from surfaces in nature [34]. This activity occurs by scratching the adsorbed cell wall and rupturing it by putting stress beyond its elastic limit [117,122,125]. Biologically, changes in the height of nanopillars lead to different responses from the cytoskeletal organization and cell morphology. The bactericidal mechanism of nanopillar and its derivations can be augmented by the deflection of elastic nanopatterns that induce additional lateral stress on the bacterial cell wall (Figure 18) [126]. In this case, both carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and high-aspect-ratio silicon nanowires displayed notable promotion in their mechano-bactericidal activity caused by their potential to deflect regarding bacterial attachment.

![Figure 18

SEM images of some (a–d) natural bactericidal nanotopography and (e–h) synthetic bactericidal nanotopography [131]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier™.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_018.jpg)

SEM images of some (a–d) natural bactericidal nanotopography and (e–h) synthetic bactericidal nanotopography [131]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier™.

As shown in Figure 17(d), the amount of lateral tip deflection (δ) caused by the generated forces from bacterial adsorption (P) is controlled by the length (L) of the nanopillars, as well as the attaching position of the bacteria to the cell membrane. Therefore, to obtain equal energy as longer nanopillars, shorter and low-aspect-ratio nanopillars should deflect less. Mcnamara et al. evaluated the cell organization of cytoskeleton cells on different nanopillars’ heights (8, 15, 55, 100 nm pillars) spread to polygonal shapes and observed that cytoskeleton cells were highly organized on 8 and 15 nm pillars, while by a gradual increase in the height, less organization were seen [127,128]. Moreover, planar control can significantly affect the focal adhesions and most of the larger focal adhesion per cell, but it can reversely affect the total number of adhesions per cell [127,128]. Similarly, variation in nanopillars’ height could not affect the osteogenic differentiation but it could enhance its bactericidal activity as it was higher and sharper [123,129]. Also, differences in their shapes can significantly affect osteogenic cell differentiation [130].

3.1.1 Nanospikes

Nanospikes are a derivation of nanopillars with a longer length, sharper tips, and high aspect ratio. Physical parameters of nanospikes were 20–80 nm in diameter and 500 nm in height, which by considering their sharpness, they can also restrict cellular activities. Therefore, Ivanova et al. fabricated the only in vivo biocompatible and mechano-bactericidal nanospikes by using black silicon [118]. Nanospikes are able to induce severe stress on the cell membrane that has high efficacy against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, even highly resilient Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) endospores were annihilated [132]. Black silicon nanospikes are not able to interact with the biological environment and if the surface sustains unharmed after sterilization, it has the potential for mechano-bactericidal applications.

3.1.2 Nanotubes

Nanotube arrays, also known as nanodarts, on the Ti surface have been achieved by numerous methods. In this nanotopography, physical parameters including the tube diameter, the thickness of the nanotube layer, and the crystalline structure can influence the cellular responses [133,134,135]. Nanotube arrays are of attractive topographies due to their effectiveness to promote osteointegration [136,137]. Moreover, nanotube arrays of Ta on the Ti surface significantly increase the cell morphology and proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of stem cells [138,139]. Gulati et al. evaluated the influence of dual topography composed of microscale spherical particles and vertically aligned TiO2 nanotubes via 3D printers. This topography could obtain good enhancement in osteogenic gene expression [140].

