Abstract

Our ancestors once said, “A person who does not know his history is like a monkey lost in the forest.” In the framework of this work, it was intended to study the historical development of the Silk Road and the characteristics of trade during the Mongol Empire in comparison with the principles of modern trade. According to the findings, ancient nations traded with each other to satisfy their unlimited needs with limited resources and laid the foundations of the Silk Road. On the other hand, the country that dominated the road became the most powerful country at that time, fighting with each other through geopolitical policies to maintain its influence in the area along this road. It can be said that the idea of logistics supply chain and the concept of free trade was created during the time of the powerful Mongolian empire, one of the strongest empire in the history of Mongolia as well as the world.

1 Introduction

The first records of trade relations in human history comes from ancient time. According to Sharavsambuu (2021, 35) we can determine that the trade history of Mongolia begins with the establishment of the first state in Asia.

As a carrier of national culture, trade is one of the most accurate indicators of material life and the cultural level of any civilization. Furthermore, there are dozens of researches on the life and cultural heritage of the civilization of that time based on the characteristics of the goods transported during the ancient Silk Road.

Within the framework of the “Silk Road and Mongols” project, Mongolian historical researchers visited the cultural and historical monuments along the Silk Road and prepared a series of documentary films in order to clarify the role played by the Mongols in the development of the Silk Road. These short films (Delgerjargal 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d, 2020e, 2020f) has played important role in understanding and public awareness of the historical and cultural monuments related to the history of Mongolia along the Silk Road.

An international network of trade routes linking Eurasia, known as the Silk Road, played a major role in the world history, especially for the nomads of Mongolia and other Eurasian countries. The rise of the Silk Road to its peak definitely involves Mongol Empire (Delgerjargal 2020a).

In addition, there are some other scholarly texts about the relationship between the Silk Road and trade of the Mongolian Empire are available, such as “Brief History of Mongolia” by famous Mongolian historian and former state minister Amar (1989) and the series “History of Mongolia” published by the Institute of History of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences and other historical sources.

However, studies about the contribution of the Silk Road in the history of Mongolian trade is rare to find. Although I am not a historian, based on the sources of Mongolian history, I have studied the historical development of the ancient Silk Road, and the features of trade during the Mongolian Empire in comparison with modern trade concepts, and certain conclusions were reached.

2 Historical Development of the Silk Road

According to the research works, the establishment of the Silk Road has begun as a result of the subtle tactics of the ancient Chinese Han Empire and the Mongolian Hunnu Empire. It shows the essence of modern logistics.

Animal husbandry and hunting played a major role in the economy of the Hunnu, and the Chinese who came and settled in various ways from the Han empire engaged in agriculture on a small scale. Therefore, livestock, meat, dairy products, leather and fur products produced from animal husbandry and hunting exceeded from their consumption, but there is a large shortage of agricultural and residential handicraft products (Sharavsambuu 2021, 37). The fact that the people of the Hunnu’s prioritized trade with ancient China, East Turkestan, and Central Asia in order to sell products that were surplus to their own consumption and obtain other necessary products demonstrates that the foundation for the development of barter trade was laid.

On the other hand, The Han empire had many agricultural and handicraft products, but there was a shortage of military horses, plow oxen, camels, and as well as livestock, meat, and leather, so both the Hunnu and the Han citizens were interested in mutual trade. However, in most cases, the Han authorities forbade trade between the two countries, and even if they allowed it, they were unable to conduct sufficient trade, so the Hunnus attacked and looted and fought in the border areas of the Han, and as a result, they allowed the temporary opening of border trade.

However, during the border trade, the Han state found that it was able to increase its profits by selling its own goods at a higher price and buying the raw materials of the Hunnu’s cheaper, it was written down in the ancient Chinese text “Thoughts on Salt and Iron” as: “By taking things worth a lot of Hunnu’s gold with a small piece of Chinese silk, the resources of the enemy country are depleting. And so donkeys, mules, and camels flocked to the border, horses and spotted horses became our livestock, and sables, marmots, foxes, badgers, felts, and quilts entered our domestic treasury, and jade, coral, and crystal became our treasures” (Ishjamts 2004, 233).

Han merchants secretly traded with the Hunnus, even though trade between them were forbidden because of its high profits. However, if thier secret trading has discovered, traders were severely punished, for example, in 121 BC, 500 Chinese traders were executed for this matter, according to research papers.

According to the above situation, to satisfy their unlimited needs with limited resources, the ancient countries traded with each other by doing so they layed the foundations of the Silk Road, and to maintain their influence in the areas along this road, both empires fought wars and fights.

In addition, it was recorded in history that the Hunnus conquered the settled city-states of East Turkestan, which were neighboring to the west, and collected agricultural, handicraft, and other products from them as taxes and traded with them. For example, some of the textiles found in the tomb of Noyon Mountain in Mongolia were Greco-Bactrian, and they entered the Hunnu land through East Turkestan, and coral and crystal were bought by the Hunnus from Greco-Bactria, Central Asia, and East Turkestan and traded in the Han empire (Ishjamts 2004, 234).

The Hunnu empire controlled the middle part of the Silk Road connecting the East and the West, especially the northern branch of the Eastern Silk Road, which allowed them to acquire agriculture, handicrafts, and other products of settled civilization from the West and East.

The “Silk Road” started from Chang’an (Xi’an), the capital of the ancient Chinese Han Empire, and continued through the cities of Gansu province (Lanzhou-capital city) and Xinjiang, passing through Central Asian countries and reaching India, Persia, Arabia, the Mediterranean Sea, Rome, and France.

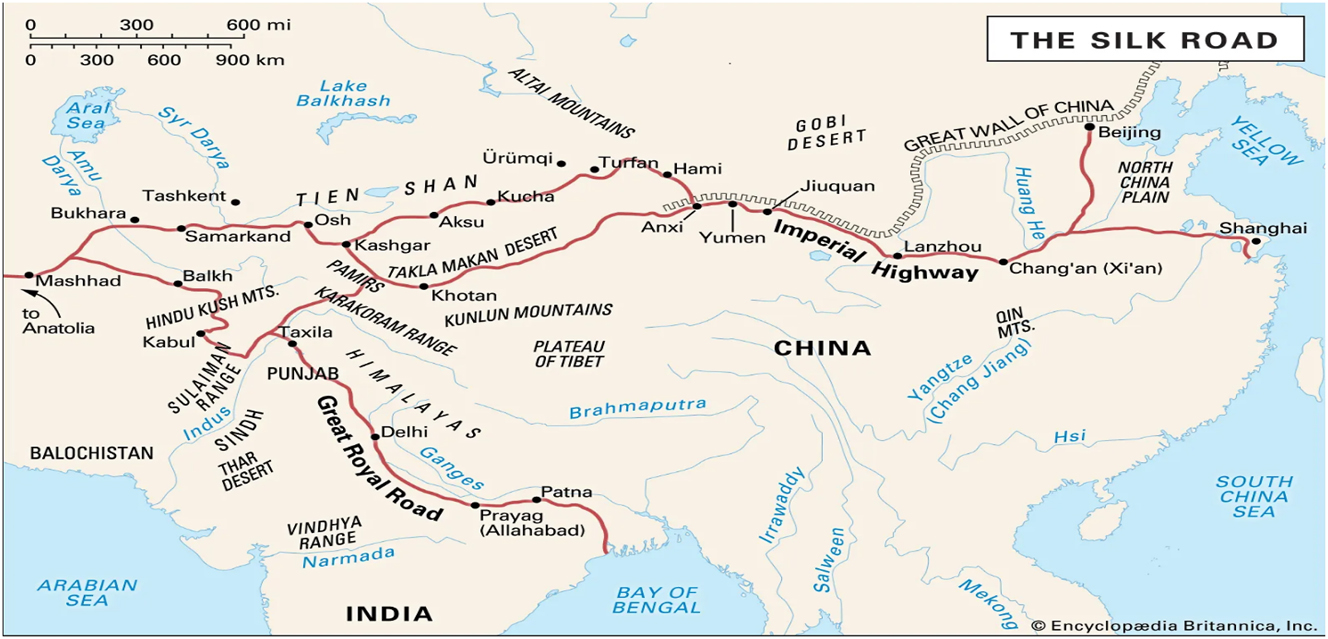

According to scientist S.I Rudenko’s note, in the 1st–2nd centuries BC, the Silk Road passed through Hami, Turfan, Urumchi, Iron Lake (Issyk-Kul), Ferghana, Sogd to Bactria, passing through Mevre, and Hamadan through Dura-Gerank and Pamir and directed towards the west, and it was recorded that ancient Greek and Roman goods entered ancient China and the Hunnus through this route (Rudenko 1962, 203) (Figure 1).

The Silk Road. Source: The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2021).

As written in the research papers, the Silk Road was called the Camel Caravan Road, the Great Trade Road, the Sapphire Road, and the Dharmaaradnaa Road in the Indian scriptures, depending on the goods that were transported on that road. As the Silk Road exited the Gansu corridor into Xinjiang, it split into three main routes: southern, central, and northern.

Furthermore, it is written in the sources that the northern branch of the road passing through Dunhuang, Turfan, and Urumchi was called the “Mongol Road” when the Mongolians were strong.

The activity of the Silk Road faded for some period of time, especially during the fall of the Roman Empire, but it is said to have revived in the 13th and 14th centuries. In other words, the Silk Road, which was on the verge of fading away, regained its control by the Mongol Empire and was used as the main route for the development of trade and relations between Eastern countries.

3 Trade during the Mongol Empire

Although the ancient Mongolian provinces had trade relations with eastern countries, many historical sources show that as a result of the establishment of the Mongolian Empire, trade envoys were sent to the neighboring countries to negotiate agreements and deepened the relations. According to Kovács and Vér (2021) traffic in goods, faiths, ideas, and people was always dependent on powerplay and geopolitics.

It is clear that the Silk Road played an important role in the expansion of the empire’s trade and trade relations with other countries in the West and East in its vast territory, which united many nomadic tribes. According to Weatherford (2018) the Silk Road reached its historic and economic apogee under the Mongol Empire (1207–1368), as a direct result of the policies of Chinggis Khan and his successors. On other hand, the Mongol Empire’s trade plays a significant role and influence in the history of the Silk Roads (UNESCO 1988b). Because of Chinggis Khan and his successors established and ruled the largest contiguous empire in world history (Biran, Brack, and Fiaschetti 2020).

In addition, it is recorded in history that the Mongols occupied almost the entire Asian continent, took sole control of the Silk Road, made the road safe, lowered the price of goods, and thus allowed international trade to flourish (Delgerjargal 2020b). In particularly, Chinggis Khan protected and controlled the Silk Road, which allowed traders to trade freely and quickly. As a result, the blockage of economic and cultural relations between the West and the East was removed. But the forts and walls that stood in front of them were destroyed. It was noted that the group of merchants who took over the trade from China, Turks, Mongolia, and the Pacific Ocean enjoyed being under the patronage of Chinggis Khan, and it was obvious that they believed it would be beneficial for them to have the Silk Road under the control of one person.

Chinggis Khan’s Yasa[1] (Mongolian: Ikh Zasag law) states that “the caravan of merchant ships passing through Mongolian territory cannot be attacked, even if they belong to a foreign enemy country”, and by inviting those merchants to visit their palaces, they “gather information” by listening to all the events happening around the world. Merchants from all over the world were protected by soldiers when they were passing through Mongolian territory, and they were supported by being invited to the palace and selling their products at higher prices (Byanbadrakh 2012). According to this, it can be explained that, by studying the market, demand and supply situation, such as entrepreneurship, production, consumption, interest, etc. of the foreign countries through the traders, they also conducted economic diplomatic activities and regulated world trade.

Venetian merchant explorer Marco Polo (1254–1324) was the first European who traveled through the Silk Road route to China. He met with Kublai Khan and wrote many beautiful notes (Polo 1987) about the wealth and life of the East, which is famous not only in Europe but also in the world. His notes are said to have been read by the great geographical discoverer Christopher Columbus when he crossed the Atlantic Ocean. The note is called “Book of the Marvels of the World” (later known in English as The Travels of Marco Polo) and the term “Silk Road” is not used in the note, but it is mentioned that Kharkhorin in Mongolia was the central trade route of Asia. Researchers believe that German geographer and traveler Ferdinand von Richthofen first used the term Silk Road in his work “China” in 1877, according to Mark (2018) Ferdinand von Richthofen designated them ‘Seidenstrasse’ (Silk Road) or ‘Seidenstrassen’ (silk routes). Both of these people were recorded as traveling along the route and transporting goods eastward.

During the time of the Mongol Empire, foreign policy and its procedures were steadily developed by sending envoys with special stamps to foreign countries, receiving foreign envoys, and negotiating treaties.

In 1218, Chinggis Khan sent his trade ambassador[2] to Khorezm, which was one of the largest power in Central Asia at that time, as well as the center of trade between the West, East, North, and South, in order to “conclude a peace treaty and expand trade with neighbors”. However, due to the execution of Chinggis Khan’s ambassadors by the Khorezm king, he fought with Khorezm and captured the empire, taking control of the Central Asian trade network, and this led Mongol Empire to becoming the trade center of that time, according to scholars such as J. Weatherford. From this, ambassadors played an important role in trade relations, and in some cases, through them, double intelligence was carried out and the situation of the country was monitored.

Furthermore, there are some other sources that described Chinggis Khan’s invasion of Khorezm as having the goal of capturing the Central Asian Silk Road. Otherwise, whoever controlled the Silk Road would have had a geopolitical advantage.

It was mentioned in Marco Polo’s work (Polo 1987) that Chinggis Khan invited western merchants to his house, and the goods they brought were evaluated by 20 scholars with high trade knowledge, and the trade was mutually beneficial for the parties. As he fully believes that our merchants can bring gold-studded clothes and fine goods and trade with great profit, so our military leaders should train their boys well in archery, horsemanship, and hand-to-hand combat. It is said that they were taught to be brave and sincere like hard-working traders who know the art of winning, which indicates that the traders of that time had a high level of knowledge about the market, demand, and supply that we are talking about today. Also, it can be seen that Chinggis Khan was able to use people with high commercial knowledge and ingenuity when implementing trade and economic relations policies.

Khorezm was located at the main hub of the Silk Road along the Amu Darya and western Turkestan, which certainly made it more attractive to traders. Also, in Marco Polo’s writings (Polo 1987), he said that there were many cruel people in the places along the road, and they would rob and kill unarmed ordinary merchants. The Chinggis Khan stopped and created a guard, so that the merchants could go safely at night. It can be concluded that Chinggis Khan took control of the Silk Road and ensured the security of merchants, which contributed significantly to the expansion of trade relations between the West and the East. In addition, this situation is recorded in world history as “Pax Mongolica.” The Pax Mongolica, Latin for “Mongol peace,” describes a period of relative stability in Eurasia under the Mongol Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries. The Pax Mongolica brought a period of stability among the people who lived in the conquered territory (National Geographic Society 2022).

However, there are many records of the Mongols minting coins and using them for trading since the time of the Hunnu, Tureg, and Uighur dynasties. Upon establishing the unified Mongol Empire, Chinggis Khan introduced gold and silver coins called Sukhes and later, in the year of 1227, introduced the first paper money/banknote/into circulation. This proves that Chinggis Khan effectively used the role of trade and money exchanges when holding the nation’s political, economic, and cultural systems under strong centralized power (Mongolbank 2020).

After the death of Chinggis Khan, his successors expanded and developed the trade of the empire. For example, during the reign of Ogodei Khan, merchants, especially Muslim merchants, came to the palace, and Ogodei Khan gave them their share of capital and traded with them and from this we can see that he used to increase his profits not only by trading but also by investing.

Besides, Ogodei Khan established the rule[3] on the amount of taxes to be collected from the people of the occupied countries to the royal fund, such as, 1/30 percent of the revenue from the customs tax was collected from the commercial items, and 1 lan was collected from the every 40 gin of alcohol (Natsagdorj and Dalai 2004, 166). It confirmed that “there is a tax under the existence of the state, and there is a state under the tax”. In addition, it contains the idea of setting the current customs tax as a percentage of the total price (ad valorem tariff) and excise duties on alcoholic beverages.

Ogodei Khan made the Mongol Empire the largest contiguous land empire in history (UNESCO 1988b). According to historical sources, to ensure the safety of traders on the Silk Road, King Ogodei deployed soldiers along the road, planted trees on both sides of the road to provide shade, and introduced standard weights and measures.

Plano Carpini, the first Western envoy who delivered the Pope’s letter to Guegue Khan, wrote that the rich people of Mongol would be brought rice and flour from the south, and the poor would receive it in exchange for skins and sheep. It is written that he would bring silk cloth with gold from countries such as Nankhiad and Persia, as well as valuable animal fur from Russia, Bulgaria, Bashkir, Hungary, Khirgis, and other countries (Amar 1989). According to this, trade relations with many countries were continued at that time, and barter trade was further developed.

During the reign of Munkh Khan, tax procedures were organized, and some taxes were amortized and exempted.

Kublai Khan is noted in history for protecting the independence of Great Mongol nation and preserving culture of Mongols. He expanded the Silk Road, which only reached Istanbul by land, to Europe by sea. He established an extensive Maritime Silk Road, with Chinese vessels plying for trade across the Indian Ocean, and thence to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea (Pirie 2019). Perhaps, China’s coastal cities of Guangzhou and Xinjiang can be thought of as 13th-century global free trade zones.

From today’s point of view, Chinggis Khan and his successors used the Silk Road to lay the foundations of the trade supply chain and postal communication connecting the West and the East, saving logistics costs (Otgonsaikhan and Narantuya 2006), organized the disjointed cities along the Silk Road into history’s largest free trade zone (Carl 2017) and creating the foundation for a free trade agreement (area) involving many countries and global trade, and brought the countries closer together. It could be called the medieval World Trade Organization system.

Many scientists are doing research on the Silk Road, and UNESCO has established an international network of the Silk Road Program to ensure the full participation of member states and other relevant parties, and the Silk Road Map (UNESCO 1988a) is shown below (Figure 2).

Silk Road on today’s map. Source: UNESCO (1988a).

4 Conclusions

In order to satisfy their unlimited needs with limited resources, the ancient countries traded with each other, thus laying the foundations of the Silk Road, and waged wars and fights among between them to maintain their influence on the lands along this road.

According to historical sources, during the Hunnu and Mongolian empires, when the Mongolians controlled the main nodes of the Silk Road, they made a significant contribution to the development of the general agreement on tariffs and trade system and international trade.

Especially during the eras of Mongol Empire, international trade flourished, and it can be said that the foundations of logistics supply chain and free trade were laid. It was also considered that the following activities contributed to the historical development of the industry. It includes:

Certain powers were given to merchants in the role of diplomats and confirmed by royal treaties, which contributed to the emergence and development of the diplomatic service;

Ensuring economic security;

Trade, customs, and excise duties were collected;

Standard weights and measures began to be used in trade;

Used many trade methods and forms such as barter, re-export, export, import, trade related investment;

The first paper currency was printed and used in circulation, which shows that money was used wisely.

Many research sources prove that Chinggis Khan’s control over the main hubs of the Silk Road made the Mongol Empire a major trade center connecting the West and the East, and his trade policy laid the foundation for trade liberalization and globalization. In addition, during the empire, the basic principles of establishment of free trade agreements and free trade zones were created. In addition, it can be seen from the sources that the foreign trade protection policy was implemented.

Merchants were supported, and through them, they conducted profitable trade and fixed the prices of goods, and by considering this, trade was considered a profession, and therefore it is clear that the activities like training, practical programs, internships for traders were carried out.

In the future, it is necessary to deeply study the Silk Road’s roles and performance in today’s trade, the characteristics of the empire, and other historical routes.

Finally, it is important for Mongolians to actively participate and contribute to the research projects of international organizations such as WTO and UNESCO regarding the Silk Road.

References

English

Biran, M., J. Brack, and F. Fiaschetti. 2020. Along the Silk Roads in Mongol Eurasia: Generals, Merchants, and Intellectuals. JSTOR, 1st ed. California: University of California Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv125jrx5 (accessed August 23, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Carl, B. 2017. “The Laws of Genghis Khan.” Law and Business Review of the Americas 18 (2): 147.Search in Google Scholar

Mark, J. J. 2018. “Silk Road.” In World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Silk_Road (accessed August 26, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Kovács, S., and M. Vér. 2021. “Mongols and the Silk Roads: An Overview.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 74 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1556/062.2021.00009.Search in Google Scholar

Pirie, M. 2019. “Kublai Khan – International Trader.” Adam Smith Institute. February 18, 2019. https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/kublai-khan-international-trader (accessed August 31, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Mongolbank. 2020. “History of Mongolian Currency.” History of Mongolian Currency. 2020. https://www.mongolbank.mn/en/p/1390 (accessed August 31, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

National Geographic Society. 2022. “The Pax Mongolica | National Geographic Society.” Education.nationalgeographic.org. May 20, 2022. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/pax-mongolica (accessed August 31, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. 2021. “Silk Road | Facts, History, & Map.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Silk-Road-trade-route (accessed September 18, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 1988a. “Interactive Map of the Cities along the Silk Roads.” UNESCO. UNESCO. 1988. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/silkroad-interactive-map (accessed August 30, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 1988b. “Mongolia | Silk Roads Programme.” En.unesco.org. 1988. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/countries-alongside-silk-road-routes/mongolia (accessed August 30, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Weatherford, J. 2018. “The Silk Route from Land to Sea.” Humanities 7 (2): 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020032.Search in Google Scholar

Mongolian

Amar, A. 1989. Brief History of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar: State Printing Factory.Search in Google Scholar

Byanbadrakh, C. 2012. “About Mongolian History.” In Directory of Mongolia, 259–85. Ulaanbaatar: Munkhiin useg print LLC.Search in Google Scholar

Delgerjargal, P. 2020a. “Silk Road and Mongols: #1 Lanzhou City.” Silk Road Research Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGdtzqFbOxU (accessed September 22, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Delgerjargal, P. 2020b. “Silk Road and Mongols: #2. Liupanshan.” Youtube. Silk Road Research Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SSDVIaQHg24&t=67s (accessed September 22, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Delgerjargal, P. 2020c. “Silk Road and Mongols: #3. Dunhuang City.” Silk Road Research Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OScw04lytOY&t=241s (accessed September 22, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Delgerjargal, P. 2020d. “Silk Road and Mongols: #4. Hami City.” Silk Road Research Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmozxSyqtPE&t=1067s (accessed September 22, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Delgerjargal, P. 2020e. “Silk Road and Mongols: #5. Turfan City.” Silk Road Research Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iKAGPj5OGUg (accessed September 22, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Delgerjargal, P. 2020f. “Silk Road and Mongols: #6. Urumchi City.” Silk Road Research Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yZIXj4Dl3w0&t=423s (accessed September 22, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Ishjamts, N. 2004. “Hunnu Empire.” In History of Mongolia, Vol. 1, edited by D. Tseveendorj, 183–246. Ulaanbaatar: Admon Print LLC.Search in Google Scholar

Natsagdorj, S., and C. Dalai. 2004. “The Establishment of the Mongol Empire.” In History of Mongolia, Vol. 2, edited by T. Ishdorj and C. Dalai, 43–134. Ulaanbaatar: Admon Print LLC.Search in Google Scholar

Otgonsaikhan, N., and D. Narantuya. 2006. “Silk Road and International Trade.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on History of Mongolian Economic Mindset: Traditions, Reforms-I, 81–92. Ulaanbaatar: Admon Print LLC.Search in Google Scholar

Polo, M. 1987. Book of the Marvels of the World. Translated by B. Dorj, A. Ochir, and S. Idshinnorov. Ulaanbaatar: State Printing Factory.Search in Google Scholar

Sharavsambuu, B. 2021. Lessons from Mongolian Trade History. Ulaanbaatar: Ochirpress Printing.Search in Google Scholar

Russian

Rudenko, S. I. 1962. Culture of Hunnu and Noin Ulin Mounds. Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Eurasian-Mongolian Research Center

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Language-History-Culture of Mongolia and Korea on the Issue of Affiliation

- The Lineage of Spiritual Succession of the First Bogd Gegen of Mongolia Zanabazar (1634–1723) in His Secret Namtar and on the Thangka

- Princesses of the Central Plains Married into the Turkish Khaganate

- A Comparative Study of the Military Tactics of the Mongol Empire and Goguryeo Kingdom (Goryeo)

- Silk Road and Trade of the Mongol Empire

- The Tuvan Shamanism and Its Features

- An Establishment of Ulaanbaatar as a Buddhist Settlement

- Tax Policy Implemented in Mongolia by the Manchus

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Language-History-Culture of Mongolia and Korea on the Issue of Affiliation

- The Lineage of Spiritual Succession of the First Bogd Gegen of Mongolia Zanabazar (1634–1723) in His Secret Namtar and on the Thangka

- Princesses of the Central Plains Married into the Turkish Khaganate

- A Comparative Study of the Military Tactics of the Mongol Empire and Goguryeo Kingdom (Goryeo)

- Silk Road and Trade of the Mongol Empire

- The Tuvan Shamanism and Its Features

- An Establishment of Ulaanbaatar as a Buddhist Settlement

- Tax Policy Implemented in Mongolia by the Manchus