Abstract

This paper proposes a critical approach and a model based on the construct of ‘ethics of care‘ to understand researcher vulnerability within contemporary applied linguistics. We emphasise the importance of reflexivity as a practice that foregrounds the humanity of both researchers and participants. In particular, by highlighting the challenges and dilemmas faced by researchers, we advocate for an ethics of care as a guide to address the ethical and practical issues related to researcher vulnerabilities. We discuss how recent shifts in applied linguistics, particularly the reflexive turn, have sharpened the focus on the social and ethical dimensions of research impact, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of generative AI technologies. Our discussion underscores the necessity of acknowledging researchers’ own vulnerabilities and the need for systematic and transparent engagement with these challenges to foster well-being and ethical rigour for all in applied linguistics research.

1 Introduction

In the volume ‘Reflexivity in Applied Linguistics’ (Routledge 2023), Consoli and Ganassin encouraged researchers to provide honest and transparent accounts about their research trajectories, including the challenges and opportunities they encounter. Being reflexive means foregrounding and celebrating the humanities or ‘life capital’ (Consoli 2022) of those who are part and parcel of the research journey – researchers and participants alike. Being reflexive also entails ‘making oneself vulnerable whilst unpacking the various challenges and opportunities faced throughout a study and after’ (Consoli and Ganassin 2023: 3). This embracing of vulnerability not only enriches our inquiries with greater depth and rigour but also illuminates our practices in a novel way. By exploring reflexivity within applied linguistics, the edited volume highlights and celebrates the humanity of both researchers and participants, i.e., who they are as people and what they bring to the research journey, which, in turn, entails a wide range of features and traits that may have negative and/or positive connotations. Specifically, reflexivity can be understood as “the sets of dispositions and activities by which researchers locate themselves within the research processes, while also attending to how their presence, values, beliefs, knowledge, and personal and professional histories shape their research spaces, relationships, and outcomes” (Consoli and Ganassin 2023, p. 6). Crucially, although reflexivity and positionality are interrelated concepts, they represent different aspects of the research process.

Positionality usually consists in a statement of where the researcher stands in relation to their study, thereby acknowledging that research is never neutral and that researcher’s identity, experiences, and beliefs invariably shape or drive a given study. However, recent critiques highlight the risk of positionality statements becoming performative rather than truly reflexive (King 2024). In other words, these statements often serve as credentials rather than mechanisms to reveal how researcher subjectivity impacts research design, participant interactions, and knowledge production. In contrast, reflexivity refers to the ongoing process through which researchers critically examine how their positionality shapes their research choices, interactions, and interpretations. Thus, while positionality focuses on what shapes the researcher’s perspective, reflexivity emphasizes how the researcher actively navigates and interrogates these influences throughout the research journey. For the purpose of this paper, we define positionality as the various factors that shape a researcher’s perspective and reflexivity as the critical process through which researchers actively examine and engage with these influences throughout their social inquiries.

Despite the growing attention to reflexivity in applied linguistics, there remains a significant gap in discussions around how researchers navigate their own vulnerabilities within the research process. These vulnerabilities may stem from personal, emotional, and/or institutional factors that influence decision-making, data interpretation, and researcher well-being. We argue that recognizing vulnerability as an inherent part of the research process calls for an understanding of well-being. As Tov (2018) explains, well-being is not a singular construct but a multifaceted phenomenon encompassing both subjective well-being (hedonic well-being) and psychological fulfillment (eudaimonic well-being). The challenges researchers face – whether emotional distress from sensitive topics or ethical dilemmas – can be framed within these two dimensions. Short-term stressors and emotional fluctuations impact hedonic well-being, whereas the deeper sense of alignment with one’s values and professional trajectory contributes to eudaimonic well-being. Without attention to researcher well-being, there is a risk that researchers may experience ethical distress, burnout, or disengagement from their work. For instance, a researcher working on migration studies may feel a sense of moral responsibility toward their participants but struggle with the emotional toll of hearing distressing narratives. To address this dual gap – researcher vulnerability and well-being – we propose reflexivity as a mechanism to systematically identify, understand, and mitigate researcher vulnerabilities, ensuring ethical transparency and the sustainability of scholarly inquiry.

Specifically, in this piece, we spotlight the sense of vulnerability that researchers in applied linguistics may develop and experience – but rarely talk about – when they engage in any type of social research involving humans. We then propose how ethics of care may serve as a guide to address debates and practical issues around researcher vulnerabilities. To support the well-being of all individuals involved in research projects, we propose a model that serves as an ethical and structural foundation. Ultimately, we hope to stimulate a renewed sense of ethical responsibility towards researcher’s vulnerability with an eye to nurturing their well-being.

2 The reflexive turn in applied linguistics

The field of applied linguistics is constantly implicated with real world issues, and questions about language are invariably at the heart of many socio-political, economic, and ideological debates – this is also in reflection of the unsettling state of current world affairs (cf. Cunningham and Hall 2021). Significantly, the many ‘turns’ of the field, such as the multilingual, social, and affective signal the thriving and, in some ways, ‘activist’ nature of our discipline with direct attention to novel research orientations, novel methodological approaches and renewed ethical frameworks (e.g., Egido and Brossi 2025; Ortega 2005; Prior 2025; Ushioda 2020). For instance, the ‘multilingual turn’ has opened up spaces for more linguistic diversity and equality, giving some or more prominence to a variety of voices who may have been unheard or marginalised. We believe that through these critical and regenerative ‘turns’, researchers have arrived at a novel applied linguistics researcher mindset – i.e., a researcher disposition which is more sensitive to the notion of societal impact and knowledge exchange to benefit the communities that may have been exploited over the years to serve our research agendas.

This more socially and ethically engaged researcher mindset has sharpened even further since the traumatic experiences we endured during the global COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, the suffering and inequalities that surfaced during the COVID-19 era in all contexts worldwide have driven researchers to emphasize the social and ethical dimensions of impact at the research design stage. Researchers have gradually become more aware of the injustices that underpin some contexts we research and how these afflict our ‘research participants’. Importantly, the recent ‘reflexive turn’ in applied linguistics (Prior 2025), as reflected in the volume edited by Consoli and Ganassin (2023), has accentuated the importance of recognizing the humanity embedded within research processes, thereby leading to a reflexive researcher mindset.

