Abstract

Balancing environmental protection with economic stability is a critical policy challenge worldwide. This article investigates the employment effects of one of China’s flagship green policies, leveraging the staggered rollout of the ecological civilization construction demonstration zones (ECCDZ) as a quasi-natural experiment. Our findings indicate that the designation of an ECCDZ leads to a significant reduction in firm-level employment. The mechanism analysis reveals two primary channels: firms reduce employment in response to both rising environmental compliance costs and a contraction in production scale. Further analysis shows that this adverse employment effect is more pronounced for larger firms, firms in labor- and capital-intensive sectors, firms with poor ESG performance, and those operating under stricter external environmental oversight. Our findings offer important policy implications for navigating green transitions in developing economies.

1 Introduction

A sustainable natural environment is fundamental to long-term human prosperity. However, the economic progress of developing nations has often been accompanied by significant pollution (Feng et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019). Environmental challenges such as pollution, resource depletion, and ecological degradation threaten human well-being by disrupting essential systems like food chains and water supplies (Bhuiyan et al., 2018; Guo & Xiong, 2023; Laurila-Pant et al., 2015; Pascual et al., 2021). In 2013, China’s National Development and Reform Commission, along with several other government departments, jointly issued the “Notice on the Construction Plan for National Ecological Civilization Construction Demonstration Zones.” This policy initiative laid out a comprehensive framework for promoting resource conservation, protecting natural ecosystems, and improving environmental quality. As economies and environments become more deeply coupled, policymakers must account for regional heterogeneity in resource endowments, developmental stages, and ecological functions to ensure a just and efficient transition (Zhang & Hu, 2023).

The ecological civilization construction demonstration zone (ECCDZ) is a key policy initiative designed to advance China’s green transition (Liang et al., 2022). However, such environmental regulations often raise concerns about their potential impact on economic growth. A primary concern is that stricter environmental supervision may indirectly affect firms’ labor demand by altering production costs and worker productivity (Stocker et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2022). Since efficient labor allocation is crucial for enhancing productivity and competitiveness (Stocker et al., 2015), balancing ecological goals with social welfare considerations like “stable employment” is essential (Huang & Lanz, 2018; Li & Lin, 2022; Liu et al., 2017; Zhang, 2023). As traditional drivers of job growth become less reliable, the interplay between macro-policies governing environmental protection and the labor market has become increasingly important. Consequently, understanding how firm-level employment responds to environmental regulation is now a central question for both policymakers and academic researchers.

Building on this background, this study investigates the relationship between the establishment of ECCDZs and firm-level labor employment. Existing literature on the ECCDZ policy has primarily focused on its environmental outcomes, such as its effects on carbon emissions (Wang et al., 2022a; Zhang & Wang, 2024) and ecological efficiency (Liang et al., 2022; Lu & Xiong, 2020) or on program evaluation (Li & Hu, 2015; Xiong, 2020). A separate and extensive body of research examines the broader relationship between environmental regulation and labor demand, yet this literature remains divided (Grosset et al., 2023; He et al., 2020). One stream of research posits that environmental regulations can stimulate innovation and ultimately have a neutral or even positive effect on employment (Ferris et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2021a). In contrast, another stream argues that these regulations primarily harm employment by increasing firms’ operational costs and crowding out productive investment (Chen et al., 2018; Cui & Jiang, 2021; Wang et al., 2022a; Zhang, 2019). Given that China has the world’s largest labor force (Wei et al., 2023), understanding this relationship is of paramount importance. This arrticle contributes to the literature by providing firm-level evidence from China’s county-level policy implementation. The county is a fundamental administrative unit for economic and social development in China (Zhang & Xu, 2011), and analyzing data at this granular level is crucial for optimizing resource allocation and fostering sustainable growth (Wang et al., 2023). While most employment research in China has focused on broader urban or regional levels (Liu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2023), using firm-level data linked to county-level policy shocks allows for a more precise identification of microeconomic responses. This approach enhances the internal validity of our analysis by minimizing confounding factors that can affect studies at more aggregated levels.

This study provides the first empirical investigation into the employment effects of China’s ECCDZ policy. Our results support the hypothesis that ECCDZ designation inhibits firm-level employment by reducing firms’ production scale and increasing their environmental compliance costs (Liu et al., 2021a; Wang et al., 2022a). The theoretical insights and empirical findings of this research offer a valuable reference for policymaking in China and other developing economies seeking to balance ecological goals with employment stability. Furthermore, our work contributes to the broader understanding of sustainable development and industrial upgrading in a global context.

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. (1) While existing research on labor demand often focuses on broad macroeconomic factors (Bas & Paunov, 2021; Leblebicioğlu & Weinberger, 2021; Li et al., 2021a) or firm-specific microeconomic drivers (Blanchard & Giavazzi, 2003; Palumbo & Tridico, 2019; Petreski, 2021), our article provides novel, quasi-experimental evidence on the employment consequences of a place-based environmental policy. By constructing a difference-in-differences (DID) model to establish causal inference (Beck & Levkov, 2010; Bertrand et al., 2004; Li et al., 2016), we offer a new framework for analyzing the trade-offs inherent in green transitions. We find that the ECCDZ policy inhibits labor employment by reducing production scale and increasing pollution control costs, thereby highlighting the urgent need for complementary policies such as labor redistribution programs. (2) This study goes beyond the average treatment effect to explore the heterogeneous impacts of the ECCDZ policy across firms. By examining how the employment effect varies with firm size, ESG rating, factor intensity, and the stringency of external environmental oversight, our study addresses a critical gap in the literature (Ren & Li, 2019; Ren et al., 2020). This heterogeneity analysis provides a nuanced evidence base for policymakers, enabling the design of more targeted interventions to support vulnerable firms and workers during the construction of an ecological civilization. By empirically evaluating a major environmental initiative, this study offers insights into creating effective synergies between ecological and employment policies. Our findings can inform the design of better development models that pursue both environmental sustainability and inclusive growth, not only in China but also in other emerging economies.

2 Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

One perspective suggests that the establishment of ECCDZs could promote firm-level employment. The clear assessment indicators and stringent environmental standards within these zones may compel firms to undertake proactive measures, such as modifying production processes and improving resource efficiency. According to the Porter Hypothesis, such environmental regulations can stimulate technological innovation (Wang et al., 2023), leading to an “innovation compensation” effect. This effect can manifest in several ways: enhanced productivity (He et al., 2020; Morgenstern et al., 2002), which offsets compliance costs; increased demand for clean technologies; and an expanded market share driven by green competitiveness (Qiu et al., 2021). Ultimately, these innovation-driven improvements in productivity and profitability could boost firms’ labor demand (Horbach & Rennings, 2013). Empirical evidence from China supports this view. For instance, studies by Ren and Li (2019) and Ren et al. (2020) demonstrated that certain environmental regulations increased labor demand within firms. Similarly, Dang et al. (2025) found that China’s National Forest City Construction policy increased local employment by an average of 7.08% in participating prefectures.

Furthermore, environmental compliance can create new types of jobs. To meet stricter standards, firms often must install emission-reducing equipment or alter production processes, which can increase the demand for specialized technical personnel such as environmental engineers and ecological management specialists (Liu & Xiao, 2022). Additionally, environmental regulations may induce factor substitution. For example, Yamazaki (2017) found that a carbon tax in British Columbia had no net negative impact on employment because it prompted firms to substitute labor for more expensive, pollution-intensive energy inputs.

Conversely, a substantial body of literature argues that the ECCDZ policy is more likely to inhibit employment. The primary mechanism is the cost effect: stringent environmental regulations increase firms’ production costs, which can lead to reduced output and a subsequent decline in the demand for all inputs, including labor. This pressure may be particularly acute for heavily polluting firms, potentially forcing them to downsize, relocate, or even exit the market, resulting in job losses and costly labor transitions (Hille & Möbius, 2019; Walker, 2013; Wang et al., 2022b). This adverse effect is expected to be more severe in high-pollution, energy-intensive, and labor-intensive industries (Hille & Möbius, 2019; Liu et al., 2021b). Empirical studies frequently document this negative relationship. For instance, Wang et al. (2022b) reported that environmental policies in China amplified pollution control expenses, causing a 6.8% decline in firm-level labor demand. Similarly, Liu et al. (2021b) found that pollution control policies led to a 3% reduction in labor demand among Chinese manufacturing firms. Evidence from other contexts also shows that regions and industries facing stricter regulations often experience slower employment growth (Kahn & Mansur, 2013; Walker, 2013).

