Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

-

Aneela Anwar

, Ayesha Sadiqa

and Dongwhi Choi

Abstract

Hydroxyapatite/magnetite (HA-Fe3O4) nanocomposite materials that have the synergistic ability to produce heat when in direct bonding with a bone through HA are regarded competent hyperthermia therapies of bone carcinoma treatment. HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites with various magnetite concentrations (10, 20, and 30 wt%) were quickly synthesized using a novel continuous microwave-assisted flow synthesis (CMFS) process in a 5 min residence duration at the conditions of pH 11. In this process, initially, phase pure hydroxyapatite and superparamagnetic magnetite nanoparticles followed by a series of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites were formed, without a subsequent aging step. The obtained nano-product was physically analyzed using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area analysis, transmission electron microscopy, and X-ray powder diffraction analysis. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was used for the chemical structure analysis of the final nanocomposite product. Zeta potential measurements were carried out to determine colloidal stability associated with the surface charge of the nanocomposites. The magnetic properties were determined using a vibrating sample magnetometer. The results indicated the high magnetization property of the obtained nanoproduct, suitable for hyperthermia application. HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites have shown remarkable antimicrobial properties against E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Thus, the CMFS system facilitated the rapid production of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposite particles with fine particle size.

1 Introduction

The need for smarter, smaller, and multiphase nanoparticles in the field of nanochemistry has given birth to a newly emergent class of compounds called nanocomposite materials [1]. For the last few decades, considerable attention has been given to the formation and development of nanocomposite materials as exclusive, functional nanomaterials with enhanced properties [2,3]. Antibiotic resistance is becoming a major global public health problem as a result of human abuse and disrespect, numerous studies have investigated the use of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) in bacterial infection control [4,5]. The study of magnetic ceramic composite and its use in the biomedical area has been one of the most fascinating issues for academics over the past 10 years [6]. Nanomaterials have been the subject of several studies utilizing magnetic hyperthermia up to this point, but for practical medical use, they present a number of inescapable difficulties, the most prevalent of which is early toxicity [7,8,9].

A wide range of illnesses affecting the human body with genetic abnormalities in cells which lead to uncontrolled cell division, which spreads to other body areas is referred to as cancer [10,11]. It is one of the most devastating and terrifying diseases that, regardless of prosperous or poor countries, results in significant fatalities globally [12,13]. The existing therapies for cancer treatments are mainly based on surgical operations, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, genetherapy, hormonotherapy, and immunotherapy, which badly affect the patient’s life due to side effects associated with these therapies [14,15,16]. In conjunction with radiation or chemotherapy, magnetic hyperthermia is currently a popular cancer treatment option [17]. Hyperthermia is a type of non-invasive anticancer treatment in which a body part or tissue is subjected to an elevated temperature between 43 and 48°C to preferentially destroy or make the cancerous cells more susceptible to some other follow-up therapy [18,19,20]. The serious disadvantage associated with other therapies (IR radiation therapy, hot water, supersonic therapy, etc.) is that normal cells are also affected besides the cancerous cells. So therapies involving the heating of carcinomatous areas selectively and locally are strongly needed [21,22,23].

Many different materials have been created and tested to see how well they work in the treatment of cancer using hyperthermia. Bioactive ceramics have emerged as particularly beneficial among these materials [24,25]. As a typical bioactive substance, hydroxyapatite [Ca10(Po4)6(OH)2 or HA] is employed as bone cement, dental implants, drug delivery, and toothpaste ingredient due to its remarkable biocompatibility, osteoconductivity, bioactivity, chemical, and biological similarities with the mineral components of human bones and teeth [26,27,28]. The biocompatibility of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles with the human body is well recognized. Though, there is concern over the nanoparticle’s potential for long-term toxicity, the most efficient way to solve this issue is to utilize magnetic Fe-doped HA; however, incorporating Fe3O4 nanoparticles into HA matrices can also lessen the long-term harmful effects [8,29,30].

Because of their ability to produce heat under a hyperthermic high-frequency alternating magnetic field, superparamagnetic nanoparticles have attracted a lot of interest. There have been several published studies on the usage of these particles in hyperthermia [6,31,32]. Despite the fact that these magnetite nanocomposites are target-directed and biocompatible with the human body, it is preferable to mix them with a suitable bioactive substrate to avoid any potential long-term negative effects. The most efficient method for treating malignant bone tumors with heat is to use HA composite materials that include magnetite [29,33,34,35]. They have also been used as adsorbents [36,37,38,39] and catalysts [40,41] in recent investigations. Additionally, it has been observed that MNPs (Fe3O4) can induce bactericidal properties by inhibiting bacterial growth and viability [42]. In particular, magnetite-incorporated HA nanocomposites have huge potential to be used in biomedical applications, especially in bone cancer where destruction of cancerous cells as well as regeneration of bone tissue is desired [43,44].

The traditional methods for creating HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites have limitations since more ageing processes lead to the creation of these nanoparticles, which requires a longer reaction time. Thus, a straightforward procedure must be created for the quick formation of these bioactive nanocomposites with improved properties [29].

In this research, a simple unique one-pot continuous microwave flow synthesis methodology was used to create a variety of HA-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Utilizing a variety of optical and analytical techniques, the structural characterization, and magnetic and antimicrobial properties of these newly created nanocomposites were assessed.

2 Materials and methods

For the synthesis of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposite, iron source used was iron citrate (C6H5O7Fe·3H2O, 98%), while diammonium hydrogen phosphate [(NH4)2HPO4, 98%], calcium nitrate tetrahydrate [Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 99%], and ammonium hydroxide solution (NH4OH, 28 vol%) were used in the synthesis process. During all experimentation, deionized water was consumed.

2.1 Experimental method

2.1.1 Synthesis of hydroxyapatite

By using a continuous microwave-assisted flow synthesis (CMFS) technique, the pure nano-hydroxyapatite was synthesized at pH 10. In the synthesis process, the solutions of calcium nitrate (59 g) and diammonium hydrogen phosphate (19.8 g), were mixed together by pumping them at a flow rate of 20 mL min−1 to a T-piece during the continuous microwave assisted flow synthesis procedure. This original combination was linked to Teflon tubing of 8 m length, which was twisted into a household microwave oven (800 W) at low temperature, where the reaction was completed in 5 min. The white powder with ∼85 % yield was the resulting product.

The suspension that was collected in a beaker from the exit point was centrifuged at 4,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, a VWR vortex mixer was used to redistribute the wet residue in 45 mL deionized (DI) water for 5 min, following three additional centrifugation and washing sequences. The final product was obtained by freeze-drying the moist solid at 0.3 Pa for 24 h.

2.1.2 Synthesis of superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles

Using a continuous flow synthesis method, Fe3O4 nanoparticles were produced quickly in a shorter time period of just 5 min at pH 11. Citric acid (11.52 g) and iron nitrate (20.2 g), were injected from opposite directions to meet at a “T”-shaped mixer during this procedure. The reaction between citric acid and iron nitrate was completed in 8 m long Teflon tubing for a duration of 5 min. The dark brown Fe3O4 precipitates were collected in a beaker, washed, spun in a centrifuge, and then freeze-dried.

2.1.3 Synthesis of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposite

Using the CMFS technique as previously described, a variety of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites were created. The HA and Fe3O4 samples were run through the CMFS system to produce the nanocomposite materials. An 8 m Teflon tube was twisted inside a standard microwave oven with the original mixture attached, and the reaction took 5 min to complete. The resultant light brown precipitates were centrifuged and freeze-dried according to the procedure discussed in Sections 2.1.1 and 2.1.2 and as shown in Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for the preparation of HA-Fe3O4.

