Abstract

Since the dawning of the new millennium, the unique properties and obscure behaviour exhibited by nanoparticles have captivated research scientists globally. Their versatility has led to an explosion of interest in nanoscience and recognition of its unlimited potential for innovation in modern society.

Engineered nanomaterials (ENM) are a class of deliberately designed and prepared materials with nanoscale dimensions that have a rapidly expanding range of applications in our every-day life, e.g. energy storage, food, cosmetics, sports, and textiles. However, there is now significant interest in more complex nanomaterials, which already have, or are expected to have, an important role as advanced drug delivery systems in nanomedicine, ultra-sensitive reporters in biomedical diagnostics, and as multifunctional probes in environmental management, as well as in advanced electronics, transport, information and communication technology, defense, and manufacturing. But in order to fully appreciate the extent of their potential, it is essential to have at least a rudimentary understanding of these tiny objects.

Nanotechnology—a fashionable trend in research for nearly two decades, but still with unclear terminology

Nanotechnology is a combination of science, engineering, and technology on a ‘nanoscale’. To be more precise, it is the manipulation of materials on scale that is 10000 smaller than the width of a hair to achieve desirable outcomes: those characteristics and behaviours useful to daily life. In order to explore this field of science it is important to explain the basic terminology.

The broad applicability of nanotechnology has led to considerable variation in the terms and definitions used by various scientific communities and regulatory authorities. Despite this, it is generally accepted that nanomaterials have two defining characteristics: a size on the nanoscale (between 1 nm to 100 nm) and unique size-dependent properties that are not exhibited by the bulk material, a view endorsed by IUPAC.

