Abstract

Background: Biological variation (BV) data enable assessment of the significance of changes in serial measurements observed within a subject and are used to set analytical quality specifications. This data is available in a database held in Westgard website (http://www.westgard.com/biodatabase1.htm). Some limitations of this data, however, have been identified in recent published reviews. The aim of this paper is to show the reliability of the published BV data and to identify ongoing works to address some of its limitations.

Methods: The BV data currently hosted on the Westgard website was examined. Distribution of measurands stratified by the number of cited references upon which the database entry is based and the distribution of papers stratified by publication year, are shown. Moreover, BV data available in literature for glycated hemoglobin, C-reactive protein, glycated albumin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transferase are evaluated.

Results: The results obtained show that most BV data come just from a few papers or only one paper and that a lot of publications are dated, therefore this data is too obsolete to be used. Furthermore critical review of the BV database highlights a number of factors that might impact on the reliability of the BV data entries and translation into current practice.

Conclusions: A number of issues clearly undermine the value of the current database. These issues are being considered by the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, biological variation working group, in collaboration with a Spanish group responsible for the database updating.

Introduction

Knowledge of biological variation (BV) of measurands enables a model suggested to set quality specifications for the analytical phase within medical laboratories [1]. The model is one of five identified at Stockholm consensus conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine [2]. The BV model was recognized as the second in the hierarchy to fulfill medical needs.

BV data, if correctly defined, have other highly useful and important applications. Those include the assessment of significance of change in serial measurements observed within a subject [3], definition of analytical goals to enable safe application of laboratory measurements in a clinical setting [4] and derivation of an index of individuality (II) to enable assessment of the utility of conventional population-based reference intervals [5]. Given the importance of BV data, it is clear that access to this data is essential to the clinical laboratory, and that users should be confident that they are well characterized and fit for purpose.

Compiled sources of this data have been made available to the laboratory medicine specialists. Fraser published a collection of BV data (including data from 1988 to 1991) in 1992 [6]. In 1999 Ricos et al. [7] compiled and made available a database that included BV of biochemical and hematological measurands. This has evolved into a BV database (BV-DB) gathered from 240 publications that continues to be expanded, updated and published online [8]. It is extensive and presents data and derived analytical quality specifications for imprecision (I%), bias (B%) and total error (TE%) for more than 350 measurands. It is however, only recently that Perich et al. have published criteria used to evaluate the reliability of the data included in the BV-DB [9].

The BV-DB provides an important source of BV data that is widely available, used and referenced for clinical application. However, some limitations of this approach have, been identified at a meeting of over 40 medical laboratory opinion leaders [10]. Concerns have been further specifically identified in published reviews of the BV of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) [11], C-reactive protein (CRP) [12], urinary albumin [13] and some enzymes [14]. These publications lead to the conclusion that there is a need for a standardized approach to derivation and publication of BV data to enable their safe accurate and effective application in a clinical setting.

This paper explores the further reliability of the online BV-DB and identifies ongoing work to address some of the limitations of the approach and work to be undertaken to enable an expansion of the available data through co-operative working by the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM), Biological Variation Working Group (BVWG) [15], in collaboration with a Spanish group responsible for the BV-DB updating [8].

Materials and methods

Examination of the biological variation database

The BV-DB currently hosted on the Westgard website [16] was examined. The relevant data are held on three web pages. The first page contains BV data entries for various measurands listing within-subject biological variation (CVI), and between-subject biological variation (CVG), and the desirable specifications for I%, B% and TE% (http://www.westgard.com/biodatabase1.htm). The second page (http://www.westgard.com/biodatabase2.htm) provides an index to the third page which contains the references to the publications from which the data were extracted. In the absence of any agreed standards for generation of BV data, the work of Fraser and Harris [17] is considered to provide an established framework for this work. Since its publication, the protocol described is frequently cited in publications of BV experiments providing a widely accepted theoretical protocol to enable generation of reliable BV data. The authors proposed a standard approach to the definition and analysis of BV, defining in detail several steps which are summarized below:

Selection of subjects;

Sample collection, handling and storage;

Analysis of specimens under conditions that minimize analytical I%;

Data handling: distributional assumptions, outlier detection, analysis of variance.

