Towards routine high-throughput analysis of fecal bile acids: validation of an enzymatic cycling method for the quantification of total bile acids in human stool samples on fully automated clinical chemistry analyzers

Abstract

Objectives

Bile acid diarrhea is a common but underdiagnosed condition. Because the gold standard test (75SeHCAT) is time-consuming and not widely available, fecal bile acid excretion is typically assessed by chromatography and mass spectrometry. Although enzymatic cycling assays are well established for the rapid and cost-effective analysis of total bile acids (TBA) in serum or plasma, their full potential has yet not been extended to stool samples in clinical routine.

Methods

The performance of the ‘Total bile acids 21 FS’ reagent (DiaSys) was evaluated in fecal matrix according to CLSI guidelines and EU-IVD Regulations (2017/745), and compared to an established microplate-based kit (IDK®) by measuring patient stool samples (n=122). Method agreement was assessed by Passing-Bablok and Bland-Altman analysis. The quantification of eight individual BAs was assessed using HPLC-MS/MS as reference method.

Results

The DiaSys assay showed linearity between 3.5 and 130 μmol/L, good repeatability, total precision, and reproducibility with CVs of 1.7 %, 3.5 %, and 3.0 %. Limit of blank (LoB), detection (LoD), and quantitation (LoQ) were ≤0.17, ≤0.3, and 3.5 μmol/L, respectively. No significant interference from endogenous substances was observed. The methods showed good correlation up to 140 μmol/L (r=0.988), despite differences in the quantification of individual BAs, with mean deviations of 7 % (DiaSys) and 31 % (IDK®), respectively.

Conclusions

The advantages of enzymatic TBA analysis on fully automated clinical chemistry platforms can be exploited for the routine analysis of stool samples. However, cycling assays may benefit from reference standards that take into account the composition of the fecal BA pool.

Introduction

Bile acids (BAs) are 3α-hydroxylated amphipathic steroids derived from cholesterol [1], 2]. After being synthesized in the liver, the two primary BAs, cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) are conjugated with glycine (G) or taurine (T) before excretion into the bile (Figure 1A). In response to dietary fat, the conjugated primary BAs are secreted into the duodenum, facilitating digestion and absorption of fatty acids, cholesterol, and fat-soluble vitamins [1], 2]. About 95 % are actively reabsorbed in the terminal ileum, transported back to the liver, and re-secreted into the bile (enterohepatic circulation) [1], 2]. The remaining primary BAs enter the colon, where they are deconjugated and metabolized by resident bacteria into the secondary BAs, namely deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA). In addition, CDCA can undergo epimerization to form ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). Bile acids that are not passively reabsorbed in the colon (approx. 200–600 mg/day) are excreted via the feces (Figure 1A).

Bile acids, enterohepatic circulation, and TBA cycling assay principle. (A) Primary BAs (CA and CDCA) are synthesized in the liver and conjugated to glycine (G) or taurine (T) before secretion into the duodenum. BAs reaching the colon are deconjugated and metabolized into secondary and tertiary BAs (DCA, LCA, and UDCA) by intestinal bacteria. In healthy individuals, approx. 95 % are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum. Malabsorption or overproduction can lead to excess BAs within the colon and bile acid diarrhea. (B) Enzymatic TBA cycling assays utilize 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD), which catalyzes the reversible oxidation of bile acids. In the presence of excess NADH, the linear increase in Thio-NADH can be detected at 405 nm.

Excess delivery of BAs to the colon can stimulate colonic motility and water secretion, leading to bile acid diarrhea (BAD). BAD can be classified into type 1, in patients with bile acid malabsorption (BAM) due to ileal inflammation such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and type 2, also known as primary or idiopathic BAD [2]. A systematic review suggests that 25–30 % of patients with chronic diarrhea or diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) have idiopathic BAD [3].

Although the 7-day 75seleno-taurohomocholic acid retention test (75SeHCAT) is considered the diagnostic gold standard for BAD, it is relatively expensive and time-consuming. Furthermore, 75SeHCAT has limited availability and is not approved in several countries, including the United States [4], [5], [6]. Instead, the fecal excretion of total bile acids (TBA) is quantified over 48 h, mainly using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which is expensive and time-consuming, making it less suitable for high-throughput diagnostics [7], 8].

In this regard, enzymatic cycling methods based on 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) offer significant advantages by combining simplicity, accessibility, and low costs [7], 8]. 3α-HSD catalyzes the reversible oxidation of 3α-hydroxylated steroids [7], 8]. Current 5th-generation TBA routine assays utilize thionicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (Thio-NAD+) as a coenzyme [8], [9], [10]. In the presence of excess NADH, the amplified generation of Thio-NADH can be detected as a linear increase in optical density at 405 nm (Figure 1B) [7]. Recently, a photometric kit has been developed (IDK® Bile Acids) for the enzymatic quantification of fecal TBA on manual photometers or microplate readers. Using this method, Kumar et al. (2022) reported that TBA measurement in a single random stool sample may have diagnostic utility for severe BAD [11].

Here, we evaluated the ‘Total bile acids 21 FS’ assay (DiaSys), originally developed for the routine TBA analysis in serum, for its performance in human stool samples. The reagent was validated for the new intended use on a respons® 910 analyzer according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines and the European In Vitro Diagnostics Regulation (EU-IVD 2017/745). The application was compared to the IDK® Bile Acids kit by measuring 122 patient stool extracts. In addition, the quantification of eight individual BAs (CA, CDCA, DCA, UDCA, TCA, GCA, TCDCA, and GCDCA) was assessed, using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) as non-enzymatic reference method.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Stool extracts were prepared from anonymous left-over samples provided by Biovis Diagnostik MVZ GmbH in IDK Extract® specimen tubes (Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany). The samples were thawed, vortexed, and centrifuged for 10 min at 2.300 g. The supernatant containing the extracted fecal bile acids (resulting dilution: 1:100) was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80 °C until measurement.

Total bile acid measurement

For method validation and comparison, the Total bile acids 21 FS reagent (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems GmbH, Holzheim, Germany) was performed on the automated respons® 910 analyzer (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The linear increase in Thio-NADH was detected at 405 nm (primary wavelength) and 600 nm (secondary wavelength) [7]. Assay performance was confirmed on two clinical chemistry analyzers respons® 940 (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany) and BioMajesty® JCA-BM6010/C (JEOL Ltd, Akishima, Japan). See Supplementary Tables S1–S4 for further details.

The photometric IDK® Bile Acids reagent (Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany) was performed on a Sunrise™ microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 405/620 nm wavelength. Samples exceeding the highest IDK® standard (>90 μmol/L) were diluted 1:1 with IDK Extract® buffer as recommended by the manufacturer. For method comparison, patient stool extracts (n=122) were measured in duplicate. See Supplementary Tables S1–S3 for further details.

For the measurement of individual bile acids, the two reagents were adapted for use on a BioMajesty® JCA-BM6010/C analyzer (JEOL Ltd, Akishima, Japan). After calibration using the assay-specific standards, eight individual bile acid solutions were measured in single determination. Thio-NADH formation was detected at 410/596 nm wavelength. See Supplementary Tables S1–S3 for further details. The preparation of aqueous bile acid solutions (weigh in: 50 μmol/L) was described previously [10]. Bile acid salts (≥95 % purity) and bile acid solutions in methanol (≥98 % purity) for calibration were purchased from AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, USA), respectively.

Linearity

The linear range was assessed according to CLSI guidelines (EP06, 2nd Edition) for three different reagent lots by measuring serial dilutions of two different stool extracts with low (52 μmol/L) and high (170 μmol/L) total bile acid concentrations [12]. To assess lower and upper linearity, both extracts were serially diluted with IDK® extraction buffer (dilutions: 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) and measured in four replicates. The theoretical value for each dilution was calculated by linear regression analysis and the mean recovery was assessed. Acceptance criteria were ± 15 % deviation from the theoretical value for lower linearity (between 0 and 15 μmol/L) and ± 10 % deviation for upper linearity (between 15 and 130 μmol/L).

Precision

Within-run precision (repeatability) and within-laboratory precision (total precision) were assessed according to CLSI guidelines (EP05, 3rd Edition) for three reagent lots and three stool samples with analyte concentrations in the lower normal range (<20 μmol/L), near the decision cut-off (60–80 μmol/L), and in the upper measuring range (>100 μmol/L) [13]. The stool extracts were pooled and aliquots were frozen at −80 °C until measurement. The repeatability was assessed by 20 sequential measurements of one aliquot for each concentration (n=20). The total precision was assessed over 20 days (two runs per day with two replicates each) on the same analyzer (n=80), using a fresh aliquot for each run. The order of samples and controls was changed in every run, and the time of measurement varied daily. For the reproducibility studies, the samples were analyzed over five days (one run with five replicates per day) on three different analyzers (n=75). The final results were reported as coefficient of variation (CV).

Detection capability

The limit of blank (LoB), limit of detection (LoD), and limit of quantitation (LoQ) were assessed according to CLSI guidelines (EP17, 2nd Edition) for three different reagent lots [14]. To determine the LoB, four blank samples (IDK® Extraction buffer) were measured over three days with five replicates per day (n=60). The LoB was calculated using the following equation: LoB=mean blank + 1.645 × SD blank sample. To determine the LoD, five low-level samples (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.7 μmol/L) were prepared from stool extract by dilution with IDK® Extraction buffer and measured in five-fold determination over three days (n=75). The LoD was calculated using the following equation: LoD=LoB + 1.645 × SD low-level sample. To determine the LoQ, nine samples (1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, and 6.0 μmol/L) were prepared from stool extract and measured over 20 days (two runs per day with two replicates each) on the same analyzer (n=80). The LoQ is given as the lowest concentration measured with a within-laboratory CV of <20 %.

Interference

The interference from endogenous substances was assessed according to CLSI guidelines (EP07, 3rd Edition) using two pooled stool extracts with final analyte concentrations of <40 μmol/L and >80 μmol/L [15]. Each dilution step was measured in five-fold determination.

HPLC-MS/MS method

HPLC-MS/MS measurement of aqueous bile acid solutions was performed as described previously [10], using a 3200 QTRAP® LC-MS/MS System (AB Sciex Pte Ltd., Framingham, USA), Series 200 Micro Pumps and Autosampler (PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA), CORTECS T3 Column (120 Å, 2.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) and CORTECS T3 VanGuard Cartridge (120 Å, 2.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 5 mm; Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). HPLC-MS/MS data was evaluated using Analyst software (Version 1.5.1, build 5218) and MultiQuant™ software (Version 3.0.2, build 8664.0), respectively (Sciex, Framingham, USA). HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile (ACN) were purchased from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Passing-Bablok regression and Spearman’s rank correlation were used to compare methods and quantify the proportional differences between measurement results. As the Passing-Bablok method is only valid for linear relationships, linearity was assessed using the Cusum test (p>0.05) prior to the regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc® (Version 18.10.2, MedCalc Software Ltd, Belgium) and Microsoft Excel 2021.

Results

Linearity

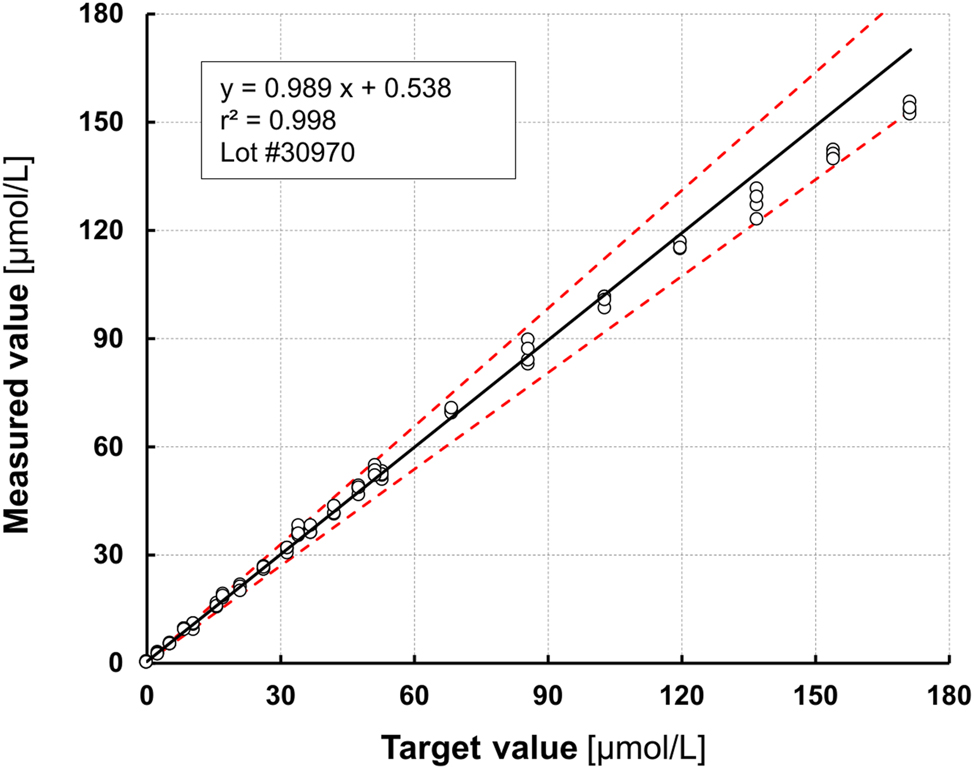

The Total bile acids 21 FS assay exhibited linear behavior between 3.5 and 130 μmol/L and met the CLSI acceptance criteria in this concentration range for all three reagent lots tested. The results for Lot 1 (#30970) on respons® 910 are shown in Figure 2. See Supplementary Figure S1 for further details. The linear behavior up to 130 μmol/L could be confirmed on the respons® 940 analyzer (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany; see Supplementary Figure S2).

