Storytelling in addiction prevention: A basis for developing effective programs from a systematic review

-

Isabel María Herrera-Sánchez

Abstract

Drug misuse is a complex social and health problem. People who use drugs have very specific profiles according to their life cycle and sociocultural circumstances. For this reason, contextualized approaches are needed in addiction interventions that take on board the particularities of consumption patterns and their circumstances. The storytelling technique as a narrative communication strategy can serve as the main methodological intervention component that enhances this contextualized approach.

Introduction

The latest European report on drug addiction begins from a meaningful point of departure: that the dynamic nature of drug problems represents a major challenge that needs to be addressed (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2018). People who take drugs develop different consumption patterns associated with multiple risk factors and varying circumstances. By adopting the community psychology approach, ecological diversity can be taken into account when dealing with the problems of use and misuse of substance, referring to “an appreciation of culture, context, and differences, including the complex intersectionalities of identity and substance misuse” (Olson, Emshoff, & Rivera, 2017, p. 402).

Research into the prevention of drug abuse has shown significant progress with the development of evidence-based programs. However, the literature shows that many of these programs have worked well in one social context have not generated the same results when extended to other contexts (Biglan & Hinds, 2009; Tobler et al., 2000). These problems are most evident when programs have been adapted from a rural context to an urban context (Komro et al., 2008), or when an attempt has been made to extrapolate their core intervention mechanisms to minority and low-income groups (Cho, Halfors, & Sánchez, 2005; Spoth, Guyll, Chao, & Molgaard 2003). Once again, the findings of these studies indicate the importance of the intervention context. For this reason, the problem is best conceptualized by approaching it from its historical, social and personal perspectives, which will enable us to understand the issue and offer effective responses.

A narrative communication strategy such as storytelling favors this contextualized and idiographic approach. This technique acknowledges the fact that telling stories about our lives is a natural human process. These stories are intrinsically linked to our own identity (McAdams, 2001); they create shared meanings of health and illness (Murray, 1999); and they foster a sense of belonging. From an empowerment approach (Rappaport, 2000), narratives based on strengths and capabilities encourage active and positive development. Thus, the characteristics that the narratives project can exert an influence on processes of change.

This technique has been increasingly applied in fields such as education, community-based interventions, public health and social marketing. In formal education, the experience of storytelling can, among other functions, help to shape one›s own experience in an understandable way, particularly in childhood, or offer a feasible model of language and thought (Collins, 1999). In a community setting, stories are viewed as a critical awareness tool for addressing issues that affect social well-being and social stability (Gregori-Signes & Alcantud-Díaz, 2016). Different problem areas have been addressed in the field of public health. These include initiatives aimed at empowering young people in diabetes prevention; gaining a better understanding of asthma; and helping participants in the early stages of dementia to build confidence and communication skills (Gubrium, Hill, & Flicker, 2014). In health communication, narrative-based strategies are easier for audiences to comprehend, generate more interest and invite more opportunities for identification than do scientific logic-based communication strategies (Dahlstrom, 2014).

Stories have always been present in drug addiction studies and in addiction prevention or treatment interventions. The aim of this systematic review is to identify the different approaches adopted in research studies that specifically use the storytelling technique. These include empirical studies of the factors associated with drug use and recovery as well as addiction prevention interventions. The end goal is to produce a narrative synthesis determining the foundations and strategies underlying storytelling-based interventions aimed at prevention.

