Diagnostic properties of natriuretic peptides and opportunities for personalized thresholds for detecting heart failure in primary care

-

Ralf E. Harskamp

, Lukas De Clercq

, Lieke Veelers

, Henk C.P.M. van Weert

, M. Louis Handoko

, Eric P. Moll van Charante

and Jelle C.L. Himmelreich

Abstract

Objectives

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent syndrome with considerable disease burden, healthcare utilization and costs. Timely diagnosis is essential to improve outcomes. This study aimed to compare the diagnostic performance of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) in detecting HF in primary care. Our second aim was to explore if personalized thresholds (using age, sex, or other readily available parameters) would further improve diagnostic accuracy over universal thresholds.

Methods

A retrospective study was performed among patients without prior HF who underwent natriuretic peptide (NP) testing in the Amsterdam General Practice Network between January 2011 and December 2021. HF incidence was based on registration out to 90 days after NP testing. Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated with AUROC, sensitivity and specificity based on guideline-recommended thresholds (125 ng/L for NT-proBNP and 35 ng/L for BNP). We used inverse probability of treatment weighting to adjust for confounding.

Results

A total of 15,234 patients underwent NP testing, 6,870 with BNP (4.5 % had HF), and 8,364 with NT-proBNP (5.7 % had HF). NT-proBNP was more accurate than BNP, with an AUROC of 89.9 % (95 % CI: 88.4–91.2) vs. 85.9 % (95 % CI 83.5–88.2), with higher sensitivity (95.3 vs. 89.7 %) and specificity (59.1 vs. 58.0 %). Differentiating NP cut-off by clinical variables modestly improved diagnostic accuracy for BNP and NT-proBNP compared with a universal threshold.

Conclusions

NT-proBNP outperforms BNP for detecting HF in primary care. Personalized instead of universal diagnostic thresholds led to modest improvement.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a syndrome that refers to the heart’s inability to pump blood effectively [1]. It can be caused by a structural and/or functional abnormality of the heart and has a multitude of possible aetiologies [2]. HF presents a significant health problem; the reported prevalence is 1.4 % in the community and outcomes are dire, with markedly reduced quality of life, frequent hospital visits and median survival of 5–7 years [3], [4], [5]. Awareness of the possibility of underlying HF among general practitioners (GPs) is of importance, as early detection provides the opportunity to alter the trajectory of underlying diseases, ultimately resulting in better outcomes and lower healthcare utilization. In the community, the gateway for testing for HF is by means of taking a blood sample to measure the concentration of natriuretic peptides, either B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP). Both are biomarkers that are excreted by cardiomyocytes in the ventricles in response to wall stress [6]. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) as well as Dutch GP guidelines for diagnosis of HF consider NT-proBNP and BNP as equivalent tests in this regard [1, 6], while they differ in physiological characteristics, as explained in detail in Supplementary Figure S1. The question is whether these two NPs are comparable in their diagnostic properties in community-based settings. Furthermore, while universal cut-off thresholds are recommended, studies suggest that making these threshold dependable on patient factors, such as age, sex, obesity and renal function, could help improve the diagnostic accuracy [7], [8], [9]. In this study we therefore set out to study: (a) the diagnostic accuracy of NT-proBNP compared to BNP in detecting HF in the community; and (b) whether the diagnostic accuracy of these natriuretic peptides can be improved by taking into account risk factors and NP altering factors.

Methods

This study was reported in accordance with the “Standards for Reporting Diagnostic accuracy studies” (STARD) guideline [10]. The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review, and our study complies with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki regarding ethical conduct of research involving human subjects.

Study design and patient population

We conducted a retrospective study making use of routine primary care data registrations collected by the Amsterdam General Practice Network, a collaboration between the Amsterdam University Medical Center and 117 general practices in the Amsterdam metropolitan area. The dataset is considered representative of the general population, since residents in the Netherlands are obligated to register to a GPs’ office for access to healthcare, and registration rates exceed 99 % of the population [11]. The data in the registry consists of structured (e.g., age, sex, diagnostic codes, medication codes and laboratory findings) and unstructured (e.g., free text within episode notations) data (also see Supplementary Table S1). Patient records are coded according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC). ICPC codes were used for registration of diseases, but also for the reason for encounter, for instance for symptoms like dyspnea, edema, fatigue. For the current study, we applied the following in- and exclusion criteria. Patients were included if they were: (1) at least 18 years of age; and (2) with a BNP or NT-proBNP measurement conducted between January 2011 and December 2021. We excluded patients if they had: (1) a diagnosis of HF at baseline; (2) a follow-up of <90 days after NP-measurement or; (3) if NP measurement results did not specify an associated measurement unit preventing us to determine the applicable diagnostic threshold. If there were records of multiple NP measurements per patient, only the first test was selected for the analyses. Supplementary Figure S2 displays the process.

Index test (assay)

The reported levels of BNP or NT-proBNP were collected and converted to the same measurement unit (ng/L). Tests had been performed in several local laboratories that used different assays e.g., Advia Centaur BNP assay (Bayer, Tarrytown, NY) and Elecsys® NT-proBNP assay (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). For our first analysis on diagnostic accuracy of NT-proBNP and BNP for HF, the standardized cut-off values we applied were <125 ng/L for NT-proBNP and <35 ng/L for BNP, as defined in the ESC-guidelines [1, 12]. For our second analysis on whether accuracy could be increased by the use of additional clinical variables, personalized thresholds were assessed. Further elaboration on the modeling of the personalized threshold can be found in the statistical analysis paragraph.

Clinical reference standard

Verification of HF diagnoses in the Amsterdam General Practice Network was described previously [13]. In short, the database was screened for HF diagnoses (up to 90 days after the natriuretic peptide test) by two researchers on ICPC-codes linked to HF (K77, K84.03) and subjected to a free text search for words suggesting HF in GP notes. An expert panel evaluated possible HF cases and subsequently determined and verified the diagnosis based on the three pillars, namely: symptoms suggestive of HF, observed findings with physical examination, and objective proof of structural or functional abnormality of the heart.

Factors considered for personalized thresholds

We performed a literature search to identify determinants that potentially affect NP values and/or increase the risk of HF. The determinant selection process can be found in Supplementary Tables S2–S4 [13–25].

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as numbers and percentages or median and 25th and 75th percentiles. Chi-squared test was used to determine statistical significance of differences in categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney-U test was used for continuous variables. To describe diagnostic accuracy we used specificity, sensitivity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) and calculated the area under the receiver-operator curve (AUROC) and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). The ROC curve is a well-known method to graphically show the relation between sensitivity and specificity. For the AUROC we consider a value of 0.7–0.8 as fair, 0.8–0.9 as good and above 0.9 as excellent. The lesser known area under the precision recall curve (AUPRC) shows the relation between the sensitivity (‘recall’) and PPV (‘precision’). When prevalence of disease is low the AUPRC is sometimes better suitable than AUROC to demonstrate difference in discrimination, as it more closely correlates with the PPV [26, 27]. However, AUPRC results are not as easily interpretable as they vary according to disease prevalence, with AUPRC tending to 0 with decreasing prevalence [26]. The baseline of the AUPRC is the prevalence of the disease within the analyzed population. As a consequence, thresholds for fair, good or excellent AUPRC are not determinable beforehand, and comparison of AUPRC results will be narratively described. Given that primary care research often operates in low-prevalence settings, we presented both the AUROC and AUPRC to provide additional context to our findings.

To correct for differences between the sample receiving a BNP test and the sample receiving a NT-proBNP test we implemented inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score [28]. The propensity score consisted of age, sex and the 10 previously selected clinical predictors (Supplementary Table S2). In this analysis, the “treatment” to “no treatment” comparison, as prescribed by IPTW, was filled in respectively by NT-proBNP as compared to BNP.

The second analysis consisted of assessing whether improvements in diagnostic accuracy could be made for BNP and NT-proBNP measurements. The sample was randomly divided in a test (20 %) and training set (80 %), stratified according to outcome (HF registration). The conventional ESC-defined cut-off values were compared to subgroup-specific cut-offs, in which the population was split according to age, sex and the selected covariables [13]. In determining the optimal cut-off for each NP for each group (presence or absence of each variable) sensitivity was set at that resulting from the ESC guidelines’ cut-off for each NP, with changes to the other diagnostic accuracy parameters determined by the newly differentiated NP thresholds. Significance at the 95 % level was established using p-values with correction for multiple hypotheses testing using the Bonferroni method [29]. Bootstrapping (1,000 times) was used to estimate the 95 % confidence intervals. For statistical analyses Python 3.7.11 was used with our statistical procedures making extensive use of the Scikit-learn library [30].

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified a total of 15,234 patients who underwent NP testing over the observed time period, of whom 8,365 with NT-proBNP and 6,873 with BNP. The baseline characteristics for both NPs stratified by HF are displayed in Table 1. Patients with HF were older, had more comorbidities, more often presented with dyspnea, and had higher NT-proBNP and BNP values compared with those without HF. When comparing the groups who underwent NT-proBNP testing vs. BNP testing, we found a higher percentage of HF at follow-up in patients who underwent NT-proBNP testing compared with those who underwent BNP-testing (5.7 vs. 4.5 %, p=0.002).

Characteristics of patients with a BNP or Nt-proBNP measurement, split by presence/absence of HF.

| Population with BNP test (n=6,873) | Population with NT-proBNP test (n=8,365) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF (n=311) | No HF (n=6,562) | p-Value | HF (n=473) | No HF (n=7,892) | p-Value | |

| Age, in years | 82.4 (75.3–87.9) | 68.6 (57.7–79.1) | <0.0001b | 81.7 (73.3–88.0) | 67.4 (56.5–77.3) | <0.0001b |

| Male sex | 46.6 % | 41.6 % | 0.088 | 45.5 % | 43.2 % | 0.36 |

|

|

||||||

| Prior medical history | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 17.7 % | 10.5 % | 0.0001b | 18.8 % | 10.5 % | <0.0001b |

| Atrial fibrillation | 34.1 % | 9.7 % | <0.0001b | 28.3 % | 8.5 % | <0.0001b |

| Valvular heart disease | 13.8 % | 5.6 % | <0.0001b | 12.5 % | 5.1 % | <0.0001b |

| Hypertension | 54.7 % | 46.6 % | 0.0062 | 56.5 % | 43.8 % | <0.0001b |

| COPD | 16.7 % | 14.3 % | 0.266 | 16.1 % | 11.7 % | 0.0057 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.2 % | 23.1 % | 0.0044 | 28.5 % | 20.0 % | <0.0001b |

| Chronic kidney disease | 24.4 % | 10.8 % | <0.0001b | 21.1 % | 9.5 % | <0.0001b |

| Obesity | 9.3 % | 13.9 % | 0.027 | 8.0 % | 11.2 % | 0.038 |

|

|

||||||

| Presenting symptoms a | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Dyspnea | 17.0 % | 12.6 % | 0.026 | 15.4 % | 9.6 % | 0.0001b |

| Edema | 13.2 % | 12.1 % | 0.63 | 12.5 % | 9.1 % | 0.019 |

| Fatigue | 4.8 % | 8.9 % | 0.017 | 4.0 % | 7.5 % | 0.006 |

| Other symptoms | 3.5 % | 6.7 % | 0.040 | 5.5 % | 8.3 % | 0.038 |

| BNP or NTproBNP, ng/L | 241 (106–567) | 28 (10–69) | <0.0001b | 1,361 (497–3,076) | 89 (50–229) | <0.0001b |

-

aRecorded symptoms leading up to a BNP or NT-proBNP test. Continuous variables are presented as median and 25–75th percentiles. Percentages are given to express prevalence of different patient characteristics within groups. Chi-squared test is used to determine statistical significance of differences seen between groups, for age and NPs the Mann-Whitney-U test is used. Results of both tests are expressed by a p-value, for which a score of <0.05 is considered significant. The Bonferonni correction is applied to adjust for testing of multiple hypotheses at once, when p-value remains statistically significant after correction this is indicated by superscript b.

NT-proBNP and BNP test characteristics

In patients in whom an NT-proBNP measurement was conducted, we found an (IPTW-adjusted) AUROC of 89.9 (95 % CI 88.4–91.2) for detecting HF. The AUPRC was 40.4 (95 % CI 35.6–45.0) When the ESC cut-off was applied, a sensitivity of 95.3 (95 % CI 93.0–97.1), a specificity of 59.1 (95 % CI 58.0–60.2), PPV of 12.6 (95 % CI 11.5–13.7) and NPV of 99.5 (95 % CI 99.3–99.7) were found.

In patients with a BNP measurement, an AUROC of 85.9 (95 % CI 83.5–88.2) was found. The AUPRC was 29.5 (95 % CI 25.0–34.8). When the ESC cut-off was applied a sensitivity of 89.7 (95 % CI 86.1–93.2), specificity of 58.0 (95 % CI 56.6–59.2), PPV of 8.9 (95 % CI 7.9–9.9) and NPV of 99.2 (95 % CI 98.9–99.5) were found.

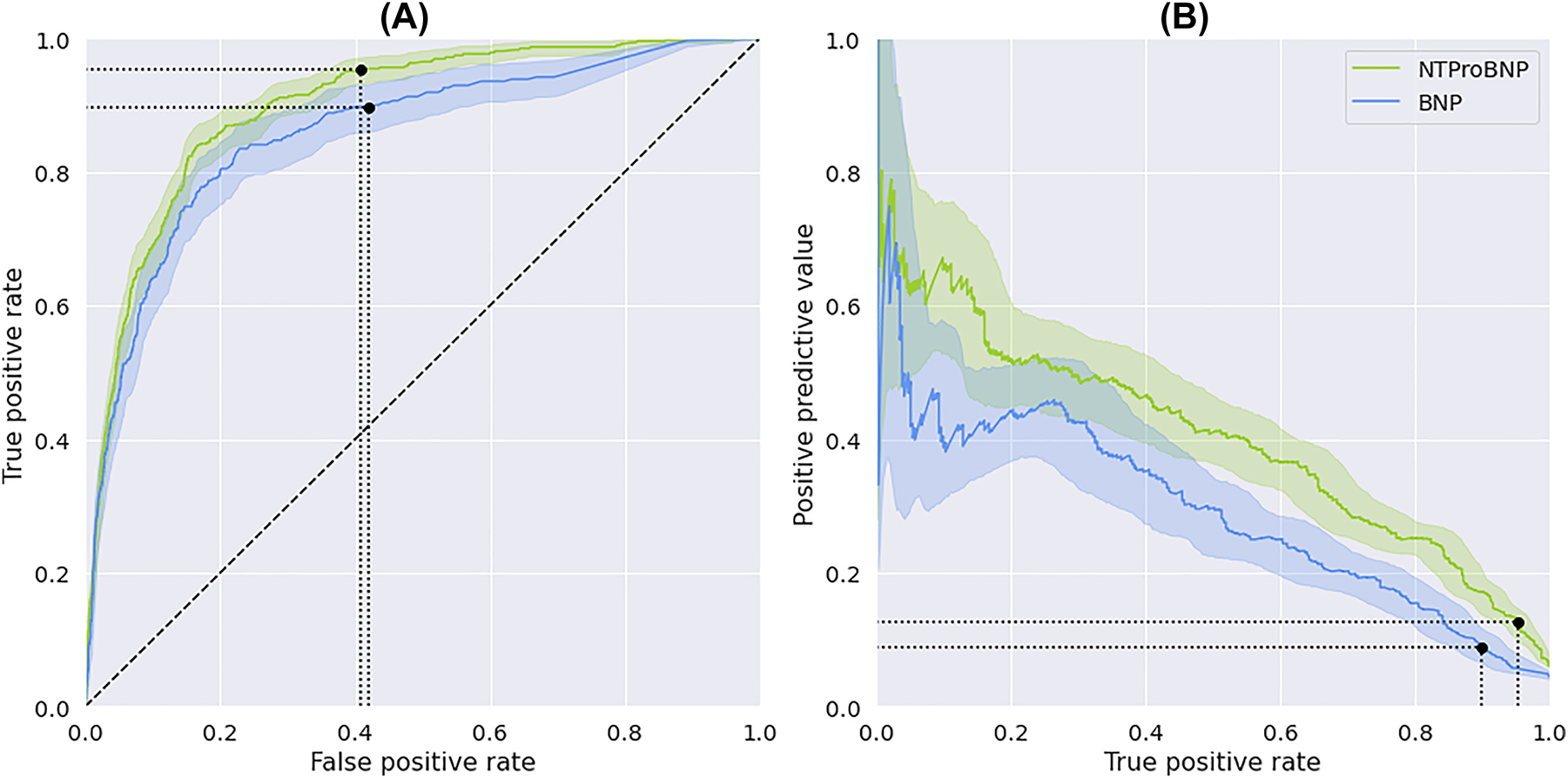

Figure 1 graphically displays the discriminatory properties of NT-proBNP in relation to BNP. After correcting for differences in baseline characteristics and HF prevalence, we found that NT-proBNP was associated with better discriminatory ability with a higher AUROC and AUPRC compared with BNP. Furthermore, the ESC cut-off for NT-proBNP performed better on sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV compared to BNP’s ESC cut-off (94.7 vs. 85.5 %, 60.6 vs. 56.3 %, 12.6 vs. 8.5 %, and 99.5 vs. 98.8 %, respectively; Supplementary Tables S5 and S6).

Discrimination of the natriuretic peptides (NT-proBNP and BNP). (A) AUROC and (B) AUPRC of NT-proBNP and BNP with 95 % confidence intervals. Blue for BNP and green for NT-proBNP. ESC-cut-off indicated by black dot on curve for both NPs.

Analyses of pre-specified diagnostic test modifiers

Table 2 and detailed Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 illustrate the optimal cut-off in the presence or absence of specific diagnostic test modifiers, and a comparison with the ESC cut-offs. All personalized thresholds for BNP and NT-proBNP resulted in modest increase in specificity and PPV compared to use of the uniform ESC cut-off alone, while sensitivity remained statistically unchanged. The number of patients who would have had a positive test result (and thus need for additional diagnostic evaluation) based on the differentiated cut-offs was lower for all tested variables (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6).

The test characteristics of optimized thresholds for individual variables compared with the reference diagnostic threshold as recommended by the ESC guidelines for NT-proBNP and BNP respectively.

| NP | Variable | Threshold | Sens | PPV | Spec | NPV | Positive test, n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable+ | Variable− | |||||||

| NT-proBNP | Guideline | <125 | <125 | 94.7 | 12.6 | 60.6 | 99.5 | 712 |

| Age>75 | 125 | 150 | +0.0 | +1.1 | +3.6 | +0.03 | −56 | |

| Male | 127 | 141 | +0.0 | +0.7 | +2.3 | +0.02 | −36 | |

| Obesity | 201 | 132 | +0.0 | +0.9 | +3.0 | +0.02 | −48 | |

| CKD | 139 | 136 | +0.0 | +0.8 | +2.7 | +0.02 | −42 | |

| HTN | 142 | 133 | +0.0 | +0.8 | +2.5 | +0.02 | −40 | |

| Prior MI | 176 | 131 | +0.0 | +0.6 | +2.2 | +0.02 | −34 | |

| AF | 132 | 133 | +0.0 | +0.5 | +1.8 | +0.01 | −28 | |

| VHD | 288 | 132 | −1.1 | +0.7 | +2.9 | −0.08 | −46 | |

| COPD | 138 | 141 | +0.0 | +1.1 | +3.5 | +0.03 | −55 | |

| BNP | Guideline | <35 | <35 | 85.5 | 8.5 | 56.3 | 98.8 | 626 |

| Age>75 | 29 | 72 | +0.0 | +2.4 | +10.5 | +0.19 | −138 | |

| Male | 36 | 53 | −1.6 | +1.6 | +8.2 | +0.03 | −108 | |

| Obesity | 46 | 44 | +0.0 | +1.4 | +6.9 | +0.13 | −90 | |

| CKD | 28 | 45 | +0.0 | +1.3 | +6.2 | +0.12 | −81 | |

| HTN | 38 | 55 | −1.6 | +1.4 | +7.4 | +0.02 | −98 | |

| Prior MI | 33 | 45 | +0.0 | +1.3 | +6.5 | +0.12 | −85 | |

| AF | 21 | 49 | +0.0 | +2.4 | +10.5 | +0.19 | −124 | |

| VHD | 65 | 42 | +0.0 | +1.5 | +7.0 | −0.13 | −92 | |

| COPD | 24 | 57 | −3.2 | +1.7 | +9.3 | −0.06 | −124 | |

-

AF, atrial fibrillation; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; NP, natriuretic peptide; NPV, negative predictive value; NT-proBNP, N-terminal proBNP; PPV, positive predictive value; VHD, valvular heart disease.

For NT-proBNP, most notable improvement was seen when differentiating for age (threshold of 125 for age >75 vs. 150 ng/L for age ≤75) and COPD (threshold of 138 when present vs. 141 ng/L when absent) which improved specificity by 3.5–3.6 %. For BNP, improvement was more substantial, with specificities improving by 8–11 % for age, male sex, AF and COPD (significant difference in differentiated thresholds after Bonferroni correction only for AF and COPD), and other tested variables in the range 6–8 %.

Discussion

Validation of BNP and NT-proBNP for incident HF up to 90 days after routine care NP testing in data from a Western European urban primary care population showed higher diagnostic accuracy for NT-proBNP over BNP. Differentiating diagnostic thresholds for both BNP and NT-proBNP resulted in clinically modest but statistically significant improvement in specificity and PPV, with equal sensitivity, with highest potential gains for BNP testing.

Comparison to previous work

BNP vs. NT-proBNP

The difference in diagnostic accuracy between BNP and NT-proBNP has been evaluated in previous studies, including multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses [12, 31–37]. There are a number of physiological and analytical characteristics that may explain differences in diagnostic accuracy between BNP and NT-proBNP. BNP is considered less stable than NT-proBNP, both during collection and preservation, and the biological variation of BNP (about 40–70 %) is significantly higher than that of NT-proBNP (20–50 %) [36]. Furthermore, the Reference Change Value and the index of individuality of BNP are higher than those of NT-proBNP. Accordingly, the clinical cut-off values of NT-proBNP are calculated more precisely with narrower confidence intervals compared to BNP. Also, overall NT-proBNP immunoassays show better analytical performances, i.e., analytical sensitivity and imprecision, when compared with BNP [33, 37]. Unfortunately, the underlying studies often had small populations and results are not unanimous. Consequently, depending on the evidence being used, HF guidelines differ in considering both NPs as equivalent or having a preference for NT-proBNP. The ESC for instance considers measurement of BNP and NT-proBNP comparable, whereas NICE advises measuring NT-proBNP [1, 12]. NICE based their decision on better results for sensitivity and the physiological differences that make NT-proBNP more suitable for primary care. Our comparison of both NPs agrees with these findings, showing a higher sensitivity for NT-proBNP.

Optimal cut-off of BNP and NT-proBNP

Multiple studies have attempted to find the best performing threshold of BNP and/or NT-proBNP to predict HF, the results of which have been summarized in at least two systematic reviews [12, 38]. Consensus has not been made by different guidelines on one superior threshold. Different cut-off splits have been proposed for variables with an influence on NP values. For instance, age-group dependent cut-offs for NT-proBNP performed better than a universal cut-off when grouped according to age (<50, 50–75 and >75 years) [39]. Our analyses also show that using risk factor dependent values for NPs could perhaps present a superior alternative compared to a single cut-point for ruling out suspected HF in primary care.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is the large dataset of patients with a high level of data granularity, resulting in a sizeable subset of suspected HF patients in whom NP testing had occurred. For our analyses on differentiated cut-offs, this provided sufficiently large subsets in whom to perform both training and internal validation analyses. The large coverage in terms of associated general practices as well as geographical spread resulted in a dataset representative of (semi)urban, multiethnic, older primary care patients in western Europe. Another strength was our use of thorough statistical modeling techniques to determine the best fitting methods of detecting HF by use of NPs. Lastly, in determining an HF diagnosis we did not base this merely on structured data but also on free text available in the dataset. This resulted in all potential HF cases (whether flagged through structured or free text data) having been adjudicated by an expert panel.

A limitation in our statistical analyses was that the index and the reference standard were likely not independent. A registered HF diagnosis, our reference standard for diagnostic accuracy of the tested NPs, is based on a number of factors including NP measurement – the index test. Ideally, the index test and reference standard would have been independently assessed to prevent a number of biases that are a common in using retrospective datasets [40, 41]. A considerable number of cases had to be excluded due to missing unit of NP measurement, with potential for selection bias in case that missingness were to have been associated with certain local laboratories (and hence place of patients’ residence).

Further limitations were that diagnostic concordance between both NPs is not perfect, in which it is possible to have an elevated BNP while NT-proBNP is normal and vice versa [42]. A difference between BNP and NT-proBNP in the likelihood of being diagnosed is created if GPs are influenced by NP values to refer for further diagnostics. In our presentation of the AUPRC to assess diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NT-proBNP we saw a significantly increased AUPRC for NT-proBNP. To what extent these results are influenced by the higher HF prevalence among the sample tested with NT-proBNP, however, is uncertain. Finally, due to the absence of ICPC subcodes for type of HF as well as limitations on data granularity within free text data, we were unable to systematically make a distinction between HF with preserved, midrange or reduced ejection fraction among incident HF cases. For this reason insight in results on applicability could not be provided divided for each HF phenotype. Although the distinction would have given more comprehension on the contents of the cohort, this should not have limited our analyses on HF incidence of any type.

Future research

Our study indicated higher diagnostic accuracy from NT-proBNP over BNP for incident HF in routine primary care. These results were derived using IPTW analyses to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics between BNP and NT-proBNP groups. However, IPTW modeling only corrects for determinants measured in our dataset. Randomized prospective studies, aimed at balancing measured and unmeasured confounders, would be better positioned to compare the clinical relevance of diagnosing HF with either BNP or NT-proBNP in primary care. Such studies would also ideally involve uniform diagnostic work-up and endpoint adjudication, which were unable to be retrieved from the current dataset. Other future work could further assess the clinical benefit of using differentiated thresholds for NP testing based on univariate risk assessment, or multivariate through models such as TARGET-HF [13].

Conclusions

Validation of natriuretic peptides as diagnostic tests for detecting heart failure in routine primary care showed a higher diagnostic accuracy for NT-proBNP compared with BNP. Moreover, we found that personalized instead of universal diagnostic thresholds led to modest improvement.

-

Research ethics: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Aggregate can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. McDonagh, TA, Metra, M, Adamo, M, Gardner, RS, Baumbach, A, Böhm, M, et al.. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Bragazzi, NL, Zhong, W, Shu, J, Abu Much, A, Lotan, D, Grupper, A, et al.. Burden of heart failure and underlying causes in 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021;28:1682–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwaa147.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. NIVEL. Jaarcijfers aandoeningen – Huisartsenregistraties. NIVEL Zorgregistraties Eerste Lijn; 2022. www.nivel.nl2022.Search in Google Scholar

4. Taylor, CJ, Ordóñez-Mena, JM, Roalfe, AK, Lay-Flurrie, S, Jones, NR, Marshall, T, et al.. Trends in survival after a diagnosis of heart failure in the United Kingdom 2000–2017: population based cohort study. BMJ 2019;364:l223. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l223.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Riedinger, MS, Dracup, KA, Brecht, ML, SOLVD Investigatos, Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Quality of life in women with heart failure, normative groups, and patients with other chronic conditions. Am J Crit Care 2002;11:211–9.Search in Google Scholar

6. De Boer, RA, Dieleman-Bij de Vaate, AJIL, Lambermon, HMM, Oud, M, Rutten, FH, Schaafstra, A, et al.. NHG-standaard Hartfalen (2021). Utrecht: Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap; 2021. https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/hartfalen.Search in Google Scholar

7. Madamanchi, C, Alhosaini, H, Sumida, A, Runge, MS. Obesity and natriuretic peptides, BNP and NT-proBNP: mechanisms and diagnostic implications for heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014;176:611–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Takase, H, Dohi, Y. Kidney function crucially affects B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), N-terminal proBNP and their relationship. Eur J Clin Invest 2014;44:303–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Keyzer, JM, Hoffmann, JJ, Ringoir, L, Nabbe, KC, Widdershoven, JW, Pop, VJ. Age- and gender-specific brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) reference ranges in primary care. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:1341–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2013-0791.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Bossuyt, PM, Reitsma, JB, Bruns, DE, Gatsonis, CA, Glasziou, PP, Irwig, L, et al.. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2015;351:h5527. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015151516.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Poortvliet, MC, Lamkaddem, M, Devillé, W. Niet op naam ingeschreven (NONI) bij de huisarts: Inventarisatie en gevolgen voor de ziekenfondsverzekerden. Utrecht: NIVEL; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

12. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guidline [NG106]. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106 Search in Google Scholar

13. De Clercq, L, Schut, MC, Bossuyt, PMM, van Weert, H, Handoko, ML, Harskamp, RE. TARGET-HF: developing a model for detecting incident heart failure among symptomatic patients in general practice using routine health care data. Fam Pract 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmac069.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Taylor, CJ, Roalfe, AK, Iles, R, Hobbs, FR, investigators, R, Barton, P, et al.. Primary care REFerral for EchocaRdiogram (REFER) in heart failure: a diagnostic accuracy study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e94–102. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16x688393.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Agarwal, SK, Chambless, LE, Ballantyne, CM, Astor, B, Bertoni, AG, Chang, PP, et al.. Prediction of incident heart failure in general practice: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:422–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.111.964841.Search in Google Scholar

16. Goyal, A, Norton, CR, Thomas, TN, Davis, RL, Butler, J, Ashok, V, et al.. Predictors of incident heart failure in a large insured population: a one million person-year follow-up study. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:698–705. https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.110.938175.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Weber, M, Hamm, C. Role of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and NT-proBNP in clinical routine. Heart 2006;92:843–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.071233.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Mueller, C, McDonald, K, de Boer, RA, Maisel, A, Cleland, JGF, Kozhuharov, N, et al.. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:715–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1494.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Redfield, MM, Rodeheffer, RJ, Jacobsen, SJ, Mahoney, DW, Bailey, KR, Burnett, JCJr. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: impact of age and gender. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:976–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02059-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Wang, TJ, Larson, MG, Levy, D, Benjamin, EJ, Leip, EP, Wilson, PW, et al.. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation 2004;109:594–600. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000112582.16683.ea.Search in Google Scholar

21. Richards, M, Di Somma, S, Mueller, C, Nowak, R, Peacock, WF, Ponikowski, P, et al.. Atrial fibrillation impairs the diagnostic performance of cardiac natriuretic peptides in dyspneic patients: results from the BACH study (Biomarkers in ACute Heart Failure). JACC Heart Fail 2013;1:192–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2013.02.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Rivera, M, Taléns-Visconti, R, Salvador, A, Bertomeu, V, Miró, V, García de Burgos, F, et al.. NT-proBNP levels and hypertension. Their importance in the diagnosis of heart failure. Rev Española Cardiol 2004;57:396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1885-5857(06)60170-9.Search in Google Scholar

23. Bergler-Klein, J, Gyöngyösi, M, Maurer, G. The role of biomarkers in valvular heart disease: focus on natriuretic peptides. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:1027–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2014.07.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Natriuretic Peptides Studies Collaboration. Natriuretic peptides and integrated risk assessment for cardiovascular disease: an individual-participant-data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:840–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(16)30196-6.Search in Google Scholar

25. Yang, H, Negishi, K, Otahal, P, Marwick, TH. Clinical prediction of incident heart failure risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2015;2:e000222. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2014-000222.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Ozenne, B, Subtil, F, Maucort-Boulch, D. The precision--recall curve overcame the optimism of the receiver operating characteristic curve in rare diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:855–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.02.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Nahm, FS. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J Anesthesiol 2022;75:25–36. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.21209.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Austin, PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Bonferroni, C. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilita. Firenze: Pubblicazioni del R Istituto Superiore di Scienze Economiche e Commericiali di Firenze; 1936, 8:3–62 pp.Search in Google Scholar

30. Pedregosa, F, Varoquaux, G, Gramfort, A, Michel, V, Thirion, B, Grisel, O, et al.. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res 2011;12:2825–30.Search in Google Scholar

31. Ewald, B, Ewald, D, Thakkinstian, A, Attia, J. Meta-analysis of B type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro B natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of clinical heart failure and population screening for left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Intern Med J 2008;38:101–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01454.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Balion, C, Santaguida, PL, Hill, S, Worster, A, McQueen, M, Oremus, M, et al.. Testing for BNP and NT-proBNP in the diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure. Evid Rep Technol Assess 2006;142:1–147.Search in Google Scholar

33. Clerico, A, Fontana, M, Zyw, L, Passino, C, Emdin, M. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and the N-terminal part of the propeptide of BNP immunoassays in chronic and acute heart failure: a systematic review. Clin Chem 2007;53:813–22. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2006.075713.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Booth, RA, Hill, SA, Don-Wauchope, A, Santaguida, PL, Oremus, M, McKelvie, R, et al.. Performance of BNP and NT-proBNP for diagnosis of heart failure in primary care patients: a systematic review. Heart Fail Rev 2014;19:439–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-014-9445-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ontario Health (Quality). Use of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) as diagnostic tests in adults with suspected heart failure: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2021;21:1–125.Search in Google Scholar

36. Clerico, A, Carlo Zucchelli, G, Pilo, A, Passino, C, Emdin, M. Clinical relevance of biological variation: the lesson of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and NT-proBNP assay. Clin Chem Lab Med 2006;44:366–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2006.063.Search in Google Scholar

37. Clerico, A, Franzini, M, Masotti, S, Prontera, C, Passino, C. State of the art of immunoassay methods for B-type natriuretic peptides: an update. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2015;52:56–69. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408363.2014.987720.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Mant, J, Doust, J, Roalfe, A, Barton, P, Cowie, MR, Glasziou, P, et al.. Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of diagnosis of heart failure, with modelling of implications of different diagnostic strategies in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1–207. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta13320.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Hildebrandt, P, Collinson, PO, Doughty, RN, Fuat, A, Gaze, DC, Gustafsson, F, et al.. Age-dependent values of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide are superior to a single cut-point for ruling out suspected systolic dysfunction in primary care†. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1881–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq163.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Cox, E, Martin, BC, Van Staa, T, Garbe, E, Siebert, U, Johnson, ML. Good research practices for comparative effectiveness research: approaches to mitigate bias and confounding in the design of nonrandomized studies of treatment effects using secondary data sources: the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Good Research Practices for Retrospective Database Analysis Task Force Report--part II. Value Health 2009;12:1053–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00601.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. O’Sullivan, JW, Banerjee, A, Heneghan, C, Pluddemann, A. Verification bias. BMJ Evid Based Med 2018;23:54–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-110919.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Farnsworth, CW, Bailey, AL, Jaffe, AS, Scott, MG. Diagnostic concordance between NT-proBNP and BNP for suspected heart failure. Clin Biochem 2018;59:50–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.07.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2023-0089).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Diagnostic errors in uncommon conditions: a systematic review of case reports of diagnostic errors

- Routine blood test markers for predicting liver disease post HBV infection: precision pathology and pattern recognition

- Opinion Papers

- The challenge of clinical reasoning in chronic multimorbidity: time and interactions in the Health Issues Network model

- The first diagnostic excellence conference in Japan

- Clouds across the new dawn for clinical, diagnostic and biological data: accelerating the development, delivery and uptake of personalized medicine

- Original Articles

- Towards diagnostic excellence on academic ward teams: building a conceptual model of team dynamics in the diagnostic process

- Error codes at autopsy to study potential biases in diagnostic error

- Multicenter evaluation of a method to identify delayed diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis and sepsis in administrative data

- Detection of fake papers in the era of artificial intelligence

- Is language an issue? Accuracy of the German computerized diagnostic decision support system ISABEL and cross-validation with the English counterpart

- The feasibility of a mystery case curriculum to enhance diagnostic reasoning skills among medical students: a process evaluation

- Internal medicine intern performance on the gastrointestinal physical exam

- Scaling up a diagnostic pause at the ICU-to-ward transition: an exploration of barriers and facilitators to implementation of the ICU-PAUSE handoff tool

- Learned cautions regarding antibody testing in mast cell activation syndrome

- Diagnostic properties of natriuretic peptides and opportunities for personalized thresholds for detecting heart failure in primary care

- Incomplete filling of spray-dried K2EDTA evacuated blood tubes: impact on measuring routine hematological parameters on Sysmex XN-10

- Letters to the Editor

- The diagnostic accuracy of AI-based predatory journal detectors: an analogy to diagnosis

- Explainable AI for gut microbiome-based diagnostics: colorectal cancer as a case study

- Restless X syndrome: a new diagnostic family of nocturnal, restless, abnormal sensations of various body parts

- Erratum

- Retraction of: Establishing a stable platform for the measurement of blood endotoxin levels in the dialysis population

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Diagnostic errors in uncommon conditions: a systematic review of case reports of diagnostic errors

- Routine blood test markers for predicting liver disease post HBV infection: precision pathology and pattern recognition

- Opinion Papers

- The challenge of clinical reasoning in chronic multimorbidity: time and interactions in the Health Issues Network model

- The first diagnostic excellence conference in Japan

- Clouds across the new dawn for clinical, diagnostic and biological data: accelerating the development, delivery and uptake of personalized medicine

- Original Articles

- Towards diagnostic excellence on academic ward teams: building a conceptual model of team dynamics in the diagnostic process

- Error codes at autopsy to study potential biases in diagnostic error

- Multicenter evaluation of a method to identify delayed diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis and sepsis in administrative data

- Detection of fake papers in the era of artificial intelligence

- Is language an issue? Accuracy of the German computerized diagnostic decision support system ISABEL and cross-validation with the English counterpart

- The feasibility of a mystery case curriculum to enhance diagnostic reasoning skills among medical students: a process evaluation

- Internal medicine intern performance on the gastrointestinal physical exam

- Scaling up a diagnostic pause at the ICU-to-ward transition: an exploration of barriers and facilitators to implementation of the ICU-PAUSE handoff tool

- Learned cautions regarding antibody testing in mast cell activation syndrome

- Diagnostic properties of natriuretic peptides and opportunities for personalized thresholds for detecting heart failure in primary care

- Incomplete filling of spray-dried K2EDTA evacuated blood tubes: impact on measuring routine hematological parameters on Sysmex XN-10

- Letters to the Editor

- The diagnostic accuracy of AI-based predatory journal detectors: an analogy to diagnosis

- Explainable AI for gut microbiome-based diagnostics: colorectal cancer as a case study

- Restless X syndrome: a new diagnostic family of nocturnal, restless, abnormal sensations of various body parts

- Erratum

- Retraction of: Establishing a stable platform for the measurement of blood endotoxin levels in the dialysis population