Abstract

The data-intensive research environment and the movement towards open science create demand for information professionals with knowledge of the research process and skills in managing and curating data. This paper is reporting the findings from a multiyear study entitled “Data curator: who is s/he?” initiated by the Library Theory and Research (LTR) Section of the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA). The study aimed to identify the roles and responsibilities of data curators around the world and also focused on the terminology used to describe the new professional roles. The following questions were posed: R1: How is data curation defined by practitioners / professional working in the field? R2: What terms are used to describe the roles for professionals in data curation area? R3: What are primary roles and responsibilities of data curators? R4: What are educational qualifications and competencies required of data curators? To answer the research questions, the research team performed a comprehensive literature review and vocabulary analysis and conducted an empirical study using mixed-methods design. The study consisted of three stages: 1. Literature review and vocabulary analysis 2. Content analysis of position announcements 3. Interviews with professionals working in data curation and research data management- Findings confirm the results from previous research about the lack of common terminology and a variability of the position titles. The concept of data lifecycle highlighted the important role of data curators. However this study also found that many positions in practice were held by non library professionals. The findings indicate that data curation is an evolving sociotechnical practice that involves not only technical systems and services structured around research data life cycle but also a range of social activities around community building.

Introduction

The concept of data curation as a superordinate framework for coordinating research data management services emerged in the context of growing pressure to increase access to scientific research output and to improve the overall efficiency of the technological and human resources necessary to facilitate data creation, preservation, and reuse. ‘Data curation,’ while a relatively venerable term compared to other neologisms of the digital age (including, for example, ‘open access’ and ‘open data’), remains a new and emerging practice for many researchers, librarians, and information professionals who curate both data assets and data management programs at universities and research centers around the world. As a result, the scope of data curation as a set of sociotechnical practices, and the formal titles under which data curators typically operate, can vary considerably over time, between institutional settings, and across international borders (Tenopir et al. 2017). The motivations for the development of data curation programs are likewise diverse, often emerging from the policy environment in which research is conducted, such as funder requirements for data management planning and long-term data access, or local organizational priorities, including scholarly communication initiatives and the creation of digital repository infrastructure. Data curators, depending on their circumstances, can be involved in anything from promoting data literacies among their user communities and supporting research grant compliance among their research communities to building workflows around technical infrastructures and aiding users in their experience with that infrastructure, to direct project support for scholars struggling to manage and communicate the often immense data output their research can generate.

It’s not surprising, then, that identifying a comprehensive set of activities that define data curation as a coherent discipline can be challenging. Nearly 25 years after the term ‘data curation’ was coined, substantial opacity still surrounds what frontline data curators are actually doing for their host organizations and, more importantly, the flesh-and-blood data creators and reusers they support. Research data management (RDM) and data stewardship have emerged as additional terms to describe the activities in managing research data throughout its lifecycle. Prior studies found the lack of common vocabulary and a variability in position titles (Kim, Warga, and Moen 2013; Swan and Brown 2008). This paper seeks to shed additional light on these questions by reporting the findings from a multiyear study of data curation initiated by the Library Theory and Research (LTR) of the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA). The LTR research project, entitled “Data curator: who is s/he?”, aimed to identify the roles, responsibilities, activities, and concerns of practicing data curators around the world. The terms data curation and research data management (RDM) are used interchangeably throughout the paper to reflect the language of the study participants and differences in vocabulary across countries. Diverse vocabularies are also invoked to describe the various roles for professionals working with organizing, managing, preserving, and disseminating data. The focus of the study was on the roles and responsibilities of information professionals involved in managing, sharing, and preserving data throughout the research lifecycle and in the long-term. The main objectives of the project were:

To prepare a vocabulary (a list of terms in hierarchical structure) and possibly an ontology, using a formal representation of a set of concepts;

To understand roles and responsibilities of the data curator profile.

This study was conducted in the context of academic and research libraries. While this study presents primarily a library perspective, it also acknowledges that libraries are not the only units involved in data curation at academic institutions. Sharing, releasing, and reusing research data requires building multi-layered knowledge infrastructures and engaging multiple institutional stockholders (Borgman 2015). Information professionals, who work actively in research data management, come from a variety of backgrounds. Research Data Alliance (RDA) membership data indicate that approximately only 12 % of its international members identify as librarians (RDA: Research Data Alliance 2018).

Background: Literature Review

Data-intensive science, funder requirements for data management and data sharing, and a changing research and publishing landscape have been identified as primary factors in developing RDM services (Janke, Asher, and Keralis 2012; Pryor 2012). In 2012, Christine Borgman declared that the “data deluge” had arrived and estimated that 90 % of the world’s data had been created in the two years preceding her publication (Borgman 2012). Hey’s “fourth paradigm” of scientific discovery, based on the use of massive datasets and computing technologies, highlights the different ways of doing research and above all new modes of scholarly communication (Hey, Tansley, and Tolle 2009).

Digital curation has emerged as a new area of responsibility for researchers, librarians, and information professionals in the digital library environment (Heidorn 2011; Witt 2008). One of the most frequently cited definitions of digital curation, developed by the Digital Curation Centre (DCC), focuses on “maintaining, preserving and adding value to digital research data throughout its lifecycle” (DCC 2018). The emphasis of the model is on the cyclical nature of curation activities as well as long-term preservation and retention of data (Higgins 2008). Digital curation was identified as a new area of research and practice with an emphasis for long-term management of digital data (Higgins 2011).

The DCC model has provided a framework for aligning curation tasks with the life cycle phases (Ball 2012). In addition to DCC, Ball (2012) reviews other data and research life cycle models, such as DataONE and UK Data Archive lifecycle model. The data lifecycle models are useful tools in planning and developing data management services and in visualizing the phases in the research process (Carlson 2014). Carlson distinguishes between a broader concept of a research lifecycle and its subset - data life cycle. The two terms are used in this paper based on that distinction.

In the digital era, researchers are no longer isolated but collaborate and share their findings at different stages of the research process. The Open Science movement reflects this global trend towards cooperative work, emphasizes new ways of diffusing knowledge, and advocates sharing openly all outcomes of the scientific process (Center for Open Science n.d.; Kraker et al. 2011; Open Knowledge International n.d.). Open Data, a key component of Open Science, is believed to contribute to transparency and reproducibility of research and to the more efficient scientific process (Kraker et al. 2011; Molloy 2011). The principles of FAIR data (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) provide a foundation for access and reuse of research data across disciplines and borders (Wilkinson et al. 2016). The concept of Open Science and the FAIR data principles have been embraced by the European Commission and incorporated into the European Open Science Cloud roadmap (European Commission 2018). A recent report examines the range of data skills needed to support the implementation of FAIR principles and distinguishes between research community skills, data science, and data stewardship. Data science is focused on expertise from computer science, software development, statistics, visualization, and machine learning, while data stewardship represents a set of skills related to managing, sharing, and preserving data (Hodson et al. 2018)

The data-intensive research environment and the movement towards open science standards for research exchange create demand for information professionals with knowledge of the research process and skills in managing and curating data. The report prepared for the European Open Science Cloud points to a shortage of data experts both globally and in Europe, estimating that half a million specialists with expertise in managing data will be needed to support researchers in the European Union (Ayris et al. 2016). Academic libraries in many countries have been assuming leadership roles in changing research culture, promoting open access, and offering services in data management (Cox and Pinfield 2014; Cox et al. 2017; Tenopir et al. 2014, 2015; Yoon and Schultz 2017). Traditionally, libraries provided data services for their users by acquiring datasets and ensuring their discoverability and accessibility. The new environment has led to a transformation of data librarianship and the development of new services to actively support scholars in managing and even creating research data (Fearon et al. 2013; Heidorn 2011; Xia and Wang 2014).

Researchers note the emergent character of RDM services, especially in circumstances where roles and responsibilities of information professionals are not well defined (Corrall 2012, 2014; Heidorn 2011; Swan and Brown 2008). Swan and Brown (2008) point out the lack of common titles and make a distinction between the roles of data librarians, data managers, and data scientists. Heidorn (2011) emphasizes that “no one individual will have all the required skills” (667). While the need for educating a new class of data experts is broadly acknowledged, there is limited agreement on specific competencies, roles, and qualifications. In addition, the profile of data curators is evolving further from the reflective experience of professionals, and there is no underlying theoretical framework for the role that might guide its development in the future.

