Abstract

Establishing the correlation between the topography and the bactericidal performance is the key to improve the mechano-bactericidal activity. However, due to the complexity of the mechano-bactericidal mechanism, the correlation between density and bactericidal performance is still not clear. Based on this, a series of nanoblades (NBs) with various density but similar thickness and height were prepared on the chemically strengthened glass (CSG) substrate by a simple alkaline etching method. The mechano-bactericidal properties of NBs on CSG (NBs@CSG) surfaces exposed to Escherichia coli were evaluated. The results show that with the NB density increasing, the mechano-bactericidal performance of the surface increased first and then decreased. Besides, the bactericidal performance of NBs@CSG is not affected after four consecutive ultrasonic cleaning bactericidal experiments. This article can provide guidance for the design of the new generation of mechano-bactericidal surfaces. In addition, this technology is expected to be applied to the civil aviation cabin window lining.

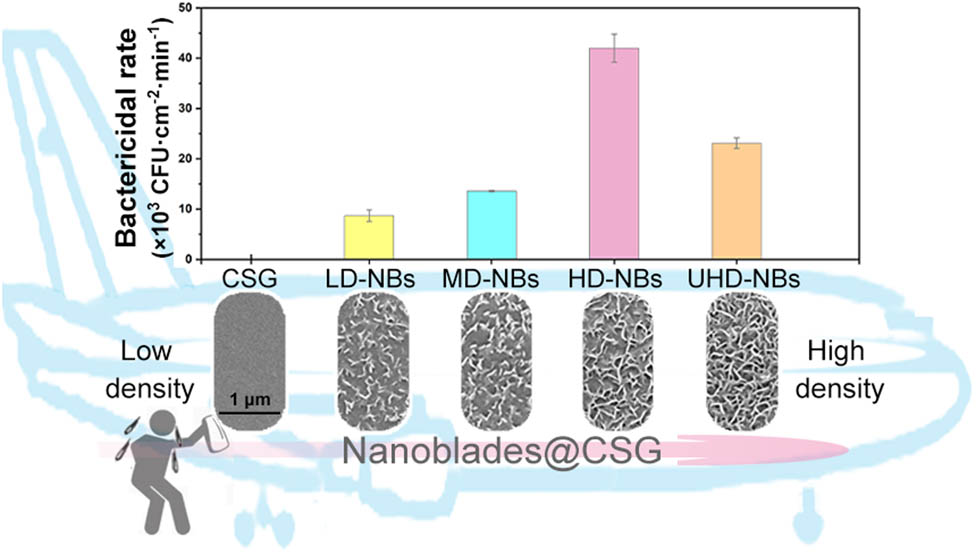

Graphical abstract

Topography and mechano-bactericidal performance of nanoblades (NBs) with different densities on the chemically strengthened glass for civil aircraft portholes. Low-density NBs, medium-density NBs, high-density NBs, and ultra-high density NBs.

1 Introduction

The convenient and fast air transportation has become an important way for the spread of infectious microorganisms, allowing pathogens to spread over long distances. So the demand for the prevention and control of pathogenic microorganisms in cabins has risen to a new height [1]. Traditional cabin disinfection is time-consuming and laborious [2], it is very necessary to find a new technology to prevent and control the microorganisms in cabins quickly and efficiently [3]. Previous studies have shown that mechano-bactericidal has the above advantages [4], and its bactericidal performance is better than other surface treatment methods [5,6] (for example, quaternary ammonium salt [7] and nano heavy metal [8] disintegrate cell membranes by the chemical activity, antibiotics inhibit the synthesis of proteins and nucleic acids [9]). However, due to the complexity of the mechano-bactericidal action [10], the relationship between the bactericidal performance and topography is still not clear [11,12]. The basic research on correlation is of great value to the application of mechano-bactericidal method such as reduce labor costs [13,14].

As a large class of typical pathogenic microorganism, bacteria are ubiquitous in the cabin environment. It can realize the initial adhesion [15], proliferation [15], bio-film formation [16], and final migration [17] on the surface in a short time [18]. Each of the processes can cause the spread of bacteria [19,20] that infect a person through skin contact or breathing [21]. Passenger cabins are densely populated and relatively airtight places. Although cabins are equipped with filtration systems, it still cannot effectively prevent the people on board from being infected [2,22]. In particular, the surface of high-frequency touched such as chemically strengthened glass (CSG) of cabin window is easily contaminated with bacteria. Inhibiting or preventing the bacteria from replicating on such surface is the key to disease prevention and control [23]. At present, chlorine-containing and quaternary ammonium salt disinfectants are generally used for cabin disinfection [24]. However, these chemical treatment methods may not be durable, and the residual chemicals may remain on the surface and cause potential toxicity and irritation [25]. The limitation of the chemical treatment methods has caused that a complete cleaning of the cabin must be implemented after each flight, which would cost a lot of manpower to disinfect the inner face and significantly extend waiting time for boarding [3].