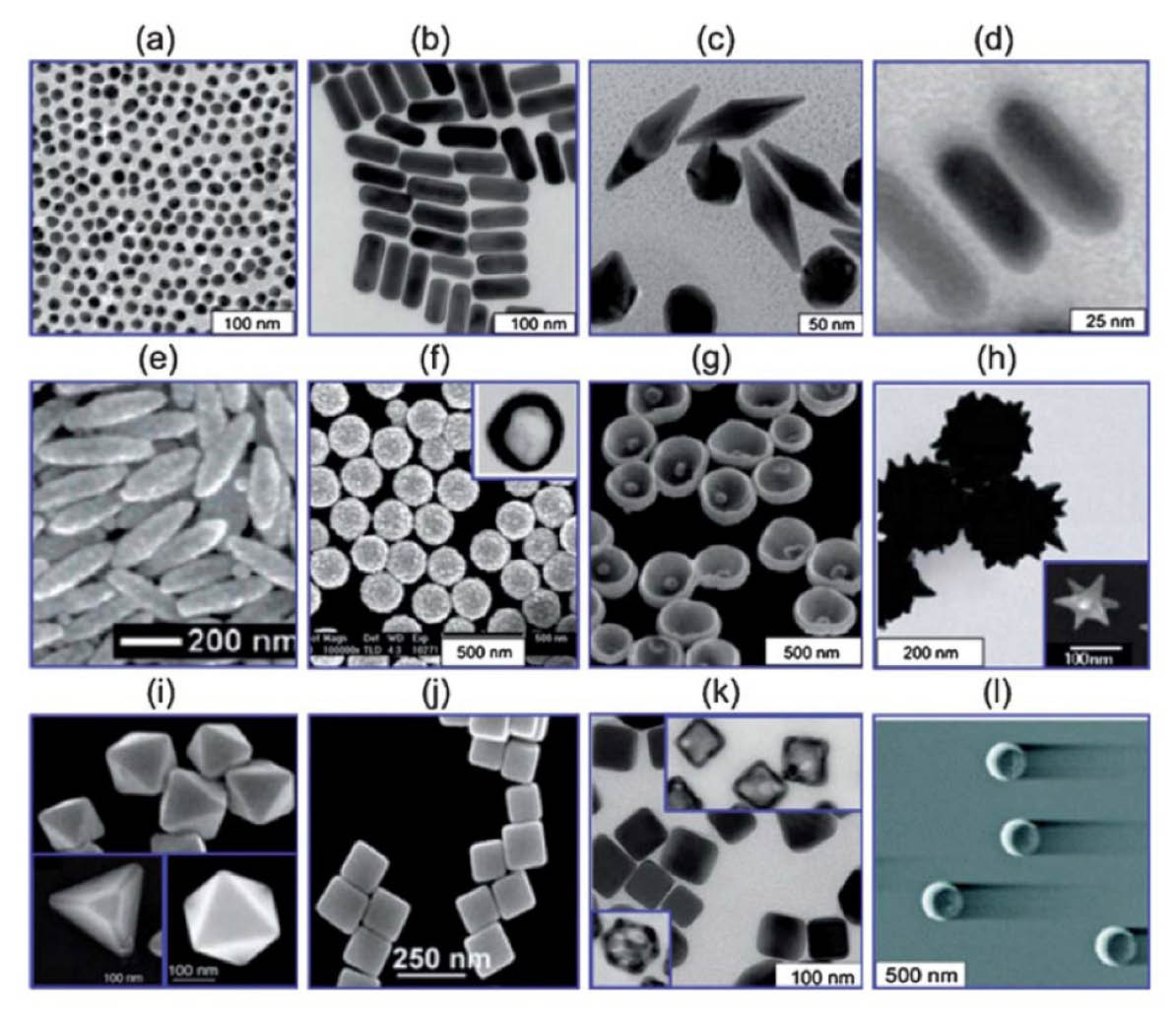

Although much initial work on nanomaterials focused on approximately spherical particles, there is now significant interest in high aspect ratio particles and one-dimensional materials. To illustrate the broad range of sizes, shapes and functions of nanoparticles, some scientists provocatively named these materials as ‘Nanoparticle ZOO’. It is therefore not surprising that a wide range of terms have been used to describe these materials. Both ISO and IUPAC recognize the terms ‘nanoparticle’, ‘nano-fibre/nano-rod’ and ‘nanoplate’ as nano-objects with either all or at least one dimension in the range of 1 nm – 100 nm. One problem is that the various terms have not been employed systematically in the literature and a variety of other terms have been used. No nano-objects can be seen by the human eye, and they are still too small to be seen even under a normal microscope. Usually, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is required to view the details of these miniscule nanostructures. The functions of each type of nanostructure is determined by their given shape and size, as well as by the type of material they are made of, and by the chemical/biochemical composition of their surface.

The exact definition of ENM and the variety of terminology used in the literature are not the only problems here, though. Regardless of the size or function of the nanomaterial, every scientist working with the ENM has encountered a problem with clustering of the nano-objects into larger assemblies. The literature is again very much inconsistent. Scientists tend to use terms such as aggregation or agglomeration of nanoparticles/nano-objects. It is possible, however, to distinguish between the strengths of the interactions that lead to clustering of nano-objects, with the term agglomeration used to describe clusters that are held together by weak forces and that can be disrupted with modest energy input and the term aggregation to describe clusters of primary particles that are held together by strong forces and are therefore difficult or impossible to disrupt. Since in most cases it is not clear which type of forces are dominant for specific nano-objects, IUPAC recommends avoiding the use of aggregation/agglomeration and instead using the term association.

Nanoparticles can occur naturally or can be engineered. Scientists’ fascination with these tiny devices emanates from the unique behaviours and characteristics they display in contrast to the larger version of themselves and from the limitless potential they may play in our future, particularly in the medical field. Incidental nanomaterials are also generated as an unintentional by-product of manufacturing, biotechnology, or other processes. In short, nanotechnology has taught us to ‘expect the unexpected’, as the resulting chemical properties can surprise us all. Over the past few decades, we have learnt how to manipulate materials on their atomic scale and how to produce totally new nanoscale materials with various novel features and properties. We have undoubtedly entered a new era of vast opportunities, where nanotechnology and nanomaterials can be exploited in a huge number of possible applications. Initially, companies and users often consider only the business or the advantages of a new material, but the past has demonstrated that materials and chemicals may also have adverse effects for human health or the environment.

Current applications

A variety of nanoparticles (formed naturally, inadvertently, and/or deliberately) are present in many foodstuffs, however it is those in the form of food additives that have caused some uncertainty and debate over long term usage and the health implications for humans. Titanium dioxide (E171), a colorant, and silicon dioxide (E551), an anti-clumping agent, are just two examples of nanosize additives found in food. Reassuringly, all additives are subjected to stringent testing for safety for human consumption. For example, in 2014 the European Commission (EC) imposed regulations that compel companies to state the inclusion of nano ingredients clearly.

The desire to enhance the durability or appearance of materials used in clothing has seen a growth in the application of nanomaterials in the production of such items as socks and insoles, where silver, known for its anti-bacterial quality, is incorporated. With shoes, the surface is sprayed with ‘silica’, preventing the water from being absorbed and giving them greater resistance to water and to general wear and tear. Once again, such applications raise concerns as to how safe these materials are if they are in direct contact with the skin.

The cosmetics industry has a huge demand for a variety of ENM; titanium dioxide and zinc oxide have great UV filtering properties, and both are used in sunscreen lotions. Once again, these materials are directly in contact with the skin and, even though they are thought unlikely to reach the bloodstream, there is limited research to support this premise.

Unlike sunscreen, tattoo inks are injected directly into the dermis. Tattoo inks contain a high proportion of nanoparticles; in the most widely used black ink, 99.94% of carbon black consists of nanoparticles. Research on rats suggests that ‘carbon black’ has been the cause of inflammation and damaged DNA and its carcinogenic properties have been recognised, and yet no direct link between tattoos and cancer has been identified. Nevertheless, there is evidence to show that nanoparticles can be transported in blood to other organs, where they accumulate, bringing their stability into question.

Research papers on the scope and potential of ENM in these fields are plentiful. However, there are few offering a critique of the perceived misconceptions of this emerging science.

Nanomedicine

Nanotechnology was thought to be a new science with the potential to revolutionise healthcare, leading to improvements in therapeutics and diagnostics. The uncertainty suggested by the possibility of a high level of risk to health, with the lack of evidence to prove otherwise, has restricted their use in advancements in medicine. Indeed, caution is paramount. In sharp contrast, the commercial world has embraced the potential they offer, with companies keen to add them to their products. Production has proceeded on a massive scale with limited knowledge, as yet, of the products’ impact on human health or the environment.

Figure 1. TEM images of various gold nanomaterials; (a) gold nanospheres, (b) gold nanorods, (c) gold bipyramids, (d) gold nanorods with silver shells, (e) nanorice, (f) SiO2/Au nanoshells (inset is a hollow nanoshell), (g) nanobowl, (h) spikey SiO2/Au nanoshells (inset is a nanostar), (i) gold tetrahedral, octahedral and cubohedra, (j) gold nanocubes, (k) silver nanocubes (insets are gold nanocages) and (l) gold nanoscrescents. Reprinted with permission from: Jiang, et al., Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012 166(6):1533-51.

The possible uses of ENM in medicine are nearly limitless. Increasingly more sophisticated methods are being developed to create nanostructures with greater complexity to act as nano-drug delivery systems (NDDS). ENM could improve the targeted delivery of medicines in healthcare, such as in the treatment of cancers. They can be formulated to control and sustain the release of the drug until arrival at the location of the target site.

