Abstract

Placental invasion anomalies are divided into three according to invasion of uterine wall as placenta accreta, increta and percreta. In placenta percreta, the most severe but the least common form, the placenta invades the full thickness of the uterine wall and also it can attach to adjacent organs in the abdomen like the bladder and rectum. It is a potentially life treating condition. There is no recommended management strategy for placenta percreta. We herein report two cases managed differently and discuss the management options in the light of the literature.

Introduction

Invasive placenta refers to conditions in which placental villi abnormally adheres deeply into the wall of the uterus as a result of the absence of decidua basalis or defects in the Nitabuch’s layer.

Placental invasion anomalies are divided into three according to invasion of uterine wall as placenta accreta, increta and percreta. In placenta percreta, the most severe but the least common form, the placenta invades the full thickness of the uterine wall and also it can attach to adjacent organs in the abdomen like the bladder and rectum. Invasion anomalies are becoming more common as cesarean section and other uterine surgeries increases. It is a potentially life treating condition. It is also the most common cause of emergency hysterectomy.

We herein report two cases managed differently and discuss the management options in the light of the literature.

Presentation of the cases

Case 1

A 30-year-old woman gravida 4 and parity 3 with previous three cesarean section was referred to our hospital due to the diagnosis of placenta previa totalis accompanying at 36 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound examination and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed placenta percreta. Elective termination of pregnancy by cesarean section was agreed and multidisciplinary cooperation was managed before the operation. The patient declined to have a hysterectomy. Diagnosis was confirmed intraoperatively and invasion of the placenta to the left istmic region of the uterus was observed. A transverse incision was done 2 cm under the round ligament, an area free from placenta, and a male fetus weighting 2900 g was delivered with Apgar score 9 at first minute and 10 at fifth minute. The Umbilical cord was cut and ligated approximately 2 cm from the placenta. It was left in situ to avoid massive hemorrhage. The uterus was closed in three layers and a hemovac drain was located before abdominal closure. Uterotonics were not used and Endol 100 mg supp. (Deva, Istanbul, Turkey) was given in the first 24 h to inhibit uterine contractions and pain relief. As the patient was from a rural area of our region she was hospitalized for 40 days. She was discharged from the hospital at her request. Three days after discharge, she was referred to our hospital due to massive bleeding with the diagnosis of retained placenta. We understood from questioning the patient and the gynecologist who referred her to our hospital that the patient had experienced minor bleeding and had been admitted to a gynecologist nearby. The patient did not give her exact history and the gynecologist suspected a retained placenta and started uterotonics and attemped to remove it with Winter pliers. Massive bleeding started after this procedure and 5 units of blood were given before and during transfer of the patient to our unit. The patient refused hysterectomy and wanted the preservation of her fertility if possible. The patient underwent an emergency laparotomy. A bilateral uterine artery ligation was done. Partial prolapse of the placenta was found in the vaginal examination so it was removed by winter pliers. Then a Bakri balloon was inserted and inflated with 300 ml serum physiologic (Figure 1). Sutures were applied to both sides of the cervix to prevent movement of the Bakri balloon. Since the endometrial thickness was 17 mm before application of the Bakri balloon and the blood loss was minimal after application of the Bakri balloon, the operation was terminated. Third generation cephalosporine and metronidazole were started. In total 5 units of erytrocyte suspension and 5 units of fresh frozen plasmas were given intraoperatively and postoperatively. Leakage of 130 ml blood was observed in 24 h and the Bakri balloon was removed on the 3rd day. The patient was discharged from the hospital at the 7th day of operation.

Image of the intrauterine inflated Bakri balloon.