Reliability of entries into the database has been assessed here using the theoretical model set out by Fraser and Harris [17] as a benchmark. Several reviews that have also taken this approach have been taken into account as part of this exercise [11, 12, 14]. Consideration has been given to the utility 95% confidence intervals surrounding the estimates of CVI as part of the assessment of BV studies. A particular focus is set upon HbA1c, CRP, glycated albumin (GA), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) to demonstrate the issues that may be reflected in the BV-DB and highlight the need for a more critical approach to generation and reporting of the data.

Results

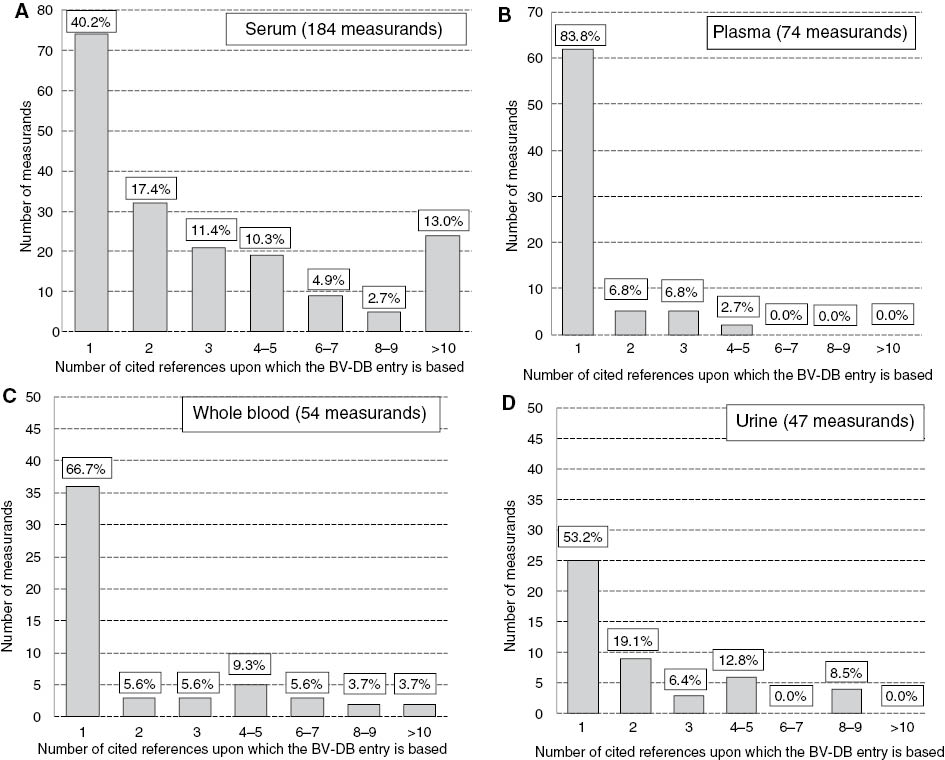

Figures 1 and 2 are derived from examination of the BV-DB. The database lists data for measurands in serum, plasma, whole blood and urine. Figure 1 graphically displays a breakdown of numbers of publications referenced per measurands in each matrix. It is clear that the data base entries are mainly derived from a single publication. Where multiple publications are available the database entry represents a median value of those published [9].

Distribution of measurands stratified by the number of cited references upon which the BV-DB entry is based.

The four panels display data for measurands in different sample matrices included in the database, (A) serum, (B) plasma, (C) whole blood and (D) urine.

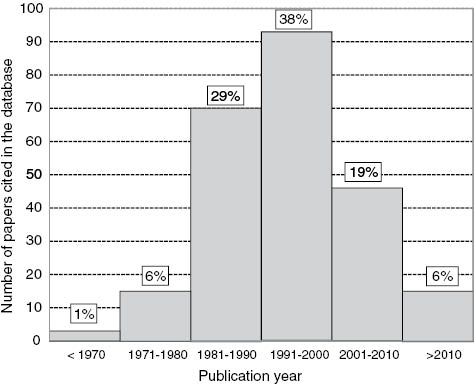

Distribution of 247 papers included in the database stratified by year of publication.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of 247 papers stratified by years of publication included in the database and used in order to calculate BV data.

Of the 247 references cited in the database 36% were published before the seminal paper of Fraser and Harris in 1989 [17] describing a preferred protocol for the generation of data. Furthermore a total of 271 of the database entries were based on evidence from either one or two publications. Of these 28% were published before 1989 with a further 33% between 1989 and 2000.

Glycated hemoglobin

In a critical review on BV of HbA1c published in 2010 by Braga et al. [11], some characteristics of nine studies found in PubMed were summarized and evaluated. They used the Fraser and Harris [17] protocol as a benchmark to assess the studies. Their study indicated that the BV data published could not be considered reliable and expressed some doubt about the criterion used in the study evaluation and selection for inclusion within BV-DB [8]. Currently BV-DB entry is derived from eight papers which are referenced (access September 2014). Two of the eight papers report BV values derived from diabetic populations, and three out of the eight are Spanish papers and not readily accessible for consideration by the user. Two recently published papers reported HbA1c in different units. The first [18] calculated from HbA1c values expressed in International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) units (mmol/mol of hemoglobin), while in the second the data were determined as values expressed in National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) units (% HbA1c). Considering that the formula to convert NGSP unit in IFCC unit has an intercept [NGSP=(0.0915*IFCC)+2.15], it means that the specificities of the two methods are different and calculated CVs cannot be combined [19]. The NGSP units are measured on an interval scale without a true zero point and without equality of ratios, so CVs are therefore wrong; whereas IFCC units are measured on a ratio scale with a true zero point and equality of ratios, so CVs are correct and useful.

C-reactive protein

In a review of the BV studies of CRP [12], 11 papers published between 1993 and 2010 were all appraised. They were evaluated in terms of number and type of enrolled subjects; duration of the study; frequency of sample collection; sample type; sample storage; analytical methodology; assay sensitivity; and statistical analysis. The study demonstrated that only one of the 11 studies appeared to fulfill all major pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical requirements to enable valid delivery of BV data. The review further identified the need for delivery well designed studies to deliver appropriately defined BV data. The BV-DB lists only three papers and therefore is incomplete. Furthermore, the values reported are respectively for CVI and CVG are 42.2% and 76.3%. As CV values >33.3% indicate that the distributions are not Gaussian (not normally distributed) this raises questions around the data management as the data have to be transformed into logarithms, or elaborated in a non-parametric way [17]. In the BV-DB 38 out of 370 measurands have CVI% values >33%, and 120 out of 339 CVG values >33%.

Glycated albumin

Erroneous entries were identified in the BV-DB page 2 relating to GA. GA was identified as coming from three papers, but two of those do not have any BV values for GA, but refer to HbA1c. This means that the values reported in the database (CVI=5.2, CVG=10.3) come from a single study published in 1993 [20]. That study was carried out with 10 subjects, five samples taken per subject, and the samples were measured in only one replicate. The absence of a duplicate measurement meant that it was not possible to calculate 95% confidence interval (CI) around the CVI by application of the method published by Roraas et al. [21]. The lack of CI on BV data means that it was not possible to meaningfully compare these values with new values from another new study that is as yet not included in the BV-DB [22].

From the data reported in that paper CIs around BV data were calculated and were found to be (shown in brackets): CVI=2.1%(1.7–2.6), and CVG=10.6%(7.9–15.9). The CVI value reported in BV-DB (5.2%) is outside of the CI calculated for the CVI reported in the more recent publication paper (1.7%–2.6%), implying that it may come from a non-representative sample of the population or from a different population and cannot be incorporated as part of a combined single data entry into the BV-DB.

Alanine aminotrasferase, aspartate aminotrasferase and γ-glutamyl transferase

A systematic review has recently been published which evaluated publications reporting BV of ALT (10 papers) AST (14 papers) and γ-GT (9 papers) [14]. The published BV data cited in that review displayed a wide range of values, and where it was possible to estimate them, exhibited very wide CIs. Many factors contributed to this variability including: characteristics of the population studied; study design, in terms of number of subjects studied, length of the study period, pre-analytical issues, sample type, analytical method used, and the data analysis.

Consideration of the year of publication of the ALT papers indicated that they were in the main published between 1974 and 1992. This means that they precede the publication and adoptions of IFCC optimized methods that for these enzymes were published in 2002 [23–25]. In fact only one of the studies of γ-GT [26] and none of AST or ALT studies were performed using the IFCC optimized measurements. This raises questions concerning the usefulness of all the BV data available for these enzymes.

The BV-DB does not deliver granular enough data to enable users to easily assess the quality and utility of the published estimates of BV. The degree of complexity of the published data, failure to adhere to the theoretical protocol identified by Fraser and Harris [17], and the obsolescence of the methodologies used, is such that doubt must be cast upon the universal application of the single estimates of BV appearing in online databases for these three enzymes [14].

Discussion

Critical review of the BV-DB highlights a number of factors that might impact on the reliability of the BV data entries and translation into current practice. When taken into account alongside a number of systematic reviews [11, 12, 14] of BV data, some key issues identified need to be addressed to enable safe, accurate and effective application of these data.

Non-compliance with best practice delivers uncertainty around the data and the fact that a high proportion of the data sets are generated from single non-corroborated studies leads to uncertainty around the value and transportability of the data. It has been identified that age of some of the studies and subsequent developments in methodologies mean that data may not be suitable for application in today’s practice.

The availability of multiple studies per measurand highlights inconsistencies in approach to protocols applied in the various studies, issues with data management and other important factors that will impact on the absolute values obtained and make it difficult to combine data to enable singles data entry within the BV-DB. The existing data sets may however still be of use and there is a need to be able to assess their quality and value for inclusion of historical data within any future database. The provision of key data to enable users understanding of the quality of the data and the delivery of CIs around the estimates of BV data are essential for the future development of any BV-DB.

Roraas et al. showed [21] it is necessary to know analytical standard deviation (SDA) and intra-subject standard deviation (SDI) (to calculate the ratio SDA/SDI), number of replicates (there must be at least two of these replicates), number of samples/subject, and the number of individuals, in order to calculate CI around BV data. This information allows the calculation of the CIs and enables determination of the power of studies to deliver the required data. The magnitude of the CI of the SDI [and also reference change value (RCV)] varies with the number of individuals, the number of samples from each individual, and the number of replicates [for ratio SDA/SDI>1] [21]. The analytical I% must be taken into consideration in order to obtain good estimates of BV: the higher SDA is the wider CI will be. Study design, number of replicates, number of samples, and number of subjects have a great impact on the reliability with which we can estimate the SDI and RCV of an analyte, and that the effect of these variables varies with the ratio of SDA to SDI. Fraser and Harris [17] stated that: “the components of variation can be obtained from a relatively small number of specimens collected from a small group of subjects”, this may be the case, but the work of Roraas et al. enable [21] the truth of this statement to be tested.

In the absence of a defined standard for the production of BV data, the work of Fraser and Harris [17] provides an excellent framework for determination of meaningful BV data. This is not always closely followed. They highlighted the need for duplicate measurements to be undertaken in a single run under conditions that minimize analytical I%. It is clear from this review that many studies do not follow this approach which makes it impossible to calculate CIs to be used in the assessment of the data. In addition, lack of knowledge of CIs opens up the possibility that data from non-compatible studies are being combined within the BV-DB and delivering error.

A further problem with the current BV-DB is that clearly not all studies are captured and the user is not able to consult the original papers to study the detail as they may have limited accessibility. This was the case with the HbA1c example mentioned in this review. This might be considered to be less of an issue if recognized standards existing for generation and publication of data. In general assessment of the publications used to construct the current BV-DB it is worrying that the majority of papers failed to indicate the application of statistical tests of normality to the data [11, 12, 14]. By definition the CV of a Gaussian distribution cannot exceed 33.3% [14, 21], but, as shown in the results section, 10% of CVI values reported in BV-DB are >33%. In the PCR example given in this paper the CVI was seen to be >33%. In this and other cases the calculation of RCV is invalid known that the formula to calculate the RCV [2.77(CVA2+CVI2)1/2] for bidirectional change at p<0.05, is valid only if the distribution of the data is Gaussian [3]. Suitable “health warnings” should accompany the data in such cases.

As recently underlined by two editorials published in Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine [27, 28] and by the editorial published in Annals of Clinical Biochemistry [29], a number of issues clearly undermine the value of the current BV-DB. These issues are being considered by the EFLM BVWG [30], in collaboration with a Spanish group responsible for the BV-DB updating [8].

In the absence of standards for generation and reporting of BV data the BVWG have proposed the use of a checklist that will assist laboratory medicine professionals to generate, compile and publish high quality BV data and to objectively assess the content and quality of existing publications and enable referees of future BV publications [30]. This is based on expert opinion and consideration of existing best practice (e.g., Fraser and Harris [17], Roraas et al. [21]). There is a need to deliver updated studies on biological variability using contemporary analytical techniques. Delivery of valid and appropriately powered studies is time consuming and organizationally difficult, and mechanisms are being developed to facilitate the delivery of materials in the form of a bank of specimens to be made available to enable updates of this type.

BVWG is working on a new sample collection in order to update the existing BV data.

The project “Samples collection from healthy volunteers for BV values update” has just been approved by the Ethical Committee of San Raffaele Hospital Milan, Italy, and is going to start in April 2015. This project is a multicenter study involving seven European laboratories with all the pre-analytical requirements complying with the ideal protocol identified by Fraser and Harris [17]. Samples will be collected from 105 healthy volunteers and stored at a central facility as a resource for the delivery of contemporary BV data.

This dual approach enables a driving up of the quality of BV data with the checklist enabling assessment and validation of historical data and provision of a framework to drive up the quality of future studies and their reporting to enable safe, accurate and effective application of the data. The approach of a specimen’s collection will enable delivery of up-to-date and valid BV data using contemporary analytical methods.

Conclusions

The concept of the BV-DB is powerful and the current database represents the product of an immense amount of work. It has proven to be a valuable resource, but it is clear that there are a number of issues that impact upon its current value.

There is massive variation in the quality of the studies delivering data reported in the current database. The delivery of a complete database that includes the products of appropriately powered studies delivering indices of BV with confidence intervals provides challenges. In the absence of recognized standards application of a BV critical checklist based on expert opinion will enable historical data to be reassessed and drive up the quality of future reported studies. This will improve the usefulness of future databases.

The need to deliver contemporary data can be facilitated by delivery of a bank of appropriately collected specimens which will enable new and valid BV data sets to be delivered for key target areas yet to be identified.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Thomas Roraas for his statistical support, Dr. Ferruccio Ceriotti for his supervision, and all BVWG members [15] for enabling the two new projects to be undertaken.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Financial support: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Fraser CG. The nature of biological variation. In: Biological variation: from principles to practice. Washington: AACC Press, 2001;1–27.Search in Google Scholar

2. Fraser CG, Kallner A, Kenny D, Petersen PH. Introduction: strategies to set global quality specifications in laboratory medicine. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999;59:477–8.10.1080/00365519950185184Search in Google Scholar

3. Fraser CG. Reference change values: the way forward in monitoring. Ann Clin Biochem 2009;46:264–5.10.1258/acb.2009.009006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Cotlove E, Harris EK, Williams GZ. Biological and analytic components of variation in long-term studies of serum constituents in normal subjects. 3. Physiological and medical implications. Clin Chem 1970;16:1028–32.10.1093/clinchem/16.12.1028Search in Google Scholar

5. Fraser CG. Hyltoft Petersen P. Analytical performance characteristics should be judges against objective quality specifications. Clin Chem 1999;45:321–3.10.1093/clinchem/45.3.321Search in Google Scholar

6. Fraser CG. Biological variation in clinical chemistry. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992;116:916–23.Search in Google Scholar

7. Ricos C, Alvarez V, Cava F, Garcia-Lario JV, Hernandez A, Jimenez CV, et al. Current databases on biological variation: pros, cons and progress. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999;59:491–500.10.1080/00365519950185229Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Ricos C, Alvarez V, Cava F, Garcia-Lario JV, Hernandez A, Jimenez CV, et al. Desirable specification for total error, imprecision, and bias, derived from intra- and inter- individual biologic variation. The 2014 update. Available from: www.westgard.com/biodatabase1.htm. Accessed September, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

9. Perich C, Minchinela J, Ricos C, Fernández-Calle P, Doménech MV, Simóne M, et al. Biological variation database: structure and criteria used for generation and update. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:299–305.10.1515/cclm-2014-0739Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Cooper G, Dejonge N, Ehrmeyer S, Yundt-Pacheco J, Jansen R, Ricos C, et al. Collective opinion paper on finding of the 2010 convocation of experts on laboratory quality. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011;49:793–802.10.1515/CCLM.2011.149Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Braga F, Dolci A, Mosca A, Panteghini M. Biological variability of glycated hemoglobin. Clin Chim Acta 2010;411:1606–10.10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Braga F, Panteghini M. Biological variability of C-reactive protein: is the available information reliable? Clin Chim Acta 2012;413:1179–83.10.1016/j.cca.2012.04.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Miller GW, Bruns DE, Hortin GL, Sandberg S, Aakre KM, McQueen MJ, et al. Current issues in measurement and reporting of urinary albumin excretion. Clin Chem 2009; 55:24–38.10.1373/clinchem.2008.106567Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Carobene A, Braga F, Roraas T, Sandberg S, Bartlett WA. A systematic review of data on biological variation for alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transferase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:1997–2007.10.1515/cclm-2013-0096Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Available from: http://www.efcclm.org/index.php/wg-biological-variation.html. Accessed November 2014.Search in Google Scholar

16. Available from: http://www.westgard.com. Accessed November, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

17. Fraser CG, Harris EK. Generation and application of data on biological variation in clinical chemistry. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 1989;27:409–37.10.3109/10408368909106595Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Braga F, Dolci A, Montagnana M, Pagani F, Paleari R, Guidi GC, et al. Revaluation of biological variation of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) using an accurately designed protocol and an assay traceable to the IFCC reference system. Clin Chim Acta 2011;412:1412–6.10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Lenters-Westra E, Roraas T, Schindhelm RK, Slingerland RJ, Sandberg S. Biological variation of hemoglobin A1c: consequences for diagnosing diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem 2014;60:1570–2.10.1373/clinchem.2014.227983Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Davie SJ, Whiting KL, Gould BJ. Biological variation in glycated proteins. Ann Clin Biochem 1993;30:260–4.10.1177/000456329303000306Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Roraas T, Hyltoft Petersen P, Sandberg S. CIs and power calculations for within-person biological variation: effect of analytical imprecision, number of replicates, number of samples, and number of individuals. Clin Chem 2012;58:1306–13.10.1373/clinchem.2012.187781Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Montagnana M, Paleari R, Danese E, Salvagno GL, Lippi G, Guidi GC, et al. Evaluation of biological variation of glycated albumin (GA) and fructosamine in healthy subjects. Clin Chim Acta 2013;423:1–4.10.1016/j.cca.2013.04.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Schumann G, Bonora R, Ceriotti F, Férard G, Ferrero CA, Frank PF, et al. IFCC primary reference procedures for the measurement of catalytic activity concentrations of enzymes at 37 degrees C. International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Part 4. Reference procedure for the measurement of catalytic concentration of alanine aminotransferase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002;40:718–24.10.1515/CCLM.2002.124Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Schumann G, Bonora R, Ceriotti F, Férard G, Ferrero CA, Frank PF, et al. IFCC primary reference procedures for the measurement of catalytic activity concentrations of enzymes at 37 degrees C. International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Part 5. Reference procedure for the measurement of catalytic concentration of aspartate aminotransferase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002;40:725–33.10.1515/CCLM.2002.125Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Schumann G, Bonora R, Ceriotti F, Férard G, Ferrero CA, Frank PF, et al. IFCC primary reference procedures for the measurement of catalytic activity concentrations of enzymes at 37 degrees C. International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Part 6. Reference procedure for the measurement of catalytic concentration of γ-glutamyltransferase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002;40:734–8.Search in Google Scholar

26. Pagani F, Panteghini M. Biological variation in serum activities of three hepatic enzymes. Clin Chem 2001;47:355–6.10.1093/clinchem/47.2.355Search in Google Scholar

27. Aasne AK, Roraas T, Sandberg S. Biological variation – reliable data is essential. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:153–4.Search in Google Scholar

28. Plebani M, Padoan A, Lippi G. Biological variation: back to basics. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:155–6.10.1515/cclm-2014-1182Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Simundic AM, Bartlett WA, Fraser CG. Biological variation: a still evolving facet of laboratory medicine. Ann Clin Biochem 2015;52(pt 2):189–90.10.1177/0004563214567478Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Bartlett WA, Braga F, Carobene A, Coşkun A, Prusa R, Fernandez-Calle P, et al. A checklist for critical appraisal of studies of biological variation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:879–85.10.1515/cclm-2014-1127Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Defining analytical performance specifications 15 years after the Stockholm conference

- Consensus Statement

- Defining analytical performance specifications: Consensus Statement from the 1st Strategic Conference of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Opinion Papers

- The 1999 Stockholm Consensus Conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine

- Setting analytical performance specifications based on outcome studies – is it possible?

- Performance criteria based on true and false classification and clinical outcomes. Influence of analytical performance on diagnostic outcome using a single clinical component

- Analytical performance specifications based on how clinicians use laboratory tests. Experiences from a post-analytical external quality assessment programme

- Rationale for using data on biological variation

- Reliability of biological variation data available in an online database: need for improvement

- A checklist for critical appraisal of studies of biological variation

- Optimizing the use of the “state-of-the-art” performance criteria

- Are regulation-driven performance criteria still acceptable? – The German point of view

- Performance criteria for reference measurement procedures and reference materials

- Performance criteria for combined uncertainty budget in the implementation of metrological traceability

- How to define a significant deviation from the expected internal quality control result

- Analytical performance specifications for EQA schemes – need for harmonisation

- Proposal for the modification of the conventional model for establishing performance specifications

- Before defining performance criteria we must agree on what a “qualitative test procedure” is

- Performance criteria and quality indicators for the pre-analytical phase

- Performance criteria of the post-analytical phase

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Defining analytical performance specifications 15 years after the Stockholm conference

- Consensus Statement

- Defining analytical performance specifications: Consensus Statement from the 1st Strategic Conference of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Opinion Papers

- The 1999 Stockholm Consensus Conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine

- Setting analytical performance specifications based on outcome studies – is it possible?

- Performance criteria based on true and false classification and clinical outcomes. Influence of analytical performance on diagnostic outcome using a single clinical component

- Analytical performance specifications based on how clinicians use laboratory tests. Experiences from a post-analytical external quality assessment programme

- Rationale for using data on biological variation

- Reliability of biological variation data available in an online database: need for improvement

- A checklist for critical appraisal of studies of biological variation

- Optimizing the use of the “state-of-the-art” performance criteria

- Are regulation-driven performance criteria still acceptable? – The German point of view

- Performance criteria for reference measurement procedures and reference materials

- Performance criteria for combined uncertainty budget in the implementation of metrological traceability

- How to define a significant deviation from the expected internal quality control result

- Analytical performance specifications for EQA schemes – need for harmonisation

- Proposal for the modification of the conventional model for establishing performance specifications

- Before defining performance criteria we must agree on what a “qualitative test procedure” is

- Performance criteria and quality indicators for the pre-analytical phase

- Performance criteria of the post-analytical phase