Since Ivanova et al. first discovered the nanopillar structure based on “mechano-bactericidal activity” from the insect surface [26,27], this method is expected to become the next generation of surface sterilization treatment [28,29,30,31,32]. The mechano-bactericidal activity is realized by the interaction between the nanoscale array structure on the surface and the bacterial cell, which destroys the integrity of the cell. The bactericidal performance does not depend on the chemical properties of the surface, so it has the advantage of not producing secondary contamination and drug-resistant bacteria [12,33]. The mechanical bactericidal performance is affected by many surface characteristic factors, such as geometry [34,35], size [36,37], height [38], pillar elasticity [5], aspect-ratio [38,39,40], surface irregularity [30,33], and substrate chemistry [41]. The results show that higher aspect ratio and lower tip diameter can improve the surface mechano-bactericidal activity by imposing more stress on the cells. However, due to the diversity of topography parameters and the complexity of the biocide mechanism, there is no accurate conclusion about the effect of the density of the bactericidal nano units on the mechano-bactericidal performance [11]. In our previous studies, a series of bactericidal Zn–Al LDHs nanoblades (NBs) were grown, the results show that the low tip-width and high-density NBs (HD-NBs) have higher bactericidal activity [42]. We found that the mechano-bactericidal performance was mainly affected by the tip-width of the bactericidal unit, and the lower top diameter could exert stronger force on the bacterial cell wall and destroy the cell integrity faster. Therefore, it is an effective method to improve the bactericidal performance by reducing the tip diameter of bactericidal units [43]. In addition, the increase of stress caused by different heights can also improve the bactericidal performance [6].

In particular, the density of the mechano-bactericidal unit (nanopillar, NBs) not only affects the number of bactericidal units on the substrate surface, but also determines the number of bactericidal units that single bacteria cells can contact, which is also an important factor affecting the mechano-bactericidal activity. However, it is not clear that the bactericidal rate increases infinitely as the density of NBs increases. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the “optimal density” of bactericidal NBs.

At present, the preparation of bionic bactericidal nanostructures mainly includes hydrothermal method [4,44], nanoimprint lithography [45], reactive-ion beam etching [26,46], chemical vapor deposition [40], and liquid-phase exfoliation [47]. However, for amorphous substrates (such as glass), it is difficult to grow firmly bonded nanostructures directly [48,49]. Although the lattice mismatch between array units and the substrate can be reduced by preforming a seed layer as a buffer [50,51], the additional process will greatly reduce the efficiency. The etching method can solve the above problems well [52]. The alkaline etching method of building nanostructure on the surface of CSG substrate can be realized.

In this study, we investigated the correlation between the density of NBs and their bactericidal properties. Aiming at the above bactericidal problems, the CSG substrates that have a series of NBs with similar thickness, length, height, and significantly different densities were etched by alkaline etching method, named low-density NBs (LD-NBs), medium-density NBs (MD-NBs), HD-NBs, and ultra-high-density NBs (UHD-NBs). The topography parameters and bactericidal performance of each sample were analyzed by scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images and sticking membrane method separately. And then the influence of NB density on bactericidal activity was explored, which can provide effective guidance for the design of efficient mechano-bactericidal nanostructures on civil aircraft portholes. We expect to prepare a simple, effective, efficient, and long-term bactericidal NB structure on the CSG substrate, to realize the saving of manual disinfection labor, which is expected to be applied in the civil aviation field.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

CSG sheet 3 cm × 4 cm × 0.15 mm, medical disinfectant alcohol, pure ethanol, and potassium hydroxide (KOH) were purchased from Chang Zheng Chemicals Co., Ltd (Chengdu). All the chemicals used in this study were analytically pure. The etching solution was prepared with deionized water. The chemical composition of the original CSG surface is shown in Table 1.

The composition of CSG

| SiO2 | Na2O | K2O | CaO | Al2O3 | MgO | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight percentage (%) | 70.32 | 15.86 | 2.12 | 3.85 | 4.37 | 3.28 | 0.20 |

2.2 Preparation of NBs by KOH etching

The cleaned CSG sheet was placed in 50 mL etching solution in a 100 mL teflon container, which was sealed by the stainless-steel reactor at 95°C. The 0.1 mol L−1 KOH was utilized as etching solution. To prepare a series of NBs, the etching time was controlled in 1, 2, 3, and 4 h. After etching, the products were cooled at room temperature, then the etched-CSG was cleaned by ionized water and dried in room temperature. Then each sample was cut to the appropriate size before use. The optical pictures of each etched-CSG sample are shown in Figure 1. There is no obvious difference in the appearance of the etched samples.

Optical pictures of CSG and NBs@CSG sheets: (a) CSG original sample; etched-CSG after etching for different time: (b) 1 h, (c) 2 h, (d) 3 h, and (e) 4 h.

2.3 Characterization

To characterize the surface topographies of CSG and etched CSG, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JEOL, JSM-7001F) was used at a voltage of 10 kV. Due to the poor conductivity of each sample, it is necessary to spray gold (10 mA, 70 s) before FE-SEM observation to ensure the observation effect. The Image J software was used to calculate the NB density. Steps are as follows: five 1 µm2 areas were randomly selected in the SEM image of a sample. The topography parameters of the NBs in each area were counted respectively, and the average density was finally calculated. The composition of the samples was measured by energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS, Horiba 7021-H).

