Abstract

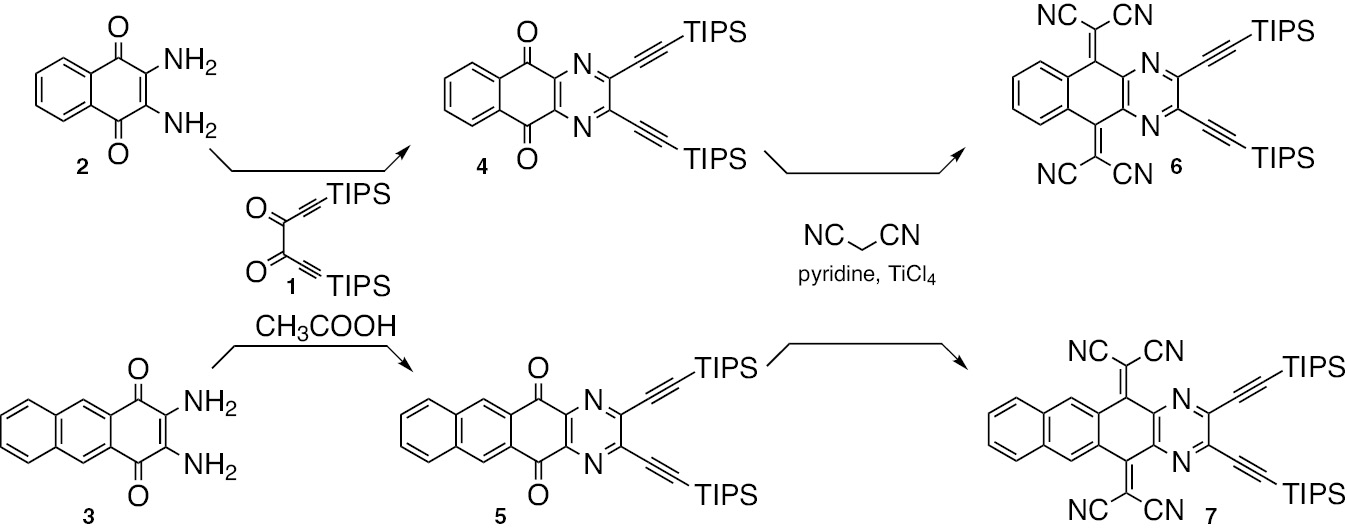

Two new aza-acenequinone derivatives 4 and 5 were prepared by cyclocondensation of diamines 2 and 3 with bis(triisopropylsilyl)-dialkynyl-l,2-dione 1. Further reactions of compounds 4 and 5 with malononitrile using the Lehnert reagent afforded corresponding tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) derivatives 6 and 7. Compounds 4, 6 and 7 were characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction techniques. Compounds 6 and 7 were studied electrochemically and photochemically. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations on compounds 6 and 7 indicate that both compounds have the potential to be candidates for organic semiconductor materials.

Tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ)-based molecules have been widely used due to their electrical and magnetic properties [[1], [2], [3], [4]. The electron-accepting abilities of TCNQ derivatives have been explored by extending their π-system [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. This π-system extension, based on the cyclic voltammetry (CV) data, which shows more negative reduction potentials compared with TCNQ, indicates that TCNQ derivatives are poorer electron acceptors than TCNQ [5], [6], [7]. However, having high electron affinities, π-extended TCNQ derivatives have been reported as novel n-type organic semiconductors [10], [11], [12], [13]. On the other hand, less symmetrical TCNQ derivatives demonstrate a better molecular packing which is manifested by better electron-accepting ability in the solid state 5]. One of the necessary properties for the n-type semiconductors is high electron affinity. Two other key issues needed to be considered are the molecular shape which impacts the solid-state packing and the ability to accept and transport electrons. As of today, a large variety of organic p-type semiconductors have been prepared for practical applications as organic field effect transistors (OFETs); however, only a limited number of solution-processed n-type organic thin film transistors with high performance have been reported [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. This uneven development makes the exploration of candidates for n-type semiconductors highly desirable. In the design of new potential n-type semiconductor molecules, we are focused on less symmetrical TCNQ derivatives as TCNQ brings the strong electron affinity into the system. Several other critical factors that may affect the charge carrier mobility are considered as well. These factors include the expansion of the number of rings, the incorporation of nitrogen atoms which have strong electron affinity and lower highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energies of the molecule, and the incorporation of compound 1 (Scheme 1) into the system to efficiently promote product solubility. In this paper, we present the synthesis of two potential OFET molecules; their crystal structures were analyzed to examine the molecular shapes and solid-state packing and CV was used to evaluate their electron-accepting ability.

