Chinese Education in the United States: Players and Challenges

Abstract

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, China has emerged as the second largest economy in the world. In the U.S., Chinese speakers became the second largest non-English-speaking population, and Chinese education obtained unprecedented opportunities in both the K-12 school system and higher education. Various players have contributed to this development, with the major ones being (1) the U.S.-government funded National Security Language Initiatives (NSLI), (2) the long existing Chinese community heritage language schools, and (3) China’s Confucius Institute (CI) program. The NSLI has created a number of meaningful projects such as the Foreign Language Assistance Program, the Teacher Exchange and Summer Language Institutes Youth Exchanges, the Flagship Program, and STARTALK, in which the Chinese language is the focus. The Chinese community heritage language schools have a history of over 150 years in the U.S. and are enrolling 200,000 Chinese students (estimated), more than the U.S. K-12 schools and higher education combined. China’s CI program has established 97 CIs and 357 Confucius classrooms in the U.S., which have reached millions of American people and students. However, the present data show that there lacks a coherent language policy in the U.S. education system. Although the above players have joined forces and made great contributions to the development of U.S. Chinese education, each of them is facing significant challenges. On the one hand, NSLI and Chinese community heritage language schools are both on the sidelines of the American public school system. On the other, with CI’s fast expansion, concerns and criticisms grow regarding its role in the context of U.S. higher education. Some of the concerns have been translated into negative actions and policies.

1 Introduction

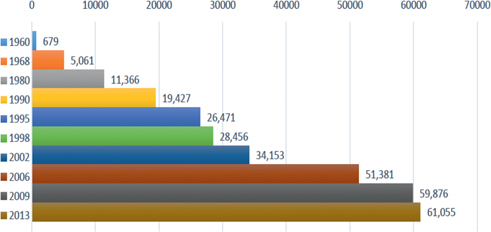

Chinese immigration to the U.S. has a history of over 150 years, marked with ups and downs. It started with 4,018 persons (0.02 % of the U.S. population) migrating in 1850 [1] and has grown to be the second largest non-English-speaking population in this country by 2010, only after Spanish. The U.S. Census 2010 [2] reported a total of 3,794,673 persons of Chinese origin, forming 1.23 % of the U.S. population and indicating a 7.24 % increase over the year 2007 (3,538,407 in total). The growth of Chinese language in the American education system has followed suit. It was unknown to the American public until the late 1950s, when Yale and Harvard Universities established research centers on Eastern Asian languages, and a first lone course – beginning Chinese – was offered in New York Public school system in 1964 (Sung 1967: 5). Subsequently, Chinese language education was twice placed as the top U.S. priority for federal funds and scholarships: the first was in 1966, after China detonated its first atomic bomb (p. 5), and the second was most recently after China emerged as the second largest economy in the world. China’s first atomic bomb prodded American leaders into realizing that China could not be ignored, and a crash program under the National Defense Education Act was created to provide top priority federal grants and scholarship for studies of China (p. 5). In 1960, 679 students registered in Chinese studies at universities and colleges, and by 1968 the enrollments rose to 5,061 (Goldberg et al. 2015: 23).

Recent years witnessed unprecedented attention to Chinese language in the U.S., which brought about abundant opportunities for individuals to learn Chinese. As a result, there have been large increases of Chinese enrollments, both in the K-12 public system and in higher education. By the ACTFL (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) report (2010), the Chinese enrollment in K-12 public schools increased from 20,292 students (0.23 % of the U.S. total foreign language enrollments) in 2004–2005 to 59,860 (0.67 % of the U.S. total) in 2007–2008. In higher education, Chinese enrollment increased from 28,456 students in 1998 to 61,055 in 2013, indicating a 114.56 % increase (MLA survey 2013). Such changes have inspired numerous applauding commentaries (Xiao 2011; among others) and enthusiastic beliefs such that “it appears clear that the Chinese language education in the United States has continued to explode” (Wang 2010: 4).

Nevertheless, Chinese in the U.S. has been, to date, carrying a cumbersome label of a “less commonly taught language,” evidenced by the prolonged membership of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages (NCOLCTL [3]). Given the outstanding changes shown above, such a label seems puzzling, but it is well justified by the long-time marginal standing in the U.S. education system. According to the ACTFL report (2010), Chinese language instruction is listed in seventh place (by enrollment) in 2004–2005 in the K-12 public school system and remains seventh place in 2007–2008, which is after the “big four” (i. e., Spanish, French, German, and Latin) plus Japanese and Other (e. g., American sign language, Italian). In higher education, Chinese also stays in seventh place over multiple years including 2002 (2.45 % of the total U.S foreign language enrollments), 2006 (3.26 % of the U.S. total), 2009 (3.58 % of the U.S. total), and 2013 (3.91 % of the U.S. total). A horizontal analysis may give a rosy picture of “exploding Chinese education,” but a counterpart comparison would reveal that it has been and continues to be fractional and peripheral in the U.S. education system. It is palpably underrepresented, when compared with Spanish language education, which remains the first place in both higher education and the K-12 school system for decades, taking over 50 % of the U.S. total in higher education and over 72 % in K-12. The common assumption is that Spanish enrollments are speaker-driven, but the Chinese-speaking population has been rapidly chasing after the Spanish, rising from sixth place in 1980 to second in 2010.

Why does the Chinese education remain minimal in the U.S. education system in spite of the increasing speaker population and unprecedented opportunities? Who are the major players in its development? And what are the challenges they are facing? This study intends to seek the answers by drawing on data from three major sources: (1) large-scale surveys by MLA (Modern Language Association) 2013 (Goldberg et al. 2015) and a national survey of U.S. elementary and secondary schools (Pufahl and Rhodes 2011), (2) the ACTFL report (2010) based on the national surveys of U.S. public schools in 2004–2005, 2007–2008, and (3) the Heritage Language Programs Database, managed by the Center of Applied Linguistics (CAL) in the United States.

2 Historical overview

Compared with their European counterparts, Chinese speakers in the U.S. are a relatively new immigrant group, mainly made up of contemporary immigrants arriving around the turn of the twenty-first century. Moreover, Chinese immigrants in the U.S. have been highly concentrated. By 2010, over half of the Chinese immigrants in the United States resided in just two states: California and New York (McCabe 2012), where one finds the largest Chinatowns. California had the largest number of Chinese immigrants in 2010 with 577,745 individuals and 32.0 % of the total Chinese population, followed by New York with 20.8 % of the total.

Historically, there were three major waves of Chinese immigration to the U.S. The first wave started from the 1840s, followed by the second in the mid-twentieth century (1949–1979) and the third from 1980 to the present (Chang 2003). The first-wave pioneers were attracted by the Gold Rush and arrived at the shores of California in the 1840s; they were mostly Cantonese-speaking peasants or fishermen from Toishan, Southern China. Records showed that 40,400 of them arrived in 1851–1860. After their gold mining mission was over, the pioneer Chinese immigrants moved to cities and took on many different service jobs, in which they demonstrated industry and efficiency. Welcomed as “one of the most worthy of newly adopted citizens” (Sung 1967: 27), they were recruited by Central Pacific to build the railroads and soon became its main force. At one time, there were over 10,000 Chinese in the construction (p. 31). The gold they produced created wealth for the country, and the railroads they built connected the continent, linking the West with the East. With such contributions to the early development of the West, Chinese pioneers won high social recognition and wide acceptance. Consequently, there was a rapid growth in the Chinese population. In 1870, there were 63,000 Chinese in the United States, with every tenth person in California being Chinese (Sung 1967: 42).