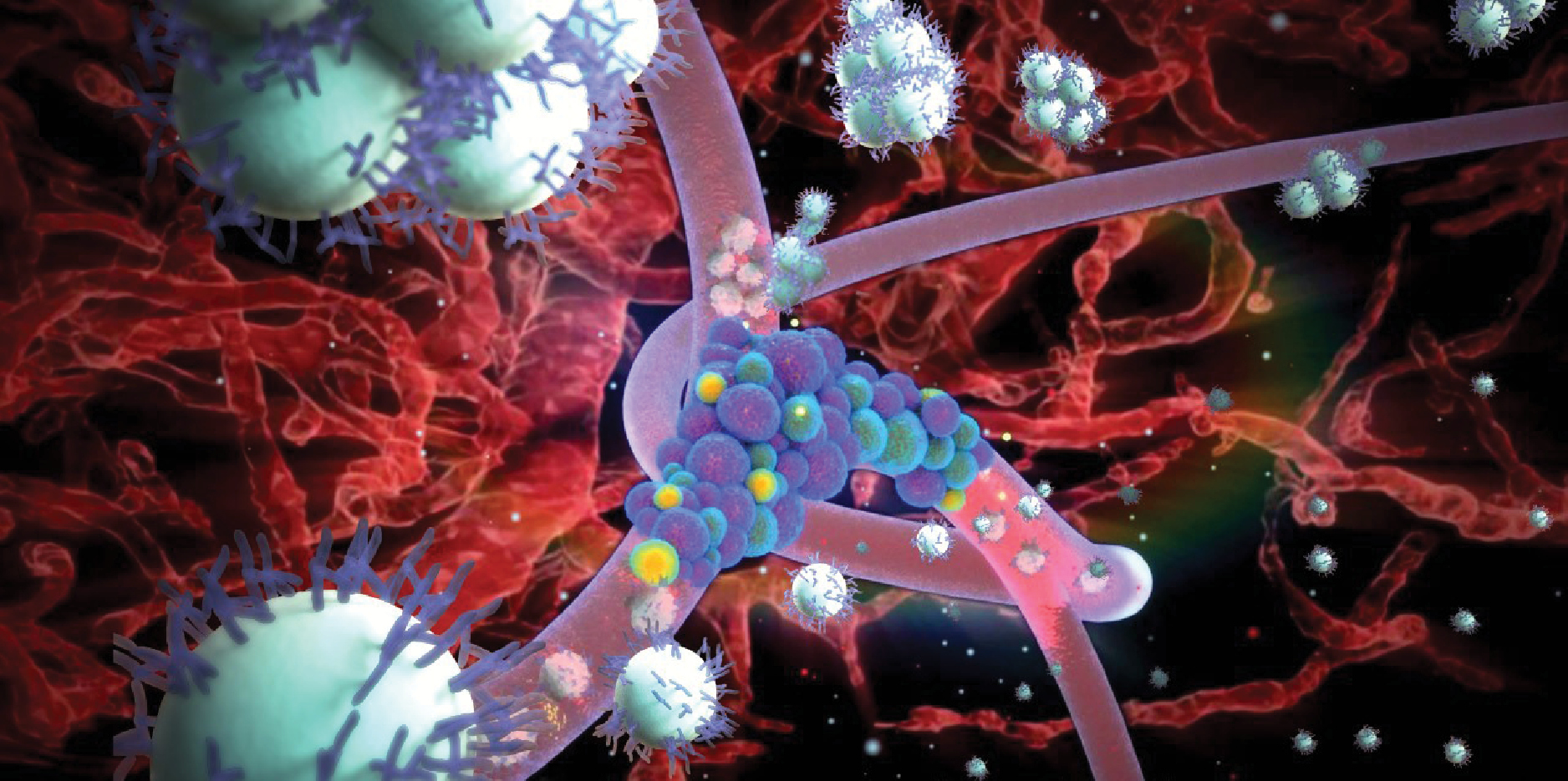

Tumours are surrounded by a rich blood supply, which makes them ideal destinations for drug carriers. When a tumour forms, the uniformity of the blood vessels becomes haphazard and gaps in their surface begin to appear, increasing the likelihood of absorption of the nanomedicines, thus directly attacking the cancer. However, this simple concept hasn’t really been demonstrated fully in humans, which is perhaps one of the reasons why so few NDDS products are available on the market. Many scientists have already asked few provocative questions: Has the nanomedicine concept been oversold? Have we simply promised too much?

Part of the problem is that to engineer precise nano-scale objects capable of multiple functions in human body, where they are seen by the immune system as foreign intruders, scientists must intensify the desired behaviours through painstaking manipulation of their architecture. Too much effort and specialised equipment is needed in order to add extra features to their surface, increase their targeting capability, and hide them from the natural defence mechanisms of the human body, thus increasing their chance of reaching the target cells/tissues.

Major Limitations of Nanomedicine

In their simplest form, nanomaterials are more robust and easy to produce on an industrial scale. However, with ENM of greater complexity, the techniques used for their creation become more complicated and specialised, making them more difficult and expensive to replicate.

The scalability of such intricate designs can lead to variations and a degree of ‘artistic licence’ in their preparation and thus variation from the prototype. On an industrial scale, the manufacturing of such medicines would lead to innumerable interpretations of the original version, resulting in further ambiguity on their behaviour when in the human body. An incorrect attachment or combination of them would reduce specificity and lead to the display of unwanted characteristics by the material, such as incorrect mobility, premature release of the drug, and the possibility of the body rejecting the medicine as ‘foreign’ to the host organism.

Figure 2. Illustration of a tumour being actively targeted with nanomaterial. Nanoparticles are equipped with antibodies on their surface to facilitate specific targeting. This concept was questioned by scientists who suggested that the targeting-antibodies on the surface of the nanomaterial are ‘hidden’ under a blanket of serum proteins that form so-called protein corona. Passive targeting, on the other hand, counts with accumulation in tumour via leaky vascularisation of the tumour, an effect confirmed on animal models but which is likely to be less prominent in humans. Illustration adapted and modified from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EscII9E785I

Tests on laboratory-prepared cell cultures and mice are indicative of the actions of NDDS, yet are not a true test of biocompatibility in real fluids and actual living human beings, where an array of cells, plasma, and their substances will come into contact and possibly interact with the nanomedicine. Lack of biocompatibility could be harmful if the NDSS is not removed from the body swiftly. The unpredictability of the associations ENM may make in the body may cause them to accumulate and have toxic effects. Their interactions cannot be observed when in solution (once in the body), therefore the positive and negative effects on the body are largely based on assumption and cannot be fully anticipated, one of many reasons why only a few delivery systems have reached the clinical stage.