Synthesis of compounds 4–7.

2,3-Diamino-1,4-naphthalenedione (2) [[19] was allowed to react with bis(triisopropylsilyl)-dialkynyl-l,2-dione 1 [20] in acetic acid to afford compound 4. Compound 4 was converted into compound 6 in the presence of the Lehnert reagent with an 80% overall yield (Scheme 1). Similarly, compound 7 was synthesized in a 67% overall yield from 2,3-diamino-1,4-anthracenedione (3) [21]. The reactions were completed under ambient conditions within 30 min. New compounds 4–7 are soluble in common organic solvents such as hexanes and dichloromethane. Well-resolved proton 1H NMR spectra of 4–7 display sharp aromatic peaks. With the steric interactions between dicyanomethylene groups of the TCNQ moiety and hydrogens at adjacent peri positions, both 6 and 7 were expected to have a nonplanar geometry. This molecular shape of 6 and 7 was confirmed by X-ray single crystal analysis [22] (Figure 1). Suitable single crystals of 6 were grown from a benzene solution while those of 7 were grown from dichloromethane/methanol. Both compounds adopt butterfly-type structures. There are close interactions between the cyano groups and the carbon atoms of the adjacent molecules in the solid state. However, no significant π-stacking interaction is observed. These structural features may indicate that both compounds are not good candidates for further device application. The dihedral angles (α) (Scheme S1) are 150° in 6 and 153° in 7, which are close to the value in pyrazino-tetracyanonaphthacenequinodimethane (TCNNQ) (148°) [7] and are larger than that in tetracyanoanthraquinodimethane (TCNAQ) (145°) 23], indicating that both 6 and 7 are less folded than TCNAQ. Less folding in 6 and 7 is due to the nonbonding steric interactions between cyano groups and the CH units on peri positions on only one side of the TCNQ system.

Single crystal structures of 6 (top) and 7 (bottom). Left: front view; right: side view.

