Abstract

Creativity is an important component of diagnostic reasoning, enabling the generation of novel and effective diagnostic hypotheses, in collaboration with abduction. The creative process not only fosters insight – critical for overcoming diagnostic challenges – but also enhances calibration by encouraging the exploration of alternative hypotheses. Insight, a key component of creativity, emerges when clinicians reconsider problems from fresh perspectives, breaking through diagnostic impasses. Similarly, calibration, essential for mitigating cognitive biases, promotes the generation and evaluation of alternative hypotheses. By fostering insight and calibration, creativity enhances precision and effectiveness of diagnostic reasoning. Leveraging insights from cognitive psychology to promote creativity can further elevate diagnostic reasoning, driving innovation and excellence in diagnosis. This article explores the pivotal role of creativity in diagnostic reasoning, its applications in diagnosis, approaches to nurture it, and its limitations, ultimately aiming to inspire innovation and excellence in the pursuit of diagnostic accuracy and patient care.

Introduction

Diagnosis is a fundamental physician competency. The diagnostic process involves multiple steps, and hypothesis generation remains central to the entire process. Once the diagnostic hypothesis is generated using a particular diagnostic strategy, a specific perspective is established. However, this perspective is often influenced by heuristics and cognitive biases. Although a specific perspective enables efficient selection and processing of information, it can sometimes lead to erroneous conclusions [1]. Moreover, even when an error is recognized, it can sometimes be difficult to shift away from an established perspective. In situations when cognitive biases strongly influence diagnostic reasoning and increase the risk of diagnostic errors, or when encountering challenging cases that lead to an impasse, it becomes necessary to generate hypotheses from a new perspective. These are precisely the moments when creativity must be exercised. By definition, creativity involves generating novel and useful ideas or solutions, which inherently requires looking at problems from fresh perspectives [2]. We can say that a perspective is novel when it is newly adopted within a thinking process, even if it was previously known [3].

Before discussing how creativity relates to diagnostic reasoning, it is necessary to organize the models of reasoning in diagnosis. Forms of reasoning include deduction, induction and abduction [4]. Induction derives general rules from specific observations (e.g., “All observed swans are white, so all swans must be white”) [4]. Abduction, on the other hand, involves inferring the plausible explanation for given facts (e.g., “The ground is wet; the best explanation is that it rained”) [4]. Diagnostic reasoning is conducted through the hypothetico-deductive method, where multiple hypotheses are generated based on observed patient information [5]. This process of hypothesis formation is abduction [4], [5], [6]. On the other hand, during the subsequent hypothesis testing process, deductive reasoning is involved, such as reasoning that “if a specific test result is positive/negative, the likelihood of a particular disease increases/decreases.” [5], 6] Additionally, in diagnostic reasoning, inductive reasoning may also play a role, as in cases where clinicians rely on past experiences with multiple similar cases that were diagnosed with the same disease [5], 6]. Therefore, diagnostic reasoning is a complex process involving multiple forms of reasoning. In diagnostic reasoning, the dual-process theory (DPT) [7] is well known; however, this theory encompasses not only reasoning but also other cognitive processes such as thinking and decision-making, making it a broad cognitive model [7]. Abduction, on the other hand, is a type of reasoning and is contrasted with deduction and induction. Since hypotheses can be formed intuitively from patient information or through analytical reasoning, abduction can occur through System 1 or System 2 processes [4].