Linearity assessment. The linear range (3.5–130 μmol/L) was estimated according to CLSI acceptance criteria (CLSI EP05) by serial dilution of two different stool extracts for lower linearity (0–50 μmol/L) and upper linearity (0–170 μmol/L).

Precision and detection capability

The results are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. The within-run precision (repeatability) was between 1.09 and 2.06 % (CV near cut-off: ≤1.66 %), and the within-laboratory precision (total precision) was between 2.61 and 4.1 % (CV near cut-off: ≤3.51 %). The reproducibility (CV near cut-off) was found to be ≤3.01 % (Table 1). LoB, LoD and LoQ were ≤0.17, ≤0.3, and 3.5 μmol/L, respectively (Table 2). The good within-run precision for stool samples <20 μmol/L and ≥140 μmol/L was confirmed on respons® 940 (CV: 0.58–1.41 %) and BioMajesty® JCA-BM6010/C (CV: 0.60–1.04 %) (Supplementary Table S4). In addition, the TBA 21 FS reagent showed excellent inter-instrument agreement when run on different analyzers, with r=0.998 (respons® 940 vs. respons® 910) and r=0.999 (respons® 940 vs. BioMajesty® JCA-BM6010/C; Supplementary Figure S3).

Assay imprecision (CLSI EP05, 3rd Edition).

| <20 μmol/L | 60–80 μmol/L | >100 μmol/L | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ( ± SD), µmol/L | CV, % | Mean ( ± SD), µmol/L | CV, % | Mean ( ± SD), µmol/L | CV, % | ||

| Repeatability (n=20) | Lot 1 | 14.7 (0.22) | 1.50 | 70.8 (0.77) | 1.09 | 115.0 (2.37) | 2.06 |

| Lot 2 | 14.3 (0.24) | 1.68 | 69.0 (1.06) | 1.53 | 115.5 (1.55) | 1.34 | |

| Lot 3 | 14.5 (0.23) | 1.59 | 71.0 (1.18) | 1.66 | 118.8 (1.52) | 1.28 | |

| Total precision (n=80) | Lot 1 | 15.1 (0.52) | 3.46 | 73.3 (2.22) | 3.02 | 122.2 (3.55) | 2.91 |

| Lot 2 | 14.8 (0.61) | 4.09 | 72.5 (2.54) | 3.51 | 120.0 (4.13) | 3.44 | |

| Lot 3 | 14.9 (0.56) | 3.74 | 72.9 (1.90) | 2.61 | 121.6 (3.26) | 2.63 | |

| Reproducibility (n=75) | 15.0 (0.6) | 4.08 | 74.2 (2.2) | 3.01 | 124.7 (4.2) | 3.35 | |

-

Highest CV value is highlighted in bold.

Detection capability (CLSI EP17, 2nd Edition).

| Limit of blank (LoB), μmol/L | Limit of detection (LoD), μmol/L | Limit of quantitation (LoQ), μmol/L | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lot 1 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 3.50 |

| Lot 2 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 3.50 |

| Lot 3 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 3.50 |

Interference

The results of the interference testing are summarized in Table 3. No significant interference from ascorbic acid, conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin, hemoglobin, triglycerides or immunoglobulin A (IgA) could be observed in stool samples with low (<40 μmol/L) and high (>80 μmol/L) analyte concentration (Table 3).

Interference from endogenous substances (CLSI EP07, 3rd Edition).

| Substance | Interference in stool extracts (dilution 1:100) ≤10 % up to | Analyte concentration [µmol/L] |

|---|---|---|

| Ascorbic acid | 1.2 mg/dL | 30.5/86.6 |

| Bilirubin (conjugated) | 0.74 mg/dL | 31.8/91.8 |

| Bilirubin (unconjugated) | 0.68 mg/dL | 31.1/90.3 |

| Hemoglobin | 12 mg/dL | 30.8/88.9 |

| Immunoglobulin A | 3 mg/dL | 30.7/87.6 |

| Triglycerides | 24 mg/dL | 30.1/84.7 |

Method comparison

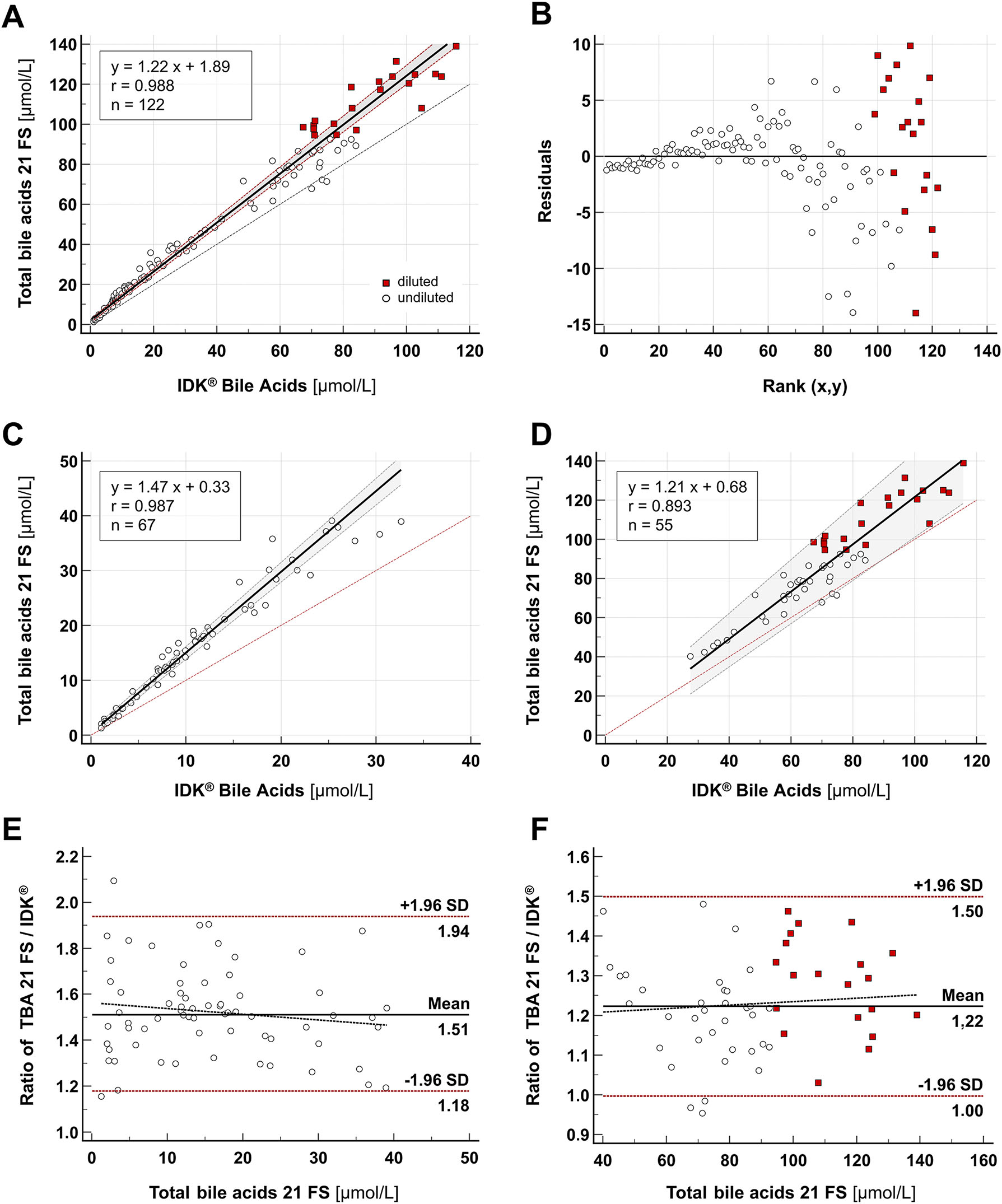

To assess the agreement with an established method, patient stool extracts (n=122) were analyzed in parallel using both the TBA 21 FS reagent performed on a fully-automated respons® 910 analyzer and the microtiter-based IDK® Bile Acids kit. Samples exceeding the highest IDK standard (>90 μmol/L) were diluted 1:1 with IDK Extract® buffer as recommended by the manufacturer. Both methods showed good overall correlation (Spearman r: 0.988; 95 % CI: 0.983–0.992; p<0.0001) with a proportional bias of approx. 22 % (slope: 1.22; 95 % CI: 1.19–1.27) (Figure 3A and B). Since the Cusum test indicated a significant deviation from linearity over the entire concentration range (p<0.01), the proportional differences were reevaluated by Passing-Bablok and Bland-Altman analysis for samples with TBA<40 μmol/L (n=67) and >40 μmol/L (n=55), respectively (Figure 3C–F). The correlation was lower for stool extracts in the upper measuring range (Spearman r: 0.893; 95 % CI: 0.823–0.937) compared to samples with low analyte concentration (Spearman r: 0.987; 95 % CI: 0.978–0.992), despite the recommended 1:1 dilution of samples >90 μmol/L. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Method comparison. (A–B) Passing-Bablok regression analysis for the measurement of TBAs in stool samples (n=122). Stool extracts (dilution: 1:100) with fecal TBA concentration>90 μmol/L were further diluted according to the IDK® assay’s instructions for use (red squares). (C–D) Passing-Bablok regression and (E–F) Bland-Altman analysis for stool extracts<40 μmol/L (n=67) and >40 μmol/L (n=55).

Method comparison.

| Spearman correlation | Passing-Bablok regression | Bland-Altman | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte concentration range (Dilution 1:100) |

r (95 % CI) p<0.0001 |

Slope (95 % CI) |

Intercept (95 % CI) | Cusum p |

Mean ratio: TBA FS 21/IDK ( ± 1.96 SD) |

| 1–140 μmol/L (n=122) |

0.988 (0.983–0.992) |

1.22 (1.19–1.27) |

1.89 (0.86–2.51) |

<0.01a | 1.37 (1.01–1.87) |

| <40 μmol/L (n=67) |

0.987 (0.978–0.992) |

1.47 (1.40–1.53) |

0.33 (−0,18–0.84) |

0.09 | 1.51 (1.18–1.94) |

| >40 μmol/L (n=55) |

0.893 (0.823–0.937) |

1.21 (1.10–1.37) |

0.68 (−9.30–7.41) |

0.49 | 1.22 (1.00–1.50) |

-

aSignificant deviation from linearity (p<0.05).

