Abstract

Late-life language learning has gained considerable attention in recent years. Strikingly, additional language (AL) proficiency development is underinvestigated, despite it potentially being one of the main drivers for older adults to learn an AL. Our study investigates whether Dutch older adults learning English for three months significantly improve their AL skills, and if explicit or implicit language instruction is more beneficial. Sixteen learners participated in online weekly group lessons, five days of 60-min homework, and pre-post-retention tests. Half were randomly assigned to the mostly explicit condition and half to the mostly implicit condition. Data includes language proficiency measures and 201 dense-data spoken homework samples. Results show improvements in several areas for both conditions. For structural errors in homework, we found implicitly taught participants to make significantly more mistakes. Our exploratory data show that older adults significantly develop AL proficiency after a short language training, and, as we only found differences between conditions on one construct, that teaching pedagogies do not play a substantial role.

1 Introduction

With global life expectancy increasing, late-life language learning, or LLLL for short, has gained much attention in recent years. Although most studies have defined LLLL’s starting age to be 65+, it is hard to reduce ageing to a number due to it being a highly individual experience where social, cognitive and physiological factors interact (Christopher 2013). The work that has been done in the field of LLLL mostly comprises language learning in an instructed setting in the form of additional language learning (Singleton and Pfenninger 2019). The majority of LLLL studies, however, have investigated the potential cognitive benefits ensuing from learning a language later in life (Bak et al. 2016; Bubbico et al. 2019; Ramos et al. 2017; Ware et al. 2017), and fewer but still a substantial number of researchers have investigated the socio-emotional (related to well-being) effects that follow from language learning (Klimova and Pikhart 2020; Klimova et al. 2021; Pikhart and Klimova 2020; Pot et al. 2019; Valis et al. 2019). In contrast, and counterintuitively, very few studies to date have looked at actual language learning outcomes for older adults in instructed second language acquisition (ISLA) contexts. Hence, it is not clear how older-adults learn or what works best for them. Indeed, most second language acquisition (SLA) theories are based on younger learners and this body of research has not been extended to older learners. However, late-life is generally viewed as a period for self-exploration, personal achievement, and self-fulfilment (Laslett 1991) where language learning fits in perfectly. Therefore, this study dives deeper into instructed LLLL by investigating proficiency gains ensuing a three-month English course for Dutch older adults.

2 Background

2.1 Language outcomes in LLLL

In one of the earliest investigations (Gruneberg and Pascoe 1996), 40 healthy older adult females (Mage = 70.45) participated in a single session in which they either learnt word pairs using either a so-called keyword method (i.e., a word is linked to an English similarly sounding word by means of an image) or by merely being presented with the word pairs. This vocabulary learning was done by listening to an audio tape consisting of 20 English words and their Spanish translation. Results showed that both receptive and productive recall were significantly better in the keyword method group when being lenient with rating (i.e., substantially correct showing some knowledge of what the Spanish should be; the so-called soft criterion). When being less lenient in rating correctness of responses (i.e., almost correct, but not strictly phonetically correct for the middle criterion and totally phonetically correct for the hard criterion) there were no differences between the groups. Additionally, it needs to be pointed out that listening to 20 word pairs in a single session is not reminiscent of an actual language course.

Other studies, too, have focused on very specific language outcomes, for instance on question formation. In Mackay and colleagues’ (2012]) study, nine older Spanish L1 speakers (Mage = 72) met individually with a native speaker on a weekly basis for five weeks. This included testing sessions as well meaning that there were three language sessions in the study during which participants and native speakers used communicative tasks to elicit question forms. The duration of each training session is not included in the study. Results showed that question formation in participants improved after the sessions but only two out of nine adults managed to sustain this improvement. Similarly, older adults have been shown to frequently pose questions in the language classroom, but that a large portion of these questions were unrelated to the progressivity of the lesson. Instead, they asked “wonderment questions”: questions on something they wonder about (van der Ploeg et al. 2022).

In one of the only studies to date that comprise a longer time course than a few sessions, the time course of improvement could be more closely monitored. In Pfenninger and Polz’s (2018) study, 12 German-speaking older monolinguals and bilinguals (6 German/Slovenian sequential bilinguals, Mage = 84.33; 6 German monolinguals Mage = 68.20) were enrolled in a four-week English course. Although participants did significantly better on overall proficiency, no significant improvements were observed on receptive tasks. Interestingly, the bilinguals did not outperform the monolinguals. Taking an even longer language instruction perspective, Kliesch and Pfenninger (2021) followed 28 German older adults (Mage = 68.5) learning Spanish for 30–32 weeks in small groups. Instruction comprised both in-person classroom instruction and Duolingo practice at home. The authors found that the increase in AL mainly occurred during the initial 10–20 week interval of learning.

Finally, some studies have investigated factors to influence AL learning in older-adulthood; the similarity of known languages to English, L1 skills, and English language exposure predicted English skills in older adults (N = 19; M = 72.92) (Blumenfeld et al. 2017). This is corroborated by Kliesch and colleagues (2018]), who found higher L1 verbal fluency to be related to faster language learning rates.

The scant evidence to date points in the direction of the possibility of successful language learning in older adulthood. Although older adults in comparison studies have in general been found to be slower in learning a new language than their young adult counterparts (cf. Marcotte and Ansaldo 2014), the learning attested is promising and fits in well with self-fulfilment and self-achievement that is said to characterise the third age (see above).

But these studies do collectively render the question what can be done to promote language learning success in late life. Other than the study by Gruneberg and Pascoe (1996), the studies to date have not investigated different language teaching pedagogies. Building on applied linguistics studies in younger learners, one of the most fiercely debated topics is the effectiveness of more explicit versus more implicit language instruction methods (cf. Andringa and Rebuschat 2015). To date, this has never been applied to an older adult context. This study is the first to exploratively do so in a small sample of older adults. The main objective in doing so is to shed light on the optimal language learning trajectory for an emergent but substantial group of language learners: older adults. As a second aim, the study outcome may reciprocally aid theorising in the realm of applied linguistics. To do that, it is pivotal to present the state-of-the-art of applied linguistic investigations into implicit versus explicit language teaching pedagogies.

2.2 Implicit/explicit language teaching pedagogies

At its core, implicit and explicit language instructional methods differ in the metalinguistic input learners do or do not receive (Ellis 1994; Norris and Ortega 2000). To further complement this distinction are focus on form (FoF), focus on forms (FoFs) and focus on meaning (FoM; Long 1991). On a continuum these methods range from FoFs, which is mostly described as traditional and explicit grammar-based language teaching where meaningful interaction is largely absent, to FoM which tends to exclusively focus on communicative meaning (Long and Robinson 1998) and which is often equated with implicit language instruction: learners are expected to learn the language based on natural and abundant exposure and input. In between FoFs and FoM is FoF, where a focus on conveying a message is typically prioritised but the teacher also pays explicit attention to the form of the message.

Over the years there have been many studies investigating the effectiveness of these different language teaching methods. However, a consensus on which method is optimal is hard to reach (Andringa and Rebuschat 2015). The meta-analyses by Norris and Ortega (2000), Spada and Tomita (2010), and Goo and colleagues (2015]) seem to point in the direction of a clear advantage of explicit language instruction. But the studies that formed the basis for their syntheses, however, have been criticised on three aspects: (1) one specific grammatical structure is targeted (Rousse-Malpat and Verspoor 2012), (2) training is short (DeKeyser 2013), and, (3) task procedures and test circumstances favour explicit knowledge (Andringa and Rebuschat 2015). Indeed, a more recent meta-analysis comparing implicit and explicit teaching approaches showed that outcome measures were significant moderators in the effects of implicit and explicit instruction: in spontaneous AL use, implicit instruction showed stronger effects (Kang et al. 2019), whereas previous meta-studies (Norris and Ortega 2000; Spada and Tomita 2010) mainly incorporated controlled outcome measures that relied on metalinguistic knowledge.

Partly to address the critique of a short training, several studies have carried out longitudinal classroom-based intervention studies on the difference between implicit and explicit language instruction (Gombert 2023; Piggott 2019; Rousse-Malpat and Verspoor 2012). Results showed that on usage-based holistic measures related to speaking and writing fluency, the implicitly taught group tended to outperform their explicitly taught peers. Whereas the explicit groups initially tended to outperform their implicitly taught peers on complexity, accuracy and fluency (CAF) measures, this difference disappeared with time. This state-of-the art of studies in this domain has so far relied solely on young (predominantly secondary school) learners.

Importantly, many studies have referred to the difference in terms of mostly implicit and mostly explicit conditions. Indeed, implicit versus explicit language instruction is a continuum and fully implicit or explicit instruction does not exist (Van den Branden 2016; Verspoor et al. 2015).

2.3 Implicit/explicit language teaching pedagogies in LLLL

Translating these findings on explicit versus implicit instruction to learners in the older adult life stage is impossible due to effective methods of late life language learning and teaching being greatly under-researched. Tentative evidence comparing different age groups of language learners have pointed to younger adults benefiting more from explicit grammar instruction than older adults do. This was attested in two studies that both targeted the learning of Latin. Cox and Sanz (2015) taught basic Latin morphosyntax to younger (N = 10; 19–27) and older (N = 11; 60+) English/Spanish bilinguals. In three sessions (duration unclear) over four weeks that participants completed, amongst other things, explicit grammar instruction and practice that provided them with correct/incorrect feedback without an explanation (i.e., no explicit instruction). Younger participants benefited more from explicit instruction, which the authors ascribe to the task’s memory demands but may also be due to the younger participants being much more used to this type of instructional setting. Significant differences previously observed between the age groups disappeared two weeks after the grammar lesson and practice session. The authors ascribe this to the fact that older adults’ language developmental process operated over a longer time compared to younger learners. Although Lenet and colleagues (2011]) also investigated Latin (semantic function assignment), they did incorporate an explicit and less explicit condition. Younger (N = 20; Mage = 18.7) and older (N = 20; Mage = 72.3) adults were provided with feedback that either just told them their answer was incorrect (less explicit), or told them why their answer was incorrect (explicit). Similar to Cox and Sanz’s (2015) study, the duration of the sessions is not mentioned in the article either. Results showed that the younger group did better in the explicit condition whereas the older adults did better in the less explicit condition.

Finally, Midford and Kirsner (2005) studied older (N = 22; Mage = 65.9) and younger (N = 22; Mage = 20.6) adults on an artificial grammar-learning paradigm. Grammar instruction varied in complexity and use of rules, leading to four conditions. After this training phase, with an unknown duration, participants were asked to complete a grammar-judgement task. In the simple-grammar condition with rules, the younger group performed better than the older group; however, in the complex-grammar condition without rules, these differences disappeared. The authors conclude that less explicit grammar instruction works better for older adults.

Collectively, these studies show a tendency for implicit instruction being more beneficial for older adults. At the same time, however, it needs to be pointed out that this conclusion is not without problems: groups were small, but most importantly, instruction and training sessions were very brief (and the precise duration was unclear) and did not resemble language course set-ups since they took place in a lab setting rather than classroom environment, limiting the generalisability of the studies’ results. Similarly, the language of instruction was either an artificial language or Latin. Finally, but crucially, the studies differentiated between no versus explicit instruction, albeit that explicit language instruction was operationalised differently (grammar explanation vs. feedback), but at no point was a more explicit versus more implicit learning conditions introduced. Lacking are studies building on tentative work (detailed in 2.1) that older adults can learn a new language but looking specifically at the optimal conditions to do this , in a naturalistic classroom setting where older adults are learning a new language over a longer period of time (DeKeyser 2013; Lambert and Kormos 2014; Larsen-Freeman 2015; Rebuschat 2015).

2.4 The present study

Following the caveat in earlier work, we designed a three-month English as an additional language (AL) course for older adults, specifically comparing more implicit versus explicit language instruction in an actual late-life language classroom setting. We aim to answer the following research questions:

Does older adults’ overall AL proficiency improve after a three-month language course and to what extent is this dependent on language teaching pedagogy?

To which extent do implicit versus explicit language teaching pedagogies differ in CAF and holistic rating scores of spoken assignments?

Based on earlier work, we hypothesise that older adults’ overall AL proficiency does show improvements after three months of language instruction (cf. Kliesch et al. 2021), but that the groups show differences in several areas of development. As there is more room to practise speaking in the implicit grammar condition (see below for details), we expect this group to show more substantial improvements on speaking tasks. Regarding the second research question, if the findings of our study resemble those attested in studies on younger learners, we hypothesise that explicitly taught older adults outperform implicitly taught older adults on holistic grammar and accuracy ratings. The implicitly instructed group, however, are expected to do better on measures of fluency (Piggott 2019; Rousse-Malpat and Verspoor 2012).

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Sixteen Dutch older adults (M = 71;9, SD = 6;3, 13 female) participated in our longitudinal study till the end. Educational levels varied from secondary school to university degrees. All participants were retired at the time of testing; former professions included police officer, secretary, teacher, and business owner. Based on self-reports, the average number of languages/dialects spoken per participant was 4 (this included languages learnt at school or other places and regional languages/dialects). An additional 14 participants initially started with the English course but dropped out due to health issues (N = 6), difficulty with online technology (N = 4), perceived difficulty of the course (N = 3), and not liking the teaching pedagogy to which they were assigned (N = 1; see below for further details). A number of inclusion criteria were in place. Based on Nijmeijer and colleagues (2021]), older adults had to: (a) be aged 65–80, (b) have a maximal B1 English proficiency level (CEFR), and (c) have no cognitive problems (based on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA]; Nasreddine et al. 2005). Participant recruitment took place via Facebook advertisements and a message in newsletters of older adult organisations in the Netherlands. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of X (61890455).

3.2 Study design

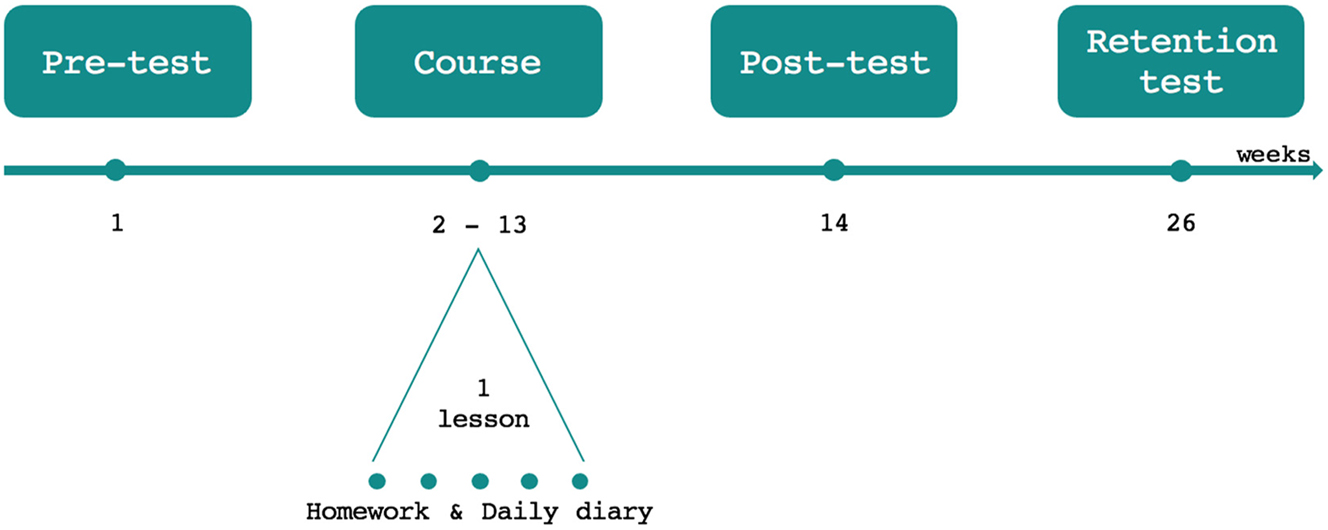

Our study followed a pre-test, post-test, retention test design where the retention test was administered three months after the post-test. Between the pre-test and post-test, participants followed a three-month English course that included weekly group lessons, and homework with a daily diary. The full experimental design and timeline of the study is detailed in Figure 1.

Study design with test moments and design of the language course.

3.3 Course design and language learning procedure

Participants took part in a three-month English course specifically developed for, and targeted towards, older adults. This course consisted of twelve two-hour lessons (see Appendix A for topics and features for each lesson). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the course was held online. In order to investigate the implicit/explicit dichotomy, the course was offered in two versions to which participants were randomly assigned: one with more explicit language instruction (N = 8), operationalised mainly as explicit grammar instruction, and the other with mostly implicit instruction (N = 8), devoid of explicit grammar rule instruction. In line with previous research (Van den Branden 2016; Verspoor et al. 2015), in our course design we adhere to the premise that ‘purely’ implicit or explicit language teaching is difficult to accomplish (Long 1991). The explicit condition was not fully explicit because grammar was not explained in absence of any other linguistic input. Additionally, in the implicit condition, explicit attention was sometimes paid to word meaning or pronunciation.

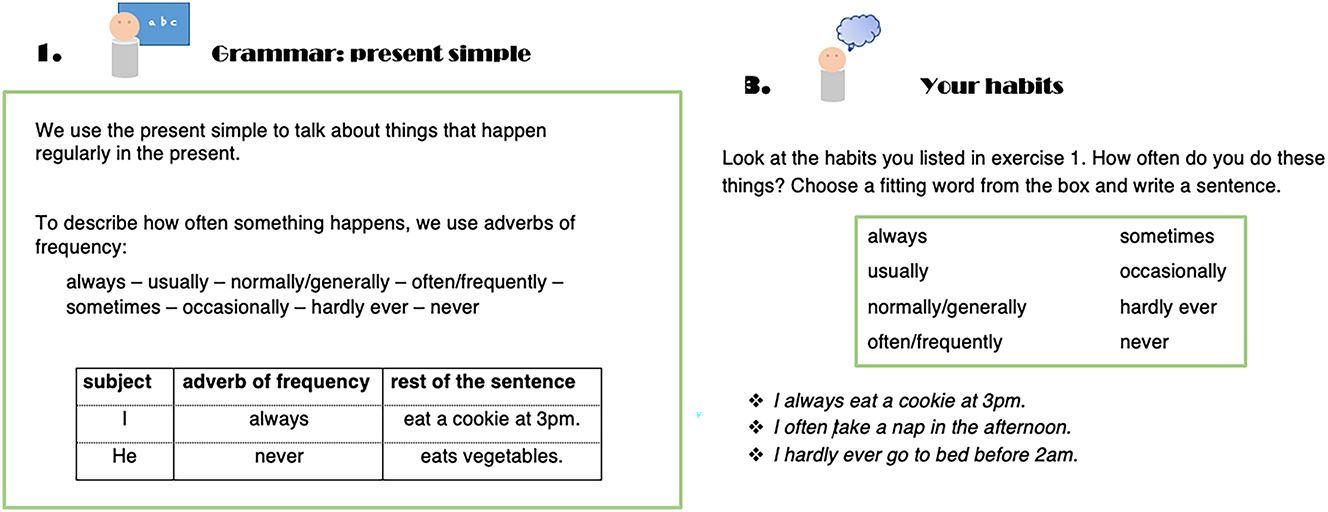

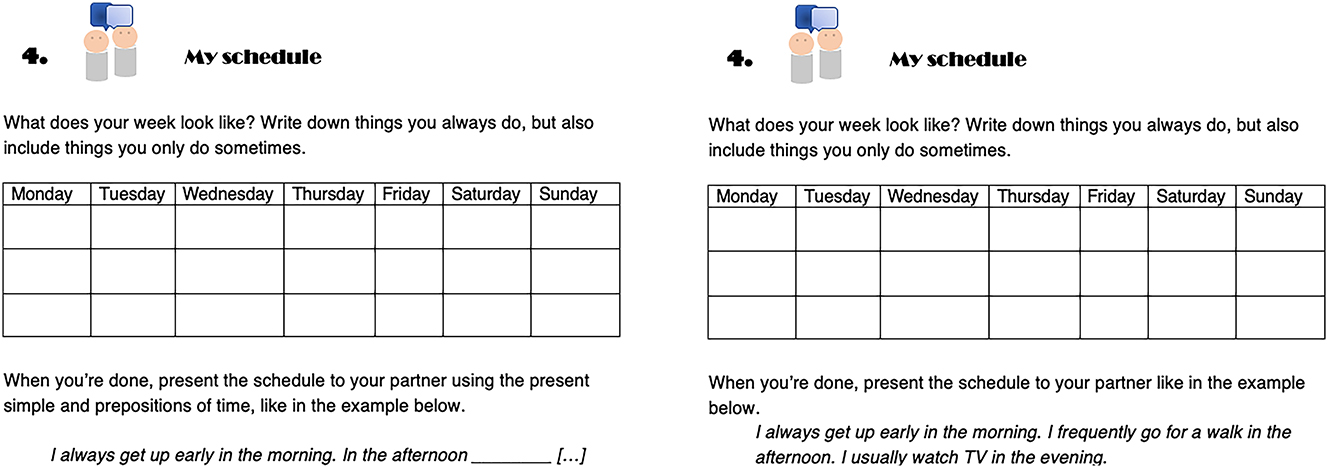

Both classroom materials and homework assignments were adapted to fit either implicit or explicit instruction. In the explicit condition, grammatical constructs were explicitly explained (i.e., when to use a tense and how to form it), whereas the implicit condition included example sentences and exercises with the target structure, so essentially was input only. Figure 2 provides an example of the different exercises in the conditions when it comes to grammar explanations.

Explicit (left) and implicit (right) explanation of present simple.

Other than the explicitness of grammar instruction, the two courses were identical. This meant that exercises and topics were also kept as similar as possible, except for the explicitness of the grammatical structure. In another example in Figure 3, the explicit condition is prompted to use the present simple, whereas the implicit condition is provided with more example sentences without changing the essence of the exercise on describing habits.

Explicit (left) and implicit (right) exercise on describing habits.

Two rounds of pilots were carried out before data collection commenced (respectively N = 2, M = 77;9, SD = 3;6, 2 male; and N = 8, M = 70;9, SD = 4;3, 6 male) on both implicit and explicit conditions (explicit N = 6; implicit N = 4). The main purpose of the pilots was to ascertain feasibility of the testing sessions (including materials) and the course itself (i.e., whether the instructional conditions could be maintained as desired). As a result of the pilots, minor alterations were made which mainly pertained to homework and online formats, such as switching to Google Docs (instead of Google Classroom).

Both during the pilot rounds and the actual data collection, teachers were instructed on what to say in case participants in the implicit group asked explicit grammar questions. These answers followed along the lines of ‘this is not important right now; we are focusing on other things now’. However, none of the participants in the implicit condition ever asked such questions.

3.4 Language tests

During all three testing moments (pre, post and retention test), several language proficiency tests were administered via Google Meet, comprising both productive and receptive language tasks.

3.4.1 Productive language tasks

For productive language tasks, an IELTS-inspired speaking task was used (van der Ploeg et al. submitted). This test consisted of part A – conversation – where the researcher asked participants questions on a certain topic (e.g., their village, their house, and their favourite food). Next, in part B, participants were given a topic (hobbies, famous people, and books) and, after a few minutes of preparation, asked to briefly present on this topic without being prompted by the researchers with focused questions. Both parts were recorded and rated by three independent raters using the IELTS rubric (fluency, grammar, lexical resources, and pronunciation), from which also the overall IELTS score was calculated, and an overall CEFR score. Ratings showed good interrater reliability (Kline 1999) (α = 0.67); see below for details. We opted for two different frameworks to see if they would show different results, as close to no research on LLLL proficiency has been done.

Additionally, a letter verbal fluency test was used (cf. Nijmeijer et al. 2021). Here participants were asked to name as many words starting with a certain letter within the time span of 1 min (i.e., CFL, PWR and FAS). The final score is the number of correct words and versions were randomly assigned for the different testing sessions and participants.

Finally, in addition to the measures described above, which were administered at pre-, post- and retention tests, participants also recorded themselves weekly as part of their homework exercises. These recordings were sent to the course instructor via WhatsApp audio messages. Participants were asked to give their opinions on different topics or tell the teacher about something including (a) ideal holidays, (b) should public transport be free, and (c) a typical day in their life. A total of 22 assignments divided over twelve weeks formed part of the homework. However, not all participants completed all homework speaking assignments. Additionally, three participants were excluded from analysis as one of them had only completed one speaking assignment and the other two wrote down text for the assignment and read that prepared text out loud. This left us with a total of 201 recordings divided over thirteen participants; participants thus individually completed between 8 and 21 speaking assignments over the course of three months (M = 15.09, SD = 4.00). These recordings were then holistically rated by three independent raters each on a rating scale developed by Piggott (2019]; Appendix B). Raters had been trained to standardise the rating process prior to listening to the assignments. The average, minimum and maximum of the SDs between raters can be found in Table 1 below. As none of the SDs were exceptionally high, we can assume agreement between raters.

Average, minimum, and maximum SDs of raters on the four holistic rating scales.

| Vocabulary | Grammar | Fluency | Functional adequacy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average SD | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.62 |

| Minimum SD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum SD | 1.53 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 1.53 |

Homework recordings were also transcribed orthographically and rated on Complexity, Accuracy and Fluency (CAF). For complexity, the moving-average type–token ratio (MATTR) was used to measure lexical complexity (Covington and McFall 2010) (as this measure has been claimed to be least affected by excerpt length [Zenker and Kyle 2021]). Transcripts with fewer than 50 tokens were, however, not included in the analysis (Zenker and Kyle 2021), meaning that the analysis was run on 134 audio files.

Syntactic complexity was measured by means of the number of coordinate phrases per T-unit using TAASCC (Kyle 2016). In this analysis, pruned manuscripts were used that excluded self-corrections and repetitions. To measure accuracy, the number of structural and lexical errors were counted. Structural errors do not change the meaning of the sentence and include things such as verb use and verb form errors (e.g., ‘When I are in England…’). Lexical errors, on the other hand, are meaning-based errors such as L1 interference errors (e.g., ‘It is a shopping evening’ which is a literal translation from Dutch). A second rater assessed 10 % of the data and both raters showed substantial reliability for structural and lexical errors respectively (α = 0.78; α = 0.73) (Kline 1999).

Finally, fluency was operationalised by means of a number of separate measures: mean number of words per minute; number of silent pauses per minute; mean length of silent pauses; number of filled pauses per minute; number of repairs/repetitions per minute; and, speech rate. These measures have been used in previous studies on fluency in older adults (van der Ploeg et al. submitted) and were calculated using a PRAAT script (De Jong and Wempe 2009).

No written measures were included as a needs analysis found that older adults want to (re)learn language in order to be able to speak the language (Authors submitted).

3.4.2 Receptive language tasks

Receptive tasks included the IELTS listening test where participants randomly received one of three versions. Scores on this task could vary between zero and a maximum of twenty. Participants received the paper form at home and were told to fill it out while listening to the audio played over their device by the experimenter during the online test session. As the participants received the listening task at home and testing was repeated, using three versions of the task was deemed necessary in order to obtain objective results. The different versions were similar in design and difficulty. Additionally, both Dutch and English receptive vocabulary tests were administered. For Dutch this was Lextale (Lemhöfer and Broersma 2012) which was administered via the Lextale website (scoring range between 1 and 100). For English the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; Dunn and Dunn 2007) was used in the form of a powerpoint presentation and the non-standardised scores were used, as English was not participants’ first language.

3.5 Analysis

Linear mixed model analyses were run to analyse the data using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R (R Core Team 2021). Language test scores were included as dependent variables, test moment (pre-, post-, and retention test or week/day) and condition (implicit and explicit) were included as independent variables with an interaction. Participant, finally, was included as random effect, as older adults have been shown to show substantial individual variation (Christensen 2001; Grotek 2018). Additionally, in the homework models, task was also included as a random effect as the topics of the tasks differed and this may have influenced the results. Conditional R2 was computed using the mgcv package (Wood 2017) and the scores for all language tests were centred around zero, based on the pre-test scores. Graphs were created using ggplot2 (Wickham 2016). Model output for all models can be found in Appendix C.

4 Results

4.1 Global proficiency measures

4.1.1 Speaking

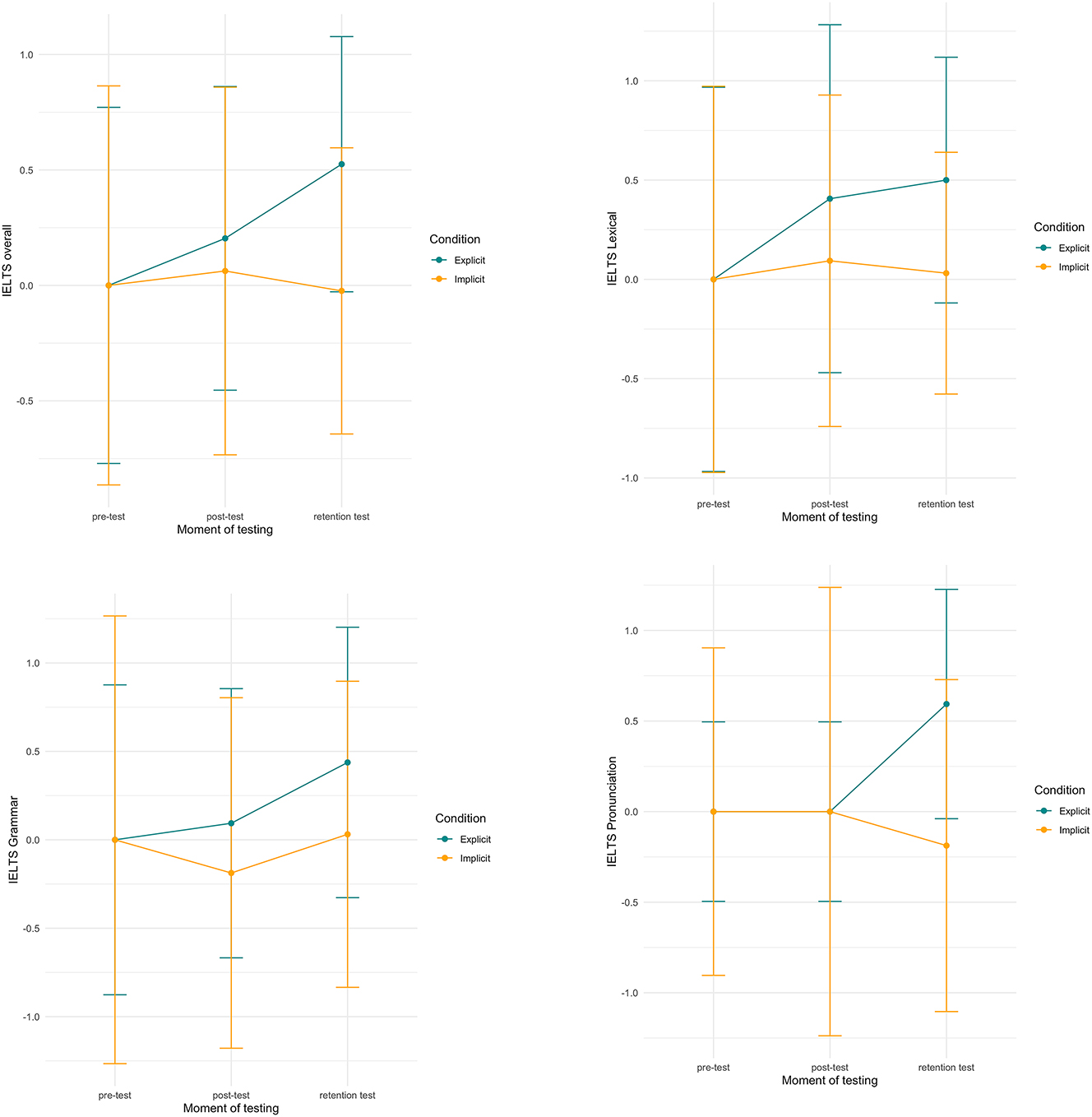

In the overall IELTS rating of the speaking tasks, we found a significant effect between time and speaking scores (conditional R2 = 0.78). Our model showed a significant main effect for retention test (b = 0.52, SE = 0.17, t = 3.04, p < 0.01, CI[0.18, 0.87]), which means that, regardless of condition, older adults spoke better English overall as part of the retention test than in the pre-test. Subsetting showed that there was no significant difference between post-test and retention test (p = 0.071). Figure 4 shows both the explicitly and implicitly taught groups’ performance on the speaking task.

IELTS speaking scores per condition over time (left to right: overall, lexical resources, grammar, pronunciation). Note: scores are centred around zero.

As a next step, we investigated the IELTS ratings in more detail and found a significant effect between time and IELTS speaking – lexical resources scores (conditional R2 = 0.72). Our model showed a significant main effect for retention test (b = 0.50, SE = 0.23, t = 2.22, p < 0.05, CI[0.04, 0.96]), so – similar to overall IELTS speaking scores – older adults, regardless of condition, did better on the retention test on lexical components in speaking than in the pre-test. Subsetting showed that there was no significant difference between post-test and retention test (p = 0.68). In Figure 4 participants’ lexical speaking scores are visualised, split per explicit and implicit teaching condition.

For IELTS speaking – grammar scores in interaction with time we also found a significant effect (conditional R2 = 0.81). Our model showed a significant main effect for retention test (b = 0.44, SE = 0.21, t = 2.09, p < 0.05, CI[0.01, 0.86]), where, again, older adults, regardless of condition, did better on the retention test on grammar components in speaking than in the pre-test. Subsetting showed that there was no significant difference between post-test and retention test (p = 0.109). See Figure 4 for a visualisation.

Finally, for IELTS speaking – pronunciation, the trend was the same as for the other three IELTS test components: we found a significant effect of time (conditional R2 = 0.76). Our model showed a significant main effect for retention test (b = 0.59, SE = 0.21, t = 2.82, p < 0.01, CI[0.17, 1.02]): regardless of condition, older adults’ English pronunciation performance was significantly better on the retention test compared to the pre-test. Subsetting showed that in the retention test, participants did significantly better than in the post-test (p < 0.01). Below, Figure 4 shows the performance of both groups.

Although this has to be treated with caution, Figure 4 does visualise different trends in both conditions (though at no point resulting in significant differences). Whereas the implicit group mainly stays stable in their development before and after the course, the explicit group shows an increase in their scores. This increase is sustained in the retention test which, in all four cases, shows even higher scores than the post-test.

For the CEFR rating of the speaking task we found significant effects between time and speaking scores (conditional R2 = 0.68). Our model showed a significant main effect for post-test and retention test (b = 0.32, SE = 0.12, t = 2.71, p = 0.01, CI[0.08, 0.56]; b = 0.46, SE = 0.12, t = 3.93, p < 0.001, CI[0.22, 0.70]): older adults, regardless of their assigned teaching method condition, performed better in both post-test and retention test compared to pre-test. No significant difference in performance was found between post-test and retention test (p = 0.23).

As opposed to IELTS overall, as well as its lexical, grammar and pronunciation components and for the CEFR rating on the basis of the IELTS speaking test, IELTS fluency ratings did not reveal any improvement over time nor were any effects of condition found.

4.1.2 Vocabulary

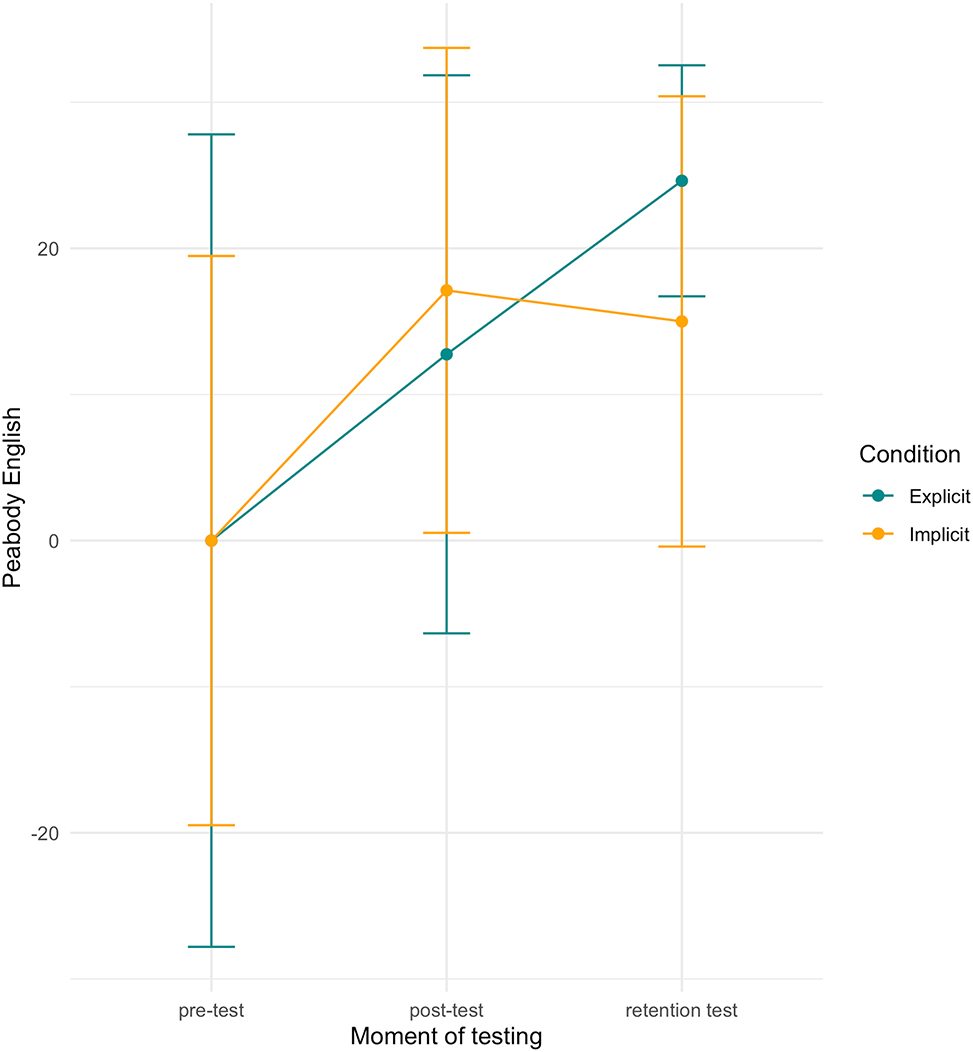

Turning to receptive vocabulary, we found a significant effect of time for English vocabulary (i.e., performance on the Peabody picture vocabulary test) (conditional R2 = 0.73). Our model showed a significant main effect for retention test (b = 12.75, SE = 5.42, t = 2.35, p < 0.05, CI[1.79, 23.71]; b = 24.62, SE = 5.42, t = 4.54, p < 0.001, CI[13.67, 35.58]), pointing to older adults, regardless of condition, to show the best receptive command of English words at the time of the retention test compared to their performance on the pre-test. Subsetting showed that participants did better on the retention task than on the post-test (p < 0.05). In Figure 5 both groups’ performance is plotted.

Peabody scores per condition over time. Note: scores are centred around zero.

4.1.3 Listening

For IELTS listening, no significant effects were found for time or condition. Participants averaged at 9.66/20 in the pre-test.

4.1.4 Verbal fluency

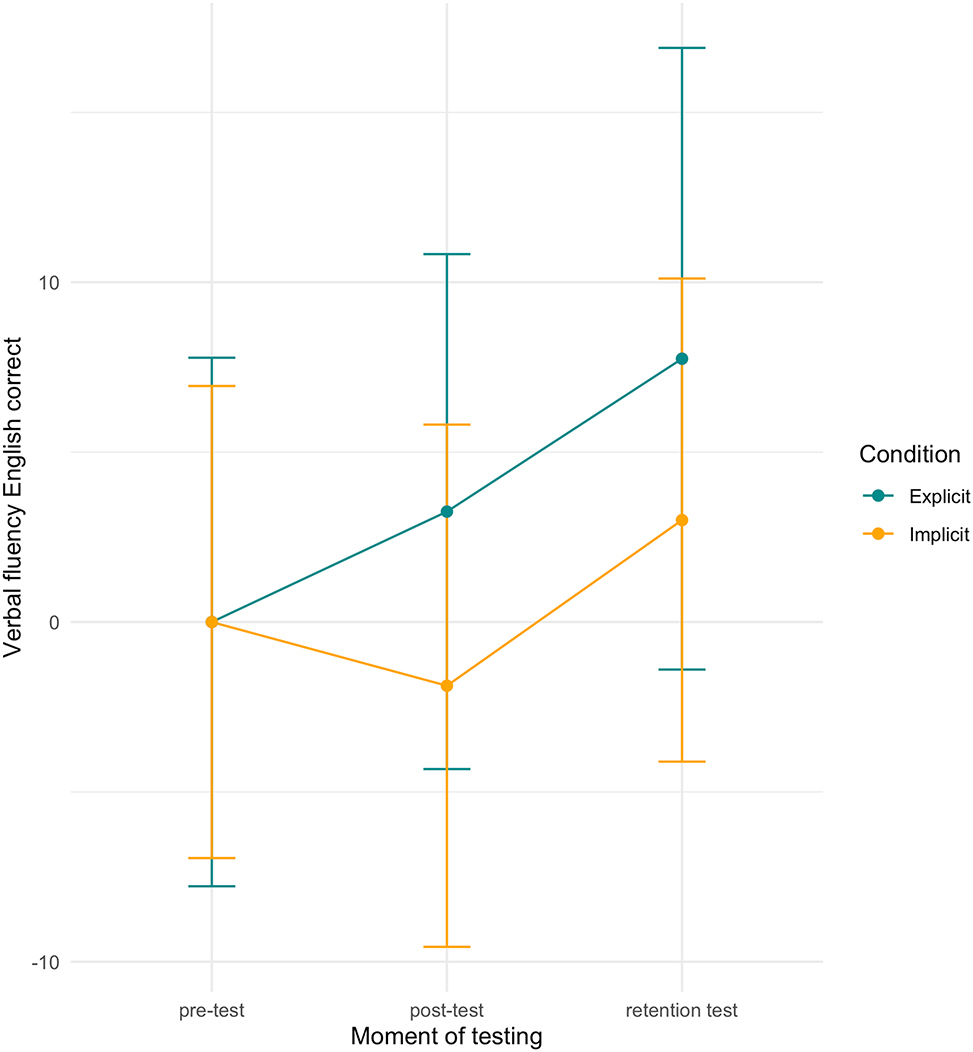

For English verbal letter fluency, we found a significant effect between time and scores (conditional R2 = 0.66). However, our model only showed a significant main effect for the retention test (b = 7.75, SE = 2.44, t = 3.17, p < 0.01, CI[2.82, 12.68]). Regardless of condition, and similar to receptive English vocabulary, older adults named more correct words in the retention test. No significant differences were found between groups between post-test and retention test (p = 0.68). Figure 6 shows participants’ performance.

English verbal fluency scores per condition over time. Note: scores are centred around zero.

4.2 CAF versus holistic scores of spoken homework samples

4.2.1 CAF

For complexity, both lexical complexity (as measured by the MATTR) and syntactic complexity (as measured by coordinate phrases per T-unit), no significant effects were found across time or between the conditions.

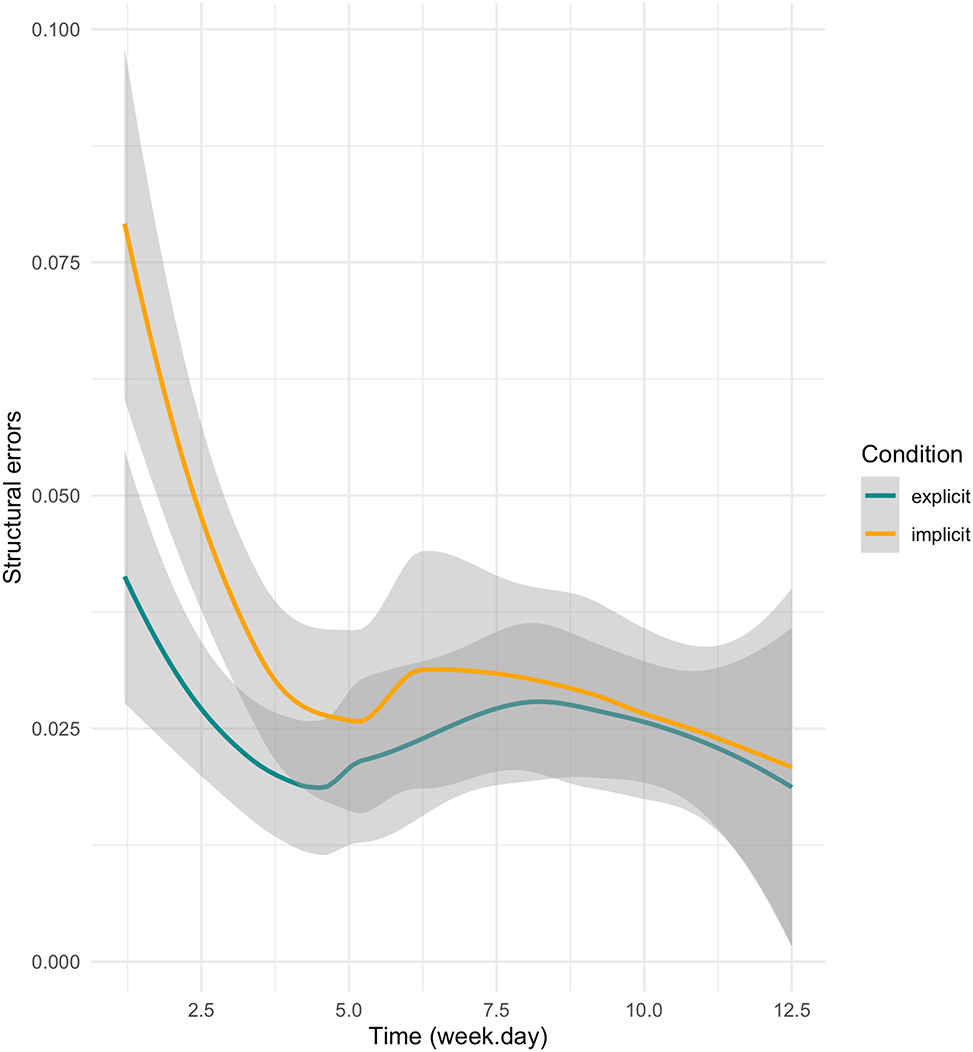

For accuracy, we found no significant effects for lexical errors. For structural errors, however, we found a significant main effect (conditional R2 = 0.41). Our model showed a significant main effect of condition (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, t = 2.77, p < 0.01, CI[0.01, 0.04]) and an interaction between time and condition (b = −0.00, SE = 0.001, t = −2.92, p < 0.01, CI[−0.00, −0.00]). More specifically, our results indicate that, even though the implicitly taught group made more structural errors than the explicitly taught group overall, compared to the explicit group the implicit group showed a significant decrease in structural errors over time (see Figure 7).

Structural errors corrected for length over time per condition including SEs.

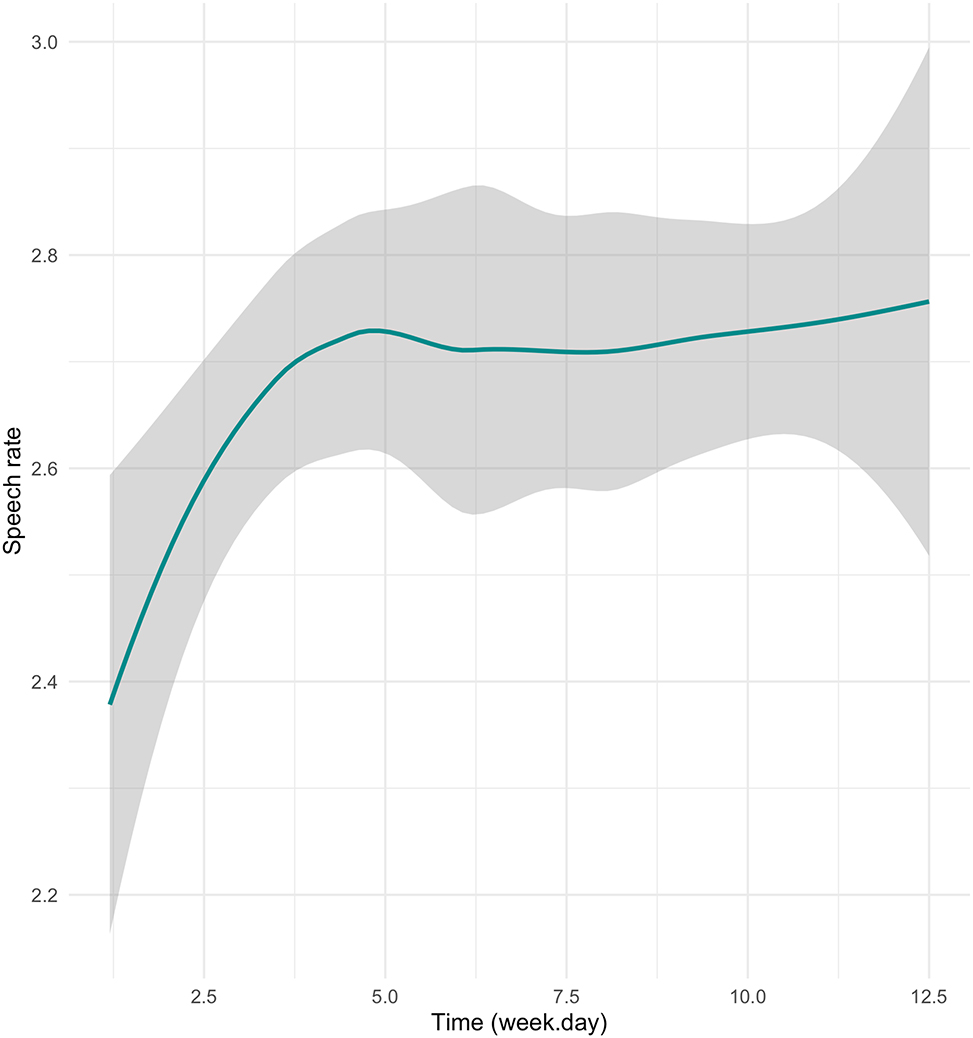

For fluency, only one significant main effect was found for the various fluency indicators under investigation: for mean number of words per minute, number of silent pauses per minute, mean length of silent pauses, number of filled pauses per minute, and number of repairs/repetitions per minute no main effect was found. For speech rate (conditional R2 = 0.72), the model showed a significant main effect of time (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t = 2.78, p < 0.01, CI[0.01, 0.05]). This indicates that older adults’ overall speech rate improved over the course regardless of condition. Indeed, we did not find any significant main effect of condition (p = 0.21) or interaction between condition and time (p = 0.97). See Figure 8 for a visualisation of these results.

Speech rate over time per condition including SEs.

4.2.2 Holistic scores

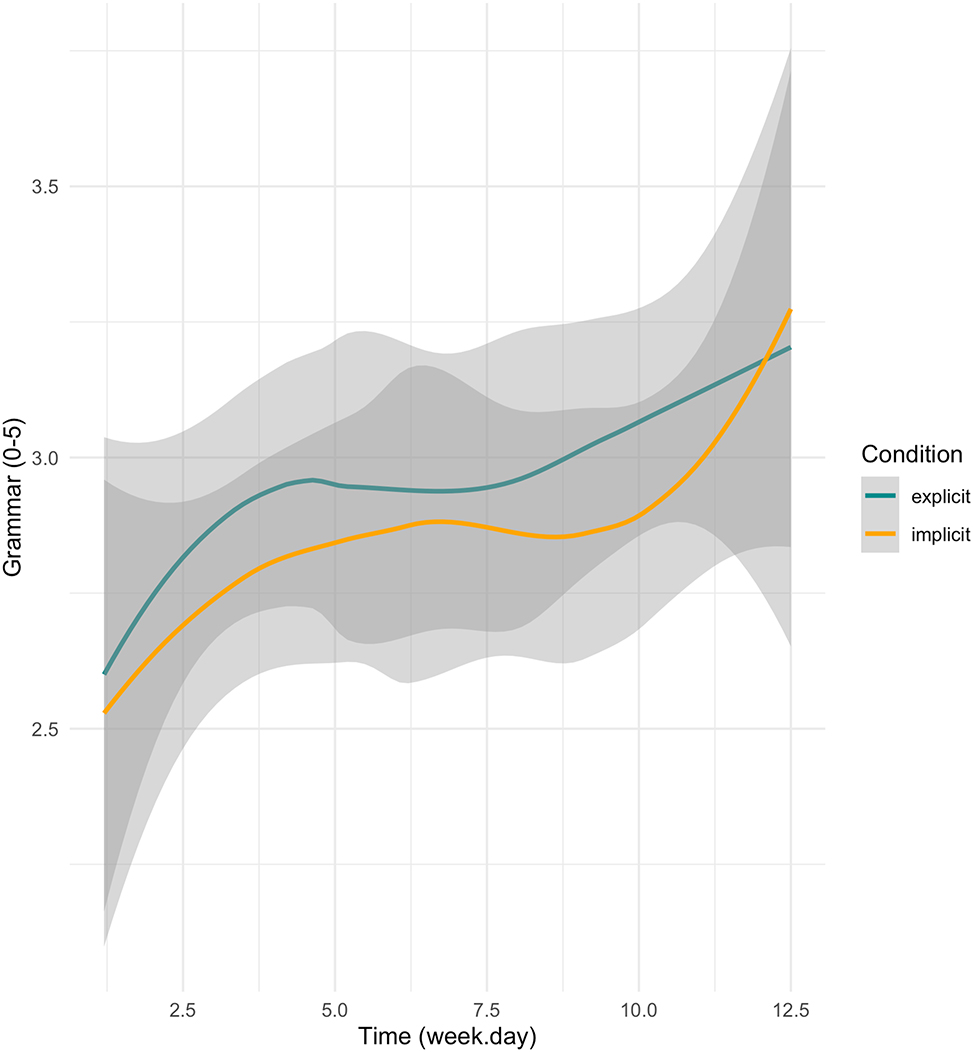

For holistic grammar scores we found a significant effect (conditional R2 = 0.44). The model showed a significant main effect between time and grammar scores (b = 0.04, SE = 0.02, t = 2.29, p < 0.05, CI[0.01, 0.08]), meaning that, regardless of condition, our participants’ holistic grammar scores improved over the timespan of the course. The model did not show any significant main effect of condition (p = 0.62) or interaction between condition and time (p = 0.58). This is visualised in Figure 9.

Holistic grammar scores over time per condition including SEs.

For vocabulary, fluency, and functional adequacy, no significant effects were found.

5 Discussion

This longitudinal study investigated the language development of older adults learning English for three months as either a mostly implicit or mostly explicit language instruction setting. More specifically, we aimed to answer the question whether 1) older adults’ proficiency shows an increase after a three-month language course and 2) to what extent this is dependent on language teaching pedagogy. Underlying these questions is the extension of applied linguistics work to comprise an increasing group of older adult language learners. In our study we investigated L1 Dutch older adults learning English as an additional language.

Regarding the first part of this research question, we hypothesised older adults to develop their English language skills (cf. Kliesch et al. 2021) and we found them to do so in a number of areas. For IELTS speaking (including the subcomponents lexical resource, grammatical range and accuracy, and pronunciation) and overall CEFR scores, we found older adults to significantly improve over the three months time of the language course. Similar results were found for receptive vocabulary (i.e., PPVT) and verbal fluency as a measure of productive vocabulary. Furthermore, our dense spoken data showed speech rate and holistic grammar scores to improve over the course of twelve weeks, as assessed by independent raters. Our results thus showed that even a short late-life language learning experience may lead to improvements in AL proficiency. This has been attested in earlier work too (Kliesch et al. 2021; Pfenninger and Polz 2018).

Interestingly, the older adults in our study did not improve on listening scores and neither did participants in Pfenninger and Polz’s (2018) study. A potential reason why listening scores did not improve after the course might be hearing loss and reduced processing speed evidenced in older adults (Kliesch et al. 2018). Additionally, due to testing being online in our study, this meant that the listening test was also administered online and it may very well be that internet connection strength and other technology-related factors influenced older adults’ performance on this task. Related to this, multiple participants mentioned that the audio was too shrill. Hence, all of these above-mentioned issues need to be kept in mind when providing older adults with listening tests and tasks. However, we do believe it is important to incorporate listening skills in LLLL studies even though Kliesch and colleagues (2018]) advocate for using the written modality for testing general AL skills. Indeed, older adults themselves have named communication to be one of the reasons for wanting to pick up LLLL (van der Ploeg et al. submitted) and listening is an integral part of communication skills. The same argument can be made for including speaking skills.

Other results in our study are not in line with previous research: whereas Kliesch and Pfenninger (2021) found lexical complexity to improve during initial language learning, we did not replicate this finding in our sample. However, the language taught differed (English vs. Spanish) which means that the initial level of proficiency also differed as English is a language encountered frequently in the linguistic landscape of the Netherlands whereas this is not the case for Spanish in Austria/Switzerland. Hence, initial language proficiency development will be faster compared to the later language-learning stages.

Furthermore our study and Kliesch and Pfenninger’s (2021) differ in terms of errors the older adults were found to make. Kliesch and Pfenninger focused on morphosyntactic accuracy and transfer errors of a lexical nature in their study. Although the categories are not fully comparable to our structural and lexical errors, there is of course overlap. For both of their error categories, the authors found improvements during the initial language learning stages. In our study, however, we did not find such effects, except that the learners in the implicit condition produced significantly fewer structural errors over time (see below). Indeed, in our study most of the improvements are found at the end of the course, often even after the language learning is over. This is in line with Cox and Sanz (2015), who found older adults’ language development to operate over a longer time course compared to younger adults. An explanation as to the origin of these differences might be the type of elicitation task: Kliesch and Pfenninger collected spoken data during semi guided 5-min interviews whereas our data originated from tasks completed by the participants themselves on specific topics.

Finally, our global spoken data (pre-post-retention data) showed older adults to improve in their scores, but only in the retention test. Hence, there was no significant improvement from pre-test to post-test but there was from pre-test to retention test. This is not in line with Kliesch and Pfenninger (2021), who found that the increase in AL mainly occurred during the initial 10–20-week interval of learning. It is, however, in line with Cox and Sanz’ (2015) longer time course of language development. Again, the reason why Kliesch and Pfenninger (2021) found initial language learning effects might simply be that language that was offered as part of the course and its corresponding starting level. We do not believe that there is a test–retest effect as participants completed a different version of the tests in the pre-, post- and retention test.

The other language measures we wish to touch upon are the measures that did not show a significant development over time. Most of the measures that did not show effects over time (or per condition) are the homework speaking tasks. As these tasks took the form of monologues, this might be the reason we did not find effects: monologues are radically different from naturalistic conversation-type interactions. Producing a monologue requires multiple cognitive functions compared to dialogues: planning, monitoring, retrieval and working memory (cf. Garrod and Pickering 2004). And precisely these cognitive functions have been found to decline as a function of ageing (Cox and Sanz 2015; Mackey and Sachs 2012). Hence, a lack of effects on such a monologue task might be explained by decreased cognitive functioning in older adults and by the fact that it is a specific skill that is not trained to the same extent in all individuals. The fact that we did find an effect of speech rate might simply be because our older adults became more comfortable speaking allowing them to increase their speech rate. An additional explanation could be that their lexical access skills had improved, leading them to find words more quickly and, therefore, talk at a faster rate.

Our second research question focused on the extent to which language development differs for different language teaching pedagogies. Here we hypothesised the groups to show differences in several areas of development (e.g. for the implicit group to show bigger improvements on speaking tasks). Our findings, however, did not show this difference between conditions. The one difference that was attested between the implicit and explicit condition in our study was that the implicit group made significantly more structural errors and yet at the same time also significantly declined in this type of error during the language course compared to the learners in the explicit group. A possible explanation for this is offered by Piggott (2019) who argues that the implicit group might not mind making mistakes as much as the explicitly taught group: “it is conceivable that the implicit group was less aware of or restricted by errors such as using their L1” (p. 117). This might seem contradictory to the fact that they improved more rapidly, but underlines the need for time-trajectory data.

Interestingly, even though we found an effect of time on holistic grammar scores and IELTS grammar scores, there was no effect of group. Hence, the explicit group did not outperform the implicit group on grammar scores contrary to expectations and, contrary to robust evidence in younger learner demographics. Indeed, these two findings are not in line with previous longitudinal implicit/explicit grammar instruction studies with younger participants. In Piggott’s (2019) study the explicit group made more verb form and verb use errors (part of our structural errors) in the first year while, at the same time, the implicit group received higher holistic speaking scores. Both Rousse-Malpat and Verspoor (2012) and Gombert (2023) also found their implicitly instructed groups to outperform the explicit group on general proficiency holistic scores (as measured by the SOPA; Rhodes 1996).

Even though previous studies have demonstrated clear differences in AL development when comparing implicit and explicit approaches, our study has not yielded such an effect. There are several reasons why this might be the case. First of all, our training was shorter than the abovementioned studies: three months (our study) versus 21 months up to six years. Notably, effects of implicit grammar approaches take a longer time as more input is needed (Hulstijn 2015), which might be especially true for older adults (Marcotte and Ansaldo 2014). Additionally, our language learning conditions might have been too similar: both incorporated task-based language teaching with a focus on speaking (as this was indicated as a wish by older adults; van der Ploeg et al. submitted) as opposed to, for example, Piggott (2019) whose conditions differed more. However, in order for older adults to finish a language course it also needs to be fun enough to finish. Overall, however, language learning might just take more time for older adults (cf. Cox and Sanz 2015).

In addition to the longitudinal studies described above, the studies incorporating implicit/explicit language learning in older adults have shown implicit grammar instruction to be more effective for older adults (Lenet et al. 2011; Midford and Kirsner 2005). The results in our study are not in line with these previous studies. However, participants in Midford and Kirsner’s (2005) study were younger than our participants, which might explain why they found implicit language learning to work better (Cherry and Stadler 1995; Howard and Howard 1997). Nonetheless, these studies are vastly different from our study, making direct comparisons hard: training was short, conducted in a lab setting, focussing on a language that is not used in daily life, and without a fully implicit condition but rather a less explicit condition.

In relation to our research questions and hypotheses, individual variation also needs to be addressed. As shown by the large SEs in our models, our dataset showed substantial individual variation, something that is generally accepted in gerontology: “this age group is characterised by the largest diversity of any age groups involved in education” (Grotek 2018; p. 128). Research has shown that both cognitive and L2 performance can fluctuate within an individual on a day-to-day basis (Christensen 2001; Neupert and Allaire 2012; Strauss et al. 2002), and inter- and intra-individual differences are even known to increase over the lifespan (Christensen 2001). Hence, generalising across participants is hard, and it is even harder to speak of “the” typical late-life language learner.

5.1 Limitations

There are several limitations to our study that we wish to touch upon. First of all, our exploratory study’s sample size was small. This means that the statistical outcomes need to be interpreted with caution. In addition, we did not control for participants’ English starting level as there was not enough power in our models to do so. However, we urge future studies to include this variable in their models. Secondly, staying on the topic of statistics, our homework data consisted of different tasks. Even though we controlled for this potential task effect in our statistical models, future research might want to incorporate a single measure over time. This, of course, comes with new challenges, such as fatigue and potential drop-out, something that is especially present in older-adults. Another factor that needs to be taken into account is that three older adults had to be removed from the analysis of homework data as they had read their spoken assignments out loud. For these participants it was very clear that they read their assignments out loud (i.e., turning papers can be heard in the recordings), but there might of course be more older adults who did this, influencing the results. A third limitation is the fact that both testing sessions and actual teaching and homework had to be organised in an online setting. Although our study has shown that such a set-up is feasible for older adults, it also might have influenced the results as listening tasks in such a set-up are much harder to carry out and technical issues with, for example, internet connections will always be present. Finally, there are two limitations we already touched upon when discussing the results: language training might have been too short to demonstrate differences between the two conditions, and the implicit and explicit condition might have been too similar.

5.2 Conclusions and implications

Our small-scale longitudinal dense data study showed that it is possible for older adults to develop their AL proficiency, even during a relatively short course of three-months. Moreover, such language proficiency gains can even be attained in an online language course. Regarding implicit and explicit grammar instruction, we found no noteworthy differences: the implicit condition showed more structural errors yet also significantly went down in these errors during the course.

From an SLA-theory perspective this means that previous research into implicit and explicit grammar instruction has been biased towards younger learners and that it remains to be seen whether the results regarding younger learners hold true once older language learners are incorporated into research designs.

Practically speaking, seeing that there were no substantial differences between the two teaching pedagogies, and the fact that participant attrition was quite high in this study, it might be best to adopt a teaching pedagogy that meets older adults’ language learning needs best. A needs analysis revealed older adults to want explicit explanation of grammatical constructs (van der Ploeg et al. submitted), and one of our participants dropped out of the course due to a lack of explicit grammar instruction. Hence, a communicative-focused teaching pedagogy that does include some explicit grammar instruction might be most suitable for older adults.

Finally, our study showed the late-life language learner (as far as one can talk about ‘the’ late-life language learner) to be very invested in the course. The fact that multiple participants had to be excluded from part of the analysis due to them reading assignments out loud shows that they want to do a good job and that they put a lot of energy and effort into their language learning. By doing so, they show agency over their language learning process.

Funding source: Gratama Stichting

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019-11

Appendix A: Topics and features of the language course

| Lesson | Topic | Grammar goal | Communicative goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Getting to know each other | Open, closed, and WH-questions | Introducing yourself and talking about yourself; Asking somebody questions; Pronouncing the letters of the alphabet |

| 2 | Presents | Verbs of preference | Expressing your preferences; Talking about likes and dislikes |

| 3 | Getting around in Groningen | Prepositions of place | Giving directions; Talking about Groningen |

| 4 | Habits | Present simple; Want and would like/love to | Talking about your habits; Talking about habits you would like to have |

| 5 | Hobbies and Activities | Present continuous | Talking about activities you are doing; Having a discussion about activities |

| 6 | This is me | Comparative and superlative | Comparing and contrasting things |

| 7 | Life in the Middle Ages | Past simple | Talking about things that happened in the past |

| 8 | Yesterday | Past simple | Talking about things that happened in the past |

| 9 | Doing something for a long time | Present perfect continuous | Talking about actions and situations that have been going on for a longer time |

| 10 | To the future | Future (will) | Talking about things that you predict to happen |

| 11 | My learning progress | Future (going to) | Talking about things that you know will happen |

| 12 | Learning (new) skills | Reflecting on the learnt grammar | Reflecting and talking about your learning process |

Appendix B: Holistic rating scale speaking (Piggott 2019)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vocabulary

Density, diversity, and sophistication |

Produces only isolated words combined with words from L1 and/or incorrect use of words. Unable to produce all words needed to communicate the entire message. Clearly struggles. | Produces mainly isolated words and phrases. Phrases and chunks can occur but are not always target-like. Sporadically uses words from L1. | In addition to isolated words, uses phrases/chunks. Use is quite diverse but not always accurate or sophisticated. Able to communicate with words in English without falling back on L1 words. | Is able to use a wide range of words, phrases, chunks to communicate. Predominantly accurate production, however not always target-like/sophisticated. | Uses a wide range of words, phrases, chunks to communicate. There is a balanced production of target-like choice of words. Errors are due to attempts to produce more complex words or word combinations. |

|

Grammar

Diversity and sophistication |

Only uses short simple sentences. A lot of sentences are not target-like structures. | Predominantly uses one (simple) sentence. Grammar is not yet sufficiently sophisticated to convey the intended message correctly. | Can create correct grammatical sentences. Structures are still predominantly short and simple. Structures can be diverse but not always successful. | Mainly creates correct grammatical sentences. Length of sentences is not only short and there are some forms of coordination and subordination. | Creates correct grammatical sentences and has a balanced use of different sentence types (diverse). Grammatical errors are due to attempts at more complex AL structures. |

| Fluency | Speech rate is low with long pauses. Words, phrases or clauses are repeated without any modification. | Speech rate is low but there are few pauses and false starts. Is able to complete an utterance. Hesitations do occur frequently. | Speech rate varies but on average is high with few pauses or hesitations. Participant is mainly able to complete a sentence in one run. | Speech rate is high. Pauses and hesitations rarely occur. Participant sometimes reformulates what is said and adds new information when doing so. | A native speech rate. Rarely any pauses. Reformulations do occur but are a modification of what was said before. |

| Functional adequacy | Overall the task was unsuccessfully completed. Content scarcely conveys the intended message. | Task was almost successfully completed. Content sometimes met the expectations. The general message is starting to be comprehensible. | Task was overall successfully completed. Content sometimes didn’t meet the expectations. The general message is mainly comprehensible. | Task was successfully completed. Content met the expectations of the task and were comprehensible enough in the ears of a native speaker. | Task was very successfully completed. Content was relevant and met the expectations. Utterances are consistently comprehensible. |

Appendix C: Model output

Model output for IELTS speaking overall. *Notes significance, **notes not significant after subsetting.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.51 to 0.51 |

| Post-test | 0.20 | 0.17 | 1.18 | 0.246 | −0.15 to 0.55 |

| Retention test | 0.52 | 0.17 | 3.04 | 0.004* | 0.18–0.87 |

| Implicit | −0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.73 to 0.73 |

| Post-test * implicit | −0.14 | 0.24 | −0.58 | 0.567 | −0.64 to 0.35 |

| Retention test * implicit | −0.55 | 0.24 | −2.24 | 0.030** | −1.04 to −0.05 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.78 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.40 | ||||

| ICC | 0.77 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for IELTS speaking lexical resources. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.59 to 0.59 |

| Post-test | 0.41 | 0.26 | 1.80 | 0.079 | −0.05 to 0.86 |

| Retention test | 0.50 | 0.26 | 2.22 | 0.033* | 0.04–0.96 |

| Implicit | −0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.84 to 0.84 |

| Post-test * implicit | −0.31 | 0.32 | −0.98 | 0.334 | −0.96 to 0.33 |

| Retention test * implicit | −0.47 | 0.32 | −1.47 | 0.150 | −1.11 to 0.18 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.72 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.48 | ||||

| ICC | 0.70 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for IELTS speaking grammar. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.67 to 0.67 |

| Post-test | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.657 | −0.33 to 0.52 |

| Retention test | 0.44 | 0.21 | 2.10 | 0.043* | 0.01–0.86 |

| Implicit | −0.00 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.95 to 0.95 |

| Post-test * implicit | −0.28 | 0.30 | −0.95 | 0.349 | −0.88 to 0.32 |

| Retention test * implicit | −0.41 | 0.30 | −1.37 | 0.178 | −1.01 to 0.19 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.81 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.70 | ||||

| ICC | 0.80 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for IELTS speaking pronunciation. *Notes significance, **notes not significant after subsetting.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.59 to 0.59 |

| Post-test | −0.00 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.43 to 0.43 |

| Retention test | 0.59 | 0.22 | 2.82 | 0.007* | 0.17–1.02 |

| Implicit | −0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.83 to 0.83 |

| Post-test * implicit | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.60 to 0.60 |

| Retention test * implicit | −0.78 | 0.30 | −2.62 | 0.012** | −1.38 to −0.18 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.76 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.50 | ||||

| ICC | 0.74 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for IELTS speaking fluency. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.61 to 0.61 |

| Post-test | 0.38 | 0.25 | 1.51 | 0.140 | −0.13 to 0.88 |

| Retention test | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.534 | −0.35 to 0.66 |

| Implicit | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.87 to 0.87 |

| Post-test * implicit | −0.06 | 0.35 | −0.18 | 0.860 | −0.77 to 0.65 |

| Retention test * implicit | −0.41 | 0.35 | −1.15 | 0.256 | −1.12 to 0.31 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.68 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.49 | ||||

| ICC | 0.66 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for CEFR speaking overall. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.27 to 0.27 |

| Post-test | 0.32 | 0.12 | 2.71 | 0.010* | 0.08–0.56 |

| Retention test | 0.46 | 0.12 | 3.93 | <0.001* | 0.22–0.70 |

| Implicit | −0.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.38 to 0.38 |

| Post-test * implicit | −0.01 | 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.970 | −0.34 to 0.33 |

| Retention test * implicit | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.75 | 0.457 | −0.46 to 0.21 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.68 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.09 | ||||

| ICC | 0.61 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for Peabody. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 6.60 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −13.34 to 13.34 |

| Post-test | 12.75 | 5.42 | 2.35 | 0.024* | 1.79–23.71 |

| Retention test | 24.62 | 5.42 | 4.54 | <0.001* | 13.67–35.58 |

| Implicit | −0.00 | 9.34 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −18.87 to 18.87 |

| Post-test * implicit | 4.38 | 7.67 | 0.57 | 0.571 | −11.12 to 19.87 |

| Retention test * implicit | −9.62 | 7.67 | −1.26 | 0.217 | −25.12 to 5.87 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 117.57 | 0.19 | 0.73 | ||

| τ00 participant | 231.17 | ||||

| ICC | 0.66 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for IELTS listening. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.00 | 1.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −2.29 to 2.29 |

| Post-test | 0.00 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −2.81 to 2.81 |

| Retention test | 1.31 | 1.39 | 0.95 | 0.350 | −1.50 to 4.12 |

| Implicit | 0.00 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −3.24 to 3.24 |

| Post-test * implicit | 3.50 | 1.96 | 1.78 | 0.082 | −0.47 to 7.47 |

| Retention test * implicit | 1.62 | 1.96 | 0.83 | 0.413 | −2.35 to 5.60 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 7.72 | 0.17 | 0.38 | ||

| τ00 participant | 2.54 | ||||

| ICC | 0.25 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for English verbal fluency. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.00 | 2.74 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −5.53 to 5.53 |

| Post-test | 3.25 | 2.44 | 1.33 | 0.191 | −1.68 to 8.18 |

| Retention test | 7.75 | 2.44 | 3.17 | 0.003* | 2.82–12.68 |

| Implicit | 0.00 | 3.87 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −7.82 to 7.82 |

| Post-test * implicit | −5.13 | 3.45 | −1.48 | 0.146 | −12.10 to 1.85 |

| Retention test * implicit | −4.75 | 3.45 | −1.38 | 1.00 | −11.73 to 2.23 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 23.84 | 0.14 | 0.66 | ||

| τ00 participant | 36.08 | ||||

| ICC | 0.60 | ||||

| N participant | 16 | ||||

Model output for MATTR. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.68 | 0.02 | 34.69 | <0.001 | 0.64–0.72 |

| Time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.317 | −0.00 to 0.01 |

| Implicit | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.974 | −0.05 to 0.05 |

| Time * implicit | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.69 | 0.493 | −0.01 to 0.00 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.33 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.00 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.00 | ||||

| ICC | 0.32 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for coordinate phrases per T-unit. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.20 | 0.029 | 0.01–0.23 |

| Time | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.33 | 0.183 | −0.00 to 0.02 |

| Implicit | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.35 | 0.178 | −0.04 to 0.23 |

| Time * implicit | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.13 | 0.261 | −0.03 to 0.01 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.13 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.00 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.00 | ||||

| ICC | 0.12 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for lexical errors. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 4.44 | <0.001 | 0.02–0.04 |

| Time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.483 | −0.00 to 0.00 |

| Implicit | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.76 | 0.446 | −0.01 to 0.03 |

| Time * implicit | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.43 | 0.667 | −0.00 to 0.00 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | ||

| τ00 participant | 0.00 | ||||

| ICC | 0.00 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

Model output for structural errors. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.08 | 0.002 | 0.01–0.04 |

| Time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.964 | −0.00 to 0.00 |

| Implicit | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.80 | 0.006* | 0.01–0.04 |

| Time * implicit | −0.00 | 0.00 | −2.92 | 0.004* | −0.00 to −0.00 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.41 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.00 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.00 | ||||

| ICC | 0.36 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for number of words per minute. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 136.57 | 7.57 | 18.03 | <0.001 | 121.63–151.51 |

| Time | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.867 | −1.31 to 1.56 |

| Implicit | 6.51 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.486 | −11.86 to 24.87 |

| Time * implicit | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.384 | −0.79 to 2.05 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 278.26 | 0.06 | 0.52 | ||

| τ00 task | 78.89 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 187.15 | ||||

| ICC | 0.49 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for number of silent pauses per minute. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 22.31 | 1.52 | 14.65 | <0.001 | 19.30–25.31 |

| Time | −0.17 | 0.12 | −1.38 | 0.168 | −0.42 to 0.07 |

| Implicit | −1.76 | 2.22 | −0.80 | 0.427 | −6.14 to 2.61 |

| Time * implicit | −0.05 | 0.18 | −0.26 | 0.793 | −0.40 to 0.31 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 17.50 | 0.05 | 0.41 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.22 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 10.15 | ||||

| ICC | 0.37 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for mean length of silent pause. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.20 | 0.02 | 34.70 | <0.001 | 0.96–1.44 |

| Time | −0.01 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.226 | −0.03 to 0.01 |

| Implicit | −0.21 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.237 | −0.55 to 0.14 |

| Time * implicit | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.69 | 0.312 | −0.01 to 0.04 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.47 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.00 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.07 | ||||

| ICC | 0.45 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for number of filled pauses per minute. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 4.08 | 1.64 | 2.50 | 0.013 | 0.86–7.31 |

| Time | 0.22 | 0.01 | 1.67 | 0.098 | −0.04 to 0.48 |

| Implicit | −2.21 | 2.30 | −0.96 | 0.339 | −6.75 to 2.33 |

| Time * implicit | −0.13 | 0.17 | −0.75 | 0.456 | −0.47 to 0.21 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 15.87 | 0.08 | 0.50 | ||

| τ00 task | 1.03 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 11.87 | ||||

| ICC | 0.45 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for number of repairs/repetitions per minute. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.30 | 1.11 | 2.07 | 0.040 | 0.11–4.49 |

| Time | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.451 | −0.10 to 0.23 |

| Implicit | −0.29 | −0.19 | −0.19 | 0.853 | −3.41 to 2.82 |

| Time * implicit | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.996 | −0.21 to 0.22 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 6.46 | 0.01 | 0.50 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.37 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 5.93 | ||||

| ICC | 0.49 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for speech rate. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.40 | 0.16 | 14.62 | <0.001 | 2.07–2.72 |

| Time | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.78 | 0.006* | 0.01–0.05 |

| Implicit | 0.29 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.210 | −0.16 to 0.75 |

| Time * implicit | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.970 | −0.02 to 0.02 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.72 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.01 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.15 | ||||

| ICC | 0.68 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for holistic grammar scores. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.69 | 0.20 | 13.22 | <0.001 | 2.29–3.09 |

| Time | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.29 | 0.023* | 0.01–0.08 |

| Implicit | −0.14 | 0.28 | −0.50 | 0.619 | −0.69 to 0.41 |

| Time * implicit | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 0.583 | −0.03 to 0.06 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.44 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.02 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.17 | ||||

| ICC | 0.41 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for holistic vocabulary scores. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.97 | 0.19 | 15.93 | <0.001 | 2.60–3.34 |

| Time | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.54 | 0.126 | −0.01 to 0.06 |

| Implicit | −0.33 | 0.26 | −1.27 | 0.206 | −0.84 to 0.18 |

| Time * implicit | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.68 | 0.095 | −0.01 to 0.08 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.40 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.02 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.13 | ||||

| ICC | 0.36 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for holistic fluency scores. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.95 | 0.21 | 13.95 | <0.001 | 2.53–3.37 |

| Time | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.37 | 0.174 | −0.01 to 0.06 |

| Implicit | −0.10 | 0.31 | −0.32 | 0.750 | −0.69 to 0.50 |

| Time * implicit | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.766 | −0.04 to 0.05 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.45 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.01 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.20 | ||||

| ICC | 0.44 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

Model output for holistic functional adequacy scores. *Notes significance.

| Predictors | b | SE | t | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.60 | 0.22 | 16.42 | <0.001 | 3.17–4.04 |

| Time | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.37 | 0.715 | −0.05 to 0.04 |

| Implicit | −0.40 | 0.28 | −1.45 | 0.149 | −0.94 to 0.14 |

| Time * implicit | 0.05 | 0.02 | 1.89 | 0.060 | −0.00 to 0.09 |

|

|

|||||

| Random effects | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| σ2 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.40 | ||

| τ00 task | 0.06 | ||||

| τ00 participant | 0.14 | ||||

| ICC | 0.39 | ||||

| N participant | 13 | ||||

| N task | 22 | ||||

References

Andringa, Sible & Patrick Rebuschat. 2015. New directions in the study of implicit and explicit learning: An introduction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 37(2). 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/s027226311500008x.Search in Google Scholar

Bak, Thomas H., Madeleine R. Long, Mariana Vega-Mendoza & Antonella Sorace. 2016. Novelty, challenge, and practice: The impact of intensive language learning on attentional functions. PLoS One 11(4). e0153485. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153485.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Blumenfeld, Henrike K., Sim J. Quinzon, Cindy Alsol & Stephanie A. Riera. 2017. Predictors of successful learning in multilingual older adults acquiring a majority language. Frontiers in Communication 2. 23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2017.00023.Search in Google Scholar

Bubbico, Giovanna, Piero Chiacchiaretta, Matteo Parenti, Marcin di Marco, Valentina Panara, Gianna Sepede, Antonio Ferretti & Mauro G. Perrucci. 2019. Effects of second language learning on the plastic aging brain: Functional connectivity, cognitive decline, and reorganization. Frontiers in Neuroscience 13. 423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00423.Search in Google Scholar

Cherry, Katie E. & Michael E. Stadler. 1995. Implicit learning of a nonverbal sequence in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging 10(3). 379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.10.3.379.Search in Google Scholar

Christensen, Helen. 2001. What cognitive changes can be expected with normal ageing? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 35(6). 768–775. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00966.x.Search in Google Scholar

Christopher, Gary. 2013. The psychology of ageing: From mind to society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Covington, Michael A. & Joe D. McFall. 2010. Cutting the Gordian knot: The moving-average type–token ratio (MATTR). Journal of quantitative linguistics 17(2). 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296171003643098.Search in Google Scholar

Cox, Jessica G. & Cristina Sanz. 2015. Deconstructing PI for the ages: Explicit instruction vs. practice in young and older adult bilinguals. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 53(2). 225–248.10.1515/iral-2015-0011Search in Google Scholar

De Jong, Nivja H. & Ton Wempe. 2009. Praat script to detect syllable nuclei and measure speech rate automatically. Behavior Research Methods 41(2). 385–390. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.2.385.Search in Google Scholar

DeKeyser, Robert M. 2013. Age effects in second language learning: Stepping stones toward better understanding. Language Learning 63. 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00737.x.Search in Google Scholar

Dunn, Lloyd M. & Douglas M. Dunn. 2007. PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test. New York: Pearson Assessments.10.1037/t15144-000Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick. 1994. Introduction: Implicit and explicit language learning—an overview. In Nick Ellis (ed.), Implicit and explicit learning of languages, 79–114. London: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Garrod, Simon & Martin J. Pickering. 2004. Why is conversation so easy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 8(1). 8–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.016.Search in Google Scholar

Gombert, Wim. 2023. Explicit versus implicit instruction and accuracy in writing: A longitudinal study. University of Groningen Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Goo, Jaemyung, Gisela Granena, Yucel Yilmaz & Miguel Novella. 2015. Implicit and explicit instruction in L2 learning: Norris & Ortega (2000) revisited and updated. In Patrick Rebuschat (ed.), Implicit and explicit learning of languages, 443–482. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/sibil.48.18gooSearch in Google Scholar

Grotek, Monika. 2018. Student needs and expectations concerning foreign language teachers in the universities of the third age. In Danuta Gabryś-Barker (ed.), Third age learners of foreign languages, 129–145. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783099412-010Search in Google Scholar

Gruneberg, Michael M. & Kate Pascoe. 1996. The effectiveness of the keyword method for receptive and productive foreign vocabulary learning in the elderly. Contemporary Educational Psychology 21(1). 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1996.0009.Search in Google Scholar

Howard, James H. & Darlene V. Howard. 1997. Age differences in implicit learning of higher order dependencies in serial patterns. Psychology and Aging 12(4). 634. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.12.4.634.Search in Google Scholar