Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

-

M. G. Eloffy

, Dina M. El-Sherif

, Mohamed Abouzid

Abstract

Since the beginning of the third Millennium, specifically during the last 18 years, three outbreaks of diseases have been recorded caused by coronaviruses (CoVs). The latest outbreak of these diseases was Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has been declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a pandemic. For this reason, current efforts of the environmental, epidemiology scientists, engineers, and water sector professionals are ongoing to detect CoV in environmental components, especially water, and assess the relative risk of exposure to these systems and any measures needed to protect the public health, workers, and public, in general. This review presents a brief overview of CoV in water, wastewater, and surface water based on a literature search providing different solutions to keep water protected from CoV. Membrane techniques are very attractive solutions for virus elimination in water. In addition, another essential solution is nanotechnology and its applications in the detection and protection of human and water systems.

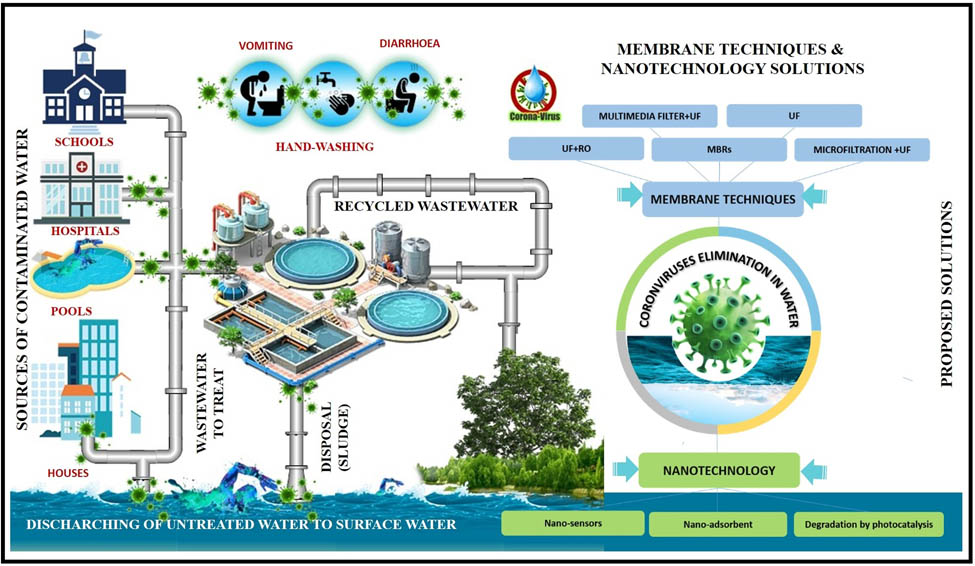

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- 2019-NCoV

-

the 2019 novel coronavirus

- 2PY

-

1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide

- 4PY

-

1-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide

- 8-iso-PGF2α

-

8-iso-prostaglandin F2α

- 8-OHdG

-

8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine

- AdV

-

adenovirus

- AiV

-

aichi virus

- AOPs

-

advanced oxidation processes

- AstV

-

astrovirus

- CNTs

-

carbon nanotubes

- CLV-BR

-

circo-like virus-Brazil

- CAS

-

conventional activated sludge

- COVID-19

-

coronavirus disease 2019

- CoVs

-

coronaviruses

- DO

-

dissolved oxygen concentration

- EtV

-

enterovirus

- EV

-

ebola virus

- (F/M) ratio

-

food to microorganisms

- G

-

genotype

- Gc

-

gene copies

- HAdV

-

human adenovirus

- HAstV

-

human astrovirus

- HAV

-

hepatitis A virus

- HAV GIB

-

HAV subgenotype IB

- HBoV

-

human bocavirus

- HBoV-1

-

human bocavirus-1

- HBoV-2

-

human bocavirus-2

- HBoV-3

-

human bocavirus-3

- HCoSV

-

human cosavirus

- HE

-

haemagglutinin esterase dimer

- HEV

-

hepatitis E viruses

- HEV GI

-

hepatitis E genotype I

- HEV GIII

-

hepatitis E genotype III

- HEV GIV

-

hepatitis E genotype IV

- HIV

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- HF

-

hollow fibre membranes

- hPBV

-

human picobirnaviruses

- HPeV

-

human parechovirus

- HPyV

-

human polyomavirus

- HRT

-

hydraulic retention time

- H2O2

-

hydrogen peroxide

- IDTM

-

infectious disease transmission modelling

- JCPyV

-

polyomavirus JC

- LRV

-

log reduction value

- MBRs

-

membrane bioreactors

- MERS

-

middle East respiratory syndrome

- MF

-

microfiltration

- MLSS

-

mixed liquor suspended solids

- MWCO

-

molecular weight cut-off

- MW

-

molecular weight

- NPs

-

nanoparticles

- NF

-

dissolved matter by nanofiltration

- NoV

-

norovirus

- NoV GI

-

norovirus genogroup I

- NoV GII

-

norovirus genogroup II

- NoV GIV

-

norovirus genogroup IV

- OLR

-

organic loading rate

- Pt

-

platinum

- PMMoV

-

pepper mild mottle virus

- PES

-

polyethersulfone

- PVDF

-

polyvinylidene difluoride

- PV

-

poliovirus

- QMRA

-

quantitative microbial risk assessment

- OH˙

-

radical group

- Rep

-

replication initiator protein

- RNA

-

ribonucleic acid

- RO

-

reverse osmosis

- RT-PCR

-

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- RV

-

rotavirus

- RV G1

-

rotavirus genotypes I

- RV G2

-

rotavirus genotypes II

- RV G3

-

rotavirus genotypes III

- RV G8

-

rotavirus genotypes VIII

- RVA

-

rotavirus A

- RVC

-

rotavirus C

- SAFV

-

saffold virus

- SalV

-

salivirus

- SARS

-

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV

-

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SARS-CoV-2

-

novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

- SaV

-

sapovirus

- SRT

-

sludge retention time

- TiO2

-

titanium dioxide

- TMP

-

transmembrane pressure

- TTV

-

torque teno virus

- UF

-

ultrafiltration

- UV

-

ultraviolet

- VP

-

viral protein

- WBE

-

wastewater-based epidemiology

- WHO

-

world Health Organization

- WWTP

-

wastewater treatment plants

- ZIKAV

-

zika virus

- αCEHC

-

α-carboxyethyl hydrochroman

1 Introduction

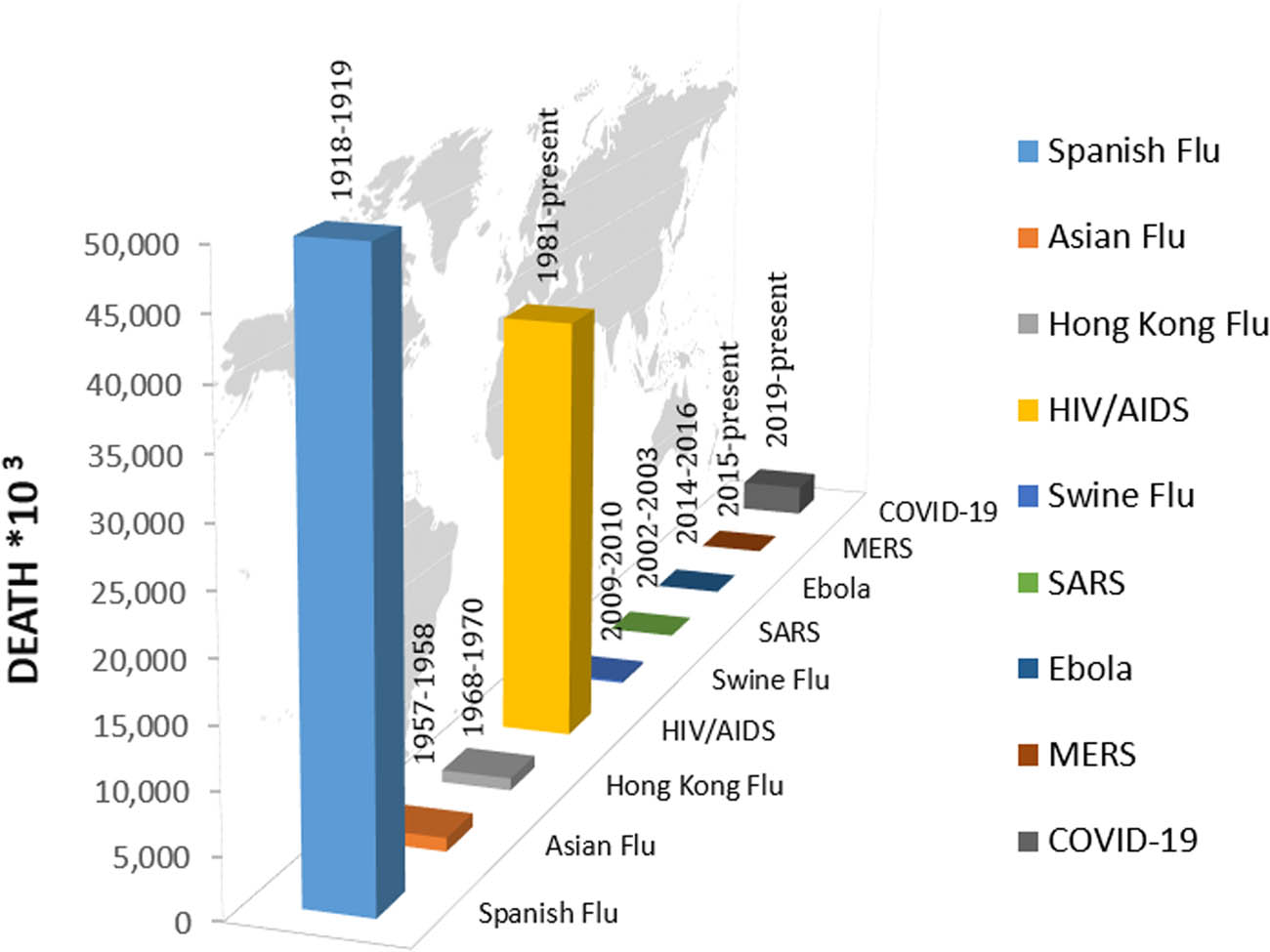

In Wuhan, China, 2019, a new species of Coronaviruses (CoV) was discovered and named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (comprises a genome size of 26e–32 kb in length). SARS-CoV-2 caused a zoonotic disease that became a pandemic after a few months [1]. CoVs are a well-known class of viruses that caused many diseases starting with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2003; then, MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) in 2015, and the last one is SARS-CoV-2 (novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2), which caused Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, reported in 2019. The novel SARS-CoV-2 has been confirmed to be 75–80% similar to SARS-CoV. That is why it was officially designated as SARS-CoV-2 after being temporarily designated as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (2019-nCoV) [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the spread of this infection has reached a tremendous level; 158,651,638 cases and 3,299,764 deaths were reported globally on 10 May 2021. Figure 1 shows the spread of coronavirus and other infectious diseases globally.

The death rate of coronavirus and other infectious diseases globally.

Removal of hazardous materials present in wastewater is now a complicated issue and a global challenge. Various materials can be detected in wastewater, including dissolved and nondissolved chemicals, dyes, heavy metals, phenols, and other miscellaneous substances [3]. In addition, many pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, cause millions of deaths every year due to diseases like cholera, hepatitis A virus HAV, typhoid fever, and diarrhoea [4,5]. SARS-CoV-2 spread was postulated to happen primarily through individual contact rather than via the faecal–oral route. However, a more profound understanding of SARS-CoV-2 in faeces and wastewater is necessary to control its spread. Many reports confirmed the presence of SARS and MERS in the wastewater, and SARS-CoV-2 is not an exception. Several studies have observed SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool samples from patients [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. This indicates that SARS-CoV-2 may be excreted through faeces and other body secretions (saliva and urine). Thus, it can easily reach the wastewater [18,19]. Recently, Sherchan et al. detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater in Louisiana, USA, using the ultrafiltration (UF) method [19]. Other studies reported the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the wastewater of many other countries, including Spain [20], Australia [21], Japan [2], Italy [22], and the Netherlands [23]. As a result, finding effective solutions for the disinfection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater is of immense importance for public health.

SARS-CoV-2 spread around the world has influenced people’s lifestyles [24] and caused the death of millions [25]. Therefore, it is imperative to know all possible ways of its transmission. One way to do that is through environmental monitoring, such as monitoring the presence of the virus in the wastewater. The majority of faecal–oral transmitted viruses are extremely resistant to water. Despite the common decontamination processes for drinking water and sewage treatment, they can persist at high levels [26]. For these reasons, it is crucial to keep an eye on wastewater to control many viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. In this review, SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in the sewage and available membrane technology for treating SARS-CoV-2-infected wastewater will be extensively explained.

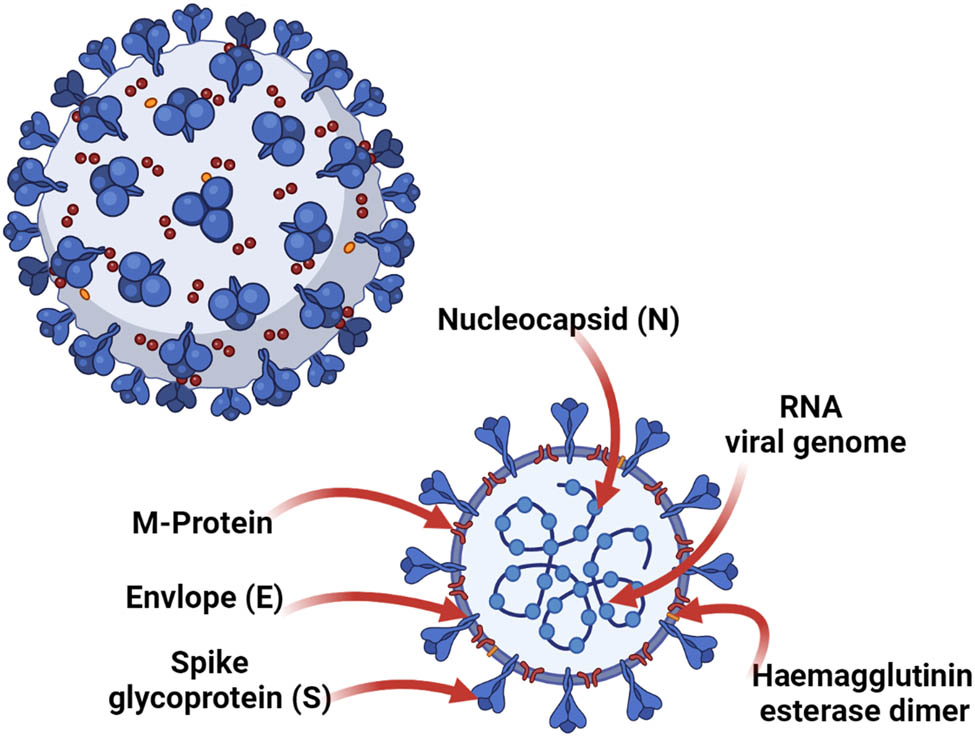

2 Structure and morphology of SARS-CoV-2

The virion size of SARS-CoV-2 ranges from 70 to 90 nm. RNA and N protein are responsible for the formation of the new virion. SARS-CoV-2 has three types of glycoproteins (spike, membrane, and envelope surface) embedded in the host membrane-derived lipid bilayer encapsulating the helical nucleocapsid comprising viral RNA. Spike glycoprotein is essential for binding and facilitating the entry of the virus into the host cell. Besides, M protein is determined to be a central organizer of the virus assembly, and it defines the shape of the envelope. It also interacts with E protein to form the viral envelope. Moreover, haemagglutinin esterase dimer (HE) protein facilitates S-assisted cell entry and spreads the virus throughout the mucosa [27]. Figure 2 shows the structure of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The structure of SARS-CoV-2 virus.

3 Wastewater-based epidemiology

3.1 SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in sewage: lessons learned from the strategy of controlled substances

Environmental scientists have continued to develop a plan of monitoring and developing epidemiological techniques to measure the combined, collective, or health status of entire populations over the last 20 years. This strategy is close to traditional mass urinalysis diagnosis but addresses sewage instead [28,29]. Besides, wastewater surveillance has been widely used to classify illegal substance hotspots [30]. The latest studies in wastewater virus surveillance have focused on the existence of human enteric viruses in wastewater and wastewater-infected environments. These studies showed a good correlation between local viral outbreaks and high levels of norovirus (NoV) [31], Hepatitis A and E viruses, HAV, and HEV, respectively [32,33], and enterovirus D68 [32,34] in sewage. Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) may be useful for identifying emerging and re-emerging pathogens in the community and may serve as an early warning system that would be useful for public health mitigation [29,35]. Table 1 explains the presence of various viruses in sewage water samples.

The presence of the virus in sewage water samples

| Virus | Location | Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Amsterdam, Den Haag, Utrecht, Apeldoorn, Amersfoort, Tilburg, and Schiphol, Netherlands | 3 weeks before the first case reported of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the Netherlands, samples taken on 6 February 2020 show negative results. During the first week of the epidemic, on 4 and 5 March, there were positive results for samples taken from Utrecht at 14–30 GC/mL. On 4 March, lower concentrations have been detected in Den Haag at 12–22 GC/mL. However, the result went negative on 5 March. Amersfoort and Schiphol show positive results on the 15 and 16 March, and the former was positive for N3 (6.6 GC/mL) while the latter was positive for N1 and N3 (2.6–12 GC/mL). On 25 March, all cities showed positive results for SARS-CoV-2 at 26–1800 GC/mL | [23] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Milano, Italy | Out of 18 samples collected from 3 WWTPs (4 raws and 2 treated), SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 6 raw samples. None of the treated samples shows positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The isolated virus genome belongs to the strain most spread in Europe. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was decreased after 8 days, indicating the natural decay of viral pathogenicity | [41] |

| SAFV | Karaj, Iran | Out of 28 samples, SAFV was detected in 10 samples. Concentrations of SAFV RNA ranged from 2 × 106 to 6.4 × 106 copies per L | [42] |

| ZIKV RNA | Atlanta, Georgia | Analysed sewage samples show positive ZIKV RNA. The isolated virus was stable at 4°C. Other conditions show 90% decay in RNA levels, at 25°C after 21 days and 35°C after 8.5 days | [43] |

| SalV | Karaj, Iran | SalV RNA was detected in both untreated and treated sewage samples. Concerning untreated samples, SalV RNA was detected in 3 out of 10 untreated sewage samples. Concerning the treated samples, SalV RNA was detected in 5 out of 12 treated sewage samples. The maximum viral load was evident in September, while the lowest was in December with values of 4.8 × 106 and 4 × 105 copies per L, respectively | [44] |

| HEV GIII | Campania region, Italy | Out of 29 samples collected from sewage discharge points, HEV was detected in 5 samples. All isolated strains were related to GIII, and a high degree of sequence identity was observed | [45] |

| adV | Kansai, Japan | Out of 12 sewage samples (1 sample/month), RVA, HBoV, and both NoV GI and GII were detected in all the samples. In 11 months, HAstV, SaV, and AiV were detected, while HAdV, EtV, SalV, and HPeV were detected in 8 months. The lowest detection rate was for SAFV, 2 months. Concerning RV genotypes, G1, G2, G3, and G8 were detected. One strain of G2 was similar to clinical strains detected in the epidemic season of 2014/2015, and 5 G2 strains separated from the reference strains detected in the epidemic season of 2015/2016 | [46] |

| AiV | |||

| AstV | |||

| EtV | |||

| HBoV | |||

| HPeV | |||

| NoV GI | |||

| NoV GII | |||

| RV G1 | |||

| RV G2 | |||

| RV G3 | |||

| RV G8 | |||

| RVA | |||

| RVC | |||

| SAFV | |||

| SalV | |||

| SaV | |||

| HBoV-1 | Greater Cairo, Egypt | Sewage samples were collected from three dissimilar WWTPs. In raw samples, HBoV median concentrations were 8.5 × 103 , 3.0 × 104 , and 2.5 × 104 GC/l for HBoV-1, HBoV-2, and HBoV-3, respectively. There was a reduction in the concentration in treated samples. However, the complete removal was not observed. It was reduced but not completely removed in the treated samples. Besides, in the outlet samples, HBoV median concentrations were 2.9 × 103 , 4.1 × 103 , and 2.1 × 103 GC/l for HBoV-1, HBoV-2, and HBoV-3, respectively. HBoVs show no seasonality patterns | [47] |

| HBoV-2 | |||

| HBoV-3 | |||

| HEV GIV | Shen Zhen, China. | Out of 152 samples from WWTP, only 2 were HEV GIV positive. According to blast analysis, the isolated virus was similar to that detected from a swine in Guangdong province, China | [48] |

| CLV-BR | São Paulo, Brazil | A total of 177 treated reclaimed water samples were grouped into 5 pools that were tested, and the CLV-BR gene was found in 2 of them with a percentage of 28% and 51%, p6, and p9, respectively, in addition to 76% of the Rep gene. The genomes detected were most likely related to CLV-BR hs1 | [49] |

| HEV | Coastal island, France | A total of 32 samples (were collected from four WWTP A, B, C, and D, 18 raw, and 14 treated. HEV was detected in four raw samples (3 WWTP B and 1 WWTP C). In December, HEV levels detected from WWTP B raw samples were 2-logs higher than that from WWTP C. In January, only the WWTP B raw samples were positive. All raw samples were below the limit of detection (2.2 log RNAc per L). HEV was negative in all treated samples | [33] |

| HEV GIII | Edinburgh, Scotland, UK | Out of 15 sewage samples, HEV sequences were detected in 14 samples. According to phylogenetic analysis, there was an observed pattern of HEV GIII with a local cohort of HEV‐infected hepatitis patients. Although the presence of HEV GI in English and Scottish hepatitis patients with an estimated percentage of 30% and 11%, respectively, HEV GI was not detected in the sewage samples | [50] |

| Mimivirus Bombay | Mumbai, India | The size of the isolated virus was around 1,182,200-bp and 435 nm genome. According to phylogeny-based DNA polymerase, the Mimivirus Bombay is the Mimiviridae family lineage A member | [51] |

| Mimiviridae family members with similar genome sizes were recorded previously to be detected in different environmental niches | |||

| HAV | West-central (Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine and Sbeitla) and East-central (Msaken, Ouerdanine and El Jem), Tunis | Out of 325 wastewater samples, 129 were HAV RNA positive. The samples were collected from 6 WWTP between December 2009 and December 2010. While comparing HAV in raw and treated samples of WWTPs, raw samples show a higher percentage of viral contamination, 56.8% and 22.7%, respectively. Cities in west-central Tunisia showed a higher average percentage of positive HAV samples in raw wastewater than east-central Tunisia, 62.96% and 50.62, respectively | [52] |

| EV | Pennsylvania, USA | The untreated wastewater was collected from WWTP. To determine the persistence of EV in the wastewater matrix, EV was spiked at two different concentrations for 8 days. No viable Ebola virus was recovered from samples spiked with 102 Ebola virus TCID50 mL–1 after the initial time zero sampling. Despite the rapid deduction of EV concentration by 99% on the first day, viable EV persisted for all 8 days of the test with a constant limit of detection of 0.75 log10 TCID50 mL−1 | [53] |

| RV | Naples, Bari, Palermo, and Sassari, Italy | Out of 285 sewage samples, RV was detected in 172 samples. In 26 samples, 198 RV G (VP7 gene) genotypes were detected. 32 samples contained multiple P (VP4 gene) genotypes, yielding 204P types in 172 samples. G1, G2, G9, G4, G6, G3, and G26 are accounted for RV types, 65.6%, 20.2%, 7.6%, 4.6%, 1.0%, 0.5%, and 0.5% respectively. Paediatrics patients in the same geographical area also had similar genotypes, particularly G2, G9, and p | [54] |

| AdV | Ryaverket and Gothenburg, Sweden | During the weeks when no positive patient samples were detected, it was still possible to detect NoV, SaV, RVA, AstV, AiV, and AdV in all sewage samples. Negative results have been recorded for parechovirus since it was not found in any sewage sample. The highest concentration of detectable viral genomes was for NoV followed by AstV, AdV, AiV, HEV, and HAV, respectively. For all weeks of sewage samples, low levels of HEV were detected (400–2,000). However, in the 9th week, the amount was unknown | [26] |

| AstV | |||

| HAV | |||

| NoV | |||

| RVA | |||

| SaV | |||

| Klassevirus | Seoul, South Korea | Of 14 sewage samples, klasse virus and PMMoV were detected in eight. They also were frequently detected in winter. NoV GII was detected in five samples, and NoV GIV in three samples. The latter was detected in December 2010 and January and March 2011. NoV GIV in Seoul belongs to the G-IV1 lineage according to phylogenetic analysis | [55] |

| PMMoV | |||

| NoV GII | |||

| NoV GIV | |||

| HEV | Córdoba city, Argentina | Out of 48 wastewater samples, HEV was detected in 3 samples. According to nucleotide sequencing, all isolates belonged to GIII, subtypes a, b, and c. IgG anti-HEV prevalence was 4.4% (based on 433 serum samples). Anti-HEV and socioeconomic levels did not show statistical relation despite the prevalence being higher in the low-income population | [56] |

| AiV | Netherlands | Fifteen samples were taken from each period from 1987 to 2000 and 2009 to 2012. Overall, AiV RNA was detected in 93% and 83% of water samples. Also, 16 sewage samples show positive AiV RNA. Out of 14 surface water samples, 12 samples and 9 samples show positive AiV RNA from each sampling period, respectively. AiV RNA was determined by targeting the 3C and VP1 regions | [57] |

| HAdV | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | The detection level of HAdV and JCPyV was higher than NoV and HAstV (p < 0.05, chi-squared test). The HAdV detection level was significantly higher than JCPyV (p = 0.02, Fisher exact test). The levels of NoV Gil and HAstV show no difference (p = 0.08, Fisher exact test). The average concentration of HAdV in raw samples was 2.97 × 106 GC L−1 compared with an average of 2.55 × l04 GC L−1 for the treated samples. The average concentration of JCPyV in raw samples was 5.98 × 105 GC L−1, while JCPyV DNA average was 3.31 × 103 GC L−1 | [58] |

| HAstV | |||

| JCPyV | |||

| NoV GII | |||

| NoV Gil | |||

| AiV | Teramo, Italy | Out of 48 sewage samples, AiV RNA was detected using the kobuvirus universal primer set and primer set Ai6261/Ai6779. However, the former was able to detect only 2 samples compared with 6 samples detected by the latter. The six AiV-like strains were distributed over the four WWTPs tested | [59] |

| HAV GIB | Cairo, Egypt | Out of 76 sewage samples, HAV-genotype IB was detected in 11 samples based on VP3–VP1 capsid protein partial sequencing. HAB – genotype IB positive samples were positive as well for EtV (p < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). There was no significant reduction in the viral load between the inlet and the outlet for both WWTPs. All sewage samples were negative for HEV virus by conventional and real-time RT-PCR | [60] |

| HEV | |||

| HAdV | North Rhine Westphalia region, Germany | A total of 24 (12 raw and 12 treated) sewage water samples were collected, and it was possible to detect HAdV, HPyV, and PMMoV in all samples. TTV and hPBV were detected in 6 raw samples and 3 treated samples. PMMoV is shown to be specific to human-derived faecal waste based on 20 samples collected from humans | [61] |

| hPBV | |||

| HPyV | |||

| PMMoV | |||

| TTV | |||

| HEV GI | Campania, Umbria, Piedmont, Giulia, Basilicata, Lombardy, Tuscany, Emilia Romagna, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia, Latium, and Sardinia, Italy | A total of 118 sewage samples were examined: 19 samples were HEV RNA positive in 9 regions out of 11 (18 HEV GI and 1 HEV GIII). No detectable PCR inhibitors in the negative samples. 0.7% was the average pairwise distance between GI sequences. Most of the positive samples were collected in winter or spring | [62] |

| HEV GIII | |||

| RVA | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Using the multiplex qPCR assay, it was possible to detect 30 RVA and 10 PP7 genomes per reaction. The cycle threshold values were 34.82 and 37.51 | [63] |

| AiV | Monastir, Tunisia | Of 250 sewage samples, it was possible to detect AiV only in 6% of the samples. Also, 15 strains of AiV were detected via phylogenetic analysis of a partial genomic region, 468 bp | [64] |

| HEV | Messina, Italy | Out of 46 sewage samples, HEV was detected in three samples, one was from raw sewage in September, and two were from untreated sewage of WWTP in May and June. It was not possible to detect HEV in any of the samples | [65] |

| NoV | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | A total of 144 samples were collected equally from 3 WWTPs. NoV was detected in 49 samples. The average removal ratio for the activated sludge process was 0.6 log 10 and 0.32 log 10 for NoV GI and NoV GII, respectively. The peak concentrations for NoV were detected in the coldest months, with 53,300 GC L−1. Phylogenetic analysis and nucleotide sequencing show that 5 strains clustered with GI strains and 6 with GII strains. Despite the sewage treatment, NoV could spread to the environment and remains a source of waterborne outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis | [66] |

| PV | Jinan, China | One sewage sample was collected from WWPS. After concentrating on the sample, it was possible to separate strain P3/Jinan/1/09 using the L20B cell line. The neutralization test shows the isolated strain related to PV type III. VP1 region Full-length amplification and sequencing exposed a Sabin type III/type II recombinant with a crossover site at the 3′-end of VP1 region | [67] |

While global clinical monitoring for COVID-19 has been developed, there is a range of instances of asymptomatic patients and those with very mild symptoms may not have been detected, and connections that were not theoretically missed estimated at 80% of real transmission. Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 tracking of wastewater is ideally suited to identify the spatial and temporal changes in the occurrence of diseases [36]. Sewage can be an important monitoring point for WBE because SARS-CoV-2 virions are excreted in the faeces of COVID-19 patients. Several researchers have already documented traces of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, especially in Australia, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the USA [37,38].

Experts from the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment studied wastewater samples from Amsterdam Schiphol Airport over many weeks and found that they could detect SARS-CoV-2 using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) within 4 days of confirmation of cases in the country [39]. Hence, the usage of WBE to warn SARS-CoV-2 responses could have a comparable potential value [40].

3.2 WBE as a tool for monitoring population food consumption and stress biomarkers

Urine has been researched in order to treat multiple medical disorders since ancient times [68]. Urinalysis is still used today to identify and track multiple pathophysiologies or behaviours. Diverse nutrients, proteins, hormones, molecules, and small substances in urine represent organisms’ well-being and interaction with the environment and can be obtained quicker and less invasively than serum samples [69,70]. Urine is being used as a diagnostic instrument in clinical environments, for example, to detect cancer early or to assess the degree of oxidative stress at the surface of the cell or tissue [71]. Metabolomics experiments have identified various biomarkers for the intake of specific foods, such as whole grains or citrus, which have been proposed as instruments for quantitative measurement of dietary regimen conformity in clinical and metabolic trials [72,73,74].

Law enforcement agencies have implemented urinalysis procedures for analysing metabolites in narcotics. The same idea is applicable at a population level in WBE, which is primarily concerned with assessing opioid usage in populations. Numerous urinary biomarkers of food and oxidative stress have been proposed in recent years to correctly monitor the food consumed and oxidative stress experienced by citizens in wastewater. Excluding the vulnerability to deterioration in sewage reactors, vitamin B2, vitamin B3, and fibre consumption biomarkers, as well as a portion to citrus, had loads per capita in line with the reported literature values. The usage of biomarkers of red meat, fish, fruit, some vitamins, and stress biomarkers per capita was incompatible with literature findings and/or rapidly degraded in sewer reactors, meaning they are not ideal for use as WBE biomarkers in the traditional quantitative sense [75].

Population stress urinary biomarkers such as 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-iso-PGF2α), well-being such as insulin-like growth factor 1, and dietary aspects such as isoflavonoids have been proposed in numerous studies as WBE biomarkers [40,76,77,78,79].

The oxidative stress biomarker 8-iso-PGF2α was tested in wastewater [80,81], and assessed its stability under sewage conditions [82]. The enterodiol and enterolactone fibre biomarkers, as well as the 4-pyridoxic acid vitamin biomarkers, 1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide (2PY), 1-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide (4PY), and α-carboxyethyl hydrochroman (αCEHC) were tested in Australian wastewater. Measurements of plant phytoestrogens enterolactone, daidzein, and genistein in American wastewater were reported in one book chapter [83]. British research outlined a method for calculating the 8-iso-PGF2α, 8-nitroguanine, and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) stress markers in wastewater [84].

Since the infection with SARS-CoV-2 is primarily known to be by droplets or contact with virus-containing aerosols [1], possible viral contamination in water, bio-aerosols, and food should be considered. In fact, SARS-CoV faecal presence has been verified [85,86]. Besides, the virus’s ribonucleic acid (RNA) was also detected in stools of individuals infected with MERS and SARS [1,17]. Similarly, the novel SARS-CoV-2 has shown a spread through the faecal-oral transmission with stools [17].

As SARS-CoV-2 is similar to SARS-CoV in the genetic material more than the MERS virus, it was suggested that the latter could be transmitted through toilets and bio-aerosols [87] as reported in 2003–2004 for SARS-CoV [88]. In addition, because of the longevity of humans and animals, plants infected with SARS-CoV-2 through infected water can lead to more transmission of the virus.

3.3 The early warning of localised SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks via wastewater analysis challenges

Although the wastewater survey may provide a snapshot of the overall concentration of drugs, the method is oblivious to the dynamic social systems responsible for opioid harm and the transmission of viruses such as hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Wastewater analysis may deliver early notice of localised outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2, but it cannot account for complex population dynamics or unique social and behavioural activities that trigger outbreaks. This awareness is essential for the implementation of successful actions. We know from the previous outbreak of Ebola that treatments will cause adverse results, also precipitating resistance to virus regulation by the population. Without research that considers the social and cultural nature of the dissemination of viruses and how populations react to treatments, successful solutions are not feasible. The examination of wastewater is a minimal instrument for advising intervention. It might inform us where is the SARS-CoV-2 is but not how best to interfere [89].

While SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance offers a valuable method for evaluating the prevalence at a population level of disease, it is evident that it still needs to be incorporated with other public health programs, clinical case recording, and mobile notifies tracking [90]. Therefore, it is necessary to examine how best to reconcile public safety with civil liberties ethically with lawfully when treating this information [91]. Nonetheless, one of the advantages of wastewater is that it has minimal sociological prejudice for little if any ethics concerns [92]. It is highly challenging, if not unlikely, to convert the viral titres of wastewater into the actual number of cases inside a population. This form of an estimate is focused on certain hypotheses that remain loosely quantified (e.g. the volume and nature of viral faeces shedding, viral longevity in the sewage system, and the difference in the distribution of wastewater linked to the environment, etc.). In comparison, although tailored to broad metropolitan areas (i.e. populations >10,000), the method is less economically and logistically adapted to diverse rural neighbourhoods that could have hundreds of limited water treatment establishments [92].

4 Membrane solution for coronavirus removal from wastewater

The viruses are present in raw wastewater, treated wastewater, sludge, and consequently, in the receiving water bodies and other environments. Thus, it is required to determine the pathways of virus transmission to limit the risk of the disease. This information can be determined accurately through the Infectious Disease Transmission Modelling (IDTM) and Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA) [63]. The pattern of infection in the human population indicates the presence and diversity of pathogenic viruses in wastewater, and the detection of viruses in different water matrices and different sampling points defines the suitable pre-treatment methods of wastewater [93].

Membranes have achieved an important place in chemical technology and are applied in a wide range of applications. The considered primary concept is the capability of a membrane to control the passage or the permeation rate of a chemical species through the membrane. Separation application is the common one of membrane applications. The goal is to select one component of a mixture to pass or permeate the membrane freely while preventing the permeation of other components. This mass transport is divided into three stages: through phase 1 (feed), across the membrane, and through phase 2 (permeate). The mechanism of permeation depends on the driving force, which can be generated as a result of the concentration gradient across the membrane (ΔC), the hydrostatic pressure difference across the membrane (Δp), the temperature difference across the membrane (ΔT), and the electrical potential difference across the membrane (ΔE).

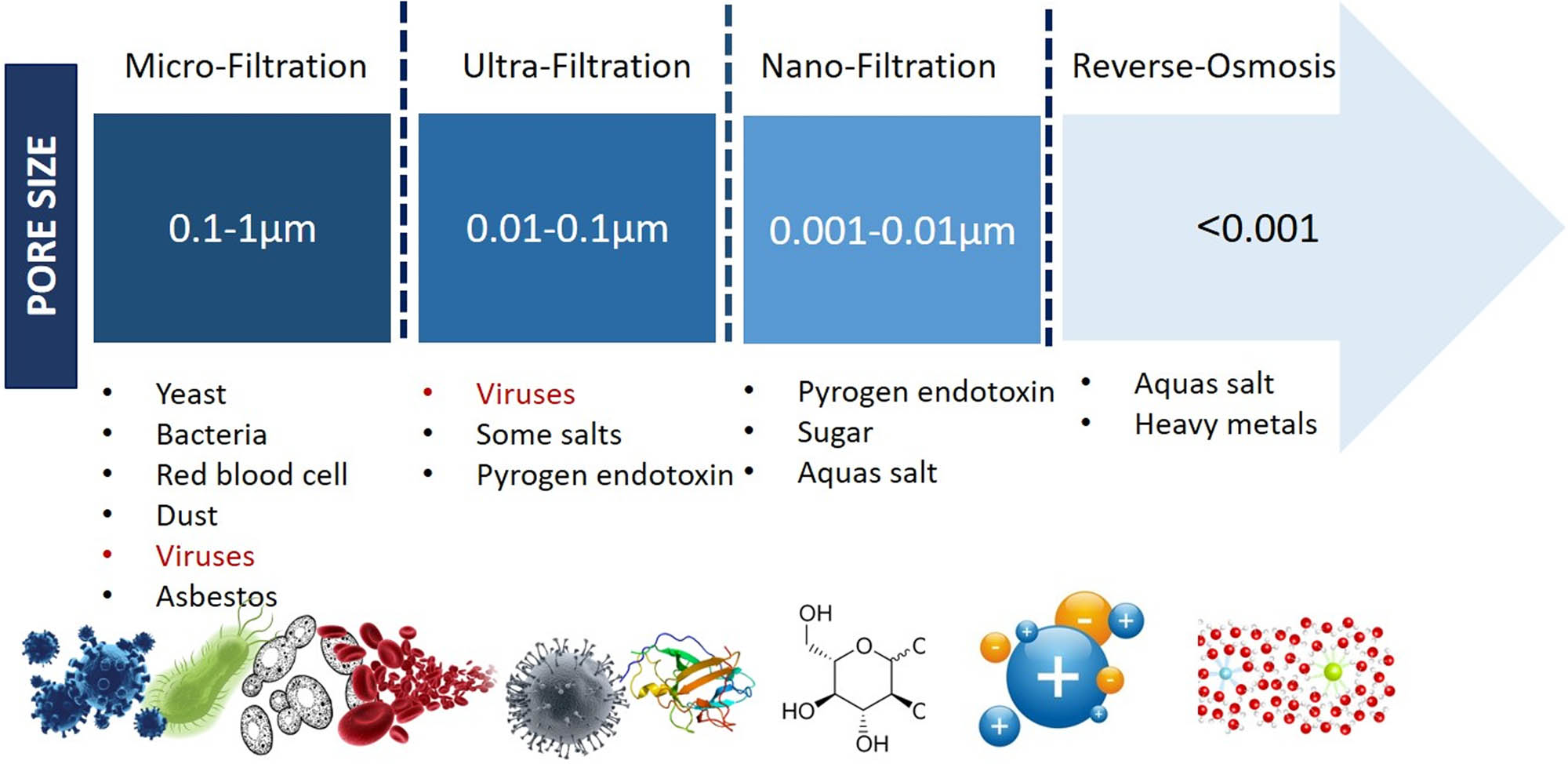

A membrane technique is commonly known as an operation for separation processes such as filtration, extraction, and distillation that cover a broad range of problems from particles to molecules. The applications of membrane technology are manifold. In fact, membranes are not only used for separation processes but can also be applied for gas storage in biogas plants or act as catalysts in syntheses [94]. They range from removing the particulate matter by microfiltration (MF) and UF, and dissolved matter by nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO) (Figure 3).

Classification of membrane processes according to pore size and criteria of removal.

The effect of membrane materials is essential because of the interaction between viruses and membrane materials. It can be challenging to select the right membrane type and material for a special process, and some given data about the process environment must be available to make a suitable selection. The first step is to determine the preferred process (NF, RO, UF, or MF). Based on the process environment, the best-suited membrane material can then be the second step. The chemical and thermal resistance of several membrane materials may be helpful in membrane performance.

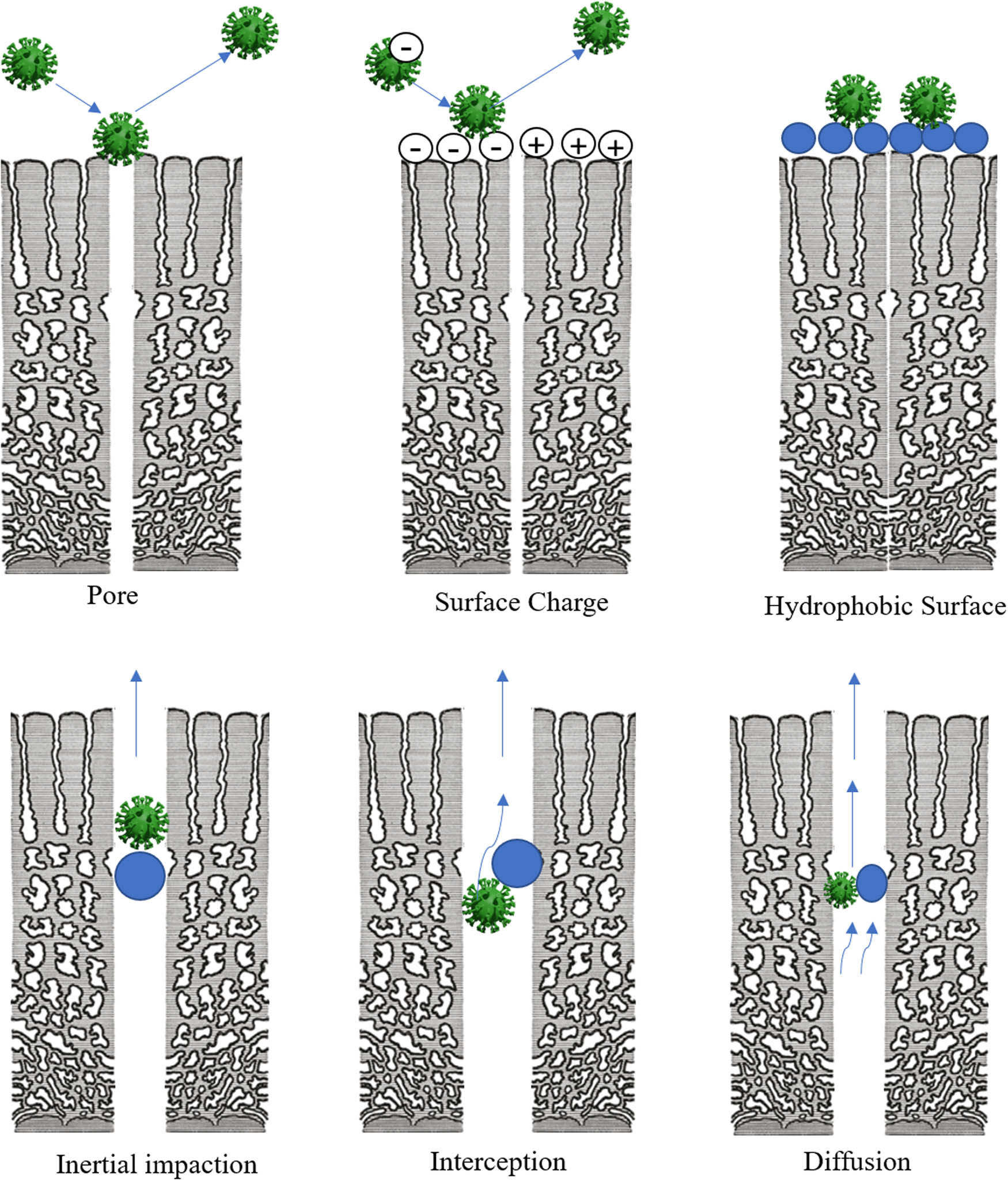

Adsorption, which is primarily driven by hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between viruses and membrane surfaces, can eliminate viruses. Furthermore, electrostatic repulsion aids virus elimination when viruses and membrane surfaces have the same charge (Figure 4).

A schematic diagram for membrane mechanisms for removing viruses from water.

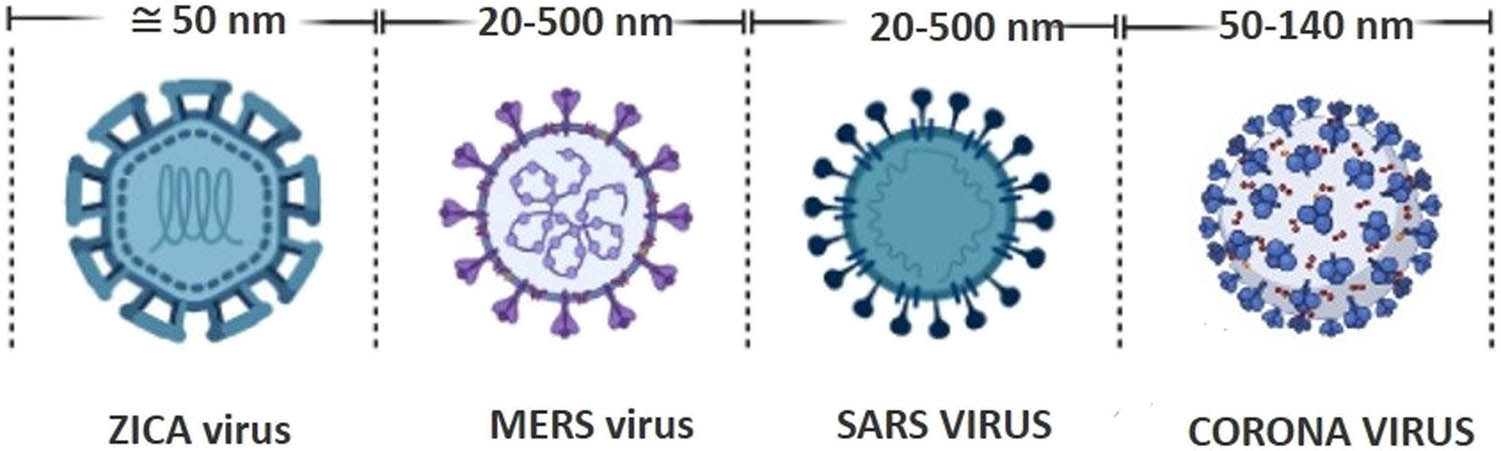

In this issue, various membrane applications are mentioned but we will focus on removing viruses from distinct types of wastewaters. We aim to illustrate and display the current and promising membrane technologies for monitoring, quantifying, and treating viruses in wastewater. Virus removal is one of the vitally important applications of membrane technologies, especially when water reuse becomes widespread. Currently, membranes are considered suitable methods in disinfection and ideal separation processes for various effluents. The chart below is a schematic representation of the types of particles that can be removed from the water using membrane filtration processes according to the pore size of the membrane. RO, NF, and UF membranes should be able to remove SARS-CoV-2 considering that its size is 100 µm [95] (Figure 5).

Coronaviruses related size.