Given these competing theoretical arguments and the weight of empirical evidence suggesting negative cost effects, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: The establishment of an ECCDZ will inhibit firm-level labor employment.

The establishment of ECCDZs imposes a range of environmental standards on firms, covering metrics from air and water quality to energy consumption and carbon intensity. To meet these requirements, firms must undertake pollution control activities, which inevitably alter their cost structure and, consequently, their labor demand. The impact of these rising environmental costs on employment, however, can be viewed from two competing perspectives.

One perspective suggests that rising environmental governance costs may actually boost labor employment. These costs can be categorized into those related to source control and intermediate processes. Regarding source control, firms must increase investment in pollution abatement technologies and decontamination devices. The operation and maintenance of such equipment often require additional labor, potentially stimulating demand for new personnel. This effect may be particularly strong for high-skilled labor, such as environmental compliance staff and specialized technicians (He et al., 2020). Echoing the Porter Hypothesis, some argue that these regulations spur innovation, leading to the adoption of cleaner technologies that enhance productivity and ultimately expand employment (Porter & van der Linde, 1995). Regarding intermediate processes, reconfiguring or rebuilding highly polluting production lines also requires significant capital, technical, and human resource inputs, potentially generating employment opportunities (Fankhauser & Jotzo, 2018; Xie & Teo, 2022). Conversely, an opposing view posits that rising environmental governance costs will ultimately constrain labor employment. Environmental protection inputs, such as investments in pollution reduction equipment, directly raise firms’ procurement and operational costs. These additional expenses can erode profits, crowd out productive investment, and lead to an overall decline in labor demand. From an intermediate governance viewpoint, the closure of a highly polluting production line would directly reduce a firm’s production scale and efficiency, leading to an immediate fall in labor demand. While firms may also attempt to innovate, thereby increasing demand for some technical personnel, the theory of regulatory compliance costs suggests that the net effect is likely to be negative. Regardless of the specific compliance strategy, the increase in non-productive expenditures restricts a firm’s capacity to expand, potentially leading to a contraction in its workforce (Autor et al., 2013; Curtis, 2018). Ultimately, this can result in job losses and hinder economic growth.

Based on the argument that the negative cost effects are likely to dominate the positive job creation effects, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: The ECCDZ establishment will inhibit labor employment by increasing firms’ environmental compliance costs.

Another way the ECCDZ establishment may affect employment is by altering firms’ production scale. The theoretical effect of this channel is also ambiguous. On the one hand, a reduction in production scale could paradoxically stimulate certain types of employment. In the short term, environmental policies may increase costs and force a contraction in scale. To maintain profitability, firms might respond by pursuing technological innovation to increase the added value of their products, which could in turn raise the demand for high-skilled labor. In the long term, improved local air quality and an upgraded industrial structure might attract new talent, further boosting local employment. This is consistent with evidence from Berman and Bui (2001), who studied air pollution regulations in the United States and found that stricter rules, despite reducing production scale, did not consistently lead to lower employment in refineries and, in some cases, even marginally increased labor demand.

On the other hand, a reduction in production scale is more likely to hinder overall employment. Faced with environmental regulations, firms must weigh the economic costs of scaling down, such as reduced operating revenues and inventory adjustments. To meet mandated emission levels in the short term, one of the most direct methods for a firm is to simply reduce its production volume. This can quickly lead to labor saturation and subsequent layoffs. While some displaced workers may find new jobs, others may face prolonged unemployment due to skill mismatches or other constraints. This negative scale effect is well-documented; environmental regulations can reduce labor demand by raising compliance and production costs (Liu et al., 2017), which crowds out productive investment and forces firms to contract their scale of operations (Walker, 2013).

Therefore, we hypothesize that the negative consequences of a reduced production scale will outweigh any potential positive effects on specialized labor.

H3: The ECCDZ establishment will inhibit labor employment by decreasing firms’ production scale.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Research Design

The DID approach is a leading method for policy evaluation (Guo et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023). Its core concept is to treat the implementation of new policies as a “natural experiment” that is external to the economic system. While ECCDZ establishment could cause differences in enterprise labor employment over time, it might also cause differences in labor employment between demonstration zones and non-demonstration zones concurrently. Using the DID model for estimation can scientifically assess the net impact of policy implementation. Thus, the ECCDZ list is considered a quasi-natural experiment. Accordingly, the following multi-period DID model was constructed for testing:

where Labor it denotes enterprise labor employment; i, t denote cities and time, respectively; C it denotes a vector of control variables; ω denotes the parameter to be estimated for the control variables; α i , β t , γ i denotes the fixed effects for industry, time, and province, respectively; ε it denotes the random error term; Treat × Post denotes the virtual variable of the ECCDZ; ϕ 0 denotes the constant term; and ϕ 1 denotes the core coefficient of interest, reflecting the policy impact of the ECCDZ.

3.2 Sample and Data

This study uses the staggered implementation of the national ECCDZ policy to construct our treatment and control groups. The first cohort of ECCDZs was announced in 2017, with six subsequent cohorts designated between 2019 and 2023 (collectively referred to as the “List”). The list comprises prefecture-level cities, districts, and counties. Considering the precision of the objects examined, the actual effect of policy implementation, and data availability, this study selected the administrative units (at the city and district levels) listed between 2012 and 2023 as the research objects. The experimental group comprised 311 cities and districts selected from the list, whereas the control group comprised the other 93 cities and districts on the list, with panel data analyzed for both sets. The lists of ECCDZ designations and regional-level data were compiled from the China City Statistical Yearbook and the Provincial and Municipal Statistical Yearbook. Missing regional data points were imputed using the smoothing index method. In addition, this study used listed companies panel data during 2012–2023, excluding financial, ST, and *ST listed companies under the classification standard of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, and removed samples lacking crucial data. To eliminate the effect of outliers on the robustness of the regression results, we winsorized all continuous variables at the 1% level. Finally, 38,764 sample observations were collected. Of note, all firm-level financial data were sourced from the CSMAR database.

3.3 Variables

Explained variable: enterprise labor employment (Labor) is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of employed workers (Wang & Zhou, 2023).

Explanatory variable: ECCDZ is a pilot policy that has been implemented since 2017, with new batches of pilot cities designated annually until 2023. We obtained each batch of pilot cities from the official website of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China and constructed the core variable ECCDZ (Treat × Post) for the multi-period DID. Here, Treat is a categorical variable. If the city where the enterprise is located is selected as a “policy pilot for ecological civilization construction demonstration zone,” it is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0. Post is a time variable. If the year of the city where the enterprise is located is the year selected as the “Ecological Civilization Construction Demonstration Zone Policy Pilot” or a subsequent year, it is set to 1. Otherwise, it is set to 0. ECCDZ (Treat × Post) is the interaction term between Treat and Post, which equals 1 if the city where the enterprise is located is selected as a pilot zone and the time falls within the year of designation or subsequent years, and 0 otherwise.

Control variables: Firm size (Size) is measured by the natural logarithm of the enterprise’s total assets. Typically, larger enterprises tend to employ more labor. Additionally, several financial indicators were used to evaluate enterprise operations. Of note, asset–liability ratio (Lev) = total liabilities/total assets; return on equity (ROE) = net profit after tax/average net assets of the enterprise; total assets turnover (ATO) = net operating revenue/average total assets; quick ratio (Quick) = quick assets/current liabilities; fixed assets ratio (FIXED) = ending fixed assets/ending total assets. The better the enterprise’s operations, the more labor will be employed. In addition, management age (TMTAge) and management compensation (TMTPay) were used to depict the characteristics of senior executives. While TMTAge is denoted by the average age of management, TMTPay is denoted by the natural logarithm of the total management salary. Furthermore, board size, the proportion of independent directors, and CEO–chair duality (Dual) serve to illustrate the corporate governance structure, as it captures how governance mechanisms such as power allocation, incentives, and monitoring fundamentally shape firm-level employment decisions (Ghaly et al., 2020; Mueller et al., 2017). Notably, Board is evaluated by the natural logarithm of the number of directors; Indep is equal to independent directors/directors; and Dual is a dummy variable. If the chairman and general manager were the same person, the value was 1; otherwise, it was 0. Moreover, CEO–chair duality weakens the board’s oversight function over management, leading to excessive concentration of power in the CEO and exacerbating agency problems. A powerful CEO may make inefficient hiring decisions when pursuing personal interests, such as overhiring during periods of excessive investment or indiscriminate layoffs during periods of underinvestment. Furthermore, the robustness of our results to the inclusion of the Dual variable was confirmed through two sensitivity analyses. First, we tested the robustness of our estimates against potential omitted variable bias using the method of Cinelli et al. (2024). The results show that the estimated coefficient remains negative and statistically significant, even when simulating the inclusion of an unobserved confounder up to three times as influential as our observed controls, and the original estimated coefficient remains statistically significant. Second, we re-estimated our baseline model after excluding the “Dual” variable. The results confirmed that the coefficient for Treat × Post remains negative and highly significant (−0.077, t = −4.844), and its magnitude is nearly identical to our main specification. Regarding the macro-economy, the level of economic development (GDP) is denoted by the natural logarithm of the gross domestic product (gross domestic product). Finally, we included control variables for industry, year, and province, as shown in Table 1. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables.

Variables

| Types of variables | Variables | Symbols | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Labor employment in enterprises | Labor | Natural logarithm of the number of employed labors |

| Explanatory variable | Ecological construction | Treat × Post | When the enterprise is located in the first five batches of ecological zones, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0 |

| Control variables | Enterprise size | Size | The natural logarithm of total assets as of the reporting period |

| Asset-liability ratio | Lev | Total liabilities/Total assets | |

| Return on equity | ROE | Net profit after tax/Average net assets | |

| Total assets turnover | ATO | Net operating revenue/Average total assets | |

| Quick ratio | Quick | Quick assets/Current liabilities | |

| Management age | TMTAge | Average age of management | |

| Management compensation | TMTPay | Natural logarithm of total management salary | |

| Proportion of fixed assets | FIXED | Ending fixed assets/Ending total assets | |

| Economic | GDP | Natural logarithm of gross domestic product | |

| Board size | Board | Natural logarithm of the number of directors | |

| Proportion of Independent directors | Indep | Independent directors/Directors | |

| Chair-CEO duality | Dual | If the chairman and general manager are the same, the value is 1, otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Industry | IND | Industry pseudo-variable | |

| Year | YEAR | Year pseudo-variable | |

| Province | PROVINCE | Province pseudo-variable |

Descriptive statistics

| Variables | Sample size | Average | Min | Median | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor | 38,764 | 7.580 | 4.758 | 7.490 | 11.080 | 1.246 |

| Treat × Post | 38,764 | 0.415 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.493 |

| Size | 38,764 | 22.230 | 19.960 | 22.030 | 26.320 | 1.292 |

| Lev | 38,764 | 0.411 | 0.053 | 0.401 | 0.889 | 0.205 |

| ROE | 38,764 | 0.059 | −0.624 | 0.071 | 0.351 | 0.131 |

| ATO | 38,764 | 0.628 | 0.073 | 0.538 | 2.550 | 0.420 |

| Quick | 38,764 | 2.173 | 0.195 | 1.326 | 15.950 | 2.532 |

| TMTAge | 38,764 | 49.460 | 41.610 | 49.530 | 57.000 | 3.199 |

| TMTPay | 38,764 | 14.670 | 13.060 | 14.630 | 16.640 | 0.691 |

| FIXED | 38,764 | 0.202 | 0.002 | 0.170 | 0.676 | 0.154 |

| GDP | 38,764 | 11.310 | 10.280 | 11.360 | 12.210 | 0.461 |

| Board | 38,764 | 2.110 | 1.609 | 2.197 | 2.639 | 0.196 |

| Indep | 38,764 | 37.770 | 33.330 | 36.360 | 57.140 | 5.346 |

| Dual | 38,764 | 0.305 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.461 |

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Baseline Regression

Using the multi-period DID model, we analyzed the impact of the ECCDZ establishment on enterprise labor employment. Table 3 presents the findings. Columns (1) and (2) display the impact of the ECCDZ establishment on enterprise labor employment with and without the progressive introduction of control variables. The findings demonstrate that after accounting for individual, time, region, and industry fixed effects, the coefficient of the interaction term for the ECCDZ – that is, the estimated coefficient of our explanatory variable (Treat × Post), is remarkably negative and statistically significant. Considering the regression results of the fixed-effects model comprising all control variables in Table 3 [column (2)] as the final result, the estimated coefficient of the explanatory variable (Treat × Post) was −0.077 (p < 0.01). This result indicates that, compared with non-ECCDZ firms, ECCDZ designation exerted a detrimental impact on labor employment, thereby hindering its enhancement. Interpreting the economic significance, our analysis demonstrates that firms in ECCDZ regions exhibited an average 4–6 percentage point reduction in employment compared to non-ECCDZ regions over a 2–3-year period post-establishment. This outcome provides robust empirical verification of the significant policy-driven suppressive effect of ECCDZ establishment on labor employment. Therefore, H1 is supported.

Results of baseline regression

| Variables | Labor | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Treat × Post | −0.058* | −0.077*** |

| (−1.929) | (−4.865) | |

| Size | 0.754*** | |

| (73.849) | ||

| Lev | −0.188*** | |

| (−3.048) | ||

| ROE | −0.073 | |

| (−1.444) | ||

| ATO | 0.595*** | |

| (18.123) | ||

| Quick | −0.047*** | |

| (−13.499) | ||

| TMTAge | 0.017*** | |

| (6.306) | ||

| TMTPay | 0.054*** | |

| (3.565) | ||

| FIXED | 1.023*** | |

| (13.405) | ||

| GDP | −0.134 | |

| (−1.196) | ||

| Board | 0.127** | |

| (2.525) | ||

| Indep | −0.000 | |

| (−0.002) | ||

| Dual | 0.032** | |

| (2.128) | ||

| Constant term | 7.602*** | −9.930*** |

| (365.918) | (−7.710) | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| N | 39,221 | 38,764 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.148 | 0.746 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