Several research studies conducted content analyses of job announcements in order to identify a set of required competencies and expected responsibilities common to professionals in digital curation, mostly in the United States (US) and Canada (Kim, Warga, and Moen 2013; McGovern 2016). Kim, Warga, and Moen (2013) analyzed 173 job advertisements posted for the academic library market and found no common vocabulary and a significant variability in position titles. The results of the study indicate that the requisite set of skills for data curators includes a combination of interpersonal talent and technology-intensive experience. In addition to communication and training competencies, qualified candidates are expected to demonstrate capacity to curate (that is, select and describe) and preserve digital content as well as use a robust and rapidly evolving toolkit of technological solutions. Xia and Wang (2014) further introduced an international perspective to literature by analyzing a set of job postings from the International Association for Social Science Information Services & Technology (IASSIST) database. The authors identified data management as the top responsibility for data librarians in social sciences. The results of the analysis also confirmed that employers value interpersonal skills as much as technical and project management skills.

Researchers also indicate that liaison and embedded librarians are often asked to reskill and assume RDM responsibilities (Cox, Verbaan, and Sen 2012; Jaguszewski and Williams 2013; Rockenbach et al. 2015). Institutional repositories (IR) play a pivotal role in stewardship of datasets, which can be used in interdisciplinary research endeavors (Witt 2008, 2012). Faniel and Connaway (2018) examine librarians’ RDM experiences, specifically the factors that influence their ability to support researchers’ needs. Findings from interviews with 36 academic library professionals in the US identify five factors of influence: (1) technical resources; (2) human resources; (3) researchers’ perceptions about the library; (4) leadership support; and (5) communication, coordination, and collaboration.

The development of RDM services and the roles of information professionals have been the subject of extensive survey research (Cox and Pinfield 2014; Cox et al. 2017; Fearon et al. 2013; Tenopir, Birch, and Allard 2012; Tenopir et al. 2015, 2017). The focus of this research was on the types of services offered by academic librarians, maturity levels, and plans for future development. The findings of the survey research indicate that academic libraries mostly offer consultative services and training, especially for data management planning. Technical services that involve maintaining a data repository and support for data archiving were limited. The initial surveys focused primarily on academic libraries in the US (Fearon et al. 2013; Tenopir, Birch, and Allard 2012; Tenopir et al. 2015) and the UK (Cox and Pinfield 2014). More recently, Tenopir et al. (2017) conducted a survey of research data services in European academic libraries. Cox et al. (2017) expanded the coverage to seven countries and provided an international comparison of several aspects of RDM development, including policy and governance, type of services, and staff deployment and skills. Both studies find that academic libraries in the surveyed countries offer advisory services and collaborate with other stakeholders within their institutions—underscoring the importance of organizational aspects of data curation.

The professional literature is mainly based on the experience and opinions of the academic library community. This study builds upon this prior research and expands it by providing an international perspective and capturing the voices of practicing data curators themselves. This multi-phase study examines the terminology, analyses position description, and focuses on the value added by the data curator in the research lifecycle.

Methodology

The main purpose of the IFLA LTR project was to identify the characteristics of roles and responsibilities of data curators and RDM professionals in the international and interdisciplinary contexts. The study also focused on the terminology used to describe the emerging practices and new professional roles. The following questions were posed for the study:

R1: How is data curation defined by practitioners/professional working in the field?

R2: What terms are used to describe the roles for professionals in data curation area?

R3: What are primary roles and responsibilities of data curators?

R4: What are educational qualifications and competencies required of data curators?

To answer the research questions, the research team performed a comprehensive literature review and conducted an empirical study using mixed-methods design. The study was conducted from September 2015 through June 2017 and consisted of three stages:

Literature review and vocabulary analysis

Content analysis of position announcements

Interviews with professionals working in data curation and research data management.

Literature research focused on the two key aspects related to the aims of the research, namely the role of the data curator and her/his competences. The initial literature review involved searching several databases and subject bibliographies in the library and information (LIS) field, notably Bailey’s Research Data Curation Bibliography (Bailey 2017). Candidate papers were identified through searches based on terms such as ‘data curation’, ‘data curator’, ‘data management’, ‘research data’ and similar. The final selection was mostly driven by subjective judgment, based on an examination of the key words and the abstracts. A hundred publications on the topic of data curation were retrieved and analyzed, while the literature review was updated in May 2017 using the updated Bailey’s bibliography, with 55 additional publications identified. The preliminary findings from this analysis were presented at the 2016 LIDA conference (Tammaro et al. 2017). The research team compiled an extensive body of literature and data comprised of the reviewed publications and the data gathered through the empirical research. This corpus was analyzed through the data mining techniques to detect patterns in the vocabulary and to answer research questions one and two (R1 and R2). Based on the subjective choice of the team, some common terms were compared with Wikidata for a final semantic analysis.

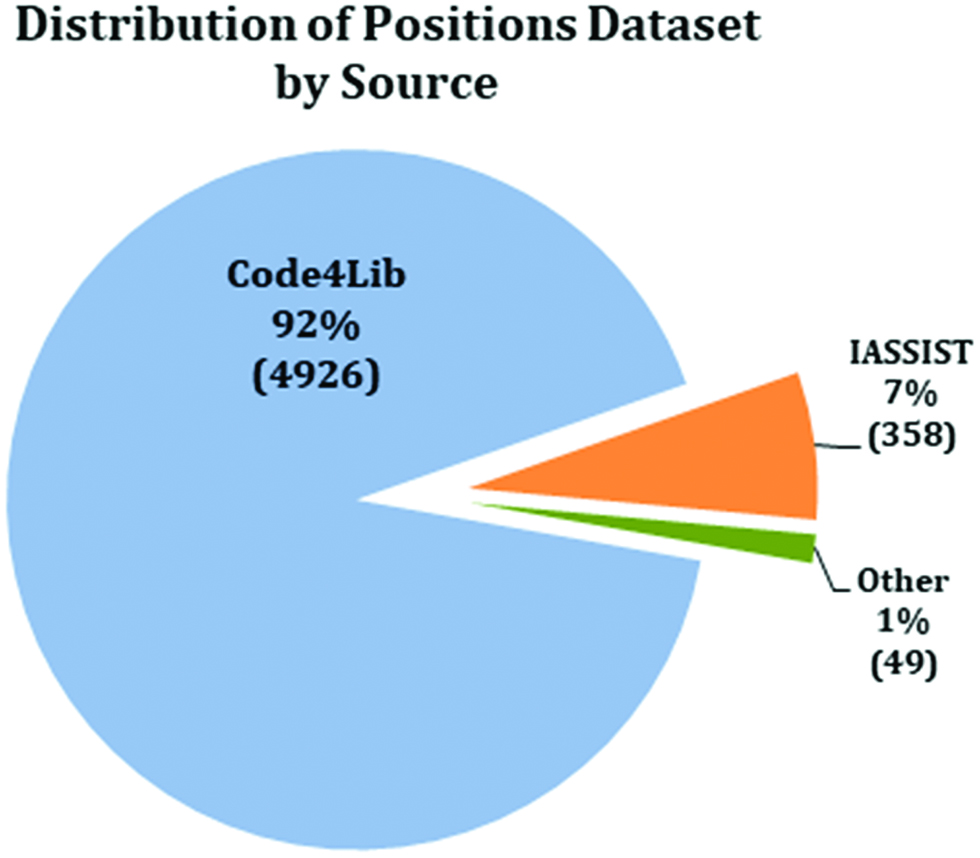

The empirical portion of this study was designed using a mixed-methods approach with a combination of quantitative and qualitative strategies (Creswell 2013). It included two phases of data collection and multiple sources of data. The first phase focused on quantitative content analysis of job announcements derived from a variety of library and information science job posting sites, including International Association for Social Science Information Services and Technology (IASSIST) and Code4Lib. IASSIST and Code4Lib provided international coverage and were the main sources of data. As Figure 1 demonstrates, a majority (more than 98 %) came from the Code4Lib and IASSIST websites.

Distribution of position announcements by source.

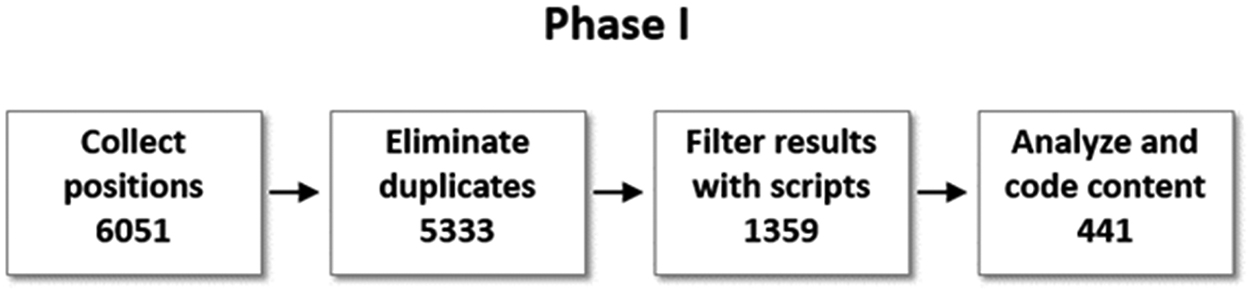

The initial data set included 6,051 job announcements. This set was then filtered to remove duplicates within and across sources and to focus on the positions in data management, data curation, and data librarianship. Figure 2 illustrates the steps in the process of selecting, filtering, and generating the data for final analysis. The final set included 441 positions, with 54 % classified as composed of “primary” data curation responsibilities and 46 % as “secondary”.

The process of selecting and filtering job announcements.

In the second phase, semi-structured interviews were conducted with professionals working as data librarians, data curators, or research data managers. The participants also were asked to fill out a brief questionnaire. Interviews and questionnaires were supplemented by documentary evidence, including reports, RDM online tutorials, and organizational websites. The goal of interviews was to gain insight into the practice of data curation and research data management and look at the roles and responsibilities from the perspective of the professionals working in the field. The initial interview participants were recruited through postings to the IFLA and Research Data Alliance (RDA) listserves. In addition, convenience and snowball sampling were used in the recruitment. Participants represented academic libraries, research centers, and research data service centers in Australia, Canada, six European countries, and the US (see Table 1 for countries represented in the sample).

Countries represented in the interview sample.

| Country | No. of Sites |

|---|---|

| Australia | 3 |

| Austria | 1 |

| Canada | 3 |

| Germany | 2 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| Sweden | 2 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| United Kingdom (UK) | 5 |

| United States (US) | 5 |

| Total | 24 |

Interviews were conducted in English with participants at 24 international sites between March 2016 and February 2017. Twenty-six professionals participated in the study (two interviews included a team of two people). The interviews were conducted over Skype, Zoom, and phone and lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

The data gathered through interviews and content analysis of job announcements provided additional data for answering research questions one and two (R1 and R2) and served as a foundation for answering research questions three and four (R3 and R4). The interview data also offered an opportunity to examine organizational structures and types of RDM services delivered at selected academic libraries and research centers in multiple countries. The preliminary findings from this portion of the study were presented at the Association for Information Science and Technology conference (Matusiak and Sposito 2017).

Findings

Vocabulary

One of the main goals of this project was to identify a set of terms (a vocabulary) and possibly an ontology related to digital curation, by analyzing relevant textual data in the field. For this purpose, six different corpora were collected:

Bibliography Old. Text (abstracts, keywords, and full text) extracted from 110 papers related to digital curation and published up to 2015.

Bibliography New. Text (abstracts, keywords, and full text) extracted from 55 papers related to digital curation and published in 2016 and 2017.

Positions/Job offers. Text extracted from 95 selected job offers and positions (mostly from academia), searching for “digital curators”.

Questionnaire. Text extracted from a set of 32 questionnaires distributed to professionals in the field.

Interviews. Text extracted from the transcript of 24 interviews with selected respondents of the questionnaires.

Edison project. Text extracted from the final four deliverables of the Edison project, a European project aiming at defining the skills and the roles of the new profession of data scientist.

The system used to extract relevant terms from the corpora, more generally called “key phrases”, is the Keyphrase Digger (KD, see http://dh.fbk.eu/technologies/kd), developed at the “Fondazione Bruno Kessler” in Trento, Italy (FBK, see http://ict.fbk.eu/). KD scans a given corpus and computes the “scores” of possible key phrases, based on term frequency measures and linguistic syntactic information (Part of Speech patterns). It then returns the key phrases in descending order of their score. The Keyphrase Digger has three main parameters:

n, the number of key phrases to be returned, in our project set to 50 for all corpora except the interviews. In this case, given the highly unstructured and colloquial text, n was set to 80 in order to try and capture more relevant key phrases.

p, which gives a boost to more specific key phrases (i. e. multi-token expressions). Depending on the value of p there will be more or less multi-token expressions in the result. It can have values NO, WEAK, MEDIUM, STRONG.

m, which indicates the maximum number of words that can be used in the multi-token expressions.

In order to extract the maximum amount of information, KD was run on each corpus several times, with different values of the p and m parameters. A first series of five runs was done, with p = WEAK and m (the maximum number of words in a key phrase) going from 1 to 5. Then the results of the five runs were merged into a single list eliminating duplicates and terms clearly not related to digital curation. It should be noted that KD does not have any ‘semantic’ knowledge, and the key phrases identified are based only on frequencies and syntactic information. Therefore, the returned list may contain key phrases not related at all to digital curation. The elimination of those terms was based on subjective ‘human’ judgement.

The same process of five runs was applied to the same corpus with p = STRONG, obtaining a second list of relevant key phrases. The two lists were finally merged into a single master, eliminating duplicate terms and obtaining the set of terms related to digital curation for that corpus.

The final results for the six corpora are summarized in Table 2. Despite the fact that KD was run with n (the number of terms to be returned) always set to 50, in the end the number of terms for each corpus is different, as a result of merging several different lists and eliminating repeated terms, and applying human judgment to eliminate terms not ‘relevant’ for digital curation.

Synopsis of terms extracted from the six corpora.

| Corpus | # terms | First five terms |

|---|---|---|

| Bibliography Old | 60 | research data management, data conservancy instance, data curation education program, data curation education, data curation profile |

| Bibliography New | 69 | research data management, research data services, data curation education, data curation profiles toolkit, big data |

| Positions/Job offers | 40 | research data curation librarian, research data management, data management librarian, research data curation, data curation |

| Questionnaire | 56 | research data management, research data officer, research data manager, research data services, research data facility manager |

| Interviews | 34 | research data management, data management, research data, data curation, better research data management services |

| Edison project | 25 | data science, data science data management, data science taxonomy, data science education, data science knowledge |

After having extracted the set of key phrases from the six different corpora, it was apparent that there was a minimal overlap between any two pairs of corpora. To verify this finding and make it more precise, the research team identified the key phrases in common between the 15 possible pairs of corpora. The results confirmed the initial observation, as the ‘intersection sets’ go from a minimum of 3 elements (for the pair Interviews-Edison) to a maximum of 18 elements (for the pair Bibliography New-Bibliography Old). The complete lists of terms extracted from the six corpora are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1314978). The result may not be surprising, if we consider that the texts in the corpora are coming from different communities, each one having its own terminology. What remains to be understood is whether the differences between the communities are just a matter of ‘terminology’, i. e. using different words to indicate (more or less) the same set of concepts, or is rather a difference in the set of concepts related to digital curation, supposing that the ‘relevance’ of a concept is actually depending on the community using it. The terms in common between any two pairs of the six key phrases lists (15 sets) are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1317577).

As a further step, the research team matched some of the common terms extracted from the corpora with WIKIDATA, obtaining the results shown in Table 3.

Common terms extracted from corpora and WIKIDATA Codes.

| Term | Definition | Related Term | WIKIDATA Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Data Management (RDM) | Activities around the life cycle of research-related data | Research Data: collection of facts produced through systematic inquiry (Q15809982) | Q30089794 |

| Data curation | Work performed to ensure meaningful and enduring access to data | Digital curation: selection, preservation, maintenance, collection, and archiving of digital assets (Q5276060) | Q15088675 |

| Data management | All disciplines related to managing data as a valuable resource | Data Management Plan (Q17085509) | Q1149776 |

| Digital preservation | Formal endeavor to ensure that digital information of continuing value remains accessible and usable | Preservation: maintenance of objects as closely as possible to their original condition also called conservation (Q1479406) | Q632897 |

| Data science | Interdisciplinary field about processes and systems to extract knowledge or insights from data | Data Scientist: a person studying and working with data (Q29169143) | Q2374463 |

Content Analysis of Job Postings

Analysis of the RDM job listings dataset focused on three of the four research questions (R2, R3, and R4) raised in this paper, with the ultimate goal of shedding light on the first question (R1), how data curation is defined as a de facto sociotechnical practice by professionals working in the field.

The challenge in using job listings as a data source to define a position from the ‘bottom up’ lies in the fact that extracting information about the roles, responsibilities, qualifications, and competencies of that position depends first on identifying which listings meet the criteria for analysis, and which do not.

In the case of data curation, this challenge is compounded for several reasons, including the emergent nature of the discipline as a whole and, especially, the wide variation in titles used locally to identify positions. Of the 5,333 job listings in the dataset, only 19 included the term “Data Curator” in the title ( < 1 %). Among these 19 positions, “Data Curator” was the most common title, with positions using either subject matter expertise or hierarchical level to further specify what the work entailed (Table 4).

Job listings with “data curator” in the title.

| Title (normalized) | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Data Curator | 12 | 63.2% |

| Scientific Data Curator | 2 | 10.5% |

| Research Data Curator | 2 | 10.5% |

| Assistant Data Curator | 1 | 5.3% |

| Humanities Data Curator | 1 | 5.3% |

| GeoSpatial Data Curator | 1 | 5.3% |

Note that the titles listed here (as well as the titles show in tables below) have been normalized to remove local idiosyncrasies, such as organization name or word order, that were semantically irrelevant to this study’s research questions. For example, “Assistant Data Curator for the 4D Nucleome Data Coordination and Integration Center” is simply identified as “Assistant Data Curator”.

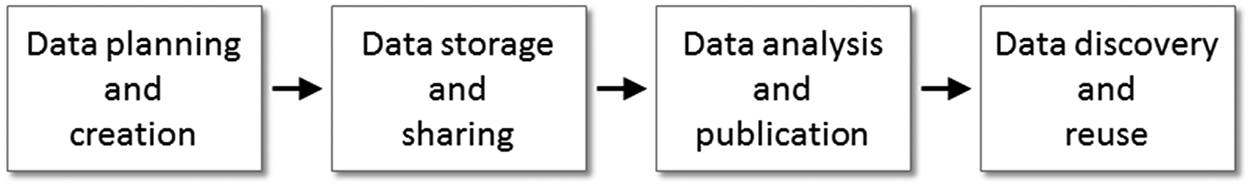

With formal job titles providing little guidance in identifying data curators, the research team approached the analysis using a simplified model of the data life cycle to frame the scope of terminology that could potentially be associated with data curation positions broadly construed (Figure 3). This model was developed during the interview phase of the project. The goal was to be as inclusive as possible, so that any position with responsibilities associated with any stage of the data life cycle could be qualitatively analyzed according to the degree of curatorial activities it required (among other tasks). This strategy resulted in the elimination of nearly 75 % of the positions in the source dataset—jobs that bore no relation whatsoever to the data life cycle (even though terms such as “data” and “curation” may have appeared in the listings for other reasons; e. g., “Collection Curator” or “Metadata Wrangler”).

Simplified model of the research data life cycle.

It also revealed a key finding from the research: data curation positions are frequently advertised under a wide variety of titles often with additional data-related responsibilities, such as data science or data references services, that not do directly constitute data curation per se. Table 5 shows the distribution of titles for positions the analysis identified as data curators according to our model.

Distribution of normalized job titles for positions that include data curatorial activities.

| Title | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Librarian - Data | 15 | 3.4 % |

| Librarian - Data Services | 13 | 2.9 % |

| Data Curator | 12 | 2.7 % |

| Librarian - Digital Scholarship | 10 | 2.3 % |

| Librarian - Digital Initiatives | 10 | 2.3 % |

| Librarian - Research Data | 8 | 1.8 % |

| Research Data Manager | 8 | 1.8 % |

| Librarian - Data Curation | 6 | 1.4 % |

| Librarian - Digital Preservation | 6 | 1.4 % |

| Digital Archivist | 6 | 1.4 % |

| Librarian - Scholarly Communications | 6 | 1.4 % |

| Research Data Specialist | 5 | 1.1 % |

| Librarian - Data Management | 5 | 1.1 % |

| Librarian - Geographic Information Systems | 5 | 1.1 % |

| Data Management Specialist | 4 | 0.9 % |

| Librarian - Social Sciences Data | 4 | 0.9 % |

| Librarian - Research Data Management | 4 | 0.9 % |

| Archivist | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Librarian - Digital Curation | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Data Manager | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Librarian - Digital Projects | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Data and Informatics Consultant | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Librarian - Research Data Services | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Data Archivist | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Research Information Scientist | 3 | 0.7 % |

| Other (255 unique titles) | 290 | 65.8 % |

Though no single title stands out as standard for the discipline, seven of the ten most common titles include librarianship in some form. Data curators are often formally working as Data Services Librarians, Digital Scholarship/Scholarly Communication Librarians, or Digital Preservationists.

The range of responsibilities assigned to data curators articulated in this dataset reflects the influence of librarianship on the role of data curation in general. Table 6 shows the distribution of activities for positions identified as data curators, regardless of title. The top four would be familiar to most librarians in any setting. But many of the positions also involve responsibilities such as scholarly communication, data science (and “statistics”), and data services (reference services for data discovery) that reach beyond the core responsibilities of data curators.

Distribution of responsibilities of data curators as expressed in job listings.

| Activities | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Instruction | 299 | 67.8 % |

| Reference | 290 | 65.8 % |

| Outreach | 270 | 61.2 % |

| Access | 258 | 58.5 % |

| Preservation | 254 | 57.6 % |

| Policy | 238 | 54.0 % |

| Data management | 208 | 47.2 % |

| System design | 187 | 42.4 % |

| Research support | 164 | 37.2 % |

| Scholarly communication | 162 | 36.7 % |

| Best practices | 137 | 31.1 % |

| Data life cycle | 115 | 26.1 % |

| Domain expertise | 115 | 26.1 % |

| Open Access | 111 | 25.2 % |

| Statistics | 102 | 23.1 % |

| Data management plans | 93 | 21.1 % |

| Rights | 81 | 18.4 % |

| Data services | 70 | 15.9 % |

| Data science | 43 | 9.8% |

It’s interesting to note, however, that a degree in librarianship was required in only 27 % of the job advertisements, a figure that is higher than any other degree category (Table 7), though low compared to the prevalence of librarianship activities required of data curators.

Distribution of degree qualifications for data curators.

| Degree | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| MLIS | 119 | 27.0 % |

| PHD | 34 | 7.7 % |

| BA/BS | 13 | 2.9 % |

The extent of data curation as an international discipline is also indicated by the dataset. Thirty-two countries across five continents contributed job listings to the analysis, with the widest distribution coming from Europe (Table 8). This distribution, however, may reflect both the uneven development of data curation as a practice around the world, and a clear selection bias in the use of North American job sites as the basis for the dataset.

Distribution of contributing countries by continent.

| Continent | Countries | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 17 | 50.0 % |

| Middle East | 5 | 14.7 % |

| Asia | 4 | 11.8 % |

| North America | 3 | 8.8 % |

| Oceana | 2 | 5.9% |

| Africa | 1 | 2.9 % |

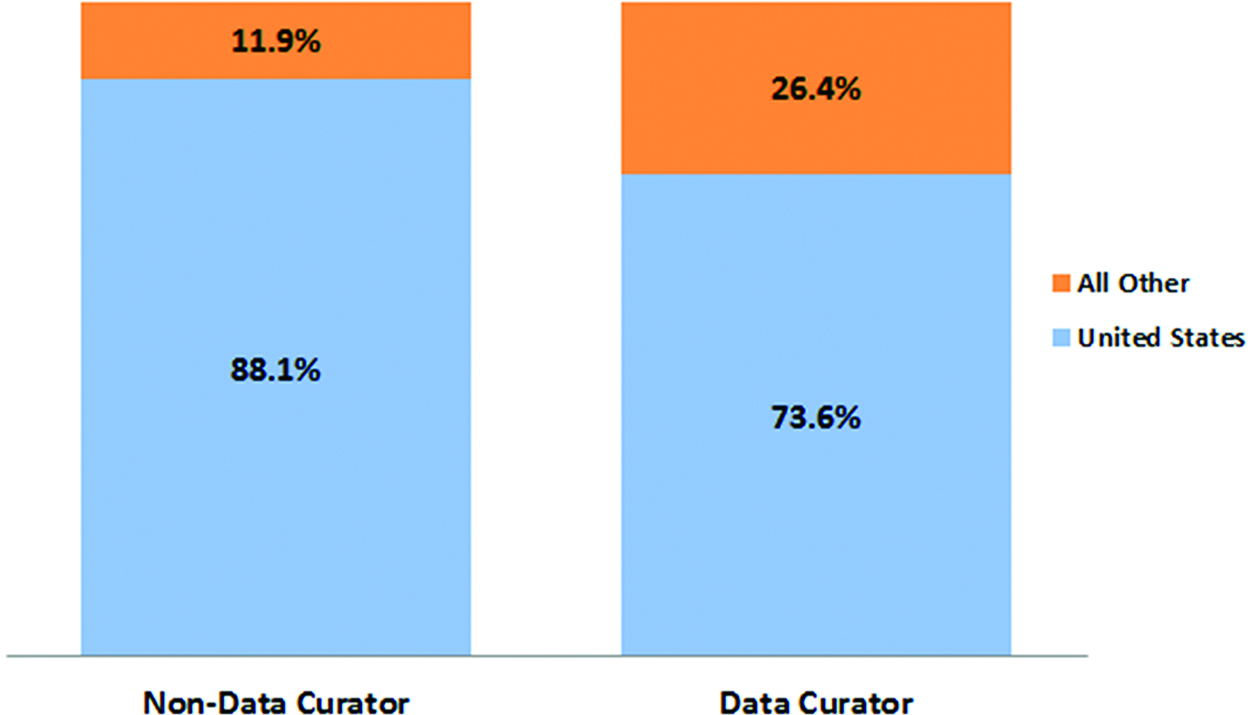

Finally, while all positions in the dataset, whether coded as data curator or non-data curator, are overwhelmingly (73.6 %) based in the US, as demonstrated in Figure 4 (again reflecting the geographic selection inherent to the source data), data curator advertisements were disproportionately more likely to come from countries other than the US as compared to non-data curator jobs. This difference may be due to several factors, including the prevalence of established research data management training centers in the US, or the uneven emergence of data curation as a sociotechnical practice worldwide.

Origin of job advertisements for data curator and non-data curator positions.

Qualitative Phase: Interviews and Questionnaires

The qualitative part of the study complements the content analysis of job postings by examining the roles and responsibilities from the perspective of professionals working in the field. In this phase, interviews served as a primary source of data and were supplemented by questionnaires and documentary evidence. The focus of semi-structured interviews was on professional roles, work activities, distribution of responsibilities, skills and competencies, and the structure of RDM services. Twenty-six participants from nine countries were recruited for the study (see Table 1 in the methodology section for the list of countries). The study participants were employed at 24 organizations, including academic libraries (19), campus-wide research data service centers (3), university departments (2), data archive (1), and research center (1). Among the participants, there were 11 females and 15 males. Their educational background varied with Bachelor’s degrees in humanities, social sciences, sciences, and engineering. All participants held Master’s degrees; 15 had Master’s degrees in Library and Information Science (MLIS). Ten participants had PhDs in a variety of disciplines, including biology, environmental science, history, information science, medical informatics, or philosophy.

Interestingly, several participants working at the European institutions did not have MLIS but had advanced disciplinary degrees and prior research experience. Some were hired specifically because of their research training to bridge the gap between the research community and the library world. Participant S, a researcher with a PhD in environmental science, stressed the importance of subject expertise and knowledge of the research process. She was encouraged to apply for her position “because they were looking actively for someone from research to join them because they want to have hands-on experience or people from the field, you know, directly from the trenches of research” (P-S, interview).

Position Titles

The participants held different position titles although many of their responsibilities and job functions overlapped. Three participants had administrative roles overseeing data curation or digital initiatives units. The variability of titles and an infrequent use of the term “data curator” confirms the findings from the content analysis. Phrases including “data curation,” “digital curation,” or “research data management,” in conjunction with terms “librarian” or “coordinator,” appeared in several titles and provided a foundation for grouping them (see Table 9).

Position titles of interview participants.

| Position Title | No. |

|---|---|

| Research Services/Research Data Management/Digital Curation/Data Curation/Research Data Coordinator | 6 |

| Data Curation/Research Data/Research Data Management/Data Librarian | 5 |

| Project Manager Research Data Management/Research Data Manager | 4 |

| Head of Department/Head, Research Data Services/Deputy Head | 3 |

| Project Scientist/Project Coordinator | 2 |

| Data Curation Scientist | 1 |

| E-research Project Officer | 1 |

| Humanities Data Curator | 1 |

| Principal Librarian | 1 |

| Research Data Officer | 1 |

| Business Developer | 1 |

| Total | 26 |

New Field

The information about participants’ background and positions indicates that RDM is a new service, especially in academic libraries. In many cases, the participants were hired for newly created positions. However, they often came with several years of prior professional experience in library services, scholarly communication, digital projects, or research. Years of experience in data management ranged from several months to over five years. In their new positions, they were often charged with developing the programs, as described by Participant W: “I’ve had to create and evolve a research data service from scratch almost. I mean there had been pre-existing work, but the concept of a service, a RDM service, hadn’t really existed” (P-W, interview). Typically, the early phase of a program development involved:

Planning and learning about RDM best practices and standards;

Conducting assessment of researchers’ practices and needs for data management;

Reaching out to faculty and graduate students to inform them about new services;

Participating in policy development for open access and institutional data management;

Building a network of experts in research data management and scholarly communication;

Developing an infrastructure for data storage and management.

The new and evolving nature of the positions offered the professionals some flexibility in shaping their roles and building the program. The emergent character of the field was emphasized by Participant K: “it’s young and we’re still learning and we’re still building up a lot of paths” (P-K, interview).

Participant Understanding of the Data Curation Concept

The study participants were asked to provide their own definition of data curator in the questionnaire. The responses to the question “Could you define what a ‘data curator’ is?” indicate significant differences in terminology across national settings. There are, however, common patterns in understanding what the job entails. The differences in terminology are primarily between an understanding of data curator as one overseeing the entire data management cycle and a narrower definition focused on technical aspects of archiving in the final stages of the data cycle. The use of the term data curator and its broad understanding was quite prevalent among the US professionals, while Australian and European participants made a clear distinction between data curators and data managers and did not use the terms interchangeably. Participant P stated:

Data manager is for the first part of the data life cycle and data curator is in the last part of it. The data curator reviews, migrates, and enhances data and metadata, whereas the data manager helps with data collection, metadata standards, and creating coherent and authentic data sets (that ideally subsequently need less curation). A data curator rather works with the final data objects, to optimize them to a final version that can’t be manipulated anymore after that. (P-P, questionnaire)

The distinction between data curation and research data management was emphasized by another European participant during the interview: “curation is more concentrated with the archiving and […] connected to the long preservation dimension, while research data management has to do with managing data through the whole process” (P-J, interview). Some participants in Europe used the term ‘data steward’ for professionals involved in assisting researchers “in planning research data, from collection, storage, analysis to publication and archiving” (P-Q, questionnaire). Despite the lack of consensus on terminology, the participants across countries and continents shared a common understanding of the purpose of the job and its primary responsibilities.

Participant B, working as a data librarian at a research university in Australia, emphasized communication skills and training in librarianship as important qualifications: “A data curator as a person (irrespective of title) who requires highly developed interpersonal skills, and who uses the core knowledge and skills of librarianship to assist researchers (usually in an academic setting) to manage and disseminate their research outputs” (P-B, questionnaire). The principles of managing data through its cycle, or even broadly through the research cycle, ensuring access for current and future use, adding value at each phase of the cycle, and caring about data quality, were common themes in the questionnaire responses across participants in multiple countries. Managing data through the phases of its life cycle appeared as a core responsibility in almost all responses. Participant I defined a data curator as “the individual who oversees the management of data through its life cycle” (P-I, questionnaire). Participant L stated that “A data curator actively manages research data at different (single/some/all) stages of its lifecycle. He/she maintains quality, integrity, interpretability and usability of data and adds value to it” (P-L, questionnaire).

Roles and Responsibilities

A sense of a shared purpose or even mission emerged as a prominent theme in the interviews. The participants across institutional and national settings emphasized that their primary roles and responsibilities involved assisting researchers in meeting funder requirements, improving data management practices, and ultimately contributing to more efficient research process and better quality data. Several participants mentioned the end-goal of “making data more usable” (P-L, interview), even for data producers, and efforts to advocate the FAIR principles, making data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. Participant O captured the complexity of the RDM professionals’ work, their multifaceted roles, and a broader mission:

so we have to do things because of funders and we have do stuff because legislation requires it but what we are actually doing is really creating research support which has not been taken care of ever, which enables us to do work more efficiently. (P-O, interview)

The supporting role was stressed by Participant B: “the role of the data librarian is more about helping them [researchers] to describe data, getting it online, helping them to share it” (P-B, interview). Depending on the organizational context, the supportive services could vary from offering guidance on compliance with funders’ expectations to advising on storage and data sharing. In addition, the participants viewed their roles as intermediaries between different stakeholders in the process of managing data and ‘translators’ of technical concepts and the language of metadata standards. In many cases, they served as coordinators connecting researchers to different pockets of expertise on campus, as described by Participant R:

I also try to sort of bring some focus in the school for those support services so people aren’t sort of, you know, bouncing around from person to person. They may or may not be aware of certain areas of support. (P-R, interview)

All professionals participating in this study were engaged in consultative services, outreach, and open access advocacy. A smaller number of participants assisted researchers with technical aspects of depositing data in repositories and archival storage. Many participants described their roles and responsibilities in the context of the data life cycle. Consultative and training services would usually take place at the beginning of the cycle and focus on developing data management plans (DMPs) and practices in sharing and archiving data, as described by Participant P:

We give them advice, particularly to all these project leads on how you might write a data management plan, but also the aspects of a data management plan, so we talked through what it means about collecting your data, licensing your data and sharing, archiving, publishing. So we try to get them to see the whole workflow, the whole, through the length of the project, how data management will come up at different stages. (P- P, interview)

Technical services were offered on a limited scale at the end of the cycle and often involved data cleaning and verification, metadata creation and documentation, ingesting into repository systems, data publishing, and archiving. Most professionals interviewed for this study, however, were not involved in providing technical services and managing data directly. Their efforts were primarily focused on working with researchers, offering advice, and training in data management practices and standards, as indicated by Participant E: “data curation is more about providing information about good data curation practices to the people who need to curate their data or could be curating data” (P-E, interview).

Outreach, training, and building a community around research data management were identified as major responsibilities. Participant S described her primary role: “I’m mostly there for the outreach, for the training scientists in research data management, so teaching them how to do the management before they can submit their data for preservation” (P-S, interview). Participant W estimated the distribution of his responsibilities:

data deposits probably around 5–10 %; data management plans is probably another 10 %; training and advocacy, that’s broadly defined, is probably around, to be honest 40 to 50 % of my time at the moment; and open access is, well it depends, it’s at least 10 %. (P-W, interview)

His estimates were confirmed by other participants who stated that on average they would spend 50 % of their time on outreach and training. While more time was devoted to reaching out to researchers in the early programs, outreach and training remained a key responsibility, even for those with more than two years on the job.

Outreach and training activities included workshops, one-on-one consultations, newsletters, online tutorials, and guidelines, but also special campus events and targeted efforts through project leads and department administrators. Outreach and advocacy efforts focused on:

Raising research data awareness;

Informing about research data services;

Educating about good data management practices;

Promoting open access and data sharing;

Building community around research data management.

The notion of community building emerged as an essential requirement for research data management. The topic recurred in multiple interviews where the participants emphasized the importance of bringing expertise together, sharing best practices in data management, collaborating on building interoperable infrastructures, and developing a shared understanding of the benefits of managed data and the impact of open data on scholarship and society.

Some participants, especially those with administrative or research responsibilities, viewed their roles as leaders around data management in their organizations. They stressed the importance of providing vision, exploring the trends in the field, promoting open access, and leading efforts in changing research culture, seen with Participant G who said: “My role is to provide organizational leadership on data issues, collaborate within and external to the organization, conduct independent research, engagement with the staff to promote and enable effective data and metadata management” (P-G, interview). The theme of leading change recurred in several interviews and touched on the broader mission of RDM professionals:

When we’re trying to raise awareness, we really try to stress the benefits of data management as well. And it’s that balance, really. Trying to get the right balance between making it known that funders require this, certain journal publishers require data preservation, open access and so on. So, we want to get that message across but at the same time we also want to try to change the research culture… That’s really what we want to be leading to; it’s not just about compliance but actually trying to change research culture and get people to think it’s good research practice. (P-V, interview)

The work of RDM professionals in improving data management practices and advocating open access occurs on multiple levels, starting with individual researchers and their teams, building networks at their institutions, and then expanding to regional, national, and international communities. The theme of shared values and changing research culture was discussed by participants from multiple countries, pointing to the emerging international character of the RDM profession. The RDM professionals interviewed for this study feel that they are part of a global movement, as discussed by Participant Y: “but it’s not just about the university itself, it’s about the whole global perspective… we feel part of a global community that’s trying to advance these issues and try and make this transformation across the world” (P-Y, interview).

Competencies

Data curation emerges as a new profession that involves a wide range of responsibilities and encompasses both technical and public services skills, seen with participant K who states that “I often find I wear different hats” (P-K, Interview). The new and evolving character of the positions requires expertise in multiple areas and ability to adapt to the changing environment. On the one hand, professionals work closely with researchers consulting on data management planning and teaching workshops. Outreach and training, which represent a significant portion of their jobs, require good communication, instructional, and presentation skills. On the other hand, data curators also assist with technical aspects of managing and archiving data. Participant J points to the hybrid nature of the profession by referring succinctly to “A combination of a librarian and a programmer” (P-J, Interview).

The study participants emphasized the importance of both communication (soft) skills and technical competencies. The skills that were frequently highlighted in the communication category include:

Ability to work effectively with scholars with different needs and levels of experience;

Teaching and presentation skills;

Ability to design and deliver effective presentations;

Ability to prepare learning and informational materials;

Communications and interpersonal skills;

Ability to develop collaborative relationships;

Ability to establish trust with the researchers in a changing field.

The general expertise discussed by participants included knowledge of metadata standards and data formats, sound understanding of research process and data from the life cycle perspective, and knowledge of data curation principles, practices, and technologies. In addition, the participants, especially those from Europe, mentioned the concepts of open access and open science, information security, ethical aspects of data sharing, intellectual property, and data protection law. The specific technical skills were often connected to the phases of the data life cycle and included expertise in:

Data management

Data formats and file naming conventions

Data cleaning and verification

Data conversion

Data description and documentation

Metadata creation using standardized schemas and vocabularies

Data linking

Data deposit/publishing

Ingest into repository systems

Assigning identifiers

Data citation

Data anonymization

Data security

Archiving and preservation

Specific technical expertise and the level of required skills depend on institutional settings. At smaller organizations or in the early phase of a program development, one or two professionals may be responsible for both consultative and technical services. In addition, curators need very strong technical skills to assist in the selection or development and implementation of repository new systems. At larger institutions, RDM units may employ several professionals with more distinct job responsibilities and include data managers whose work is devoted to processing and archiving data. However, even when data curators do not manage research data directly, their work requires a certain level of technical expertise since they often make recommendations on tools and technologies and lead data curation initiatives at their institutions, seen when Participant G stated that

for my position, I’m not doing much direct data manipulation or building data repositories, so it’s more about the awareness of what tools can be applied to what problems or what resources, as well as the ability to assess technology for a given question. (P-G, interview)

The study participants emphasized that it’s often impossible for one person to fulfill all the necessary skills and competences found in job descriptions. They identified competency gaps but also pointed out that the gaps depend on the professional and educational backgrounds. The lack of technical skills and hands-on experience with databases and scripting was mentioned for professionals with LIS backgrounds. Data curators with research backgrounds but no MLIS lack knowledge of the library metadata standards and structures for organizing information. However, the theme that became quite prominent in this study is the lack of expertise in research methods and understanding of the research process. Participant K emphasized the importance of having hands-on experience in conducting empirical research and ability to “talk the research talk.” Data curators with research background find it easier to build credibility and establish trust with researchers, as pointed out by Participant I:

It is really helpful when I go to speak to groups, and do sort of educational awareness, to have a good background in research methods to draw on, so I think it’s then not so quickly dismissed because I have an understanding of what it is they are trying to do in terms of their work. (Participant I, interview)

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings of this multi-phase study indicate that data curation is an evolving sociotechnical practice that involves not only technical systems and services structured around the research data life cycle but also a range of social activities around community building. This study finds common themes in social aspects of RDM, especially around efforts in raising awareness of open data, fostering culture of data sharing, and supporting the needs of researchers in the data-intensive environment. It reflects a general recognition of the need to reflect patterns in the life of the user, rather than expecting users to fit into the life of the library (Connaway 2015). Data curation emerges in this study as a global practice that is not only about technology and curating data but also about ‘curating people’ who create data. The role and value of a data curator profile needs to be discussed within the context of new research sharing culture and Open Science. While the importance of a robust technical infrastructure and the demands of changing technology cannot be ignored, it is acknowledged that the challenges to transition to Open Science and new modes of scholarly communication are primarily social (Ayris et al. 2016).

This study examined the roles, responsibilities, qualifications, and competencies of data curators from several perspectives using multiple sources of data. It confirmed the findings from the previous research about the lack of common terminology and a variability of the position titles (Kim, Warga, and Moen 2013; Swan and Brown 2008). Despite more than a decade of data curation research and practice, there is still limited agreement on vocabulary and titles for people who are involved in providing RDM services. This finding is quite significant as it was found in all three phases of the study. There are also some international differences with the term ‘data curator’ used primarily by US professionals. Despite the differences in terminology, a shared purpose and understanding of the roles points to an international character of the field.

The variability of titles, skills, and duties is also an indication of an emergent and evolving field. As the profession evolves, the roles may become more clearly defined. Larger institutions and those with more advanced services may have multiple positions, and a division of responsibilities with some professionals focusing on consultative services and fulfilling data librarian responsibilities, and data mangers working directly with data and providing technical services. The range of position titles and qualifications also shows that required expertise is diverse. Data curation emerges as a hybrid profession that combines technical and public services skills. The core responsibilities around outreach, training, and advocacy reflect the influence of librarianship on the role of data curator. While the importance of strong interpersonal and technical skills was found in previous research (Fearon et al. 2013; Kim, Warga, and Moen 2013; Xia and Wang 2014), this study also highlights the knowledge of the research process and research methods as key competencies of RDM professionals. The set of skills identified through the analysis of job postings as well as the interview data in this study maps closely to the data stewardship category, which was outlined in the EU report on the expertise needed to support turning FAIR principles into reality (Hodson et al. 2018). While the content analysis of job postings identifies some competencies related to data sciences, such as statistics, the majority of responsibilities is focused on making sure that data is properly managed, shared, and preserved. The concepts of the data life cycle or research workflows were used by the study participants to define their roles and responsibilities, which often took place at the beginning of the cycle with support for data management planning. The application of data life cycle models to developing and communicating data services was described in previous research (Ball 2012; Carlson 2014). They serve as useful frameworks for data curation profiles as they help to visualize the phases in the research process and to identify the activities that need support. In this study, the concept of data life cycle also highlighted the important role of data curators in adding value, supporting communication, as well as bridging and facilitating sharing and analysis of data by the actors involved in the research cycle.

This study also contributes new insights on the roles and qualifications of professionals actively supporting researchers in data management and sharing. Prior research surveyed academic library directors and focused on the ways libraries are involved in supporting RDM (Cox and Pinfield 2014; Cox et al. 2017; Fearon et al. 2013; Tenopir, Birch, and Allard 2012; Tenopir et al. 2015, 2017). The role of academic libraries in leading and developing RDM services emerges as an important theme in this study as well. Librarians offer instructional experience and unique expertise in information organization, metadata, and archiving. However, this study also found that many positions in practice were held by non-library professionals who were hired specifically because of their research background, knowledge of research methods, and domain expertise. This finding is consistent with the membership data from the organizations, such as Research Data Alliance where librarians represent one of several professional groups, along with researchers, project managers, and IT specialists (RDA 2018). The importance of research background has implications for education of future data experts that may need to combine technical skills, expertise in metadata and information organization standards, and knowledge of the research process and research methods.

The role of data curator illustrates the complexity of reality, while data librarianship requires a framework which does not yet exist. The underlying idea of the IFLA LTR research is that of focusing on a broader view of the profile, a reality not to be taken as fixed but part of an ongoing and fluid process. This is the reason why the research team was not able to complete the ontology that we had proposed; it would probably have been premature. In this regard, it is interesting to note that from the analysis of the corpora we have highlighted different concepts and terms used by different communities of actors involved in the role of the data curator.

References

Ayris, P., J.-Y. Berthou, R. Bruce, S. Lindstaedt, A. Monreale, B. Mons, Y Murayama, C. Södergård, K. Tochetermann, and R. Wilkinson. 2016. “Realising the European Open Science Cloud.” The Commission High Level Expert Group on the European Open Science Cloud. Accessed April 20, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/research/openscience/pdf/realising_the_european_open_science_cloud_2016.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Bailey, C. W. 2017. Research Data Curation Bibliography (version 7). Houston, TX: Digital Scholar.Search in Google Scholar

Ball, A. 2012. Review of Data Management Lifecycle Models (v. 1.0). Bath, UK: University of Bath. Accessed July 15, 2018. http://opus.bath.ac.uk/28587/1/redm1rep120110ab10.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Borgman, C. L. 2012. “The Conundrum of Sharing Research Data.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 63 (6): 1059–78. doi:10.1002/asi.22634/full.Search in Google Scholar

Borgman, C. L. 2015. Big Data, Little Data, No Data: Scholarship in the Networked World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9963.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Carlson, J. 2014. “The Use of Life Cycle Models in Developing and Supporting Data Services.” In Research Data Management. Practical Strategies for Information Professionals, edited by J. M. Ray, 63–86. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.10.2307/j.ctt6wq34t.6Search in Google Scholar

Center for Open Science. n.d. Accessed July 14, 2018. https://cos.io/.Search in Google Scholar

Connaway, L. S. 2015. “Introduction.” In The Library in the Life of the User: Engaging with People Where They Live and Learn, edited by L. S. Connaway, i–ix. Dublin: OCLC. http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/2015/oclcresearch-library-in-life-of-user.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Corrall, S. 2012. “Roles and Responsibilities: Libraries, Librarians and Data.” In Managing Research Data, edited by G. Pryor, 105–33. London: Facet Publishing.10.29085/9781856048910.007Search in Google Scholar

Corrall, S. 2014. “Designing Libraries for Research Collaboration in the Network World: An Exploratory Study.” LIBER Quarterly 24 (1): 17–48.10.18352/lq.9525Search in Google Scholar

Cox, A., M. Kennan, L. Lyon, and S. Pinfield. 2017. “Developments in Research Data Management in Academic Libraries: Towards an Understanding of Research Data Service Maturity.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 68 (9): 2182–200.10.1002/asi.23781Search in Google Scholar

Cox, A., and S. Pinfield. 2014. “Research Data Management and Libraries: Current Activities and Future Priorities.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 46 (4): 299–316.10.1177/0961000613492542Search in Google Scholar

Cox, A., E. Verbaan, and B. Sen. 2012. “Upskilling Liaison Librarians for Research Data Management.” Ariadne. http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue70/cox-et-al.Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. 2013. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

DCC: Digital Curation Center. 2018. “What Is Digital Curation?” Accessed December 7, 2018. http://www.dcc.ac.uk/digital-curation/what-digital-curationSearch in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2018. Implementation Roadmap for European Open Science Cloud. Accessed July 14, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/research/openscience/pdf/swd_2018_83_f1_staff_working_paper_en.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Faniel, I., and L. Connaway. 2018. “Librarians’ Perspectives on the Factors Influencing Research Data Management Programs.” College & Research Libraries 79 (1): 100. doi:https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.1.100.Search in Google Scholar

Fearon, D., B. Gunia, B. E. Pralle, S. Lake, and A. L. Sallans, and Association of Research Libraries. 2013. Research Data Management Services. Accessed June 1, 2018. http://publications.arl.org/Research-Data-Management-Services-SPEC-Kit-334/.Search in Google Scholar

Heidorn, P. B. 2011. “The Emerging Role of Libraries in Data Curation and E-Science.” Journal of Library Administration 51 (7–8): 662–72.10.1080/01930826.2011.601269Search in Google Scholar

Hey, T., S. Tansley, and K. M. Tolle. 2009. The Fourth Paradigm: Data-Intensive Scientific Discovery. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Research. Accessed July 14, 2018. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/fourth-paradigm-data-intensive-scientific-discovery/.Search in Google Scholar

Higgins, S. 2008. “The DCC Curation Lifecycle Model.” International Journal of Digital Curation 3 (1): 134–40.10.1145/1378889.1378998Search in Google Scholar

Higgins, S. 2011. “Digital Curation: The Emergence of a New Discipline.” International Journal of Digital Curation 6 (2): 78–88.10.2218/ijdc.v6i2.191Search in Google Scholar

Hodson, S., S. Jones, S. Collins, F. Genova, N. Harrower, L. Laaksonen, D. Mietchen, R. Petrauskaité, and P. Wittenburg. 2018. Turning FAIR Data into Reality. Interim report of the European Commission Expert Group on FAIR data. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1285272.Search in Google Scholar

Jaguszewski, J. M., and K. Williams. 2013. New Roles for New Times: Transforming Liaison Roles in Research Libraries. Association of Research Libraries. http://hdl.handle.net/11299/169867.Search in Google Scholar

Janke, L. M., A. Asher, and S. D. C. Keralis. 2012. The Problem of Data. CLIR Publication No. 154. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources. Accessed June 1, 2018. http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub154.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, J., E. Warga, and W. E. Moen. 2013. “Competencies Required for Digital Curation: An Analysis of Job Advertisements.” International Journal of Digital Curation 8 (1): 66–83.10.2218/ijdc.v8i1.242Search in Google Scholar

Kraker, P., D. Leony, W. Reinhardt, and G. Beham. 2011. “The Case for an Open Science in Technology Enhanced Learning.” International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning 3 (6): 643–54.10.1504/IJTEL.2011.045454Search in Google Scholar

Matusiak, K. K., and F. A. Sposito. 2017. “Types of Research Data Management Services: An International Perspective.” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 54 (1): 754–56.10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401144Search in Google Scholar

McGovern, N. Y. 2016. “Building Capacity: Curriculum, Competencies, and Careers.” In The Open Date Imperative: How the Cultural Heritage Community Can Address the Federal Mandate (CLIR Publication No. 171), edited by S. Allard, C. Lee, N. Y. McGovern, and A. Bishop. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources. Accessed June 17, 2018. https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub171.Search in Google Scholar

Molloy, J. C. 2011. “The Open Knowledge Foundation: Open Data Means Better Science.” PLoS Biology 9 (12). Accessed July 14, 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3232214/.10.1371/journal.pbio.1001195Search in Google Scholar

Open Knowledge International. n.d. Accessed July 14, 2018. https://okfn.org/opendata/.Search in Google Scholar

Pryor, G. 2012. “Why Manage Research Data?” In Managing Research Data, edited by G. Pryor, 1–16. London: Facet Publishing.10.29085/9781856048910Search in Google Scholar

RDA: Research Data Alliance. 2018. RDA in a nutshell (November 2018). Accessed December 7, 2018. https://www.rd-alliance.org/about-rda/who-rda.html.Search in Google Scholar

Rockenbach, A. N., M. J. Mayhew, J. Davidson, J. Ofstein, and R. C. Bush. 2015. “Complicating Universal Definitions: How Students of Diverse Worldviews Make Meaning of Spirituality.” Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice 52 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1080/19496591.2015.996058.Search in Google Scholar

Swan, A., and S. Brown. 2008. The Skills, Role and Career Structure of Data Scientists and Curators: An Assessment of Current Practice and Future Needs. A Report to the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC). Accessed June 15, 2018. http://ie-repository.jisc.ac.uk/245/1/DataSkillsReport.doc.Search in Google Scholar

Tammaro, A. M., K. K. Matusiak, F. A. Sposito, V. Casarosa, and A. Pervan. 2017. “Understanding Roles and Responsibilities of Data Curators: An International Perspective.” Libellarium: Journal for the Research of Writing, Books, and Cultural Heritage Institutions 9 (2). doi:10.15291/libellarium.v9i2.286.Search in Google Scholar

Tenopir, C., B. Birch, and S. Allard. 2012. Academic Libraries and Research Data Services Current Practices and Plans for the Future. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.Search in Google Scholar

Tenopir, C., D. Hughes, S. Allard, M. Frame, B. Birch, L. Baird, R. Sandusky, M. Langseth, and A. Lundeen. 2015. “Research Data Services in Academic Libraries: Data Intensive Roles for the Future?” Journal of eScience Librarianship 4 (2): e1085. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2015.1085.Search in Google Scholar

Tenopir, C., R. J. Sandusky, S. Allard, and B. Birch. 2014. “Research Data Management Services in Academic Research Libraries and Perceptions of Librarians.” Library & Information Science Research 36: 84–90.10.1016/j.lisr.2013.11.003Search in Google Scholar

Tenopir, C., S. Talja, W. Horstmann, E. Late, D. Hughes, D. Pollock, B. Schmidt, L. Baird, R. Sandusky, and S. Allard. 2017. “Research Data Services in European Academic Research Libraries.” Liber Quarterly 27 (1): 23–44.10.18352/lq.10180Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, et al. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship.” Scientific Data 3: Article number 160018. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18.Search in Google Scholar

Witt, M. 2008. “Institutional Repositories and Research Data Curation in a Distributed Environment.” Library Trends 57 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1353/lib.0.0029.Search in Google Scholar

Witt, M. 2012. “Co-Designing, Co-Developing, and Co-Implementing an Institutional Data Repository Service.” Journal of Library Administration 52 (2): 172–88. doi:10.1080/01930826.2012.655607.Search in Google Scholar

Xia, J., and M. Wang. 2014. “Competencies and Responsibilities of Social Science Data Librarians: An Analysis of Job Descriptions.” College & Research Libraries 75 (3): 362–88.10.5860/crl13-435Search in Google Scholar

Yoon, A., and T. Schultz. 2017. “Research Data Management Services in Academic Libraries in the US: A Content Analysis of Libraries’ Websites.” College & Research Libraries 78 (7): 920–33.10.5860/crl.78.7.920Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Data Curator’s Roles and Responsibilities: An International Perspective

- Getting the Central RDM Message Across: A Case Study of Central versus Discipline-Specific Research Data Services (RDS) at the University of Cambridge

- Expanding Academic Librarians’ Roles in the Research Life Cycle

- Context-Based Roles and Competencies of Data Curators in Supporting Research Data Lifecycle Management: Multi-Case Study in China

- Educating Peasants: the Beibei Public Library in Light of Chinese Rural Reconstruction, 1928–1950

- Benefits and Outcomes of Library Collections on Scholarly Reading in Finland

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Data Curator’s Roles and Responsibilities: An International Perspective

- Getting the Central RDM Message Across: A Case Study of Central versus Discipline-Specific Research Data Services (RDS) at the University of Cambridge

- Expanding Academic Librarians’ Roles in the Research Life Cycle

- Context-Based Roles and Competencies of Data Curators in Supporting Research Data Lifecycle Management: Multi-Case Study in China

- Educating Peasants: the Beibei Public Library in Light of Chinese Rural Reconstruction, 1928–1950

- Benefits and Outcomes of Library Collections on Scholarly Reading in Finland