2.4 Bactericidal performance of NBs@CSG

To evaluate the bactericidal properties of the NBs@CSG against bacteria, the sticking membrane method referring to the Japanese Industrial Standard (JIS Z 2801) was used [53]. Each CSG sheet was assembled into a test device with a cavity of 1 cm × 1 cm × 0.12 cm, and the test surface constitute the under inner surface of the cavity. Before the bactericidal experiment, the whole device was immersed into disinfection alcohol for 1 min, and then transferred to the effective area of the clean bench (Shanghai Shu Li Instruments Co., Ltd, SW-CJ-1F) for drying. The Escherichia coli strain (E. coli ATCC 25922) was selected as the model strain in the experiment. The E. coli strain was successively activated and multiplied in a nutrient broth medium at 38°C for 3 h, and then the bacterial suspension was diluted to the standard concentration (5.0 × 106 CFU mL−1) by sterilized normal saline. About 100 µL E. coli standard bacterial suspensions were carefully dropped into the cave of the test device and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. To avoid the influence of bacteria movement on the bactericidal properties of the surface [54], all droplets were added at a distance of 0.5 cm from the CSG sample. To count the number of live bacteria on the surface, each sample was thoroughly washed with sterilized physiological saline (10 mL). After the eluent was subsequently diluted and cultivated, the bactericidal rate of CFU per cm2 was calculated. Each sample is repeated five times.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Fabrication and topography characterization of NBs@CSG