4.2 Robustness Test

4.2.1 Parallel Trend Test

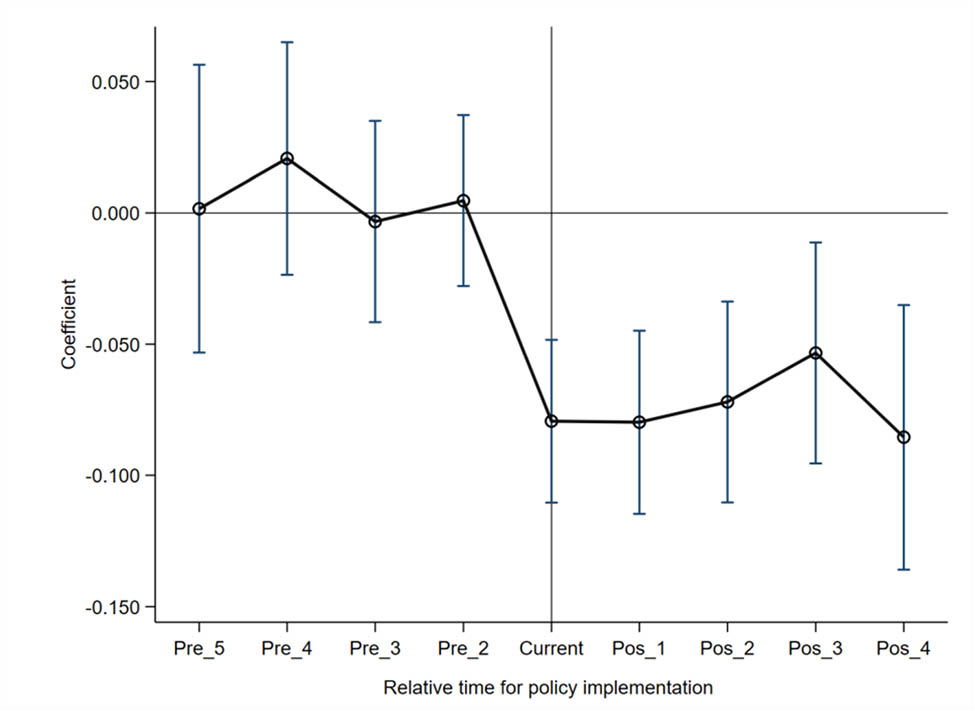

A key assumption of the DID model is that both the experimental and control groups exhibited parallel trends prior to the policy intervention (Beck & Levkov, 2010; Li et al., 2016). Before policy implementation, no notable differences were observed in labor employment between the experimental and control groups. Only in this way can the effect coefficient replicate the impact of the national ECCDZ. Therefore, following Beck and Levkov (2010) and using the year before the list was published (i.e., 2016) as the baseline, Figure 1 shows the findings. In the 9 years leading up to the release of the ECCDZ list, the estimated coefficients were not statistically significant, suggesting that there was no discernible difference in labor employment between demonstration zones and non-demonstration zones before the publication of the list, thus satisfying the parallel trend assumption. Following the implementation of the ECCDZ policy, the coefficients become negative and statistically significant, and their magnitude increases over time. This dynamic effect suggests that the policy’s adverse impact on employment is not only immediate but also intensifies in the subsequent years, indicating a sustainable inhibitory effect.

Results of the parallel trend test.

4.2.2 Placebo Test

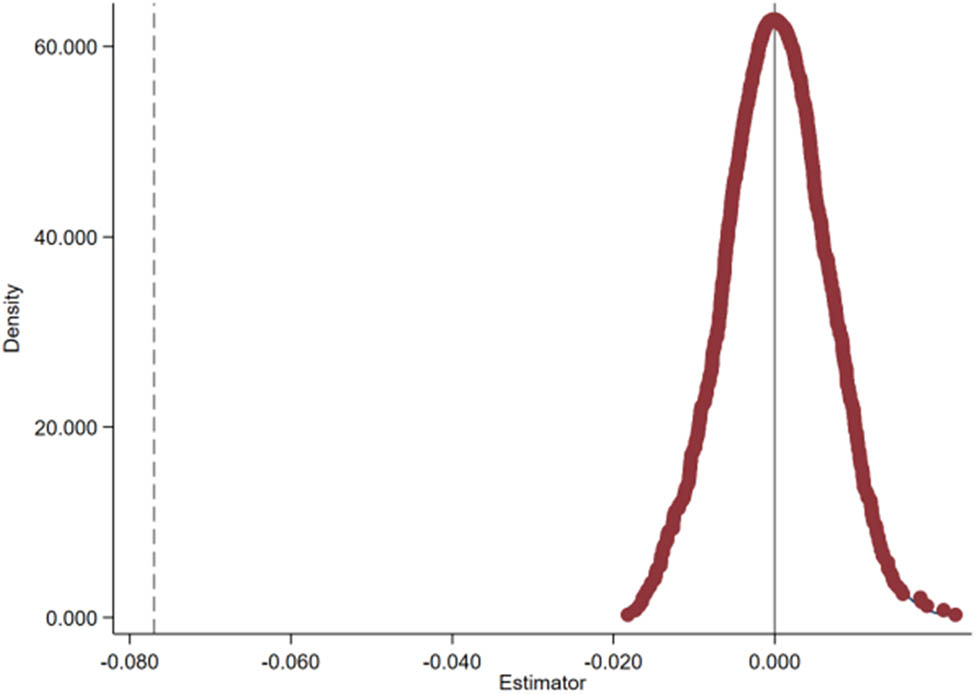

While the baseline regression results indicate that the ECCDZ establishment reduced labor employment, these results might be influenced by unobserved random factors like environmental conditions and other concurrent policies. Thus, we constructed a placebo test through random sampling by randomly generating the policy implementation year and the interaction terms of these pseudo-virtual policies (Li et al., 2022).

Regression analysis was performed across 1,000 random sampling iterations using model (1) to improve the credibility of the placebo test. Figure 2 presents the placebo test results. Figure 2 shows that the majority of the randomly generated test coefficients are centered around 0.00, suggesting a significant deviation from the estimated coefficient of the benchmark regression (dashed line value = −0.077). This test provides strong evidence that our main finding is attributable to the ECCDZ policy itself, rather than to other unobserved policies or random factors.

Placebo test coefficient.

4.2.3 Heterogeneity of DID

Due to the continuity and phased implementation of the ECCDZ policy, the treatment groups did not experience the policy shock simultaneously. This may lead to biased estimation in multi-period DID models during empirical analysis (Baker et al., 2022). The primary reason is that the multi-period DID estimator inherently represents a weighted average of multiple heterogeneous treatment effects, where weights can be negative. When negative weights exist, the resulting average treatment effect obtained from weighting these heterogeneous effects can exhibit the opposite sign compared to the true average treatment effect (Baker et al., 2022). Thus, following Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021), we used the inverse probability weighted least square method to calculate the “heterogeneity-robustness” estimator for further stability tests of the benchmark regression. The model is as follows:

where ATTimp presents nonparametric estimators under the inverse probability weighted least square method; g denotes the group divided per the first treatment time; t is time; ω(g,t) denotes different weight combinations; and θ represents the average treatment effect under different weight combinations.

We calculated the average treatment effect through the four weight combination methods explained by Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021): (1) simple weighted average treatment effect (Simple ATT); (2) group average treatment effect (Group ATT), the average treatment effect of weighted summation grouped per the first treatment time (g); (3) dynamic average treatment effect (Dynamic ATT), the average treatment effects of weighted summation grouped by time since the first treatment; and (4) calendar average treatment effect (Calendar ATT), the average treatment effect weighted and summed by normal year grouping. Table 4 presents the results. All four aggregated treatment effects are negative and statistically significant. The consistency of these findings, calculated using different weighting schemes, robustly confirms the negative average treatment effect of the ECCDZ policy. This mitigates concerns about estimation bias from heterogeneous treatment effects and reinforces the robustness of our baseline findings.

Robustness results of heterogeneity

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. err. | Z | P > |Z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group ATT | −0.098*** | 0.018 | −5.25 | 0.000 |

| Simple ATT | −0.095*** | 0.021 | −4.49 | 0.000 |

| Calendar ATT | −0.093*** | 0.017 | −5.34 | 0.000 |

| Dynamic ATT | −0.076*** | 0.025 | −3.02 | 0.003 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively.

4.2.4 Endogeneity

To address endogeneity, we conducted the following analyses. Table 5 presents the results. (1) The one-period lag of the ECCDZ (Treat × Post) was used as the explanatory variable for estimation. The regression coefficients of model (1) were significant at the 5% level, indicating a lagged effect of the ECCDZ establishment on enterprise labor employment, which also suggests that the endogeneity issue is not severe at the outset. (2) The existence of an ecocity and a low-carbon county in the region (Treat × Post), which lagged one and two periods, was selected as an instrumental variable for the current ECCDZ (Treat × Post) and regressed using the fixed-effects Two Stage Least Square (2SLS) model. The outcomes of model (2) demonstrate that the regression coefficients were significant at the 1% level. (3) Considering that the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation is more effective than 2SLS estimation in the case of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity in panel data, we also used the differential GMM method to estimate the dynamic panel model. Model 3 demonstrated that the regression coefficients were significant at the 5% significance level. Overall, the findings establish that the research hypotheses of this study are further validated after accounting for endogeneity issues.