Case 2

A 27-year-old, gravida 2 and parity 1 patient was referred to our hospital with the diagnosis of placenta percreta accompanying placenta previa totalis at 35 weeks of pregnancy. The diagnosis of placenta percreta was confirmed by MRI. Detailed obstetric history revealed a cesarean section 3 years previously in which bilateral hypogastric artery ligation and application of B-Lynch suture were performed due to atonia causing postpartum hemorrhage. Under general anesthesia, a midline abdominal incision was used to reach the abdomen (Figure 2). Inspection revealed prominent placental invasion on the lower uterine serosa and visible plexus of blood vessels which also extended over the bladder peritoneum. A transverse incision was done below the level of insertion of round ligaments and a male infant weighing 2250 g was delivered was delivered by breech extraction with Apgar scores of 8 and 10 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. The placenta and its remnants were left in situ. A Foley drain was placed into the uterus to inhibit collection of blood due to history of uterine atony. As the postoperative application of arterial embolization was planned, proper ovarian ligaments were ligated to inhibit ovarian failure (Figure 3). Selective arterial embolization to the gluteus superior was done on the first postoperative day to reduce vascularization of placenta, risk of hemorrhage and to decrease the delay period for placental absorbtion. It was done by using polyvinyl alcohol particle (PVA; spheric) as a gelatin sponge was not available in the hospital. Three doses of methotrexate and folinic acid were applied on the 2nd, 9th, 16th and 3rd, 10th, 20th days of operations, respectively. The patient came from a rural area and refused the close follow-up, she then changed her mind and wanted to have hysterectomy. Twenty-one days after the first operation, the patient underwent a second operation to perform a hysterectomy although none of the complications of conservative management was observed. Exploration revealed that uterus was as big as a 4 months’ gestation and the istmic part was larger than the fundal part. Prominent vascular structures were still present between the uterus and bladder especially on the left istmic side of the uterus. A double j catheter was applied intraoperatively to avoid injury and infrarenal aortic occlusion was performed to avoid massive bleeding. After application of 1 ml of heparine, the aorta was clamped. Classical hysterectomy was performed and the blood vessels between the uterus and bladder were ligated seperately in each step. The Procedure lasted 35 min (Figure 4). Sponges were placed to the potential gaps in the pelvic area. A Foley condom catheter was also applied transvaginally and Foley condom was inflated with 500 ml of serum physiologic to apply pelvic packing. An abdominal drain was also placed to the left pelvic area. Two units of erytrocyte and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma were given peroperatively. The patient was discharged from the hospital at the 6th day of the operation.

The intraoperative image of the case.

The another intraoperative image of the uterus.

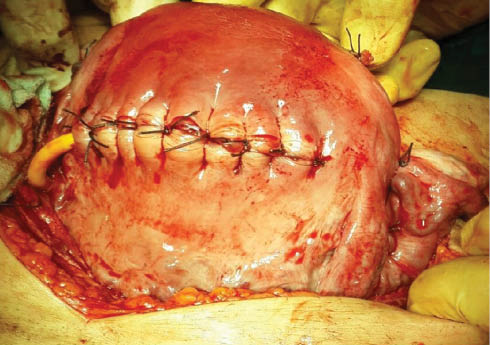

The postoperative image of the uterus.

Discussion

The incidence of placenta percreta increased with the increasing rate of cesarean delivery. Risk factors other than cesarean section include previous uterine procedures, Asherman’s syndrome, advanced maternal age, multiparity (>5), and placenta previa [1]. Both of our patients had a history of cesarean section.

Placenta percreta has high morbidity and mortality rate for both mother and fetus since it can be associated with prematurity, uterine rupture, perinatal death, massive blood tranfusion, urinary tract injury, infection and maternal death.

Prenatal diagnosis is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality. For diagnosis of placenta percreta, ultrasonography is the premier choice but differentiation of true infiltration of the bladder is difficult. MRI may be superior to ultrasonography in cases of posteriorly localized placenta [2]. But it must be kept in mind that all the imaging modalities may not give us the exact diagnosis about infiltration. Prenatal diagnosis gives the opportunity for timing the operation with the presence of a multidisciplinary surgical team comprising a consultant urologist, general surgeon, hematologist, neonatologist, anesthetist and an obstetrician experienced in pelvic surgery. Both of our cases had prenatal diagnosis and planned surgery was performed.

Timing of delivery must be individualized to optimize both maternal and fetal outcomes. According to a study done to determine the best time for delivery in clinically stable patients with the ultrasonographic findings of placenta accreta and placenta previa, it is found that delivery at 34 weeks of gestation without confirmation of lung maturity is the best (level of evidence: III) [3]. Elective termination at that week reduces both neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality. Our patients were above 34 weeks’ gestation at admittance to hospital and underwent surgery as soon as possible. No complications were observed in the newborns.

One of our patients had a history of application of a B-Lynch suture in her previous pregnancy due to uterine atony. Studies in the literature note that placement of compression sutures increases the risk of synechiae and sometimes causes partial or total necrosis of the uterine wall which may lead loss of decidua. In using these sutures it must be kept in mind that invasion anomalies will accompany the future pregnancies [4].

It is reported in the literature that premature ovarian failure is a common complication after UAE. In our second case we performed ligation of the utero-ovarian ligament during operation as the embolization of uterine arteries was planned to reduce risk of postoperative hemorrhage and accelerate the period for placental absorbtion.

We performed transverse fundal incision in our cases to avoid damage to the placenta and reduce fetal and maternal blood loss. This type of incision is mostly recommended for placenta previa cases involving the anterior part of the uterus. We think that fundal transverse incision can be a good choice in patients in which concervative management is planned as it reduces the risk of placental damage and massive bleeding from the placenta. The amount of bleeding from the incision was minimal in our cases.

There is no recommended management strategy. Hysterectomy is the traditional treatment of choice. Recent studies revealed that conservative management, which is defined as leaving the placenta partially or totally in situ without any attemp to remove it, leads to less blood transfusion and lesser hysterectomy rates [5]. Conservative management is mostly the first choice in patients desiring to preserve their fertility. Also conservative management must be a treatment option not only in patients desiring to preserve their fertility but in all patients with severe invasion of placenta to avoid massive hemorrhage and trauma to neighboring organs [6]. Concervative management option is a good chance for doctors not working in a tertiary center who diagnosed invasion anomaly intraoperatively without any preperation preoperatively. One or more of the following procedures commonly used as an additional method in conservative management; prophylactic ligation of the uterine or internal iliac arteries, treatment with methotrexate, embolization of vessels. In women with severe postpartum hemorrhage caused by invasion anomalies, pelvic embolization is mostly effective in stopping the bleeding and must be preferred when available [7]. It is effective even after failed surgery [8]. But since <50% of women with invasive placenta actually require embolization and transcatheter arterial embolization is not free from complication, this approach is not recommended as prophylactic in invasion anomalies before delivery [9].

Another advantage of arterial embolization in invasive placenta is that the delay for placental resorption is decreased when conservative management is performed [10]. It must be kept in mind that conservative management carries the risk of delayed hemorrhage and intrauterine infection.

Patients who undergo conservative management must be aware of the importance of close follow-up which may last for months after delivery and they must be patients who can reach to a tertiary hospital rapidly in cases of complications such as massive bleeding. We informed our patients about the long follow-up period and probable complications but we again faced problems with this. A document with detailed information about the procedure, must be given to the patient for use at other health facilities before being discharging from the hospital.

Concervative management is now an accepted management option and the favored one at many institutions for invasive placenta.

Irrespective of the treatment modality employed, all women with placenta percreta are at high risk of morbidity and mortality mostly due to hemorrhage. In the view of this fact, our main goal must be to avoid unnecessary cesarean sections.

Our main goal in writing this paper was to share our limited experience about placenta percreta and state its management in the light of the literature.

References

[1] Sivan E, Spira M, Achiron R, Rimon U, Golan G, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. Prophylactic pelvic artery catheterization and embolization in women with placenta accreta: can it prevent cesarean hysterectomy? Am J Perinatol. 2010;27:455–61.10.1055/s-0030-1247599Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Warshak CR, Ramos GA, Eskander R, Benirschke K, Saenz CC, Kelly TF, et al. Effect of predelivery diagnosis in 99 consecutive cases of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:65–9.10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c4f12aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Robinson BK, Grobman WA. Effectiveness of timing strategies for delivery of individuals with placenta previa and accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:835–42.10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f3588dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Poujade O, Grossetti A, Mougel L, Ceccaldi PF, Ducarme G, Luton D. Risk of synechiae following uterine compression sutures in the management of major postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:433–9.10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02817.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Khan M, Sachdeva P, Arora R, Bhasin S. Conservative management of morbidly adherant placenta – a case report and review of literature. Placenta. 2013;34:963–6.10.1016/j.placenta.2013.04.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Eller AG, Porter TF, Soisson P, Silver RM. Optimal management strategies for placenta accreta. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;116: 648–54.10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02037.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Soyer P, Morel O, Fargeaudou Y, Sirol M, Staub F, Boudiaf M, et al. Value of pelvic embolization in the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage due to placenta accreta, increta or percreta. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:729–35.10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.07.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Soyer P, Dohan A, Dautry R, Guerrache Y, Ricbourg A, Gayat E, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization for postpartum hemorrhage: indications, technique, results, and complications. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38:1068–81.10.1007/s00270-015-1054-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Mitty HA, Sterling KM, Alvarez M, Gendler R. Obstetric hemorrhage: prophylactic and emergency arterial catheterization and embolotherapy. Radiology. 1993;188:183–7.10.1148/radiology.188.1.8511294Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Pelage JP, Le Dref O, Mateo J, Soyer P, Jacob D, Kardache M, et al. Life-threatening primary postpartum hemorrhage: treatment with emergency selective arterial embolization. Radiology. 1998;208:359–62.10.1148/radiology.208.2.9680559Search in Google Scholar PubMed

-

The authors stated that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

©2016 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Case Reports – Obstetrics

- Management of extensive placenta percreta with induced fetal demise and delayed hysterectomy

- Spontaneous reposition of a posterior incarceration (“sacculation”) of the gravid uterus in the 3rd trimester

- Prenatal imaging and pathology of placental mesenchymal dysplasia: a report of three cases

- Management of two placenta percreta cases

- Intra-aortic balloon occlusion without fluoroscopy for life-threating post-partum hemorrhage

- Successful external cephalic version after preterm premature rupture of membranes utilizing amnioinfusion complicated by fetal femoral fracture

- Unprecedented bilateral humeral shaft fracture after cesarean section due to epileptic seizure per se

- Successful treatment of placenta previa totalis using the combination of a two-stage cesarean operation and uterine arteries embolization in a hybrid operating room

- Placental massive perivillous fibrinoid deposition is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases

- Case Reports – Fetus

- Post-delivery evaluation of morphological change in vein of galen aneurysmal malformation – possible parameter of long-term prognosis

- Osteogenesis Imperfecta type II with the variant c.4237G>A (p.Asp1413Asn) in COL1A1 in a dichorionic, diamniotic twin pregnancy

- A fetopathological and clinical study of the Dandy-Walker malformation and a literature review

- Prenatal diagnosis of holoprosencephaly with proboscis and cyclopia caused by monosomy 18p resulting from unbalanced whole-arm translocation of 18;21

- Prenatal diagnosis and management of Van der Woude syndrome

- A case of hereditary novel mutation in SLC26A2 gene (c.1796 A.> C) identified in a couple with a fetus affected with atelosteogenesis type 2 phenotype in an antecedent pregnancy

- Acardius-myelacephalus: management of a misdiagnosed case of twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence with tense polyhydramnios

- Case Reports – Newborn

- Neonatal spinal cord injury after an uncomplicated caesarean section

- Severe neonatal infection secondary to prenatal transmembranous ascending vaginal candidiasis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Case Reports – Obstetrics

- Management of extensive placenta percreta with induced fetal demise and delayed hysterectomy

- Spontaneous reposition of a posterior incarceration (“sacculation”) of the gravid uterus in the 3rd trimester

- Prenatal imaging and pathology of placental mesenchymal dysplasia: a report of three cases

- Management of two placenta percreta cases

- Intra-aortic balloon occlusion without fluoroscopy for life-threating post-partum hemorrhage

- Successful external cephalic version after preterm premature rupture of membranes utilizing amnioinfusion complicated by fetal femoral fracture

- Unprecedented bilateral humeral shaft fracture after cesarean section due to epileptic seizure per se

- Successful treatment of placenta previa totalis using the combination of a two-stage cesarean operation and uterine arteries embolization in a hybrid operating room

- Placental massive perivillous fibrinoid deposition is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases

- Case Reports – Fetus

- Post-delivery evaluation of morphological change in vein of galen aneurysmal malformation – possible parameter of long-term prognosis

- Osteogenesis Imperfecta type II with the variant c.4237G>A (p.Asp1413Asn) in COL1A1 in a dichorionic, diamniotic twin pregnancy

- A fetopathological and clinical study of the Dandy-Walker malformation and a literature review

- Prenatal diagnosis of holoprosencephaly with proboscis and cyclopia caused by monosomy 18p resulting from unbalanced whole-arm translocation of 18;21

- Prenatal diagnosis and management of Van der Woude syndrome

- A case of hereditary novel mutation in SLC26A2 gene (c.1796 A.> C) identified in a couple with a fetus affected with atelosteogenesis type 2 phenotype in an antecedent pregnancy

- Acardius-myelacephalus: management of a misdiagnosed case of twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence with tense polyhydramnios

- Case Reports – Newborn

- Neonatal spinal cord injury after an uncomplicated caesarean section

- Severe neonatal infection secondary to prenatal transmembranous ascending vaginal candidiasis