Acknowledging our “humanity” as researchers is also critically important at a time when our global landscape is shifting in light of generative AI technologies and, as a result, our personal and professional lives are having to enmesh with rapidly evolving professional practices. We believe that human research ought to be inherently reflexive, thereby requiring researchers to actively consider their own positionality, biases, and ethical responsibilities throughout the research process. In this sense, reflexivity helps researchers remain critically aware of their influence on the study and its participants. AI-supported research, by contrast, follows an algorithmic approach, applying predetermined models to process data and generate results without self-awareness or the ability to critically assess its own processes. However, some studies have already pointed to various heated debates about academic praxis and the role of education in the age of AI (e.g., Baidoo-Anu and Owusu Ansah 2023). Several dimensions of research processes are also being affected and shaped by AI and academic domains around the world seem somewhat divided on the ‘best practices’ to adopt. For instance, in academic publishing, major publishers have issued guidance on the use of GenAI in writing (e.g., https://www.elsevier.com/about/policies-and-standards/publishing-ethics#Authors), with the consensus being that the use of GenAI be declared through a statement with authors ultimately being accountable for the work they submit. Research software platforms are going through some upgrades; the mixed-methods CAQDAS software MAXQDA has now fully incorporated an AI function for data analysis. Atlas.ti, a software for qualitative analysis, recently embedded ChatGPT, claiming that researchers will no longer need to “worry about endless manual coding” and can “reduce your overall data analysis time by up to 90 %” (Atlas.ti 2024). Several studies examining the integration of generative AI (GenAI) in the research process have yielded promising results (e.g., Morgan 2023; Moorhouse and Kohnke 2024), indicating that GenAI tools can enhance the reliability of data analysis. But the questions arise as to what this means for the human accountability of researchers doing social research about human phenomena? and how does the engagement with such AI technologies address research risks and ethical responsibilities? In human research, emotional and professional engagement as well as empathy play a significant role, particularly when working with vulnerable populations. Researchers must navigate emotional labour, ethical dilemmas, and the relational aspects of their work. AI-assisted processes, however, are likely to lack such emotional fabric or the guidance of lived experiences. This is because although AI can analyze language patterns or simulate human-like responses, it does not possess genuine empathy or the ability to build meaningful relationships with research participants, nor does it have the moral compass to navigate difficult research decisions. In other words, researchers are, once again, required to scrutinize their practices in the name of ethics and rigour as they engage with these shifting research paradigms. In our view, these shifts point to the need of nurturing a reflexive researcher mindset, one that critically examines one’s behaviours in light of novel and uncharted methodological practices to ensure the transparency and trustworthiness of our enquiries whilst also remaining ethical towards the people and phenomena that we investigate.

Despite the gradual shift and attention towards a more ethically and socially engaged researcher mindset, researchers tend to focus exclusively on what they are studying and overlook who they are and how the study comes to exist and evolves throughout its lifetime. As the field embraces reflexivity, it is imperative to consider its role not only in acknowledging the researcher’s influence on research but also in safeguarding the researcher’s well-being. Vulnerabilities in research extend beyond the ethical responsibilities toward participants; they also encompass the emotional, professional, and ideological challenges faced by researchers. The reflexive turn, therefore, should include a critical examination of how researchers themselves are affected by the research process and how they can navigate these challenges through systematic self-awareness. This is partly due to the belief that we, as researchers, need to disappear from the research processes and findings with a view to achieving objectivity – i.e., producing accurate accounts of phenomena with no interference from the individual(s) who planned the study, collected, analyzed, and reported the data.

Although we understand the appeal of producing neat and well-crafted studies, we recognize that reality is complex and often messy, and this messiness is not necessarily something we should escape and ignore (McKinley 2019; Prior 2016). Crucially, Rigg (1991) has highlighted ‘the messiness that comes with opening the study to real people living real lives’ (536). Numerous scholars, especially qualitative researchers, have discredited notions of objectivity or universal truths for the very fact that working closely with human participants, even when examining human data through computer-assisted analytical softwares, reduces the ability to study a phenomenon with such detachment (see Dean 2017). We therefore believe that it is important to acknowledge the presence of the researcher throughout all research processes and activities. Significantly, as with all things in research, we need to think about how we account for and represent this dialogic relationship between the researcher and their study in a systematic and rigorous manner. Put differently, we must address questions, such as What motivated the researcher to embark upon a specific study? Why focus on a specific topic/population/context(s)? What identities does the researcher (or a team of researchers) bring to the study (e.g., teacher, parent, learner, activist)? How will such identities be perceived by the research participants? How will the researcher-participant relationship unfold and affect the research processes (e.g., data collection)? How will the findings be shaped by all the people involved in a study or the way such findings may be (re)presented and disseminated?

The practice of reflexivity can help address all these questions, dilemmas, and more. Importantly, we would like to highlight that doing reflexivity entails an examination of the researcher’s ‘origins, biography, locality and intellectual bias’ (Blackman 2007: 700) whilst recognizing the human dimension embedded in the processes and content of our research (Dean 2017). Appreciating this humanity at a time when our societies are being deeply shaped and reconfigured by AI technologies which mimic human behaviours and processes becomes even more critical and perhaps ever so urgent. We certainly do not discard the potential benefits of engaging with such technologies for research purposes; however, we submit that AI tools lack the moral compass to make just decisions whilst studying human phenomena and fulfilling a wide range of ethical responsibilities. This is especially important if researchers decide to draw on AI systems to (re)present human data in research reports – in other words, we need to see evidence of the human agency that researchers wield and how this shapes and/or reconfigures the stories and voices of other humans in their social environment(s).

Some applied linguists have been particularly sensitive to the importance of being self-aware as researchers (e.g., Block 2003; Darvin 2015; Mann 2016; Prior 2016). However, reflexivity is often reduced to a brief outline of one’s motivation for choosing a specific topic and context of research. This reductionist approach, often driven by structural and political constraints, inevitably eschews the meaningful intricacies of one’s own personal and professional stories and how these inform and feed into the design and conduct of a study (Prior and Talmy 2021). Crucially, a number of publications exist where researchers attempt to foreground research participants’ voices whilst concealing their own researcher’s voice and its influence over the research as a whole (Prior 2016). Nonetheless, we would argue that one does not exclude the other. In fact, focusing exclusively on amplifying our participants’ voices can result in ‘decontextualized’ research publications that fail to capture the complexity of the real world (McKinley 2019). Instead, researchers are encouraged to recognize their own presence and influence within the study – acknowledging their biases and researcher effects not as limitations but as integral dimensions of their work, processes, and findings.

3 Reflexivity and life capital

Our proposed approach to reflexivity advocates for researchers to acknowledge and embrace their own life experiences, both personal and professional, as critical influences shaping their inquiries. The meaning and depth of these experiences and human traits are a reflection of the researcher’s (and participants’) life capital which, inter alia, entails memories, desires, emotions, attitudes, opinions, and these can be relatively positive or negative and explicit or concealed’ (Consoli 2021b: 122). As such, the researcher’s and participants’ life capital should be regarded as a source of invaluable insights that further enrich the multi-layered analyses and representations of research data we generate. Importantly, capital here is not intended as a socio-economic resource to accumulate for the benefit of social status. Rather, it is a symbolic and tangible wealth which we all possess by the very nature of being humans with complex and layered life stories which underpin, support, and sustain our behaviours in the many social roles we play throughout our lives (cf. Consoli 2022). Reflexivity, in this context, is not merely an intellectual self-examination but an ongoing biographical and relational process that emerges from one’s life capital. A researcher’s engagement with reflexivity is therefore shaped by their lifetime accumulation of experiences, including an attention to personal/professional histories, vulnerabilities, and socio-cultural contexts. This means that reflexivity is a dynamic and evolving subjective process rather than a static methodological checkpoint. In other words, a researcher’s reflexive engagement with their study does not occur in isolation but is informed by their life capital, such as prior encounters with similar topics, their own lived experiences, and their emotional/professional investments in the research. For example, a researcher studying migration may bring their own personal history of displacement into their analytical lens, consciously or unconsciously influencing how they interpret participants’ narratives. Similarly, life capital can shape how researchers approach ethical dilemmas, how they perceive power dynamics in the research process, and how they navigate the emotional labor of their work. By embedding life capital into reflexivity, we argue for a more transparent, self-aware, and ethically engaged research practice. Therefore, rather than treating reflexivity as a procedural requirement, we suggest that researchers actively recognize how their own personal and professional histories interact with their research processes and participants (Ushioda 2023). This enhanced conceptualization of reflexivity ensures that researchers do not merely acknowledge their positionality but systematically engage with the ways in which their life capital actively shapes their research trajectory.

