Abstract

We examine a network of over 40,000 tweets posted before the 2019 European election in Slovenia. The discussion observed is highly polarized: analysis of communication patterns reveals a partisan structure with limited connectivity between centre-left and right-leaning clusters. Users tend to communicate with like-minded peers and share content originating from their own communities. Bridges – accounts enabling the diffusion of content between ideologically different communities – are almost non-existent. Right-wing politicians are among the most prominent users in the network and can dominate the discourse within their communities. This shows that politicians effectively use Twitter as a strategic communications tool to engage with their supporters, spread their partisan messages and make use of the polarized social media environment. The data mirrors findings from other democracies, providing further evidence that polarization of political discourse is a prominent feature of the contemporary communication environment, present across various national, geographical and political contexts.

1 Introduction

Social media has become an important platform for political communication and discussion about public affairs, however, some key questions regarding the nature of increasingly personalized communication networks remain unanswered. Contemporary networked public spheres consist of a multitude of dispersed publics which are constantly forming, connecting with each other and dissolving according to the shared interests of their members. As Bruns puts it, the “public sphere is now irretrievably fractured into a multiplicity of online and offline, larger and smaller, more or less public spaces that frequently (and often serendipitously) overlap and intersect with one another” (Bruns, 2023, p. 70). Political communication takes place in a dynamic social media environment that can, paradoxically, at the same time foster connections to more stakeholders than ever before, while also being increasingly fragmented and polarized. This has led to increased warnings that citizens online tend to cluster into communities of similar and increasingly extreme views, sometimes referred to as filter bubbles (Pariser, 2011). Despite the popularity of the topic, there is no consensus about the prevalence of filter bubbles online. Several studies using various methods confirm the existence of closed communication spaces (Hong and Kim, 2016), while other influential scholars find that social media are in fact much more open environments, and claim that the idea of a filter bubble is nothing more than a buzzword (Bruns, 2019). In this study, we use quantitative analysis to study information diffusion on Twitter[1] in the context of pre-election political discussions, focusing on an under-researched area of Central and Eastern Europe, namely Slovenia. We build on existing research on political polarization on social media and contribute to the field by (1) providing empirical data on the extent of polarization; (2) examining the role of bridges which enable communication flows between different ideological communities; and (3) examining the role of politicians in polarized debates.

2 Literature review

Polarization and social media

Simply put, polarization refers to divisions between groups (Arguedas et al., 2022). From a normative perspective, political polarization is mostly seen as problematic phenomenon (Reiljan, 2020). Orhan argues that polarization is highly correlated with democratic backsliding (2022), while scholars often warn against society crumbling into an ungovernable mash of hostile communities. This might be especially true for political discussionsin which information is often exchanged among individuals with similar ideological preferences (Barberá et al., 2015). Some attribute this to the rise of social media platforms, which are often thought to be fostering polarization due to their economic models and algorithms favouring disagreement, sensationalism and novelty over rational exchange of opinions (Just and Latzer, 2016). Pariser introduced the idea of the filter bubble in 2011, warning that online search algorithms curate closed, personalized environments that exclude opposing views (Pariser, 2011). More than a decade later, the issue seems to have deepened, as technological platforms have multiplied the possibilities for constructing our personal bubbles. Most authors see filter bubbles as a state of intense polarization, theoretically underpinned by cognitive dissonance and selective exposure (Stroud, 2010); and communicative fragmentation, driven by a set of technological affordances and platforms’ business models (Aral, 2020). Consequently, we understand the term filter bubble in a broader sense as an environment of widespread communicative fragmentation and ideological polarization, observed as a community of users who predominantly communicate with each other and predominantly share content that conforms to the ideological views of the community.

Several empirical studies have documented the presence of closed communities on Twitter in various political contexts such as the Brexit campaign (Bastos et al., 2018) or Brazilian presidential election (Cota et al., 2019), suggesting that they contribute to societal fragmentation. Political information was found to be more likely retweeted if received from ideologically similar sources (Barberá et al., 2015), with clustering around partisan sources particularly prevalent among conservative users (Benkler et al., 2017). Various authors, on the other hand, claim that the term filter bubble as a metaphor for completely isolated communities does not reflect the realities of the contemporary social media landscape (Borgesius et al., 2016; Bright et al., 2020; Bruns, 2017; Nguyen, 2020). Research has shown that isolated filter bubbles affect only a fraction of the online population (Dubois and Blank, 2018), while most social media users are embedded in ideologically diverse networks (Barberá, 2014). The current consensus suggests that while filter bubbles may exist to some extent, their prevalence and impact are not uniform and may vary depending on the context.

RQ1: Is online political discussion taking place within isolated clusters of likeminded users, or can information flow between communities with different views?

Bridges

As the social media environment appears to be increasingly fragmented, we should pay special attention to the users that are able to maintain connections with different communities. Bruns and Highfield (2016) see the conversations on social media as a multitude of ideologically homogeneous microspheres, connected by bridges – users that facilitate information flow between different communities, thereby enabling cross-cutting exposure to ideas. Their position keeps them informed about what is happening in different parts of the network and gives them the ability to spread information beyond the boundaries of homogeneous communities (Aral, 2020).

However, in polarized environments, such intermediaries might not be among the most visible users in the network. In political settings, popular and influential nodes are often publicly known figures and political elites with access to media and institutions (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014), while brokerage roles (bridges) are associated with nodes having the capacity to cover a variety of issues (Diani, 2003). As shown by Garimella et al., Twitter users who try to bridge homogeneous communities by sharing diverse content become a target of criticism and “pay a price in terms of network centrality, community connection, and endorsements from other users” (Garimella et al., 2018, p. 921) because they share content that is not always in line with prevalent community views. Similarly, the analysis of Spanish parliamentary Twitter networks finds that “the bridging role played by some MPs to link parliamentarians from different parties seems to be penalized by their peers” (Esteve Del Valle and Borge Bravo, 2018, p. 80).

RQ2: Who are the intermediaries that enable cross-cutting information flows, and what kind of communities are they bridging?

Central users and politicians

As social media are seen as technologies that are reshaping political communication (Jungherr et al., 2020) by empowering a multitude of political and social actors, the question remains whether traditional elites still enjoy central positions in online discussions. Some expect that leading politicians will dominate digital communication channels as social media reflect traditional power relations and social structures (Stromer-Galley, 2017); while others claim that social media can empower the rise of alternative voices (van Dijk and Hacker, 2018). The latter is confirmed by several fringe political parties and movements that have successfully used social media to place their agenda at the centre of public debate (Micó and Casero-Ripollés, 2014). Empirical studies provide mixed results, showing that while political and media elites maintain their influence on Twitter (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014), there is also evidence of new social actors gaining prominence as influencers (Casero-Ripollés, 2021). Further, empirical studies have shown that the ideology of political actors plays a major factor in gaining influence on Twitter (Casero-Ripollés et al., 2021). In a polarized environment, central users are often tied to a particular community, as they are “strategically and collectively selected by users based on the discursive resonance of their messages” (Dehghan, 2020, p. 190). These actors – Papacharissi (2016) calls them crowd-sourced elite – are often highly partisan as users champion opinion leaders who amplify their existing beliefs (Carpentier, 2017).

