Abstract

The effects of sepiolite on fire behavior of ammonium polyphosphate-based intumescent flame retardant (IFR)/polypropylene (PP) were investigated. The disaggregation of sepiolite bundles has been provided by wet-milling as the zeta potential value decreased from −9.6 to −31.3 mV. PP and additives were compounded by a twin-screw extruder and molded by injection. A total additive content of 20 wt% in PP and various proportions of sepiolite (1.0–10.0 wt%) in flame retardant (FR) formulation were studied. The flammability of the samples was measured by limit oxygen index (LOI) test and cone calorimetry. The LOI of neat PP (19%) was increased to 32.2% when sepiolite and IFR were used. The peak heat release rate of neat PP (1566.4 kW/m2) was also significantly reduced (94.7 kW/m2) when sepiolite was added with IFR. Thermal analyses results showed that, at higher temperature (700°C), IFR and sepiolite increased the char residue (9 wt%) compared to neat PP (0 wt%).

1 Introduction

Polypropylene (PP) has attracted the interest of packaging, automotive, medical and textile industries in the last few decades because of ease of processing and low cost features. PP fibers have been widely used in textiles because of their low specific gravity, high strength, chemical and stain resistance features (1). However, PP burns rapidly, without leaving a char residue due to its wholly aliphatic carbon structure (2). Flame retardant (FR) materials such as halogenated, phosphorus and metallic compounds have been used to increase FR properties of PP. However, because of the environmental and health concerns the use of halogenated FR materials, in particular, is becoming increasingly limited (3). Therefore, there is an increasing demand for the development of novel and efficient alternative FR systems. Intumescent flame retardant (IFR) systems have been considered as alternative FRs for polyolefins because of their low smoke generation, low release of toxic gases and antidripping properties (4). A very well-known IFR system is PP containing ammonium polyphosphate (APP)/pentaerythritol or an intumescent commercial additive such as Exolit AP750, Clariant (APP with an aromatic ester of tris(2-hydroxyethyl)-isocyanurate at 30 wt% loading) (5). The relatively low FR efficiency of IFR systems requires the use of more additives at higher concentrations, which may further impair the mechanical properties of materials that is a major concern for textile applications in particular. Various inorganic materials such as sepiolite (6), montmorillonite (7), zinc borate (8, 9), zeolite (10, 11) and lanthanum oxide (12) have been used as synergists to improve the FR properties of IFR/PP system. The synergistic action of metal containing compounds with APP has been attributed to the interaction of polyphosphoric acid formed during the thermal decomposition of APP and metal containing compounds (13). The metal cations favor the cross-linking of polyphosphoric acid, thus increasing its viscosity leading to a more thermally stable char. However, the excessive use of metal containing inorganic compounds may cause the cracking of char, which acts as an insulating layer.

The concentration of additives may be reduced by incorporating synergists to the formulation and thus increasing the FR efficiency. In this study, the effect of a nonswelling clay, sepiolite, on the fire retardant behavior of various IFR-PP formulations was studied to investigate potential sepiolite-IFR interactions that will lead to the reduction of the total additives used. Sepiolite is a fibrous magnesium silicate with the theoretical half unit-cell formula Si12O30Mg8(OH)4·(H2O)4·8H2O, and the structure is constituted by a central magnesium octahedral sheet enclosed by two tetrahedral silica layers, which extend as a continuous layer with an inversion every six units. This inversion provides the formation of rectangular nanostructured channels parallel to the fiber axis. The particular alignment of atoms produces a needlelike structure, which accounts for the compatibility with polymeric matrices because of their less particle-particle contact area than layered clays. Thanks to its high thermal stability and mechanical strength, it has been used as a reinforcement for many polymers (14, 15). The clay layers can be individually dispersed in the polymer matrix either by exfoliation or intercalation providing that the surface of layers is compatible with the polymer (7, 16). However, in case of nonpolar polymers such as PP, exfoliation or intercalation cannot be achieved because of the lack of affinity between the hydrophilic clay and the hydrophobic polymer (17). Therefore, the clay surfaces should be made hydrophobic in order to facilitate exfoliation. Sepiolite surface can be modified by adsorption of quaternary ammonium salts or amines, grafting by silane reagents (14). Recently, organomodified sepiolite was prepared by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide treatment and used as a synergist in IFR PP (18). Compared to untreated sepiolite, organomodified sepiolite showed a better synergy with IFR-PP in limit oxygen index (LOI), UL-94 rating and pHRR. Micronization was reported to enhance the interaction between sepiolite and polymer by decreasing the agglomeration tendency of the bundles of microfibers (19). Furthermore, it has been previously reported that maleic anhydrite-grafted PP (MAPP) may be required to provide dispersion of clays in PP because of the strong hydrogen bonding between oxygen groups of clay and hydroxyl or carboxyl groups (20, 21). Previously, the potential of ball milling to improve the dispersion of clays in PP was investigated. It was stated the exfoliation could be provided by high-energy milling (17, 22). However, no studies on the thermal and fire behavior of polymers containing milled clays, to authors knowledge, have been reported. In this study, pristine sepiolite has been milled by a simple planetary milling process prior to use in order to provide the dispersion of clays. The thermo-oxidative behavior of PP containing IFR and sepiolite has been extensively studied by TGA/DTG analysis.

