Abstract

This article presents a comprehensive numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests designed for women. The study involved a woman aged between 24 and 28 with a breast size of 85C. Two ballistic packages made from Twaron® CT 709 fabric were designed and constructed for her, featuring cut-and-sew formed breast cups and differing significantly in the number of layers (16 and 30 layers). The impact of the number of layers on breast deformation during the shooting was analyzed using numerical modeling and experiments, which included a Parabellum 9 mm × 19 mm FMJ® bullet and a Roma No. 1 plasticine substrate formed based on a plaster cast representing a woman’s figure. The research found that even significantly increasing the number of layers in the ballistic package did not lead to a substantial reduction in breast deformation during shooting. The likely reason for this is the cut-and-sew formed breast cups in the ballistic package, which easily undergo transverse deformation upon bullet impact. This suggests a need for further research to optimize the design of protective cups, which are crucial for proper force distribution and minimizing injuries during bullet impact. The conclusions drawn from this study could contribute to the development of more advanced and effective soft ballistic protection solutions for women.

1 Introduction

A bulletproof vest is an essential piece of equipment for police officers, soldiers involved in military missions, VIPs, and security personnel, particularly those working in various countries under Specialist Armed Protective Formations [1,2]. For example, in Poland, such formations operate based on the Act of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland dated August 22, 1997, on the protection of persons and property. According to the act, Specialist Armed Protective Formation is a specialized unit established within a company providing services in the field of protection of persons and property. In many cases, bulletproof vests provide life-saving protection, reduce the risk of serious injuries, and enhance the sense of security among personnel, thereby improving their work efficiency.

It should be noted that, depending on the country, and particularly the prevailing cultural and religious conditions, women make up a varying proportion of uniformed service personnel. They generally perform the same work and have the same duties as men. Over the years, the presence of women in these services, which were historically reserved exclusively for men, has increased. In Europe, the percentage of women in police forces varies by country but averages around 20%. The number of women in European uniformed services is growing, driven by efforts to promote gender equality and increase female representation in these fields. In Poland, the percentage of women applying to join the police force increased from 31.10% in 2019 to 38.95% in 2022. There is also an upward trend in the number of women serving in the police force, from 17.74% of the total workforce in 2019 to 24.28% in 2022 [3,4,5,6]. In the United States, available statistics for the participation of women in law enforcement from 1987 to 2008 show a slight increase, with the percentage of women in federal law enforcement rising from 14% in 1998 to 15.2% in 2008, with the highest percentage (25%) in the Offices of Inspectors General. Large federal agencies (with more than 500 officers) had an average percentage of women at 21%. In 2007, women made up about 12% of the officers in local police departments and sheriff’s offices, and a similar percentage in state law enforcement agencies. Smaller federal agencies had a much lower percentage of women, around 9% in 2008 [7]. In the military, the proportion of women varies by country. In the United States, women make up about 16% of the armed forces. As of March 1, 2024, women in all branches of the Polish Armed Forces accounted for about 13% of all soldiers [8]. In the private sector, including VIP security, the number of women working as security personnel is lower, usually in the single-digit percentage range, but they perform the same tasks as men and are also required to wear appropriate protective equipment, including bulletproof vests.

Common protective fabrics used in soft bulletproof vests are typically made from para-aramid fibers like Kevlar® or Twaron®, or high-performance polyethylene fibers such as Dyneema® or Spectra®. When designing a bulletproof vest, special attention must be paid to tailoring the construction to the individual needs of the user. This issue becomes particularly important when designing protective clothing for women. The increasing presence of women in uniformed services makes it increasingly important to provide them with appropriate equipment and specialized protective clothing due to anatomical differences from men [9,10]. Soft bulletproof vests designed for women differ from those for men in that they may include formed protective cups tailored to accommodate the female bust. Flat vest models designed for men may be considered for women with smaller busts but should generally not be used for women with larger busts. This is because they push the front panel of the vest forward, significantly reducing comfort by creating gaps between the vest and the woman’s body due to the misfit [11]. Studies show that bulletproof vests worn by women are generally not well-suited to their anatomy, leading to reduced ballistic effectiveness and restricted mobility [1]. When a bulletproof vest is not properly fitted to the wearer, it can also result in decreased comfort and lower work quality. Research and workshops conducted in the United States with female police officers by the Criminal Justice Technology Testing and Evaluation Center indicate that over 60% of the participants reported never having a well-fitted bulletproof vest. Most participants indicated that their current vests are not properly fitted and cause chafing, pain, numbness, and other discomforts [12].

For this reason, when designing bulletproof vests for women, the ballistic fabric should be shaped to ensure optimal comfort, which generally involves tailoring it to the specific anthropometric measurements of an individual woman or a group of women with similar body shapes. Consequently, the design of bulletproof vests for women is more complex than that for men. This complexity arises from the anatomical structure of women [13,14]. For men, significantly fewer anthropometric measurements are required to determine the vest design compared to women. The vest must conform to the shape of a woman’s body, fitting snugly without causing discomfort. The result is a product tailored to specific measurements, closely fitting the user’s body shape. This approach enables the achievement of optimal results in terms of user comfort while ensuring the appropriate level of protection. It is the designers’ task to develop the most suitable solution in the construction of bulletproof vests to meet each user’s needs [15,16].

Modern 3D clothing design techniques allow for the creation of women’s bulletproof vests based on a 3D scan of a woman, using reverse engineering methods. 3D clothing design offers numerous benefits, such as a better-fitting product and optimization of raw materials during the clothing creation process [17,18]. The primary technique for shaping cups at the bust line in bulletproof vests is the dart rotation technique. This technique ensures a good fit of the ballistic panel to the woman’s body, providing appropriate comfort while maintaining ballistic effectiveness [19]. An interesting approach to forming the soft ballistic package for women is the creation of cups using molds that replicate the shape of the right and left breasts of a specific size. This process allows for the creation of a three-dimensional cup shape in the flat layers of the ballistic package without the need for stitching. A single layer of the package is placed between the lower and upper molds and compressed with a specific pressure. Published studies indicate that further research is necessary to effectively form cups in various types of ballistic materials and to conduct experimental studies to evaluate the effectiveness of such shaped bulletproof vests for women [20,21,22].

An important aspect of manufacturing bulletproof vests for women is the testing procedures for their ballistic effectiveness. Bulletproof vests for men feature flat ballistic panels, and their ballistic effectiveness is tested by placing them on a flat standardized plasticine substrate and shooting at them according to a set procedure based on the intended ballistic resistance level [23]. In the case of bulletproof vests designed for women, they contain unique seams and curves that are not present in men’s vests. On the other hand, vests designed to fit the female body can have highly varied dimensions of the formed cups. Currently, bulletproof vests for women with molded cups are being tested based on the latest update of the NIJ Standard No. 0101.07 and the procedures outlined in Appendix G [23]. The standard specifies the need to locate seams, folds, and other elements shaping the breast, as well as defines shooting conditions, such as the position, angle, and direction of fire. Shots from 1 to 6 should be carried out in accordance with ASTM E3107 [24]. The National Institute of Justice Compliance Testing Program (NIJ CTP) provides electronic files that allow for shaping the Roma No. 1 plasticine backing according to the woman’s size: small, medium, and large. Research is ongoing to develop a standardized range of bust sizes and shapes for potential use in testing [11].

When designing bulletproof vests for women, medical aspects are also crucial. The frequency of blunt breast injuries from non-penetrating bullet impacts is unknown, and there are no established treatment guidelines [25]. Blunt breast trauma can result in various injuries depending on the kinetic energy (KE) involved – the higher the energy, the more severe the consequences. With low KE, superficial injuries such as abrasions, minor bruises, and contusions affecting only the skin and subcutaneous tissue layers can occur. At higher energy levels, bruises and contusions can cover a larger area, including deeper layers of the breast tissue. With very high KE, a laceration may occur. It should be noted that damage to the glandular tissue can also lead to issues with lactation and breastfeeding. Breast injuries from bullet impacts are often unrecognized or considered insignificant from a medical standpoint. This is a misconception, as breast area injuries can be a significant source of bleeding, leading to serious complications such as hemorrhagic shock and even death. Interestingly, women admitted to hospitals with penetrating injuries such as gunshot wounds, stab wounds, or lacerations had a better survival rate than those admitted with only visible superficial injuries like abrasions and bruises. This is because the latter injuries were often underestimated, leading to a lack of thorough examination and missed internal injuries [26]. Typically, breast injuries do not require surgical intervention. Surgical necessity is more common with penetrating injuries, although paradoxically, mortality is higher with blunt injuries, which often appear less severe initially than injuries with a breach in the skin’s integrity [27]. Additionally, the possibility of breast implant damage during a non-penetrating bullet impact should be considered. Many women choose breast augmentation with implants at various stages of life. Breast implants usually consist of a silicone shell filled with either silicone gel (silicone implants) or saline solution (saline implants). These implants can rupture under high KE, causing their contents to leak into surrounding tissues.

Bulletproof vests specifically designed for women, featuring formed cups, can offer significantly more comfort for everyday use. However, when a bullet strikes the cup area, the material, due to its curvature, can easily undergo transverse deformation. This type of deformation poses a risk of serious breast injuries because instead of evenly dispersing the bullet’s energy by stretching the warp and weft threads around the impact point, the ballistic panel layers tend to deform inward toward the body. This can result in the concentration of stress on a small area. Such deformation can lead to excessive transverse deformation of the ballistic panel despite stopping the bullet, potentially causing severe injuries, such as tissue crushing or even internal injuries to the mammary glands.

These issues have not been thoroughly analyzed before. Therefore, the primary objective of the presented work was to evaluate the ballistic effectiveness of a women’s soft body armor vest made from ballistic panels consisting of 16 and 30 layers of high-strength Twaron® CT 709 fabric. By significantly varying the number of layers in the ballistic panels, the study aimed to determine whether there would be a substantial decrease in transverse deformation of the panel during bullet impact as the number of layers increased, or if this had a limited effect on the level of transverse deformation of the cup. The ballistic panels were designed based on a basic blouse pattern and the transfer of a dart at a fixed angle, allowing for a fit that matches female anatomy. The methodology for numerical studies involved modeling the vest on a 3D virtual model of a woman obtained through scanning. Experimental verification of the ballistic effectiveness of the panels was conducted using an identical model of a woman made from standardized ballistic clay Roma No. 1.

The tests utilized a 9 mm × 19 mm FMJ® Parabellum bullet, which struck the center of the breast at a velocity of approximately 380 ± 3 m/s. The results were analyzed concerning maximum deformation, energy balance, and potential physiological effects of the ballistic impact.

2 Materials

The soft ballistic panels were made from Twaron® CT 709 Microfilament 930 dtex f1000 fabric (Teijin®, Japan) [28]. This fabric is made of para-aramid yarn Twaron® 2040 Microfilament with a linear density of 930 dtex, containing 1,000 filaments in the cross-section. The basic construction parameters of this fabric are presented in Table 1. Twaron® 840 dtex x1 Z160 thread (Teijin®, Japan) was used for stitching the individual layers of the ballistic panel and the darts. The outer shell of the bulletproof vest was made from Cordura® fabric (DuPont, USA) constructed from ballistic nylon.