Method

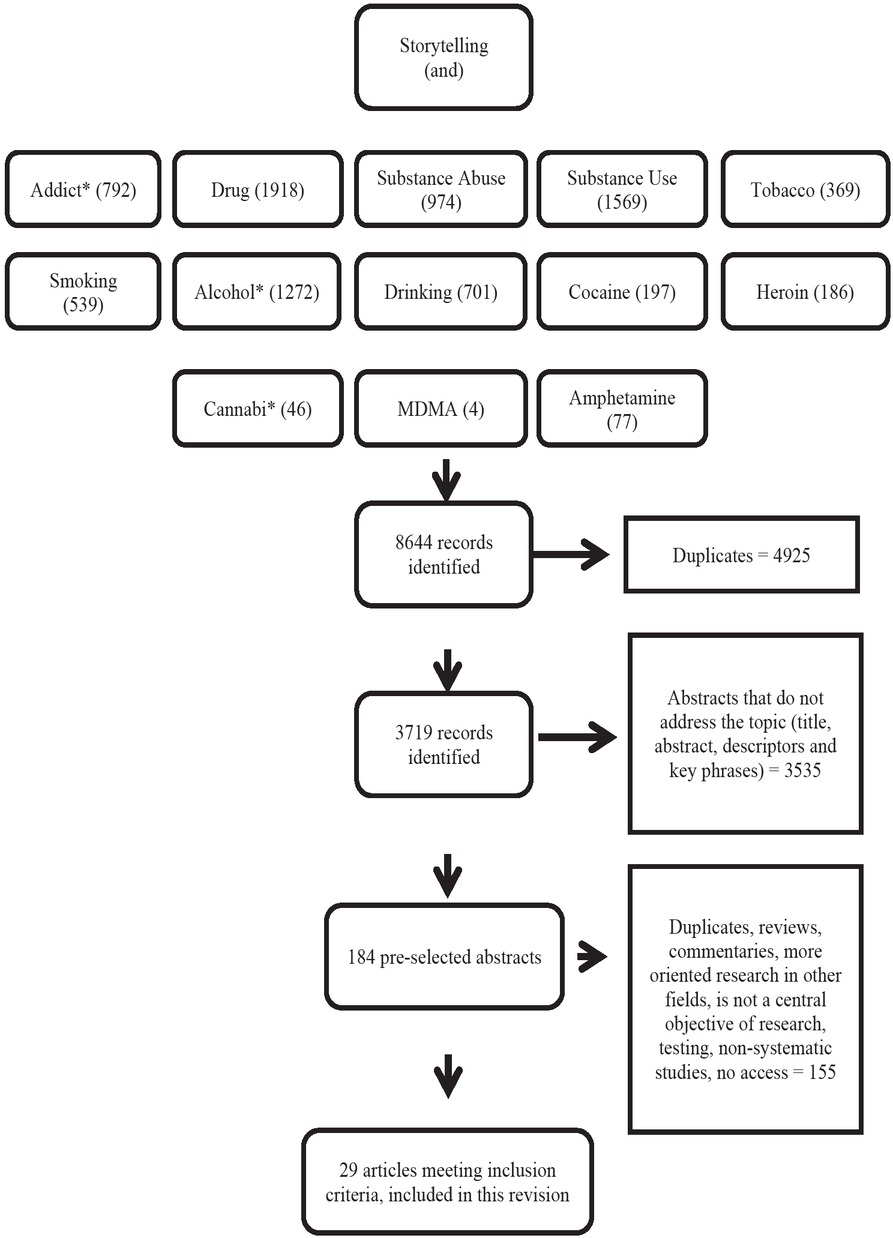

A systematic search for articles was performed across six databases using the ProQuest platform: Nursing & Allied Health Database, PsycINFO, MEDLINE®, Health & Medical Collection, PsycARTICLES, and Psychology Database. The term “storytelling” was used in combination (AND) with each of the following terms: addict*, drug*, substance abuse, tobacco, smoking, alcohol*, drinking, cocaine, heroin, cannabi*, MDMA, and amphetamine*. Articles reviewed by experts (from peer-review journals) and published before 1 January 2018 were chosen as an “Additional Limit”. All the paired searches were then run using a single search command (OR) to generate a single output file of all the results, thus allowing us to eliminate duplicates. All the studies had to be in English.

After an initial review of the titles, abstracts and main subjects, we eliminated articles that did not address the main topic of study. This task was performed by just one researcher. During the subsequent eligibility phases, two further researchers participated, as a higher level of consensus was required for selection purposes. The studies included in this review had to meet the following criteria: a) they had to be risk factor studies; b) they had to analyze the processes surrounding addiction and addiction recovery; and c) they had to discuss the implementation and effects of intervention. All had to clearly identify the storytelling technique and meet our methodological quality requirements. Theoretical reviews, commentaries, reports, descriptions of techniques and case studies were excluded. The criteria were designed for feasibility reasons and to cover the widest possible number of studies without compromising quality. To determine the quality of the study, a pluralist approach was adopted that encompassed multiple admissible angles and perspectives, and used quality-driven criteria specific to each approach (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, & Pawson, 2014). Research studies that lacked rigor in relation to the specific standards of the field were rejected.

Given the variety of studies to review, a narrative synthesis was conducted (Popay et al., 2006), which consisted of “an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarize and explain the findings of the synthesis” (p.5). The analysis process contained the following stages: a) a preliminary synthesis; b) an exploration of relationships; c) an evaluation of synthesis robustness; and d) the development of an emerging theory of suggestion-based intervention.

Results

The database search identified 3,719 records once duplicates had been filtered out. Following a preliminary review of each record, 184 were preselected, and we were left with 29 after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A flow diagram of the process is shown in Figure 1. The narrative analysis of the selected articles focused on detecting the approaches underlying these studies; the storytelling methods; the methodological aspects (method, context, population, substance); and the results or effects. For each of these elements, thematic categories were identified, as shown in Table 1. For the results or effects, we systematized the main conclusions as the studies displayed great diversity. The categories served as a rubric for the narrative synthesis of the study. Table 2 is the result of the narrative synthesis which emerged from the analysis. We now move onto the main findings and comment on the approaches underlying the studies yielded and how the practice of storytelling takes shape. The results section ends with the main premises that emerged from the analysis.

