Harmonization of European Insolvency Law: Preventing Insolvency Law from Turning against Creditors by Upholding the Debt–Equity Divide

-

R.J. de Weijs

In essence, insolvency law is collective debt collection law. By means of a collective procedure, insolvency law seeks to ensure that the going concern value is captured for the creditors. Where the shareholders possess the dominant voice outside of insolvency, in insolvency creditors take over this position and become the economic owners of the company. In three different settings shareholders can interfere with the insolvency process and try to capture all the value in the company or at least leave the creditors with the liquidation value and usurp the going concern surplus. These three settings are (i) shareholders as secured lenders, (ii) shareholders as acquirers out of pre-packs or other asset sales and (iii) shareholders under composition plans. The proposed EU Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance (November 2016) contains measures in the field of composition plans as part of a preventive restructuring. The proposed directive addresses the potential problem that shareholders would usurp the going concern surplus by introducing the Absolute Priority Rule. The proposed directive should be considered a first step in the right direction. It should, however, be realized that the protection offered in the proposed directive could easily be circumvented by a shareholder financing not with capital but with secured shareholder loans. Also, if pre-pack sales or other sale processes do not limit interference by shareholders, shareholders will prefer the route of an asset sale above a restructuring.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, insolvency law has moved from the margins of European legislative activity to the center. Although the European Insolvency Regulation (2012) and its Recast (2017) only deal with questions of private international law, it has been instrumental in creating a clearly identifiable field of European Insolvency Law.[1] The Commission now identifies a well-functioning insolvency law as an essential part of a good business environment and considers a higher degree of European harmonization essential for a well-functioning single market.[2] In November 2016[3] the Commission presented its proposal for a Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance thereby seeking to actually harmonize substantive insolvency law at a European level.

The proposed directive deals with only a part of corporate insolvency law, namely the possibilities of restructuring a company in order to prevent a company from entering full insolvency proceedings, hence the directive’s title of ‘Preventive Restructuring Framework’.[4] The most important protective measure in the proposed directive is the introduction of a so-called Absolute Priority Rule as part of a preventive restructurings. The Absolute Priority Rule protects creditors in case of insolvency against shareholders. Without such a rule, shareholders can divert the flow of value away from creditors to themselves. Such a rule is, therefore, necessary to prevent shareholders to use insolvency procedures to further their own interests at the expense of creditors.

The problem of shareholders trying to gain the upper hand also in case of insolvency is very persistent. However, insolvency law does not exists to serve the interest of shareholders. Its purpose is to serve the interest of creditors, such as lenders, suppliers and tax authorities in the event their common debtor is no longer able to pay all of its debt. Whereas shareholders possess the dominant voice inside a solvent company, creditors are to assume this position in the event of insolvency. This classic paradigm is being eroded at different national levels by means of more aggressive and more experienced shareholders. Insolvency law thereby – completely at odds with its basic reason for existence – increasingly no longer works for creditors but against them.

The ramifications of insolvency law turning into its own mirror image go well beyond poorly functioning companies that lost out in the survival of fittest of the market economy. Insolvency law has effect on all contracts with a debtor and a creditor, even outside the immediate prospect of insolvency. If insolvency law is allowed to develop in such a way that it is no longer working for, but rather against creditors, also the basic fabric of our market economy and our society changes. As will be explained, capitalism is at risk of turning into debtism.

The central theme of this article is the battle for value in financially distressed firms between shareholders and creditors. Three settings in insolvency procedures will be analyzed in which shareholders can try to gain the upper hand.

The role of shareholders as creditors rather than as capital providers (§ 4).

The role of shareholders as acquirers out of pre-packs or other asset sales (§ 5).

The role of shareholders under reorganization plans, including preventive restructurings (§ 6).

An analysis will be made whether or not different national systems provide rules against shareholders gaining control of the insolvency process. The focus will be on German, English and Dutch law with comparisons with US law. This article does not provide a full and detailed discussion of the envisioned working of the proposal for the Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance, but will discuss its most important protective measures to prevent shareholders to be able to use preventive restructurings to further their own interests at the expense of creditors (§ 6.2). The article should be read with large companies and professional shareholders in mind. As to Small and Medium Enterprises (SME’s), the dynamics can be different and may justify different, more relaxed rules (§ 6.1).

Before explaining the proper goals of insolvency law as identified by Insolvency Law Theory in § 3 and the three identified clashes between shareholders and creditors in § 4, 5 and 6, an analysis will be provided of incentives by companies and their shareholders to use leveraged finance, i. e., financing a company with debt rather than capital (§ 2). In this part also the Late Payment Directive[5] and the Directive Against Tax Avoidance[6] will be discussed, since these are part of the overall attempts by the European Union to reduce leverage. This analysis of leveraged finance is given not only to better understand why it is attractive to finance with debt and why companies can therefore be prone to move dangerously close to insolvency, but also to understand the background of trade creditors in insolvency proceedings. The ways shareholders can try to gain the upper hand in insolvency, as well as the attempts by the European Union to reduce leverage, can only really be understood by thinking in terms of corporate finance and balance sheets. Therefore, this article illustrates the arguments with balance sheets to flesh out the battle for value in insolvency procedures.

2. Leveraged finance and the late payment directive and the tax avoidance directive

Insolvency law deals with the situation in which a debtor cannot pay its debts in full. In order to understand why companies might take on more debt than they can eventually pay, one needs to understand the basics of corporate finance and the dynamics of leveraged finance.[7]

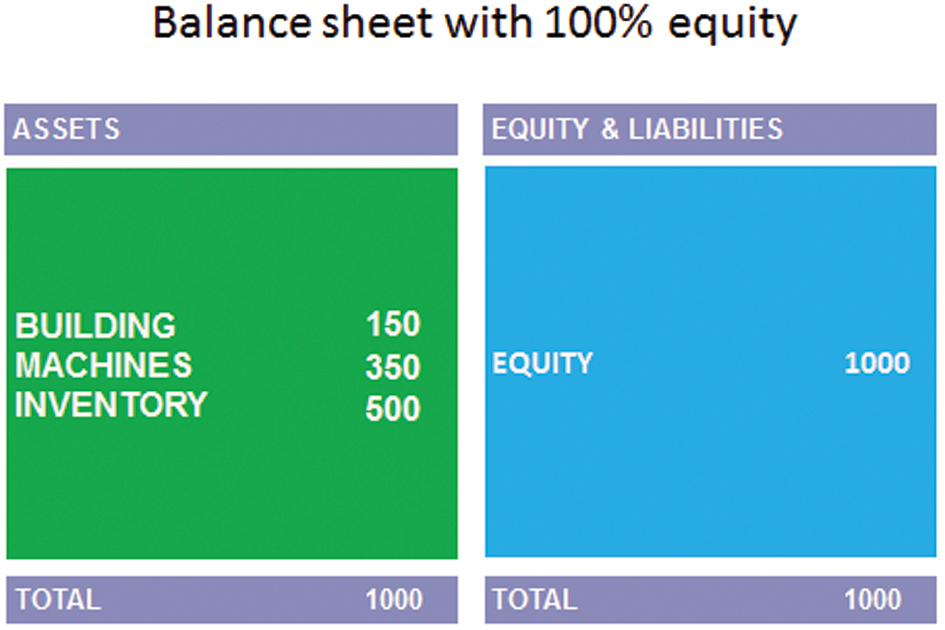

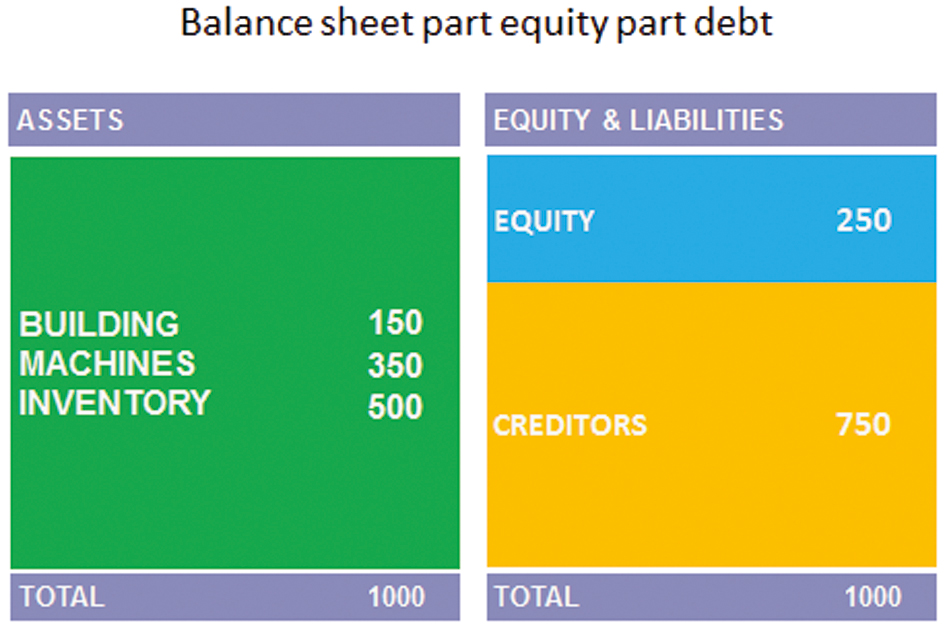

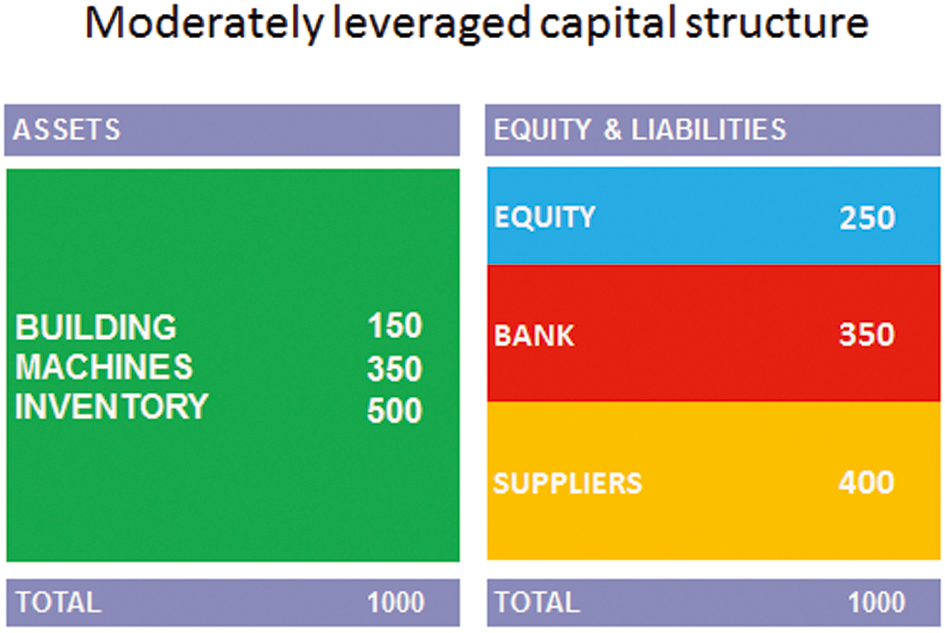

The basics of corporate finance can best be explained using a balance sheet. A company has assets. These are listed on the left side of the balance sheet. In the case at hand the total value of assets is €1000. The assets are real estate, machines and inventory. The company must have acquired these assets. The right side of the balance sheet explains and depicts how these assets have been financed. In the initial case presented here, the company has been financed entirely with shareholder’s money provided as equity, also referred to as capital.[8]

Although one intuitively likes to stay well away from a situation of insolvency and one might not want to incur too much debt, there is a global tendency for companies to do just that: take on as much debt as possible. One of the reasons for doing so, is that the shareholders can increase their returns (Return on Equity or ROE) by having the company taking on debt. This is referred to as leveraged finance. In case of leveraged finance, the company is being financed with little shareholder money and significant money from creditors; debt. The more debt the company takes on, the higher the leverage of that company.