Generally, when bacteria are adsorbed onto the surface of CNTs, it leads to tip deflection and retraction, which subsequently disturbs the physical membrane of the bacteria and results in cell death [141]. The bactericidal effectiveness of CNTs is different, e.g., short CNTs with an aspect ratio of 100 have higher efficiency than longer CNTs with an aspect ratio of 3,000 (Figure 19). This effect is attributed to the larger storage of elastic energy by short CNTs that can spontaneously pierce the membrane [142]. The mechano-bactericidal of CNTs was discovered when Elimelech et al. observed significant damage to the cell membrane of Escherichia coli (E. coli) as it directly contacts single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) [143]. SWCNTs with diameters between 1 and 5 nm have less effect on the direct piercing of a phospholipid bilayer and the free energy costs are regarded as the minimum energy for creating a pore in the bilayer [142]. However, hydrophobic SWCNTs demonstrated greater interaction with phospholipid tails and subsequently entrapped the CNT in the bilayer core in parallel orientation [144]. It should be noted that increasing the tension on the membrane facilitates the translocation of nano-objects through the membrane. Moreover, highly hydrophobic CNTs, as well as graphene, are able to create unstable pores in the membrane by rotation of lipid tails to carbon surface and constant extraction of lipids [145].

![Figure 19

Suggested penetration mechanism of hydrophobic ultrashort CNT (USCNT) by rupturing the lipid bilayer of the cell wall. (a) Dioleoylphosphatidyl-choline (DOPC)-capped USCNT interacts with the bacterial cell membrane by exchanging lipids. (b) USCNT becomes wrapped by lipids that results in dysfunctioning the membrane via the formation of pores. To obtain a general perspective of the process, some normal lipids of the bilayer were substituted by fluorescent lipids that can be detected by fluorescence microscopes [145]. Copyright 2018, ACS Publications.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_019.jpg)

Suggested penetration mechanism of hydrophobic ultrashort CNT (USCNT) by rupturing the lipid bilayer of the cell wall. (a) Dioleoylphosphatidyl-choline (DOPC)-capped USCNT interacts with the bacterial cell membrane by exchanging lipids. (b) USCNT becomes wrapped by lipids that results in dysfunctioning the membrane via the formation of pores. To obtain a general perspective of the process, some normal lipids of the bilayer were substituted by fluorescent lipids that can be detected by fluorescence microscopes [145]. Copyright 2018, ACS Publications.

3.1.3 Nanoblades

Graphene sheets, also known as nanoblades, with 10–15 nm edges, are of the second category of mechano-bactericidal nanotopographies that are 2D sheet-like nanomaterials consisting of a single layer of carbon atoms. In most nanoblades, it is essential to be perpendicularly oriented, but in nanosheets, the orientation of 37° demonstrated sufficient bactericidal activity [146,147,148]. The general antibacterial activity of graphene has been achieved through both physical and chemical states [149,150,151,152]. The physical interaction of graphene is shared with its derivations, namely graphene family nanomaterials (GFNs), which due to possessing certain parameters, their bactericidal activities can be predicted [153]. The addition of graphene nanosheets in chemical suspensions (Figure 20) provides sufficient antibacterial activity to rupture both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria by creating pores in their cell membrane and stimulating the alteration of osmotic pressure that resulted in cell death [147].

![Figure 20

Schematic illustration of the antibacterial activity of graphene oxide (GO)-based on mass spectrometry [157]. Copyright 2016, Scientific Reports.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_020.jpg)

Schematic illustration of the antibacterial activity of graphene oxide (GO)-based on mass spectrometry [157]. Copyright 2016, Scientific Reports.

Akhavan et al. evaluated the antibacterial activity of graphene oxide nanowalls (GONWs) on E. coli and S. aureus as Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively. They observed GONWs have stronger antibacterial activities against S. aureus by colony-forming unit (CFU) enumeration and quantification of cytoplasmic RNA leakage [153]. Similarly, Liu et al. confirmed that the bactericidal effect of GFNs against Gram-positive bacteria like E. coli was attributed to their sharp edges that can induce sufficient stress on the cell membrane (Figure 21) [154]. The mechanical disruption of GFNs is bonded to the degree of lipophilicity as the higher lipophilic one is able to facilitate the extraction of lipids from the cell membrane [155,156]. However, the progress of extermination of bacteria consists of complex processes including extraction of the lipids, formation of pores, alternation of osmotic pressure, and ultimately, cell death.

![Figure 21

Schematic illustrations, small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), and atomic force microscopy (AFM) characterization of GO composite to define its orientation in bulk and on the surface of specimens, respectively. According to the 3D illustration, the X-ray beam is located parallel to the film plane, and the AFM probe is placed above the surface. (a) Composite without GO nanosheets displayed minor scattering intensity in the 2D SAXS pattern and smooth surface in the 3D AFM image. (b) Composite with randomly oriented GO nanosheets displayed a notable increase to a broad, isotropic halo in the 2D SAXS pattern, and a sharp increase in roughness in the 3D AFM image. (c) Composite with vertically GO nanosheets displayed anisotropic equatorial scattering in the 2D SAXS pattern, and vertical alignment in the 3D AFM image. (d) Composite with planar GO nanosheets displayed anisotropicmeridional scattering in the 2D SAXS pattern and a smoother surface in the 3D AFM image [148]. Copyright 2017, PNAS.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_021.jpg)

Schematic illustrations, small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), and atomic force microscopy (AFM) characterization of GO composite to define its orientation in bulk and on the surface of specimens, respectively. According to the 3D illustration, the X-ray beam is located parallel to the film plane, and the AFM probe is placed above the surface. (a) Composite without GO nanosheets displayed minor scattering intensity in the 2D SAXS pattern and smooth surface in the 3D AFM image. (b) Composite with randomly oriented GO nanosheets displayed a notable increase to a broad, isotropic halo in the 2D SAXS pattern, and a sharp increase in roughness in the 3D AFM image. (c) Composite with vertically GO nanosheets displayed anisotropic equatorial scattering in the 2D SAXS pattern, and vertical alignment in the 3D AFM image. (d) Composite with planar GO nanosheets displayed anisotropicmeridional scattering in the 2D SAXS pattern and a smoother surface in the 3D AFM image [148]. Copyright 2017, PNAS.

3.1.4 Nanofibers

Of the nanotopographies with biological activity, nanofibers are a great choice for bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Nanofibers possess notable properties including high surface-to-volume ratio, well-retained topography, facile control of components, and the capacity to mimic the native ECM that can affect adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of stem cells [158,159,160]. Xu et al. fabricated a scaffold made of polylactic acid (PLA) and chitosan by the electrospinning technique. To generate a core–shell and island-like structure, they mixed electrospinning with automatic phase separation and crystallization. By culturing preosteoblast cells (MC3T3-E1), they observed a balanced hydrophilic and hydrophobic surface that successfully enhanced mineralization and cell growth, as well as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of MC3T3-E1 cells [161]. The utilization of simple techniques like electrospinning provided a remarkable potential for some bioactive materials or NPs to incorporate into the nanofibrous structured scaffold [162,163,164]. Yao et al. assessed the biological responses of gelatin nanofibrous scaffold with locally immobilized deferoxamine (DFO). It reduced the cytotoxicity of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Also, it has significantly promoted vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in human MSCs and BMP-2 expression in HUVECs [165].

3.1.5 Nanogrooves

Despite no bactericidal activity, nanogrooves are still an interesting option for their potential to promote the migration and proliferation of osteoblast cells [166]. An investigation on cellular affinity on micro- and nanogrooved surfaces displayed a significant reduction of up to 40% of cell-repelling capacity on microgrooved than nanogrooved surfaces [167]. Klymov et al. compared the smooth and grooved CaP-coated surface by culturing osteoblast-like MC3TC cells. They found that not only did nanogrooved surfaces promote the differentiation and mineralization processes but they also organized the morphological deposition of minerals [168].