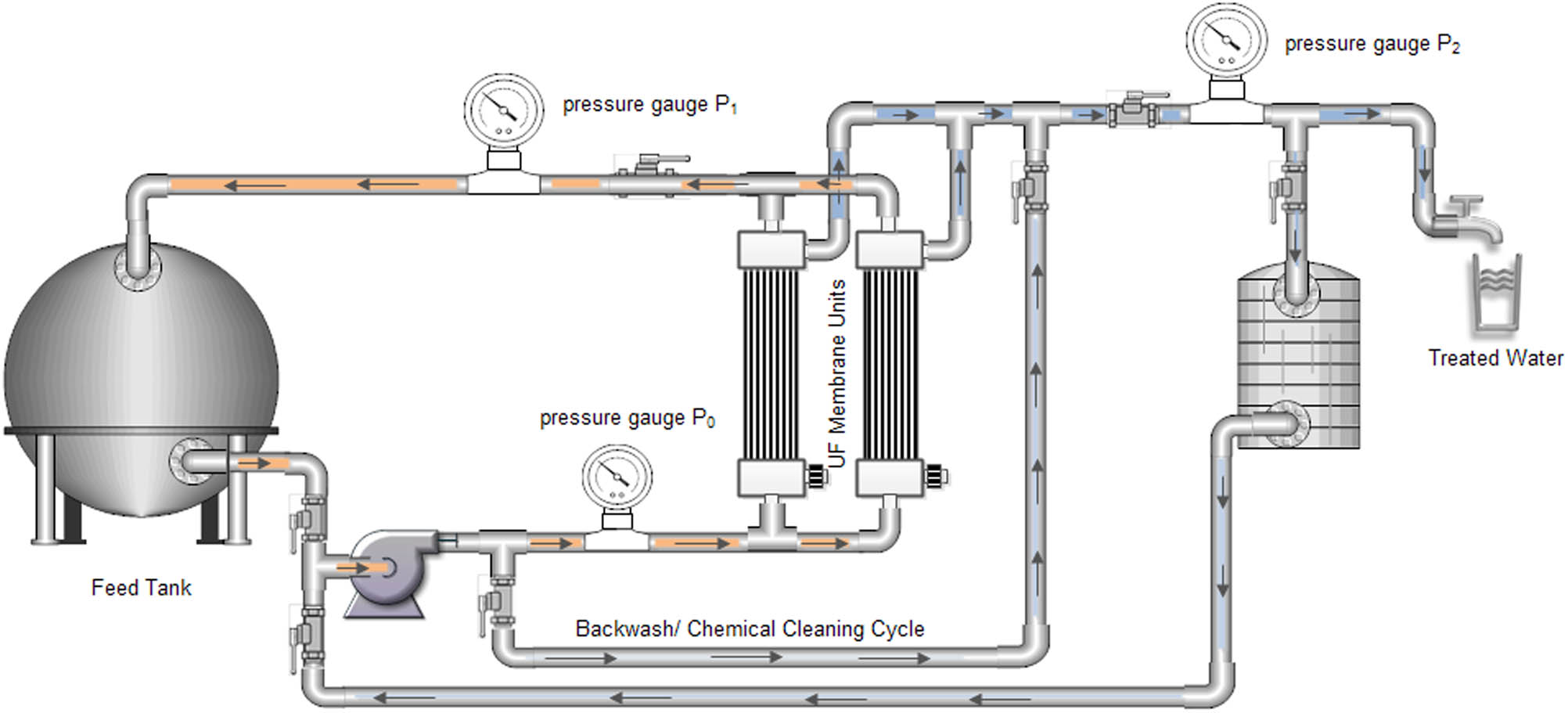

4.1 UF membrane system for virus removal from domestic water

The presence and diversity of pathogenic viruses in domestic wastewater reflect the trend of infection in people. Domestic wastewater is a common source of various pathogens, which maybe not be sufficiently treated. In this case, the viruses move to the receiving water bodies and cause many water-transmitted diseases. The UF membrane separation technique is considered one of the most suitable ways to remove viruses in the water-related microbial world. It is characterised by the larger pore size; consequently, lower pressure and lower cost are needed. The pore size of UF ranges from 10−3 to 10−1 µm, and the molecular weight (MW) varies from 103 to 105. This pore size range allows the salts, some of the organic substances, and small peptides to pass through. At the same time, fats, proteins, bacteria, and viruses are not permitted to pass, and they are rejected. UF is very useful for eliminating physical properties of domestic effluents such as odour and colour. Besides, UF guarantees the complete removal of turbidity. For viruses and bacteria, UF can remove more than 99% of them. No dead bacteria or ultra-pure water are produced. Transmembrane pressure (TMP) ranges from 5 to 35 psig. Fouling is the main problem of the UF membrane. Decreasing the filtration capacity acts like a decline in flux or a dramatic increase in TMP indicating fouling. The efficiency of fouling control depends on backwash and chemical cleaning processes from time to time. Figure 6 presents a process design for the UF system for a stream of domestic wastewater. Maintenance of membrane or cleaning does not require more than a few minutes. Viruses in domestic wastewater are affected by physical and chemical factors controlling the survival of enteric bacterial and viral pathogens in domestic wastewater, temperature, sunlight, and humidity. In COVID-19, it is evident that there are challenges to dominate techno-scientific applications in the large microbial world. Still, virus filtration of wastewater is an ideal key to keeping water safe from emerging viruses like CoVs.

The use of ultrafiltration membrane system for virus removal from domestic water.

4.2 Hybrid multimedia filter/UF membrane for treating industrial wastewater

One of the most difficult challenges facing the industrial wastewater treatment process is controlling microbial load and the detection method during the different stages of the remediation process. Disinfectants may be used but they are not effective when the virus is smaller than bacteria. At this point, the role of meta-genomics or series of analyses comes to monitor wastewater treatment units to predict outbreaks and connect with public health surveillance. Re-evaluation of the regulations related to the pathogenic viruses in wastewater is a vital issue. Pre-treatment of industrial wastewater to eliminate different types of bacteria and viruses is required. Therefore, using a multimedia filter as a pre-treatment process for wastewater is remarkably effective to minimise the microbial load on the UF membrane units. Generally, the utilisation of hybrid media-filter-UF membrane for industrial water treatment containing viruses is an ideal low-cost system alternative to RO technology. Figure 7 illustrates steps and the components of a hybrid multimedia filter-UF membrane system for treating industrial wastewater, including viruses.

Hybrid multi-media filter ultrafiltration membrane system for industrial wastewater treatment.

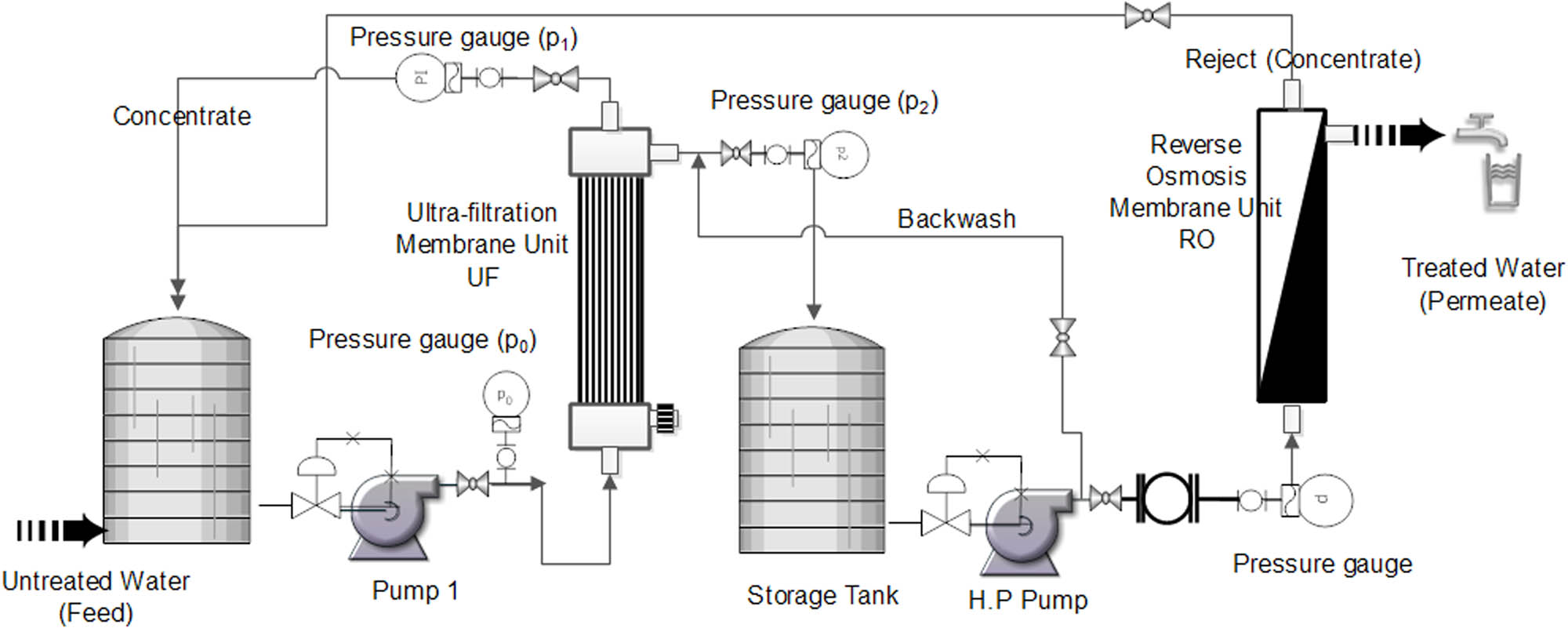

4.3 Hybrid UF/RO membrane system for treating domestic water

COVID-19 is characterised by unexpected nature, that is, it may infect healthy persons for a long time without any symptoms. Therefore, risk mitigation procedures against entering viruses into remediation process streams are becoming more important than ever [96]. RO membranes have a pore size <10−3 µm. They are very effective to remove all organic substances, bacteria, and viruses. Bacteria such as E. coli, Shigella, and Salmonella can be rejected; their size ranges from about 0.2 to 4 µm, which means that they are too large compared with the pore size of the RO membrane. RO membrane technology can remove protozoa (e.g., giardia and cryptosporidium) and viruses (e.g., rotavirus, enteric, HAV, and NoV). Also, they are cable of removing minerals that may be present in wastewater. They remove monovalent ions; therefore, they can be used to produce deionised water. As clean water resources are becoming increasingly scarce in many areas of the world, these membrane techniques are increasingly important. RO membrane technologies are facing challenges. One of the major serious issues is the cost of the treatment process due to the high operating pressure needed. Also, fouling is another challenge of RO because of the small pore size and applying high operating pressure. The three basic categories of RO membrane fouling are biofouling, organic, and inorganic substances. Typically occurring problems of membrane fouling and possible optimisations of the described membrane processes have been considered through the proposed hybrid UF/RO system for treating domestic water in Figure 8. In this design, we use an integrated system of UF/RO for treating water to improve the performance of the RO unit and decrease the fouling phenomena, and hence increasing the long life and efficient operation of RO. Briefly, the presence of the UF membrane unit as a pre-treatment process for the RO membrane process minimises the load of suspended solids and the microbial content. As this feature occurred, the performance of the RO membrane to eliminate any viruses from wastewater streams has completely occurred. Besides, the required energy is reduced and decreases the produced sludge or chemical disposal for chemical cleaning. Generally, the techno-environmental and economical solution achieves its objectives.

Hybrid ultrafiltration-reverse osmosis membrane system for virus removal from domestic water.

4.4 Virus removal from wastewater using membrane bioreactors (MBRs)

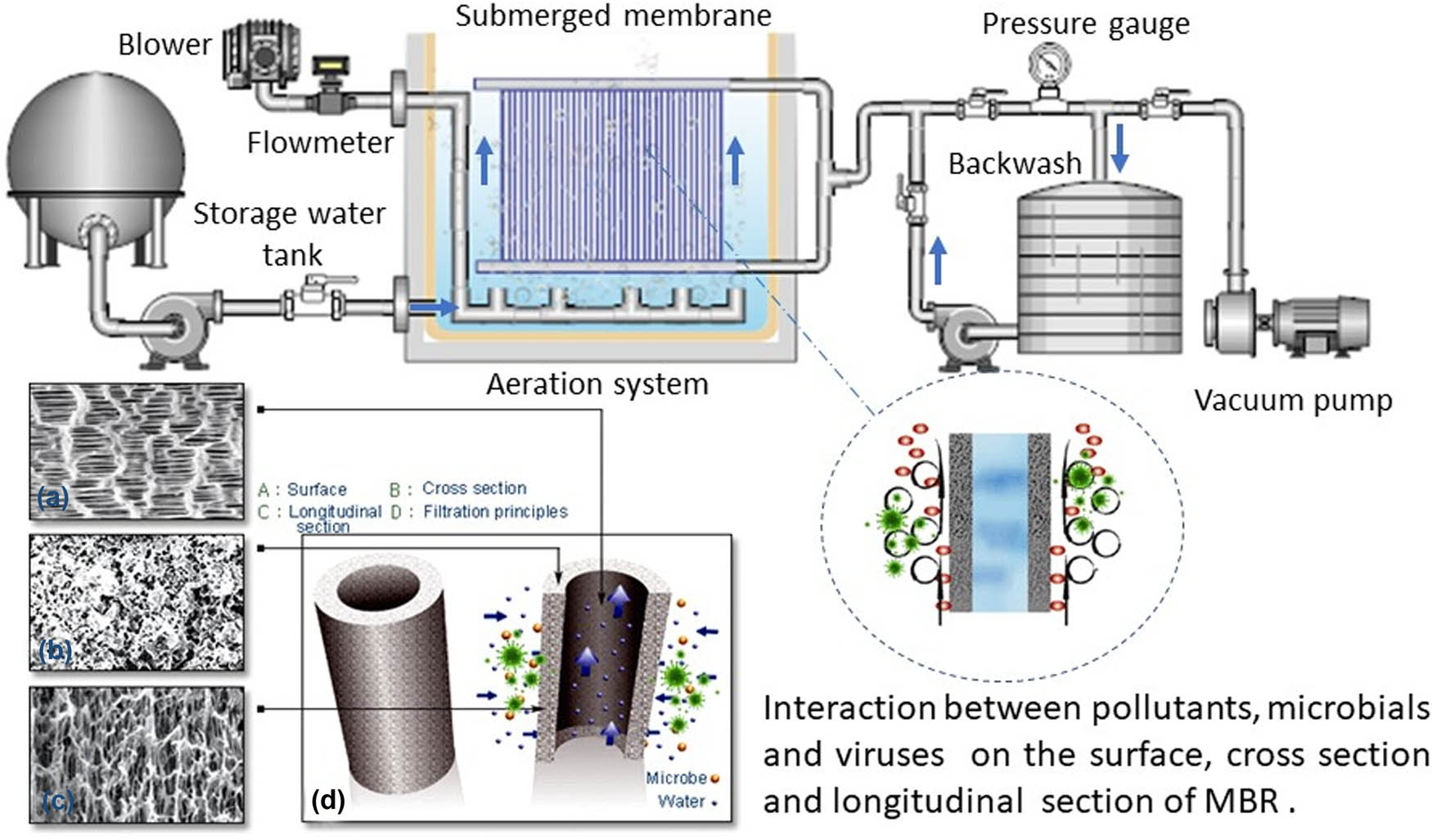

Bacteriophages were used to study the removal of viruses using the MBR treatment process as culturable samples of human-related viruses. MBR processes are defined as an integrated system of the UF or MF membrane and biological treatment unit [97]. It is an advanced version of the conventional activated sludge (CAS) [98]. The membrane may be immersed in the system or separated depending on design considerations. It is a commercial membrane; 50% of the membranes used in UF or MF membranes are hollow fibre membranes made from the modified polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF). Polyethersulfone (PES) membranes came in the secondmost-used material of membranes. The suitable membrane configuration is submerged (immersed) design with (outside in) influent. In MF, the most challenge is the fouling problem, which has been investigated in several studies. The majority of these studies are linked with the microbial community as a main reason for fouling [99,100]. In other studies, the microbial community structure is the reason for fouling problem, regardless of the bio-degradable wastewater that needs to be treated. In another study, factors affecting the biofouling mechanism were reviewed [101]. Biofouling increases as the mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS), food to microorganisms (F/M) ratio, and organic loading rate (OLR) are high, and the hydraulic retention time (HRT), sludge retention time (SRT) and dissolved oxygen concentration (DO) are low [102]. High temperature and salinity also decrease membrane permeability and increase the soluble microbial products. One study on viruses’ removal investigated using hollow fibre (HF) membranes, one hydrophilic and two hydrophobic membranes. Hydrophobic membranes fouled faster than the hydrophilic membrane because hydrophilic compounds are capable of forming a gel layer on their surface [103].

The mechanism of virus elimination from the wastewater treatment process begins with the adsorption of viruses on the surface of aggregated particles that are separated by sedimentation. The MBR treatment process is a very convenient method for the removal of different viruses when compared with membrane technology. Table 2 shows examples of membrane bioreactor systems for virus removal and their log reduction values (LRVs) (2015 to 2020). In membrane technology, different factors can influence membrane performance in elimination; the membrane’s pore size is the dominant factor for the virus removal process, especially when the diameter size of the virus particle is smaller than the pore size of the membrane. However, in MBRs, viruses’ adsorption on the surface of aggregated particles besides design and operating conditions such as pH, dissolved oxygen, hydraulic retention time (HRT), and dimensions of units used [104]. Figure 9 represents a schematic design for immersed hollow fibre membrane bioreactor used to treat wastewater, including virus removal. It also displays the accumulation of aggregated particles on the surface and inside of the hollow fibre membrane. Backwash and chemical cleaning are important to maintain the flux remains in optimum values and recover the effectiveness of the treatment process.

Examples of membrane bioreactor systems for virus removal and their LRVs: 2015–2020

| MBR type | Virus type | Log reduction value (LRV) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot-scale MBR | Adenovirus | 0.2–6.3 | [105] |

| Full-scale MBR | Rotavirus | >2.0 | [97] |

| Full-scale MBR | Sapovirus | >3.0 | [97] |

| Pilot-scale MBR | Norovirus GI | 1.82 | [106] |

| Pilot-scale MBR | Norovirus GII | 3.02 | [106] |

| Pilot-scale MBR | Adenovirus | 1.94 | [106] |

| Full-scale MBR | Norovirus GI/GII | 2.3 | [107] |

| Full-scale MBR | Adenovirus | 4.4 | [107] |

| Pilot-scale MBR | Enterovirus | 0.3–3.2 | [108] |

| Pilot-scale MBR | Norovirus GII | 0.2–3.4 | [108] |

Log reduction value (LRV) = −log (permeate virus concentration/feed virus concentration).

Membrane bioreactor (MBR) for virus removal.

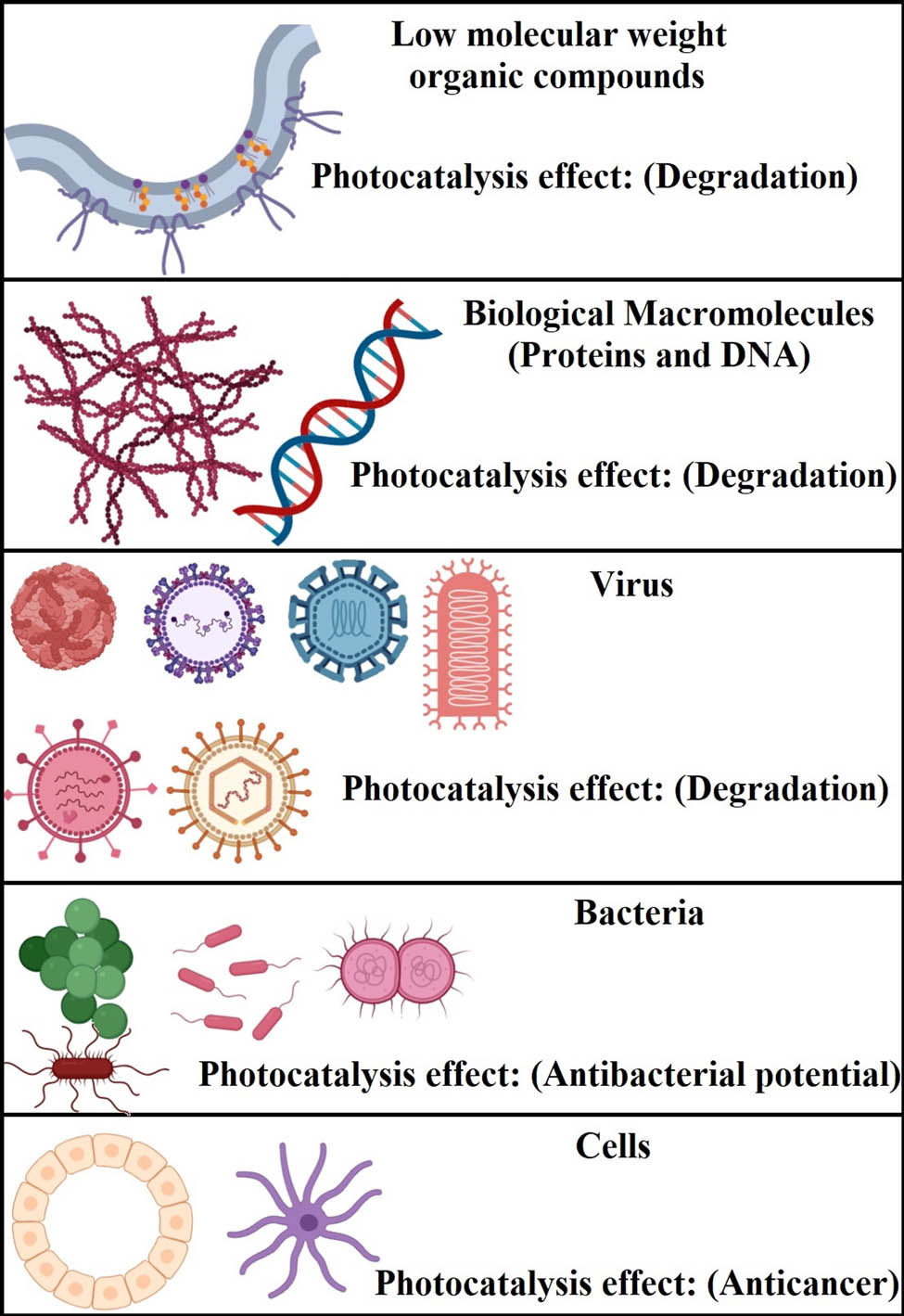

4.5 The MF-UV process with a photocatalytic membrane for virus removal

This is an overview of an integrated (hybrid) system of the MF membrane and photocatalytic process depending on the presence of ultraviolet (UV) used for virus inactivation and removal [109]. The photocatalytic process is an oxidation process and is classified as advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) that can destroy the particles in the range of 10−3 µm (1 nm). Because of this ability, photocatalysis has been used to remove and inactive viruses in wastewater. Since a few decades, specifically, in 1985, platinum (Pt)-loaded titanium dioxide (TiO2) was used as a catalyst for inactive viruses and eliminate three types of bacteria [110]; from this period, the application of photocatalysis to disinfect water has been growing [111]. AOPs are promising processes for remediation of wastewater, including difficulty in removing organic substances, especially, chlorinated-organic compounds. In addition, it has been proved that photocatalysis can trigger degradation in the case of simple compounds (e.g. protein and DNA), an inhibitory effect in case of viruses and bacteria [112–114], and an anti-cancer effect in the case of complex cells (e.g. pollen and spores). Using oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) alone is not effective for oxidation of elevated levels of contamination, but in the presence of UV or ozone, it can activate the hydrogen peroxide to form hydroxyl free radical group (OH˙) acting as a very strong oxidant. Using a hybrid MF membrane-UV photocatalytic process can be highly effective in eradicating viruses. TiO2 is a semiconductor material with the highest band, commonly named the valence band, and has another lowest band called the conductance band. Between these bands, there is a region called a bandgap. As the bandgap energy of semiconductors is decreased, it is easier to produce electron-hole pairs, h+e, which can react with the absorbed materials on the surface [115,116]. TiO2 semiconductor photocatalysis can be used as a powder dispersion form, phot-catalytic fixed bed reactor supplied with UV source and used as a thin film (Ag+–TiO2 thin film, Au–TiO2 thin film, Pt–TiO2 thin film, and Fe3+–TiO2 thin film). For the enhancement of TiO2 photocatalysis, we can use carbonaceous nanomaterials as additives. In addition, nanoparticles (NPs) can be used as an additive (Ag–TiO2, Ag–AgBr–TiO2, Ag–TiO2 nanotubes, and Au–TiO2) (Figure 10). Generally, these processes have highly either operating or capital costs [117].

Photocatalytic effects and living cells.

5 The use of nanotechnology in the detection and elimination of CoVs in wastewater

One of the most important applications of nanomaterials is the prediction and treatment of viruses in wastewater. Nanomaterials have unique properties, which characterise them as excellent materials to be applied in the manufacturing of sensors, spectrum devices, and techniques used in detecting, treating, and eliminating viruses from wastewater [118]. In this section, we present a brief about some of these applications (Figure 11).

Nanotechnology-based approaches for COVID-19 in water (detection/ treatment).

5.1 CoV detection in water using nanosensors

Early and rapid detection of coronaviruses in water helps to contain the infection more easily. Different engineered nanostructured materials have been known for their applications in sensors for the detection of various compounds. Nanosensors have been applied in several fields, involving doping analysis, laboratory medicine, food safety, and water examinations [119]. An example of these materials is silver NPs that can be used as flow-through Raman scattering sensors for water quality detection and monitoring. In addition, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are considered good materials for this purpose; specific properties of CNTs make them very attractive and preferred for the fabrication of nanoscale chemical sensors, especially for electrochemical applications [120].

Moitra et al. [121] developed a plasmonic gold NP-based biosensor for the detection of COVID-19 within 10 min. The developed test is very simple and depends on the color change (from purple to blue) of gold NPs upon combining with the virus’s gene sequence [121]. Besides nanosensors, membranes can be applied for the sensing process. As a result, the study emphasises the importance of optimised covering membranes as a functional aspect in sensors, one that necessitates coordinated efforts from membrane scientists.

5.2 Removal of CoV from wastewater using nano-adsorbents

Various techniques have been usually applied to eliminate organic and bio-pollutants in water, such as convention processes (adsorption, distillation, and filtration), biological processes (activated sludge, membrane bioreactors), chemical processes (chlorination and ozonation), and photocatalytic process [122]. Generally, the capability to adsorb organic pollutants is extremely related to the high surface area of the adsorbent. Therefore, the absorption capacity can be enhanced by developing nanometre adsorbents, characterised by high specific surface area, small particle size, and low internal diffusion resistance. It has been verified that magnetic NPs had superior adsorption efficiency over bacteria or viruses. Magnetic NPs are usually modified with bioprotein, antibody, and carbohydrate materials, which target bacteria, viruses, and microorganisms (Figure 12) [123].

Nano-adsorbents for virus removal from water.

Park et al. [124] have created an innovative magnetic hybrid colloid decorated with various sizes of Ag nanoparticles. It was made as a cluster of superparamagnetic Fe3O4 covered with a silica shell. They found that the magnetic hybrid colloid decorated with the Ag nanoparticle of 30 nm size (Ag30@MHC) demonstrated the best antiviral efficacy for bacteriophage MS2 (2–3 log reduction). Another study reported the synthesis of amine-functionalised magnetite Fe3O4–SiO2–NH2 NPs to remove viruses from water. These new types of magnetic NPs are characterised by firm structures and good magnetic properties due to the presence of the amine group. It is a crucial element in attracting several types of pathogens like bacteriophage f2 and poliovirus-1 with capture efficiencies of 76.73% and 81.53%, respectively [125]. Recently, Ramos-Mandujano et al. [126] have developed magnetic-nanoparticle-aided viral RNA isolation from the contagious sample (MAVRICS) open-source method that was able to extract SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater with 88% recovery of the tested viral RNA.

5.3 Degradation of CoV in wastewater by photocatalysis

TiO2 in the presence of UV light has a strong oxidation effect. Therefore, it can be used as a disinfectant based on the photocatalytic process. Photocatalytically TiO2 is usually applied as a self-cleaning and disinfecting material for many purposes [127]. CoV affected the view of wastewater plans; a team of nanotechnology from Rice University was investigating the ability to reconstruct their wastewater treatment technologies to deactivate SARS-CoV-2. Their studies found that photocatalysis could be used to inactivate CoVs by the usual photocatalytical materials. In the future, the team will modify their research to target SARS-CoV-2 and other CoVs by imprinting molecules, including virus attachment onto the graphitic carbon nitride photocatalysts [128].

Low pathogenic CoV will be used to determine the kinetics of the adsorption process and study the selectivity of the molecularly imprinted graphitic carbon nitride. To define the inactivation efficiency of the photocatalysis process, the residual viable virus concentrations will be quantified (Figure 13).

Degradation of CoV in wastewater by photocatalysis.

5.4 Nanotechnology for membrane performance enhancement in virus removal

Nanotechnology has a vital role to improve membrane performance in virus removal. Membranes have been modified by combining virucidal nanomaterials with the membrane during the manufacturing step, virucidal functionality was added to the membrane [129]. Virucidal nanoparticles have been incorporated into membrane matrices, commonly referred to as mixed-matrix (MM) membranes, to create antiviral membrane filters [130].

Antiviral MM membranes for water treatment have been made using a variety of biocidal nanomaterials (for example, silver nanoparticles and copper nanoparticles). Antiviral MM membranes have been the subject of research articles published in the recent few years. Despite the surge in interest in antiviral materials research, there are only a few review publications covering antiviral MM membranes among these studies [131].

Antiviral nanomaterials which can be used and applied are summarised in Table 3.

Membrane antiviral nanomaterial additives

| Antiviral nanomaterials | Virus | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Silver nanomaterials (Ag NMs) | • Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1), | [132] |

| • MS2 bacteriophage, | ||

| • Tacaribe virus (TCRV), | ||

| • Hepatitis B virus (HBV), | ||

| • Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) | ||

| Gold nanomaterials (Au NMs) | • Measles virus (MeV), | [133,134] |

| • Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) | ||

| Copper nanomaterials (Cu NMs) | • Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), | [135] |

| • Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | ||

| Zinc oxide nanomaterials (ZnO NMs) | • Human influenza A virus (H1N1), | [136] |

| • HSV-1 | ||

| Titanium oxide nanomaterials (TiO2 NMs) | • Newcastle disease virus (NDV) | [137] |

| Silica nanomaterials (SiO2 NMs) | • RSV, | [138] |

| • HIV | ||

| Tin oxide nanomaterials (SnO2 NMs) | • HSV-1 | [139] |

| Carbon nanomaterials | • Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), | [140] |

| • HSV-1,2, coxsackievirus (Cox B3), | ||

| • cytomegalovirus, grass carp reovirus |

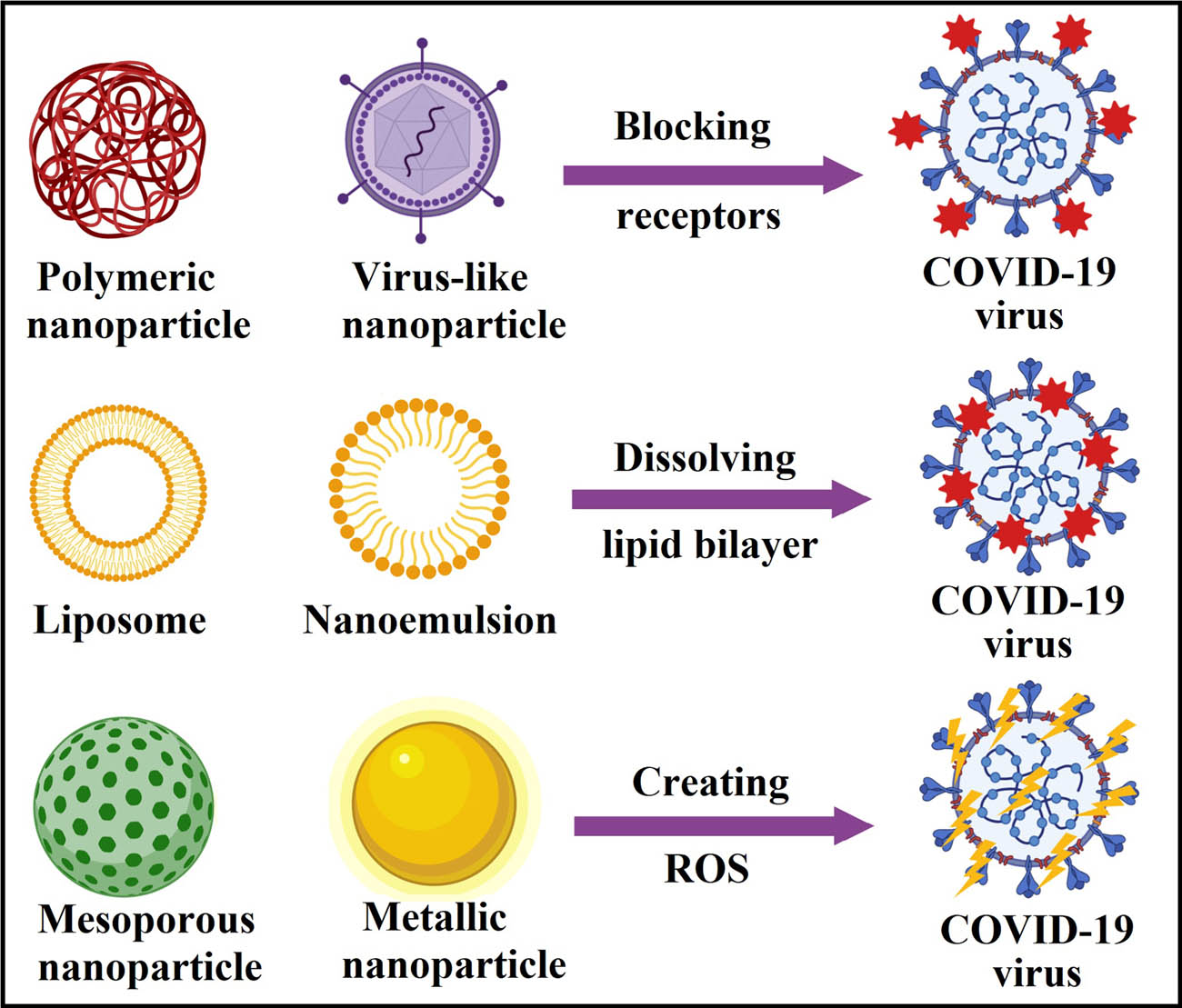

5.5 Reaction mechanism of different nanomaterials against CoV

There are different reaction mechanisms involved in CoV inhibition and removal from the environment. Between them, virus-like NPs and polymeric NPs can prevent CoV from spreading by blocking the vital viral receptors and as a result its entry to the host cell (Figure 14) [141,142]. The other mechanisms involved with the activity of liposomes and nano-emulsions have the capacity to interfere with the virion envelope composition or mask the CoV building, which finally prevents CoV adsorption and invasion into the host cells [143], and dissolves the viral lipid bilayer (Figure 14) [144,145]. Finally, some nanomaterials such as mesoporous and metallic NPs (like Ag NPs, and Au NPs) can initiate extracellular reactive-oxygen species (ROS) [146–148], which effectively kill and destroy the biological structure of CoV [144], as shown in Figure 14.

Nanomaterials as powerful disinfectants for CoV removal (different reaction mechanisms).

6 Conclusion and future aspects

SARS-CoV-2 is a virus that first appeared in China at the end of 2019 and quickly spread to the rest of the world, causing a COVID-19 pandemic. It was first believed to affect only the respiratory system but it was quickly discovered to affect the gastrointestinal system. The environmental impact is that SARS-CoV-2 is shed into the sewage system and thereby enters Wastewater Treatment Plants or, more broadly, the aquatic environment where it is present. The use of membrane systems in virus removal in wastewater has been considered to be necessary. Viruses should be retained entirely by UF or NF membranes based on the MWCO (molecular weight cut-off). Although the UF/MF membranes used with MBR treatment systems cannot be expected to be an effective media for virus-sized particles based on the membrane nominal pore size, under the optimal operating conditions, MBR systems are also capable of removing various viruses and phages. Using MBR treatment for viruses’ removal is not a novel subject; however, selecting the right membrane type in a long-term operation is important for maintenance, operation costs, and investment. Tertiary treatment of this type of wastewater for reuse will be recommended with different NF and RO membranes. It is essential to highlight that MBR water treatment systems need cleaning and chemical backwashing of the membrane periodically to prevent blockages of the pores and excessive biofilm formation. Disinfection by chlorination, ozone, or UV could sufficiently inactivate viruses to control them from passing to the environment with the streams, and we can say that ozone and UV seem to be more effective than chlorine. Wastewater treatment plants may be a solution for early disease identification in each area if a Wastewater Based Epidemiology strategy is developed. It may also be used as a lockdown decision helper. Due to the risk of SARS-CoV-2 spreading through the aquatic environment from inadequately treated wastewater, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic could raise global concerns that allow for upgrading wastewater management, even in developed countries, must be considered. On a global scale, increased efforts to strengthen wastewater treatment, especially eliminating or inactivating viral contaminants, should be a primary concern. COVID-19 virus in wastewater sludge must be taken into consideration for future studies. COVID-19 virus may be present in primary, secondary, and tertiary treatments and in chemically treated sludge. In fact, there are no current publications on the occurrence of SAR-CoV-2 in the residual sludge. A few studies have looked at the survival of coronavirus in wastewater in laboratory-scale studies either using pasteurised wastewater or viral surrogates. Membrane-based sensors are a new promising area with different applications and can be future prospective in the removal and sensing of viruses in water. Recently, many investigations employed different types of nanomaterials as either antimicrobial agents or effective drug delivery systems to increase the efficacy of the newly developed drugs for COVID-19. Therefore, more studies on the role of drug-loaded nanomaterial-based delivery systems should be considered. In addition, reaction mechanisms by which nanomaterials can act as promising nanovaccines or nanodrugs for patients with COVID-19 should be understood.

Acknowledgements

Author Mohamed Abouzid is a participant of STER Internationalisation of Doctoral Schools Programme from NAWA Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange No. PPI STE/2020/1/00014/DEC/02. Author Gharieb S. El-Sayyad would like to thank the Nanotechnology Research Unit (P.I. Prof. Dr. Ahmed I. El-Batal), Drug Microbiology Lab., Drug Radiation Research Department, NCRRT, Egypt. The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project (RSP-2021/332), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Eloffy M.G., writing-original draft, designing figures, drawing and revision; El-Sherif D.M., conceptualising, refining research idea, creating research design, writing-original draft and editing; Abouzid M., Abd Elkodous M.A., writing-original draft, editing, and revision; El-Nakhas H.S., Sadek R.F., writing-original draft, and editing; Ghorab M.A., Al-Anazi A., writing-review, and editing; El-Sayyad G.S., writing-review, designing figures, editing, and revision. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Venugopal A, Ganesan H, Sudalaimuthu Raja SS, Govindasamy V, Arunachalam M, Narayanasamy A, et al. Novel wastewater surveillance strategy for early detection of coronavirus disease 2019 hotspots. Curr Opinion Environ Sci Health. 2020;17:8–13.10.1016/j.coesh.2020.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Kitajima M, Ahmed W, Bibby K, Carducci A, Gerba CP, Hamilton KA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: State of the knowledge and research needs. Sci Total Environ. 2020;739:139076–76.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139076Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Ince M, Kaplan Ince O. Heavy metal removal techniques using response surface methodology: water/wastewater treatment. Biochem Toxicol - Heavy Met Nanomater. 2020. 10.5772/intechopen.88915.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Sarma J. Filtration and chemical treatment of waterborne pathogens. Waterborne Pathogens. Butterworth–Heinemann: British Publishing Company; 2020. p. 105–2210.1016/B978-0-12-818783-8.00006-2Suche in Google Scholar

[5] El-Sayyad GS, Abd Elkodous M, El-Khawaga AM, Elsayed MA, El-Batal AI, Gobara M. Merits of photocatalytic and antimicrobial applications of gamma-irradiated CoxNi1−xFe2O4/SiO2/TiO2; x = 0.9 nanocomposite for pyridine removal and pathogenic bacteria/fungi disinfection: implication for wastewater treatment. RSC Adv. 2020;10(9):5241–59.10.1039/C9RA10505KSuche in Google Scholar

[6] Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–36.10.1056/NEJMoa2001191Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Burke RM, Killerby ME, Newton S, Ashworth CE, Berns AL, Brennan S, et al. Symptom profiles of a convenience sample of patients with covid-19—united states, january–april 2020. Morbidity Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(28):904.10.15585/mmwr.mm6928a2Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207.10.1056/NEJMoa2001316Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Guan W-J, Liang W-H, Zhao Y, Liang H-R, Chen Z-S, Li Y-M, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respiratory J. 2020;55(5):2000547. 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Li X, Song Y, Wong G, Cui J. Bat origin of a new human coronavirus: there and back again. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):461–2.10.1007/s11427-020-1645-7Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–43.10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20.10.1056/NEJMoa2002032Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–7.10.1056/NEJMc2004973Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, Kimball A, James A, Jacobs JR, et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2081–90.10.1056/NEJMoa2008457Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Woelfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Mueller MA, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of hospitalized cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in a travel-associated transmission cluster. MedRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.03.05.20030502 Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Yeo C, Kaushal S, Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 possible? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:335–7.10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30048-0Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Maal-Bared R, Bastian R, Bibby K, Brisolara K, Gary L, Gerba C, et al. The water professional’s guide to COVID-19, Water. Env Technol. 2020;32(4):26–35.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Sherchan SP, Shahin S, Ward LM, Tandukar S, Aw TG, Schmitz B, et al. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater in North America: A study in Louisiana, USA. Sci Total Environ. 2020;743:140621.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140621Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Randazzo W, Truchado P, Cuevas-Ferrando E, Simón P, Allende A, Sánchez G. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area. Water Res. 2020;181:115942.10.1016/j.watres.2020.115942Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Uddin M, Hasan M, Rashid A, Ahsan M, Imran M, Ahmed. SSU. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19): Molecular Evolutionary Analysis, Global Burden and Possible Threat to Bangladesh. Nat Res. (preprint) Accessed 27 (2020) 2020. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-18985/v1.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Alzamora MC, Paredes T, Caceres D, Webb CM, Valdez LM, La Rosa M. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(8):861.10.1055/s-0040-1710050Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Medema G, Heijnen L, Elsinga G, Italiaander R, Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in The Netherlands. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7:511–6.10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Abouzid M, El-Sherif DM, Eltewacy NK, Dahman NBH, Okasha SA, Ghozy S, et al. Influence of COVID-19 on lifestyle behaviors in the Middle East and North Africa Region: a survey of 5896 individuals. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):129. 10.1186/s12967-021-02767-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Lee JH. COVID-19 as the leading cause of death in the United States. Jama. 2020;325(2):123–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.24865.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Hellmér M, Paxéus N, Magnius L, Enache L, Arnholm B, Johansson A, et al. Detection of pathogenic viruses in sewage provided early warnings of hepatitis A virus and norovirus outbreaks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(21):6771–81.10.1128/AEM.01981-14Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Mousavizadeh L, Ghasemi S. Genotype and phenotype of COVID-19: their roles in pathogenesis. J Microbiol, Immunol Infect. 2020;54(2):159–63. 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Daughton C. The international imperative to rapidly and inexpensively monitor community-wide Covid-19 infection status and trends. Sci Total Environ. 2020;726:138149. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138149.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Sims N, Kasprzyk-Hordern B. Future perspectives of wastewater-based epidemiology: monitoring infectious disease spread and resistance to the community level. Environ Int. 2020;139:105689–89.10.1016/j.envint.2020.105689Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Li X, Du P, Zhang W, Zhang L. Wastewater: a new resource for the war against illicit drugs. Curr Opinion Environ Sci Health. 2019;9:73–6.10.1016/j.coesh.2019.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Farkas K, Cooper DM, McDonald JE, Malham SK, de Rougemont A, Jones DL. Seasonal and spatial dynamics of enteric viruses in wastewater and in riverine and estuarine receiving waters. Sci Total Environ. 2018;634:1174–83.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.038Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Bisseux M, Colombet J, Mirand A, Roque-Afonso AM, Abravanel F, Izopet J, et al. Monitoring human enteric viruses in wastewater and relevance to infections encountered in the clinical setting: A one-year experiment in central France, 2014 to 2015. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23(7):17-00237. 10.28071560-7917.ES.2018.23.7.17-00237.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Miura T, Lhomme S, Le Saux JC, Le Mehaute P, Guillois Y, Couturier E, et al. Guyader, detection of hepatitis E virus in sewage after an outbreak on a French Island, food and environmental. Virology. 2016;8(3):194–9.10.1007/s12560-016-9241-9Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Majumdar M, Wilton T, Hajarha Y, Klapsa D, Martin J. Detection of Enterovirus D68 in wastewater samples from the United Kingdom during outbreaks reported globally between 2015 and 2018. bioRxiv. 2019;738948. 10.1101/738948 Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Xagoraraki I, O’Brien E. Wastewater-based epidemiology for early detection of viral outbreaks. Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Nature Publishing Group; 2020. p. 75–9710.1007/978-3-030-17819-2_5Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Larsen D, Dinero R, Asiago-Reddy E, Green H, Lane S, Shaw A, et al. A review of infectious disease surveillance to inform public health action against the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. SocArXiv. 2020. 10.31235/osf.io/uwdr6.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Ahmed W, Angel N, Edson J, Bibby K, Bivins A, O’Brien JW, et al. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci Total Environ. 2020;728:138764–64.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Mallapaty S. How sewage could reveal true scale of coronavirus outbreak. Nature. 2020;580:176–7.10.1038/d41586-020-00973-xSuche in Google Scholar

[39] Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63.10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Choi PM, Tscharke BJ, Donner E, O’Brien JW, Grant SC, Kaserzon SL, et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology biomarkers: Past, present and future. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2018;105:453–69.10.1016/j.trac.2018.06.004Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Rimoldi SG, Stefani F, Gigantiello A, Polesello S, Comandatore F, Mileto D, et al. Presence and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewaters and rivers. Sci Total Environ. 2020;744:140911–11.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140911Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Aminipour M, Ghaderi M, Harzandi N. First occurrence of saffold virus in sewage and river water samples in karaj, Iran. Food Environ Virol. 2020;12(1):75–80.10.1007/s12560-019-09415-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Muirhead A, Zhu K, Brown J, Basu M, Brinton MA, Costa F, et al. Zika virus RNA persistence in sewage. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7:659–64.10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00535Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Adineh M, Ghaderi M, Mousavi-Nasab SD. Occurrence of salivirus in sewage and river water samples in karaj, Iran. Food Environ Virol. 2019;11(2):193–7.10.1007/s12560-019-09377-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] La Rosa G, Proroga YTR, De Medici D, Capuano F, Iaconelli M, Della Libera S, et al. First detection of hepatitis E Virus in shellfish and in seawater from production areas in southern italy, food and environmental. Virology. 2018;10(1):127–31.10.1007/s12560-017-9319-zSuche in Google Scholar

[46] Thongprachum A, Fujimoto T, Takanashi S, Saito H, Okitsu S, Shimizu H, et al. Detection of nineteen enteric viruses in raw sewage in Japan. Infection, Genet Evolution. 2018;63:17–23.10.1016/j.meegid.2018.05.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Hamza H, Leifels M, Wilhelm M, Hamza IA. Relative abundance of human bocaviruses in urban sewage in greater cairo, Egypt. Food Environ Virol. 2017;9(3):304–13.10.1007/s12560-017-9287-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Li H, Li W, She R, Yu L, Wu Q, Yang J, et al. Hepatitis E virus genotype 4 sequences detected in sewage from treatment plants of China. Food Environ Virol. 2017;9(2):230–3.10.1007/s12560-016-9276-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Castrignano SB, Nagasse-Sugahara TK, Garrafa P, Monezi TA, Barrella KM, Mehnert DU. Identification of circo-like virus-Brazil genomic sequences in raw sewage from the metropolitan area of São Paulo: Evidence of circulation two and three years after the first detection. Mem do Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112(3):175–81.10.1590/0074-02760160312Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Smith DB, Paddy JO, Simmonds P. The use of human sewage screening for community surveillance of hepatitis E virus in the UK. J Med Virol. 2016;88(5):915–8.10.1002/jmv.24403Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Chatterjee A, Ali F, Bange D, Kondabagil K. Isolation and complete genome sequencing of Mimivirus bombay, a Giant Virus in sewage of Mumbai, India, Genomics. Data. 2016;9:1–3.10.1016/j.gdata.2016.05.013Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Ouardani I, Manso CF, Aouni M, Romalde JL. Efficiency of hepatitis A virus removal in six sewage treatment plants from central Tunisia. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(24):10759–69.10.1007/s00253-015-6902-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Bibby K, Fischer RJ, Casson LW, Stachler E, Haas CN, Munster VJ. Persistence of ebola virus in sterilized wastewater. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2015;2(9):245–9.10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00193Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Ruggeri FM, Bonomo P, Ianiro G, Battistone A, Delogu R, Germinario C, et al. Rotavirus genotypes in sewage treatment plants and in children hospitalized with acute diarrhea in Italy in 2010 and 2011. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(1):241–9.10.1128/AEM.02695-14Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Han TH, Kim SC, Kim ST, Chung CH, Chung JY. Detection of norovirus genogroup IV, klassevirus, and pepper mild mottle virus in sewage samples in South Korea. Arch Virol. 2014;159(3):457–63.10.1007/s00705-013-1848-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Martínez Wassaf MG, Pisano MB, Barril PA, Elbarcha OC, Pinto MA, Mendes de Oliveira J, et al. First detection of hepatitis E virus in Central Argentina: Environmental and serological survey. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(3):334–9.10.1016/j.jcv.2014.08.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Lodder WJ, Rutjes SA, Takumi K, de Roda Husman AM. Aichi virus in sewage and surface water, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(8):1222–30.10.3201/eid1908.130312Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Fumian TM, Vieira CB, Leite JPG, Miagostovich MP. Assessment of burden of virus agents in an urban sewage treatment plant in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Water Health. 2013;11(1):110–9.10.2166/wh.2012.123Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Di Martino B, Di Profio F, Ceci C, Di Felice E, Marsilio F. Molecular detection of Aichi virus in raw sewage in Italy. Arch Virol. 2013;158(9):2001–5.10.1007/s00705-013-1694-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Kamel AH, Ali MA, El-Nady HG, Deraz A, Aho S, Pothier P, et al. Presence of enteric hepatitis viruses in the sewage and population of Greater Cairo. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(8):1182–5.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03461.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Hamza IA, Jurzik L, Überla K, Wilhelm M. Evaluation of pepper mild mottle virus, human picobirnavirus and Torque teno virus as indicators of fecal contamination in river water. Water Res. 2011;45(3):1358–68.10.1016/j.watres.2010.10.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] La Rosa G, Pourshaban M, Iaconelli M, Vennarucci VS, Muscillo M. Molecular detection of hepatitis E virus in sewage samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(17):5870–3.10.1128/AEM.00336-10Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Fumian TM, Leite JPG, Castello AA, Gaggero A, Caillou MSLD, Miagostovich MP. Detection of rotavirus A in sewage samples using multiplex qPCR and an evaluation of the ultracentrifugation and adsorption-elution methods for virus concentration. J Virol Methods. 2010;170(1–2):42–6.10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.08.017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Sdiri-Loulizi K, Hassine M, Aouni Z, Gharbi-Khelifi H, Sakly N, Chouchane S, et al. First molecular detection of Aichi virus in sewage and shellfish samples in the Monastir region of Tunisia. Arch Virol. 2010;155(9):1509–13.10.1007/s00705-010-0744-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] La Fauci V, Sindoni D, Grillo OC, Calimeri S, Lo Giudice D, Squeri R. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) in sewage from treatment plants of Messina University Hospital and of Messina city council. J Preventive Med Hyg. 2010;51(1):28–30.Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Victoria M, Guimarães FR, Fumian TM, Ferreira FFM, Vieira CB, Leite JPG, et al. One year monitoring of norovirus in a sewage treatment plant in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Water Health. 2010;8(1):158–65.10.2166/wh.2009.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Tao Z, Wang H, Xu A, Zhang Y, Song L, Zhu S, et al. Isolation of a recombinant type 3/type 2 poliovirus with a chimeric capsid VP1 from sewage in Shandong, China. Virus Res. 2010;150(1–2):56–60.10.1016/j.virusres.2010.02.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Iorio L, Avagliano F. Observations on the Liber medicine orinalibus by Hermogenes. Am J Nephrol. 1999;19(2):185–8.10.1159/000013449Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] König S. Urine molecular profiling distinguishes health and disease: New methods in diagnostics? Focus on UPLC-MS. Expert Rev Mol Diagnostics. 2011;11:383–91.10.1586/erm.11.13Suche in Google Scholar PubMed