Abstract

It is well known that a major impediment to the successful mastery of a target foreign language (FL) is a lack of exposure outside the classroom. The present one-year longitudinal study set out to examine (1) the amounts and kinds of exposure to English outside class experienced by young learners in an EFL context, (2) the relationships between their exposure and socioeconomic status (both parents’ education levels and household incomes), and (3) the association between exposure and vocabulary gains. Ninety Grade-5 EFL children in Hong Kong completed a pre- and post-vocabulary test with a gap of 1 year. Individual interviews were conducted with each child’s parent(s)/guardian(s) (and the children themselves) to collate data about their backgrounds and the child’s exposure to English. The findings revealed that all participants received out-of-class English input through doing homework, and more than two-thirds of them attended tutorial classes and engaged with general informal exposure to English (GIE) such as watching videos and reading books. (Marginally) positive correlations were found between GIE, household income, and parents’ levels of education. GIE was also found to be related to total vocabulary gains over the one-year period, especially at the 2,000-word level.

1 Introduction

The term foreign languages (FLs) signals that such languages do not exist naturally in abundance in many of the contexts in which they are studied. While English as a foreign language (EFL) is globally one of the most popular foreign languages, the dearth of natural exposure to English outside class in some contexts has long been regarded as a substantive issue in EFL education, since receiving a large amount of input is essential for successful mastery of any language (Ellis 2002; Lichtman and VanPatten 2021; Tsang 2023a; Tsang 2023b). Nevertheless, it is clear that English has become easily accessible to EFL learners thanks to technological advancements such as viewing platforms (e.g., YouTube) and social media (e.g., Instagram). It may no longer be as foreign as once regarded in EFL contexts, and this phenomenon likely implies that EFL learning can now be carried out much more readily outside class. Having an up-to-date understanding of the linguistic landscapes in which EFL learners reside has important implications for curricular design and pedagogical approaches. To this end, we examined young EFL learners’ out-of-class exposure to English in the context of Hong Kong. The reason for focusing on young learners was that they have largely been neglected in FL teaching and learning research (e.g., Lam and Tsang 2025; Marulis and Neuman 2010; Tsang and Yeung 2024) even though EFL has now been incorporated into primary school curricula in many places globally. It is highly worthwhile researching young learners so that potential effective interventions can be designed, trialled, and implemented early for successful EFL learning (Tsang and Yeung 2024).

It can be hypothesized that a relationship between children’s out-of-class FL exposure and their socioeconomic status (SES) exists. For example, children whose parents have higher incomes and/or educational levels tend to be more able to afford tuition fees in out-of-class activities and purchase supplementary learning materials, and these parents are likely more willing to be devoted to their children’s out-of-class learning (Capizzano et al. 2000; Lau and Cheng 2016; Mahoney et al. 2005). It was therefore thought to be important to investigate if significant relationships between SES and different kinds of extramural exposure existed and if yes, how strong these relationships were. We were not aware of any studies that had examined different facets of SES (e.g., income; parental education levels) and specific kinds of out-of-class exposure. We therefore set out to address this gap. Also, in the field of FL teaching and learning, one key indicator of success is how well the learner has mastered the FL. Vocabulary is a core component in learning any language (Nation 2013) and learners’ performances on vocabulary tests have therefore often been regarded as a proxy for examining proficiency levels (e.g., Nation 2013; Uchihara and Clenton 2020). In light of the above, SES and vocabulary size were also examined alongside extramural exposure in this one-year longitudinal study.

2 Literature review

2.1 Extramural exposure and FL learning

A core challenge in classroom-based EFL education is the time constraint. In many EFL settings, there are usually only limited numbers of hours devoted weekly to EFL learning, as time is allocated to various other subjects such as the learners’ mother tongue and mathematics. To master any language successfully, abundant exposure is indispensable. For instance, English learners often need to know more than the most frequent 2,000 English words to be able to comprehend different texts and “there is clearly not enough classroom time to teach that many words” (Webb 2015, p. 159). As students increase their exposure to English words through extramural learning, their overall language competence is likely to improve (Lu and Dang 2023). One key reason for this is known as the frequency effect. As Ellis (2002) has reported in his seminal review article, frequency plays an important role in the processing of “phonology, phonotactics, reading, spelling, lexis, morphosyntax, formulaic language, language comprehension, grammaticality, sentence production, and syntax” (p. 143). Since language learning involves “a huge collection of memories of previously experienced utterances” (Ellis 2002, p. 166) and classroom time is limited, it can be argued that abundant out-of-class exposure is perhaps the only promising avenue for mastering a FL. Kusyk et al. (2025, p. 2) have noted in their scoping review that multiple terms have been created to refer to out-of-class and/or informal second/foreign language learning, some of which “include assigned or teacher-/other-directed activities (e.g., IDLE, LBC, LLT)”. Sundqvist (2009) introduced the term Extramural English (EE) to refer to learner-initiated exposure to English outside class. Sundqvist (2024, p. 5) clarifies that EE “does not have any connection with school or schooling, that is, no connection with formal (or “intramural”) learning”. In this article, we use the adjective extramural to indicate outside the compulsory mainstream EFL class such that informal activities (e.g., listening to songs at home), completing homework (e.g., at home/a café) and having supplementary English tutorials (e.g., at home/a cram school) are all regarded as extramural exposure to English. Note that this is different from EE Sundqvist (2009) coined and defined. We set out to focus on the English activities beyond the time spent on compulsory mainstream English class.

Studies related to young non-English-L1 learners’ extramural English exposure are limited to date, and they have mostly been conducted in Western contexts. Most researchers in these contexts have found that young learners had abundant exposure to English outside class. For example, De Wilde et al. (2020) found that at least three-quarters of their participants, 780 ten-to-twelve-year-old children in Belgium, were exposed to English daily through games, social media, and television. In Iceland, Sigurjónsdóttir and Nowenstein (2021) found similarly that about two-thirds of the ten-to-twelve-year-old participants were exposed to spoken English on a daily basis. However, the overall picture seems very different in the Asian contexts within which substantial numbers of EFL children reside. A survey carried out by Tsang (2023a) revealed that primary-school children from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan generally spent a very small amount of time receiving spoken English outside class. Although later, Tsang and Lam (2024) found that over 90 % of Hong Kong junior-secondary-school participants had informal exposure to English outside class, the actual amount of exposure time was also very low (the estimated medians around 3–7 h monthly). These participants exposed themselves to English through seven channels: Games, videos/movies, songs, print (e.g., magazines), human-to-human communication (e.g., texting; face-to-face conversations), audio-and-print materials (e.g., audiobooks), and audio-only materials (e.g., podcasts).

