Abstract

Studies examining the relationship between grit and foreign language (FL) achievement have yielded inconsistent results. Furthermore, research on factors influencing grit is limited and primarily employs quantitative methodologies. To address these gaps, this study aims to reevaluate the link between grit and FL achievement among Chinese university students and identify factors influencing their grit by using a mixed-methods approach. In this study, 260 third- and fourth-year English major students participated in a questionnaire survey, and 35 of them also underwent semi-structured interviews. Through multiple regression analysis of the questionnaires, it was found that grit and FL achievement significantly and positively correlated with each other and grit significantly predicted FL achievement. The interview results showed that four major factors, namely individual-related factors, significant others, achievement-related experiences, and important external factors, affected grit. These results corroborate the positive role of grit in second language acquisition (SLA) and offer valuable pedagogical insights for L2 educators.

1 Introduction

Grit, a trait characterized by persistent interest and effort towards long-term goals (Duckworth et al. 2007), plays a crucial role in foreign language (FL) achievement, as language learning success is highly dependent on students’ long-term effort and passion (Dörnyei 2020; Dörnyei and Ushioda 2021). Since its introduction by Duckworth et al. (2007), grit has been extensively studied in psychology and education. However, its role in SLA remains under-researched (Shirvan et al. 2022). Moreover, studies on the relationship between grit and FL achievement have reported inconsistent results in SLA. Some studies have established a positive association between grit and FL achievement (e.g., Robins 2019), while others have failed to detect any significant relationship (e.g., Shirvan et al. 2022). Khajavy et al. (2021) suggested that these conflicting results might stem from the use of different grit scales: the Grit-O Scale by Duckworth et al. (2007) and the Grit-S Scale by Duckworth and Quinn (2009). Teimouri et al. (2021) argued that the inconsistent findings might also be attributed to the use of domain-general grit scales that were not tailored to L2 contexts. To address this issue, Teimouri et al. (2022a) developed a language-domain-specific instrument: the L2-Grit Scale, which was validated as a reliable and valid instrument for examining grit and its correlation with FL achievement in their research. However, more studies are required to further determine their relationship using the L2-Grit Scale.

Grit is affected by individual, cultural, and linguistic factors (Sudina and Plonsky 2021; Sudina et al. 2021). Among the studies exploring the relationship between grit and FL achievement, only a few studies (e.g., Hu et al. 2022; Liu and Wang 2021; Wei et al. 2019; Zhao and Wang 2023) have specifically addressed the Chinese L2 context. Furthermore, among the limited studies, most of them concentrated on middle and high school students, with university students receiving less attention. Grit is known to develop with age (Duckworth et al. 2007), and the relationship between grit and academic achievement has been shown to vary across different age groups (Morell et al. 2021). Therefore, the findings of previous studies may not be generalizable to other groups of Chinese EFL learners, thus necessitating additional research on the relationship between Chinese university students’ L2 grit and their FL achievement.

Furthermore, research on the factors affecting grit in L2 learning remains limited, and existing studies have primarily employed quantitative methods (Vela et al. 2018) to look into the relationship between grit and some potential factors, such as teacher’s support, emotion, age, gender and personal best goals (e.g., Derakhshan and Fathi 2024; Khajavy and Aghaee 2024; Teimouri et al. 2022b). While these quantitative investigations have yielded valuable insights, a mixed-methods approach is still needed to provide a holistic view of students’ grit development as argued by Shirvan et al. (2022).

To fill these gaps, the present study used a mixed-methods approach to investigate the relationship between Chinese university EFL students’ grit and their FL achievement by adopting Teimouri et al.’s (2022a) L2-Grit Scale, and explore the factors affecting Chinese university EFL students’ grit.

2 Literature review

2.1 Previous studies on grit in SLA

Duckworth et al. (2007) defined grit as a trait involving perseverance and passion for long-term goals. It includes two components: perseverance of effort (PE) and consistency of interest (CI). PE refers to a person’s ability to sustain effort, and CI is a person’s tendency to maintain interest or enthusiasm for a long time even in the face of challenges and setbacks.

Grit has been studied widely in the fields of psychology and education, but research on its role in SLA is still in its early stages (Keegan 2017; Shirvan et al. 2022). Research has consistently shown grit to be one of the most significant positive personality traits affecting foreign language learning (MacIntyre 2016). Specifically, it positively affects students’ reading habits and vocabulary learning (Kramer et al. 2017) and effectively promotes EFL learners’ success in English learning (Keegan 2017). Furthermore, grit is closely related to motivation and emotion (Teimouri et al. 2022a). Students with higher grit levels show a greater inclination to dedicate time and energy to learning English, and have more confidence in their English ability (Lake 2013). Grittier students are also more willing to communicate in English (Lee and Drajati 2019).

2.2 Grit and FL achievement

Grit and its relationship with academic achievement in various subjects (e.g., Li et al. 2018; Morell et al. 2021) have garnered some attention; however, research on the relationship between grit and FL achievement remains limited and yields conflicting findings. Positive association between grit and FL achievement has been documented among learners from diverse backgrounds, including American English as a Second Language (ESL) learners (Robins 2019), Norwegian EFL learners (Calafato 2024), Iranian EFL learners (Botes et al. 2024; Fathi and Hejazi 2024; Teimouri et al. 2022a, 2022b), Chinese EFL learners (Hu et al. 2022; Jiang et al. 2019; Liu and Wang 2021; Wei et al. 2019; Zhao and Wang 2023), Chinese secondary German-as-a-FL learners (Li and Yang 2024) and Arabian learners of Chinese as an L2 (Zhao et al. 2024). Nevertheless, some studies found no significant relationship between grit and FL achievement (Khajavy et al. 2021; Khajavy and Aghaee 2024; Li and Yuan 2024; Yamashita 2018). For instance, Yamashita (2018) reported no connection between Japanese students’ grit and their course grades, and PE, the sub-component of grit, was even negatively related to their FL achievement. The inconclusive results from previous studies may be attributed to the application of the domain-general grit scale in the L2 setting (Botes et al. 2024; Khajavy et al. 2021; Sudina et al. 2021). Both Grit-O and Grit-S Scale are domain-general grit measures that do not include any items specific to English language learning (Kramer et al. 2017). Researchers, therefore, called for a language-domain-specific grit scale to measure grit within the L2 learning environment. Teimouri et al. (2022a) developed a 9-item L2-Grit Scale to measure EFL learners’ grit in SLA, and found that L2 grit had a significantly stronger association with EFL learners’ FL achievement than the domain-general grit. However, to confirm the relationship between L2 grit and FL achievement across a diverse range of EFL learners, further work using the 9-item L2-Grit Scale is still required.

2.3 Factors affecting grit

Researchers in psychology and education have attempted to identify factors that affect grit. Intrinsic motivation and a growth mindset have been found to be positively associated with grit (Goodman et al. 2011; Shirvan et al. 2022). Additionally, happiness, positive emotions, a sense of meaning in life, well-being, hope, life satisfaction and mindfulness, have all been shown to have a positive impact on grit (Vela et al. 2018). Situational factors (e.g. future career, social needs and reputation of English majors) and personality-based factors (e.g. interest and life goals) have been found to impact EFL learners’ level of grit (Gyamfi and Lai 2020). Strengthening ties between family, community, college and students along with fostering a positive campus atmosphere could also help improve students’ grit (Dunn 2018; O’Neal et al. 2016). In Sriram et al.’s (2018) research, five factors were identified as significantly contributing to college students’ grit: others-focused purpose, success-focused purpose, time spent in academic activities and socializing, and religion. Interestingly, experiences of failure have also been shown to enhance one’s grit (DiMenichi and Richmond 2015).

However, the factors affecting grit in the L2 context have not been systematically investigated. What’s more, most of the previous studies have relied heavily on quantitative methods, and there is a lack of qualitative research to deepen our understanding of the complexity of contextual influence on grit (Shirvan et al. 2022).

To conclude, the literature review has revealed several gaps that this study attempts to fill: (1) inconsistent results have led to a vague association between grit and FL achievement. (2) the relationship between grit and FL achievement among Chinese university EFL learners has been under-researched; (3) In SLA, most studies have used Grit-O Scale or Grit-S Scale to measure grit until the validation of an L2-specific grit scale has been recently called for (Kramer et al. 2017; Teimouri et al. 2022a; Wei et al. 2019). Although the use of the L2-grit scale is increasing, further research is still needed to expand our understanding of grit in SLA; (4) few qualitative studies have investigated the factors affecting grit by eliciting students’ perspectives.

Therefore, this research examined the relationship between grit and FL achievement among Chinese university EFL students by using Teimouri et al.’s (2022a) L2-Grit Scale and also explored the factors affecting students’ grit. The following research questions were formulated to guide this investigation:

What is the relationship between Chinese university EFL students’ grit and their FL achievement?

What are the main factors affecting Chinese university EFL students’ grit in their English learning?

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach for data collection and analysis (Creswell and Clark 2011). The quantitative data of the study was used to investigate the relationship between grit and FL achievement through correlational and regression analysis. In this study, the EFL students’ scores of TEM-4 (Test for English Majors-Band 4) were used as the measure of their FL achievement. TEM-4 is a national standardized English proficiency test for all Chinese university English majors taken after their second academic year. The examination contains six sections, including dictation, listening, grammar and vocabulary, cloze test, reading comprehension and writing.

The qualitative data was used to identify the factors affecting Chinese university EFL students’ L2 grit. As noted by Wei et al. (2020), there was no well-established framework regarding the influential factors on grit. Therefore, the qualitative part of the study was guided by the grounded theory to explore and summarize the factors that affected Chinese university EFL students’ grit in their English learning. Grounded theory is a qualitative research methodology that constructs theory inductively, from bottom to top (Chen 1999). Researchers typically commence their investigation without preconceived theoretical assumptions. They immerse themselves in real-life scenarios, gather and organize data, analyze and synthesize the findings, and ultimately develop a systematic theory based on the data. The pivotal aspect of grounded theory is the process of coding data, which involves labeling data fragments, followed by classifying, summarizing and explaining each piece of data.

3.2 Participants

The present study focused on the third- and fourth-year English major students from a prestigious university in Guangdong, China. The university had 285 third-year and 318 fourth-year English major students. A total of 260 students responded to the questionnaires, yielding a response rate of 43.1 %. However, four participants were excluded from the analysis because they did not provide their scores for TEM-4. Consequently, the final sample comprised 256 English majors, including 24 males and 232 females, who were either in their third (46 %) or fourth (54 %) year of study. The high proportion of females in our sample reflects the common gender imbalance among English majors in Chinese universities. Additionally, 35 of the participants were selected through purposive sampling to participate in the semi-structured interviews. All participants were native Chinese Mandarin speakers, aged from 20 to 22 years (M = 20.75; SD = 0.884), with approximately 9–12 years of English learning experience.

3.3 Instruments

A questionnaire was used to collect data of participants’ demographic information (e.g. age, gender, grade and specialism), grit and scores of TEM-4.