2.2 Characterization techniques

2.2.1 Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD)

All samples underwent XRD analysis using a Bruker-X-ray diffractometer. Cu-K radiations (λ = 1.5406 Å) were used to evaluate the data in the 2θ range from 10° to 70° with a scanning step of 0.05° and a count duration of 2 s. Phase analysis of the data was performed using DIFFRACplus Eva software by spectral matching with benchmark patterns. The Debye-Sherrer equation was used to compute the sizes of the crystallites.

2.2.2 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

An electron microscope made by JEOL, 100 CX was used for the TEM investigation. Dispersing a little quantity of material in methanol and ultrasonically processing it for 2 min produced a highly diluted suspension. The next step was to put a little amount of the suspension onto a carbon-coated copper grid (purchased from Agar Scientific), which served as the TEM specimen. Prior to using the grid in the TEM’s double tilt holder, it was dried. Software for estimating particle size was installed, and it is version 5.0 of Image J.

2.2.3 Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area analysis

All samples’ BET surface area (N2 adsorption) measurements were made using a multipoint BET surface area analyzer. After being cleaned with methanol, the sample tubes were dried for a whole night at 100°C in the oven. Prior to BET analysis, the dried particles were precisely weighed and degassed at 180°C for 12 h. They were weighed again after degassing, followed by an analysis. Nitrogen physisorption at 196°C was used to estimate the BET surface area.

2.2.4 Zeta potential measurement

For the determination of the stability and surface charge of the fabricated magnetite nanocomposites, the Zeta potentials were calculated using the Anton Paar Particle Size Analyzer (Litesizer 500).

2.2.5 X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) chemical composition

Thermo Scientific’s XPS analyzer was used to conduct the chemical analysis. At the source, the X-rays were microfocused to produce spots on the sample that ranged in size from 30 to 400 microns. The vacuum chamber pressure was around 3 × 10−8 Torr, and the detector had 128 channel locations, making it a very sensitive device. For survey scans, the spectrum required 150 eV of energy, and for high-resolution regions, 50 eV. The CASATM program was used to process the XPS spectra.

2.2.6 Magnetic properties

The magnetization loops for magnetic nanocomposites were measured at 300 K using a vibrating sample VSM magnetometer. The powder samples above 10 mg were taken in sample holders for analysis. The heat changes in the HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites were also measured using an alternating magnetic field of 600 kHz and 3.2 kA/m.

2.2.7 Antimicrobial assay

The antimicrobial potential of magnetite hydroxyapatite nanoparticles was examined using agar well diffusion technique [28,45]. Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), a Gram-negative bacterium, was one of the four strains chosen for antibacterial screening, along with the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Micrococcus luteus (ATCC 49732), and Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii (ATCC 6633). Reference antibiotic standards were used as a positive control [Ciprofloxacin (10 µg/mL) and Vancomycin (10 µg/mL)], while the negative control was HA. In 1 L of DI water, 28 g nutrient agar was suspended, mixed thoroughly by heating, followed by intermittent stirring, and then completely dissolved by boiling for 1 min. In an autoclave, sterilization was conducted for 15 min at 121°C and 15 psi. Sabouraud dextrose agar plates were used for screening of antifungal properties against S. cerevisiae (ATCC 9763). All samples were having a concentration of 150 µg/mL, the samples were weighed using a microanalytical balance. The sterilized agar suspension was poured into Petri plates, settled, and then incubated for 24 h. Each test bacteria’s freshly prepared inoculum suspension was evenly distributed over the surface of the petri plates containing agar suspension. 50 µL of HA, 10HA-Fe3O4, 20HA-Fe3O4, and 30HA-Fe3O4 was placed into the each labelled well. The zones of inhibition were measured using a calibrated Vernier caliper after the samples and reference antibiotic standards were incubated at 37°C for 24 h (n = 3).

3 Results and discussion

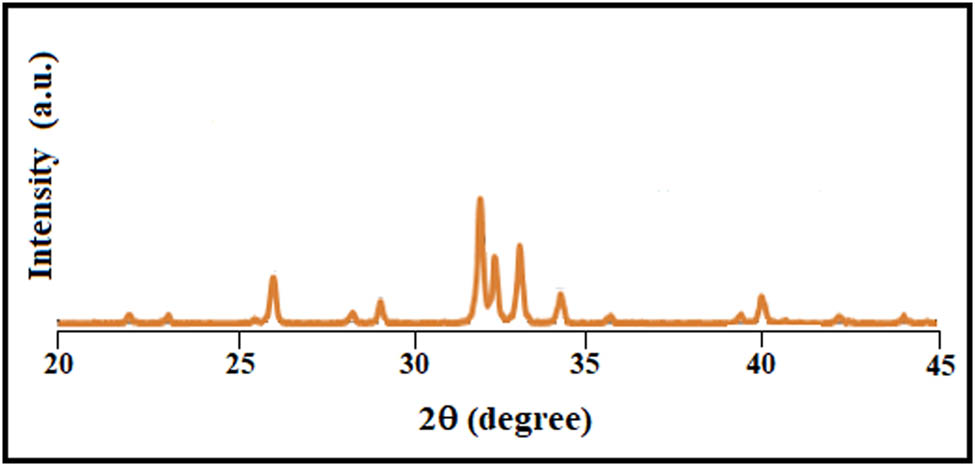

In order to investigate the phase purity of pure HA sample, Powder XRD analysis was carried out. There were no extra beta TCP peaks seen in the HA XRD patterns represented in Figure 2, which have an excellent match to JCPDS pattern 09-432 [46,47,48].

XRD analysis of pure HA synthesized using CMFS.

The phase purity and crystallinity of magnetite samples were also assessed from XRD measurements and were confirmed to be crystalline in nature. The XRD patterns of phase pure magnetite NPs are exhibited in Figure 2. No further diffraction peaks for other forms of iron oxide, such as α-Fe2O3 and ϒ-Fe2O3, were seen. Thus, the results revealed that the obtained nanoparticles are pure Fe3O4.