Creativity: a factor that boosts hypothesis formation

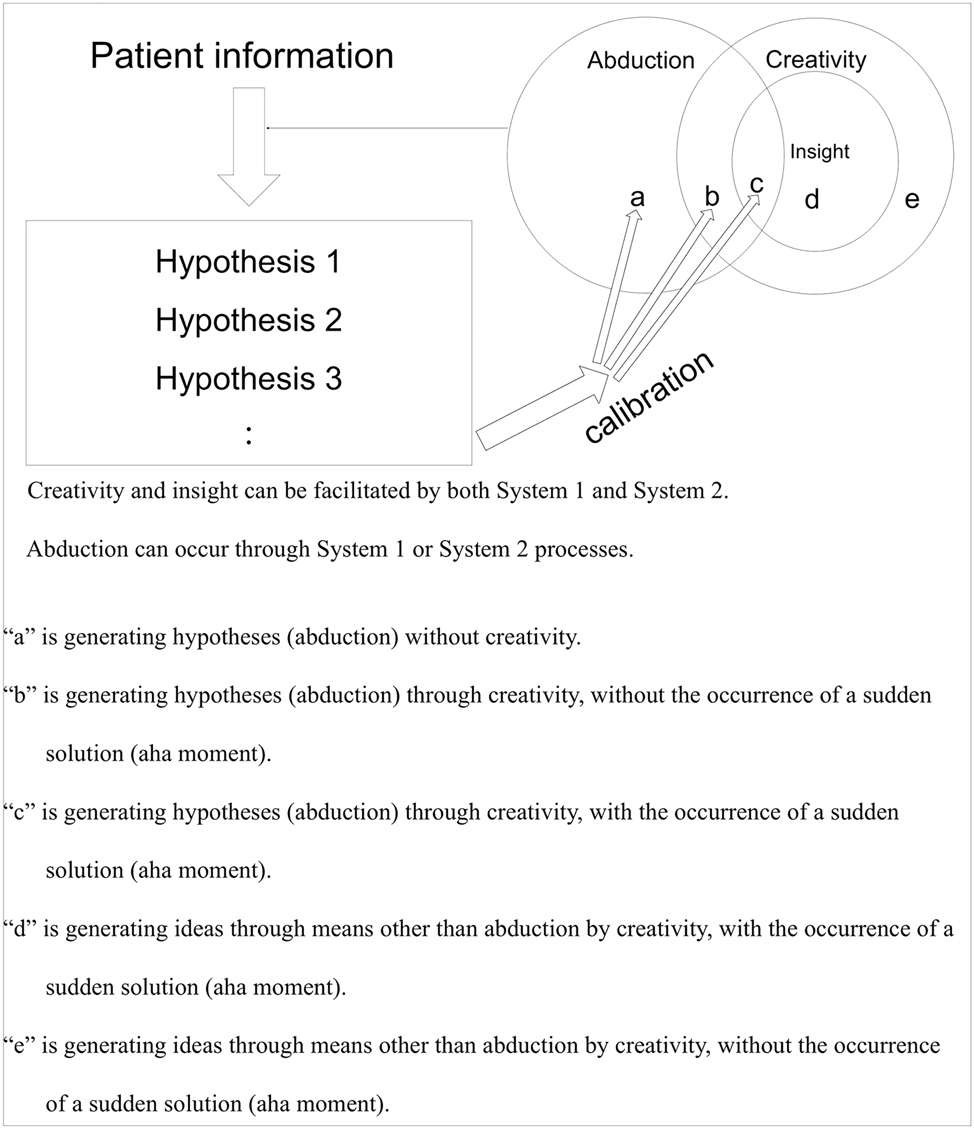

A crucial aspect of abduction is the ability to adopt new perspectives [8], which allows clinicians to reinterpret patient information. This reinterpretation can potentially uncover differential diagnoses that were previously overlooked. Importantly, adopting a new perspective aligns closely with the concept of creativity. Thus, when clinicians engage in abduction through the reinterpretation of patient information from new perspectives, they are demonstrating creativity [8] (Figure 1). This point underscores the overlap between creativity and abduction, particularly in diagnostic reasoning. Clinicians sometimes experience a sudden realization of a solution, accompanied by exhilaration of an “Aha! I see!” moment, after being stuck on a problem [9]. In cognitive psychology, this type of problem-solving is referred to as “insight problem-solving” [10]. Since fostering insight requires reinterpreting the problem from a new perspective, insight problem-solving is considered a part of creativity (Figure 1). Therefore, separate and distinct efforts to enhance creativity and insight are unnecessary, as efforts to promote creativity naturally lead to new insights. Insight is always included in creativity. This implies that when diagnostic reasoning reaches a diagnostic reasoning stagnate, efforts to foster creativity may enable the manifestation of insight, allowing new diagnostic hypotheses to be generated at an earlier stage. A shift in perspective can occur through analytical thinking as well as in an unconscious state (which will be discussed later [11], 12]), meaning that creativity and insight can be facilitated by both System 1 and System 2 processes. The type of “new perspective” that is most beneficial varies depending on the case. After hypothesis formation, the next step is hypothesis testing, where new ideas are evaluated to determine whether they lead to a more accurate diagnostic hypothesis. The process of generating specific diagnostic hypotheses involves brainstorming, either individually or collaboratively, to formulate potential hypotheses. Among these, those deemed to have higher plausibility are selected, prioritized, and subsequently tested. If the new idea proves to be more accurate, it confirms that the new perspective was beneficial. In creative thinking, ideas are generated through divergent thinking, while useful ideas are selected through convergent thinking [13]. Hypothesis testing corresponds to the process of convergent thinking.

Relationship between creativity, insight, abduction, calibration and DPT.

Creativity can be activated in situations of diagnostic reasoning stagnate and in other contexts. Creativity can also aid in the pursuit of successful calibration. To improve diagnosis, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has proposed a structured series of steps aimed at enhancing calibration (Calibrate Dx: A Resource To Improve Diagnostic Decisions). In this step, clinicians evaluate their clinical practice either independently or with the help of others. To evaluate their thoughts, they need to explore alternative diagnoses or different diagnostic approaches, which essentially means pursuing new perspectives, in alignment with critical thinking. Thus, creativity is essential for improving diagnosis via not only diagnostic thinking processes but also calibration. Calibration can often be achieved through checklists, clinical guidelines, and Bayesian reasoning, but creativity is not equivalent to these. Creativity fundamentally involves generating novel and useful ideas through a shift in perspective, which requires specific methods for facilitating such shifts. Checklists, guidelines, and Bayesian reasoning can also serve as tools to support this process.

Here, we describe an example of the types of hypothesis generation shown in Figure 1. A 52-year-old man presented with chronic episodic chest pain, and the clinician considered angina and gastroesophageal reflux disease (a). However, given that the patient had no history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes, did not experience chest pain during exertion, and did not have symptoms occurring at night, the likelihood of angina was considered low. Additionally, since the patient did not report regurgitation or heartburn, and the symptoms were not more likely to occur after meals, the clinician considered the likelihood of gastroesophageal reflux disease to be low. Recognizing the need to think from a new perspective, the clinician decided to utilize an anatomical approach [14]. This led the clinician to consider the possibility of neuralgia in addition to cardiac and esophageal conditions. Upon further inquiry about exacerbating factors, the patient experienced chest pain when extending the neck. A cervical spine MRI revealed the presence of a cervical disc herniation. When thinking from a new perspective leads to the consideration of neuralgia as a possibility, it corresponds to “b” if no “aha moment” occurs and to “c” if it is accompanied by an “aha moment.” Examples of “d” or “e” include “association.” Whether shifting perspective is genuinely “creative” or simply good thorough reasoning depends on individuals. For example, even in cases where a correct diagnosis can be reached through standard analytical reasoning, an expert clinician who is too fixated on a particular viewpoint may still feel that they have demonstrated creativity or gained insight when they manage to shift their perspective. In fact, it has been suggested that even with the same insight problem, some individuals experience insight while others do not [10]. Formalizing the role of one’s thinking process in diagram form would be reproducible and valuable in reflection. Moreover, as indicated previously, pursuing creativity in diagnostic reasoning can be said to promote “insight” (i) factor, as illustrated in the equation of physicians’ diagnostic reasoning expertise [15].

How can creativity be nurtured in light of cognitive psychology?

Creativity might be misunderstood as something that individuals with specific talents suddenly exhibit without any special effort. Rather, creativity is considered to arise from the functioning of cognitive abilities inherent to humans in general and from interactions among various internal and external factors [3]. Therefore, creativity can be developed and nurtured in several ways.

Metacognition

One method is metacognition, which involves the reinterpretation of an object from a new perspective [16]. Monitoring one’s own thinking processes and making flexible judgments without being constrained by past knowledge or experiences leads to creativity. Moreover, it is necessary to determine how to carry out subsequent thoughts and actions specifically [17]. In diagnostic reasoning, metacognition would correspond to implementing specific thinking strategies to reconsider the problem from a new perspective.

Example of metacognition

A man in his 70s presented for evaluation of generalized lymphadenopathy, weight loss, and night sweats. The enlarged lymph nodes were mobile and demonstrated a soft, elastic consistency. The clinician, noting a constellation of symptoms and unexpectedly elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, suspected malignant lymphoma and planned to schedule a lymph node biopsy. Upon further review of the referral letter, the soluble IL-2 receptor levels from the previous physician were normal. While considering malignant lymphoma with normal soluble IL-2 receptor levels, the clinician recognized the risk of being influenced by anchoring bias. Therefore, he or she deliberately searched for other features of the patient and tried to generate additional diagnostic hypotheses from a different perspective. The clinician reviewed the previous computed tomography scan and noted findings suggestive of osteoblastic bone metastases. This led to the consideration of prostate cancer. A prostate-specific antigen test revealed markedly elevated levels. Before proceeding with a lymph node biopsy, the clinician ordered a magnetic resonance imaging scan, which revealed findings suggestive of prostate cancer. The final diagnosis was metastatic prostate cancer with multiple lymph node involvement.

Explanation

In this case, anchoring [18] led to an overestimation of malignant lymphoma, increasing the risk of diagnostic error. To counteract this, after generating diagnostic hypotheses, metacognition was applied by focusing on the specific patient characteristics to develop differential diagnoses. The clinician was able to “shift focus to different features within the patient’s information and reassess the differential diagnosis (Weigh anchor [19]),” gaining a new perspective. In this process, the clinician reviewed the referral letter, including the examination results from the previous physician. As a result, the clinician noticed osteoblastic bone metastases on the CT scan. The clinician could generate a diagnostic hypothesis of prostate cancer, ultimately avoiding a diagnostic error. To promote creativity through metacognition, it is essential to determine how to think from a new perspective. The authors previously developed a framework for facilitating insight in diagnostic reasoning based on cognitive psychology theories [20]. These thinking methods would likely be included within the process of thinking from a new perspective.

Collaboration with others

An additional method of facilitating creativity is collaboration with others [21]. Others often have different perspectives that are new to your own. For this reason, interaction with more than one person will provide an opportunity to gain new perspectives, thereby enhancing creativity. For successful collaboration, maintaining open-mindedness is crucial. Creativity requires reinterpreting objects from a new perspective, necessitating an open-minded attitude to accept information without preconceived notions, broadly [22].

Example of collaboration with others

An intern resident had already diagnosed several cases of influenza by testing on a particular day. A woman in her 30s presented with fever and sore throat that had started a few days prior. The rapid influenza test was negative; however, the intern suspected a false negative and considered prescribing antiviral medication for influenza. The attending physician noticed that the absence of findings such as redness or lymphoid follicles in the pharynx was atypical for influenza, given the complaint of sore throat. Simultaneously, the physician was concerned about the unusually elevated heart rate. Therefore, the supervising physician judged it premature to consider the negative influenza rapid test result as a false negative and instead generated a diagnostic hypothesis of subacute thyroiditis. After conducting additional questioning, the patient also reported experiencing palpitations. The patient had thyroid tenderness, and her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were low and free thyroxine levels were high. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

Explanation

Diagnostic speculation can differ depending on clinical experience; accordingly, collaborating with others [21] can provide a new perspective, which may enhance creativity. When collaboration with others is difficult, one can intentionally reconsider one's own thinking as if it were someone else’s (rethinking from a zero base) [23]. This approach can provide a new perspective and potentially enhance creativity [24].

Other methods

Unconscious states are also related to creativity [11], 12]. A positive psychological state is an essential factor in enhancing creativity. For example, positive emotions can enrich problem-solving and idea generation [11]. Avoiding a fear of failure is also essential [12]. Furthermore, adequate sleep can help organize information unconsciously and increase the likelihood of gaining new perspectives [25]. In other words, shifting perspective is necessary to foster creativity, and this is facilitated not only by conscious analysis, such as examples in this article, but also by unconscious processes.

Environmental factors, as well as verbalizing one’s thoughts and representing them visually through diagrams, have been shown to enhance creativity. These strategies may also be helpful in diagnostic reasoning. For example, creativity has been shown to be greater for a cluttered desk than for a neat and tidy one [26]. Additionally, a moderate noise level, neither too quiet nor too loud, can lead to better performance on creative tasks [27].

Furthermore, the process of designers reviewing their ideas visually through sketches to gain new perspectives has been associated with creativity [28]. This can also be applied to diagnostic reasoning. Documenting one’s thoughts in the medical record allows for a review of one’s thinking, potentially enhancing creativity. However, verbalizing thoughts may result in a stronger focus on specific features of patient information, potentially hindering the ability to reconsider the case from a new perspective. This is known as the “language barrier effect” [29].

In situations of uncertainty where predictions are difficult, effectuation is considered effective. Effectuation involves utilizing available means and resources, including those obtained from partners. It may also involve reinterpreting elements from a new perspective and using them creatively. There is evidence that utilizing effectuation can increase creativity [30]. In clinical practice, diagnostic strategies utilizing effectuation have been proposed for situations with high uncertainty. Using this approach can promote creativity as well [31].

Discussion

This article re-evaluates diagnostic reasoning in view of creativity, facilitating the generation of additional diagnostic hypotheses, thereby advancing the timeliness and efficiency dimensions of diagnostic excellence.

Methods to promote creativity that are easy to apply in diagnostic reasoning may include metacognition and collaboration with others. However, as mentioned above, many other conditions and methods can promote creativity. It is necessary to verify the beneficial effects of these methods on creativity in diagnostic reasoning. Furthermore, future methods and conditions beyond those mentioned above can be explored.

Limitations of creativity include dependence on new perspectives, variability of individual creativity, and misconception of creativity. First, as creativity inherently relies on adopting new perspectives, it is sometimes challenging for clinicians to develop such perspectives, especially in high-pressure clinical environments. Inexperienced clinicians may struggle to adopt novel viewpoints in many cases. A “new perspective” includes concepts in diagnostic strategies [14], such as an anatomical approach or “weighing anchor” [19], as discussed in the case examples. Therefore, becoming familiar with various diagnostic strategies in daily practice and developing new strategies can facilitate the adoption of “new perspectives” in clinical settings. Inexperienced clinicians need to master a structured approach, which corresponds to the development of routine expertise. Routine experts refine their skills over time through repeated practice, allowing them to perform tasks more efficiently. In contrast, adaptive expertise represents a complementary form of expertise. Adaptive experts fluidly and flexibly access their knowledge networks, adapting to new situations while generating creativity and innovation [32]. In diagnostic reasoning, adaptive expertise is closely related to the concept of creativity introduced in this paper. When faced with complex cases or atypical diseases, clinicians must flexibly reconstruct their existing knowledge and explore diagnoses from new perspectives – an ability that characterizes adaptive expertise. This process inherently requires creative thinking [33]. Therefore, in diagnostic education, it is essential to establish a foundation that fosters routine expertise while gradually incorporating creative approaches to develop adaptive expertise. Adaptive expertise and creativity interact with each other, and as clinicians gain experience and deepen their knowledge, their diagnostic abilities become more flexible and innovative [33].

