Abstract

Interference between the electric and magnetic dipole-induced in Mie nanostructures has been widely demonstrated to tailor the scattering field, which was commonly used in optical nano-antennas, filters, and routers. The dynamic control of scattering fields based on dielectric nanostructures is interesting for fundamental research and important for practical applications. Here, it is shown theoretically that the amplitude of the electric and magnetic dipoles induced in a vanadium dioxide nanosphere can be manipulated by using laser-induced metal-insulator transitions, and it is experimentally demonstrated that the directional scattering can be controlled by simply varying the irradiances of the excitation laser. As a straightforward application, we demonstrate a high-performance optical modulator in the visible band with high modulation depth, fast modulation speed, and high reproducibility arising from a backscattering setup with the quasi-first Kerker condition. Our method indicates the potential applications in developing nanoscale optical antennas and optical modulation devices.

1 Introduction

Subwavelength dielectric nanoparticles exhibit multi-order Mie resonance, i.e., electric dipole (ED) and magnetic dipole (MD), electric quadrupole (EQ), and quadrupole (MQ), etc., which can trap energy in space and time domain, thus have received intensive and extensive studies in recent years [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. It is widely utilized in the fields of enhanced light–matter interaction [6], [7], [8], nonlinear optics [9], [10], nano-optical antennas [11], [12], [13], and optical sensing [14], [15], [16]. Since the Mie resonance of dielectric nanoparticles can be controlled by optimizing the geometric parameters, the scattered field can be tailored through the interference between the electric and magnetic dipoles supported by nanoparticles [5], [12], [17], [18]. When the electric and magnetic dipoles perfectly constructively or destructively interfere, it leads to pure backward and forward scattering (BS/FS), known as the first and second Kerker conditions, respectively [4], [19], [20]. In addition, it has then been extended to other shapes of Mie nanostructure to manipulate scattering not only at the forward and backward directions but also other possible scattering angles be referred to as the generalized Kerker effect [21], [22], [23], such as transverse scattering induced by interference between high order Mie resonance [24], [25], [26], [27], which is widely utilized in high-efficiency directionally radiating optical nano-antennas.

Nanoscale all-optical modulators can control and manipulate light on the optical wavelength length scale, which is widely utilized in communications, sensing, and optical data storage. So far, all-optical modulators are mainly based on the electro-optic effect [28], [29], [30], thermo-optic effect [31], [32], [33], optical nonlinear Kerker effect [19], [34], [35], [36], [37], carrier injection [38], [39], [40] and so on. Despite the above methods having been widely utilized in industry and studied in academic research, a bottleneck issue, only a little change of dielectric constant can be realized. Phase-change materials (PCMs) can drastically change the refractive index by changing the lattice of the substance under an external heating excitation, which has been widely utilized in the field of photonic devices such as optical data storage [41] and optical switching [42]. Among them, Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) has the ability to realize a dramatic optical contrast (δ n > 2) between these two states in response to crystallization or amorphization processes. Strong and omnidirectional light absorption from ultraviolet to near-infrared using GST metasurface. Active control of anapole states by structuring the phase-change alloy GST. Dynamic thermal emission control based on ultrathin plasmonic metamaterials, including phase-changing material GST. Also, vanadium dioxide (VO2) exhibits a reversible insulator-metal transition (IMT) at near room temperature (T c = 68 °C) with a large refractive index contrast and fast switching time, which has attracted great interest in recent years in the field of optical modulators [32], [43], [44]. Despite great success in building VO2-based optical modulation devices with various functionalities, there are limitations that need to be improved. First, current VO2-based optical modulators are mainly based on the heating platform experimental setup, resulting in slow modulation speeds. Second, the refractive index constant between the insulator phase and the metal phase of VO2 is only noticeably manifested in the infrared band [31], [45], [46], resulting in the difficult implementation of optical modulators in the visible band. It has been shown that VO2 reproducible optical modulators demonstrated using the photothermal effect of a pulsed laser [47]. Owing to plasmons antenna-assisted nanoscale VO2 excitation at short-wave infrared, it has 20 times reduced switching energies and 5 times faster recovery times than a VO2 film without antennas [47]. In addition, combining VO2 with localized plasmon resonance of Au nanoparticles demonstrated an optical modulator in the visible region with modulation depths of ∼31 % in the 630 nm [48]. Although considerable efforts have been made, the nanoscale optical modulators in visible bands with high modulation depths are still quite challenging.

In this article, we have theoretically proposed and experimentally demonstrated the dynamic control of the directional scattering of a single Mie sphere with photo-thermal induced metal-insulator transitions. As a proof-of-principle application, we have demonstrated a high modulation depth and high reproducibility optical modulator in the visible band using a backscattering setup with the quasi-first Kerker condition.

2 Results and discussion

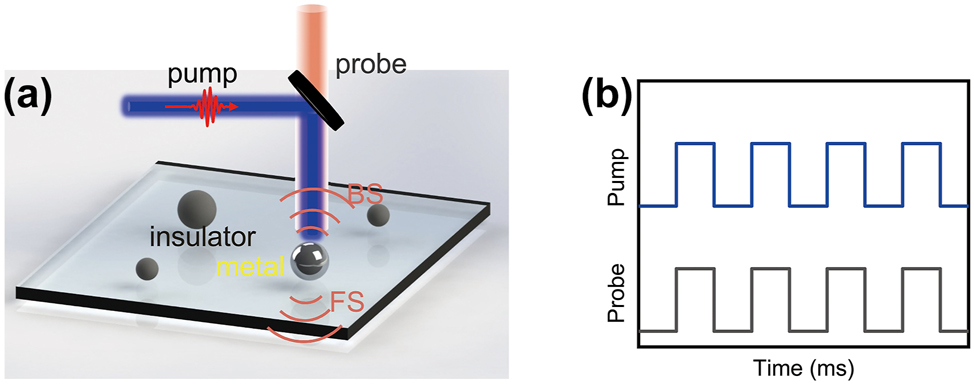

Figure 1(a) shows the schematic of an all-optical VO2 modulator exciting with a 488 nm laser and probing the scattering light with a broadband white light source in the forward/backward direction. Insulating state VO2 nanoparticles (NPs) fabricated by using fs laser ablation [9] were randomly placed on the quartz slide at room temperature, which can transition metal using 488 nm laser-induced photothermal in situ with a reversible process, as shown in Figure 1(b). The quality of VO2 NP can be improved by using femtosecond laser ablation with a short focal length objective [49]. Also, the state-of-the-art nanofabrication techniques using electron-beam lithography combined with dry etching can improve the morphological diversity of the VO2 nanostructure [50]. Unlike phase transition performed by a heating platform, the photo-thermal induced phase transition has a femtosecond response time and can be achieved by in situ localized heating [47], [51], [52].

Schematic of the optical VO2 NPs modulator. (a) Experimental schematic of dynamic control of directional scattering of single VO2 NPs by the laser induced IMT. (b) Schematic comparison of phase transition modulation schemes is that the modulated successive optical pump pulses (blue) acts on the particle in conjunction with the probe light (black).

The refractive index of the VO2 crystal in insulating and metallic state Ref. [53]. In the insulating state, the refractive index real part n can be up to 3 with a negligible imaginary part k, resulting in a notable Mie resonance in the visible. In contrast, since the presence of a high density of electrons in the metallic state VO2, there is a significant absorption with a sizeable imaginary part k of the refractive index, as shown in Figure S1 (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1). Note that the discrepancies of the refractive index between the metallic and insulating phases are obscure in the visible region, implying that it is difficult to realize a VO2-based optical modulator in the visible [54].

Figure 2(a) shows the FS and BS spectrum of VO2 NP with a diameter d = 270 nm for the insulating state. One can see that the far-field radiated power density dominated by FS. Also, we have simulated the evolution of the full-field/forward/backward scattering spectrum with increasing diameter (d) calculated for VO2 NPs in insulating state, as shown in Figure S2 (see Supplementary Material, Figure S2). One resonance peak is observed for the FS spectrum, which redshifts gently with increasing diameter. In contrast, the peak of the backscattering spectrum rushes from 500 to 800 nm, following a high-order resonance peak at a large diameter. Since the coherence effects between electric and magnetic dipoles, one can tailor the far-field scattering of VO2 NPs. Figure 2(b) shows that electric and magnetic dipoles result in zero-BS, which is called the first Kerker condition. Such sources are interesting as elements of small antennas to realize ‘Huygens’ metasurface [19], [55]. Correspondingly, anti-phase electric and magnetic dipoles induce pure BS, which is called the second Kerker condition.

Directional scattering spectra of insulating phase VO2 NPs. (a) Simulated FS (black) and BS (red) spectra of VO2 NP for radius d = 270 nm. (b) Schematic showing directional radiation patterns induced by the interference between of MD and ED. The inset showing the 3D radiation pattern at quasi first Kerker condition 640 nm. (c) Decomposition of the total scattering spectra simulated for an insulating phase VO2 NP with d = 270 nm. (d) Measured scattering spectra of VO2 NP with radius d ∼ 270 nm at BS (black) and FS (blue). The FS imaging, backs cattering imaging recorded by using a charge-coupled device (CCD) and SEM image of the VO2 NP are shown in the insets. The length of the scale bar is 500 nm.

To gain deeper insight into a link between dipole moments of insulating and metallic state, we decomposed the total scattering spectra of a VO2 NP with d = 270 nm by multipole expansion theory in the Cartesian coordinate system [56], [57], as shown in Figure 2(c). In this case, the multipole moments induced in the VO2 NPs can be calculated by integrating the induced polarization currents over the volume of the VO2 NP, including the multipoles: electric dipole (ED), magnetic dipole (MD), electric quadrupole (EQ), magnetic quadrupole (MQ), and toroidal dipole (TD). The calculations are expressed as follows: ED: p = ∫

Pdr. MD:

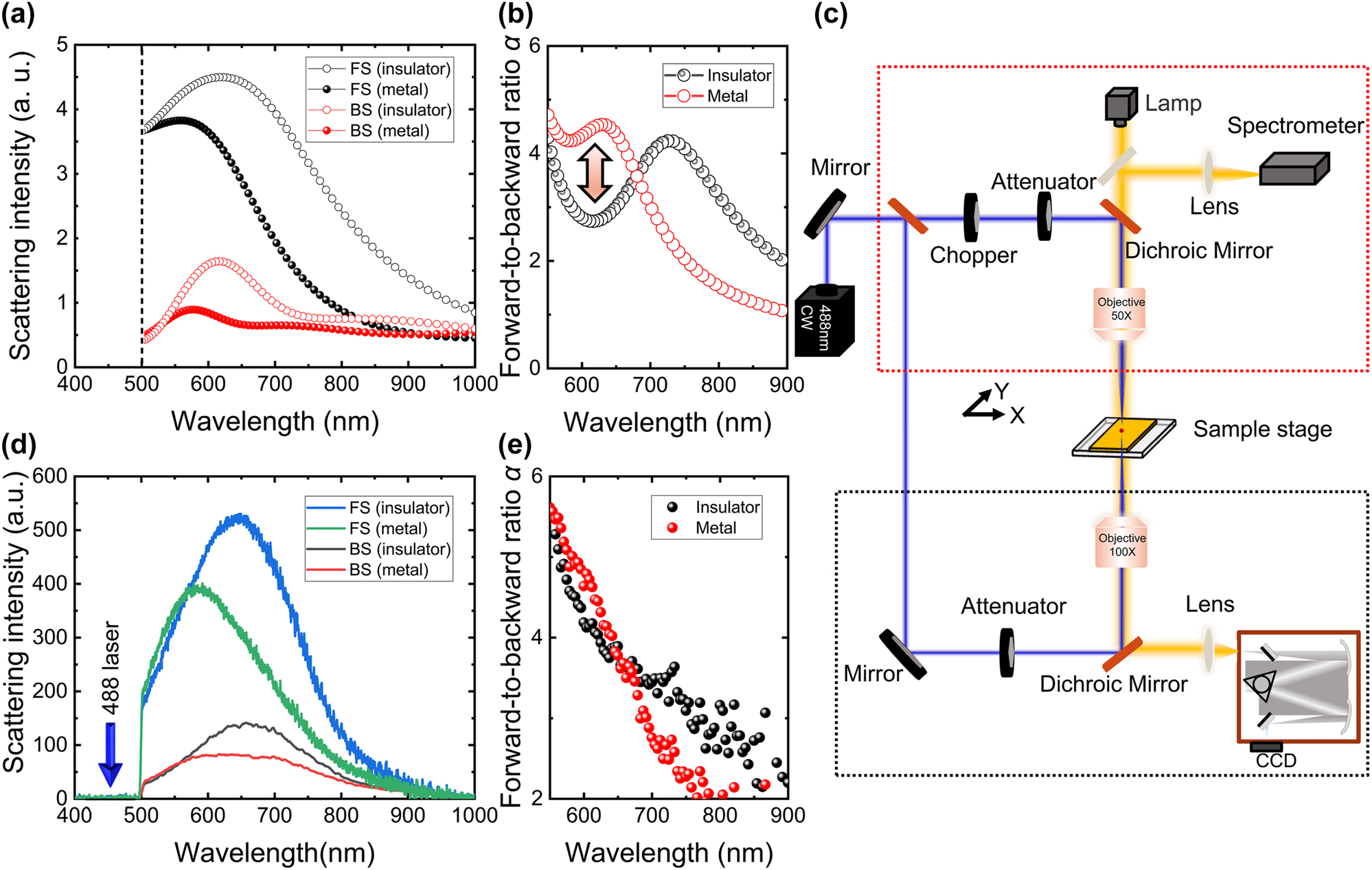

The multipole moments of the VO2 NP with the metallic state are shown in Figure S5 (see Supplementary Material, S5). Comparing the multipole moments of the insulator VO2, it can be seen that the ratio of ED and MD amplitudes for the metallic state can be up to 70 %, resulting in a significantly reduced BS at the quasi-first Kerker’s wavelength ∼640 nm. Figure 3(a) shows simulated FS and BS spectra of VO2 NP for the insulator and metallic state. After the IMT, the BS of VO2 NP decreased by 50 % at the resonance peak ∼640 nm, while FS only reduced by approximately 20 %, resulting in a drastic increase in the forward-to-backward ratio. We have calculated the evolution of the forward-to-backward ratio with increasing wavelength for the insulator and metallic phases of VO2 NP, as shown in Figure 3(b). One can observe that the backward-to-forward scattering ratio changes from 2.4 to 4.5 when the VO2 NP transit into a metallic form insulator state, implying the directional scattering of resonant VO2 NP modulated by repeatable IMT process.

Experimental demonstration of the dynamic control directional scattering of single VO2 sphere by laser induced metal insulator transitions. (a) Simulated FS (black) and BS (red) spectra of VO2 NP for radius d = 270 nm. (b) The evolution of the forward-to-backward ratio with increasing wavelength for insulator (balck) and metallic (red) phases of VO2 NP. (c) Experimental setup of dynamic control of directional scattering of single VO2 sphere, where the red/black dashed boxes represent the BS/FS light paths, respectively. (d) Measured scattering spectra of VO2 NPs with radius d = 270 nm for FS (insulating phase is black and metallic phase is red) and BS (insulating phase is blue and metallic phase is green). (e) Experiment measured the evolution of the forward-to-backward ratio with the wavelength for insulator(balck) and metallic(red) phases of VO2 NPs.