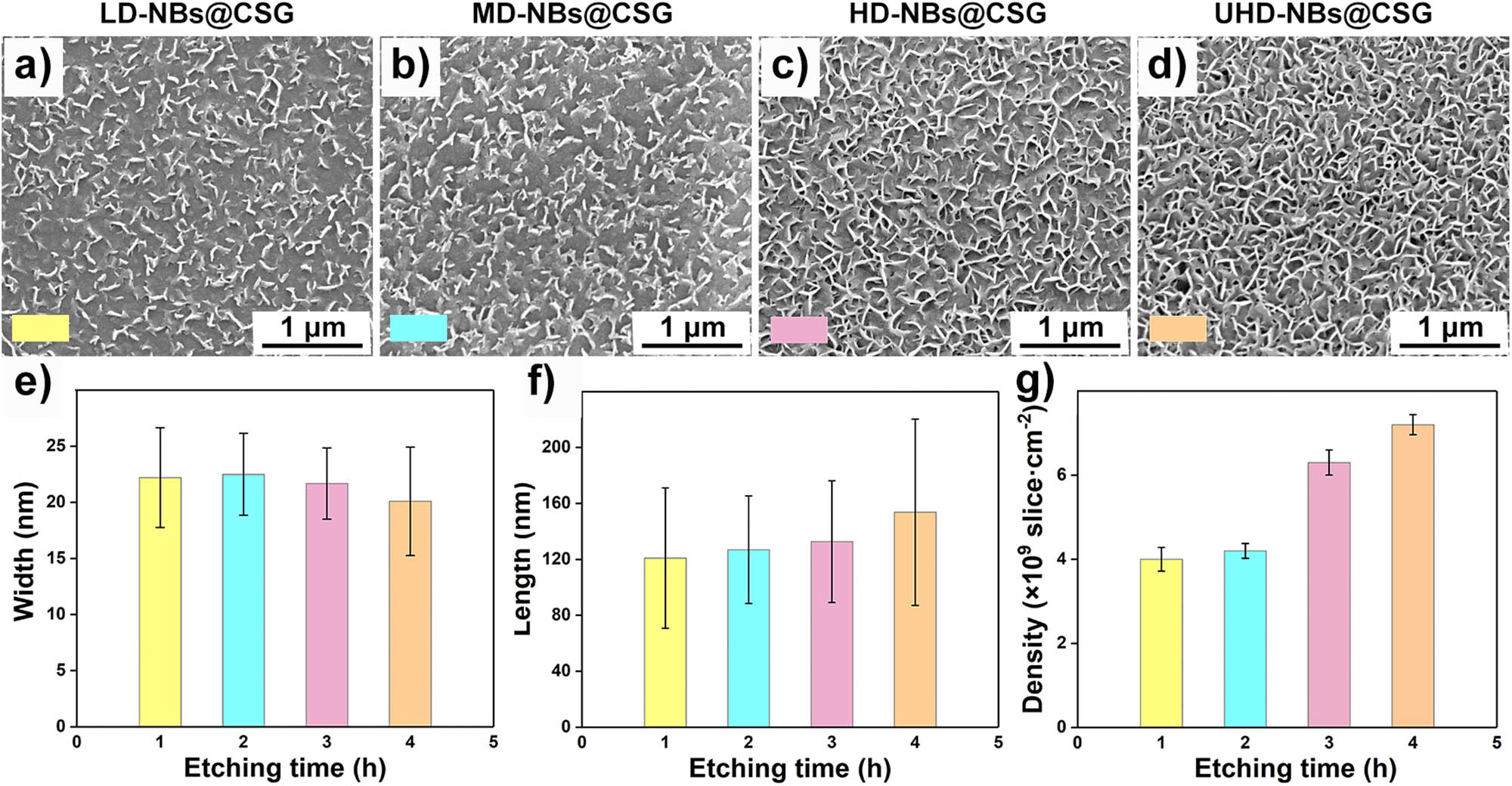

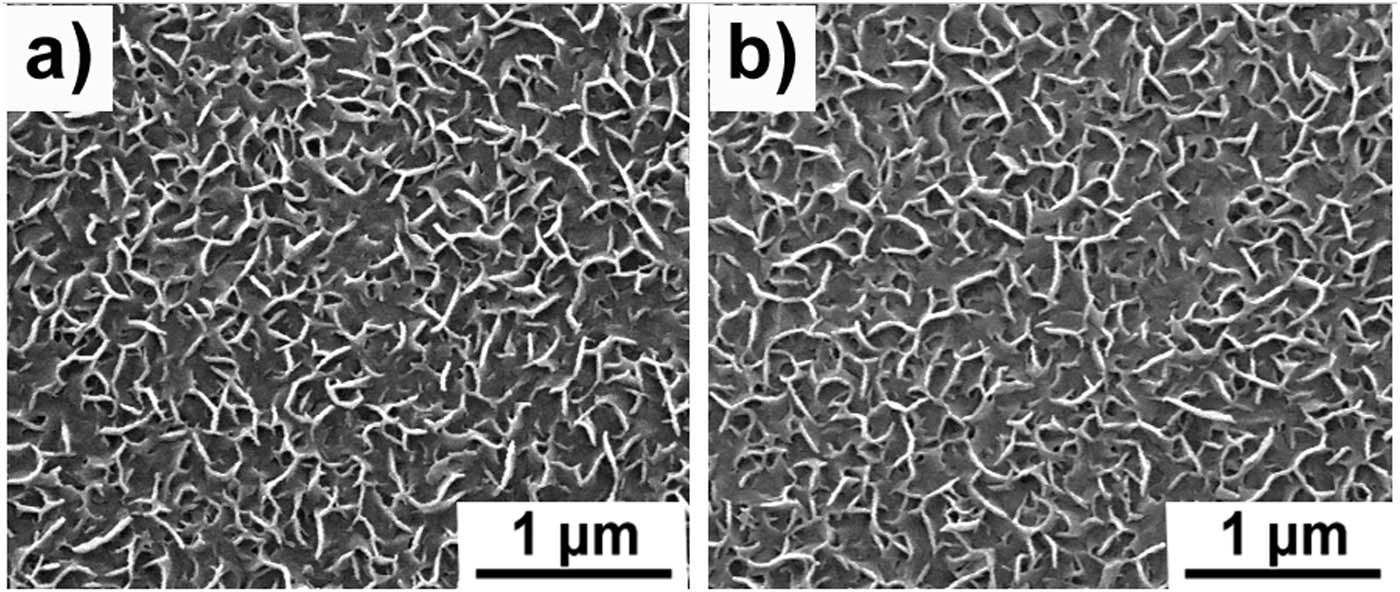

To obtain etched surfaces with different topographies, the etching time was controlled, and a series of blade-like nanostructures were prepared, which were named as low-density NBs@CSG, medium-density NBs@CSG, high-density NBs@CSG, and ultra-high-density NBs@CSG (LD-NBs@CSG, MD-NBs@CSG, HD-NBs@CSG and UHD-NBs@CSG; Figure 2). After 1 h of etching, evenly distributed NBs were formed on the CSG surface, and a large number of NBs existed in the form of a single individual (Figure 2a). The NBs fused with each other and gradually formed a blade network structure with the increase of etching time (Figure 2b–d). The statistical results of blade width, length, and density according to SEM are shown in Figure 2e–g. With the increase of etching time to 4 h, the width of the NBs decreases slightly (from 22.21 ± 4.44 to 20.10 ± 4.83 nm), and the blade length increases from 120.95 ± 50.23 to 153.73 ± 66.58 nm. In this process, the blade density increases from 4.0 × 109 to 7.3 × 109 slice cm−2.

Surface topography and topography statistics of NBs@CSG. SEM images of etched-CSG after etching for different time: (a) 1 h, (b) 2 h, (c) 3 h, and (d) 4 h. Topographic parameters of the NBs: (e) width, (f) length, and (g) density.

3.2 The etching mechanism of CSG

To explore and study the etching process of CSG, the composition of the CSG surface was analyzed. CSG is divided into network formers, network modifiers, and intermediates according to cation types. Network formers are usually composed of [SiO4]4− units, which usually form a three-dimensional network structure through the interconnection of bridging oxygen. Network modifiers, such as K and Na ions, can interrupt the network and lead to non-bridge oxygen that adjust glass properties. Network intermediates, mainly composed of double-acting cations (Mg, Al), can act as network formers or network modifiers according to environmental changes [55]. EDS is used to analyze various compositions of each surface, and the atomic ratio of network modifiers (Na, K), intermediates (Al, Mg), and network formers (Si) with time is calculated (Figure 3). The results show that the content of Na and K on the surface of CSG decreases rapidly in the condition of thermal-alkali solution, indicating that the network modifiers formed by CSG are dissolved first. Attribute to the cations in this region have a very low binding energy with non-bridge oxygen (Na–O: 94 kJ mol−1, K–O: 54 kJ mol−1), can exchange with hydrogen ions in the water and enter the solution [56]. After Na and K dissolved, the exposed area of network modifiers is more likely to react with water to generate silanol groups, which will further undergo dehydration cross-linking and local network reconstruction to form a single NB (Figure 3a). Then the pores are generated in the network modifier region, allowing water molecules to enter the surface for further etching. Therefore, the growth rate of NBs near the network modifier region is slightly faster. As the reaction continues, the Si–O (bond energy 443 kJ mol−1) in network formers area slowly depolymerize and form to Si–OH (equation (1)) and further form into soluble

![Figure 3

Atomic ratio [cationic/Si] changes with etching time of CSG.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0008/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0008_fig_003.jpg)

Atomic ratio [cationic/Si] changes with etching time of CSG.

3.3 Density-dependent mechanical bactericidal activity of NBs@CSG

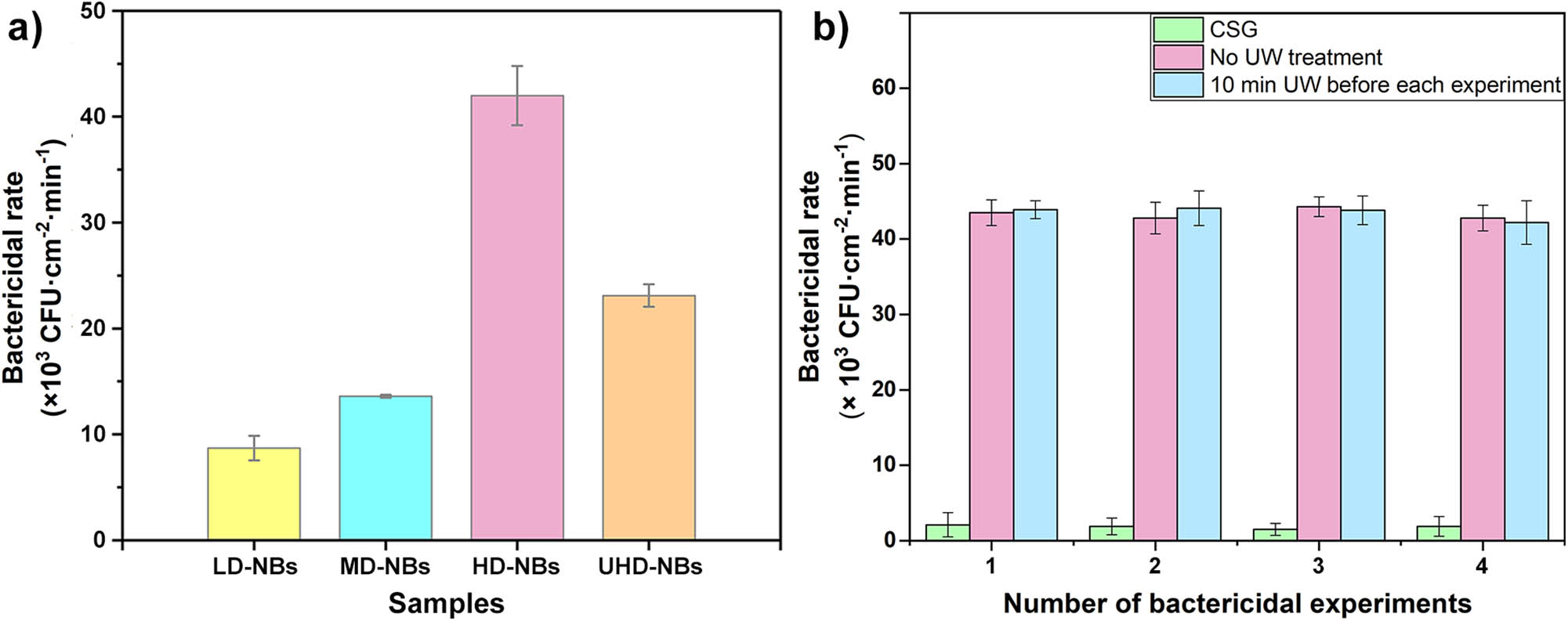

The statistical results of bactericidal experiment were shown in Figure 4a. All of the NB surfaces show a certain bactericidal activities after 10 min of incubation. And from the LD-NBs to UHD-NBs, the surface bactericidal performance was firstly increased and then decreased. Previous studies have shown that the larger the length of the bactericidal unit tip, the smaller the stress on the bactericidal cell and the poorer the mechano-bactericidal performance. Therefore, the continuous increase in the bactericidal performance of LD-NB to HD-NB samples was mainly caused by the increase of blade density. The increase of blade density can increase the number of the sterilization unit that contact a single cell, resulting in an increased ability to damage the bacterial membrane. The E. coli cells (0.5 × 1–3 µm) are larger in size than NBs. However, the positive correlate promotion effect works only within a certain range. As the blade density further increased, the surface bactericidal activity decreased obviously (Figure 4a). The excessively high blade density may reduce the stress of a single blade on cells due to stress averaging. In addition, the excessively high blade density will also affect the effective sinking of bacterial cells, and reduce the force on cells. Notably, the CSG-NB surface had a lower bactericidal performance than the nanopillar of the same density (black silicon: 4.5 × 105 CFU min−1 cm−2, dragonfly wing: 4.5 × 105 CFU min−1 cm−2; cicada wing: 2.0 × 105 CFU min−1 cm−2) [26], which has a lower tip diameter and can cause higher stress on the bacterial cell [6]. It is worth noting that compared with LD-NBs@CSG, ZnAl lamellar bimetallic hydroxide HD-NBs (ZnAl LDH HD-NBs) prepared in our previous study has similar density and higher width and length (width: 29.32 ± 5.74 nm, length: 880.00 ± 223.62 nm, density: 4.4 × 109 slice cm−2), but the bactericidal rate of ZnAl LDH HD-NBs is higher than that of LD-NBs@CSG (8.69 ± 1.16 × 103 CFU cm−2 min−1) [42]. This may be attributed to the low height of LD-NBs@CSG, which could not provide enough altitude difference to provide enough mechanical force on bacterial cells.

The mechanical bactericidal activity of NBs@CSG. (a) The bactericidal rate against E. coli of NBs@CSG with different density. (b) The long-term stability of HD-NBs@CSG bactericidal effect. The 1–4 times consecutive bactericidal experiment statistical results of E. coli on HD-NBs@CSG with or without ultrasonic wave treatment. Incubation time: 10 min. The data are expressed as mean ± SD of three replicates.

To evaluate the long-term bactericidal efficacy of HD-NBs@CSG, a continuous bactericidal experiment was carried out. A complete experiment process was carried out for each test. The results showed that after four times bactericidal experiments, the surface maintained good bactericidal activity and did not significantly decrease (Figure 4), shows a good long-term bactericidal performance. At the same time, the effective combination of NBs and substrate directly affects the surface bactericidal activity, so the ultrasonic pretreatment-bactericidal experimental group is carried out to evaluate the reliability of the performance of the HD-NBs@CSG. An ultrasonic wave cleaning process (100 W, 5 min) was added before each bactericidal experiment. As the result shows in Figure 4b, the bactericidal activity of ultrasonic pretreatment group and the untreated group was not significantly different in four times continuous bactericidal experiments, which shows the bactericidal performance stability. It is well known that the effective combination of nanostructure and substrate directly determines the performance [60]. This is because the NBs combine well with the CSG substrate and the ultrasonic treatment does not affect the nanostructure of the surface (Figure 5).

Binding of NBs on CSG substrate surface. The surface topography after ultrasonic cleaning-bactericidal experiment: (a) 2 times and (b) 4 times. The ultrasonic cleaning process: 5 min.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, in this study a series of NB structures with gradient densities, similar thickness and height were constructed on the surface of CSG by alkali etching by controlling etching time. The etched NBs@CSG has a mechanical bactericidal activity, and the surface bactericidal activity can be improved by increasing the blade density in a certain range. The NB has an optimal density, which can achieve the highest mechano-bactericidal performance. Therefore, it is unrealistic to increase the efficiency of mechanical sterilization by increasing the density of bactericidal units. Although our experiments clarified the relationship between CSG–NBs density and mechano-bactericidal performance, the interaction mechanism between other nano units (such as nanopillar and nanocone) and bacteria may be different, so the correlation between these surface nano unit densities and bactericidal performance needs to be further studied. In addition, to solve the long-term application, the good combination between the CSG substrate and the blade was demonstrated by the ultrasonic treatment of HD-NBs sample. Thus, this study provides a simple method and idea for the preparation of fast and efficient bactericidal nanostructures on the surface of CSG in civil aircraft cabin to realize the saving of manual disinfection labor, which is conducive to the further practical application of mechanical bactericidal technology.

-

Funding information: This study was financially supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Sichuan Province (No. 2017RZ0032).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Ivanoska-Dacikj A, Stachewicz U. Smart textiles and wearable technologies – opportunities offered in the fight against pandemics in relation to current COVID-19 state. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2020;59(1):487–505.10.1515/rams-2020-0048Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Spengler JD, Wilson DG. Air quality in aircraft. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part E J Process Mech Eng. 2003;217(4):323–36.10.1243/095440803322611688Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Schultz M, Evler J, Asadi E, Preis H, Fricke H, Wu CL. Future aircraft turnaround operations considering post-pandemic requirements. J Air Transp Manag. 2020;89:101886.10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101886Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Yi G, Yuan Y, Li X, Zhang Y. ZnO nanopillar coated surfaces with substrate-dependent superbactericidal property. Small. 2018;14(14):e1703159.10.1002/smll.201703159Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Ivanova EP, Linklater DP, Werner M, Baulin VA, Xu X, Vrancken N, et al. The multi-faceted mechano-bactericidal mechanism of nanostructured surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:12598–605.10.1073/pnas.1916680117Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Xie Y, Qu X, Li J, Li D, Wei W, Hui D, et al. Ultrafast physical bacterial inactivation and photocatalytic self-cleaning of ZnO nanoarrays for rapid and sustainable bactericidal applications. Sci Total Environ. 2020;738:139714.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139714Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] He W, Zhang Y, Li J, Gao Y, Luo F, Tan H, et al. A novel surface structure consisting of contact-active antibacterial upper-layer and antifouling sub-layer derived from gemini quaternary ammonium salt polyurethanes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:e32140.10.1038/srep32140Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Gholamrezazadeh M, Shakibaie MR, Monirzadeh F, Masoumi S, Hashemizadeh Z. Effect of nano-silver, nano-copper, deconex and benzalkonium chloride on biofilm formation and expression of transcription regulatory quorum sensing gene (rh1r) in drug-resistance Pseudomonas aeruginosa burn isolates. Burns. 2018;44(3):700–8.10.1016/j.burns.2017.10.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Jutkina J, Marathe NP, Flach CF, Larsson DGJ. Antibiotics and common antibacterial biocides stimulate horizontal transfer of resistance at low concentrations. Sci Total Environ. 2018;616–617:172–8.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.312Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Lin N, Berton P, Moraes C, Rogers RD, Tufenkji N. Nanodarts, nanoblades, and nanospikes: mechano-bactericidal nanostructures and where to find them. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;252:55–68.10.1016/j.cis.2017.12.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Elbourne A, Crawford RJ, Ivanova EP. Nano-structured antimicrobial surfaces: from nature to synthetic analogues. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;508:603–16.10.1016/j.jcis.2017.07.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Hasan J, Chatterjee K. Recent advances in engineering topography mediated antibacterial surfaces. Nanoscale. 2015;7(38):15568–75.10.1039/C5NR04156BSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Green DW, Lee KK, Watson JA, Kim HY, Yoon KS, Kim EJ, et al. High quality bioreplication of intricate nanostructures from a fragile gecko skin surface with bactericidal properties. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41023.10.1038/srep41023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Cheeseman S, Elbourne A, Kariuki R, Ramarao AV, Zavabeti A, Syed N, et al. Broad-spectrum treatment of bacterial biofilms using magneto-responsive liquid metal particles. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:10776–87.10.1039/D0TB01655ASuche in Google Scholar

[15] Kargar M, Wang J, Nain AS, Behkam B. Controlling bacterial adhesion to surfaces using topographical cues: a study of the interaction of pseudomonas aeruginosa with nanofiber-textured surfaces. Soft Matter. 2012;8(40):10254–9.10.1039/c2sm26368hSuche in Google Scholar

[16] Cheng G, Zhang Z, Chen S, Bryers JD, Jiang S. Inhibition of bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation on zwitterionic surfaces. Biomaterials. 2007;28(29):4192–9.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Abee T, Kovács ÁT, Kuipers OP, van der Veen S. Biofilm formation and dispersal in gram-positive bacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22(2):172–9.10.1016/j.copbio.2010.10.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Demssie Dejen K, Amare Zereffa E, Ananda HC, Murthy AM. Synthesis of ZnO and ZnO/PVA nanocomposite using aqueous Moringa oleifeira leaf extract template: antibacterial and electrochemical activities. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2020;59(1):464–76.10.1515/rams-2020-0021Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Meng J, Zhang P, Wang S. Recent progress in biointerfaces with controlled bacterial adhesion by using chemical and physical methods. Chem – An Asian J. 2014;9(8):2004–16.10.1002/asia.201402200Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Kaplan JB. Biofilm dispersal: mechanisms, clinical implications, and potential therapeutic uses. J Dent Res. 2010;89(3):205–18.10.1177/0022034509359403Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Guilhen C, Forestier C, Balestrino D. Biofilm dispersal: multiple elaborate strategies for dissemination of bacteria with unique properties. Mol Microbiol. 2017;105(2):188–210.10.1111/mmi.13698Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Bielecki M, Patel D, Hinkelbein J, Komorowski M, Kester J, Ebrahim S, et al. Air travel and covid-19 prevention in the pandemic and peri-pandemic period: a narrative review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;39:101915.10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101915Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Liu M, Wang L, Tong X, Dai J, Li G, Zhang P, et al. Antibacterial polymer nanofiber-coated and high elastin protein-expressing bmscs incorporated polypropylene mesh for accelerating healing of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9:670–82.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0052Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Miura T, Shibata T. Antiviral effect of chlorine dioxide against influenza virus and its application for infection control. Open Antimicrob Agents J. 2010;2:71–8.10.2174/1876518101002020071Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Ambach F. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of silver, gold and silver-gold alloy nanoparticles phytosynthesized using extract of Opuntia ficus-indica. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2019;58(1):313–26.10.1515/rams-2019-0039Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Ivanova EP, Hasan J, Webb HK, Gervinskas G, Juodkazis S, Truong VK, et al. Bactericidal activity of black silicon. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2838.10.1038/ncomms3838Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Ivanova EP, Hasan J, Webb HK, Truong VK, Watson GS, Watson JA, et al. Natural bactericidal surfaces: mechanical rupture of pseudomonas aeruginosa cells by cicada wings. Small. 2012;8(16):2489–94.10.1002/smll.201200528Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Singh J, Jadhav S, Avasthi S, Sen P. Designing photocatalytic nanostructured antibacterial surfaces: why is black silica better than black silicon? ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(18):20202–13.10.1021/acsami.0c02854Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Li X. Bactericidal mechanism of nanopatterned surfaces. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;18(2):1311–6.10.1039/C5CP05646BSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Bandara CD, Singh S, Afara IO, Wolff A, Tesfamichael T, Ostrikov K, et al. Bactericidal effects of natural nanotopography of dragonfly wing on Escherichia Coli. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(8):6746–60.10.1021/acsami.6b13666Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Linklater DP, Juodkazis S, Rubanov S, Ivanova EP. Comment on “bactericidal effects of natural nanotopography of dragonfly wing on Escherichia coli. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(35):29387–93.10.1021/acsami.7b05707Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Linklater DP, Juodkazis S, Ivanova EP. Nanofabrication of mechano-bactericidal surfaces. Nanoscale. 2017;9:16564–85.10.1039/C7NR05881KSuche in Google Scholar

[33] Elbourne A, Coyle VE, Truong VK, Sabri YM, Kandjani AE, Bhargava SK, et al. Multi-directional electrodeposited gold nanospikes for antibacterial surface applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2019;1(1):203–12.10.1039/C8NA00124CSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Nowlin K, Boseman A, Covell A, LaJeunesse D. Adhesion-dependent rupturing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on biological antimicrobial nanostructured surfaces. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(102):20140999.10.1098/rsif.2014.0999Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Bhadra CM, Truong VK, Pham VT, Al Kobaisi M, Seniutinas G, Wang JY, et al. Antibacterial titanium nano-patterned arrays inspired by dragonfly wings. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16817.10.1038/srep16817Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Pogodin S, Hasan J, Baulin VA, Webb HK, Truong VK, Phong Nguyen TH, et al. Biophysical model of bacterial cell interactions with nanopatterned cicada wing surfaces. Biophys J. 2013;104(4):835–40.10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.046Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Truong VK, Geeganagamage NM, Baulin VA, Vongsvivut J, Tobin MJ, Luque P, et al. The susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus CIP 65.8 and pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9721 cells to the bactericidal action of nanostructured Calopteryx haemorrhoidalis damselfly wing surfaces. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:4683–90.10.1007/s00253-017-8205-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Mainwaring DE, Nguyen SH, Webb H, Jakubov T, Tobin M, Lamb RN, et al. The nature of inherent bactericidal activity: insights from the nanotopology of three species of dragonfly. Nanoscale. 2016;8:6527–34.10.1039/C5NR08542JSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Watson GS, Green DW, Schwarzkopf L, Li X, Cribb BW, Myhra S, et al. A gecko skin micro/nano structure – a low adhesion, superhydrophobic, anti-wetting, self-cleaning, biocompatible, antibacterial surface. Acta Biomater. 2015;21:109–22.10.1016/j.actbio.2015.03.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Linklater DP, De Volder M, Baulin VA, Werner M, Jessl S, Golozar M, et al. High aspect ratio nanostructures kill bacteria via storage and release of mechanical energy. ACS Nano. 2018;12(7):6657–67.10.1021/acsnano.8b01665Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Sengstock C, Lopian M, Motemani Y, Borgmann A, Khare C, Buenconsejo PJ, et al. Structure-related antibacterial activity of a titanium nanostructured surface fabricated by glancing angle sputter deposition. Nanotechnology. 2014;25(19):195101.10.1088/0957-4484/25/19/195101Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Xie Y, Li J, Bu D, Xie X, He X, Wang L, et al. Nepenthes -inspired multifunctional nanoblades with mechanical bactericidal, self-cleaning and insect anti-adhesive characteristics. RSC Adv. 2019;9(48):27904–10.10.1039/C9RA05198HSuche in Google Scholar