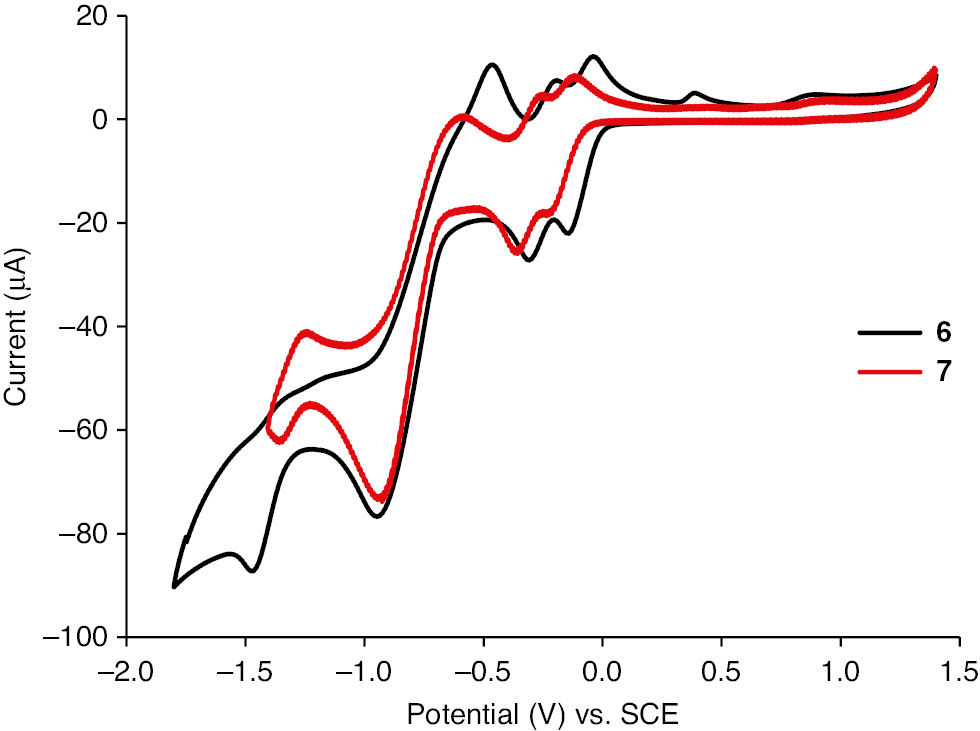

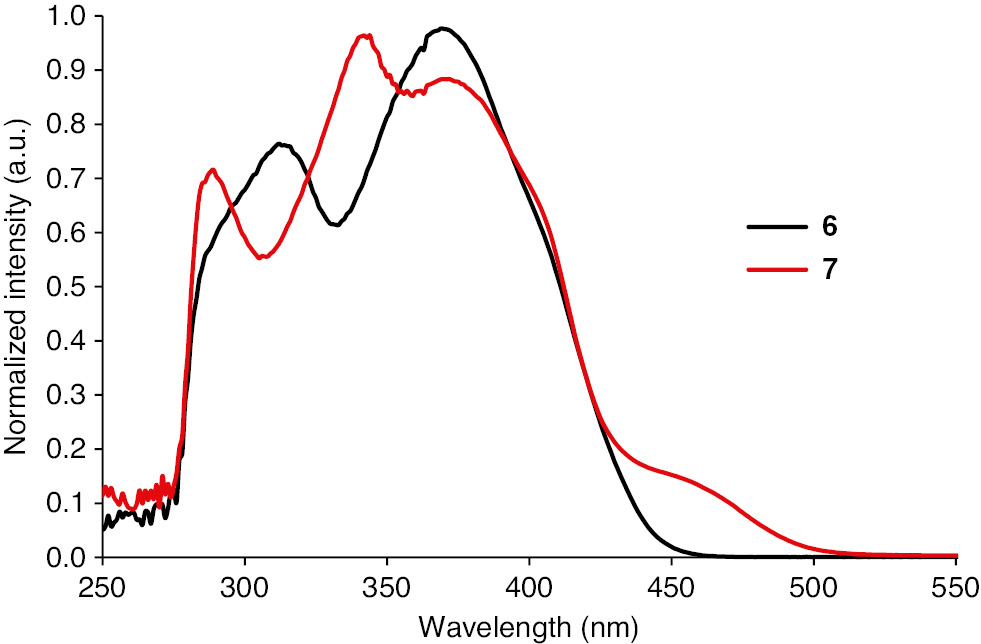

The electrochemical properties of compounds 6 and 7 were studied by CV at room temperature. The half-wave redox potentials are summarized in Table 1. Both compounds exhibit two reversible one-electron reductions to the corresponding radical anion and dianion. The first reduction potentials (E1/21=−0.083 V for 6; E1/21=−0.155 V for 7) are more positive than that for pyrazino-TCNNQ (E1/21=−0.23 V) [[7], indicating the higher electron-accepting properties. The difference between the first and second reduction potentials is bigger than that of pyrazino-TCNNQ (ΔE=0.09 V) [7]. However, it is much smaller than that of TCNQ (ΔE=0.57 V). The low log K values further indicate that anion radicals of 6 and 7 have a poorer stability compared with that of TCNQ. In addition, the third and fourth single wave reductions observed in 6 and 7 can be attributed to the formation of the corresponding radical tri-anion and tetra-anion (Figure 2). The UV-vis absorption spectrum of 6 in hexanes is very similar to that of pyrazino-TCNNQ (Figure 3). The longest wavelength absorption at 369 nm is red-shifted compared with that of pyrazino-TCNNQ. Compound 7 in hexanes absorbs at 289 nm, 344 nm and 372 nm with a shoulder at 460 nm, and shows a bathochromic shift compared with TCNNQ 24]. The LUMO energy levels of 6 and 7 were estimated to be −4.36 eV and −4.29 eV, respectively, based on the potentials of the first reduction (Table 1). The HOMO energy levels were estimated to be −7.72 eV and −6.99 eV, respectively.

Absorption maxima, electrochemistry and density functional theory (DFT) calculated energy levels of 6 and 7.

| Compound | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|

| E1/2red1 (V) | −0.083 | −0.155 |

| E1/2red2 (V) | −0.256 | −0.303 |

| LogKa | 2.98 | 2.55 |

| LUMO (eV)b | −4.36 | −4.29 |

| HOMO (eV)c | −7.72 | −6.99 |

| λmax abs (nm) | 369 | 460 |

| Egap (eV)d | 3.36 | 2.70 |

| LUMO (eV)e | −4.4 | −4.2 |

| HOMO (eV)e | −7.5 | −7.1 |

| Egap (eV)e | 3.1 | 2.9 |

aLog K=ΔE/0.058, K is the constant for the equilibrium A+A2−=A−. bCalculated from cyclic voltammograms, ELUMO=−(E1/2red1+4.44) eV. cCalculated according to the formula EHOMO=ELUMO – Egap. dOptical band gap, Egap=1240/λmax. eTheoretical calculations and the desilylated model compounds 6a and 7a were used for the calculations to reduce the computation time.

Cyclic voltammetry of compounds 6 and 7. Conditions: 1.0×10−3 mol/L on a glassy carbon electrode in CH2Cl2 with 0.1 mol/L nBu4NBF4 at room temperature, scan at v=100 mV/s. A glassy carbon electrode was the working electrode, a Pt wire was a counter electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as the reference.

Normalized UV-vis absorption spectra of compounds 6 and 7 in hexane solutions.

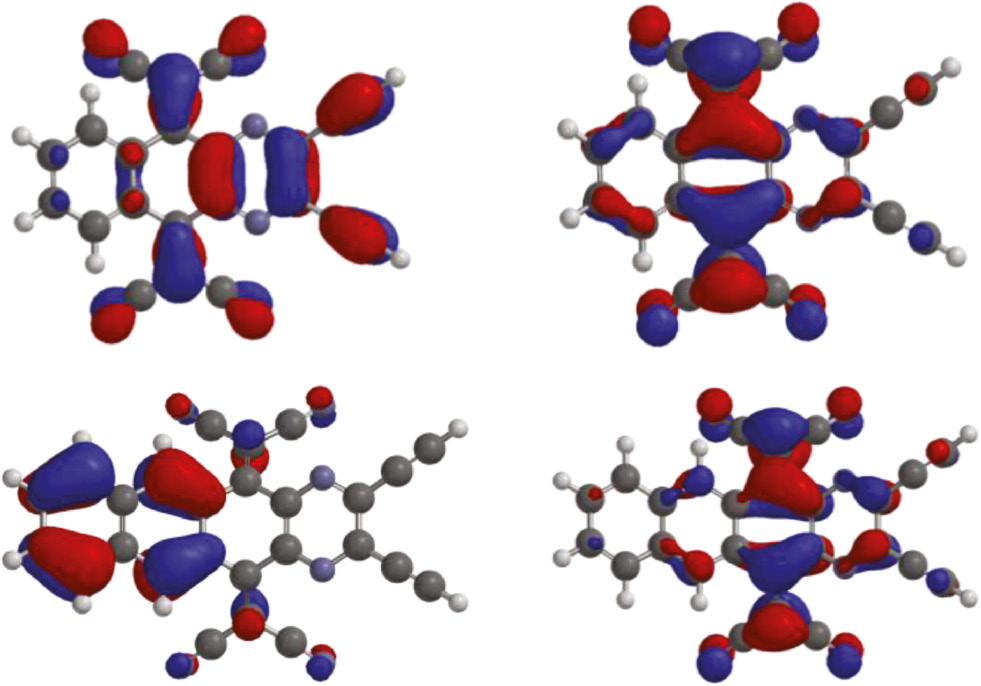

To better understand the electronic structures of 6 and 7, we performed quantum chemical calculations on model compounds 6a and 7a derived from 6 and 7 by replacing triisopropylsilyl groups (TIPS) with hydrogens. The molecular geometries of 6a and 7a were optimized using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311++G** level. Calculated molecular geometries and shapes are in good agreement with the results of X-ray structural analysis. HOMO in 6a is mainly shared between the pyrazine ring and C-C triple bonds, while it is localized on the naphthalene moiety in 7a (Figure 4). LUMO is predominantly localized on the TCNQ moiety in both 6a and 7a. The separated frontier molecular orbitals indicate significant intramolecular charge transfer character [10], [13]. The calculations predict that HOMOs, LUMOs and the band gaps are close to the values found by electrochemical and optical measurements (Table 1). Both theoretical calculations and experimental investigations indicate a significant intramolecular charge transfer nature and high electron-accepting properties.

Frontier molecular orbitals of 6a (top) and 7a (bottom). HOMO, left; LUMO, right.

In summary, we synthesized less symmetrical π-extended TCNQ derivatives under mild conditions in good yields. Theoretical calculations and experimental results indicate that they have a significant intramolecular charge transfer nature and high electron-accepting properties.

Experimental

1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova 400 spectrometer in CDCl3 solution. Distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer 13C-NMR spectra of 5–7 were recorded. Infrared spectra were recorded using KBr pellets on a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) 650 spectrophotometer. Absorption spectra were recorded on a Hitachi U-4100 spectrophotometer. Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis was performed on a Bruker D8 QUEST diffractometer. HRMS data (ESI) were obtained using a Thermo Fisher Q Exactive mass spectrometer. Melting points were determined using a melting point apparatus MEL-TEMP (Thermo Scientific) and are uncorrected. Pyridine and TiCl4 were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd. Malononitrile was purchased from Xiya Chemicals. Bis(triisopropylsilyl)-dialkynyl-l,2-dione [20], 2,3-diamino-1,4-naphthalenedione [19] and 2,3-diamino-1,4-anthracenedione [21] were prepared according to the literature. Product separations were performed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using 0.25 mm silica gel 60 Å F254 glass plates.

General procedure for synthesis of compounds 4 and 5

A mixture of 2,3-diamino-1,4-naphthalenedione or 2,3-diamino-1,4-anthracenedione (0.34 mmol), bis(triisopropylsilyl)-dialkynyl-l,2-dione (0.34 mmol) and glacial acetic acid (8 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. After removal of the solvent, the product was purified by TLC eluting with a mixture of dichloromethane and petroleum ether.

2,3-Bis-[(triisopropylsilanyl)ethynyl]-benzo[g]quinoxaline-5,10-dione (4)

Colorless solid; yield 92%; mp 85–87°C; IR: υ 2941, 2889, 2864, 1686, 1593, 1506, 1462, 1356, 1325, 1300, 1219, 1186, 1174 cm−1; 1H NMR: δ 8.40–8.38 (m, 2H), 7.90–7.87 (m, 2H), 1.25–1.12 (m, 42H); 13C NMR: δ 180.3, 144.3, 141.8, 135.1, 133.0, 127.9, 106.2, 102.2, 18.7, 11.4; UV-vis in CH2Cl2: λmax 297, 350 nm. HRMS (ESI). Calcd for C34H46N2O2Si2, [M]+: m/z 570.3100. Found: m/z 570.3102.

2,3-Bis-[(triisopropylsilanyl)ethynyl]-1,4-diazanaphthacene-5,12-dione (5)

Yellow solid; yield 95%; mp 216–218°C; IR: υ 3068, 2941, 2887, 2864, 1689, 1616, 1583, 1506, 1454, 1398, 1348, 1300, 1232, 1176, 1134 cm−1; 1H NMR: δ 8.95 (s, 2H), 8.15 (dd, 2H, J=6.2 Hz, 3.3 Hz), 7.77–7.75 (dd, 2H, J=6.2 Hz, 3.3 Hz), 1.27–1.17 (m, 42H); 13C NMR: δ 180.2, 144.3, 142.6, 135.4, 130.7, 130.4, 130.3, 129.0, 106.2, 102.3, 18.7, 11.4; UV-vis in CH2Cl2: λmax 310, 356, 368 nm. HRMS (ESI). Calcd for C38H48N2O2Si2, [M]+: m/z 620.3256. Found: m/z 620.3262.

General procedure for synthesis of compounds 6 and 7

Compound 4 or 5 (0.12 mmol), malononitrile (0.48 mmol), pyridine (3.8 mmol) and dry CH2Cl2 (20 mL) were charged into a 50-mL three-neck flask in an ice bath. A solution of TiCl4 (0.22 mL, 2.0 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) was then added dropwise while stirring at 0°C. With the addition of TiCl4 the mixture became greenish and turned brown on completion of the reaction. The mixture was poured into ice water and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3×10 mL). The combined extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was purified by TLC eluting with a mixture of dichloromethane and petroleum ether.

2-{10-Dicyanomethylene-2,3-bis-[(triisopropylsilanyl)ethynyl]-10H-benzo[g]quinoxalin-5-ylidene}malononitrile (6)

Yellow solid; yield 87%; mp 264–266°C; IR: υ 2943, 2891, 2866, 2221, 2156, 1630, 1562, 1506, 1462, 1427, 1367, 1336, 1296, 1188 cm−1; 1H NMR: δ 8.46 (dd, 2H, J=6.0 Hz, 3.3 Hz), 7.82 (dd, 2H, J=6.0 Hz, 3.3 Hz), 1.24–1.16 (m, 42H); 13C NMR δ 153.2, 141.5, 139.2, 133.4, 128.8, 128.5, 113.6, 111.9, 107.7, 101.5, 85.9, 18.6, 11.2; UV-vis in CH2Cl2: λmax 312, 369 nm. HRMS (ESI). Calcd for C40H46N6Si2, [M]+: m/z 666.3326. Found: m/z 666.3333.

2-{12-Dicyanomethylene-2,3-bis-[(triisopropylsilanyl)ethynyl]-12H-1,4-diazanaphthacen-5-ylidene}malononitrile (7)

Orange red solid; yield 70%; mp 260–262°C; IR: υ 2941, 2887, 2862, 2220, 2152, 1620, 1551, 1502, 1481, 1460, 1390, 1354, 1325, 1230, 1201, 1186 cm−1; 1H NMR: δ 8.93 (s, 2H), 8.08 (dd, 2H, J=6.1 Hz, 3.3 Hz), 7.81 (dd, 2H, J=6.1 Hz, 3.3 Hz), 1.22–1.16 (m, 42H); 13C NMR: δ 153.9, 141.6, 139.9, 133.6, 131.1, 130.5, 129.6, 124.3, 114.0, 112.1, 107.7, 101.5, 84.8, 18.6, 11.2; UV-vis in CH2Cl2: λmax 289, 344, 372, 460 nm. HRMS (ESI). Calcd for C44H48N6Si2, [M]+: m/z 716.3482. Found: m/z 716.3491.

X-ray crystallography

X-ray intensity data were collected using a Bruker D8 QUEST diffractometer equipped with a PHOTON 100 CMOS area detector and an Incoatec microfocus source (Mo Kα radiation, λ=0.71073 Å, 100 K). The raw area detector data frames were reduced and corrected for absorption effects using the SAINT+ and SADABS programs [25]. The structures were solved by direct methods with SHELXT [26], [[27]. Subsequent difference Fourier calculations and full-matrix least-squares refinement against F2 were performed with SHELXL-2014 26], [[27] using OLEX2 28]. Single crystals of 4 were obtained by slow concentration of solution in dichloromethane/hexanes as light-yellow plates with crystal sizes 0.52×0.38×0.30 mm; single crystals of 6 were obtained by concentration of solution in benzene as yellow blocks with crystal sizes 0.21×0.20×0.20 mm; single crystals of 7 were obtained by concentration of solution in dichloromethane/methanol as orange needles with crystal sizes 0.44×0.08×0.06 mm. One equivalent of benzene from the crystallization solvent was found co-crystallized with compound 6 in the asymmetric unit of the unit cell. Crystal data, data collection parameters and results of the analyses for compounds 4, 6, 7 are listed in Table 2. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms of the phenyl rings and isopropyl groups were placed in geometrically idealized positions and refined as standard riding atoms.

Crystallographic data for compounds 4, 6 and 7.

| Compound | 4 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C34H46N2O2Si2 | C40H46N6Si2·C6H6 | C44H48N6Si2 |

| Formula weight | 570.91 | 745.12 | 717.06 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Triclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | P21/c | P-1 | P-1 |

| a (Å) | 7.4937(5) | 8.092(3) | 12.0450(6) |

| b (Å) | 12.5218(8) | 11.160(5) | 12.6763(7) |

| c (Å) | 35.441(2) | 25.111(11) | 27.6185(15) |

| α (°) | 90 | 77.737(5) | 91.900(2) |

| β (°) | 90.088(2) | 88.384(5) | 93.367(2) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 84.251(5) | 101.301(2) |

| V (Å3) | 3325.5(4) | 2204.8(16) | 4123.8(4) |

| Z value | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Temperature (K) | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) |

| No. observed (I>2σ(I)) | 7804 | 7690 | 14722 |

| No. parameters | 462 | 487 | 1036 |

| Goodness of fit GOFa | 1.070 | 1.013 | 1.020 |

| Residualsa: R1; wR2 | 0.0377; 0.0936 | 0.0743; 0.2009 | 0.0551; 0.1448 |

aR=Σhkl(||Fobsd|−|Fcalcd||)/Σhkl|Fobsd|; Rw=[Σhklw(|Fobsd|−|Fcalcd|)2/ΣhklwFobsd2]1/2, w=1/σ2(Fobsd); GOF=[Σhklw(|Fobsd|−|Fcalcd|)2/(ndata−nvari)]1/2.

Supplementary material (online only)

Spectral and structural data for the synthesized compounds.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-21271070), Funder Id: 10.13039/501100001809 and the Department of Chemistry and Physics at Augusta University. We thank Dr. Chad Stephens for helpful discussions.

References

[1] Melby, L. R.; Harder, R. J.; Hertler, W. R.; Mahler, W.; Benson, R. E.; Mochel, W. E. Substituted quinodimethanes. II. Anion-radical derivatives and complexes of 7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane. J. Am. Chem. Soc.1962, 84, 3374–3387.10.1021/ja00876a029Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gómez, R.; Seoane, C.; Segura, J. L. The first two decades of a versatile electron acceptor building block: 11,11,12,12-tetracyano-9,10-anthraquinodimethane (TCAQ). Chem. Soc. Rev.2007, 36, 1305–1322.10.1039/b605735gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Jain, R.; Kabir, K.; Gilroy, J. B.; Mitchell, K. A. R.; Wong, K. C.; Hicks, R. G. High-temperature metal-organic magnets. Nature2007, 445, 291–294.10.1038/nature05439Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Alves, H.; Molinari, A. S.; Xie, H.; Morpurgo, A. F. Metallic conduction at organic charge-transfer interfaces. Nat. Mater.2008, 7, 574–580.10.1038/nmat2205Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Bader, M. M.; Pham, P.-T. T.; Nassar, B. R.; Lin, H.; Xia, Y.; Frisbie, C. D. Extended 7,7,8,8-tetracyano-p-quinodimethane-based acceptors: how molecular shape and packing impact electron accepting behavior. Cryst. Growth Des.2009, 9, 4599–4601.10.1021/cg900939cSuche in Google Scholar

[6] Tsubata, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Mukai, T.; Miyashi, T. Tetracyanoquinodimethanes fused with 1,2,5-thiadiazole and pyrazine units. Heterocycles1992, 33, 337–348.10.3987/COM-91-S44Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Suzuki, T.; Miyanari, S.; Kawai, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Fukushima, T.; Miyashi, T.; Yamashita, Y. Pyrazino-tetracyanonaphthoquinodimethanes: sterically deformed electron acceptors affording zwitterionic radicals. Tetrahedron2004, 60, 1997–2003.10.1016/j.tet.2004.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Ye, Q.; Chi, C. Recent highlights and perspectives on acene based molecules and materials. Chem. Mater.2014, 26, 4046–4056.10.1021/cm501536pSuche in Google Scholar

[9] Ye, Q.; Chang, J.; Huang, K.-W.; Dai, G.; Chi, C. TCNQ-embedded heptacene and nonacene: synthesis, characterization and physical properties. Org. Biomol. Chem.2013, 11, 6285–6291.10.1039/c3ob40796aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Ye, Q.; Chang, J.; Huang, K.-W.; Dai, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.-K.; Wu, J.; Chi, C. Incorporating TCNQ into thiophene-fused heptacene for n-channel field effect transistor. Org. Lett.2012, 14, 2786–2789.10.1021/ol301014dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Brown, A. R.; de Leeuw, D. M.; Lous, E. J.; Havinga, E. E. Organic n-type field-effect transistor. Synth. Met.1994, 66, 257–261.10.1016/0379-6779(94)90075-2Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Handa, S.; Miyazaki, E.; Takimiya, K.; Kunugi, Y. Solution-processible n-channel organic field-effect transistors based on dicyanomethylene-substituted tetrathienoquinoid derivative. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2007, 129, 11684–11685.10.1021/ja074607sSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Martin, N.; Segura, J. L.; Seoane, C.; Cruz, P. D. l.; Langa, F.; Orti, E.; Viruela, P. M.; Viruela, R. Synthesis and characterization of 11,11,12,12-tetracyano-1,4-anthraquinodimethanes (1,4-TCAQs): novel electron acceptors with photoinduced charge-transfer properties. J. Org. Chem.1995, 60, 4077–4084.10.1021/jo00118a025Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Yi, H. T.; Chen, Z.; Facchetti, A.; Podzorov, V. Solution-processed crystalline n-type organic transistors stable against electrical stress and photooxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater.2016, 26, 2365–2370.10.1002/adfm.201502423Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Xie, J.; Shi, K.; Cai, K.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.-Y.; Pei, J.; Zhao, D. A NIR dye with high-performance n-type semiconducting properties. Chem. Sci.2016, 7, 499–504.10.1039/C5SC03045ESuche in Google Scholar

[16] Zhang, C.; Zang, Y.; Gann, E.; McNeill, C. R.; Zhu, X.; Di, C-A.; Zhu, D. Two-dimensional π-expanded quinoidal terthiophenes terminated with dicyanomethylenes as n-type semiconductors for high-performance organic thin-film transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2014, 136, 16176−16184.10.1021/ja510003ySuche in Google Scholar