3.1.6 Nanopits

Nanopits can be generated by PVD techniques with controlled nanopore size. Herein, a few pieces of research have been done to understand the physiobiological function of this nanopattern. Lavenus et al. evaluated the presence of human MSCs on the Ti surface with varied nanopore diameters. They observed that human MSCs exhibited a more branched cell morphology on nanopores with 30 nm pore size [169]. Similarly, Dalby et al. investigated the influence of spatial arrangement of nanopits on osteogenic differentiation on the poly(methyl-methacrylate) (PMMA) surface and cultured osteoprogenitor and MSCs on nanopits with diameter, depth, and center–center spacing of 120, 100, and 300 nm, respectively, as well as with the spatial arrangement of the square array, hexagonal array, disordered square arrays with 20 and 50 nm displacement from their square position (20-DSA and 50-DSA), and randomly positioned. Within the 21st day, observation demonstrated a significant increase in levels of osteopontin (OPN) and osteocalcin (OCN) on 50-DSA surfaces compared to other surfaces. With the same result for MSCs, it was spotted that MSCs have a greater affinity to DSA surfaces than other surfaces [124].

4 Multifunctional coatings

Modifying implants with NPs is a promising procedure to reduce the risk of failure. Implants, depending on the patient’s general condition, may need to be treated with different NPs to guarantee their success (Figure 22). Herein, we classified these NPs according to their nature as (i) metallic-based, (ii) ceramic-based, (iii) polymer-based, (iv) carbon-based, (v) protein-based, and (vi) drug-based coatings (Table 2). In the following sections, the subclasses and their biological applications in modifying the endosseous implant body are explained.

![Figure 22

Applications of nanoparticle coating in dentistry [22]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier™.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0037_fig_022.jpg)

Applications of nanoparticle coating in dentistry [22]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier™.

A summary of the aforementioned multifunctional coatings and their biogenic mechanisms

| Category | Subcategory | Biogenic and/or biocidal activities | Further advantages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis | Osteoinduction | Osteoconduction | Osteogenesis | Antibacterial | |||

| Metal | Tantalum (Ta5+) | × | × | ||||

| Titanium (Ti4+) | × | × | |||||

| Silicon (Si4+) | × | × | × | ||||

| Cerium (Ce4+) | × | × | Anti-inflammatory | ||||

| Gold (Au3+) | × | × | Antifungal and anticancer | ||||

| Iron (Fe3+) | × | Antibiofilm | |||||

| Copper (Cu2+) | × | × | × | Antifungal, antibiofilm, and antimicrobial | |||

| Zinc (Zn2+) | × | × | Antibiofilm | ||||

| Magnesium (Mg2+) | × | × | × | ||||

| Silver (Ag+) | × | Antimicrobial | |||||

| Selenium (Se2−) | × | Viruses and cancer cells | |||||

| Strontium (Sr2+) | × | Osteoclastogenesis | |||||

| Cobalt (Co2+) | × | ||||||

| Ceramic | Zirconium (Zr4+) | × | × | ||||

| Bioactive glass | × | × | × | × | |||

| CaP-Based materials | × | × | |||||

| Polymer | Chitosan | × | Antimicrobial, antiviral, antifungal, antitumor, immunoadjuvant, anti-thrombogenic, and anti-cholesteremic | ||||

| Peptides | × | Antimicrobial | |||||

| Carbon | Carbon family | × | Antibacterial, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticarcinogenic | ||||

| Protein | ECM proteins | × | × | × | |||

| Growth factors | × | × | |||||

| Drug | Organic drugs | × | × | ||||

4.1 Metallic-based coatings

4.1.1 Tantalum (Ta5+)

Tantalum (Ta) as both implant material and surface coating obtained considerable attention. Ta is a biocompatible metal with high corrosion resistance and favorable elastic modulus [32]. Ta is able to promote bone ingrowth and osteoconductivity, which are notable parameters as the secondary stability of implants [170]. Alves et al. deposited Ta-derived coatings on the Ti surface. They observed higher Ca:P ratio formation on the surface, which was attributed to the high oxygen content of the coating that increases the affinity for apatite adhesion [171]. Zhang et al. coated tantalum nitride (TaN) on the Ti surface. Results displayed higher antibacterial and corrosion resistance than individual Ti or TiN coatings [172]. Similarly, Zhang et al. coated Ta on the Ti surface to assess its biological activities. Ta-treated Ti could effectively kill Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) and Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) microbes. Also, it promoted osteointegration by activating the secretion of bone-forming proteins [173].

4.1.2 Titanium (Ti4+)

Coating titania (TiO2) NPs have various applications in medicine. Titania possesses unique photocatalytic properties by being exposed to visible or UV light irradiation [174]. TiO2 NPs possess excellent biogenic and biocide properties. The antibacterial mechanism of TiO2 is attributed to the formation of hydroxyl radicals by a photocatalytic reaction in an aqueous environment that targets the peptidoglycan cell membrane and interacts with polyunsaturated phospholipids, ultimately damaging the DNA and resulting in cell death [175]. Chidambaranathan et al. compared the antifungal activity of TiO2, ZrO2, and Al2O3 NPs coated on the Ti surface. After 24, 72 h, and 1-week time intervals, TiO2 demonstrated significant antibacterial activity against Candida albicans (C. albicans) bacteria than the other NPs [176].

On the other hand, the utilization of titania NPs can improve osteogenic activities like increasing the level of osteoblast cells on the surface, which leads to higher bone generation [177,178,179]. However, introducing TiO2 nanotubes attracted considerable attention. Primarily, TiO2 nanotubes were fabricated to increase the biogenic activity and enhance the osteointegration, but, as a biocide agent, they possess antimicrobial function by being accompanied by other antibiotics compounds like vancomycin, gentamicin, silica-gentamicin, gentamicin sulfate, BMP-2, and heparinized-Ti to eliminate Gram-positive bacteria like S. aureus [180,181,182,183,184,185,186].

4.1.3 Silicon (Si4+)

In nanotechnology, silicon (Si) mainly as silica (SiO2) NPs obtained a unique position. The utilization of these NPs enhances osteogenic differentiation of MSCs by increasing the osteoblasts’ adhesive response that consequently leads to higher osteointegration [187]. Moreover, SiO2 NPs depending on their size display different levels of hydrophilicity that can be exploited in drug-releasing applications [188]. Also, their products from degradation generate silicic acid [Si(OH)4], which is a supporting compound to generate connective tissues [185]. Csík et al. coated the CP-Ti surface with calcium silicate (Ca2O4Si) (CaSi) NPs by electrospray deposition (ESD) followed by thermal treatment at 750°C to examine its properties. They observed that CaSi NPs could effectively reduce the E. coli and S. aureus bacteria and promote human MSC activity [189]. Massa et al. assessed the antibacterial activity of SiO2 and the Ag nanocomposite (NSC/AgNPs) coated on Ti grade-5. They reported that not only did NSC/AgNPs kill the Gram-negative bacteria, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A. actinomycetemcomitans), but it also reduced the biofilm formation up to 70%, compared to the control group [190]. Catauro et al. developed the silica/quercetin hybrid as an antioxidant drug to scavenge the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) for dental implant applications. Quercetin is able to maintain the conditions of the general tissues against osteoporosis, pulmonary, and cardiovascular diseases, a particular spectrum of cancer, and premature aging. The results showed that quercetin successfully restricted the dehydrogenases’ activity [191].

4.1.4 Cerium (Ce4+)

Ceria (CeO2) is another NP with strong anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities. CeO2 NPs possess superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) enzymatic activities, as well as ROS-scavenging [26]. Li et al. evaluated the biological responses of CeO2 NPs coated on the Ti surface. The results showed that CeO2 NPs have no cytotoxicity to MC3T3-E1 cells and they can improve cell adhesion; also CeO2 coating maintained intracellular antioxidant defense system from H2O2-treated osteoblasts [192]. Qi et al. evaluated the incorporation of CeO2 and calcium silicate (Ca2O4Si). This composite displayed sufficient biocompatibility and antimicrobial activity against Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) [193]. Ceria with varied nanopatterns exhibited different levels of antibacterial activity. Li et al. compared the biocide activity of ceria NPs with different nanotopographies. They fabricated three nanopatterns including nanorod, nanocube, and nano-octahedron to select the one with less presence of Streptococcus sanguinis (S. sanguinis) bacteria. From in vitro and in vivo tests, they concluded that nano-octahedron had stronger anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities [194].