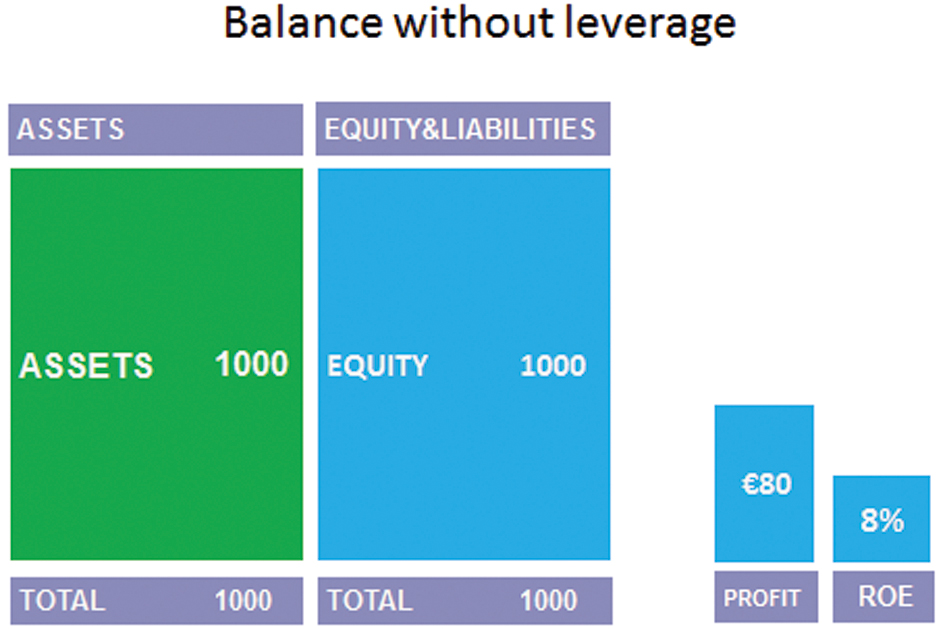

The easiest way to understand leverage finance, is to see its effects by using an example. The company with a balance sheet total of €1000 is initially financed solely by shareholder’s money and therefore financed 100% by equity. Now assume that the company has made a profit of €80. In order to establish whether €80 is a lot or not, one needs to take into account how much money the shareholder has put into the company in order to earn said €80. In the case at hand, the shareholder invested €1000. The return on equity (ROE) is therefore 8%. On each euro invested, the shareholder has made 8 cents.

Leverage finance is a way to increase returns for shareholders. Not by cutting costs or by attracting more customers, but by increasing the leverage of the company. The profit in all subsequent examples will remain at a set level of €80.

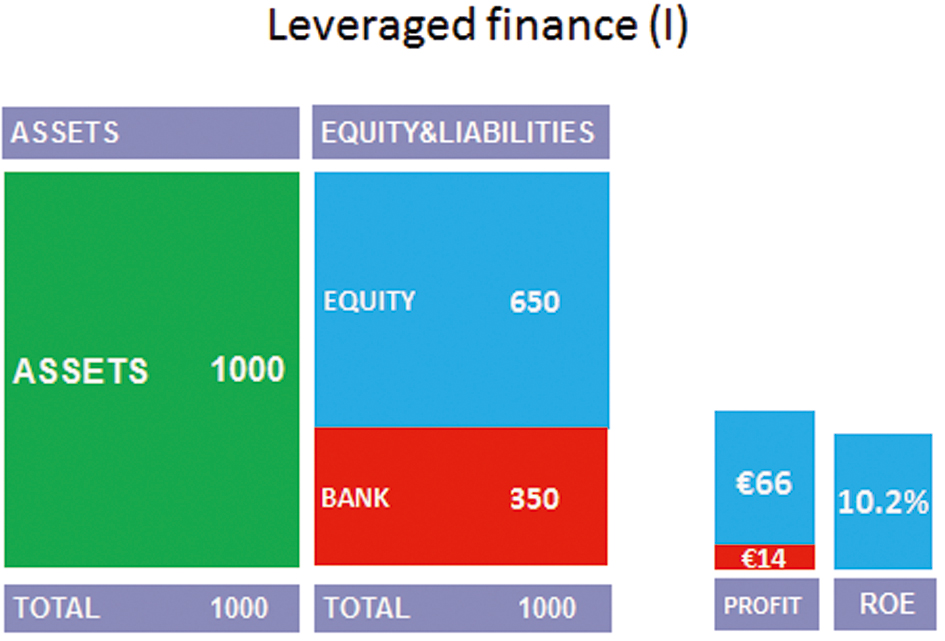

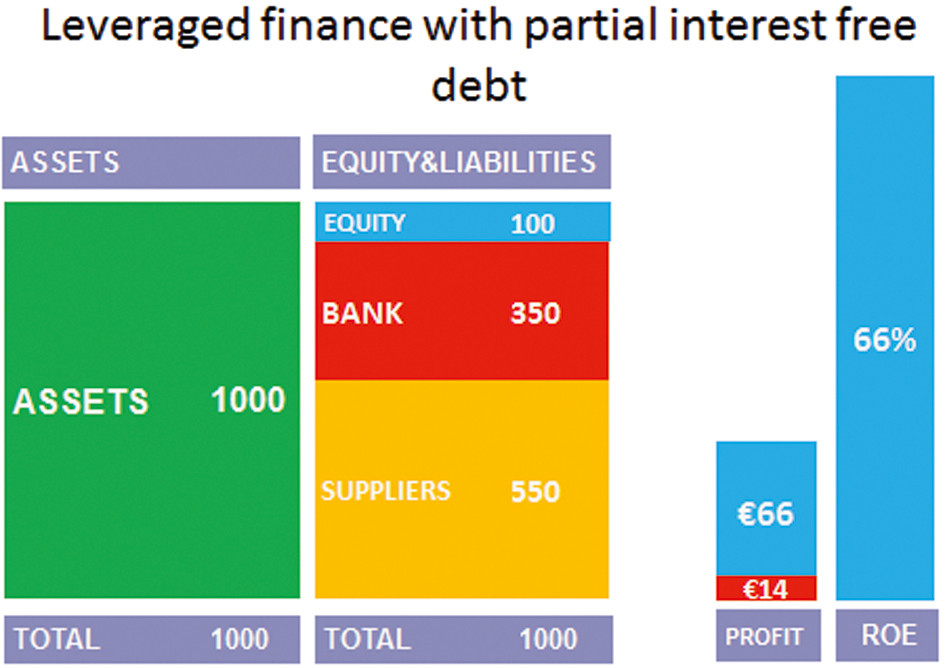

What if the company is no longer financed solely by equity, but has also taken on debt? What if the company has borrowed €350 from a bank? On the right side of the balance sheet, the debt to the bank appears as a liability. The company is now no longer solely financed by shareholders but also by creditors. The company will now have to start paying interest to the bank of, e. g., 4% annually. Therefore it will have to pay €14 to the bank. Of the €80 in profit, €14 needs to be paid to the bank. The remaining profit for the shareholder is reduced to €66. The shareholder has, however, invested less himself. Now he has only invested €650. This means that with an investment of €650, the shareholder has now made €66. This equals a return on equity of 10.2%. So one can already see a mild increase of the ROE from 8% to 10.2%.

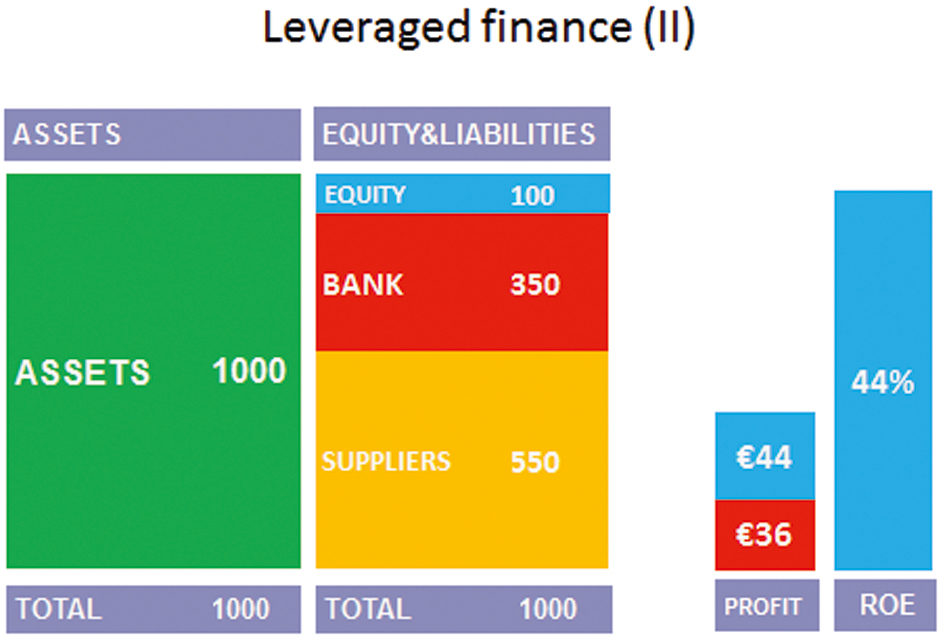

The same dynamics present themselves if the company takes on more debt and thereby increases its leverage. Another source of financing by means of debt, is attracting financing from suppliers. A yet unpaid supplier also is a creditor of the company. Typically a company is financed by equity and different type of creditors. In the case at hand, there could be outstanding invoices from suppliers for a total of €550. If one continues to replace shareholder equity as a source of finance by debt, the same pattern keeps repeating itself, leading to an increase in Return on Equity. At the level of €900 in total amount of outstanding debt, the ROE increases to 44%.[9]

The increased Return on Equity is one of the great attractions of leveraged finance. In reality, the increase in ROE as a result from increased leverage is even stronger because of two additional factors.

The first circumstance is the effect of the tax shield. The tax shield is a result from the general rule that interest payments are seen as a cost which is tax-deductible, whereas dividend payments are not tax-deductible.[10] The problem of taxation providing a further incentive to finance by means of debt instead of equity, is also on the European legislative agenda. In the Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union, the problem is identified as follows:

Differences in the tax treatment of various financial instruments may impede efficient capital market financing. The preferential tax treatment of debt, resulting from the deductibility of interest rate payments, is at the expense of other financial instruments, in particular equity. Addressing this tax bias would encourage more equity investments and create a stronger equity base in companies. Also, there are obvious benefits in terms of financial stability, as companies with a stronger capital base would be less vulnerable to shocks. This is particularly true for banks.[11]

This tax benefit is now being reduced by the new European tax measures adopted in the Directive Laying Down Rules Against Tax Avoidance,[12] to be effective as of January 2019. One of the core provisions of the directive is § 4, which provides that interest is only tax deductible up till 30 percent of the taxpayer’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). The new measure therefore by no means results in an equal tax treatment of debt and capital finance, thereby leaving in place the fact that tax measures amplify the incentives already there to finance by means of debt rather than capital.