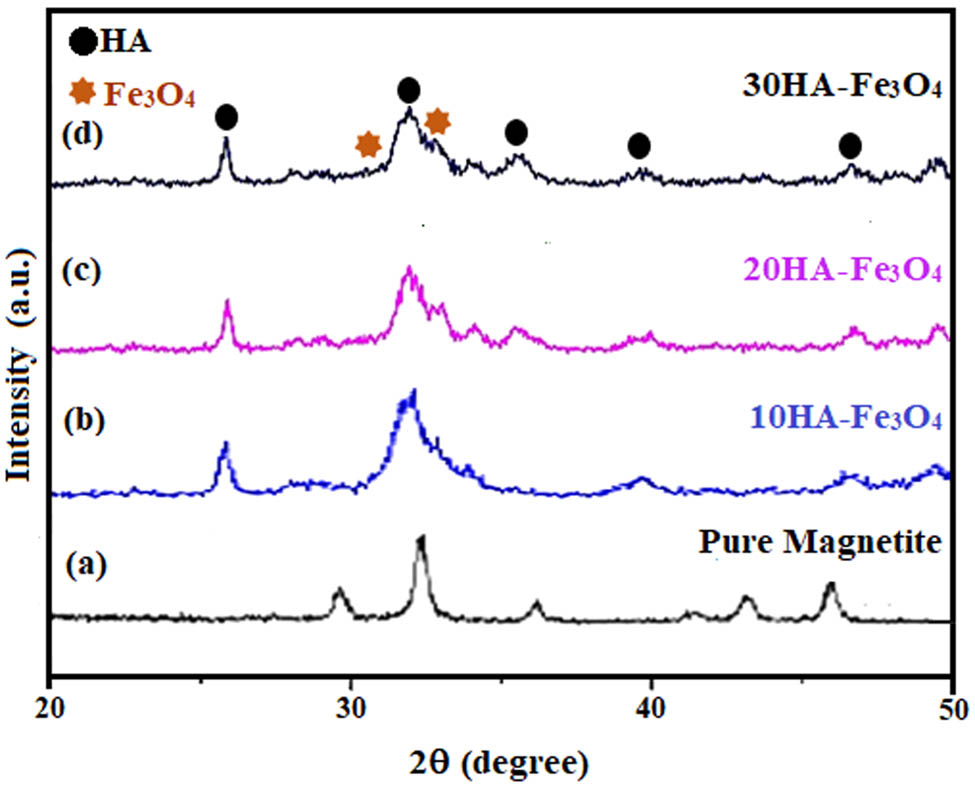

The HA-Fe3O4 nanopowder’s XRD pattern exhibited strong agreement with stoichiometric hydroxyapatite (JCPDS 09-0432 card), with a little displacement of the angles that were presumably caused by an increase in magnetite concentration. As illustrated in Figure 3, the peaks at 35.43° and 43.05° correspond to magnetite in 10, 20, and 30 wt% HA-Fe3O4 confirmed by previous literature [29,40]. The crystallite sizes calculated using the Debye-Sherrer formula were found to be 58, 47, and 42 nm for 10HA-Fe3O4, 20HA-Fe3O4, and 10HA-Fe3O4, respectively. The properties of nanocomposites exhibit a correlation with XRD-analyzed characteristics such as crystallinity, phase identification, magnetite content, and crystallite size [49]. When the crystallite size is small as in case of 30HA-Fe3O4, an enhanced antimicrobial activity and heat generation are measured.

XRD pattern of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites: (a) Pure magnetite, (b) 10HA-Fe3O4, (c) 20HA-Fe3O4, and (d) 30HA-Fe3O4, prepared at pH 11 in 5 min in CMFS.

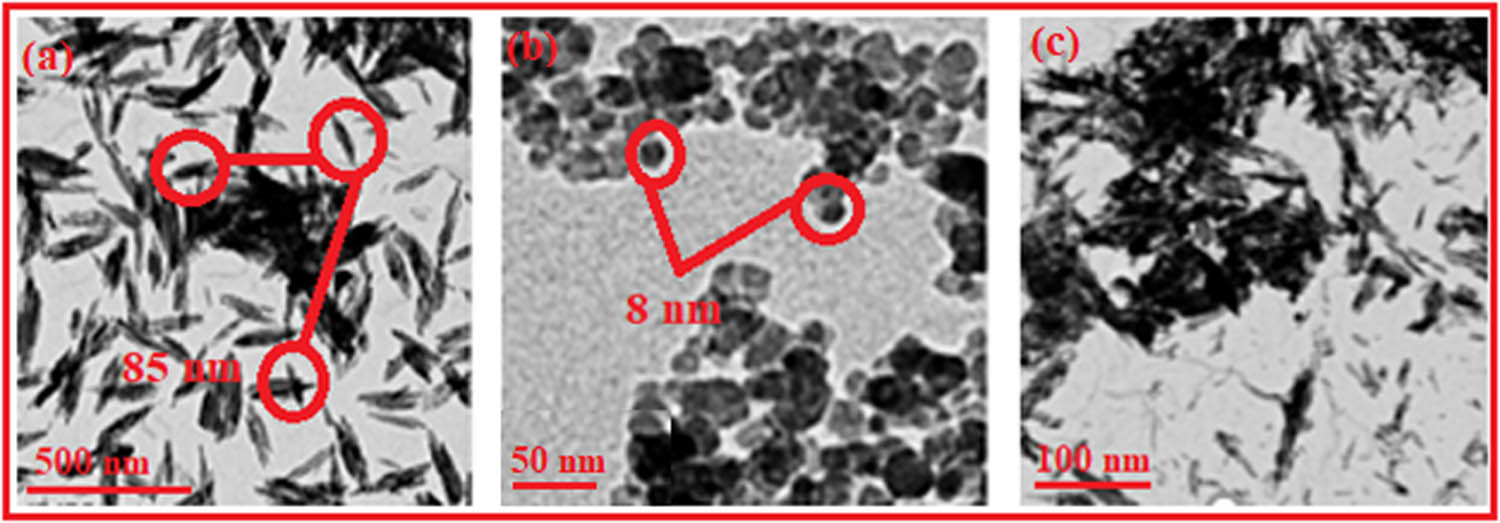

The images of the samples taken under a transmission electron microscope, as seen in Figure 4, provided proof that tiny crystallites had been produced. Pure HA sample generated in 5 minutes of residence time by CMFS showed a mean particle size of 85 ± 15 nm (Figure 4a). The magnetite nanoparticles as prepared in pure phase had a spherical morphology with a mean particle size of 8 ± 1.8 nm observed by these nanoparticles. The total particle count was found to be 250 with a moderate agglomeration as depicted in Figure 4b. In nanocomposites of Fe3O4-HA, spherical magnetite structures had been observed on the surface of HA rods as shown in Figure 4c with a size of 41 ± 2 nm. The crystallite sizes calculated from XRD data using the Debye-Sherrer formula and from TEM images were almost in accordance with each other. The previously reported size of spherical magnetite nanoparticles and magnetite hydroxyapatite is 75.34 ± 5.56 nm, and 95.16 ± 14.92 nm, respectively [8]. TEM analysis offers insights into particle size distribution, impacting properties such as drug release rates or magnetic responsiveness [50]. TEM analysis of nanocomposites indicates a direct link between their characteristics and hyperthermia as well as antimicrobial efficacy. The size and shape of these nanocomposites significantly impact their heating efficiency when subjected to magnetic fields [51]. Typically, smaller and uniformly shaped particles exhibit a higher capacity to generate heat, 30HA-Fe3O4 are in complete agreement to this statement. Conversely, the structural features of these nanocomposites enhance the bacterial adhesion which leads to membrane disruption [52].

TEM images of (a) pure HA, (b) pure magnetite, and (c) HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites.

The BET surface area analysis was also performed for “as precipitated” amorphous HA-Fe3O4 samples prepared in 5 min of residence time. It was observed that the HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposite had a surface area of 122.4, 139.5, and 156.3 m2 g−1 for the samples 10, 20, and 30 wt% respectively as represented in Table 1. It could be concluded that with the increase in the concentration of magnetite, the surface area of HA-Fe3O4 increases [53]. The BET surface area analysis comprehends the interaction of nanocomposites with the surrounding molecules or cells. In biomedical applications, a larger surface area typically denotes enhanced cell adhesion or better drug loading capability [54].

BET, TEM, zeta potential, and magnetization values of HA-Fe3O4

| Sample ID | XRD crystallite (nm) | BET (m2 g−1) | TEM (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | Magnetization (emu/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10HA-Fe3O4 | 58 | 122.4 | 56 | −18.9 | — |

| 20HA-Fe3O4 | 47 | 139.5 | 49 | −21.9 | – |

| 30HA-Fe3O4 | 42 | 156.3 | 41 | −24.6 | 59 |

Zeta potential, which reveals the electrostatic potential of the particles and is directly correlated with the stability of their dispersion through electrostatic repulsion, is a parameter to measure colloidal stability.

Higher zeta potential levels correspond to higher colloidal stability of the suspension resulting from increased electrostatic repulsion. Zeta potential measurements for HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposite at 10, 20, and 30 wt% revealed strong negative surface charges with values of −18.9, −21.9, and −24.6 mV, respectively, confirmed by previous literature [55]. A more stable dispersion has resulted from the higher value of zeta potential indicating a higher surface charge, which inhibits the aggregation of the particles. When evaluating the biological interactions and therapeutic efficacy of nanocomposites, surface charge plays a pivotal role. Positively charged nanocomposites are drawn towards the negatively charged cell membrane via electrostatic forces, facilitating rapid cellular uptake. Conversely, negatively charged nanocomposites might have an easier time targeting specific organs or receptors [56]. The accumulation of nanocomposites in particular tissues or organs can be influenced by their surface charge. For instance, negatively charged particles tend to target tumors more effectively, while positively charged ones often accumulate in the liver and spleen [57]. Surface charge also governs drug release from nanocomposites; pH-sensitive charges, for instance, enable controlled medication release, especially in environments like tumors [58].

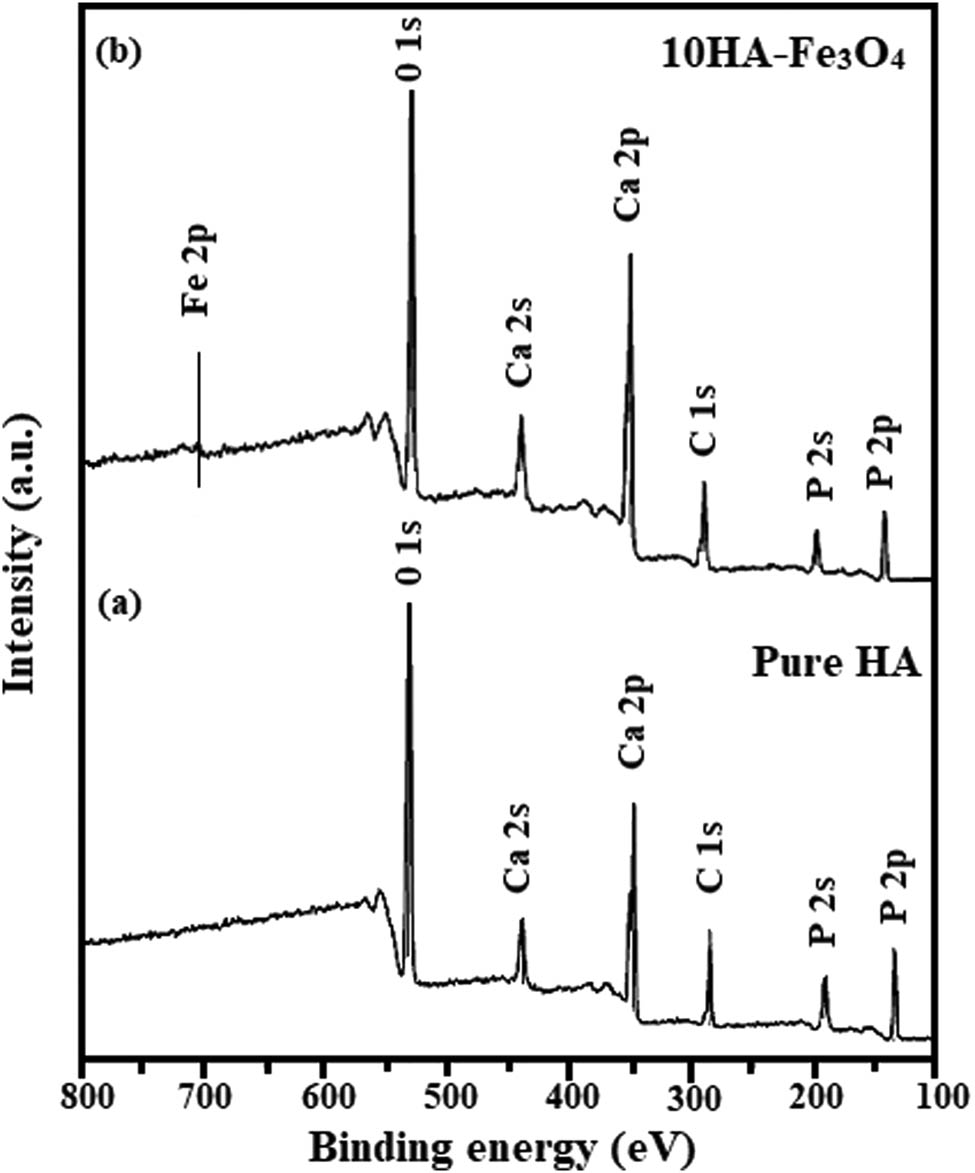

The investigation of the concentration of the magnetite, its oxidation state, and its impact on the architecture of the lattice was achieved by XPS experiments. Figure 5 displays a typical survey spectrum for pure HA and 10HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites. The P 2p peak of phosphate groups in HA were identified at 134 eV. O 1s, Ca 2p, and C 2s′ binding energies were calculated to be 533, 347, and 285 eV, individually. A smaller intensity at 710 eV corresponding to Fe 2p, which is missing in pure HA, was also reported previously [40,59]. As XPS provides important insights into the syrface chemistry and interfacial interactions of a nanocomposite by determining its elemental composition and chemical state, these findings profoundly influence interactions between biological fluids or other materials [60]. XPS does not directly correlate with hyperthermia or antimicrobial activity. However, the oxidation states of iron in magnetite can significantly impact its magnetic properties, which are essential for hyperthermia applications. Moreover, XPS has confirmed the presence of both HA and Fe3O4, and it is established that both components contribute to antimicrobial activity [52].

The XPS survey spectrum of (a) Pure HA and (b) 10HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposite.

