Abstract

In this article, we aim to estimate what the cost of Covid-19 has been in terms of unemployment for Spain. We use a simple autoregressive model to simulate what the unemployment rate would have been without the pandemic and we compare this with the actual values. We also forecast the unemployment rate for 2021 and 2022 to analyse the persistence of the pandemic shock to unemployment.

1 Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic started in China in December 2019, since then it has cost millions of lives and had huge consequences for most of the world’s economies. The unemployment rate has shown significant rises as the pandemic has progressed in countries with traditionally high unemployment rates.

In this article, we aim to quantify the effect of Covid-19 on the unemployment rate for Spain, which is a country that traditionally has high and persistent unemployment rates. Spain is one of the countries alongside Greece and Italy where unemployment rates reached above 20% after the Great Recession started in 2008. To measure the effect of the pandemic, we estimate a simple seasonal autoregressive, integrated and moving average (SARIMA) model until the end of 2019 and use this model to forecast the unemployment rates after that. We compare the values this model gives with the actual rates of unemployment from the beginning of 2020. We also forecast the unemployment rates for 2021 and 2022. The policy insights we aim to gain here have to do with assessing to what extent the already deployed measures have worked and how further fiscal policy easing can help the recovery.

To the best of our knowledge, only Ahmad, Khan, Jiang, Kazmi, and Abbas (2021) have forecast the unemployment rate for Spain since the pandemic started using autoregressive, integrated, and moving average (ARIMA) or hybrid ARIMA models. Bauer and Weber (2021) also forecast how much unemployment was caused by the lockdown in Germany in 2020 using the difference-in-differences method.[1] In contrast to these papers, we estimate the cost of Covid-19 in terms of unemployment by forecasting unemployment using the observed unemployment data for Spain until the last quarter of 2019 as a training set, and the actual values from this date onwards as a testing set.

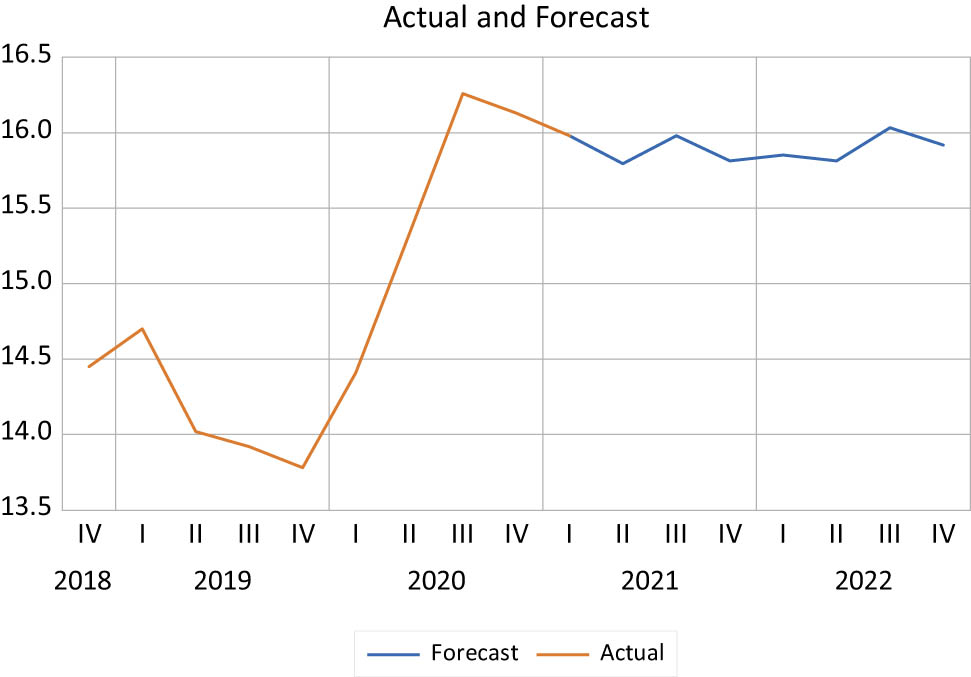

Figure 1 illustrates that the unemployment rate in Spain rose from 13.78% in the last quarter of 2019 to 16.13% 1 year later.

Unemployment rate in Spain. Source: “Instituto Nacional de Estadística” in Spain, https://www.ine.es.

We find that the unemployment rate was 3% higher in mid-2020 than it would have been without the pandemic.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. In the next section, we explain where the data were obtained, the method, and the results, and the last section concludes.

2 Empirical Analysis

The data for this empirical analysis are quarterly observations for the unemployment rate for Spain obtained from the “Instituto Nacional de Estadística” in Spain, https://www.ine.es. The data run from 2002Q2 until 2021Q1 (Figure 1). The data are not seasonally adjusted.

To obtain estimates of the unemployment rate in a scenario without the pandemic, we first estimate a seasonal autoregressive and integrated moving average SARIMA model of order (s, p, d, q), where s is the seasonal pattern of the autoregressive and moving average parts, p is the order of the autoregressive part, d is the order of integration, and q is the order of the moving average part. The models have been estimated with an intercept, with observations until 2019Q4. The order of the SARIMA has been obtained by choosing the model that minimises the Akaike information criterion for a maximum order of (2, 4, 4), and the order of integration I(d) has been chosen using the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS 1992) stationarity test at the 5% significance level for a maximum of I(2). The selected model is a SARIMA (1, 1, 1, 0), with a final model with the following components: constant, autoregressive (AR)(1), seasonal autoregressive (SAR)(4), and moving average (MA)(4). The residuals of the estimated model do not show any signs of remaining seasonality.[2] Figure 2 displays both the forecast values, using dynamic forecasting, and the actual observations.

Unemployment rate forecast in normal times and actual rate.

The difference in 2020Q1 is smaller than 0.5%, but that difference grows over time. In 2020Q3, the difference between the actual and forecast values is about 3.5%. Our results show as a consequence that the pandemic has caused excess unemployment of around 4% in its first year.

Once we have estimated the size of the pandemic shock to unemployment, we next analyse the persistent nature of the shock. Figure 3 plots the forecast unemployment rates from the estimated model until 2021Q1. The estimated model is a SARIMA (1, 1, 1, 1) with a final model with the following components: constant, AR(1), SAR(4), MA(1), and SMA(4). The model has been chosen using the Akaike information criterion, as before.

Unemployment rate forecast in Covid-19 times.

The unemployment rate seems to be stagnant when the observations for 2021 and 2022 are compared. The estimated persistence of the pandemic shock to unemployment is consistent with the previous literature, which concludes that shocks to unemployment in Spain tend to be long-lasting because of the institutional features of the Spanish labour market (see Faria & León-Ledesma, 2008, amongst others). The seminal paper by Blanchard and Summers (1986) argues that hysteresis, or the tendency of unemployment to react with a high degree of persistence to temporary supply and demand shocks, is explained by the bargaining power of strong unions and worker protection schemes.

Our results for persistence depend, however, on using a forecast based on a particular SARIMA model. We also have to bear in mind that to date (November 2021) Spain is one of the countries in the EU with the highest percentage of target people fully vaccinated against the COVID-19. This certainly will have an impact in the evolution of the economy, and hence, the rate of unemployment.[3] We should analyse whether our conclusion about the persistence of the pandemic shock to Spanish unemployment is conditioned on the choice of the SARIMA model. Figure 4 plots the unemployment forecast for all the SARIMA models that are consistent with the data set. The red line corresponds to the model selected using the Akaike information criterion, which is the one plotted in Figure 3. It is apparent that the vast majority of models tend to conclude in favour of persistence in unemployment.

Unemployment forecast under all plausible SARIMA specifications.

3 Conclusion

The article shows that the Covid-19 pandemic has caused a severe increase in unemployment in Spain. Furthermore, this shock appears to have long-lasting effects unless there is an exogenous intervention. It also shows that the economic measures applied so far by the Spanish Government have not been enough to counteract the effects of the shock on the unemployment rate even though the European Commission forecast gross domestic product growth of 6% for Spain for 2021. The Next Generation EU funds[4] could help to reverse the situation, but it may also be that more measures are needed to fight the economic impact of the pandemic. This complements the results found in the study by Cuestas and Ordóñez (2018) who obtained that a government expenditure shock has a negative impact on the unemployment rate.