The L2-Grit Scale was directly adopted without modifications from Teimouri et al.’s (2022a) study, which contains two sub-scales measuring perseverance of effort (5 items, e.g., “I am a diligent English language learner”) and consistency of interest (4 items, e.g., “I think I have lost my interest in learning English”) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not like me at all) to 5 (very much like me).

To test the reliability of the L2-Grit Scale, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was considered, with 0.830 for the 9-item overall grit scale, and 0.880 and 0.750 for PE and CI respectively, indicating that both the overall grit scale and its two sub-scales were reliable.

To ensure that the items in the L2-Grit Scale were fully understood, they were translated into Chinese by the authors. Then the Chinese version of the scale was back-translated into English. After that, the original version of the scale and its back-translated version were compared and examined by the authors to finalize the Chinese version of the L2-Grit Scale. Finally, a pilot study was conducted to assess the accuracy of the scale’s wording and the time required to complete the survey.

3.4 Data collection and analysis

The questionnaire was published at Wenjuanxing.com, a widely used free online survey website in China. The survey remained open for one week. Completion of the questionnaire was voluntary and the participants were assured of anonymity. Consent forms were signed. There was no upper time limit for answering the questionnaire. The completion time for the questionnaire ranged from 1.18 min to 11.42 min, with an average of 2.54 min (SD = 1.46). Qualitative data was collected through semi-structured one-to-one interviews, each lasting between 30 min and 1.5 h. The interviews were conducted in Mandarin Chinese to ensure clear and accurate communication. Before the formal interview, the researchers developed a preliminary interview protocol informed by existing literature on factors influencing students’ grit. To refine this protocol, a pilot interview was conducted with four students. Their feedback was instrumental in making further adjustments to the interview outline. After making necessary adjustments, the researchers invited 35 participants to take part in the formal interview, with informed consent obtained from each participant.

The quantitative data was analyzed with SPSS 20 and the qualitative data was coded with Nvivo 11. More specifically, Pearson correlation analysis was initially conducted to gain insights into the relationship between grit and FL achievement. Subsequently, multiple linear regression analysis was performed to test the predictive power of grit on FL achievement.

The qualitative data were coded, classified and synthesized using NVivo 11 to identify the factors affecting students’ grit. Three major types of coding (open coding, axial coding and selective coding) were involved (Strauss 1987). In the open coding stage, the transcribed texts were read in details, during which phenomena affecting students’ grit were extracted and labeled, and they were then classified to summarize the child nodes. In the axial coding stage, connections among the child nodes were established, forming the higher-level parent nodes. Finally, in the selective coding stage, through systematic analysis, categories were extracted from the parent nodes, and a theoretical model of the factors influencing grit was established. To ensure the validity of data coding, the authors first independently coded 25 percent of the transcripts and then discussed them until a final consensus was reached. It was found that the coding consistency among the coders was as high as 94 %. The third author then finished the rest of the coding.

4 Results

4.1 The profiles of Chinese university EFL students’ grit

As shown in Table 1, the distributions of grit and FL achievement closely resembled a normal distribution based on skewness and kurtosis values. The participants had a moderate level of grit (M = 3.144, SD = 0.656). The level of PE (M = 3.087, SD = 0.802) and CI (M = 3.216, SD = 0.793) were also moderate, but the mean score of PE (M = 3.087) was slightly lower than that of CI (M = 3.216).

Descriptive statistics and normality for key variables.

| N | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grit | 256 | 1.330 | 4.890 | 3.144 | 0.656 | −0.139 (0.152) | −0.457 (0.303) |

| PE | 256 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 3.087 | 0.802 | −0.012 (0.152) | −0.508 (0.303) |

| CI | 256 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 3.216 | 0.793 | −0.577 (0.152) | 0.062 (0.303) |

| FL achievement | 256 | 58.000 | 90.000 | 76.890 | 6.844 | −0.192 (0.152) | −0.415 (0.303) |

-

Note. PE = perseverance of effort; CI = consistency of interest; FL achievement = foreign language achievement.

Standard deviations (0.656, 0.802, 0.793) indicated small variations in the students’ scores on their grit and its two sub-constructs. When considering the maximum and minimum scores, it was observed that some students experienced a very high level of grit in their English learning, while others reported little or no grit, highlighting significant individual differences in grit levels among Chinese university EFL students.

4.2 Relations between grit and FL achievement

A series of Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to explore the associations between grit, its two sub-components and FL achievement (Table 2). The benchmark of effect size proposed by Plonsky and Oswald (2014) was adopted: for correlation coefficients, values of rs (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) close to 0.25 could be considered small, 0.40 medium, and 0.60 large.

Pearson correlations between grit, its two sub-components and FL achievement.

| Grit | PE | CI | |||

|

|

|||||

| FL achievement | Pearson correlation | 0.634*** | 0.570*** | 0.458*** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| N | 256 | 256 | 256 | ||

| 95 % confidence intervals | Lower | 0.573 | 0.493 | 0.370 | |

| Upper | 0.688 | 0.648 | 0.550 | ||

-

Note. PE = perseverance of effort; CI = consistency of interest; FL achievement = foreign language achievement *** Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

Table 2 revealed a strong positive correlation between grit and FL achievement (r = 0.634, p < 0.001), which suggested that EFL learners with higher levels of grit were more likely to get higher FL achievement. Regarding the two sub-components of grit, PE was found to be highly and positively related to FL achievement (r = 0.570, p < 0.001), and CI was moderately and positively related to FL achievement (r = 0.458, p < 0.001). PE showing a much stronger relationship with FL achievement than CI indicated the greater significance of effort-making in the context of language learning.

4.3 The predictive effect of grit on FL achievement

The standard multiple regression analysis was conducted with PE and CI as the predictors and FL achievement as the dependent variable (Table 3). The Durbin-Watson value of 1.997, which was very close to the ideal value of 2, suggested that there was no significant autocorrelation in the data. Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value of 1.134 was well below the commonly accepted threshold for indicating multicollinearity, which is typically set at 5. Therefore, our model did not have concerns regarding autocorrelation or multicollinearity. The analysis of normality and residual plots suggested linearity and homoscedasticity. The results showed that Chinese students’ grit significantly predicted their FL achievement, which explained 40.4 % of the variance (R2unadjusted = 0.404, β = 0.635, F = 85.587, p < 0.001). The strongest predictor was PE (β = 0.468, p < 0.001, [3.128, 4.866]) followed by CI (β = 0.298, p < 0.001, [1.689, 3.446]). Participants’ FL achievement increased 3.997 points for each unit increase in PE and 2.568 for each unit increase in CI.

Predictive effect of grit on FL achievement.

| Predicators | R | R2 | B | F | β | t | 95 % confidence intervals for B | Tolerance | VIF | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 0.635 | 0.404 | 3.997 | 85.587*** | 0.468 | 9.056*** | [3.128, 4.866] | 0.882 | 1.134 | 1.997 |

| CI | 2.568 | 0.298 | 5.757*** | [1.689, 3.446] |

-

Note. *** indicates p < 0.001 Dependent variable: FL achievement.

4.4 Factors affecting students’ grit in English learning

The qualitative data revealed four categories of factors that affected students’ grit: individual related factors, significant others, achievement-related experiences and important external factors (Table 4).

Factors affecting students’ grit.

| Categories (4) | Nodes (12) | References (282) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-related factors (total) references: (117) | (1) goals | 45 |

| (2) interest | 23 | |

| (3) personal experience | 22 | |

| (4) character | 19 | |

| (5) personal beliefs | 8 | |

| Significant others (91) | (1) peers | 38 |

| (2) teachers | 36 | |

| (3) parents | 17 | |

| Achievement-related experiences (59) | (1) tangible achievements | 33 |

| (2) intangible achievements | 26 | |

| Important external factors (15) | (1) task difficulty | 8 |

| (2) learning environment and atmosphere | 7 |

Individual-related factors emerged as the most prevalent influences on grit, including goals (45), interest (23), personal experience (22), character (19) and personal beliefs (8). Among these factors, goals including academic goals and career goals were most frequently mentioned by the interviewees as having a significant impact on their grit. This is exemplified by the following interview excerpt,

The goals I set for myself include grade ranking, GPA, TEM-4, TEM-8, etc. If I want to achieve these goals, I have to study hard, so these goals can push me to study hard. (participant 2)

Interest, personal experience, character and personal beliefs were also frequently mentioned. Participants who possessed a positive character or held strong personal beliefs were observed to be grittier, demonstrating an ability to continuously challenge themselves despite obstacles. In contrast, the passive participants often struggled to persevere and maintain their enthusiasm, as one of the participants revealed,

I’m lazy, and I only have temporary enthusiasm. Every time I encounter difficulties or setbacks, I want to give up. (p27)

Many participants acknowledged that their grit was deeply influenced by those around them, especially their peers (38), teachers (36) and parents (17). Peers influenced them through pressure, companionship, and inspiration, and teachers and parents impacted them through their expectations and encouragement. Furthermore, participants often viewed their peers and teachers as role models. In particular, teachers’ effective teaching methods played a key role in sparking students’ interest in learning English and motivating them to engage in classroom activities.

If I like this teacher’s teaching method, I will be more interested in his or her class, and accordingly, I will put more effort into it. (p15)

Achievement-related experiences also had a great impact on students’ grit and it consisted of tangible achievements (33) and intangible achievements (26). Tangible achievements refer to desired academic outcomes and concrete benefits that students obtained from what they were doing, while intangible achievements refer to less visible yet profoundly influential gains, such as a sense of achievement, recognition, and affirmation from others, as illustrated in the following quote.

If others give me some affirmation and recognition, I will be very happy and feel that I am actually valuable. In this way, I will like English more and become grittier to learn English. (p16)

External factors, such as task difficulty (8) and learning environment and atmosphere (7), affected students’ grit as well. If the task was too difficult, students would not obtain a sense of achievement in the task. Over time, they would lose interest in what they were doing and might eventually give it up. Whereas a good learning environment and atmosphere could stimulate the students’ learning enthusiasm and nurture their grit.

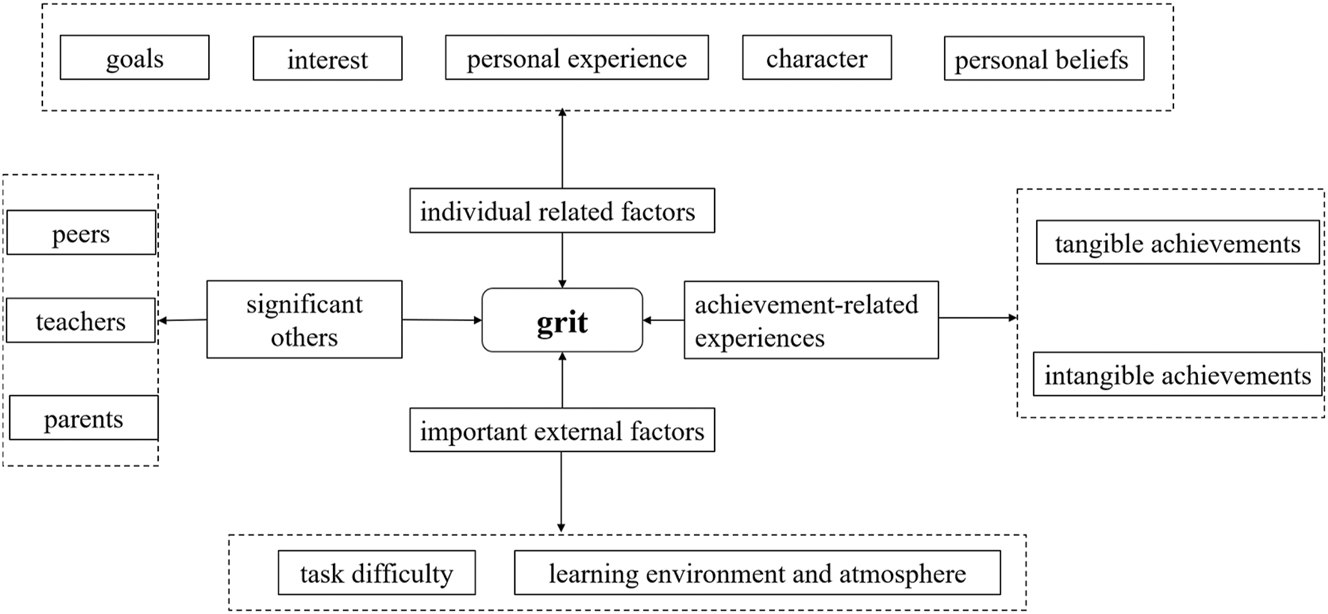

Based on the qualitative data, a model of the factors affecting EFL students’ grit was developed (Figure 1). The model includes individual-related factors (goals, interest, character, personal experience and beliefs), significant others (peers, parents, and teachers), achievement-related experiences (tangible and intangible achievements), and important external factors (task difficulty and learning environment and atmosphere). The model demonstrated how these factors collectively contributed to grit among EFL students.

Model of the influencing factors of grit.

5 Discussion

5.1 The predictive power of grit in FL achievement

This study reported that the participants’ grit was positively and highly related to their FL achievement, which was in line with several previous studies (e.g., Calafato 2024; Robins 2019; Teimouri et al. 2022a; Wei et al. 2019; Zhao and Wang 2023). Nevertheless, some studies failed to establish such a significantly positive relationship (e.g. Khajavy et al. 2021; Khajavy and Aghaee 2024; Li and Yuan 2024; Yamashita 2018; Zhao et al. 2024), and some even reported weak (Credé et al. 2017) or negative relationships (Climer 2017).

The inconsistent findings may be owing to the use of different measurement tools for grit. Among the most commonly used scales for assessing grit, Teimouri et al.’s (2022a) L2-Grit Scale was introduced relatively late. Many existing studies on grit in SLA have employed domain-general grit scales (Grit-O Scale or Grit-S Scale). However, grit measured by the L2-Grit Scale exhibited a stronger association with FL achievement compared to the domain-general grit scale (Teimouri et al. 2022a). Li and Yang (2024) compared how domain-general grit and L2-specific grit predicted FL achievement, and found that the L2-specific grit scale improved its predictive validity. This implied that using different instruments would lead to discrepancies in the results. Another reason might be that the predictive role of grit in FL achievement may vary across different contexts, languages, and participants (Zhao et al. 2024).

Considering the sub-constructs of grit, it was found in this study that perseverance of effort was a stronger predictor of FL achievement than consistency of interest. The results are consistent with previous studies (Calafato 2024; Teimouri et al. 2022a; Zhao and Wang 2023). One possible reason is cultural influence. Research (e.g. Biggs 1996; Jin and Cortazzi 2011) has shown that in Asian cultures where effort is highly respected and encouraged, Asian students tend to value effort more than interest. Most Chinese students are hard-working and consider good academic performance as their primary goal. Despite their lack of interest in certain activities, Chinese learners tend to persist in making efforts to achieve their goals. The interviews with some participants in this study lent support to this explanation.

5.2 Factors on grit

Based on the qualitative data, four categories of factors have been identified, namely individual-related factors, significant others, achievement-related experiences and important external factors.

5.3 Individual-related factors

Individual-related factors including goals, interest, character, personal experience, and personal beliefs, greatly impacted students’ grit. Among these factors, the goal was the most frequently mentioned by participants. This finding is not surprising given that L2 grit itself is goal-oriented in nature (Solhi et al. 2023), and PE is a significant positive predictor of personal best goals (Khajavy and Aghaee 2024). Clear academic goals provided the impetus for learners to persist and sustain interest even in the face of challenges and failures (Gyamfi and Lai 2020). Interest, a core component of grit, was another frequently mentioned factor, which lent support to the fact that overall L2 grit represented learners’ sustained interest in L2 learning (Li and Yang 2024; Taşpinar and Külekçi 2018). Our findings align with Ebadi et al.’s study (2018]), which demonstrated that both goal setting and interest were pivotal factors in L2 grit. Von Culin et al. (2014) also posited that individuals with higher levels of grit were more inclined to seek meaning in their activities, and goal-oriented interest may foster grit by motivating sustained effort.

Grit, a personality trait, was affected by learners’ character and personal experience. Positive and ambitious learners tended to exhibit greater resilience compared to those who were perceived as lazy. Learners who had experience of overcoming difficulties to achieve success often had a heightened awareness of the value and significance of grit. Personal beliefs also played an important role. Learners with a higher level of self-efficacy demonstrated increased perseverance when faced with challenges (Derakhshan and Fathi 2024).

5.4 Significant others

Peers, parents and teachers played important roles in students’ learning and development, which echoes others’ findings (e.g., Derakhshan et al. 2023; O’Neal et al. 2016; Sadoughi and Hejazi 2023). Peer learning may help learners overcome indolence and difficulties and stimulate learners’ learning motivation. At the same time, peers’ outstanding performance and diligence may also inspire learners to persist in learning. The study revealed that teachers’ support, appreciation, and teaching skills significantly contributed to the development of learners’ grit, corroborating findings from prior research (Derakhshan et al. 2023; Hejazi and Sadoughi 2023). Furthermore, parental support, encouragement, and expectations also played a crucial role in fostering learners’ grit. Learners lacking clear goals can benefit from such parental expectations and encouragement, as these may increase their motivation to persist and help them see the significance of L2 learning. The significant role that teachers and parents play in the development of learners’ grit can be attributed to the emotional, instrumental, and appraisal support they provide, which fosters enjoyment and sustains learners’ interest in foreign language learning (Hejazi and Sadoughi 2023).

5.5 Achievement-related experiences

Interviews revealed that tangible achievements boosted EFL students’ grit, aligning with the previous research (Wei et al. 2020) which indicated better exam grades breed grit. One plausible explanation could be that when students obtain tangible accomplishments, such as achieving high grades in exams, they would experience a sense of fulfilment and develop a heightened interest in L2 learning. This increased interest may further stimulate greater passion and effort in their studies. Apart from tangible achievements, intangible accomplishments, such as a sense of achievement and recognition from others, also built students’ grit by boosting self-confidence, fostering positive attitudes, and validating their past efforts.

5.6 Task difficulty and learning environment

Other factors, such as task difficulty and learning environment also affected students’ grit. Overly difficult tasks may dampen students’ perseverance and interest in learning English, which means that teachers should assign achievable tasks to develop students’ self-efficacy. It is also worth noting that a good learning environment could promote students’ grit in language learning (O’Neal et al. 2016; Shirvan et al. 2022; Wei et al. 2019). As mentioned earlier, industrious peers provided both pressures and incentives, driving learners to keep gritty.

Overall, the above-mentioned factors do not operate in isolation but interact with one another. In other words, the grit level of university EFL students is the product of the intricate interplay between internal and external factors. This suggests that students’ grit can be enhanced both directly and indirectly through a multitude of pathways.

6 Conclusions

Employing a mixed-methods approach, this study examined the relationship between students’ grit and their FL achievement, and further explored the factors influencing their grit. The findings revealed that Chinese university EFL students displayed a moderate level of grit, including perseverance of effort and consistency of interest. This suggests that the students were generally able to sustain efforts and maintain interest in order to achieve their goals in English learning.

Additionally, this study found significantly positive correlations between students’ grit and their FL achievement, implying that students with higher levels of grit were more likely to achieve higher levels of FL proficiency. Furthermore, grit was found to have a significant positive predictive effect on FL achievement, indicating that students’ FL achievement could be predicted based on their grit levels.

Finally, qualitative analysis of interview data unveiled the factors that affected university EFL students’ grit, leading to the development of a grit model that encapsulates these influences.

This study has both methodological and pedagogical implications. Methodologically, while previous studies mostly used correlation analysis to explore the relationship between grit and FL achievement, this study adopted both correlation analysis and multiple linear regression analysis. This furthered our understanding of the role of grit in FL achievement, since it looked deeper into how grit and FL achievement were related. Furthermore, unlike most previous research adopting quantitative methods to investigate the factors affecting grit, the current research used a qualitative method, offering a more comprehensive picture of the grit’s influencing factors and providing a more nuanced perspective on the contributions of this personality trait to academic success in foreign language contexts. Pedagogically, understanding grit’s predictive role in FL achievement motivates teachers to cultivate students’ grit in English learning through improved teaching skills, exemplary role-modelling, and attainable task assignments. While this study was conducted in China, the findings have implications for EFL learners in other Asian or broader cultural contexts.

Although this study offers valuable insights into the role of grit in second language acquisition, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the participants of this research were solely Chinese university English majors, which inevitably led to a predominantly female sample. This constrained the generalizability of the findings to other Chinese EFL learner groups and students in other EFL contexts. Future studies could be conducted by involving different EFL learner groups in diverse EFL contexts. In addition, the qualitative data in this study was gathered only through semi-structured interviews, future research could enrich the data collection by incorporating observations and focus group discussions, offering a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the factors influencing students’ grit. Finally, while grit was defined by Duckworth et al. (2007) as perseverance and passion for long-term goals, the cross-sectional design of this study may not fully capture its long-term nature (Muenks et al. 2017). To better understand the development of grit over time, a longitudinal design is highly recommended for future studies.

Funding source: The Project of the National Social Science Fund of China: Task Design and Learning Mechanism from the Perspectives of Cognitive Complexity and Individual Differences

Award Identifier / Grant number: 23BYY157

Funding source: The Key Research and Innovation Project for Graduate Students in Guangdong University of Foreign Studies

Award Identifier / Grant number: 24GWCXXM-014

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the Project of the National Social Science Fund of China: Task Design and Learning Mechanism from the Perspectives of Cognitive Complexity and Individual Differences (no. 23BYY157) and the Key Research and Innovation Project for Graduate Students in Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (no. 24GWCXXM-014).

References

Biggs, John B. 1996. Western misperceptions of the Confucian-heritage learning culture. In David Watkins & John B. Biggs (eds.), The Chinese learner: Cultural, psychological, and contextual influences. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, the University of Hong Kong/Australian Council for Educational Research.Search in Google Scholar

Botes, Elouise, M. Azari Noughabi, Seyed Mohammad Reza Amirian & Samuel Greiff. 2024. New wine in new bottles? L2 Grit in comparison to domain-general grit, conscientiousness, and cognitive ability as a predictor of language learning. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2294120.Search in Google Scholar

Calafato, Raees. 2024. The moderating effect of multilingualism on the relationship between EFL learners’ grit, enjoyment, and literacy achievement. International Journal of Bilingualism 13670069231225729. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069231225729.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Xiangming. 1999. Grounded theory: Its train of thought and methods. Educational Research and Experiment 4. 58–63.Search in Google Scholar

Climer, Steven L. 2017. A quantitative study of grit as a predictor of online course success at a suburban Michigan community college. Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University, San Diego.Search in Google Scholar

Credé, Marcus, Michael C. Tynan & Peter D. Harms. 2017. Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113. 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000102.Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, John W. & Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. London: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Von Culin, Katherine, Eli Tsukayama & Angela Duckworth. 2014. Unpacking grit: Motivational correlates of perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Positive Psychology 9. 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.898320.Search in Google Scholar

Derakhshan, Ali & Jalil Fathi. 2024. Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: The mediating role of online learning self-efficacy. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 33(4). 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00745-x.Search in Google Scholar

Derakhshan, Ali, Mehdi Solhi & Mostafa Azari Noughabi. 2023. An investigation into the association between student-perceived affective teacher variables and students’ L2-grit. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2212644.Search in Google Scholar

DiMenichi, Brynne C. & Lauren L. Richmond. 2015. Reflecting on past failures leads to increased perseverance and sustained attention. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 27(2). 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2014.995104.Search in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2020. Innovations and challenges in language learning motivation. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429485893Search in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán & Ema Ushioda. 2021. Teaching and researching motivation. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351006743Search in Google Scholar

Duckworth, Angela Lee, Christopher Peterson, Michael D Matthews & Dennis R. Kelly. 2007. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92. 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087.Search in Google Scholar

Duckworth, Angela Lee & Patrick D. Quinn. 2009. Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment 91(2). 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290.Search in Google Scholar

Dunn, Kelly M. 2018. Investigating parenting style and college student grit at a private mid-sized New England university. Doctoral dissertation, Johnson and Wales University, Florida.Search in Google Scholar

Ebadi, Saman, Hiwa Weisi & Zahra Khaksar. 2018. Developing an Iranian ELT context-specific grit instrument. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 47(4). 975–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-018-9571-x.Search in Google Scholar

Fathi, Jalil & S. Yahya Hejazi. 2024. Ideal L2 self and foreign language achievement: The mediating roles of L2 grit and foreign language enjoyment. Current Psychology 43(12). 10606–10620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05187-8.Search in Google Scholar

Gyamfi, George & Yuanxing Lai. 2020. Beyond motivation: Investigating Thai English major students’ grit. PASAA: Journal of Language Teaching and Learning in Thailand 60. 60–96.10.58837/CHULA.PASAA.60.1.3Search in Google Scholar

Goodman, Suki, Thania Jaffer, Mira Keresztesi, Fahrin Mamdani, Dolly Mokgatle, Mazvita Musariri, Anton Schlechter & Joao Pires. 2011. An investigation of the relationship between students’ motivation and academic performance as mediated by effort. South African Journal of Psychology 41(3). 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631104100311.Search in Google Scholar

Hejazi, S. Yahya & Majid Sadoughi. 2023. How does teacher support contribute to learners’ grit? The role of learning enjoyment. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 17(3). 593–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2022.2098961.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Xiaoyu, Gurnam Kaur Sidhu & Xin Lu. 2022. Relationship between growth mindset and English language performance among Chinese EFL university students: The mediating roles of grit and foreign language enjoyment. Frontiers in Psychology 13. 935506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.935506.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Wen, Ziyao Xiao, Yanan Liu, Kening Guo, Jiang Jiang & Xiaopeng Du. 2019. Reciprocal relations between grit and academic achievement: A longitudinal study. Learning and Individual Differences 71. 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.02.004.Search in Google Scholar

Jin, Lixian & Martin Cortazzi. 2011. Researching Chinese learners: Skills, perceptions and intercultural adaptations. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230299481Search in Google Scholar

Keegan, Kelly. 2017. Identifying and building grit in language learners. English Teaching Forum 55(3). 2–9.Search in Google Scholar

Khajavy, Gholam Hassan & Elham Aghaee. 2024. The contribution of grit, emotions and personal bests to foreign language learning. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45(6). 2300–2314. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2047192.Search in Google Scholar

Khajavy, Gholam Hassan, Peter D. MacIntyre & Jamal Hariri. 2021. A closer look at grit and language mindset as predictors of foreign language achievement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 43(2). 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263120000480.Search in Google Scholar

Kramer, Brandon, Stuart McLean & Eric Shepherd Martin. 2017. Student grittiness: A pilot study investigating scholarly persistence in EFL classrooms. Journal of Osaka Jogakuin College 47. 25–41.Search in Google Scholar

Lake, Jeffrey. 2013. Positive L2 self: Linking positive psychology with L2 motivation. In Matthew Apple, Dexter Da Silva & Terry Fellner (eds.), Language learning motivation in Japan, 71–225. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783090518-015Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Ju Seong & Nur Arifah Drajati. 2019. Affective variables and informal digital learning of English: Keys to willingness to communicate in a second language. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 35(5). 168–182. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5177.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Chengchen & Yuan Yang. 2024. Domain-general grit and domain-specific grit: Conceptual structures, measurement, and associations with the achievement of German as a foreign language. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 62(4). 1513–1537. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2022-0196.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jia & Fan Yuan. 2024. Does engagement with feedback matter? Unveiling the impact of learner engagement and grit on EFL learners’ English writing achievements. Language Teaching Research. 13621688241257865. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241257865.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jingguang, Yajun Zhao, Feng Kong, Shuailing Du, Suyong Yang & Song Wang. 2018. Psychometric assessment of the short grit scale among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 36(3). 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916674858.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Eerdemutu & Junju Wang. 2021. Examining the relationship between grit and foreign language performance: Enjoyment and anxiety as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology 12. 666892. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.666892.Search in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter. 2016. So far so good: An overview of positive psychology and its contributions to SLA. In Gabryś-Barker Danuta & D. Gałajda (eds.), Positive psychology perspectives on foreign language learning and teaching, 3–20. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-32954-3_1Search in Google Scholar

Morell, Monica, Ji Seung Yang, Jessica R. Gladstone, Lara Turci Faust, Allan Wigfield & Hyo Jin Lim. 2021. Grit: The long and short of it. Journal of Educational Psychology 113(5). 1038. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000594.Search in Google Scholar

Muenks, Katherine, Allan Wigfield, Ji Seung Yang & Colleen R. O’Neal. 2017. How true is grit? Assessing its relations to high school and college students’ personality characteristics, self-regulation, engagement, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology 109(5). 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000153.Search in Google Scholar

O’Neal, Colleen, Michelle M. Espino, Antoinette Goldthrite, Molly F. Morin, Lynsey Weston, Pamela Hernandez & Amy Fuhrmann. 2016. Grit under duress: Stress, strengths, and academic success among non-citizen and citizen Latina/o first-generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 38(4). 446–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986316660775.Search in Google Scholar

Plonsky, Luke & Frederick Oswald. 2014. How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning 64(4). 878–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079.Search in Google Scholar

Robins, Seth. 2019. Academic achievement and retention among ESL learners: A study of grit in an online context. Doctoral dissertation, University of West Georgia, Carrolton.Search in Google Scholar

Shirvan, Majid Elahi, Tahereh Taherian & Elham Yazdanmehr. 2022. L2 grit: A longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis-curve of factors model. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 44(5). 1449–1476. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263121000590.Search in Google Scholar

Sadoughi, Majid & Yahya Hejazi. 2023. Teacher support, growth language mindset, and academic engagement: The mediating role of L2 grit. Studies in Educational Evaluation 77. 101251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2023.101251.Search in Google Scholar

Solhi, Mehdi, Ali Derakhshan & Büşra Ünsal. 2023. Associations between EFL students’ L2 grit, boredom coping strategies, and emotion regulation strategies: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2175834.Search in Google Scholar

Sriram, Rishi, Perry Glanzer & Cara Cliburn Allen. 2018. What contributes to self-control and grit? The key factors in college students. Journal of College Student Development 59(3). 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0026.Search in Google Scholar

Strauss, Anselm. 1987. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511557842Search in Google Scholar

Sudina, Ekaterina, Jason Brown, Brien Datzman, Yukiko Oki, Katherine Song, Robert Cavanaugh, Bala Thiruchelvam & Luke Plonsky. 2021. Language-specific grit: Exploring psychometric properties, predictive validity and differences across contexts. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 15(4). 334–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2020.1802468.Search in Google Scholar

Sudina, Ekaterina & Luke Plonsky. 2021. Academic perseverance in foreign language learning: An investigation of language‐specific grit and its conceptual correlates. The Modern Language Journal 105(4). 829–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12738.Search in Google Scholar

Taşpinar, Havva Kurt & Gülşah Külekçi. 2018. Grit: An essential ingredient of success in the EFL classroom. International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching 6. 208–226.10.18298/ijlet.3137Search in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Yasser, Luke Plonsky & Farhad Tabandeh. 2022a. L2 grit: Passion and perseverance for second language learning. Language Teaching Research 26(5). 893–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820921895.Search in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Yasser, Ekaterina Sudina & Luke Plonsky. 2021. On domain-specific conceptualization and measurement of grit in L2 learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning 3(2). 156–165. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/3/2/10.Search in Google Scholar

Teimouri, Yasser, Farhad Tabandeh & Somayeh Tahmouresi. 2022b. The Hare and the Tortoise: The race on the course of L2 learning. The Modern Language Journal 106(4). 764–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12806.Search in Google Scholar

Vela, Javier Cavazos, Wayne D. Smith, James F. Whittenberg, Rebekah Guardiola & Miranda Savage. 2018. Positive psychology factors as predictors of Latina/o college students’ psychological grit. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 46(1). 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12089.Search in Google Scholar

Wei, Hongjun, Kaixuan Gao & Wenchao Wang. 2019. Understanding the relationship between grit and foreign language performance among middle school students: The roles of foreign language enjoyment and classroom environment. Frontiers in Psychology 10. 1508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01508.Search in Google Scholar

Wei, Rining, He Liu & Shijie Wang. 2020. Exploring L2 grit in the Chinese EFL context. System 93. 102295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102295.Search in Google Scholar

Yamashita, Takuhiro. 2018. Grit and second language acquisition: Can passion and perseverance predict performance in Japanese language learning? (MA thesis). Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Amherst.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Xian & Danping Wang. 2023. Grit, emotions, and their effects on ethnic minority students’ English language learning achievements: A structural equation modelling analysis. System 113. 102979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.102979.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Xian, Peijian Paul Sun & Gong Man. 2024. The merit of grit and emotions in L2 Chinese online language achievement: A case of Arabian students. International Journal of Multilingualism 21(3). 1653–1679. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2023.2202403.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.