Flow Diagram

Thematic categories

| Approaches underlying the studies | Construction of meanings surrounding consumer practices |

| Narrative persuasion | |

| Narratives and processes of change in addiction recovery | |

| Narratives and processes of change integrated with other evidence-based programs | |

| Narratives and processes of change as core intervention component | |

| Culturally adapted prevention | |

| Drug interventions culturally adapted | |

|

|

|

| Storytelling | Fictional stories |

| True story construction | |

| Stories of experience | |

| Stories of support | |

| Shared experiences | |

| Stories shared in social circles | |

| Accounts of experiences in digital storytelling | |

|

|

|

| Methodology | Experimental design |

| Pilot project and evaluation | |

| Quasi-experimental design | |

| Randomized controlled trial | |

| Thematic analysis with focus groups | |

| Narrative study | |

| Grounded Theory | |

| Ethnographic method | |

| Community-based participatory research | |

| Mixed methods | |

|

|

|

| Context | Schools / High school / College campus |

| Tourist destination | |

| Indian reservation / Native communities | |

| Urban and rural areas / Rural counties | |

| Public housing neighborhoods | |

| Homes, service housing or nursing homes | |

| Youth-centered community health care | |

| Foster care | |

| Addiction Treatment Centre | |

| Hospital | |

| AA meetings / Narcotics Anonymous meetings | |

| Countries (Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Iran, | |

| UK, USA) | |

|

|

|

| Participants | Teenagers |

| Young people | |

| High school students / College students | |

| Young tourists | |

| Elderly people | |

| At-risk groups | |

| Youth with risk factors | |

| Children from methamphetamine-involved families | |

| African American | |

| African American women | |

| American Indians | |

| Alaskan Native youth | |

| Marginalized groups | |

| AA members / Narcotics Anonymous members | |

|

|

|

| Substance | Alcohol, Tobacco, Drugs use, Methamphetamine |

|

|

|

| Result/Effects | Authors’ main findings |

Narrative synthesis of selected studies before 1 January 2018

| Approaches underlying the studies | Storytelling | Methodology | Context / Participants / Substance | Results / Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction of meanings surrounding consumer practices |

Fictional stories

Kean & Albada (2003) |

Experimental design

Kean & Albada (2003) |

College campus / College students/Alcohol

Kean & Albada (2003). USA |

The stories connect the real world with scenes that come from television (Kean & Albada, 2003). |

|

Shared experiences

Roche et al. (2005) Tolvanen & Jylhä (2005) Mitev (2007) Tutenges & Sandberg (2013) |

Narrative study

Tolvanen & Jylhä (2005) Mitev (2007) Rance et al. (2017) |

College campus / College students/Alcohol

Mitev (2007). Hungary Burnett et al. (2016). USA |

The stories delineate the boundaries and establish the acceptability of risk behaviors (Roche et al., 2005). The stories inject an unalterable moral discourse over time (Tolvanen & Jylhä, 2005). | |

| Rance et al. (2017) |

Grounded Theory

Roche et al. (2005) Burnett et al. (2016) |

Homes, service housing or nursing homes / Elderly people / Alcohol

Tolvanen & Jylhä (2005). Finland |

Credible stories can be constructed by relying on literary plots (Mitev, 2007). | |

|

In digital storytelling

Burnett et al. (2016) |

Mixed methods Tutenges & Sandberg (2013) |

Marginalized groups / Drug use

Roche et al. (2005). USA Rance et al. (2017). Australia |

The stories act as a behavioral script (Tutenges & Sandberg, 2013). Inequality discourse as another form of social injustice (Rance et al., 2017). |

|

|

Tourist destination / Young tourists / Alcohol

Tutenges & Sandberg (2013). Bulgaria |

The stories create meaning around the excessive alcohol consumption behavior to frame it in an acceptable way (Burnett et al, 2016). | |||

| Stories shared in social circles | Thematic analysis with focus groups | Indian reservation / American Indians / Alcohol | Intergenerational transfer of learning and personal experiences (Momper et al., 2017). | |

| Tutenges & Rod (2009) | Momper et al. (2017) | Momper et al. (2017). USA | ||

| Momper et al. (2017) | Ethnographic method Tutenges & Rod (2009) |

Urban and rural areas / Teenagers / Alcohol

Tutenges & Rod (2009). Denmark |

Identity, critical awareness (Tutenges & Rod, 2009). | |

| Narratives and processes of change in addiction recovery |

Stories of support

Humphreys (2000)

Swora (2002) Arminen (2004) |

Narrative study

Humphreys (2000)

Swora (2002) |

AA members / Alcohol

Humphreys (2000). USA Swora (2002). USA Lederman & Menegatos (2011). |

Community narratives include personal stories from former members that also give shape to the personal accounts of new members (Humphreys, 2000). |

| Weegmann & Piwowoz-Hjort (2009) | Weegmann & Piwowoz-Hjort (2009) | USA | A performance genre that creates a sense of community (Swora, 2002). | |

| Lederman & Menegatos (2011) | Arminen (2004) Strobbe & Kurtz (2012) |

AA meetings / Alcohol

Arminen (2004). Finland |

They are the basis for mutual help and social support via co-constructing experiences (Arminen, 2004). | |

| Strobbe & Kurtz (2012) | Grounded Theory | Addiction Treatment Centre / Alcohol | Stories rebuild self-identity (Weegmann & Piwowoz-Hjort, 2009). | |

| Lederman & Menegatos (2011) | Weegmann & Piwowoz-Hjort (2009). UK | Narrative coherence and fidelity in AA stories (Lederman & Menegatos, 2011). | ||

|

Big Book 4th edition/Alcohol

Strobbe & Kurtz (2012) |

Community narratives act as prototypes in self-help contexts (Strobbe & Kurtz, 2012). | |||

|

Shared experiences

Rafalovich (1999)

Dunlop & Tracy (2013) |

Grounded theory

Rafalovich (1999)