It is equally critical, however, that researchers, while engaging in this reflexive process, do not become so engrossed in self-reflection and self-writing (e.g., reflecting on and writing about themselves) that the primary research phenomena become secondary. Instead, we encourage researchers to develop a mindset that systematically acknowledges, respects, and celebrates their human presence and related ramifications as well as the participants as part of the research (Consoli 2022; Consoli and Ganassin 2023). This approach to reflexivity is vital because it foregrounds and truly appreciates the humanity inherent in our research endeavours, the social relationships we forge, the data we co-create and the societal impacts we may generate. Nonetheless, a field as intricate and multifaceted as applied linguistics, propelled by action to understand, and/or address social problems, needs more sustained discussions of the many risks and vulnerabilities or threats to well-being which such research may entail. There is ample evidence of remarkable works which have paid much needed attention to the macro and micro ethics concerning research participants (e.g., De Costa 2015; Kubanyiova 2008). And we now wish to extend this debate to the figure of the researcher with a focus on the relationship between their own vulnerability and reflexivity.

4 Understanding vulnerability

In philosophical analyses, vulnerability is usually operationalised in relation to the physical human conditions that make us liable to harm i.e., corporeal vulnerability. Specifically, Butler (2012) emphasises that as physical social beings, we are both vulnerable to the actions of others and dependent on the care and support of others. Therefore, our existence and flourishing depend on social relations with others (Nussbaum 2006). Relatedly, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) states that ‘Vulnerability is an inescapable dimension of the life of individuals and the shaping of human relationships’ (2013, p. 12).

An understanding of ‘vulnerability’ as a shared human condition that is inescapable resonates with current of work in the field of critical legal studies, also termed as the ‘universal vulnerability approach’ (see Turner 2006). In this respect, critics have argued that the universalist conception of vulnerability is too broad and poorly defined to be of any practical use (e.g., Macklin 2003). Therefore, if we adopt a universal view of vulnerability that deems everyone equally vulnerable, we may limit our ability to address context-specific vulnerabilities and the idiosyncratic needs or fragilities of particular individuals (Levine 2004; Luna 2009). In applied linguistics, this has been explored to some extent by Kubanyiova (2008) with her careful attention to micro-ethics alongside macro-ethics. Similarly, we must refrain from labelling particular subgroups or demographics (e.g., children) as vulnerable per se, as this can lead to stereotyping and further discrimination (Dodds 2007) or perpetuating discourses of “victimhood, deprivation, dependency, or pathology” (Fineman 2008; p.8).

Within applied linguistics, vulnerability can be understood as the ‘state or quality which renders communities, leaders, participants, and researchers (as individuals or as part of organisations), as well as their policies research projects, more susceptible or exposed to actions and situations that can result in undesirable outcomes’ (Cunningham and Hall 2021: 4). Badwan (2021) understands vulnerability as either ‘personal’ or ‘collective’, providing a useful frame of reference “for researchers and practitioners who find themselves identified as vulnerable or engage with participants who are considered to belong to vulnerable groups” (Ganassin et al. 2024, p. 386). Importantly, discussions of vulnerability often appear alongside the notion of ‘risk’ (Beck 2009) especially in relation to ‘vulnerable’ participants. While rich debates exist on the onto-epistemic values of vulnerability in several interdisciplinary discourses (cf. Brown et al. 2017), here we focus on some salient dimensions of the construct which underpin our proposal for enhanced researcher reflexivity in applied linguistics.

Over the past two decades, qualitative studies involving ‘vulnerable communities’ (e.g., migrants) have proliferated. To give an example, recent applied linguistics research on migrant and displaced groups (e.g., Ganassin and Young 2020; Georgiou 2022; Kalbeni et al. 2024) has highlighted the critical importance of a duty of care towards individuals whose behaviours, voices, insights are collected, emphasizing this responsibility for both researchers and their institutions to put participants at the centre of the research process. This means, for example, adopting a researching multilingually orientation that values all the languages of the participants and of the research context (Ganassin and Holmes 2020; Holmes et al. 2013). Unsurprisingly, many discourses on vulnerability concern research ethics, where identification of research participants as vulnerable presumes that these participants may have reduced capacity to give informed consent or may require extra protection against harm or exploitation. Importantly, researchers have been busy scrutinising the role of gatekeepers in mediating access to ‘vulnerable’ participants and, perhaps more crucially, in jointly determining who is vulnerable (Reynolds and Brickley 2024), and therefore what constitutes ‘vulnerability’.

For a more in-depth exploration of ‘vulnerability’ in applied linguistics and intercultural communication – particularly in relation to migration and multilingualism – we recommend the recent Special Issue of Language and Intercultural Communication, edited by Ganassin et al. (2024). Several contributions examine vulnerability as a complex, context-dependent phenomenon that evolves over time (e.g., Kalbeni et al. 2024; Reynolds and Brickley 2024; Sidaway 2024) and, at times, how it is shared between researchers and participants (Brohi 2024). Vulnerability is often structurally imposed (McAllister 2024) by the institutions and environments in which individuals are embedded. Consequently, it is frequently linked to systemic factors, thus highlighting how institutions and social structures can affect individuals’ experiences.

Empirical research is directed by ethical guidelines established at both institutional and national levels (e.g., BAAL, BERA). Researchers are also subjected to national, regional laws and administrative regulations (e.g., Data Protection Acts, the Human Rights Act, copyright, and libel laws) and they need to consider how such laws and regulations may affect the conduct of their studies (e.g., data distribution and storage). As an illustration, the guidance offered by UKRI (UK Research and Innovation) to UK-based researchers in relation to Research with Potentially vulnerable people highlights that: ‘Researchers will need to assess potential vulnerability within the context of the research, in terms of potential consequences from their participation (immediate and long-term) or lack of positive impact where this is immediately needed or expected’.

However, there has been limited emphasis on the researcher’s own vulnerabilities beyond the ‘no harm’ principle, which we will revisit, and how these vulnerabilities can influence their career paths beyond the project’s lifespan. For instance, what are the career implications of openly discussing one’s sexual orientation or political and religious beliefs, particularly in contexts where such disclosures are met with hostility or repression? The literature has largely overlooked the construction of researcher vulnerability and the factors contributing to it. A notable exception is Helen Sauntson’s work (2021, 2023) in LGBTQ + studies, which illustrates how shared vulnerability can foster rapport with participants. However, she also highlights the risks of disclosing one’s vulnerabilities in environments characterised by adverse attitudes towards sexual minorities (2023: 175).

Research practice and policy have normally been driven by researchers’ efforts to theorize the concept of ‘vulnerability’ in relation to participants’ experiences. For example, Perry (2011) proposes a contextual and multifaced view of vulnerability that emerges from the interplay of (a) the participants’ characteristics, (b) the nature of the situational context, and (c) the research methods and design (Perry 2011, p. 909). In the second part of this paper, we embrace Perry’s (2011) theorisation of vulnerability as contextual and multifaceted and we respond to her call to revise traditional approaches to research ethics as potentially affecting any fellow human, researchers included.

In doing so, we do not assert that researchers, often operating from a position of privilege, should be regarded as equally vulnerable as participants who may bring various forms of vulnerability into the research process, such as language barriers, destitution, or precarious legal status. Nonetheless, we contend that it is particularly crucial to focus on researcher vulnerability at a time when the field is in the midst of a ‘reflexive turn’ which inevitably puts researchers in a more visible standing within the research arena – an ineluctably ideological and political setting where personal and professional elements of researcher’s life capital may show or entwines with their research.

