Abstract

Reformers have offered many proposals for changing the Senate filibuster, ranging from modest adjustments to outright abolition. I draw on formal models of obstruction in legislatures to analyze the consequences of three such proposals: creating an opportunity to close debate with a simple majority vote after a sufficiently long floor debate, making it more onerous for the minority to sustain filibusters, and outright abolishing the filibuster. In each of these cases, the models offer a more complete understanding of the effects of these proposals.

1 Introduction

The filibuster ensures that every senator has the opportunity to speak on controversial measures, but it also prevents the Senate from passing most kinds of legislation unless it can muster a sixty-vote supermajority. This de facto supermajority requirement is controversial. Defenders argue that it protects the country from ill-considered legislation and encourages bipartisan lawmaking, while critics say it undermines the will of the voters and precludes meaningful action on pressing policy problems (Jentleson 2021). These critics offer many proposals for reforming the filibuster, ranging from totally eliminating it in favor of simple majority rule to smaller adjustments that would help supermajorities pass legislation more quickly.

This debate over the filibuster is ultimately a normative debate about what ought to be done, but, as in many normative debates, both sides rely on falsifiable claims about how the world works. Political scientists have made tremendous contributions to these positive aspects of the debate. For example, Binder and Smith (1997) debunk important pieces of conventional wisdom espoused by both sides. Contrary to the claims of the filibuster’s defenders, the filibuster was not a part of the Senate’s original design. In fact, it was contentious even in the 19th century. Contrary to the claims of its critics, it was not historically reserved for issues of great national importance; it has long been used for parochial issues. Curry and Lee (2021) show that the role the filibuster plays in producing gridlock may be overstated. Bicameralism, separation of powers, and divisions within the majority party would doom many bills even if the Senate abolished the filibuster. Political scientists also find the filibuster has become more potent as the Senate has become busier (Binder, Lawrence, and Smith 2002; Koger 2010; Sinclair 2013; Wawro and Schickler 2004). They illuminate the role of many factors in securing the filibuster against depredations by the majority (Binder 2022; Dion 1997; Schickler and Wawro 2011; Smith and Park 2013) and they have sustained a robust debate about the role minority restraint has played in the filibuster’s survival (Binder, Madonna, and Smith 2007; Overby and Bell 2004; Smith 2022; Wawro and Schickler 2006).

Many of the leaders of this literature have played an active role in the public debate, some as advocates of particular positions and some as impartial conveyors of what political scientists know about the filibuster. Others have even proposed their own reforms (Gould, Shepsle, and Stephenson 2021; Ornstein 2020).

One perspective has been notably absent from this public debate: formal theory. Political scientists have made extensive use of game theory to analyze obstruction and the filibuster (Bawn and Koger 2008; Dion et al. 2016; Fong 2022; Fong and Krehbiel 2018; Gibbs 2022; Judd and Rothenberg 2021; Krehbiel and Krehbiel 2022; Patty 2016), but most of this work does not explicitly analyze the changes to the filibuster that reformers have proposed. The exception, Dion et al. (2016), does so only briefly.

This absence is unfortunate, because formal models can answer one of the basic questions underlying any reform debate: “If we implemented this reform, what would happen?” In general, there are two ways to predict the consequences of a reform. The first is to look to experience – to examine instances in which similar reforms were adopted in similar institutions. The second is to use logic – to derive from first principles how the reform would influence behavior. Statistical tests are a rigorous form of the experience-based approach, and formal theory is a rigorous form of the logic-based approach. Typically, it is best to use both together, but formal theory is indispensable when there is little relevant experience to draw on, as is the case for new, creative reforms to the Senate filibuster.

Of course, predictions based on formal theory might be wrong. My goal is not to establish that the models correctly predict what would happen under various reforms. Rather, my goal is to present the logic behind these models in a way that is accessible to readers who have not had extensive training in game theory, apply the logic to major reform proposals, and then leave it to readers to decide whether the arguments are compelling. In short, I use the formal models to present possibilities that the debate surrounding reform ought to at least entertain.

To that end, I analyze three major proposals to reform the filibuster: creating an opportunity to close debate with a simple majority vote after a sufficiently long floor debate, making it more onerous for the minority to sustain filibusters, and outright abolishing the filibuster in favor of simple majority rule. In each case, I describe the proposal, match it to a relevant formal model, explain the intuition behind the model, and then use the model to predict how senators would behave under the reform. Many of the models’ predictions are intuitive and conform to the predictions of experts on the legislative process. Yet, in each case, the model also adds something that would be difficult to discern without its assistance. In some cases, these added insights more precisely illustrate just what kind of balance between minority rights and majority rule the reform would strike, but in others, they show that the reform could backfire on members of the majority or on the reformers who want the Senate to spend less time wrangling with obstruction.

2 Ratcheting Cloture

In 1995, Senators Tom Harkin (D-IA) and Joe Lieberman (D-CT) introduced a proposal to gradually decrease the cloture threshold over the course of a debate.[1] Invoking cloture (ending debate) on the first vote would require sixty votes. If the motion to invoke cloture failed, the Senate would have to debate for a while longer before anyone could make another motion to invoke cloture. However, the second cloture vote would require fewer votes to pass. If it, too, failed, the Senate would continue debate for still longer before anyone could try again, and that next cloture vote would have an even lower threshold. The cycle would repeat until the threshold for invoking cloture fell to a simple majority of fifty-one votes (Table 1). In short, once the Senate had debated a motion for long enough, it could invoke cloture by a simple majority.

Harkin filibuster reform proposal.

| Cloture vote | Threshold | Days to next cloture vote |

|---|---|---|

| First | 60 | 2 |

| Second | 57 | 2 |

| Third | 54 | 2 |

| Fourth | 51 | 2 |

-

Note: Under Senator Harkin’s proposal, the cloture threshold would gradually decline over the course of a debate. After the third cloture vote on a motion or measure, all subsequent cloture votes would require only a simple majority.

Senator Harkin has repeatedly reintroduced this proposal, and even today, over 25 years after its first introduction, it is still an important proposal in the debate surrounding filibuster reform. Part of the enduring appeal of this reform is that it pays homage to the principle of deliberation. Defenders of the filibuster often point to the value of extended debate, and this proposal would ensure that opponents of a measure would have an opportunity to voice their concerns on the Senate floor. In defense of his proposal, Harkin (2011) argues, “Senators would have ample time to make their arguments and attempt to persuade the public and a majority of their colleagues. This protects the rights of the minority to full and vigorous debate and deliberation, maintaining the very best features of the United States Senate”.