Mixed methods (with narrative) |

Narcotics Anonymous meetings

Rafalovich (1999). USA AA meetings / Alcohol |

The addict's identity in self-help contexts is articulated through moments of equality, understanding and personal investment (Rafalovich, 1999). | |

| Christensen & Elmeland (2015) | Dunlop & Tracy (2013) | Dunlop & Tracy (2013). Canada AA members / Alcohol Christensen & Elmeland (2015). |

Narratives exploring negative experiences interpreted as conducive to a positive change predict later behavior change (Dunlop & Tracy, 2013). | |

| Christensen & Elmeland (2015) | Denmark | Identification is important to AA members attempting to stay sober, whereas those attempting to recover unaided prefer to give an appearance of abusive use but not problematic use (Christensen & Elmeland, 2015). | ||

| Narrative persuasion |

Fictional stories

Ma & Nan (2018) |

Experimental design Ma & Nan (2018) |

College campus / College students / Tobacco Ma & Nan (2018). USA |

Did not confirm that the narratives (vs. non-narrated) would be more persuasive than non-narratives when people thought about socially close smokers (Ma & Nan, 2018). |

| Narratives and processes of change integrated with other evidence-based programs | Stories of experience Leukefeld et al. (2003) | Experimental design Leukefeld et al. (2003) |

Rural counties/At risk groups/ Drug use

Leukefeld et al. (2003). USA |

Gaining access to a group of rural people at high risk of contracting HIV/AIDS (Leukefeld et al., 2003). |

| Accounts of experiences in digital storytelling | Pilot project and evaluation Houston et al. (2011) | Hospital / African American / Tobacco Houston et al. (2011). USA | Success relative to gathering narratives to be mapped to behavioral constructions (Houston et al., 2011). | |

| Houston et al. (2011) Cherrington et al. (2015) | Randomized controlled trial | Cherrington et al. (2015). USA | Insufficient as an independent intervention (Cherrington et al., 2015). | |

| Cherrington et al. (2015) | ||||

| Narratives and processes of change as core intervention component | True story construction Moghadam et al. (2016) | Quasi-experimental Moghadam et al. (2016) | High school / Students / Drug use Moghadam et al. (2016). Iran | Significant reduction in readiness to addiction among adolescents who participated in the intervention (Moghadam et al., 2016). |

| Culturally adapted prevention | Fictional storiesInsufficient as an independent intervention Nelson & Arthur (2003) |

Quasi-experimental

Nelson & Arthur (2003) |

Schools / Youth with risk factors / Drug use

Nelson & Arthur (2003). USA |

Reduction in the consumption of alcohol and marijuana and a correlation with the number of program contact hours (Nelson & Arthur, 2003). |

| Cordova et al. (2015) | Community-based | Youth-centered community health | ||

| Cordova et al. (2018) | participatory research | care/ Adolescents and young people / Drug use | Highlighted the barriers and facilitators (Cordova et al., 2015). | |

| Cordova et al. | Cordova et al. (2015). USA | Program usability and acceptability | ||

| (2015) | Cordova et al. (2018). USA | (Cordova et al., 2018). | ||

| Cordova et al. (2018) | ||||

| Drug interventions culturally adapted |

Stories of support

Andrews et al. (2007) |

Community-based participatory research Andrews et al. |

Public housing neighborhoods/ African American women / Tobacco Andrews et al. (2007). USA Foster care / Children from methamphetamine-involved families. Haight et al. (2010). USA |

Surface structure changes enhanced interest, acceptance and viability, whereas the deep structure facilitated context adaptation and strengthened the study's |

| Stories of experience | (2007) | impact and general efficacy (Andrews et al. 2007). | ||

| Haight et al. (2010) | Mixed methods | |||

|

Fictional stories

Montgomery et al. (2012) |

Haight et al. (2010) | Slight improvement in behavior problems among children participating in the intervention (Haight et al., 2010). | ||

| Pilot project and evaluation | Native communities / American Indian and Alaskan Native youth / Tobacco | |||

| Montgomery et al. (2012) | Montgomery et al. (2012). USA | Involving native youth in the intervention (Montgomery et al., 2012). |

Regarding the approaches underlying the studies, the first category consisted of research on the construction of meanings that revolve around consumer practices (visions, values, myths, beliefs, schema). It included analyses of discursive practices that have helped detect the culturally shared meanings surrounding consumer practices from a generational perspective (Burnett, Ott Walter, & Baller, 2016; Momper, Dennis, & Mueller-Williams, 2017; Tolvanen & Jylhä, 2005; Tutenges & Rod, 2009), and of the implications for consumption (Tutenges & Sandberg, 2013). On another level, an article by Mitev (2007) set out to identify how implicit mythology is projected in literary works within users’ personal narratives, while Kean and Albada (2003) sought to determine the effects in the manner in which alcohol consumption stories are constructed by looking for a connection between media, personal experience and schema formation. Another study, by Roche, Neaigus, and Miller (2005), looked at socially isolated and disadvantaged groups and sought to identify the forms of adaptation to the environment in the shared stories of drug-using women who engage in sex work. Rance, Gray, and Hopwood (2017) focused on how people who inject drugs, victims of stigma and social hostility, are put at a disadvantage when it comes to making sense of their social experience.