[17] Yan, H.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Newman, C.; Quinn, J. R.; Dötz, F.; Kastler, M.; Facchetti, A. A high-mobility electron-transporting polymer for printed transistors. Nature2009, 457, 679−686.10.1038/nature07727Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Zhao, Y.; Di, C.; Gao, X.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Zhu, D. All-solution-processed, high-performance n-channel organic transistors and circuits: Toward low-cost ambient electronics. Adv. Mater.2011, 23, 2448−2453.10.1002/adma.201004588Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Miao, S.; Brombosz, S. M.; Schleyer, P. V. R.; Wu, J. I.; Barlow, S.; Marder, S. R.; Hardcastle, K. I.; Bunz, U. H. F. Are N,N-dihydrodiazatetracene derivatives antiaromatic? J. Am. Chem. Soc.2008, 130, 7339–7344.10.1021/ja077614pSuche in Google Scholar

[20] Faust, R.; Weber, C.; Fiandanese, V.; Marchese, G.; Punzi, A. One-step synthesis of dialkynyl-1,2-diones and their conversion to fused pyrazines bearing enediyne units. Tetrahedron1997, 53, 14655–14670.10.1016/S0040-4020(97)01007-7Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Appleton, A. L.; Miao, S.; Brombosz, S. M.; Berger, N. J.; Barlow, S.; Marder, S. R.; Lawrence, B. M.; Hardcastle, K. I.; Bunz, U. H. F. Alkynylated aceno[2,1,3]thiadiazoles. Org. Lett.2009, 11, 5222–5225.10.1021/ol902156xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] CCDC 1540124, 1517857, 1540125 contains the crystallographic data for this paper. The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Schubert, U.; Hunig, S.; Aumuller, A. Zur frage der planarität von 9, 10-anthrachinonderivaten. Liebigs Ann. Chem.1985, 1985, 1216–1222.10.1002/jlac.198519850612Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Martin, N.; Behnisch, R.; Hanack, M. Syntheses and electrochemical properties of tetracyano-p-quinodimethane derivatives containing fused aromatic rings. J. Org. Chem.1989, 54, 2563–2568.10.1021/jo00272a020Suche in Google Scholar

[25] APEX2 Version 2014.9-0, SAINT+ Version 8.34A and SADABS Version 2014/4; Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems, Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Sheldrick, G. M. Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8.10.1107/S2053273314026370Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112–122.10.1107/S0108767307043930Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L. J.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst.2009, 42, 339–341.10.1107/S0021889808042726Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hc-2018-0136).

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Preliminary Communications

- Antioxidant, α-glucosidase inhibitory and in vitro antitumor activities of coumarin-benzothiazole hybrids

- Synthesis and properties of tetracyanoquinodimethane derivatives

- Research Articles

- Synthesis, characterization and computational studies of 2-cyano-6-methoxybenzothiazole as a firefly-luciferin precursor

- Synthesis of fluorine-containing phthalocyanines and investigation of the photophysical and photochemical properties of the metal-free and zinc phthalocyanines

- Copper-catalyzed synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted quinazolin-4(3H)-ones from benzyl-substituted anthranilamides

- Synthesis and mass spectrometric fragmentation pattern of 6-(4-chlorophenyl)-N-aryl-4-(trichloromethyl)-4H-1,3,5-oxadiazin-2-amines

- An efficient cascade synthesis of substituted 6,9-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-f]quinoline- 8-carbonitriles

- Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of isoxazole-substituted 1,3,4-oxadiazoles

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Preliminary Communications

- Antioxidant, α-glucosidase inhibitory and in vitro antitumor activities of coumarin-benzothiazole hybrids

- Synthesis and properties of tetracyanoquinodimethane derivatives

- Research Articles

- Synthesis, characterization and computational studies of 2-cyano-6-methoxybenzothiazole as a firefly-luciferin precursor

- Synthesis of fluorine-containing phthalocyanines and investigation of the photophysical and photochemical properties of the metal-free and zinc phthalocyanines

- Copper-catalyzed synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted quinazolin-4(3H)-ones from benzyl-substituted anthranilamides

- Synthesis and mass spectrometric fragmentation pattern of 6-(4-chlorophenyl)-N-aryl-4-(trichloromethyl)-4H-1,3,5-oxadiazin-2-amines

- An efficient cascade synthesis of substituted 6,9-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-f]quinoline- 8-carbonitriles

- Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of isoxazole-substituted 1,3,4-oxadiazoles