The second factor further increasing the Return on Equity by means of leveraged finance is the phenomenon of ‘non-interest bearing debt’. Financing a company intentionally with non-interest bearing debt is a standard private equity strategy. A example can be found in the case of Douwe Egberts, the coffee and tea company. After Douwe Egberts had been acquired by a private equity fund, it extended its payments to its suppliers from 60 to 200 days.[13] Since an important part of the balance sheet has been financed by non-interest bearing debt, the Return on Equity increases even further. Thus far in the examples given, it has been assumed that all creditors were entitled to an interest of 4% annually. If suppliers and other creditors have financed the larger part of the balance sheet and if they do not receive any interest, the ROE increases significantly. If the last balance sheet is taken and the suppliers would not receive interest on their outstanding claims, the ROE would increase further from the previous 44% to 66%.[14] This is due to the fact that no longer 4% interest needs to be paid over €900 (being €36 in interest), but now only over €350 (i.e., €14 in interest).

Here also European rules are already in place embodied in Directive on Combating Late Payment in Commercial Transactions.[15] This directive seeks to limit companies to intentionally finance their company by demanding de facto financing from their suppliers. The basic rule is that Member States should ensure that in commercial transactions payments should be made within 60 days. The same dynamics which allow strong parties to force their suppliers to accept longer terms in the first place, are also likely to prevent individual suppliers from bringing cases to courts.[16]

The increasing ROE in case of leveraged finance is the great attraction of financing with debt instead of equity. Leveraged finance is, however, also dangerous, most notably for creditors. Firstly, the entire leveraged structure depends on low interest rates charged by the professional creditors, mostly banks. If interest rates increase, the company quickly succumbs under increased interest payments. Secondly, the leveraged company is left with extremely little equity. Equity also performs the function of a so called equity cushion. Any losses incurred by the company, are first absorbed by equity. Equity is therefore an important measure of financial resilience. Extreme leverage should therefore be seen as undermining the immune system of the company. In case of overleveraged structures, even a minor setback can render the company insolvent.

3. Insolvency law’s proper role and the debt-equity divide

Insolvency law is debt-collection law and more precisely, collective debt collection law. A company is balance sheet insolvent if its assets are worth less than the outstanding debts, meaning there are not sufficient assets to pay all creditors in full. Outside of insolvency, in case a debtor defaults, a creditor can go to court and foreclose on the debtor’s assets. In case of insolvency there are not sufficient assets to pay all creditors in full. The individual approach of debt collection then becomes counterproductive. An individual creditor will try to seize individual assets, thereby possibly dismantling a viable business. As a result of individual foreclosure, the total value available for the creditors is diminished. Or in the words of Jackson:

To the extent that a non-piecemeal collective process (whether in the form a liquidation or reorganization) is likely to increase the aggregate value of the pool of assets, its substitution for individual remedies would be advantageous to the creditors as a group. This is derived from the commonplace notion: that a collection of assets is sometimes more valuable than the same assets would be if spread to the winds. It is often referred to as the surplus of a going-concern value over a liquidation value.[17]

Insolvency law is commonly justified by the notion that an insolvency procedure is beneficial for all creditors together, since it first of all enhances the total value that can be distributed to creditors. The collective procedure of debt collection also reduces costs of creditors that would otherwise arise if creditors would be litigating against each other over the limited assets. The dominant insolvency law theory, the Creditors’ Bargain Theory developed in the 1980’s in the USA, goes even one step further and seeks to enhance the normative force of insolvency law by arguing that lacking insolvency laws, creditors would ex ante agree amongst themselves upon rules of collective debt collection.

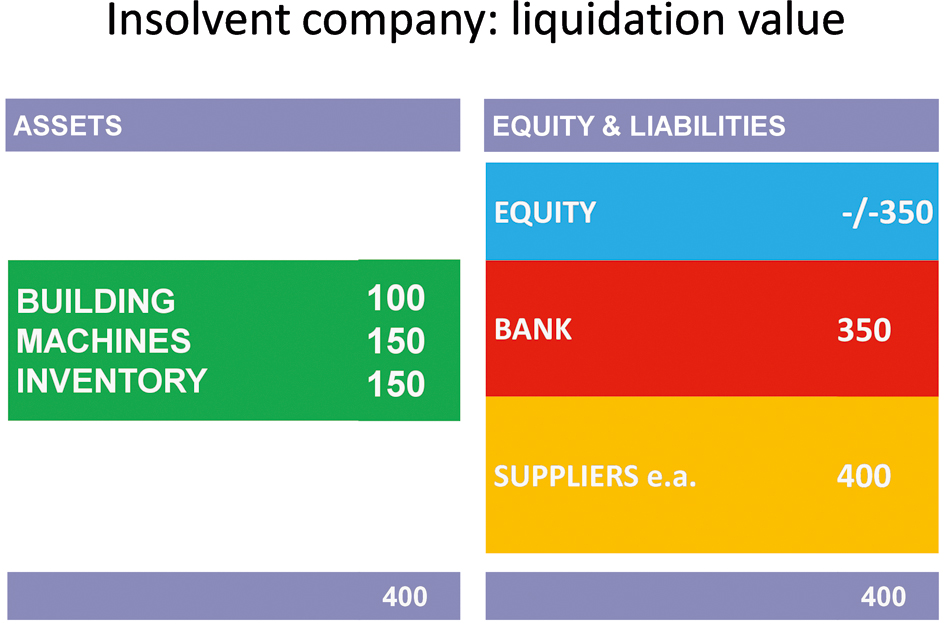

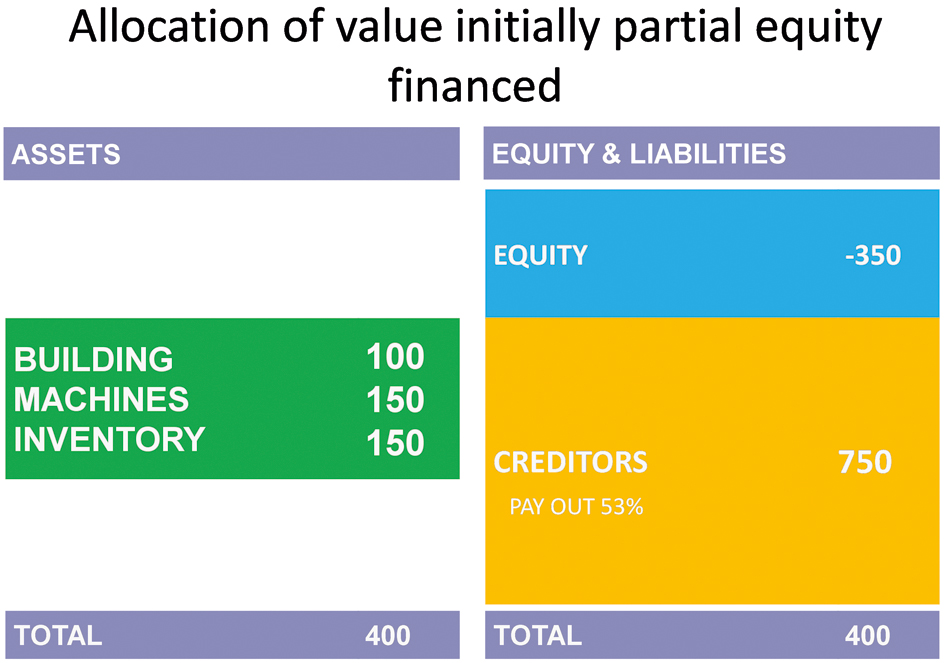

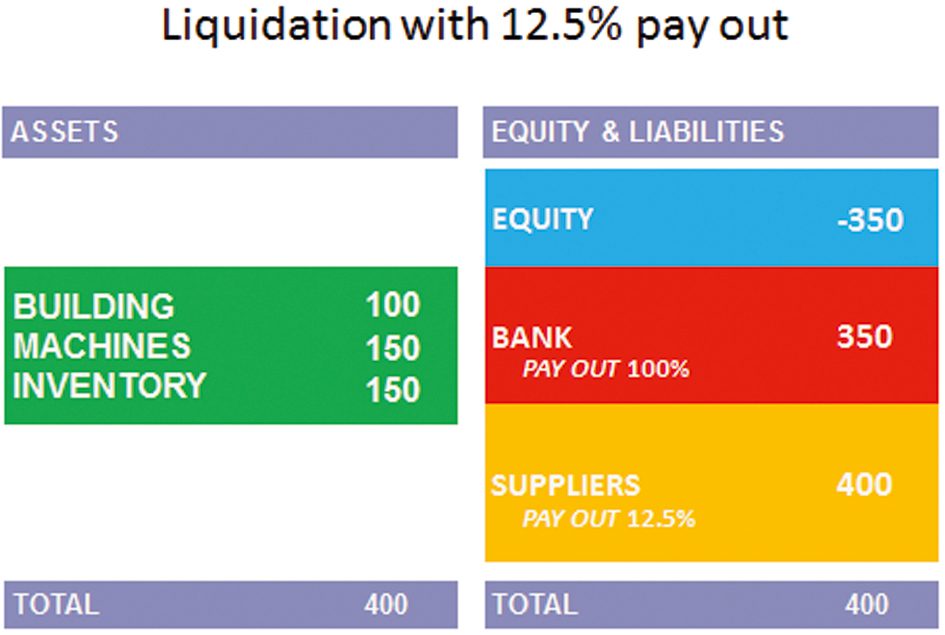

In order to understand both how insolvency law functions and what it goals are, a balance sheet can be utilized. Assume the following balance sheet of an operating launderette, with €750 as outstanding debt and limited assets with a liquidation value of €400. The first step is to see that equity has become negative. Only by calculating negative equity, can the basic rule that the balance sheet is always even on both sides be abided by. Here equity becomes minus €350. The second element is that the assets are no longer there for the shareholders, but for the creditors. Assuming that the bank debt is secured by security rights over the assets, this can be depicted as the bank being entitled to full payment first, followed by unsecured creditors, by placing the assets now at the level of the creditors.

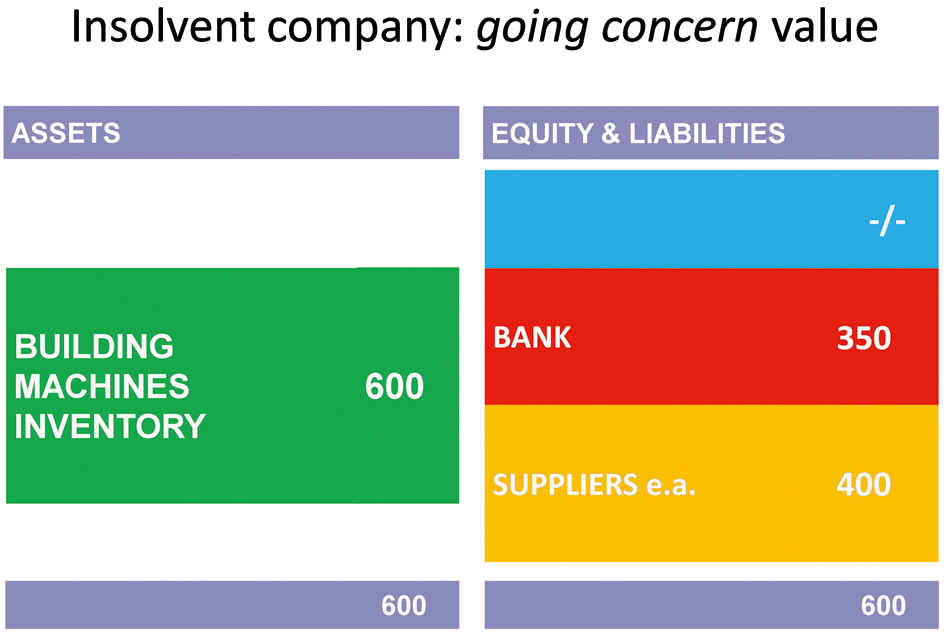

An operating launderette will be worth more than the individual washing machines. The liquidation value might be €400, but the going concern value might be €600. A trustee in bankruptcy will, upon appointment, and if reorganization of the company does not seem to be possible, first try to sell the enterprise going concern. The goal is to capture the going concern value for the creditors.

Insolvency law is thus creditor law. Shareholders of an insolvent company are last in line, also summarized as ‘equity is wiped out first’. This is not unfair, but the result of shareholders investing to get the upside of the company. Shareholders provide capital, also referred to as equity. In return for the provision of equity, shareholders receive shares and are thereby entitled to the potential profits of a company. Creditors provide loans or accept delayed payment, which in turn leads to debt. Creditors are thus entitled to a fixed return in the form of interest (if any). In case of insolvency, the creditors are to be paid before the shareholders receive anything.

This basic corporate finance division between debt and equity is not just descriptive. The presumption that shareholders provide risk-bearing capital forms the foundation of the corporate form with limited liability.[18] Shareholders are entitled to the profits because they are deemed to be the ones that invest risk-bearing capital. Because of the rules of limited liability, shareholders can however also not lose more than they actually put into the company. In case of insolvency, the primacy of shareholders is replaced by that of creditors. Jackson also presents insolvency law as a kind of expropriation of shareholders for the benefit of creditors: “In bankruptcy the unsecured creditors of an insolvent debtor can be viewed as the new equity owners of the debtor and hence entitled to what the debtor was entitled to outside of bankruptcy.”[19] See similarly Armour, Hertig and Kanda: “If the firm defaults on payment obligations, its creditors become entitled to seize and sell its assets. At this point, the creditors change roles: they become, in a meaningful sense, the owners of the firm’s assets.”[20]

In the three different settings identified and elaborated upon below, the shareholders can try to prevent the creditors from actually becoming the new equity owners and receiving the full going concern surplus. To the extent the creditors are not professional creditors but rather suppliers that have subtly been forced into the capital structure of the company in order to increase the leverage of the company, this is all the more problematic.

4. Shareholders as (secured) creditors

Although the underlying assumption of corporate law is that shareholders provide risk bearing capital, the question arises why a shareholder would still do so. In case the shareholder finances by means of equity, he risks losing this all in case of insolvency in accordance with the maxim: ‘equity is wiped out first’. From the perspective of a shareholder, it would be attractive to structure its investment not as capital, but as debt. The shareholder then has two hats, one as creditor and one as shareholder.

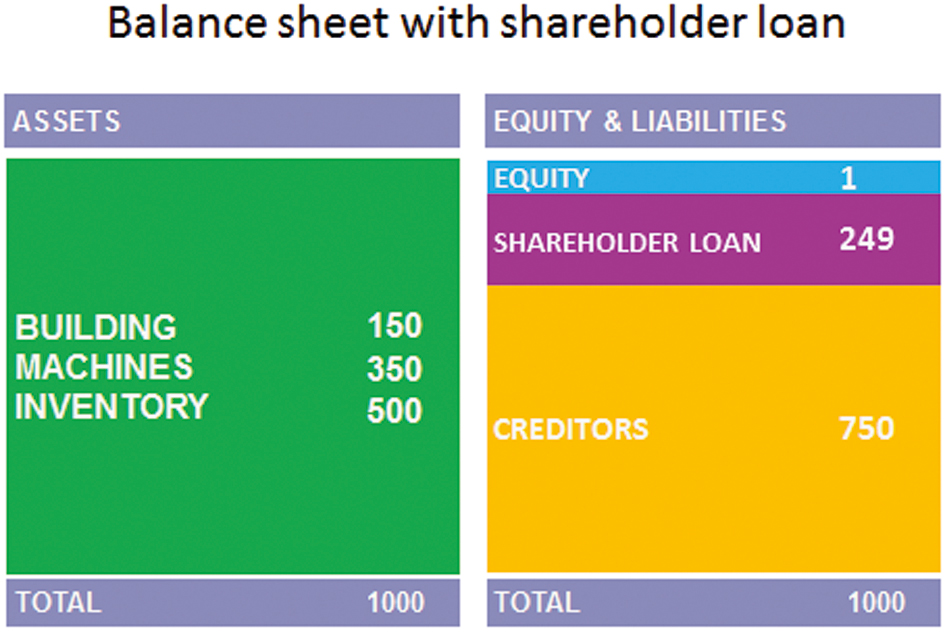

The balance sheet of a company depicts the assets a company has and how these assets have been financed. In the case below, the company has assets worth €1000, financed by €250 in equity and €750 in debt.

If things turn out badly and the value of assets is adjusted downwards, the remaining value will be allocated to the creditors in case of an insolvency procedure. In the current example, this leads to the following. In case the assets are worth only €400 and the outstanding debts amount to €750, all creditors would receive 53% on their claim, foregoing liquidation costs. The shareholder would not receive anything.

A shareholder would be well advised if he were to provide the same investment of €250, to provide it not as an equity contribution, but as a loan.

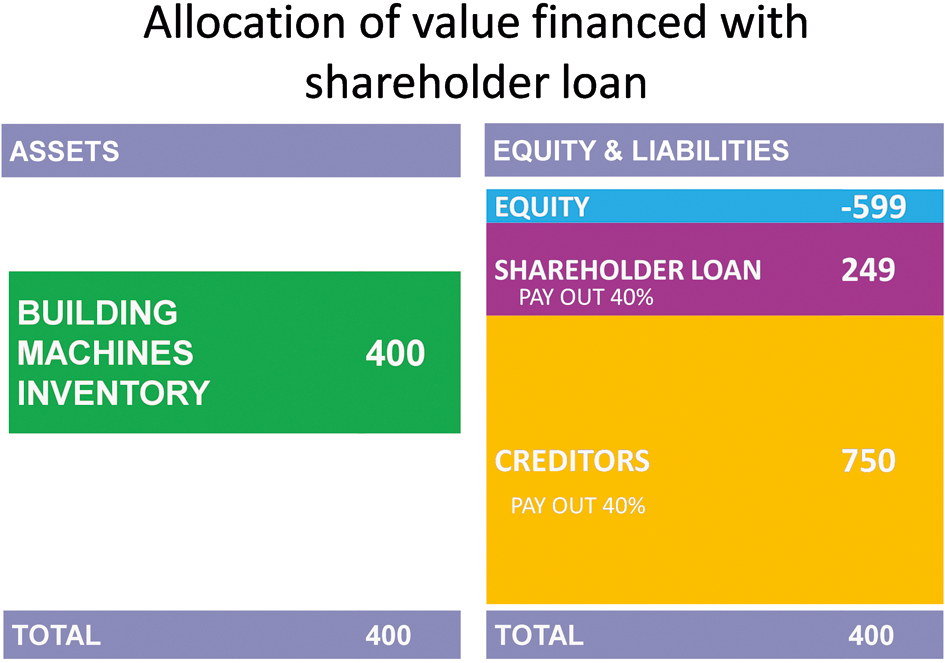

The sole shareholder would then only pay €1 as a capital contribution and lend the remaining €249. Due to the €1 capital contribution for which the shareholder received all the shares in the company, the shareholder is still 100% owner and is thereby entitled to all shareholder rights and also receives the full upside in case of success. If the company is financed by means of shareholder loans, the benefit for the shareholder is that in case of a downside scenario, the shareholder could still present itself as a creditor and demand a share in the remaining assets. The payout to creditors would then no longer be 53% as previously depicted. The pay out to creditors would drop to 40%. At the same time, the investment of the shareholder would not be wiped out entirely, since the shareholder would still get back 40% of his investment of €249.

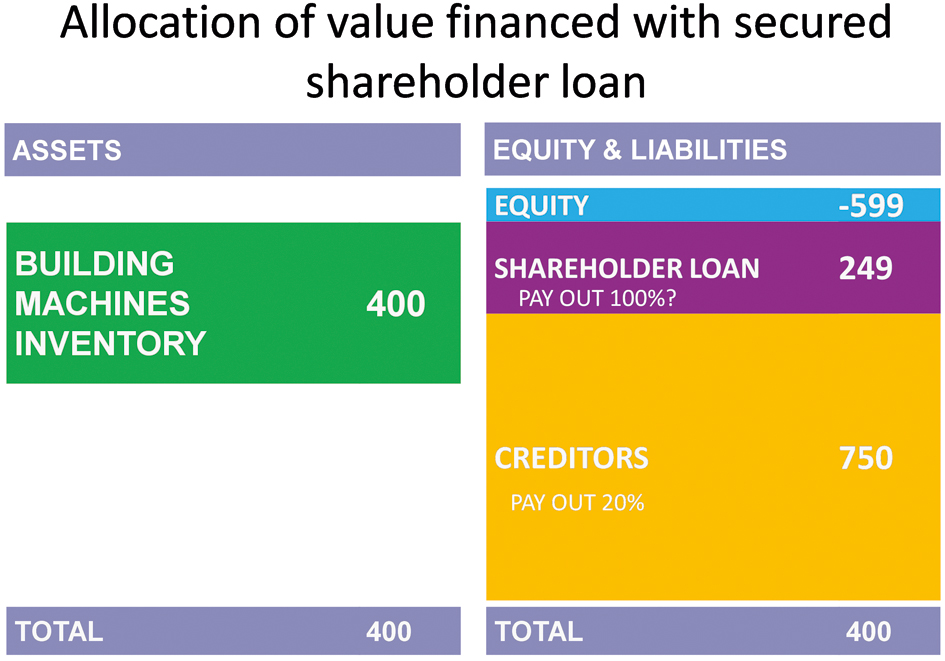

The big drawback of a being a normal creditor is that one still stands to lose a significant part of ones claim in case of insolvency. The even better advised shareholder would therefore finance not by means of a normal shareholder loan, but by means of a secured shareholder loan. The shareholder would then have a right of pledge or a floating charge on the machines and inventory and a right of mortgage on the real estate.

This would lead to the following outcome in the event of failure. In case of insolvency the shareholder could invoke its security rights and thereby receive back in full its investment, ahead of other creditors. The unsecured normal creditors would only receive 20%.

The question is whether this way of financing is allowed. Is the shareholder at liberty to decide for himself the form and shape of his investment? Different Member States provide different rules. Germany[21] and Spain[22] have the strictest rules whereby all shareholder loans are basically subordinated and security rights for shareholder loans are not enforceable. This means that payment on these loans will only be made after outside creditors have been paid in full. Prior to 2009, German law only provided for the subordination of those shareholder loans that would not have been granted by outside creditors. Although the German legislative history is not explicit on why the system has been replaced by simply subordinating all shareholder loans, save for reducing its complexities, Verse does understand there to be a change in underlying policy as well. Verse writes:

It follows that a new rationale is required to explain and legitimize the new rules. Such an explanation is, however, not easy to find. The most plausible explanation that has been offered so far is that subordination of all shareholder loans will simply ensure that the shareholders adequately participate in the entrepreneurial risk of the company.[23]

Austria also provides for subordination, but, in a similar fashion to the old pre-2009 German law, seeks to limit the effects to those shareholder loans that would not have been granted by an outside arm’s length creditor.[24] The Austrian rules only subordinate loans provided by a shareholder at a moment of crisis. The company is assumed to be financially distressed if it is either balance sheet insolvent or unable to pay its debts as they became due. The company is presumed to be financially distressed, if its solvency ratio falls below 8%. Also the US has a well-developed framework to address shareholder loans under the rules of equitable subordination, where subordination is not automatic as is the case in Spain and Germany, but turns on the question as whether the shareholder acted inequitable, where undercapitalization plays an important role.[25]

In the Netherlands, rules are lacking in this respect. In a few cases lower courts have taken the step to actually subordinate shareholder loans, but at the same time other courts a dismissive of such an approach. In ever more big cases, shareholders are seizing the opportunity offered and present themselves as the largest and also secured creditor.[26] England also still has no rules in place.[27] During the overhaul of its insolvency act in the 1980’s however, this was already identified as a clear shortcoming. The Cork committee responsible for the blue print of the current Insolvency Act advised the following on the issue:

The strength of the case of those who seek a change in the law – and a radical at that – can be seen if a simple and perhaps extreme example is taken. A wholly-owned subsidiary company is under-capitalised. It relies virtually wholly on moneys lent by the parent. Its affairs are conducted by and in the interest of the parent and they are mismanaged. There is a history of transactions between subsidiary and parent which, although not individually or collectively susceptible to attack at law, have, cumulatively, advantaged the parent and disadvantaged the subsidiary. All profits earned by the subsidiary have been paid up to the parent by way of dividend and the moneys needed by the subsidiary to conduct its business lent back by the parent. The subsidiary, at the instance of the parent, has obtained substantial credit by relying on its membership of the group of companies headed by the parent. The subsidiary indicates its membership on all documents and billings by showing a device or logo distinctive of the group. The subsidiary becomes insolvent and goes into liquidation. The parent company declines all liability for its subsidiary’s debt to external creditors, and competes with them by submitting a proof in respect of its loan. The result is that, out of the total funds realised by the liquidator for distribution among the creditors, a substantial proportion goes to the parent company. We recognise that a law which permits such an outcome is undoubtedly a defective law.[28]

Thus, the European landscape is divided into countries that do and those that do not have rules addressing the double-hat problem of shareholders being both the equity provider and also a creditor.[29] Currently, the European Union is moving from dealing with matters of private international law to actually harmonizing substantive insolvency law. The issue of ranking of claims was also on the table in preparing the current Proposal for Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance.[30] The issue of ranking of claims or more specific the ranking of shareholder loans is however not addressed in the directive.