4.1.5 Gold (Au3+)

In terms of medical application, gold (Au) NPs have been frequently used due to their notable mechanical, chemical, and optical properties. Despite the high price of gold that may be restrictive, still, its utilization is inevitable. In dentistry, Au NPs demonstrated both biogenic and antibacterial activities but within the range of 40–50 nm, they are toxic. Therefore, their applications have been limited to 20–40 nm, which has been found to be the optimum cellular affinity [195]. Au NPs possess antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer functions [196,197]. The antifungal effects of Au NPs are highly dependent on their geometry [198]. Technically, the antifungal mechanism of Au NPs is based on the prevention of the H+-ATPase action or transmembrane H+ efflux action of Candida bacteria [30]. In general, the bactericidal effects of Au NPs are weaker than Ag on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [199,200,201]. The antibacterial mechanism of Au NPs is based on the prevention of ribosome subunit for t-RNA binding or changing the membrane potential and obstructs the ATP synthase, which disturbs both the biological system and results in cell death. Also, the interaction of Au NPs is free of ROS, which implies less toxicity on mammalian cells [202].

Regiel-futyra et al. coated chitosan-based Au composite NPs on Ti implant. This innovative composite displayed remarkable antibacterial function against antibiotic-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and S. aureus without any sign of cytotoxicity [203]. Wang et al. evaluated the modification of Au NPs with thiol or amine groups to decorate different densities of phenylboronic acid to fabricate Gram-selective antibacterial agents. They observed that modified Au NPs with amine- or thiol-tethered phenylboronic acids can effectively interact with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), as Gram-positive and Gram-negative compounds, respectively. Also, tunable ratios of thiol- and amine-tethered phenylboronic acids lead to different antibacterial activity [204]. Heo et al. assessed the effects of Au NPs on osteoblast differentiation. From in vitro and in vivo tests, they observed an increase in mRNA expression of osteogenic differentiation-specific genes and good bone formation on the Ti surface, respectively [205].

4.1.6 Iron (Fe3+)

Iron oxide (Fe x O x ) has proven its capability as a dental coating. Primarily, magnetite (Fe3O4) and maghemite (Fe2O3, y-Fe2O3) are the two most popular forms of iron oxide NPs without further cytotoxicity [206]. Most Fe x O x -derived NPs in biomedicine possess superparamagnetic properties [207]. For example, Fe2O3-superparamagnetic can improve osteoblast functions and help to eliminate the formed biofilms [208]. Generally, iron oxide NPs are able to interact with exopolymers that are generated by bacteria and are difficult to be eradicated by many antibiotics and immune cells as they are impenetrable [209].

Thukkaram et al. evaluated the efficacy of varying concentrations of iron oxide NPs against biofilm formation on different biomaterials. The optimal effectiveness was obtained at a concentration of 0.15 mg/mL against S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa bacteria [210]. In addition to biocide activity, iron oxide NPs possess magnetic properties that displayed higher stability and safety than other commonly used NPs. The cytotoxicity and inflammatory responses of these NPs are highly dependent on concentration rather than size, which could be exploited for designing new drug carriers [211].

4.1.7 Copper (Cu2+)

Copper oxide (Cu x O x ) NPs have unique physical, chemical, and biological properties that expand their medical applications. Similar to Ag, CuO-derived NPs displayed excellent antibacterial activity. However, the utilization of such metallic ions was restricted as their adverse effects were induced by remaining residues [212]. In addition to being antibacterial, Cu x O x NPs possess antifungal, antibiofilm, and antimicrobial activities [21]. The antibacterial mechanism of these NPs is based on passing through nano-mimic pores on the bacteria cell membrane and disturbing their biological activity by damaging the vital enzymes. This progress is highly dependent on the size, stability, and the concentration of NPs in the medium [213].

Likewise, antimicrobial activity is the result of the generation of ROS, which increases the oxidative stress of the cells [214]. Rosenbaum et al. coated CuO-derived NPs on the TiO2 surface and have not found a sign of S. aureus and E. coli bacteria [215,216]. Liu et al. included copper in the Ti alloy composition and observed significant activity against Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) and P. gingivalis [217]. Khan et al. evaluated the inhibitory effect of Cu x O x NPs within a size of 40 nm to prevent biofilm formation. In vitro results revealed that a concentration of 50 mg/mL can successfully prevent the development of oral bacteria and their polysaccharides [218].

4.1.8 Zinc (Zn2+)

Recently, zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs have become an attractive candidate as a biologically active ion that promote osteointegration and restrict the adhesion of bacteria [219,220]. The general bactericidal mechanism of ZnO NPs consists of a combination of (i) generation of H2O2 and (ii) formation of electrostatic interaction that accumulates ZnO NPs on the bacteria cell membrane, (iii) generation of ROS that leads to the release of Zn2+ ions, and ultimately, dysfunctioning the cell membrane [213]. This progress is applicable against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [213,221]. Hu et al. coated ZnO NPs on the TiO2 surface and restricted the growth of S. aureus and E. coli bacteria [222]. Similarly, Luo et al. fabricated ZnO@ZnS nanorod-array and optimized the release rate of Zn2+ ions that demonstrated higher bactericidal activity against S. aureus and E. coli bacteria [223]. Tabrez Khan et al. assessed the inhibitory function of ZnO NPs against biofilm-forming bacteria and colonizers. They observed that ZnO is able to provide significant bactericidal activity on different surfaces [218].

4.1.9 Magnesium (Mg2+)

Magnesium (Mg) is an attractive metal that can be fully adsorbed without acute toxicity. Physically, Mg possesses similar parameters to the human bone but, chemically, it has a limited range of applications that is mainly the result of its high rate of degradation. This high interaction of Mg2+ ion is attributed to the chloride ion (Cl−) available in ECM that forms the MgCl2 compound [224]. In general, the presence of Mg2+ ion promotes proliferation and differentiation of osteoblast cells [225]. Also, magnesium oxide (MgO) possesses good bactericidal activity with the mechanism of disturbing the bacteria cell membrane, which leads to leakage of intracellular contents and ultimately cell death [226,227]. To control the release rate of Mg2+ ions, simply compounding it with other materials cannot increase its corrosion resistance. For example, magnesium phosphates (MgPs) demonstrated higher in vivo adsorption than the calcium phosphate (CaP) compounds [228]. Kishen et al. compared the antimicrobial activity of MgO, sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), and chitosan NPs. They concluded that both MgO and chitosan NPs have comparable or superior bactericidal activity than NaOCl against E. faecalis bacteria [229].