One of the key issues facing this field is that, even with the best intentions, unique products engineered to be of use could inadvertently be harmful to us and to the environment at the same time. The relatively young age of this scientific field means there is little evidence of their long-term effects, in particular their toxicity. The increased use of ENM in consumer products will inevitably lead to environmental problems. For example, silver nanoparticles are washed out from silver treated textiles and in turn inhibit the activity of bacterial degradation in water treatment plants.

Nanoethics has emerged from much debate on the future of ENM and exists to assess the benefits and risks of their use, as well as if they surpass the quality and advantages of materials (in particular medicine) that are already in use. Increasing demand for alternative medicines will no doubt result in heightened concerns over animal welfare, as more trials are required: we will still rely on the reaction of animals to a medicine, which provides insight on the likely reaction of the human body.

Conclusion

The ethics of nanotechnology has created a charged atmosphere in the worlds of academia, politics, and industry. The rapid development of ENM has meant their innovation has preceded regulation. Naturally, large companies are resistant to such embargoes. Despite concerns for safety, products are already on the market and are making a difference to people’s lives. It is imperative that the regulating authorities catch up with science, ensuring that compelling evidence of toxicity and long-term effects is gained prior to the release of specific ENM on the market.

Although the focus of scientific research has been on cancer therapeutics, NDDS has the potential to accelerate progress in new therapies for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Undoubtedly, the main potential of NDDS is that they increase the specificity of a drug, ensuring the correct dosage is administered at the exact time to a specific target area. The versatility and specificity of ENM for drug delivery and diagnostics will benefit increasing numbers of patients, as well as global healthcare.

The question of their validity in our everyday lives still remains, and requires huge financial investment. Researching their biological and environmental behaviours further, as well as developing more sophisticated methods of their mass production, would help eradicate the doubt surrounding ENM, particularly with regards to medicine.

This article is a short extract from two IUPAC Technical Reports recently submitted to Pure and Applied Chemistry. Written by an international consortium of scientists, these comprehensive, interconnected reports first summarize the challenges related to the nomenclature and definition of ENM and provide an overview of the best practices for their preparation, surface functionalization, and analytical characterization (DOI 10.1515/pac-2017-0101), while in a second part, the reports focus on ENMs that are used in products that are expected to come in close contact with consumers (DOI 10.1515/pac-2017-0102). Reviewing the nanomaterials used in therapeutics, diagnostics, and consumer goods and summarizing current nanotoxicology challenges as well as the current state of nanomaterial regulation, these reports provide insight on the growing public debate on whether the environmental and social costs of nanotechnology outweigh its potential benefits.

Dr. Vladimir Gubala <V.Gubala@kent.ac.uk> (University of Kent, United Kingdom) is listed as a co-author of this article on behalf of the consortium of the following contributors (in alphabetical order): Dr. Linda J. Johnston (National Research Council Canada), Dr. Ziwei Liu (Cornell University, USA), Prof. Harald Krug (EMPA, Switzerland), Dr. Colin J. Moore (FOCAS Institute, DIT, Ireland), Prof. Christopher K. Ober (Cornell University, USA), Prof. Michael Schwenk (Tuebingen, Germany), and Prof. Michel Vert (University of Montpelier, France).

See iupac.org/project/2013-007-1-700 for more details.

©2017 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead - Full issue pdf

- From the Editorial Board

- Contents

- The First IUPAC World Chemistry Congress with a Latin Flavor

- Features

- IYCN: A Journey That Has Just Begun

- IUPAC Facilitating Chemistry Data Exchange in the Digital Era

- Nanomaterials—On the Brink of Revolution? Or the Endless Pursuit of Something Unattainable?

- Hero Worship in Words: Imitating the Grand Style of R. B. Woodward

- IUPAC Wire

- Awardees of the IUPAC 2017 Distinguished Women in Chemistry or Chemical Engineering

- Neil Garg is the Recipient of the 2016 Thieme–IUPAC Prize

- The Franzosini Award of 2016

- A Global Approach to the Gender Gap in Mathematical and Natural Sciences: How to Measure It, How to Reduce It?