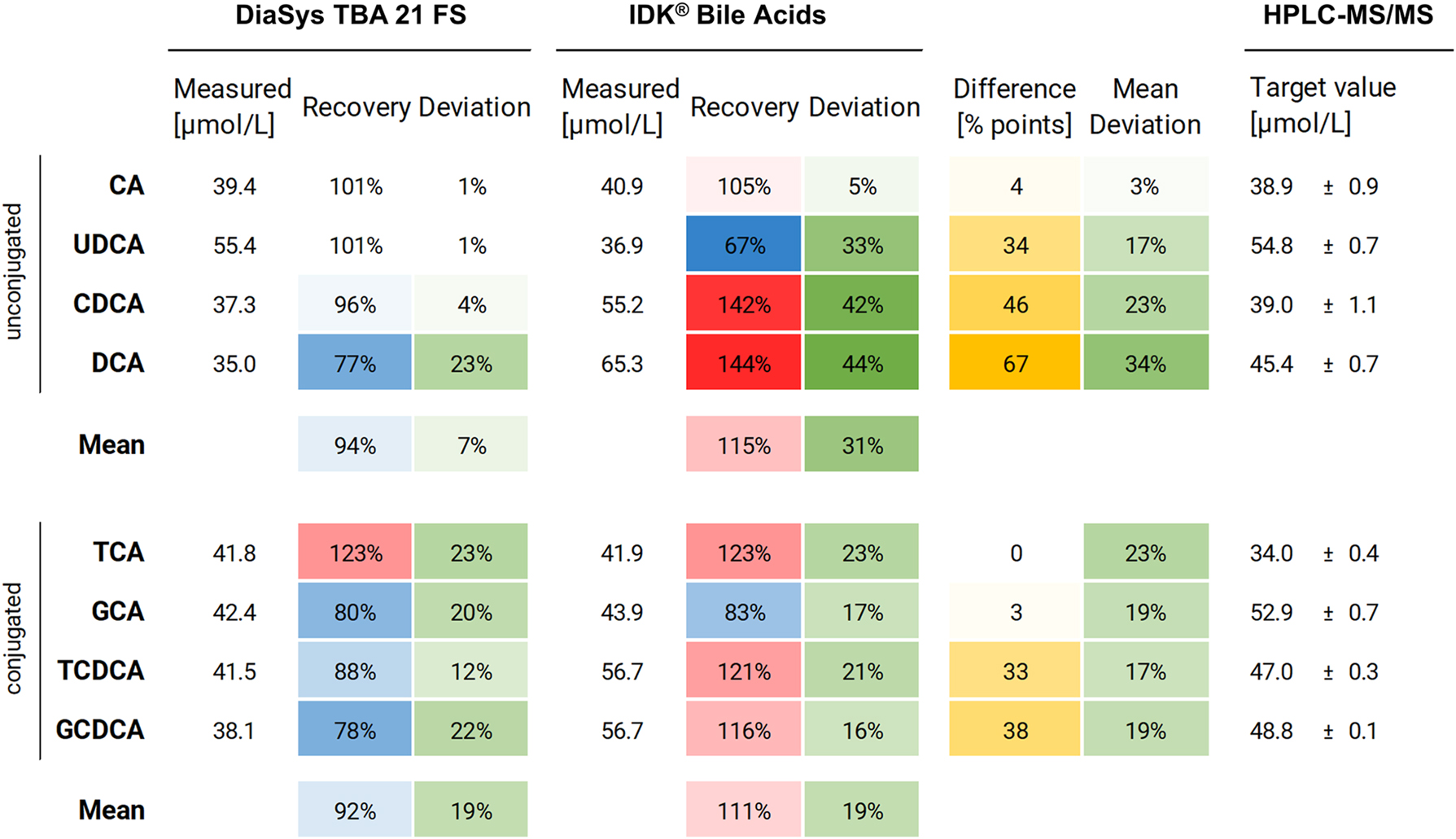

Quantification of individual bile acids

Previous studies have shown that enzymatic TBA assays display variable recovery of individual bile acids [7], 9], 16], 17]. Therefore, method agreement will be affected by the individual BA composition of the sample, especially for samples with a fecal BA spectrum that differs significantly from that of the calibration standards. To compare the quantification of individual bile acids, both reagents were adapted for use on a BioMajesty® JCA-BM6010/C analyzer. Eight aqueous bile acid solutions were measured in single determination. The reference concentration was determined by HPLC-MS/MS. The recovery of deconjugated and T/G-conjugated bile acids is summarized in Figure 4. While CA was measured with the highest accuracy and lowest mean deviation from reference (3 %), TCA and GCA were consistently over- or undermeasured by both enzymatic assays, with mean recoveries of 123 % (TCA) and 82 % (GCA), respectively (Figure 4). The Total bile acids 21 FS assay recovered UDCA and CDCDA with a deviation of +1 % and −4 %, respectively, whereas the IDK assay deviated by −33 % (UDCA) and +42 % (CDCA). The largest discrepancy was observed for DCA, one of the most highly abundant fecal BAs, with a recovery of 77 % (DiaSys) vs. 144 % (IDK). Across all non-conjugated BAs tested, namely CA, CDCA, UDCA, and DCA, the assays showed a mean deviation from HPLC-MS/MS-reference value of 7 % (DiaSys) and 31 % (IDK), respectively (Figure 4).

Recovery of individual BAs from HPLC-MS/MS reference value. Unconjugated and T/G-conjugated BAs are sorted by assay disagreement (arithmetic difference between recovery rates in percent points) from minimum (white) to maximum (yellow). Recovery: <100 % (blue), 100 % (white), >100 % (red). Deviation: minimum (white), maximum (green).

Discussion

Although enzymatic TBA cycling assays are well established in clinical routine for the rapid and cost-effective quantification of serum TBA, their full potential has not been extended to the routine analysis of fecal bile acids. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the evaluation and validation of a commercial 5th-generation TBA routine assay for the quantification of total bile acids in patient stool samples – collected in routine-compatible stool preparation tubes – on a fully-automated clinical chemistry platform.

Various hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal diseases are accompanied by pathological changes in bile acid synthesis, metabolism, secretion, and absorption, which leads to detectable changes in the circulating BA pool [1], [18], [19], [20], [21]. Especially the diagnostic value of serum TBA is well established since an elevation above the normal range (>10 μmol/L) is frequently observed in patients with liver diseases [18], 22], 23]. Furthermore, serum TBA is an important biomarker to assess hepatobiliary function in veterinary medicine [24], 25]. Enzymatic assays are the preferred detection method in clinical routine, although the recombinant 3α-HSD cannot differentiate between individual BAs and is restricted to steroids with a free 3α-OH group [7]. In 2022, Žížalová et al. reported that enzymatic 3rd-generation assays may systematically underestimate the serum TBA concentration compared to the more specific LC-MS/MS method, mainly because 3α-HSD exhibits different activity for different individual bile acids [17]. Grimmler et al. (2024) recently compared the analytical performance of five 5th-generation TBA cycling assays for the measurement in patient serum samples on the same clinical chemistry platform [10]. All commercial routine assays showed excellent correlation for the TBA measurement in serum (Spearman r>0.99), despite substantial differences in the quantification of individual BAs [10]. Others reported similar results for patient plasma, with good correlation among the three commercial TBA assays tested (Spearman’s r>0.82), and excellent correlation with the LC-MS reference method (Spearman r>0.92) [9]. The proportional bias between the commercial assays has been mainly attributed to the heterogeneous composition of proprietary calibrators, which typically contain different individual bile acids such as GCA, CDCA, or TDCA [9], 17]. In line with these results, we observed good correlation between the microtiter-based assay from IDK and the analyzer-based assay from DiaSys, especially for stool extracts with fecal TBA levels<40 μmol/L (dilution 1:100), which corresponds to 4 μmol/g stool (with 1 g stool ≙ 1 mL). The correlation was lower for stool extracts with higher TBA concentration, despite the additional 1:1 dilution step recommended for the IDK assay for samples above the highest assays-internal IDK standard (>96 μmol/L). Of note, the IDK microtiter version (K7878W) demonstrated linearity between 1.9 and 54.8 μmol/L (Supplementary Table S2), and the cuvette version (K7878CV) between 10.98 and 36.83 μmol/L, according to the manufacturer [26]. Hence, a further dilution of stool extracts may be sufficient to improve the agreement with the DiaSys test in the upper TBA range.

Based on internal studies, both manufacturers estimated the upper reference range limit for healthy individuals to be 6.5 μmol/g (as measured by IDK) or 7.0 μmol/g (for women) and 8.4 μmol/g (for men), respectively (as measured by DiaSys). This discrepancy is consistent with the ⁓20 % bias between the two assays reported in this study for stool extracts>40 μmol/L (Table 4). The assays were calibrated according to the respective instructions for use, against a different assay-specific bile acid standard. Although the exact composition is a trade secret, it is reasonable to assume that a varying BA content may contribute to the observed proportional bias; in addition to other methodological differences, such as the recombinant enzyme, reaction conditions, and detection method. The calibration against a single bile acid may also explain, why most enzymatic methods seem to underestimate the TBA concentration compared to LC-MS-based techniques – especially in samples with pathological TBA levels and substantial overrepresentation of “atypical” individual BAs [9], 17]. In serum from patients with liver disease, e.g., the conjugated primary BAs were found to be over-proportionally elevated, between 13.8-fold for GCDCA and 97.2-fold for TCA, compared to the 3.1- and 2.4-fold increase observed for CA and CDCA, respectively [27]. A similar, non-uniform elevation under pathological conditions has been demonstrated for fecal bile acids. For example, Duboc et al. (2010) reported significantly higher levels of conjugated and 3-OH-sulfated BAs in the stool of patients with active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), due to the IBD-related BA dysbiosis and dysmetabolism [16]. In contrast, the proportion of secondary BAs was significantly reduced compared to healthy individuals [16].

BAD is generally regarded as an underdiagnosed condition [28]. In a survey of UK patients, 44 % reported a delay of more than 5 years before the correct diagnosis [29]. When the 7-day SeHCAT retention test is not available, at least testing for fecal BAs should be considered [30]. Since fecal TBAs were found to be elevated in every second patient with chronic unexplained diarrhea (51 %), it has been proposed that a widespread biochemical analysis in clinical routine could help to reduce healthcare costs from unnecessary diagnostic imaging [31]. However, fecal analysis is generally more challenging than blood analysis [32]. This is primarily due to the higher complexity associated with sample collection, processing, and analyte normalization, as well as the higher variability and heterogeneity in sample composition [32], 33]. The individual BA content of each stool sample depends on numerous variables, including sex, with men having a higher mean TBA concentration than women, the previous diet, and the patient’s gut microbiome [32], 34]. This is why the 48-h fecal bile acid test requires a standardized 4-day high-fat diet before the 2-day stool collection. Both an increase in the fecal TBA excretion (≥2,337 µmol/48 h) and the percentage of primary BAs (>10 %) are considered diagnostic for BA malabsorption and -diarrhea [3], 20], 28]. However, the BA concentration is usually determined by HPLC, which is time-consuming and not suitable for the routine analysis of large sample numbers [4], 8], 28]. In a prospective, observational study, Kumar et al. recently analyzed the TBA concentration in single random stool samples obtained from patients with chronic diarrhea (>6 weeks), using the microtiter plate-based IDK® Bile Acids test [11]. The authors reported a significantly higher fecal TBA mean concentration for subjects with mild and severe BAD, i. e. with 75SeHCAT retention <15 % (4.95 μmol/g; IQR: 2.6–10.5) and <5 % (9.9 μmol/g; IQR: 4.8–15.4), respectively, compared to the control group (2.6 μmol/g; IQR: 1.6–4.2) [11]. At a fecal TBA cut-off of 4.3 μmol/g, sensitivity and specificity were 57 and 77 %, respectively, relative to 75SeHCAT retention of ≤15 % [11]. Furthermore, a fecal TBA concentration >10.1 μmol/g (as determined enzymatically in a single, random stool sample) demonstrated 91 % specificity for mild, moderate, or severe BAD – providing a feasible measure to stratify patients with unexplained chronic diarrhea who should undergo further evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of BAD [11].

In conclusion, these results indicate that the performance of enzymatic TBA routine assays is appropriate for use in clinical routine to identify patients with elevated fecal bile acid levels; considering an upper reference limit between 6 and 8 μmol/g (≙ 60–80 μmol/L for the 1:100 diluted extract). The Total bile acids 21 FS assay (DiaSys) showed linearity up to 130 μmol/L (Figure 1), as well as good repeatability, total precision, and reproducibility, especially near the presumable 60–80 μmol/L cut-off (Table 1).

Further studies will be required to confirm the normal fecal TBA range in healthy individuals, when “total bile acids” are determined enzymatically. Furthermore, high-throughput analysis requires feasible, standardized, and routine-compatible methods for stool sampling and bile acid extraction. In this regard, commercial stool preparation systems, such as those used in this study and by Kumar et al., offer several advantages [11]. The dipstick-based collection tube enables simple and hygienic sampling at home – once or over several days, with or without a previous standardized diet – and a rapid and standardized extraction of fecal bile acids. The resulting stool extracts (dilution 1:100) can be directly measured on a clinical chemistry analyzer without further dilution, given the upper linear range limit of 130 μmol/L. In this study, only 2/122 patient stool extracts (1.6 %) slightly exceeded this concentration (Figure 3A and B).

To further improve harmonization, commercial TBA cycling assays should be calibrated against a well-defined reference standard, comprising appropriate bile acids most relevant to the intended use and sample matrix. In human serum, the glycin-conjugated GCDCA, GDCA, and GCA are among the most abundant BAs. In contrast, the fecal BA pool of healthy individuals mainly comprises the unconjugated secondary DCA and LCA (approx. 32 % each), with only small amounts of CA, CDCA, and UDCA (≤2 % each) [34]. In general, the agreement between the two enzymatic methods was best for CA, TCA, and GCA. However, only CA was quantified with high accuracy by both methods, with a deviation of ≤5 % from HPLC-MS/MS reference. For DiaSys, a similar accuracy could be observed for the quantification of CDCA (−4%) and UDCA (−1%), whereas the IDK stool test overestimated CDCA (+44 %) and underestimated UDCA (−33 %). Notably, the quantification of DCA, one of the most highly abundant fecal BAs, resulted in the highest disagreement and deviation from reference, ranging from −23 % (DiaSys) to +44 % (IDK). While both enzymatic methods correlated well over the entire fecal TBA range, the proportional bias (between 20 and 50 %) may indicate that the development of TBA stool assays should focus on the most abundant fecal BAs, to further improve accuracy and inter-assay agreement.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sandra Koneberg for her valuable contribution, and Sebastian Alers for providing scientific writing and editorial support, which was funded by DiaSys Diagnostic Systems GmbH (Holzheim, Germany) in line with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

-

Research ethics: This retrospective analysis was conducted in line with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Review Board approval was not required as the residual patient samples were obtained in a fully anonymized fashion.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: DeepL was used to improve grammar and readability of selected sections.

-

Conflict of interest: A. Masetto, T. Leber, and Kai Prager are employed by DiaSys Diagnostic Systems GmbH (Holzheim, Germany). M. Grimmler is employed by DiaSys Diagnostic Systems GmbH (Holzheim, Germany) and DiaServe Laboratories GmbH (Iffeldorf, Germany). The other authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Di Ciaula, A, Garruti, G, Lunardi Baccetto, R, Molina-Molina, E, Bonfrate, L, Wang, DQH, et al.. Bile acid physiology. Ann Hepatol 2017;16:S4–14. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0010.5493.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Marasco, G, Cremon, C, Barbaro, MR, Falangone, F, Montanari, D, Capuani, F, et al.. Pathophysiology and clinical management of bile acid diarrhea. J Clin Med 2022;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11113102.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Valentin, N, Camilleri, M, Altayar, O, Vijayvargiya, P, Acosta, A, Nelson, AD, et al.. Biomarkers for bile acid diarrhoea in functional bowel disorder with diarrhoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2016;65:1951–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309889.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Liu, Y, Rong, Z, Xiang, D, Zhang, C, Liu, D. Detection technologies and metabolic profiling of bile acids: a comprehensive review. Lipids Health Dis 2018;17:121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0774-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Lyutakov, I, Ursini, F, Penchev, P, Caio, G, Carroccio, A, Volta, U, et al.. Methods for diagnosing bile acid malabsorption: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19:185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-1102-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Farrugia, A, Arasaradnam, R. Bile acid diarrhoea: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021;12:500–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2020-101436.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Zhang, GH, Cong, AR, Xu, GB, Li, CB, Yang, RF, Xia, TA. An enzymatic cycling method for the determination of serum total bile acids with recombinant 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;326:87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Zhao, X, Liu, Z, Sun, F, Yao, L, Yang, G, Wang, K. Bile acid detection techniques and bile acid-related diseases. Front Physiol 2022;13:826740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.826740.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Danese, E, Salvagno, GL, Negrini, D, Brocco, G, Montagnana, M, Lippi, G. Analytical evaluation of three enzymatic assays for measuring total bile acids in plasma using a fully-automated clinical chemistry platform. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179200. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Grimmler, M, Frömel, T, Masetto, A, Müller, H, Leber, T, Peter, C. Performance evaluation of enzymatic total bile acid (TBA) routine assays: systematic comparison of five fifth-generation TBA cycling methods and their individual bile acid recovery from HPLC-MS/MS reference. Clin Chem Lab Med 2025;63:753–63.10.1515/cclm-2024-1029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Kumar, A, Al-Hassi, HO, Jain, M, Phipps, O, Ford, C, Gama, R, et al.. A single faecal bile acid stool test demonstrates potential efficacy in replacing SeHCAT testing for bile acid diarrhoea in selected patients. Sci Rep 2022;12:8313. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12003-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Clsi EP06 – evaluation of linearity of quantitative measurement procedures, 2nd ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2020. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/method-evaluation/documents/ep06/.Search in Google Scholar

13. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Clsi EP05 – evaluation of precision of quantitative measurement procedures, 3rd ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2014. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/method-evaluation/documents/ep05/.Search in Google Scholar

14. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Clsi EP17 – evaluation of detection capability for clinical laboratory measurement procedures, 2nd ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/method-evaluation/documents/ep17/.Search in Google Scholar

15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI EP07 – interference testing in clinical chemistry, 3rd ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/method-evaluation/documents/ep07/.Search in Google Scholar

16. Ducroq, DH, Morton, MS, Shadi, N, Fraser, HL, Strevens, C, Morris, J, et al.. Analysis of serum bile acids by isotope dilution-mass spectrometry to assess the performance of routine total bile acid methods. Ann Clin Biochem 2010;47:535–40. https://doi.org/10.1258/acb.2010.010154.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Žížalová, K, Vecka, M, Vítek, L, Leníček, M. Enzymatic methods may underestimate the total serum bile acid concentration. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236372. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236372.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Hofmann, AF. The continuing importance of bile acids in liver and intestinal disease. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2647–58. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.22.2647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. James, SC, Fraser, K, Young, W, Heenan, PE, Gearry, RB, Keenan, JI, et al.. Concentrations of fecal bile acids in participants with functional gut disorders and healthy controls. Metabolites 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11090612.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Liu, T, Ma, M, Li, K, Tan, W, Yu, H, Wang, L. Biomarkers for bile acid malabsorption in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2023;57:451–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0000000000001841.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Sugita, T, Amano, K, Nakano, M, Masubuchi, N, Sugihara, M, Matsuura, T. Analysis of the serum bile Acid composition for differential diagnosis in patients with liver disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015;2015:717431. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/717431.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Javitt, NB. Diagnostic value of serum bile acids. Clin Gastroenterol 1977;6:219–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-5089(21)00394-1.Search in Google Scholar

23. Ferraris, R, Colombatti, G, Fiorentini, MT, Carosso, R, Arossa, W, La Pierre, M. Diagnostic value of serum bile acids and routine liver function tests in hepatobiliary diseases. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value. Dig Dis Sci 1983;28:129–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01315142.Search in Google Scholar

24. Schlesinger, DP, Rubin, SI. Serum bile acids and the assessment of hepatic function in dogs and cats. Can Vet J 1993;34:215–20.Search in Google Scholar

25. Luo, L, Schomaker, S, Houle, C, Aubrecht, J, Colangelo, JL. Evaluation of serum bile acid profiles as biomarkers of liver injury in rodents. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol 2014;137:12–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kft221.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Manual. IDK® Bile Acids (K 7878W). Immundiagnostik AG; 2022. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/de/testkits/k-7878w.Search in Google Scholar

27. Luo, L, Aubrecht, J, Li, D, Warner, RL, Johnson, KJ, Kenny, J, et al.. Assessment of serum bile acid profiles as biomarkers of liver injury and liver disease in humans. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193824.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Camilleri, M, BouSaba, J. New developments in bile acid diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;19:520–37.Search in Google Scholar

29. Bannaga, A, Kelman, L, O’Connor, M, Pitchford, C, Walters, JRF, Arasaradnam, RP. How bad is bile acid diarrhoea: an online survey of patient-reported symptoms and outcomes. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2017;4:e000116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Walters, JRF. Making the diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1974–5. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000962.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Vijayvargiya, P, Gonzalez Izundegui, D, Calderon, G, Tawfic, S, Batbold, S, Camilleri, M. Fecal bile acid testing in assessing patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea: implications for healthcare utilization. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1094–102. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000637.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Karu, N, Deng, L, Slae, M, Guo, AC, Sajed, T, Huynh, H, et al.. A review on human fecal metabolomics: methods, applications and the human fecal metabolome database. Anal Chim Acta 2018;1030:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2018.05.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Delanghe, JR, Van Elslande, J, Godefroid, MJ, Thieuw Barroso, AM, De Buyzere, ML, Maenhout, TM. Colorimetric correcting for sample concentration in stool samples. Clin Chem Lab Med 2025;63:581–6.10.1515/cclm-2024-0961Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Ridlon, JM, Kang, DJ, Hylemon, PB. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res 2006;47:241–59. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.r500013-jlr200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2024-1414).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- The journey to pre-analytical quality

- Manual tilt tube method for prothrombin time: a commentary on contemporary relevance

- Reviews

- From errors to excellence: the pre-analytical journey to improved quality in diagnostics. A scoping review

- Advancements and challenges in high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays: diagnostic, pathophysiological, and clinical perspectives

- Opinion Paper

- Is it feasible for European laboratories to use SI units in reporting results?

- Perspectives

- What does cancer screening have to do with tomato growing?

- Computer simulation approaches to evaluate the interaction between analytical performance characteristics and clinical (mis)classification: a complementary tool for setting indirect outcome-based analytical performance specifications

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Artificial base mismatches-mediated PCR (ABM-PCR) for detecting clinically relevant single-base mutations

- Candidate Reference Measurement Procedures and Materials

- Antiphospholipid IgG Certified Reference Material ERM®-DA477/IFCC: a tool for aPL harmonization?

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- External quality assessment of the manual tilt tube technique for prothrombin time testing: a report from the IFCC-SSC/ISTH Working Group on the Standardization of PT/INR

- Simple steps to achieve harmonisation and standardisation of dried blood spot phenylalanine measurements and facilitate consistent management of patients with phenylketonuria

- Inclusion of pyridoxine dependent epilepsy in expanded newborn screening programs by tandem mass spectrometry: set up of first and second tier tests

- Analytical performance evaluation and optimization of serum 25(OH)D LC-MS/MS measurement

- Towards routine high-throughput analysis of fecal bile acids: validation of an enzymatic cycling method for the quantification of total bile acids in human stool samples on fully automated clinical chemistry analyzers

- Analytical and clinical evaluations of Snibe Maglumi® S100B assay

- Prevalence and detection of citrate contamination in clinical laboratory

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Temporal dynamics in laboratory medicine: cosinor analysis and real-world data (RWD) approaches to population chronobiology

- Establishing sex- and age-related reference intervals of serum glial fibrillary acid protein measured by the fully automated lumipulse system

- Hematology and Coagulation

- Performance of the automated digital cell image analyzer UIMD PBIA in white blood cell classification: a comparative study with sysmex DI-60

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Flow-cytometric MRD detection in pediatric T-ALL: a multicenter AIEOP-BFM consensus-based guided standardized approach

- Impact of biological and genetic features of leukemic cells on the occurrence of “shark fins” in the WPC channel scattergrams of the Sysmex XN hematology analyzers in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Assessing the clinical applicability of dimensionality reduction algorithms in flow cytometry for hematologic malignancies

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Evaluation of sex-specific 0-h high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T thresholds for the risk stratification of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- Retraction

- The first case of Teclistamab interference with serum electrophoresis and immunofixation

- Letters to the Editor

- Is this quantitative test fit-for-purpose?

- Reply to “Is this quantitative test fit-for-purpose?”

- Short-term biological variation of coagulation and fibrinolytic measurands

- The first case of Teclistamab interference with serum electrophoresis and immunofixation

- Imlifidase: a new interferent on serum protein electrophoresis looking as a rare plasma cell dyscrasia

- Research on the development of image-based Deep Learning (DL) model for serum quality recognition

- Interference of hypertriglyceridemia on total cholesterol assay with the new CHOL2 Abbott method on Architect analyser

- Congress Abstracts

- 10th Annual Meeting of the Austrian Society for Laboratory Medicine and Clinical Chemistry (ÖGLMKC)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- The journey to pre-analytical quality

- Manual tilt tube method for prothrombin time: a commentary on contemporary relevance

- Reviews

- From errors to excellence: the pre-analytical journey to improved quality in diagnostics. A scoping review

- Advancements and challenges in high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays: diagnostic, pathophysiological, and clinical perspectives

- Opinion Paper

- Is it feasible for European laboratories to use SI units in reporting results?

- Perspectives

- What does cancer screening have to do with tomato growing?

- Computer simulation approaches to evaluate the interaction between analytical performance characteristics and clinical (mis)classification: a complementary tool for setting indirect outcome-based analytical performance specifications

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Artificial base mismatches-mediated PCR (ABM-PCR) for detecting clinically relevant single-base mutations

- Candidate Reference Measurement Procedures and Materials

- Antiphospholipid IgG Certified Reference Material ERM®-DA477/IFCC: a tool for aPL harmonization?

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- External quality assessment of the manual tilt tube technique for prothrombin time testing: a report from the IFCC-SSC/ISTH Working Group on the Standardization of PT/INR

- Simple steps to achieve harmonisation and standardisation of dried blood spot phenylalanine measurements and facilitate consistent management of patients with phenylketonuria

- Inclusion of pyridoxine dependent epilepsy in expanded newborn screening programs by tandem mass spectrometry: set up of first and second tier tests

- Analytical performance evaluation and optimization of serum 25(OH)D LC-MS/MS measurement

- Towards routine high-throughput analysis of fecal bile acids: validation of an enzymatic cycling method for the quantification of total bile acids in human stool samples on fully automated clinical chemistry analyzers

- Analytical and clinical evaluations of Snibe Maglumi® S100B assay

- Prevalence and detection of citrate contamination in clinical laboratory

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Temporal dynamics in laboratory medicine: cosinor analysis and real-world data (RWD) approaches to population chronobiology

- Establishing sex- and age-related reference intervals of serum glial fibrillary acid protein measured by the fully automated lumipulse system

- Hematology and Coagulation

- Performance of the automated digital cell image analyzer UIMD PBIA in white blood cell classification: a comparative study with sysmex DI-60

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Flow-cytometric MRD detection in pediatric T-ALL: a multicenter AIEOP-BFM consensus-based guided standardized approach

- Impact of biological and genetic features of leukemic cells on the occurrence of “shark fins” in the WPC channel scattergrams of the Sysmex XN hematology analyzers in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Assessing the clinical applicability of dimensionality reduction algorithms in flow cytometry for hematologic malignancies

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Evaluation of sex-specific 0-h high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T thresholds for the risk stratification of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- Retraction

- The first case of Teclistamab interference with serum electrophoresis and immunofixation

- Letters to the Editor

- Is this quantitative test fit-for-purpose?

- Reply to “Is this quantitative test fit-for-purpose?”

- Short-term biological variation of coagulation and fibrinolytic measurands

- The first case of Teclistamab interference with serum electrophoresis and immunofixation

- Imlifidase: a new interferent on serum protein electrophoresis looking as a rare plasma cell dyscrasia

- Research on the development of image-based Deep Learning (DL) model for serum quality recognition

- Interference of hypertriglyceridemia on total cholesterol assay with the new CHOL2 Abbott method on Architect analyser

- Congress Abstracts

- 10th Annual Meeting of the Austrian Society for Laboratory Medicine and Clinical Chemistry (ÖGLMKC)