The question whether shareholders are allowed to obtain a share as a normal unsecured creditor is often the most decisive as to the pay out to normal creditors in a given case. In case the company is not financed by capital, but by means of shareholder loans, these shareholder loans regularly make up more than 50% of the outstanding debt. This is the case in all jurisdictions where the question arises, whether rules on subordination are[31] in force or are not.[32] Of course the impact on the payout percentage is much stronger if shareholders can also invoke security rights for their claims.

Why should there be limits to the liberty of shareholders to decide for themselves how to structure their investment? Here, three groups of arguments are presented.

The first group of arguments in favor of subordinating shareholder loans relates to core characteristics of what a shareholder is and is not. Allowing the double position of shareholder and creditor undermines the basis of corporate law. A shareholder decides on the course of the company and is entitled to the profits because he provides risk-bearing capital and is thereby residual claim holder.[33] If the shareholder does not incur a larger risk than the creditors or does not even incur a risk because of its fully secured position, no justification remains for the ultimate power residing with the shareholders. In this light, it can simply be deemed unfair to allow shareholders to rank above creditors for their shareholder loans. The shareholder makes an investment with a view of capitalizing on the upward potential of the company. A shareholder should not be first in line in case of failure.

A resulting inconsistency of allowing shareholder loans, most notably secured loans, is that the principle that shareholders cannot ensure a fixed return is infringed upon.[34] If a shareholder makes its investment in the form of a secured shareholder loan against an interest rate of 8%, the shareholder would have a guaranteed minimum return of 8% annually. A guaranteed minimum return of 8% is something that should be too good to be true.

As a follow up to these inconsistencies, an argument against subordination can also be rebutted. An argument against subordination that is often provided is that shareholders should be allowed to rank as any other creditor since, in the end they provided the money. The mistaken background of this argument is that there is only one type of money and that money lent is just money lent. This argument against subordination was also put forth in the US in 1975 against implementing German-like rules providing for automatic subordination, instead of the more idiosyncratic rules of equitable subordination in § 510 of the US Bankruptcy Code. It was argued that shareholders’ money is ‘as green as other people’s money’.[35] Money is however not just money, especially not when it is placed in the capital structure of a company. In case a creditor finances by means of a secured loan of €250,000 with security rights on underlying assets against an interest rate of 8%, this 8% constitutes the maximum return on its investment. In case a shareholder provides the same loan, but then for €250,000 combined with a capital contribution of €1 by which he obtains all the shares in the company, the 8% will be the minimum return on investment. Only by taking into account the entire position of the shareholder, can one understand the investment made and the related incentives.

A second group of arguments relates to undesirable behavior being stimulated by allowing shareholder loans. Allowing secured shareholder loans distorts the investment decisions by the company acting in the interests of the shareholder. Being an entrepreneur means taking risks and identifying opportunities. If someone, however, is in a position where he can make a profit out of an uncertain event but he does not stand to risk to lose anything, this person will be biased to assess the chances of success too high. If the company is balance sheet insolvent, this means that from a balance sheet perspective equity is already wiped out. If the company continues to operate with additional secured shareholder loans, the upside is for the shareholders while the downside is for the ordinary creditors. The phenomenon of gambling for resurrection is a well-known problem in corporate law.[36] This problem is exacerbated too extremes if shareholders are allowed to finance by means of secured loans.[37] If the shareholder is really fully secured, he can make an investment from which he can only profit and as to which the downside is fully borne by other parties. This raises the questions whether one could therefore say that allowing financing by means of secured shareholder loans would result in some kind of casino capitalism? The answer is a firm ‘no’. At the casino, one does not receive back one’s money after making a wrong bet. In the case of secured shareholder loans, one does. Possibly even increased with a minimum fixed return of say 8%.

Related to this second group of arguments in favor of subordination, is one of the strongest and most serious critiques as to subordination rules. Subordination increases the downside for shareholders in case a rescue attempt fails. Subordination might therefore discourage certain investments by shareholders, from which – if successful – also creditors and employees benefit.[38] There is indeed an undeniable cooling effect on the shareholder’s incentive to finance rescue attempts in case their loans are subordinated compared to non-subordination. This effect first has to be balanced by the other extreme that shareholders would be allowed to finance rescue attempts under which the risks are fully borne by outside creditors. In either case, the upside is for the shareholders. Secondly, it has to be borne in mind that not all rescue attempts are necessarily desirable. If, however, the rescue attempt has a more than a 50% chance of success, the upside potential will be the driver for decision-making and the question whether the shareholder will be allowed to share in a downside scenario will be of limited importance for the shareholder faced with the investment decision.[39]

A third group of arguments relate to the overall framework of insolvency law. Part of any well-functioning insolvency law are rules on transaction avoidance and dividend payment which rules limit the freedom of the debtor-company to conduct transactions prior to the opening of an insolvency procedure. Statutes across Europe and also across the world are typically especially concerned with payments to related parties, most notably to shareholders immediately prior to the opening of an insolvency procedure.[40] If shareholders are allowed to finance by means of secured loans, these founding rules become moot and senseless. The shareholder loses all incentives to have dividend or intercompany claims paid prior to insolvency. Anything that is in the company can be encumbered by security rights and would then go to the shareholders anyway. This outcome also reduces the normative force of transaction avoidance rules in relation to outside parties to well below zero. Money actually paid to third parties could be reclaimed from third parties on the basis of transaction avoidance, and would benefit in the end the shareholder for payments on its large loans. Transaction avoidance would then become an instrument to reclaim money from creditors for the benefit of shareholders in insolvency.

Lacking rules, shareholders will finance their companies not with capital but with loans. The result is that the ultimate power in a company no longer resides with those having provided risk bearing capital, but with those that provided risk evasive loans (debt). Insolvency law not only turns against normal creditors, but also ultimately ends up as its own mirror image. The same would happen to capitalism as such. Capitalism will turn into a much more grim debtism.[41]

Shareholder loans should be subordinated, at least to the extent that a third party would not have granted such a loan. The current proposal for the Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance with first steps to actual harmonization of substantive insolvency law does not address the issue, although ranking was a topic on the table. The Austrian rules could serve as an example for future minimum harmonization. Namely that shareholders loans granted when solvency is below 8% are presumed to qualify as a shareholder loan that a third party would not have granted. Such shareholder loans should be subordinated and security rights for such loans should not be enforceable.

5. Shareholders as buyers out of pre-packs or other asset sales

The second setting in which insolvency law is turning against creditors is the setting of pre-pack sales or other type of asset sales to related parties, most notably shareholders.

In Europe, the use of pre-packs is currently largely limited to the UK, France, the Netherlands and to a certain extent Greece, Ireland and Slovenia.[42] A pre-pack is foremost a sale prepared prior to the actual opening of the insolvency procedure. Already prior to the actual opening of an insolvency procedure, the insolvency practitioner to be appointed is appointed as a provisional administrator. This provisional administrator can guide and oversee the sale of the enterprise. The sale itself will be conducted and executed immediately after the formal opening of the insolvency procedure by the administrator then appointed in full. The justification of the pre-pack is that although insolvency procedures are justified by the goal of value maximization for creditors, insolvency procedure are not the best setting to accomplish this.[43] Buyers know that the insolvency administrator is under a lot of pressure to make a quick sale. At the same time, the business is deteriorating fast. Key personal will look for another job, and suppliers will typically demand direct payment and also payment for old invoices. Under a pre-pack, the process of looking for a buyer takes place earlier. The overall goal is that the amount paid for the assets sold as a going concern will be higher compared to a lengthy and less well prepared forced public sale.

One of the main drawbacks of a pre-pack is that the most decisive action in the entire insolvency procedure, is already taken and completed within days or possibly hours after opening the procedure. Ordinary creditors are informed on the same day that their debtor is declared insolvent and that its business has been sold to another legal entity. Furthermore, they are informed that the proceeds are not sufficient to make any payment or only a very small payment on their claim.

If insolvency procedures prove to be ill equipped to do what they are supposed to, i. e., maximizing value for creditors, alternatives should be examined with an open mind. In both the UK and the Netherlands where the pre-pack is being used, there is however ample critique regarding the procedure, most notably as to sales to related parties. One should, however, at the same time not make too much out of pre-packs. A pre-pack has a pressure cooker effect. Almost everything that is good and bad about insolvency procedures, is condensed in time. There are no real possibilities of abuse that are unique or limited to a pre-packs.[44] Also outside pre-pack procedures unsecured creditors often receive nothing. Moreover, without a pre-pack procedure assets can be sold to old management or old shareholders. It is not uncommon that shareholders are the ones acquiring assets out of a normal open bidding procedure. A shareholder that aims to acquire assets through insolvency procedures, might even be well advised not to use the pre-pack because things then happen so fast and very much in the public eye. They might better try to acquire the company out of a less prepared insolvency procedure. Instead of being perceived as a thief in the night, the shareholder might be perceived as the rescuing angel if the shareholder steps in if after two weeks and no other serious buyers have presented themselves. The outcome is however the same. Also in case of a non pre-pack asset sale to shareholders, do the shareholders continue the business in a new legal entity. The pre-pack is, therefore, neither special nor different from the normal non-prepacked procedure. It does, however, bring to light clearly undesirable practices or outcomes. If rules on how to deal with related party transactions in case of pre-packs can be formulated, these same rules can also apply to asset sales to related parties in normal non pre-packaged insolvency procedures.

In case of asset sales to a related party, abuse lurks in the shadows. In England, it transpired that from of a data set of 499 pre-packs, that almost two-third constituted a sale to related parties.[45] Also in the Netherlands, often the shareholders or other related parties are the acquirers out of a pre-pack. The main risk related to pre-pack and other related party sales from the perspective of creditors,[46] is that they are written off to the level of what they would receive in case of liquidation and a piece-meal sale and that the shareholder tries to seize the going concern surplus. In order to understand this risk, a real life example of a pre-pack can be taken.