Certain ethical debates in applied linguistics have already underscored the necessity of safeguarding researcher well-being (e.g., Cunningham and Hall 2021). For instance, the vulnerability of early career researchers has been a focal point (e.g., Eliasson and DeHart 2022; Fenge et al. 2019). Nonetheless, there is a dearth of critical engagement with the concept of vulnerability as it pertains to the researcher experience. Researcher vulnerabilities are frequently overlooked—a reality shaped by political and institutional pressures from funding bodies, publishers, and home institutions, which compel researchers to highlight only the positive or successful aspects of their work. Revealing vulnerabilities, such as disclosing in a research publication that data collection methods were altered due to the distress caused to the researcher, could potentially jeopardize one’s professional reputation. For example, consider a female researcher who experienced a miscarriage and is tasked with conducting a focus group involving new mothers. This scenario could be profoundly distressing at a personal level, highlighting the human element that is often sidelined in the face of professional expectations.

It is arguable that the ontological flexibility of the term vulnerability and its application across disciplines can lead to confusion about what it means for researchers to be vulnerable and how to protect themselves from associated risks. However, some argue that these vague boundaries make the concept adaptable to diverse human experiences of adversity (Wallbank and Herring 2014). Significantly, researcher vulnerability is seldom addressed, especially in policy, underscoring the need for researchers to challenge essentialist views of vulnerability. Brown et al. (2017) contend that the diverse narratives of vulnerability require distinct responses, thereby advocating for a robust critical realist perspective. This approach ensures that vulnerability is recognized not as a vague concept or merely an ethical checkbox, but as a nuanced and defensible issue. Experiencing vulnerabilities often involves a loss of autonomy, agency, or self-power. Feminist philosophers advocate for interventions that restore or enhance autonomy wherever possible. In the context of research participants, this may manifest as ‘researcher activism’ or impactful research, though it is crucial to avoid exacerbating vulnerabilities to a pathogenic level (Mackenzie et al. 2014).

Our contribution signals the importance of both ethical and relational considerations in the research process. One form of vulnerability is tied to power dynamics, marginalisation, and structural factors. This type of vulnerability is often considered when seeking institutional ethical approval for research involving sensitive topics or vulnerable groups. It is closely associated with efforts to safeguard participants, prevent exploitation, and ensure that the research process does not cause harm. The second kind of vulnerability that we discuss in our paper is related to the researcher’s position within the research process, particularly concerning openness, rapport, and empathy. This form of vulnerability arises from the relational and human dimensions of research. Here, vulnerability involves recognizing the shared humanity between researcher and participant, which fosters mutual trust, respect, and a compassionate approach. Although these two aspects of ‘vulnerability’ can often overlap in the same study, we argue that they need distinct attention and handling. Specifically, we can distinguish between structural vulnerability tied to power and marginalisation, which necessitates ethical vigilance, and relational vulnerability tied to researcher empathy and openness, which facilitates more ethical, compassionate engagement with participants.

While ethics of care has traditionally been applied to participant protection, we argue that this framework should be extended to researchers themselves. Institutional pressures, power imbalances, and the emotional toll of research require systematic strategies to support researcher well-being. Reflexivity thus may serve as a catalyst for embedding ethics of care within research processes; ultimately, ensuring that vulnerability is recognized, acknowledged, and managed at all levels. We now draw on ethics of care as a guide to facilitate responses to researcher vulnerabilities.

5 Ethics of care and reflexivity to handle researcher vulnerabilities

‘Ethics of care’ refers to a framework that foregrounds the crucial role of relationships, compassion, empathy and responsiveness in research processes (Held 2006). Significantly, this approach prioritizes the well-being and interests of individuals involved in research, ultimately highlighting the relational interdependence of researchers and participants. Traditionally, our field has adeptly employed the ‘ethics of care’ to cultivate trust, respect, and rapport between researchers and participants (e.g., Consoli 2021a; Ladegaard 2017). This approach primarily focuses on understanding participants’ vulnerabilities and consistently safeguarding their dignity and well-being. We assert that this same level of care and moral consideration should also be extended to researchers, yet there is a notable lack of evidence or guidance on this matter. Although ethical frameworks normally exist to ensure that universities fulfil their duty of care towards staff, students, and research participants, there is often a limited understanding of ‘no harm’ beyond physical injury. Consequently, there is a lack of awareness of how researchers may navigate their own vulnerabilities within the practice of research. We wish to address this lacuna and propose reflexivity as a catalyst for a broader, more transparent, and systematic approach to uncovering and attending to researcher vulnerabilities.

We also wish to bring to the forefront how hegemonic structures and power relationships beyond the researcher-participant relationships and interactions shape the dynamics of vulnerability in the research spaces (Holmes et al. 2022). As highlighted by Pennycook (2017, p. 139), “It is not just that applied linguistics research always reflects the cultural and political contexts in which it is done, however, but that the knowledge it produces is always part of larger interests”.

Significantly, an ethics of care approach to researcher well-being would require us to move beyond the traditional ‘no harm’ principle. Tov’s (2018) well-being framework helps conceptualize this by distinguishing between the affective elements of well-being (hedonic well-being) and the deeper existential dimensions of well-being (eudanomic well-being). Within an ethics of care, we must ensure that research environments and processes foster not only emotional support but also a sense of purpose and meaning in research work. Reflexivity may help maintain this balance – i.e., encouraging researchers to recognize emotional distress (hedonic well-being) while sustaining their motivations, ethical commitments, and healthy intellectual growth (eudanomic well-being). By integrating ethics of care with a reflexive stance on well-being, we emphasize that researcher vulnerability should not be seen as a deficit, but as a necessary part of ethical engagement with social research.

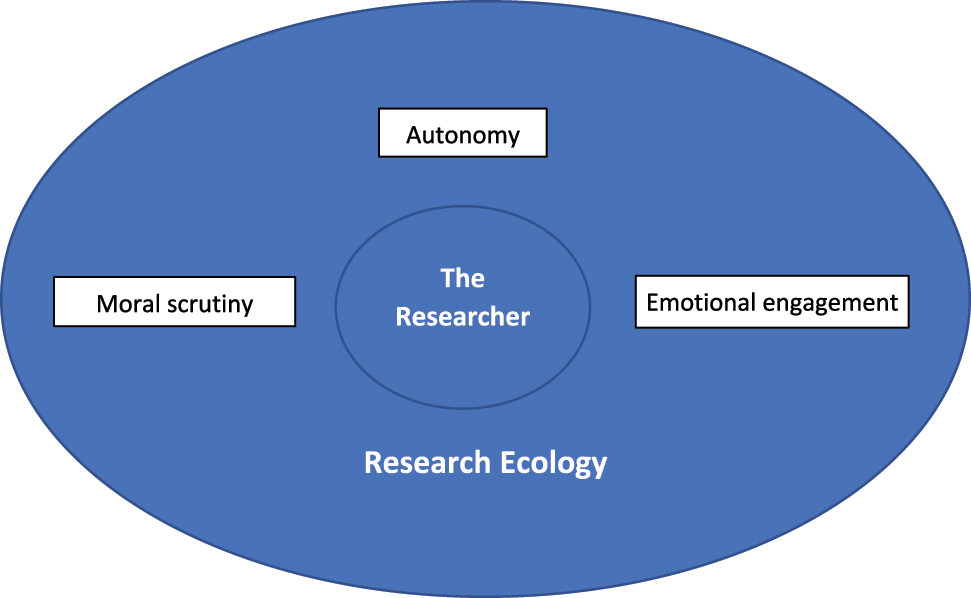

To steer this initiative, we suggest a model inspired directly by ‘ethics of care’ (see Figure 1).

Ethics of care informed Reflexivity.