2 Materials and methods

APP-based IFR (Exolit AP 760, Clariant Plastics and Coatings AG, Germany) and Eskisehir sepiolite (SEP, Ceramic Research Center, Eskişehir, Turkey) were used to increase FR properties of isotactic PP. Isotactic PP was kindly supplied by Clarinat Plastics and Coatings AG, Germany. Eskisehir sepiolite was wet milled by planetary mill (Pulverisette 5, Fritsch GmbH, Germany) under ambient conditions using ethanol (Merck KGaA, Germany, %96) as the dispersing medium. Eighty grams of ethanol-sepiolite suspension with a density of 1.15 g/cm3 was fed to 250 ml grinding bowl and milled using balls (d=3 mm) both made of ZrO2 at a rate of 300 rpm for 60 min. After that ethanol was removed by evaporation under vacuum. Particle size measurement was performed using a zetasizer (Nano ZS 3600, Malvern, UK). The instrument software (ZetaSizer, Malvern, UK) was utilized to calculate zeta potential by the Hückel approximation. Morphology of sepiolite was analyzed by SEM (Supra 50 VP, Carl Zeiss, Germany) after Au-Pt coating under 20 kV beam voltage.

PP and additives were compounded by a twin-screw extruder operated with a constant temperature profile of 170°C and molded by injection (Tmelt=175°C, Pinjection=8 bar) (Microcompounder, Xplore Instruments BV, The Netherlands). The total content of FRs was kept constant (20 wt%) and APP-based IFR was replaced by 1.0, 2.5, 5.0 and 10.0 wt% sepiolite in the FR formulation. MAPP was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany and used to improve the compatibility of additives with the PP matrix. The effect of MAPP (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany) in the ratio of 5% on the flammability of composites was studied.

The flammability of specimens (80 mm×10 mm×4 mm) was measured according to ASTM D2863 in terms of LOI using an LOI test apparatus (Dynsco, USA). The flammability parameters of the samples were measured by cone calorimeter (Fire Testing Technology Ltd., UK) according to ISO 5660 under a heat flux of 35 kW/m2. Test specimens (100 mm×100 mm×3 mm) were not wrapped with aluminum foil, instead they were analyzed on aluminum boots (trays) because of the dripping of PP during melting as proposed earlier (23). Simultaneous thermal analysis were performed by SDT (SDT Q600, TA Instruments, USA) up to 1000°C under airflow (100 ml/min). In order to perform a detailed scanning the heating rate of 5°C/min was chosen between 300°C and 600°C since most of the degradation processes occur within this temperature range, the heating range was set as 10°C/min outside of this temperature range using the instrument software. Approximately 10 mg of sample was used for each test and the results were interpreted using the Universal Analysis 2000 software (TA Instruments, USA).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of sepiolite

Zeta potential is an electrokinetic property of a substance that is used to explain the dispersion and agglomeration behavior of a substance (24). The zeta potential/size analysis results for SEP before/after milling can be seen in Table 1. The zeta potential of SEP particles was shifted away from the isoelectric point after milling. This result is an indication of the degree of dispersion of sepiolite aggregates, which may further enhance the dispersion of the clay in PP.

Zeta/size measurement results of SEP (Z-average: particle size; PdI, polydispersity index).

| Sepiolite | Z-avg (r.nm) | PdI | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before milling | 3228 | 0.369 | −9.6 |

| After milling | 785 | 0.801 | −31.3 |

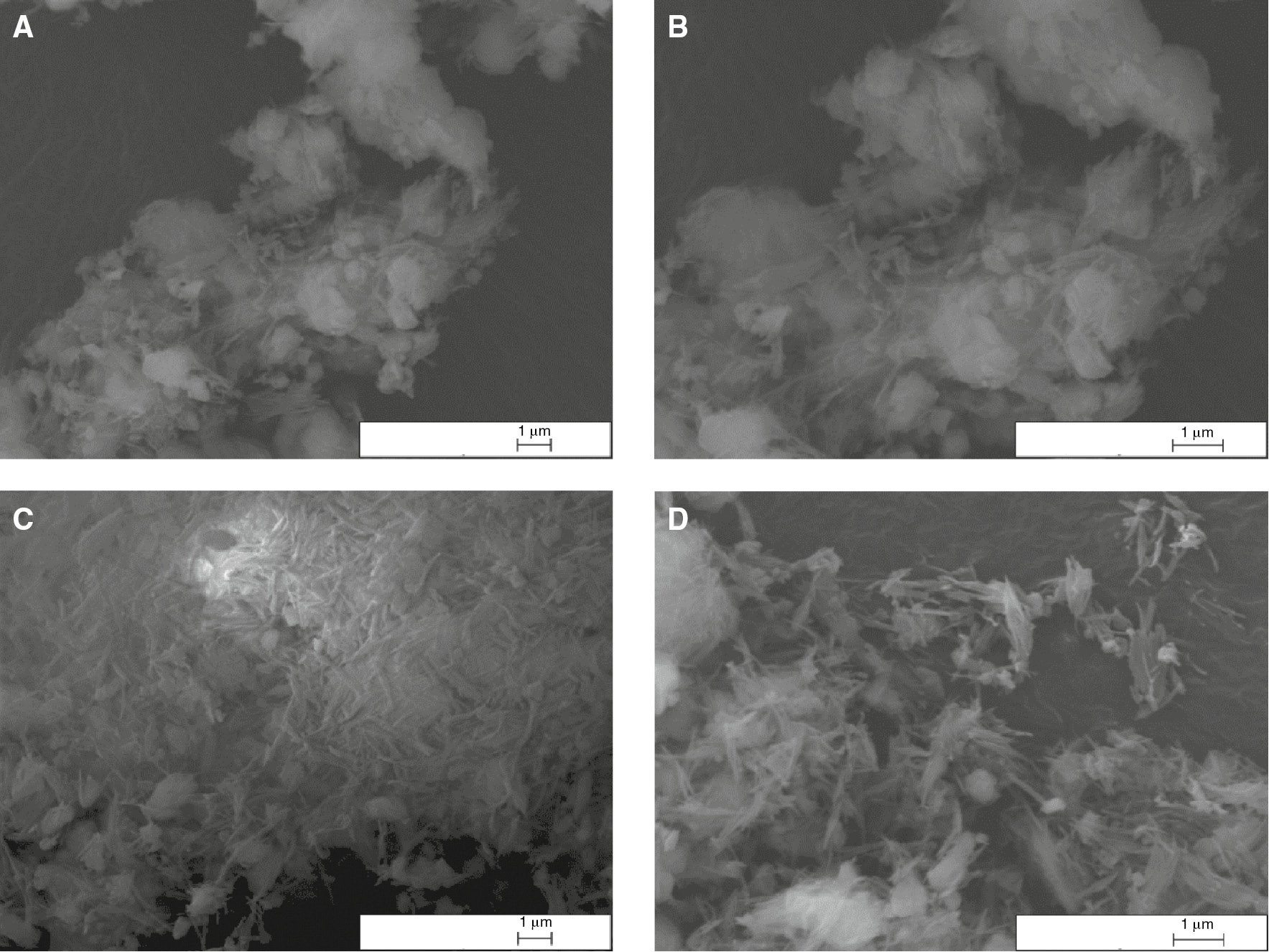

SEM micrographs of sepiolite before/after milling are given in Figure 1. The presence of needlelike particles has been approved by the SEM images. Moreover, the disaggregation of the bundles is apparent when SEM image of sepiolite before milling (Figure 1B) is compared to SEM image of sepiolite after milling (Figure 1D).

SEM micrographs of sepiolite before milling at (A) 20000 ×, (B) 30000 ×, after milling at (C) 20000 ×, (D) 30000 × magnification.

3.2 LOI tests

LOI test is performed to determine the relative flammability of substances tested in vertical position and subjected to top surface ignition. LOI value is defined as the minimum concentration of oxygen by volume in a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen that either will support the combustion of a material for 3 min or consume 50 mm of the material (25). The compositions of polymer samples and the effect of increasing sepiolite content on the LOI of IFR system can be seen in Table 2. The LOI value of neat PP (19%) increased to 28% by the addition of 20 wt% IFR (PP/IFR20) and increased further to 32.2% when 2.5 wt% IFR was replaced by sepiolite in FR formulation (PP/IFR20/SEP2.5). Addition of SEP (10 wt%) did not further increase the LOI as in this case the content of APP-based FR was decreased by 1% in the PP composite. Because of the decreasing amount of APP-based FR, the synergistic effect of sepiolite could no longer be observed in terms of LOI. Therefore, the effective sepiolite content in FR formulation was determined as 2.5%. Moreover, the addition of MAPP clearly did not enhance the fire properties of PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 system as the LOI value decreased to 27.8%. Although MAPP could have provided a better dispersion of clays in the polymer matrix by promoting intercalation (26), it was concluded to present antagonistic effects on the LOI of composites.

Sample compositions.

| Samples | PP wt% | MAPP% | SEP wt% | APP wt% | LOI% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 100 | – | – | – | 19 |

| PP/IFR20/SEP1 | 80 | – | 0.2 | 19.8 | 31.7 |

| PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 | – | 0.5 | 19.5 | 32.2 | |

| PP/IFR20/SEP5 | – | 1 | 19 | 29.8 | |

| PP/IFR20/SEP10 | – | 2 | 18 | 28.4 | |

| PP/IFR20 | – | – | 20 | 28 | |

| PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 | 75 | 5 | 0.5 | 19.5 | 27.8 |

3.3 Cone calorimeter

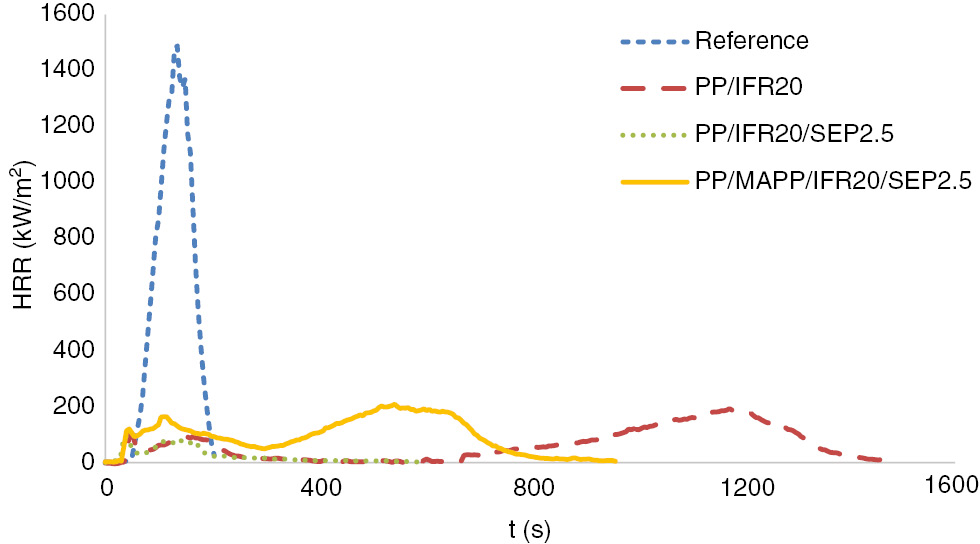

The rate of heat released from a material is a useful tool to evaluate its fire behavior. The heat release rate (HRR) curve represents the fire behavior driven by the intrinsic properties of the material (char yield, effective heat of combustion, etc.), the properties of the specimen (thickness, deformation, etc.) and the physical and chemical mechanisms controlling during burning (endothermic reactions, release of radicals, etc.) (23). HRR of reference PP, PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 were measured by the cone calorimeter and HRR curves are shown in Figure 2.

HRR curves of the samples.

In general, intumescent systems interfere with the self-sustained combustion of polymer at early stages and lead to the formation of char and foam on polymer surface (13). The sharp HRR curve of neat PP is typical for noncharring materials (27). Obviously, IFR system has provided formation of a char layer as several HRR peaks were obtained for PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 samples. The char layer formed acts as a physical barrier between gas and condensed phases and slows down the heat and mass transfer to the sample (13). The formation of the second HRR peak observed for samples PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFER20/SEP2.5 may be attributed to the condensed phase activity of the IFR and IFR/sepolite system. Important flammability parameters such as time to ignition (TTI), peak heat release rate (pHRR), CO and CO2 yield were also measured by the cone calorimeter and are tabulated in Table 3. From the cone calorimeter data, total heat evolved per total mass loss (THE/TML) for samples was calculated and also tabulated in Table 3.

Time to ignition (TTI), peak heat release rate (PHRR), average mass loss rate (avMLR), total heat evolved/total mass loss (THE/TML), CO and CO2 release data of samples.

| Samples | TTI (s) | pHRR (kW/m2) | avMLR (g/s) | THE/TML (MJ/m2·g) | av CO yield (kg/kg) | avCO2 yield (kg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 52 | 1566.40 | 0.143 | 4.77 | 0.047 | 2.624 |

| PP/IFR20 | 42 | 193.49 | 0.016 | 3.94 | 0.057 | 2.033 |

| PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 | 30 | 94.68 | 0.009 | 2.69 | 0.042 | 1.529 |

| PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 | 34 | 209.29 | 0.026 | 3.90 | 0.050 | 2.286 |

The TTI measured for PP/IFR20 (42 s) was lower compared with the TTI of neat PP (52 s). The lowering of TTI suggests that the addition of IFR leads to a rapid increase in the surface temperature of sample because of the formation of a char layer, which then results in the fast decomposition of PP as explained previously (6). The TTI was further reduced for PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 (30 s). This result indicates that the clay particles catalyze the decomposition of PP at the early stages (28). The TTI value of PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 (34 s) was higher compared to the sample prepared without MAPP. The pHRR is defined as a numerical indicator of the intensity of a fire (29). The pHRR of PP (1566.40 kW/m2) was significantly reduced when IFR was incorporated into the PP. The substitution of sepiolite also caused a further decrease in pHRR. The peak of HRR of neat PP (1566.40) was greatly reduced with the incorporation of FRs. The pHRR of PP/IFR20 was 193.49 kW/m2, which improved by 51% for PP/IFR20/SEP2.5.

THE/TML is defined as the heat of combustion of volatiles multiplied by the combustion efficiency and is a good indicator of gas phase activity of FR (30). THE/TML values calculated for reference PP, PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 are also shown in Table 3. THE/TML of reference PP (4.77) is higher than PP/IFR20 (3.94). Further reduction of THE/TML exhibited by PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 (2.69) may be due to the formation of a more stable char layer in addition to dilution of the fuel.

The CO production rate (g/s) is defined as the product of CO yield (kg/kg) and mass loss rate (g/s) (31). The average CO production rates of reference PP, PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 were 6.8, 0.9, 0.4 and 1.3 mg/s, respectively. The average CO2 production rates of reference PP, PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 were 376.5, 32.7, 14.3 and 58.6 mg/s, respectively. When FRs were added, both CO and CO2 production rates decreased. The incorporation of sepiolite reduced the CO2 production rate of IFR-PP system.

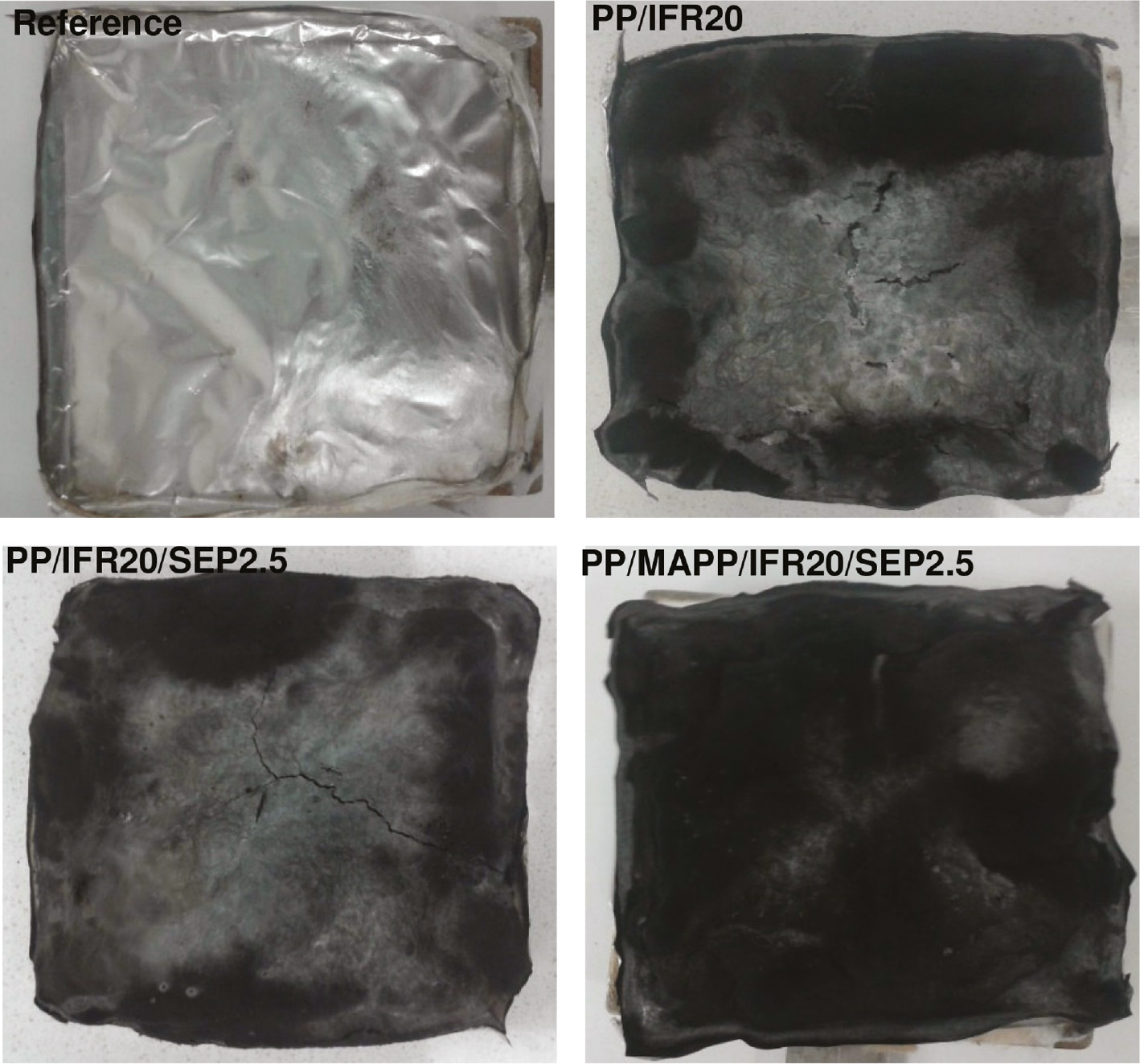

The residue images of reference PP, PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 samples after cone calorimeter tests are shown in Figure 3. No char formation was observed for neat PP, whereas intumescent char formation was detected for PP/IFR20. A more stable char that acted as a barrier to heat transfer was observed for PP/IFR20/SEP2.5.

Residues after cone calorimeter tests.