Second, the propensity for creativity varies widely among individuals and is affected by experience, emotion, or cognitive bias. Therefore, reliance on creativity as a cornerstone of diagnostic reasoning may not yield consistent results across diverse clinicians.

Third, an emphasis on creativity can inadvertently lead to downplaying the importance of evidence-based practice for those medical practitioners who adhere to misconceptions about the secular image evoked by the word creativity. In fact, however, abduction is important in both DPT processes, and the concept of creativity that it encompasses promotes, rather than prevents or downplays, evidence-based practice. For this reason, an accurate understanding by medical practitioners of the definition and existing concepts of creativity described in this paper will be important for the quality of diagnosis. From this point of view, the importance of creativity as described in this paper cannot be ignored.

Conclusions

Creativity serves as a vital driver in diagnostic reasoning, enabling clinicians to generate novel and effective diagnostic hypotheses by adopting new perspectives. Through its inherent connection with abduction and insight, creativity fosters the exploration of alternative diagnostic possibilities, mitigates cognitive biases, and enhances calibration. These qualities underscore its indispensable role in improving diagnosis. This paper highlights the potential of creativity to address diagnostic challenges, offering practical strategies, such as metacognition and collaboration, to nurture creative thinking. However, various limitations, such as the variability in individual creativity, dependence on novel perspective development, and potential for misconceptions stemming from the lay or cultural connotations of the term ‘creativity’, underscore the need for further studies aimed at implementation in clinical practice.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable. The cases demonstrated in this manuscript were entirely fabricated and designed purely for explanatory reasons. They do not depict factual individuals or circumstances, and any similarity to real-life people or incidents is coincidental.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Graber, ML, Franklin, N, Gordon, N. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1493–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Runco, MA, Jaeger, GJ. The standard definition of creativity. Creat Res J 2012;24:92–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092.Search in Google Scholar

3. Sternberg, RJ, Lubart, TI. The concept of creativity: prospects and paradigms. In: Sternberg, RJ, editor. Handbook of creativity. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999:3–15 pp.10.1017/CBO9780511807916.003Search in Google Scholar

4. Veen, M. Creative leaps in theory: the might of abduction. Adv Health Sci Educ 2021;26:1173–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10057-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Osimani, B. Modus tollens probabilized: deductive and inductive methods in medical diagnosis. MEDIC 2009;17:43–59.Search in Google Scholar

6. Behfar, K, Okhuysen, G. Perspective – discovery within validation logic: deliberately surfacing, complementing, and substituting abductive reasoning in hypothetico-deductive inquiry. Organ Sci 2018;29:323–40. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1193.Search in Google Scholar

7. Croskerry, P. A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Acad Med 2009;84:1022–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181ace703.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Gonzalez, M, Haselager, W. Creativity: surprise and abductive reasoning. Semiotica 2005;153:325–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2005.2005.153-1-4.325.Search in Google Scholar

9. Shimizu, T, Graber, M. How insight contributes to diagnostic excellence. Diagnosis 2022;9:311–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2022-0007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ohlsson, S. Information-processing explanations of insight and related phenomena. In: Keane, M, Gilhooly, K, editors. Advances in the psychology of thinking. Birmingham: harvester-wheatsheaf; 1992.Search in Google Scholar

11. Isen, AM, Daubman, KA, Nowicki, GP. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;52:1122–31. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.52.6.1122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Karwowski, M, Lebuda, I. The big five, the huge two, and creative self-beliefs: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 2015;10:214–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000035.Search in Google Scholar

13. Colzato, LS, Ozturk, A, Hommel, B. Meditate to create: the impact of focused-attention and open-monitoring training on convergent and divergent thinking. Front Psychol 2012;3:116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Shimizu, T. System 2 diagnostic process for the next generation of physicians: “Inside” and “Outside” brain – the interplay between human and machine. Diagnostics 2022;12:356. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12020356.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Shimizu, T, Graber, ML. An equation for excellence in clinical reasoning. Diagnosis 2022;10:61–3. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2022-0060.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Yoshida, Y, Hattori, M. The impact of metacognitive processing in creative problem solving. Cogn Sci 2002;9:89–102.Search in Google Scholar

17. Cloude, EB, Wiedbusch, MD, Dever, DA, Torre, D, Azevedo, R. The role of metacognition and self-regulation on clinical reasoning: leveraging multimodal learning analytics to transform medical education. In: Giannakos, M, Spikol, D, Di Mitri, D, Sharma, K, Ocoa, X, Hammad, R, editors. The multimodal learning analytics handbook. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022:105–29 pp.10.1007/978-3-031-08076-0_5Search in Google Scholar

18. Tversky, A, Kahneman, D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristic and biases. Science 1974;185:1124–30.10.1126/science.185.4157.1124Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Shimizu, T. NEJM clinical problem solving; Taro’s alternative reasoning. Tokyo: Nankodo Co., Ltd; 2024.Search in Google Scholar

20. Isoda, S, Shimizu, T, Suzuki, T. FRAMED: a framework facilitating insight problem solving. Diagnosis 2024;11:240–3. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2023-0152.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Muraya, R, Sakata, M. Effect of collaboration on creativity tasks. Inf Process Soc Jpn 2018:299–300.Search in Google Scholar

22. Carson, SH. Creativity and psychopathology: a shared vulnerability model. Can J Psychiatr 2011;56:144–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600304.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Yokose, M, Harada, Y, Shimizu, T. The reply. Am J Med 2020;133:e328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.02.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Kodera, R, Kiyokawa, S, Ashikaga, J, Ueda, K. The effect of observation in collaborative problem solving and its significance: the impact of recognizing the actions of the observed subject on insight problem solving. Cogn Sci 2011;18:114–26.10.1037/e621652012-016Search in Google Scholar

25. Wagner, U, Gais, S, Haider, H, Verleger, R, Born, J. Sleep inspires insight. Nature 2004;427:352–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02223.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Vohs, KD, Redden, JP, Rahinel, R. Physical order produces healthy choices, generosity, and conventionality, whereas disorder produces creativity. Psychol Sci 2013;24:1860–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613480186.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Mehta, R, Zhu, R, Cheema, A. Is noise always bad? Exploring the effects of ambient noise on creative cognition. J Consum Res 2012;39:784–97. https://doi.org/10.1086/665048.Search in Google Scholar

28. Verstijnen, I, Leeuwen, C, Goldschmidt, G, Hamel, R, Hennessey, J. Creative discovery in imagery and perception: combining is relatively easy, restructuring takes a sketch. Acta Psychol 1998;99:177–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-6918(98)00010-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Schooler, JW, Ohlsson, S, Brooks, K. Thoughts beyond words: when language overshadows insight. J Exp Psychol Gen 1993;122:166–83. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-3445.122.2.166.Search in Google Scholar

30. Blauth, M, Mauer, R, Brettel, M. Fostering creativity in new product development through entrepreneurial decision making. Creat Innov Manag 2014;23:495–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12094.Search in Google Scholar

31. Amano, M, Harada, Y, Shimizu, T. Effectual diagnostic approach: a new strategy to achieve diagnostic excellence in high diagnostic uncertainty. Int J Gen Med 2022;15:8327–32. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.s389691.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Kua, J, Lim, WS, Teo, W, Edwards, RA. A scoping review of adaptive expertise in education. Med Teach 2021;43:347–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1851020.Search in Google Scholar

33. Gube, M, Lajoie, S. Adaptive expertise and creative thinking: a synthetic review and implications for practice. Think Skills Creat 2020;35:100630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100630.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.