Abstract

In recent years, there has been a growing scholarly interest in the cultural and political significance of joyful, positive and nostalgic memories and forms of remembrance. Without downplaying the role of trauma and oppression in the mnemonic makeup of contemporary societies, memory scholars have increasingly pointed to the co-existence, or parallel existence, of brighter recollections of the past, and to their role in bringing about hope and social mobilization (Katriel & Reading 2015; Keightley & Pickering 2012; Rigney 2018; Sindbæk Andersen & Ortner 2019). Engaging with these streams of thought, my article will offer a closer look at the interplay between memories of friendship and mutual care, and remembrance as a form of caring (Till 2012), which enables the continuation and/or formation of solidaric bonds, practices, and ideas. Empirically, the article departs from Nowa Huta, a district in Kraków, which was founded in 1949 as the “first socialist town in Poland”, and which eventually, in the 1980 s, turned into one of the main bastions of the oppositional Solidarity movement. After 1989, Nowa Huta became fertile ground for memory work of different kinds: commemorations, exhibitions, nostalgic venues and paraphernalia, along with numerous heated debates on the matter of remembrance. While divisive in the public sphere, memory has simultaneously served as a creative and cohesive force for many of the local communities, of different orientation, which put their mark on contemporary Nowa Huta. Drawing on ethnographic field work, my article will illustrate the role of memory in sustaining care and friendship within a few of these communities. It will also show the wider entanglements of these communal memories; how they relate and sometimes serve as corrections to diverging representations of the past and how they move from their ‘original’ confines to a younger generation of locally involved inhabitants in Nowa Huta. In that way, they function as a kind of springboard, a resource, for continuous place-based caring and solidaric action within and for the neighborhood.

1 Introduction

Places are not only made of buildings and streets and policies and plans, but also of the ways in which people make use of them, care about them and remember them (de Certeau 1984; Feld & Basso 1996; Till 2012). This simple claim will guide this article on practices of place care and remembrance in the district of Nowa Huta in Kraków, Poland. Nowa Huta was founded in 1949 as a socialist model town, whose inhabitants and buildings and steel plant were to symbolize the newly installed Peoples Republic of Poland (PRL[1]). If Nowa Huta represented the future in the eyes of the Communist leadership, then Kraków was viewed with suspicion, as an ideologically unreliable, religious, and conservative city. From the start, then, the relationship between the two places – which formally merged into one as Nowa Huta was incorporated into Kraków in 1951 – was fraught with animosities (Chwalba 2004; Lebow 2013). The smoke from the Lenin Steel Plant, and the rural backgrounds of Nowa Huta’s builders, did not sweeten the deal for the “cultured” inhabitants of Kraków, who remained generally negative towards the neighborhood until the 1980 s, when it turned into of the main centers of the oppositional Solidarity movement in Poland (Gut 1993; Chwalba 2004). However, during the 1990 s, Kraków and Nowa Huta drifted apart again, as the latter was increasingly portrayed in public discourse and locally circulating stereotypes as a typical example of the ills of the previous era, epitomized by its socialist realist architecture and destructive steel plant (Gut 1993; Janas 2020; Majewska 2007).

Such a fast-forwarded historiography cannot do justice to the twists, turns and nuances of Nowa Huta’s past, but it does say something about its specificity and “semantic richness” (Golonka-Czajkowska 2013: 13). Among the socialist model towns which surfaced in the region from the 1930 s and onwards, Nowa Huta was the largest one (Åman 1987: 152) – and the only one to boost a resistance movement of Solidarity’s caliber. While it shares characteristics with other industrial towns, born under socialism or before, it also constitutes a case of its own, given the combination of its size, controversial location, ideological underpinnings and the oppositional inclination of its workers (Stenning 2000). The same is true when it comes to the mnemonic infrastructure in Nowa Huta, which took shape after 1989 and exhibits a place-specific scope and strength.[2] Among other things, this infrastructure consists of monuments to the Solidarity era, a museum (Muzeum Nowej Huty),[3] recurrent commemorations, festivities, and educational initiatives, nostalgic venues, and so-called communist tours exotifying life in PRL to (mostly) Western visitors (Golonka-Czajkowska 2013; Poźniak 2014). The retro cars with red stars which take tourists to the neighborhood, as well as other initiatives that could be accused of trivializing or whitewashing PRL, have stirred debates in Nowa Huta, about how to remember and appropriately represent the past in this former socialist flagship-town. Local controversies were influenced by memory politics crafted at the national level, which, during the reigns of national-conservative party Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS), in 2005–2007 and 2015–2023, have emphasized memories of anticommunist resistance, and “disregarded or condemned” any positive remembrance of the PRL (Wawrzyniak 2021: 90; see also Bernhard & Kubik 2014: 60–84; Ochman 2013; Poźniak 2014).

In the last decades, then, Nowa Huta has come to exist as a vibrant site of memory where the past is constantly revisited, elevated, and contested. However, parallel to such undertakings run other memories and ways of remembrance, which are less conspicuous and dramatic but no less significant for the neighborhood. Those memories, which will be in focus in my article, are formed slowly, over longer stretches of time, through people’s ongoing practices and interactions with each other and their material surroundings (Connerton 1989, 2009; Schudson 1989; Wüstenberg 2023). Usually, they are tied up with the close relations of people, which exist, after Ricœur (2004: 131–132), at an “intermediate level of reference between the poles of individual memory and collective memory”. By participating in each other’s lives – as family members, friends, neighbors, or colleagues – those relations render a special, tangible and familial, meaning to human remembrance. Close relations are often shaped in what Connerton (2009: 10) calls locus, or localities, which is the term I will use here, meaning the playgrounds of daily life, such as kitchens, park benches, and workplaces, where people spend most of their time and where, in effect, most of their memories are made. In contrast to memorials, which are bestowed with a mission to testify about and preserve the past, localities are not destined for commemoration. This, however, does not stop unassuming places and memories from occasionally being elevated and cherished by people as tokens of communal traits, ideals, and bonds (Ehn 2007). When I pay particular attention to localities and close relations in this article, I do not want to diminish the significance of memorials and eventful memories. Rather, I want to show how different memories and forms of remembrance feed off each other and how they, in interaction, color the continuous making of a place like Nowa Huta.

When I was doing research in Nowa Huta, I came to think that memories were truly cherished here. To cherish something is to care about it, and for it, in affectionate ways.[4] The notion of care also seemed central in Nowa Huta, where inhabitants would insist on their continuous caring for each other and their wider habitat (cf. Kowalska 2020; Stenning et al. 2010).[5] Broadly understood, care is about the ways in which people depend on each other to get by in life; how they nurture, support and sustain each other physically, materially, and emotionally (Tronto 2013; Milligan & Wiles 2010; Till 2012; Conradson 2003). Usually, care practices are associated with private life, but in this article, I join forces with scholars who argue that caring matters beyond the confines of home and nuclear families. Here, I am particularly interested in caring for place (Till 2012; Wiles & Jayasinha 2013), which I take to include anything from local activism to various forms of small-scale engagement which sustains a place: helping out neighbours, participating in memorials, or supporting local stores and eateries. Following Till (2012), memory work also fits under the broad umbrella of caring for place, which is particularly visible in communities touched by disruption and upheaval, where remembrance often serves as a tool for repair and coming together. That is not to say that memory work is, by default, about caring; it can just as well be driven by other interests, of political and economic nature, for instance. In this article, however, I am on the lookout for the element of care in local memory work, and for the ways in which it rests on caring bonds formed at earlier dates and how it contributes to contemporary understandings of Nowa Huta. The notion of caring for place, together with a focus on close relations, localities and cherished memories, is helpful to the extent that it opens up, widens and deepens, my grasp of local memory work and remembrance.

This article resonates with recent efforts among memory scholars to highlight the significance of positive memories and forms of remembrance. Without downplaying the role of difficult pasts in the mnemonic makeup of contemporary societies, those scholars point to the co-existence, or parallel existence, of brighter recollections, and to their role in bringing about hope and social mobilization (Katriel & Reading 2015; Rigney 2018; Sindbæk Andersen & Ortner 2019). This widening of attention is partly driven by concerns about the consequences of an all too narrow focus on the afterlives of catastrophe, atrocity, and misery. In tandem with such concerns, the notion of nostalgia seems to be losing its bad reputation as a practice that merely, or by default, trivializes or idealizes the past. Indeed, researchers specializing on Eastern and Central Europe were quick to notice the social need that nostalgia has filled in times of systemic transformations, after 1989/91, as well the political edge it possesses, when it pits the best of the past against the hardships of the present and, through that, points to the possibility of alternative ways of living, doing politics and running economies, than the ones which are currently in favor (Todorova & Gille 2010; Velikonja 2009; Wawrzyniak 2021). For my own understanding of nostalgia, the notions of continuity and discontinuity are crucial. Nostalgia not only responds to “pleas for continuity” as Davis (1979: 33) puts it; it also involves in the “positing of discontinuity” (Tannock 1995: 457) as it spells out the existence of a now and a then and a breach of some kind in-between. On the other side of that breach, people might need or want different things from their nostalgic involvement. They might seek refuge in the past, or they might wish retrieve useful ideas, symbols, or skills from it. Whether more past- or more present-oriented, I find it helpful to think of nostalgia as a mode through which positively charged memories are actively kept alive in the wake of, and as a way of handling, changes.

This article is based on ethnographic field work conducted in Nowa Huta between 2009 and 2017. I entered the field in a time of heightened mnemonic activity, following Nowa Huta’s 60th anniversary, which brought about numerous debates, initiatives and commemorations related to the district’s legacy and current predicament (Poźniak 2014: 101–103). Through interviews and observations, my study targeted the mnemonic engagement that surfaced or intensified in the district around this time. Influenced by anthropological phenomenology and hermeneutical perspectives, I was particularly focused on the emotional and experiential aspects of remembrance and the meanings ascribed to unfolding experience (Adjam 2017; Dilthey 1976; Frykman & Gilje 2003; Jackson 1996). Instead of offering an exhaustive account of memory work in Nowa Huta, I worked with specific cases pertaining to different memories and forms of remembrance, paying attention to the ways in which memories mattered to people; how they informed and animated their relations and practices in and on behalf of Nowa Huta. What I set forth to illustrate in this article is the practice of cherishing memories “in action”, across different settings, and how this practice makes possible the continuation of place-based caring and solidaric action within and for the neighborhood (Arendt 1958; Till 2012). In the following section, I will focus on an informal gathering with nostalgic pensioners, after which I turn my attention to the memory work of Solidarity members. The final section is dedicated to the broader issue of remembrance, place care and local lifestyles in contemporary Nowa Huta.

2 A Cheerful Gathering in Nowa Huta

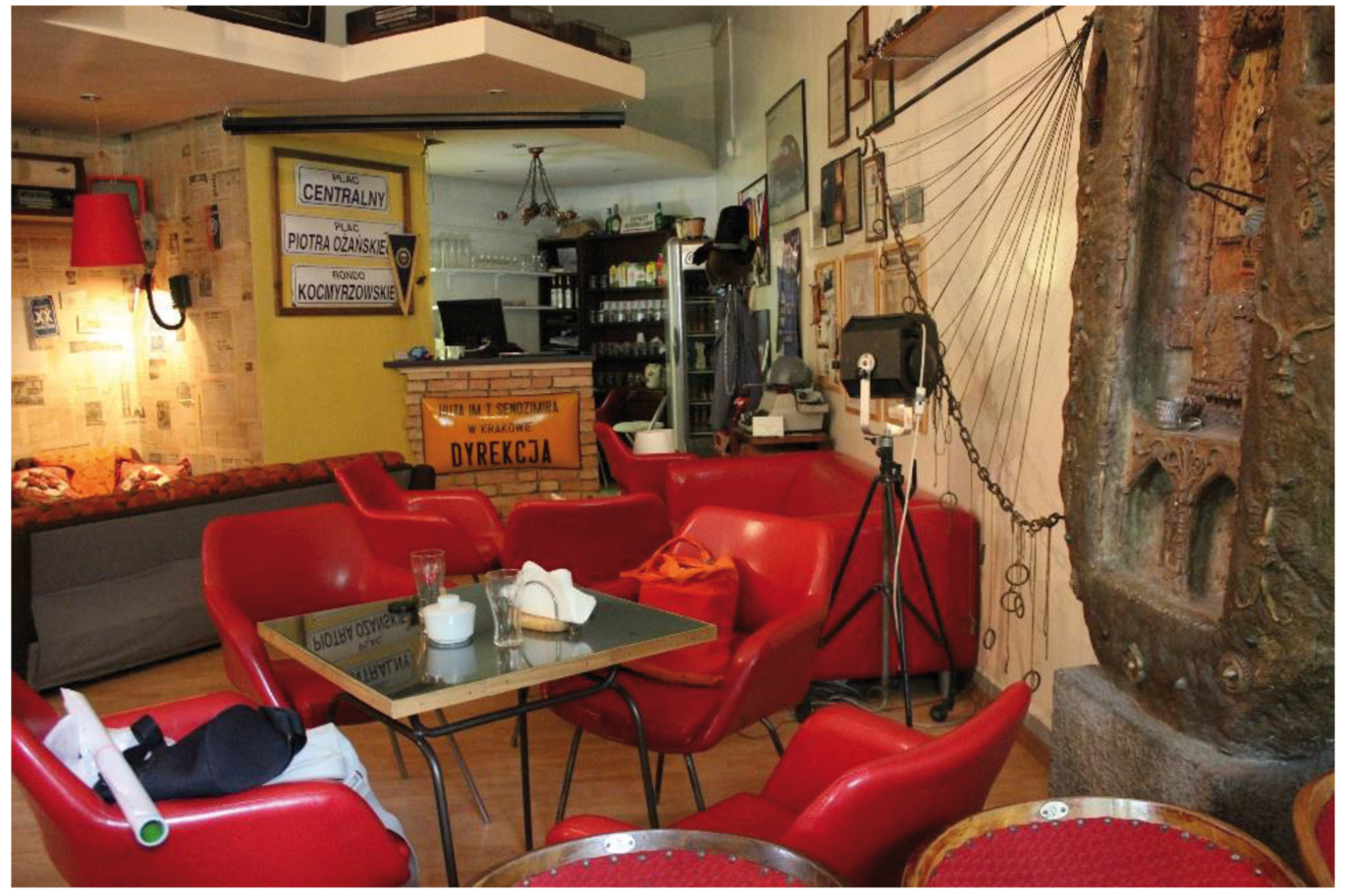

Beginnings have a “special mnemonic status” as they provide communities with a foundation; its roots and reasons for existence (Zerubavel 2003: 101). Nowa Huta’s beginning is close in time, within reach for the people who once built it, even if their numbers are thinning as the years go by. The arrivals and accomplishments of the builders – their sweat and toil and the town it produced – are often elevated in local life. But such memories are also challenged by narratives attesting to the harsh realities under which the town was made: the land expropriations of the farmers, undignified living conditions of the builders, and the propaganda campaigns which sought to gloss over human suffering in the name of ideology (Golonka-Czajkowska 2013; Pozniak 2014). Indeed, “repression, resistance and inefficiency” (Poźniak 2014: 16) have been the main themes in contemporary representations of Nowa Huta’s past; themes which fit neatly with dominant memory politics in Poland, and leave little room for “any positive memories of everyday life in socialist times” (Wawrzyniak 2021: 90). At the same time, rooms for positive remembrance are constantly carved out by Nowa Huta’s self-acclaimed supporters, of different ages and backgrounds, but united in their involvement on behalf of the district and its memories. In the following, I offer a closer look at how this support comes into being in Nowa Huta, departing from an informal gathering with a group of retired employees from the Bureau for Investments [Biuro Inwestycji], an agency which handled investments in the building sector in socialist Nowa Huta (Binek 2009). For the retirees from the agency, Nowa Huta is a home as well as a life achievement, through their work as engineers and architects with numerous high-rise blocks, school buildings and PRL-style shopping malls on their CV’s. In May 2011, I was invited by a few of them – who I will call Zbyszek, Ala, Ewa and Krystyna[6] in this text – to one of their recurrent gatherings. Unlike many other locally involved inhabitants of Nowa Huta, they were not interested in being interviewed. Instead, they suggested coffee and cakes at a café called C2 Południe [C2 South] after the original name of the housing area where it was located. C2 Południe was founded in 2010[7] by Paweł, a local activist in his thirties, and it reflected his fondness for the early years of Nowa Huta. Photos of Nowa Huta builders, news clips from the 1950 s and outdated street signs coexisted here with “retro” cups, radios and rickety cinema chairs, all of which had been sampled in a joint effort by Paweł and his older acquaintances. If memorabilia work as an “effective existential bridge” between different times (Zerubavel 2003: 43), then C2 Południe was certainly the place to be for those who wanted to stay emotionally attached to the PRL. To be sure, the café was not alone in its genre in Eastern and Central Europe, where nostalgic – or ‘neostalgic’, ironic-nostalgic (Veliknoja 2009: 32) – establishments mushroomed in the 2000 s (Main 2008). But C2 Południe still differed from other such venues that I have visited or read about, in its lack of hammers and sickles and other explicitly ideological symbols. Then again, the main purpose of the café was not, as Paweł explained, to sell socialism to tourists, but to provide a place for locals to socialize and remember.

If I had to capture the gathering in C2 Południe in one word, I would say: cheerful. When I arrived at the café, my hosts were already waiting at the entrance, amusedly informing me that Paweł was late as usual. I was immediately struck by how youthful they seemed, despite their age (ranging between 60 to 80+), in their ways of speaking and laughing. Soon enough, Zbyszek started flirting with all of us, in a joking manner, to which the ladies responded with smiles and sighs and rolling their eyes, while telling me: “this is how it has always been between us”. When Paweł finally arrived and brought us coffee and cakes, my hosts picked up a photo album which illustrated “that life was not all about work”. Indeed, judging from the pictures in the album, they had enjoyed themselves richly in the past, while celebrating name days, having dinners, and going on daytrips together. While musing around those memories they laughed, gesticulated and got involved in friendly mockery, to which Ala commented, in an assertion of continuity: “we are the best proof of how warm it has been between us”.

C2 Południe (Photo: Monica Collins)

A while into the gathering, Zbyszek started sharing bits and pieces from his arrival to Nowa Huta, in the early 1950 s, when he was on the run from the secret services, due to his activities the underground resistance, Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK)[8], during the war. In the turmoil of the building site, it was possible for “political enemies” of Stalinism to go under the radar in Nowa Huta and, in due time, recast their biographies in ideologically correct terms (Miezian 2004: 5). Seizing this opportunity, Zbyszek worked long hours at the building site, and eventually joined the ranks of the Communist Party. His female colleagues from the Bureau, who lacked personal memories from Stalinist Nowa Huta, listened quietly to his story and then stated that “the 1950 s were hard but many people survived thanks to Huta”. I write “but” in italics to underline its meaningful presence at that narrative junction, as well as on a few other occasions during our gathering, when the cheerful conversation was temporarily interrupted by darker memories, before it was quickly brought back to the overarching theme of the day: joyous life in the PRL. Aside from numerous anecdotes about celebrating International Women’s Day, Children’s Day and other significant occasions in Nowa Huta, my hosts were eager to let me in the social infrastructure behind such festivities. Did the ladies have to sign a paper confirming that they had received their annual Women’s Day gift from their employer? Where were such documents signed? Probably, they concluded, this was handled by the woman who was responsible for social relations at work – who they simply used to call socjalna (loosely, “the social lady”). My hosts went on explaining how useful the existence of such a lady was. Not only did she make sure that female employees were duly celebrated on International Women’s Day; she would also organize tickets to the theatre and mushroom-picking excursions for the employees and summer camps for their kids. Back then, my hosts said, the system “benefited all people, not only the bosses”, whereas contemporary Poland had moved in an undesired, “individualist” direction, with little room for the welfare provisions or the festivities associated with the PRL. However, while they appreciated the social infrastructure of the past, they were less embracive towards its political structure and ideological foundations. Pompous Party dignitaries were ridiculed, and memories of how the system could be “worked” were amusedly exchanged. My hosts were also careful to underline that Nowa Huta was never a socialist town, but a modern, industrial city which contributed to the development of postwar Kraków and Poland. This narrative, which reclaims the neighbourhood from the Soviet Union, from Stalinism and socialism, by asserting its national roots and significance, can often be heard among locally involved people in Nowa Huta.

It was symptomatic for our gathering at C2 Południe, that it ended with anecdotes about luck. Zbyszek initiated the topic, again, by mentioning a radio that he had once won, as well as a laundry machine and a bike. The ladies laughed upon hearing this and said that “only you could have such luck”, which prompted Zbyszek to share yet another story about a night job he had in his youth, where he would constantly fall asleep without his boss ever noticing. This anecdote triggered comments about the bright sides of life and then, suddenly, it was time for us to break up the gathering and head home, in an even more cheerful mood than when we had met a few hours earlier.

As I left C2 Południe, I was thinking that the gathering, with all the joyous memories it set in motion, enabled the continuation of practices that had glued my hosts together in the first place. The harder memories that also resurfaced were not allowed to steer the meeting away from what seemed to be its raison d’être: to recapture and restore the best of the past. Then again, judging from what was shared among them, my hosts had enjoyed large portions of freedom in the PRL, which distinguishes them from less fortunate – or less implicated (Rothberg 2019) – compatriots. I do not know if they ever reflect further upon systemic ills and repressions faced (and possibly reproduced) by them and their compatriots, at other occasions. I can only conclude that when I met them, their mode of remembrance was one of nostalgia, charged by personal and positive memories from life in Nowa Huta. However, it is fair to assume, that my presence in the role of a researcher and curious visitor from another country, triggered and gave validity to their nostalgic musings. Nonetheless, it was obvious from the practices and stories of my hosts, that they fed on lived experience and engrained patterns of socializing.

According to some scholars (Angé & Berliner 2014; Todorova & Gille 2010), nostalgic practices can function as counterstrikes against undesired developments in the present. This mechanism was also at play at the café when my hosts bemoaned the disintegration of the social infrastructure of PRL and questioned contemporary inequalities and ideals of individualism. In the end, though, they were not particularly concerned with current affairs. If anything, they sought to correct or nuance dark depictions of Nowa Huta in circulation. With Paweł and me as their witnesses, and C2 Południe as a suitable backdrop, filled with that homegrown memorabilia, they asserted that their lives, in this former socialist flagship town, there and then, but also here and now, with their particular mnemonic baggage, had been good lives, deserving of a few hours of persistent praises – and well worth living.

If the past was (mainly) a source of joy and pleasure at C2 Południe, then things were more complicated elsewhere in Nowa Huta. When I leave the PRL-friendly pensioners and turn my attention to Solidarity members and steel workers, nostalgia will take on a different shape. This altered shape has to do with the vantage point from which nostalgia takes form. Next to the sociability of the past, Solidarity members often miss the agency they exerted in the opposition (Stasik 2012, Wawrzyniak 2021). With that agency came expectations which were shattered or at least not sufficiently fulfilled after 1989, according to many of the movements working class members (Ost 2005). For them, revisiting the past means facing lost hopes and a diminished sense of agency, which makes the nostalgic involvement – that “search for continuity amid threats of discontinuity” (Davis 1979: 35) – less joyful and simple than at C2 Południe, where no shattered dreams discolored the beauties of the past. Put differently, it seemed easier to assert – or even: to perform – continuity among the PRL-friendly pensioners than among the Solidarity members I met, for whom the breach with the past, the discontinuity, was unsurmountable. But, as the following section will show, nostalgia needs not to be joyous or successful in its “pleas for continuity” (Davis 1979: 33), in order to be meaningful for people.

3 Sorrows for Solidarity

The cityscape of Nowa Huta is rich in memorials elevating the local legacy of resistance. In the very center of the district, there is a tribute to Solidarność in the shape of a Victory Monument, which was created in 1999 from waste material from steelmaking, at the initiative of union members. Initially placed within the terrains of the steel plant, the monument was moved to the heart of Nowa Huta in 2005, whereby it became accessible to locals and – most importantly, I was told – to those Solidarity members who had lost their jobs following the privatization of the plant. In the vicinity of the monument, Plac Centralny (“Central Square”) is located; a place which has officially been carrying Ronald Reagan’s name since 2006, to “honor” his role in “subjugating Communism”, as a politician put it (Kozik & Radłowska 2008). The oppositional heritage is also recognized in street names and memory plaques, as well as in cultural production – songs, exhibitions, historical reconstructions. The multitude of tangible Solidarity memories, and the ways in which they are actively approached – decorated with flowers, visited by school groups, commemorated – shows their strength and status as inscribed cultural memories (Connerton 1989; Assmann 2008), cared for from below as well as from above and destined for longevity. However, while sites of memory like these aim at preserving the past, they can also come to symbolize its pastness, as the times and the deeds that they highlight are no longer actively present when societies decide to monumentalize them (Connerton 2009). Or, in the much-cited words of Nora (1989: 7): “We speak so much about memory because there is so little left of it”.

Never was the pastness of the past more evident to me than during an interview with seven steel workers, all men and most of them retired, who had joined Solidarność in the 1980 s and were still members when we met, in June 2012. While not entirely in-tune with each other on every single political issue, my interlocutors were generally positive to the politics of memory enforced by Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) which, at the time of the interview, was the main oppositional force to the ruling liberal-conservative party Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO). Our meeting took place at the headquarters of the steel plant, in an elegant conference room, which used to belong to the Communist Party, until it ended up in Solidarity hands after 1989. This takeover was symbolically manifested in an abundance of memorabilia: medals, pictures, pennants. Surrounded by these tokens of victory, I was not expecting the narrative of defeat which unfolded shortly after our meeting had begun[9]. Throughout the interview, I was provided with a depiction of a treacherous post-socialist Poland, in which the inequalities of the old system had prevailed, due to a lenient stance towards the former leadership, and the ways in which some of its members “enriched” themselves in the early years of privatization. For many of Solidarity’s workers, in contrast, dreams of a better future and a higher standard of life, comparable to that in the West, were smashed after the arrival of “that great democracy which meant to layoff, to layoff [people]”, as one of the men sourly put it. Throughout the interview, he and his friends expressed sympathies with colleagues who had lost their jobs following the cuts at the steel plant.

No later than yesterday, I met four colleagues here, who had lost their jobs [...]. They said to me ‘if we would have known in [19]80 and [19]88 that this situation would occur, then none of us would have lifted a finger’, they showed like this [lifts his finger up in the air]. Those people were dedicated members of Solidarity [...]. The people who fought for and won freedom (wywalczyli wolność), later became the first victims of this freedom.

Similar sentiments would color our entire meeting, in which the struggle for and the loss of freedom was central. Along with layoffs, the loss was related to material deprivation, economic instability, unbridged gaps with the West, and other signs of falling short and losing out. But it was also attributed to the arrival of what was viewed as a distorted kind of freedom, epitomized by individualism, consumerism, wavering patriotism, and sexual liberalization. Such views can be understood in the light of the non-individualist nature of the Solidarity movement, whose struggles aimed at liberation from the authoritarian state and not from other collective entities, such as the church and the nuclear family, which were seen as constitutive of the Polish nation (Brier 2009).

The Solidarity Monument in Nowa Huta (photo Monica Collins)

Upon sharing their frustrations with post-socialist developments, my interlocutors told me about the unbroken solidarity between them, which dated back to the advent of the oppositional movement. Back then, they said, when the interview finally took a turn for better, a “flock instinct” had driven them to the barricades, where they had experienced “huge hope [...] that they will see something new, something better, that they will not be enslaved”. That time was “the most beautiful time in life”, a time of collective political reckoning. Practicing solidarity together, on a day-to-day basis, at work, in church and on the streets of Nowa Huta, instilled them with a sense of hope, communality and agency (cf. Kowalska 2020; Kubik 1994; Stasik 2012; Wawrzyniak 2021), all of which are ingredients in what Turner (1982; see also Kubik 1994) has called communitas. Communitas are characterized by tight, unconstrained human bonds, which arise in liminal times “betwixt and between” (Turner 1982: 113) the dissolution of old social structures and the formation of new ones, when people are temporarily freed from earlier upheld roles and duties. While such bonds easily lend themselves to retrospective idealization, my point here is not to assert their exact historical truthfulness, but to underline that they can provide people with “meaningful guidelines” (Turner 1986: 36) that are useful beyond the tumultuous circumstances in which they come into being. For my interlocutors at the steel plant, those guidelines seemed fairly straightforward. The less solidarity to be found in present-day Poland, the bigger the need to upkeep the values and bonds that were formed at the barricades in the 1980 s. Throughout the interview, I was constantly provided with new observations of the social disintegration around them; the crumbling of relations between neighbors, the political divisions at top and bottom, and the weak understanding of the memories and ideals of Solidarity among people. In light of this, the camaraderie of the men at the steel work, and their local memory work under the banner of Solidarność, served as a token of their continuous care for each other and for their wider habitat. On their wish-list when we met was a venue where they would display memorabilia from the Solidarity years so that “Nowa Huta could be proud”; a wish which later resulted in co-arranging exhibitions at Muzeum PRL:u. At the time of the interview, some of my interlocutors were busy preparing a two-day long commemoration dedicated to the underground structures in Nowa Huta, which were established in 1982, following the enforcement of Marial Law in Poland on December 13th, 1981[10]. Aimed at curbing the opposition and – according to the legitimization of the Communist Party – averting the (alleged) threat of a Soviet Invasion (Paczkowski 2005), Martial Law resulted in the criminalization of Solidarity and the imprisonment of many of its leading members. Those who remained on free foot, in Nowa Huta, quickly formed an underground organization – Tajna Komisja Robotnicza Hutników (“The Secret Comission of Steel Workers”, TKRH) – along with a support network for families of imprisoned members. The 30th Anniversary of the TKRH included a memorial to honor deceased friends and resistance members; an event which illuminated the relation between memory and care within this milieu in Nowa Huta.

Taking place at the Grębałów Cemetery in Nowa Huta, the memorial started off by the grave of Bogdan Włosik, who was only 20 years old when the police shot him, on October 13th, 1982, during a monthly protest against Martial Law. He died the same day in the hospital. Thirty years later, participants in the commemoration gathered by his resting place, solemn, silently waiting for the ceremony to commence. Next to some of the steel workers I had gotten to know earlier and their colleagues, Włosik’s parents were also present, as was the local TV station, and a photographer belonging to the younger generation of Nowa Huta activists. I greeted my acquaintances quietly and made sure to keep a respectful distance as we approached the grave. They had invited me to the memorial, but I still felt somewhat misplaced in this intimate crowd of people who had gathered here to mourn and remember together. When the praying, singing and laying of a wreath was initiated, my worries slowly began to wither. As we continued our walk to the next grave, I noticed that the atmosphere had lightened up. Two men in front of me began joking about their friend further ahead, who was allegedly the most devout among them. Shouldn’t he be responsible for the praying? In the end, the participants carried out this task together, but I still took note of this cheerful exchange, along with other moments of joy and laughter which I picked up as we walked from grave to grave, friend to friend. At our final destination, the atmosphere turned solemn again, under the influence of the memories resurfacing here, where a dear friend was buried, under a wooden cross, which epitomized the good, godly, and simple life that he led. A friend, we were told, who always lent a helping hand, put others before himself, and who was therefore an embodiment of the ideal of solidarity.

Ricœur (2004: 132) writes that close interpersonal relations “add a special note concerning the two events that limit human life, birth or death”. Unless we are famous, those events are not particularly noteworthy to society at large, but close friends and relatives “will mourn our passing.” In the thinking of Butler (2004: 28), mourning casts a light on the “sociality of embodied life, the ways in which we are [...] implicated in lives that are not our own”. Among the Solidarity members I found an awareness of that implication, and a desire to make it explicit through the care of the dead and of the living which animated their memorial. At the cemetery, it was as though the disruptions between past and present, so tangible in this milieu, were temporarily put on hold, as continuities – lasting bonds, lasting ways of being together – made their existence known. Obviously, the communality born under the banners of Solidarność in the 1980 s could not be fully reinstated here – lost friends and hopes could not be brought back – but its continuous validity was nonetheless manifested through the collective mourning on that day and from those interruptive moments of laughter and joy among friends.

For all the differences between the two milieus of C2 Południe and the Solidarity meetings, both groups draw on engrained ways of socializing and caring for each other, and on similar concerns about the afterlives of their cherished memories; concerns which have proved to be productive as they help bring about memorials and nostalgic cafés and also provide younger generations with mnemonic material with which to create their own narratives and initiatives. The fruits of such activity can be seen in emerging lifestyles and grassroots initiatives in contemporary Nowa Huta, often initiated by local activists who came of age towards the end of PRL.

4 Falling in Love with the Ballast. Remembrance, Place Care and Local Lifestyles in Nowa Huta

The decision to make Ronald Reagan the patron of Plac Centralny in Nowa Huta (see Section 2), met with discontent among many inhabitants, including local politician and activist Maciej Twaróg,[11] who decided to petition against the name change. During our interview, Maciej emphasized his sympathy with the American president, including his views on abortion, anticommunism and market economy. But none of that made this “nice dude”, who had “overthrown communism together with the Pope”, a fitting patron for Plac Centralny: “I say nooo, we don’t like those things on the living organism of Nowa Huta”. In the end, the petitioning resulted in a compromise, where Reagan’s name was added next to the old one instead of erasing it, although, as Maciej underlined, people would still use the original name, thereby undermining the political efforts to turn this local place into a memorial of anticommunist struggle.

The Reagan issue was indicative of the frustrations felt in Nowa Huta in the early 2000 s, at the predicament of the neighborhood. Not everyone saw eye to eye on issues regarding place names, memory politics and local development, but most of the people I talked to agreed that the transformation process had taken a toll on Nowa Huta. After 1989, large scale unemployment was experienced for the first time by the inhabitants, in combination with other pains of the era: poverty, inequality, social exclusion. To that, many people added sorrowful observations of a deteriorating cityscape where the elegant venues of the yesteryears – whereof the fashion store Moda Polska and the book salon KMPiK (Klub Międzynarodowej Prasy i Książki, International Press and Book Club) were most often cherished – had been wiped out by innumerous second-hand stores, banks and pharmacies. Apparently, system change did not mean the arrival of glossy stores and exciting opportunities to Nowa Huta, but that did not alter many of my interlocutors overall positive views on the turn of events. What they were bemoaning was the fate their own neighborhood after 1989, and its image which was increasingly suffering from its entanglement with the old, discarded system (Majewska 2007; Poźniak 2014). If identity is formed at the “edge” between “how others see you, and how you see yourself” (Sennett 2001: 177), then that edge widened into a gap in post-socialist Nowa Huta, which – as many of my interlocutors put it – triggered a need to “do something” for their tarnished habitat and its troublesome memories.

A small part of Plac Centralny im. Ronalda Reagana (photo Monica Collins)

Graffiti depicting Nowa Huta with the text “Nowa Huta, a free town” (photo Agnes Malmgren)

In the narratives of those who grew up in Nowa Huta and later got involved in local life, memories from childhood occupy a special place. Anna, for instance, pointed out links between her current job at a cultural institution, where heritage preservation was one her responsibilities, and the ways in which she used to roam around Nowa Huta in childhood and adolescence. Born here in the 1960 s, she experienced the expanding neighbourhood as a “building site theatre” where children got to “see, touch and feel matter”. This “spectacle”, she wrote in a local publication, would “remain with them for the rest of their lives as a dynamite in their hearts” (Piekarska-Duraj 2005). When I met Anna, she added more “amazing memories” to her story about an upbringing characterized by “community, and such freedom”, when children would be running around in flocks between yards and streets, free to do whatever they pleased so long as they were “home before dawn”. For those who grew up a few decades after Anna, in the 1980 s, happy childhood memories were usually interrupted – literally – by the political turmoil of the era. Some found this exciting, while others remember fearing war at their doorstep, as they let me in on the protests and the tanks and the police brutality which they had encountered on their adventures around Nowa Huta. This experience, according to Maciej, led to political awakening among the younger generations in the neighbourhood, who “grew up faster” than children elsewhere: “We lived in Huta, we were from Huta, so all of this took place in front of our eyes”, he said.

Childhood memories from Nowa Huta are characterized by their collective, as well as their material and embodied, nature. They are about “us”, not “me”, and they are solidly anchored in the place – its streets, buildings – and remembered through the movements and sensations brought out in these localities (Connerton 2009). While the friendships from those days have not always survived the passing of time, the memory of them is significant in narratives about continuous caring for local life. Following Willim’s observations on the revival of post-industrial places (2008), there seems to be a resemblance between the ways in which people played in the neighbourhood as children and how they later came to engage with it creatively, as adults. It is important to underline that neither the cherished childhood memories, nor the involvement discussed here, are unique for Nowa Huta. Rather, this involvement, and its biographical anchoring, can be seen as a local variation of a broader tendency in Eastern and Central Europe, where similar urban grassroot initiatives of have mushroomed in the last decades, as a response to the large-scale transformations of cityscapes after 1989 (Jacobsson 2015).

“Nowohucianka” bottled water (photo Agnes Malmgren)

Some of those who grew up in Nowa Huta in the 1980 s were surprised when they learned about the existence of negative images of Nowa Huta. For Paweł, the owner of C2 Południe (see Section 2), this insight correlated with starting secondary school in Kraków, where classmates volunteered with information about the problematic roots, polluting effects, and ill-mannered inhabitants of the formerly socialist town (Malmgren 2018; Janas 2020). The exposure to such stereotypes, and the ways in which they conflicted with personal experiences of growing up in a “normal” or “amazing” place, depending on who was speaking, fed into the formation of locally distinct lifestyles, which gave “material form to a particular narrative about self-identity” (Giddens 1991: 86). Staying put, instead of following the migration waves to the West or relocating to Kraków proper, became an important element of those lifestyles which, more or less overtly, challenged contemporary ideals of upward mobility (cf. Palska 2009). It is particularly worth noting how local lifestyles drew on their distinction from, and alleged in-difference to, the “uppity” or “hipstery” ways of life associated with Kraków. A few activists even initiated struggles for the reinstitution of Nowa Huta as an independent town (Magistrat Nowohucki 2012), whereas others simply underlined the distinct features and memories of their habitat. While I am yet to hear anyone in Nowa Huta mentioning the word class, I interpret such sentiments as expressions of belonging to a working-class district, which is defiantly praised for its ruggedness and dirty air and high-rise blocks and unpretentious inhabitants.[12] A telling illustration of how negative stereotypes are handled locally can be found in the launching of a brand of bottled water – Nowohucianka – by the activist group B2, which aimed at showing that the district had more to offer than “high-rise areas, slums and cheap pirate copies” (Grzanka, quoted in Kusy 2017) The Nowohucianka water is but one of many examples of the materiality of local lifestyles which are expressed through garments, paraphernalia and tattoos, often with a mnemonic twist, featuring anything from local Stakhanovites to Solidarity imagery.

Milkbars and neons in Nowa Huta (photo Agnes Malmgren)

Bourdieu has written about the human tendency to make “a virtue out of a necessity” (1984: 373). Studying local involvement in Nowa Huta means constantly witnessing virtue-making out of necessities since people here, as activist Adam Grzanka put it (2012), have been forced to “fall in love with the ballast, in order to get rid of it”. Or, as the title of a local podcast – Therapy through Identity – implies; identity work is a way of healing from the stigmas associated with the neighbourhood. In light of this, the mere act of cherishing Nowa Huta, including its blemishes, its ballast, is productive as a means to counter derogatory narratives in circulation. It is productive, in how it fuels the creation of new venues for remembrance and socializing, often drawing on the memories of the older generations, such as C2 Południe. And it is productive, in the tangible traces it leaves in the cityscape, as a result of proposals, or vocal discontent, from involved inhabitants, regarding place names, monuments and commemorations. I surmise that the neon lights that used to shine in the center of Nowa Huta in the PRL – and symbolize its modern aspirations (Brzostek 2007) – would not have resurfaced in public space if it was not for the restorative calls of local fans. Likewise, there would not be three milk bars in the very heart of the neighbourhood, if local inhabitants had not elevated them among themselves and popularized them through social media, and if the Nowa Huta Museum had not dedicated an exhibit to these cheap eateries, which are associated with the history of PRL.[13] Listening in on countless stories about milk bars, I learned not only about the meals and smells and cups and plates which had left lasting marks in people’s memories, but also about the special kind of sociability which could be found here, where people of different social standing would still eat next to each other (cf. Banaszewska 2014). To note that, and to keep visiting the milk bars, and to cherish their existence on a Facebook-page dedicated to these eateries, might seem to be a simple way of exercising place care. But it is also profound in how it contributes to the restitution of something – the smells, the sociability – which might otherwise have gotten lost in post-socialist Nowa Huta.

5 Concluding Remarks

In this article, I wanted to illustrate how memories made in Nowa Huta are cherished locally and how this act of cherishing rests on a sociability developed throughout the years among neighbours, friends, and colleagues in the daily places of their habitat, their localities, where they played as children or worked, struggled, and enjoyed themselves as adults. I believe that the concrete, material and relational anchoring of those memories, give them a specific solidity, which has proven useful in the wake of systemic transformation, when inhabitants in Nowa Huta had to face the question of how to deal with the neighbourhood’s past and how to imagine its future beyond PRL. In the remaking of the former socialist model town, which was initiated after 1989, memories proved to be important building-blocks.

I have to say, though, that writing about cherished memories and caring for place is a tricky business. It is easy to get swept away by the nostalgic or idealizing sentiments that accompany these phenomena. Therefore, it is important to underline that the empirical content of this article is made up from snapshots of people being busy presenting their pasts and their relations in a favorable light. That conflicts and cracks are not at the forefront of their endeavor, does not mean that the communities elevated by them are, or have always been, free from tensions within, aside from the distinctions drawn towards various significant others. While the offered snapshots fail to give a complete or representative account of memory work in Nowa Huta, they illustrate – instead – the significance of a particular mode of remembrance, through which the caring bonds among people, and between people and place, are revived, even restored, if only for short stretches of time. Is it not banal then, to reassert the claim, from case to case, that people keep caring for one another, and for their wider habitat, as they “always” have in Nowa Huta? There is probably a limit to how much care and nostalgia one can bring up as memory scholar, without running the risk of tilting the field too far in the opposite direction of the darker pasts which it has been preoccupied with so far. There is certainly a risk of silencing unjust and oppressive realities, when tuning in on people’s desires to bring back the beauties of the past, minus its darker features.

That having been said, the practice of cherishing memories in (and beyond) Nowa Huta deserves close attention, precisely because it is so tangible here. Even the most unassuming memories of care and friendliness do something important to the understanding of a time and place, and it is obvious that this effect is meaningful in Nowa Huta. It matters to the nostalgic pensioners that younger residents offer validity and cozy spaces for their experiences. It matters for the steel workers that they can lean on embodied memories of work, struggle, and cohabitation, as they count their losses after 1989. And to the younger generations, the memories of the older residents matter, when they decide to get involved on behalf of their disregarded neighborhood. Taken together, those moves in and for Nowa Huta, function as a correction to negative representations of its burdensome past. They also lay bare the lasting ties between people and place and thus – implicitly, at least – counter contemporary ideals of mobility and individualism.

References

Adjam, Maryam. 2017. Minnesspår: Hågkomstens rum och rörelse i skuggan av flykt. Huddinge: Södertörns högskola.Suche in Google Scholar

Åman, Anders. 1987. Arkitektur och ideologi i Stalintidens Östeuropa: Ur det kalla krigets skugga. Stockholm: Carlsson. Suche in Google Scholar

Angé, Olivia & David Berliner. 2014. Introduction: Anthropology of Nostalgia – Anthropology as Nostalgia. In Angé, Olivia & David Berliner (eds). Anthropology and nostalgia, 1–15. New York: Berghahn.10.3167/9781782384533Suche in Google Scholar

Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The human condition. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Assmann, Jan. 2008. Communicative and Cultural Memory. In Erll, Astrid & Ansgar Nünning (eds). Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, 109–119. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110207262.2.109Suche in Google Scholar

Banaszewska, Julia. 2014. Kraina mlekiem płynąca... O egalitaryzmie barów mlecznych wczoraj i dziś, Kultura Popularna 2(40). 152–163.Suche in Google Scholar

Bernhard, Michael & Jan Kubik. 2014. Roundtable Discord: The Contested Legacy of 1989 in Poland, In Bernhard, Michael & Jan Kubik (eds.). Twenty Years After Communism, 60–84. New York: Oxford Academic. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199375134.003.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Binek, Tadeusz. 2009. Służby inwestycyjne Nowej Huty. Kraków: Klub byłych pracowników Służb Inwestycyjnych.Suche in Google Scholar

Brier, Robert. 2009. The Roots of the “Fourth Republic.” Solidarity’s Cultural Legacy to Polish Politics, East European Politics and Societies 23(1). 63–85.10.1177/0888325408326790Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Brzostek, Błażej. 2007. Za progiem: Codzienność w przestrzeni publicznej Warszawy lat 1955–1970. Warszawa: Wydawnisctwo Trio.Suche in Google Scholar

Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious life: The powers of mourning and violence. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar

Chwalba, Andrzej. 2004. Kraków w latach 1945–1989. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie.Suche in Google Scholar

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How societies remember. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.10.1017/CBO9780511628061Suche in Google Scholar

Connerton, Paul. 2009. How modernity forgets. Leiden: Cambridge U.P.10.1017/CBO9780511627187Suche in Google Scholar

Conradson, David. 2003. Spaces of care in the city: the place of a community drop-in centre, Social & Cultural Geography 4(4). 507–525.10.1080/1464936032000137939Suche in Google Scholar

Davis, Fred. 1979. Yearning for yesteryear: a sociology of nostalgia. New York: Free Press.Suche in Google Scholar

de Certeau, Michael. 1984. The practice of everyday life Vol 1. Berkely: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Dilthey, Wilhelm. 1976. Selected writings. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P. Suche in Google Scholar

Ehn, Billy. 2007. ‘Hos mig kommer du alltid finnas kvar’: Monumentaliseringens uttrycksformer. In Frykman, Jonas & Billy Ehn (eds.). Minnesmärken. Att tolka det förflutna och besvärja framtiden, 341–365. Stockholm: Carlsson.Suche in Google Scholar

Feld, Steven & Keith H. Basso (eds). 1996. Senses of place, Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Frykman, Jonas & Nils Gilje. 2003. Being there: An introduction. In Frykman, Jonas & Nils Gilje (eds.). Being there: New perspectives on phenomenology and the analysis of culture, 7–53. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Golonka-Czajkowska, Monika. 2013. Nowe miasto nowych ludzi: Mitologie nowohuckie. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellonskiego.Suche in Google Scholar

Grzanka, Adam. 2012. Nowa Huta. Czyli jak pokochać balast, żeby się go pozbyć. Lodołamacz, 16.04.2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Gut, Dorota. 1993. Nowa Huta w świadomości jej mieszkańców. In Bujak, Jan & Zambrzycka-Steczkowska, Anna & Róża Godula (eds.). Kraków – przestrzenie kulturowe, 117–131. Krakow: Wydawnictwo Platan.Suche in Google Scholar

Jackson, Michael. 1996. Introduction: Phenomenology, Radical Empiricism, and Anthropological Critique. In Jackson, Michael (ed.). Things as they are: New directions in phenomenological anthropology, 1–51. Bloomington: Indiana U.P.Suche in Google Scholar

Jacobsson, Kerstin. 2015. Introduction: The development of urban movements in Central and Eastern Europe. In Jacobsson, Kerstin (ed.). Urban grassroots movements in Central and Eastern Europe, 1–32. Burlington: Ashgate Pub. 10.4324/9781315548845Suche in Google Scholar

Janas, Karol. 2020. Nowa Huta. Przestrzeń tożsamości. Warszawa: Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów.Suche in Google Scholar

Katriel, Tamar & Anna Reading (eds.). 2015. Cultural Memories of Non-Violent Struggles: Powerful Times. Basingstoke: Palgrave Maxmillan.Suche in Google Scholar

Keightley, Emily & Michael Pickering. 2012. The mnemonic imagination: Remembering as creative practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137271549Suche in Google Scholar

Kowalska, Beata. 2020. Nowa Huta 1988 migawki z utopii. Gdańsk: Europejskie Centrum Solidarności.Suche in Google Scholar

Kozik, Ryszard & Renata Radłowska. 2008. Nie wolno zapominać o historii, Gazeta Wyborcza, 31.01.2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Kubik, Jan. 1994. The power of symbols against the symbols of power: The rise of Solidarity and the fall of state socialism in Poland. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State U.P.Suche in Google Scholar

Lebow, Katherine. 2013. Unfinished Utopia: Nowa Huta, Stalinism, and Polish Society, 1949–56. Ithaca: Cornell U.P.10.7591/cornell/9780801451249.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Magistrat Nowohucki. 2012. Nowa Huta Wolne Miasto. [blog post], URL: http://magistratnowohucki.pl/#nowa_huta_wolne_miasto (last accessed: 06.03.2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Main, Izabella. 2008. How is Communism Displayed? Exhibitions and Museums of Communism in Poland. In Sarkisova, Oksana & Peter Apor (eds.). Past for the Eyes. East European Representations of Communism in Cinema and Museums after 1989, 371–400. Budapest: Central European U.P.10.1515/9786155211430-015Suche in Google Scholar

Majewska, Ewa. 2007. Nowa Huta jako projekt utopijny: Szkic o wyobraźni politycznej. In Kaltwasser, Martin & Majewska, Ewa & Kuba Szreder (eds.). Futuryzm Miast Przemysłowych, 195–209. Kraków: Korporacja Ha!art. Suche in Google Scholar

Malmgren, Agnes. 2012. “Huta is the air that I breathe”. Belonging, Remembering and Fighting in the Story of Maciej Twaróg. In Bernsand, Niklas & Barbara Törnquist Plewa (eds.). Painful pasts and useful memories Remembering and forgetting in Europe, 29–49. Lund University: CFE Conference Papers Series, 5.Suche in Google Scholar

Malmgren, Agnes. 2018. Efterklang/efterskalv: Minne, erkännande och solidaritet i Nowa Huta. Lund: Lund University.Suche in Google Scholar

Miezian, Maciej. 2004. Kraków’s Nowa Huta. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Bezdroża.Suche in Google Scholar

Milligan, Christine & Janine Wiles. 2010. Landscapes of care, Progress in Human Geography 34(6). 736–754.10.1177/0309132510364556Suche in Google Scholar

Nora, Pierre. 1989. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire, Representations 26. 7–24.10.2307/2928520Suche in Google Scholar

Ochman, Ewa. 2013. Post-Communist Poland – Contested Pasts and Future Identities. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203550830Suche in Google Scholar

Ost, David. 2005. The defeat of Solidarity. Anger and politics in postcommunist Europe. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell U.P.10.7591/9781501729270Suche in Google Scholar

Ost, David. 2009. The Invisibility and Centrality of Class after Communism, International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 22(4). 497–515.10.1007/s10767-009-9079-3Suche in Google Scholar

Paczkowski, Andrzej. 2005. Pół wieku dziejów Polski: 1939–1989. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.Suche in Google Scholar

Palska, Hanna. 2009. Badania nad stylami życia. Z przeszłych i obecnych badań terenowych. In Bogunia-Borowska, Małgorzata (ed.). Barwy codzienności. Analiza socjologiczna, 143–156. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe SCHOLAR.Suche in Google Scholar

Piekarska-Duraj, Łucja (ed.). 2005. nowa_huta. Księga uwolnionych tekstów. Kraków: Małopolski Instytut Kultury.Suche in Google Scholar

Porter, Brian. 2014. Poland in the modern world: beyond martyrdom. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Poźniak, Kinga. 2014. Nowa Huta: generations of change in a model socialist town. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.10.2307/j.ctt9qh8c3Suche in Google Scholar

Ricœur, Paul. 2004. Memory, history, forgetting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Rigney, Ann. 2018. Remembering hope: Transnational activism beyond the traumatic, Memory studies 11(3). 368–380.10.1177/1750698018771869Suche in Google Scholar

Rothberg, Michael. 2019. The implicated subject: Beyond victims and perpetrators. Stanford, California: Stanford U.P.10.1515/9781503609600Suche in Google Scholar

Schudson, Michael. 1989. The Present in the Past versus the Past in the Present, Communication 11(2). 105–113.Suche in Google Scholar

Sennett, Richard. 2001. Street and office: Two sources of identity. In Hutton, Will & Anthony Giddens (eds.). On the edge: Living with global capitalism, 175–190. London: Vintage.Suche in Google Scholar

Sindbæk Andersen, Tea & Jessica Ortner. 2019. Introduction: Memories of joy, Memory Studies 12(1). 5–10.10.1177/1750698018811976Suche in Google Scholar

Stasik, Agata. 2012. Solidarność w perspektywie własnej biografii w opowieściach robotników, Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Sociologica 41. 195–213.10.18778/0208-600X.41.12Suche in Google Scholar

Stenning, Allison. 2000. Placing (post-) socialism: The making and remaking of Nowa Huta, Poland, European Urban and Regional Studies 7(2). 99–118.10.1177/096977640000700201Suche in Google Scholar

Stenning, Allison. 2005. Where is the post-socialist working class? Working-class lives in the spaces of (post-) socialism, Sociology 39(5). 983–999.10.1177/0038038505058382Suche in Google Scholar

Stenning, Allison & Smith, Adrian & Rochovská, Alena & Dariusz Świątek (eds.). 2010. Domesticating neo-liberalism. Spaces of economic practice and social reproduction in post-socialist cities. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.10.1002/9781444325409Suche in Google Scholar

Stowarzyszenie Sieć Solidarności. n.d. O nas. [homepage], accessible at: Stowarzyszenie Sieć Solidarności, URL: sss.net.pl, (last access: 10.06.2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Tannock, Stuart. 1995. Nostalgia critique, Cultural Studies 9(3). 453–464.10.1080/09502389500490511Suche in Google Scholar

Till, Karen. 2012. Wounded cities: Memory-work and a place-based ethics of care, Political Geography 31(1). 3–14. 10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.10.008Suche in Google Scholar

Todorova, Maria Nikolaeva & Zsuzsa Gille (eds.). 2010. Post-communist nostalgia. New York: Berghahn Books.10.3167/9781845456719Suche in Google Scholar

Tronto, Joan C. 2013. Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and justice. New York: New York U.P.Suche in Google Scholar

Turner, Victor. 1982. From ritual to theatre: the human seriousness of play. New York: Performing arts journal publ.Suche in Google Scholar

Turner, Victor. 1986. Dewey, Dilthey and Drama: An Essay in the Anthropology of Experience. In Bruner, Edward & Victor Turner (eds.), The Anthropology of Experience, 33–45. Urbana/Chicago: University of Illinois Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Velikonja, Mitja. 2009. Lost in transition: Nostalgia for socialism in post-socialist countries, East European Politics and Societies 23(4). 535 –551.10.1177/0888325409345140Suche in Google Scholar

Wawrzyniak, Joanna. 2021. ›Hard Times but Our Own‹. Post-Socialist Nostalgia and the Transformation of Industrial Life in Poland, Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 18(1). 73–92.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiles, Janine & Ranmalie Jayasinha. 2013. Care for place: The contributions older people make to their communities, Journal of Aging Studies 27(2). 93–101.10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.001Suche in Google Scholar

Willim, Robert. 2008. Industrial cool: om postindustriella fabriker. Lund: Faculty of Humanities, Lund University.Suche in Google Scholar

Wilk, Hubert. 2010. Piotr Ożański – prawda o Człowieku z Marmuru: przyczynek do refleksji nad losami przodowników pracy, Polska 1944/45–1989: Studia i materiały 9. 31–45.Suche in Google Scholar

Wüstenberg, Jenny. 2023. Towards a Slow Memory Studies. In Kaplan, Brett (ed.), Critical Memory Studies: New Approaches. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9781350233164.ch-4Suche in Google Scholar

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2003. Time maps: Collective memory and the social shape of the past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226924908.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Fieldnotes

Fieldnote from gathering at C2 Południe. 27.05.2011.Suche in Google Scholar

Fieldnote from Grębałów Cemetery. 21.09.2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Cited interviews

Anna. 24.07.2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Group interview with Solidarity members. 26.06.2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Maciej. 05.05.2010.Suche in Google Scholar

Paweł. 27.05.2011.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Themenschwerpunkt / Main Topic: Decentering Polish Memory: Parallax Perspectives on East-Central European Pasts

- Introduction: Parallax Perspectives on Polish Pasts

- Cherishing the memories you have

- Backstories of Commemoration: Memoryscapes of Polish Galicia

- Memory-making and Vampire-hunting: A Hauntological Study of the “Recovered” Pomerania in the 1950s

- City under (re)construction: Architectural narrations as a foundation story of a city with a broken cultural continuity

- “A Larger Realm of Reality”: Jewish Women in Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob (2014)

- Weitere Artikel zum Polnischen / Further Articles on Polish

- Zwischen Verfassungspatriotismus und nationalem Trauer-Patriotismus im Polnischen

- Sight, Knowledge, Variety, and Correction: Kasijan Sakovyč’s Perspektywa and Related Book Titles

- Sprachliche Selbstpositionierung auf X unter den Wählern rechtsgerichteter Parteien in Polen und Deutschland im Europawahlkampf 2024

- Buchbesprechung

- Aspektvariation im Polnischen

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Themenschwerpunkt / Main Topic: Decentering Polish Memory: Parallax Perspectives on East-Central European Pasts

- Introduction: Parallax Perspectives on Polish Pasts

- Cherishing the memories you have

- Backstories of Commemoration: Memoryscapes of Polish Galicia

- Memory-making and Vampire-hunting: A Hauntological Study of the “Recovered” Pomerania in the 1950s

- City under (re)construction: Architectural narrations as a foundation story of a city with a broken cultural continuity

- “A Larger Realm of Reality”: Jewish Women in Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob (2014)

- Weitere Artikel zum Polnischen / Further Articles on Polish

- Zwischen Verfassungspatriotismus und nationalem Trauer-Patriotismus im Polnischen

- Sight, Knowledge, Variety, and Correction: Kasijan Sakovyč’s Perspektywa and Related Book Titles

- Sprachliche Selbstpositionierung auf X unter den Wählern rechtsgerichteter Parteien in Polen und Deutschland im Europawahlkampf 2024

- Buchbesprechung

- Aspektvariation im Polnischen