To experimentally demonstrate this modulation effect with a rapid phase transition time, we employ a laser-induced photothermal effect to realize the IMT of VO2, as shown in Figure 3(c). In experiments, we excited the VO2 NPs by using a 488 nm continuous wave (CW) laser with a broadband probe white light. A mechanical chopper was used to demonstrate reversible phase change by controlling the number and duration of the pump laser. A 50× objective lens was used to focus the pump and probe beam onto the VO2 NP. A grating spectrometer (SR-500, Andor) and fiber spectrometer (QE pro, Ocean Insight) was utilized to measure the FS and BS spectra of the VO2 NPs, respectively. Since VO2 has a significant absorption in the violet light band, the 488 nm laser can rapidly increase the temperature of the nanoparticles, leading to an IMT, as shown in Figure 3(d). Here, the VO2 NP performed in the experiment is the same as in Figure 2(b), with a good agreement between the calculated and measured results. The dark field spectra of VO2 NPs with different diameters are shown in Figure S6 (see Supplementary Material, S6). Also, we have calculated the evolution of the forward-to-backward ratio for experimental data insulating and metallic state of VO2 NP based on Figure 3(d), as shown in Figure 3(e), which clearly shows that the forward-to-backward ratio of the VO2 NP can be manipulated using laser-induced IMT.

Furthermore, we evaluated the performance of several kinds of VO2-based optical modulator scenarios in detail, including the transmittance of VO2 film, the FS and BS spectra of the VO2 NP. Figure 4(a) shows the evolution of the transmittance with the phase transition for the VO2 film with a thickness of 240 nm, showing an obvious difference in the short-wave infrared and neglectable in the visible band. In order to quantitatively analyze the modulation of different schemes, we define the modulation depth δ = 1 − T m /T i , where T m and T i represent the response spectra of the metallic and insulating state, respectively. As previously predicted roughly using the refractive index contrast of the IMT, the modulation effect of the pure VO2 film exists mainly in the near-infrared region. Interestingly, the interaction of the electric and magnetic dipoles of VO2 NP induces directional scattering at the quasi-first Kerker’s wavelength, enabling a high-contrast spectral modulation to the visible band. Figure 4(b) shows that the FS and BS scenarios realized a high contrast modulation at 750 nm and 640 nm, with a modulation depth of 65 % and 57 %, as shown in the green and black curves, respectively. In Figure 4(c), we show the x–z plane BS radiation patterns of the VO2 NP calculated for the metallic and insulating phases for a wavelength ∼640 nm. It can be seen that the BS of the VO2 NP is radiation with different intensities, depending strongly on the state of the VO2 NP. The x–z plane FS patterns of the VO2 NP with wavelength ∼750 nm were calculated for the metallic and insulating phases, as shown in Figure S7 (see Supplementary Material, S7).

Experimental demonstration the high performance visible optical VO2 NPs modulator based on quasi-first Kerker condition. (a) The transmittance of 240 nm VO2 film for insulator (balck) and metallic (red) phases. (b) Comparison of modulation depths for FS/BS of radius d = 240 nm NP and transmission of 240 nm films. (c) The BS radiation patterns of VO2 NP with a radius d = 240 nm calculated at wavelengths of λ = 640 nm. (d) Evolution of the experimentally measured BS spectrum of VO2 NP with different pump laser intensity. (e) The dependence of intensity at the peak (∼640 nm) of the BS spectrum on the laser power (0–0.22 mW/μm2). Evolution of the BS spectral peak intensity with the critical laser power density (0.09–0.11 mW/μm2) is shown in the insets. (f) BS Spectral intensity variation of IMT process for VO2 NP under 50 Hz modulation frequency with a fixed laser power density ∼0.22 mW/μm2.

To experimentally explore the phase transition critical temperature of the VO2 NP, we have performed experiments to measure the evolution of the BS spectrum with increasing pump laser intensity, as shown in Figure 4(d). When the incident laser power density exceeds 0.1 mW/μm2, the BS intensity of VO2 NP significantly decreases, indicating there is a phase transition. The dependence of intensity at the peak (∼640 nm) of the BS spectrum on the laser power density is shown in Figure 4(e). Detailed data for the intensity of pump lasers at 0.09–0.11 mW/μm2 are shown in the inset. Note that in addition to the strong absorption of VO2 in the violet laser, the ultralow phase transition threshold power density (0.099 mW/μm2) is also attributed to the Mie resonance of VO2 NP confine electromagnetic field to subwavelength scales, enhancing the laser-induced photothermal effect.