However, Senators can already criticize pending legislation in floor speeches, on social media, and in press releases. The real value of the filibuster, from the perspective of the floor minority, is that the majority must address their concerns to pass the bill. Under this ratcheting cloture threshold, the majority could simply ignore the minority and invoke cloture once enough time had elapsed.

Perhaps the majority would simply steamroll the minority, but it is important to account for a crucial fact of contemporary legislative politics: time is scarce in the Senate. The majority rarely has time to pass all of the legislation it would like to, so giving floor time to one bill entails withholding it from some other bill. If the majority can expedite the passage of legislation by compromising with the minority, it might do so that it can pass more bills. Harkin (2011) makes exactly this point: “Right now, there is no incentive for the minority to compromise; they know that they have the power to block legislation. But, if they know that at the end of the day a bill is subject to majority vote, they will be more willing to come to the table and negotiate seriously. Likewise, the majority will have an incentive to compromise because they will want to save time, not have to go through numerous cloture votes and thirty hours of debate post-cloture.”

Professor Sarah Binder offers a more pessimistic assessment. She concurs that this reform would leave the minority with real leverage, but contends that rather than compromise, the majority might simply capitulate. She writes, “Senate majorities would run the risk of consuming valuable floor time that could otherwise be spent advancing other priorities. Majorities would likely face pressure from constituencies outside the Senate to put aside filibustered measures and move on to priorities that might command stronger support.”[2]

All three of these outcomes – the majority steamrolling the minority by allowing debate to continue until it could pass the bill by a simple majority, the majority compromising with the minority to expedite the passage of legislation, and the majority capitulating to the minority to allocate floor time to bills that could pass more quickly – seem plausible. So, under what conditions would the majority steamroll, compromise, or capitulate?

Fong and Krehbiel (2018)’s model of limited obstruction offers an answer. Limited obstruction is the ability to delay but not outright block legislation.[3] Under the Senate’s current rules, even a single senator can engage in limited obstruction, because invoking cloture takes a great deal of floor time even if the majority coalition has the necessary sixty votes. To invoke cloture, a senator must first gather signatures for a cloture petition and submit the petition to the clerk. Then, the Senate must wait a while before it can vote on the cloture petition (a process known as waiting for the cloture petition to ripen). Once the petition is ripe, the Senate must conduct a quorum call, and after the quorum call, the senators can finally vote on cloture.[4] If the motion to invoke cloture gets enough votes, the Senate then has a period of post-cloture consideration, which, under current rules, can last up to thirty hours. The Senate must complete this entire process at least twice: once on the motion to proceed and once on the motion to bring debate to a close.[5]

Harkin’s ratcheting cloture proposal would eliminate the filibuster, which would leave the minority in a weaker position than they are under current rules, but it would compensate the minority by giving it additional opportunities for limited obstruction. Table 2 illustrates how by considering how many days it would take the majority to pass legislation under three different sets of rules. Under current rules, a minority coalition of at least forty-one senators can outright block legislation, but smaller minorities have to make do with limited obstruction. If they exploit all of their procedural prerogatives, they can make passing one bill consume 11 days of session. If the Senate outright abolished the filibuster by moving to simple majority cloture but did not change the other rules surrounding cloture, then no matter how large the minority was, it would only be able to delay the passage of a bill for 11 days.

Days of session required to pass legislation by size of minority coalition.

| ≤ 40 | 41–43 | 44–46 | 47–50 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current rules | 11 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ |

| Simple majority cloture | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Ratcheting cloture | 11 | 15 | 19 | 23 |

-

Note: These calculations assume the Senate is in session for 8 hours per day and that the Senate consumes the entire 30 hours of post-cloture consideration, just as in the analysis from Table 1 of the Congressional Research Service’s report ROL30360. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=RL30360.

Not so under Senator Harkin’s ratcheting cloture proposal, which would give larger minorities more leverage. A minority of forty senators could force only two cloture votes: one on the motion to proceed and another on the motion to move to a final vote. However, a minority of forty-one senators could force four cloture votes: on the motion to proceed, they could block the first motion to invoke cloture, but they would lose on the second one. Then, they could do it all over again on the motion to proceed to a final vote. A minority of forty-four senators could force six cloture votes, and a minority of forty-seven could force eight cloture votes. As Table 2 shows, all of these cloture votes add up to a considerable expenditure of time. Eight cloture votes would consume 23 days of session.

These are upper bounds of how much a unified minority coalition could delay the passage of legislation.[6] The minority could decline to use all of its procedural prerogatives or enter into a unanimous consent agreement with the majority to allow the bill to pass more quickly.[7] Therefore, passing a bill with forty-nine senators opposed would not necessarily take 23 days. The minority could impose any amount of delay its members agree to, as long as it is no more than 23 days.

The pro-filibuster critics of the Harkin proposal focus on how 23 days of delay is far less than the indefinite delay that is permitted under current rules. Harkin focuses on how the minority’s ability to choose between zero and 23 days of delay gives the majority a strong incentive to bargain with it so that it will choose something closer to zero. Binder focuses on how a large minority’s ability to impose 23 days of delay deters the majority from even trying to bring a bill to the floor if it knows that the bill will be opposed by a large minority. All three are correct, but Fong and Krehbiel’s model of limited obstruction allows us to see how these three countervailing forces interact to shape the Senate’s agenda.

To illustrate the logic of their model, consider a numerical example. Suppose that the legislature can be neatly divided into two factions: a majority of fifty-one and a minority of forty-nine.[8] There are four bills that the majority wants to pass: A, B, C, and D. Each bill, if passed, would help the majority and hurt the minority. Table 3 illustrates the payoff passing each of the four bills would give to the majority and the minority.

Example for Fong and Krehbiel’s model of limited obstruction.

| Bill | Majority’s payoff | Minority’s payoff |

|---|---|---|

| A | 10 | −13 |

| B | 7 | −9 |

| C | 4 | −3 |

| D | 4 | −4 |

-

Note: The majority has the ability to pass any of these four bills, but depending on how much delay the minority imposes, it may not have enough time to pass all of them.

