Abstract

Objectives

Adolescent knowledge about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in Indonesia is low and moderate. This study aims to determine the influence of peer mentorship on improving adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes about SRH.

Methods

This study uses a quasi-experimental pre- and post-test with a control group design. The population is adolescents in high school, aged 15–19. Eight students were selected as volunteers to be trained by professionals as mentors. The sample was selected using a proportional random sampling technique, with 91 students in each group. Peer mentoring was carried out for three months with 12 meetings. A questionnaire measured knowledge and attitudes before and after the intervention.

Results

The majority of respondents were women (57.1 %) and men (42.9 %), with the most common age being 17 years old (29.7 %). There was no difference between the characteristics of the respondents and the variables studied. Respondents’ knowledge level increased in the high category after the intervention from 67 to 95.6 %; positive attitudes increased from 48.4 to 51.6 %.

Conclusions

Peer mentoring interventions significantly influenced respondents’ knowledge. The peer mentoring approach effectively increases adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes. It is recommended that this assistance become a school program.

Introduction

One of the Sustainable Development Goals is to address health issues, including human reproductive health. The scope of reproductive health includes reproductive rights, easy access to health services, access to appropriate information, and freedom from sexual harassment [1], 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being related to sexuality, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity [3]. Each country has ways and strategies to improve its health status [4], 5].

Adolescents are individuals who are in a transition period from children to adults. Many changes occur in adolescence [6]. Physical changes can be seen at the beginning of adolescence, namely during puberty, such as rapid weight and height growth, significant changes in body composition, increased muscle mass, and fat distribution [7]. Increased oil production in the body causes adolescents to tend to acne. Development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics, such as breast development in girls and testicular enlargement in boys, occurs during this period [8]. Adolescent brain development has developed; they begin to analyze and think abstractly [9]. Psychological changes occur in adolescents, namely erratic mood [10]. Adolescents are also often easily influenced by their social environment, and curiosity leads them to follow the environment [11]. Therefore, peer influence for adolescents has an essential role in determining decision-making.

Based on data from various countries, the level of adolescent awareness about sexual and reproductive health is still relatively low. In Benin City, Nigeria, only 19.1 % of adolescents have a good level of knowledge about sexual and reproductive health [12]. Adolescents also show low awareness of pregnancy and abortion laws in Malaysia [12]. In Indonesia, the majority of adolescents have low to moderate knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health [13]. Likewise, the last study in 2022 found that the level of knowledge of adolescents in Batam City, Indonesia, is still mostly moderate [14].

Positive attitudes and perceptions of individuals will guide individuals in making positive decisions to act. Based on the KAP model, the level of knowledge is in line with attitudes and actions [15], 16]. But in reality, not all individuals with good knowledge have a positive attitude [17], 18]. This case is often found in the discussion of sensitive themes among adolescents, including sexual and reproductive health. Various factors affect adolescents in determining attitudes, such as the existence of norms and cultures that bind adolescents [19]. Therefore, adolescents need an environment that supports their decisions and allows them to share information they have previously considered taboo comfortably.

The peer approach is felt necessary to increase adolescent knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health [20]. With a mentor trained among them, they will become facilitators for adolescents in sharing experiences and information that they consider taboo. The peer environment makes adolescents feel comfortable, so later, they can direct adolescents in decision-making to develop a positive attitude. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of peer mentoring interventions in improving adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes towards sexual and reproductive health.

Methods

Study design

This study is a quasi-experimental quantitative research pre-test and post-test using a control group [21].

Sample

After obtaining permission from the principal to conduct research, the researcher collaborated with the teacher of the student affairs department to set the schedule for implementing mentors at the school. The population in this study consisted of 910 students, divided across three different grades: grade X (350 students), grade XI (200 students), and grade XII (360 students). Samples are determined using probability sampling. This proportional graded random sampling ensures that each grade is adequately represented in the sample. The sample size for each grade is based on a fixed sampling ratio of 20 % of the grade population. Thus, the number of participants selected from each grade reflects their proportional share of the overall population. In each grade, samples were randomly selected using the lottery method to ensure randomness and minimize bias, resulting in a sample of 182 students. The sample was then divided into two groups, each comprising 91 respondents: the control group and the intervention group. Mentors are students who are selected and willing to become mentors and are members of the Intra-School Student Organization (OSIS). Previously, mentors received training on the role and responsibilities of a mentor, effective peer communication techniques, and comprehensive SRH education tailored for adolescents, provided by professionals in the field of community nursing and trainers, over three days. Respondents selected based on the inclusion criteria are students who are actively involved in the school’s extracurricular activities and have expressed their willingness to participate by completing an approval form. The exclusion criteria are students who are to serve as peer mentors.

Instrument

To measure the effectiveness of the intervention, the researcher conducted two evaluations, namely a pre-test and a post-test. The questionnaire was adopted from a previous researcher and has been obtained with permission [22], then modified to adapt to the local language. The questionnaire that has been tested for validity and reliability has a total of 20 items for the level of knowledge, which includes sexual identity, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, sexual activity, and contraception. The 20 attitude items include early sexual intercourse, gender identity, risk of early sexual activity, sources of reproductive health information, and attitudes toward the prevention of sexually transmitted infections.

Intervention

The intervention included a structured peer mentoring program focused on adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Before implementation, eight student OSIS members were deliberately selected as peer mentors based on their leadership potential and communication skills. These students received three days of mentor training. To ensure the quality and consistency of the training, the curriculum was adapted from the national SRH peer education guidelines, and all trainers possess valid certifications in SRH education and youth mentoring. The mentor’s competency is assessed at the end of the training through role-playing evaluations and knowledge assessments to ensure alignment with national peer education standards.

After the training is complete, peer mentors conduct weekly mentoring sessions with students in 12-week intervention groups. Each session lasts 60 min and follows a pre-designed mentoring manual. The manual includes interactive activities, group discussions, and scenario-based learning focused on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) topics. Researchers, school nurses, and student assistant teachers regularly supervise the sessions to ensure adherence to the content and quality of mentoring. The control group received no intervention during this period.

Data collection

Baseline data were collected from both the control group and the intervention group using a pre-test online questionnaire distributed through Google Forms. Student assistant teachers helped with distributing this questionnaire. Following the 3-month intervention, a posttest questionnaire was administered to assess the changes in adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes related to SRH.

Data analysis

Frequency distribution analysis was carried out for the collected data. Subsequently, the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was carried out to determine the difference in characteristics with variables, and the Wilcoxon test was carried out to determine the intervention’s influence on the respondent’s level of knowledge and attitude. This data analysis uses SPSS software version 25.

Ethical consideration

Research ethics considerations are carried out as a form of researcher responsibility to morally justify participants. Society faces ethical responsibility as a whole. The research was carried out by the Helsinki Declaration, and the ethics permit was given by the Health Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Andalas University, No. 359. layaketik/KEPKFKEPUNAND.

Results

The distribution of knowledge levels of pre-test and post-test respondents can be seen from the table above. The results of the pre-test in the intervention group showed that the majority of respondents had a high level of knowledge, namely 61 respondents (67 %), followed by the moderate category of 29 respondents (31.9 %) and only one respondent (1.1 %) with a low level of knowledge before the intervention. Likewise, the control group initially dominated with a high level of knowledge of 17 respondents (78 %). Meanwhile, after being given the intervention, there were no more respondents with a low level of knowledge (0 %). Respondents with a high level of knowledge were 87 people (95.6 %).

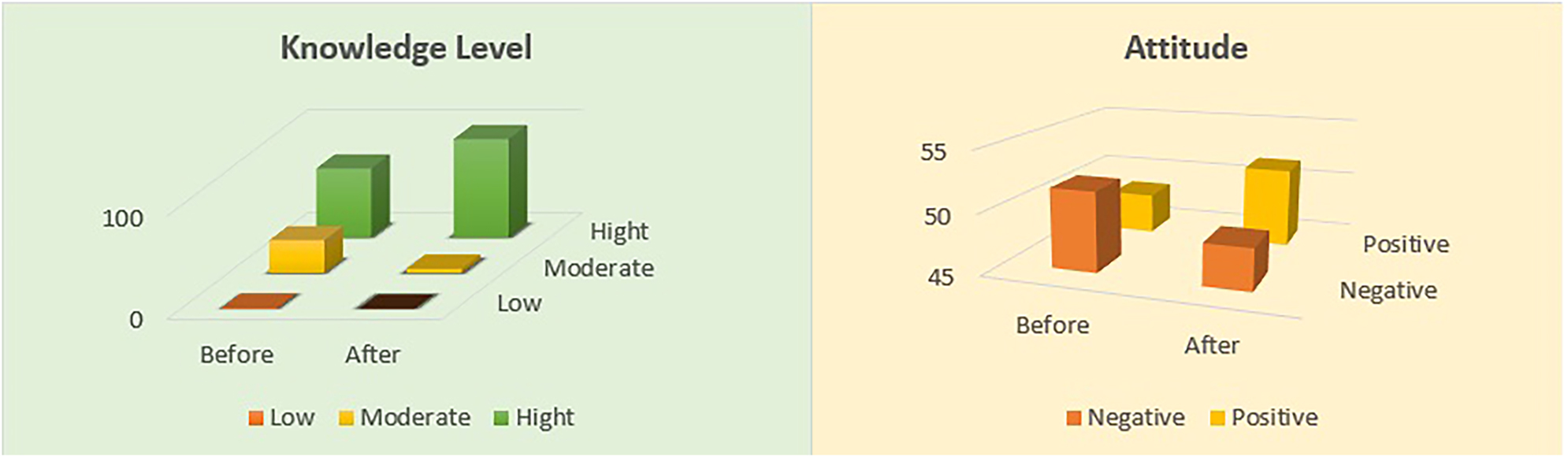

Table 1 above shows the distribution of attitudes of pre-test and post-test respondents. The assessment of respondents’ attitudes was grouped into positive and negative. It can be seen that in the pre-test, the number of respondents had a negative attitude of 47 (51.6 %). This figure is more than that of respondents with a positive attitude, which is 44 (48.4 %). It is different when respondents are given interventions. The number of positive attitudes shifted slightly to 47 (51.6). Meanwhile, in the control group, the positive attitude of respondents decreased from 54 (59.3 %) to 50 (54.9 %). Figure 1 also briefly shows the changes before and after the intervention.

Knowledge level and attitude before and after intervention.

| Variable | Intervention | Control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge level | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Low | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate | 29 | 31.9 | 4 | 4.4 | 19 | 20.9 | 15 | 16.5 |

| Hight | 61 | 67 | 87 | 95.6 | 71 | 78 | 76 | 83.5 |

| Total | 91 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 91 | 100 |

|

|

||||||||

| Attitude | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Negative | 47 | 51.6 | 44 | 48.4 | 37 | 40.7 | 41 | 45.1 |

| Positive | 44 | 48.4 | 47 | 51.6 | 54 | 59.3 | 50 | 54.9 |

| Total | 91 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 91 | 100 |

Level of knowledge and attitude before and after intervention.

Table 2 above shows that most of the respondents are women, with a total of 52 people (57.1 %). Meanwhile, 39 respondents were male (42.9 %). When viewed based on age distribution, 18-year-old respondents seem to dominate the number of respondents, as many as 27 respondents (29.7 %). The youngest student was 15 years old, with only 14 respondents (15.4 %), while only one student was 19 years old. In the control group, the majority of women were 49 (53.8 %), with the majority aged 16 and 17 years.

Differences between knowledge level and attitude by characteristics of respondents.

| Characteristic | n | % | Knowledge level | Attitude | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |||||||

| Mean rank | p-Value | Mean rank | p-Value | Mean rank | p-Value | Mean rank | p-Value | |||

| Intervention | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Gender | 0.214 | 0.080 | 0.104 | 0.751 | ||||||

| Male | 39 | 42.9 | 42.59 | 49.50 | 41.50 | 45.17 | ||||

| Female | 52 | 57.1 | 48.56 | 43.38 | 49.38 | 46.63 | ||||

| Total | 91 | 100 | ||||||||

| Age, Year | 0.155 | 0.355 | 0.171 | 0.378 | ||||||

| 15 | 14 | 15.4 | 32.86 | 53.00 | 50.00 | 48.50 | ||||

| 16 | 25 | 27.5 | 48.80 | 45.72 | 40.38 | 46.94 | ||||

| 17 | 24 | 26.4 | 45.46 | 41.63 | 41.06 | 38.75 | ||||

| 18 | 27 | 29.7 | 50.00 | 46.26 | 52.65 | 49.70 | ||||

| 19 | 1 | 1.1 | 65.0 | 53.00 | 69.50 | 61.50 | ||||

| Total | 91 | 100 | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Control | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Gender | 0.346 | 0.242 | 0.694 | 0.698 | ||||||

| Male | 42 | 46.2 | 43.98 | 43.75 | 47.00 | 45.00 | ||||

| Female | 49 | 53.8 | 47.73 | 47.93 | 45.14 | 46.86 | ||||

| Total | 91 | 100 | ||||||||

| Age, Year | 0.823 | 0.905 | 0.745 | 0.089 | ||||||

| 15 | 14 | 15.4 | 46.36 | 43.75 | 43.75 | 54.75 | ||||

| 16 | 26 | 28.6 | 49.08 | 48.35 | 45.00 | 51.75 | ||||

| 17 | 26 | 28.6 | 43.50 | 44,75 | 45.00 | 37.75 | ||||

| 18 | 24 | 26.4 | 44.75 | 45.92 | 48.35 | 44.46 | ||||

| 19 | 1 | 1.1 | 56.00 | 53.50 | 73.00 | 25.50 | ||||

| Total | 91 | 100 | ||||||||

Table 2 also shows the difference in the characteristics of respondents and their level of knowledge and attitudes. None of the respondents’ characteristics (gender and age) had significant differences in knowledge level or attitude. This means that the intervention provided is carried out comprehensively and does not have to be separated by gender or age range of respondents in high school.

Based on Table 3 above, it can be seen that respondents have been able to significantly increase their knowledge after the intervention about knowledge of sexuality, development of sexual organs, risks of premarital sex, the impact of drug use, effects of early pregnancy, and understanding of pregnancy. Respondents also had a positive attitude about sexual behaviour before marriage and a positive attitude towards the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases, and respondents believed that they were accepted when adolescents were pregnant at a young age.

Effect of the intervention on respondents’ level of knowledge and attitudes based on respondents’ answers.

| No | Question topics | Intervention (mean ± SD) | Control (mean ± SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | p-Value | Pre-test | Post-test | p-Value | ||

| Knowledge | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| 1 | Definition of reproductive health | 0.82 ± 0.383 | 0.901 ± 0.300 | 0.127 | 0.87 ± 0.340 | 0.868 ± 0.340 | 1.000 |

| 2 | Definition of sexuality | 0.56 ± 0.499 | 0.835 ± 0.373 | 0.000* | 0.68 ± 0.469 | 0.681 ± 0.468 | 1.000 |

| 3 | Correct statements about sexuality | 0.67 ± 0.473 | 0.797 ± 0.403 | 0.048* | 0.56 ± 0.499 | 0.791 ± 0.408 | 0.000* |

| 4 | Signs of sexual development during adolescence | 0.90 ± 0.302 | 0.989 ± 0.104 | 0.011* | 0.91 ± 0.285 | 0.923 ± 0.267 | 0.705 |

| 5 | Risks of premarital sex | 0.95 ± 0.229 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.025* | 0.98 ± 0.147 | 0.978 ± 0.147 | 1.000 |

| 6 | Examples of premarital sex | 0.86 ± 0.352 | 0.923 ± 0.267 | 0.134 | 0.82 ± 0.383 | 0.846 ± 0.362 | 0.637 |

| 7 | Factors influencing sexual development | 0.84 ± 0.373 | 0.945 ± 0.299 | 0.012* | 0.84 ± 0.373 | 0.868 ± 0.340 | 0.491 |

| 8 | Examples of gender stereotypes | 0.43 ± 0.498 | 0.516 ± 0.502 | 0.131 | 0.42 ± 0.496 | 0.494 ± 0.502 | 0.237 |

| 9 | Importance of sex education for adolescents | 0.69 ± 0.464 | 0.780 ± 0.416 | 0.102 | 0.73 ± 0.445 | 0.733 ± 0.444 | 1.000 |

| 10 | Ways to maintain healthy sexuality | 0.70 ± 0.459 | 0.879 ± 0.327 | 0.002* | 0.78 ± 0.416 | 0.791 ± 0.408 | 0.841 |

| 11 | Negative impacts of drug abuse on adolescents | 0.93 ± 0.250 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.014* | 0.96 ± 0.206 | 0.978 ± 0.147 | 0.317 |

| 12 | Transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) | 0.91 ± 0.285 | 0.945 ± 0.229 | 0.405 | 0.89 ± 0.314 | 0.890 ± 0.314 | 1.000 |

| 13 | Sources of sexually transmitted diseases | 0.90 ± 0.300 | 0.945 ± 0.229 | 0.206 | 0.92 ± 0.268 | 0.912 ± 0.284 | 0.763 |

| 14 | Main goals of the family planning (FP) program | 0.87 ± 0.340 | 0.923 ± 0.267 | 0.197 | 0.76 ± 0.434 | 0.955 ± 0.207 | 0.033* |

| 15 | Risks of having multiple sexual partners | 0.97 ± 0.180 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.97 ± 0.180 | 0.989 ± 0.104 | 0.317 |

| 16 | Factors that increase the risk of reproductive diseases | 0.93 ± 250 | 0.989 ± 0.104 | 0.059 | 0.96 ± 0.206 | 0.956 ± 0.206 | 1.000 |

| 17 | Complications of early pregnancy | 0.80 ± 401 | 0.978 ± 0.147 | 0.000* | 0.84 ± 0.373 | 0.846 ± 0.362 | 0.808 |

| 18 | Signs of puberty in adolescents | 0.95 ± 0.229 | 0.978 ± 0.147 | 0.257 | 0.95 ± 0.229 | 0.945 ± 0.229 | 1.000 |

| 19 | Effective methods to prevent pregnancy | 0.95 ± 0.229 | 0.989 ± 0.104 | 0.102 | 0.96 ± 0.206 | 0.967 ± 0.179 | 0.180 |

| 20 | Correct statements about pregnancy | 0.89 ± 0.314 | 0.989 ± 0.104 | 0.007* | 0.91 ± 0.285 | 0.912 ± 0.284 | 1.000 |

|

|

|||||||

| Attitude | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| 1 | When a person reaches puberty, they have the desire to engage in sexual activities with their partner | 2.24 ± 0.807 | 2.362 ± 0.767 | 0.232 | 2.26 ± 0.854 | 2.329 ± 0.817 | 0.733 |

| 2 | Adolescents are usually attracted to the same sex | 3.48 ± 0.736 | 3.593 ± 0.682 | 0.189 | 3.47 ± 0.869 | 3.450 ± 0.687 | 0.938 |

| 3 | Adolescents who engage in early sexual activity may regret it later due to the consequences | 3.51 ± 0.705 | 3.604 ± 0.681 | 0.286 | 3.56 ± 0.618 | 3.593 ± 0.557 | 0.665 |

| 4 | Adolescents who engage in premarital sex are at risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases | 3.14 ± 0.676 | 3.351 ± 0.545 | 0.013* | 3.24 ± 0.656 | 3.285 ± 0.601 | 0.693 |

| 5 | When an adolescent is under the influence of alcohol, it increases their desire to have sex | 2.93 ± 0.696 | 3.153 ± 0.575 | 0.017* | 3.04 ± 0.665 | 3.054 ± 0.638 | 0.896 |

| 6 | Adolescents’ sexual behaviour is influenced by their peers/friends | 3.01 ± 0.691 | 3.274 ± 0.650 | 0.004* | 3.00 ± 0.699 | 0.033 ± 0.690 | 0.616 |

| 7 | It is best to listen to parents’ advice to avoid sexual and social risks such as premarital sex, alcohol, and drugs | 3.63 ± 0.661 | 3.857 ± 0.351 | 0.002* | 3.68 ± 0.594 | 3.725 ± 0.472 | 0.499 |

| 8 | When an adolescent boy and girl love each other, they are free to engage in sexual activities | 3.38 ± 0.721 | 3.549 ± 0.637 | 0.513 | 1.54 ± 0.620 | 1.549 ± 0.619 | 0.927 |

| 9 | Women can have sex with their male partners one week after menstruation | 2.63 ± 0.812 | 2.879 ± 0.786 | 0.020* | 2.29 ± 0.735 | 2.340 ± 0.686 | 0.524 |

| 10 | Adolescents should not engage in sexual activities until they are married | 3.38 ± 0.866 | 3.648 ± 0.584 | 0.008* | 3.41 ± 0.699 | 3.450 ± 0.671 | 0.700 |

| 11 | Sexually transmitted diseases/pregnancy can be prevented when condoms are used during sexual activities | 2,79 ± 0.723 | 3.033 ± 0.585 | 0.013* | 2.79 ± 0.691 | 2.780 ± 0.628 | 0.969 |

| 12 | Abstaining from sex is the best prevention for sexually transmitted diseases | 3.18 ± 0.693 | 3.417 ± 0.578 | 0.011* | 3.18 ± 0.676 | 3.186 ± 0.648 | 0.810 |

| 13 | Knowing reproductive health issues prepares an adolescent to become a responsible individual in society | 3.36 ± 0.707 | 3.571 ± 0.540 | 0.022* | 3.31 ± 0.726 | 3.362 ± 0.623 | 0.514 |

| 14 | Physical and physiological changes in an adolescent’s body serve as a signal that they are now ready for sexual activity | 2.45 ± 0.764 | 2.714 ± 0.719 | 0.007* | 2.43 ± 0.747 | 2.439 ± 0.670 | 0.844 |

| 15 | Unwanted pregnancy can result in abortion | 3.13 ± 0.748 | 3.318 ± 0.728 | 0.077 | 3.12 ± 0.728 | 3.153 ± 0.681 | 0.704 |

| 16 | Not engaging in sexual activities is the best method to avoid pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases | 3.49 ± 0.639 | 3.604 ± 0.612 | 0.223 | 3.36 ± 0.691 | 3.406 ± 0.576 | 0.321 |

| 17 | It is always a woman’s responsibility to ensure contraceptive methods are used before engaging in sexual activities with a partner | 2.24 ± 0.689 | 2.483 ± 0.750 | 0.022* | 2.65 ± 0.822 | 2.505 ± 0.794 | 0.192 |

| 18 | Sexually transmitted diseases can be transmitted through kissing and touching a partner’s genital area | 2.73 ± 0.668 | 3.175 ± 0.569 | 0.000* | 2.90 ± 0.684 | 2.846 ± 0.665 | 0.000* |

| 19 | Drinking alcohol will harm reproductive health | 3.24 ± 0.720 | 3.560 ± 0.541 | 0.001* | 3.29 ± 0.637 | 3.340 ± 0.581 | 0.428 |

| 20 | All sexual acts should be free from coercion and disease | 2.93 ± 0.854 | 3.252 ± 0.901 | 0.012* | 2.89 ± 0.900 | 2.934 ± 0.879 | 0.729 |

-

*p-Value < 0.05.

Discussion

Based on the findings of the study, the majority of respondents are women. However, it is important to note that both male and female students participated in this study. The data shows female students’ high participation and interest in mentoring activities at school. These results show that female students are more interested in mentoring activities than male students [23], 24]. In addition, the number of female participants is also higher, making women more involved in mentoring activities. The older the respondent, the higher the academic score, so it is possible that at the time of the mentoring activities, 19-year-old students in the highest grade have a lot of time to study to prepare for the graduation exam.

In countries such as Malaysia and the United States, it has also been shown that the female population exceeds the male population [25]. These results are in line with previous findings that female students prefer to be actively involved in school activities that involve discussion and organization than male students [26]. Meanwhile, male students are more likely to be interested in physical school activities [27]. In addition, the number of female students at the study site is also higher than that of males, so their chances of being involved in activities are also higher.

Students are seen to already have a good level of knowledge at the beginning before being given an intervention. Nowadays, exposure to information is easy to obtain [28], 29]. Adolescents can freely access information online to find the information they are looking [30], 31]. When compared to 2022, internet usage among adolescents has risen significantly, providing them with greater potential to independently access information. However, previous findings indicate that most adolescents in Batam still possess a moderate level of knowledge regarding sexual and reproductive health. This suggests that while access to information has improved, the depth and accuracy of understanding remain limited, highlighting the necessity for structured and sustained interventions. Respondents’ knowledge and attitude after being given the intervention were seen to increase. The data prove that the mentoring interventions provided positively impact students. During mentoring, students share information based on their experiences. In addition, they can comfortably discuss the sensitive topics they discuss because the bond between group members is constantly established during the mentoring group interaction. In addition, the mentoring process also fosters confidence and motivation in adolescents [32]. This mutual trust and the development of social and emotional bonds make respondents feel comfortable in determining their attitudes in a positive direction [33]. This also means that communication support and social environment can increase adolescents’ resilience [34]. Through peer mentoring, adolescents have a supportive environment for decision-making [35]. Mentors have proven to carry out their role as companions who can persuade respondents to adopt positive attitudes.

Gender and age characteristics did not differ in respondents’ knowledge and attitudes. In one mentoring group, students are combined between men and women. They get the exact source of information and share it. This activity allows their knowledge and attitudes to be almost the same. This contrasts with previously conducted findings, which show mixed results. There are differences in adolescents’ knowledge about contraception [36]. Other findings found differences in adolescent boys’ and girls’ knowledge and attitudes regarding the impact of social media on their health [37]. These results also align with research on respondents aged 18–49 years.

There was no difference between the two groups based on the age of the respondents [38]. This is also in line with a study at athletic universities that found that there was no gender difference in respondents’ knowledge and attitudes [39]. The characteristics of sex and age were not significantly different; It could be due to exposure to information obtained from online sources that can be accessed easily. However, not all information obtained can be validated for its truth [40]. Adolescents need assistance and get information from trusted sources so they do not become misunderstood [41].

These findings align with the Knowledge, Attitude, Practice model, indicating that an individual’s knowledge influences their attitudes, ultimately leading to practice. In Sidoarjo, Indonesia, adolescents who had good knowledge about pregnancy prevention were also accompanied by positive attitudes [42]. Although findings suggested no direct link between adolescents’ knowledge and practices regarding safe sex behaviours, improving sexual attitudes was essential to promote safe sex practices among adolescents [43].

This study’s limitation is that it has not been able to reach all students in the school. Thus, not all students can experience the benefits of peer mentoring directly.

Conclusion and recommendation

It can be concluded that, overall, respondents’ knowledge level increased after being given a peer-to-peer approach intervention. Similarly, the respondents’ attitudes shifted in a positive direction after being given the intervention. There was no difference in the results of knowledge level and attitude based on the gender and age of the respondents. This means that education about reproductive sexual health can be carried out simultaneously or comprehensively to all students in high school without having to separate respondents based on gender or age. The implications of these findings suggest that the peer approach is more appropriate for adolescents to change knowledge and attitudes, especially on the theme of sexual and reproductive health. It is hoped that other schools in Batam City can apply the peer approach method in educating adolescents. In addition, researchers can then conduct research using similar methods with a broader scope. By approaching the school, it is hoped that this program can be included in the school program of the student affairs section.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the principal of SMAN 14 Batam for the support and facilities provided. Thank you to the accompanying teacher who assisted in the administration and scheduling for 3 months, and to all students involved in this research.

-

Research ethics: Research ethics considerations are carried out as a form of researcher responsibility to morally justify participants. Society faces ethical responsibility as a whole. The research was carried out under the Helsinki Declaration, and the ethics permit was given by the Health Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Andalas University, No. 359. layaketik/KEPKFKEPUNAND.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this paper.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Paulman, PM, Taylor, RB, Paulman, AA, Nasir, LS. Family medicine: principles and practice: eighth edition. Fam Med Princ Pract 2022:1–1977. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54441-6.8th ed.Search in Google Scholar

2. Monfort-Portet, S. Prevention – education – health promotion: the place of the physiotherapists in taking into account the role of sexuality in health. Kinésithér 2021;21:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kine.2020.11.006.Search in Google Scholar

3. Power, J. Hiv, stis, risk taking and sexual health. Routledge Int Handb Women’s Sex Reprod Heal. 2019:455–67. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351035620-31.Search in Google Scholar

4. Ouedraogo, L, Habonimana, D, Nkurunziza, T, Chilanga, A, Hayfa, E, Fatim, T, et al.. Towards achieving the family planning targets in the African region: a rapid review of task sharing policies. Reprod Health 2021;18:12978. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-01038-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Meherali, S, Rehmani, M, Ali, S, Lassi, ZS. Interventions and strategies to improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes among adolescents living in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adolesc 2021;1:363–90. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030028.Search in Google Scholar

6. Pfeifer, JH, Allen, NB. Puberty initiates cascading relationships between neurodevelopmental, social, and internalizing processes across adolescence. Biol Psychiatry 2021;89:99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Desbrow, B. Youth athlete development and nutrition. Sports Med 2021;51:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01534-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Dehestani, N, Vijayakumar, N, Ball, G, Mansour L, S, Whittle, S, Silk, TJ. Puberty age gap’: new method of assessing pubertal timing and its association with mental health problems. Mol Psychiatr 2024;29:221–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02316-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Andrews, JL, Ahmed, SP, Blakemore, SJ. Navigating the social environment in adolescence: the role of social brain development. Biol Psychiatry 2021;89:109–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Thomson, K, Magee, C, Gagné Petteni, M, Oberle, E, Georgiades, K, Schonert‐Reichl, K, et al.. Changes in peer belonging, school climate, and the emotional health of immigrant, refugee, and non-immigrant early adolescents. J Adolesc 2024:12390. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12390.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Wong, MD, Quartz, KH, Saunders, M, Meza, BP, Childress, S, Seeman, TE, et al.. Turning vicious cycles into virtuous ones: the potential for schools to improve the life course. Pediatrics 2022;149:53509. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2021-053509M.Search in Google Scholar

12. Isara, AR, Nwaogwugwu, JC. Sexual and reproductive health knowledge, attitude and behaviours of in-school adolescents in Benin City, Nigeria. Afr J Biomed Res 2022;25:121–7. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajbr.v25i2.2.Search in Google Scholar

13. Nasution, SL, Kistiana, S, Gayatri, M, Naibaho, MMP. Reproductive health knowledge among adolescents in Indonesia: the role of family structure. Fam J 2022:2024. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221090950.Search in Google Scholar

14. Putri, A, Munirah, D, Tukimim, S, Utami, R, Ramadia, A. Knowledge of sexual and reproductive health among high school students, Batam, Indonesia. Sci Midwifery 2022;10:4237–45. https://doi.org/10.35335/midwifery.v10i5.1008.Search in Google Scholar

15. Tran, PT, Tran, DT, Vu, NH, Nguyen, LT, Tran, KB. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of medical students on human monkeypox in southern Vietnam. J Med Pharm Allied Sci 2023;12:6164–9. https://doi.org/10.55522/jmpas.V12I6.5367.Search in Google Scholar

16. Zarei, F, Dehghani, A, Ratansiri, A, Ghaffari, M, Raina, S, Halimi, A, et al.. ChecKAP: a checklist for reporting a knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 2024;25:2573–7. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2024.25.7.2573.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Sanchez, C, Dunning, D. Intermediate science knowledge predicts overconfidence. Trends Cognit Sci 2024;28:284–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.11.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Alsabi, RNS, Zaimi, AF, Sivalingam, T, Ishak, NN, Alimuddin, AS, Dasrilsyah, RA, et al.. Improving knowledge, attitudes and beliefs: a cross-sectional study of postpartum depression awareness among social support networks during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. BMC Womens Health 2022;22:12905. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01795-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Alomair, N, Alageel, S, Davies, N, Bailey, JV. Factors influencing sexual and reproductive health of Muslim women: a systematic review. Reprod Health 2020;17:12978. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0888-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Putri, A, Sansuwito, T. Developing knowledge of sexual and reproductive health among adolescent girls through a peer mentoring approach in nursing. Malaysian J Nurs 2025;16:205–14. https://doi.org/10.31674/MJN.2024.V16I02.020.Search in Google Scholar

21. WJ Creswell and JD Creswell, Research design: qualitative, quantitative adn mixed methods approaches, 53, 9. 2018. [Online]. Available:Search in Google Scholar

22. Pasay-an, E, Magwilang, JOG, Pangket, PP. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of adolescents regarding sexuality and reproductive issues in the Cordillera administrative region of the Philippines. Makara J. Heal. Res. 2020;24. https://doi.org/10.7454/msk.v24i3.1245.Search in Google Scholar

23. Andalib, MA. Simulation of the leaky pipeline: gender diversity in U.S. K-graduate education. J Simulat 2021;15:38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477778.2019.1620650.Search in Google Scholar

24. Theophilou, E, Hernández-Leo, D, Gómez, V. Gender-based learning and behavioural differences in an educational social media platform. J Comput Assist Learn 2023:2544–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12927. no. November 2023.Search in Google Scholar

25. Z Saadat and AM Sultana, “Understanding gender disparity: factors affecting higher education self-efficacy of students in Malaysia,” J Sci Technol Policy Manag., p. 2024, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-10-2022-0165.Search in Google Scholar

26. Das, K, Mahanta, A. Rural non-farm employment diversification in India: the role of gender, education, caste and land ownership. Int J Soc Econ 2023;50:741–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-06-2022-0429.Search in Google Scholar

27. Belošević, M, Ferić, M. Contribution of leisure context, motivation and experience to the frequency of participation in structured leisure activities among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2022;19:19020877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020877.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Popadić, D, Pavlović, Z, Kuzmanović, D. Intensive and excessive internet use: different predictors operating among adolescents. Psihol 2020;53:273–90. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI190805003P.Search in Google Scholar

29. Kusumawardani, LH, Jauhar, M, Rasdiyanah, R, Desy Rohana, IGAP. Pojokbelia : the study of smart phone application development as communicative, informative and educative (KIE) media innovation for adolescent reproductive health. J. Keperawatan Soedirman 2018;13:125. https://doi.org/10.20884/1.jks.2018.13.3.872.Search in Google Scholar

30. Halimi, L, Rabari, ED, Majdzadeh, R, Haghdoost, AA. Investigating the impact of the social network in the transfer of puberty information among adolescent students in Hamadan. Iran J Epidemiol 2023;18:270–81.Search in Google Scholar

31. Pengpid, S, Peltzer, K. Sexual behaviour and its correlates among adolescents in Brunei Darussalam. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2021;33:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2018-0028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Siswantara, P, Qomaruddin, MB, Bilqis, TRIB. How does self efficacy and motivation influence the adoption of sexual abstinence among students in Indonesia. Indian J Publ Health 2024;68:428–30. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.ijph-1075-23.Search in Google Scholar

33. Comfort, C. Evidence-based good practice for youth mentoring programmes. Int J Evid Based Coach Mentor 2024:195–207. https://doi.org/10.24384/r4rm-1c34.Search in Google Scholar

34. Wang, H, Diao, H, Yang, L, Li, T, Jin, F, Pu, Y. Relationship between adolescent knowledge-attitude-practice and resilience in left-behind children. Chinese J Sch Heal. 2020;41:1032–5. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.07.021.Search in Google Scholar

35. Laursen, B, Faur, S. What does it mean to be susceptible to influence? A brief primer on peer conformity and developmental changes that affect it. Int J Behav Dev 2022;46:222–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/01650254221084103.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Flanagan, EA, Erickson, HC, Parchem, SJ, Smith, CV, Poland, N, Nelson, SC, et al.. Gender differences in attitudes and behaviors toward condoms and birth control among Chicago adolescents. World Med Health Pol 2021;13:675–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.422.Search in Google Scholar

37. Klärner, A, Gamper, M, Keim-Klärner, S, Moor, I, von der Lippe, H, Vonneilich, N. Social networks and health inequalities. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022.10.1007/978-3-030-97722-1Search in Google Scholar

38. Kafadar, AH, Barrett, C, Cheung, KL. Knowledge and perceptions of Alzheimer’s disease in three ethnic groups of younger adults in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health 2021;21:12889. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11231-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Golshan, F, Bains, S, Francisco, J, Jensen, M, Tourigny, K, Morrison, T, et al.. Gender differences in concussion-related knowledge, attitudes and reporting behaviors of varsity athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fit 2024;64:588–98. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.24.15508-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Hakimee, NIA, Atan, A, Sutantri, S, Lee, SP. Health information-seeking behaviour on high-risk behaviour among adolescents. Malays J Med Sci 2023;30:181–91. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2023.30.5.15.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Kwon, MS, Choi, Y. Factors affecting preventive behavior related to tuberculosis among university students in Korea: focused on knowledge, attitude and optimistic bias related to tuberculosis. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs 2020;27:236–45. https://doi.org/10.7739/jkafn.2020.27.3.236.Search in Google Scholar

42. CV Adyana, T Nindy Aprilea, and , Muthmainnah,Muthmainnah, “Hubungan Pengetahuan, Sikap, dan Peran Orang Tua Terhadap Perilaku Pencegahan Kehamilan Remaja di SMA PGRI 1 Sidoarjo,” Media Publ Promosi Kesehat Indones 2023;6:693–7. https://doi.org/10.56338/mppki.v6i4.3214.Search in Google Scholar

43. McCrimmon, J, Widman, L, Javidi, H, Brasileiro, J, Hurst, J. Evaluation of a brief online sexual health program for adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Health Promot Pract 2024;25:689–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399231162379.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.