Abstract

Active listening, foundational for meaningful social interaction, plays a pivotal role in enhancing interactional competence (IC) during dialogues. Despite its importance, current second language (L2) assessments, such as the TOEFL iBT and the Business English Certificate (BEC) Preliminary, notably does not include active listening in their evaluation metrics. The research presented here contributes significantly to this discourse by foregrounding the imperative of listener responses (LRs) in L2 communication and the diverse interactional functions they serve across different cultures. Notably, variations emerge, with Chinese speakers exhibiting more restrained verbal feedback compared to the more vocally expressive English counterparts. This study stands apart by underscoring the necessity of updating current L2 assessment rubrics, which currently prioritize grammatical proficiency, pronunciation, and vocabulary. By weaving in active listening, assessments can become more holistic, capturing more comprehensively a learner’s L2 interactional ability. Through rigorous quantitative and qualitative methodologies, this investigation probes the influence of active listening on BEC speaking test outcomes. Its findings are poised to revolutionize assessment strategies, urging a more encompassing approach that factors in both verbal and non-verbal cues, thereby reflecting genuine linguistic and interactional competence.

1 Introduction

As one of the essential abilities enabling social interaction, active listening has been emphasized in social action engagement. The performance of employing different resources of listener responses (LRs) reflects the cooperation between interlocutors and understanding of others in conversations. In communication, low use of these responses can disrupt interaction. This may lead speakers to question if their messages are understood, impeding effective communication and learning in language learning settings (Xu 2014), which indicates the low production of resources at essential places may lead to barriers to mutual understanding and intersubjectivity (Sacks et al. 1974). Thus, the competence of generating LRs is considered one facet of interactional competence (IC).

However, very few second language assessments up to date have included the rating of active listening as a part of the rubric or scoring process. The active listening aspect was absent in monologue speaking assessments and interactive speaking assessments between test takers and examiners, such as answering examiners’ questions in the TOEFL iBT and repeating a sentence or summarizing a paragraph in an automated speaking setting in PTE Academic. Even paired interactive speaking assessments, such as the Business English Certificate (BEC) Preliminary assessment that targets assessing examinees’ performance of cooperating in conversations in business contexts, still lack the consideration of evaluating active listening ability. Roever and Kasper (2018) argued that for such a paired interactive format in a specific target domain, active listening ability should be taken into account in the assessment rating rubric. Motivated by the research gap, the study includes active listening as one aspect of the paired speaking assessment rating rubric and justifies the impact of this inclusion on the overall scale from the perspectives of statistics and interactional function.

2 Literature review

2.1 Listener responses in communication

The importance of LRs in conversation and second language (L2) communication has been identified by previous research (Carlén 2020; Ross 2018; Shively 2015). When listeners do not hold the current floor, they provide feedback to show various interactional functions, such as acknowledgment, surprise, questioning, and state-of-opinion (Schegloff 1997). Researchers from the perspective of Conversation Analysis (CA) emphasized the function of LRs in sequential contexts according to discrete response tokens. Starting with the investigation of “mm hm” and “yeah”, Jefferson (1983, 1984, 1993) examined the phenomenon of these acknowledgment tokens. With more response tokens having been further studied, which include “uh huh” and “oh” (Drummond and Hopper 1993a, 1993b; Schegloff 2009), “wow” and “good” (Goodwin 1986), and “okay” (Beach 1993; Pillet-Shore 2003), the different functions of LR tokens in interactions have raised the awareness of L2 pragmatics acquisition.

LR, as a potential indicator of L2 learners’ IC, indicates actual language ability and how interlocutors should frame themselves in daily communication (Ross 2018). Employment of L2 LR is one of the key facets of developing L2 IC. Therefore, the ability to perform L2 LR reflects the development of IC in L2 social interactions (Shively 2015). Previous studies have shown that active LRs facilitate the construction of both verbal and non-verbal forms. For instance, Eiswirth (2020) found that female speakers generated more active LRs in social talks related to daily matters compared to male speakers in verbal responses. Also, as second language proficiency improves, interactants exhibit increasing mutuality and engagement in their interactions via the more active deployment of LRs (Galaczi 2014). The results in Carlén (2020) revealed that during a certain period of study abroad, L2 English speakers could improve their overall usage of LRs when engaging with ESL instructors in L2 classroom activities. For multi-modality listener responses in the L2 assessment context, Lam (2021) compared L2 learners with high proficiency and low proficiency through a CA perspective, and concluded that the high-proficiency L2 learners are able to generate more variety of listener responses during an oral proficiency test.

Although the existence of LRs is considered universal, there are still some cross-linguistic variations in LRs. Based on the overall frequency and functions of tokens in Chinese conversations, Chinese L1 speakers are often considered as “rare users” of LR tokens in social interactions due to culture and politeness in social relationships (Bavelas et al. 2002; Clancy et al. 1996; Smith et al. 2005; Tao and Thompson 1991). Chinese speakers show a broad tendency to rely on non-verbal or brief non-word vocalizations in their intercultural communication in English L2 conversation, such as the production of “en en” in Mandarin Chinese conversation (Clancy et al. 1996). On the contrary, American, Australian, and British English speakers tend to favor the active production of LRs in social communication. Therefore, when Chinese L1 speakers socialize in the target L2 English environment, the ability to adopt more “active” LRs has become a crucial challenge (Weger et al. 2014). In some occasions, the improper usage of LRs may lead to misunderstandings in significant contexts during social interactions, such as receiving medical advice, participating in academic discussions, and communicating under different domains (Dai 2022).

For different scenarios, LRs demonstrate significance in communication outcomes. In professional communication contexts, active listening is often defined as a technique that involves attentive listening, along with verbal and non-verbal signs of listening such as nodding, eye contact, and appropriate responses (Bodie 2012; Morgan et al. 2017). This ensures clear understanding and shows respect and interest towards the speaker. In counselling, active listening is a foundational skill that goes beyond merely hearing the spoken words. It involves empathetic understanding and genuine attentiveness to the client’s verbal and non-verbal messages. Counselors are trained to listen for the underlying feelings, needs, and concerns, with the aim to understand the client’s perspective without judgment (Kawamichi et al. 2015). This form of listening is therapeutic and helps in building a strong, trust-based relationship between the counselor and the client. In the context of business communication, active listening also plays a crucial role. Here, the focus is on effective communication, problem-solving, and decision-making within a professional setting. Active listening in business involves paying full attention to speakers, understanding their message, clarifying ambiguities, and responding appropriately (Khanna 2020). The goal is often to ensure mutual understanding, facilitate collaboration, and enhance team dynamics. Business professionals might use active listening to negotiate deals, resolve conflicts, lead teams, and build relationships with clients and colleagues. While the empathetic aspect of listening is important, the emphasis might be more on achieving clear, efficient communication and tangible outcomes.

2.2 L2 listener responses in L2 speaking assessment

To assess the ability of L2 IC, active listening is one of the essential facets that need to be considered when conducting language assessments, especially in speaking assessments. With productive components having been taken into account in speaking assessments, such as grammar accuracy, pronunciation, and discourse management (Lam 2021), however, the existence and importance of IC of L2 learners have been largely ignored in speaking assessments (Galaczi and Taylor 2018). Initially, Hall et al. (2011) pointed out that the verbal and non-verbal “moment-to-moment” engagements build the interpretations, which contributes to a deeper meaning of these actions in interactions. For L2 speakers, LRs also varied across different proficiency levels. For example, Galaczi (2014) demonstrated the importance of incorporating listener support strategies and turn-taking management into our understanding of effective communication; both in educational settings and in the context of assessments. Speakers at the C1 level switched roles between speakers and listeners via the production of various listener responses.