The second category gave us studies that explore how the telling of personal and community-based stories are an important part of recovery processes in mutual help groups, mainly Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) groups. Rafalovich (1999) analyzed the identity transformation process through the sharing of stories. Lederman and Menegatos (2011) focused on the intrapersonal impact of AA narratives by adopting a retrospective approach, much like that used by Weegmann and Piwowoz-Hjort (2009). Arminen (2004) examined the functions of second stories in reconstructing group identity and in reinterpreting shared problems. Christensen and Elmeland (2015) found differences in how narratives of addiction recovery play out between people who attend self-help groups and those who decide to do it alone. Strobbe and Kurtz (2012) and Humphreys (2000) placed transformative storytelling at community narrative levels, while Swora (2002) positioned these stories as social practices that build their own social structure. These processes of change are also considered in Dunlop and Tracy’s (2013) study, which analyzed positive self-transformation processes following a difficult experience, identifying the relationship between self-redemption and behavior change in the narratives.

Using a narrative persuasion approach, Ma and Nan (2018) wanted to see how nonsmokers respond to health messages (narrative vs. non-narrative), aimed at persuading others to stop smoking, in their examination of the moderating role of social distance. In the intervention studies in this category, narratives were introduced alongside evidence-based interventions with the aim of contextualizing the messages (Cherrington et al., 2015; Houston et al., 2011; Leukefeld et al., 2003). Moghadam, Sari, Balouchi, Madarshahian, and Moghadam (2016) addressed storytelling-based education as a core component in prevention.

Lastly, we found studies that incorporated storytelling with the support of community-based participatory strategies into the development of culturally adapted interventions. Nelson and Arthur (2003) developed a program called “Storytelling for Empowerment” as a way of encouraging positive cultural identity. This program was later adapted within the mHealth platform, incorporating the principles of community-based participatory research (Cordova et al., 2015; 2018). In a study conducted by Andrews, Bentley, Crawford, Pretlow, and Tingen (2007), members of the community were enlisted to help develop a culturally sensitive intervention involving African American women who live in subsidized housing. “Life Story Intervention” is a program by Haight, Black, and Sheridan (2010) devised in collaboration with community professionals, which introduces sociocultural theory into evidence-based interventions and local narrative traditions in order to address the mental health symptoms of children whose parents take amphetamines. Montgomery, Manuelito, Nass, Chock, and Buchwald (2012) expressed the view that an intervention is more likely to succeed if its methods are consistent with the cultural practices of the native communities and if young people are actively involved in the production of educational content.

In this narrative review, we were also interested in the way in which the practice of storytelling takes shape when gathering narrative data or as an intervention component. The first category of studies contained those in which the researchers invited participants to relate their experiences for different purposes: to analyze the events that unfold in the narratives (Tutenges & Sandberg, 2013); to identify the moral discourses and shared cultural expectations between generations (Tolvanen & Jylhä, 2005); and to see how they mimic literary plots (comedy, romance, tragedy, irony) between the events and the different ways of telling stories (Mitev, 2007). In challenging contexts, storytelling has served to identify positive self-change experiences following a negative experience as self-redemption narratives (Dunlop & Tracy, 2013). In therapeutic settings, people are invited to talk about their lives or simply to talk (Haight et al., 2010). Burnett et al. (2016), Houston et al. (2011), and Cherrington et al. (2015) used a digital format as opposed to face-to-face strategies.

Stories told in social circles and which often surface in informal conversations (Tutenges & Rod, 2009), or those characteristic of interpersonal communication in native communities (Momper et al., 2017), are also a source of analysis. This is also the case in interventions. In Andrews et al. (2007), informal and interactive group sessions that promoted storytelling were used as a teaching method. Montgomery et al. (2012) introduced native elder traditions to pass on knowledge through stories in their educational interventions.

Storytelling as a specific practice in mutual help settings becomes an entity in its own right in the scientific addictions literature. Stories are told to emphasize the act of helping others and to include personal life stories in community-based narratives. Lederman and Menegatos (2011) analyzed the reflective accounts of AA members’ efforts to stay sober, whereas Strobbe and Kurtz (2012) used personal stories in the Big Book of AA as the sole source. Arminen (2004) focused on the “second stories” that emerged in response to an original story and which contributed to mutual help and social support. Humphreys (2000) focused his analysis on the content, structures and function(s) of AA stories.

Fictional stories are also part of stories that are told for different purposes. Kean and Albada (2003) asked participants to write a story to capture their representation of an object. Ma and Nan (2018) used simulated stories to illustrate health consequences. Cordova et al. (2015) incorporated culturally congruent stories into an mHealth application. And in Moghadam et al. (2016), stories of addicts were first exposed, and then young people participated in the creation of the stories.

By examining these research studies and performing the outcome analysis, we obtained the following premises which indicate the suitability of storytelling for preventive interventions:

Stories are a gateway to health intervention efforts, particularly when working with marginalized communities, as risk reduction and health promotion messages can be incorporated within oral traditions (Haight et al., 2010; Nelson & Arthur, 2003; Roche et al., 2005). These may include topics deemed threatening or which remain hidden (Tutenges & Rod, 2009) and which call for closer scrutiny of and attention to the community’s values and culture (Andrews et al., 2007).

Narratives should be based on strengths and capabilities to encourage active and positive development. Thus, programs need to adopt a positive social function (Burnett et al., 2016) and contemplate community involvement whereby the participants themselves can decide how to share their personal stories of drug and alcohol use. Although these experiences are different and unique to the individual, they have a clearly identifiable cause and follow an effect trajectory (Tutenges & Sandberg, 2013) which plays a contributing role in self-reflection on personal and social identity (Arminen, 2004; Momper et al., 2017; Rafalovich, 1999; Tutenges & Rod, 2009). The sharing of drug abuse stories should encourage recipients to critically assess the negative consequences (Tutenges & Rod, 2009) and potentially delineate boundaries and establish levels of acceptability regarding risk behaviors (Roche et al., 2005). However, they also project moral discourses that hold over time for each generation (Tolvanen & Jylhä, 2005), where the real and the imaginary meet (Humphreys, 2000; Kean & Albada, 2003; Roche et al., 2005). The stories remain tied to the context in which they occur (Burnett et al., 2016; Cherrington et al., 2015; Momper et al., 2017), meaning that it is particularly relevant to take on board the potential injustices and challenges that marginalized groups face in telling their stories because their discourses are often permeated by stigma and social exclusion (Rance et al., 2017).

Narratives act as motivators that go beyond the intrapersonal impact that the storytelling process itself generates (Lederman & Menegatos, 2011). These stories have considerable potential to stimulate change among those who listen to and share these experiences (Arminen, 2004; Moghadam et al., 2016; Nelson & Arthur, 2003; Strobbe & Kurtz, 2012; Weegmann & Piwowoz-Hjort, 2009), and prove more effective when coupled with other techniques (Cherrington et al., 2015; Cordova et al., 2015; Houston et al., 2011). These told stories reinforce addiction recovery through a process of sharing positive accounts of people’s personal lives in mutual help contexts. They become persuasive stories at an intrapersonal level (Dunlop & Tracy, 2013; Lederman & Menegatos, 2011), an interpersonal level (Arminen, 2004; Weegmann & Piwowoz-Hjort, 2009), and at the level of the community’s social structure (Swora, 2002). Intentionally transmitted stories, which reflect a desired community narrative, are intended to be seen as prototypes (Strobbe & Kurtz, 2012).

Conclusion

These findings lead us to reflect on current practices in addiction prevention and health promotion, which tend to offer segmented information relative to the conceptual constructs derived from theoretical models. The selection of health messages according to the emphasis theoretical models place on what should be changed and how is a widespread practice, without taking into account the surrounding circumstances in an attempt to achieve generalization. The literature provides examples of programs that fail when developed in contexts that differ from the one in which the intervention originated. For this reason, strategies for change should be sensitive to the culture; they should be based on a consideration of the obstacles to participation that highly stigmatized groups have to overcome; and they should reinforce the discursive practices that unfold when experiences are shared. The stories are full of meanings that tap into personal experiences and the cultural, social and historical values of the group of belonging. As such, it is reasonable to assume that if identification is strengthened through these stories, then a willingness to change is more likely.

The main limitation of this systematic revision comes from using the term storytelling as the only search descriptor, excluding other possible related terms such as narrative communication. This procedure may have excluded other studies of relevance. The variety of studies selected is another limitation, that is, they are not exclusively implementation or effectiveness studies. For this reason, a narrative synthesis was used to enable us to extract the most relevant aspects according to the objective of the review.

Nonetheless, this review enables us to delineate a future line of research aimed at determining the effectiveness of the storytelling-based strategy as a motivating mechanism for change by eliciting the identification with history. This is especially relevant to specific groups (low resource groups, at risk groups, ethnic groups etc.) because they enhance their own personal stories of improvement. As a direct practical implication, designers of preventive programs with multiple components are encouraged to incorporate storytelling-based strategy as a method of developing a culturally adapted intervention.

References

Andrews, J. O., Bentley, G., Crawford, S., Pretlow, L., & Tingen, M. S. (2007). Using community-based participatory research to develop a culturally sensitive smoking cessation intervention with public housing neighborhoods. Ethnicity & Disease, 17(2), 331-337.Suche in Google Scholar

Arminen, I. (2004). Second stories: The salience of interpersonal communication for mutual help in Alcoholics Anonymous. Journal of Pragmatics, 36(2), 319-347.10.1016/j.pragma.2003.07.001Suche in Google Scholar

Biglan, A., & Hinds, E. (2009). Evolving prosocial and sustainable neighborhoods and communities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5 169-196.10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153526Suche in Google Scholar

Burnett, A. J., Ott Walter, K., & Baller, S. L. (2016). Blackouts to lifelong memories: Digital storytelling and the college alcohol habitus. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 25(1), 49-56.10.1080/1067828X.2014.889634Suche in Google Scholar

Cherrington, A., Williams, J. H., Foster, P. P., Coley, H. L., Kohler, C., Allison, J. J., … Houston, T. K. (2015). Narratives to enhance smoking cessation interventions among African-American smokers, the ACCE project. BMC Research Notes, 8 567.10.1186/s13104-015-1513-1Suche in Google Scholar

Cho, H., Halfors, D. D., & Sánchez, V. (2005) Evaluation of a high school peer group intervention for at-risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(3), 363-374.10.1007/s10802-005-3574-4Suche in Google Scholar

Christensen, A.-S., & Elmeland, K. (2015). Former heavy drinkers’ multiple narratives of recovery. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 32(3), 245-257.10.1515/nsad-2015-0024Suche in Google Scholar

Collins, F. (1999). The use of traditional storytelling in education to the learning of literacy skills. Early Child Development and Care152 77-10810.1080/0300443991520106Suche in Google Scholar

Cordova, D., Alers-Rojas, F., Lua, F. M., Bauermeister, J., Nurenberg, R., Ovadje, L., … Council, Y. L. (2018). The usability and acceptability of an adolescent mHealth HIV/STI and drug abuse preventive intervention in primary care. Behavioral Medicine44(1), 36-47.10.1080/08964289.2016.1189396Suche in Google Scholar

Cordova, D., Bauermeister, J. A., Fessler, K., Delva, J., Nelson, A., Nurenberg, R., … Youth, L. C. (2015). A community-engaged approach to developing an mHealth HIV/STI and drug abuse preventive intervention for primary care: A qualitative study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(4), 106.10.2196/mhealth.4620Suche in Google Scholar

Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(4), 13614-13620.10.1073/pnas.1320645111Suche in Google Scholar

Dunlop, W. L., & Tracy, J. L. (2013). Sobering stories: Narratives of self-redemption predict behavioral change and improved health among recovering alcoholics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(3), 576-590.10.1037/a0031185Suche in Google Scholar

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2018) European Drug Report 2018: Trends and Developments Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.Suche in Google Scholar

Gregori-Signes, C., & Alcantud-Díaz, M. (2016). Digital community storytelling as a sociopolitical critical device. Journal of Community Positive Practices, 16(1), 19-36.Suche in Google Scholar

Gubrium, A. C., Hill, A. L., & Flicker, S. (2014). A situated practice of ethics for participatory visual and digital methods in public health research and practice: A focus on digital storytelling. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1606-1614.10.2105/AJPH.2013.301310Suche in Google Scholar

Haight, W., Black, J., & Sheridan, K. (2010). A mental health intervention for rural, foster children from methamphetamine-involved families: Experimental assessment with qualitative elaboration. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1446-1457.10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.024Suche in Google Scholar

Houston, T. K., Cherrington, A., Coley, H. L., Robinson, K. M., Trobaugh, J. A., & Williams, J. H. (2011). The art and science of patient storytelling— Harnessing narrative communication for behavioral interventions: The ACCE Project. Journal of Health Communication, 16(7), 686-697.10.1080/10810730.2011.551997Suche in Google Scholar

Humphreys, K. (2000). Community narratives and personal stories in Alcoholics Anonymous. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(5), 495-506.10.1002/1520-6629(200009)28:5<495::AID-JCOP3>3.0.CO;2-WSuche in Google Scholar

Kean, L. G., & Albada, K. F. (2003). The relationship between college students’ schema regarding alcohol use, their television viewing patterns, and their previous experience with alcohol. Health Communication, 15(3), 277-298.10.1207/S15327027HC1503_2Suche in Google Scholar

Komro, K., Perry, C., Veblen-Mortensen, S., Farbakhsh, K., Toomey, T., Stigler, M., … Williams, C. L. (2008). Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a multi-component alcohol use preventive intervention for urban youth: Project Northland Chicago. Addiction, 103(4), 606-618.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02110.xSuche in Google Scholar

Lederman, L. C., & Menegatos, L. M. (2011). Sustainable recovery: The self-transformative power of storytelling in Alcoholics Anonymous. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 6(3), 206-227.10.1080/1556035X.2011.597195Suche in Google Scholar

Leukefeld, C., Roberto, H., Hiller, M., Webster, M., Logan, T. K., & Staton-Tindall, M. (2003). HIV prevention among high-risk and hard-to-reach rural residents. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(4), 427-434.10.1080/02791072.2003.10400489Suche in Google Scholar

Ma, Z., & Nan, X. (2018). Friends don’t let friends smoke: how storytelling and social distance influence nonsmokers’ responses to antismoking messages. Health Communication, 33(7), 887-89510.1080/10410236.2017.1321162Suche in Google Scholar

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100-122.10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100Suche in Google Scholar

Mitev, A. (2007). A narrative analysis of university students’ alcohol stories in terms of a Fryeian framework. European Journal of Mental Health, 2(2), 205-233.10.1556/EJMH.2.2007.2.5Suche in Google Scholar

Moghadam, M. P., Sari, M., Balouchi, A., Madarshahian, F., & Moghadam, K. (2016). Effects of storytelling-based education in the prevention of drug abuse among adolescents in Iran based on a readiness to addiction index. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 10(11), IC06-IC09.10.7860/JCDR/2016/23170.8799Suche in Google Scholar

Momper, S. L., Dennis, M. K., & Mueller-Williams, A. C. (2017). American Indian elders share personal stories of alcohol use with younger tribal members. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 16(3), 293-313.10.1080/15332640.2016.1196633Suche in Google Scholar

Montgomery, M., Manuelito, B., Nass, C., Chock, T., & Buchwald, D. (2012). The Native Comic Book Project: Native youth making comics and healthy decisions. Journal of Cancer Education, 27(Suppl 1), S41-46.10.1007/s13187-012-0311-xSuche in Google Scholar

Murray, M. (1999). The storied nature of health and illness. In M. Murray & K. Chamberlain (Eds.), Qualitative health psychology: Theories and methods London, Sage.10.4135/9781446217870Suche in Google Scholar

Nelson, A., & Arthur, B. (2003). Storytelling for Empowerment: Decreasing At-Risk Youth’s Alcohol and Marijuana Use. Journal of Primary Prevention, 24(2), 169-180.10.1023/A:1025944412465Suche in Google Scholar

Olson, B. D., Emshoff, J., & Rivera, R. (2017). Substance use and misuse: The community psychology of prevention, intervention, and policy. In M. A. Bond, I. Serrano-García, C. B. Keys & M. Shinn (Eds.), APA handbook of community psychology: Methods for community research and action for diverse groups and issues (vol. 2) (pp. 393-407). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.10.1037/14954-023Suche in Google Scholar

Popay, J., Roberts, H, Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Results of an ESRC funded research project (unpublished report). University of Lancaster.Suche in Google Scholar

Rafalovich, A. (1999). Keep coming back! Narcotics anonymous narrative and recovering-addict identity. Contemporary Drug Problems, 26(1), 131-157.10.1177/009145099902600106Suche in Google Scholar

Rance, J., Gray, R., & Hopwood, M. (2017). “Why am I the way I am?” narrative work in the context of stigmatized identities. Qualitative Health Research, 27(14), 2222-2232.10.1177/1049732317728915Suche in Google Scholar

Rappaport, J. (2000). Community narratives: Tales of terror and joy. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 1-24.10.1023/A:1005161528817Suche in Google Scholar

Roche, B., Neaigus, A., & Miller, M. (2005). Street smarts and urban myths: women, sex work, and the role of storytelling in risk reduction and rationalization. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 19(2), 149-170.10.1525/maq.2005.19.2.149Suche in Google Scholar

Spoth, R., Guyll, M., Chao, W., & Molgaard, V. (2003). Exploratory study of a preventive intervention with general population African American families. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 23(4), 435-68.10.1177/0272431603258348Suche in Google Scholar

Strobbe, S., & Kurtz, E. (2012). Narratives for recovery: personal stories in the “Big Book” of alcoholics anonymous. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 7(1), 29-52.10.1080/1556035X.2012.632320Suche in Google Scholar

Swora, M. G. (2002). Narrating community: The creation of social structure in alcoholics anonymous through the performance of autobiography Narrative Inquiry, 11(2), 363-384.10.1075/ni.11.2.06swoSuche in Google Scholar

Tobler, N. S., Roona, M. R., Ochshorn, P., Marshall, D. G., Streke, A. V., & Stackpole K. M. (2000). School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention, 20(4), 275-336.10.1023/A:1021314704811Suche in Google Scholar

Tolvanen, E., & Jylhä, M. (2005). Alcohol in life story interviews with Finnish people aged 90 or over: Stories of gendered morality. Journal of Aging Studies, 19(4), 419-435.10.1016/j.jaging.2004.11.001Suche in Google Scholar

Tutenges, S., & Rod, M. H. (2009). “We got incredibly drunk … it was damned fun”: Drinking stories among Danish youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 12(4), 355-370.10.1080/13676260902866496Suche in Google Scholar

Tutenges, S., & Sandberg, S. (2013). Intoxicating stories: The characteristics, contexts and implications of drinking stories among Danish youth. International Journal of Drug Policy, 24(6), 538-544.10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.011Suche in Google Scholar

Weegmann, M., & Piwowoz-Hjort, E. (2009). Naught but a story: Narrative of successful AA recovery. Health Sociology Review, 18(3), 273-283.10.5172/hesr.2009.18.3.273Suche in Google Scholar

Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., & Pawson, R. (2014). Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses – Evolving Standards) project Health Services and Delivery Research, 2(30). 10.3310/hsdr02300Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Institute for Research in Social Communication, Slovak Academy of Sciences

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Introductory community psychology in Slovakia

- Non-expert views of compassion: consensual qualitative research using focus groups

- Emotion-focused training for emotion coaching – an intervention to reduce self-criticism

- Storytelling in addiction prevention: A basis for developing effective programs from a systematic review

- The role of group experience in alternative spiritual gatherings

- The silver lining between perceived similarity and intergroup differences: Increasing confidence in intergroup contact

- Contemporary commons: Sharing and managing common-pool resources in the 21st century

- Stress and the working poor

- Visible as people, yet invisible as jews

- Maintaining borders: From border guards to diplomats

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Introductory community psychology in Slovakia

- Non-expert views of compassion: consensual qualitative research using focus groups

- Emotion-focused training for emotion coaching – an intervention to reduce self-criticism

- Storytelling in addiction prevention: A basis for developing effective programs from a systematic review

- The role of group experience in alternative spiritual gatherings

- The silver lining between perceived similarity and intergroup differences: Increasing confidence in intergroup contact

- Contemporary commons: Sharing and managing common-pool resources in the 21st century

- Stress and the working poor

- Visible as people, yet invisible as jews

- Maintaining borders: From border guards to diplomats