[43] Watson GS, Green DW, Watson JA, Zhou Z, Li X, Cheung GSP, et al. A simple model for binding and rupture of bacterial cells on nanopillar surfaces. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2019;6(10):1801646.10.1002/admi.201801646Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Diu T, Faruqui N, Sjöström T, Lamarre B, Jenkinson HF, Su B, et al. Cicada-inspired cell-instructive nanopatterned arrays. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7122.10.1038/srep07122Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Dickson MN, Liang EI, Rodriguez LA, Vollereaux N, Yee AF. Nanopatterned polymer surfaces with bactericidal properties. Biointerphases. 2015;10(2):e021010.10.1116/1.4922157Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Fisher LE, Yang Y, Yuen M-F, Zhang W, Nobbs AH, Su B. Bactericidal activity of biomimetic diamond nanocone surfaces. Biointerphases. 2016;11(1):e011014.10.1116/1.4944062Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Pham VT, Truong VK, Quinn MD, Notley SM, Guo Y, Baulin VA, et al. Graphene induces formation of pores that kill spherical and rod-shaped bacteria. ACS Nano. 2015;9(8):8458–67.10.1021/acsnano.5b03368Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Athauda TJ, Hari P, Ozer RR. Tuning physical and optical properties of ZnO nanowire arrays grown on cotton fibers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(13):6237–46.10.1021/am401229aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Wagata H, Ohashi N, Taniguchi T, Subramani AK, Katsumata K, Okada K, et al. Single-step fabrication of ZnO rod arrays on a nonseeded glass substrate by a spin-spray technique at 90°C. Cryst Growth Des. 2010;10(8):3502–7.10.1021/cg100386cSuche in Google Scholar

[50] Li C, Fang G, Li J, Ai L, Dong B, Zhao X. Effect of seed layer on structural properties of ZnO nanorod arrays grown by vapor-phase transport. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112(4):990–5.10.1021/jp077133sSuche in Google Scholar

[51] Wu Q, Miao WS, Zhang Y, DuGao D, Hui HJ. Mechanical properties of nanomaterials: a review. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9:259–73.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0021Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Piret N, Santoro R, Dogot L, Barthélemy B, Peyroux E, Proost J. Influence of glass composition on the kinetics of glass etching and frosting in concentrated HF solutions. J Non Cryst Solids. 2018;499:208–16.10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2018.07.030Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Xie Y, Wei W, Meng F, Qu X, Li J, Wang L, et al. Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of zno nanoarrays with gradient morphologies. Nanotechnol Rev. 2019;8(1):315–26.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0030Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Jindai K, Nakade K, Masuda K, Sagawa T, Kojima H, Shimizu T, et al. Adhesion and bactericidal properties of nanostructured surfaces dependent on bacterial motility. RSC Adv. 2020;10:5673–80.10.1039/C9RA08282DSuche in Google Scholar

[55] Hench LL, Clark DE. Physical chemistry of glass surfaces. J Non Cryst Solids. 1978;28(1):83–105.10.1016/0022-3093(78)90077-7Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Shi C. Corrosion of glasses and expansion mechanism of concrete containing waste glasses as aggregates. J Mater Civ Eng. 2009;21(10):529.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2009)21:10(529)Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Bunker BC. Molecular mechanisms for corrosion of silica and silicate glasses. J Non Cryst Solids. 1994;179:300–8.10.1016/0022-3093(94)90708-0Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Tournié A, Ricciardi P, Colomban P. Glass corrosion mechanisms: a multiscale analysis. Solid State Ionics. 2008;179(38):2142–54.10.1016/j.ssi.2008.07.019Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Xiong J, Das SN, Kar JP, Choi JH, Myoung JM. A multifunctional nanoporous layer created on glass through a simple alkali corrosion process. J Mater Chem. 2010;20(45):10246–52.10.1039/c0jm01695kSuche in Google Scholar

[60] Vlassov S, Oras S, Antsov M, Sosnin I, Polyakov B, Shutka A, et al. Adhesion and mechanical properties of PDMS-based materials probed with AFM: a review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2018;56(1):62–78.10.1515/rams-2018-0038Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Yuan Xie et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy