Abstract

This study uses corpus data and analytical statistics to analyze the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie in medieval French. This paper first undertakes a survey of the chronological and geographical distribution of the particles pas and mie, and then a variation analysis of the use of these two negative reinforcer particles to better understand the use of reinforced French negation between 1100 and 1505. The historical findings, namely the loss of written mie, compared with the modern dialectal negation (spoken mie maintained in the dialects of the northeastern francophone regions) suggest that the disappearance of written mie corresponds with a shift in written norms during the fourteenth century rather than a change in the spoken language. Specifically, the observed written change in negative reinforcer particles is hypothesized as attributable to the fourteenth century expansion of a supra-regional scripta originating in Paris.

1 Introduction

In French to negate a finite verb one (prescriptively) must use two parts. The particles ne and pas surround the finite verb as in (1b). Colloquially in Modern French the ne can be omitted (1c), but to omit the pas in colloquial speech is usually considered ungrammatical (1d). However, in formal written French, this omission of pas can occur, albeit only in very particular syntactic environments, such as in si clauses (1e).

| Je parle français |

| I speak French |

| Je ne parle pas français |

| I don’t speak French |

| Je Ø parle pas français |

| I don’t speak French |

| * Je ne parle Ø français |

| … si je ne parle Ø français |

| … if I don’t speak French |

This two-part system of negation did not stabilize in its modern form as the conventional way of forming negation until the end of the seventeenth century (Hansen 2009). This structure with an obligatory post-verbal negative particle as part of a bipartite negation structure is markedly different from that of other modern Romance languages (cf. Sp. no hablo francés, It. non parlo francese). The negative particle pas, however, was not always the near-universally used particle as it is in modern French. In the Medieval period, both pas < Lat. passu(m) ‘step’, and mie < Lat. mica(m) ‘crumb’ were widely used negative reinforcer particles,[1] with most authors employing a variety of negative reinforcer particles within an individual text. These two particles were grammaticalized very early in the history of Old French, and, unlike many other particles (ex. point, goute, etc.) exhaustively cataloged by Möhren (1980), pas and mie were only rarely used with their lexical meaning as units of minimal value in negation reinforcement.[2] Eventually, toward the end of the Medieval period the particle mie disappeared while pas survived. Through careful analysis of the use of these particles, this paper concludes that the disappearance of written mie likely corresponds with a shift in written norms during the fourteenth century rather than a change in the spoken language.

This paper first uses a historical survey to describe the chronological and geographical distribution of the particles pas and mie, and then a completes a variation analysis of the use of these two negative reinforcer particles to better understand the development of French negation between 1100 and 1505. The historical findings (the disappearance of written mie) compared with the modern dialectal negation (spoken mie maintained in northeastern francophone regions) provide compelling evidence that the spread of a supra-regional written scripta was the reason behind the observed changes in the written negative reinforcer particles.

How this system of two-part negation arose was first addressed by Jespersen (1917). He argued that languages underwent various stages of development (Figure 1) towards a two-part negative in which, first, there was only the preverbal negator (Stage 1), then optionally the reinforced negation (Stage 2), followed by obligatory inclusion of both the preceding negator and the negative reinforcer particle (Stage 3), until the original negator itself becomes the optional element (Stage 4), as exemplified in modern colloquial French by (1c). It has even been argued that what is witnessed now in modern French is not a phenomenon of ‘ne dropping’, but rather ‘ne insertion’ in certain emphatic contexts (Fonseca-Greber 2007).

The Jespersen Cycle as it appears in Hansen and Visconti (2012: 455).

As Hansen (2009), Hansen and Visconti (2012), Boerm (2008), and others have acknowledged, Old French falls firmly within Stage 2 of the Jespersen Cycle. Negation in many of the texts from this time period consists of only the preverbal negator (2), or the preverbal ne coupled with a negative reinforcer particle (3).

| Tu | n’ies | Ø | mes | hom |

| you | neg-are.2sg | Ø | my | servant |

| ‘You are not my servant’ | ||||

| c.1100 Chanson de Roland, v.297 | ||||

| Ne | li | est | pas | ami |

| neg | to.him | is.3sg | negparticle | friend |

| ‘He is no friend (at all) to him’ | ||||

| c.1135 Bestiaire, v.1013 | ||||

| Je | ne | me | repent | mie |

| I | neg | me.ref | repent.1sg | negparticle |

| ‘I do not repent (at all)’ c.1119 Comput, v.116 |

||||

The use in (3), became quite common. Price (1971: 254) states, “By the end of the Old French period, negation is expressed by ne + particle rather than by ne alone in about 25% or 30% of the cases where the particle must or may be used today.” What the exact purpose of the negative reinforcer particle was is unclear. The vague notion of ‘emphasis’ has been proposed on many occasions. In his book on comparative Old French syntax, Jensen writes, “Nouns serving as negation complements such as pas, lit. ‘step’; mie, lit. ‘crumb’; gote, lit. ‘drop’ are present already in the old language. Less commonly found than the simple ne, they may have originally been used for emphasis …, but they soon evolved into mere auxiliaries of the negation” (1990: 425). Concerning frequent examples of these negative reinforcer particles appearing before the ne + verb construction he continues, “a certain notion of insistence is added.” (425) However, Schwenter (2006: 329) notes that although the idea of emphasis is often invoked, it is rarely defined adequately, if indeed at all. Claiming the use or non-use of a linguistic variant as an indication of the internal motivations of an author is problematic because we have no other insight with which to corroborate the alleged ‘motivation to emphasize’. Deciding a priori that the presence of a negative reinforcer particle must signify ‘emphasis’ and then using that idea to determine whether a structure is ‘emphatic’ based on the presence of a negative reinforcer particle is circular and provides no insight.

Whatever the exact meaning distinction between reinforced negation and the unmarked form (ne + V) was remains to be determined. However, while the two-part negative structure differed from the unmarked simple negation, it has been claimed that the two negative reinforcer particles pas and mie (after having been completely grammaticalized) did not differ from each other (Detges and Waltereit 2008: 173), both being roughly equivalent to Eng. ‘(not) at all’. Therefore, there was a semantic and/or pragmatic difference between simple negation versus reinforce negation with pas/mie, but there was no discernible difference between reinforced negation with pas versus reinforced negation with mie. This generalization applied regardless of whether their use was to communicate emphasis or not. This situation allowed for competition between the particles, and each writer was free to employ either. This variation between pas and mie as negative reinforcer particles forms the basis for the analysis presented in this paper.

The most thorough treatment of negative reinforcer particles in Old French was undertaken by Price (1962). The Old French negative reinforcer particles are examined in a number of texts which “show a marked preference for one or other particle” (Price 1962: 19). He presents the total counts for negative particles in shorter texts and the first hundred in longer texts. In reporting these tokens, Price does not differentiate between the tokens of ne…pas, pas ne, non pas, etc. The inclusion of non pas particles suggests that he includes tokens where the negative particle is used in contexts other than finite verb negation (negation of noun, adjective, etc.). He does not consider negative use of pas or mie without the ne.

Price’s investigation led him to several important conclusions about the use of negative reinforcer particles. First, he finds that mie was used primarily adverbially but occasionally substantivally until the early thirteenth century. Although a form dialectally marked as from the north or east, it was adopted into the literary koine “originally for reasons of rime and assonance” (Price 1962: 33). By the fifteenth century mie had been declining as pas expanded, and was not used after the early 1400’s. Second, Price claims that pas was “the characteristic Francien particle”[3] (33), that it competed with mie and point in Old French, and that it was never used with partitive constructions before the sixteenth century.

Dees (1980, 1987 examined a number of (mostly orthographic) features within thirteenth century texts of the langue d’oïl region in order to create a pair of medieval dialect atlases organized by region rather than individual towns as are most modern atlases. Dees (1980) examines only non-literary texts, and Dees (1987) examines only literary texts. Pictured here in Figure 2 is the relative frequency of the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie in literary texts (reproduced from Dees (1987)). Unfortunately, no corresponding map appears in his 1980 atlas using data from non-literary texts. One hundred percent frequency refers to categorical use of mie, while zero percent would be categorical use of pas. Visually, the darker the shading, the greater the use of pas. Consistent with Price’s conclusions, there is much more mie use in the north and east of the francophone region. It also bears pointing out that several regions in the west have insufficient data and therefore should not be automatically considered to reflect the same trends as the adjacent ones (noted also by Volker (2003: 154)).

Map of relative frequency of pas and mie in literary texts originating in the oïl regions (Dees 1987: 516).

Dees’ two dialect atlases (Dees 1980, 1987) are monumental in nature and have undoubtedly added much to the understanding and description of dialectal trends in Medieval French. The map above leads to two questions to be addressed in the present paper: i) how the negative reinforcer particles change diachronically, and ii) what trends non-literary documents show.

To that end, this paper will update and contextualize the work of Price (1962) and Dees (1987) by addressing the following research questions:

What was the geographic and chronological distribution of the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie in Old French between 1100 and 1505?

What variables conditioned the use of the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie in Old French before and after the disappearance of mie?

What are possible explanations for the changes in use of the negative reinforcer particles, in particular the disappearance of mie?

Section 2 addresses the first research question, using mixed-effects logistic regression models and a variability-based neighborhood clustering with tokens extracted from the Base de Français Médiéval corpus. Section 3 addresses the second research question by describing the quantitative variation analysis identifying which linguistic and extra-linguistic variables affected the use of each negative reinforcer particle. Finally, Section 4 addresses the third research question by comparing these findings with data from the Atlas Linguistique de la France and the socio-historical context of Medieval France in order to propose that the disappearance of mie was a written change, and a written change alone, at least in the northeastern oïl regions.

2 Geographic and chronological survey

To determine the geographic and chronological distribution of the negative reinforcer particles, tokens of pas and mie used in finite-verb negation were collected from 96 texts composed between 1100 and 1505 with a dialect region recorded in La Base de Français Médiéval (BFM).[4]

Due to the length of some of the texts, all tokens of the negative reinforcer particles pas or mie were collected until the one hundredth token of either particle. At that line of text, the data collection stopped. Therefore, the maximum possible number of tokens collected from any single text is 199. If neither the number of pas nor mie tokens reached 100, all tokens were included. This method of extraction allowed for a robust data set and an accurate portrait of the distribution of the negative particles within each text without the unbalancing effect of thousands of tokens from a single document.

Each token was coded with the date of composition of the text (not the date of manuscript production)[5] and dialect region.[6] The date of composition was taken from the entry in the BFM for each text. When the date is given as an estimation, the latest possible year for each text was used. For example, “second quarter of the thirteenth century” was recorded as 1250, “end of the twelfth century” was recorded as 1200, etc. When only the century was given, the text was coded at the fifty-year mark. For example, “fifteenth century” was recorded as 1450. This was done in order to err on the side of perhaps documenting a change later than it occurred rather than earlier. As mentioned before, tokens were only collected from those texts with dialect region recorded in the BFM. The dialect regions occurring in the dataset are: Anglo-Norman, Burgundian, Champenois, Lorrain, Northwest, Norman, Orleanais, West, Parisian, Picardian, Poitevin, Wallonian. Figure 3 shows the dialect regions of Old French.

Dialect regions of Old French (Lodge 2004: 63).

2.1 Description of the data

In total, 5,226 tokens (3,240 of pas and 1,986 of mie) were collected from the BFM from 96 texts composed between 1100 and 1505. Tokens were extracted from 96 total documents. An average of 54 tokens was extracted per document. There are 35 named authors and 50 texts whose author remains anonymous. The breakdown is as follows: 1898 tokens from anonymous authors, 814 from Chrétien de Troyes (five texts), 176 from Henri de Lancastre, and 2,338 combined from the other named authors. Of the tokens, 1,785 were extracted from prose texts, 3,343 from verse texts, and 98 from mixed texts (with both verse and prose). The distribution of year of original composition for the data is shown in Table 1. As is evident, most of the texts date from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Year distribution of the tokens in the survey.

| Century | 1100–1199 | 1200–1299 | 1300–1399 | 1400–1499 | 1500–1505 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Token n | 2012 | 1943 | 792 | 379 | 100 |

Table 2 shows a breakdown of the data by dialect region. The biggest dialect contributors are: Picardian (n = 1004), Champenois (n = 943), and Anglo-Norman (n = 754). The dialects with the fewest tokens are: Northwest (n = 74), Lorrain (n = 117), and Burgundian (n = 194). The pas tokens comprise a greater amount of the data from the dialects of Norman, Orleanais, West, Parisian, Northwest, and Poitevin. The mie tokens comprise a greater amount of the data from the dialect of Lorrain. The dialects of Anglo-Norman, Champenois, Picardian, and Wallonian show a more even split between pas and mie as negative reinforcer particles.

Tokens of negative reinforcer particles by dialect region.

| Total tokens | n mie–n pas | Number of documents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anglo-Norman | 754 (14%) | 313–441 | 22 |

| Burgundian | 194 (4%) | 106–88 | 2 |

| Champenois | 943 (18%) | 421–522 | 9 |

| Lorrain | 117 (2%) | 98–19 | 3 |

| Northwest | 74 (1%) | 18–56 | 4 |

| Norman | 485 (9%) | 129–356 | 8 |

| Orleanais | 357 (7%) | 82–275 | 8 |

| West | 347 (7%) | 44–303 | 4 |

| Parisian | 294 (6%) | 22–272 | 6 |

| Picardian | 1004 (19%) | 466–538 | 22 |

| Poitevin | 210 (4%) | 36–176 | 4 |

| Wallonian | 447 (9%) | 253–194 | 4 |

| Total | 5226 | 1,986–3,240 | 96 |

The initial logistic regressions conducted in the program R confirmed that both the year and the dialect region in which a given text was composed were significant predictors of whether the negative reinforcer particles were more likely to be realized as pas or mie. The chronological variable is examined first.

2.2 Chronological analysis

Since the year of composition of the text was a significant predictor, confirmed by the models both with and without the random effect of document, the data were split into time periods in order to account for the effect of year of composition and more clearly examine the other variables.

Therefore, a value of percent pas was calculated for each year of the data (63 individual years). A percent pas was calculated for each individual text (96 documents) by dividing the number of tokens of pas by the sum of the total number of tokens. This yielded the percentage of negative reinforcer particles appearing as pas, rather than mie, for each text.

Most of the years were only associated with one text, so that text’s value was used for the year. For years in which several texts were composed, the percent pas value of each text was averaged together to have one value per year.

The data points for all 63 years are plotted here in Figure 4. In the first half of the period examined, there is a great deal of variation between the preference for pas or mie. There are years in which only pas is used and one year (containing only Robert de Clari’s Conqûete de Constantinople, c.1215) with only mie. After 1300, however, there is no year which uses pas less than 43% of the time (data point found just to the right of 1350), and there are 10 years which do not use mie at all (data points at 100). The dashed line of best fit shows the clear pattern for a higher percentage usage of the negative particle pas as the years advance.

Percent of negative reinforcer particles realized as pas for each year of the data with dashed line of best fit.

Many studies in historical linguistics divide their data by a category such as century. This is problematic because the distinction between 1299 and 1300 is, after all, a completely arbitrary one based on when western Europeans decided to begin the count. Grouping data into arbitrary hundred-year chunks may obscure an interesting change between the year 1225 and 1235, for example. Analytic statistics programs allow for much more subtle, data-motivated divisions to be drawn. To that end a Variability-based Neighbor Clustering program was run with the values from Figure 4. The developers of the VNC program explain,

The method, VNC for ‘Variability-based Neighbor Clustering’, involves an iterative algorithm, which in a stepwise fashion groups together those data from temporally adjacent corpus periods that are most similar to each other and, therefore, most likely to constitute a relatively homogeneous period of interest. The resulting data structure can be graphically represented in the form of a dendrogram and subjected to additional diagnostics to determine the number of periods that are most supported in the data and which data points are most likely outliers (Gries and Hilpert 2012: 135).

The data points calculated for each individual year returned a very skewed dendrogram with groupings that did not suggest any midpoint in the data where a division could be made. To normalize the data and to reduce the potential confounding effect of outlier years, the percent pas values were recalculated by decade rather than by individual year. Some decades were omitted due to the absence of texts composed during those years in the data. In this next dendrogram, the first decade was an outlier that was returned as significantly different from the rest of the entire dataset. That first decade contained only one text (Chanson de Roland, 47 tokens; 4 pas, 43 mie) and was thus excluded from the quantitative analysis. I will discuss the qualitative implications of this text in Section 2.4. This reduced the total token count to 5,179. The final dendrogram appears here in Figure 5.

Variable-based Neighbor Clustering with the chronological division drawn at the first split in the data.

Using this dendrogram generated by the VNC, the division was drawn at the first significant split in the data at the year 1310. The two resulting periods are: Period One (1119–1309) and Period Two (1310–1505). By splitting the data into two periods and verifying that year of original composition was not a significant variable within either period (analysis described below), the effect year of original composition has on negative reinforcer particle selection has been completely accounted for. Next, an analysis was conducted on each period individually to determine the significance of the extralinguistic independent variable of dialect region.

2.3 Dialect region analysis

After inputting the data for Period One into R, a step function, random forest, and a mixed-effects logistic regression were run to check for the effect of dialect region. Dialect region was returned as a significant predictor of negative reinforcer particle use but year of text composition was not. The same process was completed on the data from Period Two, and it yielded the same result. This validates the choice of 1310 as the dividing line between two time periods within which year of composition was not a significant predictor of negative particle use. Had year again been returned as significant within either period, it would mean that there was at least one more chronological divide to be considered. There was not. Thus, the variable of year of composition has been accounted for, and the significance of other variables can be analyzed within each period.

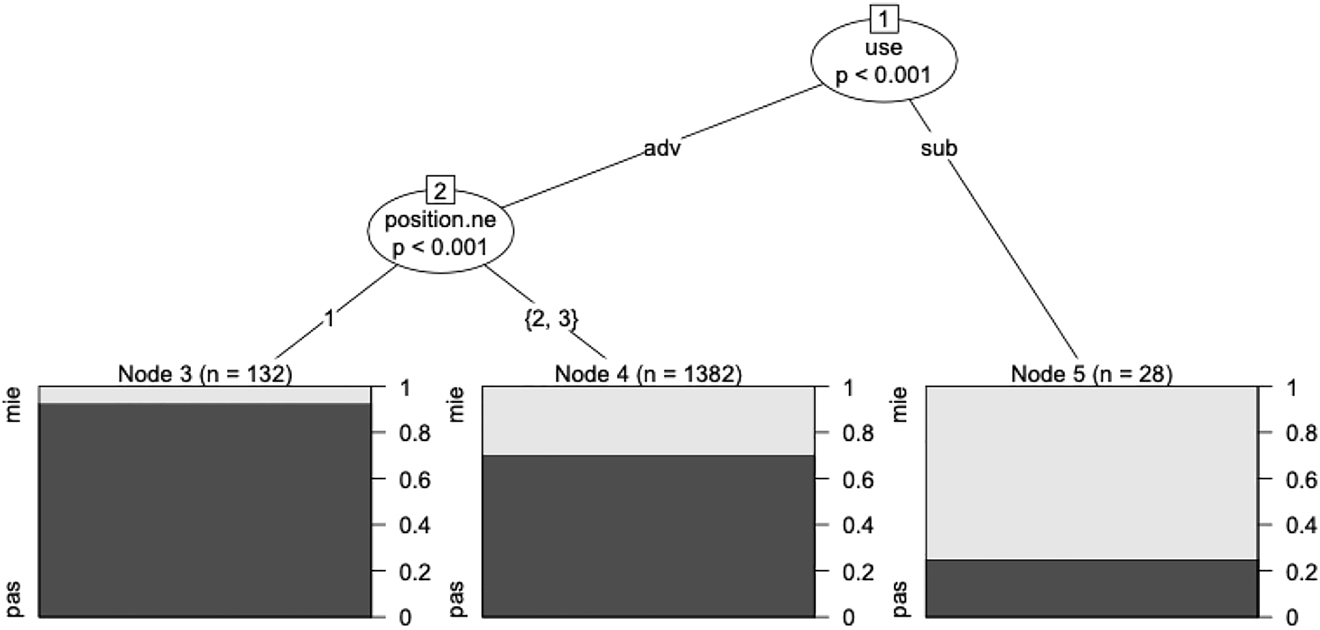

A conditional inference tree[7] was generated (Figure 6) to visualize the dialectal patterns of negative particle behavior in order to group together dialects whose use of the negative reinforcer particles did not significantly differ from one another. A conditional inference tree is a useful aid to visualize the interactions between variables, or the effects of the individual values of an independent variable compared with one another, as below in Figure 6. It is important to recognize that conditional inference trees do not show a description of the data, but rather a prediction of the value of a dependent variable given the values of one or more independent variables. In this case, the closer the bottom node value is to 1, the more likely pas would be used given the category of the independent variables above it.

Conditional inference tree showing the mixed-effects logistic regression for the variable of dialect region for Period One (1110–1309). The dialect regions to the left are more likely to select pas than those to the right.

The conditional inference tree shows a significant split between the predicted negative reinforcer particle use in two groups of dialects. The dialect regions of Anglo-Norman, Northwest, Norman, Orleanais, West, and Poitevin show a higher predicted use of pas. However, the dialects regions of Burgundian, Champenois, Lorrain, Parisian, Picardian, and Wallonian show a higher predicted use of mie than the aforementioned regions do. Since these dialect groups are adjacent to each other, an isogloss (Figure 7) neatly separates those which predict more pas from those which predict a greater amount of mie. Note that the isogloss does not separate dialect regions which prefer mie from those which prefer pas. It groups together the dialects which show a similar behavior in their pas/mie selection. Therefore, I characterize the dialect regions in the west as preferring pas to mie. Those in the east use more mie than do the dialect regions in the west. I do not say that those to the east of the isogloss use more mie than pas, which would be controverted by the Champenois data in node 10, Figure 6. This division is very similar to the one found by Pfister (1993: 39) in the year 1200. His research on the scriptology and dialectology of Old French documents showed there was a division in the oïl dialects between the western varieties (West, Central, Norman, Anglo-Norman) and the eastern ones (Champaign, Picardian, Wallon, Lorrain).

Period One (1110–1309) scriptological isogloss with predicted mie use higher in the eastern regions than in the western ones.

As in the analysis of Period One, dialect region was returned as a significant variable in Period Two. Therefore, a conditional inference tree was generated to examine any dialectal splits and group together those dialect regions which did not significantly differ from one another. The tree showing the dialectal divisions appears in Figure 8. The token counts in Period Two are smaller than Period One.

Conditional inference tree showing the mixed-effects logistic regression for the variable of dialect region for Period Two (1310–1505). The dialect region of Anglo-Norman to the right predicts much more mie use than those to the left.

As in Period One, the main division in the behavior of the negative reinforcer particles within each of the dialects allows for a clear isogloss to be drawn (shown in Figure 9) between the one area which maintains a fairly robust use of mie, Anglo-Norman, and continental French regions where mie has almost fallen out of use completely.

Period Two (1310–1505) scriptological isogloss with higher predicted mie to the north (Anglo-Norman).

2.4 Geographic and chronological survey conclusion

Let us return to the research question this study sought to answer: What was the geographic and chronological distribution of the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie in Old French between 1100 and 1505?

This large geographic and chronological survey of the distribution of the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie in Old French is able to offer specific answers which conform with the earlier findings of Price (1962) and Dees (1987). First of all, there is a significant split in the selection of negative reinforcer particles in the fourteenth century. According to the VNC and confirmed with mixed-effects logistic regressions, negative reinforcer particle selection in the years 1100–1309 is indeed significantly different than in the years 1310–1505.

Within Period One: i) the dialects regions of Norman, Anglo-Norman, Northwest, West, Orleanais, and Poitevin significantly predict the use of the negative particle pas over mie, and ii) the dialect regions of Burgundian, Picardian, Wallonian, Champenois, Parisian, and Lorrain predict a much higher use of the negative reinforcer particle mie than the former regions. Within Period Two: i) the dialects of Norman, Poitevin, Picardian, Parisian, West, Champenois, and Orleanais all significantly predict pas, and ii) the dialect region of Anglo-Norman shows a slightly higher prediction for the negative reinforcer particle mie than do the other dialect regions.

Let us briefly return to the one outlier text identified by the VNC which was not included in the quantitative analysis. The text Chanson de Roland, written around 1100 in the Norman dialect, showed a much larger amount of mie than many other texts from Period One, and certainly more than those from Period One to the west of the isogloss. The change between Period One and Period Two shows that there is definitely an expansion of pas occurring at the expense of mie in the dialects on the continent. The data from Roland suggests that there may have been even more mie use present in Old French than that witnessed in Period One to the east of the isogloss. It is possible therefore, that already in Period One, we are seeing a middle phase in the greater expansion of pas relative to mie. Qualitatively, Roland could suggest that mie was much more widespread in the years before the texts examined here were written. Any such assertion, however, will always be on uneven footing since the behavior of the negative particles of any one particular text could be an anomaly. Exactly what the behavior of negative reinforcer particles looked like in this earlier era has unfortunately been lost, but it is important to note that negative reinforcer particle variation and change appears to have been a constant throughout the history of French.

In summation, this survey has been able to divide the data according to the variables of year and dialect region into four parts. The variation between the negative reinforcer particles pas and mie observed within the first three of these smaller data sets will be the focus of the series of analyses presented in Section 3. The data from Anglo-Norman in Period Two will be examined separately for reasons which will be made clear. Also note that the dialect regions of Northwest, Wallonian, and Lorrain do not appear in Period Two because there are no texts from these regions included in the BFM.

Period 1A: 1110–1309 – Northwest, Norman, Anglo-Norman, West, Poitevin, Orleanais

Period 1B: 1110–1309 – Burgundian, Picardian, Wallonian, Champenois, Parisian, Lorrain

Period 2A: 1310–1505 – Norman, Poitevin, Picardian, Parisian, West, Champenois, Orleanais

Period 2B: 1310–1505 – Anglo-Norman

3 Variation analysis

The variable context for the negative reinforcer particles is defined as any token which appears with ne and negates a finite verb. The negative reinforcer particles pas and mie were not used in strict complementary distribution (illustrated in a couplet shown in (4) repeated three times throughout a certain poem) but there are patterns to be observed about their use.

| Encore | ne | m’ | avez | vous | mie , |

| still | neg | acc.me | have.2pl | youpl | negparticle |

| Encore | ne | m’ | avez | vous | pas ! |

| still | neg | acc.me | have.2pl | youpl | negparticle |

| ‘you do not have me (at all) yet, you do not have me (at all) yet!’ c.1415 | |||||

| Charles D’Orleans, Ballad 56, l. 7–8, 15–16, 23–24 | |||||

After having identified the beginning of the fourteenth century as a temporal limit between two distinct periods of negative reinforcer particle use, a series of mixed-effects logistic regressions were conducted to answer the second research question: what variables conditioned the use of the negative reinforcer particles before and after the almost total disappearance of mie from the continental regions?

To answer this question 4,752 tokens (2,962 pas, 1,790 mie) were used from the data examined in Section 2. These tokens were extracted from 77 texts composed between 1100 and 1481. The excluded tokens were from 23 texts which only used one particle or the other for reinforced negation and as such fall outside of the envelope of variation needed for this analysis.

Having already examined the extralinguistic factors of date of composition and dialect region, the following variables were recorded: document, author, text form (prose, verse, mixed), and text domain (literary, religious, didactic, political, legal, historical, act of practice). The following linguistic variables were considered in the main analysis: use of the negative reinforcer particle (substantival, adverbial), clause type (independent, dependent), and position of the negative particle relative to ne + V (before, between, after). Finally, the variable of position in line of verse (middle, end), and represented speech (narration, direct speech) were also examined separately within their own relevant subcorpora.

A description of the data appears here in Tables 3 and 4.

Negative reinforcer particle results by dialect region and text domain.

| Dialect region | Domain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pas | mie | pas | mie | pas | mie | |||

| Anglo-Norman | 422 | 311 | Orleanais | 275 | 82 | Act of practice | 168 | 2 |

| Burgundian | 88 | 106 | West | 200 | 44 | Didactic | 412 | 100 |

| Champenois | 511 | 421 | Parisian | 172 | 22 | Historical | 85 | 7 |

| Lorrain | 17 | 2 | Picardian | 529 | 366 | Legal | 191 | 2 |

| Northwest | 56 | 18 | Poitevin | 154 | 36 | Literary | 1439 | 1047 |

| Norman | 344 | 129 | Wallon | 194 | 253 | Political | 2 | 1 |

| Religious | 665 | 561 | ||||||

Negative reinforcer particle results by text form, particle use, ne position, and clause type.

| Text form | Use of negative particle | Position relative to ne + V | Clause | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pas | mie | pas | mie | pas | mie | pas | mie | ||||

| Prose | 877 | 449 | Adverbial | 2936 | 1737 | Before (position 1) | 269 | 40 | Ind | 2193 | 1345 |

| Verse | 2065 | 1282 | Substantival | 26 | 53 | Between (position 2) | 5 | 1 | Sub | 769 | 445 |

| Mixed | 20 | 59 | After (position 3) | 2688 | 1749 | ||||||

The three linguistic variables included in the main analysis are as follows. First, the function of the negative reinforcer particle in the sentence was recorded as either adverbial or substantival. When used substantivally a negative reinforcer particle will function as a partitive, usually in the direct object position, and could be translated as “no” or “nothing”. It is often accompanied by the prepositional phrase de + N or the pronominal en. A substantival example of pas is shown in (5) and substantival mie is shown in (6).

| ki | n’ont | pas | de | honte |

| pro.who | neg-have.2pl | negparticle | of | shame |

| ‘Those who have no shame (at all)’ | ||||

| c.1200 Li Dialoge Gregoire lo Pape, p. 25 | ||||

| encor | n’avoit | mie | d’epouse |

| adv.still | neg-have.3sn | negparticle | of.wife |

| ‘He still had no wife (at all)’ | |||

| c.1150 Roman de Thèbes, v.2333 | |||

When used adverbially the negative reinforcer particle directly modifies the verb, and the particle could be translated as “(not) at all”. An adverbial example of pas is shown in (7) and mie in (8).

| Ne | plorés | pas | sur | moy |

| neg | cry.2sg | negparticle | prep.over | me |

| ‘Do not cry (at all) over me’ | ||||

| c.1398 Récit du voyage en Terre Sainte, p. 55 | ||||

| qui | n’estoit | mie | venue |

| pro.which | neg-auxbe.3sg | negparticle | ptcp.come |

| ‘which had not come (at all)’ | |||

| c.1249 Lettre à Nicolas Arrode, p. 8 | |||

Second, clause type was not something that Price (1962) considered. In examining variation between simple negation and reinforced negation, Schøsler and Völker (2014) find clause type to be irrelevant. However, the findings of Hansen and Visconti (2009), which show that grammaticalizing negative reinforcer particles are more likely to be found first in independent clauses and only later in subordinate ones, have led to the inclusion of clause type as a possible conditioning factor here. Admittedly the general tendency of innovation occurring first in independent clauses (Bybee 2001) should be more pronounced within speech rather than written data, so the process of writing may have diminished or eliminated any effect. If there is an effect observed, then in areas where pas was an expanding innovation, it is predicted to occur more in independent clauses than in subordinate or embedded clauses. Tokens were coded as dependent if there was an overt non-coordinating conjunction or relative pronoun present.

Third, there was a large amount of variation in the placement of the negative reinforcer particle relative to the ne + V structure in both prose and verse texts. To examine this variable (referred to hereafter as ne-position), the negative reinforcer particle was coded as occurring either before (position one), between (position two, extremely rare, n = 6), or after the ne + V (position three). Example tokens which occur in positions one and three are shown below. In (9), the two occur in the same sentence, and within the same text in (10).

| les | deux | ne | sont | pas | plus | grans | que | ung | et | les |

| the | two | neg | be.3pl | negparticle | adv.more | big | conj.than | one | and | the |

| deux | pas | ne | sont | plus | grans que | une | ||||

| two | negparticle | neg be.3pl | adv.more | big | conj.than | one | ||||

| ‘Both are not bigger than one and both are not bigger than one’ c.1481 | ||||||||||

| Le Somme abregiet de theologie, p. 128 | ||||||||||

| et | les | chevax | mie | ne | let |

| and | the | horses | negparticle | neg | leave.3sg |

| ‘And he does not leave the horses (at all)’ | |||||

| c.1150 Roman de Thèbes, v.2076 | |||||

| ne | vivrai | mie | trois | semeinnes |

| neg | live.1sg.fut | negparticle | three | weeks |

| ‘I shall not live three weeks’ | ||||

| c.1150 Roman de Thèbes, v.4260 | ||||

Based on the observed interchangeability of the position of the negative reinforcer particle here, no prediction was made about the possible effect of ne-position.

3.1 Variation analysis of Period 1A

Of the 4,752 tokens in the entire dataset, 1,542 (1,098 pas, 444 mie) fall within the group of Period 1A which spans the years 1110–1309 and includes the dialect regions of Norman, Poitevin, Northwest, West, Orleanais, and Anglo-Norman.

In R a mixed-effects logistic regression model which best accounted for the data was generated. The particular document of each token in question was included as a random effect. Within that model the only significant predictors were ne-position and the function of the negative particle (either adverbial or substantival). The model is shown in Table 5.

Mixed-effects logistic regression model for Period 1A.

| Estimate | Std. error | Z value | Pr(> |z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.8017 | 0.4566 | 6.136 | 8.47e−10*** | |

| Ne-position (reference level: Ne-position 1) | Ne-position 3 (n = 1405; 91%) | −2.2002 | 0.3973 | −5.538 | 3.06e−08*** |

| Particle use (reference level: adverbial use) | Substantival use (n = 28; 1.8%) | −2.0798 | 0.4759 | −4.370 | 1.24e−05*** |

-

The number of asterisks corresponds to the level of significance. * = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001.

A conditional inference tree shows the interactions between these two variables, pictured here in Figure 10.

Conditional inference tree based on the mixed-effects logistic regression model for Period 1A.

For the dialects in Period One on the western side of the isogloss, when the negative reinforcer particle is clearly functioning as a substantival element, mie is more likely to be used than pas (Node 5, Figure 10). Mie was more likely to appear in substantival contexts due its initial nominal meaning of ‘a crumb/a small amount’ before undergoing the grammaticalization process.

Ne-position one (negative particle before ne + V) predicts pas over 90% of the time (Node 3, Figure 10). During the entire data collection it was noticed that pas occurs much less frequently at the end of a line of verse than does mie. Of all of the tokens from texts written in verse, only 7% of pas tokens occur at the end of a line of verse (149/2,067) whereas 44% of mie tokens occur in that position (574/1,292). This pattern of pas avoiding appearing at the end of a line of verse may be able to be explained by differences in word-final vowel frequencies which would affect rhyme schemes.

Ne-position three (negative reinforcer particle after the ne + V) predicts pas use about 70% of the time (Node 4, Figure 10). Of all of the possible contexts of negative reinforcer particle use, the most canonical (shown by the overwhelming majority of tokens in this node, n = 1,382) would be adverbial use in ne-position three.

The texts included in Period 1A show a strong (∼70%) tendency to prefer pas as the negative reinforcer particle of choice in the canonical, unmarked position.

3.2 Variation analysis of Period 1B

Of the 4,752 tokens in the entire dataset for the variation analysis, 2,383 (1,224 pas, 1,159 mie) fall within the texts of Period 1B which span the years 1110–1309 and include the dialect regions of Burgundian, Picardian, Wallonian, Champenois, Parisian, and Lorrain.

A mixed-effects logistic regression model was generated which best accounted for the data. As before the document was included as a random effect. Within this model the significant predictors were: ne-position, domain, text form, and the function of the negative particle. The model appears in Table 6.

Mixed-effects logistic regression model for Period 1B.

| Estimate | Std. error | Z value | Pr(> |z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.5115 | 0.6930 | −0.738 | 0.460429 | |

| Ne-position (reference level: Ne-position 1) | Ne-position 3 (n = 2279; 95.6%) | −0.9371 | 0.2341 | −4.003 | 6.24e−05*** |

| Domain (reference level: literary) | e.g., Didactic (n = 127; 5.3%) | 3.6541 | 0.9586 | 3.812 | 0.000138*** |

| Text form (reference level: prose) | Verse (n = 1713; 71.89%) | 1.6407 | 0.6119 | 2.681 | 0.007332** |

| Particle use (reference level: adverbial use) | Substantival use (n = 43; 1.8%) | −1.0650 | 0.3997 | −2.664 | 0.007716** |

-

The number of asterisks corresponds to the level of significance. ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001.

A conditional inference tree shows the interactions between these variables, pictured here in Figure 11.

Conditional inference tree based on the mixed-effects logistic regression model for Period 1B.

Several important conclusions about the dialect regions on the eastern side of the isogloss in Period One can be drawn from the conditional inference tree pictured above. First of all, the main split in the behavior of the negative particles follows the domain of the text from which the token was extracted. Albeit with low token counts (127 and 101), didactic and legal texts are predicted to almost never select mie (Nodes 3 and 4, Figure 11). N.B. There was one token of mie in the legal domain in this period, and as such, use of pas is not quite categorically predicted in Node 4. The three remaining domains (historical, literary, and religious) show more interaction with other variables. First, within these domains, texts which are written only in prose or in both prose and verse overwhelmingly predict the negative particle mie (Nodes 12 and 13, Figure 11). Next, verse texts whose negative particle appears in ne-position one or two significantly predict pas. Again, this is most likely due to the tendency of pas to avoid appearing as the end of the line of verse. Finally, tokens extracted from a verse text in ne-position three are significantly predicted as mie when used substantively (Node 8, Figure 11), but when used adverbially the negative reinforcer particle selection is much more evenly split without a clear preference for either pas or mie (Node 9, Figure 11). This latter node shows the prediction for the most unmarked, canonical context for the negative particle in verse (evidenced by the high token count of 1,577), that of adverbial use in ne-position three.

Therefore, in Period 1B the most canonical use of the negative reinforcer particle in verse predicts both pas and mie with equal likelihood (prose predicts mie). Pas is only significantly predicted for the domains of didactic and legal texts, and for ne-position one in verse texts, but this result should be considered tentative due to the small amount of data. On the other hand, mie is significantly predicted in prose and mixed texts.

To summarize the use of the negative reinforcer particles in Period One, the dialect regions included in Period 1A (Norman, Anglo-Norman, Northwest, West, Poitevin, Orleanais) generally prefers pas, and the dialect regions of Period 1B (Burgundian, Picardian, Wallonian, Champenois, Parisian, Lorrain) show a more even split with equal variation, except in various specific contexts where more pas or mie is found.

3.3 Variation analysis of Period 2A

Of the 4,752 tokens in the entire dataset for the variation analysis, 611 (546 pas, 65 mie) fall within the group of Period 2A which span the years 1310–1505 and include the dialect regions of Champenois, Norman, Orleanais, Parisian, and Picardian.

A mixed-effects logistic regression model was generated to account for the variation in the data. It should be emphasized that there are many fewer tokens included in this data set than those from Period One. There are 611 total tokens from only 14 texts, six of which have contributed five or fewer tokens. Therefore, the most important finding is that this result is that these dialect regions are seen to differ from Anglo-Norman in this period. Because of these low text and token counts, the following empirical finding of the variation analysis may not be as generalizable to the broader description of Old French as those from Period One. Having stated that caveat, domain of the text was the only variable that had a significant effect on the data. The mixed-effects logistic regression model and corresponding conditional inference tree shown below are shown below in Table 7 and Figure 12, respectively.

Mixed-effects logistic regression model for Period 2A.

| Estimate | Std. error | Z value | Pr(> |z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.0678 | 0.3642 | 2.932 | 0.003370** | |

| Domain (reference level: literary) | Act of practice (n = 170; 27.8%) | 3.4921 | 0.9218 | 3.789 | 0.000152*** |

| Domain (reference level: literary) | Didactic (n = 200; 32.7%) | 1.5803 | 0.6838 | 2.311 | 0.020831* |

| Domain (reference level: literary) | Legal (n = 92; 15.1%) | 3.5817 | 1.2488 | 2.868 | 0.004131** |

-

The number of asterisks corresponds to the level of significance. * = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001.

Conditional inference tree based on the mixed-effects logistic regression model for Period 2A.

According to the model displayed in the conditional inference tree in Figure 12, the main observation to be made is that texts which fall into the domains of act of practice, didactic, and legal almost exclusively predict pas. On the other hand, literary and religious texts (I neglect to mention political texts here because of the extremely low token count, n = 3) significantly predict pas only 70% of the time. As will be discussed below, in the later years, mie is more likely to be preserved at the end of a line of verse, and it is not therefore unexpected that more mie is predicted here in literary domains than others.

Importantly, contrary to Period One, in this later period the most significant variable in determining negative reinforcer particle selection is the domain of the document and not dialect region. Keeping in mind the lower number of texts in this period, dialect region, which was by far the most significant variable in negative reinforcer particle selection in Period One, has completely lost its strong impact by Period Two. Something must have caused the negative reinforcer particles in Period Two to behave in a more uniform way across the francophone areas of the continent than in Period One.

3.4 Variation analysis of Anglo-Norman

The dialect of Anglo-Norman was included with the dialects which showed a significant preference for pas in Period One (i.e. those on the western side of the isogloss), so it is therefore surprising to see Anglo-Norman exhibiting a slight preference for mie in Period Two. Unlike the many texts written in Anglo-Norman in Period One, the data shown in Node 7 of the conditional inference tree for dialects in Period Two (Figure 8, n = 224) contains only four texts and is dominated by the Livre de seyntz medicines written by Henri de Lancastre (n = 176). To investigate this apparent change in behavior, I conducted a variation analysis on all of the data (from both Period One and Period Two) from Anglo-Norman.

The mixed effects logistic regression model including the random effect of document which best accounted for the data returned ne-position of the negative reinforcer particle as the only significant variable. Unlike other dialect areas, in Anglo-Norman there is no significant effect of year or domain on negative particle selection. A conditional inference tree shows that when before the ne + V, pas is almost exclusively predicted whereas after, pas is predicted only about 55% of the time. The mixed-effects logistic regression and the conditional inference tree are shown here in Table 8 and Figure 13.

Mixed-effects logistic regression model for Anglo-Norman data.

| Estimate | Std. error | Z value | Pr(> |z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.3507 | 0.8028 | 4.174 | 2.99e−05*** | |

| Ne-position (reference level: Ne-position 1) | Ne-position 3 (n = 170; 27.8%) | −3.1194 | 0.7489 | −4.165 | 3.11e−05*** |

-

The number of asterisks corresponds to the level of significance. *** = p < .001.

Conditional inference tree based on the mixed-effects logistic regression model for Anglo-Norman tokens.

Seen here as well, pas is much more likely to appear in ne-position one, presumably in order to avoid falling at the end of a line of verse where rhyming constraints could apply. Authors appear to have opted for alternate positions of pas wherever possible. Despite its apparent shift in negative reinforcer particle use relative to the other dialects, there is no diachronic change at all observable in Anglo-Norman. There is no increased use of mie, nor does Anglo-Norman show the same expansion of pas at the expense of mie as do the rest of the Old French dialect regions. This could be for several reasons, but the most likely explanation for this is the isolation of Anglo-Norman from the changing linguistic norms for the written language in continental French. This will be discussed further in Section 4.

3.5 Variation analysis conclusions

In the first period, there is a strong preference (70%) for pas within the western dialect regions when the negative reinforcer particle appears in its canonical position, adverbially after the ne + V. However, in the eastern dialect regions there is a more nuanced system of negative reinforcer particle selection. In particular, in historical, literary, and religious documents, much more mie is predicted than in the west. Mie is favored in prose, and when appearing in verse in the canonical position there is an even split with both pas and mie predicted about 50 percent of the time.

To summarize, in Period One there are specific contexts in which pas or mie is the sole particle of choice. However, when the negative particle occurs in the most canonical position, this variation analysis has been able to show that the isogloss (shown in Figure 7) separates the dialects to the west, which prefer pas at a rate of two-to-one, from the dialects to the east, which show equal variation between pas and mie.

In the later period, there is no, or only a very slight, effect of linguistic variables on the behavior of negative reinforcer particles on the continent, whereas in Anglo-Norman ne-position one almost exclusively predicts pas. After 1450, mie does not appear in the documents examined in this study.

Regarding the linguistic variables, the variable of clause type was not a significant predictor of one negative reinforcer particle over the other. Next, use of the negative reinforcer particle was significant and showed a strong preference for mie when the particle was used substantivally. Finally, ne-position showed a strong preference for pas in position one due to its avoidance of the end of verse line. Moving the negative reinforcer particle to ne-position one was a seemingly popular strategy employed by authors to avoid a line-final pas. It should be emphasized that this qualitative conclusion was formed impressionistically over the course of this data collection. Future specific studies on verse and rhyme schemes in Medieval French could draw more precise conclusions.

Additionally, two final linguistic variables of i) represented speech and ii) verse position were analyzed separately within their own smaller datasets. These were examined separately in order to allow the smallest possible effect of these variables to be observed. First, represented speech (whether a token appeared in narration or as a direct quote) had no effect on negative reinforcer particle use. This was determined by running a mixed effects logistic regression on the data from only those texts which included both direct quotes and narration. Second, verse position (whether a negative reinforcer particle occurred in the middle or at the end of a line of verse) was very collinear with ne-position and showed even more clearly that mie was much more likely than pas to occur in line-final position.

4 Discussion

4.1 Interpreting the results within scripta theory

These results have shown that there was a clear dialectal division in the behavior of the negative reinforcer particles in early Old French, but that mie had almost completely disappeared from continental French by the fourteenth century. Since the use of mie did not change in the more geographically removed dialect of Anglo-Norman, an obvious question arises: why is there a change in negative reinforcer particle use in the first half of the fourteenth century in continental French?

In order to address this question, it is necessary to first understand the exact nature of the change. This paper has presented evidence that sometime in the first half of the fourteenth century mie mostly disappeared from the written record in continental French. While there can be no doubt that mie was being lost in writing, whether it also disappeared from the spoken varieties of the time remains an outstanding question. According to a series of maps in the Atlas Linguistique de la France (ALF) (Gilliéron and Edmont 1902-1910), the negative reinforcer particle mie existed in speech at least until the beginning of the twentieth century in many eastern and northeastern areas of the langues d’oïl (map 896 in particular, but also 12B, 89, 101, 806B, 817, 897, 898B, 899, 1082, 1083, 1352, 1409B). Figure 14 below shows the isogloss to the east of which mie is recorded as existing in the ALF. Therefore, the loss of mie was only a written change and not a spoken change, at least in the areas which are documented as maintaining mie into the present. Given that some areas maintained the use of spoken mie into the twentieth century, it is possible that mie was maintained in the spoken language for centuries in even the regions which first show its disappearance from writing.

Composite isogloss to the east of which mie is found in the ALF (Gilliéron and Edmont 1902–1910).

The observed change in the use of the negative reinforcer particles in the documents examined thus likely reflects a written change in this period and not a spoken one. Therefore, in order to understand why this change took place, it is necessary to understand the nature of the written landscape of northern France and how that culture of writing was evolving during the medieval period.

This topic has been studied for decades and is perhaps most comprehensively described by Glessgen (2017). Here, I briefly outline the current thinking to place my results within the larger context of scripta theory.

After long centuries of Latin as the ubiquitous writing system comes the “emancipation of regional vernacular written traditions based on oral varieties” (Kabatek 2013: 160) at the beginning of the second millennium. This is the hypothesized linguistic situation of northern France at the beginning of the period examined in this study at the year 1100, namely one of widespread diversity with each region having its own distinct, although closely related, variety of spoken Romance. Alongside medieval Latin, within most regions there also existed a written variety of Romance originally developed from, and corresponding closely to, the regional spoken variety at this early period. Succinctly put, no linguistic uniformity, neither spoken nor written, existed in medieval France before the fourteenth century. Each linguistic center and each region produced writing according to a set of regional styles and practices, or a scripta (Dees 1985; Glessgen 2017; Gossen 1967; Kabatek 2013; Lodge 2004; Remacle 1948), which can be best conceptualized as a set of writing conventions followed in a given geographic area, or, rather simplistically, as a dialect of writing. Just as dialects can be limited in their geographic scope (ex. Brooklyn English) or broader (ex. North American English), so can scriptae. In the early period of Old French, there existed many different scriptae associated with different regions (ex. Wallonian, Champenois, Picard, etc.) and accorded various levels of prestige. These early regional scriptae refer to the correspond to the dialect region divisions found in Period One of the above data.

Just as certain pressures (social, political, etc.) affect both the geographic spread and loss of certain dialectal features, these types of pressures also have an effect on regional scriptae. In particular, in the history of French, regional variation tended to disappear as the power and prestige grew in the French state, increasingly centralized in the growing city of Paris.

Until about the year 1100, Paris was linguistically relatively unimportant. The city of Paris was the urban center of only one region in this patchwork of linguistic diversity at the beginning of the twelfth century. However, Lodge (1993) notes that massive immigration to the city in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries led to Paris growing from over 50,000 inhabitants during the twelfth century (103) to become Europe’s largest population center with 275,000 inhabitants by the year 1400.

While in Paris administrative use of the vernacular began in 1241 (Videsott 2016: 206), the two main centers of text production in the city, the Royal Chancellery and the Prevoté de Paris (Videsott 2016: 205), resisted the transition from Latin to the vernacular until about 1330.[8] During this period, there began to exist an “official” scripta, imbued with the prestige first of the university, then of the royal court (Videsott 2016: 206). The aforementioned developments and others, such as the Capetian kings relocating their primary residence to Paris from Orleans, the increasing use of the vernacular in that court, rapid population growth mostly due to immigration, the rise in economic importance of Paris, the decline of the importance of the fair towns, and the increasing importance of the great abbeys and schools (such as the future University of Paris), firmly established Paris as a center of linguistic gravity which began to exert linguistic pressure on regions further and further afield. This meteoric growth in importance of Paris up to the fourteenth century could also be seen in administrative writing, with the suppression of variation and the gradual disappearance of regional forms (Lodge 1993: 122). Thus, the growing power and social prestige of Paris allowed this new Parisian scripta to grow in popularity and became a supra-regional scripta, which then began to be used for text production in other oïl areas under the control of the French monarchy in the fourteenth century. A supra-regional scripta refers to a writing system which although having been developed in a certain geographic region, has spread and been adopted by writers and editors in other areas further afield.

The concept of a medieval scripta had its origins in the field of Gallo-Romance studies. First Remacle (1948) and then Gossen (1967) proposed the idea of a supra-regional scripta which medieval writers in northern France strove to approximate. However, these first proposals suggested a very early date for its emergence, anywhere between the eighth and the twelfth centuries. This idea is justifiably challenged by the question: if a supra-regional scripta did indeed exist in those centuries, why is there such a huge amount of (ordered) regional variability present in the texts of northern France in the Old French period (until the fourteenth century)? In two monumental variation studies, Dees (1980, 1987 presents hundreds of dialect maps, each representing a particular linguistic feature in Old French prose and verse texts. He shows that ordered regional variation continues to be the rule in Old French until at least the beginning of the fourteenth century. In Dees (1985), he argues that there was no supra-regional scripta that writers of Old French used before the year 1300. In a similar vein, many other scriptological studies have examined and cataloged a huge variety of features used by these regional scriptae (Glessgen 2008; Pfister 1993; Videsott 2013; among others). Moreover, Lodge explains, “the nature, extent and distribution of spelling variation in the thirteenth century texts [Dees] analyzed can be fairly reliably correlated with variation in the underlying spoken language as evidenced by the dialect atlases compiled in modern times” (Lodge 1993: 116). As mentioned above, this correlation can also be seen in the data presented in this paper on negative reinforcer particles, with the areas that used the most mie in between 1100 and 1309 maintaining the use of that particle in speech into the twentieth century. These facts further support the notion that many changes may be confined to the written domain.

This spread of a supra-regional scripta starting in the fourteenth century coincides with the loss of a large amount of textual variation in the oïl varieties, especially those features which were previously very geographically ordered (i.e., regionally marked). The negative reinforcer particle mie has been established as regionally marked in Period One. The lack of variation in negative reinforcer particle use on the continent in Period Two can thus be hypothesized a consequence of the use of expanding supra-regional scripta.

Now, the exact mechanisms and processes resulting in the creation and elaboration of this Parisian scripta which then became the supra-regional scripta for the areas under the control of the kingdom of France is debated. It has been proposed that this supra-regional scripta arose as a consequence of a koineization that took place in the spoken variety of Paris. This theory was put forth by Lodge (2004: 76–78) and deemed the ‘spoken koine hypothesis’. However, recently this idea has come under scrutiny, especially by Grübl (2013), who finds that the development of this supra-regional scripta was rather a result of the elaboration of a very rich pluricentric written vernacular tradition, building upon earlier ideas by Cerquiglini (1991: 114–124).

Nevertheless, it is valuable to examine Lodge’s theory. Briefly, it holds that massive population growth of Paris between 1100 and 1400 was fueled primarily by immigration from other langue d’oïl regions (Lodge 1993). These speakers brought their own regional spoken varieties with them which came into close contact with one another in the growing city. Over time, the linguistic convergence processes of mixing, leveling, and simplification in the spoken language gave rise to a contact variety known as a koine (e.g. Kabatek 2013; Siegel 1985; Trudgill 1986; Tuten 2003). If this is indeed what happened, it must be remembered that this spoken koine can only be observed indirectly through various texts of the period that survive.

In a parallel, but not directly related process, these texts in turn were composed by writers who were subject to the same linguistic pressures to mix, level, and simplify their written varieties to accommodate different writing traditions and their increasingly diverse audiences. A scripta can thus emerge as a result of convergence processes in writing that are parallel to those which we know can occur in speech. This contact-variety scripta would be best understood not as a written representation of a spoken koine, but rather a koineized variety developed for writing. This scripta would be more easily spread and accepted by those in other regions due to the leveled nature of the variety (i.e. fewer regionally marked forms would encourage acceptance because it would not be as readily identifiable as ‘foreign’ or ‘other’) and the prestige accorded its users.

In any case, however the Parisian scripta developed, it did spread and become the supra-regional scripta used most frequently when writing in the vernacular in the oïl areas beginning in the fourteenth century. Dees’ (1980, 1985, 1987 work shows the supra-regional scripta did not exist and spread until after 1300. This is clear because regionalisms mostly disappear from texts only after the turn of the fourteenth century (Ayres-Bennet 1996; Lodge 1993). This loss of written regionalisms can be seen in the data presented in this paper on negative reinforcer particles, with the areas that used the most written mie in between 1100 and 1309 maintaining the use of that particle in speech into the twentieth century.

To summarize, as masterfully explained by Glessgen (2017: 317), in the period between c.1100–1250 there were different writing norms everywhere (outside of Paris). Then, in c.1250–1300/1330 a scripta developed in Paris. Subsequently, in the period c.1330–1480 that scripta spread and became the supra-regional set of norms used for text creation across the oïl areas. Returning to negation, written variation in the negative reinforcer particle was either lost in the development of the Parisian scripta, or it was lost as a consequence of process of dialect/scripta contact during its expansion. More research would be needed to pinpoint the exact reason for why variation was lost from the Parisian scripta. However, whichever is the truth, the written variation between pas and mie was lost as a result of the creation, elaboration, and geographic spread of this supra-regional scripta across northern France.

Therefore, the data presented in this paper suggest that the observed change in the use of the negative reinforcer particles in medieval French in the eastern regions is not a result of mie’s complete disappearance from the spoken language (given that it was maintained in twentieth century regional speech), although it may indeed have fallen out of use in the western spoken varieties at this time. Rather, it appears that eastern writers abandon their previous written norms in the fourteenth century and begin to realize a different linguistic system, that of the supra-regional scripta, in which mie only appeared as a relic.

It bears mentioning that without a study based on other discursive traditions close to orality (such as private correspondence), it is impossible to categorically state that this change in negative particles was due to shifting written norms and not because of spoken phenomena. However, the timing of the change which coincides neatly with the spread of the supra-regional scripta, coupled with the fact that spoken mie was documented by the ALF in the eastern regions of the twentieth century, I find the hypothesis presented here to be the most convincing.

An outstanding issue remains. If mie disappears in continental French because writers are shifting from attempting to realize an earlier regional written norm (which may have included mie) to a regionally unmarked scripta that developed in Paris (which did not include mie), then why would this Parisian-developed variety not include the negative reinforcer particle mie, considering that Parisian fell among the dialect regions which used the most mie in before 1310? Simply put, my data are not sufficiently representative of this period and area to adequately address this issue. Given that centers of text production in Paris delayed the shift to the vernacular and continued to use Latin until much later than other regions, the corpus only contained three texts from the Parisian dialect region in Period One (Lecheor, Vie de saint Lambert, and Lettre à Nicolas Arrode).

Nevertheless, it is intriguing that mie was found in the very few documents included at high enough rate for it to be included with the eastern regions. This could tentatively lend support to the idea that as the Parisian scripta was in its early stage of development, it borrowed norms from other prestigious vernacular scriptae such as Champenois (which preferred mie) (Videsott 2013: 37).

Keeping in mind i) the important caveat that the Parisian data presented here cannot be considered representative, and ii) my data does not establish how robust the use of mie was in the early Parisian scripta, its disappearance could be the result of a leveling effect, common in the situations of language and dialect contact. Even in the early period in Old French, mie was already a regionally very marked form (found by Price (1962), and shown in the map in Dees (1987) in Figure 2). Importantly, mie appears to have been dialectally-marked, and not functionally-marked since it appears in variation with pas. Generally, these types of marked forms succumb to leveling pressures in situations of dialect convergence and are lost during koineization (Trudgill 1986). It is unlikely that convergence varieties would retain a marked feature. However, the fact that mie survives in verse contexts at the end of a line suggests slight differences between koineization and scripta development. In Lodge’s proposed koine, mie is likely to have disappeared completely, but because the scripta is a written system, it maintained more formulaic possible contexts within which mie could become entrenched and survive. This restriction of mie from a fully productive negative reinforcer particle to a variant only possible at the end of a line of verse corresponds with the idea of variant reallocation (Britain and Trudgill 2005; Trudgill 1986), wherein a variant is refunctionalized in a contact situation.

Again, the ideas presented here about the negative reinforcer particle situation in the Parisian dialect region are preliminary and speculative, given my sparse amount of data collected from the area. Further and more detailed examination of large amounts of Parisian documents from this period would be required to empirically justify any claim.

Finally, the need for an explanation of the changing behavior of the negative reinforcer particles in continental French was justified by juxtaposing those dialects against that of Anglo-Norman, which does not show this change. The proposed explanation for the almost total disappearance of mie in continental French after the first half of the fourteenth century would be strengthened if a convincing argument could be made for why the writers of Anglo-Norman did not participate in the shift from a regional written norm to the supra-regional scripta taking hold on the continent.

It has recently been suggested that Anglo-Norman is more innovative than continental French, arguing against the traditional notion that Anglo-Norman is a more conservative variety (e.g. de Jong 1996). Kunstmann (2009) shows that Anglo-Norman actually precedes continental French in the abandonment of the case system. Moreover, arguing that Anglo-Norman remained an interconnected part of the dialect continuum of Old French until at least the year 1362, Ingham (2009) presents evidence from three syntactic changes which occurred in continental French and were subsequently adopted into Anglo-Norman. However, the three features examined, namely i) object pronouns in infinitive clauses, ii) aucun as a negative polarity item, and iii) VS word order more closely resemble the criteria for Labov’s changes-from-below, rather than the possibly more salient choice of negative reinforcer particle. Therefore, the claim that Anglo-Norman remained a connected part of the Old French dialect continuum into the fourteenth century is consistent with my data, which shows a stark contrast in negative reinforcer particles between Anglo-Norman and continental French after the first half of the fourteenth century. At this stage it remains extremely hypothetical, but it is possible that writers of Anglo-Norman could have remained part of the Old French dialect continuum and participated in the less salient changes, while simultaneously rejecting changes in more salient features due to strong anti-France social pressures, linked to phenomena like increased centralization of the French state and the Hundred Years War. Therefore, should writers of Anglo-Norman have wanted to differentiate themselves from continental French (while subconsciously still existing within the Old French dialect continuum), we would expect particularly salient features to show the highest divergence from those of continental French. However, this idea is nothing more than an unsubstantiated hypothesis and requires future investigation.

It is also possible that mie may have survived in other areas like Lorrain and Wallonia, which are not represented by the Period Two texts in the BFM. These areas in particular, like Anglo-Norman may have escaped the standardizing influence of the Kingdom of France since they remained politically separate longer than other regions.

5 Conclusion

In summary, prior to the fourteenth century, there was a complex system of variation in how the negative reinforcer particles were used, with eastern dialect regions using mie about twice as much as those in the west. Towards the end of the thirteenth century a scripta emerged in Paris with characteristics of several other written norms. Then this scripta was accepted and increasingly used in surrounding regions, a fact evidenced in the loss of regionally-marked features in northern French texts – such as the virtual disappearance of written mie.

Interestingly, that this change took place in the first half of the fourteenth century overlaps precisely with a slew of other changes in medieval French including the reduction of diphthongs, the loss of hiatus, the dropping of schwa, elimination of the two-case system, increased use of SV word order, etc. Taken together, these changes have traditionally been used to delineate the boundary between Old and Middle French (Ayres-Bennet 1996: 98). This shift in negative reinforcer particle use should therefore be added to the list of linguistic changes between Old French and Middle French. Taking a step further, since the behavior of negative reinforcer particles can best be explained by a shift in which varieties specific writers were approximating (from a regional written norm towards a supra-regional scripta), and this change coincides with the host of other changes which have been used to mark the transition between Old and Middle French, it is possible that these other changes were a result of the same process.

This line of thinking suggests that the linguistic changes (such as the loss of the written negative reinforcer particle mie) that have been used to mark the date of transition from Old French to Middle French may not reflect ongoing changes in the spoken language. Rather they may document the spread of a new written norm, the scripta developed in Paris, due to socio-historical factors. Written changes can have little to do with a spoken linguistic system and still provide meaningful insight into the linguistic system of a historical community.

References

Ayres-Bennet, Wendy. 1996. A History of the French Language through Texts. London/New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Boerm, Michael Lloyd. 2008. Pourquoi ‘pas’: The socio-historical linguistics behind the grammaticalization of the French negative marker. University of Texas at Austin dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Britain, David & Peter Trudgill. 2005. New dialect formation and contact-induced reallocation: Three case studies from the English fens. International Journal of English Studies 5(1). 183–209.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan. 2001. Main clauses are innovative, subordinate clauses are conservative: Consequences for the nature of constructions. In Joan Bybee & Michael Noonan (eds.), Complex sentences in grammar and discourse: Essays in honor of Sandra A. Thompson, 1–17. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.110.02bybSearch in Google Scholar

Cerquiglini, Bernard. 1991. La naissance du français. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.Search in Google Scholar

Dees, Anthonij. 1980. Atlas des formes et des constructions des chartes françaises du 13e siecle. Tubingen: Niemeyer. 1–373.10.1515/9783111328980Search in Google Scholar

Dees, Anthonij. 1985. Dialectes et scriptae a l’epoque de l’ancien francais. Revue de Linguistique Romane 49. 87–117.Search in Google Scholar

Dees, Anthonij. 1987. Atlas des formes linguistiques des textes littéraires de l’ancien français, vol. 212. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer.10.1515/9783110935493Search in Google Scholar

Detges, Ulrich & Richard Waltereit (eds.). 2008. The paradox of grammatical change: Perspectives from Romance, vol. 293. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.10.1075/cilt.293Search in Google Scholar

Fonseca-Greber, Bonnibeth Beale. 2007. The emergence of emphatic ‘ne’ in conversational Swiss French. French Language Studies 17. 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959269507002992.Search in Google Scholar

Gilliéron, Jules & Edmont Edmont. 1902–1910. Atlas linguistique de la France. Paris: Champion.Search in Google Scholar

Glessgen, Martin. 2008. Les lieux d’écriture dans les chartes lorraines du xiiie siècle. Revue de Linguistique Romane 72. 413–540.Search in Google Scholar

Glessgen, Martin. 2017. La genèse d’une norme en français au moyen Âge: Mythe et réalité du francien. Revue de Linguistique Romane. 81. 313–397.Search in Google Scholar

Gossen, Carl Theodor. 1967. Franzosische Skriptastudien. Vienna: Osterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.Search in Google Scholar

Gries, Stefan & Martin Hilpert. 2012. Variability-based neighbor clustering. In Terttu Nevalainen & Elizabeth C. Traugott (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of English, 134–144. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199922765.013.0014Search in Google Scholar

Grübl, Klaus. 2013. La standardisation du français au moyen scriptologique. Âge: Point de vue. Revue de Linguistique Romane 77. 343–383.Search in Google Scholar