Since VO2 can be modulated at picosecond speeds, we reveal the phase transition speed of VO2 NP by simply using a chopper with repetition rates f = 50 Hz to switch the pump laser beam. Here, the intensity of the pump laser was fixed at 0.22 mW/μm2. Figure 4(f) demonstrates the all-optical switching realized by utilizing the ultralow threshold phase transition of VO2 NP. For comparison, we also have performed experiments to show how the scattering spectrum of the VO2 NPs can be modulated by the heating platform without lasers(See Supplementary Material, S8). Compared to the thermally induced phase transition, the photo-induced phase transition strategy is compact with a rapid switching speed. More importantly, we can control the phase transition of the Mie sphere at the nanoscale without affecting other devices, which gives rise to broad applications in compact optical switching in the visible band, confirmed by the electromagnetic field distribution of the VO2 NP (see Supplementary Material, 9).

The temperature changes induced by continuously pumped laser light in nanoparticles were calculated numerically based on the finite element method (COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0). We calculated the temperature inside the nanoparticles at different pumping power densities based on the Beer–Lambert law:

where, ρ = 4,340 kg/m3 and C p = 690 J/(kg K) are the material density constant and pressure heat capacity [58], respectively. We have calculated the temperature of VO2 NPs by combining the electromagnetic waves, frequency domain (ewfd) module with heat transfer in solid (ht) module. The VO2 NP with d = 270 nm on a quartz substrate was exposed to 488 nm electromagnetic waves with x-polarized. We use perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions to eliminate the reflected electromagnetic waves by the boundary. Non-uniform grids with the minimum size of 2 nm were used. The heat source term Q is equal to the absorbed light related to the incident light electromagnetic power density loss density. In Figure 5(a), we show the static temperature distribution achieved in VO2 NP under continuous wave laser excitation with a power density 0.099 mW/μm2. The temperature distribution inside the nanoparticle is almost uniform due to the nanoscale volume. Theoretically, the phase transition temperature of VO2 is around 341 K. In the actual experiment, the 0.099 mW/μm2 laser of our phase transition reaction corresponds to the internal temperature of the nanoparticles of 346 K, which satisfies the conditions for the phase transition.

Simulated laser-induced photothermal effect of VO2 NPs. (a) Static temperature distribution in the XZ plane calculated for a VO2 NP excited by using a 488 nm CW laser with a power density 0.099 mW/μm2. (b) The dependence of laser-induced photothermal temperature of VO2 NP on pump laser power density.

As a key parameter of optical switching, repeatability represents the reversibly switched times while the device has not been broken [59]. Figure 6(a) presents the repeatability of VO2 NP utilizing overlapping excitation of the pump laser with repetition rates of 20 Hz. It is easy to repeat 5 × 104 times optical modulate in a visible band using a pump laser mild intensity 0.22 mW/μm2, with a high modulation depth(∼50 %). To confirm the quality of VO2 NP after the 5 × 104 times optical laser pulse excites, we measured the BS spectra of VO2 NP, as shown in Figure 6(b). As we can see, the dark field scattering of VO2 NP did not any change after tens of thousands of laser pulse modulations, implying that VO2 NP was not destroyed by the laser. In order to highlight the improvement achieved recently with different types of VO2-based optical modulators, we compare the experimental performance as shown in Table 1 (see Supplementary Material, Table 1)

Experiment characterization the repeatability performance of the VO2 NP based modulator. (a) BS Spectral intensity variation of the IMT process of VO2 particles at 20 Hz for 5 × 104 times modulations with 0.22 mW/μm2 laser power density. (b) BS spectra before (black) and after (red) 5 × 104 times laser modulations.

3 Conclusions

In conclusion, we propose and experimentally demonstrate a scheme for dynamic control of directional scattering for a single Mie sphere by utilizing laser-induced metal-insulator transitions. By controlling the strengths of the electric and magnetic dipoles of VO2 Mie sphere under the quasi first Kerker effect condition, we can substantially increase the modulation depth in the visible band. In particular, we experimentally demonstrate using BS as a probe signal with a modulation depth of up to 57 % at 640 nm, 2.2 times that of a pure VO2 film. After 5 × 104 times switching experiments, the VO2 Mie sphere still maintains high performance. Owing to the Mie resonance of VO2 NPs electromagnetic field localization effect, the threshold power density of the VO2 modulator is only ∼0.1 mW/μm2. The method proposed here offers insights for designing visible optical modulators and developing reconfigurable optics for nanoscale optical devices.

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Zhangzhou

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. ZZ2021J11

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant No. 62305035

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant No. 2022A1515010747

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipality

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant No.2023NSCQ-MSX2201

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. 2023J01923

-

Research funding: The authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62305035), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (Grant No. 2023NSCQ-MSX2201), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2022A1515010747), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2023J01923) and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhangzhou (No. ZZ2021J11).

-

Author contributions: J.X. conceived the idea. Y.Z. and S.L. fabricated the samples. Y.Z., J.M., M.P. designed the experimental setup and performed the measurements. Y.Z., X.T., J.C., performed the simulations. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file.

References

[1] A. I. Kuznetsov, A. E. Miroshnichenko, M. L. Brongersma, Y. S. Kivshar, and B. Luk’yanchuk, “Optically resonant dielectric nanostructures,” Science, vol. 354, no. 6314, p. aag2472, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag2472.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] I. Staude and J. Schilling, “Metamaterial-inspired silicon nanophotonics,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 274–284, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2017.39.Search in Google Scholar

[3] A. I. Kuznetsov, A. E. Miroshnichenko, Y. H. Fu, J. Zhang, and B. Luk’Yanchuk, “Magnetic light,” Sci. Rep., vol. 2, no. 1, p. 492, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00492.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Y. H. Fu, A. I. Kuznetsov, A. E. Miroshnichenko, Y. F. Yu, and B. Luk’yanchuk, “Directional visible light scattering by silicon nanoparticles,” Nat. Commun., vol. 4, no. 1, p. 1527, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2538.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] A. García-Etxarri, et al.., “Strong magnetic response of submicron silicon particles in the infrared,” Opt. Express, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 4815–4826, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.19.004815.Search in Google Scholar

[6] C. Tserkezis, P. Gonçalves, C. Wolff, F. Todisco, K. Busch, and N. A. Mortensen, “Mie excitons: understanding strong coupling in dielectric nanoparticles,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 98, no. 15, 2018, Art. no. 155439. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.98.155439.Search in Google Scholar

[7] M. Karimi, et al.., “Interactions of fundamental mie modes with thin epsilon-near-zero substrates,” Nano Lett., vol. 23, no. 24, pp. 11555–11561, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c03301.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] H. Huang, F. Deng, J. Xiang, S. Li, and S. Lan, “Plasmon-exciton coupling in dielectric-metal hybrid nanocavities with an embedded two-dimensional material,” Appl. Surf. Sci., vol. 542, no.15, 2021, Art. no. 148660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.148660.Search in Google Scholar

[9] J. Xiang, et al.., “Hot-electron intraband luminescence from gaas nanospheres mediated by magnetic dipole resonances,” Nano Lett., vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 4853–4859, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01724.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] C. Zhang, et al.., “Lighting up silicon nanoparticles with mie resonances,” Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 2964, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05394-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] T. Feng, Y. Xu, W. Zhang, and A. E. Miroshnichenko, “Ideal magnetic dipole scattering,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 118, no. 17, 2017, Art. no. 173901. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.118.173901.Search in Google Scholar

[12] J. Li, N. Verellen, D. Vercruysse, T. Bearda, L. Lagae, and P. Van Dorpe, “All-dielectric antenna wavelength router with bidirectional scattering of visible light,” Nano Lett., vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 4396–4403, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01519.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] M. Panmai, et al.., “All-silicon-based nano-antennas for wavelength and polarization demultiplexing,” Opt. Express, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 12344–12362, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.012344.Search in Google Scholar

[14] X. Zhu, B. Liang, W. Kan, Y. Peng, and J. Cheng, “Deep-subwavelength-scale directional sensing based on highly localized dipolar mie resonances,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 5, no. 5, 2016, Art. no. 054015. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.5.054015.Search in Google Scholar

[15] W. He, et al.., “Mie resonant scattering-based refractive index sensor using a quantum dots-doped polylactic acid nanowire,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 119, no. 11, 2021, Art. no. 111106. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0061416.Search in Google Scholar

[16] M. L. Tseng, Y. Jahani, A. Leitis, and H. Altug, “Dielectric metasurfaces enabling advanced optical biosensors,” ACS Photonics, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 47–60, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c01030.Search in Google Scholar

[17] W. Liu and Y. S. Kivshar, “Generalized kerker effects in nanophotonics and meta-optics,” Opt. Express, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 13085–13105, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.013085.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] T. Shibanuma, et al.., “Experimental demonstration of tunable directional scattering of visible light from all-dielectric asymmetric dimers,” ACS Photonics, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 489–494, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00979.Search in Google Scholar

[19] J.-M. Geffrin, et al.., “Magnetic and electric coherence in forward-and back-scattered electromagnetic waves by a single dielectric subwavelength sphere,” Nat. Commun., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 1171, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2167.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] S. Person, M. Jain, Z. Lapin, J. J. Sáenz, G. Wicks, and L. Novotny, “Demonstration of zero optical backscattering from single nanoparticles,” Nano Lett., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1806–1809, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl4005018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] R. Alaee, R. Filter, D. Lehr, F. Lederer, and C. Rockstuhl, “A generalized kerker condition for highly directive nanoantennas,” Opt. Lett., vol. 40, no. 11, pp. 2645–2648, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.40.002645.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] A. Pors, S. K. Andersen, and S. I. Bozhevolnyi, “Unidirectional scattering by nanoparticles near substrates: generalized kerker conditions,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, no. 22, pp. 28 808–828 828, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.028808.Search in Google Scholar

[23] X. M. Zhang, Q. Zhang, S. J. Zeng, Z. Z. Liu, and J.-J. Xiao, “Dual-band unidirectional forward scattering with all-dielectric hollow nanodisk in the visible,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1275–1278, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.001275.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] H. K. Shamkhi, et al.., “Transverse scattering and generalized kerker effects in all-dielectric mie-resonant metaoptics,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 122, no. 19, 2019, Art. no. 193905. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.122.193905.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] W. Liu, J. Zhang, B. Lei, H. Ma, W. Xie, and H. Hu, “Ultra-directional forward scattering by individual core-shell nanoparticles,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, no. 13, pp. 16178–16187, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.016178.Search in Google Scholar

[26] F. Qin, et al.., “Transverse kerker effect for dipole sources,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 128, no. 19, 2022, Art. no. 193901. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.128.193901.Search in Google Scholar

[27] C. Li, et al.., “Transverse scattering from nanodimers tunable with generalized cylindrical vector beams,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 17, no. 6, 2023, Art. no. 2200867. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202200867.Search in Google Scholar

[28] C. Damgaard-Carstensen, M. Thomaschewski, and S. I. Bozhevolnyi, “Electro-optic metasurface-based free-space modulators,” Nanoscale, vol. 14, no. 31, pp. 11 407–411 414, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2nr02979k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] H. Weigand, et al.., “Enhanced electro-optic modulation in resonant metasurfaces of lithium niobate,” ACS Photonics, vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 3004–3009, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.1c00935.Search in Google Scholar

[30] B. Gao, M. Ren, W. Wu, W. Cai, and J. Xu, “Electro-optic lithium niobate metasurfaces,” Sci. China: Phys., Mech. Astron., vol. 64, no. 4, 2021, Art. no. 240362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-021-1668-y.Search in Google Scholar

[31] N. A. Butakov, et al.., “Switchable plasmonic–dielectric resonators with metal–insulator transitions,” ACS Photonics, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 371–377, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00334.Search in Google Scholar

[32] J. Zhang, R. Zhang, and Y. Wang, “Vo2-like thermo-optical switching effect in one-dimensional nonlinear defective photonic crystals,” J. Appl. Phys., vol. 117, no. 21, 2015, Art. no. 213101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4921873.Search in Google Scholar

[33] T. Lewi, H. A. Evans, N. A. Butakov, and J. A. Schuller, “Ultrawide thermo-optic tuning of pbte meta-atoms,” Nano Lett., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 3940–3945, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01529.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] F. Shen, et al.., “Tunable kerker scattering in a self-coupled polaritonic metasurface,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 18, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 2300584. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202300584.Search in Google Scholar

[35] W. Yoshiki and T. Tanabe, “All-optical switching using kerr effect in a silica toroid microcavity,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, no. 20, pp. 24332–24341, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.024332.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] H. Lu, X. Liu, L. Wang, Y. Gong, and D. Mao, “Ultrafast all-optical switching in nanoplasmonic waveguide with kerr nonlinear resonator,” Opt. Express, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 2910–2915, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.19.002910.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] X. Hu, P. Jiang, C. Ding, H. Yang, and Q. Gong, “Picosecond and low-power all-optical switching based on an organic photonic-bandgap microcavity,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 185–189, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2007.299.Search in Google Scholar

[38] J. Xiang, J. Chen, Q. Dai, S. Tie, S. Lan, and A. E. Miroshnichenko, “Modifying mie resonances and carrier dynamics of silicon nanoparticles by dense electron-hole plasmas,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 13, no. 1, 2020, Art. no. 014003. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.13.014003.Search in Google Scholar

[39] M. R. Shcherbakov, et al.., “Ultrafast all-optical tuning of direct-gap semiconductor metasurfaces,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00019-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] M. R. Shcherbakov, et al.., “Ultrafast all-optical switching with magnetic resonances in nonlinear dielectric nanostructures,” Nano Lett., vol. 15, no. 10, pp. 6985–6990, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02989.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] M. Wuttig and N. Yamada, “Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage,” Nat. Mater., vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 824–832, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] P. Li, et al.., “Reversible optical switching of highly confined phonon–polaritons with an ultrathin phase-change material,” Nat. Mater., vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 870–875, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4649.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] D. Y. Lei, K. Appavoo, F. Ligmajer, Y. Sonnefraud, R. F. HaglundJr, and S. A. Maier, “Optically-triggered nanoscale memory effect in a hybrid plasmonic-phase changing nanostructure,” ACS Photonics, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 1306–1313, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.5b00249.Search in Google Scholar

[44] M. R. M. Hashemi, S.-H. Yang, T. Wang, N. Sepúlveda, and M. Jarrahi, “Electronically-controlled beam-steering through vanadium dioxide metasurfaces,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, Art. no. 35439. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35439.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] M. Qazilbash, et al.., “Infrared spectroscopy and nano-imaging of the insulator-to-metal transition in vanadium dioxide,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 79, no. 7, 2009, Art. no. 075107. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.79.075107.Search in Google Scholar

[46] M. J. Dicken, et al.., “Frequency tunable near-infrared metamaterials based on vo 2 phase transition,” Opt. Express, vol. 17, no. 20, pp. 18330–18339, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.17.018330.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] O. L. Muskens, et al.., “Antenna-assisted picosecond control of nanoscale phase transition in vanadium dioxide,” Light: Sci. Appl., vol. 5, no. 10, pp. e16 173, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.173.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] D. Y. Lei, K. Appavoo, Y. Sonnefraud, R. F. HaglundJr, and S. A. Maier, “Single-particle plasmon resonance spectroscopy of phase transition in vanadium dioxide,” Opt. Lett., vol. 35, no. 23, pp. 3988–3990, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.35.003988.Search in Google Scholar

[49] U. Zywietz, A. B. Evlyukhin, C. Reinhardt, and B. N. Chichkov, “Laser printing of silicon nanoparticles with resonant optical electric and magnetic responses,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, no. 1, p. 3402, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4402.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Y. Nagasaki, T. Kohno, K. Bando, H. Takase, K. Fujita, and J. Takahara, “Adaptive printing using vo2 optical antennas with subwavelength resolution,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 115, no. 16, p. 161105, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5109460.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Z. Wang, et al.., “Femtosecond laser-induced phase transition in vo 2 films,” Opt. Express, vol. 30, no. 26, pp. 47 421–447 429, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.477910.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] D. Wegkamp and J. Stähler, “Ultrafast dynamics during the photoinduced phase transition in vo2,” Prog. Surf. Sci., vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 464–502, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progsurf.2015.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

[53] C. Wan, et al.., “On the optical properties of thin-film vanadium dioxide from the visible to the far infrared,” Ann. Phys., vol. 531, no. 10, 2019, Art. no. 1900188. https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.201900188.Search in Google Scholar

[54] M. Currie, M. A. Mastro, and V. D. Wheeler, “Characterizing the tunable refractive index of vanadium dioxide,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 1697–1707, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.7.001697.Search in Google Scholar

[55] M. Chen, M. Kim, A. M. Wong, and G. V. Eleftheriades, “Huygens’ metasurfaces from microwaves to optics: a review,” Nanophotonics, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 1207–1231, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2017-0117.Search in Google Scholar

[56] A. B. Evlyukhin, T. Fischer, C. Reinhardt, and B. N. Chichkov, “Optical theorem and multipole scattering of light by arbitrarily shaped nanoparticles,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 94, no. 20, 2016, Art. no. 205434. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.94.205434.Search in Google Scholar

[57] P. D. Terekhov, K. V. Baryshnikova, Y. A. Artemyev, A. Karabchevsky, A. S. Shalin, and A. B. Evlyukhin, “Multipolar response of nonspherical silicon nanoparticles in the visible and near-infrared spectral ranges,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 96, no. 3, 2017, Art. no. 035443. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.96.035443.Search in Google Scholar

[58] E. Freeman, et al.., “Characterization and modeling of metal-insulator transition (mit) based tunnel junctions,” in 70th Device Research Conference, IEEE, 2012, pp. 243–244.10.1109/DRC.2012.6257012Search in Google Scholar

[59] F. Neubrech, X. Duan, and N. Liu, “Dynamic plasmonic color generation enabled by functional materials,” Sci. Adv., vol. 6, no. 36, p. eabc2709, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc2709.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2024-0154).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Large-scale photonic inverse design: computational challenges and breakthroughs

- Research Articles

- Ultra-sensitive, graphene metasurface sensor integrated with the nonradiative anapole mode for detecting and differentiating two preservatives

- Highly sensitive volumetric single-molecule imaging

- Dynamic control of the directional scattering of single Mie particle by laser induced metal insulator transitions

- Free electrons spin-dependent Kapitza–Dirac effect in two-dimensional triangular optical lattice

- Simultaneous thermal camouflage and radiative cooling for ultrahigh-temperature objects using inversely designed hierarchical metamaterial

- Photonic Dirac waveguide in inhomogeneous spoof surface plasmonic metasurfaces

- Demultiplexing-free ultra-compact WDM-compatible multimode optical switch assisted by mode exchanger

- Flat lens–based subwavelength focusing and scanning enabled by Fourier translation

- Experimental observation of spin Hall effect of light using compact weak measurements

- Opto-intelligence spectrometer using diffractive neural networks

- Inverse design of color routers in CMOS image sensors: toward minimizing interpixel crosstalk

- Dual-band complex-amplitude metasurface empowered high security cryptography with ultra-massive encodable patterns

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Large-scale photonic inverse design: computational challenges and breakthroughs

- Research Articles

- Ultra-sensitive, graphene metasurface sensor integrated with the nonradiative anapole mode for detecting and differentiating two preservatives

- Highly sensitive volumetric single-molecule imaging

- Dynamic control of the directional scattering of single Mie particle by laser induced metal insulator transitions

- Free electrons spin-dependent Kapitza–Dirac effect in two-dimensional triangular optical lattice

- Simultaneous thermal camouflage and radiative cooling for ultrahigh-temperature objects using inversely designed hierarchical metamaterial

- Photonic Dirac waveguide in inhomogeneous spoof surface plasmonic metasurfaces

- Demultiplexing-free ultra-compact WDM-compatible multimode optical switch assisted by mode exchanger

- Flat lens–based subwavelength focusing and scanning enabled by Fourier translation

- Experimental observation of spin Hall effect of light using compact weak measurements

- Opto-intelligence spectrometer using diffractive neural networks

- Inverse design of color routers in CMOS image sensors: toward minimizing interpixel crosstalk

- Dual-band complex-amplitude metasurface empowered high security cryptography with ultra-massive encodable patterns