The majority would like to pass all four bills, but unfortunately it might not have time. If so, it must decide which of these bills it will pass given the limited floor time it has available. For this example, suppose the majority has 46 days of session to pass bills. Under ratcheting cloture, the minority’s procedural prerogatives would give it the right to impose up to 23 days’ worth of delay on each bill the majority brings to the floor. In the Fong and Krehbiel model, the minority first tells the majority how much delay it plans to impose on each bill if the majority brings it to the floor.[9] The majority then decides which bills it wants to bring to the floor and pass.

The minority could threaten all-out resistance by telling the majority, “No matter which bill you bring to the floor, we’ll fight you every step of the way and it’ll take 23 days.” What would the majority do in this scenario? Since it only has 46 days to pass bills and passing each bill takes 23 days, it would have time to pass just two bills. It might as well pass the two bills that give it the highest payoff, A and B. Passing these two bills gives the majority a payoff of 17 and the minority a payoff of −22. Table 4 summarizes this argument.

What if the minority engages in all-out delay?

| Bill | Majority’s payoff | Minority’s payoff | Days to pass |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 10 | −13 | 23 |

| B | 7 | −9 | 23 |

| C | 4 | −3 | 23 |

| D | 4 | −4 | 23 |

| Feasible agenda | Majority’s payoff | Minority’s payoff |

|---|---|---|

| A, B | 17 | −22 |

| A, C | 14 | −16 |

| A, D | 14 | −17 |

| B, C | 11 | −12 |

| B, D | 11 | −13 |

| C, D | 8 | −7 |

-

Note: The top table shows the possible bills that the majority could put onto the agenda, and the bottom table shows the possible agendas the majority could enact, given its time constraints. If the minority threatens to impose the maximum delay no matter which bill the majority brings to the floor, the majority has only enough time to pass a pair of bills. Since it can pass any pair of bills, it would pass the pair that gives it the highest payoff: A and B.

Compared to the current rules, ratcheting cloture would help the majority and hurt the minority. In this example, none of the bills would have passed under the current rules, because each commands only fifty-one votes. Compared to totally eliminating the filibuster, the Harkin proposal would help the minority and hurt the majority by creating additional opportunities for limited obstruction. If the filibuster were totally eliminated, all four bills would have passed, because each would’ve taken only 11 days and the minority has 46 days to work with.

However, the minority can do even better if it adopted a more sophisticated strategy than all-out resistance. What if the minority allowed some bills to pass relatively quickly? Since the majority is pressed for time, it might be tempted to go for the bills it could pass quickly, even if this meant it would not have time to pass some of the other bills it wanted. That is, the majority might take quantity over quality.

The minority could tell the majority, “We hate A and B. If you try to pass either of them, you’re looking at the full 23 days. We don’t like C or D either, but they’re not so bad compared to A and B. If you bring C or D to the floor, we’ll let them pass in 11 days each.” The majority would respond by passing A, C, and D, which would together consume 45 days of floor time and leave it without enough time to pass B. This would give the majority a payoff of 18, better than the 17 it would’ve gotten if it had passed A and B over the vociferous obstruction of the minority. The deal makes the minority better off too. They get a payoff of −20, better than the −22 they would’ve gotten if they had tried to obstruct every bill the majority brought to the floor. Table 5 illustrates this argument.

What if the minority engages in sophisticated Delay?

| Bill | Majority’s payoff | Minority’s payoff | Days to pass |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 10 | −13 | 23 |

| B | 7 | −9 | 23 |

| C | 4 | −3 | 11 |

| D | 4 | −4 | 11 |

| Feasible agenda | Majority’s payoff | Minority’s payoff |

|---|---|---|

| A, B | 17 | −22 |

| A, C, D | 18 | −21 |

| B, C, D | 15 | −16 |

-

Note: The top table shows the possible bills that the majority could put onto the agenda, and the bottom table shows the possible agendas the majority could enact, given its time constraints. The minority can do better if it does not engage in all-out delay. If it threatens to delay A and B but promises to allow C and D to pass relatively quickly, the majority would still pass A, but instead of passing B, it would pass C and D. This makes both the majority and the minority better off compared to the strategy of all-out delay illustrated in Table 4.

In fact, this is the best the minority can do if the majority responds optimally to their obstruction – the equilibrium outcome of the game. Fong and Krehbiel show that this pattern holds for any configuration of bills and any amount of time left in the session. The minority first envisions what would happen if it obstructed everything. Then, it tries to find deals that make both it and the majority of the better off. These deals always take the form of the minority telling the majority, “I’ll let you pass this bundle of bills quickly, but that means you will not have time to pass some other bill that I detest,” and the majority responding, “That sounds good to me. I like that bundle of bills better than the bill I’m giving up anyway.”

This simple example exhibits all three of the consequences that others have predicted. The minority must offer some kind of compromise agenda that the majority prefers to A and B, because the majority always has the option to pass A and B no matter what the minority does. This means there is nothing the minority can do to block A. Even if it promised to let B, C, and D pass quickly if the majority forgoes A, the majority would just pass A and B over the minority’s objections, because it has the 46 days it needs to pass two bills over maximal obstruction. In short, the majority steamrolls the minority on A-just as those who emphasize minority rights predict. However, the majority and minority compromise on C and D. The minority doesn’t like them, and the majority doesn’t like either as much as it likes B, but the two bills pass anyways because both sides prefer the two of them to bill B alone. The reform fosters compromise, just as Harkin predicts. But as a result of the compromise, the majority doesn’t have enough time to pass B, so it capitulates on that bill, consistent with Binder’s prediction.

The Fong and Krehbiel model does not just bring all three predictions together in a single model. It also predicts what kinds of bills lead to steamrolling, compromising, and capitulating. In general, limited obstruction forces the majority to take the minority’s preferences into account when it sets the agenda, but the threat of delay can only accomplish so much. If a bill is sufficiently important to the majority relative to the other bills it could pass, like A is in the example, then the majority will steamroll the minority. No matter how much delay the minority threatens on such a bill and no matter how much cooperation it pledges on others, there is nothing the minority can do to prevent the majority from passing it.

Rather, limited obstruction allows the minority to prevent the passage of bills the majority likes but that it absolutely detests, such as B. It achieves this by compromise – by allowing the majority to quickly pass bills like C and D that are middling priorities for the majority in exchange for the majority’s capitulation on B. To be clear, the bills that get passed through this compromise are not necessarily bipartisan bills. Rather, they are bills the majority and minority both like relative to the legislation the majority would otherwise pass.

Since the Harkin proposal eliminates the filibuster but leaves the minority with additional opportunities for legislative obstruction, the majority would still be able to pass its top priorities over potentially strenuous obstruction from the minority, just like it could if the filibuster were outright abolished. However, bills that the minority hates would be less likely to get onto the agenda than they would be under simple-majority cloture, because they would take so long to pass. Bills that do not stir such strong feelings in the minority would be more likely to get onto the agenda, because the minority might offer to allow them to pass quickly so that there would not be enough time for the majority to pass more damaging legislation.

3 Making Filibusters Costlier to the Minority

In a filibuster, opponents of the bill take to the floor and stage a never-ending debate on the bill. If they carry on for long enough, one of two things can happen. One possible outcome is that they drag the debate out until the end of the congress, in which case the bill fails because the Senate runs out of time. The other is that the majority gives up. As long as the opponents of the bill hold the floor, the Senate cannot move on to other business without the minority’s consent. If there are other bills the majority can pass, the opportunity cost of leaving the filibustered bill on the floor may eventually become unacceptably high, in which case the majority would pull the bill from the floor.

Since the majority would typically rather use scarce floor time to take up bills it can actually pass, it usually does not even bring a bill to the floor unless it has the votes necessary to overcome a filibuster. Indeed, when commentators say that a filibuster killed a bill, they often mean that a credible threat of a filibuster dissuaded the majority from trying to pass it in the first place. Those that do distinguish between the two call these threats silent filibusters, and they call actually taking to the floor to keep debate open a talking filibuster.

The ubiquity of silent filibusters does not sit well with some, such as Senators Jeff Merkley (D-OR), Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and Tom Udall (D-NM) (Barnes et al. 2021). They believe there would be fewer filibusters if opponents of a bill had put time and energy into obstruction, so they advocate reforms to make filibustering costlier to the minority.

For example, Merkley proposes to change the quorum requirement during filibusters. The majority’s goal in a talking filibuster is to exhaust the obstructionists, but Merkley points out that current rules make it very difficult to actually force them to hold the floor and speak. If there are not at least fifty-one senators on the floor, the obstructionist can note the absence of a quorum. The absence of a quorum suspends Senate business until a quorum can be mustered, which allows the obstructionists to rest. If the majority wants to wear out the minority, it must leave at least fifty senators near the floor at all times to respond to quorum calls. To strengthen the majority’s position, Merkley proposes to change the rules so that the obstructionists would need to keep talking even in the absence of a quorum.

In a dear colleague letter advocating for his proposal, Merkley wrote, “By requiring time and energy to filibuster, the talking filibuster could strip away frivolous filibusters.”[10] By this, he means the minority would be less likely to filibuster in the first place if it anticipated it might actually have to sustain a talking filibuster.

Political scientist Norman Ornstein offers an alternative way to shift the burden to the minority (Ornstein 2020), which was subsequently endorsed by former-Senator Al Franken (D-MN) (Franken and Ornstein 2021). Under current rules, the majority must assemble a coalition of at least sixty senators to invoke cloture. Even if fifty-nine senators vote for cloture and only one votes no, debate continues. This allows the minority a great degree of flexibility. As long as they leave at least one of their senators on the floor and prevent the majority from assembling a sixty-vote coalition, the rest can go about their business as they please, even flying home to their states if they want to.

Ornstein’s proposal would flip the burden of cloture, and it would turn even silent filibusters into wars of attrition. Instead of needing sixty votes to invoke cloture end debate, the minority would need to produce at least forty-one votes to block cloture. That way, for as long as the filibuster continued, the minority would have to keep at least forty-one senators close to the Capitol to vote down attempts to invoke cloture. According to Ornstein, “By making [filibustering] harder, this reform would reduce the number of filibuster attempts, while preserving the minority’s ability to stall Senate action on high-profile legislation.”[11]

Talking filibusters – those in which the majority tries to exhaust the minority – can be modeled as wars of attrition, as in Dion et al. (2016).[12] The longer the filibuster drags on, the more bills the majority foregoes, but the more taxing holding the floor is for the minority. The war of attrition model in Dion et al. (2016) incorporates a key aspect of talking filibusters: each side does not know for sure how much pain the other side can endure. If the majority were certain that the minority could hold out for an unacceptably long time, it would not bother to bring the bill to the floor in the first place (in other words, there would be a silent filibuster). If the minority were certain that the majority would keep the bill on the floor until the minority was exhausted, it would not bother to try to filibuster (unless there were overriding considerations about position-taking or limited obstruction).

According to Dion et al. (2016), the probability of a talking filibuster depends on how costly it is for each side to stay in the fight. If the majority actively benefits from the filibuster fight, as it would if its constituents felt strongly about the bill and rewarded spending floor time on it more than they would reward any other alternative (Patty 2016), then it will bring the bill to the floor and leave it there until it passed or the session ended.[13] Likewise, if the minority actively benefits from the filibuster fight because it allows it to take positions that are popular or to show their constituents that it is not afraid to fight (Patty 2016), it will sustain the filibuster until the majority gives up or the session ends. Call these strong majorities and minorities, respectively.

The situation is more interesting if at least one side incurs a cost for staying in the filibuster fight. Perhaps the opportunity cost of not passing other bills outweighs the political benefit the majority gets from fighting for the bill, or perhaps the position-taking benefits the minority gets from opposing the bill are small compared to the costs of staying in Washington, day after day, to carry on the debate. Call these weak majorities and minorities, respectively.

To provide a visual metaphor, suppose that the Senate decides which bills pass with a very cold pool. Each side is represented by a swimmer wearing a wetsuit, which might be a high-quality insulated wetsuit or a cheap knockoff that provides little protection against the cold. Each swimmer knows the quality of his own wetsuit but doesn’t know what kind of wetsuit the other is wearing. The majority’s swimmer first decides whether it wants to jump in the pool. If he doesn’t jump in, the bill fails. If he does, the minority’s swimmer decides whether to jump in after him. If she doesn’t follow him, the bill passes. If she does, whoever stays in the longest wins.

Should you jump in, and, if so, how long should you stay? If you’re wearing a good wetsuit, you might as well jump in and have a nice swim. If both swimmers are wearing good wetsuits, they’ll both stay in the pool until the lifeguard pulls them both out. You face a more difficult choice if you’re wearing a cheap wetsuit. You would not want to jump in if you knew for sure the other swimmer had a good wetsuit. They’d surely outlast you, and you’ll have spent a long time freezing in the pool with nothing to show for it.

But maybe your opponent has a bad wetsuit too. If you’re the majority, and you jump in, maybe the minority will incorrectly conclude that you must have a good wetsuit and stay out of the pool. If you’re the minority and you see the majority jump in, maybe they were bluffing, and if you jump in after them, you might trick them into thinking you’re wearing a good wetsuit.

This bluffing and counterbluffing gives rise to the most interesting possibility in the war of attrition: the possibility of two swimmers, both in bad wetsuits, freezing together in the pool. Each swimmer hopes that if they stay in a little longer, the other will conclude that they must have a good wetsuit and get out of the pool. They might both stay in for quite a while before one finally says, “This is crazy. Since you’ve been able to stay in the pool for this long, you must have a good wetsuit. I’m out.”

So, how likely are the two swimmers to both jump into the pool? If they both jump, how long will they stay there? This is equivalent to asking how likely talking filibusters are to occur and how long they last when they do. In the visual metaphor, the relevant considerations are obvious. How badly does each side want to win and how likely is it that each side is wearing a good wetsuit? In the terms of the Senate, how important is the bill to each side and what is the probability each side is strong?

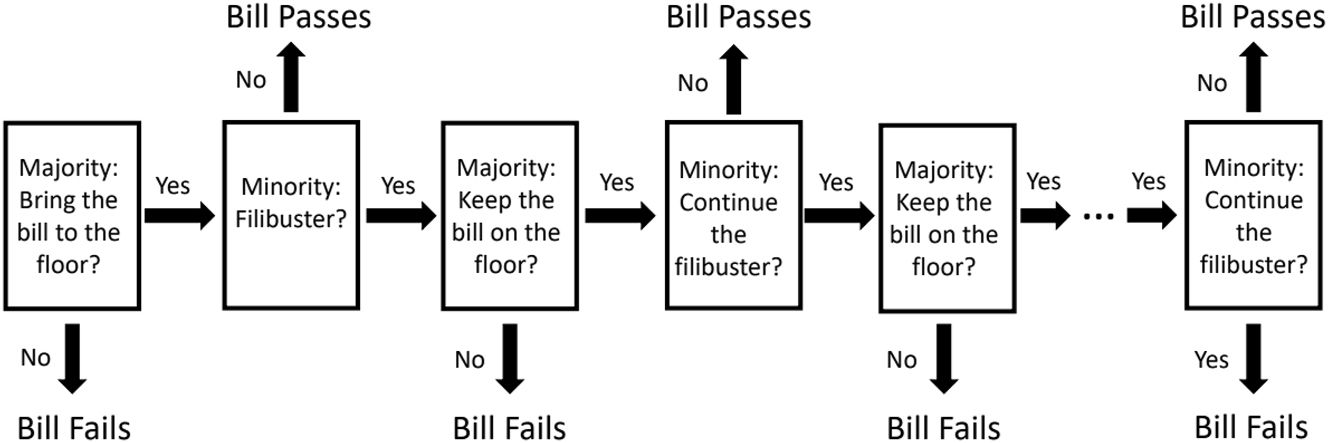

Figure 1 summarizes the model. According to the model, talking filibusters can arise for one of two reasons. First, both sides might be strong and get political payoffs from engaging in the filibuster fight. Second, at least one side (and possibly both) might be a weak party that is attempting to bluff.

Graphical summary of the filibuster as a war of attrition. Note: If the majority brings a bill to the floor and the minority filibusters, the two enter a war of attrition. If the majority pulls the bill from the floor, it fails. If the minority ends the filibuster, it passes. The filibuster can potentially continue to the end of the session, in which case the bill fails. Each side wants the other to give up first, which may happen if the other side is weak (incurs a cost for staying in the filibuster), but they do not know whether the other side is strong or weak. The longer the filibuster goes on, the more likely it is that the other side is actually strong (does not incur a cost for staying in the filibuster).

Both sides are likely to be strong on polarizing, high-salience issues, where the majority’s supporters clamor for a visible fight to pass the bill and the minority’s supporters demand their legislators do whatever it takes to stop the bill from passing. Both sides are likely to be weak on low-salience issues, where the majority does not get significant political gains to compensate for the floor time it consumes trying to pass the bill and the minority does not get political rewards to compensate for the effort of sustaining the filibuster.[14]

Talking filibusters are especially likely to emerge on both of these kinds of issues, and when they do emerge, they will tend to last for a long time. In the terms of the pool, filibusters arise when both sides are likely to have good wetsuits or both sides are likely to have bad wetsuits.

Talking filibusters are particularly unlikely to emerge on lopsided issues, where one side of the issue is widely popular and the other side’s is not. When they do emerge, they tend to be short. There’s no sense in fighting if your side will probably lose in the end. In other words, if there’s a good chance that one swimmer has a good wetsuit and the other has a bad one, the one who has the bad wetsuit will usually stay out of the pool.

To rephrase the criticisms of the silent filibuster in the terms of the model, the problem is that the majority is usually weak and the minority is usually strong. A talking filibuster deprives the majority of precious floor time that it could use to pass other bills, and the political benefits it gets from the spectacle of the filibuster rarely provide adequate compensation. Under the current rules, a talking filibuster usually doesn’t cost the minority anything. When the minority threatens a filibuster, the majority anticipates the minority will be able to hold out until the bitter end, so it doesn’t bring the bill to the floor in the first place.

So, what of Merkley and Ornstein’s hopes that making filibustering more costly to the minority would reduce filibustering? Under the current rules, the minority is strong if its constituents would reward grinding Senate business to a halt to filibuster the measure. With the reform, the minority would be strong only if those political rewards exceeded the cost of the effort to hold the floor. The reforms would render some otherwise strong minorities weak. They would not influence whether the majority was strong.[15]

Since, under the status quo, the majority is typically weak and the minority is typically strong, the reform would actually increase the frequency of filibusters as well as how long weak parties persist in talking filibusters.[16] To provide a concrete example, suppose a Democratic majority wants to pass an infrastructure bill, but it doesn’t have the 60 votes it needs to invoke cloture. There are other bills it wants to pass, and the party knows that it is better off using floor time to pass those bills rather than spending the whole congress fighting on the infrastructure bill. In other words, the Democratic majority is weak.

Under the current rules, the Democrats anticipate that the Republicans are probably strong. If they try to bring the bill to the floor, the Republicans will filibuster and will ultimately prevail. This deters the Democrats from bringing the bill to the floor in the first place. They succumb to the silent filibuster.

With the reform, the Democrats would be tempted to bluff. They could bring the bill to the floor, hope the Republicans are weak, and hope that those weak Republicans incorrectly infer the Democrats are strong, which would cause them to give up. The bluff would backfire and the Democrats would lose if the Republicans turned out to be strong, but, since the reform increases the chances that the Republicans are actually weak, it encourages the Democrats to bluff more often.

If the Republicans are in fact weak, the very fact that the reform encourages Democrats to bluff more often changes their calculations. They can launch a filibuster, hope that the Democrats are weak, and hope that these weak Democrats incorrectly infer the Republicans are strong, which would cause them to give up. This counterbluff would backfire if the Democrats turned out to be strong, but, since the reform encourages the Democrats to bring the bill to the floor even though they are weak, it encourages the Republicans to counterbluff more often. This bluffing and counterbluffing leads both sides to stay embroiled in the talking filibuster for longer when they are weak, because it makes them more optimistic that the other side is bluffing.

The reform would change the Senate from an institution in which the majority was typically weak and the minority was typically strong to one in which the majority was typically weak and the minority was typically weak as well (or was at least less likely to be strong than it was before the reform). This would make silent filibusters less common, but that is because it encourages weak majorities to bring legislation to the floor when they otherwise would have backed down. These bluffs often lead to talking filibusters that consume floor time when there otherwise would have been a silent filibuster.

That is not to say the reform would make it harder to pass bills. It would make it easier. The majority could still get sixty votes to invoke cloture, just like it can now, but its second option, trying to wear out the minority, would become more effective. The very fact that wearing out the minority would be so much easier would make weak majorities more inclined to try – and to potentially consume a great deal of floor time in the process.

This argument highlights a major strength of game theory: its ability to untangle complex knots of strategic responses. In this case, it is not enough to consider the reform’s first-order effects. It is essential to consider the minority’s strategic response to the majority’s strategic response to the minority’s strategic response to the reform – the third-order effects. Deducing these third-order effects would be very difficult without the guidance of game theory.

4 Abolishing the Filibuster

The simplest and most widely discussed proposal to reform the filibuster is to do away with it altogether and replace it with simple majority cloture. Some of the probable consequences of this change are easy to anticipate even without the assistance of a model. It would unquestionably reduce gridlock, although precisely how much it would reduce gridlock is open to debate (Curry and Lee 2021). It would make it less important to secure the assent of minority party senators to pass legislation, which would probably lead the legislation that does pass to tilt more in favor of the majority party members’ ideological and electoral interests. But other changes are more subtle and become clearer with the guidance of the model. For instance, the model of the filibuster in Krehbiel and Krehbiel (2022) implies that eliminating the filibuster would lead to more conflict between the majority party’s moderates and the Senate Majority Leader.[17]

Krehbiel and Krehbiel argue that the central function of the filibuster, and the reason it has not been abolished via the nuclear option already, is that it counterbalances the fearsome agenda power of the Senate Majority Leader. The Senate’s precedents give the Majority Leader the right of first recognition, meaning that if multiple senators are seeking recognition at the same time, the presiding officer shall recognize the Majority Leader. This gives the Majority Leader a great deal of influence over what the Senate debates, because if any other senator tries to offer a motion to proceed to the consideration of a bill or to amend the bill currently under consideration, the Majority Leader can preempt them by offering a competing motion first.

To understand this argument, imagine a Senate which consists of four groups: extreme liberals, moderate liberals, moderate conservatives, and extreme conservatives. There are forty extreme liberals (including the vice president and the Senate Majority Leader), and they all want a minimum wage of $15 per hour. There are fifteen moderate liberals, each of whom wants a minimum wage of $11 per hour but would still prefer a too-high minimum wage of $12 per hour to leaving the minimum wage at the status quo of $7.25 per hour. There are fifteen moderate conservatives, each of whom wants a minimum wage of $10 per hour. The moderate conservatives would rather raise the minimum wage to $11 per hour than leave it at the status quo of $7.25, but $12 goes too far for them. They would rather leave the minimum wage at $7.25 rather than raise it all the way to $12. The extreme conservatives don’t want any minimum wage at all and will oppose any attempt to increase the minimum wage. Table 6 summarizes the factions and their preferences.

Example for Krehbiel and Krehbiel’s model of the filibuster.

| Faction | Size | Most preferred minimum wage | Highest minimum wage faction would still prefer over status quo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme liberals | 40 | $15 | $20 |

| Moderate liberals | 15 | $11 | $12 |

| Moderate conservatives | 15 | $10 | $11 |

| Extreme conservatives | 30 | $0 | $7.24 |

-

Note: All of the factions except the extreme conservatives want to raise the minimum wage. Each has an ideal minimum wage, but each would also be willing to vote for something even higher than their ideal minimum wage because it would still be better than the unacceptably low (to them) status quo of $7.25. The extreme conservatives, on the other hand, want to eliminate the federal minimum wage. However, they would still vote for any proposal to lower the minimum wage, because it would still be better than the unacceptably high (to them) status quo of $7.25.

In Krehbiel and Krehbiel’s model, the Senate Majority Leader controls the agenda. He decides which bills come to the floor and which amendments are allowed, so, effectively, the Senate has two choices: pass whatever the Senate Majority Leader proposes or leave the minimum wage at the status quo of $7.25. If there were no filibuster, then bills could pass by a simple majority. The Senate Majority Leader could propose his most preferred policy option, a $15 minimum wage, but only the forty extreme liberals would vote for it, and the proposal would fail. His best option is to propose $12. It’s less than the extreme liberals want, but it is the best they can do, so all forty of them would vote for it. It’s more extreme than the moderate liberals want, but it beats $7.25 per hour, which is what they would get if they voted down the bill, so the fifteen moderate liberals would vote for it as well. This 55-senator coalition would be enough to pass the bill.

This $12 proposal is more extreme than most of the legislature would like. The moderate liberals and the conservatives would all prefer $11. If they could amend the leader’s proposal or get their own bill onto the floor, they would propose $11 and the sixty of them would band together to pass it. Unfortunately for them, the Senate Majority Leader controls the agenda and can prevent them from making an amendment or offering their own bill. They are stuck choosing between the leader’s proposal and the status quo, and he exploits this power to give the moderates a stark choice between $12 or the status quo.[18]

The filibuster offers a counterweight to the Senate Majority Leader’s agenda power. With the filibuster, the leader would need sixty votes, and therefore the support of the moderate conservatives, to pass his proposal. $12 is no longer an option; all of the conservatives would band together to filibuster the bill, and the fifty-five liberals would not be able to invoke cloture and pass the bill. Instead, the leader would have to propose to raise the minimum wage to $11 per hour. This is higher than the moderate conservatives would like, but still better for them than the status quo of $7.25, so they would join the liberals to pass the bill seventy to thirty. This is a great deal for everyone but the extreme liberals; all of the other senators prefer the $11 minimum wage they get to the $12 minimum wage they would have gotten if there were no filibuster.

Of course, the numbers do not always work out this way. Two critical features of this example made the filibuster good for the moderate liberals. First, the Senate Majority Leader was extreme. If the Senate Majority Leader had been a moderate liberal, he would have proposed a $11 minimum wage even without the filibuster.[19] Second, the moderate conservatives held the balance of power under the filibuster, and their interests were mostly aligned with the moderate liberals. If there had only been two moderate conservatives and forty-three extreme conservatives, then the filibuster would have prevented the Senate from raising the minimum wage at all, and all of the liberals would have been better off without it. Or, if the moderate conservatives were unwilling to vote for any minimum wage higher than $9 an hour, the moderate Democrats might be better off abolishing the filibuster and getting $12.

This argument underscores an underappreciated aspect of the filibuster. Both of the previous models focus on the role of the filibuster in strategic interactions between the two parties. This model highlights that the filibuster plays a major role in determining the balance of power within the majority party as well. With the filibuster, moderate Democrats like Jon Tester and Mark Kelly need not fear that a liberal like Chuck Schumer would use his control over the agenda to pass policies that are too liberal for their liking. Senator Schumer can’t pass most kinds of legislation without the support from some Republicans, and it is unlikely that a proposal that is acceptable to moderate Republicans would be too liberal for Tester and Kelly. But if the filibuster were abolished, Schumer could present them with tough choices between excessively liberal proposals against unacceptably conservative status quos.

Consequently, replacing the filibuster with simple majority rule would raise the stakes of who led the majority party and how much control that leader had over the Senate’s agenda. Perhaps future leaders would exercise restraint and refrain from using their control over the agenda in a way that antagonized their party’s moderates, but if they did not (and the historical precedent of the elimination of the disappearing quorum in the House of Representatives suggests they would not), conflict between the majority party’s hardliners and a coalition of the minority party and the majority party’s moderates would ensue. For much of the 19th century, members of the House of Representatives took advantage of a tactic known as the disappearing quorum which acted as a de facto supermajority requirement. A slim majority would rarely be able to get enough of their members on the floor to actually make a quorum, so the minority could grind legislative business to a halt by simply refusing to let themselves be counted as present. The House eliminated the disappearing quorum under the leadership of Speaker Thomas Brackett Reed in 1890. Intense within-party conflict over control of the House’s agenda did not come until Speaker Joseph Cannon (1903–1911) used it in a manner that antagonized the progressive faction within the Republican Party. The ensuing revolt against Cannon gutted the Speaker’s control over the House’s agenda and led him to resign.

As in the House over a century ago, the majority party moderates might try to oust extreme leaders and replace them with moderate leaders, or they might band with the minority to attack the Majority Leader’s control over the Senate’s agenda. When they consider eliminating the filibuster, the majority party’s moderates would do well to remember that sweeping minority party obstructionists aside would also deprive them of one of their most surefire defenses against extreme members of their own party. Perhaps giving the Senate Majority Leader leverage to pass more extreme policies is better than passing no policy at all, but in that case, moderates may try to tie their support for abolishing the filibuster to rule changes that weaken the leader’s control over the agenda.

5 Conclusions

The Senate is a complicated institution. This complication calls for contributions from all kinds of social scientists using all kinds of approaches, including qualitative and historical researchers, quantitative empiricists, and formal theorists. The comparative advantage of formal theory is that it suggests possibilities that the researcher might not have guessed on their own. Table 7 summarizes the results.

Summary of the models’ predictions.

| Reform | Model | Predictions |

|---|---|---|

| Ratcheting cloture | Fong and Krehbiel (2018) | Increases degree to which majority caters to minority’s preferences (compared to no filibuster), but no effect on majority’s top priorities |

| Increase cost minority incurs during filibusters |

Dion et al. (2016) | Increases frequency and duration of filibuster |

| Abolish the filibuster | Krehbiel and Krehbiel (2022), Judd and Rothenberg (2021) | Increases conflict over leadership contests and Majority Leader’s control over the agenda |

The analysis of ratcheting cloture with Fong and Krehbiel’s theory of limited obstruction integrates different perspectives and offers sharp predictions about where each perspective applies. Different experts have suggested that ratcheting cloture would lead the majority to steamroll the minority, compromise with the minority, or capitulate to the minority. The model shows how the reform would lead to all three. On its top priorities, the majority would steamroll. On lesser priorities, it would capitulate on bills that were not particularly important to it but were noxious to the minority. In exchange, the majority would get to pass more bills that it likes and the minority does not especially hate, and the extra productivity that resulted from this compromise would compensate the majority for the bills on which it capitulated.

The analysis of the talking filibuster as a war of attrition, as in Dion et al. (2016), untangles strategic interactions between players. Intuitively, it seems that making filibustering more costly ought to lead the minority to filibuster less often, but it is important to consider how this influences the majority’s incentives to pick filibuster fights even when they are very painful to the majority, which in turn influences the minority’s incentive to try to outlast the majority. Reforms that make filibustering more painful for the minority can thereby actually increase both the number of filibusters and how long they last when they occur.

The analysis of abolishing the filibuster, following Krehbiel and Krehbiel (2022), questions why the Senate has the filibuster in the first place and then uses the answer to this question to show what could happen in a post-filibuster Senate. The filibuster protects the majority party’s moderates from the Senate Majority Leader. Were it not for the filibuster, the Majority Leader could use his control over the agenda to force the majority party’s moderates to choose between policies that are more extreme than they would like or the status quo. Consequently, abolishing the filibuster would bring the majority party’s moderates into conflict with the Senate Majority Leader and would encourage fights over who gets to be leader and the precedents that give the leader control over the agenda.

None of the arguments above speak to which of the proposed reforms is best, or whether any of them are better than the status quo, but discussions of reform should think as carefully as possible about their consequences. These stylized representations of the Senate, the lawmaking process, and the reform proposals cannot definitively establish how senators would behave under the reform, but they make transparent, logical arguments that identify possibilities – possibilities that might otherwise have been difficult to notice. Given the stakes of changing an institution as central to the operation of American government as the filibuster, these possibilities deserve careful consideration from reformers.

References

Ainsworth, S., and M. Flathman. 1995. “Unanimous C1onsent Agreements as Leadership Tools.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 20 (2): 177–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/440446.Search in Google Scholar

Barnes, M., N. Eisen, J. Mandell, and N. Ornstein. 2021. Filibuster Reform Is Coming—Here’s How. Technical Report, Brookings Institution.Search in Google Scholar

Bawn, K., and G. Koger. 2008. “Effort, Intensity and Position Taking: Reconsidering Obstruction in the Pre-cloture Senate.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 20 (1): 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629807084040.Search in Google Scholar

Binder, S. 2022. “Marching (Senate Style) towards Majority Rule.” The Forum 19 (4): 663–84. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2022-2039.Search in Google Scholar

Binder, S. A., E. D. Lawrence, and S. S. Smith. 2002. “Tracking the Filibuster, 1917 to 1996.” American Politics Research 30 (4): 406–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x02030004003.Search in Google Scholar

Binder, S. A., A. J. Madonna, and S. S. Smith. 2007. “Going Nuclear, Senate Style.” Perspectives on Politics 5 (4): 729–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592707072246.Search in Google Scholar

Binder, S. A., and S. S. Smith. 1997. Politics or Principle?: Filibustering in the United States Senate. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.Search in Google Scholar

Curry, J. M., and F. E. Lee. 2021. “One Obstacle Among Many: The Filibuster and Majority Party Agendas.” The Forum 19 (4): 685–708. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2021-2033.Search in Google Scholar

Dion, D. 1997. Turning the Legislative Thumbscrew: Minority Rights and Procedural Change in Congress. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.14912Search in Google Scholar

Dion, D., F. J. Boehmke, W. MacMillan, and C. R. Shipan. 2016. “The Filibuster as a War of Attrition.” The Journal of Law and Economics 59 (3): 569–95. https://doi.org/10.1086/690223.Search in Google Scholar

Fong, C. 2022. “Rules and the Containment of Conflict in Congress.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 47 (4): 959–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12368.Search in Google Scholar

Fong, C., and K. Krehbiel. 2018. “Limited Obstruction.” American Political Science Review 112 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055417000387.Search in Google Scholar

Franken, A., and N. Ornstein. 2021. Make the Filibuster Great Again. Minneapolis, MN: Star Tribune.Search in Google Scholar

Gailmard, S., and T. Hammond. 2011. “Intercameral Bargaining and Intracameral Organization in Legislatures.” The Journal of Politics 73 (2): 535–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381611000338.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbs, D. 2022. The Reputation Politics of the Filibuster. Princeton, NJ: Unpublished Manuscript.10.1561/100.00020109Search in Google Scholar

Gould, J. S., K. A. Shepsle, and M. C. Stephenson. 2021. “Democratizing the Senate from within.” Journal of Legal Analysis 13 (1): 502–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/laab005.Search in Google Scholar

Harkin, T. 2011. “Filibuster Reform: Curbing Abuse to Prevent Minority Tyranny in the Senate.” NYU Journal of Legislation and Public Policy 14: 1.Search in Google Scholar

Jentleson, A. 2021. Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy. New York: Liveright.Search in Google Scholar

Judd, G., and L. S. Rothenberg. 2021. The waning and Stability of the Filibuster. Rochester, NY: Unpublished Manuscript.Search in Google Scholar

Koger, G. 2010. Filibustering: A Political History of Obstruction in the House and Senate. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226449661.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Krehbiel, K., and S. Krehbiel. 2022. “The Manchin Paradox.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00021165.Search in Google Scholar

Ornstein, N. 2020. “The Smart Way to Fix the Filibuster.” In The Atlantic. Washington, DC: The Atlantic Monthly Group.Search in Google Scholar

Overby, L. M., and L. C. Bell. 2004. “Rational Behavior or the Norm of Cooperation? Filibustering Among Retiring Senators.” The Journal of Politics 66 (3): 906–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2004.00282.x.Search in Google Scholar

Patty, J. W. 2016. “Signaling through Obstruction.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (1): 175–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12202.Search in Google Scholar

Primo, D. M. 2002. “Rethinking Political Bargaining: Policymaking with a Single Proposer.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 18 (2): 411–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/18.2.411.Search in Google Scholar

Schickler, E., and G. J. Wawro. 2011. “What the Filibuster Tells Us about the Senate.” The Forum 9 (4): 1–15, https://doi.org/10.2202/1540-8884.1483.Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, B. 2013. “The New World of U.S. Senators.” In Congress Reconsidered, edited by L. C. Dodd, and B. I. Oppenheimer, 1–26. Washington: CQ Press.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, S. S. 2022. “Senate Republican Radicalism and the Need for Filibuster Reform.” The Forum 19 (4): 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2021-2032.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, S. S., and M. H. Park. 2013. “Americans’ Attitudes about the Senate Filibuster.” American Politics Research 41 (5): 735–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x13475472.Search in Google Scholar

Wawro, G. J., and E. Schickler. 2004. “Where’s the Pivot? Obstruction and Lawmaking in the Pre-cloture Senate.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 758–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00100.x.Search in Google Scholar

Wawro, G. J., and E. Schickler. 2006. Filibuster: Obstruction and Lawmaking in the U.S. Senate. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Anticipating the Consequences of Filibuster Reforms

- Conspiracy Theories in the US: Who Believes in Them?

- Does Malapportionment Favor the Republican Party?

- Electoral Dynamics for 2022: The House of Representatives in the Modern Era

- Racial Bias and U.S. Presidential Candidate Preference

- Book Review

- Alison W. Craig: The Collaborative Congress: Reaching Common Ground in a Polarized House

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Anticipating the Consequences of Filibuster Reforms

- Conspiracy Theories in the US: Who Believes in Them?

- Does Malapportionment Favor the Republican Party?

- Electoral Dynamics for 2022: The House of Representatives in the Modern Era

- Racial Bias and U.S. Presidential Candidate Preference

- Book Review

- Alison W. Craig: The Collaborative Congress: Reaching Common Ground in a Polarized House