Regression results of endogeneity

| Variables | Labor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Treat × Post | −0.074*** | −0.035** | −0.111*** |

| (−5.132) | (−2.268) | (−9.676) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant terms | −9.744*** | −8.764*** | — |

| (−6.687) | (−5.648) | — | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 32,933 | 27,530 | 27,023 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.712 | 0.713 | 0.375 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

Robustness test results

| Variables | PSM-DID | Alter the dependent variable | Change observation period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treat × Post | −0.077*** | −0.078*** | −0.004*** | −0.069*** |

| (−4.879) | (−4.904) | (−6.928) | (−3.785) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant terms | −9.898*** | −9.643*** | −0.073 | −12.508*** |

| (−7.540) | (−7.070) | (−0.890) | (−8.948) | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 38,446 | 37,475 | 32,933 | 21,370 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.746 | 0.746 | 0.050 | 0.749 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

4.2.5 Other Robustness Tests

Propensity matching score method (PSM-DID). Owing to the urban characteristic differences among the experimental and control groups in the ECCDZ, we selected enterprise size (Size), asset–liability ratio (Lev), return on equity (ROE), total asset turnover (ATO), quick ratio (Quick), management age (TMTAge), and management compensation (TMTPay) as matching variables using radius–kernel matching. The matched samples were computed by regression. Table 6 [columns (1) and (2)] presents the regression results after PSM. The findings revealed that the ECCDZ establishment continues to exert a significant negative impact on labor employment, indicating that the sample selection does not undermine the robustness and significance of the regression results.

Alter the dependent variable. We further used the growth rate of enterprise labor employment as an alternative dependent variable in the regression analysis. Table 6 [columns (3)] shows that the coefficients decrease in magnitude when these variables replace the original ones. The observed reduction in the coefficient’s magnitude is an artifact of metric rescaling, not an indication of a weaker economic effect. By substituting percentage-based growth rates for absolute employment levels, the coefficient’s scale is mathematically compressed. Despite this numerical compression, the coefficient remains highly statistically significant (p < 0.01), confirming that the underlying economic relationship is robust. This finding confirms strong robustness in the regression findings.

Change observation period. After excluding the effect of the pandemic, the regression results in Table 6 [columns (4)] suggest that the ECCDZ (Treat × Post) remains markedly negatively correlated with enterprise labor employment. Notably, this emphasizes the robustness of the regression results.

4.3 Analysis of Influence Mechanism

Our theoretical framework posits that the ECCDZ policy primarily inhibits employment through two channels: an environmental cost channel and a production scale channel. Specifically, we hypothesized that the ECCDZ designation (1) increases firms’ environmental compliance costs and (2) reduces their scale of production, both of which lead to a decline in labor demand. To empirically test these mechanisms, we conducted the following analyses.

4.3.1 Environmental Cost Mechanism

To test the hypothesis that the ECCDZ policy affects employment by increasing firms’ environmental costs, we examine two specific measures of these costs: green innovation and environmental protection investment. We treat these as mediating variables in our analysis. Green innovation captures a firm’s proactive response to environmental pressure. Through technological breakthroughs, firms can reduce pollutant generation at the source, thereby lowering the need for end-of-pipe treatments. Such innovation allows firms not only to mitigate long-term environmental costs arising from sewage charges, fines, and waste disposal, but also to generate new value through energy conservation, reduced consumption, and green product premiums (Hao et al., 2023; Kang & Shang, 2025).

Environmental protection investment represents a firm’s direct compliance expenditures. This includes capital spent to meet environmental laws and regulations, primarily for end-of-pipe pollution control and ecological restoration. These investments are a direct manifestation of the costs imposed by regulation, aimed at either meeting compliance targets or mitigating losses from environmental damages (Guo et al., 2025).

Of these, Green Innovation Application is measured by logarithmically transforming the count of green patent applications by the listed companies plus 1, which is attained from the National Bureau of Statistics and CSMAR database. In addition, Environmental Protection Investment is measured as the ratio of environmental protection expenditures to total operating income, with data hand-collected from firms’ annual reports. Table 7 presents the regression results. Per the test results of environmental costs, the Treat × Post coefficients in Table 7 [columns (1) and (3)] are 0.051 and 0.007, respectively (p < 0.05). This confirms that the ECCDZ designation significantly increases firms’ environmental costs. Moreover, the coefficients of Green Innovation Application and Environmental Protection Investment in Table 7 [columns (2) and (4)] are −0.023 and −0.365, respectively (p < 0.05), indicating that higher environmental costs are, in turn, associated with lower employment. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence for the environmental cost channel: the ECCDZ policy increases firms’ environmental costs, which then leads to a reduction in labor demand. This likely occurs because rising compliance costs erode profits and crowd out productive reinvestment. Therefore, H2 is supported.

Environmental cost mechanism

| Variables | Green innovation application | Labor | Environmental protection investment | Labor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treat × Post | 0.051*** | 0.007*** | ||

| (2.982) | (3.130) | |||

| Green innovation application | −0.023** | |||

| (−2.476) | ||||

| Environmental protection investment | −0.365*** | |||

| (−4.907) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant terms | −0.292 | −9.973*** | 0.877*** | −9.813*** |

| (−0.228) | (−7.741) | (3.421) | (−7.609) | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 38,738 | 38,738 | 33,797 | 33,797 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.174 | 0.746 | 0.518 | 0.745 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

4.3.2 Production Scale Mechanism

To test the hypothesis that the ECCDZ policy affects employment by altering firms’ production scale, we use two proxy variables for production scale: Operating revenues and Inventory additions. Both variables are measured in natural logarithms, and the data were collected from the CSMAR database. The regression results are presented in Table 8. Based on the test results related to the ECCDZ production scale, the Treat × Post coefficients in Table 8 [columns (1) and (3)] are −0.029 and −0.044, respectively (p < 0.05). This confirms that the ECCDZ designation leads to a significant contraction in firms’ scale of production. Meanwhile, the coefficients of Operating revenues and Inventory additions in Table 8 [columns (2) and (4)] are 0.800 and 0.042, respectively (p < 0.05), which indicates that a larger production scale is, as expected, associated with higher employment. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence for the production scale channel: the ECCDZ policy reduces firms’ scale of operations, which in turn leads to a decrease in their demand for labor. Therefore, H3 is supported.

Production scale mechanism

| Variables | Operating revenues | Labor | Inventory additions | Labor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treat × Post | −0.029*** | −0.044** | ||

| (−4.773) | (−2.153) | |||

| Operating revenues | 0.800*** | |||

| (27.308) | ||||

| Inventory additions | 0.042*** | |||

| (3.386) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant terms | −1.640*** | −8.615*** | −1.247 | −10.143*** |

| (−2.820) | (−6.905) | (−0.644) | (−7.918) | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 38,762 | 38,762 | 38,335 | 38,335 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.965 | 0.777 | 0.724 | 0.751 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

The observed dual-channel pressure on labor is driven by regulatory pressure from the EDCCZ. The first channel involves rising environmental costs, which divert capital from payrolls. These costs are manifested through compulsory green innovation (Green Innovation Application, +0.051) and mandatory compliance investments (Environmental Protection Investment, +0.007). The second channel is a declining production scale, which stems from resource reallocation toward ecological compliance and demand uncertainty mitigation. This decline is reflected in output contraction (Operating revenues, −0.029) and inventory rationalization (Inventory additions, −0.044). The disparity in the magnitude of these effects arises from differential adjustment rigidities. Green innovation, represented by patent applications, imposes immediate sunk R&D costs with irreversible labor trade-offs, whereas environmental investments permit phased expenditure smoothing. Similarly, on the production side, inventory adjustments represent operational flexibility rather than permanent workforce reduction, while revenue declines can be buffered by productivity gains. This asymmetry underscores that regulatory-driven technological shifts incur sharper short-term employment costs than market-mediated production scaling during ecological transitions.

4.4 Heterogeneity Analysis

While our baseline results confirm an average negative effect of the ECCDZ policy on employment, this effect may not be uniform across all types of firms. Theory suggests that the impact of environmental regulation could vary depending on firm characteristics and the external environment. Therefore, we conduct a heterogeneity analysis to explore how the policy’s employment effect differs across four key dimensions: firm size, ESG rating, factor intensity, and the stringency of external environmental supervision.

4.4.1 Heterogeneity by Enterprise Size

We first examine whether the employment effect of the ECCDZ policy varies with firm size. Larger firms typically have a larger production scale and may face greater environmental compliance costs (Li & Sheng, 2018; Zheng & Wang, 2012). Consequently, we expect the negative employment effect to be more pronounced for larger firms.

To test this, we split our sample into two sub-groups based on the median of firm size: large firms and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). We then perform separate regressions for each group. The results, presented in Table 8 [columns (1) and (2)], show a stark contrast. For large firms, the coefficient of Treat × Post is −0.137 and is statistically significant at the 1% level. For SMEs, the coefficient is negative but statistically insignificant. This finding indicates that the adverse employment effect of the ECCDZ policy is concentrated among large firms. The magnitude of this effect is also economically significant: the decline in labor force size reached 10.2–15.6% for large enterprises, whereas SMEs registered a much smaller reduction of 5.3–7.1%. A plausible explanation for this divergence is that large firms, being more visible, face stricter regulatory scrutiny. This pressure may compel them to undertake more drastic measures, such as shutting down polluting production lines or making significant technological upgrades, which disproportionately affect low-skilled positions.

4.4.2 Heterogeneity by ESG Rating

Next, we investigate how the policy’s employment effect varies with a firm’s ESG performance. A high ESG rating can be advantageous, potentially leading to a larger production scale and higher employment (Mao & Wang, 2023). However, high-ESG firms might also be more sensitive to environmental pressures and invest more heavily in compliance (Tang et al., 2023). This creates ambiguity regarding how ESG performance will moderate the policy’s impact. We hypothesize that the negative effect will be stronger for low-ESG firms, as they likely face greater pressure to adapt.

To test this, we partition the sample into high- and low-ESG groups based on the median ESG rating and conduct separate regressions. The results in Table 9 [columns (3) and (4)] reveal that the coefficient on Treat × Post is negative and statistically significant only for the low-ESG group. This indicates that the adverse employment effect of the ECCDZ policy is primarily concentrated in firms with poor ESG performance. In terms of magnitude, firms with low ESG ratings exhibited a 6.3 percentage point lower employment growth compared to their high-ESG counterparts. This finding offers a nuanced contribution to the literature. While the stronger inhibitory effect on low-ESG firms aligns with the production scalability mechanism of Mao and Wang (2023), it challenges the environmental burden hypothesis of Tang et al. (2023). Our results suggest that a firm’s green reputation, proxied by its ESG rating, acts as a crucial buffer. High-ESG firms may be better able to attract investment and other resources, allowing them to offset regulatory costs without downsizing their workforce. Conversely, low-ESG firms are compelled to internalize these costs primarily through channels like workforce reduction. This highlights investment attraction as a critical, yet underexplored, mediator in the relationship between ESG performance and employment outcomes under environmental regulation.

Heterogeneity in enterprise size, ESG rating, and factor intensity

| Variables | Enterprise size | ESG rating | Factor intensity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large enterprises | Small- and medium-sized enterprises | High | Low | Technology-intensive | Labor-intensive | Capital-intensive | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Treat × Post | −0.137*** | −0.027 | −0.025 | −0.165*** | −0.010 | −0.118*** | −0.096*** |

| (−6.454) | (−1.269) | (−1.249) | (−8.085) | (−0.497) | (−4.129) | (−2.790) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant terms | −10.675*** | −10.962*** | −10.718*** | −8.520*** | −9.151*** | −7.472*** | −11.030*** |

| (−6.005) | (−5.249) | (−5.469) | (−5.063) | (−4.573) | (−3.251) | (−5.111) | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 21,903 | 16,859 | 21,209 | 17,555 | 18,020 | 13,633 | 7,107 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.683 | 0.714 | 0.779 | 0.701 | 0.744 | 0.733 | 0.835 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

4.4.3 Heterogeneity by Factor Intensity

The impact of the ECCDZ policy is also likely to vary by an industry’s factor intensity. Labor-intensive industries may be particularly vulnerable as they might respond to rising environmental costs by cutting labor costs (Li et al., 2021b). Capital-intensive industries require significant capital investment, which may be crowded out by environmental expenditures. In contrast, technology-intensive industries, characterized by lower pollution and higher output, may be less affected (Wang et al., 2015).

To test these propositions, we classify our sample firms into three categories – labor-intensive, capital-intensive, and technology-intensive – based on the National Economic Industry Classification (GB/T4754-2017) and the standards set by Yang et al. (2014). We then conduct separate regressions for each group. The results are presented in Table 9. We find a significant negative employment effect in both labor-intensive and capital-intensive industries. For labor-intensive firms (e.g., textiles, food processing), the ECCDZ designation is associated with an 8.7–12.3% decline in workforce size. This is likely because investments in environmental equipment crowd out human resource budgets and force a reduction in production scale, with low-skilled positions accounting for 72% of the total job losses. For capital-intensive firms, the policy appears to accelerate labor substitution. As capital is reallocated toward environmental protection, these firms see a 10.4% decrease in general labor demand, driven by automation upgrades that are spurred by green investments.

In stark contrast, technology-intensive firms (e.g., IT, biopharmaceuticals) exhibit no statistically significant change in employment. This result is consistent with our theoretical expectations, as these firms’ lower pollution intensity and greater technological flexibility likely allow them to adapt to green transitions with minimal disruption to their workforce.

4.4.4 Heterogeneity by External Environment Supervision

External environmental supervision can invigorate the implementation of environmental protection policies and incentivize firms to exhibit positive environmental behavior. Precisely, external environmental supervision can apply public opinion pressure, increase the information exchange between the government and enterprises, reinforce the execution of policies, and enhance environmental regulation. Conversely, a lack of external environmental information encourages enterprises to reduce investment in environmental protection governance and upgrade their production technology in their original investment plans. Thus, the impact of demonstration zones on enterprise labor employment might vary under diverse external environment supervision forces. Furthermore, the establishment of demonstration zones is more inhibitory to enterprise labor employment under robust external supervision and, contrariwise, less inhibitory under lenient external supervision. To validate the abovementioned theoretical hypotheses, we measured external environmental supervision through two indicators – public attention and media attention.

Public attention. Amid increasing public awareness of environmental protection, the government and the public alike attach more importance to environmental goals. Authorities actively take measures to actively advocate and guide the public to express their concerns and demands on environmental issues in a reasonable and legal way, so as to avoid the occurrence of major environmental pollution incidents or environmental mass incidents (Ouadghiri et al., 2021). Following Wang et al. (2015), we used the annual search index of Baidu for the keyword “environmental pollution” to measure public concern. Then, subgroup regressions were performed by dividing the sample into high public attention and low public attention per the median of the annual search index. Table 10 [columns (1) and (2)] shows that the coefficient of Treat × Post is −0.209 (p < 0.01) for high public attention, while it is insignificant for low public attention. This finding indicates that high public attention can enhance the effect of policy implementation and decrease information irregularity during policy implementation. Enterprises with high public attention incurred environmental compliance costs amounting to 5.8% of their revenue, resulting in a 7.9% short-term reduction in workforce size. Conversely, firms with low public attention avoided such costs through greenwashing practices, limiting their employment decline to merely 2.3%. This confirms that informal environmental regulation, as captured by public attention, can significantly amplify the policy’s adverse effect on employment (Wu et al., 2022).

Heterogeneity of the external environment supervises

| Variables | High public attention | Low public attention | High media attention | Low media attention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treat × Post | −0.209*** | −0.014 | −0.221*** | −0.024 |

| (−9.940) | (−0.768) | (−10.047) | (−1.179) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant terms | −8.748*** | −11.950*** | −7.963*** | −8.769*** |

| (−5.545) | (−5.586) | (−5.029) | (−4.216) | |

| Industry fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 17,410 | 21,353 | 17,903 | 20,859 |

| Adj. R 2 | 0.757 | 0.723 | 0.736 | 0.741 |

Note: ***, **, and * represent significance levels of 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. The t-value in parentheses is calculated using the clustering robust standard error adjusted at the firm level.

Media attention. Based on signal transmission theory, the media is the key external supervision force, which can exert pressure on enterprises through stakeholders, effectively restrain enterprise behavior through the media’s strong public opinion guidance ability, and use the reputation mechanism and administrative governance means (Tavakolifar et al., 2021). Following Yu et al. (2022), we used the overall number of negative news reports of enterprises in online news headlines in 1 year to measure the media attention of enterprises. The analysis was processed by adding 1 and taking the natural logarithm, and the news data were obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services. Then, subgroup regressions were performed by categorizing the sample into high-media-attention and low-media-attention groups based on the median. Table 10 [columns (3) and (4)] shows that the coefficient of Treat × Post is −0.221 for high media attention (p < 0.01), whereas it is insignificant for low media attention. Enterprises with high media attention experienced an 11.2% reduction in workforce size, significantly higher than the 4.5% decline observed in low-attention firms. This disparity primarily stems from media exposure amplifying environmental compliance risks. This result indicates that intense media scrutiny amplifies the pressure of environmental compliance, thereby reinforcing the negative employment impact of the ECCDZ policy.

4.5 Discussion of Findings

Understanding the relationship between China’s ECCDZ policy and firm-level employment is critical for achieving the dual objectives of ecological progress and economic stability. Using the staggered rollout of ECCDZs as a quasi-natural experiment, this study employed a DID approach on a panel of listed Chinese firms from 2012 to 2023 to investigate this relationship. Our findings consistently show that the ECCDZ designation has a significant negative impact on firm-level employment. The mechanism analysis confirms that this effect operates through two primary channels: a contraction in production scale and an increase in environmental compliance costs. Furthermore, the heterogeneity analysis reveals that this adverse employment effect is not uniform. The impact is significantly more pronounced for large firms, those in labor- and capital-intensive industries, firms with poor ESG ratings, and those operating under intense external environmental supervision (i.e., high public and media attention). Conversely, the employment effect is statistically insignificant for technology-intensive firms and those under low external scrutiny. In sum, this research provides a multi-dimensional analysis of how firms respond to a major place-based environmental policy. Our findings are crucial for policymakers seeking to strike a sustainable balance between ecological governance and employment stability during the ongoing process of building an ecological civilization.

5 Conclusion and Future Work

5.1 Conclusions

Using a staggered DID approach and firm-level panel data from 2012 to 2023, this study provides robust evidence that the designation of an ECCDZ leads to a significant reduction in firm-level employment. This main finding is validated through a series of rigorous robustness checks, including a parallel trend test, a placebo test, heterogeneity-robust DID estimators, and endogeneity analyses, and PSM-DID. The heterogeneity analysis further reveals that this adverse employment effect is not uniform. The negative impact is significantly more pronounced for large firms, those with poor ESG performance, firms in labor- and capital-intensive industries, and those operating under intense external environmental supervision. In contrast, the employment effect is statistically insignificant for technology-intensive firms and those under low external scrutiny.

Furthermore, we identify two primary mechanisms driving this result. The ECCDZ policy inhibits employment by (1) increasing firms’ environmental compliance costs, which crowds out productive investment and (2) reducing firms’ scale of production, which directly lowers their demand for labor.

5.2 Implications and Recommendations

5.2.1 Theoretical Implications

This study offers several contributions to the literature on environmental and labor economics. First, our research provides direct, quasi-experimental evidence of the adverse employment effects of a place-based green policy in a major developing economy. By identifying the environmental cost and production scale channels, we offer a clear mechanistic framework for understanding the trade-offs between ecological governance and labor market outcomes. This framework is particularly relevant for the Asia-Pacific region and other emerging economies navigating similar green transitions.

Second, our findings on heterogeneity advance the understanding of how firm characteristics mediate the impact of environmental regulation. We demonstrate that the negative employment shock is disproportionately borne by large, labor-intensive, and capital-intensive firms. This moves beyond a monolithic view of policy impacts and provides a more nuanced theoretical basis for analyzing the distributional consequences of environmental policies across different segments of the corporate sector.

Finally, this study highlights the crucial role of informal institutions in shaping policy outcomes. We show that external monitoring from the public and the media significantly amplifies the negative employment effect of the ECCDZ policy. This finding contributes to the broader literature on corporate governance and policy implementation by demonstrating that social supervision and public participation act as powerful moderating forces that can alter the real effects of formal government regulation.

5.2.2 Practical Implications

First, policymakers should adopt differentiated and targeted policy designs. Our heterogeneity analysis shows that the adverse employment effects of the ECCDZ policy are concentrated among specific types of firms, such as large, labor-intensive, and low-ESG companies, while technology-intensive firms remain largely unaffected. Therefore, a one-size-fits-all approach is suboptimal. We recommend establishing a classification-based support framework. By identifying firms based on their size, factor intensity, and ESG performance, policymakers can tailor interventions – such as providing incentives for technological upgrading or tax credits for green innovation – to mitigate these negative employment shocks. For example, drawing on compliance cost theory, policymakers could grant companies within 5 years of establishment a 3-year transition period, during which 30% of environmental fines can be converted into technological transformation investments. For enterprises that employ more than 60% of the local labor force, their environmental performance rating could be automatically upgraded by one level. This targeted approach would help achieve environmental goals while optimizing the employment structure.

Second, governments should establish a coordinated labor transition mechanism to mitigate structural employment risks. Our mechanism analysis confirms that the ECCDZ policy reduces employment by altering firms’ production scale and cost structures, highlighting the need for proactive labor reallocation policies. It is critical to strengthen the coordination between environmental and employment agencies. On the one hand, firms should be encouraged to create new “green jobs” associated with environmental technologies. On the other hand, the government should lead reskilling and upskilling initiatives, creating training programs aligned with the needs of an expanding green economy. Educational institutions should also play a role by providing targeted skill training to the unemployed, enhancing their ability to transition smoothly to new roles. Such measures are essential for reducing frictional unemployment during the green transition and ensuring an efficient allocation of human capital.

Third, regulators must strengthen the multi-stakeholder oversight network to enhance policy effectiveness. Our finding that external supervision amplifies the policy’s effect underscores the importance of transparency and public participation. To combat information asymmetry, we recommend integrating institutional ratings, public engagement, and media oversight into a dynamic disclosure platform for corporate environmental performance. By mandating the disclosure of environmental data and linking preferential green finance policies to firms’ ESG ratings, a dual mechanism of “supervision and incentive” can be established. This would encourage firms to internalize environmental costs as a driver for innovation, rather than responding with simple labor downsizing.

5.3 Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that open avenues for future research. First, the micro-level mechanisms are insufficiently explored. Although our research confirmed that “production scale” and “environmental governance cost” are the main channels, there is a lack of in-depth characterization of the specific transmission paths and micro-level decision-making processes of these macro mechanisms within enterprises. Second, our research found that the policy’s inhibitory effect was more significant under stronger, not weaker, external supervision, which was attributed to the reduction of information asymmetry and the incentives for enterprises’ environmental protection investment. However, our research has failed to conduct an in-depth analysis of the specific constituent elements of “effective external environment supervision,” their relative importance, or how they precisely affect the internal decision-making chain of enterprises, especially labor employment decisions.

Future research could more deeply explore the internal logic and sustainability of the “counter-trend” increase in employment observed in technology-intensive enterprises. Our research finds that labor employment in technology-intensive enterprises presents a result opposite to the main policy effect. Future studies could focus on such enterprises and conduct an in-depth analysis of the specific job types where employment has increased, such as environmental protection technology research and development, or green production management. They could also analyze the core factors driving this “counter-trend” growth, such as policy subsidies, shifts in market demand, technological endowment advantages, or management strategies, as well as the sustainability of this growth model and its implications for the transformation of the overall employment structure. In addition, future work could explore the optimization of environmental supervision tool combinations and their differentiated guidance on enterprise behaviors. Based on the finding that “strong external supervision can amplify the inhibitory effect of policies,” one could investigate how these tools differentially influence the decisions of different types of enterprises in terms of environmental protection investment, technology route selection, and labor employment strategies. Furthermore, one could design and simulate the evaluation of the optimal combination of environmental supervision policies, with the aim of minimizing the unexpected impact on employment while achieving strict environmental goals, and even guiding enterprises towards green job creation.

-

Funding information: This research received funding by the following projects: National Social Science Foundation Project “Research on Heterogeneous Family Farm Entrepreneurship Resource Integration in the Context of Digitalization” (Project No.: 22BGL175); Heilongjiang Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Planning Key Think Tank Project “Key Issues and Practical Pathways of Ensuring Food Security Through New Agricultural Productive Forces in Heilongjiang Province” (Project No.: 24ZKT016); Heilongjiang Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Planning Project “Mechanism and Pathways of Digital Intelligence Empowering the Development of New Agricultural Productive Forces in Heilongjiang Province” (Project No.: 24GLC003).

-

Author contributions: All authors reviewed the manuscript. X.S. and J.F. wrote the main manuscript text. Y.W. collected the data and modified the article format together. F.S. supervised this work.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2013). The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. American Economic Review, 103(6), 2121–2168. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2121.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, A. C., Larcker, D. F., & Wang, C. C. Y. (2022). How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? Journal of Financial Economics, 144(2), 370–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2022.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

Bas, M., & Paunov, C. (2021). Input quality and skills are complementary and increase output quality: Causal evidence from Ecuador’s trade liberalization. Journal of Development Economics, 151, 102668. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102668.Search in Google Scholar

Beck, T., & Levkov, A. (2010). Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. Journal of Finance, 65(5), 1637–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01589.x.Search in Google Scholar

Berman, E., & Bui, L. T. M. (2001). Environmental regulation and productivity: Evidence from oil refineries. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), 498–510. doi: 10.1162/00346530152480144.Search in Google Scholar

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275. doi: 10.1162/003355304772839588.Search in Google Scholar

Bhuiyan, M. A., Jabeen, M., Zaman, K., Khan, A., Ahmad, J., & Hishan, S. S. (2018). The impact of climate change and energy resources on biodiversity loss: Evidence from a panel of selected Asian countries. Renewable Energy, 117, 324–340. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.10.054.Search in Google Scholar

Blanchard, O., & Giavazzi, F. (2003). Macroeconomic effects of regulation and deregulation in goods and labor markets. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 879–907. doi: 10.1162/00335530360698450.Search in Google Scholar

Callaway, B., & Sant’Anna, P. H. C. (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Z., Kahn, M. E., Liu, Y., & Wang, Z. (2018). The consequences of spatially differentiated water pollution regulation in China. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 88, 468–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2018.01.010.Search in Google Scholar

Cinelli, C., Ferwerda, J., & Hazlett, C. (2024). Sensemakr: Sensitivity analysis tools for OLS in R and Stata. Observational Studies, 10(2), 93–127. doi: 10.1353/obs.2024.a946583.Search in Google Scholar

Cui, G. H., & Jiang, Y. B. (2021). Do government environmental punishment affect labor demand of enterprises? China Population, Resources and Environment, 31(11), 78–88. [in Chinese].Search in Google Scholar

Curtis, E. M. (2018). Who loses under cap-and-trade programs? The labor market effects of the NOx budget trading program. Review of Economics and Statistics, 100(1), 151–166. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00680.Search in Google Scholar

Dang, J., Wang, J., & Tu, B. (2025). The impact of National Forest City Construction on local employment: Evidence from China. Forest Policy and Economics, 172, 103421. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2024.103421.Search in Google Scholar

Fankhauser, S., & Jotzo, F. (2018). Economic growth and development with low-carbon energy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(1), e495. doi: 10.1002/wcc.495.Search in Google Scholar

Feng, T., Du, H., Lin, Z., & Zuo, J. (2020). Spatial spillover effects of environmental regulations on air pollution: Evidence from urban agglomerations in China. Journal of Environmental Management, 272, 110998. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110998.Search in Google Scholar

Ferris, A. E., Shadbegian, R. J., & Wolverton, A. (2014). The effect of environmental regulation on power sector employment: Phase I of the Title IV SO2 trading program. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 1(4), 521–553. doi: 10.1086/679301.Search in Google Scholar

Ghaly, M., Dang, V. A., & Stathopoulos, K. (2020). Institutional investors’ horizons and corporate employment decisions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 64, 101634. doi: 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101634.Search in Google Scholar

Gray, W. B., Shadbegian, R. J., Wang, C., & Meral, M. (2014). Do EPA regulations affect labor demand? Evidence from the pulp and paper industry. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 68(1), 188–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2014.06.002.Search in Google Scholar

Grosset, F., Papp, A., & Taylor, C. (2023). Rain follows the forest: Land use policy, climate change, and adaptation (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4333147). Social Science Research Network. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4333147.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, X., Chen, S., & Liu, C. (2025). Business environment optimization effects on enterprise environmental protection investment. Finance Research Letters, 71, 106423. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.106423.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, M., Chen, K., & Pan, L. (2023). Attraction or repulsion? The creation of civilized cities and the resident intention of migrants. China Economic Review, 81, 102044. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2023.102044.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Q., & Xiong, W. (2023). How does the construction of ecological civilization pilot demonstration zones improve green development welfare? China Population, Resources and Environment, 33(7), 18–29. [in Chinese].Search in Google Scholar

Hao, X., Li, Y., Ren, S., Wu, H., & Hao, Y. (2023). The role of digitalization on green economic growth: Does industrial structure optimization and green innovation matter? Journal of Environmental Management, 325, 116504. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116504.Search in Google Scholar

He, G., Wang, S., & Zhang, B. (2020). Watering down environmental regulation in China. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(4), 2135–2185. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjaa024.Search in Google Scholar

Hille, E., & Möbius, P. (2019). Do energy prices affect employment? Decomposed international evidence. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 96, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2019.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Horbach, J., & Rennings, K. (2013). Environmental innovation and employment dynamics in different technology fields: An analysis based on the German community innovation survey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 57, 158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.034.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, X., & Lanz, B. (2018). The value of air quality in Chinese cities: Evidence from labor and property market outcomes. Environmental and Resource Economics, 71(4), 849–874.10.1007/s10640-017-0186-8Search in Google Scholar

Kahn, M. E., & Mansur, E. T. (2013). Do local energy prices and regulation affect the geographic concentration of employment? Journal of Public Economics, 101, 105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.03.002.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, S., & Shang, Y. (2025). Spatial-temporal coupling and industrial green growth effects of digital resources-industrial innovation-ecological environment: A case study from China. Journal of Environmental Management, 389, 126112. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126112.Search in Google Scholar

Laurila-Pant, M., Lehikoinen, A., Uusitalo, L., & Venesjärvi, R. (2015). How to value biodiversity in environmental management? Ecological Indicators, 55, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.02.034.Search in Google Scholar

Leblebicioğlu, A., & Weinberger, A. (2021). Openness and factor shares: Is globalization always bad for labor? Journal of International Economics, 128, 103406. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2020.103406.Search in Google Scholar

Li, L., & Hu, T. (2015). Evaluation of the construction level of ecological civilization pilot demonstration areas based on entropy weight TOPSIS method: A case study of Fuzhou City. Development Research, 10, 71–76. [in Chinese].Search in Google Scholar

Li, X., Liang, R., & Li, Y. (2022). Can big data tax enforcement restrain enterprises from “real to virtual economy”: Evidence from the quasi-natural experiment of the third phase of Golden Tax Project. Modern Finance and Economics, 42(7), 37–56. [in Chinese].Search in Google Scholar

Li, Z., & Lin, B. (2022). Analyzing the impact of environmental regulation on labor demand: A quasi-experiment from clean air action in China. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 93, 106721. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106721.Search in Google Scholar

Li, B., Liu, C., & Sun, S. (2021a). Do corporate income tax cuts decrease labor share? Regression discontinuity evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics, 150, 102541. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102624.Search in Google Scholar

Li, P., Lu, Y., & Wang, J. (2016). Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics, 123, 18–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.07.002.Search in Google Scholar