2.2 Socioeconomic status (SES)

SES represents a stratifying measure that indicates a family’s income level and, in many cases, the educational attainment of either the mother, the father, or both (Pace et al. 2017). SES has been found to affect the linguistic and cognitive development of children in early childhood (Hackman and Farah 2009; Pace et al. 2017). Lee and Lee (2021) observed that lower SES students are likely to be confronted with challenges in key areas related to academic motivation and experience with technology in FL learning (e.g., access to computers). Sun et al. (2015), having adopted maternal education levels as a proxy for SES, found that EFL learners with more educated mothers would experience a greater likelihood of out-of-class English practice and vocabulary learning. In essence, learners having more resources, socially and financially, tend to have more opportunities to access EFL resources outside class (Hu 2009). Poorer and/or less educated parents tend to lack the means to educate and invest themselves and/or their children in the FL; they often have difficulty in supporting their children’s FL learning and exposure in extramural settings as well as higher SES families can. Forey et al. (2016) reported some parents in Hong Kong feeling insecure and a lack of confidence about involving in their children’s English learning such as through reading aloud to them. This indicates that parents’ own competence (and somewhat indirectly educational levels) can play a role in children’s success in FL learning.

Although many educational researchers take SES into account, most have incorporated only one or two measures (e.g., only maternal education) in their studies. Examining a wider range of SES variables would yield a more granular understanding of the relationships between SES and extramural English learning, thereby allowing more nuanced conclusions and constructive implications to be drawn. We set out to address this gap in the current study.

2.3 FL vocabulary

Unsurprisingly, previous studies have reported a generally positive relationship between extramural English exposure and proficiency levels among young FL learners (e.g., Leona et al. 2021; Lindgren and Muñoz 2013; Puimège and Peters 2019; Sylvén and Sundqvist 2012; Tsang 2025). Many researchers investigated vocabulary as a proxy for proficiency. Puimège and Peters (2019), for example, had 560 Dutch-speaking children in Belgium complete vocabulary tests and a questionnaire. Although these children had not begun to receive formal English education at that time, a positive relationship was found between English gaming and TV viewing and learners’ performances on an English vocabulary test. Leona et al. (2021) recruited 298 fourth-grade Dutch primary-school children in the Netherlands in their study. Using questionnaires and vocabulary tests, they found that extramural English engagement via entertaining media (e.g., films) and family (e.g., speaking English at home) were, overall, positively related to vocabulary test scores. These positive findings make good sense as extramural English exposure dovetails some important principles for successful vocabulary learning, such as receiving large amounts of input and having opportunities for repetition and noticing (Coxhead and Bytheway 2015). This small body of research has mostly been conducted in European contexts, yet very few relevant studies have been conducted in Asia. Also, while researchers have employed various validated vocabulary tests in their studies (e.g., Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test in Leona et al. 2021), there is a general lack of examination of learners’ mastery or gains in vocabulary at different frequency levels. These levels are commonly categorized as the most frequent 1,000 words, the most frequent 1,001–2,000 words, and so forth (e.g., Webb et al. 2017). It is important to examine learners’ mastery of different levels closely such that specific implications can be drawn for effective vocabulary learning and teaching (e.g., medium of instruction and mastery of different frequency levels in Lo and Murphy 2010). The current study therefore set out to fill this gap in a bid to illuminate a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between vocabulary learning and extramural English exposure.

3 The study

This article reports part of a one-year longitudinal study on young EFL learners’ proficiency and engagement with English outside mainstream schools in the context of Hong Kong. Different from many other cities/countries in Asia, English has a special status in Hong Kong. It is one of the official languages used by the Government and various industries. Although many locals do not have much exposure to English naturally on a daily basis, there are multiple platforms through which children can engage with English outside class, especially the Internet and the media. Some children are taken care of by foreign domestic helpers and English may be spoken as a lingua franca. For these children, English is often used as a language of communication.

The research instruments employed were a vocabulary test and an individual interview. At the beginning of the study (Timepoint 1; T1), the participants took a passive vocabulary test (see Measures and procedures below). After a lapse of about 1 year (Timepoint 2; T2), they sat the same test again. The interviewers then contacted the parents/guardians and the children to schedule individual interviews. The specific research questions were as follows:

What kinds of extramural exposure to English do EFL children in Hong Kong receive, and how frequent is each kind of exposure?

Are parents’ levels of education and household incomes related to the various kinds of extramural exposure?

Which type(s) of extramural exposure is/are significantly related to vocabulary gains?

4 Methods

4.1 Participants

Ninety Grade-5 EFL children (M age = 9.988, SD = 0.570; Males = 46, Females = 44) studying at three primary schools in Hong Kong participated in the study voluntarily. Although located in different districts in Hong Kong, the three participating schools offered typical EFL education to native-Chinese-speaking children from Grade 1 onwards. They could therefore be generally considered as typical EFL learners in the context of Hong Kong. As shown by the absence of between-school significant differences in both the pre- and post-test scores, the participants from the three schools had comparable vocabulary sizes at both T1 and T2 of the study. Ethical approval was granted by the institution with which the first author is affiliated, and consent to participate was sought from the participating children and their parents/guardians.

The children participants, together with their parents/guardians, were invited to participate in an individual interview after the post-test was completed. In total, 90 face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained assistants. The interviewees were 77 mothers, seven fathers and one aunt (a guardian), and there were five sessions in which both fathers and mothers attended. The assistants first checked to establish the interviewees’ eligibility (i.e., they had a sound knowledge of the children’s English exposure from T1 onwards). The assistants invited ineligible parents/guardians to recommend another family member/guardian who had the required knowledge to take part in the interview instead. The children were also encouraged strongly to participate in the interviews as far as possible and they were present in 82 of the 90 interviews.

4.2 Measures and procedures

4.2.1 EFL exposure

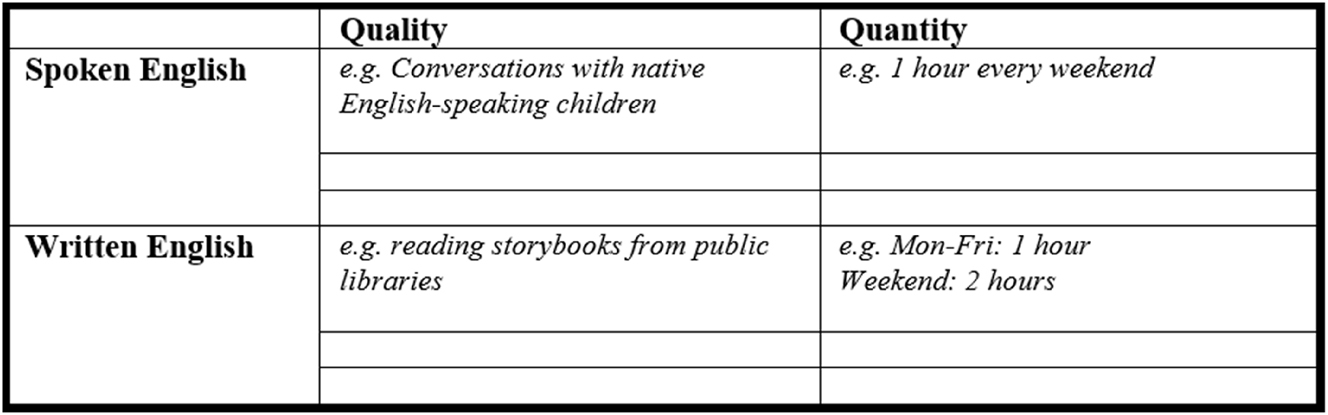

The children’s exposure to English from T1 to T2 was established from the individual structured interviews. The regularities in these young children’s habits and timetables, and the parents’/guardian’s long-term presence immensely facilitated the recall of events. In each session, the trained assistant, the parent(s)/guardian, and the child (in 82/90 interviews), collaborated to co-construct all English exposure beyond the regular EFL lessons the child had received in the past year. To better structure the recall, the assistants focused first on supplementary classes (i.e., English tutorial classes; homework completion classes; see Table 1 for definitions), then English homework, and finally, other exposure such as self-initiated/parent-assigned tasks. To assist the interviewees in their recall, the interviewers guided them to consider two aspects: Spoken (i.e., listening and speaking) and written (i.e., reading and writing) English. The assistants would ask for clarification and examples, and noted the quality (i.e., type) and quantity (i.e., amount of time) of exposure on a log sheet (Figure 1) throughout each interview. At the end of each interview, the assistant summarized the profile for the interviewees as a form of member check. This bottom-up qualitative approach yielded a holistic and relatively accurate picture of a child’s total English exposure beyond the mainstream EFL class over a 1-year period. Each interview lasted around 20–60 min, depending largely on the interviewees’ responses (e.g., an interview would end quickly when the child had little to no out-of-class exposure). All the interviews were conducted in Chinese (all interviewees’ and interviewers’ first language). For more details about the interview and data collection in relation to EFL exposure, see Tsang 2023c).

Definitions and examples of English exposure the participants had from T1 to T2.

|

Category |

Definition/elaboration |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

English tutorial classes |

Supplementary (usually fee-paying) classes that primarily aim to increase learners’ English proficiency. Their focus can be narrow (e.g., grammar; writing) or broad (e.g., all four macro-language skills). |

One-to-one private tutorial sessions at home; small-group classes in tutorial schools |

|

Homework completion classes |

Supplementary (usually fee-paying) classes in which tutors assist learners to complete their homework assigned by teachers in mainstream schools. When the homework is completed, the children are usually asked to do revision or additional exercises. |

One-to-one private sessions at home; small-group classes in tutorial schools |

|

English homework |

Tasks assigned by English teachers to do outside class |

Exercise sheets; writing tasks |

|

General informal exposure (GIE) |

This represents informal engagement with English for entertainment, learning, or communicative purposes. The subcategories are shown below. |

– |

|

– Videos |

Receiving audio-visual input with or without written English input (e.g., captions) |

Cartoons; movies |

|

|

Receiving written English input |

Books; online texts |

|

– Songs |

Receiving spoken English input alongside melodies |

Children songs; pop music |

|

– Oral communication |

Situations where learners engage in oral communication using English. |

Conversing with a non-Chinese-speaking domestic helper; talking with native English speakers |

|

– Games |

Receiving spoken and/or written English input while playing games |

Mobile games; games on Nintendo switch |

|

– Applications |

English learning applications available on phones and/or computers |

Duolingo |

|

– Drama |

Only one participant engaged in drama performance activities in English. |

– |

The interview log sheet.

4.2.2 Parents’ education levels and household income

SES was indicated by both parents’ highest education levels and household incomes. These were also solicited during the individual interviews described above.

4.2.3 Vocabulary size

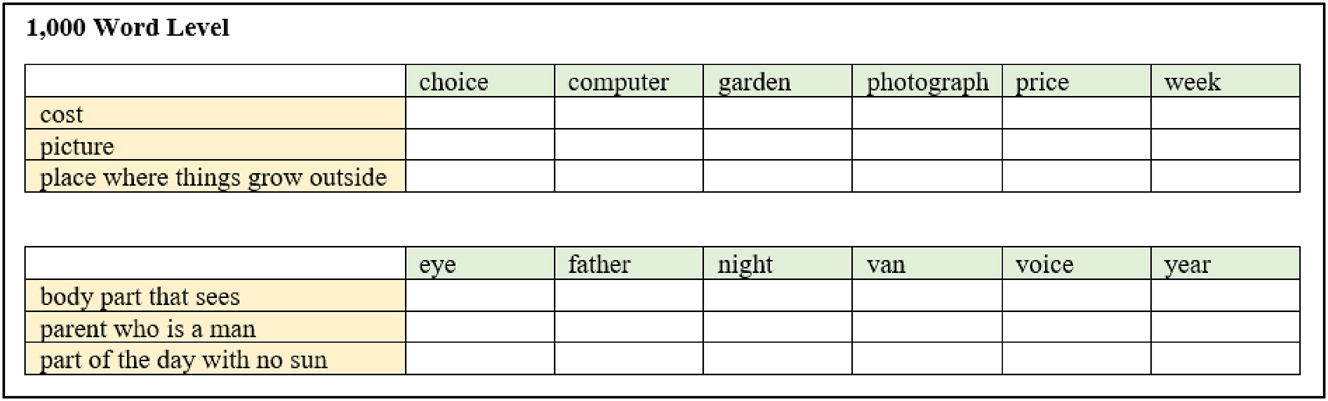

The updated Vocabulary Levels Test (Webb et al. 2017; accessible directly via Paul Nation’s resources website, Nation n.d.) was administered to the children. The first three levels, namely 1,000, 2,000, and 3,000 word levels, were administered. As agreed by the first author and the participants’ English teachers, these tests covered a wide array of words from very simple (e.g., eye and box in level 1,000) to difficult ones (e.g., enthusiastic and approximate in level 3,000) for the target participants, hence highly appropriate for use, especially in a longitudinal study. There were 30 items in each level, yielding a total of 90. This passive vocabulary test was slightly re-formatted and colored to make the task clearer for the children, who were told that the words or phrases in yellow were definitions (see Figure 2). They were required to tick one of the words in green that matched each definition. The test, therefore, essentially measured passive vocabulary size. All the participants in the same school completed the test simultaneously in classrooms on Saturdays. No time limit was given and the participants were told explicitly and repeatedly that they were not allowed to guess any answers (as doing so would affect the accurate measurement of their genuine vocabulary sizes). The tests were checked whenever possible as the administrators collected them (e.g., verbally checking their understanding of a few words in green that children ticked, to make sure they were not ticking the boxes randomly).

Part of the vocabulary test administered in the study (adapted from Webb et al. 2017).

4.3 Data entry and analysis

The exposure information on the interview log sheets was first entered directly into a spreadsheet. The types of exposure were then categorized using a bottom-up approach (e.g., watching cartoons, Netflix, and YouTube all grouped under ‘videos’). The complete list of exposure categories, together with definitions and examples, is shown in Table 1. The total amount of time each individual spent on each category was summed for later analysis. As for the indicators of SES, following Lau and Cheng (2016), each parent’s highest education level was categorized into one of the following five levels: (1) junior high school or below, (2) senior high school, (3) pre-degree, (4) bachelor’s, and (5) master’s or above. Their household income, which was in Hong Kong dollars, was entered directly into the spreadsheet. For the vocabulary tests, one mark was awarded for each correct answer, yielding a total of 30 marks per level. Tests not completed seriously (e.g., ticking all the boxes in the same column in the entire test) were discarded. Each test was marked by one assistant and cross-checked by another. Discrepancies were discussed. As the current study focused on vocabulary gains from T1 to T2, tests showing a total score difference (i.e., T2–T1) of 0 or below were not analyzed. Tests with any negative score difference at 1,000, 2,000, or 3,000 levels were also discarded from this study.

To address RQ1, descriptive statistics were used. As the exposure data did not generally follow normality, non-parametric tests (Spearman’s correlations and the Mann-Whitney U test) were used to address the relationships under investigation in RQ2 and RQ3. To shed further light on how exposure could potentially be related to vocabulary gains, the profiles of the five most improved participants were also analyzed and are reported below.

5 Results

5.1 The participants’ exposure to English (RQ1)

Table 1 shows the categories, together with their definitions/elaboration and examples, of all types of exposure the children had outside the mainstream EFL class over a one-year period. There were two types of common academic classes, English tutorial and homework completion classes. The interviewees also reported a range of self-initiated or parent-assigned activities through which their children were exposed to English.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the various kinds of English exposure the participants engaged with from T1 to T2. Academically, around 72.222 % and 28.889 % of the participants took tutorial and homework classes respectively. Everyone (except for one missing datum) had experience with homework. 75.556 % engaged in informal activities, the most frequent being videos (52.222 %), followed by print (36.667 %), songs (13.333 %), and oral communication (12.222 %). Fewer than 10 participants were exposed to English through games, applications, or drama. The skewness and kurtosis values indicate that the data were generally not normally distributed.

Descriptive statistics for the participants’ exposure to English.

| Exposure | The ‘yes’ group onlya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | M | SD | Range | Mdn | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Tutorial classes | 65 | 25 | 60.207 | 84.030 | 1–624 | 38.667 | 5.108 | 32.324 |

| Homework classes | 26 | 64 | 290.860 | 208.271 | 12–832 | 303.334 | 0.647 | 0.081 |

| Homework (hours per school day) | 89 | 1b | 0.655 | 0.387 | 0.25–2 | 0.5 | 1.756 | 3.408 |

| GIE | 68 | 22 | 321.140 | 533.728 | 2–3,692 | 130.5 | 4.244 | 23.719 |

| – Videos | 47 | 43 | 259.139 | 329.464 | 2–1,404 | 130 | 1.981 | 3.530 |

| 33 | 57 | 97.843 | 137.302 | 4–728 | 52 | 3.274 | 13.771 | |

| – Songs | 12 | 78 | 59.722 | 53.540 | 4–182 | 52 | 1.420 | 1.551 |

| – Oral comm. | 11 | 79 | 233.409 | 384.559 | 1–1,352 | 144 | 2.916 | 9.031 |

| – Games | 5 | 85 | 530.400 | 612.409 | 52–1,300 | 104 | 0.668 | −2.945 |

| – Applications | 4 | 86 | 110.750 | 84.669 | 15–182 | 123 | −0.282 | −4.396 |

| – Drama | 1 | 89 | 50 | – | – | – | – | – |

-

aThe total number of hours from T1 to T2 except homework; bmissing datum as the interviewee was uncertain about this.

5.2 Correlations between parents’ education levels, household income, and exposure (RQ2)

As shown in Table 3, the medians of the highest qualifications for both parents were 2 (senior high school). The average household income was around HKD35000 but there was a large variation, as indicated in the standard deviation (SD = HKD23219.246). These background variables did not seem to be significantly correlated with most kinds of exposure. However, income was significantly correlated with GIE, r s = 0.225, p = 0.038. Videos were the only type of exposure found to be positively correlated with household income, r s = 0.356, p = 0.017. If accepting a slightly higher Type-1 error rate of 10 %, to make up for the low power in this small sample size, GIE was also potentially related to both father’s (r s = 0.206, p = 0.064) and mother’s education (r s = 0.176, p = 0.097), with a small effect.

Descriptive statistics for and Spearman correlations between parents’ education levels, household income, and exposure.

| Spearman correlation with the ‘yes’ group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdnˆ/M(SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | Tutorial classes | Homework classes | Homework | GIE | Videos | Songs | Oral comm. | ||

| Father edu. (level 1–5) |

2ˆ | 0.974 | 0.253 | 0.052 | 0.056 | −0.073 | 0.206, p = 0.064 | 0.091 | 0.123 | 0.094 | −0.115 |

| Mother edu. (level 1–5) | 2ˆ | 1.008 | 0.783 | 0.022 | 0.044 | −0.128 | 0.176 p = 0.097 |

0.226 | 0.192 | −0.118 | −0.168 |

| Income (HKD) |

35383.721 (23219.246) | 1.327 | 1.617 | -0.003 | 0.032 | 0.070 | 0.225 p = 0.038 |

0.356 p = 0.017 |

0.081 | −0.411 | 0.023 |

-

HKD, Hong Kong Dollars; Spearman correlations: All ps > 0.10 unless otherwise stated.

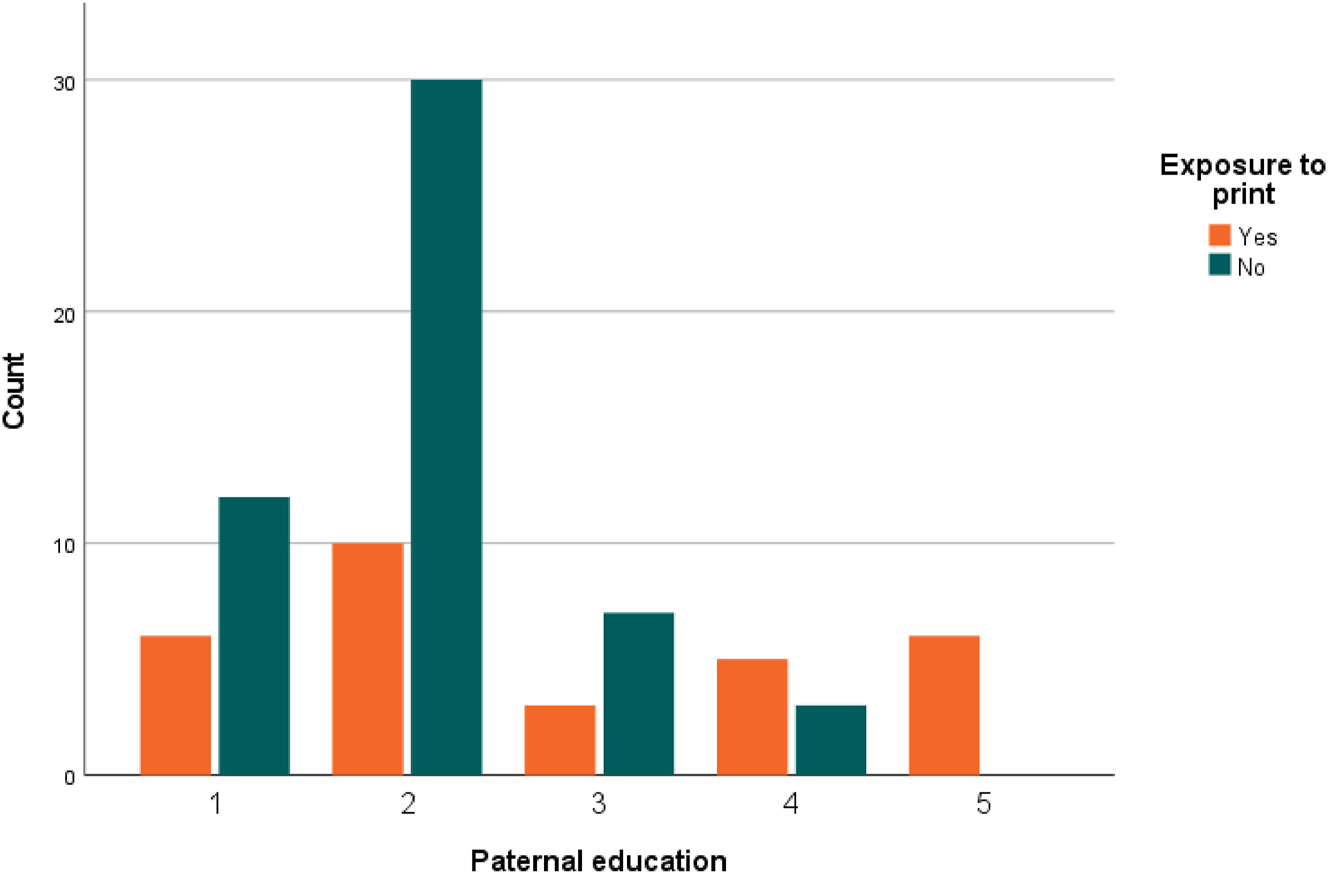

To compare if parents’ education levels and household income were significantly different between the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ exposure groups, the Mann-Whitney U tests were administered. No significant differences were found in any of the comparisons (see Table A in the Appendix) except for print and father’s education, U = 553, p = 0.019, which had a small to medium effect, r = −0.259 (Field 2018). Figure 3 presents the participants' exposure to print categorized by paternal education.

The participants’ exposure to print categorized by paternal education.

5.3 T1 and T2 vocabulary scores (RQ3)

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics for the pre- and post-vocabulary test scores for all participants. The average scores at T2 were higher than the corresponding scores at T1. Throughout the year, the participants, on average, gained around 2–3 words at the 1,000 level and about 2 words at the 2,000 level, but the gain at the 3,000 level was minimal (0.658 words only). Overall, the participants gained slightly more than an average of 5 words from T1 to T2.

Descriptive statistics for pre- and post-vocabulary test scores (all participants).

| 1,000 level | 2,000 level | 3,000 level | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |

| M | 11.738 | 14.608 | 3.667 | 5.722 | 0.868 | 1.494 | 16.551 | 21.550 |

| SD | 8.864 | 9.417 | 6.476 | 8.114 | 3.271 | 4.359 | 16.596 | 19.772 |

| Min. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max. | 29 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 21 | 26 | 78 | 85 |

| M T2-T1 (SD) | 2.688 (4.379) | 2.077 (3.559) | 0.658 (2.358) | 5.413 (7.117) | ||||

The present study focused on vocabulary development. Therefore, those who did not show improvement or who did worse were removed from further analyses. The cleansed results are shown in Table 5. This group of learners gained around 3–5 words at each level and approximately 8 words in total. As a reviewer aptly pointed out, the genuine gains in these learners’ vocabulary size would likely be much larger. For instance, if to extrapolate, gaining 3 out of 30 words at a level equates to 10 % of the words at that level. The paired-sample t-tests results are also shown in Table 5. All three levels and the total scores showed that the differences were statistically significant (all ps < 0.001) and the effect sizes were large (all ds > 1).

Descriptive statistics of pre- and post-vocabulary test scores (only participants showing vocabulary gains).

| 1,000 level | 2,000 level | 3,000 level | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |

| M | 11.259 | 15.793 | 4.930 | 9.116 | 1.941 | 5.647 | 16.947 | 24.695 |

| SD | 8.662 | 8.891 | 6.930 | 8.559 | 4.465 | 7.017 | 16.118 | 19.471 |

| Min. | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Max. | 29 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 17 | 26 | 71 | 85 |

| M T2-T1 (SD) | 4.535 (3.609) | 4.186 (3.486) | 3.706 (3.331) | 8.322 (5.876) | ||||

| Range of score increase | 1–18 | 1–16 | 1–11 | 1–26 | ||||

| t(df) | 9.569(57) | 7.873(42) | 4.587(16) | 10.852(56) | ||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| d | 1.256 | 1.201 | 1.113 | 1.437 | ||||

To find out the relationships between the gains in scores and various kinds of exposure, Spearman correlations were performed. The results are presented in Table 6. No statistical difference was found at levels 1,000 or 3,000. GIE was the only area showing a small to medium significant correlation with gains in vocabulary at level 2,000 (r s = 0.330, p = 0.031) and overall vocabulary (r s = 0.320, p = 0.013). Interestingly, time spent on tutorial classes and homework were found to be associated negatively with total vocabulary gains (r s = −0.273, p = 0.036 for tutorial classes; r s = −0.291, p = 0.025 for homework).

Correlations between vocabulary gains and various kinds of exposure.

| Gain in lv. 1,000 | Gain in lv. 2,000 | Gain in lv. 3,000 | Total gain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r s | p | r s | p | r s | p | r s | p | |

| Tutorial classes (hours) | −0.113 | 0.396 | −0.223 | 0.150 | 0.043 | 0.871 | −0.273 | 0.036* |

| Homework classes (hours) | −0.024 | 0.858 | -0.025 | 0.873 | −0.008 | 0.974 | −0.049 | 0.715 |

| Homework (hours) | −0.176 | 0.186 | −0.237 | 0.125 | −0.005 | 0.983 | −0.291 | 0.025* |

| GIE | 0.083 | 0.535 | 0.330 | 0.031* | 0.186 | 0.475 | 0.320 | 0.013* |

| – Videos | 0.106 | 0.582 | 0.138 | 0.521 | 0.409 | 0.211 | 0.222 | 0.230 |

| −0.189 | 0.413 | 0.115 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.200 | 0.348 | |

-

*p < 0.05; 10 or fewer pairs were not analyzed.

The profiles of the five most improved students are illustrated in Table 7. These students gained 19 to 26 words from T1 to T2. All of them had tutorial classes during the period although the amount of such tuition was not high (from 4 to 34.667 h only throughout the whole year). Only #5 attended homework classes. #1–#4 had substantial amounts of engagement with GIE, placing them above the 90th percentile (786.5 h) among all the participants. All five of them were exposed to English through videos and four of them also had exposure to oral communication.

Profiles of the five most improved participants.

| Participant #1 | Participant #2 | Participant #3 | Participant #4 | Participant #5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score gained | 26 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 19 |

| Tutorial classesa | 10 | 4 | 24 | 34.667 | 18 |

| Homework classesa | – | – | – | – | 520 |

| Homework (hours daily from T1-T2) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| GIEa | 884 | 996 | 1586.5 | 884 | 104 |

| – Videosa | 104 | 728 | 1,404 | 416 | 104 |

| – Printa | 728 | 8 | – | 312 | – |

| – Oral comm.a | 52 | 260 | 182.5 | 156 | – |

-

aTotal hours from T1 to T2.

6 Discussion

This study set out to investigate young EFL learners’ extramural English exposure and its relationships with SES and vocabulary gains over a one-year period. The three research questions are answered below. The first question focused on the types of English exposure in the extramural EFL context of Hong Kong and their frequencies. A range of exposures was found in both academic (English tutorial classes, homework completion classes, and English homework) and non-academic domains (general informal exposure such as videos, print, and songs). English homework was by far the most common out-of-class English activity. This is not surprising, as assigning homework to students is a very common practice in education in Hong Kong, as in many other places around the world (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2014; Tsang et al. 2025b). The findings also support that English tutorial classes seem very common, echoing the ubiquity of supplementary education in Asia and beyond (see Tsang et al. 2019). Of the less academic activities, receiving English input via videos was the most common. This echoes strongly the findings in recent studies in European contexts in which children were found to be exposed abundantly to viewing platforms (e.g., De Wilde et al. 2020; Sigurjónsdóttir and Nowenstein 2021). However, only a few participants in the current study had experienced exposure to English through gaming, which was actually found to be one of the most popular types of extramural English engagement for the European children in those studies. It is also important to note that very wide frequency ranges were found in exposure categories. The medians for all the informal-exposure categories revealed that at least half of the participants did not engage with these activities to any large extent over the one-year period. As seen in Table 2, the medians only ranged from 52 to 144 h for one entire year. Therefore, while these learners did expose themselves to English outside class, their exposure did not seem to be sufficient to address the problem of the lack of target language exposure in FL settings.

This second research question homed in on the relationship between SES and exposure. In contrast to our speculation, and different from studies often reporting positive relationships between SES and children’s learning opportunities (e.g., Anderson et al. 2003; Lau and Cheng 2016), in general, no differences in income were found between the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ exposure groups. One possible reason is that various exposure activities can be made freely available for children nowadays, including free tutorial classes organized by charitable organizations, and free YouTube videos on mobile phones with access to the Internet. This is perhaps why household income may not have been significantly related to the out-of-class activities with which learners can engage. With regard to parental education levels, there seems to be a weak positive relationship between fathers having higher levels of education and children’s print exposure. As Barnett (2008) noted, it is important to pay attention to paternal characteristics in SES research since fathers also play an important role in children’s involvement in out-of-school activities. In the current study, the higher-educated fathers (levels 4 and 5 in Figure 3) had a high proportion of children who engaged with English reading. It remains to be explained why the relationship only existed with print but not with other categories, and why such a relationship did not exist with mothers’ education, a variable that has been recognized widely as important for children’s education and achievements (e.g., Csapó 2003; Duncan and Paradis 2020; Yeung et al. 2025). In terms of the correlations between SES and amounts of exposure, most pair-wise comparisons were, surprisingly, not statistically significant in the current study. Income was the only proxy in SES that had significant relationships with videos and GIE. The relationship between having more financial resources and greater opportunities for informal exposure, for example having tablets for viewing subscribed TV channels, is axiomatic (Hu 2009; Lee and Lee 2021). However, maternal and paternal education were not found to be associated with any category of exposure unless one is lenient with Type-1 error (p < 0.10). In this case, both parents’ education levels were positively correlated with GIE, corroborating the higher parental education attainments and greater children’s out-of-class learning opportunities reported in previous studies (e.g., Sun et al. 2015).

Finally, RQ3 was about vocabulary gains in relation to exposure over a one-year period. While increase in vocabulary was seen at all 1,000, 2,000, and 3,000 levels, gains were only related to exposure in a few pair-wise comparisons. This adds to our deeper understanding of the positive relationships between extramural English exposure and language proficiency among young FL learners (e.g., Leona et al. 2021; Lindgren and Muñoz 2013; Puimège and Peters 2019). The findings in the current study highlighted that not all types of out-of-class activities were related to proficiency gains. Two of the significant pairs showed that GIE was positively correlated with gains in level 2,000 words and total vocabulary gains. It is difficult to explain why such a relationship only existed at the 2,000 level. It is largely unclear why a positive relationship was not found with the level 1,000 words, given that they should be the most common in GIE. Words at the 3,000 level might be beyond the abilities of most participants so that they could not yet master these words well even if exposed to them. Alternatively, as level 3,000 words are less common, the learners had probably not encountered them enough to be able to master them. The significant negative correlations between tutorial classes/homework and total gains are also difficult to decipher. It seems to imply, counter-intuitively, that additional EFL classes and longer time spent on homework are not related to increasing learners’ vocabulary size. Indeed, previous studies have also shown that supplementary education (e.g., Smyth 2008; Tsang et al. 2019) and time spent on homework (Fernández-Alonso et al. 2019; Tsang et al. 2025a) are not necessarily (perceived to be) positively related to better academic achievements. Taking into account the two positive correlations found, it may be possible that learners spending more time attending tutorials had less time or were less devoted to GIE, which was found to be positively related to performance on the vocabulary test. Further support can be seen in the five case. While the median number of hours for tutorial classes was 38.667 for all the participants, the five most-improved participants attended much fewer hours of tutorials. The first four participants also had some of the highest GIEs throughout the year, from about 900 to 1,600 h.

The findings generate a number of important implications for FL researchers and practitioners. First, while academic out-of-class English engagement is common, the amount of GIE does not seem to have been high in the current study, especially when compared to studies conducted in Europe (see e.g., Puimège and Peters 2019 in Belgium; Sigurjónsdóttir and Nowenstein 2021 in Iceland; Sundqvist and Uztosun 2024 in Scandinavia). It can be argued that English is already not so uncommon in Hong Kong due to its history with the UK and its status as an international city; EFL children in other Asian contexts may receive even less GIE. Since young children are unlikely to be self-motivated to engage with a foreign language, researchers, educators, and parents need to take a more proactive role in this regard. For instance, parents can introduce English cartoons and songs to their children, and enjoy these with them if time allows. Teachers can design school-based programs that encourage learners to engage with such voluntary exposure to English outside class. Thanks to technology, GIE (e.g., songs and videos via YouTube) is easily accessible and often free or available at a low cost nowadays. It can also be accessed conveniently almost anywhere, at home or while commuting. Second, SES, on the whole, seems to be related only weakly to extramural English exposure. Looking through a sanguine lens, we might say that social inequality is perhaps not as serious an issue as one may think, likely due to the fact that many out-of-class academic/non-academic activities – at least in the case of Hong Kong – are free or available at a low cost. Therefore, parents who are relatively less educated or who earn less will not necessarily be forced to deprive their children of opportunities to be exposed to extramural English. Relatedly, the findings also underscore the importance of accounting for fathers’ background in research into children’s education. Therefore, methodologically, educational researchers should consider widening their scope beyond maternal education when examining SES (e.g., Barnett 2008). Third, it is interesting to note that academic engagements (supplementary classes, homework completion classes, and homework) were not related to vocabulary gains at all, echoing previous studies that have demonstrated mixed findings regarding the effectiveness of these out-of-class academic engagements (e.g., see Cooper et al. 2006; Fernández-Alonso et al. 2019; Smyth 2008; Tsang et al. 2019; Tsang et al. 2025a). While it is uncertain if fruits can be reaped from attending these classes and completing homework, GIE has been found to be promising. Therefore, it is important to reiterate that adults should be more proactive in guiding, motivating, and involving these young learners in GIE.

7 Conclusion

The findings of this longitudinal study have contributed important new knowledge to our understanding of young learners’ extramural English exposure in an Asian city, Hong Kong, and how it is related to SES and vocabulary learning. The findings showed that the participants received extramural English input through doing homework, and more than two-thirds of them attended tutorials and engaged with general informal exposure to English (GIE) such as watching videos and reading books. (Marginally) positive correlations were found between GIE, household income, and parents’ levels of education. GIE was also found to be related to total vocabulary gains over the one-year period, especially at the 2,000-word level. However, due to various limitations, much remains to be explored in future studies. First, the sample sizes were too small in some categories in the analyses (e.g., different types of GIE), making it difficult to detect any statistically significant relationships. Therefore, if possible, researchers should consider recruiting a larger sample size in similar longitudinal studies in the future especially because it is likely that there are many different categories of ways of language exposure outside class. Second, only a passive written vocabulary test was administered. Productive and aural vocabulary tests can also be used in future studies to shed more light on how different kinds of extramural English exposure are potentially related to different aspects of vocabulary development. Also, some participants might not have obtained points not because they did not understand the target items in the vocabulary test, but rather, there could be words in the definitions they did not know. Researchers in the future might consider replacing the definitions (the non-target linguistic items) in the test with learners’ first languages or using pictures instead. Third, although there was a one-year gap between timepoint one and two, minor changes such as randomization of the order of items could be made to minimize issues related to repetitive testing. Finally, although every effort was made to ensure that the exposure data collected during the interviews were as accurate as possible, the interviewing was carried out only once. If possible logistically, multiple interviews could be arranged with shorter time gaps in between to facilitate the interviewees’ recall.

Funding source: Language Learning Early Career Researcher Program

Funding source: Direct Grant for Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants, teachers, and assistants in this project. Many thanks also go to the editor and the reviewers for their time and constructive comments.

-

Author contributions: Art Tsang: proposal drafting, grant received, participant recruitment, project management, data collection and entry, data analysis, writing – abstract, introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion, proofreading and revising whole manuscript before submission. Noble Lo: writing – introduction, literature review, and discussion.

-

Conflict of interest: None.

-

Research funding: Language Learning Early Career Researcher Program and Direct Grant for Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, both awarded to the first author.

-

Ethics statement: The study has been approved by an ethics committee of the university with which the first author is affiliated. All participants took part in the study voluntarily.

Results from the Mann-Whitney U tests: differences between the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ exposure group in parents’ education levels and household income.

| Paternal education | Maternal education | Household income | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tutorial classes | U = 645, p = 0.577 | U = 712.5, p = 0.329 | U = 731.5, p = 0.767 |

| Homework classes | U = 635.5, p = 0.634 | U = 792.5, p = 0.703 | U = 713.5, p = 0.768 |

| Others | U = 537, p = 0.337 | U = 637.5, p = 0.261 | U = 543.5, p = 0.232 |

| Videos | U = 713.5, p = 0.273 | U = 902.5, p = 0.449 | U = 894.5, p = 0.961 |

| U = 553, p = 0.019 | U = 763.5, p = 0.108 | U = 719, p = 0.228 | |

| Songs | U = 318.5, p = 0.874 | U = 325, p = 0.066 | U = 299, p = 0.141 |

| Oral comm. | U = 257.5, p = 0.259 | U = 371, p = 0.396 | U = 323, p = 0.246 |

References

Anderson, J. C., J. B. Funk & R. Elliott. 2003. Parental support and pressure and children’s extra curricular activities: Relationships with amount of involvement and affective experience of participation. Applied Developmental Psychology 24(2). 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0193-3973(03)00046-7.Search in Google Scholar

Barnett, L. A. 2008. Predicting youth participation in extra curricular recreational activities: Relationships with individual, parent, and family characteristics. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 26(2). 28–60.Search in Google Scholar

Capizzano, J., K. Tout & G. Adams. 2000. Child care patterns of school-age children with employed mothers. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.Search in Google Scholar

Cooper, H., J. C. Robinson & E. Patall. 2006. Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of Educational Research 76(1). 1–62. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076001001.Search in Google Scholar

Coxhead, A. & J. Bytheway. 2015. Learning vocabulary using two massive online resources. In D. Nunan & J. C. Richards (eds.), Language learning beyond the classroom, 65–74. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Csapó, B. 2003. Cognitive factors of the development of foreign language skills. In 10th biennial conference of the European association for research on learning and instruction, 26–30. Padova, Italy.Search in Google Scholar

De Wilde, V., M. Brysbaert & J. Eyckmans. 2020. Learning English through out-of-school exposure. Which levels of language proficiency are attained and which types of input are important? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23(1). 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728918001062.Search in Google Scholar

Duncan, T. S. & J. Paradis. 2020. How does maternal education influence the linguistic environment supporting bilingual language development in child second language learners of English? International Journal of Bilingualism 24(1). 46–61.10.1177/1367006918768366Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, N. C. 2002. Frequency effects in language processing: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 24(2). 143–188. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263102002024.Search in Google Scholar

Fernández-Alonso, R., P. Woitschach, M. Álvarez-Díaz, A. M. González-López, M. Cuesta & J. Muñiz. 2019. Homework and academic achievement in Latin America: A multilevel approach. Frontiers in Psychology 10. 95.10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00095Search in Google Scholar

Field, A. 2018. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 5th edn. Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Forey, G., S. Besser & N. Sampson. 2016. Parental involvement in foreign language learning: The case of Hong Kong. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 16(3). 383–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415597469.Search in Google Scholar

Hackman, D. A. & M. J. Farah. 2009. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13(2). 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.003.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, G. 2009. The craze for English-medium education in China: Driving forces and looming consequences. English Today 25(4). 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266078409990472.Search in Google Scholar

Kusyk, M., H. L. Arndt, M. Schwarz, K. S. Yibokou, M. Dressman, G. Sockett & D. Toffoli. 2025. A scoping review of studies in informal second language learning: Trends in research published between 2000 and 2020. System 130. 103541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103541.Search in Google Scholar

Lam, Alex Lap-kwan & Art Tsang. 2025. Paper-based versus e-portfolios in FL writing: A mixed-methods study of young learners’ enjoyment and boredom. Computer Assisted Language Learning 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2025.2486148, In press.Search in Google Scholar

Lau, E. Y. H. & D. P. W. Cheng. 2016. An exploration of the participation of kindergarten-aged Hong Kong children in extra curricular activities. Journal of Early Childhood Research 14(3). 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718x14552873.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J. H. & H. Lee. 2021. The role of learners’ socioeconomic status and perception of technology use in their second language learning motivation and achievement. Language Awareness 32(2). 217–234.10.1080/09658416.2021.2014510Search in Google Scholar

Leona, N. L., M. J. H. Van Koert, M. W. Van Der Molen, J. E. Rispens, J. Tijms & P. Snellings. 2021. Explaining individual differences in young English language learners’ vocabulary knowledge: The role of extramural English exposure and motivation. System 96. 102402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102402.Search in Google Scholar

Lichtman, K. & B. VanPatten. 2021. Was Krashen right? Forty years later. Foreign Language Annals 54(2). 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12552.Search in Google Scholar

Lindgren, E. & C. Muñoz. 2013. The influence of exposure, parents, and linguistic distance on young European learners’ foreign language comprehension. International Journal of Multilingualism 10(1). 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2012.679275.Search in Google Scholar

Lo, Y. Y. & V. A. Murphy. 2010. Vocabulary knowledge and growth in immersion and regular language-learning programmes in Hong Kong. Language and Education 24(3). 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780903576125.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, C. & T. N. Y. Dang. 2023. Effect of L2 exposure, length of study, and L2 proficiency on EFL learners’ receptive knowledge of form-meaning connection and collocations of high-frequency words. Language Teaching Research 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688231155820.Search in Google Scholar

Mahoney, J. L., R. W. Larson, J. S. Eccles, H. Lord. 2005. Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson & J. S. Eccles (eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: Extra curricular activities, after school and community programs, 3–21. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.10.4324/9781410612748Search in Google Scholar

Marulis, L. M. & S. B. Neuman. 2010. The effects of vocabulary intervention on young children’s word learning: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research 80(3). 300–335. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310377087.Search in Google Scholar

Nation, I. S. P. 2013. Learning vocabulary in another language. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139858656Search in Google Scholar

Nation, P. n.d. Paul Nation’s resources. Victoria University of Wellington. https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/lals/resources/paul-nations-resources.Search in Google Scholar

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2014. PISA in focus: Does homework perpetuate inequities in education? In Psychology of classroom learning: An encyclopedia, 471–473. OECD Publishing Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Pace, A., R. Luo, K. Hirsh-Pasek & R. M. Golinkoff. 2017. Identifying pathways between socioeconomic status and language development. Annual Review of Linguistics 3. 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011516-034226.Search in Google Scholar

Puimège, E. & E. Peters. 2019. Learners’ English vocabulary knowledge prior to formal instruction: The role of learner‐related and word‐related variables. Language Learning 69(4). 943–977.10.1111/lang.12364Search in Google Scholar

Sigurjónsdóttir, S. & I. Nowenstein. 2021. Language acquisition in the digital age: L2 English input effects on children’s L1 Icelandic. Second Language Research 37(4). 697–723.10.1177/02676583211005505Search in Google Scholar

Smyth, E. 2008. The more, the better? Intensity of involvement in private tuition and examination performance. Educational Research and Evaluation 14(5). 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610802246395.Search in Google Scholar

Sun, H., R. Steinkrauss, J. Tendeiro & K. De Bot. 2015. Individual differences in very young children’s English acquisition in China: Internal and external factors. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19(3). 550–566. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728915000243.Search in Google Scholar

Sundqvist, P. 2009. Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on Swedish ninth graders’ oral proficiency and vocabulary. Karlstad University. DiVA Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:275141/FULLTEXT03.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Sundqvist, P. 2024. Extramural English as an individual difference variable in L2 research: Methodology matters. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190524000072.Search in Google Scholar

Sundqvist, P. & M. S. Uztosun. 2024. Extramural English in Scandinavia and Asia: Scale development, learner engagement, and perceived speaking ability. TESOL Quarterly 58(4). 1638–1665. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3296.Search in Google Scholar

Sylvén, L. K. & P. Sundqvist. 2012. Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL 24(3). 302–321.10.1017/S095834401200016XSearch in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art. 2023a. The roads not taken: Greater emphasis needed on ‘sounds’, ‘actual listening’, and ‘spoken input’. RELC Journal 54(3). 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882211040273.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art. 2023b. ‘The best way to learn a language is not to learn it!’: Hedonism and insights into successful EFL learners’ experiences in engagement with spoken (listening) and written (reading) input. TESOL Quarterly 57(2). 511–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3165.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art. 2023c. The relationships between spoken and written input beyond the classroom and young EFL learners’ proficiency. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688231211367, In press.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art. 2025. Relationships between formal and informal input, listening motivation, and listening proficiency among young EFL learners in Hong Kong. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2024-0250, In press.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art, Beatrice Yan-Yan Dang & Benjamin Luke Moorhouse. 2025a. An examination of learners’ homework engagement, academic achievement, and perceptions. Educational Studies 51(2). 174–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2022.2126295.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art, Daniel Fung & Alice Hoi Ying Yau. 2019. Evaluating supplementary and mainstream ESL/EFL education: Learners’ views from secondary- and tertiary-level perspectives. Studies in Educational Evaluation 62. 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art & Wai-Kan Lam. 2024. De-foreignizing English outside class: Junior-secondary-level EFL learners’ extramural English engagements and listening and reading proficiency. RELC Journal 56(2). 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882241229459.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art, Wai-Kan Lam & Benjamin Luke Moorhouse. 2025b. Young language learners’ perceptions of homework: Contrasting the views of children who find homework least and most boring. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12769, In press.Search in Google Scholar

Tsang, Art & Susanna Siu-sze Yeung. 2024. The interrelationships between young English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) learners’ perceived value in reading storybooks, reading self-efficacy, and proficiency. SAGE Open 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241293044.Search in Google Scholar

Uchihara, T. & J. Clenton. 2020. Investigating the role of vocabulary size in second language speaking ability. Language Teaching Research 24(4). 540–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818799371.Search in Google Scholar

Webb, S. 2015. Extensive viewing. In D. Nunan & J. C. Richards (eds.), Language learning beyond the classroom, 159–168. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Webb, S., Y. Sasao & O. Ballance. 2017. The updated vocabulary levels test: Developing and validating two new forms of the VLT. ITL - International Journal of Applied Linguistics 168(1). 34–70.https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.168.1.02Search in Google Scholar

Yeung, Susanna Siu-sze, Art Tsang, William Wing Chung Lam & Tammy Sheung Ting Law. 2025. Maternal education, classroom emotions, and literacy outcomes among grade 3/4 EFL learners. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 46(2). 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2187397.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.