However, linguistically ill-prepared and culturally under-motivated, characterized by a short-term goal of “making a fortune in a land of foreigners and returning to the homeland,” the Chinese were soon thrown into an unfair situation by being stereotyped as debased and servile coolies, clannish, dangerous, deceitful, and vicious when their employment with the railroad ceased (Sung 1967: 42). During the period of 1880–1924, 14 separate pieces of legislation relating to Chinese exclusion were passed, which had a dynamic and disruptive influence on the lives of Chinese in America and their families in China. The Scott Act in 1888 expressly prohibited Chinese laborers from coming the United States. Almost every year after that, the number of Chinese leaving the United States was greater than the number coming in. In 1887 only 10 Chinese came in, and in 1892 there was zero (p. 52). Seeing no opportunities in the new land, the early immigrants prepared their children to return to China (Koehn and Yin 2002). For this purpose, they started Chinese language schools in Chinatowns, sponsored by Chinese families, local Chinese churches, and Chinese Benevolent associations. The Chinese schools were generally held after regular public school hours from 4 to 6 p.m. or 5 to 7 p.m. daily and from 9 a.m. to 12 noon on Saturday mornings (Sung 1967: 229). Most Chinese parents wanted their children to know the history, culture, and language of their ancestors, and believed that, without some rudiments of the Chinese language, a person would be at a decided disadvantage (p. 229). Ever since, the language school has been a centerpiece of the Chinese-speaking community.

Compared with their first-wave counterparts, the second and third wave arrivals were more educated and financially better off who sought betterment in higher education and skilled professions. They happened to arrive in better environments, improved first by the enactment of new immigration policies in 1965 and then by the normalization of U.S.-Chinese relations and China’s economic reforms in the late 1970s. The second wave arrivals (1949–1979) were mostly from Chinese-speaking regions other than mainland China, such as Taiwan or Hong Kong. Some of them came as refugees to escape the take-over by New China. By 1980, there were 812,178 persons of Chinese origin (0.36 % of the U.S. population) living in the U.S. [4] Conversely, the thirdwave arrivals are mainly from China and include the largest number of Chinese scholars and students in American history, who speak Mandarin Chinese and tend to present themselves in American universities or research institutions (Chang 2003). The number of Chinese students, scholars, and their families who entered the U.S. increased by 50 times in 20 years, from just 1,000 in 1979 to over 50,000 in 1999 (Li 2002). Students from China maintained second place in the number of foreign students in the U.S. for seven consecutive years (2001–2008) (Institute of International Education [5]). In 2008, there were a total of 81,127 students from China, which was 13 % of all U.S. foreign students. The subsequent increases were even faster. In the 2013–2014 academic year alone, there were more than 274,000 students from China, the top place of origin for international students in the U.S., with Chinese students making up 31 % of all U.S. foreign students (Institute of International Education [6]). Moreover, with the speedy development of U.S.–China commerce and trade and the new U.S. visa rules to China [7] in 2013, Chinese visitors are storming into the U.S.; visitors include not only scholars and students but also business professionals, convention attendees, and tourists. Data from the U.S. Travel Association show that there were 1.8 million Chinese arrivals in 2013, which is expected to grow to 3.1 million in 2019, a 172 % increase over 2013 (Willett 2015).

Unlike their pioneer counterparts, who had little or no opportunities for education and skillful jobs in their host country, many of the contemporary Chinese immigrants earned academic degrees in American colleges/universities and obtained professional employment in the mainstream job market. They became doctors, lawyers, CPAs, architects, financial consultants, real estate brokers as well as scientists, college professors, and computer engineers (Chan 2002: 146). Data from Migration Information Source show that in 2010 45.4 % of Chinese immigrants age 25 and older had attained a bachelor’s degree, compared to 27.1 % of the foreign born population overall (McCabe 2012). Moreover, Chinese immigrants (26.1 %) were more likely than the foreign born overall (11.1 %) to have attained a post-bachelor’s-level degree.

Empowered by advanced education and professional occupations, many contemporary Chinese immigrants have passed up Chinatowns and moved directly into mainstream markets. They view America as a land of promise and, instead of sending their children back to their homeland, prepare them for the mainstream language and job skills in the host country, which results in serious Chinese language loss and shift in the younger generations (Xiao 2010, 2011). Nevertheless, Chinese parents desire to carry on the legacy of building and expanding the Chinese language schools, and they have become the major force in maintaining Chinese as a heritage language in the U.S. (See more detailed discussion below.)

3 Chinese language in the global context

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Chinese language has been highly favored and rapidly expanding in the U.S. by new and existing efforts from various players, such as governments (U.S. and China), non-government organizations (Asian Society and College Board, among others), Chinese community heritage language schools, and grass-roots organizations. Chinese language has been, for the second time, made top priority for U.S. government funding and scholarships. The following section will examine the rationale, initiative, and impact of the major players in the new developments of the Chinese language in the U.S.

3.1 Chinese as a critical-need foreign language in the U.S.

With globalization intensifying, the American public, including parents, educators, and business leaders, are awakening to the need for an education system that prepares students for the globalized world and international competition. Chinese language education was thus called for, with 2004 and 2006 as its defining years. In 2004, the College Board conducted a national survey that revealed 2,400 schools expressing interest in offering the Chinese Advanced Placement (AP) Course and Examination (Stewart and Wang 2005: 6). Previously, such AP courses and exams had exclusively belonged to the commonly-taught languages, such as Spanish, French, and German. Moreover, in January 2006 the National Security Language Initiative [8] (NSLI) program was established by the U.S. federal government, as “a plan to further strengthen national security and prosperity in the twenty-first century through education, especially in developing foreign language skills. The NSLI will dramatically increase the number of Americans learning critical-need foreign languages such as Arabic, Chinese, Russian, Hindi, Farsi, and others through new and expanded programs from kindergarten through university and into the workforce” (retrieved in July 2015 from NSLI website). Then President George W. Bush requested $114 million to fund this effort, which was successfully granted. The rationale of this initiative is to deal with the post-9/11 world, with “the ability to engage foreign governments and peoples, especially in critical regions, to encourage reform, promote understanding, convey respect for other cultures and provide an opportunity to learn more about our country and its citizens” (retrieved in July 2015 from NSLI website). Under this auspice, Chinese was designated as one of the “critical-need” languages, and Chinese education in the U.S. has since become the major recipient of U.S. federal funds and resources through NSLI initiatives.

The NSLI program is coordinated by four government branches: the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, each of which navigates various programs to develop the critical-need foreign language proficiency, as outlined below:

The Foreign Language Assistance Program (FLAP), managed by the Department of Education, creates incentives to teach and study critical-need languages in K-12 schools, and provides immersion programs, curriculum development, professional development, and distance learning. In 2009, 58 % of its total funding of $14.1 million was awarded to Chinese language programs. The Teacher Exchange [9] and Summer Language Institutes Youth Exchanges [10] are sponsored by the Department of State programs. While the former provides critical language teachers to U.S. secondary schools by bringing native speaking teachers and providing American teachers in these languages opportunities for intensive summer study abroad, the latter provides U.S. high school students the opportunity to study Arabic or Chinese abroad as well as school partnerships that provide U.S. schools with linkages to foreign counterparts. In both programs, China is a focused country. The Flagship Program [11] operated by the National Security Education Program (NSEP) under the U.S Department of Defense provides advanced instruction in critical languages, which represents a national model for developing a workforce of professionals with superior-level proficiencies in those languages. So far, there are 12 Chinese Flagship programs (44.44 % of the U.S. total) across the states, which have enrolled 1,553 Chinese students in the years of 2010–2013.

STARTALK [12] (literally, Start Talking) sponsored by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence Programs is the “seed” program that provides summer language learning to young students and pedagogical/cultural training to pre/in-service language teachers in the 10 critical languages. From 2009 to 2015, there were a total of 673 student programs and 431 teacher programs across the states, in which Chinese accounted for half of the total in each category and in each year. (See Table 1.)

STARTALK summer programs, 2009–2015.

| Year | Student programs (Chinese/U.S. total) | Teacher programs (Chinese/U.S. total) |

| 2009 | 45/77 (58.44 %) | 33/48 (68.75 %) |

| 2010 | 54/83 (65.06 %) | 44/59 (74.58 %) |

| 2011 | 63/108 (58.33 %) | 49/73 (67.12 %) |

| 2012 | 65/111 (58.56 %) | 47/71 (66.20 %) |

| 2013 | 64/107 (59.81 %) | 50/70 (71.43 %) |

| 2014 | 55/90 (61.11 %) | 40/56 (71.43 %) |

| 2015 | 54/97 (55.67 %) | 38/54 (70.37 %) |

| Total | 400/673 (59.44 %) | 301/431 (69.84 %) |

As shown in Table 1, the Chinese language is the major recipient of the STARTALK program. In most of the years, Chinese teacher programs accounted for two thirds of the total, whose targeted audiences are, in general, current and future Chinese teachers from public/private K-12 and community heritage language schools, with or without teacher certifications.

In general, the Chinese STARTALK programs are scheduled for 4 weeks in the summer, with the first week dedicated to teacher training and the remaining three weeks for student language and cultural learning. Aligned with ACTFL guidelines and the National Foreign Language Standards, the Chinese teacher programs provide training on second language acquisition theories, performance-based activities and assessments, lesson planning and classroom technology. Most of the teacher trainees, after the initial one-week training, engage in teaching practices in the adjoined student programs, which run small language classes at multiple proficiency levels, reinforced with cultural workshops and field trips.

Although it is criticized as a “crisis-response” approach or “languages of the moment phenomenon” (Wang 2010: 11), the NSLI has made undeniable contributions to critical-need language development in the U.S. in recent years and has played a vital role in promoting Chinese education. In a conjoined effort, Asia Society and College Board – the two leading non-government organizations involved in language education – have joined forces to promote Chinese language education. In 2005, Asia Society published a groundbreaking report, entitled Expanding Chinese-language capacity in the United States: What should it take to have a 5 percent of high school students learning Chinese in 2015? It addressed various critical issues in developing the Chinese education and called for a number of actions, such as creating a supply of qualified Chinese-language teachers, increasing the number and quality of school programs, and developing appropriate curricula, materials and assessments (Stewart and Wang 2005: 4). The report was highly influential and largely raised awareness of Chinese education to the American public. It also made the first call to introduce China’s Hanban [13] 汉办(The National Office on the Teaching of Chinese as a Foreign Language, then abbreviated as NOCTFL) and its visiting faculty program to the U.S. (p. 10). Ever since, Hanban has been playing a significant role in U.S. Chinese education.

Coupled with Asia Society’s call for qualified Chinese teachers, the College Board created a Chinese guest teacher and trainee program, [14] through a collaboration with Hanban (called “the Office of Chinese Language Council International” at the present time). Since 2007, this program has brought more than 900 Chinese language and culture teachers to classrooms across the nation and has grown to be the largest Chinese visiting teacher program in the U.S. Each year, the program serves hundreds of K–12 schools and districts nationwide and reaches tens of thousands of U.S. Chinese students.

Collectively, these efforts have largely boosted Chinese education in the U.S. As shown in Figure 1, Chinese higher education made outstanding changes in 2006 with total enrollments of 51,381 students, indicating a 50.44 % increase over 2002 (34,153 students in total), followed by a 16.53 % increase in 2009 over 2006. In 2013, a large number of foreign language enrollments in the U.S. higher education (i. e., Spanish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, among others) significantly dropped, while Chinese exclusively gained 2 % over 2009 (Goldberg et al. 2015).

Chinese enrollments in higher education, 1960–2013.

3.2 Chinese as a community heritage language in the U.S.

Chinese education in the U.S. has operated in two major separate fields: the mainstream system and the community heritage language schools. Unlike the mainstream school system where Chinese was almost unknown until recent decades, the Chinese heritage language schools have been the centerpiece of the Chinese community for over 150 years (see Section 2). Data show that almost all U.S.-born Chinese children or young arrivals have some level of experience in Chinese community schools (Xiao 2008), where they learn the heritage language and culture, make friends, and weave ethnic fabrics with holiday celebrations, special gatherings, talent shows, etc. The first Chinese heritage language school was established in San Francisco in 1886 (Liu 2010), with Cantonese as the major medium of instruction, and classic written Chinese texts as the teaching materials. By the end of the 1920s, there were over fifty Chinese-language schools, with most of them in the western states (Chang 2003). However, they were in general independent of each other, without interaction or collaboration. In 1994, two non-profit organizations were established to serve and lead. One of them is the National Council of Associations of Chinese Language Schools 全美中文學校聯合總會 (NCACLS [15]), established by immigrants from Taiwan, and the other is the Chinese School Association in the United States 全美中文学校协会 (CSAUS [16]), established by people from China. Each of these two organizations has its own affiliated member schools and lends them support in curricula development, mainstream communication, advocacy, and articulation. By 1996, approximately 82,675 students were enrolled in 634 Chinese language schools across the country (Chao 1997). At the present time, it is estimated that 200,000 students are enrolling in these schools, with NCACLS claiming to have close to 100,000 students across 47 U.S. states, and CSAUS having 100,000 students across 50 U.S. states, affiliated with more than 500 member schools.

Although they are managed by leaders from different origins, both organizations share a mission of promoting and cultivating the Chinese language and culture in the U.S. NCACLS aims to serve as the primary contact for national and/or international institutions on Chinese language and culture and provides a forum to share and exchange experience and information for its affiliated member schools. It has organized a number of student contests, teacher training workshops, and the first annual Conference for Chinese Heritage Education (Detroit, Michigan, in August 2015). In a similar vein, CSAUS aims to help younger generations preserve and appreciate Chinese heritage and strives to facilitate educational and cultural exchanges between the United States and China; CSAUS has successfully organized nine national conferences with feature speakers from both China and the U.S.

In addition to the organization-led Chinese heritage language schools mentioned above, there are “community-based” heritage language schools, which were created and managed by immigrant families and/or religious institutions. Thus, Chinese heritage schools are treated as two separate datasets (i. e., organization-based and community-based) in the Heritage Language Programs Database [17] managed by CAL. The database collects and publicizes school profiles (apparently from voluntary submissions), which include a number of measures, such as program description, language being offered, student background and enrollments, instruction and instructor, materials being used, funding sources, challenges being faced, etc.

A search on the Organization-based dataset showed 23 entries, with NCACLS and CSAUS being listed as two lone entries without linkage to any of their member schools. Also, some schools listed in organization-based section claim their own organizations such as Huaxia Chinese language schools 华夏中文学校 and American Chinese Schools 美中实验学校, and some of their member schools are also listed in the “community-based” dataset. Given the developing information of the “organization-based” dataset, the researcher resorted to the “community-based” dataset for data analysis, which consists of 191 entries with specific school names and locations. Two of the entries were eliminated for data analysis: one is a STARTALK summer program, and the other a repetition. Data from the remaining 189 schools from 28 states are used for computation and analysis. (See Figure 2.)

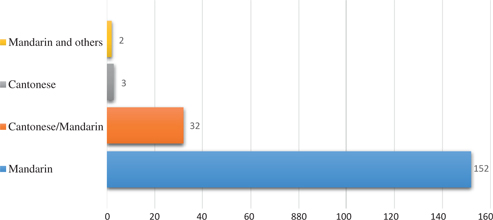

Languages offered by community-based Chinese heritage language schools.

As shown in Figure 2, out of the 189 community-based schools, 152 offer Mandarin (80.42 % of the total), 32 (16.93 %) offer Cantonese and Mandarin, 3 (1.59 %) offer Cantonese, and 2 (1.06 %) offer Mandarin and others such as Arabic, Hindi, and Tamil. Regionally, 63 of the 189 schools are in California (33.33 % of the total), out of which 3 offer Cantonese (100 % of the total) and 21 offer Cantonese/Mandarin (65.63 % of the total). Moreover, 48 schools were selected as Chinese Education Model Schools in the U.S. by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council, China, in 2009 and 2011. Out of them, 40 were selected in 2009, which included Huaxia Chinese Schools 华夏中文学校 (27 campuses), Hope Chinese Schools 希望中文学校 (6 campuses), Atlanta Contemporary Chinese Academy 亚特兰大现代中文学校 (4 campuses), Xilin Chinese Schools 希林中文学校 (2 campuses), and Nam Kue School 旧金山南侨学校 (San Francisco, CA). The remaining 8 were selected in 2011: American Chinese Schools 美中实验学校 (6 campuses) and Ray Chinese Schoo1 瑞华中文学校 (2 campuses).

The majority of the 189 respondents claim to be 501(c) (3) nonprofit organizations which allows them to seek and receive tax-free donations. Except for three, none of these schools have its own teaching quarters, but rent from local schools or churches. The three exceptions are Nam Kue School in San Francisco, CA; Shoong Chinese School in Oakland, CA; and Tucson Chinese School, AZ. The Nam Kue School was established in 1920 and acquired its own building and lot in 1926 through donations from the local Chinese community. The school evolved from a small class with one teacher and 35 students to a large educational institution of more than 1,700 students at the present time. Shoong Chinese School was established by the Shoong family in the late 1940s, and in 1953 it moved into the Shoong family Chinese Cultural Center in Oakland, CA. Tucson Chinese School was also established over 50 years ago, and in 2005 it moved into the Tucson Chinese Cultural Center and became a local Chinese school with excellent facilities.

Moreover, according to the information provided in the database, the instruction time of these schools ranges from 1 hour to 4 hours per week; students range in ages from 3 to 18, or pre-K to 12; and instructors are all part-timers. Student enrollments range from 80 per school (i. e., The Yen Wulin Alaska Chinese School, AK) to 1,700 (i. e., The Nam Kue School), with 300–400 students as the norm. Curriculum-wise, these schools are extremely diverse and open. Besides Chinese language teaching, they engage students in a wide range of cultural activities such as Chinese chess, dance, painting, calligraphy, martial arts, Taiqi, and opera; among others. Some of the schools also administer the Hanban-authorized Chinese standardized tests, prepare students for SAT or SAT II Chinese and/or math, and organize Chinese summer camps, festival celebrations, and cultural exchanges.

In the entry that asks for “Program Funding,” all of the respondents claim “student tuition,” including the 48 schools that were selected as China’s overseas education models by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council in 2009 and 2011. The typical tuition these schools charge is $200-$250 per semester. On top of the student tuition, some schools obtain “donations from local business companies, parents, churches, or adjacent college student activity funds.” Only two of them (i. e., Chinese School of Delaware and Columbus Chinese Academy, OH) mention “home government (Taiwan) financial support” on top of student tuition and help from the local community. The Columbus Chinese Academy also claims that the textbook used is published by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission (OCAC), Taiwan. In the entry of “challenges faced by the program,” adversities includes insufficient funding, unaffordable facility rentals, dearth of resources for curriculum design and training for teachers who are in general parent volunteers and part-timers (with full-time jobs elsewhere), scarcity of appropriate textbooks, and students’ lack of interest, among others. As the evidence provided above indicates, the Chinese heritage language schools in the U.S. have accommodated large enrollments of Chinese students, more than the American public schools and higher education combined, but have been facing many challenges. They are entirely grass-roots efforts, with zero support from the U.S. mainstream system. Moreover, the majority of the community-based schools offer Mandarin Chinese, while the other Chinese languages/dialects are unknown except for Cantonese, which has a marginal presence, mostly in California. In addition, one third of the community-based schools (33.33 %) are in California; schools that offer Cantonese alone are in California; and two thirds of the schools that offer Cantonese/Mandarin are also in California. Such linguistic distribution reflects on the history of Chinese immigration, which started in California by Cantonese-speaking pioneers and expanded into the hub of Chinese immigration, where one finds the most, oldest, and largest community-supported Chinese heritage schools in this country.

3.3 Chinese language as China’s soft power in the U.S.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, China successfully built up its economic hard power as the second-largest economy (in GDP and foreign trading) in the world and the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury Bonds (a total of $1,202.8 billion by the end of 2012, 21.7 % of the total U.S. foreign holding) (Kennedy and Fan 2013: 17). In the meantime, the nation was awakening to the need of increasing the country’s soft power, the ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction or “a form of power, one way of getting desired outcomes (Nye 2011: 82)”. In November 2006, China’s then President Hu Jintao brought the “soft power” concept to the nation. [18] One year later, the notion of “increasing the soft power of Chinese culture” was put on the government’s agenda (Xinhua News Agency 2007) and repeatedly emphasized by Hu on several occasions (e. g., January 22th, 2008; October 18th, 2010; July 1st, 2011). On October 18th, 2011, at the Party’s Central Committee convention, President Hu again called for “striving to build a strong socialist country through connecting the world and enhancing its cultural soft power 面向世界, 增强国家文化软实力,努力建设社会主义文化强国,” which was warmly received and factored into the nation’s strategic plan. The effort continued and intensified after Xi Jinping succeeded to Hu in China’s presidency (Xinhua Net, December 31, 2013 [19]). In fact, long before the “soft power” concept was brought to light, the teaching of Chinese as a foreign language (TCFL) was promoted by the country as an important source of soft power. In the 1950s and 1960s, TCFL served to build up international relations by mainly working with the Third World countries such as Vietnam and some African countries (Zhao and Huang 2010: 130). In 1985, four top-notch Chinese universities established academic departments in TCFL, which was soon followed by many other universities (Ministry of Education 2005). By the end of 2012, there were 63,933 students majoring in TCFL in the country, and at the present time 342 universities offer Bachelor’s, Master’s, or doctoral degrees in TCFL (China Daily ChineseNet [20] on May 5, 2014). A large number of these trained CFL teachers come overseas. In the U.S., they arrive basically in three channels: (1) sent over by Hanban through the Confucius Institute program, (2) recruited by the Guest Teacher Program co-sponsored by the College Board and Hanban, and (3) admitted into Chinese graduate programs in American universities and become permanent Chinese teachers in K-12 schools or lecturers/professors in universities.