4.1.10 Silver (Ag+)

Of the most practical antimicrobial coatings, AgNPs have been taking the lead. In retrospect, the high release of Ag+ ions from the implant surface would disturb the normal biological activities, but AgNPs at low doses displayed high biocompatibility and antibacterial activity with no sign of cytotoxicity, genotoxicity as well as side-effects [177,230]. The utilization of Ag+ ions was in the form of silver nitrate (AgNO3), silver sulfadiazine (C10H9AgN4O2S), silver chloride (AgCl), and pure metal that could exterminate a wide spectrum of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. However, AgNPs demonstrated higher antimicrobial efficacy than the aforementioned forms [231]. Ag at the nanoscale can facilitate the formation of holes onto the bacteria cell membrane and result in cell death [232]. This mechanism is attributed to the interaction of AgNPs with disulfide or sulfhydryl groups of enzymes [233]. In recent research works, the fabrication of Ag-based composite NPs has been widely seen. Choi et al. fabricated PDA and AgNPs on the Ti surface. They observed lower colonization of S. mutans and P. gingivalis microbes with a coating of these NPs than uncoated Ti [234,235]. Gunputh et al. coated AgNPs on the TiO2 nanotube surface with and without a top coating of HAp NPs to evaluate its biocide activity against S. aureus microbe. In vitro results revealed that AgNPs could effectively reduce the presence of the microbe. Also, the addition of HAp did not improve the biocidal function but it could diminish the release rate of Ag+ ions [236].

4.1.11 Selenium (Se2−)

Selenium (Se) NPs are unique elements with high biocidal potential against bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells. Se2− ions are a vital element in biological processes that control the elimination of ROS and modulation of a specific enzyme that lacks its increased susceptibility to viral infections [237,238]. Nanoscale Se exhibits a reduced risk of toxicity than its other forms like selenomethionine (SeMet) [239]. Therefore, the utilization of SeNPs as chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic coatings with both antibacterial and antiviral activity became attractive [240,241,242,243]. Moreover, SeNPs have proven to possess high bactericidal activity against S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) bacteria, which are the main cause of implant failure [244,245]. Srivastava et al. examined different concentrations of SeNPs to eliminate various bacteria. They found that at concentrations of 100, 100, 100, and 250 µg/mL, these NPs can kill 99% of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), S. aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes), and E. coli, respectively [246].

4.2 Ceramic-based coatings

4.2.1 Bioinert ceramics

4.2.1.1 Zirconium (Zr4+)

The utilization of zirconia (ZrO2) NPs in dentistry has been expanding since these NPs displayed great potential in improving the physicochemical properties of different compounds. Zirconia is a bioinert ceramic with low toxicity. Also, it cannot dissolve in water, which causes less adhesion of bacteria [247]. Zirconia-based NPs demonstrated antimicrobial activity against some microorganisms like E. faecalis [248]. In terms of biogenicity, ZrO2 NPs promote the attachment and proliferation of osteoblast and fibroblast cells and release nontoxic ions [249,250,251,252]. However, compared to Ti, ZrO2 NPs are at disadvantage to promote cell viability [253]. Huang et al. coated ZrO2 NPs on the Ti implant via the PS technique. After 2 weeks, the in vivo test showed a higher level of osteoblast cells that was attributed to the theory that adhesion of osteoblast cells can be promoted by higher free-energy surface [136,254].

4.2.2 Bioactive ceramics

4.2.2.1 Bioactive glass

Bioactive glasses (BGs) mainly refer to the mixture of silica, calcium oxide (CaO), sodium oxide (Na2O), and phosphorous pentoxide (P2O5) as silicate-based compounds [255,256]. BGs compared to other bioglasses (e.g., borate-based glass or phosphate-based glass), or ceramic glasses, have a higher potential to merge with the host tissue [257,258,259]. Moreover, manifold elements can be doped with BGs to modify their properties, for example, utilization of Na+, Mg2+, Al3+, Ti4+, or Ta5+ ions can reduce or increase the solubility as well as Ag+, strontium (Sr2+), or Zn2+ for modifying bactericidal activity, cellular viability, or anti-inflammatory responses of BGs, respectively [257,260,261]. Kalantari et al. evaluated the synthesis and osteogenic applications of monticellite for bone tissue engineering and compared its biological activity with HAp. They concluded that monticellite has a higher bone formation than HAp and it also provides minor antibacterial activity due to the presence of Si4+ ions in its components [262,263,264,265,266,267].

4.2.3 Biodegradable ceramics