This omission of IC leads to a partial examination of the actual ability of L2 learners in language assessments such as IELTS, TOEFL iBT, or PTE Academic, especially when the language assessment scores are used to apply for an overseas degree at a university in English-speaking countries. As a result, L2 learners may encounter interactive difficulties in the target L2 environment, which may cause isolation in socialization in the long run.

In addition to the lack of IC in L2 language assessment, the quality of “active listening” has been ignored in most L2 language speaking assessment rubrics as well. Active listening can be defined as the ability to perform LRs at a proper moment and show various aspects of response to the current content produced by the speaker (Mondada 2011; Shively 2015). Previous studies have shown that active listening ability has an impact on the outcome of discussion in paired tasks or paired discussion in L2 tests (Lam 2021; Ross 2018). Ross (2018) conducted a micro-analysis of the function of LRs in Oral Proficiency Interviews (OPIs) with L2 Japanese learners and revealed that proficiency had an impact on the production of LRs during the interview, yet the relationship between test scores and LRs remained unclear in assessment scoring. Later on, Lam (2021) reported the verbal and non-verbal performance through the Collaborative Task of Cambridge Assessment English and provided a relatively strong justification for the inclusion of active listening ability in English speaking assessment.

2.3 Lack of active listening ability in speaking assessment rubric

Rubric design in mainstream language assessments has mainly focused on grammatical accuracy, pronunciation standardization and vocabulary richness, for example, in TOEFL iBT, PTE Academic, and IELTS (Roever and Ikeda 2022). However, few speaking assessment rubrics emphasized the importance of IC in the participation of a paired speaking test. Until recently, some studies attempted to investigate the design and validation of L2 tests to assess L2 IC, both in rubric development and test validation. For example, Dai (2022) developed an L2 IC test rubric for L2 Chinese learners and validated the whole test. Through Dai’s rubric, three dimensions related to social roles were considered, including non-verbal resources, interactional structure, and content knowledge. This study proved that non-verbal resources (e.g., eye gaze from interlocutors) impact significantly to the overall score in speaking tests. However, more research in relation to L2 IC assessments still needs to be expanded to the language testing area.

Under the joint term of listener responses, subcategories can be defined based on occurrence placement and functions in conversation. According to Sacks et al. (1974), this study outlines the basic mechanisms through which speakers in a conversation manage the allocation of turns, including how they recognize and create transitional opportunities for changing speakers. Thus, the place where a listener response occurs can be in a transitional or non-transitional place. Based on the functions of LRs in the conversation from a CA perspective in language assessment and educational contexts (Galaczi 2014; Lam 2021; Sert 2019), major subcategories of LRs include:

BACKCHANNELS are listener responses in a conversation that do not take the main conversational floor but signal the listener’s attention, comprehension, encouragement, or engagement with the speaker. This includes verbal cues such as “mm-hmm”, “yeah”, and “right”, and non-verbal cues like nodding, facial expressions, hand gestures, or other forms of visual feedback.

REACTIVE EXPRESSIONS are responses by a listener that directly reacts to what the speaker is saying, often conveying empathy, surprise, agreement, or other emotions. These expressions contain direct reaction tokens, such as exclamations like “Wow!” or “Really?”

REPETITIONS refer to the category where words, phrases, or larger linguistic units are echoed or restated within a co-constructed conversation by the other interlocutor.

RESUMPTIVE OPENERS are conversational strategies used to return to a previous topic or point of discussion after an interruption, digression, or after addressing a separate matter. They serve as cues that signal the speaker’s intent to circle back to an earlier thread of conversation, ensuring continuity and coherence in dialogue. For example, “Umm, so why you … ”, where “Umm” is considered as a resumptive opener for taking the floor while the other interlocutor is holding the floor because after “Umm” the other tokens indicating actual meanings also co-occur.

COLLABORATIVE FINISHES refer to a phenomenon in Conversation Analysis where one speaker completes a sentence or an utterance that another speaker has begun.

In addition to the above five subcategories, listener responses are categorized as transitional or non-transitional based on the position of listener responses that occurred. Transitional responses facilitate shifts in conversation, enabling changes in speaker or topic, often signaled by phrases like “Right, and also … ” or “That’s true, but … ”. Non-transitional responses, such as “uh-huh”, “I see”, or “okay”, simply acknowledge the speaker’s comments without altering the conversation’s direction. Transitional responses manage turn-taking and topic shifts, while non-transitional ones maintain listener engagement and attentiveness without interrupting the speaker’s flow. Both types are vital for regulating interaction dynamics in conversations (Clancy et al. 1996).

To our knowledge, no research so far has discussed the rubric design related to active listening ability in both L2 IC study and assessment regarding the deployment of LRs. In addition, the impact of adding ACTIVE LISTENING ABILITY on the rubric of L2 speaking assessment is still rarely investigated. Thus, this study aims to integrate the performance of active listening and the impact of the inclusion of active listening ability as one aspect of the rating rubric of the paired L2 speaking assessment.

3 The study

Until now, the majority of prior studies that concentrated on active listening ability conducted qualitative analyses using CA. However, only a limited number of studies employed both quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate this issue (Eiswirth 2020; Kosugi et al. 2021). Due to the qualitative nature of CA, making generalizations about active listening ability based on individual excerpts proves challenging. The quantitative method complements it with frequencies of LR tokens and paired speaking assessment scores, allowing for generalizability at a statistical level. This study aims to investigate the inclusion of the active listening aspect in the rating rubric of paired speaking assessment through both quantitative and qualitative analyses of scores and LRs to gain both in-depth analysis of the various deployment of LRs in business speaking assessment and statistical evidence for justifying the feasibility of inclusion of LRs in formal L2 English assessment. Thus, three research questions are proposed based on the research goal:

Does active listening ability impact the BEC speaking test score?

If so, how does the active listening ability influence the BEC speaking test score?

What factors differentiate the low-level and high-level performances of active listening in the BEC speaking test?

4 Methods

4.1 Participants

40 adult Chinese ESL learners of English (16 males and 24 females) participated in the current study. Their age ranged from 19 to 33 (M = 24.550, SD = 2.689). Participants were students or graduates of a large public University in Australia (4 bachelors, 30 masters and 6 PhDs). They came from a variety of major backgrounds, which included linguistics (n = 18), information technology (n = 8), science (n = 4), finance (n = 3), management (n = 3), education (n = 2), journalism (n = 1) and law (n = 1).

All participants spoke Mandarin Chinese as their first language and English as their second language. Since participants took three different English proficiency tests, we converted TOFEL iBT and PTE Academic scores into IELTS scores to estimate their average English proficiency based on authoritative conversion scales developed by Educational Testing Service (ETS) and 2020 Concordance Report - PTE Academic and IELTS Academic. After the score conversion, participants’ overall English proficiency scores ranged from 5.5 to 8.0 (M = 6.788, SD = 0.517). They were classified as higher intermediate to advanced L2 learners of English, equivalent to the B2 to C2 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR; Council of Europe 2020). Written informed consent for the video-recorded test participation was obtained from each participant beforehand. All participants received stationery gifts as compensation for their time of participation.

4.2 Study design

4.2.1 Instrument

The current study adopted the adaptive paired format of the B2 Business Vantage Speaking test of the Business English Certificate (BEC) as the research instrument to collect interactive production data (Figure 1). The adaptive BEC speaking task was the same for B1, B2, and C1 level learners. The BEC speaking test has been validated and widely used for the purpose of examining L2 English learners’ speaking proficiency in business contexts (Lee 2008) and enabled researchers to observe LRs that indicated their IC during the joint conversation (Sun 2014). We reduced the proportion of examiner’s intervention in the original test and increased the proportion of examinees’ participation to provide more opportunities of interaction during the test. Participants performed the adaptive speaking test in a pair. The length of the adaptive speaking test was 15 min, during which participants were asked to discuss business-related topics. The discussion topics were selected from the Business Certificates Handbook for Teachers, which have been used in the previous BEC speaking tests. The discussion topics in the current study were the same for each pair of participants.

An example of designed instruments for the discussion task (see Supplementary Material for full instruments).

The BEC speaking test consisted of three sections. In the first section, participants were given 2 min to briefly introduce themselves. The first section functioned as a warm-up activity, which aimed to familiarize participants within each pair. In the second section, participants were required to discuss a topic about “career change” and prepare a one-minute presentation to report their discussion within 2 min, during which they were also required to negotiate and decide the content and format of the presentation. The prompt in the second section covered a few keywords as directions and hints to facilitate the discussion, such as “further study or training” and “opportunities for future promotion”, in case participants had no idea about what to say due to little background knowledge about the given topic. The third section formed as a free discussion, which was the most important part of the task. In the third section, participants were asked to co-design an internship program for a small group of business students within 6 min. The test prompts were attached to Supplementary Material.

4.2.2 Raters and rating scales

Two Raters were hired in this study who were both experienced official BEC speaking test Raters. They were asked to give ratings based on a new rubric that was developed by the current study. Given that participants’ average English proficiency was equivalent to B2 level according to CEFR (Council of Europe 2020), the new rubric was developed by targeting the spoken features of L2 learners at this level. The traditional rubric for the BEC speaking test assessed examinees’ speaking performances in four major aspects, which were Grammar and Vocabulary, Discourse Management, Interactive Communication, and Active Listening (see Supplementary Material). Following the traditional rubric, the current study added Active Listening as the fifth aspect to the assessing rubric (see Supplementary Material).

The Rater training consisted of three stages, which are individual training, pilot scoring, and formal scoring. At the individual training stage, the researcher conducted a two-hour individual training session with each of the two Raters, during which videos of four pairs of participants with different L2 proficiency levels were shown. Besides, the developed rubric was introduced to the Raters, who provided constructive and professional feedback to the descriptors of the developed rubric. At the pilot scoring stage, an online one-hour training session was conducted to present the new rubric to the two Raters. Then, they did a practice in which they rated a sample pair of BEC test takers’ speaking performances in a video on YouTube. The two Raters also shared their ratings and discussed the reasons with the researchers. At the formal scoring stage, the two Raters were asked to watch the video recordings of participants’ performances, give ratings based on the five bands from 1 to 5, and provide detailed feedback for each participant’s strengths and weaknesses in each of the five aspects of the assessing rubric (see Supplementary Material).

4.3 Procedure

All participants were randomly divided into twenty dyads due to the unbalanced distribution between intermediate and advanced English proficiency levels. Each pair of participants took the speaking assessment in a quiet room at the campus of the University of Melbourne. At the beginning of the test, participants were asked to fill in a demographic questionnaire to collect basic information (gender, age, major, length of residence and English proficiency test scores). Then, both visual and verbal task instructions were shown by one of the researchers to participants, during which they were allowed to raise any questions about the test and ask the researchers for clarifications. Next, participants completed the three sections of the test. All participants were instructed to speak English during the test. The time span of the whole test was 15 min and the time for each section was controlled by researchers.

4.4 Data analysis

Data were analyzed by using a mixed method of qualitative and quantitative analyses. For the qualitative analysis, we first transcribed all participants’ data and annotated ten different types of LRs. Next, we conducted CA to capture the fine details of active listening features in the data. For the quantitative analysis, we calculated the frequency of subcategories of listener response in each conversation. We used Python (version 3.7.6) and R statistical platform (version 4.0.3) (R Core Team 2020). Since the test scores of the adaptive BEC speaking test are generated by the two Raters, we calculated Cohen’s Kappa to indicate the inter-rater reliability by using the sklearn.metri package in Python.

To answer Research Question 1, we ran simple and multiple linear regression models by using the lm function to analyze the relationship between the total amount of active listening tokens and the total BEC speaking test score and three aspects in the rating rubric related to pragmatics, including Discourse Management, Interactive Communication, and Active Listening. Multiple linear regression models were also used to analyze the relationship between the BEC speaking test score and the number of different types of active listening tokens. The normality assumption to run linear regression models was checked through both histograms and QQ plots. Graphs were created in R by using the ggplot2 package. To answer Research Questions 2 and 3, we analyzed Raters’ feedback and conducted a detailed CA of the conversations in the test. All data analysis codes can be accessed through Supplementary Material.

5 Results

5.1 Relationship between test score and active listening ability

We calculated the inter-rater agreement via Cohen’s Kappa for their scores of the overall speaking assessment for each participant and the score of each bond in the rating rubric. The result of Cohen’s Kappa was 0.83 for speaking rating results, which indicated a high inter-rater reliability. Table 1 demonstrates the descriptive statistics of the test scores in the five aspects of the newly developed rating rubric as well as the total score of the adaptive BEC paired speaking test given by the two Raters. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the active listening tokens appearing from the adaptive BEC paired speaking test.

Descriptive statistics of the scores in the adaptive BEC paired speaking test.

| Rater 1 | Rater 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Grammar and vocabulary | 3.738 | 0.707 | 3.250 | 1.276 |

| Discourse management | 3.988 | 0.738 | 3.200 | 1.091 |

| Pronunciation | 4.363 | 0.480 | 3.700 | 0.966 |

| Interactive communication | 4.013 | 0.712 | 3.425 | 1.375 |

| Active listening | 4.125 | 0.586 | 3.625 | 1.314 |

| Total | 20.225 | 2.532 | 17.200 | 5.170 |

Descriptive statistics of the active listening tokens appearing from the adaptive BEC paired speaking test.

| n | |

|---|---|

| Transitional backchannels | 21 |

| Transitional reactive expressions | 78 |

| Transitional collaborative finishes | 2 |

| Transitional repetitions | 17 |

| Transitional resumptive openers | 131 |

| Non-transitional backchannels | 151 |

| Non-transitional reactive expressions | 306 |

| Non-transitional collaborative finishes | 6 |

| Non-transitional repetitions | 28 |

| Non-transitional resumptive openers | 4 |

Firstly, the first simple linear regression model was run to investigate the relationship between the total amount of active listening tokens and the total score of the adaptive BEC paired speaking test. The results of the simple linear regression model 1 showed that the total amount of active listening tokens explains 40.8 % of the variance in the test performance after adjustment (β = 0.217, 95 % CI [0.134, 0.300], F(1, 38) = 27.880, p < 0.001), which indicated that active listening ability was a significant predictor of participants’ overall adaptive BEC paired speaking test performance (see Table 3 and Figure 2).

Results of the simple linear regression model 1.

| β | p | Adjusted R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 14.672 | *** | |

| Total amount of active listening tokens | 0.217 | *** | 0.408 |

-

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The relationship between total amount of active listening tokens and the total score of the adaptive BEC speaking test.

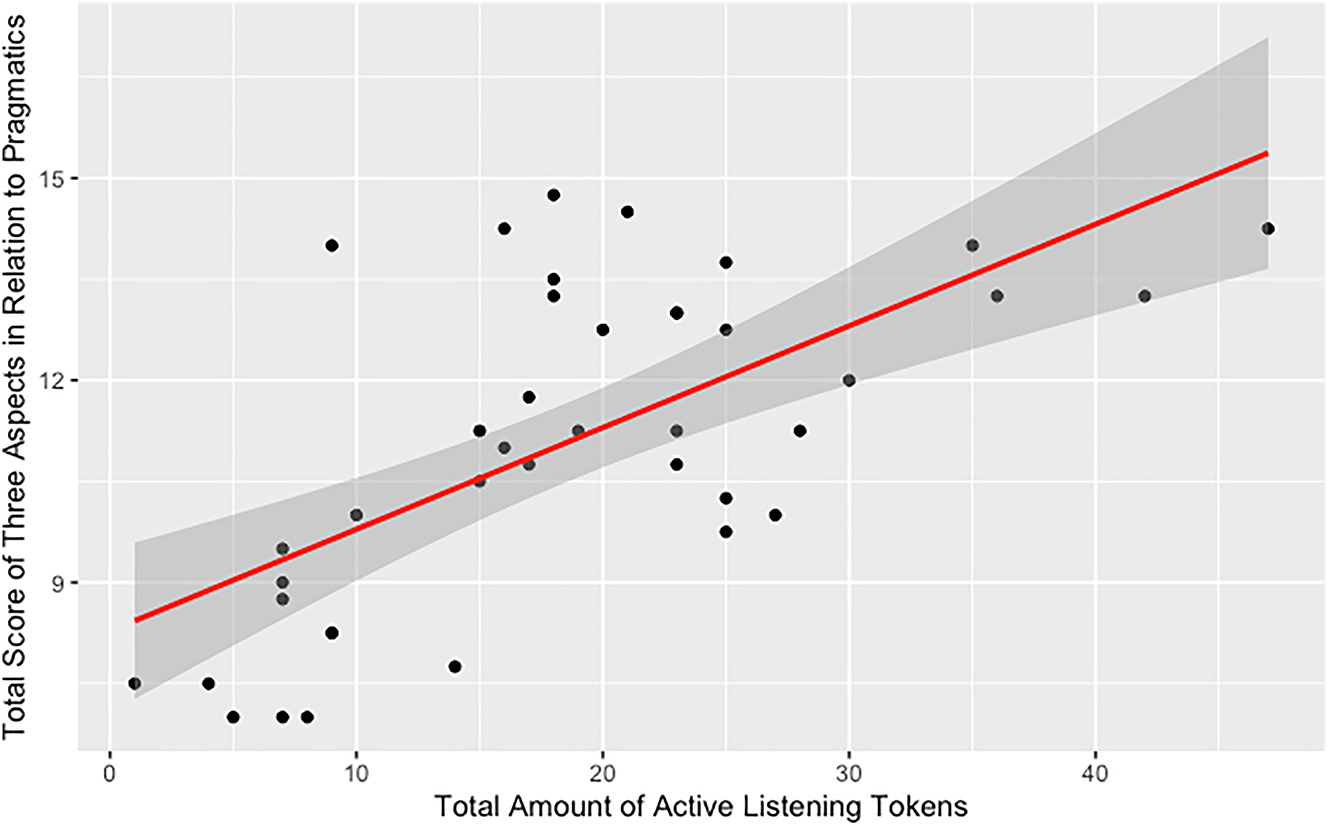

Then, the second simple linear regression model was run to investigate the relationship between the total amount of active listening tokens and the score of the three key aspects in the test rubric that are particularly relevant to pragmatics, including Discourse Management, Interactive Communication, and Active Listening. The results of the simple linear regression model 2 showed that the total amount of active listening tokens explains 41.6 % of the variance of the performance in these three aspects after adjustment (β = 0.151, 95 % CI [0.094, 0.207], F(1, 38) = 28.790, p < 0.001), which indicated that active listening ability was a significant predictor of participants’ performance in these three aspects of the adaptive BEC paired speaking test (see Table 4 and Figure 3).

Results of the simple linear regression model 2.

| β | p | Adjusted R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 8.280 | *** | |

| Total amount of active listening tokens | 0.151 | *** | 0.416 |

-

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The relationship between total amount of active listening tokens and the total score of the three pragmatic aspects.

Another multiple linear regression model was run to investigate the contribution of each type of active listening token to the total score of the adaptive BEC paired speaking test. The results showed that the non-transitional reactive expressions explain 38.5 % of the variance in the test performance after adjustment (β = 0.294, 95 % CI [0.024, 0.565], F(10, 29) = 3.442, p = 0.004), which indicated that the non-transitional reactive expressions were a significant predictor of participants’ overall BEC paired speaking test performance (see Table 5).

Results of the multiple linear regression model 1.

| β | p | Adjusted R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 14.012 | *** | |

| Transitional backchannels | 1.065 | ||

| Transitional reactive expressions | 0.053 | ||

| Transitional collaborative finishes | 0.053 | ||

| Transitional repetitions | −0.230 | ||

| Transitional resumptive openers | 0.352 | ||

| Non-transitional backchannels | 0.301 | ||

| Non-transitional reactive expressions | 0.294 | * | 0.385 |

| Non-transitional collaborative finishes | −0.905 | ||

| Non-transitional repetitions | −0.092 | ||

| Non-transitional resumptive openers | −2.092 |

-

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

5.2 Raters’ feedback on active listening rating and performance

Two Raters provided rating reports for each participant based on the performance in the current paired speaking assessment. The Raters’ feedback and rating scores reflected the main classification between the high-level (Band 4–5) and low-level (Band 1–2) active listening performance in several aspects.

5.2.1 General feedback on three sections

Raters offered detailed feedback on three sections of the speaking assessment. Raters focused on the usage of backchannels during the self-introduction part in Section 1 and the ability to perform interactive engagements and response tokens to open new turns in Section 2. For instance, a Rater’s comment below reflected the essence of reactive expressions in a discussion:

Uses short lexical words such as ‘Okay; Yeah’ to respond actively to the partner

In Section 3, since this section aimed at resolving a plan with a partner together in the discussion, the employment of non-lexical vocalization backchannels “umm”, “oh”, and “ah” was considered as an ability to express confirmation or involvement when not producing any substantial content. In addition, short lexical words that function as reactive expressions indicate that various attitudes also matter. For example, using “okay” to express agreement, “yeah” to indicate questioning, and “wow” to imply surprise. What stands out as the prominent result was the Rater’s focus on overall LRs. Both Raters considered providing support and backup for the partner in such paired speaking assessment as an important ability in discussions.

5.2.2 Features reflecting active listening performance in paired speaking ratings

Statistical results showed reactive expressions had the most prominent relationship with both the overall speaking assessment score and the score of the active listening aspect. reactive expressions included different tokens demonstrating various functions based on the feedback of two Raters. For example, in Excerpt 1 presented below, Speaker A and B are discussing a possible solution in working out how to offer a two-week long course for business major students, the selected part demonstrates where speakers giving actual suggestion on how to design this two week’s course.

B firstly uses a head nod to confirm this information followed by an utterance “and we jus- end up” (Line 9) to deepen their plan of this mini-presentation. Without any hesitation, A closely takes the floor by using a reactive expression “yeah yeah yeah” (Line 10) to indicate A’s strong agreement with B’s proposed direction. Then after B reconfirms A’s idea, A produces an “okay” (Line 17) to show A’s confirmation of the current direction. Although A and B don’t have frequent verbal LRs, they provide reactive expressions at two critical places during the whole conversation. As Raters noticed, this kind of reactive expression demonstrated the ability of mutual understanding in participating in the conversation.

Excerpt 1

1. A: I think may:be we can (.) choose both

2. th- some poin-

3. (eye gaze to B)

4. and (.)

5. B: (hand gesture with right hand raised up)

6. A: and do the presentation half a minute

7. (eye gaze to B)

8. B: (head nod)

9. and we jus- end up:

10. A: yeah yeah yeah ↑

11. okay and::

12. B: I think the

13. the hints are

14. B: (hand gesture)

15. A: is are [good] choices

16. B: [e:::n]

17. A: okay:

18. B: so which one you would like to disuss- more about the

19. future study or training

20. A: (eye gaze to B)

21. A: en ↓

Besides the reactive expressions to show various functions, non-verbal expressions also matter in Raters’ feedback. In Excerpt 1, A and B have a high-level use of non-verbal expressions in their discussions. When A looks at B, B could use both verbal and non-verbal expressions to provide information to build this conversation in a smooth way. When A is talking about what kind of aspects should be discussed in their mini-presentation, B raised the right hand a bit to show the agreement to speaker A’s content in Line 5. Then A shifts to the main topic, the time limitation for this mini-presentation, and moves the eye gazes to B to wait for B’s responses (Line 7). As the discussion runs, B initiates the opinion and invites A to contribute to the idea “so which one you would like to discuss-” (Line 18). At this moment, A realizes B’s invitation to join the talk, A moves eyes and gazes at B’s face followed by a backchannel token “en” (Line 21), indicating A’s active engagement in the whole talk.

In addition, resumptive openers demonstrated the ability to construct new content based on the ongoing talk. Raters provided eight notes for Band 4–5 participants based on resumptive openers. Where in Excerpt 2, A and B are sharing ideas on career choice as business majors. In this task, two speakers A and B are discussing about how they consider about possible career change. When Speaker A considered location and life quality as more important factors, Speaker B used various active listener responses to show the agreement with Speaker A of this statement on career change. As Excerpt 2 indicates during A’s turn “and for me maybe I will choose the other about talk more …” (Line 7–8), where indicated the “other (factors)” may also impact the career choice, for instance, life, educational experience, resources. However, Speaker B demonstrated agreement with Speaker A via verbal and non-verbal active listener responses.

B employs a resumptive opener “umm” and starts to talk about “life or locati-” as further development of the current content. After the resumptive opener, B could add more opinions based on A’s delivery. The employment of the resumptive opener demonstrated not only the understanding of the current talk but also the ability to construct and build new and connected content in the conversation.

Excerpt 2

1. A: I cannot improve in the job

2. A: so I maybe I will change a career

3. B: (right hand moved a bit with thumbs up)

4. A: (head nod)

5. B: uh huh [Backchannel]

6. B: yeah yeah [Reactive Expressions]

7. A: and for me maybe I will choose the other

8. about talk more about like

9. B: umm:: [life or] [Resumptive Opener]

10. A: [en:: en]

11. B: the loca- [the locations ]

12. A: [yeah yeah yeah]

13. B: and cultures I think

14. A: (head nod)

15. B: something [yeah] so so maybe

16. A: [yes] [Reactive Expressions]

17. B: (head nod)

18. A: yes that’s fine=

19. B: yeah= [Collaborative Finishes]

Backchannels also impact the Raters’ judgment on the overall performance of the active listening aspect. Backchannels are often considered as the signal to maintain an active engagement in social actions. As Excerpt 3 presented below, both interlocutors presented thoughts on how to plan future careers. A acts as the speaker in this discussion task, while B does not maintain the quiet listener role. In contrast, B employs several backchannels to indicate B’s attention and engagement in the whole conversation when A keeps talking.

Excerpt 3

1. A: and the future study or training

2. B: uh huh [Backchannel]

3. A: yeah and

4. A: I will make make something like this

5. A: and ah

6. B: yeah

7. A: I think

8. A: let me think

9. B: (hhhhh) [Backchannel]

10. A: future study and ah

11. A: because in (.) I think in

12. A: when we graduate and

13. B: uh [Backchannel]

14. A: doing my job

15. B: (hand gesture)

16. B: uh huh [Backchannel]

5.2.3 Different active listening performance in paired speaking assessment task

This section concludes Raters’ feedback on Band scores and the performance of different aspects in this paired speaking assessment. With the distinction between the performance of high-level and what is low-level performance in both verbal and non-verbal language, the different performances would be presented.

To be noted, for high-level Band 4–5 performance, collaborative finishes have more frequent occurrence, with traditional collaborative finishes of 2 times (all production in this dataset), and 5 out of 6 of non-transitional collaborative finishes. In contrast, score 1–3 test takers only have 1 non-transitional collaborative finishes.

More specifically, for high-level Band 4–5 performance, Raters believe that the reactive tokens should occur in relevant places to show participants’ attitudes based on the current context. The backchannels should be relatively active in general when not holding the floor, the participant should let the other interlocutor know the involvement and engagement through a verbal or a non-verbal backchannel, for non-verbal responses here means the head nod, eye gaze, hand gestures or smile and laugh. In addition, what the learner participant does in the following turn also matters and contributes to their performance in the active listening performance overall.

For example, for a Band 5 participant, the Rater feedback was as follows:

Whilst A is fairly quiet, he consistently shows his interlocutor that he is listening to and understanding him. Regularly bases turn on his interlocutor’s prior turns, for example, asking follow-up questions or making comments about the content of the prior turn.

Excerpt 4 demonstrates the performance of this participant in the Rater’s feedback. In Excerpt 4, A and B are talking based on the instructions of Section 3, in which they are designing a short-term working experience training program for students. Speaker A acts as the main dominator in this part, and B serves the role of a listener. Although A merely holds the floor or produces content willingly or in a rather active way in the first part of the discussion, when B is delivering his speech, A uses a backchannel token “uh huh” in Line 8 to respond to B’s opinion of internship for university students. In Line 14, after a resumptive opener “uh” in Line 13, A starts to talk about what he thinks an internship experience is like and his expectations for such a program. Then, in Line 18 and Line 22, A employs two resumptive openers “yeah yeah” and “yeah” to first confirm A’s idea and then build his talk based on A’s previous content. To be noted, B employed “yeah” in Line 27 as a collaborative finishes when A is about to end the discussion where indicated that both speaker hold the awareness to close the conversation in proper manner.

Excerpt 4

1. B: =but I think for business students maybe like uh

2. what kind of work experience I think it’s more s- uh

3. lead to entry life or experience like uh:=

4. =cause I was when I was enter in the major of finance

5. it was a business major and

6. when I was enter my just uh (.) my mentor was like assign me

7. (.) was like doing something like really [entry] level things

8. A: [uh huh]

[Backchannel]

9. B: exc- excel stuff like uh

10. or just think assigning the daily uh (.) texts for

11. so umm (.)

12. I don’t know do you have any internship experience like uh(.)

13. A: uh:: [Resumptive Opener]

14. I don’t quite have internship but I will do a causal job

15. in a data science

16. [enterpr-::]

17. B: [okay cool]

18. A: yeah yeah. [Resumptive Opener]

19. (.)but it’s pretty like uh

20. a basic and entry level

21. B: yeah early the beginning stage

22. A: yeah= [Resumptive Opener]

23. but I think for the work experience

24. it’s kind of different from the internship

25. So(.)maybe I think the students will perusing like

26. kind of the real hea-

27. B: [yeah]= [Collaborative Finishes]

On the other hand, for low-level active listening performance, like Band 1–2 participants, they produce relatively rare reactive expressions, rather few backchannels and use repetitions from the previous speech to indicate reconfirmation or surprise. Furthermore, no collaborative finishes were found in their discussion data. For instance, the Rater provided feedback for performance at Band 1:

Does make an attempt to provide acknowledgement tokens but these are rare. Stays very silent while the interlocutor is talking, particularly in part 3. This may have been because he couldn’t understand some of what his interlocutor (also low proficiency) was saying.

Excerpt 5

1. A: It’s really [dependen]=

2. B: [ umm::] [Backchannel]

3. A: = but but then if you see you get no promotions

4. A: but but then if you see yo-

5. A: (.)you get no promotions uh:=

6. A: (eye gaze to B)

7. A: (.)ah(.) if you want doing software development

8. A: it was a business major and

9. (0.8)

10. A: okay(.) [Reactive Expressions]

11. A: when I like ah (.) was a leader for team development

12. A: me (.) was umm::

13. B: ah:: [Backchannel]

As shown in Excerpt 5 above, this is a discussion between Band 1 and Band 4 participants. In their discussion, they are instructed to decide what factors may lead to a career or job change. Speaker A, as the main content contributor in this part, tries to yield the floor to Speaker B by an eye gaze in Line 6, and a long pause in Line 9. However, Speaker B remains salient, then Speaker A continues her talk in Line 9 followed by an “okay” (Line 8). Speaker B attempts to respond in Line 2 with a backchannel “umm”, while Speaker B loses engagement in the later discussion. As the rater pointed out, the more active listener can provide tokens to indicate agreement or participation when the other interlocutor is holding the floor while a low-level active listener could merely produce tokens or use non-verbal reactions to show this participation during the co-construct of a conversation. From Excerpt 5, when Speaker A and Speaker B are talking about the promotion possibilities in work, Speaker B does not understand Speaker A’s content which leads to the rare occurrence of listener responses, even when Speaker A attempts to give the floor to Speaker B, where Speaker B fails to take the floor.

To sum up, from the raters’ feedback for Band 1 and Band 5, the clear division demonstrates that (a) the deployment of subcategories of listener responses and (b) the function of response tokens both contribute to the determination of high/low-level of active listening in paired speaking assessment scoring.

6 Discussion

The current study used quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate the inclusion of the active listening aspect in the rating rubric of paired speaking assessment. Firstly, quantitative results showed a significant linear relationship between the total amount of active listening tokens and both the total score of the BEC speaking test score and the sum score of the three aspects relevant to pragmatics ability in the rating rubric, which indicated that the active listening ability had an impact on both the overall BEC speaking performance and also the overall performance in the three aspects. Secondly, among the ten types of active listening tokens, it was found that only the type of non-transitional reactive expressions contributed to learners’ overall BEC speaking performance. Thirdly, qualitative results showed the ability to produce active listening subcategories (e.g., collaborative finishes, resumptive openers, and reactive expressions) was related to overall active listening performance scores according to Raters’ rating reports based on the new proposed rating rubric.

6.1 The relationship between active listening and BEC speaking performance

The findings showed that with the raising of the total number of active listening tokens could indicate active listening ability improves. The findings implied that active listening ability had a close relationship with speaking performance since it was a tool to present the overall ability to participate and engage in the discussion (Ross 2018). It indicated that active listening ability is an important predictor of speaking performance, which also aligned with the findings of Lam (2021). The active listening tokens demonstrated the ability not only to comprehend the utterance of the other interlocutor but also to contribute to the discussion and collaborate on the tasks (Ducasse 2010). This finding demonstrates the feasibility of quantifying active listening ability via calculating the tokens of subcategories of listener responses in conversation in future language assessments that emphasize communicative ability or interactional competence. Therefore, active listening ability is relevant and consequential to the speaking performance in assessments, which provides strong evidence to be added to the speaking assessment rubric. However, from the raters’ feedback, the emphasis among subcategories of LRs indicated the deployment of different types of LRs performs varied across different IC levels. For example, reactive expressions and resumptive openers help speakers to navigate conversational transitions smoothly, maintaining the relevance and coherence of the dialogue.

The result that the type of non-transitional reactive expressions contributed to L2 learners’ overall BEC speaking performance the most was also in alignment with the observations in Sert (2019) where the results indicated the occurrence of responses tokens at traditional relevance place showed the ability of stance in the L2 talk. The non-transitional reactive expressions demonstrated learners’ ability not only to pay attention to the utterance expressed by the other interlocutor but also to show their acknowledgement and agreement with the content in the other interlocutor’s utterance. Therefore, the non-transitional reactive expression was more salient than other token types of active listening ability in the paired speaking test.

6.2 The impact of active listening ability in paired speaking assessment rating

Both Raters considered the active listening aspect as an important part of paired speaking tasks assessment. As experienced BEC Raters, they found that during the rating of employing this new rubric, the active listening aspect was closely connected with the Interactive Communication aspect and Discourse Management aspect, which shows consistent results with the previous studies (Carlén 2020; Davey 2022; Eiswirth 2020; Galaczi 2014). Some critical LRs during the discussion in three sections of the test offer a lot of support to the speakers in the talk and constantly demonstrated engagement in the ongoing conversation. This finding was consistent with previous studies in L2 LRs. For instance, Carlén (2020) revealed that with improved L2 proficiency, the L2 English LR would improve in both frequency and functional distribution during classroom actions.

However, the active listening ability could be influenced by language proficiency to a certain degree as reported by two Raters. Some equal proficiency participants were able to demonstrate their cooperative abilities with at least two or three collaborative completions. This has been identified in relative CA studies in turn construction, which targeted the function of collaborative completions. For example, King (2019: 7) identified the importance of ‘finishing each other’s sentence’ under the CA conventions. Later, Davey (2022) noted the essential function of collaborative completions as one tool in co-joined participation in L2 conversations. Based on the current findings of the quantitative analysis, the total occurrence of collaborative finishes is the highest in Band 4–5 instead of Band 1–3, collaborative finishes indeed require a higher ability in IC to deploy this resource compared to other types of LRs and hold a prominent impact on the score among two raters’ feedback.

Notably, for participants who were matched with unequal proficiency speakers, some opportunities to display their abilities were severely hamstrung by their partner’s low proficiency or willingness to talk. This leads to the practicality issue with the inclusion of this aspect in future language assessment rubric design. Since proficiency has not been validated in this rubric, it needs more consideration to match language proficiency between participants when considering active listening in the score rating.

6.3 Factors differentiating high-level and low-level performance in active listening

For high-level performance participants, rather than focusing on the frequency of the LRs in the paired discussion tasks, Raters emphasized more when a response should have occurred and how the responses contribute to the goal of the task. Specifically, the most frequent comments given to Band 4–5 participants were the ability to maintain verbal and non-verbal backchannels and being interactive to react to the content of the previous speaker. This finding cohorts with the previous research in active listening among L2 speakers. For example, Author(s) (xxxx) examined the LRs among different stay abroad length L2 learners and concluded that longer stay abroad L2 learners could produce more active LRs in role-play and storytelling tasks and showed a more active performance in backchannels productions.

Another prominent finding was the employment of resumptive openers. This proves the ability to react to what the other interlocutor says, getting involved in the partner in discussion, and introducing new ideas based on current content (Schegloff 1979). The backchannels used by the high-performance L2 speakers often demonstrate understanding or confirmation of some uncertain information during the discussion without unappreciated interruptions (Eiswirth 2020; Ross 2018). In contrast, the low-level performance participants tend to show “passive engagement” in the discussion task with a rare contribution to producing feedback when the primary speaker is holding the floor (Davey 2022; Lam 2021).

The usage of reactive tokens, such as “yeah”, “well”, “good”, and “really”, occurs at a suitable time in the discussion, showing attitudes or further deeper topics and defining the active listening ability between low and high level from the findings in this study. The ability to link the contributions from another interlocutor into their own talk with the assistance of LR is another common feature in the employment of reactive tokens (Drummond and Hopper 1993b). In L2 language interactive speaking assessment, reactive expression tokens serve as an encouragement or assistance to partners in the task to express their ideas when facing language expression barriers (Ducasse 2010).

In addition, the overall construction of LRs produced by participants in paired discussion varies in functions, which also differentiates the level of performance. Due to the barriers to understanding previous content, some LRs often functioned as questioning or reconfirmation of previous content delivered by the current speaker (Lam 2021), this indicates a low-level IC. In contrast, LRs could serve as agreement, acknowledgment, and continuer in social actions (Jefferson 1993), these functions jointly build the conversation and make the transition between speakers and listeners.

However, most low-level active listeners mostly just answered the questions produced by the examiner and only addressed more general questions in response to their partner’s prompting. They hardly responded or provided feedback when not holding the speaker’s role in communication, which makes it difficult for speakers to yield the turn to low-level active listeners. The lack of employing a rich variety of LRs caused the difficulties of topic management among turns (Sacks et al. 1974) which leads to the disability to continue the conversation when one topic ends.

For practical implication from this study, we justify the feasibility of conducting assessment in the form of interactional competence and emphasis on active listening for specific contexts which requires a heavy load on active listening ability (e.g., business communication, mental counselling, and academic conversations).

6.4 Limitations of the study

As the first study to include active listening as a distinct rating criterion in a paired speaking test, there are still a few potential limitations in this study. Firstly, the feasibility and practicality could be a problem when replicating this study. Two Raters recruited in this study were experienced in rating BEC and paired speaking assessment. If this rubric was given to a beginner Rater with little rating experience, they might find the rubric a bit harder to use without enough training and examples being provided. A standardization session that shows a bunch of videos of performances for criteria should be designed for validation of this rubric. This could get the Raters to try to rate the performances first, and then reveal what the appropriate ratings are and explain the reasons with reference to the band descriptors. For Rater training, the lack of standardization may lead to different interpretations of this new rubric, which might cause personal bias in the rating process.

Also, some mismatches in the bands representing the three criteria in the active listening aspect may exist due to the lack of a rubric validation procedure. For the “traditional” criteria (e.g., Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation), these three represent a pretty solid level, which is equal to the IELTS rubric classification for these three aspects. However, the descriptor for active listening lacks enough comparison, which means that there may exist less of a range between 1 and 5 for active listening.

6.5 Future research directions

More studies are needed in the research of active listening, either in the language assessment field or L2 IC. For future studies, two directions could be considered. Firstly, according to the findings in this study, language proficiency may impact the communication between pairs in speaking tests, thus language proficiency needs to be matched according to the speaking performance instead of the overall score of language proficiency tests. In addition, a validation study for this newly developed rubric is called for future focus on L2 IC assessment. For designing such a rubric, future studies are encouraged to use the designed rubric as an instrument to test L2 IC in languages other than English to see whether the findings are consistent in terms of rater agreement and rating interpretations. However, due to the time and scope of the current study, the validation process is expected in a future research agenda. In addition, based on the dyad format, more detailed behavior analysis can be conducted to distinguish the impact of individual influence for each dyad instead of across-group comparison.

7 Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first study that has investigated the impact of the inclusion of active listening as one aspect of the paired speaking assessment rubric, which fills an important research gap in L2 IC assessment. The performance in low-level and high-level active listening under a language assessment setting reflects the ability to understand and engage in social interactions. Additionally, the rating and feedback imply the importance of including active listening as one aspect of the assessment rubric in the interactive paired speaking test. The novel finding of this study is that the inclusion of the active listening aspect holds a prominent impact on the overall score statistically. Another novel finding is that Raters value the inclusion of active listening and support that active listening could reflect the IC ability in an English-speaking assessment in business contexts, or other language assessments targeting a specific expert domain. Apart from the significant findings related to L2 IC assessment, this research also presents a direct comparison between high-level and low-level active listening ability from a micro CA perspective with detailed evidence. Finally, this study identifies the importance and value of considering active listening and LRs in future research on L2 language assessments.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Prof. Carsten Roever for his insightful feedback, guidance, and support of this project. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We would like to thank all the participants for their participation in our project.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Research ethics: This study has been approved by univeristy’s ethics approval under the review number of: Human Ethics LNR as 2022-24988-32929-3.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Bavelas, Janet Beavin, Linda Coates & Trudy Johnson. 2002. Listener responses as a collaborative process: The role of gaze. Journal of Communication 52(3). 566–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02562.x.Search in Google Scholar

Beach, Wayne A. 1993. Transitional regularities for ‘casual’ “Okay” usages. Journal of Pragmatics 19(4). 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(93)90092-4.Search in Google Scholar

Bodie, Graham D. 2012. Listening as positive communication. In Thomas Socha & Margaret Pitts (eds.), The positive side of interpersonal communication, 109–125. New York: Perter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Carlén, Caroline. 2020. Listener support strategies: A study of Swedish high school students’ use of response tokens in English. Stockholm: Stockholm University.Search in Google Scholar

Clancy, Patricia M., Sandra A. Thompson, Ryoko Suzuki & Hongyin Tao. 1996. The conversational use of reactive tokens in English, Japanese, and Mandarin. Journal of Pragmatics 26(3). 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(95)00036-4.Search in Google Scholar

Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment: Companion volume with new descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Dai, David Wei. 2022. Design and validation of an L2-Chinese interactional competence test. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.Search in Google Scholar

Davey, Michael. 2022. Exploring the organisation of second language conversation: The roles of grammar, social identity, knowledge and ‘conjoined participation’ in interactional competence. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.Search in Google Scholar

Drummond, Kent & Robert Hopper. 1993a. Acknowledgment tokens in series. Communication Reports 6(1). 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934219309367561.Search in Google Scholar

Drummond, Kent & Robert Hopper. 1993b. Some uses of yeah. Research on Language & Social Interaction 26(2). 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi2602_6.Search in Google Scholar

Ducasse, Ana Maria. 2010. Interaction in paired oral proficiency assessment in Spanish: Rater and candidate input into evidence based scale development and construct definition. New York: Peter Lang.10.3726/978-3-653-05393-7Search in Google Scholar

Eiswirth, Mirjam Elisabeth. 2020. Increasing interactional accountability in the quantitative analysis of sociolinguistic variation. Journal of Pragmatics 170. 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.08.018.Search in Google Scholar

Galaczi, Evelina D. 2014. Interactional competence across proficiency levels: How do learners manage interaction in paired speaking tests? Applied Linguistics 35(5). 553–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt017.Search in Google Scholar

Galaczi, Evelina & Lynda Taylor. 2018. Interactional competence: Conceptualisations, operationalisations, and outstanding questions. Language Assessment Quarterly 15(3). 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2018.1453816.Search in Google Scholar

Goodwin, Charles. 1986. Audience diversity, participation and interpretation. Text 6(3). 283–316. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1986.6.3.283.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Joan Kelly, John Hellermann & Simona Pekarek Doehler (eds.). 2011. L2 interactional competence and development. Bristol & Buffalo: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847694072Search in Google Scholar

Jefferson, Gail. 1983. Two explorations of the organization of overlapping talk in conversation: Notes on some orderlinesses of overlap onset. Tilburg Papers in Language and Literature 28. 1–28.Search in Google Scholar

Jefferson, Gail. 1984. Notes on a systematic deployment of the acknowledgement tokens “Yeah”; and “Mm Hm”. Paper in Linguistics 17(2). 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351818409389201.Search in Google Scholar

Jefferson, Gail. 1993. Caveat speaker: Preliminary notes on recipient topic-shift implicature. Research on Language & Social Interaction 26(1). 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi2601_1.Search in Google Scholar

Kawamichi, Hiroaki, Kazufumi Yoshihara, Akihiro T. Sasaki, Sho K. Sugawara, Hiroki C. Tanabe, Ryoji Shinohara, Yuka Sugisawa, Kentaro Tokutake, Yukiko Mochizuki, Tokie Anme & Norihiro Sadato. 2015. Perceiving active listening activates the reward system and improves the impression of relevant experiences. Social Neuroscience 10(1). 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2014.9.Search in Google Scholar

Khanna, Pooja. 2020. Techniques and strategies to develop active listening skills: The armour for effective communication across business organizations. The Achievers Journal 6(3). 50–60.Search in Google Scholar

King, Allie Hope. 2019. Collaborative completions in everyday interaction: A literature review. Studies in Applied Linguistics and TESOL 18(2). 1–14. https://doi.org/10.7916/SALT.V18I2.1190.Search in Google Scholar

Kosugi, Shunsuke, Koichiro Ito, Masaki Murata, Tomohiro Ohno & Shigeki Matsubara. 2021. Identification of important utterances in narrative speech using attentive listening responses. In 2021 16th International Joint Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language Processing (iSAI-NLP), 1–6. Ayutthaya, Thailand, 21-23 December.10.1109/iSAI-NLP54397.2021.9678154Search in Google Scholar

Lam, Daniel M. K. 2021. Don’t turn a deaf ear: A case for assessing interactive listening. Applied Linguistics 42(4). 740–764. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amaa064.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Hyeong-Jong. 2008. Issues in testing business English: The revision of the Cambridge Business English certificates. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 30(1). 98–100. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263108080066.Search in Google Scholar

Mondada, Lorenza. 2011. Understanding as an embodied, situated and sequential achievement in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 43(2). 542–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.019.Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, Susan E., Aurora Occa, JoNell Potter, Ashton Mouton & Megan E. Peter. 2017. “You need to be a good listener”: Recruiters’ use of relational communication behaviors to enhance clinical trial and research study accrual. Journal of Health Communication 22(2). 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1256356.Search in Google Scholar

Pillet-Shore, Danielle. 2003. Doing “okay”: On the multiple metrics of an assessment. Research on Language & Social Interaction 36(3). 285–319. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3603_03.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Roever, Carsten & Naoki Ikeda. 2022. What scores from monologic speaking tests can(not) tell us about interactional competence. Language Testing 39(1). 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/02655322211003332.Search in Google Scholar

Roever, Carsten & Gabriele Kasper. 2018. Speaking in turns and sequences: Interactional competence as a target construct in testing speaking. Language Testing 35(3). 331–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532218758128.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, Steven. 2018. Listener response as a facet of interactional competence. Language Testing 35(3). 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532218758125.Search in Google Scholar

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff & Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50(4). 696–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243.Search in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1979. Identification and recognition in telephone conversation openings. In George Psathas (ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology, 23–78. New York: Irvington.Search in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1997. Practices and actions: Boundary cases of other‐initiated repair. Discourse Processes 23(3). 499–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539709545001.Search in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2009. One perspective on conversation analysis: Comparative perspectives. In Jack Sidnell (ed.), Conversation analysis, 357–406. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511635670.013Search in Google Scholar

Sert, Olcay. 2019. The interplay between collaborative turn sequences and active listenership: Implications for the development of L2 interactional competence. In M. Rafael Salaberry & Silvia Kunitz (eds.), Teaching and testing L2 interactional competence: Bridging theory and practice, 142–166. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315177021-6Search in Google Scholar

Shively, Rachel L. 2015. Developing interactional competence during study abroad: Listener responses in L2 Spanish. System 48. 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.09.007.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, Sara W., Hiromi Pat Noda, Steven Andrews & Andreas H. Jucker. 2005. Setting the stage: How speakers prepare listeners for the introduction of referents in dialogues and monologues. Journal of Pragmatics 37(11). 1865–1895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2005.02.016.Search in Google Scholar

Sun, Dongyun. 2014. From communicative competence to interactional competence: A new outlook to the teaching of spoken English. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 5(5). 1062–1070. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.5.5.1062-1070.Search in Google Scholar

Tao, Hongyin & Sandra A. Thompson. 1991. English backchannels in Mandarin conversations: A case study of superstratum pragmatic ‘interference. Journal of Pragmatics 16(3). 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(91)90093-D.Search in Google Scholar

Weger, Harry, Gina Castle Bell, Elizabeth M. Minei & Melissa C. Robinson. 2014. The relative effectiveness of active listening in initial interactions. International Journal of Listening 28(1). 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2013.813234.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, Jun. 2014. Displaying status of recipiency through reactive tokens in Mandarin task-oriented interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 74. 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.08.008.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2023-0258).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Learning academic vocabulary through reading online news

- A Q methodological study into pre-service Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) teachers’ mindsets about teaching competencies

- Assessing written production in L2 Mandarin Chinese: fluency and accuracy

- Machine translation as a form of feedback on L2 writing

- Acquisition of collocations under different glossing modalities and the mediating role of learners’ perceptual learning style

- Unpacking changing emotions in multiple contexts: idiodynamic study of college students’ academic emotions

- Exploring L2 learners’ processing of unknown words during subtitled viewing through self-reports

- Model text as corrective feedback in L2 writing: the role of working memory and vocabulary size

- Exploring learner-related variables in child collaborative writing: interaction mindset, willingness to communicate and proficiency

- Contributions of significant others to second language teacher well-being: a self-determination theory perspective

- The stone left unturned: boredom among young EFL learners

- The impact of out-of-school L2 input and interaction on adolescent classroom immersion and community-L2 learners’ L2 vocabulary: opportunities for interaction are key

- Promoting interaction and lowering speaking anxiety in an EMI course: a group dynamic assessment approach

- Relationship between learner creativity, task planning, and speaking performance in L2 narrative tasks

- Influencing factors of L2 writers’ engagement in an assessment as learning-focused context

- The cognitive-emotional dialectics in second language development: speech and co-speech gestures of Chinese learners of English

- Impact of task type and task complexity on negotiation of meaning in young learners of Chinese as a second language

- Effects of working memory and task type on syntactic complexity in EFL learners’ writing

- Assessing effects of source text complexity on L2 learners’ interpreting performance: a dependency-based approach

- Incidental learning of collocations through reading an academic text

- Listenership always matters: active listening ability in L2 business English paired speaking tasks

- Enhancing the processing advantage: two psycholinguistic investigations of formulaic expressions in Chinese as a second language

- The effect of form presentation mode and language learning aptitude on the learning burden and decay of L2 vocabulary knowledge

- Examining the impact of foreign language anxiety and language contact on oral proficiency: a study of Chinese as a second language learners

- The dynamics of changes in linguistic complexity and writing scores in timed argumentative writing among beginning-level EFL learners

- Perception of English semivowels by Japanese-speaking learners of English

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Development and validation of Questionnaire for Self-regulated Learning Writing Strategies (QSRLWS) for EFL learners

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Learning academic vocabulary through reading online news

- A Q methodological study into pre-service Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) teachers’ mindsets about teaching competencies

- Assessing written production in L2 Mandarin Chinese: fluency and accuracy

- Machine translation as a form of feedback on L2 writing

- Acquisition of collocations under different glossing modalities and the mediating role of learners’ perceptual learning style

- Unpacking changing emotions in multiple contexts: idiodynamic study of college students’ academic emotions

- Exploring L2 learners’ processing of unknown words during subtitled viewing through self-reports

- Model text as corrective feedback in L2 writing: the role of working memory and vocabulary size

- Exploring learner-related variables in child collaborative writing: interaction mindset, willingness to communicate and proficiency

- Contributions of significant others to second language teacher well-being: a self-determination theory perspective

- The stone left unturned: boredom among young EFL learners

- The impact of out-of-school L2 input and interaction on adolescent classroom immersion and community-L2 learners’ L2 vocabulary: opportunities for interaction are key

- Promoting interaction and lowering speaking anxiety in an EMI course: a group dynamic assessment approach

- Relationship between learner creativity, task planning, and speaking performance in L2 narrative tasks

- Influencing factors of L2 writers’ engagement in an assessment as learning-focused context

- The cognitive-emotional dialectics in second language development: speech and co-speech gestures of Chinese learners of English

- Impact of task type and task complexity on negotiation of meaning in young learners of Chinese as a second language

- Effects of working memory and task type on syntactic complexity in EFL learners’ writing

- Assessing effects of source text complexity on L2 learners’ interpreting performance: a dependency-based approach

- Incidental learning of collocations through reading an academic text

- Listenership always matters: active listening ability in L2 business English paired speaking tasks

- Enhancing the processing advantage: two psycholinguistic investigations of formulaic expressions in Chinese as a second language

- The effect of form presentation mode and language learning aptitude on the learning burden and decay of L2 vocabulary knowledge

- Examining the impact of foreign language anxiety and language contact on oral proficiency: a study of Chinese as a second language learners

- The dynamics of changes in linguistic complexity and writing scores in timed argumentative writing among beginning-level EFL learners

- Perception of English semivowels by Japanese-speaking learners of English

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Development and validation of Questionnaire for Self-regulated Learning Writing Strategies (QSRLWS) for EFL learners