Since 1987, when China’s CFL policy stepped up into a significant stage through Hanban, which involved 11 ministries of the central government (Zhao and Huang 2010: 131), Hanban has become the chief agent of promoting TCFL through various vehicles such as 汉语桥 ‘Chinese Bridge Proficiency Contests’,汉语水平考试 ‘Chinese Proficiency Test’,汉语志愿教师计划 ‘Chinese volunteer teacher program’, 奖学金 ‘scholarships’,交流合作 ‘exchange and cooperation’,教学资料 ‘teaching materials’,and 孔子学院 ‘Confucius Institute (CI)’. Out of them, the CI program is the key one. Since its inception in 2004, CI has rapidly expanded throughout the world with its global promotion of Chinese language and culture. Although “soft power” is not declared in its mission statement or funding principles, CI has been playing an important role in China’s soft power campaign, because through CIs “tens of thousands of Chinese teachers are sent abroad each year, and each of them is a business card of China,” stated Ms. Xu Lin, the Director-General of CI headquarters, at a press conference on March 14, 2014. [21]”

By August 2015, there have been 443 CIs and 648 Confucius Classrooms (CCs) in 126 countries/regions in the world. As the sole superpower in the world, the United States has the most CIs and CCs in North America and in the world as well. Since its first CI being established in the University of Maryland in November 2004, the U.S. now has a total of 97 CIs and 357 Confucius Classrooms (CCs), more than one fifth of the world total of CIs (21.90 %) and over half of the CCs (55.09 %). In the meantime, each of the remaining continents has a major power partner that has the most CIs and CCs: the UK in Europe (25 CIs and 92 CCs), Australia in Oceania (13 CIS and 35 CCs), South Korea in Asia (20 CIs and 4 CCs), and South Africa in Africa (5 CIs and 3 CCs).

As stated in its founding principles, [22] the CI program is committed to teaching and spreading the Chinese language and to strengthening educational and cultural exchange and cooperation between China and other countries. A survey of 24 U.S. CIs (conducted in fall 2009 and spring 2010) showed that these institutes primarily focused on Chinese language teaching, teacher education, as well as academic and cultural events (Li and Tucker 2013: 29). Among the 23 CIs that offered Chinese language and cultural courses, 17 targeted K-12 schools, 16 targeted universities, and 13 targeted the general public (p. 36). Besides language teaching, the CIs also provide a variety of cultural activities. At the researcher’s university, the CI opens to the general public with non-credit Chinese language classes (for business professionals or young children), Chinese tea workshops, celebrations for Chinese Moon Festivals, Spring Festivals; and also conducts activities on campus such as monthly China briefing series, non-credit adult evening Chinese classes, Dragon Dance, Taiqi, tennis, and Chinese tutorial sessions, among others. It has also sponsored nine CCs with funding, curricular consultation, and materials in neighboring public schools. Most of these CI-sponsored activities and classes are free, or at a very low cost, such as $40 per semester for an adult evening class. Nevertheless, the CI does not interact/coordinate with Chinese community heritage language schools, nor does it provide any financial or curricular support for these schools.

As discussed above, there is a close connection between China’s rise and its worldwide promotion of Chinese language learning. In the U.S., Chinese language is employed as an important source to increase China’s soft power by means of the hundreds of CIs and CCs. Through collaboration with K-12 public schools and universities, the CI program has reached millions of American people and students. However, unlike the early TCFL program that focused on underdeveloped/developing countries, the current TCFL through CIs is taking a “mainstream approach” 高端路线 gaoduan luxian that favors major developed powers over developing countries and chooses public schools and universities over the marginalized community heritage language schools.

4 Challenges facing the major players of Chinese education in the U.S.

Although there have been abundant opportunities for U.S. Chinese education in recent years, the ACTFL report (2010) shows that only 18.51 % (close to 9 million) of the 48 million American public school students are enrolling in foreign language courses, and out of them, only 0.67 % (59,860 students) take Chinese, which is far from the goal set by Asia Society in 2005 that 5 % of the American high schools would take Chinese by 2015. As discussed in Section 3, Chinese language education has been promoted by new and existing efforts, involving various players. This section will look into the challenges facing the players that directly affect the Chinese language education.

4.1 National issues affecting Chinese language education in the U.S.

Despite the fact that there has been a strong social discourse of diversity and multilingualism in the U.S., few U.S. students receive long-term, articulated instruction in any foreign language (Brecht and Ingold 2002: 1). The ACTFL report (2010) shows that, in 2004–2005 and 2007–2008, more than 80 % of K-12 public school students do not study foreign languages” (p. 21). The national survey involving 5,000 U.S. schools also shows that there is a huge mismatch between what is happening in U.S. schools and what the country is demanding – an education system that prepares all children to be competent world citizens with foreign language proficiency (Pufahl and Rhodes 2011: 272). At the present time, while most of the countries around the world are moving toward foreign language instruction for all their students at a young age, the vast majority of American students are not given the opportunity to study a foreign language before middle schools and many not until they reach high school (p. 271). One example is that 59,860 students learn Chinese in the U.S., while 200 million Chinese children learn English in China (ACTFL report 2010: 21). The reason for such a mismatch is multifold. The major issues identified in the above reports are: lack of articulated sequence of instruction, shortage of qualified teachers, and insufficient funding. Pufahl and Rhodes’s survey report (2011) shows that 85 % of the 226 school respondents stated that “they had been negatively affected by the lack of qualified language teachers” (p. 269). And of the schools not planning to offer languages, 177 stated “lack of funding (e. g., “We do not have the financial resources)” (p. 262). The finding is confirmed by the report from the Committee for Economic Development that “there has been little funding directly aimed at promoting language education in America’s school” (in ACTFL report 2010: v).

On top of the issues mentioned above, there are the major adverse effects of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, Public Law 107–110, 2001), which inadvertently neglects students’ foreign language proficiency development. It has been widely agreed that, among the many U.S. ideologies, processes, or policies that are blamed for harming multilingual development, such as “de-ethnization and Americanization processes” (Fishman 1966), “the anti-bilingual education acts” (Krashen 1996), and “the one-nation one-language English-only U.S. ideology” (Hornberger 2003), NCLB is the most tangible agent that does the harm and reinforces the damage with regulations, benchmarks, and standards (Hornberger 2003; Shin 2006; Lo Bianco 2007; Wang 2007; to name just a few).

NCLB is a United States Act of Congress that is a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), signed into law in 1965 by President Lyndon Baines Johnson. In 2002, Congress reauthorized ESEA, and President George W. Bush signed the law, giving it a new name: No Child Left Behind (NCLB), which was reauthorized by the Obama Administration. Under the NCLB law, states are required to administer annual standardized tests to all students in reading and math in grades 3–8 and once in high school [23] to measure their progress with Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP). If required improvements are not made, the schools face decreased funding and other punishments, such as school closure, restructuing, hiring private company to run the school, or asking the state office of education to run the school directly. The consequence is that one-third of all public schools with foreign languages programs are negatively affected, because “funds and time have been directed to reading and math” (Pufahl and Rhodes 2011: 271). And in some cases students were pulled out of foreign language and other non-tested content courses in order to provide more extensive reading and math support (p. 271). Through her observations as a school teacher and an East-Asian heritage language researcher, Shin (2006) reports that NCLB assigns little value to the bilingual abilities of language minority students and requires schools to move these students into mainstream English-only classrooms as quickly as possible (pp. 127–128). Under such tremendous pressure, school curriculum and instruction are driven by materials that are covered by the test subjects, while those non-tested subjects such as foreign languages are neglected, especially minority languages. She witnessed a Chinese course being cancelled in a high school in her school district despite the fact that there were students who were interested in taking this course, and after the course was abandoned, any discussion of restarting the program was prevented for several years (p. 139).

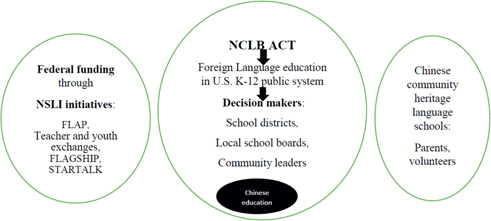

As shown in Section 3, Chinese education has been a small part of the American K-12 public school system. When a funding cut occurs, Chinese is usually the first on the chopping board despite the unprecedented opportunities brought by the NSLI initiatives, the fast-growing Chinese community heritage language schools, and China’s CI program. Out of them, the NSLI and heritage schools are “home” players in U.S. Chinese education, while the CI program is a “China-financed” partner, which has been marginalized and controversial (see more discussion in Section 4.3). The NSLI initiatives have gained enormous government funds to support some special projects involving a number of Chinese students and teachers, but they have no mechanism to, financially or administratively, defend Chinese education in the U.S. public school system.

On the other hand, Chinese community heritage schools enroll tens of thousands of Chinese students across the 50 states but cannot offer help to the public schools by enrolling their students who do not have the opportunity to take Chinese course(s). For one thing, students’ credits obtained in the heritage schools are in general not accepted by the public school system, and chances are getting slimmer in recent years. Liu (2010: 3) notes that 92 of 102 Chinese heritage language schools in southern California were eligible to apply for receipt of credit in public schools in 1996, but at the present time only 28 schools have been granted such credit transfer status. This is not that bad when compared with many other states where “credit transfer status” has not even been heard of. As shown above, these three essential “home” elements of the U.S. Chinese education are, in essence, self-contained in their own “bubbles” without much interaction or centralized/concerted efforts, as shown in Figure 3.

The “bubble effect” on the U.S. Chinese language education.

Figure 3 shows that the American public school system operates under the mandate of NCLB, which places the standardized test subjects (i. e., math and English) as the top priority, with foreign language instruction being put on the back burner. As for funding allocation and program offering in the public schools, decisions are made at the local level, with the decision makers being school districts, local school boards, and community leaders (ACTFL report, 2010). Being a small less-commonly-taught language, Chinese language courses and programs do not have much opportunity to expand but often get the chance to be terminated when there is a funding cut. Backed by the government funds, NSLI initiatives support special projects such as FLAP, Teacher and Youth Exchanges, FLAGSHIP, STARTALK, where Chinese language is a focus. However, these initiatives are on the sidelines of the U.S. school system and are in general short-term, project-based, programmatic, and piecemeal in nature. Also on the sidelines are the Chinese heritage language schools, which are outside of the mainstream system and entirely supported and operated by parents and community volunteers. (See discussion below.)

4.2 Chinese community heritage as grass-roots efforts

As evidence provided in Section 3.2, the Chinese heritage language schools in the U.S. have accommodated a large number of Chinese students, more than the American public schools and higher education combined, but they are marginalized and face many challenges. Data in the (CAL) Heritage Language Programs Database (see Section 3.2) show that the Chinese community schools are not yet full-fledged educational institutions, having difficulties in funding, teaching materials, and teacher training. They are characterized by mini-operation (one to four hours per week), makeshift classrooms and facilities, out-of-date traditional teaching practices (instructors are mostly untrained volunteers), and lack of support from the U.S. government, the mainstream school system, or their home countries. Their main financial resources are student tuitions and community donations. The majority of these schools have to rent teaching space from schools, churches, or other institutions with “unaffordable rent.” One school states,

Major challenges facing the program include locating resources and materials for curriculum design and organizing training sessions for volunteer instructors. Training student instructors to be able to effectively teach and engage language learners has been challenging, as most have no formal background in education. We would like to set up brief training seminars for interested volunteer instructors and strategies for effective curriculum design for heritage language learners. Also, the program currently does not receive funding from the Student Activities Board, and is in the process of searching for funding sources or sponsorship.

Under such circumstances, the majority of schools are looking for “funding and other support for professional training and for grant application proposal writing” to ameliorate the challenges. Moreover, unlike the formal education system, community Chinese schools have no bench marks or national/state regulations to follow/guide, nor power to track or reinforce the academic standards. One hears many compliments about their contributions as well as many complaints about their teaching quality. From her four-year-long observations, Wang (2004) reported that, in the Chinese community classrooms, students were asked to copy and memorize Hanzi over and over again, with the instruction seldom going beyond sentences. She concluded with an alarming message that “there was no sense of progress or achievement and students basically stay at the same level, unable to move forward in their heritage language proficiency or literacy” (p. 368). The observation is supported by the (CAL) Heritage Language Programs Database, which show that students often lack interest in the Chinese study provided by the heritage language schools, and many of them drop out in the middle of the program.

4.3 Confucius Institutes in controversy and debate

In the U.S., China’s CI model of spreading the Chinese language and culture through the partnership of two academic institutions, one American and one Chinese, has been conceptually attractive to American universities, public schools, and the general public. By 2011, the U.S. CIs and CCs together offered 6,217 Chinese classes with total enrollments approaching160,000 students (China News Service 2012, April 13; in Li and Tucker 2013: 34). They also organized or sponsored 2,800 cultural events with 1.47 million participants. However, as the CI program grows, concerns grow in the American discourse. Some of them have been translated into negative policies and actions.

It started with a memorandum by the U.S. Department of State dated May 17, 2012, which states that “any academics at university-based institutes who are teaching at the elementary- and secondary-school levels are violating the terms of their visas and must leave at the end of this academic year, in June” (May 21st, 2012, The Chronicle of Higher Education [24]). Moreover, after a "preliminary review," the State Department has determined that the institutes must obtain American accreditation in order to continue to accept foreign scholars and professors as teachers (Fischer 2012). The directive largely shocked and troubled Handan and its American partners. One week later, the State Department denied targeting Confucius Institutes, but the department held firm to another part of the policy guidance, by which Confucius Institutes cannot provide Chinese-language teachers to elementary and secondary schools (Fischer 2012). The consequence is that, starting in fall 2012, CI teachers are banned from teaching in American public schools even though there is a serious teacher shortage in some schools.

Following the policy of the U.S. State Department, there is a chain of actions that that are contributing to an apparent campaign to drive CIs out of American university campuses. In June 2014, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) [25] issued a statement, calling on North American universities to rethink their relationship with Confucius Institutes. “They function as an arm of the Chinese state and are allowed to ignore academic freedom. Their academic activities are under the supervision of Hanban, a Chinese state agency,” the statement expressed. In other words, China’s CIs are viewed to threaten the academic freedom of American universities (Graham, 2014). The AAUP stance immediately sparked a national conversation entitled “the Debate Over Confucius Institutes,” featuring 24 renowned academics and administrators, with a focus on the costs and benefits of having a Confucius Institute on a university campus; the economic forces at play; and the role of China in university life (ChinaFile June 23, 2014 [26] and July 1, 2014 [27]). Critics say that the CIs are funded by the Chinese government and physically located on American university campuses, which empowers them to impose external manipulation, potential threats to their hosts’ academic freedom, interference or self-censorship. By doing so, U.S. universities allow Chinese governmental intrusion and buy into China’s schemes for global dominance. Supporters of CIs say that the accusation is a “nameless fear” without hard facts, made by people who do not have personal involvement with CIs or CCs. On the contrary, through CIs, American students learn Chinese language and culture, which enables them to access more information about China and other Chinese-speaking communities. For smaller colleges or public schools that do not have the budget for teaching the critically-needed Chinese language, a CI or CC is a good source to help serve their students’ needs.

However, in September 2014, the University of Chicago announced the closing of their 5-year-old Confucius Institutes “amid growing concerns about whether universities that host them are granting undue influence to the Chinese government in matters of curriculum and staffing” (Inside Higher ED, [28] September 26, 2014). This followed a petition, signed by more than 100 faculty members, which raised concerns that in hosting the Chinese government-funded center for research and language teaching, Chicago was ceding control over faculty hiring, and course content. Within one week, Pennsylvania State University became the second American institution to confirm that it would not be continuing its agreement to host a Confucius Institute (Inside Higher ED, [29] October 1, 2014). In confirming that the university would be ending its Confucius Institute agreement at the end of the year (December 31, 2014), the dean of Penn State’s College of the Liberal Arts cited goals that were inconsistent with those of Hanban. To join in the chorus voices, the U.S. House designated a panel to investigate whether academic freedom is being threatened at universities building campuses in China and partnering with the Chinese on "Confucius institutes" in the U.S. (USA Today, [30] December 4th, 2014).

To sum up, amid CI’s fast expansion that has reached millions of American people and students, criticisms and controversies grow on its role in the context of U.S. higher education. CI supporters note that, so far, no hard facts have been found that any CI in the U.S. has interfered with the academic freedom at universities where they are located. What drives the campaign seems to be some general distrust within universities and the public at large, or a “Trojan horse” effect (Paradise 2009: 647) that, by providing money for the establishment of a Confucius Institute, Hanban will have a great deal of power in influencing teaching and other language and cultural promotion activities, either directly or indirectly (p. 662).

5 Discussion and recommendations

This study gathered evidence to furnish a better understanding of Chinese education in the U.S., with implications for policy making and recommendations for future development. It looked into the Chinese immigration history in the U.S., the current opportunities and developments of the U.S. Chinese education, the players involved and challenges they are facing. Results show Chinese education has been rapidly expanding in the past decade, a time when foreign language proficiency is beginning to be appreciated in the U.S., and Chinese is recognized as a language critically-needed by the U.S. for national security and international competition. It also happens at a time when China has fully built its economic power and amid calls for the need to develop a soft power with global promotion of the Chinese language and culture. For the common cause, the U.S. and Chinese governments joined forces that resulted in two new players in the U.S. Chinese education: the NSLI initiatives and China’s CI projects. Both have exerted great efforts and made significant contributions, and both take a mainstream approach by pursuing the public school system and higher education without reaching out to the Chinese community heritage schools.

Further analysis shows that there is no coherent language policy in the U.S. education system or meaningful collaboration between the relevant players, which exerts a “bubble effect” on U.S. Chinese education. On the one hand, the American public school system operates under the mandate of NCLB, which places standardized test subjects (i. e., math and English) as the top priority, with foreign language instruction being inadvertently neglected. Being a small less-commonly-taught language, Chinese language courses and programs do not have much opportunity to expand, but often get terminated when there is a funding cut in the system. On the other, backed by the government funds, NSLI initiatives support special projects where Chinese language is a focus, but these initiatives are short-term project-based and are on the sidelines of the American education system without the mechanism to defend Chinese education within the public school system. Also on the sidelines are the Chinese heritage language schools, which are entirely grass-roots efforts, suffering from poor funding and resources.

Likewise, China’s CI program has been playing a marginal role, and worse, with its mission being questioned and debated. Although the CCs and CIs have reached millions of American people and students, the practice of physically locating on the American university campuses with heavy investments seems to have gone beyond the comfort zone of the traditional academia. This has thus trigged the alarm of “external manipulation, academic interference or threats” in the American discourse. The fear has resulted in CI closure in two large universities and an all-around restriction on CI teachers in the U.S. public schools.

Recommendations

1. Include foreign language education in U.S. K-12 core curriculum

To meet the country’s needs, foreign language education should be included in the U.S. K-12 core curriculum as one of the budget line items, such as English, math, and science. Instead of creating programmatic piecemeal initiatives, the U.S. government should take a coherent, holistic, and long-term approach by giving all American children the opportunity to learn foreign languages, with early start and articulated sequencing.

2. China’s CI program should reach out and support grass-roots efforts

China’s soft power campaign means to win hearts and minds, and to gain global engagement and internationalization. As the major force of this campaign, CIs should reach out to the Chinese community heritage schools with support in funding, resources, and teachers. The Chinese heritage schools are the center-piece of Chinese-speaking community. Every Chinese speaker in the U.S. has some connection with the heritage schools; they either have a child, a relative or friend’s child enrolling in these schools, or hold a teaching job or volunteer assignment in these schools. Given the total of 3,794,673 Chinese speakers in this country, winning the hearts and minds of these people means winning 1.23 % of the American population.

3. Improve data collection and data quality

To maintain accountability and success, there needs quality data collection and data analysis systems. So far, neither of the two leading heritage language organizations, Associations of Chinese Language Schools 全美中文學校聯合總會 and the Chinese School Association in the United States 全美中文学校协会, has any database. Nor do their member schools participate in the (CAL) Heritage Language Programs Database. In addition, neither of the two association websites give any information about their member schools, actual enrollments, curriculum, teaching staff or materials. The same is true of the CI program. Given the hundreds of CIs and CCs expanding in 126 countries/regions, an open database with outcome measures is crucial for the CI HQ to understand participant needs and evaluate the institutes’ performance. The database can also serve as a platform for members and partners to exchange information and for local and academic communities to understand the institutes and their host country.

About the authors

Yun Xiao is Professor of Chinese language and linguistics at Bryant University, Rhode Island, U.S.A. She has a Ph.D. degree in Linguistics. Her research interests are in Chinese syntax and discourse. Her publications include around 30 journal articles and book chapters, three co-edited/co-authored research monographs and a four-volume Chinese Literature Reading Series.

萧云是美国罗得岛布莱恩特大学中国语言和语言学教授。学历为语言学博士。她的研究兴趣为汉语句法和话语。她的著作包括期刊论文与研究专著章节近 30 篇,参与编辑和撰写的学术专著 3 本,及 4 卷中国文学阅读系列。

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL). 2010. Foreign language enrollments in K-12 public schools: Are students prepared to a global society? Alexandria, VA: American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.Search in Google Scholar

Brecht, Richard D. & Catherine W. Ingold. 2002. Tapping a national resource: Heritage languages in the United States. EDO-FL-02-02. ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics. WWW.CAL.ORG/ERICCLL.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, Wellington K.K. 2002.Chinese American business networks and trans-Pacific economic relations since the 1970s. In Peter. H. Koehn & Xiao H. Yin (eds.), The expanding roles of Chinese Americans in U.S.-China relations: Transnational networks and trans-pacific interactions, 145–161. Armonk, NY: An East Gate Book.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Irene. 2003. The Chinese in America: A narrative history. New York: Penguin.Search in Google Scholar

Chao, Teresa H. 1997. Chinese heritage community language schools in the United States. ERIC Digest, ED409744, 1–7.Search in Google Scholar

Fischer, Karin. 2012. State Department denies targeting Confucius Institutes but holds to decision on visas. The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/State-Department-Denies/131955/ (accessed August 2015).Search in Google Scholar

Fishman, Joshua A. 1966. Preface. In Joshua A. Fishman, Vladimir C. Nahirny, John E. Hofman, & Robert G. Hayden (eds.), Language loyalty in the United States: The maintenance and perpetuation of non-English mother tongues by American ethnic and religious groups, 15–20. London: Mouton & Co.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, David, Dennis Looney & Lusin Natalia. 2015. Enrollments in languages other than English in United States institutions of higher education, fall 2013. Web publication, February 2015, http://www.mla.org/pdf/2013_enrollment_survey.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Graham, Edward. 2014. Confucius Institutes Threaten Academic Freedom. American Association of University Professors (AAUP) September–October 2014. http://www.aaup.org/article/confucius-institutes-threaten-academic-freedom#.VcEBCE1RHX5Search in Google Scholar

Hornberger, Nancy. 2003. Multilingual language policies and the continua of bi-literacy: An ecological approach. In Nancy. H. Hornberger (ed.), Continua of bi-literacy: An ecological framework for educational policy, research, and practice in multilingual settings, 315–339. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters LTD.10.21832/9781853596568-018Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, Scott & He Fan. 2013. The United States, China, and global governance: A new agenda for a new era. Beijing, China: Rongda Quick Print. Distributed by the Research Center for Chinese Politics & Business, Indiana University and the Institute for World Economics & Politics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.Search in Google Scholar

Koehn, Peter. H & Xiao H. Yin. 2002. Chinese American transnationalism and U.S.-China relations: Presence and promise for the trans-pacific century. In Peter H. Koehn & Xiao H. Yin (eds.), The expanding roles of Chinese Americans in U.S.-China Relations: Transnational networks and trans-pacific interactions, xi–xxxx. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen D. 1996. Under Attack: The case against bilingual education. Culver City, CA: Language Education Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Shuai & G. Richard Tucker. 2013. A survey of the U.S. Confucius Institutes: Opportunities and challenges in promoting Chinese language and culture education. Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers Association 48(1). 29–53.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Sufei. 2002. Navigating U.S.-China waters: The experience of Chinese students and professionals in science, technology, and business. In Peter. H. Koehn & Xiao H. Yin (eds.), The expanding roles of Chinese Americans in U.S.-China relations: Transnational networks and trans-Pacific interactions, 20–35. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Na. 2010. Chinese heritage language schools in the United States. Heritage Briefs. Center for Applied Linguistics. www.cal.org/heritageSearch in Google Scholar

Liu, Na. 2013. The linguistic vitality of Chinese in the United States. Heritage Language Journal 10(3). 294–304.10.46538/hlj.10.3.2Search in Google Scholar

Lo Bianco, Joseph. 2007. Emergent China and Chinese: Language planning categories. Language Policy 6(1). 3–26.10.1007/s10993-006-9042-3Search in Google Scholar

McCabe, Kristen. 2012. Chinese immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/chinese-immigrants-united-states-1Search in Google Scholar

Nye, Joseph S. 2011. The future of power. New York: PublicAffairs.Search in Google Scholar

Paradise, F. James. 2009. China and international harmony: The role of Confucius Institutes in bolstering Beijing soft power. Asian Survey XLIX(4). 647–665.10.1525/as.2009.49.4.647Search in Google Scholar

Pufahl, Ingrid & Nancy Rhodes. 2011. Foreign language instruction in U.S. schools: Results of a national survey of elementary and secondary schools. Foreign Language Annals 44(2). 258–288.10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01130.xSearch in Google Scholar

Shin, Sarah J. 2006. High-stakes testing and heritage language maintenance. In Kimi Kondo-Brown (ed.), Heritage language development: Focus on east Asian immigrants, 127–144. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/sibil.32.10shiSearch in Google Scholar

Stewart, Vivien & Shuhan Wang. 2005. Expanding Chinese language capacity in the United States. Asia Society report.Search in Google Scholar

Sung, Betty Lee. 1967. Mountain of gold: The story of the Chinese in America. New York: The Macmillan Company.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Shuhan C. 2004. Biliteracy resource eco-system of intergenerational language and culture transmission: An ethnographic study of a Chinese-American community. University of Pennsylvania unpublished dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Shuhan C. 2007. Building societal capital: Chinese in the U.S. Language Policy 6(1). 27–52.10.1007/s10993-006-9043-2Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Shuhan C. 2010. Chinese language education in the United States: A historical overview and future directions. In Jianguo Chen, Chuang Wang & Jinfa Cai (eds.), Teaching and learning Chinese: Issues and perspectives, 3–32. Castleton, VT: Information Age Publishing, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Willett, Megan. 2015. Chinese tourists are flooding into the US thanks to a new visa rule. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/chinese-tourists-to-us-on-the-rise-2015-1.Search in Google Scholar

Xiao, Yun. 2008. Home literacy environment in Chinese as a heritage language. In Agnes W. He & Yun Xiao (eds.), Fostering rooted world citizenry: Studies in Chinese as a heritage language, 151–166. Hawaii: NFLRC, University of Hawaii Press.Search in Google Scholar

Xiao, Yun. 2010. Chinese in the United States. In K. Potowski (ed.), Language diversity in the USA, 81–95. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511779855.006Search in Google Scholar

Xiao, Yun. 2011. Chinese language in the United States: An ethnolinguistic perspective. In Linda Tsung & ken Cruickshank (eds.), Teaching and learning Chinese in global contexts, 81–95. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. 181–196.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Hongqin & Jianbin Huang. 2010. China’s policy of Chinese as a foreign language and the use of overseas Confucius Institutes. Educational Research for Policy and Practice 9. 127–142.10.1007/s10671-009-9078-1Search in Google Scholar

©2016 by De Gruyter Mouton