Carpal tunnel dimensions following osteopathic manipulation utilizing dorsal carpal arch muscle energy: a pilot study

Abstract

Context

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common entrapment neuropathy. When mild to moderate in severity, nonoperative treatments including osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) have been found to be effective. Studies have been carried out to quantify the mechanism of such treatments with cadaver studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound.

Objectives

This pilot project investigated the mechanism of a previously undescribed technique of nonoperative carpal tunnel treatment, dorsal carpal arch muscle energy (DCA-ME), which focuses on the dorsal arch (trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones) manipulating the bones to redome the arch, round the tunnel, and increase its volume. Although the actual effectiveness of such manipulation in the treatment of CTS can only be assessed and quantified in patients with the disorder, this initial study was carried out to see if it was feasible for physical changes following DCA-ME to be quantified with ultrasound.

Methods

A pilot study of 25 healthy volunteers with no prior history of CTS or related disorders was undertaken to quantify anatomical changes in carpal tunnel dimensions following OMT of the nondominant wrist, utilizing DCA-ME. The subjects were randomly assigned to either the OMT group (n=14) or the control group (n=11). The control group underwent a sham manipulation. Pre- and postultrasound measurements of carpal tunnel dimensions were made. The study employed a two-group, pre-/postmanipulation design to evaluate the anatomical changes resulting from the OMT manipulation compared to those following the control sham manipulation.

