Abstract

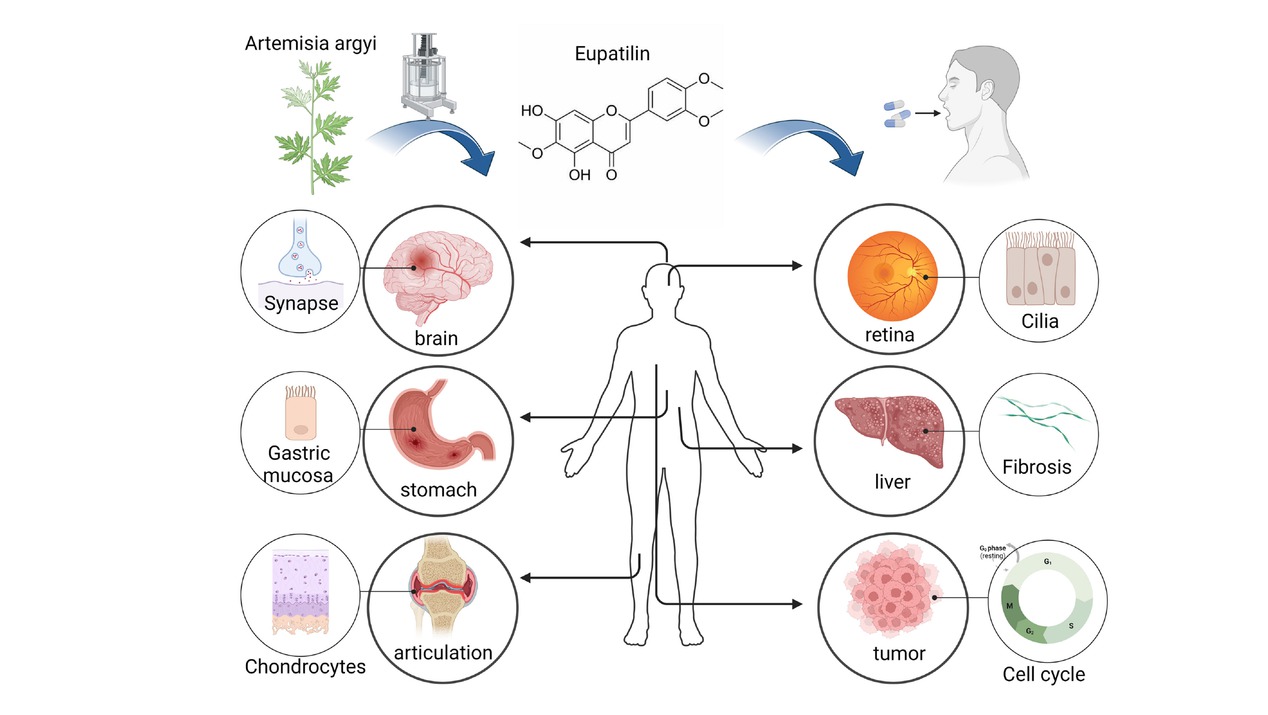

Eupatilin, a flavonoid found in Artemisia argyi (Compositae) leaves, exhibits robust anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumor properties. Numerous investigations have demonstrated remarkable efficacy of eupatilin across various disease models, spanning digestive, respiratory, nervous, and dermatological conditions. This review aims to provide an overview of recent studies elucidating the mechanistic actions of eupatilin across a spectrum of disease models and evaluate its clinical applicability. The findings herein provide valuable insights for advancing the study of novel Traditional Chinese Medicine compounds and their clinical utilization.

Introduction

Natural products (NPs) continue to exhibit value in medicine, serving not only as therapeutic agents but also as a pivotal source of innovative drug candidates.[1] The term “natural products” encompasses chemical compounds derived from living organisms, including plants, microorganisms, and marine life.[2] The historical utilization of plants for medicinal purposes has yielded numerous significant and effective drugs, spanning from early examples like quinine and morphine to more contemporary drugs such as paclitaxel (taxol), camptothecin and artemisinin.[3] In the context of modern medicine, there is a prevailing trend towards the extraction and pharmacological validation of active monomers from NPs, such as those found in traditional Chinese medicine, which plays a pivotal role in its continued advancement.[4,5]

Artemisia argyi (mugwort), a traditional Chinese herb with historical references dating back to the 11th-6th century B. C. in the Book of Songs, has been used for millennia in practices like moxibustion and the treatment of conditions including eczema, diarrhea, hemostasis, and menstruation-related symptoms.[6] Eupatilin, a main polyphenolic compound of Artemisia argyi, has garnered increasing attention from researchers since its isolation. Eupatilin is a lipophilic flavonoid constituent of the plant, appearing as a yellow powder with the molecular formula C18H16O7. Its chemical structure was first discovered in 1969[7] (Figure 1).

The therapeutic target of eupatilin. Eupatilin, derived from plants like mugwort, exhibits therapeutic potential across various organ systems, including the brain, stomach, joints, eyes, liver, and tumors. Its pharmacological actions encompass anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-proliferative effects, targeting specific cytokines and pathways associated with these conditions. (Created with Biorender. com, with permission.)

Eupatilin comprises various pharmaceutical formulations and derivatives. For instance, DA-9601 (Stillen®; Dong-A ST Co., Seoul, Korea), an immediate-release product derived from Artemisia asiatica, is employed to manage erosive gastritis.[8,9] The DA-5204 tablet (Stillen 2X®; Dong-A ST Co.) contains 90 mg of Artemisia asiatica extract derived from a 95% ethanol concentration, a novel formulation designed for extended intragastric retention of the active ingredient and is administered twice daily instead of thrice daily.[9] The efficacy of both DA-9601 and DA-5204 in treating erosive gastritis is comparable.[9,10] DA-6034, a synthetic derivative of eupatilin, exhibits high tolerability and minimal absorption in healthy volunteers. The localized contact with the gastrointestinal tract may render DA-6034 a promising option for non-systemic treatment of Irritable Bowel Disorder.[11]

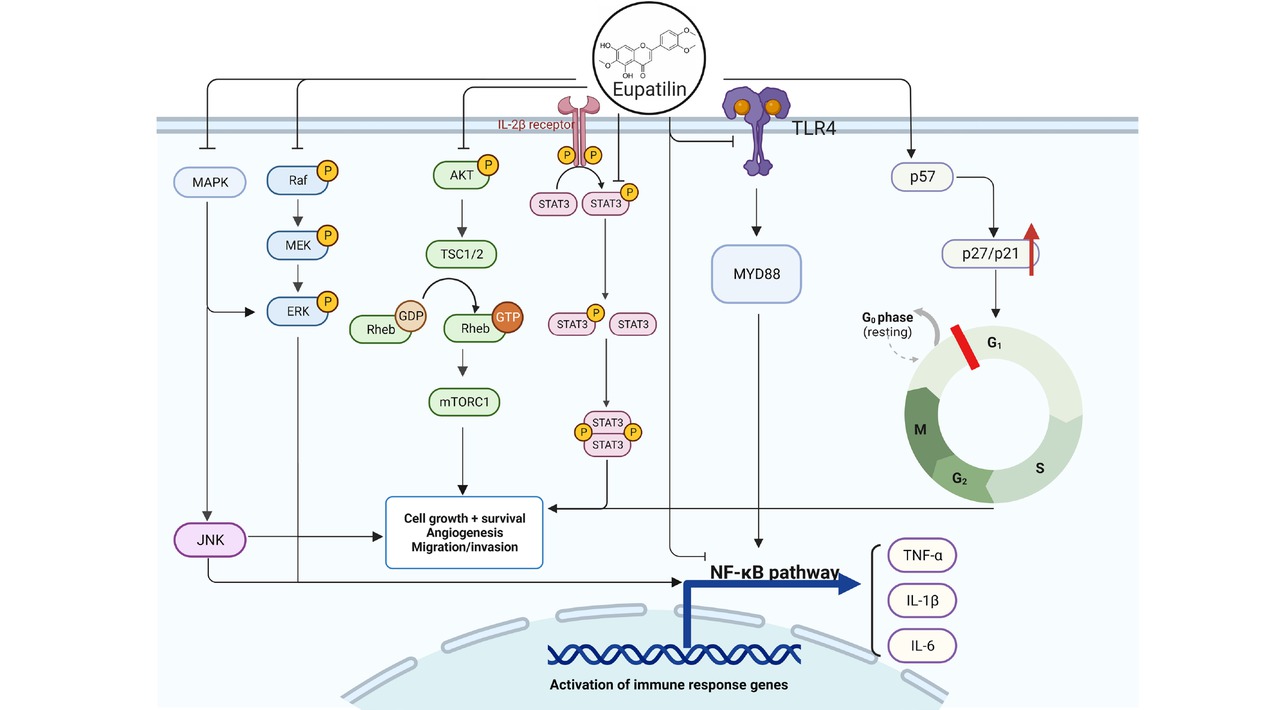

Eupatilin exhibits versatility in various significant pharmacological activities, with its anti-inflammatory properties being of particular interest (Figure 2). Currently, most marketed drugs featuring eupatilin are primarily prescribed for management of inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases.[8, 9, 10, 11, 12] Furthermore, its confirmed roles in autophagy, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis promotion have also sparked interest in its potential anti-tumor applications.[13,14] Additionally, for rare phenotypes such as ciliopathy-related phenotypes, eupatilin shows promising therapeutic potential.[15] In this review article, we will comprehensively assess the mechanisms of action, clinical research, and the potential applications of eupatilin.

The main mechanism of action of eupatilin. The anti-inflammatory effects of eupatilin primarily involve the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway, exerting a direct impact on NF-κB or indirectly suppressing NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) via TLR4, MAPK, and ERK cascade signaling. Simultaneously, eupatilin induces cell cycle arrest through PI3K-AKT, STAT3, p57, p27, p21 and other mechanisms to inhibit the growth and metastasis of cancer cells, showing anti-cancer properties. (Created with Biorender.com, with permission.)

Overview of anti-inflammatory effects and mechanisms of eupatilin

Eupatilin exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects primarily through modulation of the NF-κB pathway alongside the regulation of various signaling pathways and targets, including JAK2/STAT3, TLR4/MyD88, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT (Figure 2, Table 1). By inhibiting the activation of inflammatory pathways and reducing the production of inflammatory factors, it produces a broad, sustained and strong anti-inflammatory activity. These effects are achieved without substantially impacting physiological homeostasis, indicating a high safety profile.

Anti-inflammatory mechanism of eupatilin

| Diseases/Phenotype | Experimental model | Mechanisms/ Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic acinar cells | ↓PKD1/NF-κB ,IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2,CCL5 | ||

| Pancreatitis | In vitro | ↑ IL-4 ,IL-10 | Paik et al.,[27] |

| Intestinal epithelial (NCM460) cells | ↓NOX4 | ||

| In vitro | ↑AMPK | ||

| Ulcerative colitis | colitis mice | ameliorated the symptoms and pathologic changes (AMPK | Zhou et al.,[28] |

| in vivo | pharmacological inhibitor) | ||

| Esophagitis | Feline esophageal epithelial cells (EEC) | ↑HO-1,PI3K/Akt, ERK,Nrf2 | Song et al.,[29] |

| In vitro | translocation | ||

| ↑HSP27,HSP70 | Kim et al.,[30] | ||

| Acute Lung Injury | Rats (LPS-induced) | ↓SP-A, SP-D, IL-6,TNF-α,MCP-1 | Liu et al.,[16] |

| in vivo | ↑PPAR-α | ||

| Airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) | ↓TGF-β1,NF-κB,STAT3,AKT,ECM I,Coll I | ||

| Asthma | In vitro | ↑α-SMA, | Li et al.,[31] |

| Asthmatic mice(OVA-induced) | ↓NF-κB,MAPK,NO,IL-6,ROS | ||

| Asthma | in vivo | ↓Nrf2 | Bai et al.,[17] |

| Asthma | Guinea pig lung mast cells | ↓Syk tyrosine,Ca(2+) influx | Kim et al.,[32] |

| In vitro | |||

| Asthma | Human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) | ↓MAPK,IKK,NF-κB,eotaxin-1 (CCL11) | Jeon et al.,[33] |

| In vitro | |||

| Asthma | Human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) | ↓IκBα,NF-κB,phosphorylation of Akt | Jung et al.,[34] |

| In vitro | |||

| Cerebral ischemia | Mice( induced in mice by bilateral common carotid artery occlusion) | ↑Akt phosphorylation | Cai et al.,[35] |

| in vivo | |||

| Cerebral ischemia | BV2 microglia | ↓IKKα/β phosphorylation, IκBα | Sapkota et al.,[36] |

| In vitro | phosphorylation, and IκBα degradation | ||

| Glutamate | Rats(Glutamate Excitotoxicity Induced by KA ) | ↓P/Q-type Ca2+ channels,synapsin I | Lu et al.,[18] |

| neurotoxicity | in vivo | phosphorylation | |

| Intracranial | Erythrocyte lysis stimulation (ELS) to induce mouse microglia BV2 | ↓TLR4,MyD88 | Fei et al.,[19] |

| hemorrhage | In vitro | ||

| BV2 microglia | |||

| Subarachnoid | In vitro | ↓IL-1β,IL-6,TNF-α,MyD88,TLR4,and | Hong et al.,[20] |

| hemorrhage | Rats(intravascular perforation) | p-NF-κB p65 | |

| in vivo | |||

| Mice(MPTP) | ↓IκBα, IκBα,cell apoptosis | ||

| Parkinson | in vivo | ↑Akt,GSK-3βphosphorylation | Zhang et al.,[21] |

| Deep second-degree | Mice (mouse model of deep second degree burn) | ↑sestrin2,PI3K/AKT phosphorylation | Wang et al.,[22] |

| burn | in vivo | ||

| Acne | Human SZ95 sebocytes | Akt,PPARγ,SREBP-1 phosphorylation | Lee et al.,[37] |

| In vitro | ↓ | ||

| Dermatitis | HaCaT human epidermal keratinocytes | ↓NF-κB ,MAPK/AP-1,MMP-2/-9 | Jung et al.,[23] |

| In vitro | ↑PPARα | ||

| HaCaT cells | |||

| In vitro | ↓TNF-α,IL-6,IL-23,IL-17,p38 MAPK/ | ||

| Psoriasis | Mice(Imiquimod ) | NF-κB | Bai et al.,[38] |

| in vivo | |||

| Osteoarthritis | Chondrocytes of rats(chloroquine) in vivo | ↓↑mTOR sestrin2 | Lou et al.,[24] |

| Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice | |||

| Osteoarthritis | in vivo | IL-6 , IL-1β mRNAs | Kim et al.,[25] |

| human rheumatoid synoviocytes | ↓ | ||

| In vitro | |||

| Rats(monosodium iodoacetate) | IL-1β,IL-6,iNOS;MMP-3,MMP-↓ | ||

| Osteoarthritis | in vivo | 13,ADAMTS-5 mRNA,JNK | Jeong et al.,[39] |

| human OA chondrocytes | phosphorylation | ||

| In vitro | |||

| Osteoporosis | Rat cartilage cells | c-Fos,NFATc1 transcriptional inhibition | Kim et al.,[40] |

| In vitro | |||

| Fracture Healing | MC3T3-E1 cells | ↓NF-κB | Sun et al.,[26] |

| In vitro | ↑Hsa_circ_0045714,PI3K/AKT |

Eupatilin demonstrates broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effect in various anatomical regions, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, brain, skin, bones, and joints (Figure 1). It serves as the key component in “Stillen®”, a gastroprotective medication manufactured in Korea, recognized for its potent inflammation-reducing and cytoprotective attributes.[12] Notably, eupatilin demonstrates exceptional efficacy in inhibiting contraction of gastrointestinal smooth muscle and increasing the secretion of mucus and prostaglandins (PG) in the gastric mucosa, making it a promising candidate for the development of gastrointestinal therapeutics.[9, 10, 11, 12] Eupatilin exhibits potent and long-lasting anti-inflammatory effects, significantly impacting acute and chronic respiratory inflammation. It effectively suppresses inflammatory pathway activation and secretion of inflammatory factors in airway smooth muscle and bronchial epithelial cells, alleviating airway remodeling and allergic responses.[16,17] As a potential neuroprotective agent, eupatilin regulates microglia, glutamatergic synaptic protein and TLR4, and has shown great therapeutic potential especially in ischemic stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, acute and chronic brain injury, and Parkinson’s disease.[18, 19, 20, 21] As a small molecule agonist of sestrin2, eupatilin promotes the phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT pathway, the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes and re-epithelialization through sestrin2, which plays a key role in the wound repair of deep second-degree burn.[22] In addition, eupatilin inhibits NF-κB and MAPK/AP-1 pathway through PPARα, thus inhibiting MMP-2/-9 expression induced by TNFα, which plays a role in preventing skin aging.[23] Eupatilin exhibits diverse effects on cartilage, including anti-inflammatory action, inhibition of apoptosis and promotion of autophagy, and promotion of chondrogenesis, warranting further investigation[24, 25, 26] (Figure 2).

The role of eupatilin in gastrointestinal inflammation

In the digestive system, eupatilin mainly targets mucosal cells and protects gastrointestinal mucosa by inhibiting NF-κB pathway, reducing the expression of inflammatory factors and activating inflammatory pathways. Also, eupatilin increase the expression of mucosal and gastrointestinal protective factors. For example, Paik et al. demonstrated that eupatilin effectively inhibits PKD1/NF-κB activation and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB in pancreatic acinocytes. This results in the downregulation of pancreatitis-induced IL-1β, IL-6, CC chemokine ligands 2 and 5, while upregulating the expression of anti-inflammatory factors IL-4 and IL-10. This consequently leads to a reduction in inflammation levels in pancreatitis models.[27] Du et al. showed that eupatilin could increase the levels of superoxide dismutase, glutathione and IL-10, and decrease the contents of malondialdehyde, tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1β and IL-6. Significantly down-regulated the expression of NF-κB signal pathway, thus reducing the inflammatory response.[28]

Moreover, eupatilin exhibits a pronounced cytoprotective effect on mucous membranes. Zhou et al. reported that eupatilin significantly stabilizes colonic epithelial cells by downregulating the overexpression of tight junction proteins and NOX4. Additionally, it promotes AMPK activation in damaged intestinal epithelial cells stimulated by TNF-α. These actions contribute to improved colitis in mice by inhibiting inflammation and preserving intestinal integrity.[29] The mucosal protection provided by eupatilin is particularly effective in cases of mucosal injury resulting from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Song et al. confirmed that heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) inhibitor ZnPP inhibited eupatilin-induced HO-1 activity and showed the protective effect of eupatilin on indomethacin-induced cell injury. HO-1 is partly responsible for the eupatilin-mediated protective effect of esophageal epithelial cells on indomethacin through extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) and PI3K/Akt pathways and Nrf2 translocation.[30] Furthermore, Kim et al. identified that eupatilin upregulates heat shock proteins HSP27 and HSP70 to protect cultured cat food duct epithelial cells from indomethacin-induced damage. They characterized the signaling pathways regulated by HSP27 and HSP70, which may involve the activation of PTK, PKC, PLC, p38MAPK, JNKs, and PI3K.[31] Eupatilin could serve as an alternative or complementary option to NSAIDs to prevent NSAID-induced mucosal damage.

The role of eupatilin in respiratory inflammation

Eupatilin has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in the management of acute lung injury, acute and chronic respiratory inflammation, such as asthma. For instance, Liu et al. reported that eupatilin reduces levels of surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D, as well as inflammatory factors IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemotactic protein MCP-1, and reversed the production of nitric oxide (NO), malondialdehyde (MDA), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity induced by oxidative stress in rat models of acute lung injury. This effect may be closely associated with the activation of PPAR-α, thereby mitigating lung injury.[16] Bai et al. demonstrated that eupatilin alleviates ovalbumin-induced asthma in mice by modulating NF-κB, MAPK, and Nrf2 signaling pathways. In vivo, eupatilin inhibits the activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways and increases the expression of Nrf2. In vitro, eupatilin significantly reduces LPS-stimulated production of NO, IL-6, and reactive oxygen species (ROS).[17] Li et al revealed that eupatilin inhibits transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)-induced proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs). Exposure of ASMCs to eupatilin increased the expression of contractile markers smooth muscle α-actin (α-SMA) and myocardin, whereas the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins collagen type I (CollI) and fibronectin was reduced. Furthermore, eupatilin treatment reversed the activation of NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and AKT pathways in ASMCs induced by TGF-β1. These findings suggest that eupatilin may alleviate airway remodeling by regulating the phenotypic plasticity of ASMCs.[32] Kim et al. found that eupatilin initially inhibits Syk kinase and subsequently blocks multiple downstream signaling pathways and Ca2+ influx during mast cell activation triggered by specific antigen-antibody responses, thereby ameliorating allergic and inflammatory responses.[33] Moreover, Jeon et al. observed that eupatilin suppresses the signaling of MAPK, IKK, NF-κB, and eotaxin-1 in bronchial epithelial cells, consequently inhibiting eosinophilic migration and reducing asthma-related inflammation.[34] Jung et al. demonstrated that eupatilin significantly inhibits the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) in a dose-dependent manner, while inhibiting the activation of IκBα and nuclear factor-κB signaling and the phosphorylation of Akt action ultimately inhibits the adhesion of inflammatory cells to epithelial cells.[35] In conclusion, eupatilin may act as an anti-inflammatory agent exerting a significant therapeutic effect in the treatment of asthma. Eupatilin plays a crucial role in preventing inflammatory cell infiltration and reducing airway remodeling by providing anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, offering a valuable adjunctive treatment option for asthma patients.

The role of eupatilin in nervous system inflammation

Eupatilin exerts its neuroprotective effect mainly by regulating the inflammatory pathways of neurons and microglia, such as NF-κB, TLR4 and AKT. Cai et al. reported that eupatilin mitigates neuronal damage resulting from global cerebral ischemia, with its neuroprotective effect potentially attributed to increased Akt phosphorylation.[36] Sapkota et al. observed that eupatilin inhibits NF-κB signaling in ischemic brain by suppressing phosphorylation and degradation of IKKα/β and IκBα, thus reducing microglial activation and countering focal cerebral ischemia.[37] Lu et al. demonstrated that eupatilin reduces glutamate exocytosis in cerebral cortex synaptosomes by diminishing phosphorylation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels and synapsin protein I, thereby alleviating glutamate excitatory toxicity, eupatilin may be considered as a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment of brain damage associated with glutamate excitotoxicity.[18] Fei et al. determined the therapeutic potential of eupatilin on inflammation caused by intracerebral hemorrhage, indicating that TLR4/MyD88 pathway is involved in anti-inflammation and reducing cell edema and death, which provides hope for the improvement and prognosis of brain edema caused by inflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage.[19] Huang et al. further elucidated the role of eupatilin in improving early brain injury induced by subarachnoid hemorrhage in a rat model by modulating the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway.[20] Additionally, Zhang et al. revealed that eupatilin improved the Parkinson’s disease (PD) behavioral disorders caused by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and inhibited the expression of inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Further research results showed that Eupatilin eliminated the MPTP-induced downregulation of IκBα expression and the accumulation of p65 in the nuclear compartment, restored the phosphorylation of Akt and GSK-3β, and played an inhibitory role in inflammation and apoptosis.[21]

The role of eupatilin in cutaneous inflammation

Eupatilin demonstrates efficacy in skin inflammation-related diseases. Wang et al. reported that eupatilin activates Sestrin2 (SESN2), facilitating re-epithelialization of burn wounds through the PI3K/AKT pathway and promoting deep second-degree burn wound healing. Notably, eupatilin is the most specific and effective SESN2 activator, making it a promising compound for deep second-degree burn wound treatment.[22] Acne, characterized by inflammation of the hair follicle sebaceous gland unit, is another condition where eupatilin shows promise. Lee et al. revealed that eupatilin inhibits IGF-I-induced sebum cell adipogenesis by suppressing Akt phosphorylation, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), and mature SREBP-1. Furthermore, eupatilin downregulates TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA expression in sebum cells at the transcriptional level, suggesting its potential as an acne treatment.[38] Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are key proteins in skin damage and aging. Jung et al. demonstrated that eupatilin inhibits NF-κB and MAPK/AP-1 pathway through PPARα, thus inhibiting MMP-2/-9 expression induced by TNF-α and preventing skin aging.[23] Bai et al. revealed that eupatilin inhibits mouse keratinocyte proliferation via the p38MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. In a psoriasis model, eupatilin significantly reduces skin erythema, scales and thickness scores, improves skin histopathological lesions, and reduces serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17, indicating its therapeutic potential.[39]

The role of eupatilin in osteoarthritis

Cartilage degradation is a hallmark of osteoarthritis (OA). Increasing evidence links chondrocyte apoptosis and autophagy to cartilage degeneration. Lou et al. demonstrated that eupatilin protects chondrocytes by suppressing IL-1β-induced apoptosis via Sestrin2-dependent autophagy.[24] Kim et al. also observed the ability of eupatilin to reduce inflammatory cytokine expression, inhibit osteoclast differentiation, and ameliorate OA symptoms.[25] Jeong et al. reported the role of eupatilin in reducing IL-1β, IL-6, nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression, and phosphorylated JNK in cartilage. Eupatilin exhibits potential as an OA therapeutic by mitigating oxidative damage and enhancing extracellular matrix production in chondrocytes.[40] Furthermore, eupatilin potently inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclast formation, accompanied by suppressed phosphorylation of Akt, GSK3β, ERK, and IκB, and downregulation of c-Fos and NFATc1. It also disrupts the actin ring in multinucleated osteoclasts, halting bone resorption and inducing a fibroblast-like transformation. In LPS-induced osteoporotic mice and ovariectomized (OVX) mice, Eupatilin prevents bone loss and shows osteoprotective effects, highlighting its potential as a multifaceted therapeutic intervention for osteoporosis.[41] The anti-inflammatory effect of eupatilin also supports fracture healing, stimulating NF-κB blockage, PI3K/AKT activation, and Hsa_circ_0045714 production, enhancing osteoblast survival, proliferation, and migration.[26] The multifaceted effects of eupatilin on cartilage include inflammation inhibition, apoptosis and autophagy suppression, and chondrogenesis promotion, warranting further investigation.

Overview of anti-tumor effects and mechanisms of eupatilin

Eupatilin elicits anti-tumor effects predominantly through inducing cell cycle arrest, suppressing proliferation and migration, inhibiting angiogenesis, and promoting apoptosis in tumor cells. Through a multifaceted targeting strategy, eupatilin selectively acts on key molecular components involved in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), cyclin, ERK, among others, effectively attenuating tumor progression at various stages. The implicated pathways align with those associated with inflammatory conditions, including NF-κB/PI3K/AKT/MAPK (Figure 2, Table 2). Notably, the anti-tumor investigations of eupatilin primarily examine gastrointestinal malignancies, with a specific focus on stomach and colon cancers. Additionally, research has explored its effects on ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, prostate cancer, gliomas, and various other tumor types. These findings suggest that eupatilin exhibits a broad-spectrum antitumor activity, indicating its potential as an adjunct therapeutic option for diverse malignancies.

The role of eupatilin in digestive system tumors

Eupatilin exhibits potential in the treatment of gastrointestinal malignancies including gastric, liver, and esophageal cancers. Research by Kim et al. demonstrated that eupatilin effectively induces apoptosis in gastric cancer (AGS) cells, as evidenced by a reduction in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, activation of caspase-3, and cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). Additionally, it perturbs the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm), further indicating its apoptotic action. The compound also upregulates the expression of tumor suppressor proteins p53 and p21, while concurrently inhibiting the activation of extracellular ERK1/2 and Akt, which are integral to cell survival pathways. Collectively, these findings underscore the therapeutic potential of Eupatilin in gastric cancer treatment by modulating both apoptotic and cell survival signaling pathways.[42] Additionally, Choi et al. revealed that the anti-cancer effects of eupatilin extend beyond apoptosis, as it induces G(1) phase cell cycle arrest in AGS cells via ERK cascade signaling. This results in morphological changes in AGS cells, including increased cell size, particle size, and mitochondrial mass, along with the promotion of cell differentiation and cell cycle alteration.[43] Park et al. found that eupatilin inhibits MKN-1 gastric cancer cell proliferation by activating caspase-3 and suppresses the metastatic potential of gastric cancer cells by downregulating NF-κB activity and then reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated MMP expression.[44] Cheong et al. also discovered that Eupatilin inhibits gastric cancer cell growth by blocking STAT3-mediated VEGF expression, thereby disrupting the signaling pathways essential for tumor angiogenesis and proliferation.[45] This angiogenesis and tumor metastasis inhibition capability extends to liver cancer, with studies showing the capacity of eupatilin to reduce MMP-2 and VEGF-mediated metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma.[46] In other digestive system tumor studies, eupatilin is highlighted for its anti-proliferative properties, stagnant cell cycle regulation, and pro-apoptotic mechanisms. For instance, Wang et al. discovered that eupatilin treatment in a human esophageal cancer TE1 xenograft mouse model reduces tumor volume and inhibits phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 in tumor tissues, suggesting that eupatilin may play a role in suppressing TE1 cell proliferation through Akt/GSK3β and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways.[47] Park et al. found that EPT suppresses pancreatic cancer cell viability by inhibiting glucose uptake, activating AMPK, and inducing cell cycle arrest.[48] Similarly, Lee et al. demonstrated that eupatilin inhibited colon cancer cell viability, induced apoptosis with mitochondrial depolarization, and triggered oxidative stress. It modulated proteins involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy and targets the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways. Additionally, eupatilin synergizes with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in 5-FU-resistant HCT116 cells, suggesting its potential as an adjuvant to potentiate the effects of traditional chemotherapy in colon cancer.[49] In conclusion, eupatilin demonstrates a wide range of antitumor activities, including apoptosis promotion, differentiation induction, anti-proliferation, and cell cycle regulation.

The role of eupatilin in gynecological tumors

Eupatilin showed potential to treat a variety of gynecological tumors, including cervical cancer, endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer. Wu et al. illustrated that eupatilin regulates cervical cancer proliferation and cell cycle progression by modulating the hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway.[50] Cho et al. revealed that eupatilin upregulates p21 expression by inhibiting mutant p53 and activating the ATM/Chk2/Cdc25C/Cdc2 checkpoint pathway, leading to G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and inhibition of human endometrial cancer cell growth.[51] Lee et al. demonstrated that eupatilin enhances the therapeutic effects of conventional chemotherapeutic agents on ovarian cancer cells. The therapeutic effect of eupatilin is associated with caspase activation, cell cycle arrest, increased production of ROS, calcium influx, disruption of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondrial axis, SERPINB11 inhibition, and downregulation of phosphoinositol, ultimately promoting apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells.[52] Eupatilin downregulates key cell cycle regulators, including cyclin D1, cyclin B1, Cdk2, and Cdc2, leading to cell cycle arrest and inhibiting the proliferation of H-ras-transformed breast epithelial (MCF10A-ras) cells related to ERK1/2 pathway inhibition.[53] Research on the application of eupatilin in gynecological tumors primarily centers on its ability to induce cell cycle arrest, resulting in decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis.

The role of eupatilin in urinary system tumors

Eupatilin has a significant anti-tumor effect on prostate cancer cells. By up-regulating caspase3, Bax and cytochrome c, it reduces the viability of prostate cancer cells, induces apoptosis, and regulates the cell cycle by up-regulating p53, p21 and p27, making the cell cycle stagnant in G1 phase. In addition, eupatilin inhibits cell migration and invasion by down-regulating Twist, Slug and MMP-2-7, while increasing the expression of tumor suppressor PTEN and reducing transcription factor NF-κB. These findings suggest that zupatiline has a strong potential as a therapeutic drug for prostate cancer and further in vivo studies are needed to support its clinical application.[54] Eupatilin inhibited the expression of miR-21, which in turn mediated its effects on promoting apoptosis and inhibiting migration by targeting YAP1 in renal cancer cells. These findings suggested that Eupatilin might be an effective therapeutic agent for renal cell carcinoma.[55] Zhong et al. found that eupatilin inhibits and induces apoptosis in human RCC cells via ROS-mediated activation of the MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Consequently, eupatilin may serve as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of human RCC.[56] Considering the detriments of drug toxicity and side effects in urinary system tumors, eupatilin, a natural flavonoid, demonstrates minimal toxicity, high safety, and efficacy, thereby presenting considerable clinical applicability. The anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative stress properties of eupatilin complement its anti-tumor effects, showcasing distinctive advantages in urinary system tumor treatment. Further research and clarification of relevant mechanisms is warranted for clinical implementation.

Anticancer mechanism of eupatilin

| Diseases/Phenotype | Experimental model | Mechanisms/ Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) | Apoptosis-promoting | ||

| Gastric cancer | cells | ↓Bax/Bcl-2,ERK1/2,Akt | Kim et al.,[41] |

| in vitro | ↑p53,p21 | ||

| Human gastric epithelial AGS cells | Cell cycle arrest | ||

| Gastric cancer | in vitro | TFF1,p21 ↑ZO-1 redistribution,ERK cascades | Choi et al.,[42] |

| Gastric cancer | Human gastric cancer cell line, MKN-1 | Anti-metastatic | Park al.,[43] |

| in vitro | ↑caspase-3 | et | |

| Gastric cancer | MKN45 cells | Inhibition of angiogenesis | Cheong al.,[44] |

| in vitro | ↓VEGF, ARNT and STAT3 | et | |

| Human umbilical vein vascular | Anti-metastatic | ||

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | endothelial cells (HUVECs) | ↓HIF-α,VEGF,phosphorylated Akt | Park et al.,[45] |

| in vitro | expression,MMP2 | ||

| Hepatocellular | Human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells | Inhibition of tumor proliferation | Liu al.,[46] |

| Carcinoma | in vitro | ↓p53,Topo II,bcl-2 | et |

| Human esophageal cancer cells | Cell cycle arrest | ||

| Esophageal Cancer | in vitro | Inhibition of tumor proliferation | Wang et al.,[47] |

| ↓phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 | |||

| MIA-PaCa2 cells | Cell cycle arrest | ||

| Pancreatic Cancer | in vitro | glucose uptake,Tap73 ↓ | Park et al.,[48] |

| ↑AMPK | |||

| Cancer cell lines, namely HCT116 and | Apoptosis-promoting | ||

| Colon Cancer | HT29 | ↓PI3K/AKT | Lee et al.,[49] |

| in vitro | ↑MAPK,The anticancer effect of 5-fluorouracil | ||

| Cervical cancer cell lines (C4-1, HeLa, | Apoptosis-promoting | ||

| Cervical Cancer | Caski, and Siha) and Ect1/E6E7 cells | Cell cycle arrest | Wu et al.,[50] |

| in vitro | ↓hedgehog pathway(PTCH, SMO, GLI) | ||

| Cell cycle arrest | |||

| Endometrial Cancer | Human endometrial cancer cells | mutant p53 ↓ | Cho et al.,[51] |

| in vitro | ↑p21 | ||

| Ovarian Cancer | Ovarian cancer cells | Apoptosis-promoting | 52] Lee et al.,[ |

| in vitro | ↓SERPINB11 | ||

| Breast Cancer | H-ras-transformed human breast epithelial (MCF10A-ras) cells | Cell cycle arrest | Kim et al.,[53] |

| in vitro | ↓cyclin D1, cyclin B1, Cdk2 and Cdc2 | ||

| Human prostate cancer PC3 and LNCaP | Anti-metastatic | ||

| Prostate Cancer | cells | Inhibition of tumor proliferation | Serttas al.,[54] |

| ↓NF-κB | et | ||

| in vitro | PTEN ↑ | ||

| 786-O cell | Apoptosis-promoting | ||

| Renal Cancer | in vitro | anti-metastatic | Zhong et al.,[55] |

| ↓miR-21 | |||

| Apoptosis-promoting | |||

| Renal Cancer | 786-O cell | PI3K/AKT ↓ | Zhong et al.,[56] |

| in vitro | ↑MAPK | ||

| Cell cycle arrest | |||

| Glioma cell | anti-metastatic | ||

| Glioma | in vitro | Inhibition of tumor proliferation | Fei et al.,[57] |

| ↓P-LIMK/cofilin | |||

| F-actin depolymerization | |||

| The LN229 and U87MG human glioma | Anti-metastatic | ||

| Glioma | cell lines | Inhibition of tumor proliferation | Wang et al.,[58] |

| in vitro | ↓Notch-1 | ||

| Osteosarcoma | U- 2 OS cell in vitro | ↑Mitochondrial apoptosis pathway | Li et al.,[59] |

The role of eupatilin in other tumors

Eupatilin has shown promising aptitude for tumor prevention with diverse mechanisms of action, which brings hope to brain glioma patients. Fei et al. demonstrated that eupatilin significantly inhibits the viability and proliferation of glioma cells by arresting the cell cycle at the G1/S phase. Additionally, eupatilin disrupts the cytoskeleton structure and affects F-actin depolymerization through the P-LIMK/cofilin pathway, thereby inhibiting glioma migration. Eupatilin was also found to inhibit glioma invasion, potentially through the disruption of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its impact on the RECK/matrix metalloproteinase pathway. However, no apoptosis-promoting effect of eupatilin on glioma cells was observed.[57] Moreover, Wang et al. reported that eupatilin has an anticancer effect on glioma cells, inhibits the proliferation, invasion and migration of glioma cells by inhibiting the Notch-1 signaling pathway, and promotes their apoptosis.[58] Li et al. found that eupatilin can trigger the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, as manifested by enhanced Bax/B-cell lymphoma-2 ratio, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, cytochrome c release, caspase-3 and-9 activation, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage detected in U-2OS cells. These results suggest that eupatilin can inhibit U-2OS cancer cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis through the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway. Therefore, eupatilin may represent a novel anticancer drug for the treatment of osteosarcoma.[59] In short, eupatilin exhibits extensive and robust antitumor properties, acting on multiple targets to hinder tumor proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis.

Effects of eupatilin on other diseases

Ciliopathy frequency involves disfunction of retinal photoreceptors. Small molecule drugs targeting ciliary defects in ciliopathy are currently lacking. CEP290, a gene implicated in various ciliopathies, encodes for a protein that forms a complex with NPHP5, critical for the ciliary transition zone. Kim et al. demonstrated that eupatilin enhanced ciliogenesis and improved ciliary receptor delivery. In rd16 mice with Cep290 mutations leading to blindness, eupatilin treatment enhanced opsin transport to photoreceptor outer segments and improved retinal light response. The rescue effect is due to eupatilin-mediated inhibition of calmodulin binding to NPHP5, thereby promoting the recruitment of NPHP5 to the ciliary base.[60] Furthermore, Wiegering et al. identified eupatilin as a potential therapeutic agent for ciliosis associated with RPGRIP1L mutations.[61] Eupatilin modulates retinal organoid gene expression, targeting ciliary and synaptic plasticity pathways in CEP290 mutants.[62] Additionally, eupatilin exhibited promise in addressing proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Cinar et al. found that eupatilin reduced the proliferation and transformation of TGF-β2-induced retinal pigment epithelial cells.[63] Du et al. demonstrated that eupatilin mitigates oxidative stress and apoptosis by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway in ARPE-19 cells, suggesting its potential for preventing or treating proliferative vitreoretinopathy.[64]

Eupatilin demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in various metabolic disease models, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. Kang et al. observed that a 6-week eupatilin supplementation regimen significantly lowered fasting blood glucose levels, increased liver glycogen content, and enhanced both liver and plasma glucose metabolism, along with augmenting insulin secretion in type 2 diabetic mice.[65] Eupatilin exhibits the ability to mitigate hyperlipidemia by inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase, an enzyme targeted in hyperlipidemia therapy, as shown by Kim et al.[66] Furthermore, Kim et al. found that eupatilin significantly inhibited adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, reduced intracellular lipid accumulation in a concentration-dependent manner, and suppressed the expression of key adipogenic regulators, including PPARγ and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα). These findings suggest that eupatilin effectively inhibits 3T3-L1 cell differentiation and holds potential as a novel anti-obesity therapy.[67] Je et al. demonstrated that eupatilin modulates vasocontractile force, suggesting potential benefits in hypertension management. Interestingly, the mechanisms underlying the antihypertensive effects of eupatilin appear to involve endothelium-independent pathways, including the inhibition of Rho kinase and subsequent phosphorylation of MYPT1.[68]

Summary of the pharmacological potential of eupatilin

Eupatilin exhibits potent, broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects by regulating multiple signaling pathways, including JAK2/STAT3, TLR4/MyD88, PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and NF-κB, resulting in the inhibition of inflammation and the modulation of key inflammatory mediators.[17,20,22,70,71] It has been shown to reduce inflammation and epithelialmesenchymal transition in chronic rhinosinusitis, alleviate inflammation and coagulation in sepsis, improve lung injury, and protect against hepatocyte injury and hepatic steatosis.[16,65,70,71,72] These findings highlight versatility of eupatilin in managing inflammatory conditions and its potential as a therapeutic agent for various inflammation-related diseases.

The anti-tumor effects of eupatilin encompass cell cycle arrest, anti-proliferation, migration inhibition, angiogenesis suppression, and induction of tumor cell apoptosis. Furthermore, eupatilin demonstrates potential implications in cellular lipid metabolism, as indicated by studies investigating total lipid and fatty acid profiles.[73] Moreover, it exhibits additional anti-tumor properties, including the mitigation of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, protection against cochlear hair cell apoptosis, and augmentation of 5-FU efficacy in colon cancer treatment. These attributes position eupatilin as a promising adjunctive agent in cancer therapy, warranting further elucidation of its underlying mechanism of action. Eupatilin exhibits potential chemoprophylactic properties and cytotoxic effects.[49,74,75,76]

Eupatilin shows potential as a treatment for various challenging conditions, including mitigating MPTP-induced symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and dopaminergic neuron loss, addressing Cep290-related ciliopathies, reducing endometrial fibrosis, and inhibiting vocal cord fibrosis.[61,62,77,78,79] Its wide-reaching effects and low toxicity profile render it a promising therapeutic option for these rare and difficult-to-treat diseases.

Limitations of eupatilin related studies

Studies on eupatilin predominantly focus on cellular and murine models, with in vitro investigations outnumbering in vivo experiments. Large-scale clinical trial data is limited, and there is insufficient repeated validation across multiple disease models. Further research is essential to establish its clinical efficacy and evaluate potential adverse effects.[43,54,66,69,80,81,82] There is no standardized dosage regimen for eupatilin across various diseases and animal models. Cytotoxicity testing indicated negligible cytotoxic effects of eupatilin within the concentration range of 1–500 μmol/L.[33] In vitro studies employed concentration gradients of 1, 25, 50, and 100 μmol/L for 1–2 h or 1–2–48 h of incubation.[17,23,24,25,38,52] Experimental dosages in mice or rats ranged from 1 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg, with treatment duration varying depending on the disease model. Generally, the middle to high dose range exhibited superior therapeutic efficacy, yet the optimal dosage for each condition remains undetermined.[18,39,72]

Eupatilin exhibits a diverse array of mechanisms, making it challenging to identify the influence of alternative pathways on specific pathological processes. For instance, besides NF-κB, eupatilin may also impact the MAPK and AP-1 pathways, which could stimulate the production of inflammatory mediators.[83] Eupatilin can concurrently activate MAPK and NF-κB signaling, yet the modulation of these two pathways and the possibility of cross-effects require further investigation.[34] Eupatilin potentially exerts its influence through multiple pathways, including PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, MAPK, and Nrf2, which may exhibit cross-influencing effects.[70] Therefore, it is imperative to exclude these cross-effects and intensify targeted studies on eupatilin.

Prospects

Eupatilin is a highly regarded flavonoid that has the potential to fill the gaps in existing drug treatments due to its diverse and far-reaching health benefits. Its multi-target approach to inflammation stands out, engaging with complex biological pathways and regulating a variety of cellular and molecular targets, which sets it apart from conventional anti-inflammatory drugs. With a strong track record in reducing both acute and chronic inflammation across various body systems, eupatilin not only mitigates inflammation but also aids in the reversal of inflammatory processes, enhancing recovery and improving outcomes.[17,19,22,39,71]

The safety of eupatilin, evidenced by its minimal impact on physiological balance and its low side-effect profile, underscores its potential for broad clinical use.[21,25] In oncology, anti-tumor capabilities of eupatilin are remarkable, effectively targeting a spectrum of cancers through diverse mechanisms that include inhibiting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Its synergistic effect with chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin, by reducing their toxicity while enhancing the destruction of tumor tissue, highlights its potential to improve cancer treatment strategies.[74,75]

In addition, the ability of eupatilin induce tumor cell differentiation makes it a promising complementary anticancer therapy.[43] Its potential extends to treating rare and chronic conditions, suggesting that further research could unlock new clinical applications. The future of eupatilin looks bright, with its capacity to address unmet needs in medicine and contribute to the advancement of patient care.

Notably, current research on eupatilin primarily employs intravenous or intraperitoneal administration routes, both of which are systemic delivery methods. However, these systemic approaches may not achieve optimal dose-effect ratios for certain non-systemic diseases or localized manifestations of systemic diseases.[84,85] Consequently, there is a compelling rationale for developing or employing existing localized drug delivery systems to improve the administration of eupatilin. This strategy could be pivotal in expanding the therapeutic indications of eupatilin and enhancing its clinical efficacy. The potential of eupatilin can be significantly expanded through the incorporation of novel drug delivery systems, such as nanovesicles, hydrogels, and inflammation-responsive biomaterials.[86, 87, 88, 89] These advanced carriers play a crucial role in enhancing the targeted release of eupatilin at specific sites, increasing the effective drug concentration, and reducing systemic side effects. For instance, nanovesicles can encapsulate eupatilin, protecting it from degradation and facilitating its controlled release directly at the site of inflammation.[86,87] Hydrogels, with their unique ability to retain large amounts of water, can provide a sustained release of eupatilin, maintaining therapeutic levels over extended periods.[88] Furthermore, inflammation-responsive biomaterials can be engineered to release eupatilin in response to inflammatory stimuli, ensuring that the drug is delivered precisely when and where it is needed most.[89,90] This precision not only maximizes the therapeutic impact of eupatilin but also minimizes the risk of adverse reactions, thus enhancing its safety profile. By leveraging these innovative drug delivery technologies, the therapeutic applications of eupatilin could be broadened to include a wider range of inflammatory and tumor conditions, offering new hope for patients with complex and refractory diseases. As research progresses, these advanced delivery systems could pave the way for more effective and safer clinical applications of eupatilin, making it a versatile and valuable addition to modern pharmacotherapy.

Conclusions

Eupatilin, a flavonoid with diverse therapeutic potential, has been the subject of increasing research, particularly for its anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and cytoprotective properties. It offers a unique approach, differing from traditional single-target anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor drugs by engaging multiple pathways and regulating various targets. Eupatilin shows significant inhibitory effects on inflammation in multiple organ systems and has the potential to reverse the inflammatory process, improving recovery and prognosis. With a commendable safety profile and minimal side effects, it holds promise for the treatment of various tumors and rare diseases. However, challenges remain in terms of understanding its side effects, determining the therapeutic dose, and validating its efficacy in vivo. Despite these challenges, high safety profile and notable pharmacological effects of eupatilin suggest it has the potential to benefit a broader population in the future with further research.

Funding statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82201521, 81873359 and 82074519), The Fund of Key Laboratory of Advanced Materials of Ministry of Education (No. AdvMat-2023-19), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 7242187), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2022A1515011658, 2023A1515012235).

Acknowledgments

None.

-

Author Contributions

ZL, XW, KT, DH, JS conceived the article and wrote the manuscript. KT, DH, JS conducted language editing. QZ, WM and YH designed and oversighted the work, revised and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

-

Ethical Approval

No applicable.

-

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools

None declared.

-

Data Availability Statement

No additional data is available.

References

1 Atanasov AG, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Linder T, Wawrosch C, Uhrin P, et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol Adv 2015;33:1582–1614.10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2 Rasul A, Millimouno FM, Ali Eltayb W, Ali M, Li J, Li X. Pinocembrin: a novel natural compound with versatile pharmacological and biological activities. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:379850.10.1155/2013/379850Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3 Butler MS. Natural products to drugs: natural product-derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat Prod Rep 2008;25:475–516.10.1039/b514294fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Wang J, Hu J, Chen X, Lei X, Feng H, Wan F, et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine Monomers: Novel Strategy for Endogenous Neural Stem Cells Activation After Stroke. Front Cell Neurosci 2021;15:628115.10.3389/fncel.2021.628115Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5 Shen CY, Jiang JG, Yang L, Wang DW, Zhu W. Anti-ageing active ingredients from herbs and nutraceuticals used in traditional Chinese medicine: pharmacological mechanisms and implications for drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:1395–1425.10.1111/bph.13631Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Xiang F, Bai J, Tan X et al. Antimicrobial activities and mechanism of the essential oil from Artemisia argyi Levl. et Van. var. argyi cv. Qiai. Ind Crops Prod 2018;125:582–587.10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.09.048Search in Google Scholar

7 Kupchan SM, Sigel CW, Hemingway RJ, Knox JR, Udayamurthy MS. Tumor inhibitors. 33. Cytotoxic flavones from eupatorium species. Tetrahedron 1969;25:1603–1615.10.1016/S0040-4020(01)82733-2Search in Google Scholar

8 Seol SY, Kim MH, Ryu JS, Choi MG, Shin DW, Ahn BO. DA-9601 for erosive gastritis: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10:2379–2382.10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2379Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9 Choi YJ, Lee DH, Choi MG, Lee SJ, Kim SK, Song GA, et al. Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of DA-9601 versus Its New Formulation, DA-5204, in Patients with Gastritis: Phase III, Randomized, Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority Study. J Korean Med Sci 2017;32:1807–1813.10.3346/jkms.2017.32.11.1807Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10 Cho JH, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N, Lee DH. Efficacy of DA-5204 (Stillen 2X) for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e22729.10.1097/MD.0000000000022729Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11 Lee J, Shin KH, Kim JR, Lim KS, Jang IJ, Chung JY. Pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of DA-6034, an anti-inflammatory agent, after single and multiple oral administrations in healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Investig 2014;34:37–42.10.1007/s40261-013-0147-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12 Ryoo SB, Oh HK, Yu SA, Moon SH, Choe EK, Oh TY, et al. The effects of eupatilin (stillen®) on motility of human lower gastrointestinal tracts. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 2014;18:383–390.10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.5.383Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13 Choi EJ, Oh HM, Wee H, Choi CS, Choi SC, Kim KH, et al. Eupatilin exhibits a novel anti-tumor activity through the induction of cell cycle arrest and differentiation of gastric carcinoma AGS cells. Differentiation 2009;77:412–423.Search in Google Scholar

14 Zhong WF, Wang XH, Pan B, Li F, Kuang L, Su ZX. Eupatilin induces human renal cancer cell apoptosis via ROS-mediated MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Oncol Lett 2016;12:2894–2899.Search in Google Scholar

15 Kim YJ, Kim S, Jung Y, Jung E, Kwon HJ, Kim J. Eupatilin rescues ciliary transition zone defects to ameliorate ciliopathy-related phenotypes. J Clin Invest 2018;128:3642–3648. [PMID: 30035750 DOI: 10.1172/JCI99232]10.1172/JCI99232Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16 Liu H, Hao J, Wu C, Liu G, Wang X, Yu J, et al. Eupatilin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury by Inhibiting Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Med Sci Monit 2019;25:8289–8296.10.12659/MSM.917406Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Bai D, Sun T, Lu F, Shen Y, Zhang Y, Zhang B, et al. Eupatilin Suppresses OVA-Induced Asthma by Inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK and Activating Nrf2 Signaling Pathways in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:1582.10.3390/ijms23031582Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18 Lu CW, Wu CC, Chiu KM, Lee MY, Lin TY, Wang SJ. Inhibition of Synaptic Glutamate Exocytosis and Prevention of Glutamate Neurotoxicity by Eupatilin from Artemisia argyi in the Rat Cortex. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:13406.10.3390/ijms232113406Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19 Fei X, Chen C, Kai S, Fu X, Man W, Ding B, et al. Eupatilin attenuates the inflammatory response induced by intracerebral hemorrhage through the TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2019;76:105837.10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105837Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20 Hong Y, He S, Zou Q, Li C, Wang J, Chen R. Eupatilin alleviates inflammatory response after subarachnoid hemorrhage by inhibition of TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB axis. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2023;37:e23317.10.1002/jbt.23317Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21 Zhang Y, Qin L, Xie J, Li J, Wang C. Eupatilin prevents behavioral deficits and dopaminergic neuron degeneration in a Parkinson's disease mouse model. Life Sci 2020;253:117745.Search in Google Scholar

22 Wang K, Shen K, Han F, Bai X, Fang Z, Jia Y, et al. Activation of Sestrin2 accelerates deep second-degree burn wound healing through PI3K/AKT pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys 2023;743:109645.10.1016/j.abb.2023.109645Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23 Jung Y, Kim JC, Choi Y, Lee S, Kang KS, Kim YK, et al. Eupatilin with PPARα agonistic effects inhibits TNFα-induced MMP signaling in Ha-CaT cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;493:220–226.10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24 Lou Y, Wu J, Liang J, Yang C, Wang K, Wang J, et al. Eupatilin protects chondrocytes from apoptosis via activating sestrin2-dependent autophagy. Int Immunopharmacol 2019;75:105748.10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105748Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25 Kim J, Kim Y, Yi H, Jung H, Rim YA, Park N, et al. Eupatilin ameliorates collagen induced arthritis. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:233–239.10.3346/jkms.2015.30.3.233Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26 Sun Y, Ge J, Tang W, Hong H, Liu D, Lin J. Hsa_circ_0045714 induced by eupatilin has a potential to promote fracture healing. Biofactors 2021;47:376–385.10.1002/biof.1707Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Park WS, Paik K, Yang KJ, Kim JO. Eupatilin Ameliorates Cerulein-Induced Pancreatitis Via Inhibition of the Protein Kinase D1 Signaling Pathway In Vitro. Pancreas 2020;49:281–289.10.1097/MPA.0000000000001488Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28 Du K, Zheng C, Kuang Z, Sun Y, Wang Y, Li S, et al. Gastroprotective effect of eupatilin, a polymethoxyflavone from Artemisia argyi H.Lév. & Vaniot, in ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury via NF-κB signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2024;318:116986.10.1016/j.jep.2023.116986Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29 Zhou K, Cheng R, Liu B, Wang L, Xie H, Zhang C. Eupatilin ameliorates dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice partly through promoting AMPK activation. Phytomedicine 2018;46:46–56.10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Song HJ, Shin CY, Oh TY, Min YS, Park ES, Sohn UD. Eupatilin with heme oxygenase-1-inducing ability protects cultured feline esophageal epithelial cells from cell damage caused by indomethacin. Biol Pharm Bull 2009;32:589–596.10.1248/bpb.32.589Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31 Kim M, Min YS, Sohn UD. Cytoprotective effect of eupatilin against indomethacin-induced damage in feline esophageal epithelial cells: relevance of HSP27 and HSP70. Arch Pharm Res 2018;41:1019–1031.10.1007/s12272-018-1066-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Li Y, Ren R, Wang L, Peng K. Eupatilin alleviates airway remodeling via regulating phenotype plasticity of airway smooth muscle cells. Biosci Rep 2020;40:BSR20191445.10.1042/BSR20191445Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33 Kim JY, Kwon EY, Lee YS, Kim WB, Ro JY. Eupatilin blocks mediator release via tyrosine kinase inhibition in activated guinea pig lung mast cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2005;68:2063–2080.10.1080/15287390500177024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34 Jeon JI, Ko SH, Kim YJ, Choi SM, Kang KK, Kim H, et al. The flavone eupatilin inhibits eotaxin expression in an NF-κB-dependent and STAT6-independent manner. Scand J Immunol 2015;81:166–17610.1111/sji.12263Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35 Jung J, Ko SH, Yoo do Y, Lee JY, Kim YJ, Choi SM, et al. 5,7-Dihydroxy-3,4,6-trimethoxyflavone inhibits intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 via the Akt and nuclear factor-κB-dependent pathway, leading to suppression of adhesion of monocytes and eosinophils to bronchial epithelial cells. Immunology 2012;137:98–113.10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03618.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36 Cai M, Phan PT, Hong JG, Kim DH, Kim JM, Park SJ, et al. The neuroprotective effect of eupatilin against ischemia/reperfusion-induced delayed neuronal damage in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2012;689:104–110.10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.05.042Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37 Sapkota A, Gaire BP, Cho KS, Jeon SJ, Kwon OW, Jang DS, et al. Eupatilin exerts neuroprotective effects in mice with transient focal cerebral ischemia by reducing microglial activation. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171479.10.1371/journal.pone.0171479Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38 Lee JH, Lee YJ, Song JY, Kim YH, Lee JY, Zouboulis CC, et al. Effects of Eupatilin on Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1-Induced Lipogenesis and Inflammation of SZ95 Sebocytes. Ann Dermatol 2019;31:479–482.10.5021/ad.2019.31.4.479Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39 Bai D, Cheng X, Li Q, Zhang B, Zhang Y, Lu F, et al. Eupatilin inhibits keratinocyte proliferation and ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin lesions in mice via the p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2023;45:133–139.10.1080/08923973.2022.2121928Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40 Jeong JH, Moon SJ, Jhun JY, Yang EJ, Cho ML, Min JK. Eupatilin Exerts Antinociceptive and Chondroprotective Properties in a Rat Model of Osteoarthritis by Downregulating Oxidative Damage and Catabolic Activity in Chondrocytes. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130882.10.1371/journal.pone.0130882Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41 Kim JY, Lee MS, Baek JM, Park J, Youn BS, Oh J. Massive elimination of multinucleated osteoclasts by eupatilin is due to dual inhibition of transcription and cytoskeletal rearrangement. Bone Rep. 2015;3:83–94.10.1016/j.bonr.2015.10.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42 Kim MJ, Kim DH, Na HK, Oh TY, Shin CY, Surh Ph D Professor YJ. Eupatilin, a pharmacologically active flavone derived from Artemisia plants, induces apoptosis in human gastric cancer (AGS) cells. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 2005;24:261–269.10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.v24.i4.30Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43 Choi EJ, Oh HM, Wee H, Choi CS, Choi SC, Kim KH, et al. Eupatilin exhibits a novel anti-tumor activity through the induction of cell cycle arrest and differentiation of gastric carcinoma AGS cells. Differentiation 2009;77:412–423.10.1016/j.diff.2008.12.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44 Park BB, Yoon Js, Kim Es, Choi J, Won Yw, Choi Jh, et al. Inhibitory effects of eupatilin on tumor invasion of human gastric cancer MKN-1 cells. Tumour Biol 2013;34:875–885.10.1007/s13277-012-0621-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

45 Cheong JH, Hong SY, Zheng Y, Noh SH. Eupatilin Inhibits Gastric Cancer Cell Growth by Blocking STAT3-Mediated VEGF Expression. J Gastric Cancer 2011;11:16–22.10.5230/jgc.2011.11.1.16Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46 Park JY, Park DH, Jeon Y, Kim YJ, Lee J, Shin MS, et al. Eupatilin inhibits angiogenesis-mediated human hepatocellular metastasis by reducing MMP-2 and VEGF signaling. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2018;28:3150–3154.10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.08.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47 Wang X, Zhu Y, Zhu L, Chen X, Xu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Eupatilin inhibits the proliferation of human esophageal cancer TE1 cells by targeting the Akt‑GSK3β and MAPK/ERK signaling cascades. Oncol Rep 2018;39:2942–2950.10.3892/or.2018.6390Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48 Park TH, Kim HS. Eupatilin Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Cells via Glucose Uptake Inhibition, AMPK Activation, and Cell Cycle Arrest. Anticancer Res 2022;42:483–491.10.21873/anticanres.15506Search in Google Scholar PubMed

49 Lee M, Yang C, Song G, Lim W. Eupatilin Impacts on the Progression of Colon Cancer by Mitochondria Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:957.10.3390/antiox10060957Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50 Wu Z, Zou B, Zhang X, Peng X. Eupatilin regulates proliferation and cell cycle of cervical cancer by regulating hedgehog signalling pathway. Cell Biochem Funct 2020;38:428–435.10.1002/cbf.3493Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51 Cho JH, Lee JG, Yang YI, Kim JH, Ahn JH, Baek NI, et al. Eupatilin, a dietary flavonoid, induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in human endometrial cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol 2011;49:1737–1744.10.1016/j.fct.2011.04.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52 Lee JY, Bae H, Yang C, Park S, Youn BS, Kim HS, et al. Eupatilin Promotes Cell Death by Calcium Influx through ER-Mitochondria Axis with SERPINB11 Inhibition in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1459.Search in Google Scholar

53 Kim DH, Na HK, Oh TY, Kim WB, Surh YJ. Eupatilin, a pharmacologically active flavone derived from Artemisia plants, induces cell cycle arrest in ras-transformed human mammary epithelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2004;68:1081–1087.10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54 Serttas R, Koroglu C, Erdogan S. Eupatilin Inhibits the Proliferation and Migration of Prostate Cancer Cells through Modulation of PTEN and NF-κB Signaling. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2021;21:372–382.10.2174/1871520620666200811113549Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55 Zhong W, Wu Z, Chen N, Zhong K, Lin Y, Jiang H, et al. Eupatilin Inhibits Renal Cancer Growth by Downregulating MicroRNA-21 through the Activation of YAP1. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:5016483.10.1155/2019/5016483Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56 Zhong WF, Wang XH, Pan B, Li F, Kuang L, Su ZX. Eupatilin induces human renal cancer cell apoptosis via ROS-mediated MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Oncol Lett 2016;12:2894–2899.10.3892/ol.2016.4989Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57 Fei X, Wang J, Chen C, Ding B, Fu X, Chen W, et al. Eupatilin inhibits glioma proliferation, migration, and invasion by arresting cell cycle at G1/S phase and disrupting the cytoskeletal structure. Cancer Manag Res 2019;11:4781–4796.10.2147/CMAR.S207257Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58 Wang Y, Hou H, Li M, Yang Y, Sun L. Anticancer effect of eupatilin on glioma cells through inhibition of the Notch-1 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 2016;13:1141–1146.10.3892/mmr.2015.4671Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59 Li YY, Wu H, Dong YG, Lin BO, Xu G, Ma YB. Application of eupatilin in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Oncol Lett 2015;10:2505–2510.10.3892/ol.2015.3563Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60 Kim YJ, Kim S, Jung Y, Jung E, Kwon HJ, Kim J. Eupatilin rescues ciliary transition zone defects to ameliorate ciliopathy-related phenotypes. J Clin Invest 2018;128:3642–3648.10.1172/JCI99232Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61 Wiegering A, Dildrop R, Vesque C, Khanna H, Schneider-Maunoury S, Gerhardt C. Rpgrip1l controls ciliary gating by ensuring the proper amount of Cep290 at the vertebrate transition zone. Mol Biol Cell 2021;32:675–689.10.1091/mbc.E20-03-0190Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62 Corral-Serrano JC, Sladen PE, Ottaviani D, Rezek OF, Athanasiou D, Jovanovic K, et al. Eupatilin Improves Cilia Defects in Human CEP290 Ciliopathy Models. Cells 2023;12:1575.10.3390/cells12121575Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63 Cinar AK, Ozal SA, Serttas R, Erdogan S. Eupatilin attenuates TGF-β2-induced proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2021;40:103–114.10.1080/15569527.2021.1902343Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64 Du L, Chen J, Xing YQ. Eupatilin prevents H2O2-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2017;85:136–140.10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65 Kang YJ, Jung UJ, Lee MK, Kim HJ, Jeon SM, Park YB, et al. Eupatilin, isolated from Artemisia princeps Pampanini, enhances hepatic glucose metabolism and pancreatic beta-cell function in type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;82:25–32.10.1016/j.diabres.2008.06.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

66 Kim KJ, Kang NE, Oh YS, Jang SE. Eupatilin Alleviates Hyperlipidemia in Mice by Inhibiting HMG-CoA Reductase. Biochem Res Int 2023;2023:8488648.10.1155/2023/8488648Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67 Kim JS, Lee SG, Min K, Kwon TK, Kim HJ, Nam JO. Eupatilin inhibits adipogenesis through suppression of PPARγ activity in 3T3-L1 cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;103:135–139.10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.073Search in Google Scholar PubMed

68 Je HD, Kim HD, Jeong JH. The inhibitory effect of eupatilin on the agonist-induced regulation of vascular contractility. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 2013;17:31–36.10.4196/kjpp.2013.17.1.31Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69 Choi EJ, Lee S, Chae JR, Lee HS, Jun CD, Kim SH. Eupatilin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inflammatory mediators in macrophages. Life Sci 2011;88:1121–1126.10.1016/j.lfs.2011.04.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

70 Lu Y, Li D, Huang Y, Sun Y, Zhou H, Ye F, et al. Pretreatment with Eupatilin Attenuates Inflammation and Coagulation in Sepsis by Suppressing JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. J Inflamm Res 2023;16:1027–1042.10.2147/JIR.S393850Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71 Lee HY, Nam Y, Choi WS, Kim TW, Lee J, Sohn UD. The hepatoprotective effect of eupatilin on an alcoholic liver disease model of rats. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 2020;24:385–394.10.4196/kjpp.2020.24.5.385Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72 Su H, Zhao Y. Eupatilin alleviates inflammation and epithelial-tomesenchymal transition in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps by upregulating TFF1 and inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Histol Histopathol 2024;39:357–365.Search in Google Scholar

73 Rosa A, Isola R, Pollastro F, Caria P, Appendino G, Nieddu M. The dietary flavonoid eupatilin attenuates in vitro lipid peroxidation and targets lipid profile in cancer HeLa cells. Food Funct 2020;11:5179–5191.10.1039/D0FO00777CSearch in Google Scholar

74 Park JY, Lee D, Jang HJ, Jang DS, Kwon HC, Kim KH, et al. Protective Effect of Artemisia asiatica Extract and Its Active Compound Eupatilin against Cisplatin-Induced Renal Damage. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:483980.10.1155/2015/483980Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75 Lu X, Deng T, Dong H, Han J, Yu Y, Xiang D, et al. Novel Application of Eupatilin for Effectively Attenuating Cisplatin-Induced Auditory Hair Cell Death via Mitochondrial Apoptosis Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022;2022:1090034.10.1155/2022/1090034Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76 Seo HJ, Surh YJ. Eupatilin, a pharmacologically active flavone derived from Artemisia plants, induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Mutat Res 2001;496:191–198.10.1016/S1383-5718(01)00234-0Search in Google Scholar

77 Zhang Y, Qin L, Xie J, Li J, Wang C. Eupatilin prevents behavioral deficits and dopaminergic neuron degeneration in a Parkinson's disease mouse model. Life Sci 2020;253:117745.10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117745Search in Google Scholar PubMed

78 Lee CJ, Hong SH, Yoon MJ, Lee KA, Choi DH, Kwon H, et al. Eupatilin treatment inhibits transforming growth factor beta-induced endometrial fibrosis in vitro. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2020;47:108–113.10.5653/cerm.2019.03475Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

79 Park SJ, Choi H, Kim JH, Kim CS. Antifibrotic effects of eupatilin on TGF-β1-treated human vocal fold fibroblasts. PLoS One 2021;16:e0249041.10.1371/journal.pone.0249041Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80 Lee DC, Oh JM, Choi H, Kim SW, Kim SW, Kim BG, et al. Eupatilin Inhibits Reactive Oxygen Species Generation via Akt/NF-κB/MAPK Signaling Pathways in Particulate Matter-Exposed Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Toxics 2021;9:38.10.3390/toxics9020038Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

81 Lee JY, Bae H, Yang C, Park S, Youn BS, Kim HS, et al. Eupatilin Promotes Cell Death by Calcium Influx through ER-Mitochondria Axis with SERPINB11 Inhibition in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1459.10.3390/cancers12061459Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

82 Hu J, Liu Y, Pan Z, Huang X, Wang J, Cao W, et al. Eupatilin Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation by Suppressing β-catenin/PAI-1 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:5933.10.3390/ijms24065933Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

83 Kim JM, Lee DH, Kim JS, Lee JY, Park HG, Kim YJ, et al. 5,7-dihydroxy-3,4,6-trimethoxyflavone inhibits the inflammatory effects induced by Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin via dissociating the complex of heat shock protein 90 and I kappaB alpha and I kappaB kinase-gamma in intestinal epithelial cell culture. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;155:541–551.10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03849.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84 An X, Yang J, Cui X, Zhao J, Jiang C, Tang M, et al. Advances in local drug delivery technologies for improved rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2024;209:115325.10.1016/j.addr.2024.115325Search in Google Scholar PubMed

85 Wang W, Zhong Z, Huang Z, Hiew TN, Huang Y, Wu C, et al. Nano-medicines for targeted pulmonary delivery: receptor-mediated strategy and alternatives. Nanoscale 2024;16:2820–2833.10.1039/D3NR05487JSearch in Google Scholar

86 Hu Q, Zhang F, Wei Y, Liu J, Nie Y, Xie J, et al. Drug-Embedded Nanovesicles Assembled from Peptide-Decorated Hyaluronic Acid for Rheumatoid Arthritis Synergistic Therapy. Biomacromolecules 2023;24:3532–3544.10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00294Search in Google Scholar PubMed

87 Yang C, Xue Y, Duan Y, Mao C, Wan M. Extracellular vesicles and their engineering strategies, delivery systems, and biomedical applications. J Control Release 2024;365:1089–1123.10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.11.057Search in Google Scholar PubMed

88 Woodring RN, Gurysh EG, Bachelder EM, Ainslie KM. Drug Delivery Systems for Localized Cancer Combination Therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2023;6:934–950.10.1021/acsabm.2c00973Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

89 Wang Y, Li J, Tang M, Peng C, Wang G, Wang J, et al. Smart stimuli-responsive hydrogels for drug delivery in periodontitis treatment. Biomed Pharmacother 2023;162:114688.10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114688Search in Google Scholar PubMed

90 Tang S, Gao Y, Wang W, Wang Y, Liu P, Shou Z, et al. Self-Report Amphiphilic Polymer-Based Drug Delivery System with ROS-Triggered Drug Release for Osteoarthritis Therapy. ACS Macro Lett 2024;13:58–64.10.1021/acsmacrolett.3c00668Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 Zheng Li, Xiumei Wang, Ksenija Tasich, David Hike, Jackson G. Schumacher, Qingju Zhou, Weitao Man, Yong Huang, published by De Gruyter on behalf of the SMP

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Crosstalk between cardiac dysfunction and outcome of liver cirrhosis: Perspectives from evidence-based medicine and holistic integrative medicine

- Telemedicine strategies in older patients with cardiovascular diseases

- Clinical significance of portal vein thrombosis in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: A still matter of debate

- Review Article

- Eupatilin unveiled: An in-depth exploration of research advancements and clinical therapeutic prospects

- Original Article

- Benzo[b]fluoranthene is involved in idiopathic membranous nephropathy by inducing podocyte injury

- A novel and safe protocol for patients with severe comorbidity who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center prospective study

- Deciphering the role of ELAVL1: Insights from pan-cancer multiomics analyses with emphasis on nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Nano particle loaded EZH2 inhibitors: Increased efficiency and reduced toxicity for malignant solid tumors

- An automated human–machine interaction system enhances standardization, accuracy and efficiency in cardiovascular autonomic evaluation: A multicenter, open-label, paired design study

- Rapid Communication

- Comparison of predicting value of triglyceride‑glucose indices family in cardiovascular disease risk over time: Insights from a 9-year nationwide prospective cohort study

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Crosstalk between cardiac dysfunction and outcome of liver cirrhosis: Perspectives from evidence-based medicine and holistic integrative medicine

- Telemedicine strategies in older patients with cardiovascular diseases

- Clinical significance of portal vein thrombosis in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: A still matter of debate

- Review Article

- Eupatilin unveiled: An in-depth exploration of research advancements and clinical therapeutic prospects

- Original Article

- Benzo[b]fluoranthene is involved in idiopathic membranous nephropathy by inducing podocyte injury

- A novel and safe protocol for patients with severe comorbidity who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center prospective study

- Deciphering the role of ELAVL1: Insights from pan-cancer multiomics analyses with emphasis on nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Nano particle loaded EZH2 inhibitors: Increased efficiency and reduced toxicity for malignant solid tumors

- An automated human–machine interaction system enhances standardization, accuracy and efficiency in cardiovascular autonomic evaluation: A multicenter, open-label, paired design study

- Rapid Communication

- Comparison of predicting value of triglyceride‑glucose indices family in cardiovascular disease risk over time: Insights from a 9-year nationwide prospective cohort study