Especially interesting in this light is a possible role of politicians in fostering polarization and maintaining filter bubbles. Elite behavior was shown to be driving political polarization (Tucker et al., 2018) as politicians often tend to reinforce homogeneous ideas within polarized groups (Soares et al., 2018). Empirical studies found that politicians with extreme ideological positions have more followers (Hong and Kim, 2016) and may be incentivized to use polarizing rhetoric to increase the spread of their messages and engage parts of their electorate (Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021). Social media enables politicians to distribute individually tailored messages to their followers on a mass scale with little fear that the content will be contested by critics – meaning that the conventional limitations on political rhetoric, typically enforced through public scrutiny and debate, no longer apply (Kinkead and Douglas, 2020). Through the strategic use of social media, politicians can share content that appeals to their supporters while alienating those with differing views – a phenomenon observed, for instance, in discussions on climate change (Lasser et al., 2022). On the other hand, existing empirical work also suggests the opposite, highlighting the democratic potential of social media by enabling open spaces for discussion among politicians with different views, as shown, for example, by the empirical research that examines the use of Twitter by Dutch MPs (Esteve Del Valle et al., 2022). In this case, politicians were able to play a significant role in reducing polarization by enabling the diffusion of content among different groups of otherwise not connected users.

Content shared by political elites is affecting information flows and shaping online discourse, therefore it is important to gain a better understanding of the roles politicians play in the contemporary communication environment. Taken together, their roles relate to two key concepts discussed in this paper, namely polarization and bridging. Through their influence and action on Twitter, politicians might be fostering polarization and deepening divides between ideological clusters, or acting as bridging nodes that are enabling communication flows between different ideological communities.

RQ 3: What roles do politicians play in polarized debates on social media? Is their influence limited to their own community, or does it span across the network?

National context

This study aims to provide a complementary perspective to previous studies researching political polarization on social media by focusing on data from Slovenia, a small, young European democracy, where polarization in social media discourse has not been extensively studied before. Similar research has in the last decade suffered from a disproportional emphasis on samples from the United States (Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021). We follow remarks that encourage researchers to examine social media polarization outside of the U.S. context, taking into account broader structural conditions that could explain the degree of polarization on social media.

First, patterns of political communication can be related to the nature of the political system (van Vliet et al., 2020), as the multiplicity of parties might result in different messaging strategies unlike political discussions taking place in a bipartisan system. Some argue that the presence of multiple political parties can lead to increased polarization, as parties adopt non-centrist positions in order to differentiate themselves and thus to appeal to specific voter segments (Indridason, 2008). Focusing on the European context, some research shows high levels of polarization among voters in European multiparty political systems, as partisans are often extremely hostile towards competing parties (Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila, 2021). This is especially noticeable in Central Eastern and Southern Europe, where the degree of polarization is notably higher than it is in the U.S., while Northern European countries are more moderate in terms of partisan feelings (Reiljan, 2020). Finding strong polarization patterns in the Slovenian social media environment would constitute additional evidence for this argument. 14 political parties and movements officially participated in the 2019 European Elections in Slovenia, with their candidates competing for a total of 8 seats in the European Parliament.

Second, characteristics of media systems can impact the nature of the public discourse on social media. According to Hallin and Mancini’s framework, media systems in Central and Eastern Europe exhibit characteristics of the Polarized Pluralist model, marked by a high degree of political parallelism, where media outlets align with specific political parties or ideologies (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). Studies examining media systems in Central and Eastern Europe, including Slovenia, suggest that the region may not conform to a single type of media system (Herrero et al., 2017), and that there are specific national legacies that lead to unique developments in each country’s media system (Miconi and Papathanassopoulos, 2023). The Slovenian media system may be characterized by a lot of media fragmentation along political lines (Herrero et al., 2017), and strong links among media owners, political elites and economic investors (Örnebring, 2012).

Third, social media use can further contribute to polarization through mechanisms like algorithmic filtering and selective exposure to ideologically congruent content (Van Bavel et al., 2021), as discussed above. In Slovenia, social media use is relatively high (Eurostat, 2022), being slightly above the EU average and comparable to the U.S., while Twitter remains among the most popular platforms used to discuss politics online (Valicon, 2020).

These factors might lead to the conclusion that the degree of polarization in Eastern European countries, including Slovenia, could be higher compared to Western democracies; however, the relationship between polarization and political and media systems is complex and context-dependent. Analyzing the case of Slovenia is useful for a better understanding of social media polarization in a multiparty political setting and a fragmented media system.

3 Methodology

We rely on social network analysis (SNA) to examine the structure of online political discussion on Twitter. Our dataset consists of a total of 40,670 tweets, posted by 2845 unique users. Data was collected in the period of 30 days before the election via Twitter Streaming API, using a set of 15 election-related hashtags and keywords: these were the 10 most commonly used hashtags marking the European Election campaign and 5 different grammatical variations of the word “election” in Slovenian language. Data analysis was performed with Python programming language (version 3.5.6.) using TSM module (Freelon, 2018); with network visualizations done in Gephi (version 0.9.2.) using ForceAtlas2 algorithm (Jacomy et al., 2014).

We observe the flow of communication with the retweet network, as a retweet is the primary affordance through which the information is shared between users on Twitter (Firdaus et al., 2018). To examine the degree of fragmentation, we use the Louvain community detection method (Dugué and Perez, 2022). In addition to quantitative SNA measures, we also examine the five biggest communities by looking at their top users and hashtags, which helps us determine the main characteristics of each community and label them according to the prevailing political sentiment. Several different topologies have been used for categorizing social media users. Following the example of Bracciale et. al (2018), we extracted from these topologies 7 categories that represent users’ roles in the political discussion: ‘Media/Journalists’, ‘Politicians/Political parties’, ‘Institutions’, ‘Political supporters’, ‘Citizens’, ‘Commentators’ and ‘Organizations’.

To answer RQ1, we use a number of SNA measures that highlight the level of fragmentation between groups of users. Modularity and clustering coefficient are basic measures to find groups in the network. High modularity indicates dense connections between nodes within communities and sparse connections between nodes in different communities. Similarly, clustering coefficient tells us the degree to which nodes in the network tend to cluster together. Next, we analyze information flows within and among communities by using the E-I index to look at the amount of homophilic and heterophilic interactions (Krackhardt and Stern, 1988). The measure provides a normalized comparison of the number of interactions within a community (internal or homophilic) with the number of interactions between one’s own community and outside communities (external or heterophilic). Finally, we observe how different communities relate to one another by examining ties between each possible pair of a multitude of communities and directions. We use proximity matrix (Freelon, 2018), where proximity between communities A and B is defined as the proportion of shared ties between A and B of all the ties involving at least one member of A. Resulting matrix tells us how close each community is to each other. The closer the two communities are, the more content is able to flow between them and the less they resemble a filter bubble. It is a “relational measure that captures the specific relationships between different clusters rather than only measuring the coherence of a single cluster” (Lynch et al., 2017, p. 10).

To answer RQ2, we need to identify users that are able to facilitate communication between different clusters and bridge the ideological divide. Identification of such users is not straightforward, as one needs to consider both the intermediary capacity as well as influence of the node. Most studies use betweenness centrality as the measure for identifying broker positions, however, this measure does not take into account the polarized community structure of the network. As pointed out by Freelon, in polarized online networks, “what matters is often less the absolute number of nodes a given node connects and more the specific subgraphs a node connects” (Freelon, 2018, p. 7). The criteria for the identification of influential bridges are two-fold: (1) such users should have a high in-degree (meaning that they are often retweeted by other users), and (2) a notable proportion of their incoming ties should come from one or more communities other than their own (meaning that they are being retweeted by members of other communities). Nodes meeting both criteria lie near the borders of different communities, serving as a point of connection between them (Freelon, 2018).

To answer RQ3, we use SNA measures to define influential users, namely indegree, outdegree, eigenvector centrality and betweenness centrality. In the context of the retweet network, users with highest indegree are users that are most often retweeted – which is seen as an indicator of relevancy (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014). Outdegree reveals users that are retweeting the most and is an indicator of activity. The measure is connected to the concept of superparticipants (Graham and Wright, 2014), users that are the most active in disseminating content and may have the power to shape online discussions. We use eigenvector centrality as a measure that quantifies importance of a node in the network. Its score is higher when node’s connections are in turn highly connected, thus the measure is suitable for finding opinion leaders (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014). Lastly, betweenness centrality tells us how often a certain node is positioned on a path between two other nodes (Freeman, 1977). Users with high betweenness centrality can help establish connections among nodes that are not otherwise connected, thus the measure can help identify users that play a gatekeeper role (Ghajar-Khosravi and Chignell, 2017).

4 Results

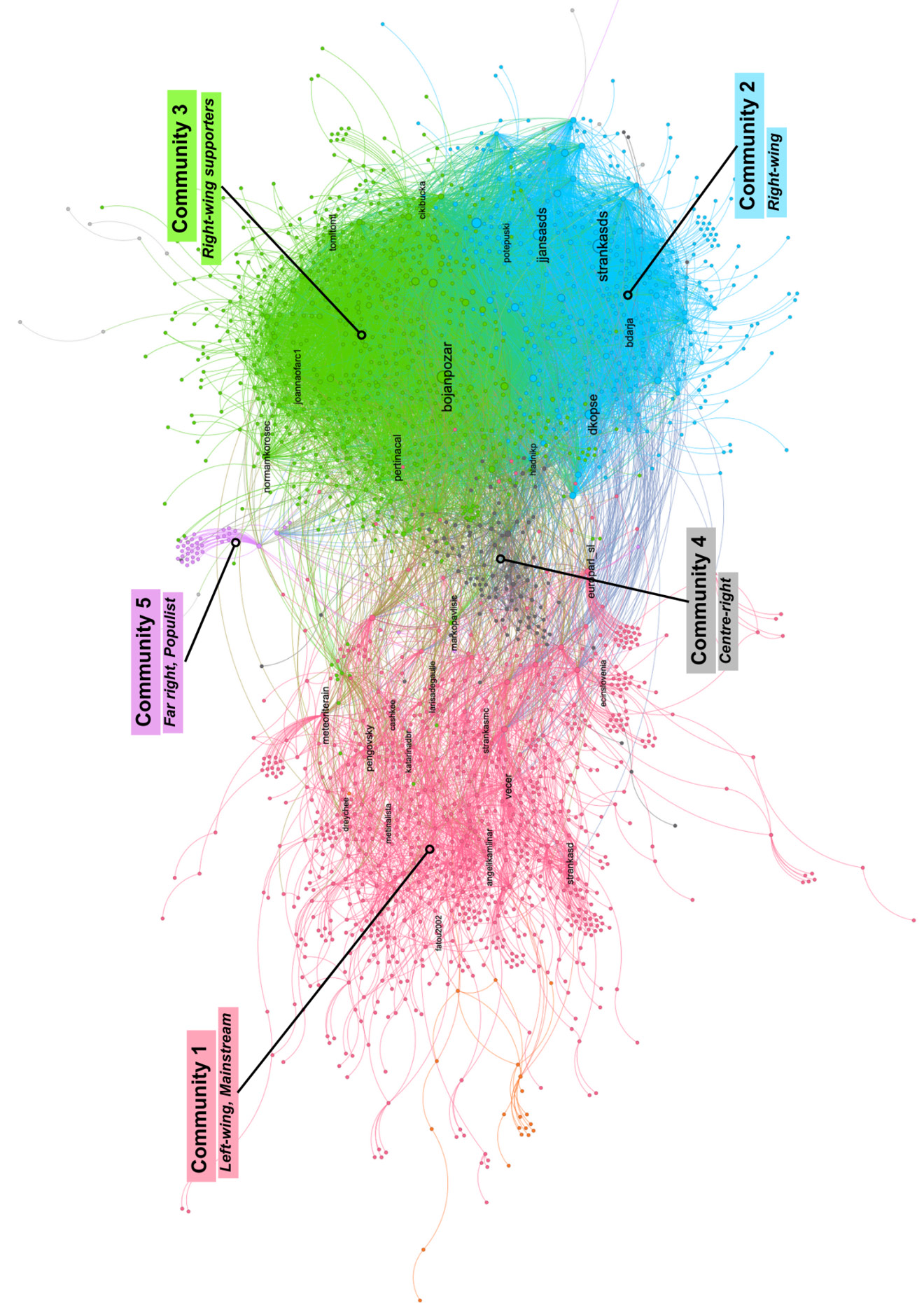

To examine communication flows, a total of 27,561 retweets were mapped into a retweet network consisting of nodes (users) and 14,483 unique edges (retweets). Observed network has an average path length of 5.515 and an average clustering coefficient of 0.103. A random network of the same size following Erdős–Rényi model (Erdős and Rényi, 1960) would consist of 13,927 edges, have an average path length of 4.313 and an average clustering coefficient of 0.003. Compared to a random graph, the Slovenian retweet network has similar shortest path length, but a higher clustering coefficient. Average path length is within the expected range for social media networks, while a higher clustering coefficient suggests the presence of clusters, each of which has dense connections within. Modularity (Q = 0.426) is relatively high (Newman and Girvan, 2003), which further confirms fragmentation of the network. We identified 49 distinct communities in the observed network, out of which we closely examined the five biggest ones (together representing 92 % of all users and 98 % of all retweets). Network visualization can be seen in Figure 1.

Observed communities differ in size, intensity of communication, shared content and dominant ideological views.

Community 1 consists of 39 % of all users and is the biggest community in the network. Its most prominent members are mainstream media accounts, state institutions and liberal or left/centre-left parties and politicians, including parties that formed a government coalition at the time; namely Lista Marjana Šarca (LMŠ, Renew), Social Democrats (SD, S & D) and the Left (Levica, European Left). We label this cluster “Left-wing, Mainstream”.

Community 2 consists of 18 % of all users. Among the most prominent members are politicians and official accounts of the right-wing Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS, EPP), the biggest opposition party at the time of data collection. We label this cluster “Right-wing”.

Community 3 consists of 26 % of all users. Among the most prominent members are right-wing politicians, opinion leaders and partisan media outlets, as well as content sympathizing with the opposition Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS, EPP). We mark this cluster “Right-wing supporters”.

Community 4 consists of 6 % of all users. The most prominent members include politicians from the center-right Christian Democrats (NSi, EPP) as well as journalists. We label this cluster “Center-right”.

Community 5 consists of 3 % of all users and therefore is the smallest community analyzed. It features far-right content and politicians (Alt-right, identitarian and populist accounts), as well as a group of foreign, likely astroturf profiles. We mark the label cluster as “Far right, Populist”.

Retweet network. Dots represent users, lines represent retweets, colors represent communities.

Krackhardt’s E-I index, five biggest communities.

|

Community |

E-I index |

|

1 – Left-wing, Mainstream |

- .684 |

|

2 – Right-wing |

- .429 |

|

3 – Right-wing supporters |

- .140 |

|

4 – Center-right |

.096 |

|

5 – Far right, Populist |

.441 |

We then calculated E-I index for each community to see whether retweets stay within communities or spread outside their borders. The three biggest communities (representing 84 % of all users) have a negative E-I index, which means that most of the retweets stay within their own community. This shows that communication happens largely within like-minded circles as users tend to predominantly share content posted by members of the same community. Nevertheless, all five of the biggest communities maintain at least some ties with other clusters, meaning that users are not entirely isolated from receiving information originating from other parts of the network. Observed communication patterns hint at fragmentation and polarization, but not isolation.

A look at the proximity matrix (Table 2) reveals which communities share information. Each cell depicts a share of ties involving the community mentioned in the row that are shared with the community mentioned in the column, divided by all ties involving the community mentioned in the row. Diagonal cells represent a share of internal connections. Reciprocal off-diagonal cells (e.g., 0–1 and 1–0) share the same numerators, however, their values vary significantly, because denominators are almost always distinct. Since we are observing retweets, the proximity matrix shows us that some communities tend to rebroadcast content from certain communities rather than others. The matrix reveals that Community 1 (mainstream, left-wing) has a low number of connections with other parts of the network, while Communities 2 and 3 (both right-wing) share a relatively large number of retweets among them. Numerous ties between these two communities are also seen in the network visualization, where both communities appear close together on the right side of the network.

Proximity matrix for the connections among the five biggest communities.

|

Community |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1 |

0.842 |

0.055 |

0.073 |

0.024 |

0.006 |

|

2 |

0.015 |

0.715 |

0.248 |

0.017 |

0.005 |

|

3 |

0.029 |

0.364 |

0.57 |

0.027 |

0.01 |

|

4 |

0.086 |

0.219 |

0.236 |

0.452 |

0.007 |

|

5 |

0.082 |

0.253 |

0.355 |

0.03 |

0.28 |

In RQ2 we look at bridges, that is nodes that receive large numbers of ties from multiple communities. Table 3 presents the ten most prominent bridges in the network. The second column lists the categorization of the user, the third column lists their in-degree, the fourth column lists communities to which each user is connected (descending by number of ties), the fifth column lists the number of these connections, and the last column depicts the ratio of the tie count of the user’s second most-connected community to that of his own community. The extended table including user names can be found in Appendix B.

Ten most prominent bridges.

|

Rank |

Type of account |

Indegree |

Communities |

Ties |

Ratio of 2nd community ties to 1st community ties |

|

1 |

Political supporter |

543 |

2 3 1 5 4 |

296 236 4 4 3 |

80 % |

|

2 |

Citizen |

364 |

3 2 4 1 |

230 123 9 2 |

53 % |

|

3 |

Commentator; Political supporter |

284 |

2 3 4 1 5 |

166 91 22 3 2 |

55 % |

|

4 |

Citizen |

165 |

2 3 5 4 |

104 58 2 1 |

56 % |

|

5 |

Commentator |

159 |

3 2 1 4 |

97 58 2 2 |

60 % |

|

6 |

Political supporter |

143 |

3 2 4 1 |

89 49 4 1 |

55 % |

|

7 |

Political supporter |

143 |

3 2 4 5 |

83 52 6 2 |

63 % |

|

8 |

Journalist; Commentator |

118 |

2 3 4 1 |

66 49 3 1 |

74 % |

|

9 |

Political supporter |

104 |

2 3 |

54 50 |

93 % |

|

10 |

Citizen |

104 |

1 3 2 4 |

52 34 11 7 |

65 % |

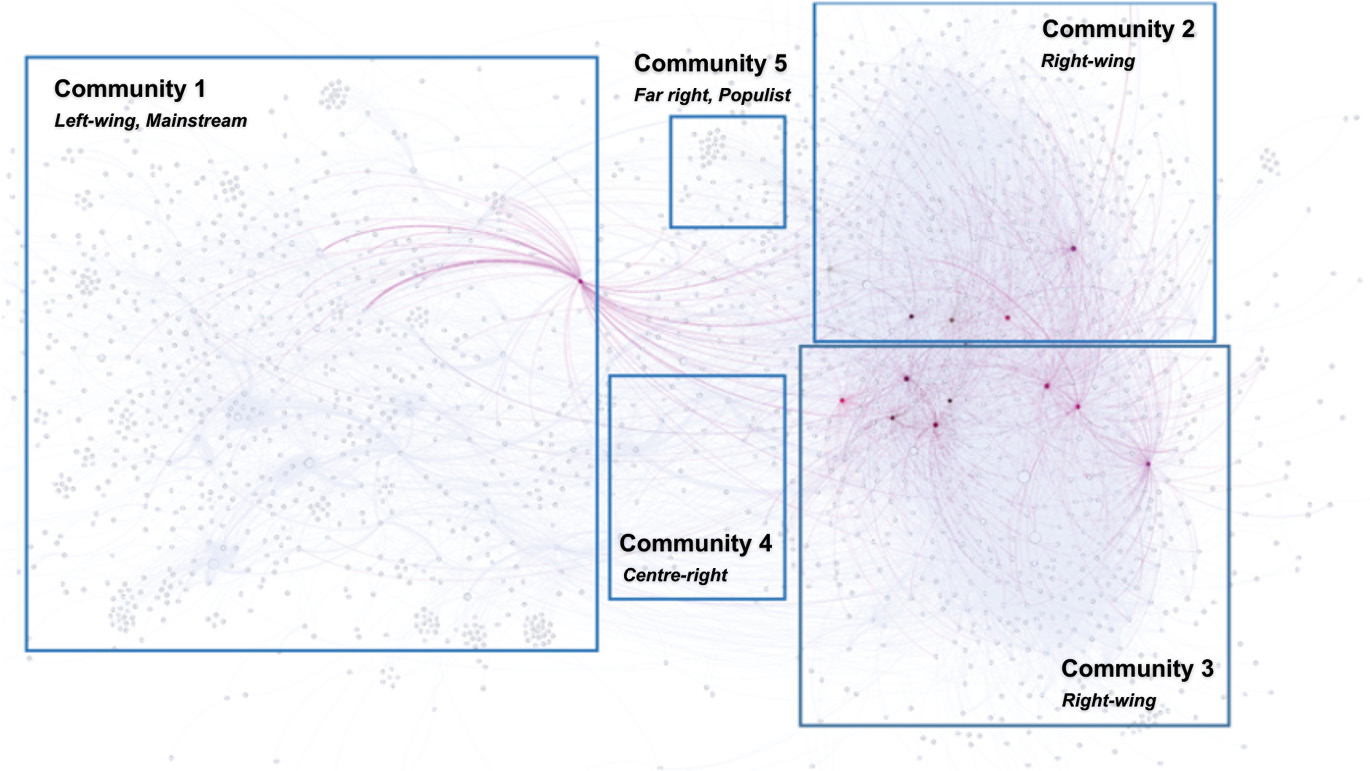

Bridges detected by this method are a diverse mix of commentators, partisan supporters and active citizens. Nearly all of them are members of the two big right-wing communities, and they (with the exemption of number 10[2]) did not help to bridge content across the ideological divide. Instead, identified bridges facilitate information flow between ideologically similar communities (2 and 3); thereby linking different parts of a broader right-wing area of the network. This is clearly seen in the network visualization, where the bridges identified and their ties are highlighted (Figure 2): except one, all prominent bridges lie at the borders of ideologically similar Communities 2 and 3, facilitating exchange of information between them.

Prominent bridges and their connections (highlighted) in the retweet network. Rectangles mark communities.

In RQ3 we examine what roles politicians play in polarized discussions on social media. We identify central users in the network, map them with community structure, and examine their communication patterns. The results show that political accounts play various roles in online discussions – most often as opinion leaders and gatekeepers, but rarely as most active users. When we consider communities to which these influential accounts belong, notable differences arise. The vast majority of the most active and most influential users in the network belong to right-wing Communities 2 and 3. This shows that members of the right-wing communities are more active, and their central accounts in turn receive considerably more attention and influence than central accounts from other communities (see Appendix A for the list of most influential users according to different centrality measures across five observed communities). The visibility of politicians within their communities varies greatly across the network. In the right-wing clusters, politicians dominate the discussion – while in the center-left part of the network, politicians do not hold central roles. The difference is most notable when comparing Communities 1 (left-wing, mainstream) and 2 (right-wing). As shown in Table 3, influential users in Community 1 are mainly media, commentators and institutions, while political accounts rarely make the list (despite the fact that all major political parties from the center-left and liberal spectre belong to this community) – hinting that politicians in this cluster struggle to set the agenda of the discussion. On the other hand, politicians and party accounts belonging to right-wing SDS party dominate discussion in Community 2, as they consistently score among the most influential accounts (Table 5). Extended tables with included usernames can be found in Appendix A.

Influential users, Community 1.

|

Community 1 (left-wing, mainstream) |

|||||

|

Indegree (relevancy) |

Eigenvector centrality (opinion leaders) |

Betweenness centrality (gatekeepers) |

|||

|

Rank |

Type of account |

Rank |

Type of account |

Rank |

Type of account |

|

1 |

Institution |

1 |

Media |

1 |

Political party |

|

2 |

Media |

2 |

Institution |

2 |

Media |

|

3 |

Citizen |

3 |

Media |

3 |

Citizen |

|

4 |

Media |

4 |

Institution |

4 |

Commentator |

|

5 |

Institution |

5 |

Institution |

5 |

Media |

|

6 |

Institution |

6 |

Institution |

6 |

Politician |

|

7 |

Institution |

7 |

Organisation |

7 |

Citizen |

|

8 |

Citizen |

8 |

Organisation |

8 |

Institution |

|

9 |

Commentator |

9 |

Organisation |

9 |

Citizen |

|

10 |

Political party |

10 |

Media |

10 |

Political party |

Influential users, Community 2.

|

Community 2 (right-wing) |

|||||

|

Indegree (relevancy) |

Eigenvector centrality (opinion leaders) |

Betweenness centrality (gatekeepers) |

|||

|

Rank |

Type of account |

Rank |

Type of account |

Rank |

Type of account |

|

1 |

Political party |

1 |

Political party |

1 |

Politician |

|

2 |

Politician |

2 |

Politician |

2 |

Political party |

|

3 |

Politician |

3 |

Politician |

3 |

Political supporter |

|

4 |

Political supporter |

4 |

Politician |

4 |

Politician |

|

5 |

Citizen |

5 |

Political supporter |

5 |

Political supporter |

|

6 |

Journalist; Political supporter |

6 |

Citizen |

6 |

Political supporter |

|

7 |

Political supporter |

7 |

Citizen |

7 |

Political supporter |

|

8 |

Journalist; Political supporter |

8 |

Citizen |

8 |

Politician |

|

9 |

Politician |

9 |

Political supporter |

9 |

Political supporter |

|

10 |

Politician |

10 |

Politician |

10 |

Citizen |

5 Discussion

Communication patterns of Twitter users involved in a political discussion reveal communities of users with different political views emerging from the topological structure of the networks. The ideologically left-leaning part of the network consists of one big but sparsely connected community, while the tightly connected right-leaning part consists of ideologically similar conservative communities. Both parts of the network have roughly equal numbers of users, however, members of the right-wing clusters are disproportionally more active. On average, users belonging to right-wing communities are also able to transmit information to a larger audience than users belonging to left-leaning part of the network.

Results show that both right and left-leaning parts of the network tend to share information coming from ideologically congruent sources and that information hardly spreads between communities with different views. However, all communities observed maintain at least some ties with other clusters, which suggests that they are not completely isolated from encountering opposing views. Observed communication patterns confirm high communicative fragmentation and ideological polarization, but not isolation, as proposed by the filter bubble hypothesis (Pariser, 2011). Interestingly, this relates to empirical findings by Williams (2015), who analyzed Twitter discourse on climate change and found both open forums as well as entrenched homogenous communities of users engaging in negative discourse with the opposing side. Results are also in line with Törnberg et al. (2021), who see social media as polarizing not by enabling users to completely avoid opposing views, but by providing spaces for conflictual interaction. Even if social media users do encounter opposing views, worries about the consequences of like-minded communities remain, as pro-attitudinal exposure has been shown to foster polarization and increase hostility towards users with different views (Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021). Following these arguments, we want to avoid simplistic and techno-determinist understanding of filter bubbles as completely sealed-off communicative environments (e.g. Pariser, 2011; Sunstein, 2017). Nevertheless, empirical results show that while not completely isolated, homogeneous communities of like-minded users do form on Twitter, and provide further evidence for fragmentation of what was once perceived as the public sphere into a multitude of highly polarized, more or less overlapping public spaces, as predicted by Bruns (2023).

The results are partially in line with some authors who see the online environment as a sphere of interest driven communities, linked with intermediaries – users who act as bridges and facilitate communication flows between different groups (Bruns and Highfield, 2016). Bridges hold a key role in fostering exchange of opinions and enable what some see as a “complex system of distinct and diverse, yet inter-connected and overlapping publics” (Bruns and Highfield, 2016, p. 127). The results obtained by analyzing Slovenian Twitter users diverge from this thesis. We show that bridges between communities exist, however, prominent intermediaries are only bridging ideologically similar communities. From a theoretical perspective identifying bridges could well reveal users who are able to bring ideologically opposed communities together by promoting shared experiences and presenting common ground for cross-cutting debate. However, these results indicate the opposite – bridges, while present, do not foster a cross-cutting exchange of views, but help to establish communication flows among already connected and ideologically similar communities. In this case, prominent bridges simultaneously promote cohesion between similar communities as well as polarization of different ones, thereby contributing to deepening, not reducing, fragmentation of the network. These results encourage us to rethink not only what influence certain users have on the spread of information in the network, but also to reconsider some of the methodological approaches used for identifying and examining influential bridges. While basic measures from the SNA toolkit (such as betweenness centrality) could be used to easily identify nodes that act as links between different groups of users, more nuanced analysis is needed to interpret the results and confirm whether such users actually perform the roles of information brokers between ideologically different communities, thereby enabling cross-cutting information flows and reducing the effect of filter bubbles. The empirical approach used in this paper presents a potentially more robust measure for identifying influential brokers in polarized online networks.

Looking at central users across different communities, we find that the left-leaning part of the network shares content coming from a diverse mix of institutions and mainstream media outlets, while right-wing clusters seem to predominantly amplify content posted by politicians. Right-wing politicians are among the most prominent users in the network, and are able to dominate the discussion within their communities – they receive more attention and are more influential compared to politicians coming from the left-leaning part of the network. These politicians generally hold a considerable influence over content diffusion, albeit their influence remains limited to ideologically similar communities, while they do not facilitate communication across different clusters or attract sympathies of the wider network. This shows that some politicians, especially those belonging to right-wing communities, are using the fragmented social media environment in order to effectively spread their partisan messages among selected target groups and to mobilize their supporters. Politicians can gain visibility and rally support by sharing information that is ideologically aligned with the positions of their community and lands well with community members (Marwick and Lewis, 2017). While this study does not engage in qualitative analysis of messages posted, it shows that right-wing politicians are able to attract attention and visibility among their followers significantly better than left-wing politicians. The observations from this study are in line with global communication trends among conservative parties, which are moving away from the center and strategically using partisan discourse to attract attention, mobilize their supporters and engage with communities who hold more fringe and controversial views (Ceia, 2020; Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021), further increasing political polarization (Tucker et al., 2018).

The analysis revealed another interesting observation, namely that the mainstream media accounts are clustered within the same community as the government parties. The finding might suggest that the mainstream media are ideologically aligned with the left-wing government. Media alignment might be explained by the Slovenian political context, in which ruling coalitions most of the time have been formed by left-wing parties, giving them the opportunity to develop closer ties with the mainstream media. On the other hand, a network of alternative media outlets has emerged around right-wing political parties. While these partisan outlets are influential in the right-wing communities, their content does not appear to be shared across the ideological divide. Similar findings have been observed in other political contexts. Based on the use of social media by Spanish political actors, Ceia (2020) noted that parties frequently share links to content coming from a homophilic set of sources, which allows them to interpret events through their own frames. This finding empirically confirms the link between social media polarization and the polarization of the media system. Social media contributes to political polarization by creating communities of like-minded users, limiting exposure to diverse viewpoints, and reinforcing ideologically congruent media consumption. This polarization is further amplified by the role of political elites and partisan media, creating a complex interplay between social media dynamics and the broader political and media system (Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021). This is in line with the observations made within the American context by Wilson et al. (2020), who find that social media, political elites and partisan media collectively contribute to rising polarization and can create a self-perpetuating cycle of animosity and ideological division.

The study focuses on an underreached context of political communication in Central and Eastern Europe, namely Slovenia. There are structural reasons to believe that patterns of polarization on social media, observed mainly in the context of the U.S. (Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021), might differ in a different political (multiparty democracy, proportional voting system, coalition governments) and media system (significant media fragmentation along political lines). Nevertheless, empirical observations from Slovenia confirm similar patterns of ideological fragmentation compared to other Western democracies, thus providing further evidence that polarization in political discourse on social media is a prominent feature of the contemporary communication environment, present across various national contexts as well as different political and media systems.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study focuses on one social media platform in a specific context (pre-election period). We cannot generalize such studies to be representative of the national or global context – where social media is only one pillar in an increasingly connected hybrid media system in which political debate unfolds. Nevertheless, similar limitations apply to any case study of communication on social media. If we are to understand the characteristics of the contemporary communication environment, we need to first understand what is happening on individual platforms in a variety of specific contexts, as these platforms are becoming increasingly important arenas for political communication. Second, tools offered by SNA can uncover various communication patterns, however, many point out that the quantitative approach cannot sufficiently describe complex social phenomena. A more detailed study of interactions involving qualitative analysis of shared messages, images, videos and URLs would help to further illuminate the nature of online polarization. Lasty, the state of polarization on social media is far from fixed – new platforms that arise and become adapted for public communication can bring new discursive practices and interaction patterns.

6 Conclusion

Political communication on social media is often described as increasingly fragmented and polarized, with users forming closed communities of likeminded peers (so-called filter bubbles). The phenomenon has received broad academic attention, however, open questions about its extent in different contexts remain. We contribute to this debate by studying the structure of political discussion on social media in Slovenia, drawing on computational methods that go beyond the usual social network analysis toolkit. In line with similar studies, we find that political discussion among Slovenian Twitter users is highly fragmented and divided into distinct, ideologically homogeneous communities. Right-wing and left-wing parts of the network are roughly equal in size, however, right-wing clusters are considerably more active. The analysis of communication patterns and central users suggests that users tend to share messages from like-minded peers, and that communication between ideologically different communities is rare. At the same time, links between different parts of the network exist, thus rejecting the idea of isolated information spaces known as filter bubbles and empirically confirming the thesis about online environments increasingly fragmenting into a multitude of overlapping publics with rising polarization and disagreements between ideologically opposing groups. Second, we find that bridges – prominent users who foster connections between different communities – are present in the network, however, they predominantly enable information flows only among ideologically similar communities. The intermediaries who would facilitate an exchange of views among ideologically opposing communities are almost non-existent, which further confirms warnings about the dissolution of the networked public sphere into separate, unconnected groups of users with similar worldviews. Influential bridges identified in this study are thus contributing to deepening, not reducing, fragmentation of the network, which prompts us to rethink how we identify and examine users holding broker roles in the network. Third, we find that right-wing politicians are among the most prominent users in the network and are able to dominate the discourse within their communities – which cannot be said for left-wing politicians. This shows that right-wing politicians effectively use Twitter as a strategic communication tool to engage with their supporters, spread their partisan messages and make use of the polarized social media environment. The study provides quantitative evidence of the extent of polarization in a networked public sphere, and adds a comparative perspective by evaluating global communication trends in the context of a small, European multi-party democracy, where such topics have not been extensively studied before. The results provide further evidence that polarization in political discourse on social media is a prominent feature of the contemporary communication environment, present across various political and media systems.

About the author

independent researcher

References

Aral, S. (2020). The hype machine: How social media disrupts our elections, our economy, and our health – and how we must adapt. Currency.Search in Google Scholar

Arguedas, A. R., Robertson, C. T., Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarisation: A literature review. Digital News Project – Reuters Institute. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-01/Echo_Chambers_Filter_Bubbles_and_Polarisation_A_Literature_Review.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Barberá, P. (2014, September 3–6). How social media reduces mass political polarization. Evidence from Germany, Spain, and the US [Paper presentation]. American Political Science Association Annual Meeting 2015, San Francisco, CA, United States. http://pablobarbera.com/static/barbera_polarization_APSA.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., & Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science, 26(10), 1531–1542. https://doi.org/10.1177/095679761559462010.1177/0956797615594620Search in Google Scholar

Bastos, M., Mercea, D., & Baronchelli, A. (2018). The geographic embedding of online echo chambers: Evidence from the Brexit campaign. PLoS ONE, 13(11), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.020684110.1371/journal.pone.0206841Search in Google Scholar

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., Roberts, H., & Zuckerman, E. (2017). Breitbart-led right-wing media ecosystem altered broader media agenda. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/analysis/breitbart-media-trump-harvard-study.phpSearch in Google Scholar

Borgesius, Z., Trilling, D., Möller, J., Bodó, B., de Vreese, C. H., & Helberger, N. (2016). Should we worry about filter bubbles? Internet Policy Review, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2016.1.40110.14763/2016.1.401Search in Google Scholar

Bracciale, R., Martella, A., & Visentin, C. (2018). From super-participants to super-echoed: participation in the 2018 Italian electoral twittersphere. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 11(2), 361–393. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v11i2p361Search in Google Scholar

Bright, J., Marchal, N., Ganesh, B., & Rudinac, S. (2020). Echo chambers exist! (But they’re full of opposing views). ArXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2001.11461Search in Google Scholar

Bruns, A. (2017). Echo chamber? What echo chamber? Reviewing the evidence. 6th Biennial Future of Journalism Conference, UK, 0–11.10.64628/AA.t5x9eq6ueSearch in Google Scholar

Bruns, A. (2019). Are filter bubbles real?. Polity Press.10.14763/2019.4.1426Search in Google Scholar

Bruns, A. (2023). From “the” public sphere to a network of publics: Towards an empirically founded model of contemporary public communication spaces. Communication Theory, 33(2–3), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/CT/QTAD00710.1093/ct/qtad007Search in Google Scholar

Bruns, A., & Highfield, T. (2016). Is Habermas on Twitter? Social media and the public sphere. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 98–130). Routledge.10.4324/9781315716299Search in Google Scholar

Carpentier, N. (2017). The discursive-material knot. Peter Lang Publishing. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4331-3754-910.3726/978-1-4331-3754-9Search in Google Scholar

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2021). Influencers in the political conversation on Twitter: Identifying digital authority with big data. Sustainability, 13(5), 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU1305285110.3390/su13052851Search in Google Scholar

Casero-Ripollés, A., Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Marcos-García, S. (2021). The influence of political actors in the digital public debate on Twitter about the negotiations for the formation of the government in Spain. American Behavioral Scientist, 66(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221100315910.1177/00027642211003159Search in Google Scholar

Ceia, V. (2020). Digital ecosystems of ideology: Linked media as rhetoric in Spanish political tweets. Social Media and Society, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/205630512092663010.1177/2056305120926630Search in Google Scholar

Cota, W., Ferreira, S. C., Pastor-Satorras, R., & Starnini, M. (2019). Quantifying echo chamber effects in information spreading over political communication networks. EPJ Data Science, 8(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-019-0213-910.1140/epjds/s13688-019-0213-9Search in Google Scholar

Dehghan, E. (2020). Networked discursive alliances: Antagonism, agonism, and the dynamics of discursive struggles in the Australian Twittersphere [Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology]. QUT ePrints. https://doi.org/10.5204/thesis.eprints.17460410.5204/thesis.eprints.174604Search in Google Scholar

Diani, M. (2003). “Leaders” Or Brokers? Positions and Influence in Social Movement Networks. In M. Diani & D. McAdam (Eds.), Social Movements and Networks: Relational Approaches to Collective Action (pp. 105–122). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199251789.003.000510.1093/0199251789.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Dubois, E., & Blank, G. (2018). The echo chamber is overstated: The moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Information Communication and Society, 21(5), 729–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.142865610.1080/1369118X.2018.1428656Search in Google Scholar

Dubois, E., & Gaffney, D. (2014). The multiple facets of influence: Identifying political influentials and opinion leaders on Twitter. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(10), 1260–1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276421452708810.1177/0002764214527088Search in Google Scholar

Dugué, N., & Perez, A. (2022). Direction matters in complex networks: A theoretical and applied study for greedy modularity optimization. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 603, 127798. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSA.2022.12779810.1016/j.physa.2022.127798Search in Google Scholar

Erdös, P. and Rényi, A. (1960). On the Evolution of Random Graphs. Publication of the Mathematical Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 5(1), 17–61.Search in Google Scholar

Esteve Del Valle, M., & Borge Bravo, R. (2018). Leaders or brokers? Potential influencers in online parliamentary networks. Policy & Internet, 10(1), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/POI3.15010.1002/poi3.150Search in Google Scholar

Esteve Del Valle, M., Broersma, M., & Ponsioen, A. (2022). Political interaction beyond party lines: communication ties and party polarization in parliamentary Twitter networks. Social Science Computer Review, 40(3), 736–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443932098756910.1177/0894439320987569Search in Google Scholar

Eurostat. (2022). Individuals – internet activities (ISOC_CI_AC_I). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_CI_AC_I__custom_8570330/default/table?lang=en&page=time:2020Search in Google Scholar

Firdaus, S. N., Ding, C., & Sadeghian, A. (2018). Retweet: A popular information diffusion mechanism – A survey paper. Online Social Networks and Media, 6, 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OSNEM.2018.04.00110.1016/j.osnem.2018.04.001Search in Google Scholar

Freelon, D. (2018). Partition-specific network analysis of digital trace data. In B. F. Welles, S. González-Bailón (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Networked Communication (pp. 1–27). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190460518.013.310.1093/oxfordhb/9780190460518.013.3Search in Google Scholar

Freeman, L. C. (1977). A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry, 40(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/303354310.2307/3033543Search in Google Scholar

Garimella, K., De Francisci Morales, G., Gionis, A., & Mathioudakis, M. (2018). Political discourse on social media: Echo chambers, gatekeepers, and the price of bipartisanship. Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web, France, 913–922. https://doi.org/10.1145/3178876.318613910.1145/3178876.3186139Search in Google Scholar

Ghajar-Khosravi, S., & Chignell, M. (2017). Pragmatics of network centrality. In L. Sloan, & A. Quan-Haase (Eds.), The Sage handbook of social media research methods (pp. 309–327). Sage Publications Ltd.10.4135/9781473983847.n19Search in Google Scholar

Graham, T., & Wright, S. (2014). Discursive equality and everyday talk online: the impact of “superparticipants”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.1201610.1111/jcc4.12016Search in Google Scholar

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO978051179086710.1017/CBO9780511790867Search in Google Scholar

Herrero, L., Humprecht, E., Engesser, S., Brüggemann, M., & Büchel, F. (2017). Rethinking Hallin and Mancini beyond the west: An analysis of media systems in Central and Eastern Europe. International Journal of Communication, 11, 4797–4823. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6035/2196Search in Google Scholar

Hong, S., & Kim, S. H. (2016). Political polarization on twitter: Implications for the use of social media in digital governments. Government Information Quarterly, 33(4), 777–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GIQ.2016.04.00710.1016/j.giq.2016.04.007Search in Google Scholar

Indridason, I. H. (2008). Multiparty democracy: Elections and legislative politics. Perspectives on Politics, 6(1), 195–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759270808041910.1017/S1537592708080419Search in Google Scholar

Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S., & Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS ONE, 9(6), e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.009867910.1371/journal.pone.0098679Search in Google Scholar

Jungherr, A., Rivero, G., & Gayo-Avello, D. (2020). Retooling politics. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/978110829782010.1017/9781108297820Search in Google Scholar

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344371664315710.1177/0163443716643157Search in Google Scholar

Kekkonen, A., & Ylä-Anttila, T. (2021). Affective blocs: Understanding affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 72, 102367. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ELECTSTUD.2021.10236710.1016/j.electstud.2021.102367Search in Google Scholar

Kinkead, D., & Douglas, D. M. (2020). The network and the demos: Big data and the epistemic justifications of democracy. In K. Macnish & J. Galliott (Eds.), Big data and democracy (pp. 119–134). Edinburgh University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/big-data-and-democracy/network-and-the-demos-big-data-and-the-epistemic-justifications-of-democracy/AA98E294F857F1EE3DC6B803E1957AAB10.3366/edinburgh/9781474463522.003.0009Search in Google Scholar

Krackhardt, D., & Stern, R. N. (1988). Informal networks and organizational crises: An experimental simulation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.2307/278683510.2307/2786835Search in Google Scholar

Kubin, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(3), 188–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.197607010.1080/23808985.2021.1976070Search in Google Scholar

Lasser, J., Aroyehun, S. T., Simchon, A., Carrella, F., Garcia, D., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Social media sharing by political elites: An asymmetric American exceptionalism. ArXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2207.06313Search in Google Scholar

Lynch, M., Freelon, D., & Aday, S. (2017). Online clustering, fear and uncertainty in Egypt’s transition. Democratization, 24(6), 1159–1177. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.128917910.1080/13510347.2017.1289179Search in Google Scholar

Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/output/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/Search in Google Scholar

Micó, J. L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2014). Political activism online: organization and media relations in the case of 15M in Spain. Information, Communication & Society, 17(7), 858–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.83063410.1080/1369118X.2013.830634Search in Google Scholar

Miconi, A., & Papathanassopoulos, S. (2023). On Western and Eastern media systems: Continuities and discontinuities. In: S. Papathanassopoulos & A. Miconi (Eds.), The Media Systems in Europe. (pp. 15–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32216-7_210.1007/978-3-031-32216-7_2Search in Google Scholar

Newman, M. E. J., & Girvan, M. (2003). Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Physical Review E – Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics, 69(2). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.69.02611310.1103/PhysRevE.69.026113Search in Google Scholar

Nguyen, C. T. (2020). Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Episteme, 17(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2018.3210.1017/epi.2018.32Search in Google Scholar

Orhan, Y. E. (2022). The relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding: comparative evidence. Democratization, 29(4), 714–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.200891210.1080/13510347.2021.2008912Search in Google Scholar

Örnebring, H. (2012). Clientelism, elites, and the media in Central and Eastern Europe. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 17(4), 497–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/194016121245432910.1177/1940161212454329Search in Google Scholar

Papacharissi, Z. (2016). The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society, 4(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444022222624410.1177/14614440222226244Search in Google Scholar

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin UK.10.3139/9783446431164Search in Google Scholar

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines’ (also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 376–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.1235110.1111/1475-6765.12351Search in Google Scholar

Soares, F. B., Recuero, R., & Zago, G. (2018). Influencers in polarized political networks on Twitter. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Social Media and Society, 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1145/3217804.321790910.1145/3217804.3217909Search in Google Scholar

Stromer-Galley, J. (2017). Political discussion and deliberation online. In K. Kenski, & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 837–851). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.013.015_update_00110.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.013.015_update_001Search in Google Scholar

Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 556–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01497.x10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01497.xSearch in Google Scholar

Sunstein, C. (2017). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400884711Search in Google Scholar

Törnberg, P., Andersson, C., Lindgren, K., & Banisch, S. (2021). Modeling the emergence of affective polarization in the social media society. PLOS ONE, 16(10), e0258259. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.025825910.1371/journal.pone.0258259Search in Google Scholar

Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: a review of the scientific literature. William & Flora Hewlett Foundation. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.314413910.2139/ssrn.3144139Search in Google Scholar

Valicon. (2020). Uporaba družbenih omrežij in storitev klepeta v Sloveniji 2018 – 2019 [Use of Social Networks and Chat Services in Slovenia 2018–2019]. https://www.valicon.net/sl/2020/01/uporaba-druzbenih-omrezij-in-storitev-klepeta-v-sloveniji-2018-2019Search in Google Scholar

Van Bavel, J. J., Rathje, S., Harris, E., Robertson, C., & Sternisko, A. (2021). How social media shapes polarization. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(11), 913–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.07.01310.1016/j.tics.2021.07.013Search in Google Scholar

van Dijk, J., & Hacker, K. L. (2018). Internet and democracy in the network society. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/978135111071610.4324/9781351110716Search in Google Scholar

van Vliet, L., Törnberg, P., & Uitermark, J. (2020). The Twitter parliamentarian database: Analyzing Twitter politics across 26 countries. PLoS ONE, 15(9 September), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.023707310.1371/journal.pone.0237073Search in Google Scholar

Williams, H. T. P., McMurray, J. R., Kurz, T., & Hugo Lambert, F. (2015). Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 32, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2015.03.00610.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, A. E., Parker, V., & Feinberg, M. (2020). Polarization in the contemporary political and media landscape. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COBEHA.2020.07.00510.1016/j.cobeha.2020.07.005Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Articles

- Mitigating product placement effects induced by repeated exposure: Testing the effects of existing textual disclosures in children’s movies on disclosure awareness

- Bonding over bashing: Discussing LGBTI topics in far-right alternative news media comments sections

- Framing of the war in Ukraine: How the international press reacted to the outbreak of the conflict

- Trustworthiness: Public reactions to COVID-19 crisis communication

- Power dynamics and the VillageTalk app: Rural mediatisation and the sense of belonging to the village community as communicative figuration

- From “minimalists” to “professional all-rounders”: Typologizing Swiss universities’ communication practices and structures

- Toward a neomodern epistemology of digital journalism

- The experience of social (in)visibility in narratives about ostracism

- Apocalypse now? – The Last Generation in digital capital’s affective ecology

- Media and policy legitimacy: A study of news coverage of the Flemish Human Rights Institute

- Is Fairyland for Everyone? Mapping online discourse on gender debates in Hungary

- Migration on digital news platforms: Using large-scale digital text analysis and time-series to estimate the effects of socioeconomic data on migration content

- Strategic polarization? Filter bubbles, bridges and the role of politicians on Twitter during 2019 European Election in Slovenia

- Mediated parent networks as communicative figurations: practical sense and communicative practices among parents in four European countries

- Authentic conflicts in post-Yugoslavia: A model of a post-war generation’s communication system

- The price of (un)regulation: Tracing the flow of political advertising budgets and voter targeting across online platforms in Romanian elections

- Book reviews

- Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., & Lovejoy, J. (2023). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research (5th ed.). Routledge. ix + 232 pp. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003288428

- Bonini, T., & Treré, E. (2024). Algorithms of resistance: The everyday fight against platform power. The MIT Press. 256 pp. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14329.001.0001

- Iskanderova, T. (2024). Unveiling semiotic codes of fake news and misinformation: Contemporary theories and practices for media professionals. Palgrave Macmillan. 87 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53751-6

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Articles

- Mitigating product placement effects induced by repeated exposure: Testing the effects of existing textual disclosures in children’s movies on disclosure awareness

- Bonding over bashing: Discussing LGBTI topics in far-right alternative news media comments sections

- Framing of the war in Ukraine: How the international press reacted to the outbreak of the conflict

- Trustworthiness: Public reactions to COVID-19 crisis communication

- Power dynamics and the VillageTalk app: Rural mediatisation and the sense of belonging to the village community as communicative figuration

- From “minimalists” to “professional all-rounders”: Typologizing Swiss universities’ communication practices and structures

- Toward a neomodern epistemology of digital journalism

- The experience of social (in)visibility in narratives about ostracism

- Apocalypse now? – The Last Generation in digital capital’s affective ecology

- Media and policy legitimacy: A study of news coverage of the Flemish Human Rights Institute

- Is Fairyland for Everyone? Mapping online discourse on gender debates in Hungary

- Migration on digital news platforms: Using large-scale digital text analysis and time-series to estimate the effects of socioeconomic data on migration content

- Strategic polarization? Filter bubbles, bridges and the role of politicians on Twitter during 2019 European Election in Slovenia

- Mediated parent networks as communicative figurations: practical sense and communicative practices among parents in four European countries

- Authentic conflicts in post-Yugoslavia: A model of a post-war generation’s communication system

- The price of (un)regulation: Tracing the flow of political advertising budgets and voter targeting across online platforms in Romanian elections

- Book reviews

- Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., & Lovejoy, J. (2023). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research (5th ed.). Routledge. ix + 232 pp. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003288428

- Bonini, T., & Treré, E. (2024). Algorithms of resistance: The everyday fight against platform power. The MIT Press. 256 pp. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14329.001.0001

- Iskanderova, T. (2024). Unveiling semiotic codes of fake news and misinformation: Contemporary theories and practices for media professionals. Palgrave Macmillan. 87 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53751-6