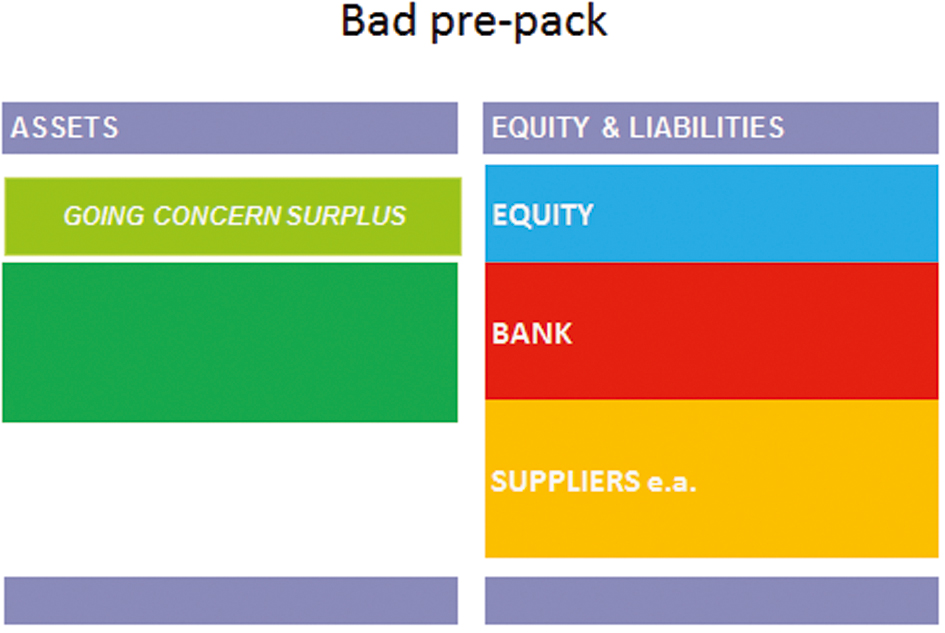

The most infamous pre-pack in the Netherlands is the Estro-case. Estro ran a children’s day care organization throughout the Netherlands for approximately 30,000 children. After consolidation of the market, Estro ended up in the hands of private equity parties. Following cut backs in government subsidies for daycare, Estro ran into financial difficulties. Mr Jongepier was appointed as a provisional administrator. He was confronted with the situation that if no solution could be found, 30,000 children would be without day care. Initially, the shareholder only wanted to pay slightly more than the liquidation value estimated at €4 million. Despite fierce resistance by the shareholder, Jongepier insisted that also other potential buyers would be contacted and invited to make a bid. This resulted in another party making a significant better bid. Subsequently and in response to this higher bid, the shareholder increased its bid to a level just a fraction higher than the competing bid amounting to approximately €10 million. So the shareholder tried rather aggressively to acquire the enterprise for its liquidation value of €4 million and tried to seize the surplus going concern value of at least €6 million. The diagram below depicts this by placing the going concern value at the level of the shareholder, without adding specific numbers since the dynamics should be clear.

Legislatures are confronted with the question of what to do. Should the shareholder be allowed to buy the business out of a pre-pack, or out of other assets sale for that matter? Should the shareholder be allowed to give it another try?

French law simply bans pre-pack sales to related parties.[47] English pre-pack practice relies foremost on disclosure requirements after the fact. The administrator must provide the creditors with an explanation of why a pre-pack was conducted.[48] Following critique on the pre-pack practice and the ensuing Graham Report with recommendations, English practice provides since 2015 for the option to have a proposed pre-pack reviewed by a pool of experts, but in no way bans the pre-pack sale to related parties. In a current Dutch legislative proposal, the legislature does not even identify the problem as such. It only provides for the following: “The court can make its permission to prepare a pre-pack dependent on such conditions as it sees fit in order to attain the goals of the pre-pack.” According to the explanatory memorandum, one of such additional conditions that could be imposed, is to require that in case of a related party sale, there would be a relatively short period of time during which other parties can make a higher bid.[49]

Preferably legislatures should take additional steps to solve the problem inherent to related party sales. However, Dutch law as proposed provides possibilities by allowing courts to impose additional conditions ‘as they see fit’. In either case, legislators or judges should impose as a condition, that in any sale to existing shareholders there will be a period in which i) an external party can make a higher bid, and much more novel that ii) an external party could match the bid by the shareholder. Under this proposed system, the old shareholder is allowed to make a bid, but other parties should always be allowed to acquire the entire business for that same amount. This ensures that the shareholder will immediately make its highest bid and that in case of matching bids, the business is transferred to new owners.

A principle of insolvency law will then be that insolvency has a cleansing effect and should also have this effect. Old shareholders should preferably not remain in position, also not via a new company. The preferred outcome is that after going through insolvency, the business is transferred to new owners. In case of matching bids, the business should therefore also move into the hands of a new party.

The proposal developed here, for a matching possibility of outside parties in case of a sale to shareholders, should be distinguished from the so-called stalking horse procedure as followed in the US.[50] In case of a stalking horse procedure, the bidder in a pre-pack procedure makes an offer that can be outbid by a higher offer from another party, with the agreement that a break-up fee will be paid to this first bidder in case of such a higher bid. This US practice has been developed to address the closed bidding environment of a pre-pack in general, also in case the bidder resulting from the pre-pack bidding phase is an external party. The problem of the shareholder being the highest bidder is an additional problem that needs to be addressed separately.[51] The way to do so, is to allow for matching bids. If one objects to this possibility, one needs to question the real motives of parties and again ask the question why it is that insolvency laws exist in the first place. Insolvency law does not exist to ensure that shareholders are granted deal certainty in case of insolvency. Insolvency law exists to capture the going concern value for creditors.

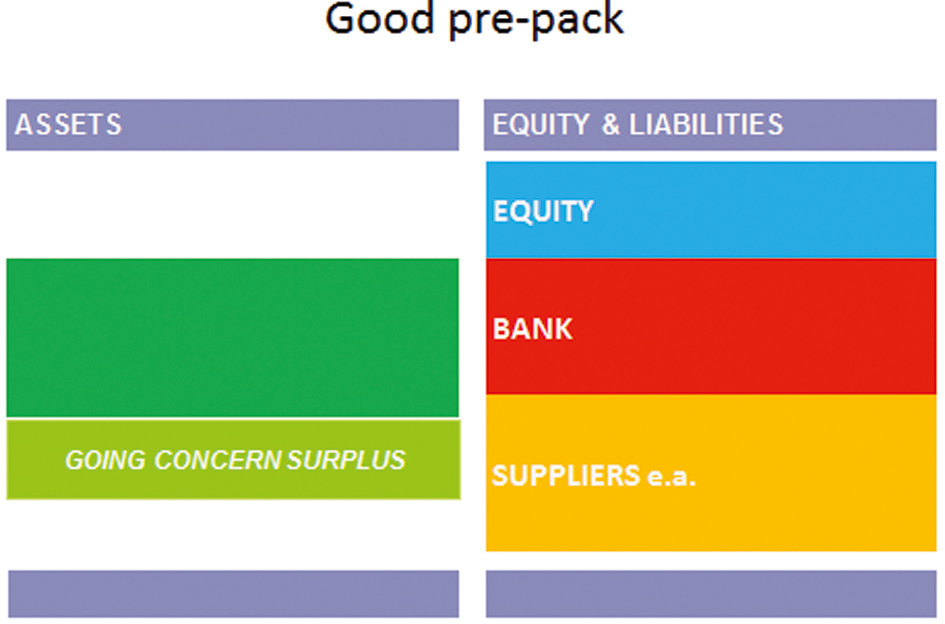

The balance sheet of a good pre-pack can be contrasted with the previous balance sheet of a bad pre-pack. A good pre-pack ensures the going concern value is captured and allocated to the creditors.

There is a second limitation that should be part and parcel of all pre-pack procedures and by extension to asset sales outside a pre-pack. The business sold by means of a pre-pack or other asset sale should be able to operate as an independent enterprise and the value should not be artificially depressed by means of asset partitioning. In case of asset partitioning, the assets of a single business or enterprise are divided over different legal entities. Requiring that the business should be able to operate as an independent enterprise and that the value should not be artificially depressed, seeks to address the problem of earmarked assets. In case of ear marked assets, the assets are basically only of real value for the group. A clear case can be found in the case of a chain of pizza stores, where the individual stores are run by separate legal entities and the shareholders company holds the IP rights and the brand.[52] If one of the operating companies becomes insolvent, its assets only have real value for the shareholder because the shareholder still holds the IP rights. The risk is that by means of asset partitioning, the shareholder can seize the going surplus value; first by taking the IP rights out of the operating company and then making a bid on the assets out of a liquidation sale of the operating company. In such a case the shareholder is making a bid on an incomplete puzzle in which he himself has the missing piece. In doing so, the shareholder can actively depress the value of the assets in the case of an asset sale. Since the shareholder himself has the missing pieces, he can always outbid other buyers. It should be recognized that this is a problem separate from the confidential bidding procedure during the pre-pack. Even if one would allow all competitors a full year to make a bid, none of them would be bidding any serious money on an incomplete puzzle. Without imposing the additional requirement for even allowing a pre-pack that the business should be able to operate as an independent enterprise and that the value should not be artificially depressed by means of asset partitioning, shareholders will start to see pre-packs and insolvency procedures in general as a viable alternative strategy. Even more problematic, shareholders will have clear incentives to structure the corporate group accordingly. An alternative solution, different from denying the pre-pack route, would be to deny the shareholders to bid on the assets as well or acquire them indirectly in case of asset partitioning.

The focus in academic debate evaluating the merits and risks of pre-packs has mainly been on the issue of whether in a specific case the highest price and subsequently pay out to creditors can be realized.[53] In the light of the above, a pre-pack or any other asset-sale cannot simply be judged by the answer to whether the highest price possible has been paid. The question is also whether insolvency procedures become an attractive alternative to restructure the business and shed debt. If the average pay out in normal liquidation procedures would be 15%, the pre-pack cannot be judged a success if the average payout would be 85% in case of pre-packs. The question does arise if, without the possibilities of a pre-pack, the shareholders would even have allowed the company to enter insolvency proceedings in the first place.

The key notion developed here, is that creditors should not be left with the liquidation value in case of pre-packs or other asset sales, but instead should receive the full going concern surplus. If not, the going surplus will flow to the shareholders. The law should be critical in case of related party sales. There is little concern of management and shareholders abusing pre-packs or insolvency law in general, if they really lose control over the company and its assets in the process. Pre-pack sales to non related parties should therefore be explored as a better alternative to unprepared liquidation procedures. If, however, the same shareholders are controlling the enterprise after going through an insolvency procedure, there is ample room for concern. The risk of abuse should be countered by allowing for matching bids and requiring that a enterprise sold out of a pre-pack can function in a stand-alone manner.

6. Shareholders under composition plans

The third setting in which insolvency law is at risk of turning against creditors is in the setting of reorganization procedures and composition plans, both in and prior to formal insolvency procedures. Here again, the risk is that creditors are left with the liquidation value and the shareholders try to usurp all or most of the going concern surplus. The proposed Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance does seeks to address this risk by introducing the Absolute Priority Rule (APR). This one of the most important rules in protecting creditors involved in reorganization plans. Commonly, the APR is a measure placed at the final stage of implementing a composition plan. Before discussing the APR in the proposed directive as part of a preventive restructuring framework in part § 6.2, the general working of composition plans as part of a reorganization and how the APR fits in will be discussed in part § 6.1.

6.1. Shareholders under composition plans in normal insolvency procedures

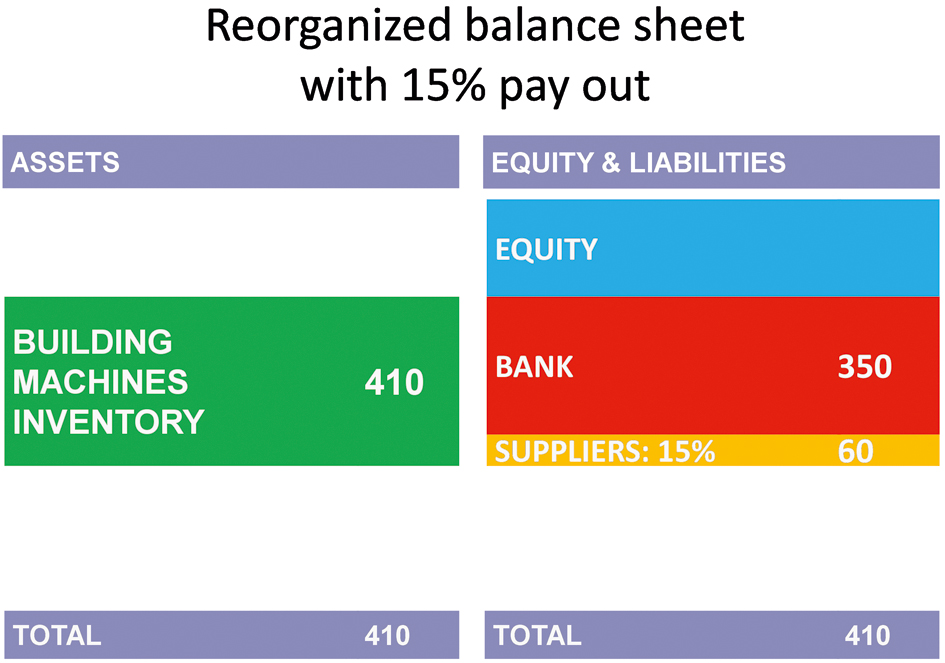

The most basic composition plan is one in which creditors in a formal insolvency procedure accept a discount on their claim and expect that they in the end will receive more than they would if the company and its assets were simply liquidated. This is also the way a basic composition plan is presented. With outside experts such as accountants, a calculation is made how much creditors can expect to receive in case of liquidation, for example 12.5%. The reorganization with a composition plan then typically provides for a higher pay out of say 15%. After the composition has been accepted, the debt is thereby reduced and the company is viable again. The creditors are better off compared to what they would have received compared to liquidation, and the company survives. There are good reasons why one might want to try to save not only the enterprise but also the legal entity itself. For example, due to licenses and contracts that could not be sold and transferred to a buyer out of an insolvency procedure.

Since it will be nearly impossible to have all creditors agree to the alternative of reorganization by means of a composition plan to straightforward liquidation, insolvency laws usually provides for majority rules. The problem that these voting rules address are not merely practical problems, but also more strategic opportunistic behavior displayed by creditors, referred to as hold out behavior. Hold out behavior could arise if one creditor thinks that, although a payout of 15% is to be preferred over a payout of 12,5%, he believes that if he withholds his consent, he might be able to force the other creditors to concede to allow for his single claim to be paid in full or at least more than the 15% offered. See on the underlying rationale of majority rules Bork, where he writes: “It should be obvious that unanimity is completely impractical. It would give any single creditor with a small claim the power to veto the restructuring, and with it grossly disproportionate leverage.”[54] Therefore, insolvency rules introduce majority rules by which a majority can also bind the minority. Different countries apply different thresholds, but normally there is a threshold both in amount and in number. Insolvency laws furthermore typically allow classes of creditors with similar interests to be created. As a starting point, in case of a division in classes, all classes have to accept the plan.

German law provides the debtor the possibility to restructure its debts by means of a so-called Insolvenzplan.[55] The creditors can be divided into classes, where the creditors within a class are to be treated equally.[56] For an Insolvenzplan to be accepted, it is required that within each class, at least half the number of creditors[57] vote in favor and that the creditors voting in favor represent at least half of the total amount held by all creditors voting.[58] Dutch Law applies similarly low thresholds for a plan to be accepted and requires that more than half of the number of unsecured creditors present at the meeting, representing at least half of the total outstanding debt vote in favor.[59] English law sets relatively high thresholds with respect to the creditors’ consent, which might be rather surprising in the light of its reputation of a reorganization friendly regime. An English Scheme of Arrangement requires the approval of a majority in excess of 75% in value of the creditors present in person or by proxy and voting on the resolution and a simple majority in number.[60] Under an English Scheme of Arrangement different classes can be created.[61] US law under chapter 11 requires a majority of two-third in amount and a majority in number of creditors.[62] Under a chapter 11 plan different classes can be created as well.[63]

Even if a a majority in each class accepts the plan, further checks need to be in place. In order to prevent plans that would provide that 80% of the creditors would accept a plan that provides that 20% does not receive anything, the adoption of a plan is not left to creditors’ majority vote entirely. In order for a plan to become binding also on the creditors that voted against it, the court needs to sanction the plan. The court typically cannot sanction a plan that makes some creditors worse off compared to a liquidation if these creditors do not consent. This is generally referred to as the ‘no-creditor worse off’ test. Reorganization procedures are justified by their potential to capture the going concern surplus. It is then not allowed to make some creditors worse off compared to their position in case of liquidation. The system of majority rules combined with a court review applying the ‘no-creditor worse off’ test, thereby allows dissenting creditors to be overruled by the majority of their own class.

There is also the possibility that an entire class of creditors votes against the plan and that this should be viewed as harmful hold-out behavior. Some jurisdictions therefore explicitly provide courts with the power to overrule an entire class. The court can basically do so, if the creditors cannot reasonably have voted as they did and the creditors are not worse off under the plan compared to their position in case of liquidation. Such a measure by which a court basically replaces creditor vote by a court ruling is referred to as a cram down. Germany, the US and the Netherlands provide for such cram down rules in case of a reorganization plans.[64] The UK does not explicitly allow for a cram down by the court.[65] Again, this can be seen as rather surprising, given the reputation of a very reorganization friendly regime.[66]

Although the ‘no-creditors worse off’ test might seem just fine at first sight, the test does not sufficiently protect creditors in the case of a cram down. Once more, the creditors are at risk of receiving only the liquidation value, where the shareholders usurp the going concern surplus.

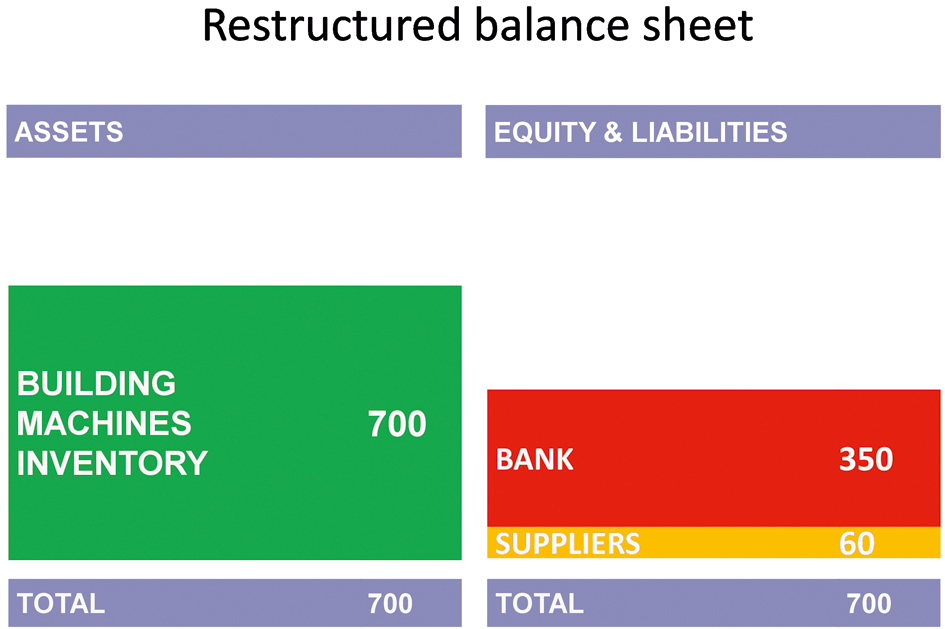

In order to see where the ‘no-creditor worse off’ test falls short in protecting creditors, one needs to put what is happening on a balance sheet. The case starts with moderately leveraged capital structure, with a €1000 worth in assets and €350 in bank lending and €400 in unsecured creditors, thereby resulting in an equity stake of €250.

If the company is facing liquidation with an estimated liquidation value of €400, the secured creditors would receive 350 and the unsecured creditors would have to share the remaining €50. The pay out to unsecured creditors would then be 12.5%, foregoing liquidation costs.

If the ‘no-creditor worse off’ test would be the only test and the court would have the power to overrule an entire class, creditors can be forced to be content with any higher distribution than the low water mark of their expected pay out in case of liquidation. The creditors should therefore accept a pay-out of 15%. If these numbers are put into the balance sheet, this leads to the following new balance sheet with a restructured capital structure.

The entire starting point is, however, that the company needs to be saved because the company is worth more going concern than liquidated piecemeal. So the going concern value is higher, for example 700. One could think that this is quite a lot higher and the spread between liquidation value and going concern value would be unrealistically large. The spread is, however, much smaller than was the case in the Estro-case discussed above (§ 5), were the liquidation value was €4 million and the going concern value at least €10 million. Furthermore, the value of the stand-alone assets is rather low in general. The real value of assets is realized when the assets are generating cash as part of a going concern enterprise.

What happens if the higher going concern value is put in a new balance sheet, in which the creditors have just been forced to accept a debt write down to 15%, meaning the total value of their claim being reduced to €60?

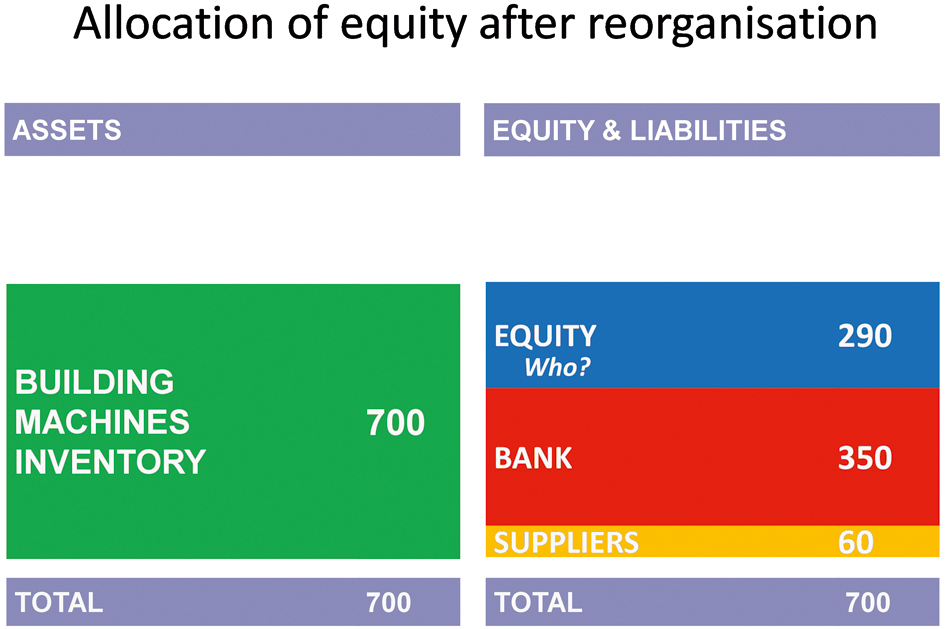

If the higher going concern value is put in the balance sheet, this results in positive equity, with a value of €290.

The big question is, who is entitled to this €290? If there are no further rules in place, this goes to the old shareholders. If the law allows to only write down debt up to the level that creditors would receive in case of liquidation or just slightly more, basically the entire going concern surplus would be usurped by shareholders.

Insolvency laws should, however, provide for rules allocating the entire going concern surplus in principle to the creditors in case of insolvency. As a starting point, this can be achieved by writing down creditors to the level at which the debt can realistically be repaid and subsequently giving the creditors that received this hair cut (i.e., a forced debt write down) the shares in the restructured company. This would amount to a debt for equity swap. Under a debt for equity swap, debts are not paid in full, but for the missing part on their claims, the creditors receive the shares in the company. In case of a reorganization and composition plans, creditors should as a starting point be able to claim all the shares in the restructured company, thereby claiming all equity appearing in the balance sheet created by accepting a debt write down. It should be remembered that equity is residual in the sense that it depicts whatever is left for the shareholders once all debts have been paid. Equity here becomes positive again by writing down debt.

In the US and Germany,[67] rules have been developed which provide that also in case of reorganization procedures, creditors rank above shareholders. A court in the US and Germany cannot cram down a dissenting class as long as a lower ranking class such as shareholders retain any value in the company. Such a rule is referred to as Absolute Priority Rule (“APR”).

The APR has been developed in the US and is commonly referred to as providing that creditors must be paid in full before any lower ranking creditor or shareholder may receive anything under a reorganization plan. This shorthand version, however, is too strong to properly describe what the APR stands for.[68] The APR as implemented in US law should be understood as protection against a cram down by the court. The APR is part of the more general requirement that a plan made binding on the creditors, not by majority rule, but instead by court cram down, needs to be fair and equitable as defined by USBC § 1129(b). A subtest hereof, is that the plan complies with the APR. The classic example of applying the APR is the situation where shareholders retain part or all of their equity, while creditors remain unpaid in full or in part. This would clearly be at odds with the basic premise that in case of insolvency equity is wiped out first. However, if the qualified majority of creditors – two-thirds in amount and a majority in number under US law[69] – were to accept such a plan, such a plan is allowed. The Absolute Priority Rule as codified in USBC § 1129(b) comes into play if the debtor would request the court to overrule a dissenting class while arguing that the creditors are not worse off under the plan and are even better off compared to liquidation. A better description of the functioning of the APR can therefore be found in the work of Baird and Jackson, where they explain the working of the APR as follows: “When a firm owes more than its assets are worth, the shareholders receive nothing unless the creditors consent.”[70]

The APR is not without critique[71] and certain exceptions should be made. In its recent proposal for revision of chapter 11, the American Bankruptcy Institute (ABI) formulated two exceptions. The first exception allows old shareholders to retain part of the equity if they provide new finance to the company.[72] The second exception proposed by ABI is more novel and would allow shareholders of small and medium enterprises (SME) to retain a stake in case the shareholders are instrumental to the continuation of the business, also if creditors would not consent as a class. The measure is referred to as the SME equity retention plan.[73]

The SME equity retention plan is presented by ABI as an exception for small cases. One could of course also take another approach and start with the SME rule and provide a more rigid application of the APR for large cases, with the large companies being the exception.[74] Whichever approach to the rule and the exception is taken, it merits to draw a distinction between large companies and small companies. In case of a SME companies there are often reasons to allow the old shareholders to retain part of the equity. The specific characteristics and skills of shareholders of large companies are commonly of far less or no importance for the actual continuation of the business compared to, for example those of the shareholders of a relatively small family owned violin manufacturing company. In the case of such smaller companies, the nature of and also the contribution by the shareholders is rather different. In such smaller companies, the shareholders are more than a capital provider and also provide know how and access to networks of relations. The different nature of these shareholders result in a need for their continued commitment and also allow for a deviation from strict APR rules based on a more principled law and economics approach which has at its foundation the notion of the shareholder as a pure capital provider. With respect to large companies, e. g. nation wide operating retail chains, there is also a much stronger tendency by shareholders of first deliberately overleveraging a company also by extension of payment terms to suppliers, and then in insolvency trying to hold on to the going concern surplus.

6.2. Shareholders under composition plans as part of a preventive restructuring framework

The previous paragraph introduced the APR as part of composition plans within a formal insolvency procedure. There is, however, a broadly shared notion evolving in Europe that the law should facilitate even more a second chance for companies. A company in financial dire straits should have more and better opportunities to get back on its feet. What is the problem that needs to be addressed that prevents these companies from doing so? The idea has taken hold that creditors have too much power. The company can possibly reach an agreement already outside of a formal insolvency with all creditors, except one or two. This again creates a hold-out position. The hold-out creditor could try to force the debtor to make full payment on its individual claim by holding out. Lacking further rules, the debtor would then be faced with the option to either enter full insolvency procedures or to pay the hold out creditor in full.

Prior to the proposed directive in November 2016, the Commission adopted a Recommendation on a New Approach to Business Failure and Insolvency in 2014.[75] The recommendation already encouraged Member States to provide for rules enabling debtors to restructure their capital structure without the need to formally open insolvency proceedings.[76] The Recommendation provided that outside a formal insolvency procedure debtors should be able to present a composition plan which – if adopted by the majority of creditors – should be confirmed by the court in accordance with national rules.[77]

The central argument from the Recommendation is now elaborated upon and upgraded into the proposed Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance. Section 4 of the proposed directive provides that Member States shall ensure that, where there is likelihood of insolvency, debtors in financial difficulty should have access to an effective preventive restructuring framework that enables them to restructure their debts or business, restore their viability and avoid insolvency. The most important shift for many continental legal systems is that the debtor should be allowed to remain in control and is not replaced by a court-appointed administrator or trustee.[78] The central element of the directive is to be found in sections 8 till 10, which provide that already prior to a full insolvency procedure, a composition plan can be offered, voted upon and made binding.

The proposed directive contains the ‘no-creditor worse off rule’,[79] as the recommendation did.[80] The Recommendation did, however, not contain an APR or any reference thereto.[81] Thereby it did not sufficiently protect creditors. Even more striking was that the recommendation did not pay any attention to shareholders of the company. The biggest change as to substance from the 2014 Recommendation to the 2016 proposal for the directive is that the directive explicitly addresses the position of shareholders by introducing the APR.

The APR in the directive takes the same place as it does under American and German law. It does not constitute a complete ban on shareholders receiving anything under a plan. It provides a limitation on the possibilities of the court to overrule a dissenting class of creditors if a lower ranking class receives anything, thereby a limitation on cram down. Section 11 of the directive provides that Member States shall ensure that a restructuring plan which is not approved by each and every class of affected parties may be confirmed where the restructuring plan: (a) complies with the ‘no-creditor worse off’ test, (b) has been approved by at least one class of affected creditors, and (c) complies with the absolute priority rule.[82] Although harmonization of composition plans inside formal insolvency procedures does not form part of the proposed directive, the directive will undoubtedly have strong harmonizing effects on composition plans inside formal insolvency.[83] It can be expected that the APR will also find its way into reorganization procedures part of full insolvency procedures.

The final question to be addressed is how the proposed directive with its APR relates to the other settings where shareholders can try to use insolvency procedures to further their own interest. Where under the proposed directive reorganization law in Europe will seek to ensure that creditors get the full going concern surplus, the question arises whether these principles can be circumvented by shareholders that finance their company by means of secured loans. In that case, the shareholder can claim priority over ordinary creditors in their capacity as creditor. The protection offered by the APR could then be easily rendered moot through the financing by means of secured shareholder loans. Furthermore, if rules on reorganization are designed to prevent shareholders from retaining the equity stake by means of capturing the going concern value, the rules on asset sales and most notably pre-pack sales also need to be reviewed as to related party sales. If the rules on reorganization ensure that equity is indeed wiped out and the rules on asset sales do not, the alternative of liquidation by means of a going concern asset sale become the most attractive route for shareholders.

7. Conclusion

The European Union is moving towards harmonization of substantive Insolvency Law, most notably by the proposal for a Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance.

In essence, insolvency law is collective debt collection law. By means of a collective procedure, insolvency law seeks to ensure that the going concern value is captured for the creditors. Whereas the shareholders possess the dominant voice outside of insolvency, in insolvency creditors take over this position and become the economic owners of the company.

In three different settings shareholders can interfere with the insolvency process and try to capture all value in the company or at least leave the creditors with the liquidation value and usurp the going concern surplus. These three settings are (i) shareholders as secured lenders, (ii) shareholders as acquirers out of pre-packs or other asset sales and (iii) shareholders under composition plans.

The phenomenon of shareholders trying to gain the upper hand in insolvency is all the more problematic in case of overleveraged companies if trade creditors have intentionally been forced into the position of credit provider by delaying payment terms and denying interest. Where the Late Payment Directive does not offer effective protection to SME’s from becoming a creditor, Insolvency law should not make the position of these trade creditors worse by allowing shareholders to prevail over trade creditors in insolvency as well.

The proposed directive contains measures in the field of composition plans as part of a preventive restructuring. The proposed directive addresses the potential problem that shareholders would usurp the going concern surplus by introducing the Absolute Priority Rule. The rule provides that creditors dissenting as a group cannot be forced to accept a reorganization plan if a lower ranking group, most notably shareholders, still retain value. The proposed directive thereby signals a sharp turn in the approach as to the position of shareholders in European Insolvency Law compared to the Proposal’s predecessor, the Recommendation on a New Approach to Business Failure and Insolvency from 2014. This turn is to be welcomed.

The directive should be considered a first step in the right direction. It should, however, be realized that the protection offered in the proposed directive could easily be circumvented by a shareholder financing not with capital but instead with secured shareholder loans. In that case the shareholder could claim all remaining value, not as a shareholder, but as a secured creditor. Also if the pre-pack and other sale processes do not limit interference by shareholders, shareholders will prefer the route of an asset sale over a reorganization.

The future of European insolvency law not only requires a level playing field, but also a fair playing field in line with insolvency law’s proper goal. The basic rule to abided by is that European insolvency law should uphold the debt-equity divide in insolvency.

© 2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Self-Dealing by Controlling Shareholders: Improving Minority Protection in Light of Article 9 c SRD

- The Norwegian Model for Access to the European Financial Markets: The Principles and Practicalities of the EEA States’ Solution to the Passporting Issue in Light of Brexit

- Redefining the Freedom of Establishment under EU Law as the Freedom to Choose the Applicable Company Law: A Discussion after the Judgment of the Court of Justice (Grand Chamber) of 25 October 2017 in Case C-106/16, Polbud

- Protectionism and the EU Market for Corporate Control: Is It Possible to Get the Best of Both Worlds?

- The Evolution of the Liability of Credit Rating Agencies in the United States and in the European Union: Regulation after the Crisis

- Harmonization of European Insolvency Law: Preventing Insolvency Law from Turning against Creditors by Upholding the Debt–Equity Divide

Articles in the same Issue

- Self-Dealing by Controlling Shareholders: Improving Minority Protection in Light of Article 9 c SRD

- The Norwegian Model for Access to the European Financial Markets: The Principles and Practicalities of the EEA States’ Solution to the Passporting Issue in Light of Brexit

- Redefining the Freedom of Establishment under EU Law as the Freedom to Choose the Applicable Company Law: A Discussion after the Judgment of the Court of Justice (Grand Chamber) of 25 October 2017 in Case C-106/16, Polbud

- Protectionism and the EU Market for Corporate Control: Is It Possible to Get the Best of Both Worlds?

- The Evolution of the Liability of Credit Rating Agencies in the United States and in the European Union: Regulation after the Crisis

- Harmonization of European Insolvency Law: Preventing Insolvency Law from Turning against Creditors by Upholding the Debt–Equity Divide