Higher vaccination rates and the deployment of measures to alleviate the damage cause in many economic sectors will definitely help the reduction in unemployment. This, coupled with further measures to reduce rigidities in this particular labour market, will certainly reduce the pressure created by the pandemic shock.

Acknowledgements

Javier Ordóñez and Mercedes Monfort are grateful for support from the University Jaume I research project UJI-B2020-26. Javier Ordóñez also acknowledges the Generalitat Valenciana PROMETEO/2018/102.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Ahmad, M., Khan, Y. A., Jiang, C., Kazmi, S. J. H., & Abbas, S. Z. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on unemployment rate: An intelligent based unemployment rate prediction in selected countries of Europe. International Journal of Finance & Economics. Forthcoming.10.1002/ijfe.2434Search in Google Scholar

Bauer, A., & Weber, E. (2021). COVID-19: How much unemployment was caused by the shutdown in Germany?. Applied Economics Letters, 28(12), 1053–1058. 10.1080/13504851.2020.1789544.Search in Google Scholar

Blanchard, O. J., & Summers, L. H. (1986). Hysteresis in unemployment (October). NBER working paper No. w2035.10.3386/w2035Search in Google Scholar

Cuestas, J. C., & Ordóñez, J. (2018). Fiscal consolidation in Europe: Has it worked?. Applied Economics Letters, 25(16), 1179–1182.10.1080/13504851.2017.1406650Search in Google Scholar

Faria, J. R., & León-Ledesma, M. A. (2008). A simple nonlinear dynamic model for unemployment: Explaining the Spanish case. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2008, 981952.10.1155/2008/981952Search in Google Scholar

Gil-Alana, L. A., Cunado, J., & Perez de Gracia, F. (2008). Tourism in the Canary Islands: Forecasting using several seasonal time series models. Journal of Forecasting, 27(7), 621–636.10.1002/for.1077Search in Google Scholar

Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P. C. B., Schmidt, P., Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root. Journal of Econometrics, 54(1–3), 159–178. 10.1016/0304-4076(92)90104-Y.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Juan Carlos Cuestas et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Regular Articles

- Houses as Collateral and Household Debt Deleveraging in Korea

- Methods Used in Economic Research: An Empirical Study of Trends and Levels

- Money for the Issuer: Liability or Equity?

- Corruption Accusations and Bureaucratic Performance: Evidence from Pakistan

- Subsidising Formal Childcare Versus Grandmothers' Time: Which Policy is More Effective?

- The Impact of Foreign Direct Investments on Poverty Reduction in the Western Balkans

- New Issues in International Economics

- Structural Breaks and Explosive Behavior in the Long-Run: The Case of Australian Real House Prices, 1870–2020

- Measuring the Cost of Covid-19 in Terms of the Rise in the Unemployment Rate: The Case of Spain

- Digital Gender Divide and Convergence in the European Union Countries

- Disentangling Permanent and Transitory Monetary Shocks with a Nonlinear Taylor Rule

- The Export Strategy and SMEs Employment Resilience During Slump Periods

- Corruption and International Trade: A Re-assessment with Intra-National Flows

- Fiscal Rules in Economic Crisis: The Trade-off Between Consolidation and Recovery, from a European Perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Regular Articles

- Houses as Collateral and Household Debt Deleveraging in Korea

- Methods Used in Economic Research: An Empirical Study of Trends and Levels

- Money for the Issuer: Liability or Equity?

- Corruption Accusations and Bureaucratic Performance: Evidence from Pakistan

- Subsidising Formal Childcare Versus Grandmothers' Time: Which Policy is More Effective?

- The Impact of Foreign Direct Investments on Poverty Reduction in the Western Balkans

- New Issues in International Economics

- Structural Breaks and Explosive Behavior in the Long-Run: The Case of Australian Real House Prices, 1870–2020

- Measuring the Cost of Covid-19 in Terms of the Rise in the Unemployment Rate: The Case of Spain

- Digital Gender Divide and Convergence in the European Union Countries

- Disentangling Permanent and Transitory Monetary Shocks with a Nonlinear Taylor Rule

- The Export Strategy and SMEs Employment Resilience During Slump Periods

- Corruption and International Trade: A Re-assessment with Intra-National Flows

- Fiscal Rules in Economic Crisis: The Trade-off Between Consolidation and Recovery, from a European Perspective