Construction parameters of Twaron CT 709 fabric [28]

| Twaron fabric type | Fabric weave type | Warp density (yarns/dm) | Weft density (yarns/dm) | Areal density (g/m²) | Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT709 | Plain 1/1 | 105 | 105 | 200 | 0.3 |

3 Methods

3.1 Assumptions for numerical and experimental research

The ballistic performance evaluation of a bulletproof vest designed for women was conducted using numerical simulations in LS-Dyna software and experimental testing in the Ballistic Research Laboratory. The following assumptions were made: (1) The soft ballistic package protecting the chest area of a woman would be designed based on a model of a basic female blouse with a bust dart rotated by a fixed angle of 10.5°. (2) The ballistic effectiveness of the soft ballistic package would be assessed for packages consisting of 16 and 30 layers of Twaron® CT 709 Microfilament 930 tex f1000 fabric, both in numerical and experimental tests. A package containing 16 layers of these fabrics was selected to ensure the non-penetrating impact of a 9 × 19 Parabellum FMJ bullet at the velocity used in the experiments [29], while also allowing for significant deformation of the package, resulting in substantial breast deformation. By significantly varying the number of layers from 16 to 30 in the ballistic panels, the study aimed to determine whether there would be a substantial decrease in transverse deformation of the panel during bullet impact as the number of layers increased, or if this had a limited effect on the level of transverse deformation of the cup. (3) The ballistic packages were tested by shooting 9 mm × 19 mm Parabellum FMJ® bullets at an impact velocity of 380 ± 3 m/s, in accordance with the NIJ Standard 0101.06 [30], performance level Type IIA, for new and unworn bulletproof vests. According to this standard, bulletproof vests at this level must be tested with 9 mm Parabellum FMJ RN bullets at a velocity of 373 ± 9.1 m/s. The bullet velocities used in the tests were generally within the range specified by the standard.

3.2 Methodology of numerical research

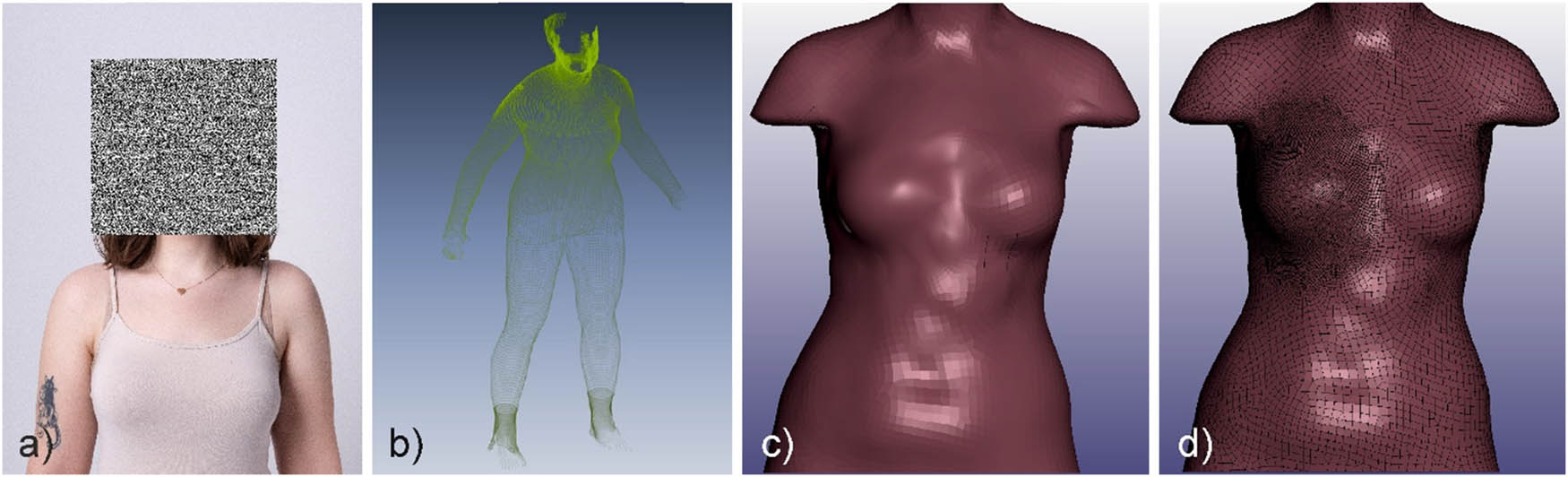

The numerical model of the woman was created based on data obtained from the scanning process of a representative woman with a larger bust, aged between 24 and 28 years (Figure 1a), using the TC2 NX 16 3D scanner (USA). Figure 1b shows the point cloud obtained from the scanning process.

Numerical modeling of the female body: (a) view of the woman selected for the study, (b) 3D point cloud obtained after the scanning process, (c) geometric model, and (d) numerical model.

A geometric model of the woman’s body was created using Geomagic Design X software, which includes reverse engineering tools and is designed to create 3D models directly from the data obtained from the 3D scanning process. For the purpose of the simulation study, the geometric model of the woman’s body was restricted to the neckline to the hip line (Figure 1c). This allowed the number of finite elements in the final numerical model to be reduced. In a further step, a finite element mesh was generated in Ansys Meshing software, which was compacted in the right breast area. A Hexa/Solid mesh type was used with a finite element dimension of 2 mm at a radius of 120 mm from a central point on the breast (Figure 1d). Outside the area of mesh compression, the finite element dimension was 10 mm.

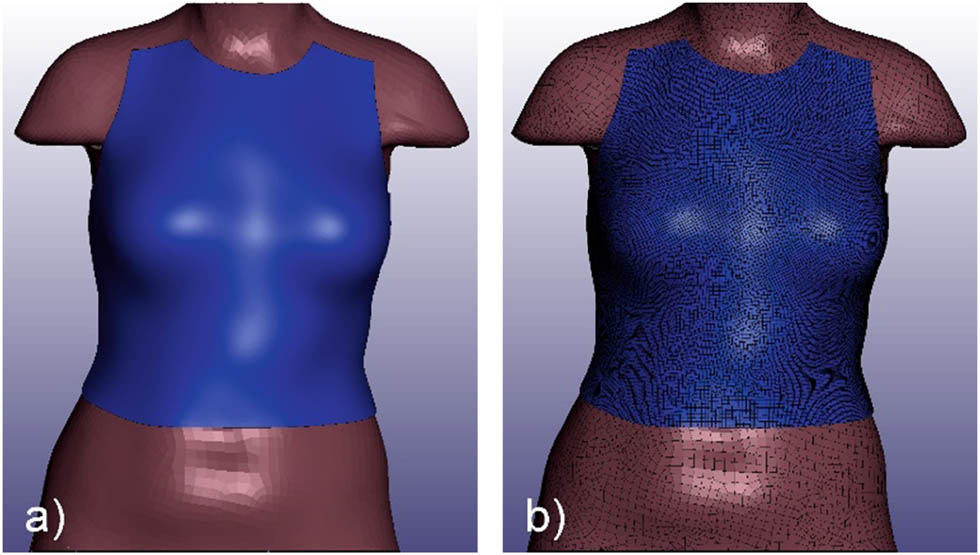

The development of the geometric model of the layers of the ballistic package involved making a form of the front of the vest in Geomagic Design X software. This program made it possible to generate the surface of the geometric model well suited to the anatomy of a woman’s body. The individual layers of the vest were modeled as shells, which were graded by a design allowance of 5 mm. The geometric model consisted of 16 and 30 layers, respectively. Figure 2a shows the geometric model of the first layer of the ballistic package.

Modeling of the first layer of the ballistic package: (a) geometric model and (b) numerical model.

Each layer of the package was discretized by generating a Hexa/Shell finite element mesh with a finite element dimension of 2 mm (Figure 2b). This value was selected based on preliminary simulation studies, which involved increasing the mesh dimensions and evaluating the convergence of breast deformation at the point of bullet impact over time.

A model of the Parabellum 9 mm × 19 mm FMJ® bullet was made based on the dimensions provided by the manufacturer [31,32,33]. The caliber of the bullet is 9 mm, and the shell length is 19.15 mm. It is currently the most popular pistol bullet in the world and is used in most police and military weapons. The numerical model of the bullet had a Tetra/Solid finite element mesh with an element edge dimension of 0.2 mm.

Numerical studies were carried out in LS-Dyna software. The numerical model consisted of 1,084,617 finite elements for 16 layers and 1,736,277 for 30 layers, respectively. The first step was to define the contacts between the layers. For this purpose, the contact type AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE was adopted while taking into account the dynamic and static friction coefficients between: adjacent layers µd = 0.10, µs = 0.10; shell and bullet core µd = 0. 80, µs = 0.80; shell and successive layers µd = 0.28, µs = 0.30; shell core and successive layers µd = 0.28, µs = 0.30; and layers and female model µd = 0.10, µs = 0.10 [34,35,36,37]. In the next step, we proceeded to adopt the corresponding material parameters for the woman model, the layers of the ballistic package, and the bullet. For the female model, *MAT_POWER_LAW_PLASTICITY [31,38] was adopted. The anisotropic properties of the linen weave fabric were obtained by adopting the material model *MAT_ORTHOTROPIC_ELASTIC dedicated to shell structures. The material coordinates within the finite elements were oriented so that the “a” coordinate corresponded to the direction of the warp threads and the “b” coordinate corresponded to the direction of the weft threads while the “c” coordinate corresponded to the thickness of the layer. This model is typically used in simulation studies of bullet impact on a ballistic package made of fabrics [39,40,41,42]. The strength parameters of Twaron® CT 709 fabric for the adopted model are shown in Table 2 [43,44,45,46,47].

Parameter values for the material model *MAT_ORTHOTROPIC_ELASTIC adopted for the layers of the ballistic package [43,44,45,46,47]

| Density RO (kg/m3) | Young’s modulus E a (GPa) | Young’s modulus E b (GPa) | Young’s modulus E c (GPa) | Poisson’s ratio PR | Yield strength SIGY (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,440 | 80 | 80 | 2.34 | 0.3 | 3.6 |

For the lead core (Table 3) and the ballistic brass (Table 4) jacket of the 9 mm × 19 mm Parabellum FMJ® bullet, the same material model *MAT_SIMPLIFILED_JOHNOSN_COOK [31,32,33,48] was adopted. The parameter values for these material models were taken from previous studies [32,48].

