Abstract

Donor-advised funds are a prominent and rapidly growing charitable giving vehicle. There is substantial information about the money flowing into them, but we know relatively little about what they ultimately support, and anecdotal news stories have raised questions about the role they may be playing in high-profile policy-oriented giving. With this in mind, we examine whether donor-advised funds are disproportionately supporting politically engaged charities. We find that donor-advised fund sponsors distribute grants to politically engaged charities – those engaged in lobbying or affiliated with organizations supporting political campaigns – at a rate nearly 1.7 times that of other giving sources. We further show that this feature is more pronounced with giving to fringe political groups, as donor-advised fund sponsors give to anti-government and hate groups at a rate 3.5 times that of other giving sources; in fact, we find that donor-advised funds account for more than one-quarter of all contributions received by these organizations. To focus on whether one motivation for such giving is the layer of opacity donor-advised funds create, we also examine private foundation grants to donor-advised funds. Private foundations are required to publicly disclose the identities of both their major donors and beneficiaries. Donor-advised funds, on the other hand, must only disclose grant recipients, and those disclosures are aggregate and not at the fund or donor level. For this reason, when a private foundation distributes to a donor-advised fund rather than directly to a beneficiary charity, donor privacy is a principal consequence. We find that donor-advised fund sponsors give disproportionately more to politically engaged charities when more of the sponsor’s revenue comes from private foundations.

1 Introduction

The rapid emergence of donor-advised funds, or DAFs, as the giving vehicle of choice for many donors represents perhaps the largest shift in the charitable giving landscape in the United States since the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1969 over 50 years ago. Estimates show that DAFs now take in more than one-quarter of individual giving, and DAF sponsors now comprise six of the 10 largest US charities in terms of annual contributions (Flannery 2024).

DAFs are segregated financial accounts that are managed by an accredited charity known as a sponsoring organization or DAF sponsor. A donor can claim an immediate tax deduction upon contributing money to a DAF account and then serve as an “advisor” to the account, recommending how the funds should be invested, when they should be granted out, and which operating charities should ultimately receive them. Legally, the DAF sponsor controls the account assets, but sponsors may – and almost always do – give substantial deference to the donors-as-advisors in making these choices (see, e.g., Reiser and Dean 2023).

Donor-advised funds play a charitable intermediary role similar to that of private foundations, but their reporting requirements regarding donors and grantees are very different. Private foundations must publicly report both major donors and grant recipients in their annual Form 990-PF disclosures. As public charities, on the other hand, DAF sponsors are only required to disclose grant recipients in aggregate in their Form 990 Schedule I, and are not required to disclose either the grantees of or the donors to individual funds.

This paper considers not only whether donors in general are disproportionately making gifts to politically engaged charities through DAFs, but also whether private foundations in particular are disproportionately directing politically engaged grants through DAFs – behavior that may be encouraged by the opacity DAFs offer.

Our analysis identifies politically engaged charities as those either directly engaged in lobbying efforts or affiliated with organizations engaged in political campaigns, regardless of partisan ideology. We begin with a sample of all public charities in the US that filed their Form 990 annual information returns electronically for all tax years since the imposition of electronic filing requirements. This results in a data set that includes returns filed from calendar years 2020–2022. We split the data set into two samples: DAF sponsors (those for which donor-advised funds represent 10 % or more of total assets) and operating charities (all others).

We then develop a means of classifying the operating charities based on their type of political engagement, if any. For this analysis, political engagement categorization is tied to IRS classification of political activities and can take the form of (i) lobbying, i.e., spending on efforts for or against legislation, and/or (ii) politicking, i.e., engaging in activities in support of or against electoral campaigns. Because direct politicking by 501(c)(3) charities is prohibited, we include engagement through affiliated 501(c)(4) or 527 nonprofits which themselves engage in direct politicking in (ii). Such a circumstance reflects the potential for indirect support of political activity.

Using these political engagement classifications, we examine the overall funding rates of each operating charity category and rates of funding from the sample of DAF sponsors. We find that DAF sponsors fund politically engaged charities at a rate 1.7 times that of other funding sources, with the donors using large national DAF sponsors being particularly generous in their giving to politically engaged organizations. We also find that the more a sponsor relies on DAFs for its revenue, the greater its rate of politically engaged giving, suggesting it is not merely the intermediary role of sponsors but rather DAFs in particular that account for the magnified giving rates.

We also examine whether the connection between DAFs and politically engaged giving applies to the case of extreme fringe groups. We find that DAFs fund organizations deemed hate or anti-government groups by the Southern Poverty Law Center at a rate 3.5 times that of other funding sources; in fact, DAF grants account for one-quarter of all contributions received by these organizations. We also find that – as with conventional politically engaged giving – sponsors give more grants to fringe groups when they rely more on DAFs for their own funding.

Finally, we measure whether donors funding private foundations in particular are using DAFs to facilitate grants to politically engaged charities. Private foundations are required to publicly disclose both major donors and grant recipients in Form 990-PF filings, while DAF sponsors do not have to publicly disclose their donors and only have to disclose grantees at the aggregate level. Sending a grant through a DAF would, therefore, be a convenient way for a private foundation donor to sidestep disclosure requirements, since the foundation needs only to list the DAF sponsor as the recipient, not the ultimate beneficiary. Consistent with the hypothesis that this opacity can be a driver of politically engaged giving through DAFs, we find that DAF sponsors that receive more of their funds from private foundations also distribute more of their grants to politically engaged charities.

In other words, when DAF giving obscures donor identities that would otherwise be publicly reported, such giving is also more concentrated in politically engaged charities. This suggests that foundation donors may indeed be circumventing public disclosure of their political giving by filtering funds through DAFs.

2 Background and Related Literature

2.1 The Donor-Advised Funds Boom

The first donor-advised funds were established in the 1930s and have been a staple fundraising instrument for community foundations for decades. Their recent surge began with the birth of national sponsors like Fidelity Charitable and Vanguard Charitable in the 1990s (Berman 2015). Since that time, donor-advised funds have seen astronomical growth, with double-digit annual average growth rates over the past decade, and now take in over one-quarter of giving by individuals in the US (e.g., Flannery et al. 2023).

Donor-advised funds provide substantial advantages over other means of giving. Like private foundations, DAFs give donors a great deal of control over charitable funds. As instruments of public charities, they offer greater tax advantages than private foundations, and save the donor much of the cost and administrative burden of operating a charitable fund (see, e.g., Hackney and Mittendorf 2017).

The recent rapid growth of DAFs has put them under considerable scrutiny, much of which is focused on their lack of a distribution requirement (Andreoni 2018; Andreoni and Madoff 2023; Heist and Vance-McMullen 2019). Other features have raised eyebrows as well: distributions to DAFs can count towards meeting annual private foundation payout requirements (which generally amount to 5 % of assets annually), distributions from DAFs can enable organizations to satisfy the public support test and thereby avoid classification as private foundations, and reporting requirements established at the sponsor level obscure account-level behavior (Brunson 2020; Colinvaux 2017).

Though operating charities’ disclosures about individual donors (in Form 990 Schedule B) are typically redacted from the public, the information is still available for regulators to examine. And private foundations must publicly disclose their major donors as well as their grantees. With DAFs, on the other hand, information about grants from specific donors to specific charities is obscured from the public, regulators, and sometimes even the charity recipients themselves. This means that if donors want to shield their identities when giving to politically charged, vulnerable, or controversial charity recipients, filtering those funds through DAFs is an effective way to do so, particularly when the alternative is to give through a private foundation (Gibbons 2021).

2.2 The Confluence of Politics and Charity

Political engagement by charities is a broad concept – one that could conceivably encompass most activities of charitable organizations (Aprill et al. 2023). In fact, nonprofits have a rich history of leading civic engagement, promoting democratic principles, and advocating for groups and causes (e.g., MacIndoe et al. 2025; Mosely et al. 2023; Pekkanen et al. 2014; Suarez 2020). Tax law has isolated two specific types of political involvement – politicking and lobbying – as political activities subject to limitation. For our purposes, politicking, which can also be called electioneering, is advocacy for or against specific political candidates, while lobbying is advocacy for or against specific legislation.

Often dubbed the “Johnson Amendment,” the provision of the US tax code enacted in 1954 that prohibits support of or opposition to political candidates effectively bans partisan politicking by 501(c)(3) organizations (Colinvaux 2014). Yet some have flouted these rules, sometimes inadvertently and other times as a provocation (Mayer 2018). This, in combination with notoriously low IRS audit rates, means that such prohibited activity may occur at organizations receiving DAF support.[1]

Even for those that do not violate the prohibition on direct partisan activities, having affiliated organizations that engage in direct politicking represents a key source of indirect political engagement by charities. It is notoriously difficult to prevent indirect subsidies of politicking by 501(c)(3) organizations, since those with social welfare 501(c)(4) affiliates often share brand names, volunteers, and resources, and may even provide grants to these affiliates (Galle 2020). For example, the 501(c)(3) foundation arms of the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Rifle Association have both given financial support to their 501(c)(4) affiliates. Though 501(c)(3) organizations are required to ensure that grants to non-501(c)(3) affiliates are used for nonpolitical charitable purposes, this funding nevertheless arguably frees up resources which makes it easier for those affiliates to perform their political work (Colinvaux 2019). With unlimited lobbying ability and loose restrictions on direct political activity, 501(c)(4) organizations have much more flexibility in political involvement than their 501(c)(3) counterparts.

The fact that a 501(c)(3) organization can have a 501(c)(4) affiliate that engages in expanded political activities (and therefore is not overly burdened by a restriction on its own direct activities) was even one justification for the Supreme Court opting to uphold limits on direct political activities by 501(c)(3) organizations (Aprill 2011). While not all 501(c)(4) affiliates are engaged in direct politicking, evidence suggests that it plays a substantial role for around 15 % of them (Post and Boris 2023; Post et al. 2023). Those 501(c)(3) organizations with 501(c)(4) affiliates tend to be larger organizations, and 501(c)(4) organizations that are involved in electoral politics also tend to take in more revenue than others (Koulish 2016). When a 501(c)(3) charity has an affiliated 527 organization – a tax-exempt organization established for expressly political purposes – the connection to politicking is even more explicit.

Even when 501(c)(3) charities are not part of larger networks, they often themselves engage in lobbying to support or oppose legislation. Tax law permits this, provided the charity’s lobbying is “no more than an insubstantial part of its activities.” They also can opt for a 501(h) election that provides specified dollar limits on lobbying – an option rarely taken, as evidence suggests 501(h) elections are taken by around 2 % of all 501(c)(3) organizations (Grasse et al. 2021).

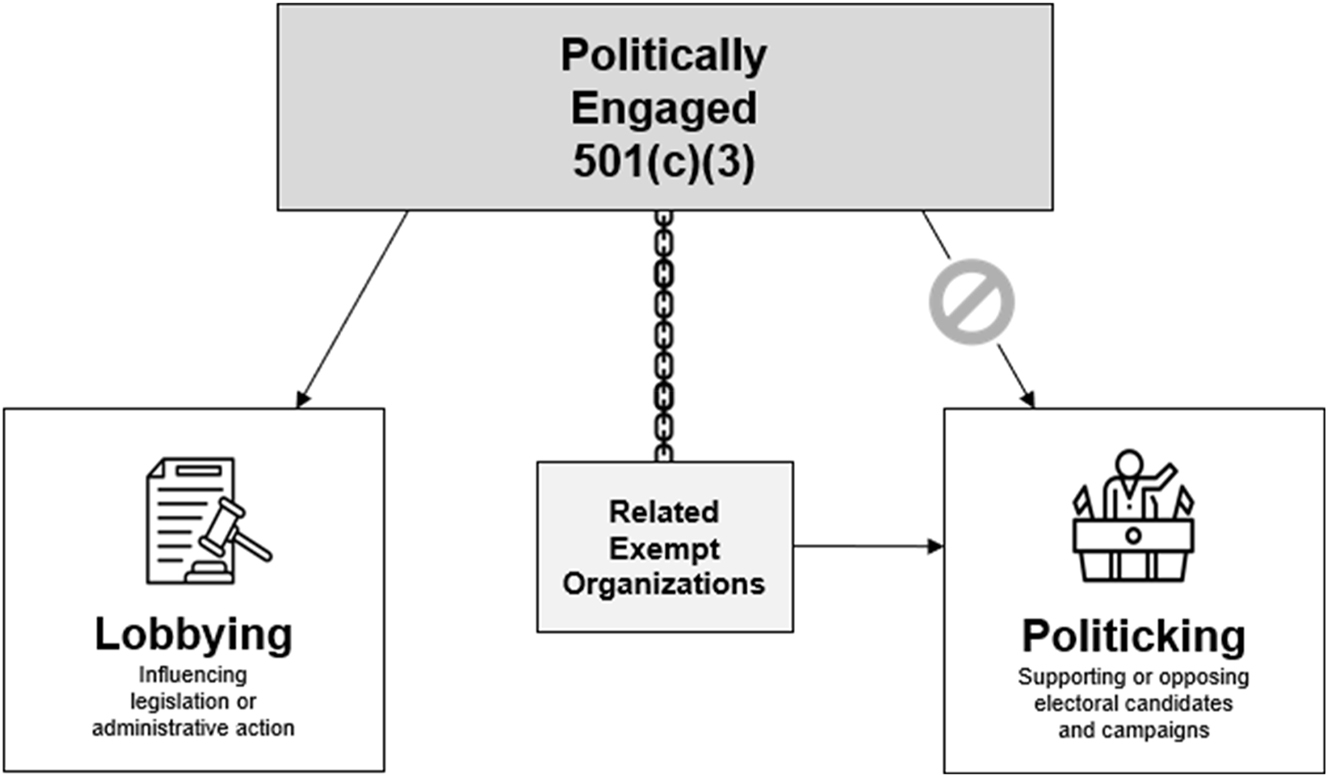

Figure 1 summarizes the types of charitable political engagement we consider in our analysis.

Types of 501(c)(3) charity political engagement. Note: All clip art used in this diagram is from The Noun Project and was designed for public use by the following artists: chain links by kareemovic2000; legislation icon by Icon 5; politicking icon by Becris; banned activity icon by Fernanddo Santtander.

In each of the types of engagement above, charitable dollars directly or indirectly support political activities to varying degrees. When they do, donor disclosure rules serve as a check on egregious or prohibited support. If the support comes from a private foundation, for example, the foundation’s annual 990-PF disclosures provide clear documentation back to the donor (Brody 2012). And when donors give directly, the recipient charity reports its major benefactors to the IRS on its annual 990 Schedule B disclosures (Thompson 2022).

Donor-advised funds can obscure this window of transparency. If a donor gives to a politically engaged charity by funneling grants through a DAF, as opposed to a private foundation, the IRS and the public have no way of knowing who they are. For instance, when Acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker was asked in a congressional hearing who the donors were that supported his previous nonprofit employer, he said he did not know since the funds came from a DAF (Colinvaux and Madoff 2019). And while media reports of large grants from donor-advised funds to hate groups have naturally raised public concern, many of the donors behind these grants remain undisclosed (Kotch 2023).

Politically engaged charities often play a crucial role in advocacy, public engagement, and legislative reform. Yet, given the variety of ways political engagement arises, the confluence of charitable political engagement and the growth of DAFs has implications for regulators, charities, and ordinary citizens alike. Whether the connection between DAFs and politically engaged giving is merely theoretical (and examples of it are merely cherry-picked anecdotes) or if it is instead a systemic phenomenon is largely unknown – a gap we seek to fill in this study.

3 The Prevalence of Donor-Advised Fund Giving to Politically Engaged Charities

3.1 Classifying Political Engagement of Charities

To understand the extent to which donor-advised funds facilitate giving to politically engaged charities, we begin with a classification of charities according to the two key dimensions governing charitable political engagement – politicking and lobbying.

To identify politicking charities, we first include 501(c)(3) charities that are affiliated with nonprofit organizations that engage in overtly political activity. This is an indirect, allowed, and common way that a charity can hold ties to politicking. Specifically, a charity may have a 527 political organization affiliate, or it may have an affiliated 501(c)(4) social welfare group that is engaged in political activities, as reflected in any of the following disclosures by the 501(c)(4) affiliate: incurring section 527 exempt function expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-C, Line 3), filing an 1120-POL (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-C, Line 4), engaging in activities in support of or opposed to a political candidate (Form 990, Part IV, Line 3), or making campaign activity expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-A, Line 2). For each year under analysis, we label any charity that reports an affiliated tax-exempt entity on Form 990, Schedule R which satisfies any of the above criteria as a politicking charity. While these affiliations do not constitute direct politicking, each reflects a circumstance where the charity can be viewed as potentially subsidizing or at least indirectly supporting such political activity.

Though direct politicking is prohibited by charitable organizations, we also include any charity in a given year that discloses having engaged in activities in support of or opposed to a political candidate (Schedule 990, Part IV, Line 3), political campaign expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-A, Line 2), or payments of section 4955 excise taxes (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-B, Line 1 or 2) in the group of politicking charities.

To identify lobbying charities, we include 501(c)(3) organizations for which lobbying is a nontrivial part of their operations. 501(c)(3) charities are permitted to do a limited amount of lobbying, provided that it is in support of or in opposition to specific legislation, rather than political candidates or parties. For each year under analysis, we label any charity for which lobbying expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part II-A, Line 1c, column (a) or Form 990, Schedule C, Part II-B, line 1j, column(b)) represent more than 1 % of their overall budget (Form 990, Part I, Line 18) as lobbying charities.[2]

Given the substantial difference between politicking and lobbying, we will examine giving rates to them separately as well as in total.[3]

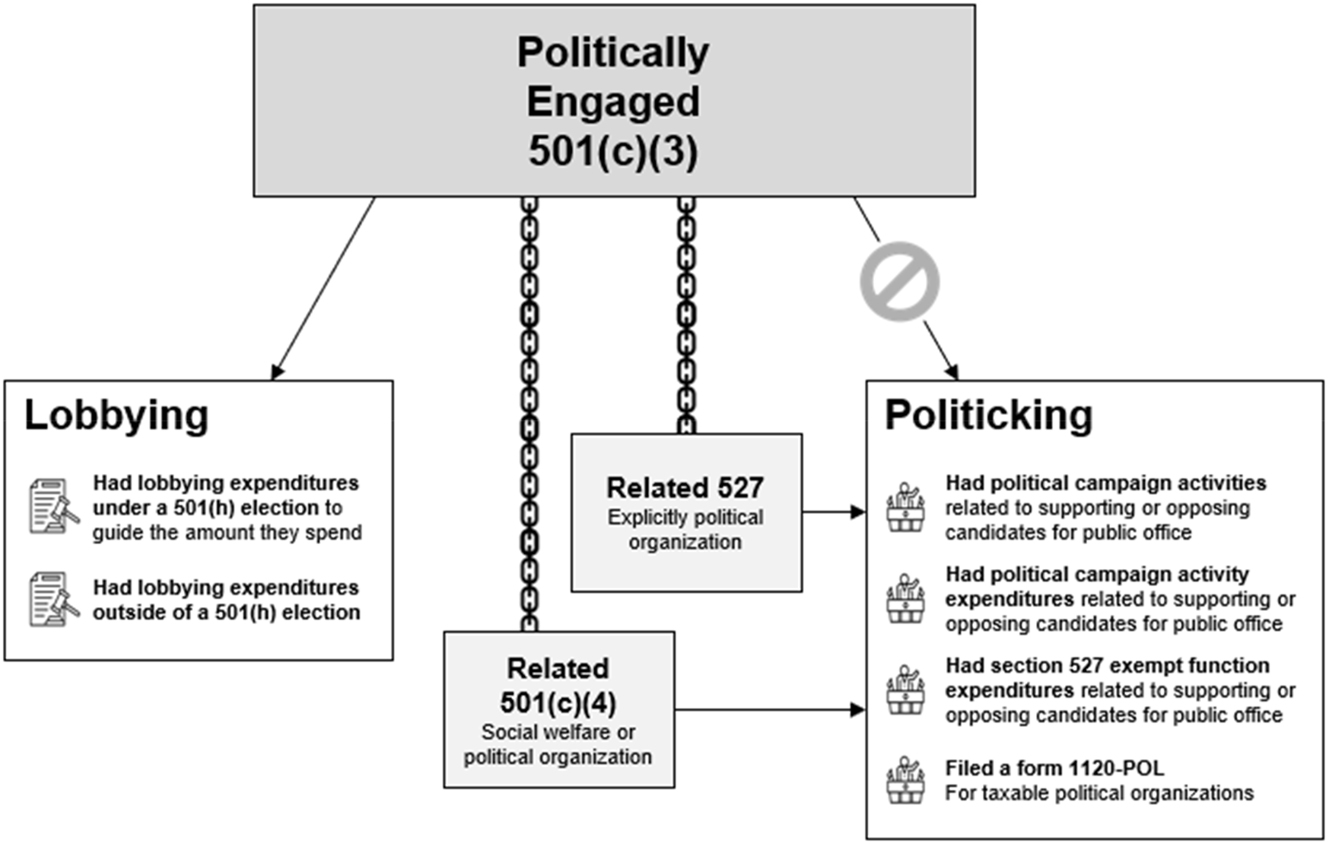

Appendix A provides an example of the classification methodology for a specific charity, Appendix B provides a full description of our political classification methodology, and Figure 2 below graphically summarizes the categorization criteria.

Categorizing 501(c)(3) charity political engagement. Note: All clip art used in this diagram is from The Noun Project and was designed for public use by the following artists: chain links by kareemovic2000; legislation icon by Icon 5; politicking icon by Becris; banned activity icon by Fernanddo Santtander.

3.2 Sample Description

To examine funds flowing from DAFs to operating charities, we begin with a public data set of all public charity Form 990 information returns filed electronically with the IRS for all tax years since the imposition of an electronic filing requirement (covering calendar years 2020–2022). For each year under analysis, we separate organizations into DAF sponsors and operating charities, with DAF sponsors being any organizations for which donor-advised fund assets (Form 990, Schedule D, Part I, Line 4 (a)) were 10 % or more of total assets (Form 990, Part I, Line 20) that year.

We then classify each operating charity in each year according to whether it is a politicking charity, lobbying charity, neither, or both, following the identification process explained in Appendix B. This yields 721,181 charity-year observations, of which 8,716 are politically engaged. Of the politically engaged observations, 2,454 are politicking charities and 6,630 are lobbying charities).[4]

Table 1 presents the breakdown of operating charities by category and year, along with summary measures of size. These measures include the mean and standard deviation of both Assets it and Contrib it split by year and political classification, where Assets it represents end-of-year assets (Form 990, Part I, line 20) and Contrib it represents annual (non-government) contributions (Form 990, Part VIII, line 1h less line 1e), each adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels (Appendix C provides a full description of all variable definitions used in the analysis).

Descriptive statistics of operating charities sample.

| Pooled | Full sample (N = 721,181) | Politically engaged (N = 8,716) | Politicking (N = 2,454) | Lobbying (N = 6,630) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 24,041 | 447,691 | 35,068 | 475,119 | 80,751 | 852,518 | 17,928 | 166,898 |

| Contrib it | 1,535 | 22,211 | 4,584 | 31,396 | 7,217 | 38,989 | 4,132 | 30,417 |

| 2020 | Full sample (N = 229,713) | Politically engaged (N = 2,767) | Politicking (N = 772) | Lobbying (N = 2,122) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 24,289 | 429,785 | 32,712 | 522,421 | 73,663 | 934,416 | 18,141 | 199,743 |

| Contrib it | 1,522 | 21,440 | 4,341 | 30,947 | 7,540 | 41,541 | 3,878 | 30,171 |

| 2021 | Full sample (N = 243,076) | Politically engaged (N = 2,960) | Politicking (N = 806) | Lobbying (N = 2,273) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 25,501 | 484,759 | 33,045 | 415,922 | 77,587 | 779,742 | 16,949 | 97,789 |

| Contrib it | 1,583 | 23,727 | 4,892 | 34,249 | 7,432 | 40,847 | 4,427 | 33,143 |

| 2022 | Full sample (N = 248,392) | Politically engaged (N = 2,989) | Politicking (N = 876) | Lobbying (N = 2,235) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 22,382 | 425,594 | 39,254 | 484,166 | 89,910 | 841,810 | 18,723 | 187,212 |

| Contrib it | 1,500 | 21,362 | 4,503 | 28,751 | 6,735 | 34,723 | 4,072 | 27,637 |

-

This table presents descriptive statistics for the size and number of operating charities not classified as DAF sponsors. All numbers are presented in thousands of 2022 US dollars. Rows provide year splits and columns provide political engagement category splits.

The summary statistics show high variation in charities’ sizes, as has been commonly observed in the literature, and this feature persists across years and political classifications. In each subsample, a small number of very large organizations skews the averages, causing significant variation in asset and contribution levels. To control for the over-influence of outliers, therefore, our regression analyses primarily use scaled data and winsorized continuous variables (although we find similar qualitative results without winsorization). The data also shows that politically engaged organizations are larger than nonpolitical ones. In fact, the average sizes of politicking charities – whether in terms of contributions or assets – are generally at least three times that of the full sample average.

To examine grants from DAF sponsors, we compile identifiable grants for each sponsor-year, where identifiable grants include all grants listed on Form 990 Schedule I for which the recipient EIN is in the operating charities sample. We begin with all DAF sponsor observations, consisting of 4,198 organization-years. For each year under analysis, we remove any DAF sponsor observations for which there were no identifiable grants, excluding 1,568 organization-years.[5] From this group of 2,630 organization-years with identifiable grants, we also remove any observations for which the reported grants paid from DAF accounts (Form 990, Schedule D, Part I, Line 3) are less than zero or exceed total grants (Form 990, Part I, Line 13), or for which contributions to DAF accounts (Form 990, Schedule D, Part I, Line 2) are less than zero or exceed total reported contributions (Form 990, Part VIII, Line 1h less Line 1e). This results in a DAF sponsor sample representing 2,475 organization-years.[6] On an annual basis, this number of DAF sponsors is consistent with those identified in extant research on overall DAF resource flows (Flannery and Mittendorf 2025a; Heist and Vance-McMullen 2019).

To examine differences in behavior across DAF sponsors, we then split DAF sponsors based on their type, using the commonly-accepted three-type classification: community foundations, national sponsors, and single-issue sponsors. We categorize any organization included on a list of national sponsors maintained by the Institute for Policy Studies – presented in Appendix D – as a national sponsor. To identify community foundations, we obtain the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE) codes for each sponsor and categorize any sponsor with an NTEE code starting with T31 as a community foundation. Any other sponsors with “foundation” or “trust” along with a U.S. geographical reference in their name (without reference to religion, fraternal organizations, universities, specific populations of people, or any other single-issue group) we also classified as community foundations. The remaining sponsors are classified as single-issue sponsors (this process mirrors that in Flannery and Mittendorf (2025b)).

Table 2 presents the breakdown of the DAF sponsor grants sample by type and year, along with summary measures of size. As with Table 1, we present both Assets it and Contrib it , along with the total identifiable grants to operating charities, adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels, denoted IDGrants it .

Descriptive statistics of DAF sponsor grants sample.

| Pooled | Full sample (N = 2,475) | Community Fndn (N = 1,512) | National (N = 115) | Single issue (N = 848) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 338,346 | 2,156,943 | 225,777 | 718,165 | 3,488,556 | 9,059,059 | 111,849 | 449,639 |

| Contrib it | 88,191 | 716,787 | 33,977 | 169,632 | 1,231,830 | 3,028,598 | 29,763 | 169,102 |

| IDGrants it | 37,905 | 308,136 | 18,377 | 99,982 | 488,247 | 1,293,455 | 11,653 | 73,594 |

| 2020 | Full sample (N = 811) | Community Fndn (N = 499) | National (N = 37) | Single issue (N = 275) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 296,853 | 1,785,444 | 220,751 | 679,706 | 2,833,437 | 7,582,068 | 93,659 | 331,870 |

| Contrib it | 71,826 | 542,146 | 31,856 | 129,798 | 956,429 | 2,325,403 | 25,333 | 130,579 |

| IDGrants it | 32,974 | 243,780 | 17,459 | 85,329 | 401,079 | 1,027,958 | 11,601 | 66,472 |

| 2021 | Full sample (N = 830) | Community Fndn (N = 502) | National (N = 41) | Single issue (N = 287) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 389,063 | 2,430,057 | 253,667 | 841,871 | 3,868,643 | 9,920,125 | 128,806 | 525,256 |

| Contrib it | 102,557 | 779,930 | 40,029 | 222,404 | 1,351,763 | 3,161,094 | 33,467 | 208,876 |

| IDGrants it | 41,218 | 355,698 | 19,001 | 110,797 | 524,647 | 1,477,103 | 11,016 | 69,239 |

| 2022 | Full Sample (N = 834) | Community Fndn (N = 511) | National (N = 37) | Single Issue (N = 286) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (in 000s) | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev |

| Assets it | 328,220 | 2,199,234 | 203,286 | 615,954 | 3,722,498 | 9,611,689 | 112,321 | 466,362 |

| Contrib it | 89,808 | 796,421 | 30,102 | 141,970 | 1,374,331 | 3,524,267 | 30,307 | 157,401 |

| IDGrantsit | 39,403 | 313,458 | 18,659 | 102,207 | 535,081 | 1,343,647 | 12,340 | 83,883 |

-

This table presents descriptive statistics for the size and number of charities classified as DAF sponsors. All numbers are presented in thousands of 2022 US dollars. Rows provide year splits and columns provide sponsor type splits.

As in extant research, DAF sponsors exhibit great variation in size, both within and across sponsor types. Though smallest in number, national DAF sponsors have greater assets, contributions, and grants, on average, than other types of sponsors. These phenomena persist in both pooled and annual data.

Also notable is the difference in scale between incoming contributions and outgoing identifiable grants. In aggregate, reported grants paid to identifiable 501(c)(3) organizations are 43 % of total contributions received by DAF sponsors. The primary reason for this gap is simply that grants overall – not just identifiable grants – are markedly lower than total contributions; for all sponsors as a group, aggregate grants are 70 % of aggregate contributions.[7]

3.3 Donor-Advised Fund Grants to Politically Engaged Charities

To examine the extent to which DAF sponsors fund politically engaged charities, and to compare that to funding from other sources, we begin with an overall giving rate comparison. Even though politically engaged charities make up only 1.2 % of all operating charities, DAF sponsors give grants to them at an aggregate rate of 5.9 % – a rate calculated by dividing Schedule I grants to organizations identified as politically engaged in the operating charities sample by total identifiable Schedule I grants. In contrast, total non-DAF contributions received by politically engaged operating charities divided by total non-DAF contributions received by all operating charities is 3.6 %. In other words, in our sample, DAFs give to politically engaged charities at a rate 1.7 times that of other funding sources.

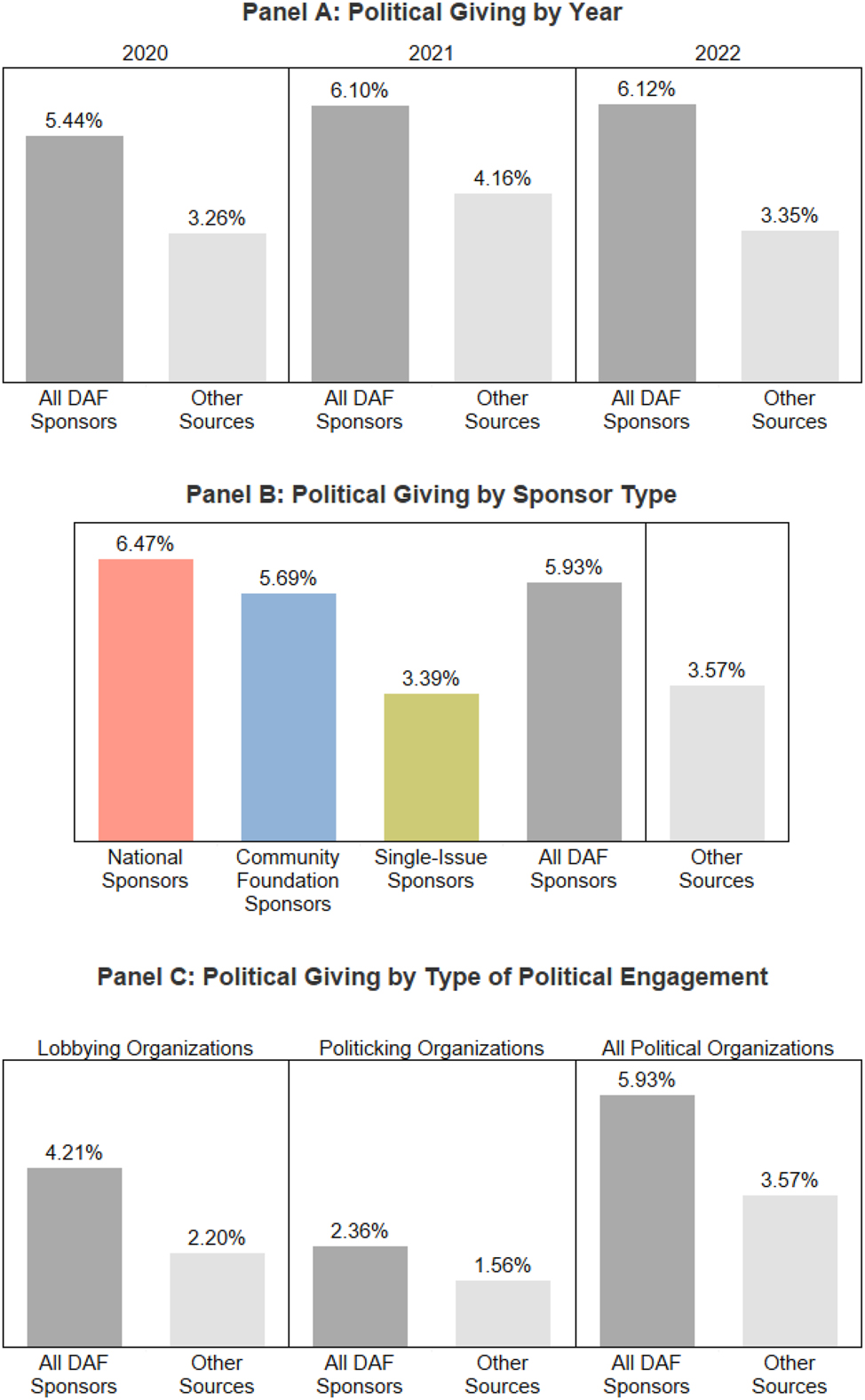

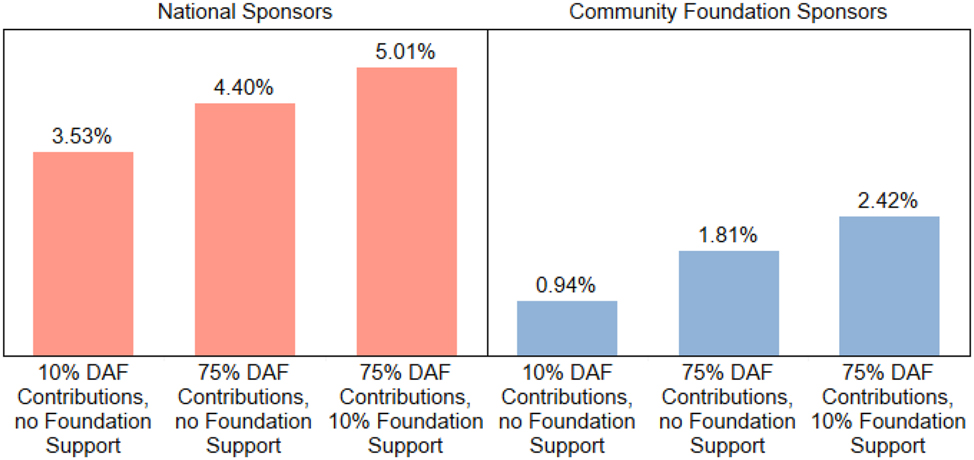

Figure 3 presents the giving rates of DAF sponsors to politically engaged charities, split by year (Panel A), by sponsor type (Panel B) and by political engagement category (Panel C).

Aggregate rates of giving to politically engaged charities.

As shown in Figure 3, the higher rate of politically engaged giving among DAF sponsors relative to other giving channels persists across both time and type of political engagement. It is highest for national and community foundation sponsors, for which political giving rates are 1.8 times and 1.6 times the benchmark rate, respectively.

To further examine the extent to which greater politically engaged giving is driven not only by sponsor type but also by a sponsor’s reliance on DAFs, we next examine predictors of politically engaged giving rates based on variation in sponsor type, DAF reliance, and time, estimating the following regression:

To test different forms of politically engaged giving, we consider three variations on the dependent giving rate variable (PoliticalGivingRate it ): percent of all identifiable grants made to politically engaged charities of any type (PctPolitical it ), percent of identifiable grants made to politicking charities (PctPoliticking it ), and percent of identifiable grants made to lobbying charities (PctLobbying it ). To capture reliance on DAFs (DAFReliance it ), we use two different measures: the percent of the sponsor’s total grants that are paid from DAF accounts (PctGrantsDAF it ) and the percent of the sponsor’s total contributions that are received in DAF accounts (PctContribDAF it ). Sponsor type is reflected in (1) through Nat i and SI i , which are indicator variables equal to 1 if the sponsor is identified as a national sponsor or single-issue sponsor, respectively. In each regression, we winsorize the dependent and continuous independent variables at the 1 %-level and use standard errors clustered at the EIN level.[8]

Table 3 presents the results of the regressions examining sponsor characteristics and political giving rates.

DAF sponsor giving to politically engaged charities.

| Panel A: Overall political giving | ||

|---|---|---|

| DV = PctPolitical it | DV = PctPolitical it | |

| Intercept | 0.0116*** | 0.0118*** |

| (0.0022) | (0.0022) | |

| NAT i | 0.0249*** | 0.0248*** |

| (0.0068) | (0.0069) | |

| SI i | 0.0076** | 0.0082*** |

| (0.0030) | (0.0030) | |

| PctGrantsDAF it | 0.0111*** | |

| (0.0042) | ||

| PctContribDAF it | 0.0107*** | |

| (0.0042) | ||

| Year Fixed Effects? | Y | Y |

|

|

||

| N | 2,475 | 2,475 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.026 | 0.026 |

| Panel B: Giving to political-engagement categories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = PctPoliticking it | DV = PctPoliticking it | DV = PctLobbying it | DV = PctLobbying it | |

| Intercept | 0.0049*** | 0.0050*** | 0.0089*** | 0.0089*** |

| (0.0009) | (0.0009) | (0.0018) | (0.0019) | |

| NAT i | 0.0135*** | 0.0135*** | 0.0144*** | 0.0141*** |

| (0.0032) | (0.0032) | (0.0047) | (0.0048) | |

| SI i | 0.0015 | 0.0017 | 0.0054** | 0.0058** |

| (0.0012) | (0.0011) | (0.0025) | (0.0024) | |

| PctGrantsDAF it | 0.0034** | 0.0081** | ||

| (0.0017) | (0.0034) | |||

| PctContribDAF it | 0.0032** | 0.0082** | ||

| (0.0016) | (0.0034) | |||

| Year Fixed Effects? | Y | Y | Y | Y |

|

|

||||

| N | 2,475 | 2,475 | 2,475 | 2,475 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

-

These tables present regression results estimating the percent of a DAF sponsor’s annual grants that are made to politically engaged charities (PctPolitical it , PctPoliticking it , or PctLobbying it ) to measure the connection between grants to politically engaged charities and sponsor type (NAT i and SI i ) and degree of reliance on DAFs (PctGrantsDAF it or PctContribDAF it ). Standard errors clustered at EIN are denoted in parentheses below the coefficient estimates. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1-, 5-, and 10-% levels, respectively, using two-tailed tests.

These regressions have two notable results. First, national sponsors consistently make grants to politically engaged charities at higher rates than do community foundations. This feature is statistically significant (p < 0.01) and robust across types of political engagement, be it overall (Panel A) or within our two subsets of politically engaged giving (Panel B).

Second, the more a sponsoring organization relies on DAFs for its funding, the more of its grants go to politically engaged recipients. This feature is also statistically significant (p < 0.01) and robust across measures of DAF reliance. In addition, for both of our measures of reliance, greater sponsor reliance on DAFs is associated not only with greater politically engaged giving overall, but also with both greater politicking support and lobbying support separately (p < 0.05).

Taken together, these results suggest that not only do donors disproportionately use DAFs for politically engaged giving of all kinds, but also that the more dependent a sponsor is on its DAF donors, the more apt it is to distribute such politically engaged gifts. And although lobbying and politicking capture very different types of political engagement – lobbying represents direct advocacy by a charity, while politicking represents a more indirect connection to partisan activities – DAFs disproportionately fund both types.

3.4 The Limits to Sponsor Deference: A Look at Fringe Groups

To examine the outer bounds of politically engaged giving by DAFs, we next look at the most extreme manifestation of charitable political engagement: groups advocating for hate or government overthrow. Besides being particularly controversial, grants to these groups may capture circumstances where donors would especially value keeping their names off of Schedule B filings received by the IRS. On the other hand, they also capture situations where one may reasonably expect sponsors to exercise their legal control over the distribution of DAF assets to avoid being implicit partners in extremist support. If donors are moving more money to these fringe groups through DAFs than through other funding methods, it speaks not only to whether donors are using DAFs for extreme forms of political support, but also whether DAF sponsors are placing guardrails on the giving process or instead passively acceding to donor demands.

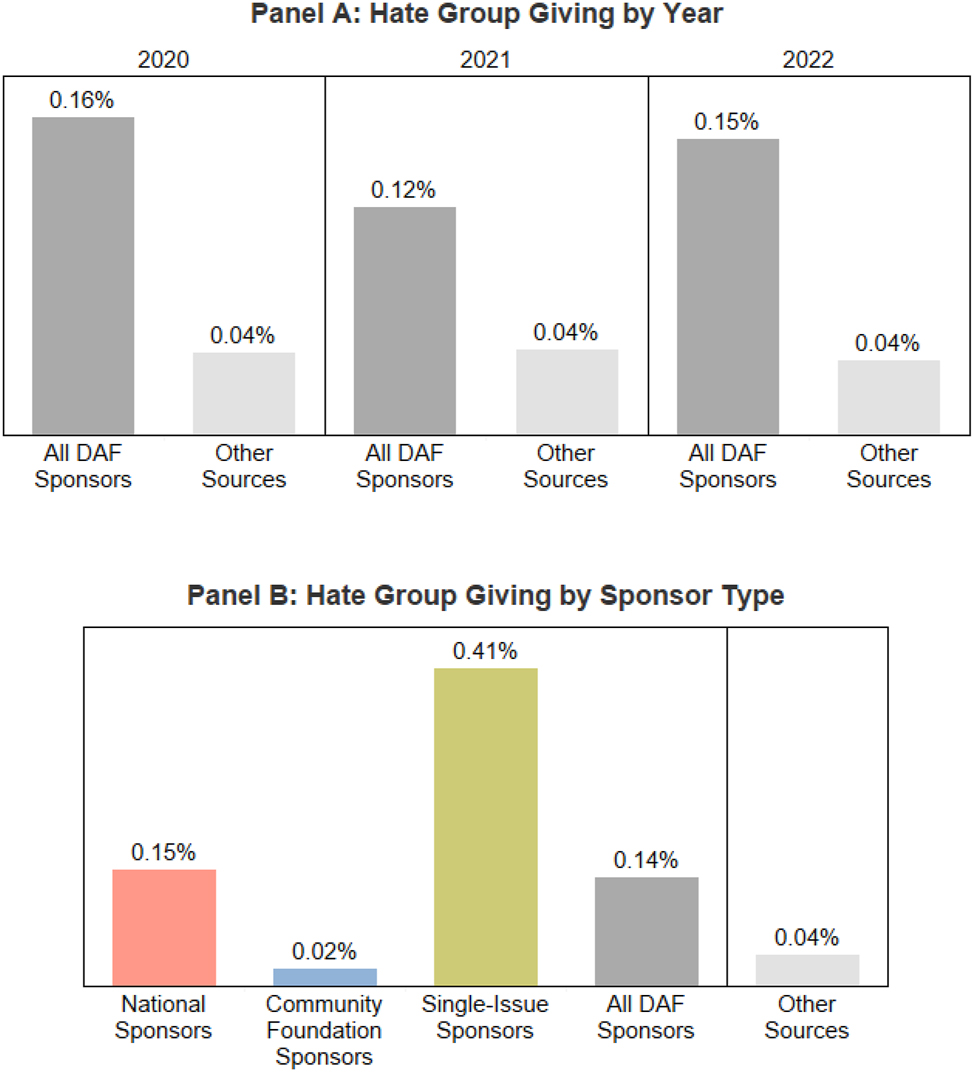

To test these potentially competing factors, we revisit our analysis of giving patterns, this time focusing on giving to charities included in the Southern Poverty Law Center’s list of anti-government and hate groups (we will collectively call these organizations “hate groups”).[9] To determine the extent to which DAFs facilitate gifts to these organizations, we first calculate aggregate hate-group giving rates for DAF donors and other funding sources. Figure 4 presents these giving rates by year (Panel A) and by sponsor type (Panel B).

Aggregate rates of giving to hate groups.

Though the overall giving rates to hate groups are small – reflecting the small portion of operating charities that these fringe groups represent – DAFs consistently make grants to them at higher rates.[10] Notably, DAFs make grants to hate groups at a level 3.5 times that of other funding sources, a finding that persists across time. In fact, grants from DAF sponsors represent more than one-quarter of all public support received by hate groups in the sample, a finding that also persists across time.

To test whether differences in hate group granting rates reflect outliers and random variation rather than fundamental sponsor characteristics, we next revisit our primary approach of examining political giving rates, but instead calculate it for hate group giving rates. In particular, we consider the following regression model:

In (2), PctHate it reflects the percentage of all identifiable grants by DAF sponsor i in year t that were made to hate groups. We again estimate this regression for different measures of DAF reliance, the results of which are presented in Table 4.

Percentage of DAF sponsor giving to hate or anti-government groups.

| DV = PctHate it | DV = PctHate it | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.0001** | −0.0001** |

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |

| NAT i | 0.0004* | 0.0004 |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | |

| SI i | 0.0000 | 0.0001 |

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |

| PctGrantsDAF it | 0.0003*** | |

| (0.0001) | ||

| PctContribDAF it | 0.0003*** | |

| (0.0001) | ||

| Year Fixed Effects? | Y | Y |

|

|

||

| N | 2,475 | 2,475 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.034 | 0.035 |

-

This table presents regression results estimating the percent of a DAF sponsor’s annual grants that are made to hate or anti-government groups (PctHate it ) to measure the connection between grants to such groups and sponsor type (NAT i and SI i ) and degree of reliance on DAFs (PctGrantsDAF it or PctContribDAF it ). Standard errors clustered at EIN are denoted in parentheses below the coefficient estimates. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1-, 5-, and 10-% levels, respectively, using two-tailed tests.

As the regression results reveal, the connection between DAF reliance and hate group giving is robust to each measure of DAF reliance, even after controlling for sponsor type and time. This is evidence that DAFs not only disproportionately facilitate politically engaged giving, but also disproportionately facilitate the most extreme forms of politically engaged giving.

Unlike with overall politically engaged giving, however, no sponsor type gives a discernably greater proportion of its grant dollars to hate groups than any other type. That is, though national sponsors do facilitate more politically engaged giving in general, there is no statistically significant connection between hate group giving and national sponsors as compared to any other sponsor type. Additional research may be able to identify other characteristics of sponsors that predict greater support of extremism, and which may warrant additional scrutiny – including examination of the extent to which donor anonymity is a factor in such giving.

3.5 When Opacity is a Primary Factor: A Look at Private Foundation Funding

Though minimal donor disclosure is certainly a feature of DAFs, it is not straightforward to isolate this feature as a determinant of politically engaged giving through them. After all, if a donor’s goal is to avoid identification, it is hard for a researcher to identify that donor, let alone their motivation, and direct giving to public charities also provides a shield from public scrutiny. That said, there is one class of donors for which giving through DAFs would clearly not be as attractive without the promise of obscuring donor identities: private foundation donors.

Since DAFs can essentially serve as de facto private foundations themselves, these two giving vehicles are often seen as substitutes. Donors seeking a charitable intermediary (to retain control over funds, to front-load tax benefits for gifts, etc.) can use either a private foundation or a DAF to achieve those goals (see, e.g., Froehlich 2023).[11] Yet it has been empirically observed that private foundations themselves also make grants to DAF accounts (Flannery 2023).

In other words, donors who establish private foundations to serve as an intermediary for their giving can, and often do, direct their foundation to distribute to another intermediary, a DAF, before directing the funds to the ultimate charity recipient. One explanation for these grants to DAFs is that they are a backdoor way to meet foundation payout requirements – a feature viewed as ripe for regulation for which fixes have been included in the Biden administration’s budget proposals as well as the 2021 ACE Act charitable reform bill (Mann and Calvert 2021). A second, and less discussed, explanation is that by funneling grants to operating charities through DAFs, foundations can evade some disclosure requirements: the 990-PF returns filed by foundations only need to list the DAF sponsor, not the ultimate charity recipient, as the grantee (Gibbons 2021).

This second explanation suggests that the opacity inherent in DAFs is particularly salient for foundation donors. Indeed, if a foundation donor intends to direct funds to an operating charity, obscuring public disclosures is the main concrete advantage that the donor would get from moving the funds through a DAF rather than granting them immediately to the operating charity.

To examine this case in which disclosure effects are prominent, we test whether the extent to which DAF sponsors receive private foundation grants is predictive of DAF giving rates to politically engaged charities. To identify sponsor reliance on private foundation grants, we build a data set of all Form 990-PF filings in our analysis timeframe (2020–2022). Because 990-PF disclosures of grant recipients do not require listing of recipient EINs, we then conduct a fuzzy logic matching algorithm to connect private foundation grants to DAF recipients.[12]

Using this matching algorithm for each year under analysis, we then calculate the percentage of each DAF sponsor’s total contributions that were identified as coming from private foundations, PctPF it . To remove outliers generated in the matching process, we excluded any PctPF it observations greater than 100 % (again winsorizing the variable at the 1 %-level for consistency).[13] This process yields 2,427 organization-year observations. With this sample, we then re-examine determinants of political giving using the following regression:

As in Sections 3.3 and 3.4, we estimate this regression for different categorizations of political giving and different measures of DAF reliance. Table 5 presents the regression results.

DAF sponsor giving to politically engaged charities and private foundation funding.

| Panel A: Overall political giving | ||

|---|---|---|

| DV = PctPolitical it | DV = PctPolitical it | |

| Intercept | 0.0053** | 0.0053** |

| (0.0023) | (0.0024) | |

| NAT i | 0.0263*** | 0.0259*** |

| (0.0062) | (0.0063) | |

| SI i | 0.0084*** | 0.0091*** |

| (0.0030) | (0.0030) | |

| PctGrantsDAF it | 0.0133*** | |

| (0.0042) | ||

| PctContribDAF it | 0.0134*** | |

| (0.0041) | ||

| PctPF it | 0.0608*** | 0.0611*** |

| (0.0131) | (0.0131) | |

| Year Fixed Effects? | Y | Y |

|

|

||

| N | 2,427 | 2,427 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.055 | 0.055 |

| Panel B: Giving to political-engagement categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = PctPoliticking it | DV = PctPoliticking it | DV = PctLobbying it | DV = PctLobbying it | DV = PctHate it | DV = PctHate it | |

| Intercept | 0.0028*** | 0.0030*** | 0.0046** | 0.0044** | −0.0001* | −0.0001* |

| (0.0008) | (0.0008) | (0.0021) | (0.0021) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |

| NAT i | 0.0138*** | 0.0139*** | 0.0153*** | 0.0149*** | 0.0004* | 0.0004 |

| (0.0030) | (0.0030) | (0.0044) | (0.0044) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | |

| SI i | 0.0017 | 0.0019* | 0.0060** | 0.0065*** | 0.0000 | 0.0001 |

| (0.0012) | (0.0012) | (0.0025) | (0.0024) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |

| PctGrantsDAF it | 0.0042*** | 0.0095*** | 0.0003*** | |||

| (0.0016) | (0.0034) | (0.0001) | ||||

| PctContribDAF it | 0.0040*** | 0.0101*** | 0.0003*** | |||

| (0.0015) | (0.0034) | (0.0001) | ||||

| PctPF it | 0.0216*** | 0.0217*** | 0.0398*** | 0.0402*** | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0103) | (0.0104) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | |

| Year Fixed Effects? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

|

|

||||||

| N | 2,427 | 2,427 | 2,427 | 2,427 | 2,427 | 2,427 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.035 |

-

These tables present regression results estimating the percent of a DAF sponsor’s annual grants that are made to politically engaged charities (PctPolitical it , PctPoliticking it , PctLobbying it , or PctHate it ) to measure the connection between grants to politically engaged charities and sponsor type (NAT i and SI i ), degree of reliance on DAFs (PctGrantsDAF it or PctContribDAF it ), and degree of private foundation support (PctPF it ). Standard errors clustered at EIN are denoted in parentheses below the coefficient estimates. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1-, 5-, and 10-% levels, respectively, using two-tailed tests.

The results in Table 5 confirm that even after controlling for level of private foundation support, reliance on DAFs remains a consistent predictor of politically engaged giving, and national sponsors continue to exhibit higher politically engaged giving rates. The results also show that private foundation support is an additional and significant predictor of DAF sponsor giving to politically engaged charities. The more that a DAF sponsor’s funding comes from private foundations, the greater the sponsor’s percentage of grants to politically engaged charities, with a positive coefficient estimate (p < 0.01) in each specification of DAF reliance as shown in Panel A. This relationship persists across political engagement categories (p < 0.01) as shown in Panel B, except in the case of giving to hate and anti-government groups. In the case of hate group giving, the statistically insignificant nature of the positive coefficient may reflect the infrequent nature of such giving.

In addition to demonstrating that a foundation to DAF to politically engaged charity pipeline is more than anecdotal, these results also provide evidence consistent with the notion that a key advantage underlying foundation-to-DAF giving – namely, the circumvention of disclosure requirements – drives greater DAF giving to politically engaged charities.

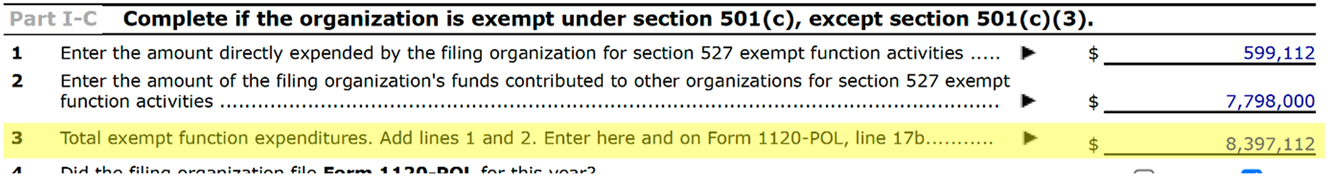

To get a sense of the economic significance of these relationships, the next figure makes use of the regression results in Table 5, Panel A to present predicted values for the percentage of grants that are made to politically engaged charities for six different scenarios: (i) a community foundation with 10 % of its contributions in DAFs that received no private foundation grants, (ii) a community foundation with 75 % of its contributions in DAFs that received no private foundation support; (iii) a community foundation with 75 % of its contributions in DAFs that received 10 % of its support from private foundations; and (iv)-(vi) the same scenarios for a representative national sponsor. These scenarios represent reasonable bounds for funding estimates; for DAF contributions, 10 % is a lower bound on DAF reliance and 75 % approximates the upper quartile of DAF reliance in the sample, while for private foundation funding, zero support reflects a lower bound on private foundation reliance and 10 % support approximates the upper quartile of private foundation reliance in the sample.

As the regression results and estimates in Figure 5 demonstrate, not only are DAFs disproportionately used to fund politically engaged charities, but this effect is increased when DAF sponsors get more of their own support from private foundations. The increase tied to private foundation funding is not only statistically significant but also notable in its magnitude. This suggests that regulators should be aware not only of the potential for private foundations to use grants to DAFs to meet payout requirements but also that they can – and evidence suggests they do – use DAFs to anonymize giving to politically engaged charities.

Estimated political giving rates for DAF sponsor scenarios.

4 Conclusions

Donor-advised funds have brought a quiet revolution to philanthropy in the United States, fundamentally transforming the ways in which donors give to charity. But we do not yet fully understand the totality of the sea change they have brought. This paper aims to illuminate an important aspect of the donor-advised fund boom: the extent to which DAFs facilitate giving to organizations that are politically engaged, either through lobbying or affiliations with other organizations engaged in politicking/electioneering.

Using the electronic IRS filings of charitable organizations for the three most recent years available, we find that DAF sponsors consistently fund politically engaged charities at markedly higher rates than other funding sources. This pattern is most pronounced among national sponsors, and among sponsors who are heavily reliant on DAFs. We demonstrate that DAFs also facilitate disproportionate giving to hate and anti-government groups – charities at the extreme fringe of political engagement. Finally, we find evidence that private foundation donors are particularly apt to use DAFs as a way to move funds to politically engaged charities – a strategy that suggests that when making politically-charged gifts, foundation donors are aware of, and making use of, the relaxed disclosure rules of DAFs.

Together, these findings are consistent with the notion that while there are many aspects of DAFs that are appealing to donors and have fueled their growth, the opportunity to use them to make gifts to politically engaged charities while limiting disclosure of donor identities is a key factor that distinguishes them from other means of giving. As we are now in an environment that increasingly exhibits politicization of nonprofit activity (Cai et al. 2025), these incentives are likely to be magnified in the coming years.

There are, of course, legitimate reasons why donors might want their giving to be anonymous, particularly when they fear persecution of their grantees. And charities have a long history of responsible, effective civic engagement. But to the extent that policymakers find it important for recipient charities, oversight bodies, and the taxpaying public to understand the funding sources of political organizations, DAFs represent a clear challenge. Even more so since DAFs can also provide an end-run around the transparency requirements on private foundations. Various policy reforms have been proposed that speak to these concerns, including requiring that DAFs disclose their major donors and grantees, at least to the IRS, on an individual account level; requiring that DAFs be subject to the same disclosure requirements as private foundations; and preventing foundation grants to DAFs from counting towards their charitable distribution requirement.

Regardless of if and how policy makers should respond, our findings suggest that DAFs represent a sizeable, systematic, and perhaps underappreciated source of support for politically engaged activities – a source that is not just theoretical, but rather empirical reality.

Appendix A : Example of Political Engagement Classification

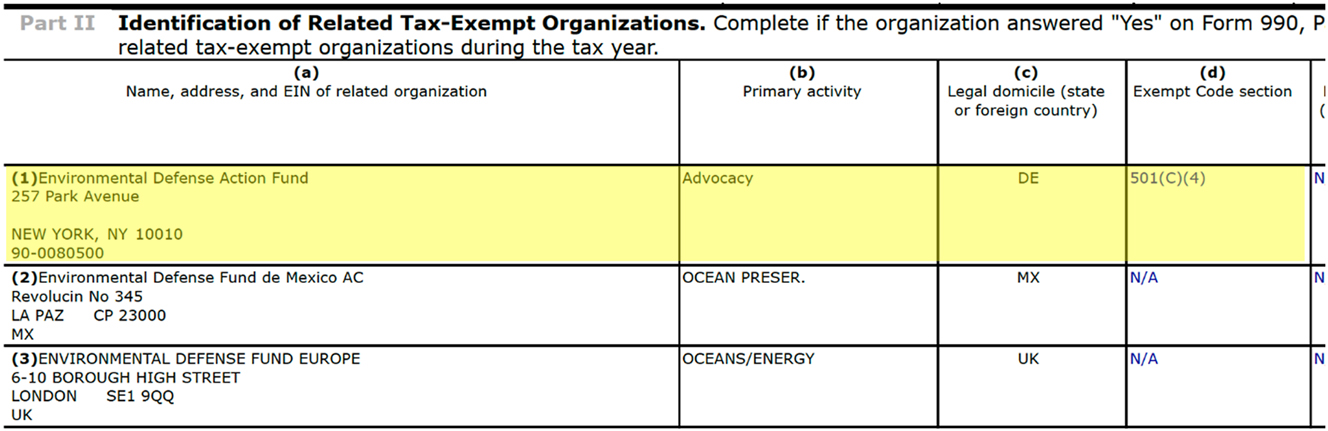

To illustrate our political engagement classification methodology, we explain here how we categorize Environmental Defense Fund Incorporated (EIN 11-6107128) for its fiscal year ended 9/30/22. This organization discloses no direct politicking (Form 990, Part IV, line 3), nor does it disclose any campaign expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-A, line 2). However, it does disclose a related affiliate that is a 501(c)(4) organization – Environmental Defense Action Fund (EIN 90-0080500) – as shown in its Form 990 Schedule R below.

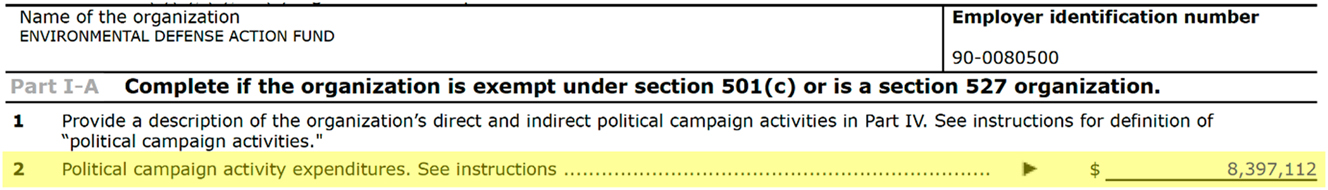

Examining the filing of the 501(c)(4) affiliate reveals that it did engage in direct political activity, reporting over $8 million in campaign activity expenditures in its Form 990, Schedule C below.

Given this disclosure, we classify Environmental Defense Fund Incorporated as a politicking charity in 2022. A second way Environmental Defense Fund Incorporated can be classified as a politicking charity is because its 501(c)(4) affiliate discloses section 527 exempt function expenditures on its Schedule C disclosure below.

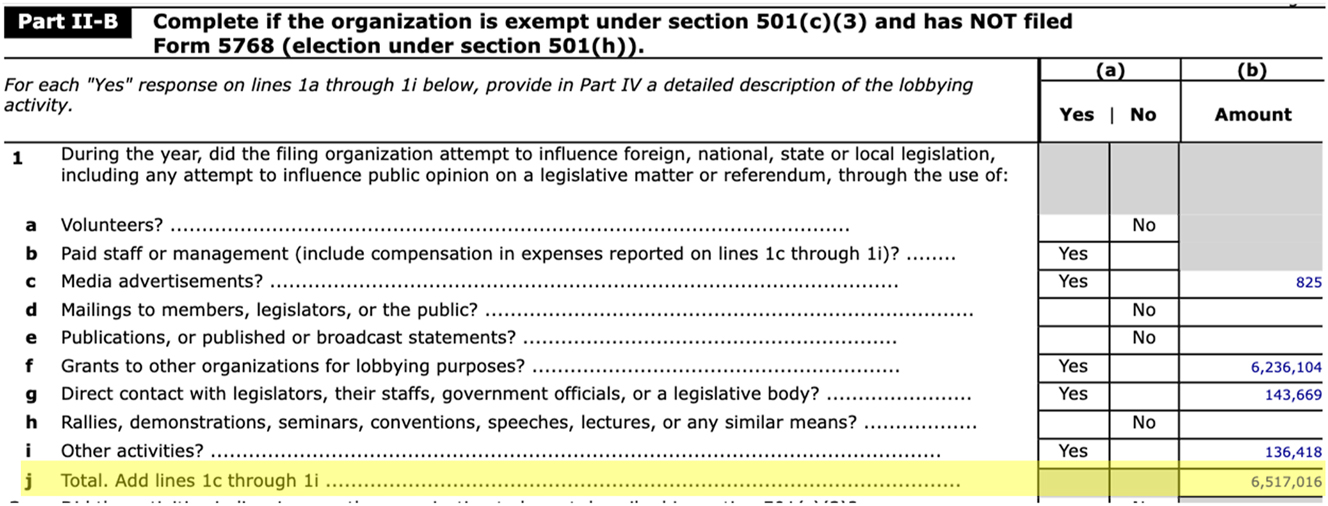

To classify an organization as a lobbying charity, we look at any lobbying the charity engaged in itself, rather than any lobbying its related entities may have done. Environmental Defense Fund Incorporated did not seek a section 501(h) election, but it did disclose lobbying expenditures totaling over $6.5 million on its Form 990, Schedule C, Part II-B, as seen below.

The disclosed lobbying amount of $6,517,016 represented 2.4 % of Environmental Defense Fund Incorporated’s total reported expenses of $272,766,121 (Form 990, Part I, line 18). Since lobbying exceeds 1 % of expenses, we deem it nontrivial and classify Environmental Defense Fund Incorporated as a lobbying charity in 2022.

Appendix B : Classification of Politically Engaged Charities

Charities Engaging in or Indirectly Supporting Politicking (Politicking Charities)

Any 501(c)(3) public charity that satisfies any of the following:

Engaged in political activities for or against candidates running for office (Form 990, Part IV, Line 3).

Reports campaign activity expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-A, Line 2).

Reports having paid an excise tax under section 4955 (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-V, Line 1 or 2).

Lists a related party on Form 990 Schedule R, Part II, Column (d) that is a 527.

Lists a related party on Form 990 Schedule R, Part II, Column (d) that is a 501(c)(4) which incurred section 527 exempt function expenditures, as reported on Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-C, Line 3.

Lists a related party on Form 990 Schedule R, Part II, Column (d) that is a 501(c)(4) which filed a Form 1120-POL (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-C, Line 4).

Lists a related party on Form 990 Schedule R, Part II, Column (d) that is a 501(c)(4) which engaged in political activities for or against candidates running for office (Form 990, Part IV, Line 3).

Lists a related party on Form 990 Schedule R, Part II, Column (d) that is a 501(c)(4) which reports campaign activity expenditures (Form 990, Schedule C, Part I-A, Line 2).

Charities Engaging in Nontrivial Lobbying (Lobbying Charities)

Any 501(c)(3) public charity that satisfies either of the following:

Has a section 501(h) election and reports lobbying expenditures (from Form 990, Schedule C, Part II-A, line 1c, column(a)) that exceed 1 % of their total expenses (from Form 990, Part I, Line 18).

Does not have a section 501(h) election but reports lobbying expenditures (from Form 990, Schedule C, Part II-B, line 1j, column(b)) that exceed 1 % of their total expenses (from Form 990, Part I, Line 18).

Appendix C : Variable Definitions

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Assets it | End-of-year assets reported on Form 990, Part I, Line 20 for organization i in year t, reported in US dollars adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels. |

| CF i | Indicator variable equal to 1 if sponsor i is a community foundation. Community foundations are any sponsors that have NTEE codes starting with T31 or that have “foundation” or “trust” and a U.S. geographical reference in their name (without reference to a single-issue group). |

| Contrib it | Contributions, gifts, and grants reported on Form 990, Part VIII, line 1h, less government grants (Form 990, Part VIII, Line 1e), for organization i in year t, reported in US dollars adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels. |

| IDGrants it | Total value of grants by sponsor i in year t disclosed on Form 990, Schedule I for which the recipient has a valid EIN and filed a Form 990 in year t, reported in US dollars adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels. |

| NAT i | Indicator variable equal to 1 if sponsor i is considered a national sponsor. National sponsors are identified based on a list maintained by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), presented in Appendix D. |

| PctContribDAF it | Aggregate value of contributions to DAFs reported on Form 990, Schedule D, Part I, Line 2(a) for sponsor i in year t, adjusted for inflation and divided by Contrib it . |

| PctGrantsDAF it | Aggregate value of grants from DAFs reported on Form 990, Schedule D, Part I, Line 3(a) for sponsor i in year t, divided by total grants paid on Form 990, Part I, Line 13. |

| PctHate it | Total amount of grants by sponsor i in year t disclosed on Form 990, Schedule I to EINs included in the Southern Poverty Law Center list of hate groups and anti-government organizations, adjusted for inflation, divided by IDGrants it . |

| PctLobbying it | Total amount of grants by sponsor i in year t disclosed on Form 990, Schedule I to EINs included in the list of lobbying organizations (as identified in Appendix B), reported in US dollars adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels, divided by IDGrants it . |

| PctPF it | The percentage of sponsor i’s total contributions that came from private foundations in year t. Calculated as total private foundation grants matched to sponsors using a fuzzy logic algorithm, adjusted for inflation, and divided by Contrib it . |

| PctPolitical it | Total amount of grants by sponsor i in year t disclosed on Form 990, Schedule I to EINs included in the list of politically engaged organizations (as identified in Appendix B), reported in US dollars adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels, divided by IDGrants it . |

| PctPoliticking it | Total amount of grants by sponsor i in year t disclosed on Form 990, Schedule I to EINs included in the list of politicking organizations (as identified in Appendix B), reported in US dollars adjusted for inflation to 2022 levels, divided by IDGrants it . |

| SI i | Indicator variable equal to 1 if DAF sponsor i is not classified as either a community foundation or national sponsor. |

Appendix D : National Donor-Advised Fund Sponsors

| Employer ID number | Sponsor |

|---|---|

| 01-0782573 | Advisors Charitable Gift Fund |

| 82-1517696 | Amalgamated Charitable Foundation |

| 34-1747398 | American Endowment Foundation |

| 51-6506426 | American Gift Fund |

| 81-0739440 | American Online Giving Foundation |

| 84-1260437 | AMG Charitable Gift Foundation |

| 14-1782466 | Ayco Charitable Foundation |

| 04-6010342 | Bank of America Charitable Gift Fund |

| 13-7111099 | Bessemer National Gift Fund |

| 30-0748315 | BNY Mellon Charitable Gift Fund |

| 43-1634280 | Charities Aid Foundation America |

| 86-3177440 | Daffy Charitable Fund |

| 26-0724604 | Dechomai Asset Trust |

| 06-1676688 | Dechomai Foundation |

| 87-1569770 | DonateStock Charitable |

| 46-0942102 | Donatewell |

| 54-1934032 | Donors Capital Fund |

| 52-2166327 | Donors Trust |

| 11-0303001 | Fidelity Investments Charitable Gift Fund |

| 04-6649138 | Fiduciary Charitable Foundation |

| 13-3848582 | FJC |

| 04-3296043 | Fund For Charitable Giving |

| 26-2449481 | Give Back Foundation |

| 11-3813663 | Goldman Sachs Charitable Gift Fund |

| 31-1774905 | Goldman Sachs Philanthropy Fund |

| 20-0849590 | Greater Horizons |

| 77-0558454 | Harris MYCFO Foundation |

| 39-6659806 | Hills Bank Donor Advised Gift Fund |

| 47-3574130 | Impact Investing Charitable Foundation |

| 81-2375745 | Impact Investing Charitable Trust |

| 26-2048480 | ImpactAssets |

| 47-2088631 | Jasper Ridge Charitable Fund |

| 30-0233491 | Johnson Charitable Gift Fund |

| 94-3331010 | JustGive |

| 27-2499903 | MightyCause Charitable Foundation |

| 52-7082731 | Morgan Stanley Global Impact Funding Trust |

| 23-7825575 | National Philanthropic Trust |

| 20-4326440 | NCF Charitable Trust |

| 27-4357830 | Nema Foundation |

| 68-0480736 | Network For Good |

| 27-7059768 | NPT Charitable Asset Trust |

| 84-3037939 | NPX Charitable |

| 45-0931286 | PayPal Charitable Giving Fund |

| 94-3136771 | Philanthropic Ventures Foundation |

| 94-3396165 | R S F Global Community Fund |

| 59-3652538 | Raymond James Charitable Endowment Fund |

| 35-2129262 | Renaissance Charitable Foundation |

| 13-6082763 | Rudolf Steiner Foundation |

| 31-1640316 | Schwab Charitable Fund |

| 43-1890105 | Servant Foundation |

| 84-2049692 | Stifel Charitable |

| 31-1709466 | T Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving |

| 41-2010078 | The American Center for Philanthropy |

| 95-4124436 | The Fuller Foundation |

| 81-2576201 | The Independent Charitable Gift Fund |

| 31-1663020 | The US Charitable Gift Trust |

| 47-2199684 | TIAA Charitable |

| 51-0198509 | Tides Foundation |

| 20-4286082 | United Charitable |

| 01-0702102 | Univest Foundation |

| 23-2888152 | Vanguard Charitable Endowment Program |

References

Andreoni, J. 2018. “The Benefits and Costs of Donor Advised Funds.” Tax Policy and the Economy 32 (1): 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1086/697137.Search in Google Scholar

Andreoni, J., and R. Madoff. 2023. Calculating DAF Payout and What We Learn When We Do It Correctly. NBER Working Paper.Search in Google Scholar

Aprill, E. 2011. “Regulating the Political Speech of Noncharitable Exempt Organizations After Citizens United.” Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 10 (4): 363–405. https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2011.0109.Search in Google Scholar

Aprill, E., R. Colinvaux, B. Galle, P. Hackney, and L. H. Mayer. 2023. “Response by Tax-Exempt Organization Scholars to Request for Information.” Loyola Law School, Los Angeles Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2023-24. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4562367 (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Berman, L. 2015. “Boston College Law Forum on Philanthropy and the Public Good.” Donor Advised Funds in Historical Perspective 1: 5–27.Search in Google Scholar

Brody, E. 2012. “Sunshine and Shadows on Charity Governance: Public Disclosure as a Regulatory Tool.” Florida Tax Review 183: 175–206.Search in Google Scholar

Brunson, S. 2020. “‘I’d Gladly Pay You Tuesday for a [Tax Deduction] Today:’ Donor-Advised Funds and the Deferral of Charity.” Wake Forest Law Review 55 (2): 245–86.Search in Google Scholar

Cai, S., B. Johansen, and I. Sentner. 2025. “Trump’s War on Nonprofits.” Politico. April 18. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/west-wing-playbook-remaking-government/2025/04/18/trumps-war-on-nonprofits-00299472 (accessed May 30, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Colinvaux, R. 2014. “Political Activity Limits and Tax Exemption: A Gordian’s Knot.” Virginia Tax Review 34: 1–61.Search in Google Scholar

Colinvaux, R. 2017. “Donor Advised Funds: Charitable Spending Vehicles for 21st Century Philanthropy.” Washington Law Review 92 (1): 39–86.Search in Google Scholar

Colinvaux, R. 2019. “Social Welfare and Political Organizations: Ending the Plague of Inconsistency.” NYU Journal of Legislation & Public Policy 21 (2): 481–517.Search in Google Scholar

Colinvaux, R., and R. Madoff. 2019. “Charitable Tax Reform for the 21st Century.” Tax Notes 164 (12): 1867–75.Search in Google Scholar

Flannery, H. 2023. “Private Foundations Gave $2.6 Billion in Grants to National Donor-Advised Funds in 2021.” Institute for Policy Studies. https://inequality.org/great-divide/private-foundations-dafs-2021/ (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Flannery, H. 2024. “Ten of America’s 20 Top Public Charities are Donor-Advised Funds.” Institute for Policy Studies. https://inequality.org/great-divide/top-public-charities-dafs/ (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Flannery, H., C. Collins, and B. DeVaan. 2023. “The True Cost of Billionaire Philanthropy.” Institute for Policy Studies. https://ips-dc.org/report-true-cost-of-billionaire-philanthropy/ (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Flannery, H., and B. Mittendorf. 2025a. “Reshaping Charity Channels: How Assets Flow into and Out of Donor-Advised Funds.” In Nonprofit Operations and Supply Chain Management, edited by G. Berenguer, and M. Sohini, 47–71. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.10.1007/978-3-031-74994-0_4Search in Google Scholar

Flannery, H., and B. Mittendorf. 2025b. “Charitable Objectives or Donor Interests? What Sponsor Language Reveals About Donor-Advised Fund Priorities and Resource Flows.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640251331853 (Epub ahead of print).Search in Google Scholar

Froehlich, M. 2023. “DAF vs. Private Foundations: Which Giving Strategy is Right for You?” Kiplinger Personal Finance. July 5. https://www.kiplinger.com/personal-finance/daf-vs-private-foundation-which-giving-strategy-is-right-for-you (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Galle, B. 2020. “The Dark Money Subsidy? Tax Policy and Donations to Section 501(c)(4) Organizations.” American Law and Economics Review 22 (2): 339–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahaa009.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbons, K. 2021. “Show me the Money: Addressing the Oversight Gap in Private Foundation Donations to Donor-Advised Funds.” Minnesota Law Review 106: 1583–623.Search in Google Scholar

Grasse, N., K. Ward, and K. Miller-Stevens. 2021. “To Lobby or Not to Lobby? Examining the Determinants of Nonprofit Organizations Taking the IRS 501(h) Election.” Policy Studies Journal 49 (1): 242–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12349.Search in Google Scholar

Hackney, P., and B. Mittendorf. 2017. “Donor-Advised Funds: Charities with Benefits.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/donor-advised-funds-charities-with-benefits-74516 (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Heist, H., and D. Vance-McMullen. 2019. “Understanding Donor-Advised Funds: How Grants Flow During Recessions.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48 (5): 1066–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019856118.Search in Google Scholar

Internal Revenue Service. 2023. Internal Revenue Service Data Book. Washington: Publication 55-B.Search in Google Scholar

Kotch, A. 2023. “How Fidelity, Schwab, and Vanguard Fund Hate Groups.” New Republic. August 9. Available at https://newrepublic.com/article/172927/fidelity-schwab-vanguard-charitable-donor-advised-funds-hate-groups (accessed October 7, 2024).10.1002/nba.31681Search in Google Scholar

Koulish, J. 2016. “From Camps to Campaign Funds: The History, Anatomy, and Activities of 501 (c)(4) Organizations.” Urban Institute Research Paper. http://www.urban.org/research/publication/camps-campaign-funds-historyanatomy-and-activities-501c4-organizations (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

MacIndoe, H., E. E. Beaton, M. P. de Athayde, and O. Ojelabi. 2025. “Giving Voice: Examining the Tactical Repertoires of Nonprofit Advocacy for Disadvantaged Populations.” Nonprofit Policy Forum 16 (1): 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2023-0054.Search in Google Scholar

Mann, E., and J. Calvert. 2021. “ACE Act: Legislation would Significantly Affect Donor-Advised Funds.” Reuters. November 11. https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/ace-act-legislation-would-significantly-affect-donor-advised-funds-2021-11-11/ (accessed October 7, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Mayer, L. H. 2018. “When Soft Law Meets Hard Politics: Taming the Wild West of Nonprofit Political Involvement.” Journal of Legislation 45: 194–234.Search in Google Scholar

Montgomery, D. 2018. “Hate List Gets Pushback from Conservatives.” The Washington Post. November 8.Search in Google Scholar

Mosely, J., D. Suarez, and H. Hwang. 2023. “Conceptualizing Organizational Advocacy Across the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector: Goals, Tactics, and Motivation.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 52 (Suppl. 1): 187S–211S. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221103247.Search in Google Scholar

Pekkanen, R., S. Rathgeb Smith, and Y. Tsujinaka, eds. 2014. Nonprofits & Advocacy: Engaging Community and Government in an Era of Retrenchment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Post, M., and E. Boris. 2023. “Nonprofit Political Engagement: the Roles of 501(c)(4) Social Welfare Organizations in Elections and Policymaking.” Nonprofit Policy Forum 14 (2): 131–55. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2021-0061.Search in Google Scholar

Post, M., E. Boris, and C. Stimmel. 2023. “The Advocacy Universe: a Methodology to Identify Politically Active 501(c)(4) Organizations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 52 (1): 260–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211066495.Search in Google Scholar

Prentice, C. 2018. “The ‘State’ of Nonprofit Lobbying Research: Data, Definitions, and Directions for Future Study.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47 (Suppl. 4): 204S–217S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764018758957.Search in Google Scholar

Reiser, D. B., and S. Dean. 2023. For-Profit Philanthropy: Elite Power and the Threat of Limited Liability Companies, Donor-Advised Funds, and Strategic Corporate Giving. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Suarez, D. 2020. “Advocacy, Civic Engagement, and Social Change.” In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, edited by W. Powell, and P. Bromley, 491–506. Stanford: Stanford University Press.10.1515/9781503611085-028Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, T. 2022. “Democracy Dies In…Charitable Donations? Unpacking the Supreme Court’s Decision in Americans for Prosperity v. Bonta.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 31 (3): 499–526.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.