Results

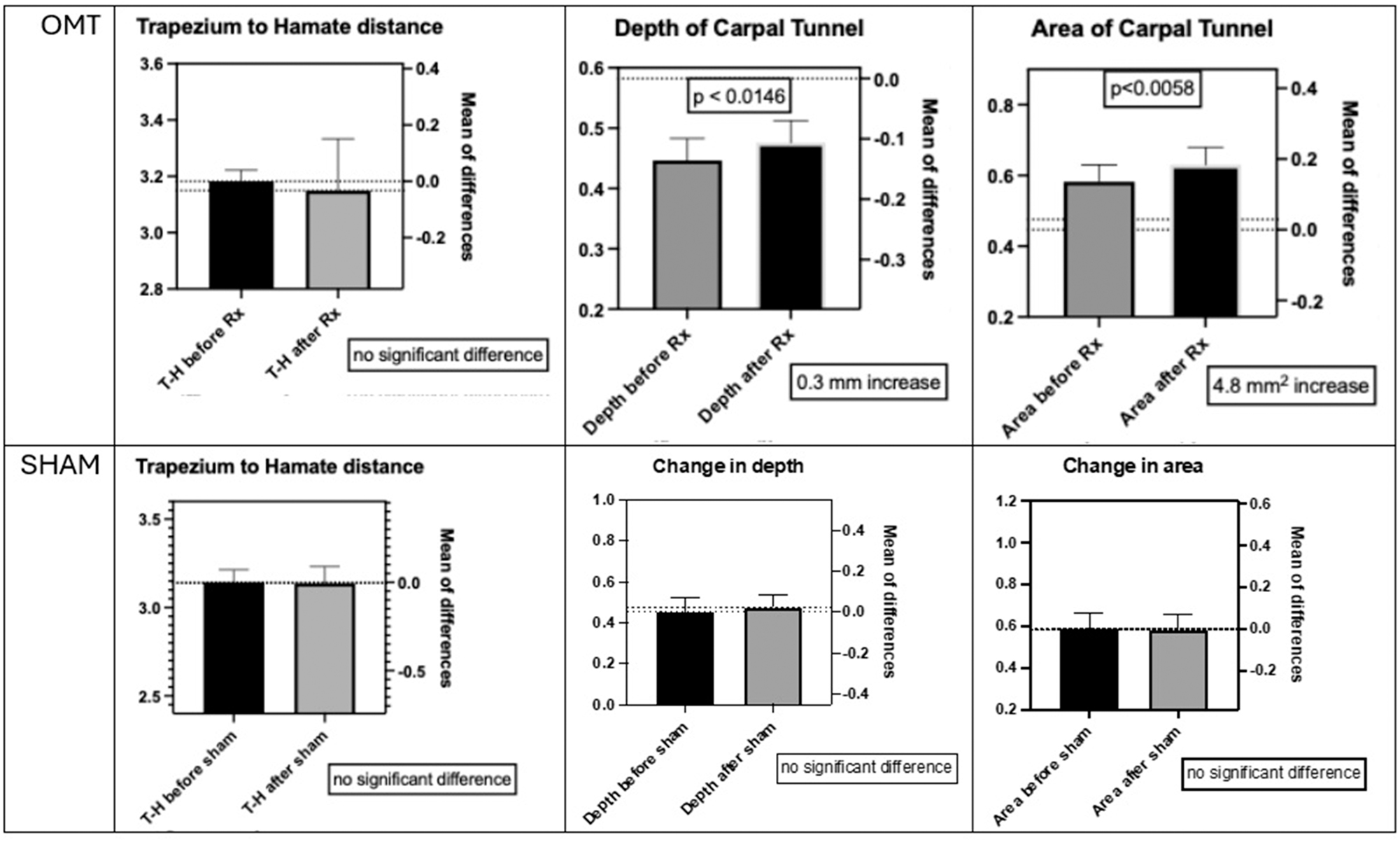

Comparison of the OMT and control groups revealed a mean increase in carpal tunnel depth from 0.45 mm ± 0.13 mm pre-OMT to 0.48 mm ± 0.13 mm post-OMT (p=0.0146, Cohen’s d=0.214, 95 % CI 0.0068 to 0.0517). There was also a mean increase in cross-sectional area from 1.83 mm2 ± 0.56 mm2 pre-OMT to 1.98 mm2 ± 0.59 mm2 post-OMT (p=0.0058, Cohen’s d=0.260, 95 % CI 0.0517 to 0.2490). There was no significant difference in canal width (p=0.5973) or transverse carpal ligament length (p=0.2673) following OMT intervention. The control group, which received the sham procedure, demonstrated no significant differences in the transverse carpal ligament length, carpal tunnel width, depth, or cross-sectional area before and after the sham intervention.

Conclusions

Ultrasound measurements at the narrowest section of the carpal tunnel before and after DCA-ME OMT of healthy asymptomatic wrists demonstrated a significant increase in cross-sectional area as well as depth, with no significant change in the length of the transverse carpal ligament, suggesting that the cause of the increased volume is an alteration of dorsal arch shape. A limitation of the study is the small sample size, inclusion of only healthy wrists, the short period of time between manipulation and measurements, and the difficulty of assuring the same level and angle of ultrasound measurements.

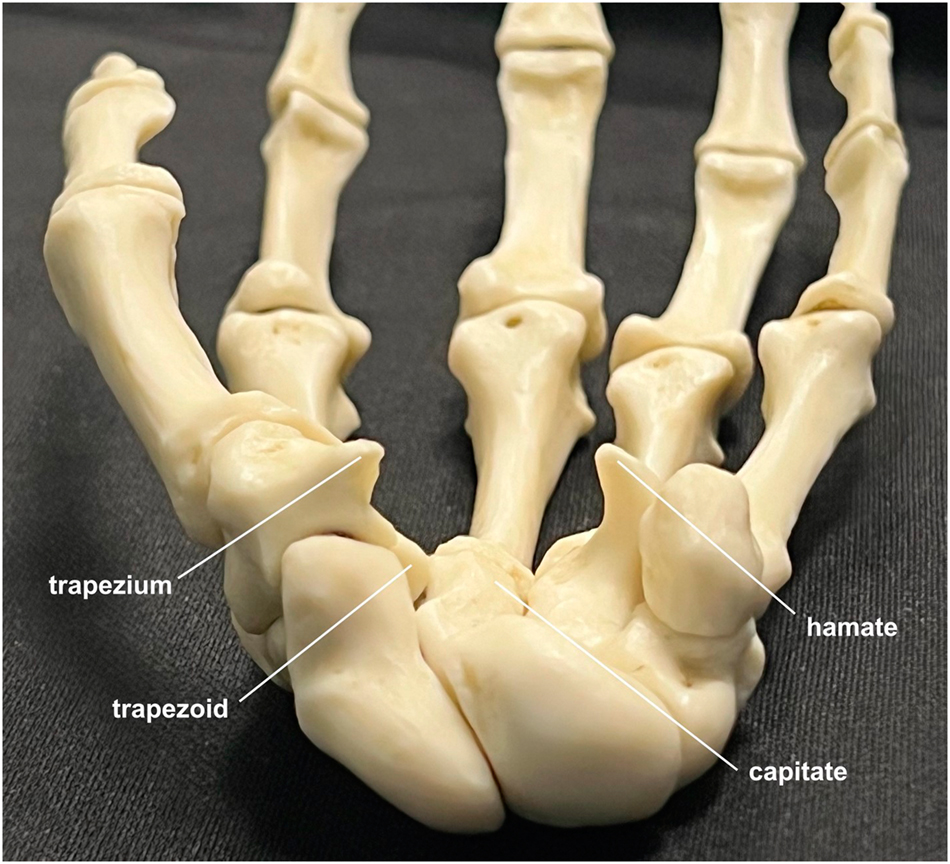

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most prevalent entrapment neuropathy, affecting about 10 % of individuals at some point in their lives [1]. In CTS, the median nerve is compressed within the carpal tunnel, which is formed dorsally by the arch of the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones, and volarly by the transverse carpal ligament (Figure 1). While severe CTS with thenar muscle atrophy is generally treated with prompt surgical release of the transverse carpal ligament to avoid further nerve damage, mild to moderate cases have been successfully treated with a variety of nonoperative interventions [2].

The bony components of the carpal tunnel, radial to ulnar: trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. The transverse carpal ligament runs between the tubercle of the trapezium and the hook of the hamate.

This pilot project investigated the mechanism of a previously undescribed technique of nonoperative carpal tunnel treatment, dorsal carpal arch muscle energy (DCA-ME), which focuses on the dorsal arch (trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones), manipulating the bones to redome the arch, round the tunnel, and increase its volume. While the actual effectiveness of such manipulation in the treatment of CTS can only be assessed and quantified in patients with the disorder, this initial study was carried out to see if it was feasible for physical changes following DCA-ME to be quantified with ultrasound. The dorsal carpal arch (DCA) bones, united by thin transverse intercarpal ligaments and longitudinal capsular fibers, are quite mobile. Such mobility provides an opportunity for osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) to resolve underlying somatic dysfunction and to optimize shape and volume of the carpal tunnel. The narrowest portion of the carpal tunnel lies between the hook of the hamate and the tubercle of the trapezium, and this site is evidenced by an hourglass distortion of the median nerve during a surgical carpal tunnel release [3]. Consequently, this was the site targeted for the measurements made in this study. Because ultrasound scanning has been found to be reliably reproducible for dimensional measurements in the carpal tunnel, it was the method utilized to quantify changes resulting from DCA-ME manipulation [4], 5].

Methods

A pilot study looking at immediate changes in nonpathological wrists following DCA-ME was undertaken in 25 healthy volunteers with no prior history of CTS, related wrist or arthritic disorders, or any upper extremity disorders. The request for volunteer participants was emailed to all 104 students in the second-year class at Sam Houston State University College of Osteopathic Medicine. The emails were limited to this class because they were familiar with osteopathic manipulation, having completed their first year, and as such would be more able to make an informed decision regarding participation.

Twenty-seven students responded and agreed to participate. One participant was excluded due to a prior hand disorder, and a second participant did not show. The remaining 25 participants were randomized to either the OMT group (n=14) or the control group (n=11) As participants responded, the group they were placed into alternated between the OMT and control group. The OMT group was the first and last group populated. The reason why the number of participants is 14 and 11 instead of 13 and 12, is that two sequential respondents were inadvertently placed into the same group (the OMT group).

The demographics of the groups were comparable. The OMT group consisted of three males and 11 females (average age, 26.4 years), and the control group consisted of three males and eight females (average age, 25.6 years). Because the participants were healthy, and there were no expected clinical outcomes, a patient registry was not indicated and thus not created. The Sam Houston State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study on March 23, 2023 (IRB# 2022–269), under the institutional category 4: studies that involve the collection of data through noninvasive procedures (not involving general anesthesia or sedation) routinely employed in clinical practice. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The consent was obtained by the primary researchers who gave the participants time to go through the paper consent form and ask any questions they might have prior to signing.

All ultrasound measurements were made by the same operator, the corresponding author, who is a hand surgeon with over 25 years of experience and great familiarity with ultrasound of the hand. To help minimize the inherent variability between individual measurements, the sessions were all conducted as closely together as possible, the 25 participants all being scanned between July 18, 2023 and September, 15, 2023. Furthermore, to keep the participants’ hands in the same position for each set of ultrasound measurements of the carpal tunnel, customized molded plastic splints were made for each participant prior to any manipulation. Five replicate measurements were made in the splint and were averaged to determine baseline dimensions of the carpal tunnel. Then, the splint was removed and the OMT group underwent DCA-ME manipulation (Figure 2), whereas the control group had a sham manipulation. The specifics of the OMT are demonstrated in a brief video (Supplemental File) and described as follows: DCA.ME OMT was performed by flexing the wrist to engage the flexion restrictive barrier. The individual then made a fist for 3–5 seconds while counterforce was applied. After a brief pause, the maneuver as repeated twice more, flexing the wrist further with lateral motion to optimize the curvature of the DCA. The sham manipulation consisted of the participant’s hand and wrist being held in neutral positions without any pressure or stretching.

DCA-ME OMT performed on the wrist. The wrist is flexed to engage the flexion restrictive barrier. The patient makes a fist for 3–5 s, and counterforce is applied. After a pause, the maneuver is repeated, flexing the wrist further with lateral motion to optimize the curvature of the dorsal carpal arch (DCA). After another pause, it is repeated once more.

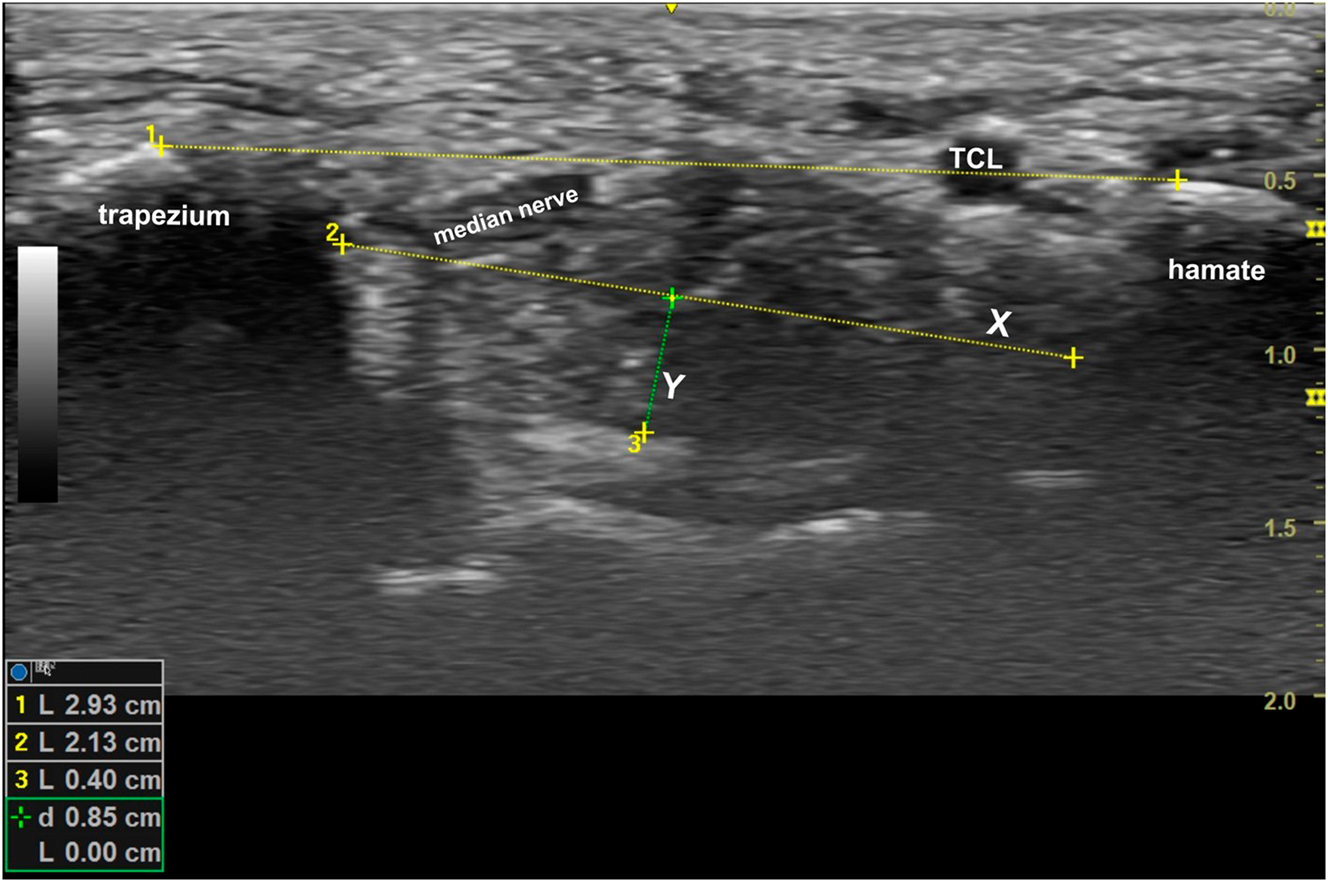

Immediately following the manipulation, each participant was placed back into their splint, and five more measurements made of the carpal tunnel dimensions which were then averaged. The ultrasound measurements were made with a GE Versana Active laptop utilizing a linear probe by a single physician (the corresponding author) who was blinded to which participants were in the control group and OMT groups. The length of the transverse carpal ligament was measured from the hyperechoic peaks of the hamate hook and trapezium tubercle. At this same level, the greatest width of the carpal tunnel and a right-angle distance from this line to the floor of the tunnel were measured. The area of the tunnel at this cross-section was estimated as an ellipse (Figure 3). The study employed a two-group, pre-/postmanipulation design to evaluate the anatomical changes resulting from the DCA-ME OMT manipulation compared to those following the control sham manipulation.

The length of the transverse carpal ligament was measured on a short-axis ultrasound of the carpal tunnel at its most restrictive site beneath the transverse carpal ligament running between the hook of the hamate and the tubercle of the trapezium. The greatest width of the carpal tunnel was also measured (X), and a right-angle distance from this line down to the floor of the tunnel (Y) was calculated. The area was estimated by multiplying 1/2(X) (Y) (π).

The primary hypothesis tested in this study was that there would be no difference following DCA-ME OMT in the dimensional parameters of the carpal tunnel as measured by ultrasound. All statistical analyses were performed utilizing GraphPad Prism version 10.0. A two-tailed paired t test was conducted to compare pre- and postintervention measurements in the OMT and control groups to quantify the anatomical changes.

Results

Twenty-five participants, mean age of 26 ± 2.18 (male=6, female=19) completed the study. Comparison of the OMT and control groups revealed a mean increase in carpal tunnel depth from 0.45 mm ± 0.13 mm pre-OMT to 0.48 mm ± 0.13 mm post-OMT (p=0.0146, Cohen’s d=0.214, 95 % CI 0.0068 to 0.0517). There was also a mean increase in cross-sectional area from 1.83 mm2 ± 0.56 mm2 pre-OMT to 1.98 mm2 ± 0.59 mm2 post-OMT (p=0.0058, Cohen’s d=0.260, 95 % CI 0.0517 to 0.2490). There was no significant difference in canal width (p=0.5973) or transverse carpal ligament length (p=0.2673) following OMT intervention. The control group, which received the sham procedure, demonstrated no significant differences in the transverse carpal ligament length 3.14 mm ± 0.24 mm vs. 3.14 mm ± 0.32 mm (p=0.8977), carpal tunnel width 2.43 mm ± 0.29 mm vs. 2.48 mm ± 0.35 mm (p=0.2517), depth 0.48 mm ± 0.21 mm vs. 0.48 mm ± 0.2 mm (p=0.4760), or cross-sectional area 1.85 mm2 ± 0.81 mm2 vs. 1.83 mm2 ± 0.80 mm2 (p=0.7397) before and after the sham intervention (Figure 4). A post-hoc power analysis was conducted utilizing G’Power 3.1.9.7 and showed that the achieved power was low at 0.351, likely due do the small effect size and sample size in this pilot study. The effect sizes were calculated and the 95 % confidence interval (CI) of the difference are presented with significant p values.

Comparing the means of measurements made before and after manipulation. The top row shows the results following DCA-ME OMT, with no significant difference in the distance from the trapezium to the hamate (the length of the transverse carpal ligament), a 0.3 mm increase in depth of the carpal tunnel, and a 4.8 mm2 increase in the carpal tunnel area. The bottom row shows the results following the sham manipulation with no significant difference between any of the measurements made before and after.

Although the changes in depth and area were small, which was not surprising in a group of healthy young wrists with no pathology and minimal to no somatic dysfunction, and the variability and margin of error substantial, there was still a significant difference in depth of the carpal tunnel before and after the DCA-ME, although there was no significant difference before and after the sham manipulation. These results were achieved with the same operator performing the measurements over a short period of time, blinded to who was treated and who was not.

Discussion

Multiple studies have shown clinical improvement in patients with mild to moderate CTS following OMT of the wrist, with most studies suggesting that the mechanism was stretching of the transverse carpal ligament [6], 7]. Physical therapy literature reports that neurodynamic techniques directed at improving nerve gliding and reducing tethering have been effective [8]. In a 2022 meta-analysis of six studies focused solely on a variety of manual treatments for CTS, reduction in pain and improvement in nerve conduction studies documented effectiveness [9]. In a 2023 systematic review of studies of adults with mild to moderate carpal tunnel without prior surgery or other medical conditions, Zaheer and Ahmed [10] found that nonoperative treatments that also included carpal bone manipulation along with nerve gliding and massage successfully reduced pain and objective signs of CTS based on the Boston Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Questionnaire (BCTSQ) and nerve conduction studies. In a related review in 2022, Wielemborek and colleagues [11] reviewed 72 studies reporting on nonoperative treatments of CTS ranging from massage and manipulation to laser therapy and extracorporeal shock therapy. The latter had equivocal results with risk-benefit concerns, but the manipulative approaches generally demonstrated consistent improvement [11]. In a 2017 prospective study of 100 women with mild to moderate CTS randomized to treatment with surgery or manual therapy including stretching of the transverse carpal ligament, Fernández-De-Las-Peñas and colleagues [12] found no significant difference between the two. However, the manual therapy in this study included musculoskeletal treatments of the neck and shoulder, suggesting that at least some component of the patients’ symptoms could have had a more proximal origin than the carpal tunnel.

Extensive clinical experience and investigation of OMT for CTS was reported by Sucher and colleagues [13], [14], [15], in the late Twentieth century. These efforts were focused on manipulation of the volar aspect of the carpal tunnel to stretch the transverse carpal ligament, with documentation of the changes in the transverse carpal ligaments, in both living patients and cadaver studies [16], 17]. The method utilized to document transverse carpal ligament changes in cadavers had been implemented successfully in a previous study [18].

However, such focus on the transverse carpal ligament may have obscured attention on another aspect of the carpal tunnel, the dorsal arch. The carpal bones making up this arch – the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate – have relatively thin intercarpal ligaments, allowing for significant mobility. Such mobility provides an opportunity for OMT to resolve any underlying somatic dysfunction and to optimize the shape and subsequent volume of the carpal tunnel. This was the concept underlying the DCA-ME OMT technique utilized in this study. Interestingly, in 2017, carpal bone manipulation focusing on stretching the transverse carpal ligament was performed on 18 volunteers with no hand pathology, resulting in a rounding of the dorsal arch and an increased depth and cross-sectional area of the carpal tunnel on ultrasound [19]. These findings parallel ours, despite their targeting the volar carpal ligament, whereas we targeted the DCA, suggesting that both maneuvers effect a change in dorsal arch dynamics.

In 2011, a study utilizing eight fresh cadaver hands applied a pressure of 200 mmHg within the carpal tunnel, which changed the shape of the carpal tunnel from a flatter to a rounder shape with an increased depth and cross-sectional area [20]. Somatic dysfunction of the carpal bones causes a flatter DCA, reducing tunnel volume and constricting the median nerve, whereas an optimized, rounder arch increases volume and relieves pressure on the nerve [21]. The effectiveness of osteopathic manipulation utilizing muscle energy techniques for carpal tunnel has been documented [22]. However, while ultrasound measurements of the carpal tunnel have been reported, such measurements have not been utilized to quantify changes following a DCA-ME technique [23].

More often, when ultrasound of the carpal tunnel is addressed in the literature, it is with regard to ultrasound-guided minimally invasive transverse carpal ligament release [24], 25]. As attractive a treatment as this is, given that it can be done under local anesthesia in an office setting, avoiding surgery altogether with OMT is certainly a preferable goal. Optimization of DCA-ME OMT by understanding its precise structural effects can help achieve this goal. This pilot study was a first step in investigating the structural effects of DCA-ME.

Limitations of our current study are the small sample size, the short period of time between manipulation and measurement, the investigation of only normal wrists with the need to translate the investigation to wrists with CTS, and the difficulty of assuring the same level and angle of ultrasound measurements. The significant difference in both depth and area following OMT needs to be interpreted within the context of the observed effect sizes. Both parameters had small effect sizes, indicating that although the results were statistically significant, the actual implication of clinical relevance may be limited. This is not too surprising given that all participants had no signs or symptoms of CTS and therefore the increase in depth and area may have been limited because there was little restriction in the beginning.

While the overall reliability of ultrasound to make measurements of the carpal tunnel has been documened [4], 5], it is the difficulty of recreating the exact same angle of view to obtain consistently accurate measurements with small effect sizes that introduces some margin of error. There are “judgment calls” that must be made during ultrasound measurements. Having the same physician make all the measurements in a consistent manner over the 2 months of data collection helped to keep the judgments consistent. In this pilot study, the measurements were only made immediately following the manipulation to see if there was any measurable dimensional change, and if so, where the change was.

While we must be careful about drawing conclusions from this pilot study with such a margin of error, we can note the trend regarding depth and area, and utilize this as a guide in future studies with a larger cohort of participants with documented early to moderate CTS. Knowing the inherent difficulty of maintaining the exact same angle of scanning before and after, the methods in this study of utilizing the same operator for measurements and hand splints maintaining the same position, coupled with a larger cohort of subjects with existing somatic dysfunction to correct, should provide greater effect size and power, even with the underlying margin of error. Measurements would then be made not only immediately following the manipulation, but also at later time periods, associating the follow-up ultrasound measurements with subjective and objective changes in the patients’ CTS.

Conclusions

Ultrasound measurements at the narrowest section of the carpal tunnel, both before and after DCA-ME OMT of healthy asymptomatic wrists, demonstrated a significant increase in cross-sectional area as well as depth, with no significant change in the length of the transverse carpal ligament, suggesting that the cause of the increased volume is an alteration of the dorsal arch shape.

Funding source: The American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine

Award Identifier / Grant number: Research_Grant_M.Loomis 2023-2024

-

Research ethics: The Sam Houston State University institutional review board approved the study (IRB# 2022-269). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: This study was funded with a grant from the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine.

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

1. Padua, L, Cuccagna, C, Giovannini, S, Coraci, D, Pelosi, L, Loreti, C, et al.. Carpal tunnel syndrome: updated evidence and new questions. Lancet Neurol 2023;22:255–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00432-X.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Sheereen, F, Sarkar, B, Sahay, P, Shaphe, M, Alghadir, A, Iqbal, A, et al.. Comparison of two manual therapy programs, including tendon gliding exercises as a common adjunct, while managing the participants with chronic carpal tunnel syndrome. Pain Res Manag 2022:1975803. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1975803.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Qattan, M. The anatomical site of constriction of the median nerve in patients with severe idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br 2006;31:608–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.07.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Aléman, L, Berná, J, Reus, M, Martinez, F, Doménech-Ratto, G, Campos, M. Reproducibility of sonographic measurements of the median nerve. J Ultrasound Med 2008;27:193–7. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2008.27.2.193.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Bueno-Gracia, E, Malo-Urriés, M, Ruiz-de-Escudero-Zapico, A, Rodríguez-Marco, S, Jiménez-Del-Barrio, S, Shacklock, M, et al.. Reliability of measurement of the carpal tunnel and median nerve in asymptomatic subjects with ultrasound. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2017;32:17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2017.08.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Schreiber, AL, Sucher, BM, Nazarian, LN. Two novel nonsurgical treatments of carpal tunnel syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2014;25:249–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2014.01.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Burnham, T, Higgins, D, Burnham, R, Heath, D. Effectiveness of osteopathic manipulative treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome: a pilot project. J AM Osteopath Assoc 2015;115:138–48. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2015.027.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Wolny, T, Linek, P. Is manual therapy based on neurodynamic techniques effective in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. Rehabil 2019;33:408–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518805213.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Jiménez-Del-Barrio, S, Cadellans-Arróniz, A, Ceballos-Laita, L, Estébanez-de-Miguel, E, López-de-Celis, C, Bueno-Gracia, E, et al.. The effectiveness of manual therapy on pain, physical function, and nerve conduction studies in carpal tunnel syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop 2022;46:301–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-021-05272-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Zaheer, S, Ahmed, Z. Neurodynamic techniques in the treatment of mild-to-moderate carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2023;12:4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12154888.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Wielemborek, PT, Kapica-Topczewska, K, Pogorzelski, R, Bartoszuk, A, Kochanowicz, J, Kułakowska, A. Carpal tunnel syndrome conservative treatment: a literature review. Postep Psychiatr Neurol 2022;31:85–94. https://doi.org/10.5114/ppn.2022.116880.Search in Google Scholar

12. Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C, Cleland, J, Palacios-Ceña, M, Fuensalida-Novo, S, Pareja, JA, Alonso-Blanco, C. The effectiveness of manual therapy versus surgery on self-reported function, cervical range of motion, and pinch grip force in carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:151–61. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7090.Search in Google Scholar

13. Sucher, B. Myofascial release of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1993;93:1273–8. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.1993.93.1.92.Search in Google Scholar

14. Sucher, B. Palpatory diagnosis and manipulative management of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1994;94:647–63. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.1994.94.8.647.Search in Google Scholar

15. Sucher, B, Hinrichs, R, Welcher, R, Quiroz, L, St Laurent, B, Morrison, B. Manipulative treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: biomechanical and osteopathic intervention to increase the length of the transverse carpal ligament: part 2. Effect of sex differences and manipulative “priming’’. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2005;105:135–43.Search in Google Scholar

16. Sucher, B. Myofascial manipulative release of carpal tunnel syndrome: documentation with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1993;93:1273–8. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.1993.93.12.1273.Search in Google Scholar

17. Sucher, B, Hinrichs, R. Manipulative treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: biomechanical and osteopathic intervention to increase the length of the transverse carpal ligament. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1998;98:679–86. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-1998-0118.Search in Google Scholar

18. Fuss, F, Wagner, T. Biomechanical alterations in the carpal arch and hand muscles after carpal tunnel release: a further approach toward understanding the function of the flexor retinaculum and the cause of postoperative grip weakness. Clin Anat 1996;9:100–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1996)9:2<100::AID-CA2>3.0.CO;2-L.10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1996)9:2<100::AID-CA2>3.0.CO;2-LSearch in Google Scholar

19. Bueno-Gracia, E, Ruiz-de-Escudero-Zapico, A, Malo-Urriés, M, Shacklock, M, Estébanez-de-Miguel, E, Fanlo-Mazas, P, et al.. Dimensional changes of the carpal tunnel and the median nerve during manual mobilization of the carpal bones. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2018;36:12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2018.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

20. Li, Z, Masters, T, Mondello, T. Area and shape changes of the carpal tunnel in response to tunnel pressure. J Orthop Res 2011;29:1951–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.21468.Search in Google Scholar

21. Mehner, T, Lewis, D. Osteopathic approach to treatment of carpal dysfunction: the carpal mobilization technique. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2020;120:783–4. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2020.120.Search in Google Scholar

22. Snyder, M, Hawks, M, Moss, D, Crawford, P. Integrative medicine: manual therapy. FP Essent 2021;505:11–17.Search in Google Scholar

23. Rani, M, Yadav, N, Srivastava, M, Jain, A, Srivastava, N, Yadav, A, et al.. An evaluation of the variations in the carpal tunnel dimensions of adult subjects in a hospital-based population: an ultrasonographic cross-sectional study. Cureus 2024;16:e56001. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.56001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Pistorio, AL, Chung, KC, Miller, LE, Adams, JE, Hammert, WC. Protocol of a multicenter prospective trial of office-based carpal tunnel release with ultrasound guidance (ROBUST). Cureus 2023;15:e37479. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37479.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Eberlin, KR, Amis, BP, Berkbigler, TP, Dy, CJ, Fischer, MD, Gluck, JL, et al.. Multicenter randomized trial of carpal tunnel release with ultrasound guidance versus mini-open technique. Expert Rev Med Devices 2023;7:597–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/17434440.2023.2218548.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2024-0167).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Behavioral Health

- Original Article

- Bridging the gap: associations of provider enrollment in OKCAPMAP with social deprivation, child abuse, and barriers to access in the state of Oklahoma, USA

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Original Article

- Impact of osteopathic tests on heart rate and heart rate variability: an observational study on osteopathic students

- General

- Review Article

- Comparing intubation techniques of Klippel–Feil syndrome patients in the last 10 years: a systematic review

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Understanding COMLEX-USA Level-1 as a Pass/Fail examination: impact and opportunities

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Longitudinal outcomes among patients with fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, or localized chronic low back pain

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Carpal tunnel dimensions following osteopathic manipulation utilizing dorsal carpal arch muscle energy: a pilot study

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Carpal tunnel dimensions following osteopathic manipulation utilizing dorsal carpal arch muscle energy: a pilot study

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Behavioral Health

- Original Article

- Bridging the gap: associations of provider enrollment in OKCAPMAP with social deprivation, child abuse, and barriers to access in the state of Oklahoma, USA

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Original Article

- Impact of osteopathic tests on heart rate and heart rate variability: an observational study on osteopathic students

- General

- Review Article

- Comparing intubation techniques of Klippel–Feil syndrome patients in the last 10 years: a systematic review

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Understanding COMLEX-USA Level-1 as a Pass/Fail examination: impact and opportunities

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Longitudinal outcomes among patients with fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, or localized chronic low back pain

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Carpal tunnel dimensions following osteopathic manipulation utilizing dorsal carpal arch muscle energy: a pilot study

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Carpal tunnel dimensions following osteopathic manipulation utilizing dorsal carpal arch muscle energy: a pilot study