3.3 Methodology of experimental research

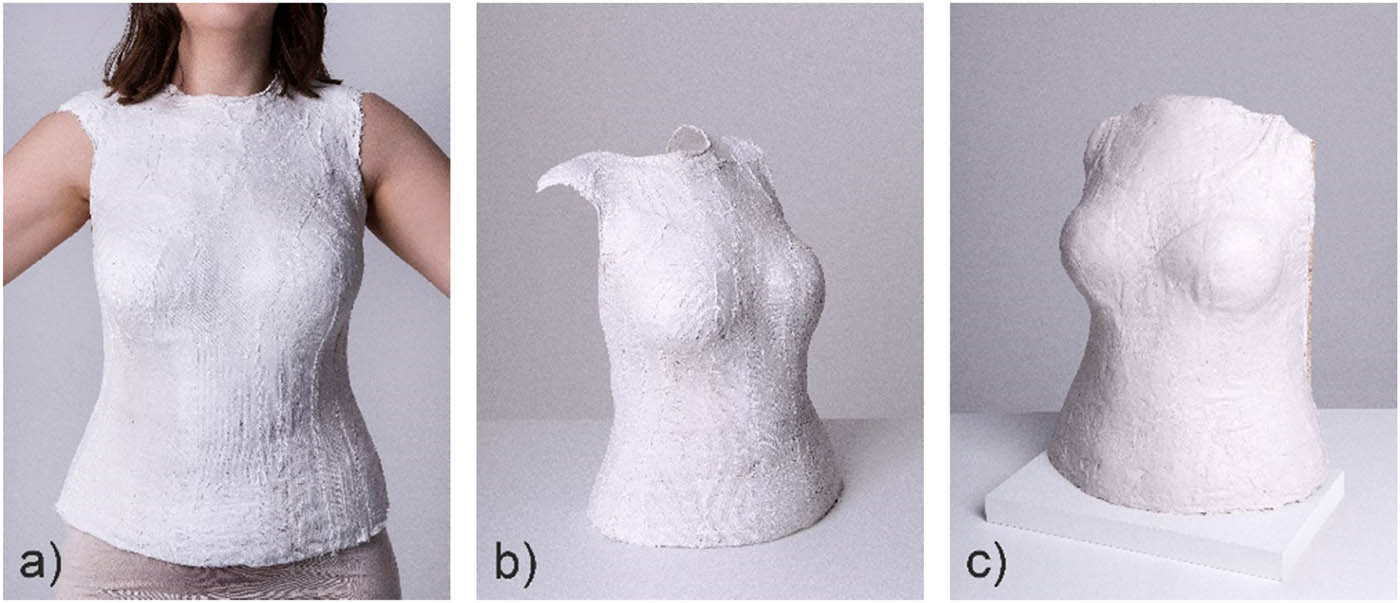

To obtain compatibility between the numerical model and the ballistic background with the female anatomy, a plaster cast mold of the same person’s chest was made. The study began by applying plaster bandages to the woman’s chest (Figure 3a). After drying, they were gently removed from the woman. The effect of the final mold is shown in Figure 3b. After the plaster mold was made, it was then filled with Roma No. 1 ballistic plasticine. The ballistic substrate met the requirements of the NIJ standard [30]. The filled mold of the ballistic plasticine (Figure 3c) was annealed for 24 h at an appropriately selected temperature so as to achieve the deformability of the plasticine as defined in the NIJ standard [30].

Modeling of the front plaster mold: (a) applied plaster bandages on the woman’s chest, (b) finished plaster mold of the front of the woman’s chest, and (c) ballistic substrate corresponding to the woman’s anatomy.

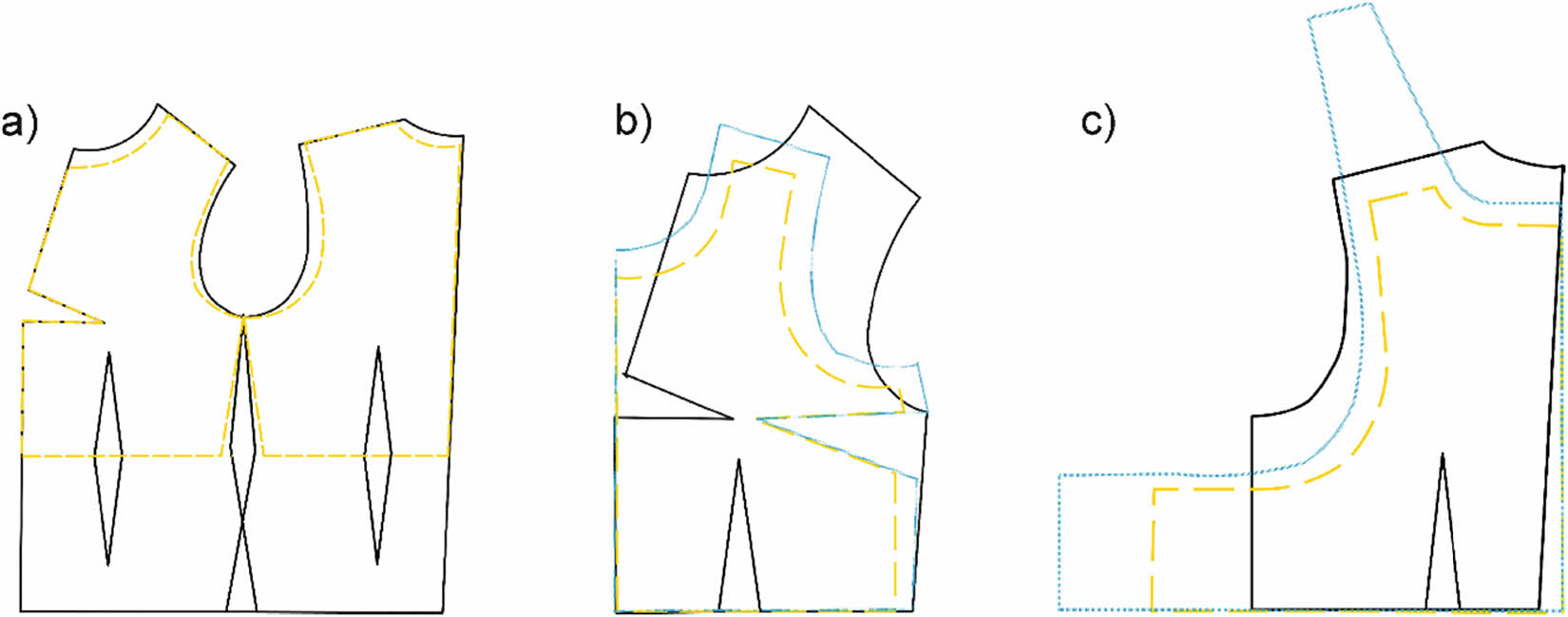

The construction of the bulletproof vest along with the soft ballistic insert was made based on the standard of women’s blouse construction [49,50]. In the first stage, anthropometric measurements were taken of the woman participating in the study. According to the tables of body measurements, which define typological groups, the potential wearer was classified into type B with a size S and a bust size of 85C [49,50]. The development of the form of a vest with a soft ballistic insert was carried out using the method of modeling the basic form of a women’s blouse, that is, matching the form of the blouse structure to the physical structure of a person and to the cut resulting from the nature of the garment, taking into account the confectionary properties of the materials used (Figure 4a). To obtain a template for the soft ballistic insert (yellow color), the following modifications were made to the basic blouse construction (black color): (1) the template construction was shortened to the waistline, (2) the neckline was modeled, (3) the underarm cut was deepened, and (4) the waist darts were reduced. After making changes to the basic template, a template for the front (Figure 4b) and back (Figure 4c) was developed as a concept for a bulletproof vest for women – including a template for the soft ballistic insert (yellow color) and the outer part of the vest (blue color).

Construction of ballistic insert templates: (a) modifications to the construction grid of the women’s basic blouse, (b) template of the front of the ballistic insert and cover, and (c) template of the back of the ballistic insert and cover.

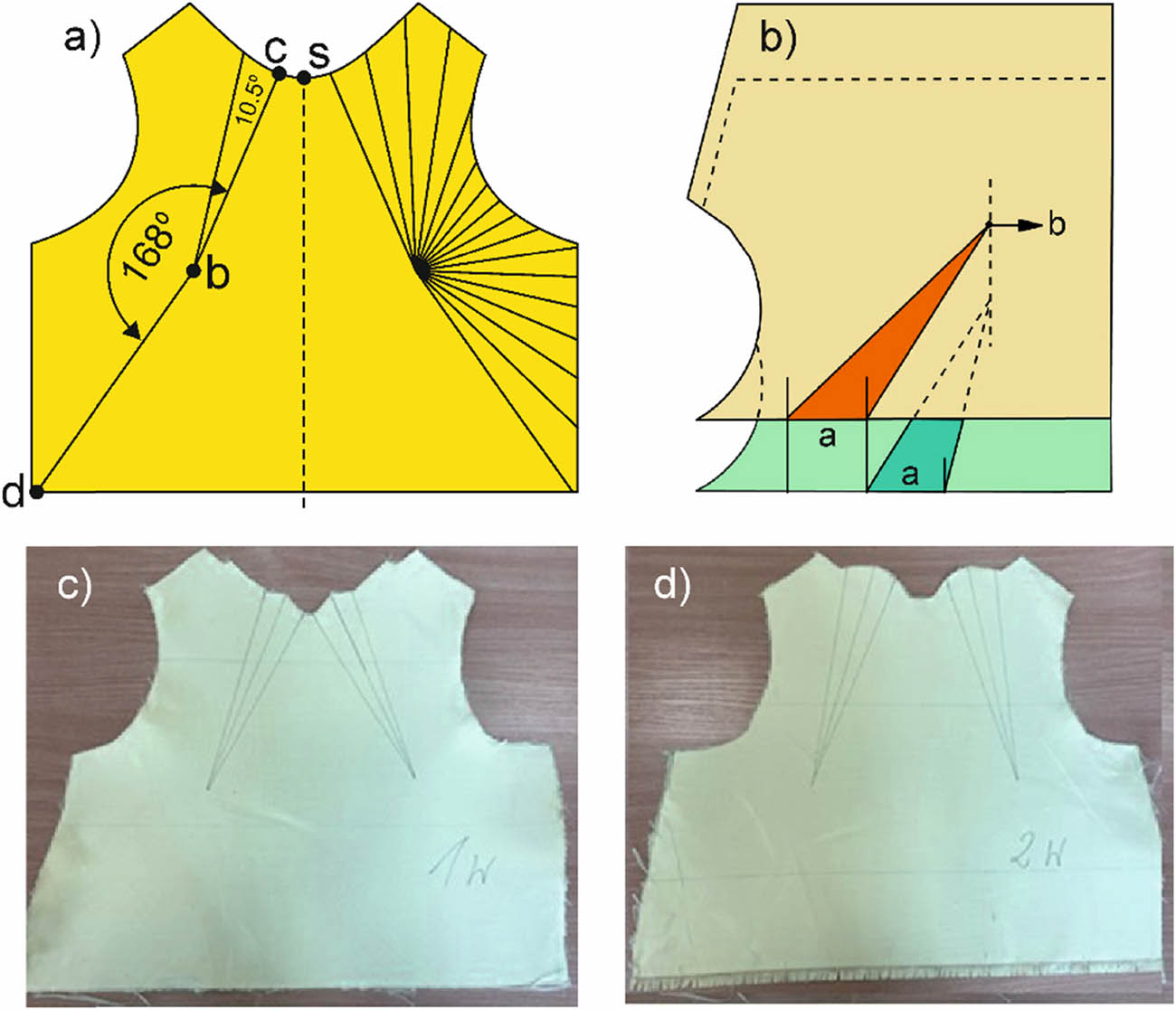

After making the necessary modifications to match the dimensions of the basic template with those designed for the layers of the ballistic panel, individual templates were developed for each layer of the ballistic package. Each layer of the panel was placed in a specific order the seams to fit the shape of the product to the body. The darts were made to overlap, resulting in two additional layers of material, giving additional layers of protective surfaces. It was determined that the position of the first dart, marked as point c in Figure 5a, was shifted 0.5 cm from the centerline of the package layer pattern (point s) as a construction allowance. It was also assumed that the position of the last dart would be located in the lower corner of the pattern (point d) so that no darts would be placed in the waistline area, i.e., the abdominal area. In this way, the area of the pattern containing all the darts was limited by segments cb and bd, with an angle of 168° between them. The division of this area into 16 darts was adopted, which required rotating the subsequent darts by an angle of 10.5°. The method of moving the darts for the two consecutive layers is shown in Figure 5b. Where the first dashboard (orange color) in the first layer (yellow color) of the ballistic panel ends, another dashboard in the second layer (green color) begins. The darts were displaced at an angle of 10.5°, the value a corresponded to the width of the darts, the point b – the point of the nipple. In this way, the dampers in each of the layers forming the ballistic panels were moved sequentially. A separate template was made for each layer of the package. These templates were then used to cut out the correct blanks of each layer of the ballistic package, the first layer (Figure 5c) and the second layer (Figure 5d). In the next step, the process of confectioning a soft ballistic package consisting of 16 and 30 layers was started. For each of the tested packages, two pieces were prepared.

Design of breast cup shaping darts: (a) idea of determining the position of darts, (b) positions of the darts in the next two layers of the ballistic packet, (c) cut view of the first layer of the packet, and (d) cut view of the second layer of the packet.

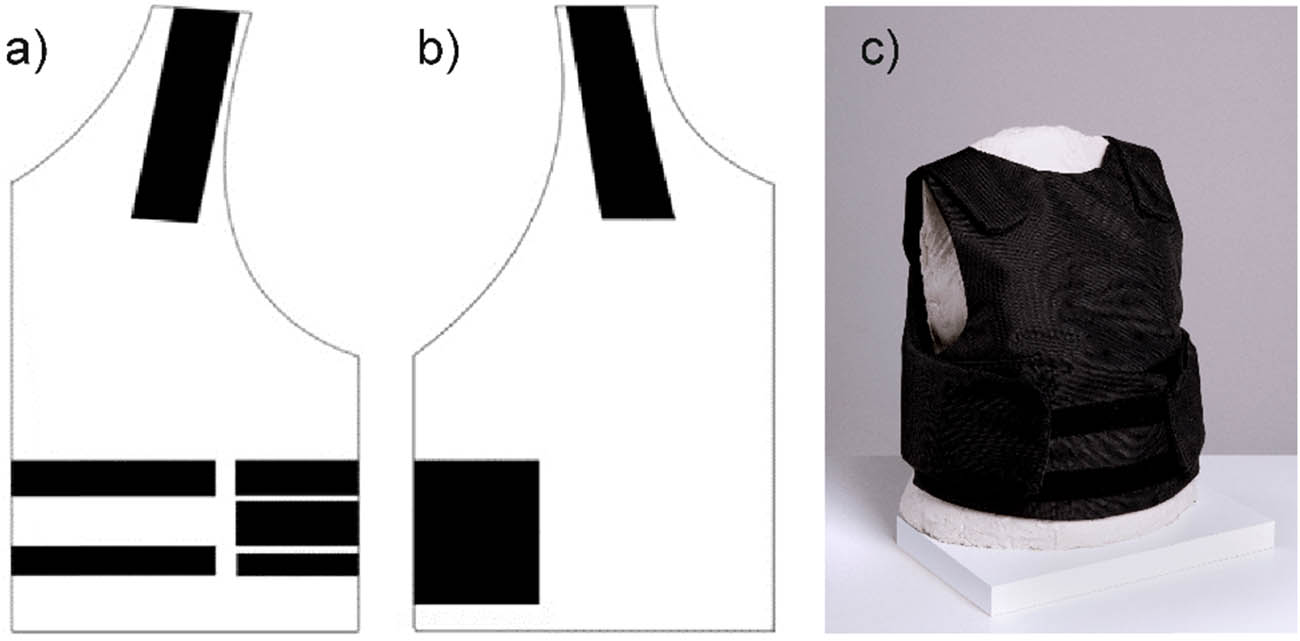

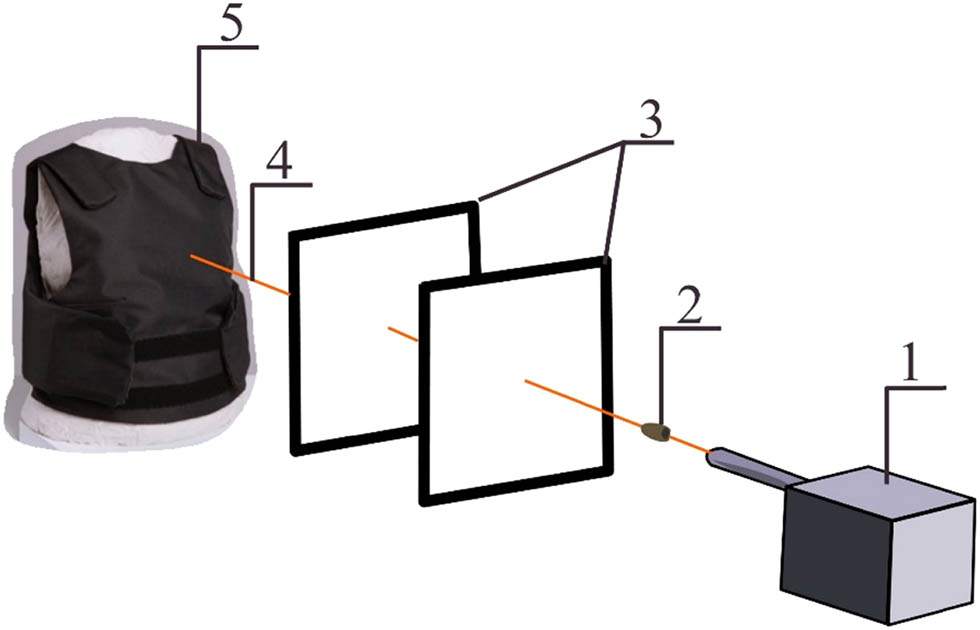

The outer part of the vest was a weaving called Cordura®, made of polyamide fibers and permanently coated with Teflon, which prevents the entry of moisture. The form of the front (Figure 6a) and back (Figure 6b) of the plating was modeled based on the previously prepared basic design of a women’s blouse. The front panel of the vest had a pocket at the bottom, which allowed the replacement of the ballistic pack. Velcro was introduced at the shoulders and waist, which allowed the vest to be adjusted to the ballistic base. Figure 6c shows the finished bulletproof vest before ballistic testing, which consisted of a soft ballistic pack and a sheath made of Cordura® fabric.

Bulletproof vest plating: (a) form of the front of the plating, (b) form of the back of the plating, and (c) developed bulletproof vest superimposed on a plasticine model of female anatomy.

Experimental testing of the ballistic effectiveness of the developed packages was carried out in a system: 9 mm × 19 mm FMJ® Parabellum bullet – bulletproof vest with a package of 16 layers and 30 layers, respectively – ballistic substrate with female anatomy. The test stand consisted of a ballistic gun in the form of the universal ballistic instrument (Arms Factory “Łucznik”, Poland) for firing the bullet, a gate for measuring the impact velocity of the bullet, the test package, a plasticine substrate corresponding to the female anatomy (Figure 7).

Schematic representation of the ballistic tunnel: 1 – ballistic gun, 2 – bullet, 3 – gates for measuring the velocity of the bullet impact, 4 – flight path of the bullet, and 5 – ballistic package located on a substrate with female anatomy.

For the numerical and experimental tests conducted, the expansion and residual length of the bullet were calculated [33,43,51]. To determine the expansion of the bullet, after experimental ballistics tests, the bullets were removed from the ballistic packages, the diameter of the mushroom was measured with a caliper at six different points, and then, the average value was calculated. Similarly, for numerical tests, after a time of 2 ms, the mushroom diameters were measured at six different points and the average value was calculated. The bullet expansion D was then calculated from relation (1):

where d is the diameter of the projectile before impact and d 1 is the diameter of the bullet after impact.

Bullet residual length was calculated by measuring with calipers the length of bullets removed from ballistic packages and after 2 ms in simulation tests at six different points, and average values were calculated. The bullet residual length L was then calculated from relation (2):

where l is the length of the bullet before impact and l 1 is the length of the bullet after impact.

4 Results and discussion

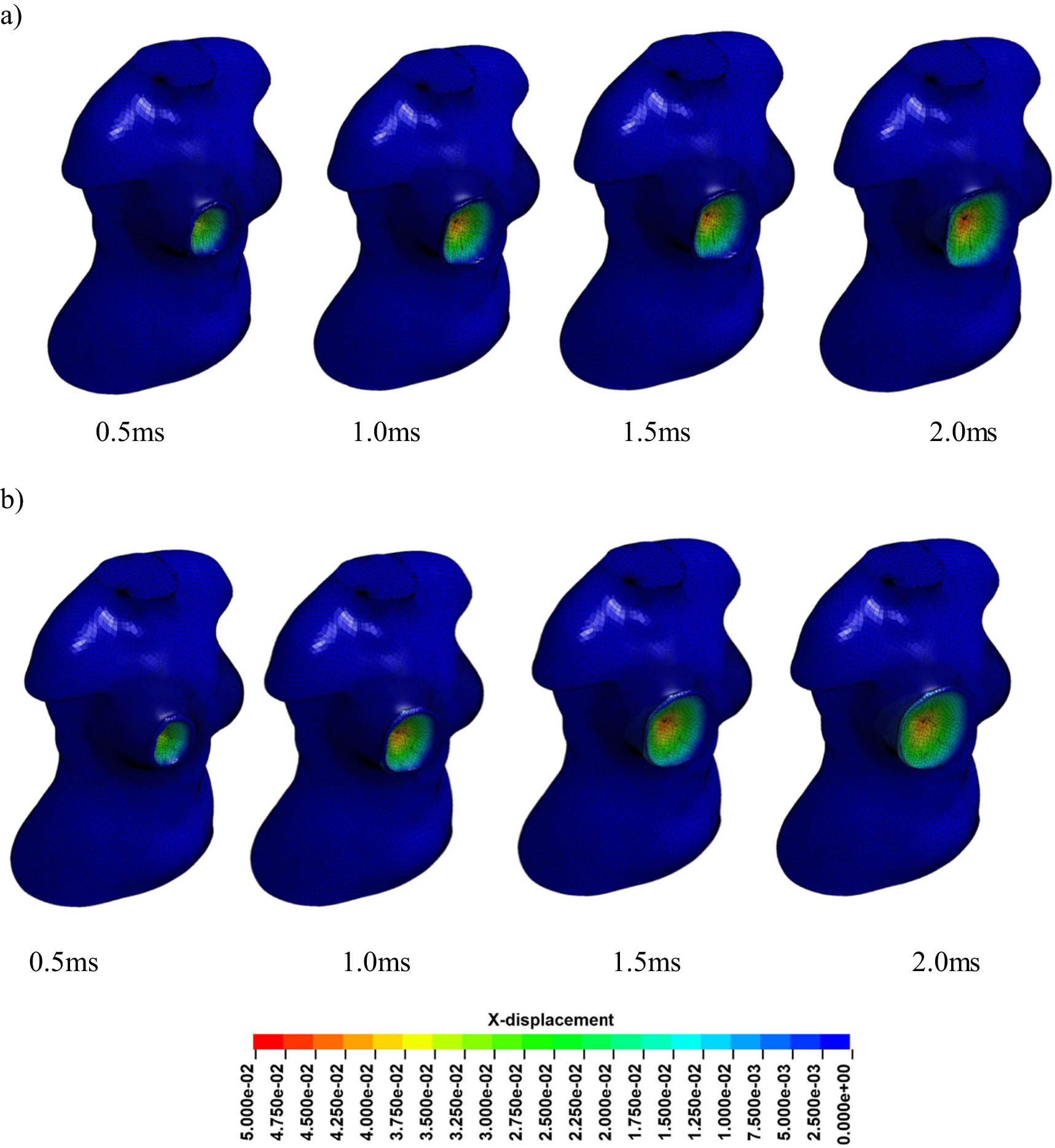

According to the adopted research methodology, the ballistic performance of the packages was analyzed numerically using LS-Dyna software, for which the parameters of the material model were assumed on the basis of the strength tests of Twaron® CT 709 fabric available in the literature. In the first stage, the deformation of the breast after a non-penetrating bullet impact protected by a ballistic package of 16 and 30 layers was analyzed (Figure 8). It was noted that the area and shape of the deformed breast at successive time sequences from 0 to 2 ms are similar for both 16 and 30 layers. This indicates the validity of the hypothesis that the cut-and-sew formed cup deforms easily transversely and the number of layers of the ballistic package significantly increased from 16 to 30 has little effect on reducing breast deformation. The scale of breast deformation in both cases of packages is significant. The maximum value of breast deformation occurs at the point of impact of the bullet after a time of about 1.5 ms for both the 16- and 30-layer composite package and is 46 and 45 mm, respectively. After this time, a slight decrease in deformation is evident, related to the relaxation of the ballistic substrate. It is important to note the almost identical shape of the inlet cavities and deformation cones in the different observed time sequences after firing of both variants of the packages. The inlet cavities generally have a circular shape with a diameter of about 16 cm for a package of 16 layers and about 14 cm for a package of 30 layers. The results indicate that the number of layers of the package has little effect on the deformation of the breast during bullet firing and the dominant factor seems to be the formed cup, which easily deforms transversely in the direction of the bullet trajectory in both the package of 16 and 30 layers. Similar simulation studies of the impact of a bullet on a ballistic package composed of 30 layers of Kevlar 29 fabrics and placed on a Roma No. 1 plasticine substrate were carried out by simulation studies using LS-Dyna software [31]. In these studies, however, the layers of the ballistic package were flat and were placed on a flat plasticine substrate. In these studies, the maximum value of deformation was significantly smaller than the values recorded in the presented studies and was about 33 mm after a time of about 1.7 ms with identical bullet impact parameters and identical material models of the layers. This means that protruding above the plane of the ballistic package elements like breast cups and the shape of the plasticine substrate matched to these elements have a very strong influence on the amount of substrate deformation during non-penetrating bullet impact.

Deformation for a package consisting of: (a) 16 layers and (b) 30 layers.

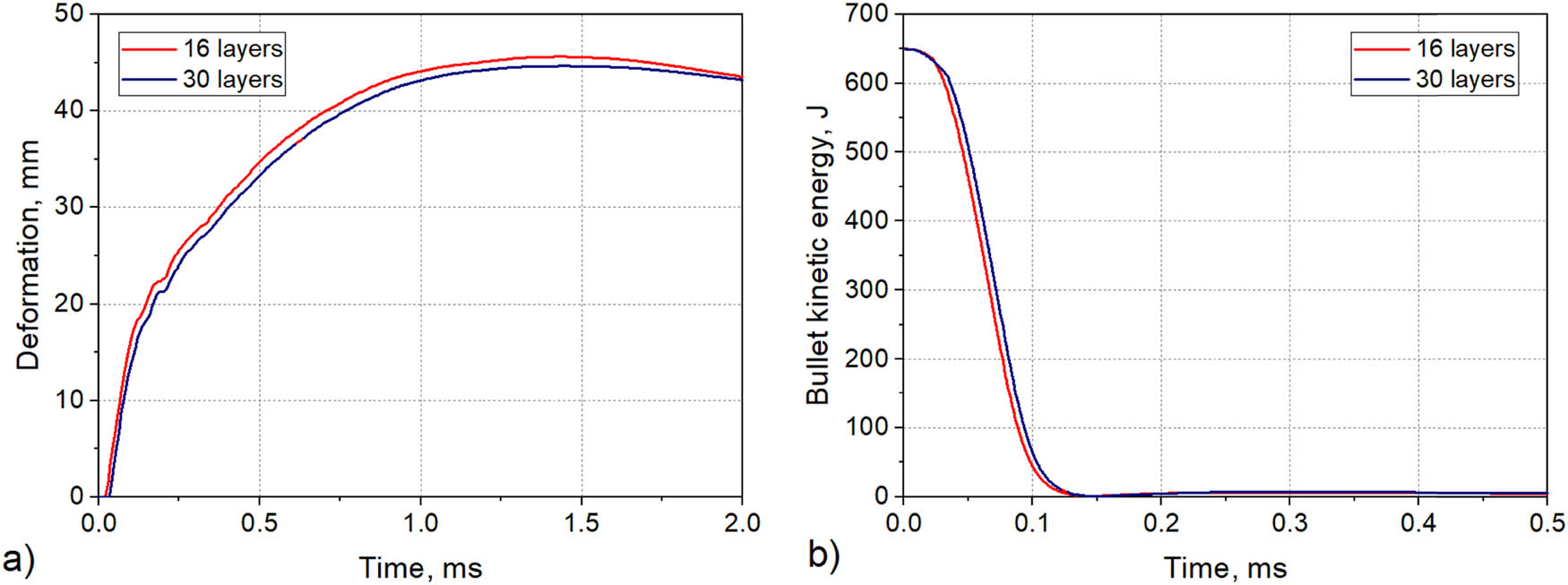

Figure 9 shows the deformation of the breast at the point of impact of the bullet and the KE of the bullet as a function of time for both variants of the packages based on the obtained results of numerical tests. The plot of these relations for packages composed of 16 and 30 layers is very similar. A slightly smaller value of deformation occurs for a package composed of 30. The graph of deformation as a function of time shows that at the moment of bullet impact, the ballistic package deforms rapidly, and despite the deceleration of the bullet after a time of about 150 µs, the deformation of the breast further increases, which is the effect of the shock wave induced during the impact of the bullet. The results clearly indicate that a significant increase in the number of layers in the ballistic package does not lead to an improvement in its effectiveness. It is believed that this is due to the effect of easy transverse deformation of the formed cup in the ballistic package during the impact of the bullet.

Numerical results for packages of 16 and 30 layers: (a) breast deformation at the point of bullet impact as a function of time and (b) KE of the bullet as a function of time.

On the other hand, simulation studies of the KE of the bullet show a very similar course for both package variants (Figure 9b). The bullet for both variants stops after about 150 µs achieving full deceleration. The symmetry of the deformation and KE waveforms observed here indicates that the number of layers in the package does not significantly affect the course of these phenomena. The decisive factor appears to be the package’s fit to the female anatomy in the breast area, which is easily deformed transversely during bullet impact.

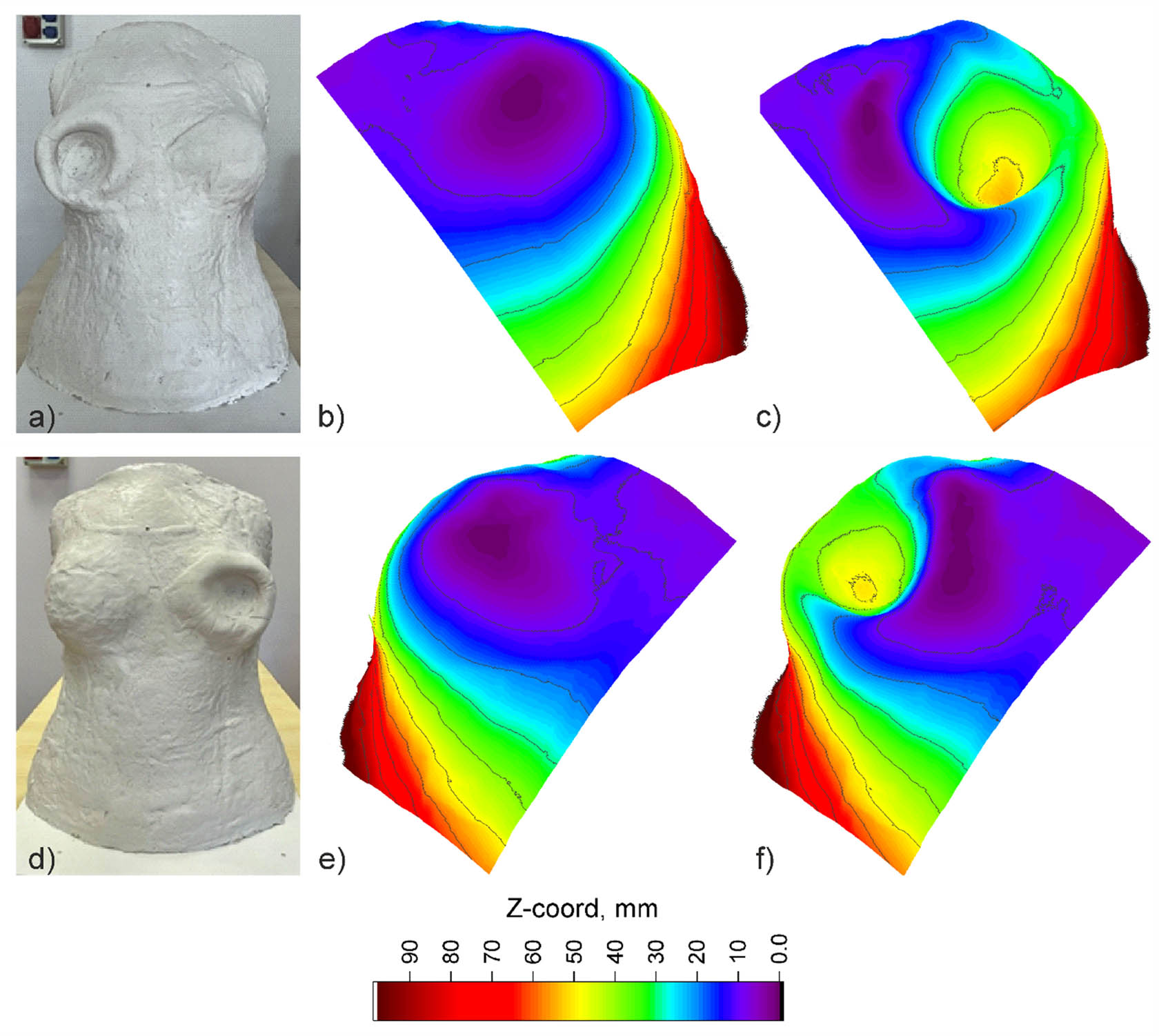

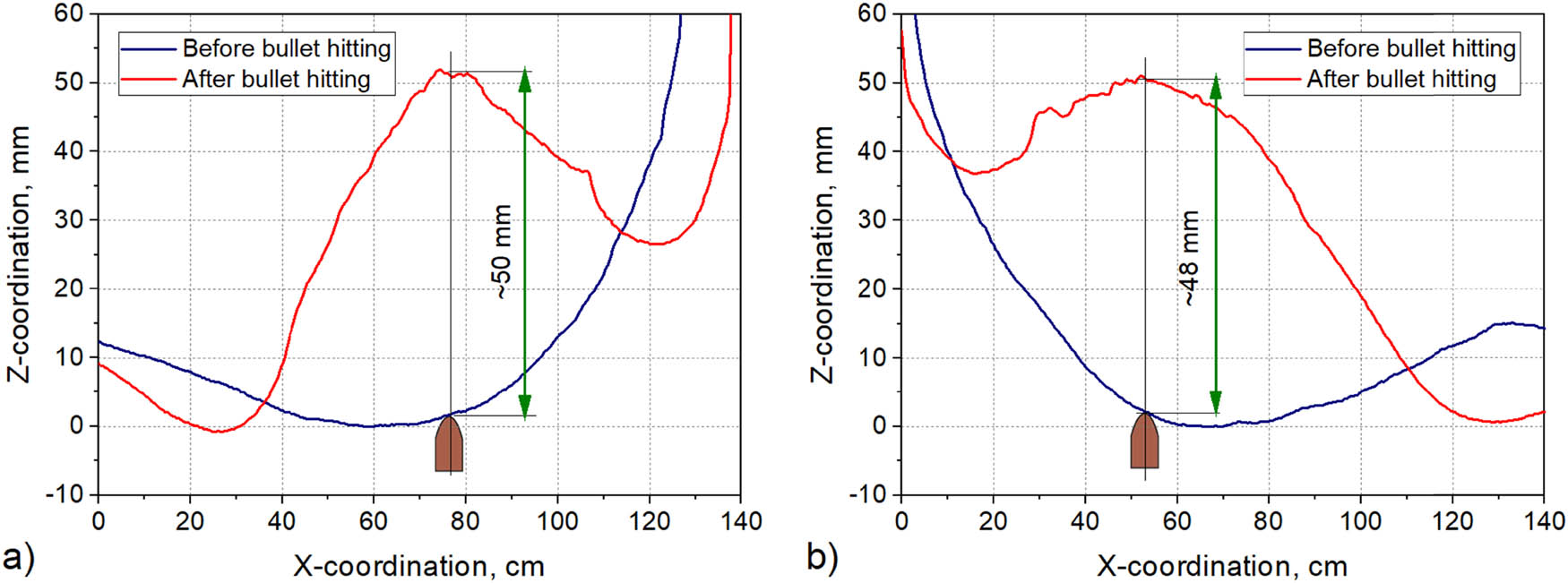

In the next stage, the results of experimental tests were analyzed. First, the deformation values of the ballistic substrate after the bullet impact were analyzed (Figure 10). The presented experimental results were obtained by 3D scanning of the plasticine substrate before and after the bullet firing. For this purpose, a scanner equipped with an XY drive and a laser distance sensor was used [31]. The measured z-coordinate was calibrated so that the value of this coordinate, equal to 0 mm, referred to the highest point of the scanned breast before firing. For the modeled woman, this point coincided with the nipple of the breast. As can be seen in the presented figures, the deformation of the breast for both variants of packages consisting of 16 and 30 layers of Twaron® CT 709 para-aramid fabrics is very similar and close to the obtained results of numerical tests. The maximum value of deformation at the point of impact was about 50 and 48 mm for packages composed of 16 and 30 layers, respectively. In the numerical tests, these values were slightly smaller and were 46 and 45 mm, respectively (Figure 9a). These are significantly higher values than when a bullet with similar parameters but impacting a flat package is deposited on a flat plasticine substrate [52]. When a Parabellum 9 × 19 FMJ® bullet impacted a flat package composed of 26 layers of Twaron® CT 709 fabrics and deposited on a flat plasticine substrate Roma No. 1 at 380 m/s, the maximum deformation value at the point of impact of the bullet was 30.5 mm. In contrast, the intake cavities presented in Figure 10a and d, as in the numerical studies (Figure 8), are circular in shape with diameters of about 13 and 11 cm for packages composed of 16 and 30 layers, respectively. The tests also show that a significant increase in the number of layers in a soft ballistic package from 16 to 30 does not improve the ballistic effectiveness of a package with a cut-and-sew formed cup. The maximum deformation of the breast at the point of bullet impact is only 2 mm less after increasing the number of layers of the package from 16 to 30. Observation of the ballistic substrate before and after bullet impact shows a significant spread of the plasticine into the sternum area and toward the armpit (Figure 10b, c, e, and f). Such a large deformation of the breast can lead to external as well as internal injuries that can limit the basic function of the mammary gland.

Breast deformation during bullet impact – experimental studies: (a) view of plasticine model after bullet impact – protective package of 16 layers, (b) right breast before bullet impact, (c) right breast after bullet impact protected by package of 16 layers, (d) view of plasticine model after bullet impact – protective package of 30 layers, (e) left breast before bullet impact, and (f) left breast after bullet impact protected by package of 30 layers.

Figure 11 shows breast deformations in cross-section for 16 layers and 30 layers, respectively, with the trajectory of the bullet and the location of bullet impact marked. The shape of the breasts for both variants of the packages before and after the bullet impact differs significantly. In the direction of the trajectory of the bullet, formed cones are visible, where the tops of these cones mark the maximum deformation of the breast. The deformation of the breast can also be seen, consisting of pushing and spreading the breast to the center of the chest and toward the armpit. The values of the depth of deformation at the point of impact of the bullet in the experimental studies are slightly larger than in the simulation studies. This is most likely due to the assumed simplifications in the geometric model of the package layers, which do not have interlacing, as is the case with real ballistic fabrics. However, it should be emphasized that both numerical and experimental studies obtained similar results, that a significant increase in the number of packet layers from 16 to 30 does not significantly reduce breast deformation during non-penetrating bullet impact. The determining factor in the magnitude of breast deformation appears to be the ease of transverse deformation of the cup formed in the ballistic package.

Breast deformation in cross-section when protected by a package consisting of: (a) 16 layers and (b) 30 layers.

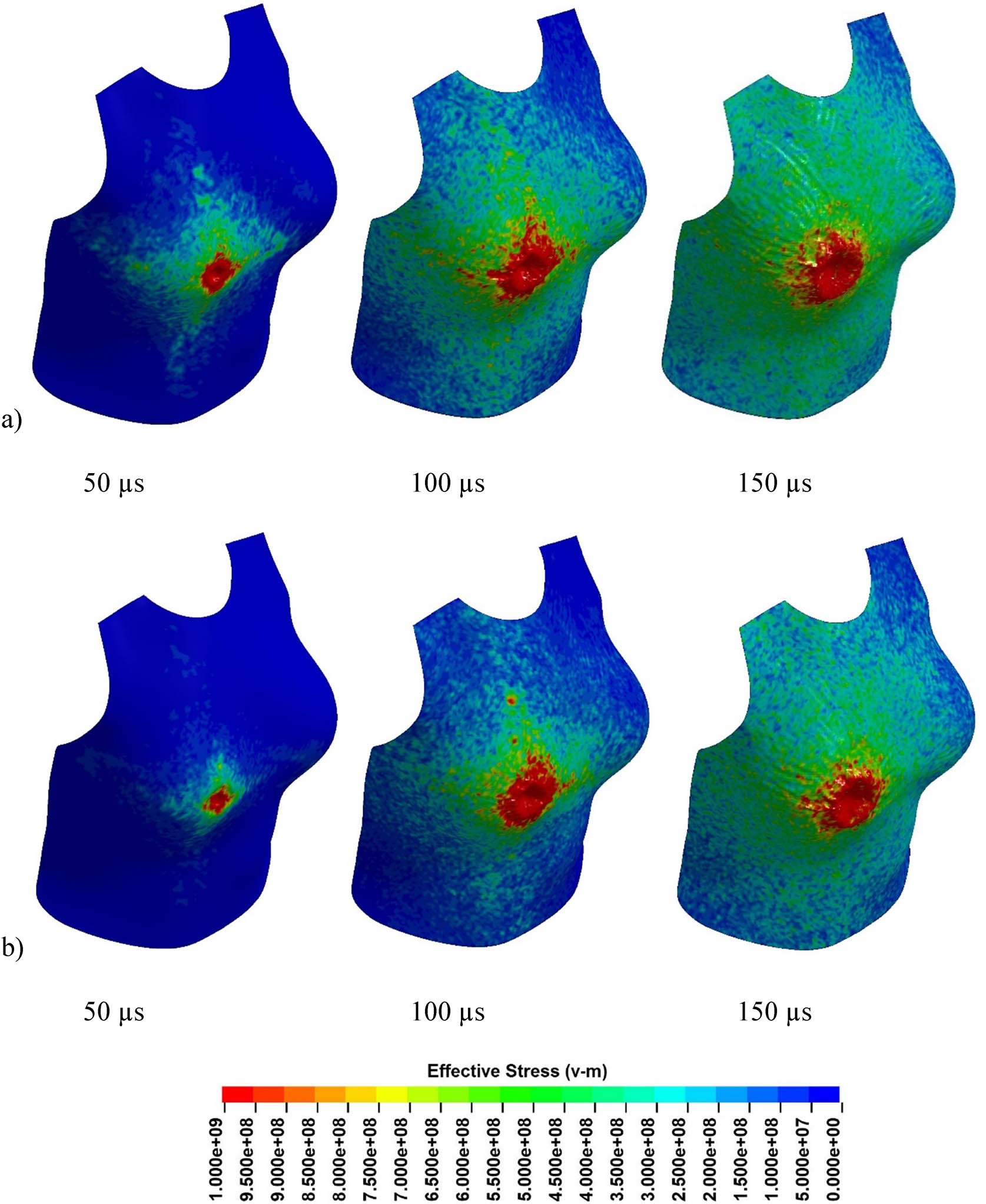

In a further study to seek answers as to why, despite a significant increase in the number of layers in a ballistic package with a cut-and-sew formed breast cup, there are no significant differences in breast deformation values, the results of simulation studies were analyzed in terms of stress propagation in the layers and energy balance. The stress distribution in the ballistic package was analyzed for the last layer in the ballistic package located on the side of the female body model. Figure 12 shows the von Mises stress distribution in this layer at selected time instants of 50, 100, and 150 µs for packages of 16 and 30 layers. The 150 µs time instant corresponds to the moment when the bullet is stopped. The areas of the ballistic package layer with stresses above 1 GPa are shown in red. In principle, the stresses in the last layer of a 16-layer package should be significantly higher than in the last layer of a 30-layer package. As can be seen in Figure 12, only for the time instant of 50 µs a slightly larger area of stresses above 1 GPa is observed, while for the time instant of 100 and 150 µs, these areas are practically the same. This means that a significantly higher number of layers in the ballistic package do not cause a significant reduction in stresses in the last layer of the package. It should be considered that this is the result of forming the fabric layers on a convex geometry, which are easily deformed under the influence of a force perpendicular to the layer. During bullet penetration, the warp and weft threads loosen in the area of this convex structure and do not effectively transfer stresses to the rest of the layer. In published works where the ballistic substrate has a flat surface, it is noted that the stresses quickly propagate to the entire ballistic packet layer, and the threads give directionality to the stress propagation [32,53,54].

Stress distribution in the last layer of a package consisting of: (a) 16 layers and (b) 30 layers.

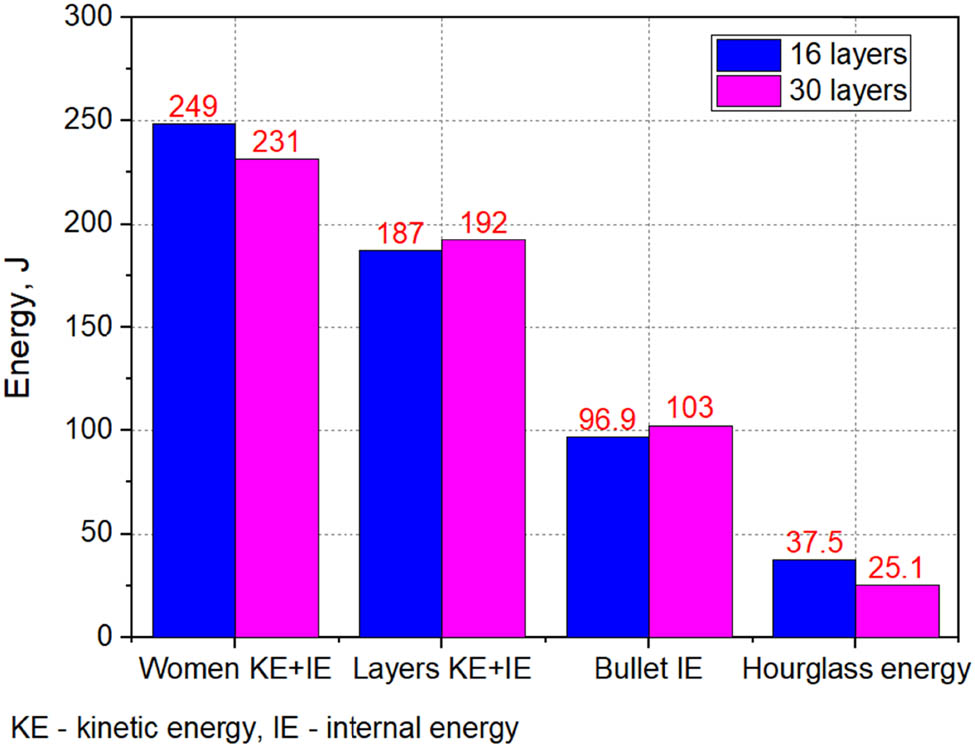

The energy balance for the numerical model was also analyzed during the impact of a bullet on the breast of a woman protected by ballistic packages with 16 and 30 layers. The energy balance was analyzed in terms of the energy absorbed by the woman’s body model, by the layers of the ballistic package, and by the bullet due to its deformation (Figure 13). The energy absorbed by the female body model and the layers of the ballistic package is considered both KE and internal energy (IE), while the energy absorbed by the bullet is considered its IE. Comparing the energy balance when hitting a package of 16 and 30 layers, it can be seen that all these absorbed energies in these two firing variants are very similar. The amount of energy absorbed by a ballistic package consisting of 30 layers was slightly higher at 192 J, while for 16 layers, it was equal to 187 J. In contrast, the energy absorbed by the female body model is slightly lower when protected by a package consisting of 30 layers and is 231 J, while for 16 layers, it was equal to 249 J. The energy absorbed by the bullet is also comparable, being 97 and 103 J for a package consisting of 16 and 30 layers, respectively. The results of the absorbed energies also confirm that significantly increasing the number of layers in a ballistic package with a cut-and-sew formed cup does not lead to an improvement in the ballistic effectiveness of the package.

Energy balance in numerical research.

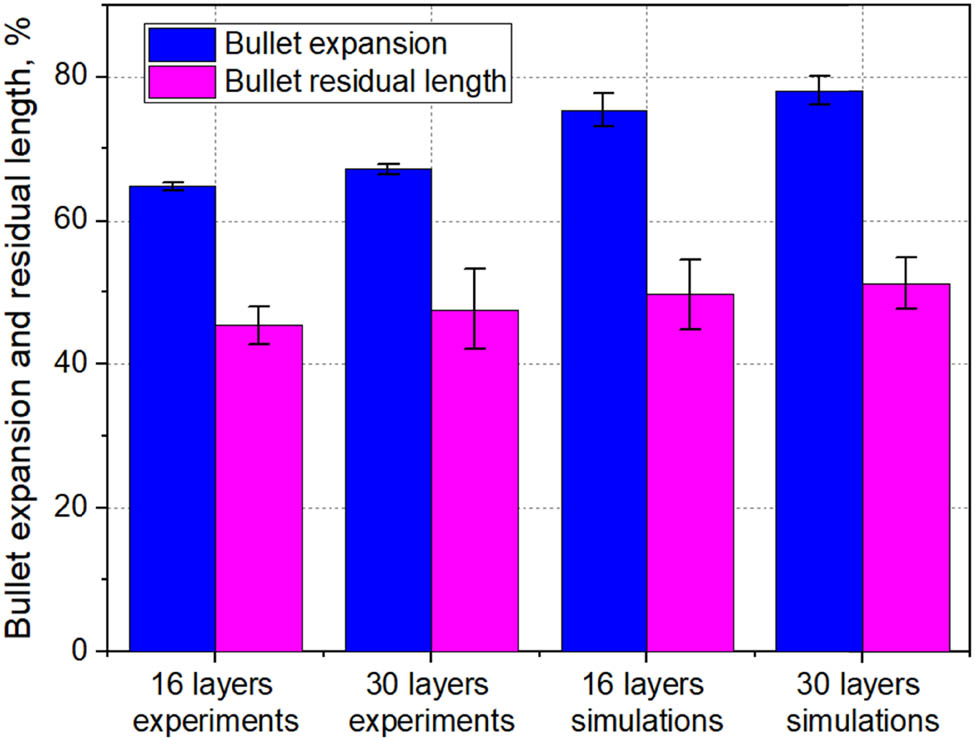

Figure 14 shows the results of numerical and experimental studies of the expansion and residual length of the bullet after it hits a ballistic package composed of 16 and 30 layers. From both numerical and experimental studies, it can be seen that the expansion and residual length of the bullet are comparable for the firing of packages composed of 16 and 30 layers. Indeed, the expansion of the bullet in numerical studies was 75.4 and 78.1% and in experimental studies was 64.8 and 67.2% for packages composed of 16 and 30 layers, respectively. In contrast, the residual length of the bullet in numerical studies was 49.7 and 51.2% and in experimental studies 45.4 and 47.6% for packages composed of 16 and 30 layers, respectively. Obtaining comparable values of bullet shortening expansion correlates comparably with the energies absorbed by the bullet during the firing of these packages (Figure 13).

Bullet expansion and residual length in numerical and experimental studies.

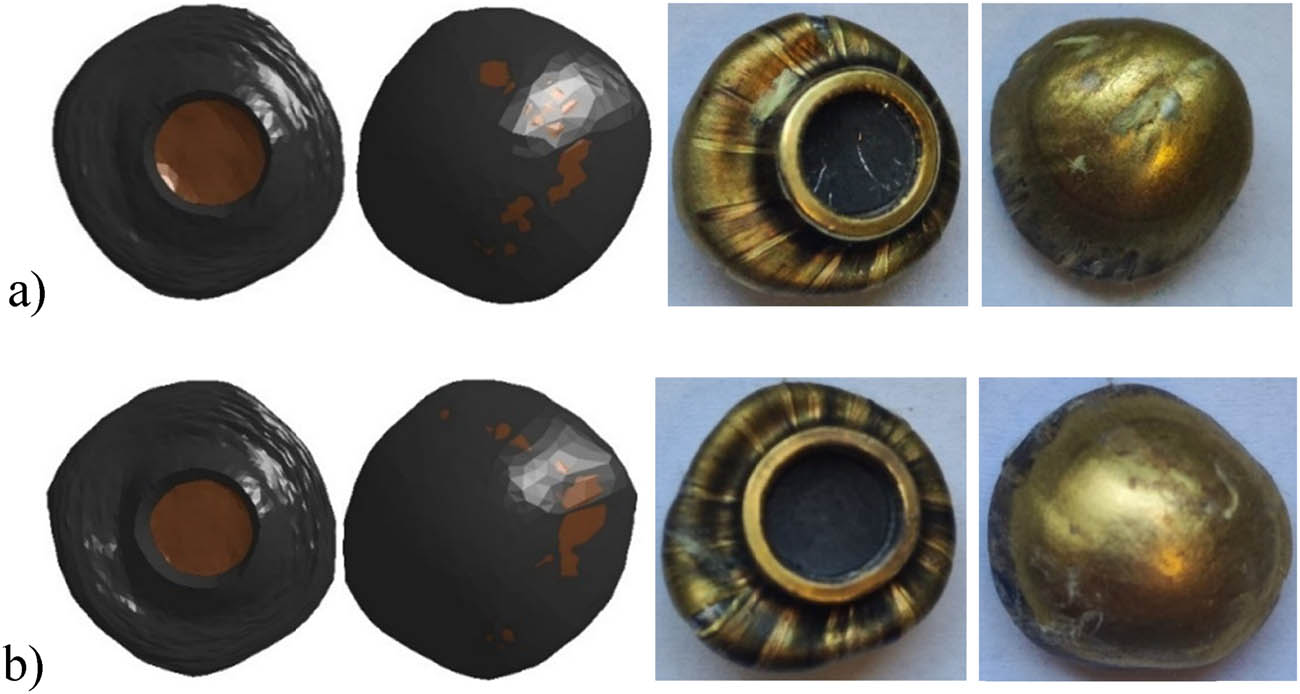

The results of the bullet expansion and shortening tests also confirm that significantly increasing the number of layers in the shaped cup package does not cause significant changes in the values of these parameters. Figure 15 shows views of the front and back of the deformed bullet after numerical tests for the 2 ms time and after experimental tests. It can be seen that there is a very high similarity in the shapes of deformed bullets after firing packages of 16 and 30 layers in both numerical and experimental studies. The increased number of layers in a package with a shaped breast cup does not cause significant changes in the deformation of the bullet during impact.

View of the bullet from numerical and experimental studies for: (a) 16 layers and (b) 30 layers.

5 Conclusion

This article presents a study of soft ballistic packs that were specifically designed to take into account the shape of the female body, particularly with shaped breast cups. The research was aimed at evaluating the ballistic performance of these packages, especially in the context of the significant difference in the number of layers of the ballistic package. The results showed that increasing the number of layers from 16 to 30 does not lead to a significant reduction in breast deformation after bullet impact. Both numerical and experimental analyses showed that the difference in breast deformation is small, suggesting that the additional layers do not significantly increase the level of protection. The study suggests that the likely reason for this course of phenomena is the cut-and-sew formed cup in the ballistic package, which easily undergoes transverse deformation during bullet impact. This means that even when the number of layers is significantly increased from 16 to 30, the impact energy is not effectively dissipated, leading to a similar scale of body deformation. This is significant because it points out the limitations of current methods of ballistic package design and their adaptation to female anatomy. These findings point to the need for further research into the structure of ballistic packages to better adapt them to women’s anatomy and increase their effectiveness in protecting against bullets. In the context of the increasing proportion of women in the uniformed and security services, these issues are becoming increasingly important, requiring innovative solutions and greater attention from designers and manufacturers of protective equipment.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Justyna Pinkos, Zbigniew Stempien; Methodology: Justyna Pinkos Zbigniew Stempien, Karolina Grzegorska, Maria Kulinska, Anna Smędra; Software: Justyna Pinkos, Zbigniew Stempien; Writing: Justyna Pinkos, Zbigniew Stempien, Karolina Grzegorska, Maria Kulinska, Anna Smędra, Visualization: Justyna Pinkos, Zbigniew Stempien, Karolina Grzegorska.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Abtew, M. A., Bruniaux, P., Boussu, F., Loghin, C., Crist, I. (2022). Pattern engineering for customized women seamless ballistic protection vest on 3D virtual mannequin. Journal of Fiber Bioengineering and Informatics, 15(1), 17–25.10.3993/jfbim00373Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Barker, J., Black, C. (2009). Ballistic vests for police officers: Using clothing comfort theory to analyse personal protective clothing. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 2(2–3), 59–69.10.1080/17543260903300307Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Langton, L. (2010). Women in law enforcement, 1987–2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C, pp. 1–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Dojwa-Turczyńska, K. (2019). Sociological insight in service of women in the police forces (in Poland). Polityka Społeczna, 542–543(5–6), 20–28.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Team appointed by the Chief of Police. (2023). Gender equality plan in the police for the years 2023–2026 (in Polish). Polish National Police Headquarters, Warsaw, Poland, pp. 1–39.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Brown, J. (2019). European policewomen: A comparative research perspective. International Association of Women Police, Alexandria, VA, USA, pp. 503–521.10.4324/9781351142847-23Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Garcia, V. (2021). Women in policing around the world: Doing gender and policing in a gendered organization. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New York.10.4324/9781315117607Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Van der Lippe, T., Graumans, A., Sevenhuijsen, S. (2004). Gender policies and the position of women in the police force in European countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 14(4), 391–405.10.1177/0958928704046880Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Toma, D., Niculescu, C., Salistean, A., Luca, D., Popescu, G. E., Popescu, A., et al. (2016). Improved fit and performance of female bulletproof vests. ICAMS Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Materials and Systems.10.24264/icams-2016.III.18Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Chen, X., Yang, D. (2010). Use of 3D angle-interlock woven fabric for seamless female body armor: Part 1: Ballistic evaluation. Textile Research Journal, 80(15), 1581–1588.10.1177/0040517510363187Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Coppola, M. (2014). Body armor for female officers: What’s next? TechBeat, 1, 1–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Web site: https://cjttec.org/. 2024.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Scott, R. A. (2005). Textiles for protection. Elsevier Ltd, Oxford, UK.10.1201/9781439823811.pt3Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Abtew, M. A., Boussu, F., Bruniaux, P., Loghin, C., Cristian, I., Chen, Y., et al. (2021). Ballistic impact performance and surface failure mechanisms of two-dimensional and three-dimensional woven p-aramid multi-layer fabrics for lightweight women ballistic vest applications. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 50(9), 1351–1383.10.1177/1528083719862883Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Yang, D., Chen, X. (2017). Multi-layer pattern creation for seamless front female body armor panel using angle-interlock woven fabrics. Textile Research Journal, 87(3), 381–386.10.1177/0040517516631315Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Abtew, M. A., Bruniaux, P., Boussu, F., Loghin, C., Cristian, I., Chen, Y., et al. (2018). Female seamless soft body armor pattern design system with innovative reverse engineering approaches. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 98(9–12), 2271–2285.10.1007/s00170-018-2386-ySuche in Google Scholar

[17] Cichocka, A., Kulińska, M., Bruniaux, P., Boussu, F. (2009). Ballistic body armor project for women. In AUTEX 2009 World Textile Conference, Izmir.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Saxena, D., Bruniaux, P., Thomassey, S., Gupta, S., Jana, P. (2007). Garment pattern development with ease in 3D. In ITMC 2007 International Conference on Intelligent Textiles and Mass Customisation, Casablanca.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Boussu, F., Bruniaux, P. (2012). Customization of a lightweight bullet-proof vest for the female form. Advanced military textiles and personal equipment, Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, pp. 167–195.10.1533/9780857095572.2.167Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Abtew, M. A., Bruniaux, P., Boussu, F., Loghin, C., Cristian, I., Chen, Y., et al. (2018). A systematic pattern generation system for manufacturing customized seamless multi-layer female soft body armor through dome-formation (moulding) techniques using 3D warp interlock fabrics. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 49, 61–74.10.1016/j.jmsy.2018.09.001Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Ha-Minh, C., Boussu, F., Kanit, T., Crépin, D., Imad, A. (2012). Effect of frictions on ballistic performance of a 3D warp interlock fabric: Numerical analysis. Applied Composite Materials, 19, 333–347.10.1007/s10443-011-9202-2Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Chen, X., Lo, W. Y., Tayyar, A. E., Day, R. J. (2002). Mouldability of angle-interlock woven fabrics for technical applications. Textile Research Journal, 72(3), 195–200.10.1177/004051750207200302Suche in Google Scholar

[23] NIJ Standard-0101.07. U.S. Department of Justice. (2020). Ballistic resistance of body armor. National Institute of Justice, Washington.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] ASTM E3107-23. (2023). Standard test method for resistance to penetration and backface deformation for ballistic-resistant torso body armor and shoot packs. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Sanders, C., Cipolla, J., Stehly, C., Hoey, B. (2011). Blunt breast trauma: Is there a standard of care? American Surgeon, 77(8), 1066–1069.10.1177/000313481107700829Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Hager, M., Spencer, A., Wegener, A., Lee, H., Fillion, M., Yon, J. (2023). Breast trauma: A united states-based epidemiological study from 2016 to 2019. Cureus, 15(12), 1–8.10.7759/cureus.50334Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Sargent, R. E., Schellenberg, M., Cheng, V., Emigh, B., Matsushima, K., Inaba, K. (2023). Breast trauma: A decade of surgical interventions and outcomes from US trauma centers. American Surgeon, 89(6), 2321–2324.10.1177/00031348221096580Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Teijin. (2021). Ballistic material handbook, Teijin Aramid, Netherlands, 38-14-05.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Stempień, Z. (2011). Effect of velocity of the structure-dependent tension wave propagation on ballistic performance of aramid woven fabrics. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 19(4), 74–80.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] NIJ Standard-0101.06. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. (2008). Ballistic resistance of body armor. National Institute of Justice, Washington.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Pinkos, J., Stempien, Z., Małkowska, M. (2024). Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics. AUTEX Research Journal, 24(1), 20230022.10.1515/aut-2023-0022Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Pinkos, J., Stempien, Z. (2020). Numerical and experimental comparative analysis of ballistic performance of packages made of biaxial and triaxial Kevlar 29 fabrics. AUTEX Research Journal, 20(2), 203–219.10.2478/aut-2020-0015Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Kędzierski, P., Morka, A., Stanisławek, S., Surma, Z. (2020). Numerical modeling of the large strain problem in the case of mushrooming projectiles. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 135, 103403.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2019.103403Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Rao, M. P., Duan, Y., Keefe, M., Powers, B. M., Bogetti, T. A. (2009). Modeling the effects of yarn material properties and friction on the ballistic impact of a plain-weave fabric. Composite Structures, 89(4), 556–566.10.1016/j.compstruct.2008.11.012Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Das, S., Jagan, S., Shaw, A., Pal, A. (2015). Determination of inter-yarn friction and its effect on ballistic response of para-aramid woven fabric under low velocity impact. Composite Structures, 120, 129–140.10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.09.063Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Maréchal, C., Bresson, F., Haugou, G. (2011). Development of a numerical model of the 9 mm parabellum FMJ bullet including jacket failure. Engineering Transactions, 59(4), 263–272.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Martínez, M. A., Navarro, C., Cortés, R., Rodríguez, J., Sanchez-Galvez, N. (1993). Friction and wear behaviour of Kevlar fabrics. Journal of Materials Science, 28(5), 1305–1311.10.1007/BF01191969Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Buchely, M. F., Maranon, A., Silberschmidt, V. V. (2016). Material model for modeling clay at high strain rates. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 90, 1–11.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2015.11.005Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Ha-Minh, C., Imad, A., Kanit, T., Boussu, F. (2013). Numerical analysis of a ballistic composite laminate. Composite Structures, 61, 161–173.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Park, Y., Kim, Y., Baluch, A. H., Kim, C. G. (2015). Numerical simulation and empirical comparison of the high velocity impact of STF impregnated Kevlar fabric using friction effects. Composite Structures, 125, 520–529.10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.02.041Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Nilakantan, G., Keefe, M., Bogetti, T. A., Adkinson, R., Gillespie, J. W. Jr. (2010). On the finite element analysis of woven fabric impact using multiscale modeling techniques. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 47, 2300–2315.10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2010.04.029Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Cheeseman, B. A., Bogetti, T. A. (2003). Ballistic impact into fabric and compliant materials. Composites Part B: Engineering, 34(4), 255–270. 10.1016/S1359-8368(02)00054-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Gloger, M., Stempien, Z., Pinkos, J. (2023). Numerical and experimental investigation of the ballistic performance of hybrid woven and embroidered-based soft armour under ballistic impact. Composite Structures, 322, 117420.10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.117420Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Gogineni, S., Gao, X. L., David, N. V., Zheng, J. Q. (2012). Ballistic impact of Twaron CT709® plain weave fabrics. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, 19(6), 441–452.10.1080/15376494.2011.575532Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Hallquist, J. O. (2020). LS-DYNA keyword user’s manual, Vol. I and II. Livermore Software Technology Corporation, Livermore, CA.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Fang, H., Gutowski, M., DiSogra, M., Wang, Q. (2016). A numerical and experimental study of woven fabric material under ballistic impacts. Advances in Engineering Software, 96, 14–28. 10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Chu, Y., Rahman, M. R., Min, S., Chen, X. (2020). Experimental and numerical study of inter-yarn friction affecting mechanism on ballistic performance of Twaron® fabric. Mechanics of Materials, 148, 103421. 10.1016/j.mechmat.2020.103421.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Pinkos, J., Stempien, Z., Smędra, A. (2023). Experimental analysis of ballistic trauma in a human body protected with 30 layer packages made of biaxial and triaxial Kevlar® 29 fabrics. Defence Technology, 21, 73–87.10.1016/j.dt.2022.07.004Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Stark, E., Tymolewska, B. (2020). Modeling women’s clothing forms (in Polish). SOP Oświatowiec Toruń, Torun, Poland.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Parafianowicz, Z. (1997). Construction and modeling of heavy clothing (in Polish). WSiP, Warsaw, Poland.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Bresson, F., Ducouret, J., Peyré, J., Maréchal, C., Delille, R., Colard, T., et al. (2012). Experimental study of the expansion dynamic of 9 mm Parabellum hollow point projectiles in ballistic gelatin. Forensic Science International, 219, 113–118.10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.12.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Gloger, M., Stempien, Z. (2022). Experimental study of soft ballistic packages with embroidered structures fabricated by using the tailored fiber placement technique. Materials (Basel), 15(12), 4208.10.3390/ma15124208Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Barauskas, R., Abraitiene, A. (2007). Computational analysis of impact of a bullet against the multilayer fabrics in LS-DYNA. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 34(7), 1286–1305.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2006.06.002Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Zhou, Y., Chen, X. (2016). Numerical investigations into the response of fabrics subjected to ballistic impact. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 45(6), 1530–1547.10.1177/1528083714564635Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry