Abstract

Perceptual errors are common contributors to missed diagnoses in the clinical practice of radiology. While the physical attributes of an image such as image resolution, signal-to-noise characteristics, and anatomic complexity are major causes of poor conspicuity of pathologic lesions, there are major interrelated cognitive contributors to visual errors. The first is satisfaction of search (SOS), where the detection of an abnormality results in premature termination of further search. Another form of incomplete search pattern is visual isolation, where a radiologist’s search pattern is truncated to the main areas of an image, while little or no attention is given to peripheral areas. A second cognitive error is inattentional blindness, defined as the failure to notice a fully visible, but unexpected object because attention was otherwise engaged. Strategies for error mitigation have centered around the use of check lists, self prompting routines, and structured reporting within an institutional culture of safety and vigilance.

Introduction

Perceptual errors account for 48%–80% of all diagnostic radiology errors reported in the literature [1], [2]. While the underlying reasons for perceptual errors are not well understood, there is considerable evidence that argues strongly against the concept that visual errors are the result of carelessness, sloppiness or negligence on the part of radiologists [3].

In this review, we will discuss factors that importantly contribute to perceptual errors in radiology, and show examples of these errors encountered in a large academic pediatric radiology practice. This material is based on more than 477,000 clinical cases reviewed in our department as part of an ongoing quality assurance process in place since 2003. During that time, we identified a total of 11,346 discrepancies occurring between a radiology report and a retrospective review of the imaging study and patient outcomes (2.4% of reviewed cases). A detailed description of our case identification and categorization process has been published elsewhere [2]. For purposes of this review, we have defined perceptual errors as those primarily related to non-recognition of an imaging abnormality.

Medical image perception in a nutshell

Interpretation of medical images is a complex phenomenon that has been described as involving two interrelated processes of perception, where there is a unified awareness of the content of the image, and analysis, during which one determines the meaning of the perceived findings in the context of the medical problem at hand [4], [5]. Our understanding of how radiologists interpret images evolved from studies on the psychology of visual perception. Initially, the process was understood to be a sequence of “search and detect, recognize, and decide” [6]. More recent studies have turned this original model around, and suggest that an initial global impression plays a very important role in initiating image perception and directing focal search [7]. The process is now modeled as “detect and recognize, search, and decide”, relegating the search process to a later stage in perception [6]. After the most conspicuous lesions have been identified, a focal search-and-identify phase takes over [7].

In reality, the task of clinical radiology is much more complex. To see the diagnostic process in radiology as a dichotomous variable (target abnormality detected/target abnormality not detected) is to oversimplify the process. More than one abnormality might be present; each of the detected abnormalities may in turn represent an actionable item (e.g. cancer), or not (e.g. old inflammatory granuloma). In addition, the target abnormality is commonly embedded within complex or distorted anatomy, and there may be added distractors in the image, such as overlying medical devices, or digital annotations that increase the “noise” within which the target must be discerned [8], [9].

Cross-sectional imaging modalities, such as CT or MRI improve the visual conspicuity of target abnormalities by obtaining multiple thin slices through the body, thus removing a great deal of anatomic overlap. However, these modalities come at the cost of producing hundreds to thousands of images that the radiologist must review in order to render a complete examination of the anatomy in question.

A dual-process of decision-making is theorized to be active during radiologic interpretation. System I is quick, heuristic, highly automatic, and prototypical. It requires minimal effort, and is highly prone to bias and error. However, it is very efficient and frequently utilized. System II is slower, more analytical, deductive and rule-based. It requires effort, and is less prone to bias and error. The operating principle of the dual process theory is pattern recognition. Most diagnoses in radiology can be made rapidly and effortlessly (e.g. displaced femur fracture, or large Wilm’s tumor). When an immediate diagnosis cannot be made, then the radiologist switches to a more analytical, deliberate and deductive approach (e.g. search for pulmonary nodule). While radiologists can switch between these two modes, there is a tendency to revert to the state requiring the least cognitive effort [10], [11].

Classification of perceptual errors

Although some diagnoses may be missed because of the technical or physical limitations of the imaging modality, including image resolution, intrinsic or extrinsic contrast, and signal-to-noise ratio, most missed radiologic diagnoses are attributable to image interpretation errors by radiologists [3]. Using advanced eye-tracking techniques, Kundel et al. studied visual search patterns in radiologists and classified visual misses (false negative errors) into three categories based on visual dwell times [5], [7]. The first is the search error, in which the radiologist never fixates on the lesion, and does not appear to see it. The second is an error in recognition, where the radiologist fixates on a lesion, but does so for a period of time less than the threshold required for recognition of the finding as abnormal (0.48 s). The third and final type of error is a decision error where the radiologist fixates on the lesion for longer than the threshold time for recognition, but fails to recognize it as abnormal, or actively dismisses the finding.

Contributing factors to perceptual error

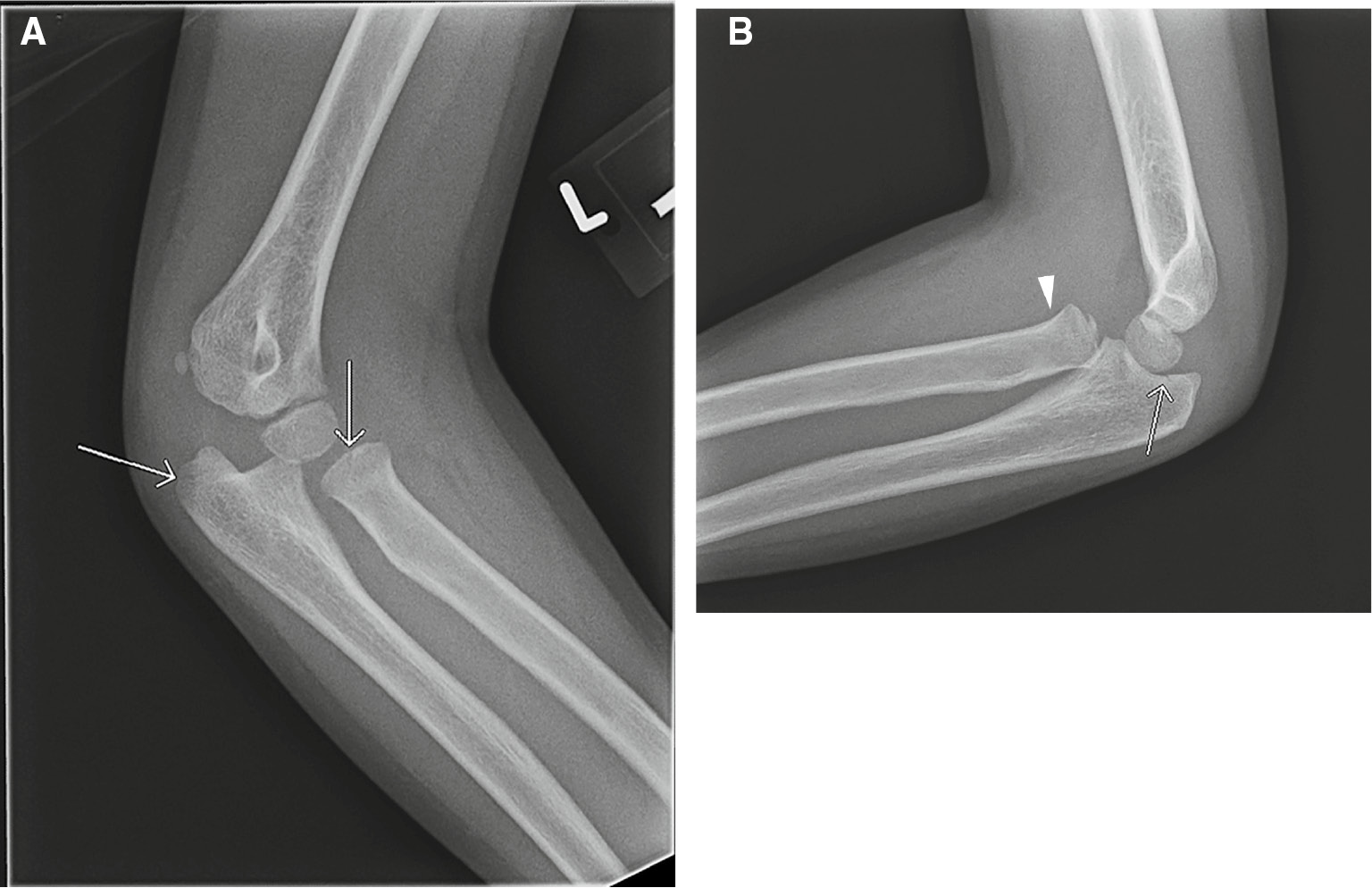

There are several inter-related factors that contribute to an incomplete evaluation of relevant image content in clinical practice, resulting in a missed or delayed diagnosis. Broadly, they are related to the radiologist’s search patterns, the radiologist’s pre-existing expectations, and human factors such as increasing clinical workload, fatigue, interruptions and distractions [3], [9], [12]. The most well-known is the phenomenon of satisfaction of search (SOS). It describes a situation during which the detection of an abnormality satisfies the search for meaning and results in premature termination of further search [13], [14]. In a seminal study in 1990, Berbaum et al. [15] showed that the addition of simulated pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs led to a significant reduction in the detection of native pulmonary nodules. SOS effects also lead to lower detection rates when multiple findings are present in clinical cases. Ashman et al. [16] showed that the detection rate for the first finding in bone radiography cases that contained multiple findings was about 78%, but detection of second and third findings decreased to approximately 40% (Figure 1). Subsequent experimental studies have shown that SOS effects appear to be the result of either a lack of visual inspection of other areas of the image, or a failure to recognize abnormalities where the image has been inspected [14], [17].

Satisfaction of search error.

A 7-year-old male with elbow pain and limited range of motion after fall. Two of the four X-rays obtained are shown. Subtle, nondisplaced fractures of the radial head and olecranon were identified on oblique (A) and lateral (B) radiographs (arrows). An anterior dislocation of the radial head (arrowhead) was missed.

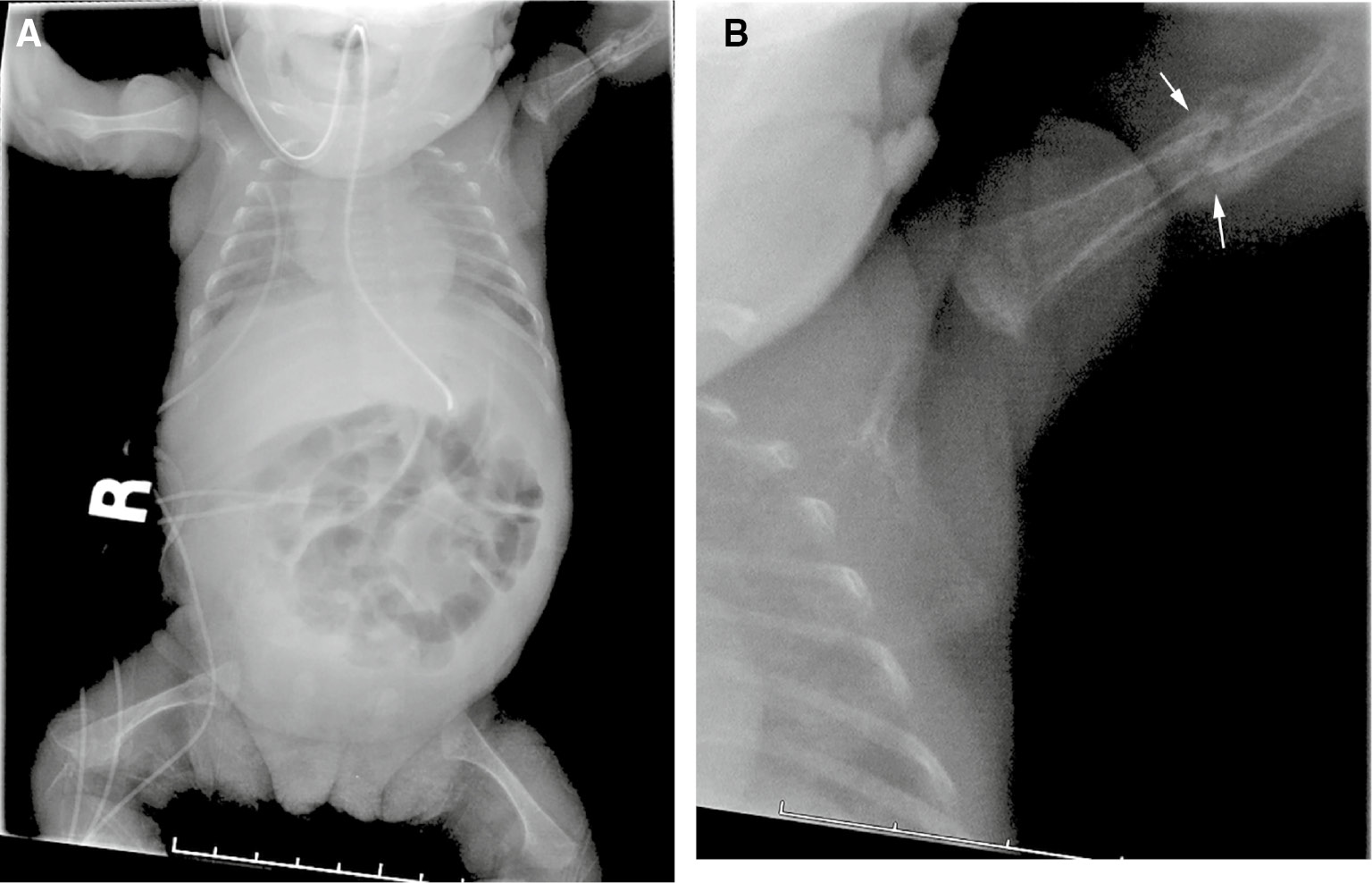

Another form of search satisfaction can be described as “visual isolation”, during which a radiologist’s search pattern is truncated to the main areas of an image, while little or no attention is given to peripheral areas [18]. A clinical example is shown in Figure 2. This chest radiograph was obtained to confirm feeding tube placement in a premature infant with chronic lung disease. Most of the radiologist’s attention is devoted to the location of the tube within the chest and abdomen, and an evaluation of pulmonary inflation and parenchymal opacities that might suggest the presence of atelectasis, pulmonary edema or infection. The evaluation of bony structures and the abdomen are relegated to a lower level of inspection, or ignored. A new left humeral fracture is visible in the periphery of the image, but was not identified on initial inspection.

Visual isolation error.

A 2-week-old, former 24-week gestation infant with chronic lung disease. The X-ray was obtained to confirm location of a feeding tube within the stomach. Frontal view of the chest and abdomen (A) shows the feeding tube in adequate position. A healing left humerus fracture (arrows, B) was missed.

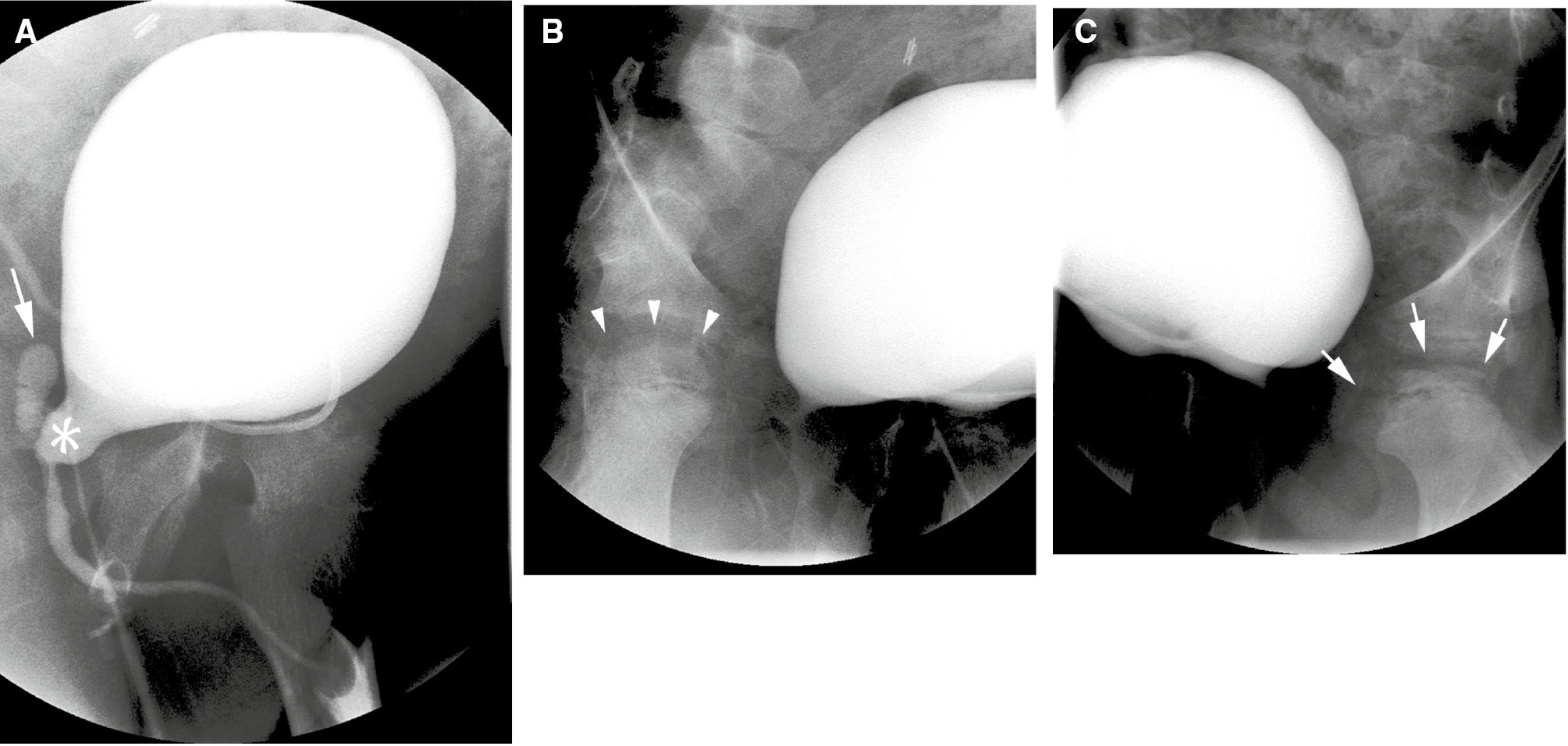

A second contributing factor to perceptual error is the phenomenon of inattentional blindness. The term was introduced by Mack and Rock in the 1990s, and is defined by the failure to notice a fully visible, but unexpected object because attention was engaged on another task, event, or object [19]. In one study, participants were asked to count basketball passes by players wearing white shirts and to ignore passes made by players wearing black. Approximately 50% of subjects watching the video did not notice a person in a gorilla suit entering the scene, stopping to face the camera and thump its chest before exiting on the other side [20]. Thus, if a finding is not expected on an imaging study, there is a strong likelihood that it will be missed (“I will see it when I believe it”). This phenomenon was shown in a study of 24 chest radiologists asked to identify pulmonary nodules in a stack of chest CT images. A gorilla, 48 times larger than the average nodule, was inserted in the last case. More than 80% of radiologists failed to see the gorilla. Of note is that failure to see the gorilla was not due to a truncated visual search. In fact, visual tracking of the radiologists showed that the majority of those who missed the gorilla had actually looked directly at the location of the gorilla [21] (Figure 3).

Inattentional blindness error.

Voiding cystourethrogram in a 9-year-old male with treated posterior urethral valves. Three images from the study are shown. Oblique view of the bladder during voiding (A) shows a dilated posterior urethra (asterisk), and reflux into a dilated utricle (arrow). Right oblique view (B) of the bladder shows a normal femoral head (arrow heads). Left oblique view (C) shows sclerosis and fragmentation changes of the left femoral head due to avascular necrosis (arrows). This unexpected, but radiographically obvious finding was initially missed.

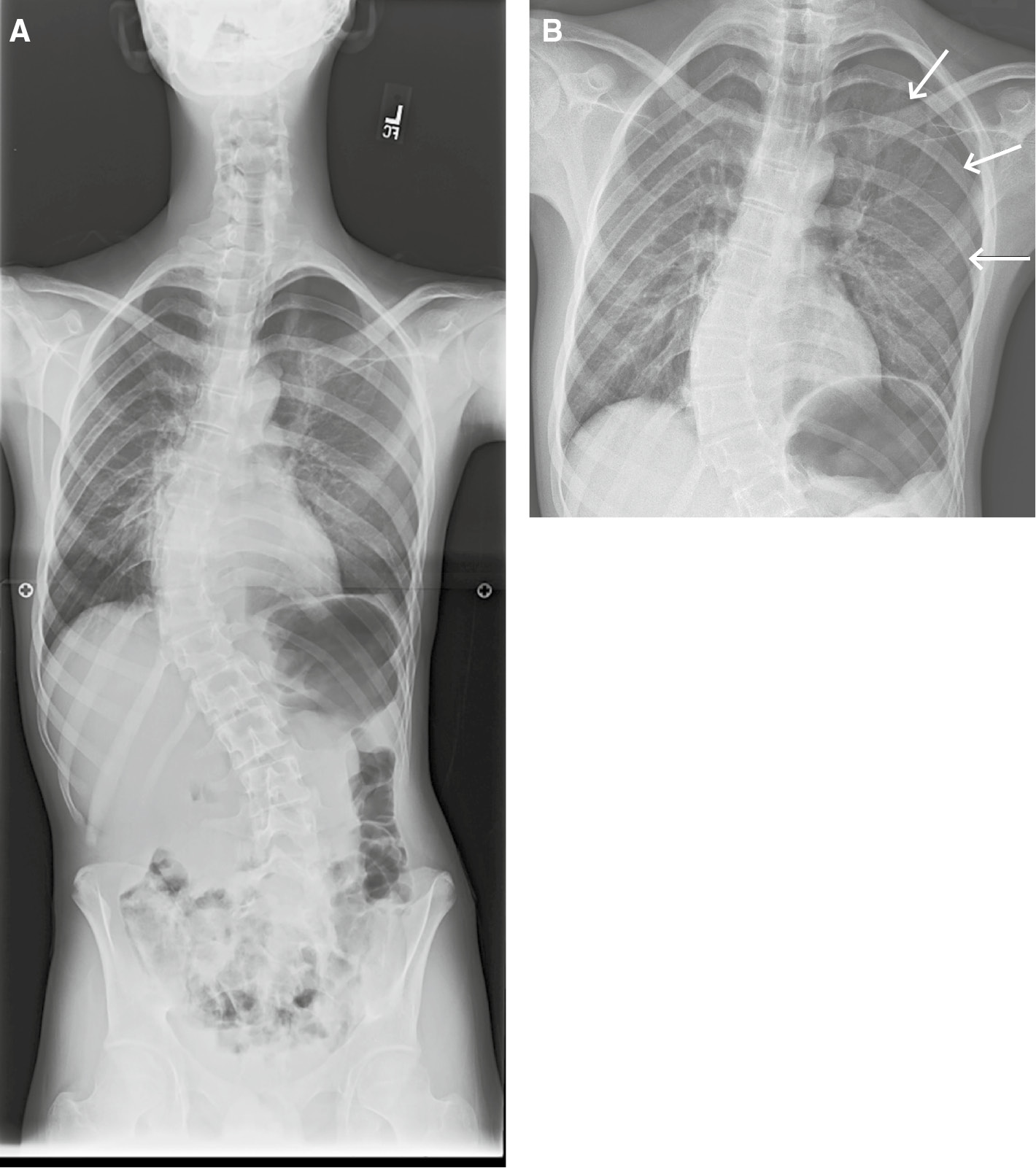

Failure to identify the absence of an expected image feature is another manifestation of inattentional blindness. In one study, radiologists were shown chest X-rays with a clavicle removed. When no cues were given, approximately 60% of radiologists failed to identify the abnormality. When historical cues were added (e.g. chest X-ray for metastatic survey) the detection rate increased to 83% [22] (Figure 4).

Inattentional blindness error.

Frontal radiograph of the entire spine (A) obtained for monitoring of scoliosis in a 15-year-old male with upper back pain. An unexpected, large left pneumothorax (B, arrows) was missed.

The effect of clinical history on radiological interpretation has been studied extensively, and has been shown to also have an important role on visual error [23], [24], [25]. In one study, the availability of pertinent clinical history increased the accuracy of chest radiographs from 16% to 72% for trainees, and from 38% to 84% for experienced radiologists [12]. Accurate clinical history appears to improve the radiologist’s accuracy by focusing perceptual attention to the identification of specific lesions. A distracting, or incorrect clinical history however, can have the opposite effect by misdirecting the radiologist’s search [26].

Finally, it is thought that an increased incidence of perceptual errors may be attributable to certain human risk factors such as increased pace of interpretation, fatigue, and work-place distractions such as phone calls and e-mails [3], [27], [28]. The average radiologist work-load has increased dramatically. Over the last decade, radiologists have been required to read more cases with more images per case resulting in an increasing pace of interpretation in order to “keep up” [29], [30]. In our own department, it is not unusual for a single magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) examination to contain more than 3000 images (Figure 5). As a result, it becomes impossible for the radiologist to devote an adequate amount of attention to each image. Even an excellent radiologist is not as keen at the end of the day as she is at the beginning of the work day. Eye strain and fatigue take their toll and lead to decreased visual accommodation at the end of the day compared to early morning resulting in more myopia as the day progresses, leading to a possible drop in diagnostic accuracy. Fatigue can also result in a decrease in the radiologist’s working memory, particularly after several hours of continuous and prolonged decision making. The increased amount of effort (cognitive load) required to make an accurate diagnosis when tired can result in the radiologist taking short-cuts and subsequent diagnostic errors [31], [32].

Summary image from a chest CT obtained for evaluation of possible interstitial lung disease shows the number of images contained within the study (3184).

Strategies for error reduction

Some strategies are simple and self-evident, and can help to improve the conspicuity of lesions. These include the routine use of window and level tools, review of prior imaging studies, and availability and review of appropriate patient history [10], [18].

Complete elimination of error from radiology has proved impossible over many decades of effort. However, there are a number of corrective strategies that, when taken together, have the potential for serious mitigation of perceptual errors.

The first strategy attempts to correct for framing bias (interpretation strongly influenced by the way in which the clinical problem is presented) by an initial “masked” interpretation of the image, performed without knowledge of the clinical indication for the imaging study. This allows a “gestalt” evaluation of the entire image without selective focus. A second, more focused and detailed search is performed after a specific clinical concern is articulated. This approach is thought to effectively utilize both systems of decision-making [32].

The second strategy is the use of a structured report as an attempt to minimize SOS error. Structured reports act as a checklist to promote consistency in visual approach, and help avoid predictable biases. This approach can be helpful in considering common and serious “do-not-miss” diagnoses [32].

Self-prompting verbalization of the focus of attention has also been shown to be an effective strategy in reducing search satisfaction errors. In a study of SOS errors in chest X-rays, Berbaum et al. [33] showed improved detection of pulmonary nodules when the radiologist verbally described the focus of attention during reporting a case. They attributed this improvement primarily to fewer decision-making errors rather than faulty pattern recognition. This is especially useful in patients with marked physical deformity where anatomic structures may be displaced in unexpected ways, and poorly positioned endovascular catheters and tubes may be misinterpreted as being in the correct location [8].

Conclusions

The process of radiologic image interpretation is a very complex process that we are still attempting to fully understand. The interplay among cognitive, visual physiologic and psychologic processes makes it unlikely that any one strategy will be effective in eliminating errors. However, interventions exist and can help mitigate errors. In addition, continued mindfulness of individual biases and short-cuts, and an institutional culture of education and safety are key to mimimize interpretive errors in radiology.

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Donald JJ, Barnard SA. Common patterns in 558 diagnostic radiology errors. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2012;56:173–8.10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02348.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Taylor GA, Voss SD, Melvin PR, Graham DA. Diagnostic errors in pediatric radiology. Pediatr Radiol 2011;41:327–34.10.1007/s00247-010-1812-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Bruno MA, Walker EA, Abujudeh HH. Understanding and confronting our mistakes: the epidemiology of error in radiology and strategies for error reduction. Radiographics 2015;35: 1668–76.10.1148/rg.2015150023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Kundel HL. History of research in medical image perception. J Am Coll Radiol 2006;3:402–8.10.1016/j.jacr.2006.02.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Kundel HL, Nodine CF, Carmody DP. Visual scanning, pattern recognition, and decision-making in pulmonary nodule detection. Invest Radiol 1978;13:175–81.10.1097/00004424-197805000-00001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Manning D. Medical image perception: its achievements, challenges and a role in medical education. Keynote Presentation Medical Image Perception Society Conference (MIPS XIV, Dublin, August 2011). Available at: https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:demt3HAljV0J:https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David_Manning3/publication/282155230_Medical_Image_PerceptionIts_Achievements_Challenges_and_a_Role_in_Medical_Education/links/56055d3e08aeb5718ff16720+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&client=safari. Accessed on June 12, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

7. Nodine CF, Mello-Thoms C, Kundel HL, Weinstein SP. Time course of perception and decision making during mammographic interpretation. AJR 2002;179:917–23.10.2214/ajr.179.4.1790917Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Fuentealba I, Taylor GA. Diagnostic errors with inserted tubes, lines and catheters. Pediatr Radiol 2012:42;1305–15.10.1007/s00247-012-2462-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Krupinski EA, Berbaum KS. Does reader visual fatigue impact interpretation accuracy? Proc. SPIE. 7627, Medical Imaging 2010: Image Perception, Observer Performance, and Technology Assessment, 76270M (March 04, 2010). doi: 10.1117/12.841050.10.1117/12.841050Search in Google Scholar

10. Croskery P. Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv in Health Sci Educ 2009;14:27–35.10.1007/s10459-009-9182-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Graber ML. Educational strategies to reduce diagnostic error: can you teach this stuff? Adv in Health Sci Educ 2009;14:63–9.10.1007/s10459-009-9178-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Brady A, Laoide RO, McCarthy P, McDermott R. Discrepancy and error in radiology: concepts, causes and consequences. Ulster Med J 2012;81:3–9.Search in Google Scholar

13. Renfrew DL, Franken EA, Berbaum KS, Weigelt FH, Abu-Yousef MM. Error in radiology: classification and lessons in 182 cases presented at a problem case conference. Radiology 1992;183:145–50.10.1148/radiology.183.1.1549661Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Berbaum KS, Franken EA Jr, Dorfman DD, Rooholamini SA, Kathol MH, Barloon TJ, et al. Satisfaction of search in diagnostic radiology. Invest Radiol 1990;25:133–40.10.1097/00004424-199002000-00006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Berbaum KS, Krupinski EA, Schartz KM, Caldwell RT, Madsen MT, Hur S, et al. Satisfaction of search in chest radiography 2015. Acad Radiol 2015;22:1457–65.10.1016/j.acra.2015.07.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Ashman CJ, Yu JS, Wolfman D. Satisfaction of search in osteoradiology. AJR Am J. Roentgenol 2000;175:541–4.10.2214/ajr.175.2.1750541Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Berbaum KS, Schartz KM, Caldwell RT, Madsen MT, Thompson BH, Mullan BF, et al. Satisfaction of search from detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography of the chest. Acad Radiol 2013;20:194–201.10.1016/j.acra.2012.08.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Engelkemier DR, Taylor GA. Pitfalls in pediatric radiology. Pediatr Radiol 2015;45:915–23.10.1007/s00247-014-3196-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Simons DJ. Inattentional blindness. Scholarpedia 2007;2: 3244–51.10.4249/scholarpedia.3244Search in Google Scholar

20. Simons DJ, Chabris CF. Gorillas in our midst: sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception 1999;28:1059–74.10.1068/p281059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Drew T, Vo ML, Wolfe JM. The invisible gorilla strikes again: sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers. Psychol Sci 2013;24:1848–53.10.1177/0956797613479386Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Potchen EJ. Measuring observer performance in chest radiology: some experiences. J Am Coll Radiol 2006;6:423–32.10.1016/j.jacr.2006.02.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Berbaum KS, Franken EA, El-Khoury GY. Impact of clinical history on radiographic detection of fractures: a comparison of radiologists and orthopedists. Am J Roentgenol 1989;153:1221–4.10.2214/ajr.153.6.1221Search in Google Scholar

24. Berbaum KS, Franken EA Jr, Anderson KL, Dorfman DD, Erkonen WE, Farrar GP, et al. The influence of clinical history on visual search with single and multiple abnormalities. Invest Radiol 1993;28:191–201.10.1097/00004424-199303000-00001Search in Google Scholar

25. McNeil BJ, Hanley JA, Funkenstein HH, Wallman J. Paired receiver characteristic curves and the effect of history on radiographic interpretation. CT of the head as a case study. Radiology 1983;149:75–7.10.1148/radiology.149.1.6611955Search in Google Scholar

26. Fitzgerald R. Error in radiology. Clin Radiol 2001;56:938–46.10.1053/crad.2001.0858Search in Google Scholar

27. Sokolovskaya E, Shinde T, Ruchman RB, Kwak AJ, Lu S, Shariff YK, et al. The effect of faster reporting speed for imaging studies on the number of misses and interpretation errors: a pilot study. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:683–8.10.1016/j.jacr.2015.03.040Search in Google Scholar

28. Berlin L. Faster reporting speed and interpretation errors: Conjecture, evidence, and malpractice implications. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:894–6.10.1016/j.jacr.2015.06.010Search in Google Scholar

29. Krupinski EA. Current perspectives in medical image perception. Atten Percept Psychophys 2010;72:1205–17.10.3758/APP.72.5.1205Search in Google Scholar

30. Lu Y, Zhao S, Chu PW, Arenson RL. An update survey of academic radiologists’ clinical productivity. J Am Coll Radiol 2008;5:817–26.10.1016/j.jacr.2008.02.018Search in Google Scholar

31. Beard DV, Hemminger BM, Deneisbeck KM, Brown PH, Johnston RE. Cognitive load during CT interpretation. SPIE 1994;2166:131–8.Search in Google Scholar

32. Lee CS, Nagy PG, Weaver SJ, Newman-Toker DE. Cognitive and system factors contributing to diagnostic errors in radiology. Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:611–7.10.2214/AJR.12.10375Search in Google Scholar

33. Berbaum KS, Franken EA Jr, Dorfman DD, Caldwell RT, Krupinski EA. Role of faulty decision making in the satisfaction of search effect in chest radiography. Acad Radiol 2000;7: 1098–106.10.1016/S1076-6332(00)80063-XSearch in Google Scholar

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Improving diagnosis in radiology – progress and proposals

- Reviews

- Improving diagnosis in health care: perspectives from the American College of Radiology

- The role of radiology in diagnostic error: a medical malpractice claims review

- Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad

- Perceptual errors in pediatric radiology

- 256 Shades of gray: uncertainty and diagnostic error in radiology

- Using Bayes’ rule in diagnostic testing: a graphical explanation

- X-ray art images: objects from nature

- Mini Review

- Assigning responsibility to close the loop on radiology test results

- Opinion Papers

- Information overload: when less is more in medical imaging

- Radiology education: a radiology curriculum for all medical students?

- Letter to the Editor

- Demonstration Collaborative project to reduce emergency department radiologic diagnostic errors

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Improving diagnosis in radiology – progress and proposals

- Reviews

- Improving diagnosis in health care: perspectives from the American College of Radiology

- The role of radiology in diagnostic error: a medical malpractice claims review

- Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad

- Perceptual errors in pediatric radiology

- 256 Shades of gray: uncertainty and diagnostic error in radiology

- Using Bayes’ rule in diagnostic testing: a graphical explanation

- X-ray art images: objects from nature

- Mini Review

- Assigning responsibility to close the loop on radiology test results

- Opinion Papers

- Information overload: when less is more in medical imaging

- Radiology education: a radiology curriculum for all medical students?

- Letter to the Editor

- Demonstration Collaborative project to reduce emergency department radiologic diagnostic errors