First, we suggest an attention to researcher emotions which here we refer to as emotional engagement . Not all emotions are equally valued, but attention to the emotional dimensions of personal and research life can shape ethical conduct. The ethics of care values emotions and relational abilities that enable morally concerned individuals to discern what is best in interpersonal contexts (Held 2006). Similarly, we suggest that employing reflexivity to uncover and understand these emotional dimensions will aid researchers in recognizing their potential vulnerabilities. For instance, a researcher interviewing a participant with a similarly troubled background may experience emotional reactions. As an illustration, a researcher may be conducting an interview with a learner about their investment in the language classroom in a country where this foreign language is the official national language. The learner may raise concerns related to racism or discrimination experienced in that country. If these issues resonate with the researcher’s personal experiences, it may evoke significant emotional disturbance in the researcher. Therefore, by being reflexive about these emotions, the researcher can navigate the interview process in a healthy manner, determining what is appropriate to discuss, uncover, or examine empirically without compromising their own well-being or that of the participant. We often worry about the emotional harm we may cause our participants by asking certain questions. By the same token, unexpected themes or situations may emerge from our research processes that may speak to the emotional self within the researcher, and which may perturb or affect their work and well-being.

We therefore encourage researchers to practice emotional reflexivity i.e., taking time to pause, check how they feel and assess whether their work might, at any point during a research project, trigger or exacerbate any negative emotions rooted in their personal or professional lives. While they do not need to disclose these emotions, they should exercise the right to step back and protect themselves. This will in turn ensure the sustainability of their engagement with a specific research phenomenon and participants.

Next, we suggest an attention to research ecology which here we define as the space that spans across the macro-meso-and micro contexts inhabited by the research, their participant(s) and the very social manifestation of the research phenomenon under investigation. Put differently, researcher ecology could be understood as the physical, ideological, socio-political, tangible, and imagined interface of the environments where researchers design, conduct, or disseminate their research. Therefore, an important researcher exercise which we recommend here is moral scrutiny -i.e., the careful and critical examination of actions, decisions, or behaviors from an ethical standpoint. We see reflexivity as a way to perform moral scrutiny and encourage researchers to ensure that no research action or decision may have negative repercussions on the participants or the researcher themselves. This may sound like the obvious ‘avoid harm’ principle on ethics application forms. However, we insist in pushing this beyond the ‘physical’ harm debate as this normally means researchers being encouraged to prioritise participants’ well-being. We suggest exercising reflexivity to be more caring toward oneself, observing if a particular decision or unexpected research scenario may harm the researcher in ways which may not visible or physically measured, but deeply felt within and therefore tangible to their well-being.

Finally, we recognise that in order to be reflexive as well as emotionally and morally self-sensitive, a researcher needs autonomy – this will allow them the agency to inform their choices of behaviour in light of each given context. Unfortunately, we are aware that certain research settings or arrangements are not exactly conducive to such researcher autonomy. For instance, in the case of a postdoctoral fellow working for a team of academics – many vulnerabilities exist in relation to their autonomy. Even when the team of senior researchers or the Principal Investigator may follow institutional ethics guidance for the postdoctoral fellow to collect and/or analyse data, we know that chances are that the postdoctoral fellow will encounter ethically challenging moments. But the question is – will the postdoctoral fellow face all of these? Will they step back and only do what is comfortable for themselves even if this might look like losing face before the senior researcher(s)? These questions, of course, apply to all researchers at all career stages. And these questions of autonomy to exercise one’s reflexive behaviour to protect oneself are critical and need more discussion in the literature and methodological sections of our studies. These open and honest narratives about how a researcher may employ autonomy to handle their vulnerabilities will serve as a catalyst to empower new generations of researchers and nurture a culture of healthy practice that ultimately safeguard the well-being of all.

Finally, we wish to highlight that while we advocate for reflexivity through an analysis of the emotional and moral impact of research processes on oneself, we recognize that excessive engagement in this practice might not be healthy either. For instance, an overexpression of empathy towards our participants or oneself could result in undue self-concern or benevolent intentions turning into controlling behaviour. What we need is an ethics of care, not merely care itself. The various aspects and expressions of care and caring relationships encouraged by our reflexive approach must therefore be subjected to moral scrutiny and evaluated, not just observed and described (Tronto 1993). This connects with the fact that an ethics of care sees persons as relational and interdependent, morally and epistemologically. Therefore, moral scrutiny, driven by autonomy, is a co-constructed effort to guarantee the well-being of all within the research ecology inhabited by both researcher(s) and participants.

The proposed model could thus serve as the architecture that supports the well-being of everyone involved in research projects. It emphasizes the importance of personal relationships and interpersonal connections among researchers and the various individuals, groups, and institutions within their research ecology. In particular, moral scrutiny is a contextual process that emerges from the needs and responses within specific research relationships (Held 2006). Care ethics views emotions as integral to moral understanding and action, considering empathy and emotional responsiveness crucial in guiding moral decisions (Slote 2007).

This model echoes Perry’s work which provides valuable tenets for understanding participants’ vulnerability, which results from the interplay of (a) their characteristics – in our current argument, researchers’ identities and positionalities, (b) the nature of the situational context, i.e., the research ecologies, and (c) the research actions (e.g., research design, methods of data collection) (Perry 2011, p. 909). These factors are dynamic and may evolve over time, impacting one’s experienced vulnerabilities (Reynolds and Brickley 2024). For example, our various roles in a project (e.g., interviewer, participant, friend, confidant) can shift and overlap over the lifetime of the study itself. Similarly, our own researcher self-awareness is never stable and always partial (Perry 2011). When we consider researchers as co-constructors of the research experience alongside their participants, researcher vulnerability is thus shaped by the intersection of who we are (our identities, gender, political and religious beliefs, sexual orientation, and whether we are early-career or established academics) and how our participants perceive us (mediator, confidant, professional), where we operate (our immediate research context, country, as well as virtual and/or international communities), and how we operate (the choices we make regarding our study, such as its methodological approach). These three dimensions must be considered in relation to one another over time, encompassing the entire research project cycle from design to dissemination.

Finally, yet importantly, we wish to draw on Sikes’ (2000) exploration of deception in qualitative research though this may apply to all research orientations and approaches. Deception in research is often framed as a concern primarily related to participant behaviour – whether through withholding information, strategically shaping narratives, or misrepresenting experiences. However, deception is a complex and bidirectional phenomenon that also implicates researchers. While participants may consciously or unconsciously tailor their disclosures, researchers, too, engage in forms of strategic representation – whether by performing rapport to encourage disclosure, selectively disclosing aspects of their own identity, or shaping findings to align with particular institutional, socio-political, or funding contexts. Rather than focusing on deception as an issue of participant honesty alone, a reflexive approach requires us to critically examine the ethical dilemmas that arise when both participants and researchers navigate the social and power-laden dynamics of social inquiry. Specifically, we expand our understanding of researcher vulnerability to include the risk of being intentionally misled by participants. Sikes highlights how the close, trusting relationships often cultivated with our participants can, paradoxically, make researchers more susceptible to deception. This risk adds a critical dimension to the ethics of care, emphasising that trust is not only foundational but also fragile and potentially compromised.

Reflexivity, therefore, must extend beyond the personal and emotional to include a rigorous reassessment of data integrity and methodological soundness when faced with potential deceit. We recognise that this form of participants’ intended ‘mis’-construal of reality may be well-justified from a participant’s perspective (e.g., for self-protection). However, reflexivity may help researchers remain vigilant, continuously questioning not only their own biases and influences but also the nature of the data they collect and why such data and reality may be shaped and (re)presented in such potentially deceitful ways. Ethical research requires transparency and trust, yet it is also necessary to acknowledge the ways in which researchers themselves may contribute to deception – whether intentionally or inadvertently. A particularly pressing concern is the ethical complexity of informed consent, which is often framed as a static agreement but is, in practice, an ongoing negotiation. Researchers must critically examine how their own presence, actions, and self-representations may contribute to ethical dilemmas in the field. By adopting an ethics of care approach, we advocate for a reflexive stance that does not merely emphasize participant vulnerability but also recognizes the ethical challenges and risks researchers themselves face in navigating these interactions. A reflexive approach to research ethics thus requires recognizing deception not as an isolated issue concerning participant honesty but as a complex dynamic that involves both researchers and participants. While much attention has been given to ensuring ethical treatment of participants, less focus has been placed on the ethical dilemmas that researchers themselves encounter – whether in managing their own disclosures, navigating power asymmetries, or negotiating the boundaries of rapport. By integrating an ethics of care framework, we emphasize that ethical responsibility in research extends beyond protecting participants from harm; it also requires researchers to scrutinize their own vulnerabilities, biases, and ethical dilemmas. Ultimately, we argue that deception, rather than being an anomaly in research, is an inherent aspect of knowledge production that must be critically examined through ongoing reflexivity. To conclude, this approach reinforces the need for a flexible, reflexive mindset that can adapt to unexpected challenges, ensuring that research processes and outcomes remain ethically sound and credible. By integrating Sikes’ insights, we underscore that the vulnerabilities researchers face are multifaceted, involving emotional, ethical, and methodological dimensions that require careful, reflexive consideration to uphold the integrity of research.

6 Application of ethics of care informed Reflexivity: a sample research scenario

6.1 Context and background

A university research team is conducting a longitudinal study on the experiences of migrant women navigating language barriers in healthcare settings in a large metropolitan city in Sweden. The project involves semi-structured individual interviews and audio-recorded participant observation sessions organized during a weekly women support group. The overarching research goal is understanding the challenges these women face and how these affect their overall well-being in the host country. The team comprises three female researchers who come from diverse backgrounds, including a principal investigator (PI henceforth) who is an early-career academic with a personal history of migration, a postdoctoral fellow who is a second-generation migrant who also has conversational knowledge of two migrant languages, and a senior researcher, who is part of the host community, with extensive experience in healthcare research but no previous experience in working with multilingual participants.

6.2 Unpacking researcher vulnerabilities

Halfway through the research process, the PI, who migrated to Sweden 15 years prior to the project, begins to feel emotionally distressed when participants share stories of discrimination and exclusion that resonate with her own life experiences. This emotional engagement, while initially seen as a strength for building rapport with participants, starts to affect her mental well-being, making it difficult to maintain professional poise.

Furthermore, the postdoctoral fellow, who is navigating the precarious position of early-career academia, feels a lack of autonomy in making methodological decisions, fearing that voicing her concerns or preferences might jeopardise her relationship with the other team members. The postdoctoral fellow is particularly worried about the ethical implications of the observation data collection methods as she believes these may unintentionally harm participants or the research team. For example – during one weekly women’s support group, she overhears a private conversation between two participants using a shared language other than Swedish. This conversation, captured by the researcher’s audio-recorder, draws on an episode of domestic violence. This postdoctoral fellow is now conflicted between approaching these participants and offering help which she sees as part of her duty of care and the discomfort of becoming privy to an interaction which was meant to be confidential but happened to be in a language that this researcher understood. In this context, the senior researcher, who only speaks Swedish and is the only research member with no experience of migration, begins to feel a degree of inadequacy for being unable to relate to the participants’ stories.

6.3 Application of the ethics of care and reflexivity model

Emotional engagement:

At some point when all researchers feel the effects of this emotional engagement for different individual reasons, they decide to arrange a meeting and share their respective challenges. As a result, they decide to keep a researcher journal focusing on their emotional reactions and plan regular fortnightly meetings where they keep each other updated and self-select elements from their journals to address the most pressing issues they encounter. These practices are intended to help these researchers process their emotions, identify triggers, and explore strategies for managing their emotional reactions without compromising the research’s integrity or their own well-being. This collective approach therefore fosters a supportive environment where each member can express concerns, feel heard, and seek advice on handling emotional challenges.

Moral scrutiny and research ecology:

The team conducts a thorough examination of the research ecology, considering how the intersection of their personal identities and the sociopolitical and geographical context of the study might influence both the research process and outcomes. This includes discussing the power dynamics between researchers and participants, as well as within the research team itself. To address the postdoctoral fellow’s concerns, the team introduces a more collaborative decision-making process where all members can voice ethical concerns and suggest alternative approaches. This process is rooted in moral scrutiny, ensuring that the well-being of both participants and researchers is prioritized in every aspect of the study. This kind of practice may also help researchers identify which duties and responsibilities remain within or go beyond their research remit.

Autonomy:

Each researcher in this scenario may experience discomfort in relation to their own agency due to very unique and personal reasons. For example, the senior researcher who has extensive leadership experience is now working on a project which pushes her out of her comfort zone and she does not have her usual leader role. Instead, whilst bringing expertise in healthcare research, she is the team member with the least understanding of this research context and participants. The research team acknowledges the importance of autonomy in ensuring that each member can engage with the research ethically and without undue stress. For instance, the PI, as an early career researcher, needs to feel supported by the other project members, the post-doctoral fellow needs to feel able to suggest alternative methodological practices without fear of criticism. The senior researcher needs to feel welcome and validated. To ensure this, the PI urges the team to document their insecurities and dilemmas about their role with a view to eradicating any possible sense of self-belittlement – these concerns are shared and discussed as a group to ensure everyone’s well-being is safeguarded and valued at all times. This attention to autonomy, in turn, will help guarantee informed collective decision-making and transparency about all stages and dimensions of the project. For example, at the point of disseminating research findings, an account of ethical and methodological decisions is provided and relevant details about team members’ contributions be outlined transparently. This practice will help illustrate the intricacies of social research and how this group dynamics ‘messiness’ may be approached by other researchers.

6.3.1 Reflections on this sample scenario

By employing the proposed model of Ethics of Care informed Reflexivity, the research team is able to navigate their vulnerabilities effectively. The PI manages her emotional distress through ongoing reflexive practice, ensuring that her personal experiences do not overshadow the research. Both the postdoctoral fellow and the senior researcher feel empowered to assert their unique concerns, contributing to a healthier, more collaborative research ecology. Ultimately, the research not only produces valuable insights into the experiences of migrant women in healthcare but also serves as a model of good research practice that values the well-being of both participants and researchers. Crucially, although our scenario is fictional in nature and it serves the purpose to illustrate our model for ethics of care driven reflexivity, these examples are inspired by real research experiences. We chose specific aspects of a research scenario to make some critical points, but we recognise that our above discussion is not comprehensive because a myriad of other dynamics and dilemmas may be explored. However, we hope that the above illustration sufficiently supports our effort to elucidate the key components of our proposed model of reflexivity whilst offering some food for thought to other researchers.

7 Concluding remarks

With this model, we build upon Consoli and Ganassin (2023), who primarily focused on a reflexive approach that acknowledges and celebrates “the humanity driving our actions and experiences throughout our investigations” (p. 3) This approach underscores how our human presence and roles as researchers interact with other individuals involved in our inquiries, ultimately shaping the research journey, including its processes and outcomes. More significantly, they posited that “embracing researcher reflexivity means becoming not only honest and transparent about one’s research(er) trajectory but also making oneself vulnerable while unpacking the various challenges and opportunities encountered throughout and after a study” (p. 12). They further argued that this sense of vulnerability enhances the depth of meaning and rigour in our research, revealing “the humanities of both researchers and participants, including our talents and imperfections, as well as our behaviours, such as mistakes, trials, successes, and rewards” (p. 13). This reflexive stance not only enriches the research process but also fosters a more profound understanding of the human dimensions that drive our scholarly endeavors whilst interrogating our disciplinary practices, privilege(s), adherence to certain ideologies and socio-political positionings (Prior 2025).

In this paper, we recognized the necessity of initiating a new dialogue that frames reflexivity as a practice capable of anticipating and mitigating researcher vulnerabilities. A reflexive approach can foster researcher well-being by cultivating awareness and resilience. Reflexivity thus enables the development of a systematic understanding of our inherent and contextual vulnerabilities and how these may evolve over time and shape the research ecology. While awareness alone is insufficient to address practical issues surrounding researcher vulnerability (e.g., the potential repercussions of adopting a specific political stance), it can empower researchers to make informed decisions that safeguard both themselves and their participants.

References

Atlas.ti, 2024.Search in Google Scholar

Badwan, Khawla. 2021. Teaching language in a globalised world: Embracing and navigating vulnerability. Language in a Globalised World 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77087-7_10.Search in Google Scholar

Baidoo-Anu, David & Leticia Owusu Ansah. 2023. Education in the era of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. Journal of AI 7(1). 52–62. https://doi.org/10.61969/jai.1337500.Search in Google Scholar

Beck, Ulrich. 2009. World at risk. Bristol: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Blackman, Shane. 2007. Hidden ethnography: Crossing emotional borders in qualitative accounts of young people’s lives. Sociology 41(4). 699–716.10.1177/0038038507078925Search in Google Scholar

Block, David. 2003. The social turn in second language acquisition. Georgetown University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brohi, Hanain. 2024. Collective vulnerability between the researcher and the researched: A reflection on researcher positionality and ‘safety’ in the study of Islamophobia in economic Muslim migrants. Language and Intercultural Communication 24(5). 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2389824.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Kate, Kathryn Ecclestone & Nick Emmel. 2017. The many faces of vulnerability. Social Policy and Society 16(3). 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1474746416000610.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Judith. 2012. [SC1] Precarious Life, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Cohabitation. Journal of Speculative Philosophy 26(2). 134–151. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.26.2.0134.Search in Google Scholar

Consoli, Sal. 2021a. Critical incidents in a teacher-researcher and student-participant relationship: What risks can we take? In Christopher J. Hall & Clare Cunningham (eds.), Vulnerabilities, challenges and risks in applied linguistics, 120–132. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730478.13Search in Google Scholar

Consoli, Sal. 2021b. Understanding motivation through ecological research: The case of exploratory practice. In Sampson Richard & Pinner Richard (eds.), Complexity perspectives on researching language learner and teacher psychology, 120–213. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730471.11Search in Google Scholar

Consoli, Sal. 2022. Life capital: An epistemic and methodological lens for TESOL research. TESOL Quarterly 56(4). 1397–1409. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3154.Search in Google Scholar

Consoli, Sal. & Sara Ganassin. 2023. Reflexivity in applied linguistics. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003149408Search in Google Scholar

Cunningham, Clare. & Christopher J. Hall. 2021. Vulnerabilities, challenges and risks in applied linguistics. Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788928243Search in Google Scholar

Darvin, Ron. 2015. Representing the margins: Multimodal performance as a tool for critical reflection and pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly 49(3). 590–600.Search in Google Scholar

De Costa, Peter I. (ed.). 2015. Ethics in applied linguistics research: Language researcher narratives. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315816937Search in Google Scholar

Dean, Jon. 2017. Doing reflexivity: An introduction. Policy Press.10.56687/9781447330882Search in Google Scholar

Dodds, Susan. 2007. Depending on care: Recognition of vulnerability. Bioethics 21(9). 500–510.10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00595.xSearch in Google Scholar

Egido, Alves Alex & Brossi Giuliana. 2025. Applied Linguistics in the Global South. Lexington Books.10.5771/9781666968019Search in Google Scholar

Eliasson, Michelle & Dana DeHart. 2022. Trauma experienced by researchers: challenges and recommendations to support students and junior scholars. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management An International Journal 17. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-10-2021-2221.Search in Google Scholar

Fenge, Lee-Ann, Lisa Oakley, Bethan Taylor & Sean Beer. 2019. The Impact of Sensitive Research on the Researcher: Preparedness and Positionality. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18. 160940691989316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919893161.Search in Google Scholar

Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2008. The vulnerable subject anchoring equality in the human condition. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 20. 1–23.Search in Google Scholar

Ganassin, Sara, Alexandra Georgiou, Judith Reynolds & Mohammed Ateek. 2024. Vulnerability and multilingualism in intercultural research with migrants: Developing an inclusive research practice. Language and Intercultural Communication 24(5). 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2411083.Search in Google Scholar

Ganassin, Sara & Prue Holmes. 2020. I was surprised to see you in a Chinese school’: Researching multilingually opportunities and challenges in community based research. Applied Linguistics 41(6). 827–854. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz043.Search in Google Scholar

Ganassin, Sara. & Tony. J. Young. 2020. From surviving to thriving: ‘success stories ’of highly skilled refugees in the UK. Language and Intercultural Communication 20/2. 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1731520.Search in Google Scholar

Georgiou, Alexandra. 2022. Conducting multilingual classroom research with refugee children in Cyprus: critically reflecting on methodological decisions. In P. Holmes, J. Reynolds & S. Ganassin (eds.), The politics of researching multilingually. London: Multilingual Press.10.2307/jj.22679758.11Search in Google Scholar

Held, Virginia. 2006. The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0195180992.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Holmes, P., R. Fay, J. Andrews & M. Attia. 2013. Researching multilingually: New theoretical and methodological directions. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 23(3). 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12038.Search in Google Scholar

Holmes, Prue, Reynolds Judith & Ganassin Sara. 2022. Introduction: The imperative for the politics of ‘researching multilingually’. The politics of researching multilingually, 1–27. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22679758.6Search in Google Scholar

Kalbeni, Sotiria, Evgenia Vassilaki & Eleni Gana. 2024. Language education for migrant/refugee inmates inside two prisons in Greece: A nexus analysis research. Language and Intercultural Communication 24(5). 412–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2389821.Search in Google Scholar

King, Kendall. 2024. Promises and perils of positionality statements. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 1–8.10.1017/S0267190524000035Search in Google Scholar

Kubanyiova, Magdalena. 2008. Rethinking research ethics in contemporary applied linguistics: The tension between macroethical and microethical perspectives in situated research. The Modern Language Journal 92(4). 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00784.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ladegaard, Hans J. 2017. The discourse of powerlessness and repression: Life stories of domestic migrant workers in Hong Kong. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315636597Search in Google Scholar

Levine, Carol. 2024. The concept of vulnerability in disaster research. Journal of Traumatic Distress 15(5). 395–402.10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048952.81894.f3Search in Google Scholar

Luna, Florencia. 2009. Elucidating the Concept of Vulnerability: Layers Not Labels. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 2(1). 121–139.10.3138/ijfab.2.1.121Search in Google Scholar

Mackenzie, Catriona, Wendy Rogers & Susan Dodds (eds.). 2014. Introduction. In Vulnerability: New essays in ethics and feminist philosophy. USA: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199316649.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Macklin, Ruth. 2003. Bioethics, vulnerability, and protection. Bioethics 17(5–6). 472–486.10.1111/1467-8519.00362Search in Google Scholar

Mann, Steve. 2016. The research interview: Reflective practice and reflexivity in research processes. Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

McAllister, Áine. 2024. Applied ethnopoetic analysis, poetic inquiry and a practice of vulnerability: Uncovering and undoing the vulnerabilities of refugees and asylum seekers seeking access to higher education. Language and Intercultural Communication 24(5). 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2376634.Search in Google Scholar

McKinley, Jim. 2019. Evolving the TESOL teaching research nexus. TESOL Quarterly 53(3). 875–884.10.1002/tesq.509Search in Google Scholar

Moorhouse, Benjamin & Lucas Kohnke. 2024. The effects of generative AI on initial language teacher education: The perceptions of teacher educators. System 122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103290.Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, David. 2023. Exploring the use of artificial intelligence for qualitative data analysis: The case of ChatGPT. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231211248.Search in Google Scholar

Nussbaum, Marta C. 2006. Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.10.2307/j.ctv1c7zftwSearch in Google Scholar

Ortega, Lourdes. 2005. For what and for whom is our research? The ethical as transformative lens in instructed SLA. The Modern Language Journal 89(3). 427–443.10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00315.xSearch in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair. 2017. The cultural politics of English as an international language. Oxfordshire, UK: Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9781315225593Search in Google Scholar

Perry, Kristen. 2011. Ethics, vulnerability and speakers of other languages: How university IRBs (do not) speak to research involving refugee participants. Qualitative Inquiry 17(10). 899–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411425006.Search in Google Scholar

Prior, Matthew. 2016. Emotion and discourse in L2 narrative research. Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783094448Search in Google Scholar

Prior, Matthew, Steven (2021). A discursive constructionist approach to narrative in language teaching and learning research. System 102. 102595.10.1016/j.system.2021.102595Search in Google Scholar

Prior, Matthew. 2025. Contemporary Applied Linguistics Research: Between reflection and reflexivity. In Habibie Pejman & Sawyer Richard (eds.), Reflexive and Reflective Research Approaches in Applied Linguistics, 248–266. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/rmal.8.14priSearch in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Judith & Katy Brickley. 2024. Addressing issues of (linguistic) vulnerability in researching UK asylum-related advice contexts: Reflections on practice. Language and Intercultural Communication 24(5). 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2381091.Search in Google Scholar

Rigg, Pat. 1991. Whole language in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 25(3). 521–542.10.2307/3586982Search in Google Scholar

Saunston, Helen. 2023. Reflexivity and the production of shared meanings in language and sexuality research. In Sal Consoli & Sara Ganassin (eds.), Reflexivity in applied linguistics, 171–189. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003149408-10Search in Google Scholar

Sauntson, Helen. 2021. Befriending risks vulnerabilities and challenges: Researching sexuality and language in educational sites. In Clare Cunningham & Christopher Hall (eds.), Vulnerabilities, challenges and risks in applied linguistics. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730478.8Search in Google Scholar

Sidaway, Kathryn. 2024. Reflexive participant collaboration: Researching ‘with’ adult migrant learners of English. Language and Intercultural Communication 24(5). 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2383250.Search in Google Scholar

Sikes, P. 2000. ‘Truth’and ‘lies’ revisited. British Educational Research Journal 26(2). 257–270.10.1080/01411920050000980Search in Google Scholar

Slote, Michael. 2007. The Ethics of Care and empathy. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203945735Search in Google Scholar

Tov, William. 2018. Well-being concepts and components. In Shigehiro Oishi Ed Diener & Louis Tay (eds.), Handbook of well-being, 30–44. Salt Lake City: Noba Scholar.Search in Google Scholar

Tronto, Joan. 1993. Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Turner, Bryan. 2006. Vulnerability and human rights. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 2013. The Principle of Respect for Human Vulnerability and Personal Integrity: Report of the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO (IBC). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000212101.Search in Google Scholar

Ushioda, Ema. 2020. Language learning motivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ushioda, Ema. 2023. Foreword in Consoli Sal & Ganassin Sara (eds.), Reflexivity in applied linguistics: Opportunities, challenges, and suggestions. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Wallbank, Julie & Jonathan Herring. 2014. Vulnerabilities, Care and Family Law. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203797822Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the role of ideal L2 writing self, writing growth mindset, and writing enjoyment in L2 writing self-efficacy: a mediation model

- The role of home biliteracy environment in Chinese-Canadian children’s early bilingual receptive vocabulary development

- Review Article

- A systematic review of time-intensive methods for capturing non-linear L2 development

- Research Articles

- Reflexivity as a means to address researcher vulnerabilities

- L2 English pronunciation instruction: techniques that increase expiratory drive through enhanced use of the abdominal muscles, and transfer of learning

- Review Article

- Early career language teachers’ cognition, practice, and continuous professional development: a scoping review of empirical research

- Research Articles

- Unpacking digital-driven language management in a Chinese transnational company: an exploratory case study

- Unequal translanguaging: the affordances and limitations of a translanguaging space for alleviating students’ foreign language anxiety in language classrooms

- Monologuing into a dialogic space through translanguaging: probing the perceptions and practices of a history EMI teacher in higher education

- How foreign language learners’ benign and deleterious self-directed humour shapes their classroom anxiety and enjoyment

- Generative AI and the future of writing for publication: insights from applied linguistics journal editors

- Positive emotions fuel creativity: exploring the role of passion and enjoyment in Chinese EFL teachers’ creativity in light of the investment theory of creativity

- The perception of gradient acceptability among L1 Polish monolingual and bilingual speakers

- Navigating between ‘global’ and ‘local’: a transmodal genre analysis of flight safety videos

- Investigating EFL learners’ reading comprehension processes across multiple choice and short answer tasks

- English medium instruction lecturer within-course linguistic evolution: monitoring changes between STEM lectures

- Contributions of interaction, growth language mindset, and L2 grit to student engagement in online EFL learning: a mixed-methods approach

- Performing my other self: movement between languages, cultures and societies

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the role of ideal L2 writing self, writing growth mindset, and writing enjoyment in L2 writing self-efficacy: a mediation model

- The role of home biliteracy environment in Chinese-Canadian children’s early bilingual receptive vocabulary development

- Review Article

- A systematic review of time-intensive methods for capturing non-linear L2 development

- Research Articles

- Reflexivity as a means to address researcher vulnerabilities

- L2 English pronunciation instruction: techniques that increase expiratory drive through enhanced use of the abdominal muscles, and transfer of learning

- Review Article

- Early career language teachers’ cognition, practice, and continuous professional development: a scoping review of empirical research

- Research Articles

- Unpacking digital-driven language management in a Chinese transnational company: an exploratory case study

- Unequal translanguaging: the affordances and limitations of a translanguaging space for alleviating students’ foreign language anxiety in language classrooms

- Monologuing into a dialogic space through translanguaging: probing the perceptions and practices of a history EMI teacher in higher education

- How foreign language learners’ benign and deleterious self-directed humour shapes their classroom anxiety and enjoyment

- Generative AI and the future of writing for publication: insights from applied linguistics journal editors

- Positive emotions fuel creativity: exploring the role of passion and enjoyment in Chinese EFL teachers’ creativity in light of the investment theory of creativity

- The perception of gradient acceptability among L1 Polish monolingual and bilingual speakers

- Navigating between ‘global’ and ‘local’: a transmodal genre analysis of flight safety videos

- Investigating EFL learners’ reading comprehension processes across multiple choice and short answer tasks

- English medium instruction lecturer within-course linguistic evolution: monitoring changes between STEM lectures

- Contributions of interaction, growth language mindset, and L2 grit to student engagement in online EFL learning: a mixed-methods approach

- Performing my other self: movement between languages, cultures and societies