Abstract

Youth with medical complexity (YMC) are a small subset of youth who have a combination of severe functional limitations and extensive health service use. As these youth become adults, they are required to transition to adult health, education, and social services. The transition to adult services is especially difficult for YMC due to the sheer number of services that they access. Service disruptions can have profound impacts on YMC and their families, potentially leading to an unsuccessful transition to adulthood. This meta-ethnography aims to synthesize qualitative literature exploring how YMC and their families experience the transition to adulthood and transfer to adult services. An in-depth understanding of youth and family experiences can inform interventions and policies to optimize supports and services to address the needs of this population at risk for unsuccessful transition to adulthood. Using Noblit and Hare’s approach to meta-ethnography, a comprehensive search of Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Index, and Sociological Abstracts databases, supplemented by hand searching, was conducted to identify relevant studies. Included studies focused on the transition to adulthood or transfer to adult services for YMC, contained a qualitative research component, and had direct quotes from youth or family participants. Studies were critically appraised, and data were analyzed using meta-ethnographic methods of reciprocal translation and line of argument synthesis. Conceptual data from ten studies were synthesized into six overarching constructs: (1) the nature and process of transition, (2) changing relationships, (3) goals and expectations, (4) actions related to transition, (5) making sense of transition, and (6) contextual factors impacting transition. A conceptual model was developed that explains that youth and families experience dynamic interactions between their goals, actions, and relationships, which are bounded and influenced by the nature, process, and context of transition. Despite the tremendous barriers faced during transition, YMC and their families often demonstrate incredible resilience, perseverance, and resourcefulness in the pursuit of their goals. Implications for how the conceptual model can inform practice, policy, and research are shared. These implications include the need to address emotional needs of youth and families, support families in realizing their visions for the future, promote collaboration among stakeholders, and develop policies to incentivize and support providers in implementing current transition guidelines.

Introduction

Children and youth with medical complexity (CYMC) are a subset of children and youth with chronic health conditions, who have a combination of severe functional limitations, substantial service needs, and high resource utilization [1]. Although CYMC represent less than 1% of all children and youth, they disproportionately account for one third of all child health care costs [2]. Compared to other children with chronic conditions, CYMC have poorer health [3], and are at higher risk for hospital readmissions [4] and fragmented care [5]. Technological advances have led to increased survival of CYMC, meaning more youth with medical complexity (YMC) are reaching adulthood and transferring to adult services [6].

For the purposes of this paper, we use the term “youth” to refer to individuals transitioning to adulthood, and in place of similar terms such as adolescents, young people, young adults, and emerging adults. Within the broad transition to adulthood that encompasses this developmental period, youth also undergo distinct, but interrelated transitions from children’s to adult health, education, and social services. Health care transition has been defined as the purposeful and planned movement of youth from children’s to adult health care systems that is comprehensive, developmentally appropriate, and psychosocially sound [7]. Unfortunately, the evolution of health service delivery has not kept up with the increasing numbers of YMC reaching adulthood. Far from being a seamless and comprehensive process, transition of health services is often reduced to “transfer,” a one-time event in which children’s providers “hand over” care to adult providers [8]. For YMC, health care transition is particularly difficult because of the sheer number of providers and services that will need to be transferred [2]. In addition to health care transition, youth and their families also experience transitions in the social and educational systems, as the care of YMC almost always spans multiple public sectors [1].

The transition to adulthood is a period of great change that affects not only youth, but their families as well. Families of YMC devote a significant amount of time and effort to care provision and coordination [9]. Therefore, it is important to consider YMC and their families as a unit. In this paper, we adapt the definition of family articulated by McDaniel et al. [10] to refer to a group of biologically or legally related people who play a significant role in the youth’s well-being.

The transition to adulthood and transfer to adult services are complex interrelated issues that continue to challenge health systems despite decades of work. An understanding of youth and family experiences is needed to inform future practice, policy, and research that will address the needs of this population in meaningful ways. Patient experience has been widely recognized as a key outcome of high quality health systems, and is one of the overarching goals of the “Triple Aim” framework. This framework has been proposed as a unified approach for evaluating health care transition on the indicators of patient experience, population health, and cost of care [11]. Qualitative research is best suited to understanding experiences, and there is a growing interest in utilizing qualitative research to inform policy and practice [12]. Approaches to synthesizing qualitative evidence primarily fall into two general categories based on their purpose: (1) to integrate, aggregate, and summarize evidence, or (2) to develop new interpretations and theory [13].

A deeper understanding of the nature of youth and family experiences with transition is needed to inform future interventions and policies that can support transition and transfer. An interpretive approach to synthesis is required to move beyond an aggregation of data, and to closely examine the constructs underlying transition. Previous reviews on the transition experiences of YMC or similar populations [14], [15] have taken an aggregative approach. To our knowledge, this paper will be the first to undertake an interpretive approach to evidence synthesis on the transition to adulthood and transfer to adult services for YMC and their families. The aim of this paper is to synthesize qualitative literature and deliver novel interpretations that answer the following research question: “How do YMC and their families experience the transition to adulthood and transfer from children’s to adult services?”

Methods

Meta-ethnography is a methodology for qualitative evidence synthesis that takes an interpretive and inductive approach to inquiry. We selected meta-ethnography as our approach to synthesis because it is firmly grounded within the interpretive paradigm and fits with our aims to develop new insights and theory. We followed Noblit and Hare’s [16] seven-phase approach to meta-ethnography that includes: getting started, deciding what is relevant, reading the studies, determining how the studies are related, translating the studies into one another, synthesizing translations, and expressing the synthesis. We also drew on literature that has advanced meta-ethnography for health research [17], [18], [19]. Like other research traditions, meta-ethnography comes with unique terminology. Definitions of key terms used in meta-ethnography are provided in Table 1. To increase clarity of reporting, we will refer to the authors of included studies as “study authors” and the authors of this meta-ethnography as “reviewers.” We followed the eMERGe meta-ethnography reporting guidance [20] in expressing this synthesis (see Supplementary Material 1: eMERGe checklist).

Terminology used in meta-ethnography.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Concepts | The main ideas or organizing themes revealed through qualitative inquiry. Concepts are used to summarize the study and are the basis of reducing and translating the study. Interchangeable terms: metaphors, themes, organizers [16] |

| First-, second-, and third-order constructs | First-order constructs: Study participants’ views and interpretations of their experiences (presented as direct quotes of participants) Second-order constructs: Study authors’ interpretations of participants’ interpretations Third-order constructs: Reviewers’ interpretations of study authors’ interpretations [17], [19] |

| Translation | A type of synthesis that results from comparing key concepts between studies. An adequate translation combines studies while maintaining the original meanings and relationships of each study. Translations are reciprocal when the studies are directly comparable, and refutational when the studies are opposing in nature [16] |

| Line of argument synthesis | “Grounded theorizing” about a phenomenon based on the translations of the included studies. While translation occurs between studies, line of argument synthesis occurs across all studies [16] |

| Line of argument | The output of a line of argument synthesis: a conceptual model linking third-order constructs together [16] |

| Overarching explanation | The overall conclusions interpreted by study authors to explain their findings, which may take the form of a theory or model. The overarching explanation of a meta-ethnography is developed through a line of argument synthesis. Interchangeable terms: storyline, conclusions, theory, overarching model [18] |

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in consultation with a health sciences librarian. The first reviewer (LL) comprehensively searched the following databases from inception to February 2019: Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Index, and Sociological Abstracts. These databases were selected because articles on YMC are most likely to be published in health and social science journals due to the heavy involvement of YMC with health and social services. The search strategy was informed by Cohen et al.’s [1] definition of medical complexity, which is based on needs and functional status and not on diagnostic criteria. Search terms included keywords related to youth, transition or transfer, and medical complexity. Because we used a needs-based definition of medical complexity, we included key words known to be associated with this population (e.g. complex, medically fragile), as well as terms describing medical technologies commonly used within this group (e.g. gastrostomy, tracheostomy). See Supplementary Material 2 for a sample search strategy. After the initial search, we decided to exclude records published before 2002, to coincide with a key consensus statement that led to an increased focus on the transition of youth to adult health services [21]. The search strategy also included hand searching of key journals and the GotTransition® website [22], as well as reference lists of included articles and literature reviews identified through the search.

Study selection

Three reviewers (LL, MB, PS) performed pilot screening of 20 records, after which inclusion and exclusion criteria were refined. Due to the inconsistency in terms used to define this population in the literature, we decided to include youth populations who fit either Cohen et al.’s [1] previously described definition of medical complexity, or Major et al.’s [23] definition of complex care needs. Major et al. [23] describe care needs as complex based on the breadth (i.e. multiplicity and diversity) and depth (i.e. intensity or frequency) of needs. Two reviewers (LL and MB) conducted title and abstract screening using the following inclusion criteria: (1) study focuses on the transition to adulthood or transfer from children’s to adult services, (2) youth have a chronic condition that fits either Cohen et al.’s [1] definition of medical complexity, or Major et al.’s [23] definition of complex care needs, (3) youth or family perspectives are included, and (4) work is published in the English language. Next, LL screened full-text manuscripts that were included after title and abstract screening, with two additional inclusion criteria: (1) primary qualitative or mixed methods study with direct quotes from youth/family participants and (2) at least 50% of youth have complex care needs. A significant challenge of doing a comprehensive literature search to identify studies that include YMC is that “medical complexity” cannot be reliably identified based on diagnoses, yet research studies are often condition-specific. Therefore, studies may include both youth with and without medical complexity. To mitigate the possibility of underrepresenting the voices of YMC and their families, we decided to only include studies in which 50% or more youth have complex care needs. See Table 2 for the final inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Primary focus is the transition to adulthood and/or transfer from children’s to adult services | Primary focus is another type of transition (e.g. hospital to home) |

| Youth in the study have a chronic condition with medical complexity [1] or complex care needs [23]. For youth who have a condition associated with a range of functional levels, studies were included if 50% or more of youth had complex care needs or were technology-dependent | Youth in the study either do not have a chronic condition or their care is primarily managed by a single subspecialist (e.g. diabetes, cystic fibrosis, hematological disorders, without comorbidities). For youth who have a condition associated with a range of functional levels, studies were excluded if less than 50% of youth had complex care needs or were technology-dependent, or if needs were unable to be determined |

| Includes direct quotes from youth and/or family participants | Does not include direct quotes from youth and/or family participants |

| Study uses qualitative methodology (or includes a qualitative component) | Study does not include qualitative methodology |

| Published in English since 2002 | Unpublished work, not in English, or published before 2002 |

Reading and relating the studies

Study characteristics and key contextual data were extracted by LL using a modified version of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Qualitative Data Extraction Tool [24]. The full texts of the abstract, findings, discussion, and conclusion sections of each article, along with relevant tables and figures, were extracted into Dedoose for coding of conceptual data. To understand how the studies related to each other, three reviewers (LL, MB, PS) compared each study’s aims, context, participant characteristics, key concepts, and overarching explanations. Studies whose aims did not align closely with the aim of the meta-ethnography or were too narrow in context were excluded at this stage. Consensus was reached by these reviewers about how the studies were related and which studies to include in the synthesis. All studies were then read again by LL to determine whether they were reciprocal accounts (studies that described similar interpretations) or refutational accounts (studies that reported contradicting or disconfirming interpretations).

All studies that were included for synthesis were independently critically appraised by two reviewers (LL/MB or LL/PS) using the JBI Checklist for Qualitative Research [25] and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. While quality appraisal is common in meta-ethnography, there is a lack of consensus about how it should be used [26]. We chose not to exclude studies based on quality, but instead, to reflect on which studies contributed more or less to our interpretations. We assumed that studies with more conceptual depth would naturally have greater influence on the final synthesis output. To test this assumption, we checked whether our findings would still be supported if we had only included studies that were high quality or contained substantial conceptual depth.

Translating and synthesizing the studies

Translation involves comparing and reducing the studies to key concepts, while preserving the context and relationships of each particular study [16]. Two reviewers (LL/MB or LL/PS) independently performed open coding of the abstract, findings, discussion, and conclusion sections of each article, as well as any relevant tables and figures. The data were interpreted in terms of first- and second-order constructs (see Table 1 for definitions). For reciprocal accounts, we translated concepts from one study into another, and then translated the next study into the synthesis of the previous two studies, and so on. We chose to begin by translating conceptually rich, methodologically strong studies, and translated more descriptive and methodologically weak studies later. To preserve the conceptual meanings in each study, each concept was given a working definition using language from that study. As we identified similar concepts across studies, the concept descriptions were updated to reflect all the studies to which they applied, thereby creating a “reciprocal translation.” We also looked for possible refutational accounts and after examining the contextual factors of these studies to understand why differences occurred, we determined that there were no truly refutational accounts (see Findings). However, had true refutational accounts been identified, we would have conducted a refutational analysis as an additional stage in the meta-ethnography.

The analysis team (LL, MB, PS) met eight times to discuss ongoing translation and synthesis. An audit trail of all decisions was kept and reviewers created analytic memos that were discussed during these meetings. To ensure that we were not simply “re-categorizing” the findings, we considered a wide range of interpretations, including both obvious relationships between concepts, as well as more hidden ones. We did this by discussing and questioning each reviewer’s evolving interpretations of key concepts and relationships. The final list of first- and second-order constructs was synthesized into third-order constructs by examining how the second-order constructs were related. Each third-order construct reflects the relationship between two or more second-order constructs. Next, each member of the analysis team independently diagrammed the relationships between third-order constructs, and subsequently met to discuss, merge, and reach consensus on a final overarching model, or line of argument. Lastly, to ensure that the context and relationships were preserved within and across studies, LL compared the main concepts and overarching explanation of each primary study to the third-order constructs and line of argument developed by the analysis team.

Findings

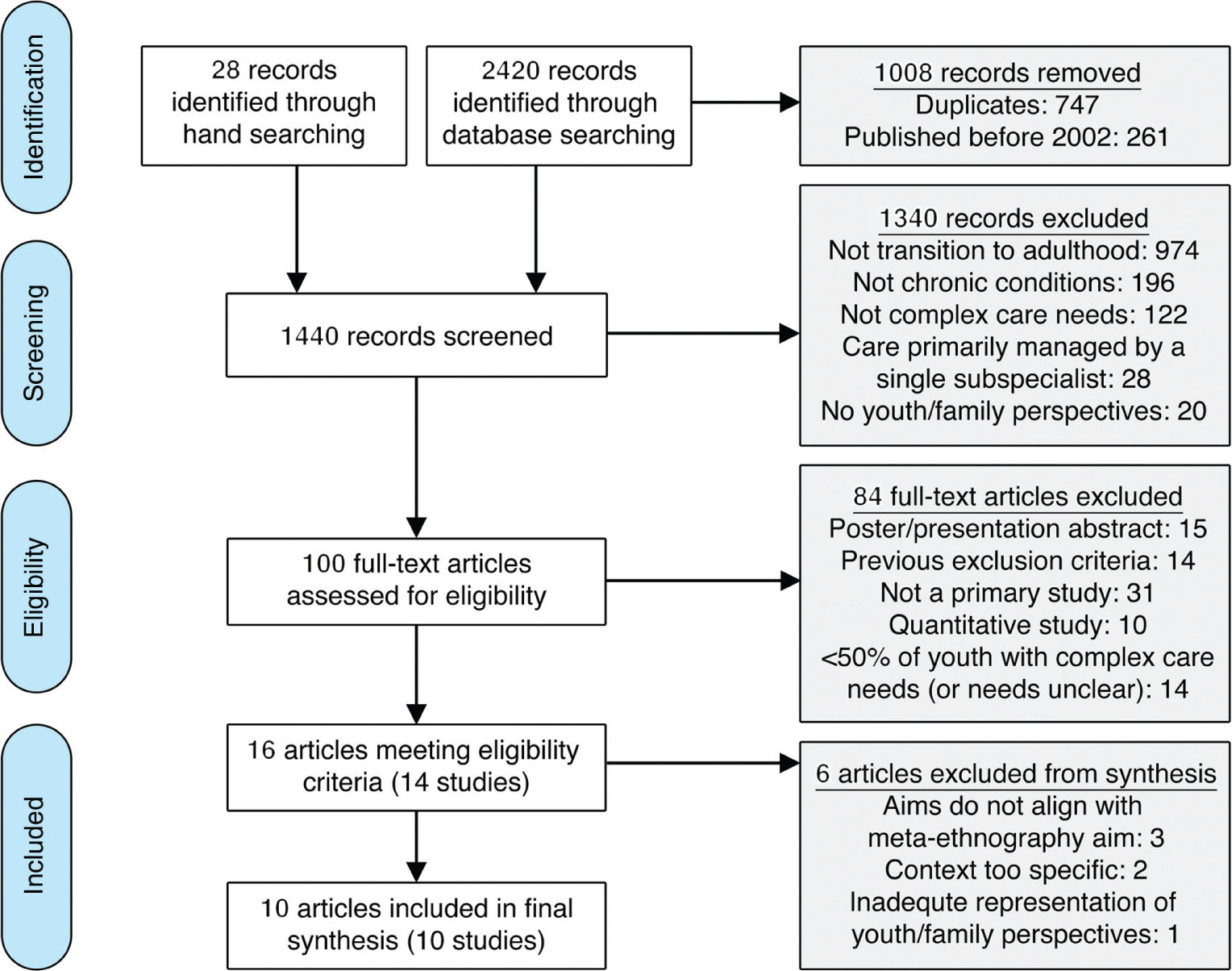

Database searching identified 2420 records, and hand searching identified another 28 records. Following the study selection process outlined in Figure 1, 16 articles met eligibility criteria, and 10 articles representing 10 studies were included for synthesis. Reasons for excluding the 6 eligible articles at the last stage include: aims do not align with meta-ethnography aim, context too specific, or inadequate number of youth/family participants. For example, we excluded a study exploring the transition of three young adults from an inpatient pediatric hospital to adult community residences [27], as there was not enough representation of youth/family perspectives and the context was also too specific to translate well into the other included studies (see Supplementary Material 3 for a list of excluded studies).

PRISMA flow diagram.

Approximate placement: at the beginning of the findings section.

Methodological quality and study characteristics

The 10 included studies employed the following designs: descriptive qualitative design [28], [29], [30], [31], interpretive qualitative design [32], case study [33], ethnography [34], grounded theory [35], phenomenology [36], and realist evaluation using mixed methods [37]. Overall, most of the included studies demonstrated congruity between research methodology, objectives, methods, and the interpretation of findings. The most common methodological limitations included: not including a statement that locates the researcher(s) culturally or theoretically (n = 9), not addressing the influence of the researcher(s) on the research (n = 7), and not stating the philosophical perspective or theoretical underpinnings of the study (n = 7). It is possible that these limitations reflect study authors’ or publishers’ decisions to omit this information and do not necessarily mean that reflexivity and philosophical perspectives were not considered. Another important limitation of this body of literature was the descriptive nature of four of the included studies, as meta-ethnography relies on rich conceptual data. However, we confirmed our initial assumption that studies with more interpretive depth had greater influence on the synthesis. Four studies [32], [34], [35], [37] were identified as both conceptually rich and methodologically strong; as such, we labeled these as “key studies” in the synthesis. Details about the quality assessment of each included study can be found in Supplementary Material 4.

The included studies were conducted in the following countries: Canada [28], [31], [32], [33], [36], the United States [34], [35], the United Kingdom [29], [30], and Ireland [37]. Study participants included youth and their parents/family caregivers. There were no studies that included siblings or other family members. Among studies that reported youth and parent gender, 57% of youth were male and 43% were female [28], [29], [30], [33], [36], while 22% of parents were male and 78% were female [28], [30], [31], [32], [36]. Study characteristics can be found in Table 3.

Study characteristics and aim(s).

| Author, Year | Country | Design | Quality | Youth population | Participants | Aim(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerr et al., 2018a [37] | Ireland | Realist evaluation using mixed methods | High | Young adults with life-limiting conditions (ages 18–24 years) | 29 organisations, 8 young adults, 10 parents/carers, 17 service providers | To develop programme theory about the interventions, and organisational and human factors that help or hinder a successful transition from children’s to adult services |

| Dale et al., 2017 [28] | Canada | Descriptive qualitative | Moderate | Ventilator-assisted adolescents (ages 17–21 years) | 18 adolescents and family caregivers (14 episodes of transition) | To explore the experiences of Canadian mechanical ventilator-assisted adolescents and their family caregivers as they transition from paediatric to adult health providers and to identify facilitators and potentially modifiable barriers |

| Kirk and Fraser, 2014 [30] | UKb | Descriptive qualitative | Moderate | Young people with life-limiting conditions (ages 16–31 years) | 16 young people, 16 parents, 7 hospice staff | To examine how young people with life-limiting conditions and their parents experience transition, to identify families’ and hospice staff’s perceptions of family support needs during transition to adulthood and adult services, and to identify the implications for children’s hospices |

| Cook et al., 2013 [33] | Canada | Case study | Moderate | Young adults with pediatric life-threatening conditions (ages 20–28 years) | 10 young adults | To describe the complex interplay of the health, education, and social service sectors in the transition from pediatric palliative services to adult care |

| Schultz, 2013a [35] | USb | Grounded theory | High | Adolescents with epilepsy and cognitive impairments (ages 20–33 years) | 7 parents | To explicate processes that parents of adolescents with epilepsy and cognitive impairments undergo as they help their adolescent transition from pediatric to adult health care |

| Rehm et al., 2012a [34] | USb | Ethnography | High | Youth with a chronic physical health condition and a developmental disability (ages 14–26 years) | 64 Youth, 77 parents, 27 health care providers, 46 special education teachers | To describe the meaning of adulthood for these youth and parents, discovering how parents worked with school, community, and health care professionals and other resources in planning for the transition to adulthood, and to analyze the impact of care on family roles and responsibilities |

| Davies et al., 2011a [32] | Canada | Interpretive qualitative | High | Young adults with a complex chronic neurological condition and intellectual impairment (ages 18–21 years) | 17 parents of 11 young adults | To identify salient issues related to the transition from pediatric to adult health care services confronting parents of young adults with a complex chronic neurological condition and intellectual impairment |

| Kingsnorth et al., 2011 [31] | Canada | Descriptive qualitative | Moderate | Youth receiving augmentative communication support (ages 12–21 years) | 30 parents | To describe the impact of a Family Facilitator-led Transition Peer Support Group for parents of transition-age youth that targeted parents’ knowledge and skill in navigating relevant social and health care systems |

| Kirk, 2008 [29] | UKb | Descriptive qualitative | Moderate | Young people with complex health care needs (ages 8–19 years) | 28 young people | To describe how young people with complex health care needs experienced transitioning to adult services, self-care, and independence |

| Magill-Evans et al., 2005 [36] | Canada | Phenomenology | Moderate | Youth with cerebral palsy (ages 20–23 years) | 3 youth and 9 parents (6 families) | To explore the perceived dynamics of relationships between parents and youths with disabilities during the child’s transition to adulthood |

aKey studies identified as both methodologically strong and conceptually rich are bolded. bUK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Relating the studies

Because there were a small number of included studies and many similar concepts, it was feasible and practical to create reciprocal translations across all studies. We did not identify any refutational accounts because differences in youth and family experiences were predictably explained by contextual variation. For example, while most studies reported negative youth and family experiences related to coordination, information sharing, and planning [28], [29], [30], [32], [33], [35], [37], participants in three studies also reported positive experiences as a result of proactive planning and coordination by providers [28], [33], [37]. These positive and negative experiences explain two sides of the same phenomenon, and are therefore complementary rather than refutational.

First-order constructs

We identified five first-order constructs (Table 4) representing the experiences of YMC and their families that were each supported by “key studies.” Nine studies described system- and service-related experiences resulting from the termination of children’s services and the need to navigate the new adult system [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [37]. Seven studies described relational experiences of youth and their families with their providers [28], [29], [30], [32], [34], [35], [37]. Nine studies reported emotional experiences related to the uncertainty and immense burden associated with transition [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [34], [35], [36], [37]. Nine studies reported experiences related to adulthood, resulting from changes in developmental maturity or shifts in societal expectations [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [36], [37]. Lastly, eight studies described health- and disability-related experiences in which the youth’s disability, health status, or medical complexity were perceived to influence transition [28], [29], [30], [32], [33], [34], [36], [37].

First-order constructs.

| First-order construct | Description | Illustrative quotes (from primary study participants)a |

|---|---|---|

| System- and service-related experiences | Youth/family experiences related to adjusting to the new adult system, navigating gaps in services, advocating and being forced to shoulder responsibility, and receiving information and preparation for transition | Youth: “When I was a kid it was like the doctors kept on top of my medical condition and everything involving it. In adulthood I really have to seek out any sort of help when it comes to specialists and doctors.” [33] Parent: “I need a quarterback. No offense, neurologist, and surgeons, and all you people, but I need a leader of this team. Somebody who’s going to understand and know everybody. Otherwise, I’m going to have to quarterback it.” [35] |

| Relational experiences | Youth/family experiences concerning the relational aspect of service provision. Changing the nature of service provision changes the nature of relationships | Youth: “They [children’s service providers] become a part of your family…so then you just ‘let go’ from that and then [you are] given on to someone else…” [37] Parent: “It was like after all those years we had depended on the (pediatric) hospital to help us, and now we had the impression that we were on our own. No one knew us, we were nothing. We were a number.” [32] |

| Emotional experiences | Youth/family experiences related to uncertainty about the future, the emotional toll of transition, and support received to address emotional needs | Parent: “Transition to me equals sheer fear…It’s like jumping off a cliff. And if you’re really well prepared – you might have a parachute or a trampoline along the way for a short respite period there…” [35] Parent: “Getting support from other parents and knowing that you are not the only one who has these problems…not just me who is struggling, we are all struggling.” [31] |

| Experiences related to adulthood | Youth/family experiences related to shifts in roles and responsibilities, promotion of the youth’s independence and autonomy, and goals and actions for the youth’s future as an adult | Youth: “I’d like to be here in this area because I had some friends here. I don’t wanna end up with no friends around. ’Cause that sucks. I’d like to stay here, go to one of those schools around here.” [34] Parent: “They treat her, not like a child, but more of an adult, giving her choices and that.” [30] |

| Health- and disability-related experiences | Youth/family experiences related to the youth being seen for their disability, and the effect of the youth’s health status and medical complexity on transition | Youth: “The doctors who specialize in “normal” things sometimes look at me like I have a disability and I deserve to be treated differently because of that. They’ve not been very understanding that we all just want to feel and live as normal a life as everyone else.” [33] Parent: “…their self-management, obviously, it would make things easier for them, but they’re deteriorating, so they’re learning to do more things that they’re probably not going to be able to do in the long run…” [37] |

aSee Supplementary Material 5 for studies contributing to each construct.

Second- and third-order constructs

We identified 16 second-order constructs representing study authors’ interpretations, which were synthesized into six third-order constructs (Table 5). The next section describes each of these third order constructs, with examples of supporting second-order constructs. All constructs were backed by “key studies.” A list of all studies contributing to each first- and second-order construct can be found in Supplementary Material 5.

Second- and third-order constructs.

| Third-order construct and description | Second-order constructs and descriptions | Illustrative quotes (from study authors)a |

|---|---|---|

| Construct 1: The nature and process of transition The transition process can be defined in terms of critical points and events, as well as the multiple dimensions of the youth and family’s lives that are affected | Multidimensional transition Transition affects multiple aspects of the youth and family’s lives, and often involves multiple services, providers, and sectors Critical points in the process Transition is punctuated by critical points in the process, such as “aging out,” insurance/funding changes, and transfer of care between children’s and adult providers | “The complexity of the medical transition process has resulted in a fragmented focus on health care transitions that mostly exclude the social and educational systems.” [33] “Transitioning from the pediatric to the adult health care system was not planned. Rather, the journey was sparked by a crisis involving the adolescent’s health or a change in insurance.” [35] |

| Construct 2: Changing relationships As the youth reaches adulthood, changes in relationships occur with their providers as a result of changes in service provision, and with their families as a result of the youth’s developing autonomy | Relationships with providers Transfer leads to the loss of familiar settings and trusting relationships with providers. Establishing new relationships with adult providers and settings promotes confidence and helps youth and parents feel situated | “Parents spoke of the loss of trusting relationships within the pediatric health care setting and greatly missed these bonds.” [32] “…parents in this study expressed satisfaction with their transition once they established an interpersonal dialogue with their new adult health care provider.” [35] |

| Relationships within the family Changes in family relationships include parents’ shifting, but ongoing role in the youth’s care, new family conflict, and youth and parents’ concerns about the effect of their declining health on their families | “Young people’s accounts presented professionals as playing a peripheral role in their transition to self-care. Their knowledge about how to manage their condition appeared to come from their parents.” [29] | |

| Construct 3: Goals and expectations Youth and parents’ goals for transition focus on promoting the youth’s independence and autonomy and planning for a high quality of life in adulthood | Independence and autonomy Youth, parents, and providers desire and promote independence and autonomy for youth, to the best of their capacity. The youth’s independence is often limited by financial and system barriers | “…the families with both youth and parental desire for the child’s autonomy established the most marked changes in their relationships.” [36] |

| Planning for a good adult life Youth and parents desire, envision, and plan for the youth to lead a good life in adulthood. Lack of options leads to youth and parents experiencing uncertainty about how and if they can achieve their vision for a good adult life | “…parents emphasized the need to identify supportive, meaningful programs that would allow youth to develop social relationships, use their unique abilities, and satisfy their need to feel part of the community in post-school years.” [34] | |

| Construct 4: Actions related to transition Concrete actions are taken by youth, parents, and providers to facilitate transition, including advocating, networking, communicating, collaborating, and finding information | Advocating Youth and parents advocate for appropriate services, support, and care that are crucial to maintaining the youth’s well-being. Sometimes parents or youth are forced into this role out of perceived necessity | “Parents emerged as advocates; they possessed a repertoire of skills that were crucial to securing care for their adolescent and traversing the maze of information from insurance/funding agencies, health care providers, and parent support groups.” [35] |

| Communicating and collaborating Effective communication and collaboration between children’s and adult services, between agencies and sectors, and between providers and youth/parents promotes successful transition | “Informational resources and joint paediatric-adult team transition meetings functioned to diminish strong emotions regarding the loss of trusted paediatric clinicians, to clarify expectations and to generate a sense of security with the new adult team.” [28] | |

| Finding information Youth and parents seek information on available resources for transition. Often, this information is inconsistent and not readily available | “Although some parents were resourceful in seeking out information through their informal social networks, the information they obtained was largely inconsistent.” [32] | |

| Networking Youth and parents create or participate in social networks for the purposes of information sharing, psychosocial support, advocacy, and socialization | “All of the parents indicated that networking with other parents and parent support groups was the most reliable and helpful way to locate community and funding resources.” [35] | |

| Construct 5: Making sense of transition Emotional processing of the transition is related to uncertainty and inner turmoil, as well as empowerment as a result of feeling respected and valued. “Making sense” results from and leads to changing relationships, goals and expectations, and actions taken | Uncertainty and inner turmoil Transition is associated with uncertainty, emotional turmoil, and unmet emotional support needs Being respected and valued Youth and parents want to be respected and valued. Youth and parents experience patronizing attitudes and discrimination towards them due to others’ perceptions of the youth’s needs and disabilities | “Parents had unmet emotional needs and were unclear of support available once their children reached adulthood.” [30] “A person-centred approach being demonstrated by service providers […] was considered to contribute to the young adult feeling listened to and valued and, therefore, instilled in them a sense they were not only central to the processes of their care, but they had an influence in directing their care.” [37] |

| Construct 6: Contextual factors impacting transition Youth, family, social, and system factors impact the transition and make each transition highly unique | Youth factors Youth factors include the youth’s attitude, resilience, strengths and functional abilities, and medical stability and complexity | “Resilience, community support, persistence, and hopefulness enabled these young adults to navigate and persevere through system barriers.” [33] |

| Family factors Factors related to the youth and family unit include information and preparation related to transition, parents’ declining health status, and competing family responsibilities | “Parents spoke of their responsibilities in providing care for not only the young adult, but also themselves and other family members. This placed competing demands on parents who, at times, felt extremely overwhelmed.” [32] | |

| Social factors Social factors include community resources and support from friends, family, and social networks | “…parents recognized the importance of opportunities to share their common experiences and the benefits of mutual support for this new phase in their lives.” [31] | |

| System factors System factors include perceived limitations of the system, access to information and services, and differences between children’s and adult services | “Transition planning was absent or poorly coordinated; for most families, there were no equivalent adult health/social services.” [30] |

aSee Supplementary Material 5 for studies contributing to each construct.

Construct 1: the nature and process of transition

A multidimensional transition affected many realms of the youth and family’s lives. For example, transition affected family functioning [30], [36], social participation [31], [34], and health and safety [29], [30], [33], [34]. Transition also involved multiple services, providers, and sectors [29], [33], [34], [35]. Despite the multidimensional nature of transition, service providers tended to focus on the one-off event of “transfer,” rather than a more holistic transition to adulthood [28], [29], [32], [35]. Furthermore, transition was defined by static, system-mandated critical points in the process such as the age of transfer [32], [33], [35].

Construct 2: changing relationships

Transition was associated with changing relationships with providers. Youth and their families had grown up in children’s services and had formed long-standing, trusting relationships with their children’s providers. The transfer to adult services led to feelings of loss when these relationships ended [28], [29], [32], [35]. Establishing new, positive relationships with adult providers helped youth and their families feel situated and develop confidence moving forward [28], [35], [37]. Relationships within the family also changed in response to the youth’s developing autonomy [29], [30], [36], [37], and in some cases, the youth’s declining health status [29], [30], [33], [37] and increased need for parental caregiving [28].

Construct 3: goals and expectations

Youth and their families had goals for adulthood that focused on promoting the youth’s independence and autonomy to the best of their capacity [30], [33], [34], [36], [37], as well as planning for a good adult life. A good adult life was related to the youth’s goals for work, education, and social participation [31], [33], [34], [36], [37]. Realizing these goals was dependent on an enabling environment [29], and was often limited by financial and system barriers [33], [36]. Despite these barriers, YMC and their families demonstrated incredible resilience and perseverance in pursuing their goals [31], [32], [33], [35].

Construct 4: actions related to transition

Youth, families, and providers took action to facilitate transition and work towards the youth and family’s goals. These actions included advocating, networking, communicating, collaborating, and finding information. Both youth and their families advocated for the youth’s role in decision-making [29], [30], [36], [37], and for appropriate services and support [31], [33], [35]. Effective communication and collaboration between youth, families, agencies, and children’s and adult providers facilitated transition [28], [33], [37], whereas lack of communication and collaboration led to an abrupt and disorganized transfer [28], [33], [34], [35]. Youth and their families desired information related to transition [31], [33], [37]; however, this information was often inconsistent and not readily available [28], [35]. As a result, youth and their families often relied on themselves and on peer networks for information and advocacy [31], [32], [33], [35]. The actions that YMC and their families took towards achieving their goals highlight the resourcefulness, creativity, and unique skills that YMC and their families have developed through years of advocacy and navigating system barriers.

Construct 5: making sense of transition

“Making sense” of transition involved emotional processing that either led to uncertainty and inner turmoil, or empowerment as a result of being respected and valued. Transition was fraught with uncertainty about the youth and family’s goals and future [34], who would care for the youth [32], [33], and what services and supports would be available [29], [30], [31], [32], [35]. A positive aspect of transition was that youth experienced a newfound sense of being respected due to their “adult status,” as well as increased autonomy, independence, and self-esteem [29], [30], [33]. On the other hand, patronizing attitudes and discrimination based on the youth’s disability were disempowering for youth and their families [33], [36].

Construct 6: contextual factors impacting transition

Contextual factors interacted to create unique transition experiences. Youth factors included attitudes and resilience [33], personal strengths and functional capacities [28], [33], [34], [35], [36], and medical stability and complexity [32], [33]. Family factors included information and preparation received about transition [28], [29], [32], [35], and parental health status and competing family demands (e.g. caring for other family members) [32]. Social factors included support from others, such as peer support groups [31], [32], [33], [35], the youth and family’s community [33], [34], and service providers [28], [29], [30], [33]. Lastly, system factors included perceived limitations of the system [28], [32], [33], [35], [37], accessibility of information and services [28], [30], [31], [32], [33], [35], [36], [37], and differences between children’s and adult services [32], [33], [37].

Line of argument

A line of argument (Figure 2) explains the relationships between the third-order constructs. YMC and their families experience the transition to adulthood and transfer to adult services as interactions between changing relationships, goals and expectations, and actions to facilitate transition. Youth and families “make sense” of transition through emotional processing of these interactions. For example, ending relationships with providers creates a sense of uncertainty, which then compels families to take action, establish new relationships, and modify their expectations. Being respected and valued contributes to youth and family empowerment and positive transition experiences. Youth and their families feel supported when their goals, relationships, and actions are concordant and create a positive feedback loop that allows transition to progress. On the other hand, when these components are discordant, youth and their families experience uncertainty and inner turmoil. The transition experience is bounded by the nature and process of transition, which is both multidimensional and determined, in part, by system-mandated critical points in the process. Lastly, transition is influenced by contextual factors at the youth, family, social, and system levels.

Making sense of transition: a line of argument conceptual model.

Approximate placement: after line of argument/before discussion.

Discussion

These findings reveal that YMC and their families experience transition and transfer by “making sense” of the dynamic interplay between goals and expectations, changing relationships, and actions related to transition. Youth and their families are empowered to continue their transition journey if they achieve their goals and feel valued and respected. On the other hand, ineffective actions or negative interactions lead to youth and families experiencing uncertainty and inner turmoil. This whole experience is defined by the nature and process of transition, and influenced by a multitude of contextual factors.

Emotional needs

Transition is emotionally burdensome on youth and their families due to feelings of uncertainty and abandonment (construct 5) that result from the abrupt termination of services and relationships with providers (construct 2) [33], [35]. In an integrative review on the transition experiences of YMC, Joly [15] reports similar findings of youth and their families experiencing loss, abandonment, and uncertainty. Furthermore, while youth and families demonstrated resilience, perseverance, and skills in navigation and advocacy, parents also described increasing difficulty in managing ongoing care needs coupled with less energy as both the youth and parent got older [31], [32], [36]. To address the strong emotional component of transition, health care providers should assess and support the emotional needs of youth and their families, and begin planning for transfer well in advance to avoid eliciting feelings of sudden abandonment.

Transition is a journey

Schultz [35] p. 361] describes transition as being “sparked by a crisis”, and this finding is reflected across the included studies, which report age or funding as the primary agent for change or loss of services (construct 1). Joly [15] p. e93] compares the transition process to “being pushed off a cliff, falling into the abyss, and landing at the bottom”. This sense of crisis is likely due to health care providers’ focus on the one-off event of transfer, rather than a more gradual and holistic transition process. Health care providers should take the time to discuss with youth and their families how they envision their future (construct 3), instead of focusing solely on the transfer of services. Furthermore, we argue that transition should be conceptualized as a journey, rather than an event or outcome. Stewart et al. [38] describe this journey in three phases: the “preparation”, the “journey”, and the “landings” in the adult world. As a journey, transition should be defined by the youth and family’s preparation, readiness and adaptation to change, and eventual reintegration into a new phase of life.

The need for collaboration

While the experiences of youth and their families were mostly negative, there were reports of both positive and negative experiences related to transition planning in three of the included studies [28], [33], [37]. These positive experiences were associated with proactive planning by families and their providers, as well as availability and access to information and services, while negative experiences were associated with the opposite. These contrasting experiences illustrate the powerful impact that providers can make through actions such as communicating, collaborating, and providing information (construct 4). This highlights the importance of collaboration among stakeholders from both children’s and adult systems to prepare and support YMC and their families before, during, and after transition. This need for collaboration applies not only to YMC and their families, but to other youth with special health care needs as well [8].

Collaboration should extend beyond the domain of health services, as transition involves multiple sectors (construct 1). In a review of North American and European systems of care, Kraus de Camargo [39] describes the tendency of health and education services and policies to focus on their own issues, while social services focus more on the lives of citizens. Interestingly, studies in this meta-ethnography that examined transitions in multiple sectors [29], [30], [31], [33], [34], [37] reported similar findings to studies that examined only health services [28], [32], [35]. For example, issues that were common to health, education, and social services included: inadequate access to funding and services (e.g. adult health services, tuition support, options for independent living) [32], [33]; poor communication and collaboration [28], [37]; and lack of expertise among adult providers about complex pediatric conditions or programs and grants to support post-secondary students with “intensive” care needs [32], [33]. These similarities suggest that the three systems face common issues and could benefit from an integrated approach to transition. Other authors have made similar calls for active collaboration from all involved stakeholders [8], [40]. A multi-sectoral transition strategy should focus on building capacity among adult providers to meet the needs of YMC and their families entering the adult system, and supporting the social inclusion of YMC and their families [8].

What about youth development?

Lastly, the findings highlight that the bureaucratic processes related to health care transition (construct 1) are largely inflexible to youth development. In other words, the transfer from children’s to adult services typically happens at a predetermined chronological age, rather than based on youth developmental stage and needs. The included studies overwhelmingly describe youth and family perceptions of limitations of the adult health system. This is likely due to the predominant focus of adult health services on the sizable population of older adults, rather than on young adults with chronic conditions. For example, Cook [33] p. 6] describes how the “maintenance style” culture of extended care facilities limited young adults in achieving their developmental goals for independence. In Canada, pediatric health services often stop when the youth reaches a predetermined age, such as the age of majority. However, there are also many exceptions to this rule, further contributing to the messiness of transition. Furthermore, YMC may not be developmentally ready to transition to adulthood and adult services at this age, or may require a prolonged transition period. By prematurely placing these vulnerable youths into an adult system that is not designed or ready for them, they risk having their voices drowned out due to their relatively small numbers. Recognizing the need for a prolonged transition period, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended starting the transition process as early as age 12, and completing the process as late as age 26 [41]. As such, policy makers should consider flexible policies for age cutoffs related to pediatric health services and funding. This recommendation is not meant to simply delay the same issues; rather, it is meant to allow for additional time to plan for transition and offer increased flexibility for families.

Implications for practice, policy, and research

The conceptual model that we have proposed can be used as a framework to guide practice, policy, and research that aims to address the multidimensional and dynamic nature of transition. Service providers may want to focus on the inner constructs of the model (e.g. goals, relationships, actions), as they have limited control over the outer constructs (e.g. system factors and the nature and process of transition). On the other hand, policy-makers have more sway over these outer constructs, and less influence over individual interactions. Regardless of the area of focus, all users should consider the model in its entirety. For example, a health care provider may want to take actions to proactively address the changing relationships brought on by transition, but will need to consider these actions in relation to the youth and family’s goals and expectations, as well as the nature, process, and context of transition. Researchers can also use this model to examine relationships between specific constructs.

Based on our synthesis of youth and family experiences with transition, we suggest that providers: (1) begin planning for transfer early and link youth to adult health providers well before transfer; (2) ensure access to accurate and consistent information about services, supports and resources; and (3) communicate and collaborate with all involved stakeholders across agencies, sectors, and children’s and adult systems. Providers should also consider: (4) offering family-centred support services to address youth and family emotional needs and (5) discussing with youth and their families how they can be supported in realizing their visions for the future. Many of these suggestions are already embedded in published guidelines and position papers on health care transition [41], [42], and our findings echo previous reports of inconsistent implementation of evidence into practice [8]. However, there does appear to be some evidence of increased uptake over time. For example, while earlier studies mostly described poor youth and family experiences with service transfer [29], [30], [32], [35], more recent studies reported a mix of positive and negative experiences [28], [37], suggesting that providers are aware of current recommendations but are not consistently applying them. Transition planning is time-consuming and it is likely that the lack of time, resources, and incentives prevents providers from engaging in transition planning activities. Therefore, at the system level, policy makers should consider developing or improving existing policies to optimally support providers in implementing recommended practices, such as allocating dedicated resources for transition, rather than adding on to current provider workloads [37]. Policies should also focus on using incentives to drive system change, such as offering financial incentives or holding organizations accountable to quality standards for transition planning and continuity of care. Lastly, policy makers should consider adopting flexible age cutoffs for children’s services and funding – tailored to individual youth development and family needs – as well as supporting multi-sectoral strategies aimed at the social inclusion of YMC and their families and building capacity for adult providers to meet the needs of this population.

Areas for future research

The findings from this meta-ethnography provide several insights into areas for future research. While we sought to understand the experiences of YMC and their families, the only family participants in the included studies were the youth’s parents and/or family caregivers, 78% of which were female. There were no documented experiences of siblings, grandparents, or other family members. There was also a paucity of data on cultural influences on transition. Future research should seek the perspectives of fathers, siblings, and culturally diverse participants to better understand the impact of transition on diverse families. The findings also indicate that youth and their families have substantial unmet emotional needs. Further research is warranted to explore these needs and the best ways to address them. Additionally, while we identified a number of contextual factors that impact transition, we do not know how these factors interact to positively or negatively influence transition experiences. Future research that focuses on explicating these relationships has the potential to inform flexible interventions that bolster youth, family, and community strengths, and offer timely support for transition. Lastly, these implications for future research stem from a small selection of purposefully selected studies. A more exhaustive search and comprehensive mapping of the literature would more accurately identify the extent of current knowledge gaps.

Reflexivity, strengths, and limitations

Reflexivity

The review team consisted of interdisciplinary team members with clinical backgrounds in nursing (LL, MB, NC, JP, PS) and medicine (JWG). Three reviewers (LL, MB, JWG) have clinical and research expertise in working with CYMC and two reviewers (LL, JWG) have research interests in the transition to adulthood. Additionally, three reviewers (NC, JP, PS) are senior qualitative researchers. In particular, the analysis team (LL, MB, PS) has combined expertise in qualitative data analysis, CYMC, and transition to adulthood. The various backgrounds, disciplines, and perspectives brought by each team member influenced the interpretations, implications, and conclusions developed in this meta-ethnography.

Strengths

We consulted a health sciences librarian in developing the search strategy, which contributed to the methodological strength of this synthesis. Two reviewers (LL, MB) who had extensive nursing experience working with CYMC screened all records. This was another strength, as we were able to draw on clinical judgment to identify youth who fit the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, because the number of included studies was relatively small and manageable, we were able to become highly familiar with each study’s concepts, context, and conclusions, which allowed us to stay grounded in the data. Lastly, we followed a systematic approach and established reporting guidance in conducting and reporting this meta-ethnography.

Limitations

A limitation of this meta-ethnography is the inconsistency in how medical complexity has been defined in the literature. As a result, comprehensively searching for research related to this population proved to be challenging, despite having the guidance of a health sciences librarian. Additionally, our search did not include grey literature, which may have limited the identification of studies or dissertations relevant to the aim of this meta-ethnography. Furthermore, although we purposefully drew on clinical expertise to decrease the likelihood of incorrectly excluding studies, there remains the possibility that relevant studies on transition for youth with specific chronic health conditions were missed in either the search or screening phases.

Another limitation was the mixing of data types and perspectives that were external to the aim of our meta-ethnography. We wished to focus only on the interpretive accounts of youth and families; however, one study included mixed methods data [37] and three studies included service providers as participants (in addition to youth and families) [30], [34], [37]. To address these issues, we only included direct quotes from youth/family when analyzing first-order constructs, and we checked that second-order constructs from these studies were supported by first-order constructs. However, we recognize that the study authors’ interpretations (second-order constructs), and therefore our interpretations (third-order constructs), would inevitably be influenced by all data within a study. While the mixing of data types and perspectives posed a challenge to our analysis, we found that this “extra” information provided context and deeper insight into the experiences of YMC and their families.

Another limitation of this meta-ethnography is the descriptive nature of four of the studies, which may have limited the interpretive depth of the findings. For example, the construct of contextual factors is used to categorize, rather than explain the essence of the synthesized concepts. This was due to the majority of included studies describing factors as having a static relationship with transition (i.e. barriers and facilitators). Lastly, we propose that cultural factors may have a major influence on transition experiences, as adulthood is a social construct with a strong cultural component. However, only one study reported culture-based experiences with transition [34]. Therefore, this may be an important component that is currently missing from the model.

Conclusion

Meta-ethnography is a rigorous methodology for qualitative evidence synthesis and high quality meta-ethnographies have been used to inform evidence-based policy and practice [20]. Aligned with the aims and strengths of this methodology, we systematically identified, selected, and analyzed conceptual data from 10 primary studies on the experiences of YMC and their families with the transition to adulthood and transfer to adult services. Meta-ethnography also aims to deliver new insights and potentially generate theory on a topic [16], [20]. As such, we offer novel interpretations in the form of a conceptual model illustrating the dynamic interactions between six third-order constructs: the nature and process of transition, changing relationships, goals and expectations, actions related to transition, making sense of transition, and contextual factors impacting transition. Implications for how this conceptual model can be used to inform practice, policy, and research have been presented. Future work needs to focus on the bigger picture of transition by supporting youth and family goals for the future, addressing the emotional toll of transition on families, exploring the impact of transition on the whole family, and collaborating with stakeholders across sectors and systems.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Laura Banfield for her assistance in developing the search strategy. Dr. Gorter holds the Scotiabank Chair in Child Health Research.

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Research funding: Authors state no funding involved.

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

1. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Bhagat SK, Simon TD, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics 2011;127:529–38.10.1542/peds.2010-0910Search in Google Scholar

2. Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1463–70.10.1542/peds.2012-0175Search in Google Scholar

3. Bramlett MD, Read D, Bethell C, Blumberg SJ. Differentiating subgroups of children with special health care needs by health status and complexity of health care needs. Matern Child Health J 2009;13:151–63.10.1007/s10995-008-0339-zSearch in Google Scholar

4. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Feudtner C, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. J Am Med Assoc 2011;305:682–90.10.1001/jama.2011.122Search in Google Scholar

5. Miller AR, Condin CJ, McKellin WH, Shaw N, Klassen AF, Sheps S. Continuity of care for children with complex chronic health conditions: parents’ perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:242.10.1186/1472-6963-9-242Search in Google Scholar

6. Cohen E, Patel H. Responding to the rising number of children living with complex chronic conditions. Can Med Assoc J 2014;186:1199–200.10.1503/cmaj.141036Search in Google Scholar

7. Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, Jorissen TW, Okinow NA, Orr DP, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570–6.10.1016/1054-139X(93)90143-DSearch in Google Scholar

8. Gorter JW, Stewart D, Woodbury-Smith M. Youth in transition: care, health and development. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:757–63.10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01336.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Schall TE, Foster CC, Feudtner C. Safe work-hour standards for parents of children with medical complexity. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:7–8.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. McDaniel SH, Campbell TL, Hepworth J, Lorenz A. Family-oriented primary care. 2nd ed. New York: Springer, 2005. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/b137394.10.1007/b137394Search in Google Scholar

11. Prior M, McManus M, White P, Davidson L. Measuring the “Triple Aim” in transition care: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1648–61.10.1542/peds.2014-1704Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20.10.1258/1355819054308576Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Noyes J, Lewin S. Chapter 6: supplemental guidance on selecting a method of qualitative evidence synthesis, and integrating qualitative evidence with Cochrane intervention review. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, et al., editors. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, 2011. Available from: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance.Search in Google Scholar

14. Doug M, Adi Y, Williams J, Paul M, Kelly D, Petchey R, et al. Transition to adult services for children and young people with palliative care needs: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:78–84.10.1136/adc.2009.163931Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Joly E. Transition to adulthood for young people with medical complexity: an integrative literature review. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:e91–103.10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1988.10.4135/9781412985000Search in Google Scholar

17. Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:209–15.10.1258/135581902320432732Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. France EF, Uny I, Ring N, Turley RL, Maxwell M, Duncan EA, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:35.10.1186/s12874-019-0670-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, Walter F, Feder G, Ridd M, et al. “Medication career” or “Moral career”? the two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:154–68.10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, Uny I, Duncan EA, Jepson RG, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:1126–39.10.1111/jan.13809Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics 2002;110:1304–6.10.1542/peds.110.S3.1304Search in Google Scholar

22. Got Transition®. GotTransition.org. [cited 2019 Sep 15]; Available from: https://www.gottransition.org/.Search in Google Scholar

23. Major J, Stewart D, Amaria K, Nguyen T, Doig J, Adams S, et al. Care in the long term for youth and young adults with complex care needs. Ottawa: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

24. Lockwood C, Porrit K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. Chapter 2: systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global/.Search in Google Scholar

25. Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:179–87.10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Cahill M, Robinson K, Pettigrew J, Galvin R, Stanley M. Qualitative synthesis: a guide to conducting a meta-ethnography. Br J Occup Ther 2018;81:129–37.10.1177/0308022617745016Search in Google Scholar

27. Lindsay S, Hoffman A. A complex transition: lessons learned as three young adults with complex care needs transition from an inpatient paediatric hospital to adult community residences. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41:397–407.10.1111/cch.12203Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Dale CM, King J, Amin R, Katz S, McKim D, Road J, et al. Health transition experiences of Canadian ventilator-assisted adolescents and their family caregivers: a qualitative interview study. Paediatr Child Health 2017;22:277–81.10.1093/pch/pxx079Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Kirk S. Transitions in the lives of young people with complex healthcare needs. Child Care Health Dev 2008;34:567–75.10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00862.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Kirk S, Fraser C. Hospice support and the transition to adult services and adulthood for young people with life-limiting conditions and their families: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2014;28:342–52.10.1177/0269216313507626Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Kingsnorth S, Gall C, Beayni S, Rigby P. Parents as transition experts? qualitative findings from a pilot parent-led peer support group. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:833–40.10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01294.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Davies H, Rennick J, Majnemer A. Transition from pediatric to adult health care for young adults with neurological disorders: parental perspectives. Can J Neurosci Nurs 2011;33:32–9.Search in Google Scholar

33. Cook K, Siden H, Jack S, Thabane L, Browne G. Up against the system: a case study of young adult perspectives transitioning from pediatric palliative care. Nurs Res Pract 2013;2013:1–10.10.1155/2013/286751Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Rehm RS, Fuentes-Afflick E, Fisher LT, Chesla CA. Parent and youth priorities during the transition to adulthood for youth with special health care needs and developmental disability. Adv Nurs Sci 2012;35:E57–72.10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182626180Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Schultz RJ. Parental experiences transitioning their adolescent with epilepsy and cognitive impairments to adult health care. J Pediatr Health Care 2013;27:359–66.10.1016/j.pedhc.2012.03.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Magill-Evans J, Wiart L, Darrah J, Kratochvil M. Beginning the transition to adulthood: the experiences of six families with youths with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2005;25:19–36.10.1080/J006v25n03_03Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Kerr H, Price J, Nicholl H, O’Halloran P. Facilitating transition from children’s to adult services for young adults with life-limiting conditions (TASYL): programme theory developed from a mixed methods realist evaluation. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;86:125–38.10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.06.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Stewart D, Freeman M, Law M, Healy H, Burke-Gaffney J, Forhan M, et al. The best journey to adult life for youth with disabilities: an evidence-based model and best practice guidelines for the transition to adulthood for youth with disabilities. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

39. Kraus de Camargo O. Systems of care: transition from the bio-psycho-social perspective of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:792–9.10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01323.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Nguyen T, Stewart D, Gorter JW. Looking back to move forward: reflections and lessons learned about transitions to adulthood for youth with disabilities. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:83–8.10.1111/cch.12534Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. White PH, Cooley WC, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20182587.10.1542/9781610024310-part01-ch03Search in Google Scholar

42. Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centres (CAPHC), National Transitions Community of Practice. A guideline for transition from paediatric to adult health care for youth with special health care needs: a national approach. CAPHC 2016.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/jtm-2020-0002).

©2020 Lin Li, Marissa Bird, Nancy Carter, Jenny Ploeg, Jan Willem Gorter and Patricia H. Strachan, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- About evidence and personal experiences in transition

- Reviews

- Somatic outcomes of young people with chronic diseases participating in transition programs: a systematic review

- Transition readiness measures for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions: a systematic review

- Chronic illness and transition from paediatric to adult care: a systematic review of illness specific clinical guidelines for transition in chronic illnesses that require specialist to specialist transfer

- Experiences of youth with medical complexity and their families during the transition to adulthood: a meta-ethnography

- Psychosocial benefit and adherence of adolescents with chronic diseases participating in transition programs: a systematic review

- Original Articles

- Independence of young people with cerebral palsy during transition to adulthood: a population-based 3 year follow-up study

- Transition of adolescents with congenital heart disease from pediatric to adult congenital cardiac care: lessons from a retrospective cohort study

- Short Communication

- Transition Task Force: Early efforts towards comprehensive pediatric to adult transition services in an academic medical center

- Patient Report

- Making transition right for young patients and their families

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- About evidence and personal experiences in transition

- Reviews

- Somatic outcomes of young people with chronic diseases participating in transition programs: a systematic review

- Transition readiness measures for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions: a systematic review

- Chronic illness and transition from paediatric to adult care: a systematic review of illness specific clinical guidelines for transition in chronic illnesses that require specialist to specialist transfer

- Experiences of youth with medical complexity and their families during the transition to adulthood: a meta-ethnography

- Psychosocial benefit and adherence of adolescents with chronic diseases participating in transition programs: a systematic review

- Original Articles

- Independence of young people with cerebral palsy during transition to adulthood: a population-based 3 year follow-up study

- Transition of adolescents with congenital heart disease from pediatric to adult congenital cardiac care: lessons from a retrospective cohort study

- Short Communication

- Transition Task Force: Early efforts towards comprehensive pediatric to adult transition services in an academic medical center

- Patient Report

- Making transition right for young patients and their families