Charitable Oversight: Insight from Regulators and Enforcers

-

Lynda Atkins

, Heather L. Weigler

Abstract

Charitable Oversight: Insight from Regulators and Enforcers, examines the critical role of state charity officials in oversight of the nonprofit sector within the United States, including current and anticipated challenges to their regulatory authority. As charitable giving and the number of nonprofit organizations in the U.S. continue to grow, effective regulation is essential to ensuring that donations to charity are used appropriately and for their intended charitable purposes. State charity regulators, who often operate with limited resources, are at the forefront of these efforts, working to detect and prevent fraud, mismanagement, and other violations of law. The article begins with a discussion of the educational initiatives undertaken by state regulators to address potential compliance issues within the charitable sector. By providing training and guidance to nonprofit boards and donors, regulators help ensure that nonprofit leaders are aware of their fiduciary responsibilities and that donors are informed about how to donate wisely. These educational efforts are essential tools in preventing fraud and enhancing accountability, particularly given the limited resources available for enforcement in many states. Enforcement strategies are another central focus of the article. Charity regulators often employ a blend of progressive-enforcement methods, such as inquiry letters or informal resolutions, and more formal actions, including lawsuits and multistate enforcement initiatives. The paper highlights the importance of multistate collaboration, which has enabled state charity regulators to leverage their combined resources to target wide-spread fraud and pursue comprehensive actions that might not be possible if each state acts alone. For example, enforcement cases, brought by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and multiple states against fraudulent charities and deceptive solicitations, have had broad, nationwide impact. The paper raises concerns about the limited capacity of the IRS to serve as an effective gatekeeper. The IRS’s adoption of Form 1023-EZ in 2014, intended to streamline the tax-exempt application process, has led to a sharp increase in the number of organizations granted tax-exempt status, yet with fewer controls to verify their eligibility. For example, a substantial percentage of organizations using Form 1023-EZ may not actually qualify for the tax-exempt status they receive, creating added regulatory burdens for state charity officials who must monitor compliance with their limited resources. The article also addresses how technological advancements are reshaping the landscape of charitable giving and regulation. Digital platforms, crowdfunding sites, social media, and the growing popularity of online donation portals have made fundraising more accessible but also present new regulatory challenges. Regulators are increasingly faced with questions about the applicability of traditional laws to digital fundraising methods, the risks associated with online payment platforms, and the potential for AI-driven fraudulent solicitations that can manipulate donors with personalized, deceptive messages. Future challenges in the regulatory environment include the expected increase in the number of charitable organizations, an increasingly globalized solicitation landscape and social and environmental factors that result in more frequent disaster-related giving. The article argues that these changes will require regulators to expand multistate collaboration and develop more efficient systems for information sharing, cross-jurisdictional investigations, and collective enforcement actions. In conclusion, the authors advocate for expanded educational outreach and a strengthened network of collaboration among state charity regulators as essential to sustaining effective oversight of the nonprofit sector. By fostering a culture of compliance through education and leveraging collective resources for enforcement, state charity regulators can better protect donors, ensure transparency, and promote the health and integrity of the charitable sector in the United States. The article suggests that, with continued adaptation to technological and societal changes and more collaboration, charity regulators can effectively navigate the future challenges facing nonprofit oversight, safeguarding both public trust and charitable missions in an evolving landscape.

1 Introduction

In the United States, government oversight of the charitable nonprofit sector rests primarily with the states. Attorneys General are charged with defending the public’s interest in the trillions of dollars in charitable assets held by nonprofits and protecting from waste and abuse the billions of dollars generous Americans donate to charities annually. Authorized by statute and common law, Attorneys General have the power and authority to investigate misappropriation of charitable funds, breaches of fiduciary duty and self-dealing by directors, and fraud.[1] It is the Attorney General (and often only the Attorney General) who can pursue a charitable trustee who takes funds held in trust for scholarships for under-privileged children, seek a remedy when someone takes money donated for cancer research and uses it for private gain, take action to ensure that the hundreds of millions of dollars from a nonprofit hospital sale are used to continue to serve the community, ensure that the restricted endowment of a private college or university benefits the public as donors intended, or assure that a decedent’s testamentary charitable gifts are fulfilled. In many states the Attorneys General are assisted in this oversight task by Secretaries of State or other government agencies that are responsible for registering charities and fundraisers and, sometimes, enforcing those registration requirements.[2]

How Big is the Nonprofit Sector?

|

State laws authorizing oversight of charitable assets, state approaches to seeking compliance with those laws, and the resources states devote to enforcing those laws vary widely,[3] but the states share the common goals of safeguarding charitable assets for public benefit and fighting fraud.[4] The job of furthering these common goals and safeguarding the public’s assets – and the public’s trust – rests with state charity officials.[5] These charities officials are connected through an exceptionally strong network, the National Association of State Charities Officials (NASCO). NASCO is open to charities officials from every state and territory. Each year NASCO, with support from the National Association of Attorneys General, organizes a conference on charities regulation that includes at least one private day where government officials (including staff from relevant federal agencies) can discuss regulatory and enforcement topics related to current issues. These conferences facilitate professional development and relationship building that enhances interstate cooperation and resource sharing. Connected through their shared goals of protecting charitable assets from fraud, waste, and abuse, NASCO members serve as informal mentors to attorneys new to charities oversight, freely share knowledge and expertise on the sometimes-arcane ins and outs of charities enforcement and provide institutional history regarding past actions and issues.[6]

This paper is authored by a handful of these state charity officials[7] from across the country, representing states of various sizes and approaches to charity oversight, and including offices of both Secretaries of State and Attorneys General and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Collectively the authors have more than 150 years of experience in charities oversight. In their careers they have seen the number of public charities triple, wholesale changes in the manner that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) grants tax-exempt status to charitable organizations, the transfer to electronic filing from paper-based registration systems, an evolving legal landscape, and fundamental changes in how charitable donations are solicited (such as email solicitations, social media appeals, and online giving portals).

This paper provides the group’s personal perspectives on government oversight of the charitable sector and the challenges faced by charity officials, both now and in the future in four key areas: 1) education – both of donors and of nonprofit board members; 2) enforcement efforts seeking to protect against deceptive and fraudulent charitable solicitations; 3) charitable registration; and 4) protecting charitable assets held in trust from fraud, waste, and abuse. Not every state in this group or in the country approaches these issues the same way, and different statutory frameworks and policies guide the efforts of individual states, but these four issues, in some combination, form the core of the charitable oversight work of all the states.

Common to the discussion of these core topics are several factors that shape government oversight now and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. The most obvious of these is the impact of technology on virtually every aspect of the work, from accepting online registration filings and disseminating education messages via social media to trying to apply 20th century laws to 21st century solicitation methods. Whether thinking about crowdfunding, online giving platforms, social media influencers, online gaming, NFTs, cryptocurrency, or texting for donations, new challenges abound, including whether charitable solicitation laws apply at all, whether and when registration is required, and how to effectively investigate and find bad actors (especially if they are offshore).

The rapid growth in the number of charitable organizations also brings challenges. In the last 25 years the nonprofit sector has grown substantially.[8] From 2020 through 2023 alone, more than 300,000 new charitable organizations were granted tax exempt status.[9] This increase is facilitated by the IRS’s 2014 adoption of a streamlined process for charitable organizations applying for tax exempt status using a new Form 1023-EZ.[10] A 2022 report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration determined that “the information provided on the Form 1023-EZ is insufficient to make an informed determination about tax-exempt status and does not educate applicants about eligibility requirements for tax exemption.”[11] A Taxpayer Advocate Service study of organizations whose 1023-EZ applications were approved between 2015 and 2019 found that between 26 and 46 percent of the organizations did not qualify for tax-exempt status.[12] The report found that the 1023-EZ’s weaknesses and the fact that the IRS examines less than one percent of tax-exempt organizations each year “increases the risk of fraudulent or ineligible organizations receiving tax-exempt status and operating with little chance of detection including fictitious organizations that may potentially commit illegal acts, such as preying on unsuspecting taxpayers for donations or funding terrorist organizations.”[13]

IRS use of the Form 1023-EZ has reduced barriers to entry to the non-profit sector but fails to serve as a screening tool to deter and detect ineligible organizations,[14] thus increasing states’ regulatory and enforcement burdens.[15] Even as the number of charitable organizations has grown, state resources allocated to oversight largely remain static. While state governments routinely work to do more with less, sometimes less is just less.

The work of state charity officials is also affected by natural disasters and mass tragedies. It is at these times of crisis where government officials may need to devote additional resources to important consumer educational messages, monitoring fundraising efforts for potential scams, and working with state and local members of the nonprofit sector. Other societal issues, such as school closures due to changes in birthrate and enrollment patterns, have an impact on charity oversight often resulting in the need for additional resources.

In addressing these challenges, now and in the future, government officials recognize the power of collective action. Whether in the everyday sharing of information, tips, and trainings, or organizing a full blown 50-state multistate/FTC action, working together lightens the load, allows for shared expertise and resources, and furthers the individual goals of every state. This is largely possible because the basic oversight function remains the same – and has largely been unchanged for the past 300 years – safeguard charitable assets for their intended charitable purposes and work to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse.[16] The nature of charitable organizations requires this oversight. Almost without exception, only a state Attorney General is empowered to enforce a donor’s charitable gift after they are dead. Often, the state Attorney General also has sole authority to enforce a charitable gift even during the donor’s life. Unlike for-profit organizations, a nonprofit’s board does not have an ownership or financial interest in the operation of the nonprofit, so there is no financial incentive for rigorous board oversight. Moreover, donors often have no way of knowing if they have been defrauded because they cannot verify that their donations have been spent appropriately. Donors and legitimate organizations depend on regulation and state enforcement to protect them and their charitable missions. Cooperation between regulators and legitimate charitable organizations to protect charitable assets and address fraud ensures a healthy charitable sector that can effectively serve the public good.

2 Education and Outreach

2.1 State Charity Regulators and the Role of Outreach and Education

As the saying goes, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” The adage rings true when it comes to governmental efforts to educate donors about wise giving and educate nonprofits and their leaders about compliance where the leaders are often the first line of defense against illegal or unethical practices. Deceptive and fraudulent fundraising can be minimized if donors research the charities to which they donate and plan their giving. Similarly, all types of pernicious behavior by charities, board members, and charitable trustees can be reduced, if not prevented, through effective education to charitable boards about legal requirements to safeguard charitable assets from loss, waste, and abuse, avoid self-dealing, and meet other fiduciary responsibilities. Many states also undertake outreach to the public to alert them to the responsibilities and services provided by state charity officials. This helps the public access the resources they need to ensure a healthy charitable sector. For these reasons, even though approaches to outreach and education are as varied as the states, many engage in ongoing communication efforts to educate both donors and charitable organizations.[17] In an era of limited enforcement resources and a growing charitable sector, effective education and outreach is key.

2.2 Donor Education

Preventing donors from being scammed preserves charitable assets and ensures that donations will be used for the charitable purposes for which they were intended.[18] Encouraging wise giving to legitimate and effective charities that demonstrate integrity, transparency, and accountability further ensures that limited charitable resources are used to support charitable missions. Raising awareness of charity fraud and government actions to stop it can also increase consumer reports of deceptive charitable solicitations or questionable practices by charities, which in turn helps enforcers identify investigative targets. Efforts to educate donors range from posting educational materials and information about registered charities and fundraisers on websites to active campaigns alerting the public about the importance of wise giving. Such campaigns are often tied to particular times of year or precipitated by enforcement actions or other current events.

Many states, as well as the FTC and the IRS post educational materials about wise giving on their websites.[19] There is no magic bullet that can protect donors, but uniformly the message is to research before giving and to give wisely. Many states that register charities and fundraisers assist such research efforts by providing specific information about individual charities and their fundraising campaigns.[20] This can include information like the names of fundraisers hired by a charity, the amount that the charity paid the fundraiser, and the amount of donations that the charity spent on charitable programs. Several states provide searchable databases that allow donors to look up financial information reported by individual charities.[21] In some cases, states prepare comparative compilations of fundraising campaigns for the public’s use when making donation decisions.[22]

States often engage in media campaigns centered around holidays such as Veteran’s Day and year-end charitable giving to highlight the need for wise giving. In recent years many states and the FTC have participated in the International Charity Fraud Awareness Week and posted educational messages around Breast Cancer Awareness month or other giving events like “Give Big” the first week in May. Increasingly, current events call for immediate donor education. As noted, disasters and mass tragedies spur both an increase in giving and in fraud, making it especially important for timely and effective advice on how to avoid charity scams and donate wisely. Messaging can include public service announcements, social media campaigns, blog posts, media blitzes, and other strategies.

Enforcement actions also present education opportunities. Most offices issue press releases announcing legal actions, but many government agencies do much more. Both multistate actions and sweeps, discussed infra, provide exceptional opportunities for education campaigns. Actions targeting sham charities or deceptive fundraising highlight the importance of wise giving. Additionally, press attention alerts the public to the important work of charities regulators and encourages the public to file complaints about improper activities by charities or fundraisers. They also signal to the charitable community that regulators are paying attention, hopefully encouraging charities to live up to their fiduciary obligations and avoid becoming the target of an enforcement action.

But there are ongoing challenges with donor education efforts. Few states have the resources for marketing and media specialists who can develop campaigns that can compete in today’s media environment.[23] Moreover, accessing and using social media is often limited, if not prohibited, by many government agencies and these barriers can limit the reach of education messages. How can states effectively educate when scammers are on TikTok?

Evolving technology presents further donor education challenges. What advice do donors need when donating through online giving portals or crowdfunding sites? How can donors be inoculated against deep fakes using AI to simulate trusted charities? Is donating cryptocurrency safe? State officials wrestle daily with providing effective advice that does not stifle innovative fundraising approaches and protects donors. However cutting-edge the technology or new-fangled the payment mechanism is, it seems likely that the tried-and-true advice will still protect donors who listen to it: research before you give and know where your money is going and how it will be used. Give wisely.

2.3 Educating Charities About Legal Responsibilities

Educating charities, fiduciaries, and their advisors about their responsibility to protect and preserve charitable assets promotes legal compliance and helps prevent misfeasance and malfeasance. Headlines screaming “Board Asleep at the Wheel While Funds Embezzled” can largely be avoided by waking up board members with effective training. Outreach efforts accomplish regulators’ goals of protecting charitable assets and enabling safe giving for donors.

Most Americans serving on the boards of charitable organizations seek to make a positive difference in their communities, but many do not understand the fiduciary duties they owe to their organization, its donors, and the public. Because most charities are small, local, grass-roots organizations[24] that typically do not have the resources to consult with attorneys or other professionals, board training initiatives are especially important. Embezzlements from youth sports organizations or school-based parent groups or mismanagement at local animal shelters can tear apart communities, destroy the public’s trust in charitable organizations, and inevitably create firestorms of bad press that include questions about the government’s failure to catch the problem. Helping these organizations protect themselves and their assets is critical. State charity offices, especially those that are in contact with these organizations annually because they require registration and/or reporting, are well-situated to provide that education and outreach.

Most states maintain robust websites that provide a wide range of information about and guidance for charities and the fundraising professionals engaged by them.[25] These websites include topics relating to fiduciary and legal duties, specialized publications that address best practices for financial controls, guides for businesses interested in working with charities, advice for public entities in funding charities, and a host of other topics covering the wide range of questions and concerns fielded by these state offices.[26] But websites alone do not reach all charities, especially smaller organizations. Some regulators increase the visibility of the importance of proper board governance practices by providing in-person presentations and training. Others offer recorded and live webinars and videos.[27]

Ohio’s new Charitable University program takes training of charitable fiduciaries beyond websites and guidebooks.[28] Through an online training portal that tracks individual progress, users access videos and written resources on board governance, governmental filings and recordkeeping, fundraising, and financial activities. After completing at least one video in each of the four learning areas, the Ohio Attorney General lists the names of graduates and organizations on its webpage.[29] All nonprofits receiving funds from the office of the Ohio Attorney General must demonstrate that at least one-half of their board members have completed Charitable University. Requiring Charitable University graduation has also provided the Ohio Attorney General’s Office with a new tool for resolving complaints and investigations short of litigation, and in formal actions can serve as an injunctive provision required to improve board governance practices.[30] Other funders and partners across the state have developed requirements and policies encouraging board members of partner agencies to complete Charitable University.[31]

Evolving technology poses new challenges here, too. In addition to training about board member obligations, charities will need ongoing access to information about how to best protect their organizations, beneficiaries, and donors from a growing number of online threats such as cybersecurity challenges and fraudulent fundraising activities through online platforms. State government officials need to understand this threat environment and how to respond to it before they can provide effective guidance, but as threats evolve it can be difficult for resource-challenged offices to develop that expertise. To combat these challenges, states will need to leverage their resources by partnering not just with each other and the federal government but also through strengthened relationships with leaders in the nonprofit sector.

3 Enforcement

As long as charitable giving has existed, so too has charity fraud. And for as long as charity fraud has existed, so too have government efforts to stop it. Lying to donors in the name of charity harms both donors and the causes they support and discourages public generosity. In the United States, combating charity fraud largely falls to the states.[32]

3.1 Legal Authority to Combat Unlawful Charitable Solicitations

State Attorneys General and other enforcement authorities use various tools to protect the public and the charitable sector from unlawful solicitations, from educating charities and fundraisers about their legal obligations to filing criminal charges.[33] Fraudulent and deceptive charitable solicitations are unlawful in every state[34] and, when done by for-profit fundraisers or sham charities, are prohibited by the Federal Trade Commission Act.[35]

State laws grant Attorneys General broad powers to investigate misleading solicitations and pursue civil suits against charities and their fundraisers.[36] State consumer protection statutes also address unlawful charitable solicitations and combat abusive or unfair fundraising tactics, especially in the context of telephone solicitations.[37] Where conduct violates the federal Telemarketing Sales Rule,[38] state attorneys general may initiate federal district court proceedings to enjoin violations of, and enforce compliance with, the TSR,[39] although this authority is seldom used outside of joint actions with the FTC.

3.2 Progressive Enforcement

Mindful of the potential adverse impact that formal government action may have on charity, state Attorneys General make efforts to address potential law violations outside of the formal legal process. Often referred to as progressive enforcement, these efforts may be most appropriate where a small number of consumers were affected, there is no evidence of fraudulent intent, and the target of the investigation agrees to correct the violation. Such action typically occurs without fanfare and behind the scenes, but it is a vital part of any enforcement program.

Progressive enforcement may include inquiry letters, warning letters, and investigative reports. In the case of inquiry and warning letters, the communication educates the organization or individual about their legal obligations for charitable activities in the state and provides evidence of knowledge in the event future enforcement action is required. Some progressive enforcement efforts are disclosable public records,[40] while others are shielded from disclosure.[41] Even when publicly disclosable, states that address violations through progressive enforcement rarely make the public aware of the state’s efforts to protect the public interest in lawful solicitations and charitable activity.[42]

3.3 Formal Actions

When progressive enforcement is not sufficient to protect the public, states may take more formal legal action, such as imposing sanctions for solicitations violations through administrative proceedings authorized by the state’s charities statute.[43] An administrative order barring an individual or organization from soliciting until registration violations are corrected protects consumers without requiring the significant investment of resources entailed in bringing a lawsuit.

Many states also pursue pre-litigation resolution when an organization or individual has violated charities and/or consumer protection laws. These settlement agreements are typically known as Assurances of Discontinuance (AODs) or Assurances of Voluntary Compliance (AVCs), which are often are filed with a Court that retains jurisdiction for any action to enforce a violation of the agreement.[44] Filing an AOD or AVC with the Court helps establish a target’s knowledge of both the alleged violations and legal requirements in the event future activities run afoul of state law.[45]

When states are unable to address unlawful charitable activity through progressive enforcement, administrative action, or AODs/AVCs, they may file suit in state court alleging a variety of claims and seeking a variety of remedies, which typically include injunctive relief. Injunctive provisions can range from prohibitions on making false claims, requirements to replace or reform boards of directors, time-limited or permanent bans on solicitation, or even corporate dissolution. Monetary relief available in charity fraud cases typically includes restitution in the form of cy pres, that is, an order provision directing that recovered funds be sent to a legitimate charity that will honor the donors’ intent.[46] Many state statutes also authorize civil penalties or damages for statutory violations.[47]

3.4 Collaborative Actions Targeting Charity Fraud

Whether and when to act against unlawful charitable solicitations is also a question of resource allocation Some state attorneys general have multiple attorneys assigned to charities matters, while in other states a single attorney may be assigned less than full time. For states with few resources devoted to charitable oversight, litigation on their own can be challenging, especially when a target is not located in their state. Collective action is often a more effective strategy for preventing fraudulent and deceptive charitable solicitations.

State charities enforcers and the FTC share the common goal of protecting consumers and preventing fraud. They have long collaborated to combat fraudulent and deceptive charitable solicitations, uniting states behind the common purposes of protecting donors, charities, and the charitable sector from the loss, waste, and abuse created by fraudulent fundraising.[48] Laws in every state,[49] as well as the FTC Act,[50] forbid deception in charitable solicitations. Equally important, the professional connections and the culture of mutual respect and support forged through NASCO provide a strong platform for organizing collective action.

Collective action typically takes two public-facing forms: 1) joint enforcement and education initiatives called “sweeps” where multiple states and the FTC collectively announce law enforcement actions and roll out new education campaigns targeting a particular issue or theme and 2) joint legal actions in which the FTC and/or multiple states investigate charities or fundraisers who have allegedly violated laws enforced by each plaintiff.[51] Sweeps focus attention on topics or types of fundraising that charity enforcers have long identified as rife with false and deceptive fundraising claims. Similarly, joint enforcement actions may target defendants who have been sued by individual states but have not corrected their practices or entities engaged in fraudulent fundraising nationwide whose supposed mission fits within the focus of a particular sweep.

Collective action, no matter the form, serves as a force-multiplier to the individual efforts of the participating states and the FTC, strengthening enforcement capabilities and capturing media attention to springboard consumer awareness of charitable solicitation fraud. Because consumer education is critical in the fight against charitable solicitation fraud, creating concentrated media attention furthers collective education goals.

These collective actions highlight two enduring characteristics of successful charities enforcement: the high level of communication and cooperation within the charities enforcement community and the shared commitment to combatting charitable fraud.

3.5 Sweeps

The FTC and the states first collaborated on an enforcement sweep dubbed “Operation False Alarm” in 1997, which set the stage for all subsequent sweeps.[52] All 50 states participated in the effort to target badge-related fundraising fraud – an unheard level of consensus and cooperation at the time. The sweep included individual enforcement actions by the FTC and numerous states as well as targeted education efforts by participating states who did not bring their own enforcement actions.[53]

The FTC and states have continued to partner on sweeps targeting fundraising fraud through the years, demonstrating the consistently high level of bipartisan support for combatting deceptive charitable solicitations. Sweeps have been organized and announced by the FTC under both Republican and Democratic administrations and the FTC has been joined in these efforts by states across the political spectrum.[54]

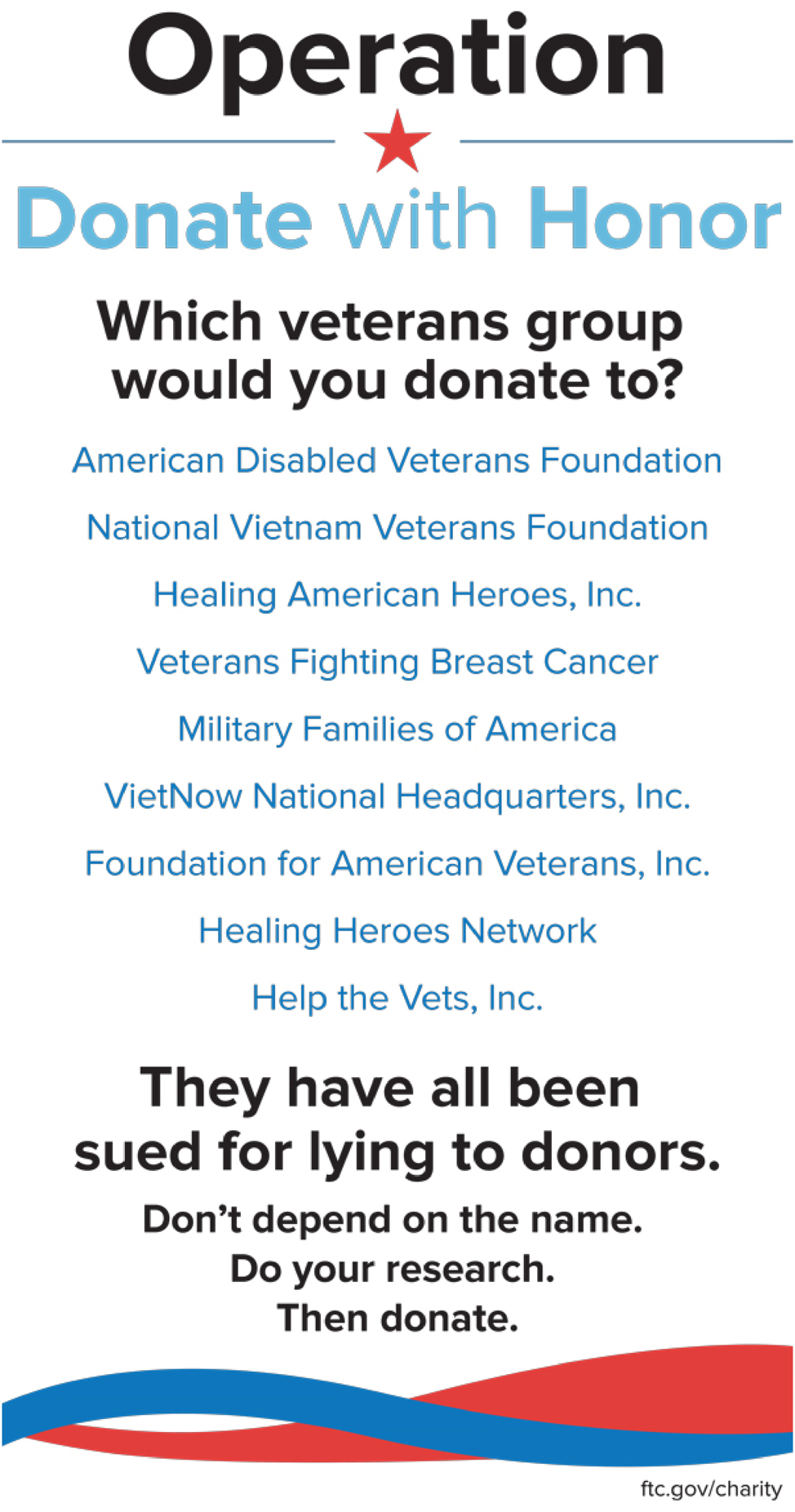

Sweeps can galvanize enforcement actions both large and small. For example, more than 100 enforcement actions were announced in connection with the 2018 “Donate with Honor” sweep.[55] With input from the states, the FTC created and shared an entire suite of new education materials in both English and Spanish.[56]

Sweep education campaigns present win/win opportunities for all participants. States can take advantage of the FTC’s specialized education resources,[57] the FTC can capitalize on the extended distribution of its educational materials, and the increased press attention drives donor education messages – all in service of achieving the shared goal of protecting people from deceptive charitable solicitation.[58]

3.6 Joint Enforcement Actions: Federal/State Actions

In 2015, the FTC and 50 states and the District of Columbia sued the sham charity Cancer Fund of America and related companies and individuals,[59] launching the modern era of joint federal/state enforcement actions. In Cancer Fund, the FTC and 58 state law enforcement partners filed a single complaint in federal district court charging four sham cancer charities and their operators with bilking more than $187 million from consumers.[60]

The Cancer Fund action leveraged state and federal resources on a variety of fronts, from sharing expertise in nonprofit accounting, document discovery, and depositions to drafting the complaint, orders, and settlement negotiations. The united front presented by the states and the FTC ensured the strongest possible result.[61]

The successful Cancer Fund investigation and litigation strengthened existing communications among charities enforcers, highlighting the benefits of group action and indelibly changing the culture of the charities enforcement community. Collaborations on matters of mutual interest, whether informal and nonpublic or involving more formal public-facing actions, are now the norm rather than the exception.

State attorneys general and the FTC share a keen interest in stopping abusive telemarketing conduct, especially robocalls that are deceptive charitable solicitations. The 2021 federal/state action against fundraiser Associated Community Services and related companies and individuals brought together 46 state agencies from 38 states with the FTC to combat deceptive fundraising and to put an end to the companies’ more than 1.3 billion robocalls.[62] Settlements filed with the complaint banned the defendants from fundraising and telemarketing, which ultimately led to the closure of the four corporate defendants.[63]

Joint enforcement actions like Cancer Fund and Associated Community Services offer significant benefits. They pool resources and expertise, capitalizing on the diverse strengths of partners. They make it possible for smaller states to participate in actions they might not have brought on their own and serve as a training ground for attorneys new to the charities enforcement world.[64] More substantively, joint actions prevent the “whack-a-mole” problem that can happen when a state takes individual action against a bad actor, driving that bad actor out of their state but allowing it to continue fraudulent and deceptive conduct everywhere else.[65] Relative to individual actions, joint enforcement actions increase bargaining power at all stages of the matter, whether negotiating responses to civil investigative demands or settlement terms. Targets understand the very negative potential for defending against actions in multiple state courts and the attendant risk of high legal fees. This helps obtain strong injunctive relief; settlements in federal/state actions routinely include fundraising bans against individuals and require the closure or dissolution of corporate defendants.[66]

3.7 Joint Enforcement Actions: Multistate Actions

Where fraudulent, deceptive, or otherwise unlawful conduct crosses state borders, states will often act jointly to leverage resources to obtain the strongest possible relief. Such actions allow attorneys general to stand in the shoes of charity fraud victims and ensure that donors’ charitable intent is fulfilled, as well as redress the harm to the nonprofit sector caused by charitable solicitation fraud. These actions provide many states with an enforcement presence that, due to resource constraints, they cannot achieve on their own.[67]

In recent years, there are several examples of coalitions of states working together to target scam charities that solicited nationwide. Joint actions have successfully shut down scam charities, obtained strong injunctive relief, including bans on officers or directors soliciting charitable contributions or serving on nonprofit charitable boards, and resulted in monetary recovery that would have been impossible or difficult to achieve had any one state acted alone.[68]

Increasingly, state charities enforcers work together to tackle new and novel fundraising practices. Many collaborations are informal, behind-the-scenes information exchanges, often fostered by NASCO committees and specialized webinars.[69] Such sharing of expertise is another key benefit of collaboration. One joint enforcement action addressing an emerging fundraising practice occurred in 2020, when a group of 23 states announced a settlement with PayPal Charitable Giving Fund, targeting problematic disclosures provided to donors making contributions through the PayPal Giving Fund’s online giving platform.[70]

The case for collective action remains strong. Charities and professional fundraisers that solicit on a nationwide basis can raise millions of dollars annually. Amounts raised in any particular state might not be dramatic, or on their own trigger an investigation, but collectively such national campaigns can be significant – and when they are based on fraudulent and deceptive solicitations can siphon huge sums from legitimate charitable causes. Historically, fundraising campaigns with a national focus were limited to organizations that solicited through direct mail or telemarketing, but state regulators expect to see more and more fundraising campaigns touching their citizens digitally – and unscrupulous fundraisers and organizations can expect to see more and more joint enforcement efforts. Working with each other and the nonprofit sector to better identify and root out fraud makes space for real charitable organizations to thrive.

3.8 Enforcement Consideration: The First Amendment

Government enforcers seeking to protect the public against deceptive and fraudulent charitable solicitations must be mindful of the significant constitutional protections afforded charitable speech, which courts deem to be fully protected.[71] Courts seek to protect nonprofit organizations from government action that might chill or impermissibly burden a charity’s right to speak (and, in the case of required disclosures, not to speak). Case law in this area is ever evolving as courts balance states’ compelling interest in protecting citizens from fraud and charities’ rights to free speech.

Some bedrock principles are clear, however. The Supreme Court held in Madigan v. Telemarketing Associates that the First Amendment does not protect fraudulent and deceptive charitable solicitations speech or otherwise prohibit the government from acting against such fundraising practices.[72] Thus, to survive constitutional challenge, any action brought by the government must fit within Madigan’s parameters. Any government action should focus on specific, affirmative misrepresentations about charitable programming, such as representations that the organizations engaged in particular programs or actions. Representations can be false because the organizations do not spend a single penny on the described program or, as in Madigan, the amount of funds spent on charity programming can be “incidental” to private benefit. In addition, it seems likely that some level of knowledge of the fraudulent and deceptive practices must be alleged and demonstrated to survive constitutional scrutiny, although the level of knowledge required remains an open question.[73]

Cases interpreting Madigan in the context of charitable solicitations are exceedingly rare.[74] Other challenges to state authority to regulate charitable fundraising have become more frequent, including the recent Supreme Court case, Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, striking down a state requirement that nonprofits regularly file donor lists with states.[75]

3.9 Enforcement Challenges: Technology Concerns

Government efforts to combat charity fraud in the 21st century face challenges both new and old. Some are attributable to advances in technology and the changing ecosystem of giving, while others stem from the surrounding legal environment. Advances in technology range from changes in cost and delivery of telemarketing, and new mechanisms for processing payments, to the ever-expanding use of online and digital fundraising.

Technology makes old methods of fundraising more cost effective. Telemarketers in offshore telephone rooms using voice over internet protocol (VoIP) technology can bombard U.S. residents with billions of calls.[76] VoIP, which can act as a gateway for calls originating overseas to enter the domestic telephone network, obscures the call’s originating location from potential donors.[77] Offshore phone rooms and VoIP solicitations present unique enforcement and investigative challenges for state and federal charity regulators, whose subpoena power does not easily extend beyond national borders.

Technology also fosters connections – both real and imagined – in the digital world. In the digital world it is easier for donors to find causes and charities to support, and easier for tech-savvy charities (or their fundraisers) to reach a worldwide audience.[78] Donors can be solicited – often specifically targeted – on multiple channels, from email, social media, online gaming, texting, in-app ads, and banner ads surrounding search results. Such digital marketing is far cheaper than more traditional labor- and resource-intensive fundraising like telemarketing, direct mail, and special events (which are all still common). Digital appeals can be made in real time, almost immediately seeking support in response to tragedies or disasters, or messages can “go viral” exciting the imagination of donors and triggering millions of dollars in contributions.

While these developments give legitimate charities increased access to financial support, they also provide new and expanded opportunities for bad actors.[79] As solicitations become more targeted to individual consumers, unscrupulous fundraisers can more easily leverage consumer data to mislead consumers into making charitable contributions. Additionally, fundraisers are aware of digital marketers’ ability to create dark patterns[80] that might, for example, unfairly prey on donors’ emotions or lure them into unknowingly signing up for recurring donations.[81] The increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI) also poses a risk to the donating public. It is easy to imagine a future in which unethical AI is used to make solicitations of an unsophisticated donating public ill-equipped to resist its targeted appeals, expanding the need for regulators to collaborate on donor education and enforcement.

These advancements present investigative and enforcement challenges. When investigating suspected fraud or deception it can be difficult to identify who the parties are in a transaction – or even that a solicitation occurred. Given the personalized, algorithm-driven delivery of charitable solicitations to individual donor feeds, it can be difficult for investigators to see and capture solicitations, and if money is directed offshore, those donations can be nearly impossible to trace. Even requests to donate to well-known charities can have hijacked hyperlinks diverting payment elsewhere (robbing both the charity and the donor). Bad actors may set up an array of corporate entities to cloak their conduct and fly-by-night scams may siphon money from donors and then dissolve well before enforcement authorities can act. And if the operators are outside the United States, there is little that civil enforcement authorities can do.

Digital marketing presents regulatory challenges as well. Many state charitable solicitation statutes were written with direct mail or telemarketing in mind. Most such statutes require a minimal level of disclosures designed to help donors understand who they are contributing to and (in those states that register charities and professional fundraisers) advising them that they can find information about the charity and its professional fundraisers at their attorney general or secretary of state’s website. Given the space and design constraints of new forms of digital marketing, these donor protections may be insufficient and outdated. Additionally, new online vehicles for charitable giving may fail to provide donors with adequate information about how the giving portal works, such as whether there are fees deducted from a donation or whether a donation goes directly to the charity. The multistate settlement with the PayPal Giving Fund, discussed supra, highlights potential issues – and remedies for donor confusion – surrounding online giving platforms. There, the states’ collective action not only came to an agreement with the individual target, but it also provided a road map to all online giving platforms for compliant disclosures.[82]

Digital marketing is also exacerbating an old problem – consumers do not complain about fraudulent and deceptive solicitations, often because they do not know that their solicitation was not used for the charitable purposes described.[83] This makes learning about and seeking to resolve law violations even more difficult. Duped donors are sometimes embarrassed or reluctant to publicly come forward as someone who has fallen for a scam. The ease and speed with which a donor can be misled by a scam charity or paid fundraiser can also be attributed to the fleeting nature of a transaction involving a small dollar donation. For example, a donor is not likely to follow up on whether their rounded-up contribution at the grocery store checkout actually went to support the very worthy cause or purpose presented to them by a fundraiser. In the absence of donor complaints, a fundraising scheme can go on for years, undetected, before a problem can be identified and fully investigated. Thus, educating donors about the importance of reporting deceptive solicitations is both challenging and important.[84]

Even as digital marketing presents new technological challenges, in an everything-old-is-new-again moment, states are also seeing increased in-person solicitations outside of stores and in other public places. These solicitations, too, present their own set of enforcement challenges, including solicitors frequently changing locations to avoid detection, making verbal misrepresentations that require consumer testimony, and receiving of cash donations that are difficult to track.

Finally, globalization has brought greater awareness of charitable causes beyond the borders of a consumer’s state and nation. Predictions for increasing environmental disasters due to climate change, international conflicts, the potential for social unrest, and underfunded public services are likely to result in ever-increasing solicitations. One way regulators in an already resource-limited environment can adapt is through greater collaboration and information-sharing. If past is prologue, that collaboration will result in protecting consumers by decreasing the barriers individual actors face in combating fraudulent solicitations.

4 Registration of Charities and Fundraisers

Charitable registration encourages transparency, accountability, cooperation, and trust in the non-profit sector, benefitting donors, charitable beneficiaries, legitimate organizations, and the public. Charities are generally exempt from federal and state taxes (including in many states sales tax, franchise excise and business taxes, and property tax) because they promise to operate primarily, if not exclusively, for the benefit of the public. These tax benefits come with additional obligations of transparency and government oversight not imposed on for-profit companies and private individuals who do not enjoy the same tax advantages. Part of that oversight in 41 jurisdictions (40 states and the District of Columbia) involves some level of registration and/or reporting by charitable organizations and/or their fundraisers.[85]

Charitable registration provides basic information to government officials and the public about organizations operating within their borders. It also provides a baseline check on the competence of a charity’s officers and directors because an organization that fails at such a core task may have larger problems. In some states, registration is required for eligibility for public grants and contracts, likely for the same reason – organizations that are unable to register are likely to be similarly unable to successfully administer the taxpayer’s funds. Other states require registration to access government programs.[86]

Registration and reporting information can assist in identifying and prosecuting charity fraud and other law violations and provide a formal mechanism for oversight of charitable solicitations by the state. Charities’ annual reports can serve as a resource for enforcement authorities. For example, annual financial reports that reflect a significant drop in assets between reporting years may signal financial mismanagement and the breach of directors’ and officers’ fiduciary duties. In addition, state regulators use data mining techniques to search registration and reporting information to identify compliance issues. Even without data analytics, registration requirements create an implicit sentinel effect. Filing annually reminds organizations that there is government oversight and accountability for how they use charitable assets.

Registration facilitates the educational efforts described in. Many states use data from registration and reporting filings to produce free public resources about charities in their state. These resources provide citizens with timely information about charities active in their state.[87] In some states, private organizations use data from charities’ registrations and reports to identify and provide detailed programmatic, operational, and financial information on local charities.[88] Governmental authorities are not alone in their interest in the information provided by charitable registration. Many donors, funders, and beneficiaries depend on access to the data that registration provides. So too does the media, which uses public registration information in connection with investigative reporting on charity misconduct and related issues.

Registration creates transparency that helps to protect donors and charities alike. It can help ensure fidelity to charitable purposes, protect charitable assets from fraud, waste, and misapplication, and allow regulators and members of the public to evaluate a charity’s contribution to the public good. Registration requirements can also help instill public confidence that any given charity, and the charitable sector as a whole, are reputable and trustworthy because they are publicly accountable.[89]

4.1 Varied Approaches to Registration

States approach both the process and the substance of registration in a variety of ways. Some require the registration of all charitable trustees;[90] others limit the registration requirement to those charitable organizations that engage in charitable solicitation or persons or entities that solicit on behalf of charitable organizations, such as professional fundraisers and commercial co-venturers.[91] Many states bifurcate the enforcement and registration functions, assigning enforcement duties to the Attorney General and oversight of the registration and reporting process to another state agency, typically their Secretaries of State. Other states house both the enforcement and registration functions in the office of the Attorney General.[92]

Documents and information required to register and report also vary. In addition to basic information about the charity, states may ask charities to provide articles of incorporation, IRS tax determination letters, and bank account information, and require that the registration form be signed by two officers.[93] In many states, charities and professional fundraisers must post bonds, submit fundraising contracts and other information related to a fundraising effort.[94] A handful of states that prohibit felons from working as charitable solicitors require fundraisers to file the names of individual solicitors.[95] In addition, charities and fundraisers may be required to file financial accountings annually or at the end of fundraising campaigns.[96]

When charities or fundraisers fail to comply with registration and reporting requirements many states take steps to encourage compliance before resorting to formal action, including letters, calls, and even in-person visits. A number of states post information on their websites about suspended noncompliant charities.[97] Some states impose financial penalties on those that fail to register initially or submit their annual reports timely.[98] Others take formal action, filing administrative actions against charities violating state registration laws.[99]

4.2 Challenges Facing Charities Registration

Even as the basic need for oversight of charities and charitable assets pledged to the common good continues, challenges to charities registration loom. These include:

New online fundraising methods, including the growth of online charitable giving platforms, crowdfunding, social media asks, mobile giving, solicitations by text, and innovations yet to come.

Legal challenges to registration requirements.

Increased numbers of charities, many of which are led by directors or trustees who are unfamiliar with compliance requirements.

The diminished role of the IRS as a trusted gatekeeper of tax-exempt status, exacerbating the chronic lack of state resources devoted to charitable oversight.

In an increasingly digital world, most states have yet to shift their oversight model to accommodate the changing landscape of charitable giving. Even though many donors now choose to contribute through online giving platforms,[100] most state registration statutes do not address an online giving model. These laws were adopted when solicitations were disseminated via direct mail and telephone, not social media, SMS messaging, or email.[101] Shifting to cover these new forms of fundraising may require new legislation, rule-making, or other changes to the status quo. California is leading the way in such legislative efforts. In 2022, the state legislature approved the first law to regulate charitable fundraising online.[102] The law places oversight of charitable giving platforms and fundraising platforms under the control of the California Attorney General’s office.[103] Many regulators are watching as California implements this statute as a potential model for the future.[104] Crowdfunding also operates in a regulatory vacuum. When donations go to crowdfunding campaigns that benefit individuals, there is little to no statutory oversight. Neither the crowdfunding platform nor the individual campaigns are required to register or report how donated funds are spent.

State charities registration schemes also face new legal challenges over required filings. As noted in Section 3, in the 2021 case Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, the Supreme Court struck down a California requirement that nonprofits file with it the Schedule B to their Form 990, that lists the names of large donors.[105] While the Court found that California had a compelling governmental interest in protecting its citizens from fraud, the Court noted that California had failed to prove that it used the Schedule B information as part of its fraud prevention efforts. Given that, the Court found that the requirement “imposes a widespread burden on donors’ associational rights” that was not justified on the ground that the regime is narrowly tailored to investigating charitable wrongdoing and held that “the up-front collection of Schedule Bs is facially unconstitutional”. 559 U.S., at 473, 130 S. Ct. 1577. In the years since Bonta, states have seen other challenges to the collection of individual information from charities, including information core to the states’ oversight functions such as the names of board members or other fiduciaries.

Resources to process submissions, enforce compliance, and update systems, also pose a challenge. The increase in the number of nonprofits granted tax exempt status by the IRS, combined with its streamlined process for review of the applications of 1023-EZ filers, is increasingly burdening state registrars. Some states no longer feel confident that the grant of 501(c)(3) status signifies that an organization’s mission and bylaws will qualify as charitable under their state statutes, necessitating a closer review of all new registrants. In addition, states are seeing an increasing need to explain basic legal requirements to charitable organizations that have received IRS 501(c)(3) recognition. Many states are simply overburdened by the increasing numbers of charities. These challenges are exacerbated in some states by a lack of funding, including funding to improve aged databases with updated, faster, and more user-friendly technology.

Charities registration provides vital information for education and enforcement, helps protect charitable assets from diversion and loss, and can be a tool for donors, funders, volunteers, charitable beneficiaries, and the public to evaluate organizations for their potential to create public good. The recent growth of the nonprofit sector and the changing technological landscape has not been coupled with a similar growth in the resources devoted to overseeing those organizations, creating challenges to the success of regulatory schemes. Innovation, collaboration, and education about the importance of charities registration will be an important part of filling that gap.

5 Oversight of Charitable Assets

Unlike for-profit corporations and standard trusts with known individual beneficiaries, charitable nonprofit organizations and charitable trusts[106] do not have robust checks and balances on illegal and inefficient conduct. Because a nonprofit is not “owned,” there are no board members and stockholders with financial incentives to monitor corporate performance.[107] Donors to nonprofits, unlike purchasers of goods or services, have no access to information as to whether the charity has used their money as they intended. Charitable trusts, unlike their standard counterparts, often have unidentified beneficiaries, leaving no one to hold the trustee accountable if the trustee fails to administer the trust properly. For these reasons, state Attorneys General often stand as the sole protector of the people’s interest in charity and will act against charitable nonprofits and trusts that fail to devote their assets to their charitable purpose.

Given the increasing concentration of wealth and the anticipated transfer of wealth in years to come, including the transfer to charitable organizations, the charitable sector will continue to grow, with some charities controlling significant sums. With more nonprofits, and more donations, there are likely more opportunities for bad actors. Again, in many states, the Attorney General is the only entity authorized to step in to preserve and protect charitable assets for the public’s benefit.[108]

5.1 Nonprofit Organizations

Today, Attorneys General generally oversee nonprofit organizations’ management of charitable assets through a combination of common law visitorial powers and various statutes including the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act, the Uniform Supervision of Trustees for Charitable Purposes Act, the Model Nonprofit Corporations Act, and various solicitation acts.[109] Attorney General oversight of nonprofit organizations runs the gamut from small to large organizations and involves both formal enforcement and informal compliance approaches. While the guiding principle is safeguarding charitable assets for charitable purposes and beneficiaries, the approach of any given office is often dictated by the resources it has available.

Illustrating the range of cases that arise are two recent matters investigated by the Ohio and Minnesota Attorneys General. An investigation by the Ohio Attorney General into discrepancies in the accounts of a local school district’s volleyball booster club resulted in the conviction of a club officer for the theft of more than $9,000.[110] Despite the relatively small amount, that money was intended to be used to help student volleyball players and its loss was significant to that community. On the other end of the spectrum, the Minnesota Attorney General recently filed suit against a multi-million-dollar foundation, its president, a board member, and executive director, alleging that they misused funds, and violated numerous other governance requirements. The lawsuit alleged, among other things, that the president had received at least $21.8 million in charitable assets, of which he steered more than $14.8 million to entities owned or co-owned by a board member. These same entities then paid the president nearly $850,000 in “consulting” fees.[111]

While a $21.8 million dollar lawsuit may deter other bad actors when publicized, sometimes a more informal enforcement approach can also effectively achieve legal compliance. For example, the New York Attorney General’s Charities Bureau used a data mining approach to identify charities that, on their IRS Form 990, reported giving loans to officers or directors, an unlawful practice under New York’s Not-for-Profit Corporation Law. Rather than suing, the Charities Bureau sent out violation notices to the identified organizations. It required those organizations to secure refunds of the sums loaned and to adopt policies to ensure that no future loans would be granted.

While historically, donors primarily supported local charities or well-known national organizations, today, the internet has made it easier to solicit charitable donations across state lines and at the national level. Because many states’ corporate governance statutes do not reach out-of-state charities and enforcing civil investigative demands and other compulsory process in other states is complicated, collaboration between Attorneys General is not only helpful, but in many cases required to effectively investigate and act against charities bent on misusing charitable assets.

5.2 Charitable Trusts

Unlike the law governing nonprofit organizations, which varies from state to state, the law regarding charitable trusts is relatively straightforward. Attorneys General generally have two sources of authority over charitable trusts: common law authority stemming from the 16th century England, unless abrogated by state law, and probate-related acts such as the Uniform Trust Code.[112]

In exercising their authority over charitable trusts, Attorneys General are similarly guided by the principle of safeguarding charitable assets for their intended purposes. Like actions against nonprofit organizations, here too the actions an Attorney General takes will be determined by the resources available and the unique challenges of charitable trust law. For example, absent information available from registration in states where trusts must be registered, Attorneys General may have no idea that a charitable trust exists. Without knowledge of the existence of a charitable trust, the Attorney General cannot act to protect the charitable assets.

Where Attorneys General do learn of a charitable trust, they may seek to preserve charitable assets by filing appearances in probate cases or by telling the parties they will object to a proposed action that harms the charitable asset. Charitable trustees often want to avoid the optics of fighting a donor’s family to protect the charitable gift and may fail to act. Similarly, a common refrain from charities named as beneficiaries of a trust is “we are just happy to get what we get.” Attorneys General may intervene in these actions to make sure that charitable trust assets go to the charities or causes that the donor intended.

Often Attorneys General act to protect treasured community assets held in trust to benefit the community. In 2013, the City of Detroit became the largest US City to file for bankruptcy, having around $18 billion in debt. At the time, the Detroit Institute of Art (DIA) had an art collection valued at around $4.6 billion.[113] The City’s creditors argued the DIA’s collection was city property subject to the bankruptcy estate. In response to a legislative request, the Michigan Department of Attorney General issued an opinion that held that the artwork of the DIA was held in a charitable trust.[114] Approving the plan which preserved the DIA’s collection, the bankruptcy court held “[o]n balance, the Court concludes that in any potential litigation concerning the City’s right to sell the DIA art, or concerning the creditors’ right to access the art to satisfy their claims, the position of the Attorney General and the DIA would almost certainly prevail.”[115] By simply taking a position, the Michigan Department of Attorney General preserved billions of dollars in art for the benefit of Detroit residents and visitors.

When alternatives to litigation are unavailable, Attorneys General can file court actions such as cy pres proceedings, petitions to remove trustees, and objections to accounts to enforce and protect charitable trusts.

States have in general adopted some form of a trust code and probate code, and almost all have the same common law history.[116] Because of this, the actions brought by Attorneys General are similar from state to state, and expertise developed by one state can be shared with others. Offices with limited resources can reach out to their NASCO colleagues in sister states, lean on their experience, and even obtain model pleadings. The network built by state charity officials to share information and knowledge allows a small Attorney General’s office with limited resources to function more like a much larger office.

5.3 Future Challenges

Recently, Attorneys General offices have been sharing information about troubling issues affecting charitable assets on the horizon. These include increases in the number of college closures and hospital consolidations[117] as well as advances in technology and other changes within the nonprofit sector. Other emerging challenges to charitable asset oversight include the growth of Donor Advised Funds (DAFs). DAFs are largely opaque to regulators even though they hold billions of dollars in charitable assets.

The practical effect of these emerging issues on an Attorney General’s office with limited resources is generally to exacerbate their resource issues. For example, in the event of a failing college where wrongdoing is alleged, or a beloved charitable asset is in play, the associated litigation can be massive and require significant resources.[118] Similarly, nonprofit hospital consolidations often have hundreds of millions of dollars at stake and require significant resources, including expert assistance.[119] Regardless, whatever the challenge, Attorneys General will continue to seek to preserve and protect charitable assets for the benefit of the public.

6 Conclusions

Government oversight serves as a crucial safeguard protecting the public’s interest in charitable assets and maintaining the integrity of the charitable sector. State Attorneys General and other charity oversight agencies work tirelessly to defend donor intent, help preserve charitable assets for charitable purposes, and protect the public from fraud, waste, and abuse. These efforts may be prophylactic, such as providing education and outreach to potential donors and fiduciaries and requiring registration and reporting of charitable activity, or remedial, such as multistate and federal litigation targeting bad actors with national presence. Whatever the circumstances, most charities enforcers offer all but the most flagrant scofflaws and wrongdoers paths to compliance that preserve charitable assets.

Government officials often stretch scare resources through collaboration and cooperation with each other and regulated entities, but to ensure state charities enforcers continue to meet future challenges, lawmakers responsible for allocating resources must understand the importance of charitable oversight in promoting the public good. Despite the variations in state laws and approaches, charity officials all share the goal of ensuring the sector operates with transparency and accountability while fulfilling the charitable missions subsidized by the taxpayers through exemptions and deductibility of donations.

Even when they are adequately resourced, state charity officials face many future challenges to their ability to adequately protect the public and legitimate organizations. Both the rapid proliferation of charitable organizations and the evolving technological landscape necessitate ongoing adaptation and collaboration. Cooperation across state lines through information sharing, training, and coordinated action can leverage shared expertise to protect donors, legitimate organizations, and charitable missions, and it will become even more vital to successful charities regulation in the coming years with increasing communication and globalization.

Such cooperation will become more and more necessary as the sector continues to expand and adapt to technological advancements, social shifts, and the increased prevalence of natural disasters and mass tragedies. Those changes will challenge regulators to find new ways to protect consumers and legitimate charities from the harms of fraudulent charitable solicitations and exploitation of charitable assets. If past is prologue, the tight-knit community of charities enforcers will meet the challenge by an increasing focus on sharing information and expertise, strengthening channels for informal communications, and combining forces to address threats to the integrity and transparency of the sector.

Appendix A:

State information about and guidance for charities can be found at the following state regulatory websites:

Office of the Alabama Attorney General

Licensing and Registration

https://www.alabamaag.gov/consumer-license/

Alaska Department of Law

Consumer Protection Unit

https://law.alaska.gov/department/civil/consumer/cpindex.html

Arizona Secretary of State

Veterans Charities Organizations

https://azsos.gov/business/other-services/veterans-charities-organizations

Arizona Attorney General

Charity Scams

Arkansas Secretary of State

Business Services

https://www.sos.arkansas.gov/business-commercial-services-bcs/for-charities

Arkansas Attorney General

Public Protection Division

https://arkansasag.gov/divisions/public-protection/

California Department of Justice

Colorado Secretary of State

Charities Program

Colorado Attorney General

Consumer Protection Section

Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection

Public Charities Unit

https://portal.ct.gov/dcp/dcp-programs-and-services?language=en_US

Delaware Department of Justice

Fraud & Consumer Protection Division

https://attorneygeneral.delaware.gov/fraud/

Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia

Consumer Protection

https://oag.dc.gov/consumer-protection

Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services

Division of Consumer Services

https://www.fdacs.gov/CONSUMERSERVICES

Office of the Florida Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://www.myfloridalegal.com/consumer-protection

Office of the Georgia Secretary of State

Charities Division

Hawaii Attorney General

Tax & Charities Division

Idaho Office of the Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://www.ag.idaho.gov/consumer-protection/

Illinois Office of the Attorney General

Charitable Trusts Bureau

https://illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/consumer-protection/charities/

Office of the Indiana Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://www.in.gov/attorneygeneral/consumer-protection-division/

Iowa Department of Justice

Consumer Protection Division

https://www.iowaattorneygeneral.gov/for-businesses/charitable-trust-registration

Office of the Kansas Attorney General

Civil Division

Licensing & Inspections

https://www.ag.ks.gov/divisions/civil/licensing-inspections/charitable-organization-registration

Office of the Kentucky Attorney General

Resources & Programs

Consumer Resources

https://www.ag.ks.gov/divisions/civil/licensing-inspections/charitable-organization-registration

Louisiana Department of Justice

Public Protection Division

https://www.ag.state.la.us/Division/PublicProtection

Louisiana Department of Justice

Gaming Division

https://www.ag.state.la.us/Division/Gaming

Maine Department of the Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://www.maine.gov/ag/consumer/charities/index.shtml

Maryland Office of the Secretary of State

Charitable Organizations Division

https://sos.maryland.gov/Charity/Pages/default.aspx

Office of the Maryland Attorney General

Consumer Protection

https://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/Pages/Nonprofits/default.aspx

Office of the Massachusetts Attorney General

Non-Profit Organizations/Public Charities Division

Michigan Department of the Attorney General

Consumer Protection

Charities

https://www.michigan.gov/consumerprotection/charities

Minnesota Office of the Attorney General

Charities Division

https://www.ag.state.mn.us/Charity/

Mississippi Office of the Secretary of State

Charities Division

https://www.sos.ms.gov/charities

Office of the Mississippi Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://attorneygenerallynnfitch.com/divisions/consumer-protection/

Office of the Missouri Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division, Charities Unit

https://ago.mo.gov/get-help/programs-services-from-a-z/charity/

Montana Department of Justice

Consumer Protection Division

https://dojmt.gov/office-of-consumer-protection/

Office of the Nebraska Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://protectthegoodlife.nebraska.gov/charity-home-page

Nevada Secretary of State

Licensing

https://www.nvsos.gov/sos/licensing/charitable-organizations

Office of the Nevada Attorney General

Bureau of Consumer Protection

https://ag.nv.gov/About/Consumer_Protection/Bureau_of_Consumer_Protection/

Office of the New Hampshire Attorney General

Charitable Trusts Unit

https://www.doj.nh.gov/bureaus/charitable-trusts

Office of the New Jersey Attorney General

Division of Consumer Affairs

https://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/charities/Pages/default.aspx

Office of the New Mexico Attorney General

Charitable Organizations

Office of the New York Attorney General

Charities Bureau

https://ag.ny.gov/resources/organizations/charities-nonprofits-fundraisers

North Carolina Secretary of State

Charities Division

https://www.sosnc.gov/divisions/charities

North Carolina Department of Justice

Consumer Protection Division

https://ncdoj.gov/protecting-consumers/charity/

North Dakota Secretary of State

Business Division

https://www.sos.nd.gov/business/nonprofit-services/charitable-organizations

Office of the North Dakota Attorney General

Consumer Protection

https://attorneygeneral.nd.gov/consumer-resources/

Ohio Office of the Attorney General

Charitable Law Section

https://charitable.ohioago.gov/

Office of the Oklahoma Secretary of State

Charitable Organizations

https://www.sos.ok.gov/charity/Default.aspx

Office of the Oklahoma Attorney General

Consumer Protection

https://oklahoma.gov/oag/about/divisions/cpu.html

Oregon Department of Justice

Charitable Activities Section

https://www.doj.state.or.us/charitable-activities/

Oregon Secretary of State

Nonprofit Services

https://sos.oregon.gov/business/Pages/nonprofit.aspx

Pennsylvania Department of State

Bureau of Corporations and Charitable Organizations

Charities Section

https://www.pa.gov/agencies/dos/programs/charities.html

Office of the Pennsylvania Attorney General

Charitable Trusts and Organizations Section

https://www.attorneygeneral.gov/protect-yourself/charitable-giving/

Rhode Island Department of Business Regulation

Securities Division

Rhode Island Department of the Attorney General

Civil Division, Charitable Trust Unit

Office of the South Carolina Secretary of State

Public Charities Division

https://sos.sc.gov/online-filings/charities-pfrs-and-raffles/charities

Office of the South Dakota Attorney General

Consumer Protection Division

https://consumer.sd.gov/fastfacts/charity.aspx

Office of the Tennessee Secretary of State

Division of Business and Charitable Organizations

Office of the Tennessee Attorney General

Public Interest Division

Office of the Texas Attorney General

Charitable Trusts Section

https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/divisions/charitable-trusts

Office of the Texas Secretary of State

Corporations Section

https://www.sos.state.tx.us/corp/nonprofitfaqs.shtml

Utah Department of Commerce

Division of Consumer Protection

https://www.dcp.utah.gov/for-businesses/charities/

Office of the Vermont Attorney General

Charities and Paid Fundraisers

https://ago.vermont.gov/attorney-generals-office-divisions-and-unit/charities-and-paid-fundraisers