The European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) has as part of its mission “to be the leading organization of Laboratory Medicine in Europe.” Through leadership, the EFLM strives to enhance patient care and improve outcomes by promoting and improving the scientific, professional and clinical aspects of laboratory medicine. To focus on important aspects in laboratory medicine in which some strategic actions and measures should be taken, the EFLM decided to start a biannual series of conferences. The first edition was held in Milan, Italy, on November 2014. The conference was entitled “Defining analytical performance goals 15 years after the Stockholm conference” as it was considered timely to address the topic of performance specifications both because it was a long time since it was previously addressed and because performance specifications are central for the clinical application of test measurements and are also of vital importance for quality control measures that should be taken in the laboratories. The conference, organized in cooperation with the Centre for Metrological Traceability in Laboratory Medicine (CIRME) of the University of Milan and the Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (IRMM) of the European Commission-Joint Research Centre, was very successful, with 215 participants from 41 different countries, embracing the five continents (the complete list of conference participants is available as electronic Supplementary Material that accompanies the article at http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/cclm.2015.53.issue-6/cclm-2015-0303/cclm-2015-0303.xml?format=INT). The delegates came from clinical laboratories, from EQAS providers and other professional organizations as well as from the in vitro diagnostics (IVD) manufacturers. In this issue of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine all contributions given during the conference are published (the slides of presentations are available online at http://www.efcclm.eu/index.php/educational-material.html).

The Stockholm Conference in 1999 was a landmark in trying to achieve a consensus on how quality specifications should be set and a hierarchy of models was established [1]. In his paper, Callum Fraser gives not only a historic review of the 1999 Conference, where he served as a co-chair, but also a general survey of the history of laboratory quality specifications [2]. He underlines that time has come to revisit this hierarchy, investigating to what extent it is still valid or if it should be modified or expanded, which is the ultimate goal of the EFLM conference.

The conference comprised five sessions. The first three sessions examined the possibility and the pros and cons to base performance specifications on clinical needs, on biological variation data or on state-of-the-art of the measurement procedure, respectively. In their article on behalf of the EFLM Working Group (WG) on Test Evaluation, Horvath et al. [3] discuss the complexity of outcome-related models in a way that allows investigation of the impact of analytical performance on medical decisions and patient management. Whilst it is acknowledged that these types of evaluations are difficult and may not be possible for all measurands in laboratory medicine, the authors consider this approach as the “gold standard” for setting specifications. Next, Per Hyltoft Petersen, another one of the 1999 conference organizers, expanded the discussion to cover the use of simulation studies as a way to model the probability of clinical outcome and the impact of analytical performance upon them [4]. As an example, the influence of analytical performance is investigated for diagnosing of diabetes using hemoglobin A1c and for individuals at risk for coronary heart disease as defined by serum cholesterol concentrations. In another article, Thue and Sandberg address the topic of performance specifications based on how clinicians use laboratory tests [5]. These authors comment, however, that there is a large variability among clinician behaviors that can limit the role of this approach and that it merely reflects the expectations of the clinicians rather than the ultimate specifications that should be set.

The group of Ricos reviews the rationale for using data on biological variation to derive analytical specifications and shares EQAS data from the Spanish program, which employs this approach [6]. Thereafter Carobene describes the heterogeneity of available biological variation data [7]. In general, any time an estimate of intra-individual CV is >33.3%, it is likely an indication that the distribution of the individual variances is not Gaussian and therefore the parametric statistical handling is not appropriate [8, 9]. Despite the questions regarding the reliability of information, this author confirms the importance of a biological variation database that should, however, include only products of appropriately powered studies. On behalf of the EFLM WG on Biologic Variation, Bartlett et al. presents indeed a critical appraisal checklist to enable standardized assessment of papers on biologic variation [10]. The checklist identifies key elements to be reported in this type of studies: method of sample collection, number of subjects and samples, population type, sample analysis and data derivation. This checklist can also be used a guide on how to perform studies on biological variation.

Haeckel and coworkers give us an overview of statistics that may be used to overcome some disadvantages inherent to the model deriving performance specifications from the state-of-the-art of the measurement [11], while Matthias Orth discusses the evolving German experience and the regulation-driven performance criteria in general [12].

The fourth session of the conference discussed performance criteria in different situations. In the paper by Schimmel and Zegers, we read about the need that calibration hierarchies have to be implemented correctly and parameters contributing to measurement uncertainty and systematic bias controlled and eliminated, respectively, by technically improving reference methods and materials [13]. Panteghini and his group describe the criteria behind the definition of allowable limits for measurement uncertainty across the entire traceability chain [14]. IVD manufacturers will need to take more responsibility and report the combined (expanded) uncertainty associated with their calibrators when used in conjunction with other components of the analytical system (platform and reagents). This is more than what they are currently providing as information; typically they only provide the name of the higher order reference to which the calibration is traced. Ceriotti et al. discuss how to define a significant deviation in the internal quality control (IQC) practice by transferring uncertainty calculations onto the IQC chart [15]. Jones notes that there is an embarrassing variation in the performance specifications being used by EQAS providers, which needs harmonization through a collaborative effort [16]. Oosterhuis and Sandberg present a model that combines the “state-of-the-art” with biological variation for the calculation of performance specifications. The validity of reference limits and reference change values are central to this model [17]. In addition, they remind the readers that the estimation of total error by adding the performance specification for maximum allowable imprecision and maximum allowable bias is in principle not valid. Nordin addresses “qualitative” laboratory tests and help to clarify that performance specifications for nominal examination procedures must be set with respect to the type of test [18].

Final articles of this series by the Plebani’s group [19] and Sikaris [20] cover the remaining parts of the total examination process (i.e., pre- and post-analytical phases), highlighting the limitations that still hamper the use of quality performance specifications in these parts of laboratory processes.

In this Special Issue the Scientific Programme Committee of the conference publishes a consensus statement that was elaborated in a draft form before the conference and distributed to all the participants for further discussion [21]. Although the essence of the hierarchy originally established in 1999 was supported, new perspectives have been forwarded prompting simplification and explanatory additions. Basically, the recommended approaches for defining analytical performance specifications should rely on the effect of analytical performance on clinical outcomes or on the biological variation of the measurand. The attention is primarily directed towards the measurand and its biological and clinical characteristics, some models being therefore better suited for certain measurands than for others. About the pre- and post-analytical phases, it is time to go further and to include performance specifications for these extra-analytical phases. The specifications should ideally follow the same models as the analytical phase.

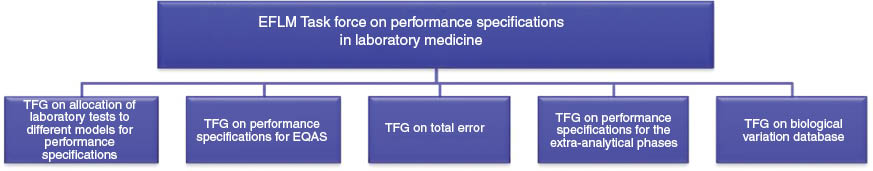

The main outcome of the conference has been the creation of an EFLM Task Force (TF) on Performance Specifications in Laboratory Medicine (TF-PS). Under the TF-PS five Task and Finish Groups (TFG) have been established dealing with the main topics of the conference (Figure 1). The terms of reference of the TFG are the following:

TFG 1: To allocate different tests to different models recognized in the Strategic Conference consensus statement and to give an overview and a reason for why tests are allocated to the different models;

TFG 2: To define performance specifications for the most common measurands that should be used by EQAS organizers (for category I EQAS according to Miller et al. [22]);

TFG 3: To come up with a proposal for how to use the total error concept and how to possible combine performance specifications for bias and imprecision;

TFG 4: To come up with a general proposal on how to generate performance specifications for the pre- and post-analytical phases;

TFG 5: To use a critical appraisal list to evaluate literature on biological variation and extract essential information from the papers as well as summarizing the selected information on a database on the EFLM website.

Structure of the EFLM task force on performance specifications in laboratory medicine.

Acknowledgments

The Conference was generously and unconditionally supported by Abbott Diagnostics, Bio-Rad, DiaSorin, Roche Diagnostics and Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Financial support: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Kallner A, McQueen M, Heuck C. The stockholm consensus conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine, 25–26 April 1999. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999;59:475–585.10.1080/00365519950185175Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Fraser CG. The 1999 Stockholm Consensus Conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:837–40.10.1515/cclm-2014-0914Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Horvath AR, Bossuyt PM, Sandberg S, St John A, Monaghan PJ, Verhagen-Kamerbeek WD, et al. Setting analytical performance specifications based on outcome studies – is it possible? Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:841–8.10.1515/cclm-2015-0214Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Petersen PH. Performance criteria based on true and false classification and clinical outcomes. Influence of analytical performance on diagnostic outcome using a single clinical component. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:849–55.10.1515/cclm-2014-1138Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Thue G, Sandberg S. Analytical performance specifications based on how clinicians use laboratory tests. Experiences from a post-analytical external quality assessment programme. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:857–62.10.1515/cclm-2014-1280Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Ricós C, Álvarez V, Perich P, Fernández-Calle P, Minchinela J, Cava F, et al. Rationale for using data on biological variation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:863–70.10.1515/cclm-2014-1142Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Carobene A. Reliability of biological variation data available in an online database: need for improvement. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:871–7.10.1515/cclm-2014-1133Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Braga F, Ferraro S, Lanzoni M, Szoke D, Panteghini M. Estimate of intraindividual variability of C-reactive protein: a challenging issue. Clin Chim Acta 2013;419:85–6.10.1016/j.cca.2013.02.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Braga F, Ferraro S, Ieva F, Paganoni A, Panteghini M. A new robust statistical model for interpretation of differences in serial test results from an individual. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:815–22.10.1515/cclm-2014-0893Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Bartlett WA, Braga F, Carobene A, Coşkun A, Prusa R, Fernandez-Calle P, et al. A checklist for critical appraisal of studies of biological variation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:879–85.10.1515/cclm-2014-1127Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Haeckel R, Wosniok W, Streichert T. Optimizing the use of the ‘state-of-the-art’ performance criteria. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:887–91.10.1515/cclm-2014-1201Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Orth M. Are regulation-driven performance criteria still acceptable? - The German point of view. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:893–8.10.1515/cclm-2014-1144Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Schimmel H, Zegers I. Performance criteria for reference measurement procedures and reference materials. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:899–904.10.1515/cclm-2015-0104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Braga F, Infusino I, Panteghini M. Performance criteria for combined uncertainty budget in the implementation of metrological traceability. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:905–12.10.1515/cclm-2014-1240Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Ceriotti F, Brugnoni D, Mattioli S. How to define a significant deviation from the expected internal quality control result. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:913–8.10.1515/cclm-2014-1149Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Jones GR. Analytical performance specifications for EQA schemes – need for harmonisation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:919–24.Search in Google Scholar

17. Oosterhuis WP, Sandberg S. Proposal for the modification of the conventional model for establishing performance specifications. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:925–37.Search in Google Scholar

18. Nordin G. Before defining performance criteria we must agree on what a “qualitative test procedures” is. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:939–41.10.1515/cclm-2015-0005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Plebani M, Sciacovelli L, Aita A, Pelloso M, Chiozza ML. Performance criteria and quality indicators for the pre-analytical phase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:943–8.10.1515/cclm-2014-1124Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Sikaris K. Performance criteria of the post-analytical phase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:949–58.10.1515/cclm-2015-0016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Sandberg S, Fraser C, Horvath AR, Jansen R, Jones G, Oosterhuis W, et al. Defining analytical performance specifications: consensus statement from the 1st Strategic Conference of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:833–5.10.1515/cclm-2015-0067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Miller WG, Jones GR, Horowitz GL, Weykamp C. Proficiency testing/external quality assessment: current challenges and future directions. Clin Chem 2011;57:1670–80.10.1373/clinchem.2011.168641Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplemental Material

The online version of this article (DOI: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0303) offers supplementary material, available to authorized users.

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Defining analytical performance specifications 15 years after the Stockholm conference

- Consensus Statement

- Defining analytical performance specifications: Consensus Statement from the 1st Strategic Conference of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Opinion Papers

- The 1999 Stockholm Consensus Conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine

- Setting analytical performance specifications based on outcome studies – is it possible?

- Performance criteria based on true and false classification and clinical outcomes. Influence of analytical performance on diagnostic outcome using a single clinical component

- Analytical performance specifications based on how clinicians use laboratory tests. Experiences from a post-analytical external quality assessment programme

- Rationale for using data on biological variation

- Reliability of biological variation data available in an online database: need for improvement

- A checklist for critical appraisal of studies of biological variation

- Optimizing the use of the “state-of-the-art” performance criteria

- Are regulation-driven performance criteria still acceptable? – The German point of view

- Performance criteria for reference measurement procedures and reference materials

- Performance criteria for combined uncertainty budget in the implementation of metrological traceability

- How to define a significant deviation from the expected internal quality control result

- Analytical performance specifications for EQA schemes – need for harmonisation

- Proposal for the modification of the conventional model for establishing performance specifications

- Before defining performance criteria we must agree on what a “qualitative test procedure” is

- Performance criteria and quality indicators for the pre-analytical phase

- Performance criteria of the post-analytical phase

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Defining analytical performance specifications 15 years after the Stockholm conference

- Consensus Statement

- Defining analytical performance specifications: Consensus Statement from the 1st Strategic Conference of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Opinion Papers

- The 1999 Stockholm Consensus Conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine

- Setting analytical performance specifications based on outcome studies – is it possible?

- Performance criteria based on true and false classification and clinical outcomes. Influence of analytical performance on diagnostic outcome using a single clinical component

- Analytical performance specifications based on how clinicians use laboratory tests. Experiences from a post-analytical external quality assessment programme

- Rationale for using data on biological variation

- Reliability of biological variation data available in an online database: need for improvement

- A checklist for critical appraisal of studies of biological variation

- Optimizing the use of the “state-of-the-art” performance criteria

- Are regulation-driven performance criteria still acceptable? – The German point of view

- Performance criteria for reference measurement procedures and reference materials

- Performance criteria for combined uncertainty budget in the implementation of metrological traceability

- How to define a significant deviation from the expected internal quality control result

- Analytical performance specifications for EQA schemes – need for harmonisation

- Proposal for the modification of the conventional model for establishing performance specifications

- Before defining performance criteria we must agree on what a “qualitative test procedure” is

- Performance criteria and quality indicators for the pre-analytical phase

- Performance criteria of the post-analytical phase