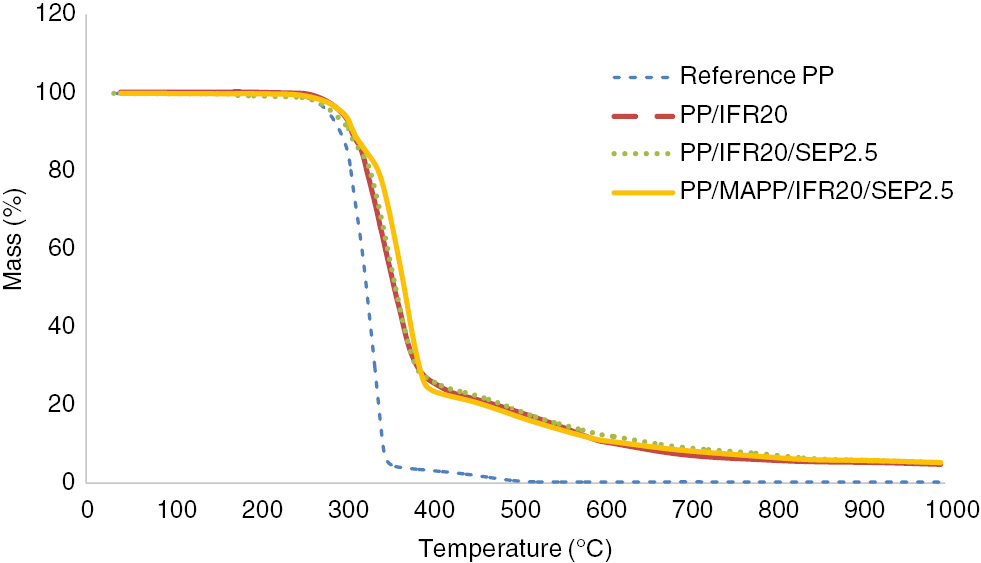

3.4 Thermal analysis

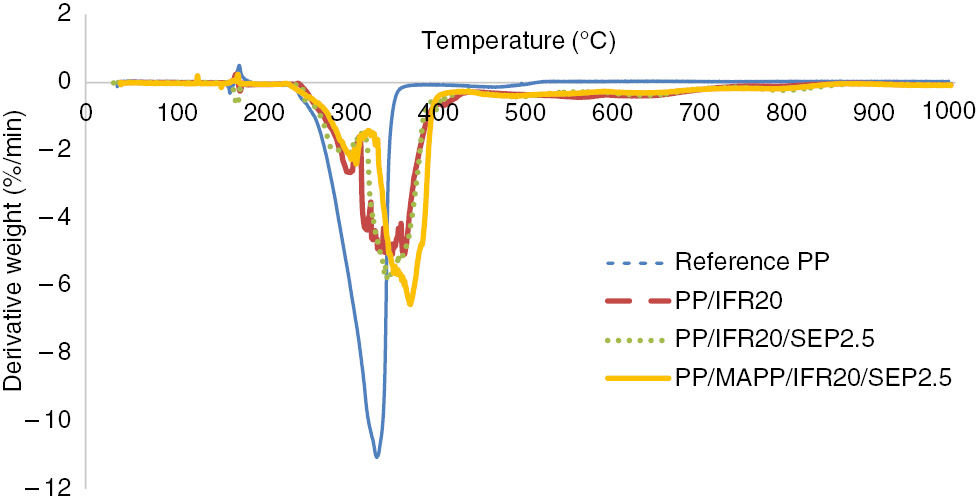

Thermo-oxidative behaviors of reference PP, PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 samples were studied by thermogravimetric analysis under airflow. The results are shown in Figures 4 and 5 . The one-step degradation of reference PP initiated at 255°C, and only 4.3% of the initial mass remained at 357°C, which was then removed completely at approximately 500°C. A four-step mechanism for the degradation of intumescent-PP system has been reported by the others (32). The additives react to form phosphate esters starting from 230°C, and the intumescence is developed between 280°C and 350°C. The degradation of intumescent char layer occurs between 350°C and 430°C, and new carbonaceous species are formed. The existence of a protective shield is mentioned between 430°C and 560°C, which is not protective at higher temperatures. The degradation of PP/IFR20 sample initiated at 260°C, and a high rate of decomposition was observed up to 420°C. The mass residue at 420°C was 23.5%. Between 420°C and 600°C, a lower rate of decomposition was observed, which may be related to the protective layer that acts as a heat transfer barrier. The mass loss above this temperature was attributed to the decomposition of protective char layer. At 700°C, the residual mass was 7%, and a thermally stable residue was obtained between 700°C, the 1000°C. Moreover, the addition of sepiolite to the intumescent PP system (PP/IFR20/SEP2.5) did not change the onset temperature of decomposition significantly (Table 4). However, a more stable residue was obtained at higher temperatures, the residual mass being 9% at 700°C, and the incorporation of MAPP has slightly increased the onset decomposition temperature. However, the residual mass of PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 sample was lower than PP/IFR20/SEP2.5.

TG results of the samples under airflow.

DTG results of the samples under airflow.

Thermogravimetric data of the samples.

| Samples | T10% | T90% | Residue @ 700°C (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 297 | 346 | 0 |

| PP/IFR20 | 309 | 611 | 7 |

| PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 | 307 | 662 | 9 |

| PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 | 312 | 628 | 8 |

The highest rate of decomposition was attained by reference PP at 335°C, and its value was 11%/min (Figure 5). Two different rate steps were observed for the degradation of PP/IFR, PP/IFR/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 samples. At the lower rate degradation step, the peak values for PP/IFR, PP/IFR/SEP2.5 and PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 samples were 2.6%, 2.1% and 2.3% per minute at 303°C, 299°C and 310°C, respectively (Figure 5). The lowest rate of decomposition was observed for PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 sample at this step. At the higher rate degradation step, a sharp peak was observed for PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 samples at 373°C, and its value was 6.5%/min. MAPP is thought to catalyze the degradation of PP during the preparation of composites (10). Broader peaks were observed for PP/IFR and PP/IFR/SEP2.5.

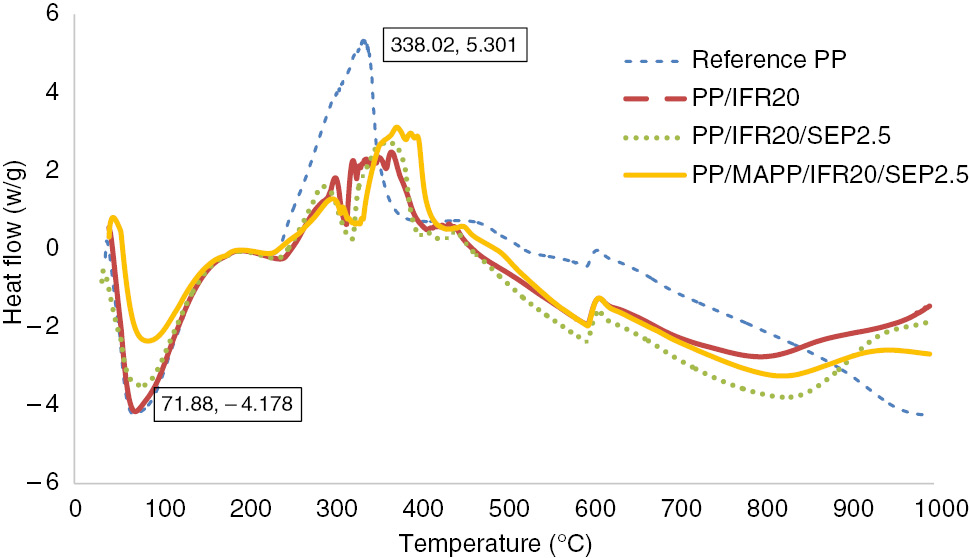

Thermal transitions of reference PP and FR-PP samples were recorded by DSC analysis, and the results are shown in Figure 6. A strong exothermic peak was evolved for neat PP between 235°C and 400°C. Up to 255°C, this exothermic behavior was not accompanied by mass loss, which is typical to thermo-oxidative degradation of weakly stabilized PP (33). Above 255°C, the exothermic signal can be related to decrease in the heat capacity of the sample because of mass loss. Two successive exothermic peaks were observed for FR incorporated samples PP/IFR20, PP/IFR20/SEP2.5, PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5. The first exothermic peak starting from 239°C for PP/IFR20 represents the degradation of neat PP and the generation of intumescence. The second exothermic peak that initiates at approximately 320°C stands for the degradation of intumescent char.

DSC results of the samples under airflow.

4 Conclusions

The effect of sepiolite on the IFR PP system was investigated. The dispersion of clays in polymer, which is a major challenge in the combination of clays and polymers, was enhanced by applying a simple planetary ball milling procedure. As the zeta potential measurements suggest; after ball milling, sepiolite bundles were disaggregated. The particle size of sepiolite was also slightly reduced.

The formation of a char layer, which acts as a barrier for the transfer of heat and oxygen to the sample, was provided by PP/IFR20 as confirmed by several HRR peaks observed in cone calorimeter analyses (Figure 2). APP-based IFR improved the flammability properties of PP as the peak of HRR was reduced, and LOI was increased compared to the neat PP. When APP-based IFR was replaced by sepiolite (2.5 wt%), the flammability of the composite was improved in terms of LOI. The peak of heat release was also reduced from 193.49 kW/m2 (PP/IFR20) to 94.68 kW/m2 (PP/IFR20/SEP2.5). The residual mass at 700°C was also higher for PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 (9 wt%) compared to PP/IFR20 (7 wt%). Such increment was previously reported to have been resulted from the deceleration of loss of phosphoric acid fragments in the presence of clays (12). The thermal decomposition of PP/IFR20 and PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 initiated at approximately 260°C and continued with a high rate until 420°C. Above 420°C, a lower rate of decomposition was observed.

When 5 wt% PP was replaced by MAPP (PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5), the LOI of PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 was not further improved. The peak HRR of PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 (209.29 kW/m2) was also higher than the peak HRR of PP/IFR20/SEP2.5. Thermo-oxidative stability of PP/IFR20/SEP2.5 was reduced when MAPP was incorporated to the system, as the residual mass of PP/MAPP/IFR20/SEP2.5 was 8 wt%. Overall, the addition of MAPP did not improve the flammability of PP/IFR20/SEP2.5, possibly because of the increasing amount of combustibles.

Sepiolite can be incorporated into the PP matrix successfully as a synergist to IFRs after a simple planetary milling process.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Anadolu University Scientific Research Projects Commission under grant no. 1406F324.

References

1. Kissel WJ, Han JH, Meyer JA. Polypropylene: Structure, properties, manufacturing processes and applications. In: Karian HG, ed. Handbook of Polypropylene and Polypropylene Composites. USA: Marcel Dekker. Inc; 1999. 15–38.Search in Google Scholar

2. Zhang S, Horrocks AR. A review of flame retardant polypropylene fibres. Prog Polym Sci. 2003;28:1517–38.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2003.09.001Search in Google Scholar

3. Zaikov GE, Lomakin SM. Ecological issue of polymer flame retardancy. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;86:2449–62.10.1002/app.10946Search in Google Scholar

4. Liu Y, Zhao J, Deng C-L, Chen L, Wang D-Y, Wang Y-Z. Flame-retardant effect of sepiolite on an intumescent flame-retardant polypropylene system. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2011;50:2047–54.10.1021/ie101737nSearch in Google Scholar

5. Bourbigot S, Duquesne S. Intumescence and nanocomposites: a novel route for flame-retarding polymeric materials. In: Morgan AB, Wilkie CA, (eds.). Flame Retardant Polymer Nanocomposites. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. 131–62.10.1002/9780470109038.ch6Search in Google Scholar

6. Huang NH. Synergistic effects of sepiolite on intumescent flame retardant polypropylene. Express Polym Lett. 2010;4:743–52.10.3144/expresspolymlett.2010.90Search in Google Scholar

7. Yi D, Yang R. Ammonium polyphosphate/montmorillonite nanocompounds in polypropylene. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;118: 834–40.10.1002/app.32362Search in Google Scholar

8. Fontaine G, Bourbigot S, Duquesne S. Neutralized flame retardant phosphorus agent: facile synthesis, reaction to fire in PP and synergy with zinc borate. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2008;93:68–76.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2007.10.019Search in Google Scholar

9. Samyn F, Bourbigot S, Duquesne S, Delobel R. Effect of zinc borate on the thermal degradation of ammonium polyphosphate. Thermochim Acta 2007;456:134–44.10.1016/j.tca.2007.02.006Search in Google Scholar

10. Demir H, Balköse D, Ülkü S. Influence of surface modification of fillers and polymer on flammability and tensile behaviour of polypropylene-composites. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2006;91:1079–85.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2005.07.012Search in Google Scholar

11. Demir H, Arkış E, Balköse D, Ülkü S. Synergistic effect of natural zeolites on flame retardant additives. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2005;89:478–83.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2005.01.028Search in Google Scholar

12. Li Q, Jiang P, Su Z, Wei P, Wang G, Tang X. Synergistic effect of phosphorus, nitrogen, and silicon on flame-retardant properties and char yield in polypropylene. J Appl Polym Sci. 2005;96:854–60.10.1002/app.21522Search in Google Scholar

13. Levchik SV. Introduction to flame retardancy and polymer flammability. In: Morgan AB, Wilkie CA, (eds.). Flame Retardant Polymer Nanocomposites. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. 131–62.10.1002/9780470109038.ch1Search in Google Scholar

14. Tartaglione G, Tabuani D, Camino G. Thermal and morphological characterisation of organically modified sepiolite. Micropor Mesopor Mat. 2008;107:161–8.10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.04.020Search in Google Scholar

15. Alonso Y, Martini RE, Iannoni A, Terenzi A, Kenny JM, Barbosa SE. Polyethylene/sepiolite fibers. Influence of drawing and nanofiller content on the crystal morphology and mechanical properties. Polym Eng Sci. 2015;55:1096–103.10.1002/pen.23980Search in Google Scholar

16. Pantoustier N, Alexandre M, Degée P, Calberg C, Jérôme R, Henrist C, Cloots R, Rulmont A, Dubois P. Poly(e-caprolactone) layered silicate nanocomposites: effect of clay surface modifiers on the melt intercalation process. e-Polymers 2001;1:77–85.10.1515/epoly.2001.1.1.77Search in Google Scholar

17. Perrin-Sarazin F, Sepehr M, Bouaricha S, Denault J. Potential of ball milling to improve clay dispersion in nanocomposites. Polym Eng Sci. 2009;49:651–65.10.1002/pen.21295Search in Google Scholar

18. Pappalardo S, Russo P, Acierno D, Rabe S, Schartel B. The synergistic effect of organically modified sepiolite in intumescent flame retardant polypropylene. Eur Polym J. 2016;76:196–207.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.01.041Search in Google Scholar

19. Tartaglione G, Tabuani D, Camino G, Moisio M. PP and PBT composites filled with sepiolite: morphology and thermal behaviour. Compos Sci Technol. 2008;68:451–60.10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.06.023Search in Google Scholar

20. Horrocks AR, Kandola BK, Smart G, Zhang S, Hull TR. Polypropylene fibers containing dispersed clays having improved fire performance. I. Effect of nanoclays on processing parameters and fiber properties. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;106:1707–17.10.1002/app.26864Search in Google Scholar

21. Lertwimolnun W, Vergnes B. Influence of compatibilizer and processing conditions on the dispersion of nanoclay in a polypropylene matrix. Polymer 2005;46:3462–71.10.1016/j.polymer.2005.02.018Search in Google Scholar

22. Xia M, Jiang Y, Zhao L, Li F, Xue B, Sun M, Liu D, Zhang X. Wet grinding of montmorillonite and its effect on the properties of mesoporous montmorillonite. Colloid Surface A 2010;356:1–9.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.12.014Search in Google Scholar

23. Schartel B, Hull TR. Development of fire-retarded materials – interpretation of cone calorimeter data. Fire Mater. 2007;31:327–54.10.1002/fam.949Search in Google Scholar

24. Dikmen S, Yilmaz G, Yorukogullari E, Korkmaz E. Zeta potential study of natural- and acid-activated sepiolites in electrolyte solutions. Can J Chem Eng. 2012;90:785–92.10.1002/cjce.20573Search in Google Scholar

25. Laoutid F, Bonnaud L, Alexandre M, Lopez-Cuesta JM, Dubois P. New prospects in flame retardant polymer materials: from fundamentals to nanocomposites. Mater Sci Eng. 2009;63:100–25.10.1016/j.mser.2008.09.002Search in Google Scholar

26. Tang Y, Hu Y, Li B, Liu L, Wang Z, Chen Z, Fan W. Polypropylene/montmorillonite nanocomposites and intumescent, flame-retardant montmorillonite synergism in polypropylene nanocomposites. J. Polym Sci. 2004;42:6163–73.10.1002/pola.20432Search in Google Scholar

27. Brehme S, Köppl T, Schartel B, Altstädt V. Competition in aluminium phosphinate-based halogen-free flame retardancy of poly(butylene terephthalate) and its glass-fibre composites. e-Polymers 2014;14:193–208.10.1515/epoly-2014-0029Search in Google Scholar

28. Qin H, Zhang S, Zhao C, Hu G, Yang M. Flame retardant mechanism of polymer/clay nanocomposites based on polypropylene. Polymer 2005;46:8386–95.10.1016/j.polymer.2005.07.019Search in Google Scholar

29. Hirschler MM. Flame retardants and heat release: review of data on individual polymers. Fire Mater. 2015;39:232–58.10.1002/fam.2242Search in Google Scholar

30. Braun U, Balabanovich AI, Schartel B, Knoll U, Artner J, Ciesielski M, Döring M, Perez R, Sandler JKW, Altstädt V, Hoffmann T, Pospiech D. Influence of the oxidation state of phosphorus on the decomposition and fire behaviour of flame-retarded epoxy resin composites. Polymer 2006;47:8495–508.10.1016/j.polymer.2006.10.022Search in Google Scholar

31. Gilman JW, Kashiwagi T. Nanocomposites: a revolutionary new flame retardant approach. SAMPE J. 1997;33:40–6.Search in Google Scholar

32. Almeras X, Le Bras M, Hornsby P, Bourbigot S, Marosi Gy, Keszei S, Poutch F. Effect of fillers on the fire retardancy of intumescent polypropylene compounds. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2003;82:325–31.10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00187-3Search in Google Scholar

33. Golebiewski J, Galeski A. Thermal stability of nanoclay polypropylene composites by simultaneous DSC and TGA. Compos Sci Technol. 2007;67:3442–7.10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.03.007Search in Google Scholar

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Full length articles

- Ultralight sponges of poly(para-xylylene) by template-assisted chemical vapour deposition

- Cryostructuring of polymer systems. 44. Freeze-dried and then chemically cross-linked wide porous cryostructurates based on serum albumin

- Macroporous polymer beads derived from a novel coporogen of polyethylene/dichlorobenzene

- Gas separation properties of Troeger’s base-bridged polyamides

- Catalytic crosslinking of a regenerated hydrophobic benzylated cellulose and nano TiO2 composite for enhanced oil absorbency

- On orientation memory in high density polyethylene – carbon nanofibers composites

- Comparative investigation of physical, mechanical and thermomechanical characterization of dental composite filled with nanohydroxyapatite and mineral trioxide aggregate

- Dissipative particle dynamics simulation on the self-assembly of linear ABC triblock copolymers under rigid spherical confinements

- Synthesis and characterization of cellulose acetate naphthoate with good ultraviolet and chemical resistance

- Thermal characterization and flammability of polypropylene containing sepiolite-APP combinations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Full length articles

- Ultralight sponges of poly(para-xylylene) by template-assisted chemical vapour deposition

- Cryostructuring of polymer systems. 44. Freeze-dried and then chemically cross-linked wide porous cryostructurates based on serum albumin

- Macroporous polymer beads derived from a novel coporogen of polyethylene/dichlorobenzene

- Gas separation properties of Troeger’s base-bridged polyamides

- Catalytic crosslinking of a regenerated hydrophobic benzylated cellulose and nano TiO2 composite for enhanced oil absorbency

- On orientation memory in high density polyethylene – carbon nanofibers composites

- Comparative investigation of physical, mechanical and thermomechanical characterization of dental composite filled with nanohydroxyapatite and mineral trioxide aggregate

- Dissipative particle dynamics simulation on the self-assembly of linear ABC triblock copolymers under rigid spherical confinements

- Synthesis and characterization of cellulose acetate naphthoate with good ultraviolet and chemical resistance

- Thermal characterization and flammability of polypropylene containing sepiolite-APP combinations