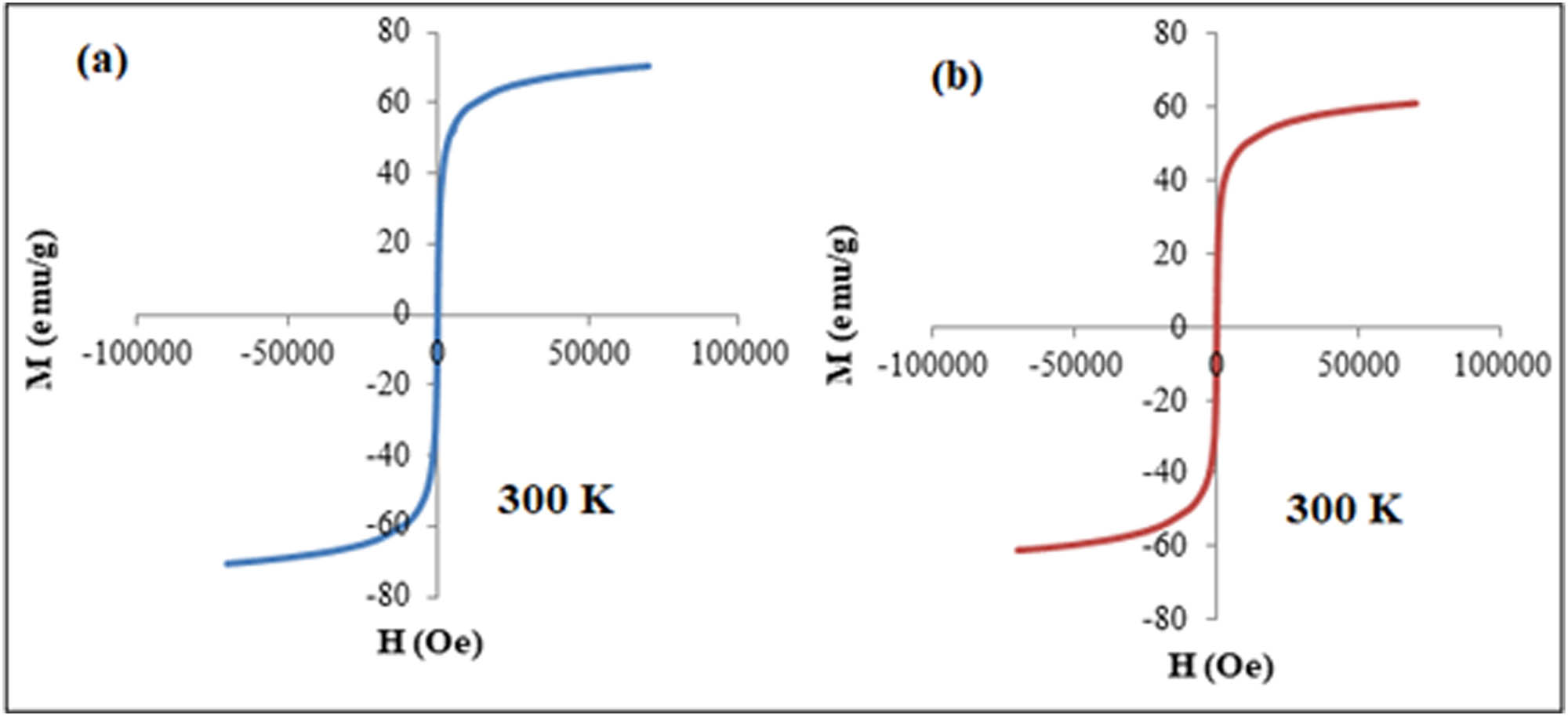

Figure 6a shows the hysteresis loops of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles observed at 300 K. Fe3O4 nanoparticle saturation magnetization values Ms at 300 K were found to be 70 emu/g, respectively. According to the findings, as shown in Figure 6b, the saturation magnetization value in 30HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites reduced to 59 emu/g from pure magnetite. HA-Fe3O4 is widely dispersed in the composite structure across the single pure phase and shows superparamagnetism, as is displayed from VSM measurements [61]. The reduction in Ms value has resulted from the diamagnetic behavior of HA while the superparamagnetic behavior of HA-Fe3O4 is due to the lack of a hysteresis loop [62,63,64].

The saturation magnetization values Ms of (a) pure Fe3O4 nanoparticles and (b) 30HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites, respectively, at 300 K.

Superparamagnetic magnetite nanoparticles have the ability to produce magnetism once placed in a magnetic field. This ability of heat generation at a specific temperature of about 43°C can be used to destroy cancer cells [65,66]. It was observed that the 10 and 20HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites were unable to produce enough heat for anticancer therapy. However, the magnetic apatite composites with 30 wt% magnetite concentrations exhibited a temperature of 51°C in 10 min, which is sufficient enough to destroy cancer cells during hyperthermia therapy for bone cancer. It can be inferred that increasing the concentration of magnetite in HA-Fe3O4, a significant increase in temperature can be achieved. Therefore, a synergistic behavior significantly dependent on concentration and particle size can be observed between HA and magnetite. Thus, the newly developed, highly magnetic magnetite incorporated HA nanocomposites can be used as an efficient tool for various cancer therapies and in addition for bone regeneration applications due to the strong bone-bonding ability of HA. High magnetization is a significant factor for the effective operation of MNPs across various applications, including magnetic hyperthermia. Enhanced magnetization heightens MNPs’ susceptibility to magnetic forces, enabling precise manipulation in both technical and biological contexts. This attribute empowers MNPs to respond markedly to external magnetic fields, a pivotal aspect in their functionality. This elevated magnetization ensures that MNPs efficiently convert applied magnetic field energy into heat during hyperthermia therapy. As a result, targeted tissues experience a rise in temperature, enabling therapeutic effects [67,68].

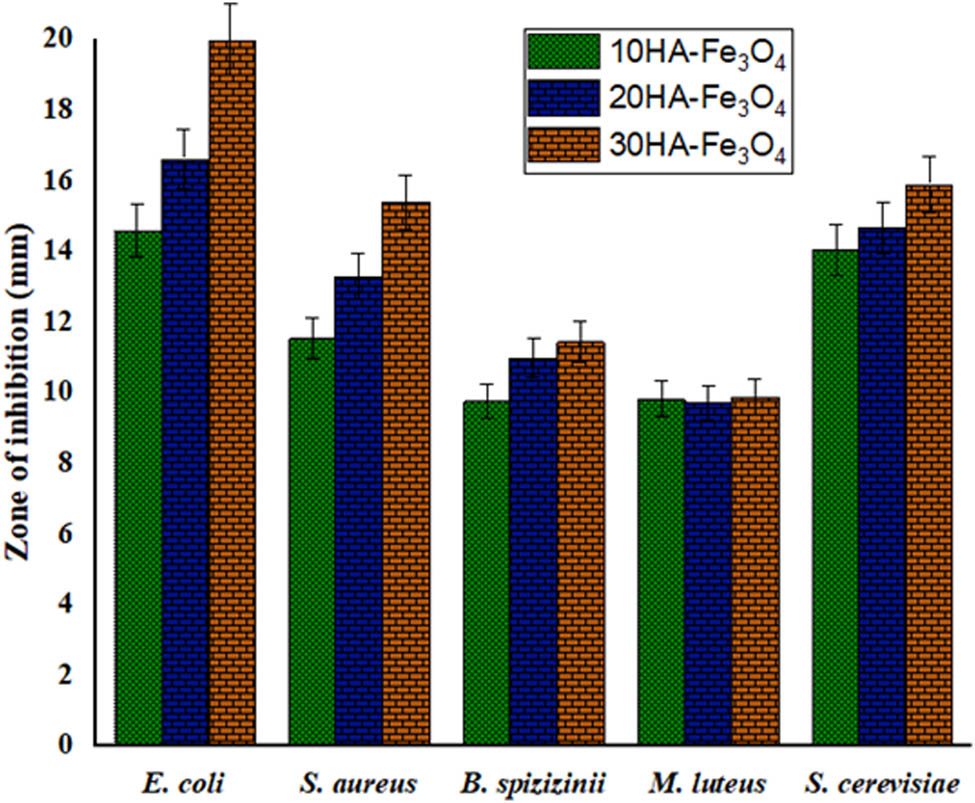

Four bacterial and one fungal strain were used in the evaluation of the antimicrobial characteristics of the pure HA, Fe3O4, 10HA-Fe3O4, 20HA-Fe3O4, and 30HA-Fe3O4. The results were highly encouraging. These are the typical prokaryotic microorganisms that have been linked to a variety of illnesses in both humans and animals. The results in Table 2 suggest that the synthesized nanocomposites were more effective against gram-negative bacteria than gram-positive bacteria. 30HA-Fe3O4 demonstrated the highest efficacy against E. coli (20.000 ± 0.25 mm) and S. cerevisiae exceeding the bacterial inhibition capacity of the widely used antibiotics ciprofloxacin and vancomycin.

Antibacterial assay of pure HA and varied concentrations of Fe3O4-HA

| Bactria/Fungi | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | Vancomycin | Fe3O4 | 10HA-Fe3O4 | 20HA-Fe3O4 | 30HA-Fe3O4 | |

| E. coli | 17.417 ± 0.04 | 17.817 ± 0.21 | 11.613 ± 0.21 | 14.613 ± 0.29 | 16.630 ± 0.32 | 20.000 ± 0.25 |

| S. aureus | 15.623 ± 0.06 | 17.130 ± 0.08 | 7.537 ± 0.25 | 11.537 ± 0.24 | 13.303 ± 0.77 | 15.410 ± 0.76 |

| B. spizizenii | 15.637 ± 0.10 | 16.430 ± 0.52 | 8.763 ± 0.33 | 9.763 ± 0.39 | 10.990 ± 0.69 | 11.453 ± 0.95 |

| M. luteus | 18.423 ± 0.37 | 19.427 ± 0.06 | 8.833 ± 0.26 | 9.833 ± 0.33 | 9.730 ± 0.32 | 9.887 ± 0.39 |

| S. cerevisiae | 11.380 ± 0.06 | 10.083 ± 0.24 | 10.050 ± 0.56 | 14.050 ± 0.66 | 14.667 ± 1.04 | 15.913 ± 0.40 |

From the data in Table 2 it could be assumed that as the concentration of Fe3O4-HA nanocomposite increases, E. coli and S. aureus cells gradually lose their integrity [55]. A comparative antimicrobial assay of HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites is illustrated in Figure 7, the calculated values are considerably closer to the real values (p < 0.05) after applying a hypothetical t-test using OriginPro software. According to the literature, the release of OH− ions in an aqueous environment is linked to HA’s antimicrobial action. Due to their high oxidizing ability, they react with a wide range of biomolecules. These free radicals hardly diffuse away from the sites of generation due to their strong and indiscriminate reactivity [5]. In the presence of Fe3O4-HA, the cell structure of bacteria is affected, the increase in the concentration of HA-Fe3O4 increases the rate of cell membrane damage as more nanocomposites come in contact with the bacterial cell [69]. Some proposed mechanisms suggest that due to the generation of reactive oxidative species (ROS), the nanoparticles diffuse into bacterial cells and obstruct their metabolic processes. They can also interact directly with bacterial DNA or thiol groups in proteins to halt all functions and cause cell death, or they can react with the cell wall and membrane of the bacterial cell to create holes through which the cellular contents leak out [45,53,70,71]. All concentrations of Fe3O4-HA have depicted strong activity against S. cerevisiae. As the saturation of the solution rises, the fungus becomes dormant and loses its ability to cling to fungal hyphae owing to high density. By rupturing cell walls and membranes, impeding mycelial development and conidial germination, and producing ROS, the nanoparticles prevent the growth of fungus [72].

Antimicrobial activity of various concentrations of HA-Fe3O4.

Precise optimization of synthesis parameters (flow rate, microwave power, temperature) was achieved after a series of reactions with careful observations. The optimization was significant in acquiring desired nanocomposite properties within a short residence time [73,74]. Microwaves penetrate the reaction mixture, leading to volumetric heating and accelerating reaction kinetics. This enables faster synthesis compared to conventional methods. Continuous flow ensures efficient mixing and transport of reactants, promoting rapid nucleation and growth of nanoparticles. Short residence time allows for fine-tuning of particle size, shape, and composition by adjusting flow rate and microwave power [75]. Shorter synthesis time reduces energy consumption. Shorter residence time results in smaller, more uniform nanoparticles beneficial for certain applications, such as drug delivery, where smaller particles can enhance bioavailability. It also ensures the preservation of magnetite’s magnetic properties, essential for applications such as magnetic separation or hyperthermia. Extremely good results were obtained using the unique CMFS method, this work provided the fastest method for producing extremely thin nanorods of pure and Fe3O4 substituted bioactive nanobioceramics with a large surface area in a relatively short period of time. The synthesis method and increasing concentration of Fe3O4 has greatly improved the hyperthermal properties of the magnetic HA-Fe3O4.

4 Conclusion

Magnetic HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites were successfully fabricated with varied percentage compositions in only 5 min of residence time without any stirring and aging using continuous microwave flow synthesis. 30HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites have shown very promising results with high surface area 156.3 m2 g−1, small particle size (41 nm), and negative surface charge (−24.6 mV). The superparamagnetic MNPs have a heat generation of 51°C within 10 min after placing in magnetic field; therefore, they can be employed as an efficient tool for various cancer therapies. Remarkable antimicrobial properties have been revealed by HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites. As a result of better magnetic properties and high magnetization values, they can improve the sintering kinetics. Hence, HA-Fe3O4 composites produced through our synthesis approach can effectively treat malignant bone tumors with heat. Ample effort would be put into creating HA-Fe3O4 nanocomposites having large surface area with tunable mechanical and magnetic properties for bone tissue regeneration, fabrication of highly sensitive and specific biosensors for early disease diagnosis and in vivo studies for utilization in the future.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1C1C1008831). This study has been conducted with the support of the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology as “Development of intelligent root technology with add-on modules (KITECH EO-23-0005).” This research was supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE) of Korea through the “Innovative Digital Manufacturing Platform” (project no. P0022331) supervised by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT). The work was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R663), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Al-Mutairi NH, Mehdi AH, Kadhim BJ. Nanocomposites materials definitions, types and some of their applications: A review. Eur J Res Dev Sustain. 2022;3(2):102–8.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Okpala CC. The benefits and applications of nanocomposites. Int J Adv Eng Tech. 2014;12:18.Search in Google Scholar

[3] AbuShanab WS, Moustafa EB, Taha MA, Youness RA. Synthesis and structural properties characterization of titania/zirconia/calcium silicate nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Appl Phys A. 2020;126:1–12.10.1007/s00339-020-03975-8Search in Google Scholar

[4] Mosaiab T, Jeong CJ, Shin GJ, Choi KH, Lee SK, Lee I, et al. Recyclable and stable silver deposited magnetic nanoparticles with poly (vinyl pyrrolidone)-catechol coated iron oxide for antimicrobial activity. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33(7):3786–94.10.1016/j.msec.2013.05.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Rad Goudarzi M, Bagherzadeh M, Fazilati M, Riahi F, Salavati H, Shahrokh Esfahani S. Evaluation of antibacterial property of hydroxyapatite and zirconium oxide-modificated magnetic nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. IET Nanobiotechnolog. 2019;13(4):449–55.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Bretcanu O, Miola M, Bianchi CL, Marangi I, Carbone R, Corazzari I, et al. In vitro biocompatibility of a ferrimagnetic glass-ceramic for hyperthermia application. Mater Sci Eng C. 2017;73:778–87.10.1016/j.msec.2016.12.105Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Miola M, Pakzad Y, Banijamali S, Kargozar S, Vitale-Brovarone C, Yazdanpanah A, et al. Glass-ceramics for cancer treatment: so close, or yet so far? Acta Biomater. 2019;83:55–70.10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Mondal S, Manivasagan P, Bharathiraja S, Santha Moorthy M, Kim HH, Seo H, et al. Magnetic hydroxyapatite: A promising multifunctional platform for nanomedicine application. Int J Nanomed. 2017;8389–410.10.2147/IJN.S147355Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Mushtaq A, Zhao R, Luo D, Dempsey E, Wang X, Iqbal MZ, et al. Magnetic hydroxyapatite nanocomposites: The advances from synthesis to biomedical applications. Mater Des. 2021;197:109269.10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109269Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kumar A, Vashist H, Sharma R, Garg D. An anthology of cancer. IIJMPS. 2018;3(4):7–14.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Baskar R, Lee KA, Yeo R, Yeoh K-W. Cancer and radiation therapy: Current advances and future directions. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(3):193.10.7150/ijms.3635Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Mahmoodzadeh F, Hosseinzadeh M, Jannat B, Ghorbani M. Fabrication and characterization of gold nanospheres-cored pH-sensitive thiol-ended triblock copolymer: A smart drug delivery system for cancer therapy. Polym Adv Technol. 2019;30(6):1344–55.10.1002/pat.4567Search in Google Scholar

[13] Danewalia S, Singh K. Bioactive glasses and glass–ceramics for hyperthermia treatment of cancer: State-of-art, challenges, and future perspectives. Mater Today Bio. 2021;10:100100.10.1016/j.mtbio.2021.100100Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Sneha M, Sundaram NM, Kandaswamy A. Synthesis and characterization of magnetite/hydroxyapatite tubes using natural template for biomedical applications. Bull Mater Sci. 2016;39:509–17.10.1007/s12034-016-1165-3Search in Google Scholar

[15] Baronzio G, Parmar G, Ballerini M, Szasz A, Baronzio M, Cassutti V. A brief overview of hyperthermia in cancer treatment. J Integr Oncol. 2014;3(115):2.10.4172/2329-6771.1000115Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yu S, He C, Chen X. Injectable hydrogels as unique platforms for local chemotherapeutics-based combination antitumor therapy. Macromol Biosci. 2018;18(12):1800240.10.1002/mabi.201870030Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mondal S, Manivasagan P, Bharathiraja S, Santha Moorthy M, Nguyen VT, Kim HH, et al. Hydroxyapatite coated iron oxide nanoparticles: A promising nanomaterial for magnetic hyperthermia cancer treatment. Nanomaterials. 2017;7(12):426.10.3390/nano7120426Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Seynhaeve A, Amin M, Haemmerich D, Van Rhoon G, Ten Hagen T. Hyperthermia and smart drug delivery systems for solid tumor therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;163:125–44.10.1016/j.addr.2020.02.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Aslibeiki B, Eskandarzadeh N, Jalili H, Varzaneh AG, Kameli P, Orue I, et al. Magnetic hyperthermia properties of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Effect of polymer coating and interparticle interactions. Ceram Int. 2022;48(19):27995–8005.10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.06.104Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wust P, Hildebrandt B, Sreenivasa G, Rau B, Gellermann J, Riess H, et al. Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(8):487–97.10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00818-5Search in Google Scholar

[21] Di Corato R, Espinosa A, Lartigue L, Tharaud M, Chat S, Pellegrino T, et al. Magnetic hyperthermia efficiency in the cellular environment for different nanoparticle designs. Biomaterials. 2014;35(24):6400–11.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Cho M, Cervadoro A, Ramirez MR, Stigliano C, Brazdeikis A, Colvin VL, et al. Assembly of iron oxide nanocubes for enhanced cancer hyperthermia and magnetic resonance imaging. Nanomaterials. 2017;7(4):72.10.3390/nano7040072Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Dahaghin A, Emadiyanrazavi S, Haghpanahi M, Salimibani M, Bahreinizad H, Eivazzadeh-Keihan R, et al. A comparative study on the effects of increase in injection sites on the magnetic nanoparticles hyperthermia. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2021;63:102542.10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102542Search in Google Scholar

[24] Miola M, Gerbaldo R, Laviano F, Bruno M, Vernè E. Multifunctional ferrimagnetic glass–ceramic for the treatment of bone tumor and associated complications. J Mater Sci. 2017;52:9192–201.10.1007/s10853-017-1078-6Search in Google Scholar

[25] Baino F, Fiume E, Miola M, Leone F, Onida B, Laviano F, et al. Fe-doped sol-gel glasses and glass-ceramics for magnetic hyperthermia. Materials. 2018;11(1):173.10.3390/ma11010173Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Wang M-C, Chen H-T, Shih W-J, Chang H-F, Hon M-H, Hung I-M. Crystalline size, microstructure and biocompatibility of hydroxyapatite nanopowders by hydrolysis of calcium hydrogen phosphate dehydrate (DCPD). Ceram Int. 2015;41(2):2999–3008.10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.10.135Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kamonwannasit S, Futalan C, Khemthong P, Butburee T, Karaphun A, Phatai P. Synthesis of copper-silver doped hydroxyapatite via ultrasonic coupled sol-gel techniques: structural and antibacterial studies. JSST. 2020;96:452–63.10.1007/s10971-020-05407-8Search in Google Scholar

[28] Anwar A, Akbar S, Sadiqa A, Kazmi M. Novel continuous flow synthesis, characterization and antibacterial studies of nanoscale zinc substituted hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Inorg Chim Acta. 2016;453:16–22.10.1016/j.ica.2016.07.041Search in Google Scholar

[29] Iwasaki T, Nakatsuka R, Murase K, Takata H, Nakamura H, Watano S. Simple and rapid synthesis of magnetite/hydroxyapatite composites for hyperthermia treatments via a mechanochemical route. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(5):9365–78.10.3390/ijms14059365Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Ebadi M, Rifqi Md Zain A, Tengku Abdul Aziz TH, Mohammadi H, Tee CAT, Rahimi Yusop M. Formulation and characterization of Fe3O4@ PEG nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; molecular studies and evaluation of cytotoxicity in liver cancer cell lines. Polymers. 2023;15(4):971.10.3390/polym15040971Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Ereath Beeran A, Fernandez FB, Varma PH. Self-controlled hyperthermia & MRI contrast enhancement via iron oxide embedded hydroxyapatite superparamagnetic particles for theranostic application. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;5(1):106–13.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00244Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Palzer J, Eckstein L, Slabu I, Reisen O, Neumann UP, Roeth AA. Iron oxide nanoparticle-based hyperthermia as a treatment option in various gastrointestinal malignancies. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(11):3013.10.3390/nano11113013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Bañobre-López M, Piñeiro-Redondo Y, De Santis R, Gloria A, Ambrosio L, Tampieri A, et al. Poly (caprolactone) based magnetic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Appl Phys. 2011;109(7):07B313.10.1063/1.3561149Search in Google Scholar

[34] Tampieri A, D’Alessandro T, Sandri M, Sprio S, Landi E, Bertinetti L, et al. Intrinsic magnetism and hyperthermia in bioactive Fe-doped hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(2):843–51.10.1016/j.actbio.2011.09.032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Gloria A, Russo T, d’Amora U, Zeppetelli S, d’Alessandro T, Sandri M, et al. Magnetic poly (ε-caprolactone)/iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanocomposite substrates for advanced bone tissue engineering. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10(80):20120833.10.1098/rsif.2012.0833Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Choi J-W, Lee H-K, Choi S-J. Magnetite double-network composite using hydroxyapatite-manganese dioxide for Sr2+ removal from aqueous solutions. J Env Chem Eng. 2021;9(4):105360.10.1016/j.jece.2021.105360Search in Google Scholar

[37] Li R, Liu Y, Lan G, Qiu H, Xu B, Xu Q, et al. Pb (II) adsorption characteristics of magnetic GO-hydroxyapatite and the contribution of GO to enhance its acid resistance. J Env Chem Eng. 2021;9(4):105310.10.1016/j.jece.2021.105310Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hui KC, Kamal NA, Sambudi NS, Bilad MR, editors. Magnetic hydroxyapatite for batch adsorption of heavy metals. E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences; 2021.10.1051/e3sconf/202128704005Search in Google Scholar

[39] Elkady M, Shokry H, Hamad H. Microwave-assisted synthesis of magnetic hydroxyapatite for removal of heavy metals from groundwater. Chem Eng Technol. 2018;41(3):553–62.10.1002/ceat.201600631Search in Google Scholar

[40] Biedrzycka A, Skwarek E, Hanna UM. Hydroxyapatite with magnetic core: Synthesis methods, properties, adsorption and medical applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;291:102401.10.1016/j.cis.2021.102401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Nabizad M, Dadvand Koohi A, Erfanipour Z. Removal of cefixime using heterogeneous fenton catalysts: Alginate/magnetite hydroxyapatite nanocomposite. JWENT. 2022;7(1):14–30.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Tran N, Mir A, Mallik D, Sinha A, Nayar S, Webster T. Bactericidal effect of iron oxide nanoparticles on Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Nanomed. 2010;5:277–83.10.2147/IJN.S9220Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] MehakThummer RP, Pandey LM. Surface modified iron-oxide based engineered nanomaterials for hyperthermia therapy of cancer cells. BGER. 2023;1–47.10.1080/02648725.2023.2169370Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Leonel AG, Mansur HS, Mansur AA, Caires A, Carvalho SM, Krambrock K, et al. Synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles/carboxymethyl cellulose core-shell nanohybrids for killing cancer cells in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;132:677–91.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Sadiqa A, Gilani SR, Anwar A, Mehboob A, Saleem A, Rubab S. Biogenic fabrication, characterization and drug loaded antimicrobial assay of silver nanoparticles using Centratherum anthalminticum (L.) Kuntze. J Pharm Sci. 2021;110(5):1969–78.10.1016/j.xphs.2021.01.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Kusuma H, Sifah L, Anggita S, editors. The characterization of hydroxyapatite from blood clam shells and eggs shells: Synthesis by hydrothermal method. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2021. IOP Publishing.10.1088/1742-6596/1918/2/022040Search in Google Scholar

[47] El Boujaady H, Mourabet M, El Rhilassi A, Bennani-Ziatni M, El Hamri R, Taitai A. Adsorption of a textile dye on synthesized calcium deficient hydroxyapatite (CDHAp): Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J Mater Environ Sci. 2016;7(11):4049–63.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Anwar A, Kanwal Q, Akbar S, Munawar A, Durrani A, Hassan Farooq M. Synthesis and characterization of pure and nanosized hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Nanotechnol Rev. 2017;6(2):149–57.10.1515/ntrev-2016-0020Search in Google Scholar

[49] de Jesús Ruíz-Baltazar Á, Reyes-López SY, Silva-Holguin PN, Larrañaga D, Estévez M, Pérez R. Novel biosynthesis of Ag-hydroxyapatite: Structural and spectroscopic characterization. Results Phys. 2018;9:593–7.10.1016/j.rinp.2018.03.016Search in Google Scholar

[50] Mathaes R, Winter G, Siahaan TJ, Besheer A, Engert J. Influence of particle size, an elongated particle geometry, and adjuvants on dendritic cell activation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;94:542–9.10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.06.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Ali I, Jamil Y, Khan SA, Pan Y, Shah AA, Chandio AD, et al. Magnetic hyperthermia and antibacterial response of CuCo2O4 nanoparticles synthesized through laser ablation of bulk alloy. Magnetochemistry. 2023;9(3):68.10.3390/magnetochemistry9030068Search in Google Scholar

[52] Rad Goudarzi M, Bagherzadeh M, Fazilati M, Riahi F, Salavati H, Shahrokh Esfahani S. Evaluation of antibacterial property of hydroxyapatite and zirconium oxide-modificated magnetic nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2019;13(4):449–55.10.1049/iet-nbt.2018.5029Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Bajpai I, Balani K, Basu B. Synergistic effect of static magnetic field and HA-Fe3O4 magnetic composites on viability of S. aureus and E. coli bacteria. J Biomed Mater Res - B Appl Biomater. 2014;102(3):524–32.10.1002/jbm.b.33031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Bhatt A, Sakai K, Madhyastha R, Murayama M, Madhyastha H, Rath SN. Biosynthesis and characterization of nano magnetic hydroxyapatite (nMHAp): An accelerated approach using simulated body fluid for biomedical applications. Ceram Int. 2020;46(17):27866–76.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.07.285Search in Google Scholar

[55] Sahoo JK, Konar M, Rath J, Kumar D, Sahoo H. Magnetic hydroxyapatite nanocomposite: Impact on Eriochrome black-T removal and antibacterial activity. J Mol Liq. 2019;294:111596.10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111596Search in Google Scholar

[56] Jo DH, Kim JH, Lee TG, Kim JH. Size, surface charge, and shape determine therapeutic effects of nanoparticles on brain and retinal diseases. Nanomedicine: NBM. 2015;11(7):1603–11.10.1016/j.nano.2015.04.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Chenthamara D, Subramaniam S, Ramakrishnan SG, Krishnaswamy S, Essa MM, Lin F-H, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles and routes of administration. Biomater Res. 2019;23(1):1–29.10.1186/s40824-019-0166-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Bamburowicz-Klimkowska M, Poplawska M, Grudzinski IP. Nanocomposites as biomolecules delivery agents in nanomedicine. J Nanobiotechnology. 2019;17:1–32.10.1186/s12951-019-0479-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Foroutan R, Peighambardoust SJ, Hemmati S, Ahmadi A, Falletta E, Ramavandi B, et al. Zn2+ removal from the aqueous environment using a polydopamine/hydroxyapatite/Fe3O4 magnetic composite under ultrasonic waves. RSC Adv. 2021;11(44):27309–21.10.1039/D1RA04583KSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Korin E, Froumin N, Cohen S. Surface analysis of nanocomplexes by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3(6):882–9.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Ebadi M, Bullo S, Buskara K, Hussein MZ, Fakurazi S, Pastorin G. Release of a liver anticancer drug, sorafenib from its PVA/LDH- and PEG/LDH-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–19.10.1038/s41598-020-76504-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Ali MAEAA, Hamad H. Synthesis and characterization of highly stable superparamagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles as a catalyst for novel synthesis of thiazolo [4, 5-b] quinolin-9-one derivatives in aqueous medium. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 2015;404:148–55.10.1016/j.molcata.2015.04.023Search in Google Scholar

[63] Boda SK, Thrivikraman G, Basu B. Magnetic field assisted stem cell differentiation–role of substrate magnetization in osteogenesis. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3(16):3150–68.10.1039/C5TB00118HSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Ganapathe LS, Mohamed MA, Mohamad Yunus R, Berhanuddin DD. Magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles in biomedical application: From synthesis to surface functionalisation. Magnetochemistry. 2020;6(4):68.10.3390/magnetochemistry6040068Search in Google Scholar

[65] Hilger I, Frühauf K, Andrä W, Hiergeist R, Hergt R, Kaiser WA. Heating potential of iron oxides for therapeutic purposes in interventional radiology. Acad Radiol. 2002;9(2):198–202.10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80171-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Jose J, Kumar R, Harilal S, Mathew GE, Parambi DGT, Prabhu A, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia in cancer treatment: an emerging tool. Env Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27:19214–25.10.1007/s11356-019-07231-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Vargas-Ortiz JR, Gonzalez C, Esquivel K. Magnetic iron nanoparticles: Synthesis, surface enhancements, and biological challenges. Processes. 2022;10(11):2282.10.3390/pr10112282Search in Google Scholar

[68] Ali A, Shah T, Ullah R, Zhou P, Guo M, Ovais M, et al. Review on recent progress in magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and diverse applications. Front Chem. 2021;9:629054.10.3389/fchem.2021.629054Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[69] Mirzakhanlou H, Khoshnevis Zadeh R, Zare Karizi S. Prepration of pipractam liposomal formulations and evaluation of antimicrobial effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Mol Res (Iran J Biol). 2022;35(4):527–41.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Tripathi D, Modi A, Narayan G, Rai SP. Green and cost effective synthesis of silver nanoparticles from endangered medicinal plant Withania coagulans and their potential biomedical properties. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;100:152–64.10.1016/j.msec.2019.02.113Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Medina-Ramirez I, Luo Z, Bashir S, Mernaugh R, Liu JL. Facile design and nanostructural evaluation of silver-modified titania used as disinfectant. Dalton Trans. 2011;40(5):1047–54.10.1039/C0DT00784FSearch in Google Scholar

[72] Kim SW, Jung JH, Lamsal K, Kim YS, Min JS, Lee YS. Antifungal effects of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) against various plant pathogenic fungi. Mycobiology. 2012;40(1):53–8.10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.1.053Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[73] Anwar A, Akbar S. Novel continuous microwave assisted flow synthesis of nanosized manganese substituted hydroxyapatite. Ceram Int. 2018;44(9):10878–82.10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.03.141Search in Google Scholar

[74] Anwar A, Akbar S, Kazmi M, Sadiqa A, Gilani SR. Novel synthesis and antimicrobial studies of nanoscale titania particles. Ceram Int. 2018;44(17):21170–5.10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.08.162Search in Google Scholar

[75] Anwar A, Akbar S. Continuous microwave assisted flow synthesis and characterization of calcium deficient hydroxyapatite nanorods. Adv Powder Technol. 2018;29(6):1493–8.10.1016/j.apt.2018.03.014Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface