Abstract

Why does people’s crime involvement vary and change? Developmental and Life-Course criminology has brought individual change to the forefront of criminological study and has done an impressive job of mapping out peoples age-graded patterns of crime involvement and demonstrated an abundance of individual and social factors correlated with various aspects of people’s criminal careers and their characteristics. However, DLC criminology has been less successful in comprehensively explaining the identified patterns and their correlates. In this paper I shall discuss some of DLC criminology’s theoretical shortcomings, specifically the limitations of the commonplace risk factor approach to explanation and the related idea of cumulative risk. I shall argue that criminal careers are best understood and analysed as a series of situationally caused crime events, putting the explanatory focus on the socially and age-graded stability and change in crime relevant situational factors, and, crucially, the developmental processes that drive continuity and change in these factors (the causes of the causes). All this is discussed based on Situational Action Theory (SAT) and its Developmental-Ecological-Action model (DEA model).

»life-course criminology would be enormously enriched by greater

attention to relevant ways that people and their lives change with age.«

Wayne Osgood[1]

Developmental and Life-Course criminology (DLC criminology) is one of the most prominent and important perspectives in the study of crime and its correlates. It has brought individual change to the forefront of criminological study and done an impressive job of mapping out how people’s crime involvement varies and changes by age and can be summarised as different pathways in crime and their characteristics. We have also learned a lot about the abundance of individual and social factors statistically associated with various aspects of crime involvement and its changes (see, e. g., Ahonen et al., 2020; Basto-Pereira & Farrington, 2019; Boers et al., 2010; Craig et al., 2020; Farrington, 2018; Farrington & Wikström, 1993; Jennings et al., 2016; LeBlanc & Frechette, 1989; Loeber & Farrington, 1998; Loeber et al., 2003; Loeber & Wikström, 1993; Lösel, 2003; Lösel & Bender, 2009; Moffitt, 2018; Nagin et al., 1995; Piquero et al., 2007; Sampson & Laub, 1995; Thornberry et al., 2003; Tremblay, 2015; Wikström, 1990; Wikström et al., 2024; Wolfgang, 1983; Wolfgang et al., 1972)[2].

However, while DLC criminology is empirically (descriptively) strong, I think it is fair to say that overall, it has been less successful in explaining identified criminal career patterns (especially when it comes to explaining what factors and processes drive stability and change in people’s crime involvement). Typically, but not exclusively, DLC criminology has applied a rather atheoretical public health inspired risk and protective factors perspective to its ›explanation‹ of people’s crime involvement and their criminal careers. Julien Morizot and Lila Kazemian (2015, p. 2) have summarised the central objectives of developmental criminology as follows: »[to] describe within-individual continuity and change in criminal and antisocial behavior over time [to] explain the parameters of its development (onset, activation and aggravation) and termination [to] identify etiological factors (risk and protective factors) associated with its different developmental parameters«.

In this paper I will highlight some of DLC criminology’s common theoretical shortcomings (see further, Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 5–18) and argue for the need to develop a more dynamic and theory-driven DLC criminology, focused on understanding how people and their environments develop and interact in shaping and forming individual crime trajectories and their characteristics. I will stress the importance of adopting an ecological perspective on people’s crime involvement and its changes (focusing on the role of the person-environment interaction), and that this is grounded in an adequate action theory (an explanation of what moves people to action). I will specifically outline how Situational Action Theory (SAT), and its DEA model, have approached these problems (e. g., Wikström, 2006; 2010; 2019a; 2019b; Wikström & Treiber, 2018; Wikström et al., 2012, pp. 3–43; Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 29–112).

1 The Problem of Correlational Criminology. The need to avoid the ›causation by association fallacy‹.

One of the biggest problems with risk-focused research is that it tends to assume that what characterises the people who commit crimes and the places where crimes occur are necessarily also factors implicated in the causation of crime.

DLC criminology has generally, but not exclusively[3], adopted a public health inspired risk and protective factor perspective coupled with a risk-focused prevention strategy that advocates the value of and need to reduce risk factors and increase protective factors[4] to reduce crime (e. g., Farrington et al., 2012). A risk factor is typically defined as a time-ordered statistically significant correlation, i. e., a predictor (e. g., Loeber, 1990). There are 100s of identified risk factors (Ellis et al., 2019). Often, they are rather weak correlations[5] (little explained variance), where it is only somewhat more common among those who have a certain characteristic that they commit more crimes than others, while most who have the characteristic in question do not (i. e., the within-group variance in crime involvement is large). Even some risk factors that are prominent in the causes of crime debate, such as neighbourhood and individual/family socioeconomic disadvantage, have consistently been shown in research to have only modest correlations with people’s involvement in crime (Wikström & Treiber, 2016).

Although it is likely that most risk factor researchers are aware of the problem of correlation and causation, it is still common that they generally talk about risk factors (predictors) in causative terms such as that they ›effect‹, ›influence‹ or ›change‹ the outcome. The concept of risk factor in the study of crime is in itself problematic, because the word ›risk‹ indicates some causal efficacy (i. e., an increased probability of offending). It is therefore not surprising that policymakers and practitioners tend to treat all the many suggested risk factors as causally effective factors. That is especially so, when common advice from risk factor research is that attacking risk factors will reduce crime. A clear understanding of what factors and processes are causally effective and important in crime causation helps policy and prevention to better focus their activities on those that really matter.

To advance DLC criminology (and criminology in general for that matter) there is a need to move away from an essentially correlational criminology to a more analytic approach – asking why and how (does it work) questions – to better focus on identifying the factors and processes that are directly or indirectly involved in making people to see and choose crime as an acceptable action alternative in the circumstance and what drives its age-related stability and change (Wikström & Kroneberg, 2022). In this context I would argue that empirical research has two major objectives: To describe phenomena of interest (e. g., crime events) and to test their proposed explanation (e. g., proposed explanations of crime events). Views such as ›let the data speak‹ is, in my opinion and experience, not very helpful and rarely lead us anywhere useful. Theory is what explains. That said, good descriptions of a phenomenon of interest (e. g., ›crime events‹ and ›criminal careers‹) may help us better focus on what could be its potential explanation (and help exclude some unlikely avenues of explanation).

2 The Problem with the idea of Cumulative Risk. An Illustration of the Importance of Asking Why and How (does it work) Questions.

The concept of cumulative risk, prevalent in DLC criminology, is a good illustration of an inherent problem with the risk factor approach to explanation. The idea of cumulative risk is the idea that the more risk factors people display, the greater the likelihood they will commit crimes (Loeber et al., 2006, p. 161). However, a cumulative risk is hardly a cumulative cause. Adding a number of disparate and unrelated factors to a (often modest) prediction of crime involvement does not provide much knowledge about what causes people to perceive and choose crime as an action alternative in certain circumstances. Consequently, it does not give any greater guidance to policy and practice about what to target in their crime prevention efforts.

The problem with the idea of cumulative risk is twofold: firstly, most individuals who have typical social risk factors[6] – even those who have a greater number of such risk factors – do not commit more crimes than others (i. e. it is typically more common but not common among those who have a high cumulative social risk that they commit more crimes than others), secondly, and centrally, it is often unclear why and how many of these factors in themselves would affect people’s participation in crime (i. e. they are theoretically unspecified). It is hardly the case that the fact that someone, for example, grew up with a single parent, have poor school grades or lives in a public housing neighbourhood (to name a few common ›risk factors‹) in itself would cause them to, e. g., shoplift, sexually assault another person, vandalize parked cars, embezzle funds, or shoot a member of a rival gang.

Many commonly studied risk factors (predictors) are at best markers (i. e. correlated with causal factors). The trick is to identify which few of the many risk factors have causal relevance and importance. This is certainly essential from a crime prevention policy and practise point of view because attacking factors that lack causal efficacy will not have any preventive impact, rather being a waste of time, effort and resources. David Farrington (2000, p. 7) neatly summarised the problem facing the risk factor approach: »a major problem with the risk factor paradigm is to determine which risk factors are causes and which are merely markers or correlated with causes« and he suggests that »wide-ranging explanatory theories need to be devised to explain all the risk factor results«.

3 Crime Events and Criminal Careers

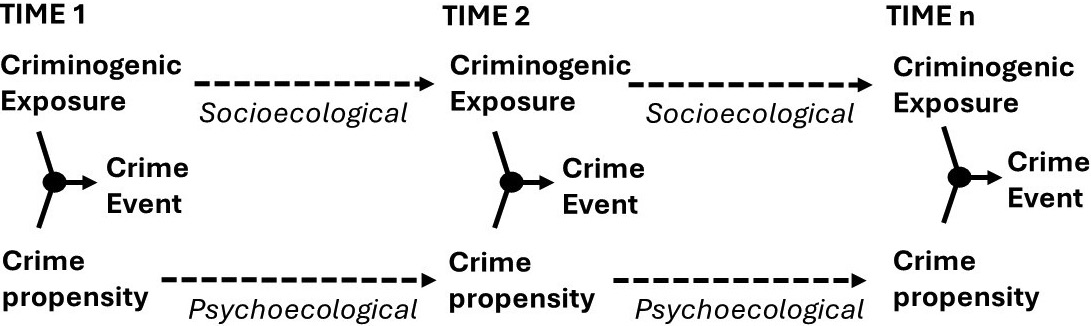

A criminal career is a series of crime events. To explain criminal careers, we therefore first need to explain what causes crime events to happen and then, on that basis, seek to explicate the ›causes of the causes‹, the processes that drives stability and change in the factors causing crime events to occur. My basic argument regarding the relationship between crime events and criminal careers, as developed in SAT and its DEA model, can be summarised as follows:

1. People engage in acts of crime because of the action alternatives they see and choose as a result of the interplay between who they are (their crime propensities) and the setting in which they take part (its criminogenic incentives), explaining the occurrence of crime events.

2. Stability and change in people’s crime involvement is a result of stability and changes in their crime propensity and criminogenic exposure – explaining their criminal careers (crime trajectories) – driven by psychoecological (crime propensity forming) and socioecological (criminogenic exposure providing) developmental processes (referred to as ›the causes of the causes‹ of crime events).

Which factors influence people’s crime propensity (their tendency to see and choose crime as an action alternative in particular circumstances) and settings criminogeneity (their tendency to normalise and encourage acts of crime), and what kind of psychoecological and socioecological developmental processes are implicated in their emergence, stability and change, are crucial questions in explanatory analyses of people’s crime and criminal careers. To answer these questions, we first need to be clear about what crime is, what a theory of crime causation should explain. An explanation needs to be an explanation of something, and clarity about what we need to explain helps us focus on what factors and processes may reasonably be involved in its causation. In the following, I shall outline the foundation and basic propositions of Situational Action Theory (SAT) and its Developmental-Ecological-Action model (DEA model) as regards the explanation of crime events and criminal careers.

4 Situational Action Theory – Basic Assumptions and Propositions.

What is crime (what is to be explained by a theory of crime causation)?

Crimes are actions that break the rules of law. The law is codified moral guidance for what we should and should not do in different circumstances. Explaining crime is ultimately a matter of explaining why some people perceive and choose to break a rule of the law as a response to a certain motivation in a particular circumstance. Focusing on explaining the rule-breaking rather than the criminalised act (e. g., using violence may be legal in some but not other circumstances and this may vary between jurisdictions and change over time) avoids the problem that what constitutes a crime can change from one day to the next through a political decision (because it is the rule-breaking – not the act – that is to be explained). It also means that its explanation applies to norm violations more generally since violations of the rules of the law is only a special case of violating rules of conduct[7]. There is, in principle, no difference between explaining why someone is cheating on their partner or why someone shoots a member of a rival gang. The action process (motivation – perceived action alternatives – action choices) is the same, although, and crucially, its content varies greatly.

What moves people to action (and to commit acts of crime)?

People are the source of their actions, but their causes are situational. People act as they do because of who they are (propensities) and the setting (incitements) in which they take part. Since people are different and settings are different, their specific combination tends to favour the perception of certain action alternatives in relation to the motivations (temptations, provocations) experienced in the circumstance, against which background the person (habitually or deliberately) makes their action-choices. Acts of crime are ultimately a result of the perception and choice of crime as an acceptable action alternative in response to a specific motivation in the circumstance.

People are rule-guided creatures. People act in response to a motivation, but their choice of action is guided by their personal morality (their rules of conduct) as applied to the moral norms (sensed behavioural expectations) of the setting in which they take part, tempered by key inner and outer action-controls, their ability to exercise self-control (inner control) and the settings deterrent qualities (outer control). Whether an act of crime is perceived and chosen is ultimately the result of the actor’s application of their personal morality to the moral context of the setting, net of the influence from any relevant and effective actioncontrols.

5 SAT’s Development-Ecological-Action Model – Basic assumptions and propositions

Why do people vary in their crime propensity and exposure to criminogenic settings’?

People develop and act in response to the content of the particular environments in which they take part, as conveyed in their interactions with the people they meet and socialise with, the activities they take part in, and the media they consume. People vary (and change) in the environments in which they partake – the kinds of people, activities and media they encounter and engage with – and this is a central part of the explanation of why they develop different crime propensities (as an outcome of the formation of their crime-relevant personal morality and ability to exercise self-control) and are differently exposed to criminogenic settings in their everyday life (settings whose moral norms and lack of deterrent qualities may incentivise acts of crime).

What developmental processes affect stability and change in people’s crime propensity and exposure to criminogenic settings?

The psychoecological processes of moral education and cognitive nurturing form and shape people’s crime-relevant morality and capacity for self-control (affecting their crime propensity). Crucial to crime relevant moral education is the extent to which the content of the environments (people, activities, media) in which people takes part justify, excuse, tolerate or ignore crime, or particular kinds of crimes, and thereby contribute to their acceptability and normalisation (see further, Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 66–90); while central to cognitive nurturing is the extent to which the environments in which the person partakes (e. g., family and school environments) provide naturally occurring training in such things as problem-solving, concentration, patience and restraint, affecting their ability to self-control[8] (see further, Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 90–93).

The socioecological processes of social and self-selection condition people’s exposure to criminogenic environments (settings incentivising or normalising crime, settings that sometimes overlap). Social selection[9] refers to the age-graded cultural (rule-based) and structural (resource-based) social forces that favour or constrain people’s access to and partaking in particular kinds of environments (manifested in general patterns of age and social group differentiation in environmental exposure). The, so called, ›birth lottery‹ is the strongest (most deterministic) example of social selection, people have no influence on the environments into which they are born. As people progress in life, they will develop an increasing, albeit differently efficacious, capacity to influence the course of their own life through self-selection. Self-selection refers to people’s competence and preference-based active navigation of their broader environment within the imagined and real constraints of social selection. People’s differential exposure to criminogenic settings (settings that instantly incentivise or gradually normalise crime) may be seen as an outcome of the combined workings of processes of social and self-selection, explaining, for example, why some young people from the same family, living in the same neighbourhood and going to the same school, may develop different lifestyles and, relatedly, different experiences of being exposed to criminogenic settings (see further, Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 93–104).

The outlined psychoecological and socioecological processes may be viewed as (ecologically related) developmental causal pathways in which past experiences set the stage for present influences which, in turn, set the stage for future influences. The development of a career of serious and persistent crime involvement may commonly be characterised as a slippery slope, where one thing leads to another (e. g., a gradually increasing exposure to criminogenic environments and an amplified crime propensity causing an escalating level of crime involvement), highlighting the need for pre or early career intervention to be a central part of policy and prevention if one wants to counter the development of pathways of serious and persistent crime.

What is the role of social context for the developmental processes?

People do not act and develop in a cultural and structural social vacuum. The psychoecological processes (moral education, cognitive nurturing) are context-dependent for their content and efficacy. The same holds for the socioecological processes of social- and self-selection. Nations vary in their moral climate (shared behavioural standards and expectations and their social homogeneity) and structural conditions (the level and distribution of human, social and financial capitals). This constitutes the broader social context in which the developmental processes operate and draw upon for their content and efficacy, with clear implications for the general (and social segment specific) development of crime relevant content, its efficacy of influence and expression. Importantly, while the suggested developmental processes are supposed to be universal, their social contexts are not.[10]

6 Situational Action Theory: Further on the Causes of the Crime Event: the PC-process.

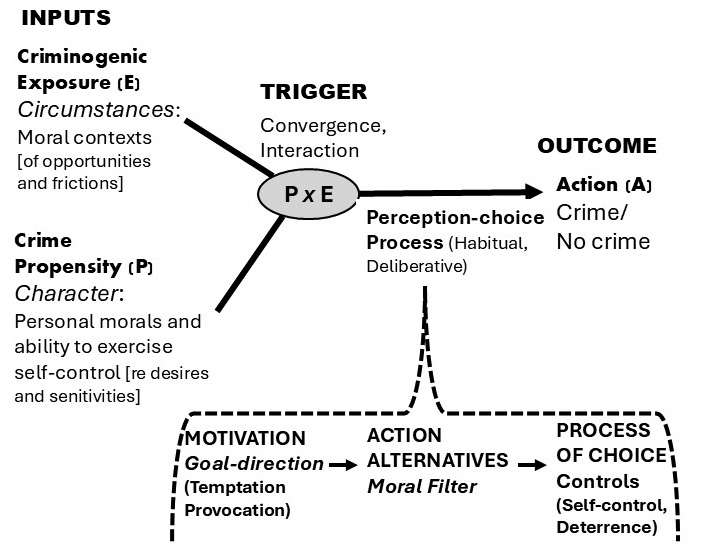

I have argued that the basis for the explanation of people’s criminal careers (crime trajectories) is the explanation of why crime events happen (something that DLC criminology has not paid that much attention to). In this section I shall expand somewhat on the suggested basic causal mechanism of the situational model of SAT, the perception-choice process[11], in short referred to as the PC-process (motivation – action alternatives – choice). As previously discussed, the PC-process is initiated and guided by the convergence and interaction of a person’s character-based crime propensity and the settings’ circumstance-based criminogeneity (Figure 1; for further details, and the groundings of the arguments, see, e. g., Wikström, 2006; 2010; Wikström et al., 2012, pp. 11–29; Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 29–64).

Motivation – goal directed attention.

People act for a reason (e. g., they wish to get, experience, or achieve something or they react to something). What motivates individuals in a circumstance may differ. People vary in their desires (wants, needs) and commitments and in their sensitivities. In their everyday life they confront opportunities to fulfil their desires or to honor their commitments which may create temptation (e. g., an urge to do something desired or promised). People will also encounter frictions (external unwanted interferences) in their daily life that may activate their sensitivities creating provocation (e. g., feelings of upset or anger that may favour confrontational responses). Temptations and provocations are the main motivational forces initiating goal-directed attention. Motivation is a necessary but not sufficient factor in the explanation of people’s actions (including their acts of crime). Motivation is the reason for acting, while morality affects its expression[12].

Perception of action alternatives – the moral filtering.

What action alternatives emerge as acceptable responses to a specific motivation (temptation, provocation), and if that involves an act of crime (rule-breaking), depends on the moral filtering that spontaneously occurs when people apply their personal morality (rules of conduct) to the moral context (sensed behavioural expectations) of the setting in which they take part[13]. If crime does not appear as an action alternative there will be no crime, with the important implication for crime prevention policy and practice that successfully attacking the processes that normalise crime (rule-breakings) as an action alternative in response to particular motivations is the most effective form of crime prevention (something that crime prevention rarely has as its focus). Importantly, people do not choose their action-alternatives (they just emerge), but they choose from among the action-alternatives they perceive.

The process of choice.

The fact that people choose their actions from the action alternatives they perceive in relation to a motivation suggests, that the perception of action alternatives is more fundamental to the explanation of their actions than the process of choice. The perception-choice process may be predominantly habitual (only perceiving one potent action alternative that is automatically chosen) or deliberative (perceiving different action alternatives that require some level of decision-making[14]). When people act out of habit, their choice is pre-determined (they act as they normally do in the circumstance without giving it much thought), when they deliberate, they exercise (constrained) ›free will‹, i. e., actively choose freely among perceived action alternatives[15]. Habitual behaviour is most likely when people act in familiar environments responding to familiar problems. A lot of human action is likely to be automated, although we know little about how important habits are for people’s crimes, and hence for their criminal careers, although it is easy to see that habit often may play a role in things like the occurrence of traffic crimes and partner violence (to mention a few examples). It is plausible that crime habit formation is most common among crimes (rule-breakings) that are committed regularly in similar circumstances.

Fig. 1: An outline of the basic situational model of SATs explanation of the occurrence of crime events and the key elements of its PC-process.

When people deliberate, action-controls may influence their decision, when they act out of habit they will not. People’s ability to exercise self-control, i. e., their executive functions based[16] capacity to act in accordance with their own morality when externally challenged, is the prime source of (inner) control (peer pressure is a prime example of an external challenge). The deterrent qualities of the setting, its capacity (by creating fear or worry of consequences[17]) to make people act in accordance with its moral norms when they consider a rule-breaking, is the prime source of (external) control. Importantly, action controls only affect people’s crime choices when they see crime as an action alternative and deliberate over whether or not to select this option for action (the SAT principle of the conditional relevance of controls). The main implication of this for crime prevention policy and practise is the importance of advancing strategy and methods with the aim (a) to counteract the emergence of, and to break existing, crime habits and (b) to affect people’s crime choices by influencing the efficacy of action-controls.

The Drivers of Criminal Careers (a series of crime events) illustrated.

Adapted from Wikström (2019b)

7 SAT – the DEA Model: Concluding comments on criminal careers as crime events and its study.

People develop and change over the life-course in relation to the general and age-graded content of the environments in which they take part and are influenced by, and this is an important part of the explanation of their crime involvement and its changes. If one accept the core propositions of SAT and its DEA model, that the causes of crime events are situational and that criminal careers[18] are a series of crime events, the basic question for DLC criminology becomes to explicate and study the stability and change in the personal and environmental factors, whose spatiotemporal convergence and interaction are involved in triggering the action-process that brings about crime events (rule breakings), and, crucially, the developmental processes that drives these factors’ stability and change.

Summarising the proposed explanation of criminal careers and their drivers.

The SAT based explanation of criminal careers as a series of crime events discussed in this paper can briefly be summarised as follows (illustrated in Figure 2):

1. Explaining criminal careers. Stability and changes in people’s crime propensity – based on the crime-relevant content of their personal morality and their ability to exercise self-control – and in their criminogenic exposure – based on the crime relevant moral norms (behavioural expectations) and their enforcement in the settings in which they take part and experience – is what jointly and interactively explains peoples’ criminal careers (their crime trajectories) and its key characteristics.

2. Explaining the drivers of criminal careers (the causes of the causes). The psychoecological processes of moral education and cognitive nurturing – affecting stability and changes in people’s crime propensity – and the socioecological processes of social selection and self-selection – affecting stability and changes in people’s criminogenic exposure – are the drivers (the causes of the causes) of stability and change in the factors causing crime events, providing an explanation for why people vary and change in their crime propensity and criminogenic exposure.

3. Explaining the content and efficacy of the drivers of criminal careers (the role of social context). The general and age-graded content and efficacy of the discussed crime-relevant developmental processes depend on the broader social context in which they are situated and operate – the particular historically formed cultural (moral climate) and structural (resource distributive) features of society and its various social segments – and this explains why the content and efficacy of the crime relevant developmental processes may vary between countries and among their social segments.

The causes of criminal careers are best studied as matched (concurrent) developments of people’s crime propensity, criminogenic exposures and crime involvement

A common argument in DLC criminology is the need to lag explanatory factors to establish causal order. However, because crime event causation is situational and longitudinal data collection typically is done on an annual or longer interval basis it does not make much sense to use lagged data (crime event causation is rather a question of minutes than of years). In fact, it makes the causality problem worse. Given that the causes of crime events are situational and that a criminal career is a series of crime events it makes much more sense to study how well explanatory factors temporally match (mirror) the development of crime involvement rather than analysing them as lagged. Ideally one would like to match people’s crime propensity and criminogenic exposure at the exact points in time of the crime events but there is to my knowledge no longitudinal study that has effectively achieved this, and it would obviously be practically difficult and very costly to do so, especially over any longer period of time[19]. The second-best solution, although not wholly unproblematic, is to study as closely as possible matched developments of explanatory factors and the outcome (which in practice often mean measured and matched on a yearly basis[20]), preferably justifying the selection of explanatory variables by the findings from situational research demonstrating their likely causal relevance in the explanation of crime events (further on this problem and how we have handled it in the PADS+ longitudinal study, see, Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 8–9, pp. 156–162).

There is a need to better measure the crime relevant moral and cognitively nurturing content of the environments in which people develop and act, to better enable the study of the role of the psychoecological processes of moral education and cognitive nurturing for people’s crime propensity.

DLC criminology is generally strong in describing the social characteristics of people’s developmental context, e. g., the key social features of their family, school and leisure environments, such as their resources (e. g., disadvantage), relationships (e. g., cohesion) and functioning (e. g., monitoring) and its statistical associations with the subject’s crime involvement[21]. What DLC criminology has been less good at is to capture the crime relevant moral and cognitively nurturing content of the social environments in which the subjects take part and develop, something that is crucial, I would argue, for the understanding of the processes of crime relevant moral education and cognitive nurturing and, therefore, for the understanding of the development of and changes to people’s crime propensity. Central to the crime relevant moral content of social environments (as transmitted by the people, activities and media encountered) is the extent to which they in the immediate term may incentivise, or in the longer-term may help to normalise, acts of crime (rule-breakings) by justifying, excusing, tolerating or ignoring their commission or intended commission[22]. Some measures commonly used in DLC criminology, such as ›peer delinquency‹ and ›parent’s criminality‹ may be seen as markers of exposure to potentially crime relevant moral content[23], but there is a need to more directly and comprehensively measure the crime relevant moral content of the environments to which people are exposed. When it comes to cognitive nurturing it is primarily a question of aiming to measure the extent to which people (and especially young people[24]) experience natural training in their daily life (through their activities and person interactions) of such things as problem-solving, concentration, patience and restrain which may strengthen their ability to exercise self-control (on the basis of their inherited cognitive capability). While the study of the social characteristics of environments (e. g., resources, relationships and functioning) may say something about conditions potentially affecting the efficacy of processes of moral education and cognitive nurturing, they say little about their moral and cognitively nurturing content[25], the latter being crucial to the understanding of environmental influences on people’s crime and criminal careers.

There is a need to better measure people’s exposure to different kinds of environments, its age-graded changes, and the socioecological process that are implicated in affecting people’s differential and changing environmental exposures.

The ecology of people’s lives and its age-graded changes (the people, activities and media they are exposed to, interact with, and are influenced by in their daily life) is crucial for the understanding of environmental influences on their actions and development, including their acts of crime and criminal careers. This is a very difficult area to properly investigate, especially longitudinally, but an area whose methodological improvement has a potentially high pay-off by providing new important insights in our understanding and testing of the role of the environment and its influences on the development and changes in people’s crime propensity and criminogenic exposure, and the socioecological processes that influence this exposure[26]. In our PADS+ longitudinal research we made a considered effort to better measure the kinds of environments in which people actually take part and its changes by combining a city-wide small-area community survey with a space-time budget methodology[27] (see, e. g., Wikström et al., 2010; 2011) and utilising ecometrics, measuring area collective efficacy to tap into some relevant (albeit restricted) aspects of area social and moral content (Oberwittler & Wikström, 2008). This in addition to collecting the kind of individual, family, school, work and neighbourhood data normally included in longitudinal research, enabling an improved investigation of the person-environment interaction and its changes than what would normally be the case (see, e. g., Wikström et al., 2012, pp. 44–106; 2024, pp. 115–146). Although I believe our data and research design is a significant improvement over what is currently available when it comes to exploring the ecology of crime and criminal careers, this being a virgin area of methodology, there is still much need for further innovation and elaboration for it to reach its full potential. The better we can explore people’s exposure to the different kind of environments in which they take part in their daily life, and their crime relevant content, the better the possibility to more effectively analyse and test the environmental impact on people’s crime involvement and criminal careers.

8 Testing SAT and its DEA model. Promising findings.

A theory is just a theory. It needs clear testable implications[28], proper testing and supportive findings to qualify as a good theory. This is not the place to review the increasing number of studies that have aimed to test various key propositions of SAT and its DEA model (that is for another day). Suffice to say at this point is, that the findings from our own PADS+ research (e. g., Haar & Wikström, 2010; Wikström et al., 2012, pp. 323–402; Wikström et al., 2018) and others’ research (e. g., Herrmann et al., 2025; Hirtenlehner & Mesko, 2025; Pauwels, 2018; Sattler et al., 2022) aiming to test predictions of the situational model are promising, as are the findings of our own PADS+ research (e. g., Wikström et al., 2024, pp. 219–397) and others’ studies (e. g., Chrysoulakis, 2022; Kessler & Reinecke, 2021) aiming to test some of the developmental predictions of the theory. The fact that the theory has been applied in studies of different types of crimes and in various parts of the world with generally supportive findings is encouraging (e. g., Botchkovar & Marshall, 2022; Brauer & Tittle, 2017; Craig, 2019; Serrano-Mailo, 2018; Fujino, 2023; Kabiri, 2025; Kafafian et al. (2022); Rose, 2023; Kokkalera t al., 2023; Shadmanfat et al., 2024; Trivedi-Bateman et al., 2024; Uhl & Hardie, 2025).

Although the empirical testing on the whole has been broadly supportive of the theory’s core propositions, there is still much need for additional testing and room for further elaboration and refinements of the theory and its particular propositions[29]. Science is always a work in progress.

Article Note

This paper builds on a talk I gave at Professor Klaus Boers retirement symposium at the University of Münster in June 2024. It was a great pleasure to take part in the celebration of Klaus’ highly distinguished career.

References

Ahonen, L., FitzGerald, D., Klingensmith, K. & Farrington, D. P. (2020). Criminal career duration. Predictability from self-reports and official records. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 30, 172–182.10.1002/cbm.2152Search in Google Scholar

Basto-Pereira, M. & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Advancing knowledge about lifelong crime sequences. British Journal of Criminology, 59, 354–377.10.1093/bjc/azy033Search in Google Scholar

Boers, K., Reinecke, J., Seddig, D. & Mariotti, L. (2010). Explaining the development of adolescent violent delinquency. European Journal of Criminology, 7, 499–620.10.1177/1477370810376572Search in Google Scholar

Brauer, J. R. & Tittle, C. R. (2017). When crime is not an option: Inspecting the moral filtering of criminal action alternatives. Justice Quarterly, 34, 818–846.10.1080/07418825.2016.1226937Search in Google Scholar

Craig, J. M., Piquero, A. R. & Farrington, D.P. (2020). Not all at-risk boys have bad outcomes. Predictors of later life success. Crime and Delinquency, 66, 392–419.10.1177/0011128719854344Search in Google Scholar

Craig, J. M. (2019). Extending Situational Action Theory to white-collar crime. Deviant Behavior, 40, 171–189.10.1080/01639625.2017.1420444Search in Google Scholar

Chrysoulakis, A. (2022). Morality, delinquent peer association, and criminogenic exposure: (How) does change predict change? European Journal of Criminology, 19, 282–303.10.1177/1477370819896216Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, I., Farrington, D. P. & Hoskin A. W. (2019). Handbook of crime correlates (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Farrington, D. P. (2000). Explaining and preventing crime. The globalization of knowledge. Criminology, 38, 1–24.10.1111/j.1745-9125.2000.tb00881.xSearch in Google Scholar

Farrington, D. P. & Wikström, P.-O. (1993). Criminal careers in London and Stockholm. A cross-national comparative study. In E. Weitekamp & H.-J. Kerner (Eds.), Cross-national and longitudinal research on human development and criminal behavior (pp. 386–399). Dordrecht: Kluwer.10.1007/978-94-011-0864-5_2Search in Google Scholar

Farrington, D. P., Loeber, R. & Ttofi, M. (2012). Risk and protective factors for offending. In B.C. Welsh & D.P. Farrington (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Crime Prevention (pp. 46–69). Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398823.013.0003Search in Google Scholar

Farrington, D. P., Kazemian, L. & Piquero, A. (Eds.) (2019). The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190201371.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Fujino, K. (2023). Application of Situational Action Theory in Japan using vignette survey. Asian Journal of Criminology, 18, 391–409.10.1007/s11417-023-09410-0Search in Google Scholar

Haar, D. H. & Wikström, P.-O. (2010). Crime propensity, criminogenic exposure and violent scenario responses: Testing Situational Action Theory in regression and Rasch models. European Journal of Applied Mathematics, 21, 307–323.10.1017/S0956792510000161Search in Google Scholar

Herrmann, C., Uhl, A., & Treiber, K. H. (2025). Peeking into the Black Box of Offender Decision-Making: A Novel Approach to Testing Situational Action Theory’s Perception Choice Process. Deviant Behavior (Online first).10.21428/cb6ab371.e8b282d0Search in Google Scholar

Hirtenlehner, H. & Mesko, G. (2025). Crime propensity and lifestyle risk. The interplay of personal morality and self-control ability in determining the significance of criminogenic exposure. European Journal of Criminology, 0, 0.10.1177/14773708251348321Search in Google Scholar

Jennings, W. G., Loeber, R., Pardini, D. A., Piquero, A. R. & Farrington, D. P. (2016). Offending from childhood to young adulthood. Recent results from the Pittsburgh Youth Study. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-25966-6Search in Google Scholar

Kabiri, S. (2025). Hunting in the digital jungle. Exploring cyberstalking with higher order moderation in Situational Action Theory. Journal of Criminal Justice, 98, (Online first).10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2025.102400Search in Google Scholar

Kafafian, M., Botchkovar, E. V. & Marshall, I. H. (2022). Moral rules, self-control, and school context: Additional evidence on Situational Action Theory from 28 countries. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 38, 861–889.10.1007/s10940-021-09503-ySearch in Google Scholar

Kessler, G. & Reinecke, J. (2021). Dynamics of the causes of crime: A life-course application of Situational Action Theory for the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 7, 229–252.10.1007/s40865-021-00161-zSearch in Google Scholar

Kokkalera, S. S., Marshal, C. E. & Marshall, I. H. (2023). Does national moral context make a difference? A comparative test of Situational Action Theory. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 3, 235–253.10.1080/01924036.2021.2008460Search in Google Scholar

Leblanc, M. & Frechette, M. (1989). Male criminal activity from childhood through youth. Multilevel and developmental perspectives. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4612-3570-5Search in Google Scholar

Loeber, R. (1990). Development and risk factors of juvenile antisocial behavior and delinquency. Clinical Psychology Review, 10, 1–41.10.1016/0272-7358(90)90105-JSearch in Google Scholar

Loeber, R. & Wikström, P.-O. (1993). Individual pathways to crime in different neighbourhoods. In D. P. Farrington, R. J. Sampson & P.-O. Wikström (Eds.), Integrating individual and ecological aspects of crime (pp. 169–204). Stockholm: Allmänna Förlaget.Search in Google Scholar

Loeber, R. & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Serious and violent offenders. Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.10.4135/9781452243740.n2Search in Google Scholar

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Raskin White, H., Wie, E. H. & Beyers, J. M. (2003). The development of male offending: Key findings from fourteen years of the Pittsburgh Youth Study. In T. Thornberry & M. Krohn (Eds.), Tacking stock of delinquency: An overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies (pp. 93–136). New York: Kluwer Academic.10.1007/0-306-47945-1_4Search in Google Scholar

Loeber, R., Slot, W. N. & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2006). A three-dimensional, cumulative developmental model of serious delinquency. In P.-O. Wikström P-O & R. J. Sampson (Eds.), The Explanation of Crime. Context, Mechanisms and Development (pp. 153–195). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511489341.006Search in Google Scholar

Lösel, F. (2003). The development of delinquent behaviour. In D. Carson & R. Bull (Eds.), Handbook of psychology in legal contexts (pp. 245–267). New York: John Wiley and sons.10.1002/0470013397.ch10Search in Google Scholar

Lösel, F. & Bender, D. (2009). Protective factors and resilience. In D. P. Farrington & W. Coid (Eds.), Early prevention of adult antisocial behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moffitt, T. E., (2018). Male antisocial behavior in adolescence and beyond. Nature: Human Behaviour, 2, 177–186.10.1038/s41562-018-0309-4Search in Google Scholar

Morizot, J. & Kazemian, L. (2015). Introduction: Understanding criminal and antisocial behavior within a developmental and multidisciplinary perspective. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior (pp. 1–16). New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-08720-7_1Search in Google Scholar

Nagin, D. S., Farrington, D. P. & Moffitt, T. E. (1995). Life-course trajectories of different types of offenders. Criminology, 33, 111–1139.10.1111/j.1745-9125.1995.tb01173.xSearch in Google Scholar

Oberwittler, D. & Wikström, P.-O. (2008). Why Small is Better. Advancing the study of the role of behavioral contexts in crime causation. In D. Weisburd, W. Bernasco & G. Bruinsma (Eds.), Putting Crime in Its Place: Units of Analysis in Spatial Crime Research (pp. 35–59). New York: Springer.10.1007/978-0-387-09688-9_2Search in Google Scholar

Osgood, W. (2012). Some future trajectories for life course criminology. In R. Loeber & B. C. Welsh (Eds.), The Future of Criminology (pp. 3–10). Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199917938.003.0001Search in Google Scholar

Pauwels, L. (2018) Analysing the perception–choice process in Situational Action Theory. A randomized scenario study. European Journal of Criminology, 15, 130–147.10.1177/1477370817732195Search in Google Scholar

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P. & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511499494Search in Google Scholar

Rose, C. (2023). To speed or not to speed: Applying Situational Action Theory to speeding behavior. Deviant Behavior, 44, 935–952.10.1080/01639625.2022.2114865Search in Google Scholar

Sampson, R. J. & Laub, J. (1995). Crime in the making. Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W. & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918–924.10.1126/science.277.5328.918Search in Google Scholar

Sattler, S., van Veen, F., Hasselhorn, F., Mehlkop, G. & Sauer, C. (2022). An experimental test of Situational Action Theory of crime causation: Investigating the perception-choice process. Social Science Research, 106.10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102693Search in Google Scholar

Serrano-Maillo, A. (2018). Crime contemplation and self-control: A test of Situational Action Theory’s hypothesis about their interaction in crime causation. European Journal of Criminology, 15, 93–110.10.1177/1477370817732193Search in Google Scholar

Shadmanfat, S. M., Kabri, S., Donner, C. M., Rahmati, M. M., Maddahi, J., Yousefvand, S., Hardyns, W., & Safiri, K. (2024). Cheating in Iran: An examination of academic dishonesty through the lens of Situational Action Theory. International Criminal Justice Review, 0, 0.10.1177/10575677241271201Search in Google Scholar

Thornberry, T. P., Krohn, M. D., Smith, C. A., Lizotte, A. J. Porter, P. K. (2003). Causes and consequences of delinquency: Findings from the Rochester Youth Development Study. In T. P. Thornberry & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Taking stock of delinquency. An overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies (pp. 11–46). New York: Kluwer Academic.10.1007/0-306-47945-1_2Search in Google Scholar

Treiber, K. & Wikström, P.-O. (2025). Cumulative risk as a marker of social context. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 35, 106–114.10.1002/cbm.2378Search in Google Scholar

Tremblay, R. E. (2015). Antisocial behavior before the age-crime curve. Can developmental criminology continue to ignore developmental origins? In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior (pp. 39–49). New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-08720-7_3Search in Google Scholar

Trivedi-Bateman, N., Markovska, A. & Serdiuk, O. (2024). The role of morality in corruption, theft, and violence, in a Ukrainian context. The European Journal of Criminal Policy and Research.10.1007/s10610-024-09598-6Search in Google Scholar

Uhl, A., & Hardie, B., (2025). Revisiting Bad Apples and Bad Barrels: Person x Setting Interactions in Corruption. Justice Quarterly (Online first).10.21428/cb6ab371.1f59ea8aSearch in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. (1990). Age and Crime in a Stockholm Cohort. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 6, 61–84.10.1007/BF01065290Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. (2006). Individuals, Settings and Acts of Crime. Situational Mechanisms and the Explanation of Crime. In P.-O. Wikström & R. J. Sampson (Eds.), The Explanation of Crime: Context, Mechanisms and Development (pp. 61–107). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press10.1017/CBO9780511489341.004Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. (2010). Explaining Crime as Moral Actions. In S. Hitlin & S. Vaysey (Eds.): Handbook of the Sociology of Morality (pp. 211–239). New York: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4419-6896-8_12Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. (2019a). Situational Action Theory. A General, Dynamic and Mechanism-based Theory of Crime and its Causes. In M. Krohn, G. P. Hall, A. J. Lizotte & N. Hendrix (Eds.), Handbook on Crime and Deviance (2nd ed., pp. 259–281), New York: Springer.Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. (2019b). Explaining Crime and Criminal Careers. The DEA model of Situational Action Theory. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology.10.1007/s40865-019-00116-5Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. & Treiber, K. (2016) ›Social Disadvantage and Crime. A Criminological Puzzle‹. American Behavioral Scientist, 60, 8.10.1177/0002764216643134Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O., Mann, R. & Hardie, B. (2018). Young people’s differential vulnerability to criminogenic exposure: Bridging the gap between people- and place-oriented approaches in the study of crime causation. European Journal of Criminology, 15, 10–31.10.1177/1477370817732477Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. & Treiber, K. (2018). The Dynamics of Change. Criminogenic Interactions and Life-Course Patterns of Crime. In D. P. Farrington, L. Kazemian & A. Piquero (Eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology (pp. 272–294). Oxford: Oxford University Press10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190201371.013.34Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. & Kroneberg, C. (2022). Analytic criminology. Mechanisms and methods in the explanation of crime and its causes. Annual Review of Criminology, 5, 179–203.10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-091320Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O., Oberwittler, D., Treiber, K. & Hardie, B. (2012). Breaking Rules. The Social and Situational Dynamics of Young People’s Urban Crime. Oxford. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O., Treiber, K. & Roman, G. (2024). Character, Circumstances and Criminal Careers. Towards a Dynamic Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198865865.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. (2019). Situational Action Theory. A General, Dynamic and Mechanism-based Theory of Crime and its Causes. In M. Krohn, N. Hendrix, G. Penly Hall & A. J. Lizotte (Eds.), Handbook of Crime and Deviance (2nd ed., pp. 259–281). New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-20779-3_14Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O. & Butterworth, D. (2006). Adolescent Crime: Individual Differences and Life-Styles. Willan Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O., Treiber, K. & Hardie, B. (2012). Examining the Role of the Environment in Crime Causation: Small Area Community Surveys and Space-Time Budgets. In S. Messner, D. Gadd & S. Karsted (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Criminological Research Methods (pp.111–127). Beverly Hills: Sage.10.4135/9781446268285.n8Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, P.-O., Ceccato, V., Hardie, B. & Treiber, K. (2010). Activity Fields and the Dynamics of Crime. Advancing knowledge about the role of the environment in crime causation. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26, 55–87.10.1007/s10940-009-9083-9Search in Google Scholar

Wolfgang, M., Figlio, R. M. & Sellin, T. (1972). Delinquency in a birth cohort. Chicago: Chicago University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wolfgang, M. (1983). Delinquency in two birth cohorts. In K. T. van Dusen & S. A. Mednick (Eds.), Prospective studies of crime and delinquency (pp. 7–16). Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/978-94-009-6672-7_2Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Internationales Kriminologisches Symposium in Münster

- Artikel

- Explaining Criminal Careers As Crime Events

- Corporate delinquency and corporate sanctions: A dilemma for the criminological critique of criminal law?

- Neue Gesichter sozialer Kontrolle: Abstrakte Außenseiter

- The rise of criminology in the Netherlands: contributing factors and outlook

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Internationales Kriminologisches Symposium in Münster

- Artikel

- Explaining Criminal Careers As Crime Events

- Corporate delinquency and corporate sanctions: A dilemma for the criminological critique of criminal law?

- Neue Gesichter sozialer Kontrolle: Abstrakte Außenseiter

- The rise of criminology in the Netherlands: contributing factors and outlook