- New InChI Software Release

- Project Place

- Database on Molecular Compositions of Natural Organic Matter and Humic Substances as Measured by High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

- Integrating Green Chemistry and Socio-Sustainability in Higher Education: Successful Experiences Contributing to Transform Our World

- NUTRIAGEING: Combining Chemistry, Cooking, and Agriculture

- Safety Training Program

- The Silver Book and the NPU Format for Clinical Laboratory Science Reports Regarding Properties, Units, and Symbols

- Bookworm

- Engineered Nanoparticles and the Environment: Biophysicochemical Processes and Toxicity

- Compendium of Terminology and Nomenclature of Properties in Clinical Laboratory Sciences

- Making an ImPACt

- Isotope-Abundance Variations and Atomic Weights of Selected Elements: 2016 (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Names and Symbols of the Elements with Atomic Numbers 113, 115, 117 and 118 (IUPAC Recommendations 2016)

- On the Naming of Recently Discovered Chemical Elements—the 2016 Experience

- IUPAC Provisional Recommendations

- Terminology of Bioanalytical Methods

- Nomenclature and Terminology for Dendrimers with Regular Dendrons and for Hyperbranched Polymers

- Definition of the Mole

- Terminology of Separation Methods

- NOTeS

- IUPAC Standards and Recommendations

- Conference Call

- Chemical Industry of Sustainable Development

- Bioinspired and Biobased Chemistry & Materials

- International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Validation of Test Methods, Human Errors and Measurement Uncertainty of Results

- Where 2B & Y

- Chemistry in a Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary World

- Trace Elements Analysis of Environmental Samples with X-rays

- Ionic Polymerization

- Global Challenges and Data-Driven Science

- Mark Your Calendar

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead - Full issue pdf

- From the Editorial Board

- Contents

- The First IUPAC World Chemistry Congress with a Latin Flavor

- Features

- IYCN: A Journey That Has Just Begun

- IUPAC Facilitating Chemistry Data Exchange in the Digital Era

- Nanomaterials—On the Brink of Revolution? Or the Endless Pursuit of Something Unattainable?

- Hero Worship in Words: Imitating the Grand Style of R. B. Woodward

- IUPAC Wire

- Awardees of the IUPAC 2017 Distinguished Women in Chemistry or Chemical Engineering

- Neil Garg is the Recipient of the 2016 Thieme–IUPAC Prize

- The Franzosini Award of 2016

- A Global Approach to the Gender Gap in Mathematical and Natural Sciences: How to Measure It, How to Reduce It?

- New InChI Software Release

- Project Place

- Database on Molecular Compositions of Natural Organic Matter and Humic Substances as Measured by High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

- Integrating Green Chemistry and Socio-Sustainability in Higher Education: Successful Experiences Contributing to Transform Our World

- NUTRIAGEING: Combining Chemistry, Cooking, and Agriculture

- Safety Training Program

- The Silver Book and the NPU Format for Clinical Laboratory Science Reports Regarding Properties, Units, and Symbols

- Bookworm

- Engineered Nanoparticles and the Environment: Biophysicochemical Processes and Toxicity

- Compendium of Terminology and Nomenclature of Properties in Clinical Laboratory Sciences

- Making an ImPACt

- Isotope-Abundance Variations and Atomic Weights of Selected Elements: 2016 (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Names and Symbols of the Elements with Atomic Numbers 113, 115, 117 and 118 (IUPAC Recommendations 2016)

- On the Naming of Recently Discovered Chemical Elements—the 2016 Experience

- IUPAC Provisional Recommendations

- Terminology of Bioanalytical Methods

- Nomenclature and Terminology for Dendrimers with Regular Dendrons and for Hyperbranched Polymers

- Definition of the Mole

- Terminology of Separation Methods

- NOTeS

- IUPAC Standards and Recommendations

- Conference Call

- Chemical Industry of Sustainable Development

- Bioinspired and Biobased Chemistry & Materials

- International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Validation of Test Methods, Human Errors and Measurement Uncertainty of Results

- Where 2B & Y

- Chemistry in a Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary World

- Trace Elements Analysis of Environmental Samples with X-rays

- Ionic Polymerization

- Global Challenges and Data-Driven Science

- Mark Your Calendar