Head repositioning accuracy is influenced by experimental neck pain in those most accurate but not when adding a cognitive task

-

Steffan Wittrup McPhee Christensen

Abstract

Background and aims

Neck pain can impair perception of cervical movement, but how this is affected by attention is unknown. In this study, the effects of experimental neck pain on head repositioning accuracy during standardized head movements were investigated.

Methods

Experimental neck pain was induced by injecting hypertonic saline into the right splenius capitis muscle in 28 healthy participants (12 women). Isotonic saline was used as control. Participants were blindfolded while performing standardized head movements from neutral (start) to either right-rotation, left-rotation, flexion or extension, then back to neutral (end). Movements were triplicated for each direction, separated by 5-s, and performed with or without a cognitive task at baseline, immediately after the injection, and 5-min after pain disappeared. Repositioning accuracy was assessed by 3-dimensional recordings of head movement and defined as the difference between start and end position. Participants were grouped into most/least accurate based on a median split of head repositioning accuracy for each movement direction at baseline without the cognitive task.

Results

The most accurate group got less accurate following hypertonic injection during right-rotation without a cognitive task, compared with the least accurate group and the isotonic condition (p < 0.01). No group difference was found when testing head repositioning accuracy while the participants where distracted by the cognitive task.

Conclusions

Experimental neck pain alters head repositioning accuracy in healthy participants, but only in those who are most accurate at baseline. Interestingly, this impairment was no longer present when a cognitive task was added to the head repositioning accuracy test.

Implications

The results adds to our understanding of what factor may influence the head repositioning accuracy test when used in clinical practice and thereby how the results should be interpreted.

1 Introduction

Neck pain is a common condition in the general population [1] and individuals with neck disorders often display decreased spatial control (cervical kinaesthesia) of the head and neck compared with healthy controls [2], [3]. Altered cervical kinaesthesia has been suggested to be due to altered proprioceptive feedback from neck muscles [4], [5], [6], which is in line with findings of altered proprioceptive function and muscle activity [7] and atrophied neck muscles [8], [9] in neck pain populations. Furthermore, disturbed cervical kinaesthesia may cause a sensory mismatch when combining information from cervical proprioceptive afferents with other sensory sources (e.g. visual and vestibular system), which has been suggested as the underlying reason for clinical symptoms of decreased postural control [10], [11], unsteadiness and dizziness [4] as observed in neck pain populations. Particularly, altered cervical kinaesthesia in the horizontal plane has been suggested to be related with symptoms of dizziness, impaired balance, and self-reported pain and disability in people suffering from neck pain [12].

One way of assessing cervical kinaesthesia is by testing head repositioning accuracy, either in the horizontal or vertical movements planes, or by using more complex movement patterns [2], [13], [14], [15], [16], also known as a test of joint positioning error [4], [17]. Interestingly, although sensory input from the muscles are thought to play an important role in cervical kinaesthesia [14], [18], not many studies have actually investigated this directly. While several studies have found differences in head repositioning accuracy (HRA) in clinical neck pain compared to healthy participants [2], [3], this only shows that neck pain is linked to altered head repositioning accuracy, but cannot tell us if muscle pain is to blame for this discrepancy between groups. In fact, only one study by Malmstrom et al. [19] has investigated HRA after experimental neck muscle pain (injection of hypertonic saline) in healthy participants and reported this to be decreased ipsilateral to the injection. While the literature suggests that the proprioceptive input from neck muscles plays an important role when testing head repositioning accuracy, no one so far has investigated the influence of a cognitive task. This would be of great interest as, in daily life, spatial control of the head/neck is commonly performed in a context with “disturbance” from cognitive tasks (e.g. work tasks, engaging in conversation, shopping etc.), but the specific effect of such “disturbances” on clinical tests are not known.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of unilateral experimental neck pain, as well as the influence of a cognitive task, on HRA in healthy participants. It was hypothesised that experimental neck pain would decrease head repositioning accuracy, and that this would further deteriorate with the introduction of a cognitive task. It was expected that movements ipsilateral to the experimental pain would be most affected. Furthermore, it was hypothesised that those most accurate during the HRA test would be most impacted by pain when compared to the least accurate participants.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from a university setting and were required to read, write and speak fluently in either English or Danish. After providing written informed consent, 28 healthy participants (12 women) were included in the study with a mean age of 24.7 (SD 3.6) years. The participants had a mean Neck Disability Index (NDI) score of 1.4% (SD 2.7) [20]. Inclusion criteria were healthy participants aged 18–50 years with normal, pain-free neck and shoulder range of motion. Furthermore, only right handed participants were included as previous studies have indicated that hand dominance may influence motor control; although this has mainly been shown during arm movements [21], it is unclear if this also influences neck movements as some axioscapular muscles exert force on the cervical spine [22]. Exclusion criteria were any neck or shoulder pain during the past 6 months, prior surgery in neck or shoulder, any self-reported neurological, rheumatological or musculoskeletal condition that might influence the results of the study, such as altered balance or dizziness, or pregnancy. A manual examination was undertaken to confirm the absence of symptoms radiating into the shoulder/arm/hand, reduced or painful neck or shoulder range of motion, or pain or soreness of the cervical spine. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (N-20120018).

2.2 Protocol

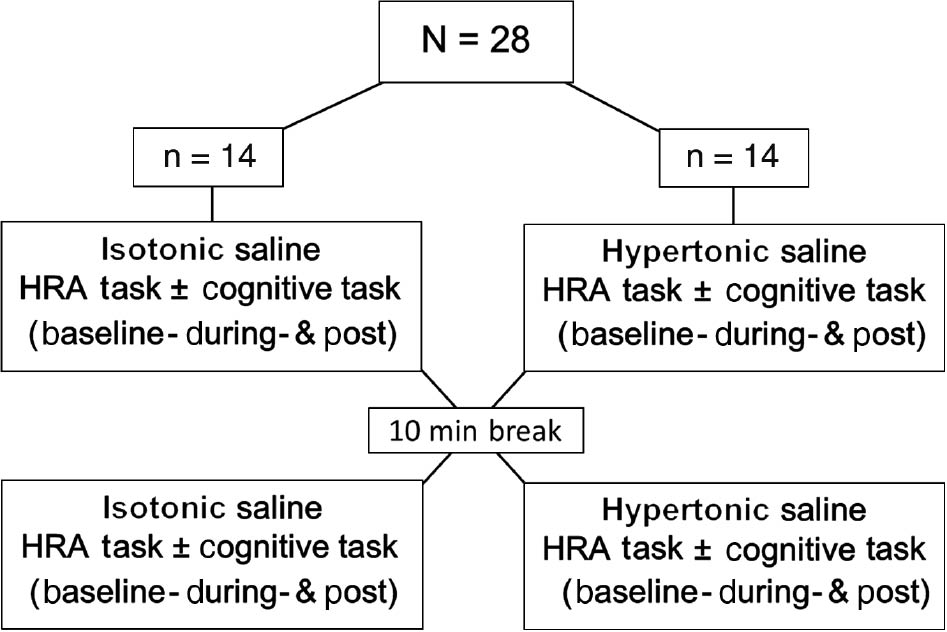

This was a randomised, single blinded (participants were blinded to the order of injections, as it may not have been possible to ensure blinding with regard to which injection was painful) cross-over study (Fig. 1). HRA recordings were performed by moving the head from a neutral head position into right or left rotation, extension or flexion, then returning to the start position. Three movements, separated by approximately 4–6 s, were conducted in each direction before moving on to the next direction. A break of 5–10 s between each movement direction was used to give instructions on the direction of the following movement. Movement speed was directed by the beep of a custom-made program (Aalborg University, Denmark) coming from a speaker placed approximately 3 meters in front of the participant: From a neutral/starting head position, 1st beep indicated when to start the active range of motion (AROM) with the head. A 2nd beep (2 s later) indicated when participants should be at full AROM, followed by a 3rd beep (2 s later) when the head should be back at neutral/starting position. Movement series were performed with and without a cognitive task, which consisted of simple multiplication equations (randomised from multiplication tables 2–9) such as 3×4. The equations were read out loud immediately after the 1st beep, during the first half of the HRA test, and the participants were instructed to answer before the sound of the 3rd beep. If a participant was unable to complete the movement before the last beep the trial was disregarded from the final analysis. The order of the tasks (movement with and without the cognitive task) was randomized in a balanced way between participants and was always the same for the individual participant throughout the study. After all movement directions were completed, the participant rated how difficult it was to perform the test series. A full series of movements (three movements in four different directions) were performed before, during and after experimental pain induced by injection of hypertonic saline. During the experimental condition following injection of hypertonic or isotonic saline, pain was monitored using a numeric rating scale and the post session was started 5 min after any potential pain had vanished. Following the post session, a 10 min break was given before the protocol was repeated with the alternate of the first injection (hypertonic or isotonic saline). The use of this randomized (order of injections and tasks) cross-over design aimed to control for any potential time or carry-over effects. The entire study took approximately 2 h per participant. Prior to starting the test-procedure, each participant had a familiarization session, where they tried moving in the different movement directions, guided by the beep sounds.

Study design: Head repositioning accuracy recordings were performed at Baseline, During (i.e. immediately after the injection of hypertonic or isotonic saline), and Post (i.e. 5 min after any potential pain had vanished). Ten minutes after the post recording, the procedure was repeated with alternate of the first injection (hypertonic or isotonic saline). The order of saline injections was randomized in a balanced way. During half the movements participants were distracted with a cognitive task (multiplication equations).

2.3 Experimental pain

Experimental neck muscle pain was induced by using a painful saline injection (0.5 mL hypertonic saline, 5.8%) or control injection (0.5 mL isotonic saline, 0.9%) into the right splenius capitis muscle at the C3 level [19], [23], [24], [25]. The isotonic saline injection controlled for both the needle insertion and the injected volume used in the hypertonic saline injection. The order of injections was randomised in a balanced way. The location and depth of the splenius capitis muscle was identified between the lateral border of the upper trapezius muscle and the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle using ultrasound imaging (Logiq S7 Expert from General Electrics) prior to injection. The needle was inserted into the middle of the muscle bulk where the injection was delivered.

2.4 Pain assessment

During the two injection conditions, neck pain intensity was rated on a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS, 0=no pain, 10=worst imaginable pain) [26] immediately after the injection and after completion of each movement direction (e.g. after three rotations to the right side etc.) to monitor if pain remained during the test. A mean NRS value across directions and tasks was used for further analysis. After the two injection conditions were completed, pain was rated every 30 s until any potential pain was gone, after which a 5 min break was implemented before the post-session was started. Quality of pain was assessed using words from the McGill pain questionnaire [27], [28] immediately after each of the two injections conditions. Area of perceived pain was recorded by body-chart drawings after each injection condition (hypertonic, isotonic) and the area was calculated using custom made Matlab script (v.2016a; The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.).

2.5 Head repositioning accuracy

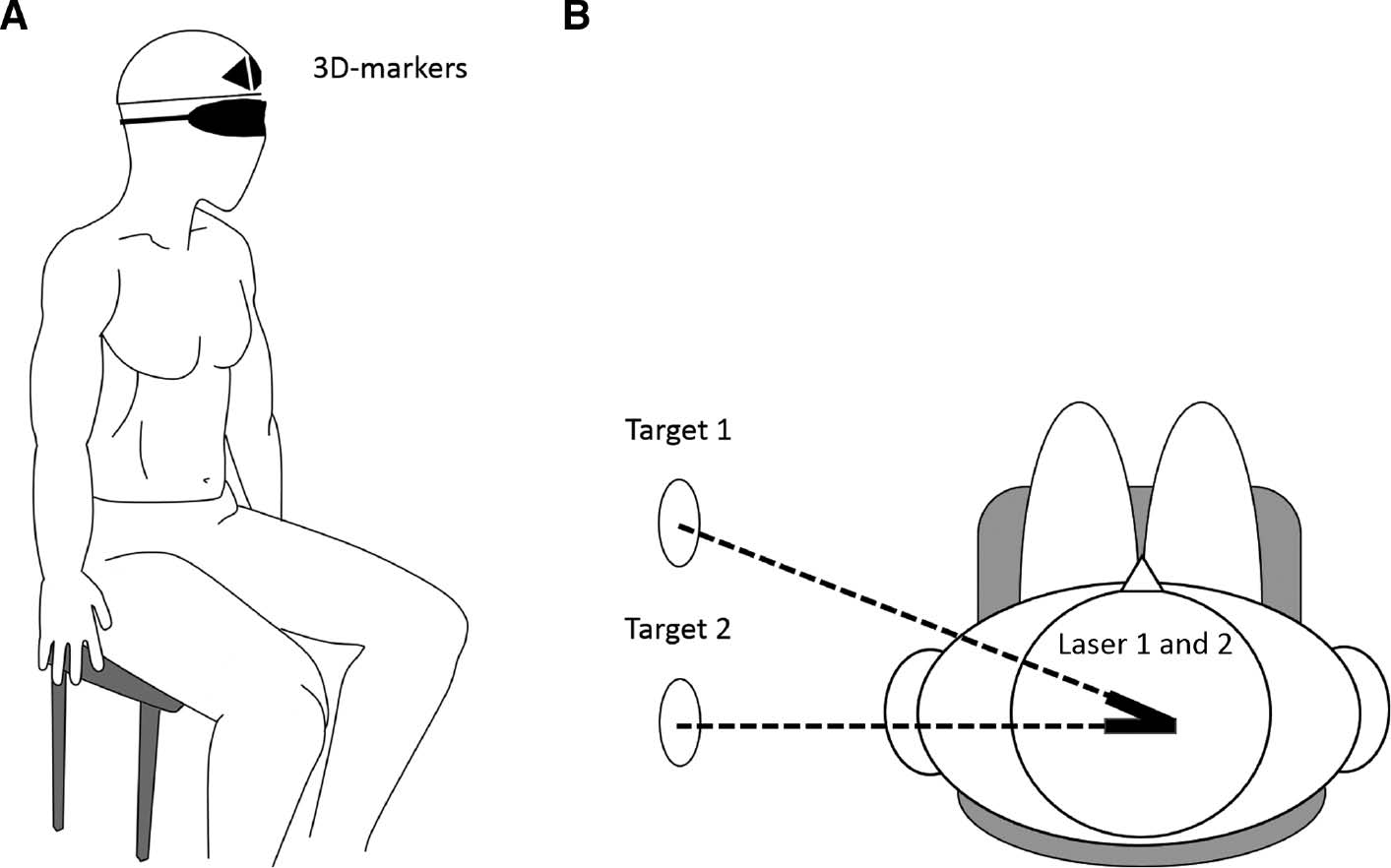

A digital 3D Optotrak certus motion capture system (Northern Digital Inc, Ontario, Canada) with markers placed on a helmet worn by the participant was used to measure spatial accuracy and obtain real time head movement data (Fig. 2A). Two clusters with three markers were placed on the front of the helmet and on each side of the midline of the participant’s nose, and the helmet was securely fastened with a chinstrap. Additionally, to ensure consistent placement of the helmet during the experiment, a strip of tape was placed between the helmet and the forehead. Each of the nine markers emitted its own frequency, which made it possible for the Optotrak software to instantly detect and uniquely identify its location in space. The system was calibrated at the beginning of each test-day.

Experimental setup showing a blindfolded participant with the helmet and 3D-markers (A) along with an aerial view of the setup (B).

The test procedure, as previously described under Protocol, was a modified version of that used by both Revel et al. [14] and Heikkila et al. [15] where participants were blindfolded to exclude the influence of visual input on the test. In order to limit the movement of the torso [29] participants sat on a chair in an upright and comfortable position using the backrest. The participants had their feet flat on the floor and their hands placed on their thighs. The blindfolded participants were instructed to identify and memorize their neutral head position, which was established as the starting reference position, at which the Optotrak was set to zero. In addition to the 3D-markers, the helmet was mounted with two laser pointers (the total weight of the helmet with markers and lasers was approximately 0.48 kg) pointing laterally toward the wall of the room (Fig. 2B). Once the neutral head position had been found by the participants, two target circles with a diameter of 5 cm, was placed on the wall with the centre marked by the laser pointer. From the neutral head position, the participants began the full active range of neck motion, and thereafter returned the head to the neutral position as accurately as possible. Three repetitions were performed in each of the four directions: right rotation, left rotation, extension and flexion. Following each movement, the test-leader corrected the participant’s head back to their self-chosen neutral position, guided by the two helmet-mounted lasers without providing the participant with any feedback regarding performance during the test. If no corrections were needed the test-leader still put the hands on the head of the participants and made a “correction” in order to ensure that each trial felt similar before commencing the next movement. To ensure familiarization before commencing the test, a test trial consisting of three movements in each direction was performed with and without a cognitive task (summation replaced multiplication for the cognitive task during the familiarization).

HRA was extracted and analysed using a custom made script for Matlab (v.2016a; The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) expressing the difference between the start and end position (absolute vector distance) of the head in mm for each movement. The mean of the absolute value for the three movement repetitions for each direction and task (with or without the cognitive task) was calculated using the markers on the helmet and used for further analysis. To investigate if those more accurate during the baseline measurements responded differently during the experimental conditions (hypertonic, isotonic) compared to those less accurate, a grouping factor was calculated for the analysis. The grouping factor was based on a median split of the average accuracy (most accurate; least accurate) of all participants during the two baselines (one before each experimental condition) for the non-cognitive task, as this was considered the optimal condition for movement accuracy. This grouping factor was calculated for each movement direction, as there are indications in the literature that an overall repositioning accuracy may not be representative for the accuracy for a specific movement direction [30].

The perceived difficultness of performing HRA was rated on a 6-item Likert scale (0=“no problems”, 1=minimally difficult’, 2=“somewhat difficult”, 3=“fairly difficult”, 4=“very difficult”, to 5=“unable to perform”) [23] after completing all movement directions.

2.6 Statistics

Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) in text and figures unless otherwise stated. NRS scores were compared for each experimental condition (hypertonic and isotonic injections) and cognitive task (without/with calculations) using a Wilcoxon test, while a Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare each condition and cognitive task between groups (most/least accurate). This was performed separately for each movement direction. The mean area of perceived pain was compared between the hypertonic and isotonic conditions using a Wilcoxon test. HRA data was normalized to baseline (100%). HRA at baseline (one before each experimental condition) for all directions, groups and tasks can be seen in Table 1. Normalized HRA data was analysed using a RM-ANOVA with task (with and without the cognitive task), saline (hypertonic and isotonic injection) and group (most and least accurate) as factors allowing for investigation of all potential interactions involving these factors. This was performed separately for each time point (immediately after injection and 5 min post potential pain had vanished). When appropriate a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test was used. The analysis was conducted independently for each movement direction (right, left, extension and flexion). Likert scores of the perceived difficultness of the head repositioning test were compared over time (baseline, immediately after injection, and 5 min post potential pain had vanished) independently for the two cognitive tasks (with and without calculations) using a Friedmans ANOVA. Wilcoxon tests were used as post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction (0.05/9=p<0.0055). Furthermore, each of the three time points were compared between the two cognitive tasks using a Wilcoxon test with a Bonferroni correction (0.05/3=p<0.016). The level of significance was set to 0.05 unless otherwise stated.

Mean (±SEM) head repositioning accuracy (mm) for all movements without or with a cognitive task (Calculations) at the two baselines (A) before hypertonic injection and (B) before the isotonic injection.

| Right (most accurate) | Right (least accurate) | Left (most accurate) | Left (least accurate) | Extension (most accurate) | Extension (least accurate) | Flexion (most accurate) | Flexion (least accurate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | ||||||||

| No cognitive task | 5.96 (0.60) | 14.51 (1.62) | 5.54 (0.35) | 14.35 (1.79) | 8.76 (1.07) | 18.87 (1.57) | 6.54 (0.47) | 18.95 (3.42) |

| Cognitive task | 8.10 (1.22) | 11.14 (1.71) | 7.90 (1.06) | 12.12 (1.97) | 8.50 (1.05) | 17.14 (2.32) | 8.40 (1.37) | 18.33 (3.21) |

| B | ||||||||

| No cognitive task | 9.24 (0.52) | 12.69 (1.31) | 6.22 (0.39) | 13.07 (1.42) | 7.42 (0.77) | 19.05 (2.32) | 8.94 (1.03) | 23.00 (3.69) |

| Cognitive task | 9.77 (1.88) | 10.84 (1.68) | 8.85 (1.04) | 12.67 (1.57) | 9.07 (1.24) | 16.34 (3.08) | 11.07 (2.37) | 22.65 (3.22) |

3 Results

3.1 Quantification of pain

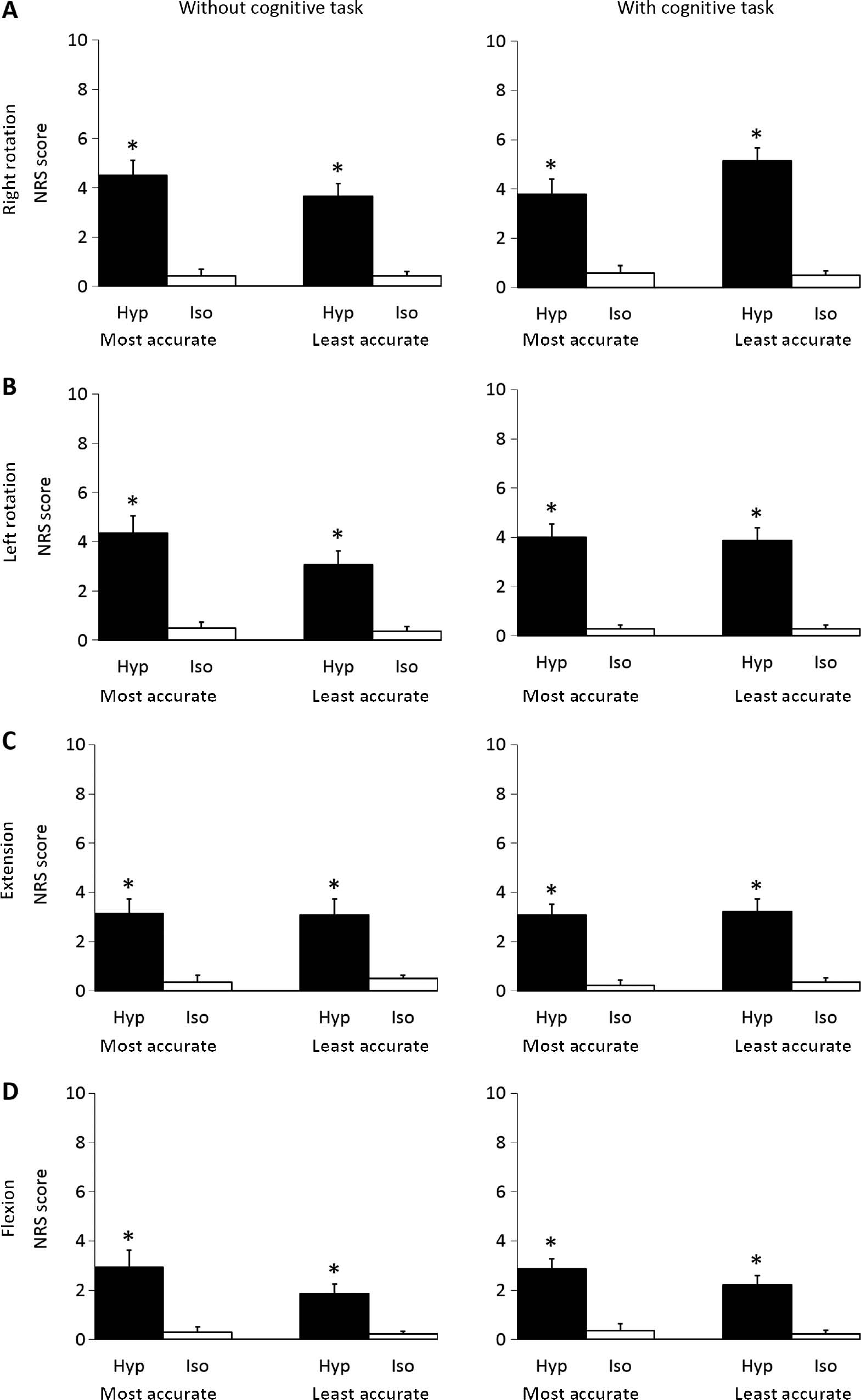

No adverse reactions, other than pain, were experienced by the participants during the study. Following the hypertonic saline injection, pain was felt in all movement directions by all but one participant, who felt no pain during the cognitive task while performing vertical movements (up & down). A significantly higher NRS score was observed following injection of hypertonic saline compared to isotonic saline (Wilcoxon: p<0.001) for all movement directions while no significant difference was observed between the most/least accurate groups (Fig. 3).

Mean (±SEM) NRS scores following Right rotation (A), Left rotation (B), Extension (C), Flexion (D) movements without or with a cognitive task for the most accurate- (n=14) and least accurate (n=14) group immediately after injection of hypertonic (Hyp; N=28) or isotonic (Iso; N=28) saline. *Significantly different compared to isotonic condition (Wilcoxon: p<0.001).

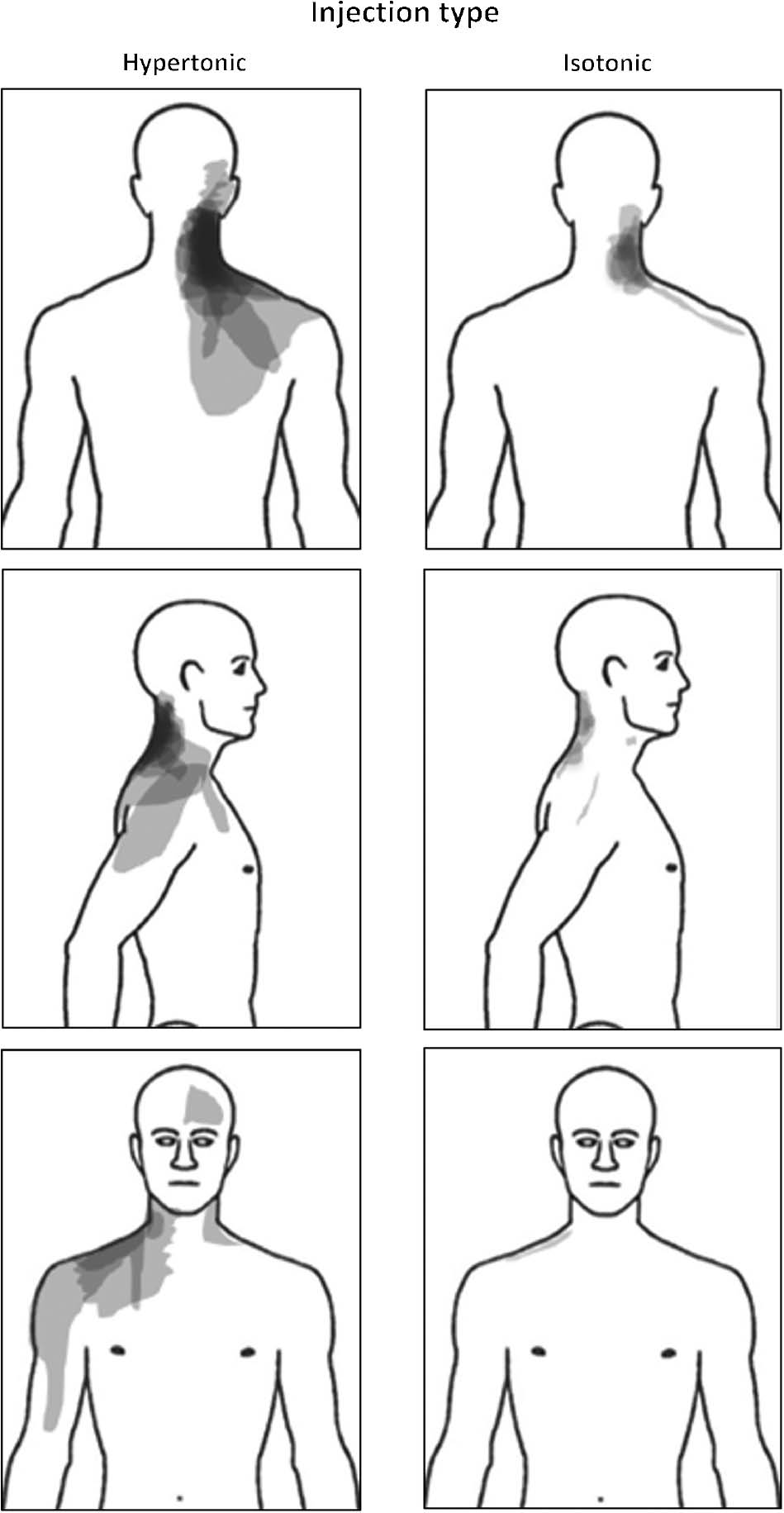

None of the participants reported any perceived area of pain (Fig. 4) on the left side, while a significant difference in size of area was observed between the hypertonic and the isotonic conditions on both the posterior (0.67±0.14 a.u. vs. 0.13±0.04 a.u.) and the right (0.32±0.11 a.u. vs. 0.03±0.02 a.u.) sides (Wilcoxon: p<0.001). The most commonly chosen words from the McGill questionnaire were “pressing” (42.9%), and “tight” (39.3%), along with “hot” and “taut” (32.1%) following the hypertonic saline injection. For the isotonic injection the most common words were “pressing”, “tender”, “annoying” and “tight” (14.3%).

Superimposed body chart recordings (N=28) during the two experimental conditions following injection of hypertonic or isotonic saline into the right splenius capitis muscle. Darker colour indicates areas that were marked more frequently by participants.

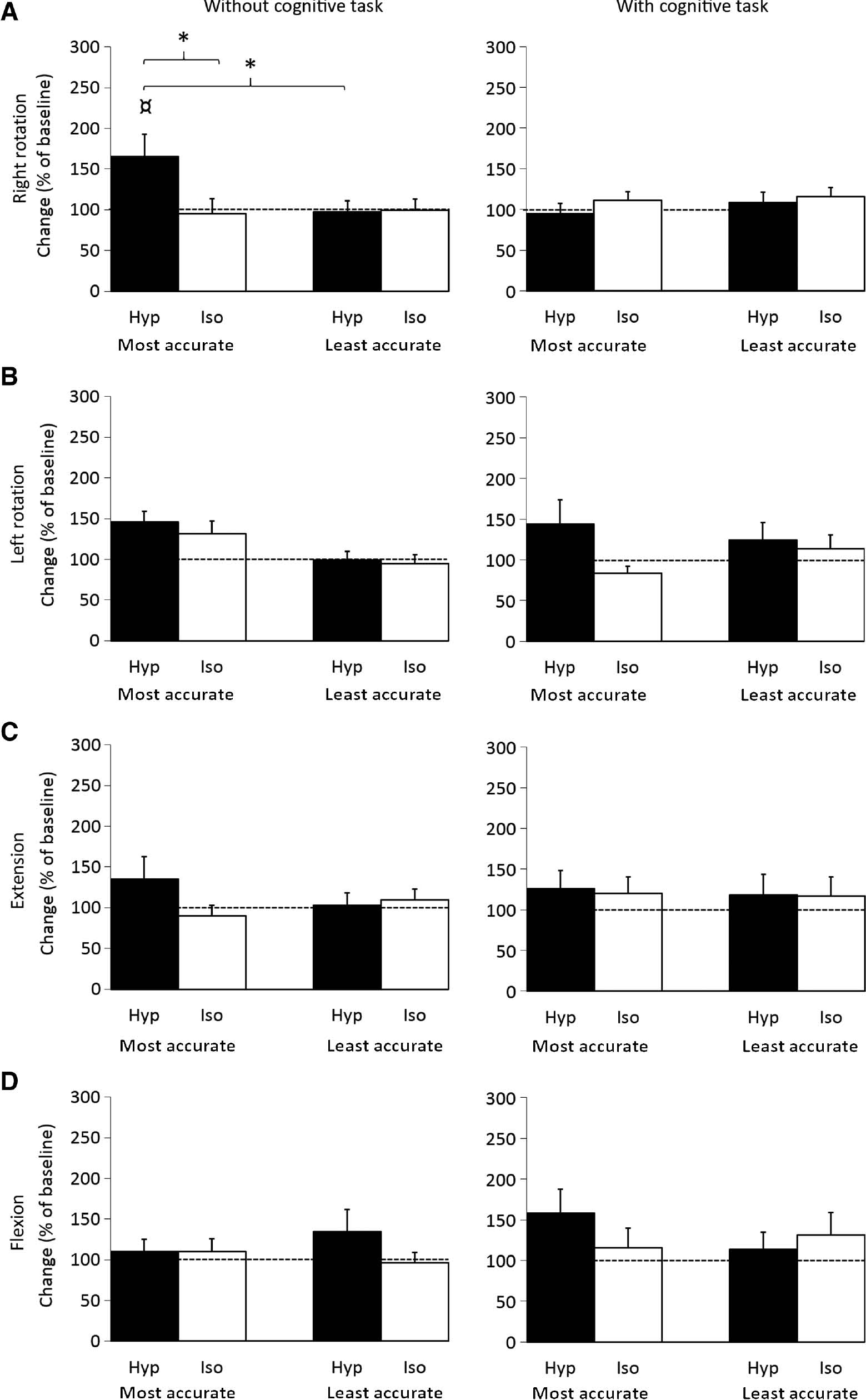

3.2 Head repositioning accuracy immediately after injections

A significant task*saline*group interaction was observed for the right rotation movement (RM-ANOVA: F[1.26]=4.4 p=0.043). The post hoc test revealed a significant reduction (worse) in HRA for the most accurate group following the painful injection during movements without the cognitive task when compared to the isotonic condition (Newman-Keuls: p=0.018), the least accurate group (Newman-Keuls: p=0.033), and the cognitive task (Newman-Keuls: p=0.021) (Fig. 5A). No other significant interactions were observed for any other movement direction.

Mean (±SEM) normalized head repositioning accuracy recordings for Right rotation (A), Left rotation (B), Extension (C), Flexion (D) movements (N=28, Left n=27) without or with a cognitive task (Calculations) for the most accurate- and least accurate group immediately after injection of hypertonic (Hyp; N=28) or isotonic (Iso; N=28) saline. *Significantly different compared to isotonic condition, least accurate group and ¤cognitive task (Newman-Keuls: p<0.05).

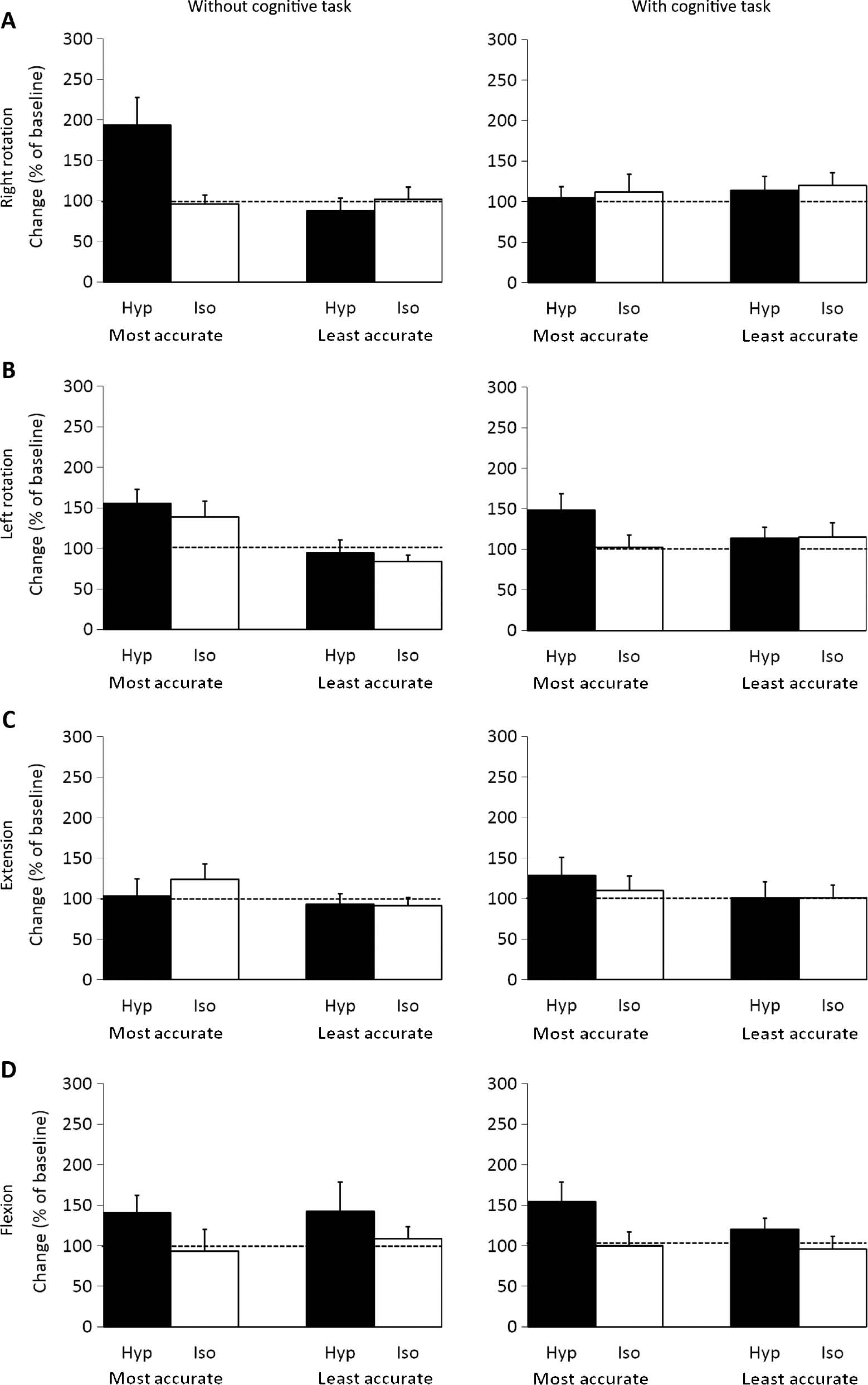

Results from the post measurements can be seen in Fig. 6.

Mean (±SEM) normalized head repositioning accuracy recordings for Right rotation (A), Left rotation (B), Extension (C), Flexion (D) movements (N=28, Left n=27) without or with a cognitive task (Calculations) for the most accurate- and least accurate group during the post session following injection of hypertonic (Hyp; N=28) or isotonic (Iso; N=28) saline.

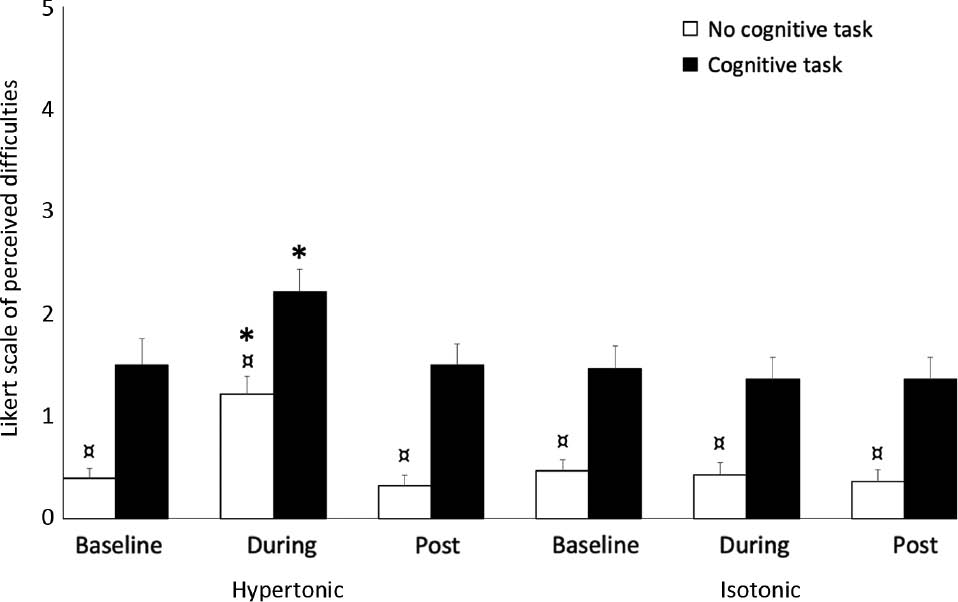

3.3 Perceived performance of head repositioning test

For the Likert score of perceived difficultness, the Friedman’s ANOVA was significant both without (χ2(5)=44.3, p<0.001) and with the cognitive tasks (χ2(5)=43.8, p<0.001). The post-hoc test showed that participants found the HRA test more difficult during experimental pain compared to both baseline- and post measurements (Wilcoxon: p<0.002) and the isotonic condition (Wilcoxon: p<0.002) independent of the cognitive tasks (Fig. 7). For all sessions (baseline, immediately after injection and 5 min post potential pain had vanished) and conditions (hypertonic, isotonic) the tests with the cognitive task were perceived as more difficult compared to the tests without the cognitive task (Wilcoxon; p<0.002).

Mean (±SEM) Likert scores (N=28) at baseline, during (immediately after injection; Hyp: N=28; Iso: N=28) and post (5 min after any potential pain had vanished) for the head repositioning accuracy test (Cognitive task is depicted with filled pillars). *Significantly different compared to baseline, post and control (isotonic) condition during the same cognitive task (Wilcoxon: p<0.002). ¤Significantly different compared to the cognitive task (Wilcoxon: p<0.002).

4 Discussion

This study showed that acute experimental neck pain in the right splenius capitis muscle impaired HRA during ipsilateral rotation, but only in those most accurate at baseline. However, this difference between the most and least accurate group was no longer present when a cognitive task was added during the HRA test.

4.1 Quantification of pain

Participants reported increased intensity and perceived area of pain following the hypertonic compared to the isotonic saline injection. These findings are in line with those by Malmstrom et al. [19], who also injected hypertonic saline into the splenius capitis muscle in healthy participants and showed that the painful condition impaired HRA, increased intensity and perceived area of pain.

4.2 Effect of neck-related pain on head repositioning accuracy

A novel finding is that neck muscle pain on the right side impaired HRA following right rotations only for the most accurate group. The previous study by Malmstrom et al. [19] suggested that reduced HRA during a painful (hypertonic) condition could be due to altered proprioceptive input from neck muscles [19]. If experimental muscle pain alters proprioception, why do the most/least accurate groups not display similar results when their pain levels are comparable? It could be that impairment due to pain differs between individuals, which could also explain why only some of those suffering from clinical neck pain experience proprioceptive disturbances [19]. Another explanation could be a floor effect, with the least accurate group performing close to a lower limit of accuracy in a healthy population, and thereby having less room for impairment compared to the most accurate group. However, it is important to note the limited sample size in the current work and hence these results should be interpreted with caution.

4.3 Effect of cognitive task on head repositioning accuracy during neck-related pain

The impairment in HRA seen for the most accurate group during the painful (hypertonic) condition was reduced when the cognitive task was added (Fig. 5A). As previously mentioned, it has been suggested that proprioceptive disturbance may be the mechanism underlying impaired HRA [19], but this seems unlikely in the current study, as this impairment should not be impacted by a cognitive task. However, one explanation for impaired HRA not being present when the cognitive task was added, might be the increase in cognitive resources required to complete the cognitive task, which diminish the available cognitive resources for processing the painful stimulus. In line, Eccleston et al. [31] proposed that pain demands attention, but that it is also possible to distract this attention with another demanding cognitive task. Furthermore, if there are multiple tasks requiring cognitive resources, they may not be able to be processed simultaneously and the available resources can then be directed in order to prioritize one task over the others, with the aim of ensuring that the intended goal can be reached [32], [33]. With this in mind, the results of the current study could indicate that the instructed task (completing the cognitive task during the head repositioning test) was prioritized over directing cognitive resources towards pain, which could be considered less goal relevant. If this was the case, that one task was prioritized over another, this could explain why the most accurate group performed worse during pain but displayed enhanced performance when the cognitive task was added. This is consistent with a previous study using experimental pain in a healthy population, showing that pain impacted motor performance during a simple computer task, but not during a more demanding cognitive task [34]. While determining cognitive demand during a given task is not easy, the current study gives an indication of this by asking participants to rate perceived difficulty of the HRA test with and without the cognitive task (Fig. 7). Here, participants perceived movements without a cognitive task to be more demanding during experimental pain, but when the cognitive task was added it was perceived significantly more difficult under all conditions regardless of pain, suggesting that the cognitive task did influence the available cognitive resources. In fact, on average, even the baseline Likert score for the test with the cognitive task surpassed that of the non-cognitive task during pain, which further increases the likelihood that the cognitive task was of sufficient magnitude to distract the participants attention away from pain. However, one consideration that has to be made when interpreting the results of the Likert score, is that this was only obtained following an entire test session (all movement directions), so it is not possible to link perceived difficultness of performing the HRA test to a specific direction or group. The Likert results might have been different if they had been obtained following each movement direction, as pain was induced only on one side of the neck, which could have helped to illuminate any potential differences in perceived performance between groups or directions.

4.4 Head repositioning accuracy and movement directions

Interestingly, only HRA following right sided movements were significantly affected in the current study, which is in line with the study by Malmstrom et al. [19], although this was only when the target position for the HRA was in 30° rotation. Putting the target-position at 30° rotation may increase sensitivity to alterations in cervical kinaesthesia [13] which could help explain why the previous study only found the HRA to be significantly affected in 30° rotation. The observed changes in both the current and the previous study [19] could simply be due to the fact that experimental neck pain in both studies was induced in the right splenius capitis muscle, which is involved in ipsilateral rotation of the head [35]. One could therefore hypothesize that pain in one of the muscles responsible for ipsilateral rotation might be able increase demand for cognitive resources during that specific movement more than during other movements. This is supported by a study which suggested that the side of pain might play a role when testing HRA in a clinical population [17], while another study argued that rotation movements might be more susceptible to changes compared to extension, as rotation movements are more complex [4]. Another consideration that needs to be mentioned with regard to the current study is that it cannot be ruled out that increased load on the cervical spine, made by the helmet mounted with lasers (Fig. 2), along with the audio que (beeps), might have influenced HRA in some participants. However, if this was the case it should have influenced all movements, and, as all participants act as their own control in this study, we do not believe that this has significantly influenced the results. Furthermore, using only three repetitions for estimating mean HRA for each movement direction may be less reliable than if more repetitions were used [2], [36], [37], though a study from 2013 did not find significant differences based on the number of repetitions (three vs. six) used to estimate the HRA and argued that using fewer trials is more appropriate for clinical use as the pain experienced by the patients often limits the number of trials possible [38].

In combination, the results of the current study are of clinical importance as they question how the results of HRA tests are interpreted when neck pain patients present in the clinical setting and their normal pain-free HRA is unknown. However, it is important to recognise that the current study was conducted using a short-lasting experimental neck muscle pain in healthy participants and the results may therefore not be directly transferable to a clinical population with long-lasting neck pain where altered motor control may be more evident. Nevertheless, this study does highlight how pain may be the driver of such alterations.

The HRA test is mainly of clinical interest when there are symptoms, which may arise from altered proprioceptive input, such as altered postural control, unsteadiness, dizziness etc. [12], [39]. Furthermore, the HRA test should be just one part of a clinical examination that can help indicate potential contributing factors of the presented symptoms, such as dizziness, in neck pain patients. Lastly, exercise interventions have shown to improve HRA in neck pain populations [39], [40]. With this in mind, regardless of HRA prior to the onset of neck pain, the HRA test can be used to monitor performance in neck pain populations [38]. Nonetheless, as this is the first study to investigate the impact of a cognitive task on HRA, future experimental and clinical studies are warranted to help illuminate these effects and thereby improve our understanding of factors and mechanisms that might influence HRA test results.

In conclusion, HRA was affected following saline-induced experimental neck pain in healthy participants, but only in those who were most accurate prior to pain. This difference was no longer present when a cognitive task was added to the HRA test. These findings are of clinical importance as they add to our understanding of how results from the HRA test should be interpreted in neck pain patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Megan E. McPhee, PhD-fellow, at Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain (CNAP), for her assistance with proofreading the manuscript.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: The study was funded by The Danish Rheumatism Association. Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain (CNAP) is supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF121). Steffan Wittrup McPhee Christensen is supported by the Fund for research, quality and education in physiotherapy practice (Fysioterapipraksisfonden) and the Lundbeck Foundation for Health Care Research.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by The North Denmark Region Committee on Health Research Ethics (N-20120018).

References

[1] Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59.10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] de Vries J, Ischebeck BK, Voogt LP, van der Geest JN, Janssen M, Frens MA, Kleinrensink GJ. Joint position sense error in people with neck pain: a systematic review. Man Ther 2015;20:736–44.10.1016/j.math.2015.04.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Stanton TR, Leake HB, Chalmers KJ, Moseley GL. Evidence of impaired proprioception in chronic, idiopathic neck pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 2016;96:876–87.10.2522/ptj.20150241Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Treleaven J, Jull G, Sterling M. Dizziness and unsteadiness following whiplash injury: characteristic features and relationship with cervical joint position error. J Rehabil Med 2003;35:36–43.10.1080/16501970306109Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Kristjansson E, Hardardottir L, Asmundardottir M, Gudmundsson K. A new clinical test for cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility: “the fly”. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:490–5.10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00619-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Humphreys BK. Cervical outcome measures: testing for postural stability and balance. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008;31:540–6.10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.08.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Juul-Kristensen B, Clausen B, Ris I, Jensen RV, Steffensen RF, Chreiteh SS, Jørgensen MB, Søgaard K. Increased neck muscle activity and impaired balance among females with whiplash-related chronic neck pain: a cross-sectional study. J Rehabil Med 2013;45:376–84.10.2340/16501977-1120Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Uthaikhup S, Assapun J, Kothan S, Watcharasaksilp K, Elliott JM. Structural changes of the cervical muscles in elder women with cervicogenic headache. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2017;29:1–6.10.1016/j.msksp.2017.02.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Elliott JM, Pedler AR, Jull GA, Van Wyk L, Galloway GG, O’Leary SP. Differential changes in muscle composition exist in traumatic and nontraumatic neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:39–47.10.1097/BRS.0000000000000033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Vuillerme N, Pinsault N, Vaillant J. Postural control during quiet standing following cervical muscular fatigue: effects of changes in sensory inputs. Neurosci Lett 2005;378:135–9.10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.024Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Gomez S, Patel M, Magnusson M, Johansson L, Einarsson EJ, Fransson PA. Differences between body movement adaptation to calf and neck muscle vibratory proprioceptive stimulation. Gait Posture 2009;30:93–9.10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.03.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Treleaven J, Chen X, Sarig Bahat H. Factors associated with cervical kinematic impairments in patients with neck pain. Man Ther 2016;22:109–15.10.1016/j.math.2015.10.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Kristjansson E, Dall’Alba P, Jull G. Cervicocephalic kinaesthesia: reliability of a new test approach. Physiother Res Int 2001;6:224–35.10.1002/pri.230Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Revel M, Andre-Deshays C, Minguet M. Cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility in patients with cervical pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991;72:288–91.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Heikkila HV, Wenngren BI. Cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility, active range of cervical motion, and oculomotor function in patients with whiplash injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1089–94.10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90176-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Kristjansson E, Oddsdottir GL. “The Fly”: a new clinical assessment and treatment method for deficits of movement control in the cervical spine: reliability and validity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E1298–305.10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e7fc0aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R. Development of motor system dysfunction following whiplash injury. Pain 2003;103:65–73.10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00420-7Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Treleaven J. Sensorimotor disturbances in neck disorders affecting postural stability, head and eye movement control – Part 2: case studies. Man Ther 2008;13:266–75.10.1016/j.math.2007.11.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Malmstrom EM, Westergren H, Fransson PA, Karlberg M, Magnusson M. Experimentally induced deep cervical muscle pain distorts head on trunk orientation. Eur J Appl Physiol 2013;113:2487–99.10.1007/s00421-013-2683-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Vernon H, Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991;14:409–15.10.1037/t35122-000Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Helgadottir H, Kristjansson E, Mottram S, Karduna AR, Jonsson Jr H. Altered scapular orientation during arm elevation in patients with insidious onset neck pain and whiplash-associated disorder. J Orthop Sports Phys 2010;40:784–91.10.2519/jospt.2010.3405Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Takasaki H, Hall T, Kaneko S, Iizawa T, Ikemoto Y. Cervical segmental motion induced by shoulder abduction assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E122–6.10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818a26d9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Christensen SW, Hirata RP, Graven-Nielsen T. The effect of experimental neck pain on pressure pain sensitivity and axioscapular motor control. J Pain 2015;16:367–79.10.1016/j.jpain.2015.01.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Christensen SW, Hirata RP, Graven-Nielsen T. Bilateral experimental neck pain reorganize axioscapular muscle coordination and pain sensitivity. Eur J Pain 2017;21:681–91.10.1002/ejp.972Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Falla D, Farina D, Dahl MK, Graven-Nielsen T. Muscle pain induces task-dependent changes in cervical agonist/antagonist activity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102:601–9.10.1152/japplphysiol.00602.2006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–52.10.1002/acr.20543Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975;1:277–99.10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Drewes AM, Helweg-Larsen S, Petersen P, Brennum J, Andreasen A, Poulsen LH, Jensen TS. McGill Pain Questionnaire translated into Danish: experimental and clinical findings. Clin J Pain 1993;9:80–7.10.1097/00002508-199306000-00002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Strimpakos N. The assessment of the cervical spine. Part 1: range of motion and proprioception. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2011;15:114–24.10.1016/j.jbmt.2009.06.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Wang X, Lindstroem R, Carstens NP, Graven-Nielsen T. Cervical spine reposition errors after cervical flexion and extension. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:102.10.1186/s12891-017-1454-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Eccleston C, Crombez G. Pain demands attention: a cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychol Bull 1999;125:356–66.10.1037//0033-2909.125.3.356Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Van Damme S, Legrain V, Vogt J, Crombez G. Keeping pain in mind: a motivational account of attention to pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;34:204–13.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Goschke T, Dreisbach G. Conflict-triggered goal shielding: response conflicts attenuate background monitoring for prospective memory cues. Psychol Sci 2008;19:25–32.10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02042.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. Interactions of pain intensity and cognitive load: the brain stays on task. Cereb Cortex 2007;17:1412–22.10.1093/cercor/bhl052Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Bogduk N, Mercer S. Biomechanics of the cervical spine. I: normal kinematics. Clin Biomech 2000;15:633–48.10.1016/S0268-0033(00)00034-6Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Pinsault N, Fleury A, Virone G, Bouvier B, Vaillant J, Vuillerme N. Test-retest reliability of cervicocephalic relocation test to neutral head position. Physiother Theory Pract 2008;24:380–91.10.1080/09593980701884824Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Swait G, Rushton AB, Miall RC, Newell D. Evaluation of cervical proprioceptive function: optimizing protocols and comparison between tests in normal subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:E692–701.10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a5a1bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Juul T, Langberg H, Enoch F, Sogaard K. The intra- and inter-rater reliability of five clinical muscle performance tests in patients with and without neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:339.10.1186/1471-2474-14-339Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Treleaven J, Peterson G, Ludvigsson ML, Kammerlind AS, Peolsson A. Balance, dizziness and proprioception in patients with chronic whiplash associated disorders complaining of dizziness: a prospective randomized study comparing three exercise programs. Man Ther 2016;22:122–30.10.1016/j.math.2015.10.017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Jull G, Falla D, Treleaven J, Hodges P, Vicenzino B. Retraining cervical joint position sense: the effect of two exercise regimes. J Orthop Res 2007;25:404–12.10.1002/jor.20220Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2020 Rogerio Pessoto Hirata et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Change in Editorship: A Tribute to the Outgoing Editor-in-Chief

- Editorial comments

- Laboratory biomarkers of systemic inflammation – what can they tell us about chronic pain?

- Considering the interpersonal context of pain catastrophizing

- Systematic review

- Altered pain processing and sensitisation is evident in adults with patellofemoral pain: a systematic review including meta-analysis and meta-regression

- Topical reviews

- Pain revised – learning from anomalies

- Role of the immune system in neuropathic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Cryoneurolysis for cervicogenic headache – a double blinded randomized controlled study

- Interpersonal problems as a predictor of pain catastrophizing in patients with chronic pain

- Pain and small-fiber affection in hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP)

- Predicting the outcome of persistent sciatica using conditioned pain modulation: 1-year results from a prospective cohort study

- Observational studies

- Revised chronic widespread pain criteria: development from and integration with fibromyalgia criteria

- The relationship between patient factors and the refusal of analgesics in adult Emergency Department patients with extremity injuries, a case-control study

- Chronic neuropathic pain after traumatic peripheral nerve injuries in the upper extremity: prevalence, demographic and surgical determinants, impact on health and on pain medication

- Tramadol prescribed use in general and chronic noncancer pain: a nationwide register-based cohort study of all patients above 16 years

- Changes in inflammatory plasma proteins from patients with chronic pain associated with treatment in an interdisciplinary multimodal rehabilitation program – an explorative multivariate pilot study

- Original experimental

- The pro-algesic effect of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) injection into the masseter muscle of healthy men and women

- The relationship between fear generalization and pain modulation: an investigation in healthy participants

- Experimental shoulder pain models do not validly replicate the clinical experience of shoulder pain

- Computerized quantification of pain drawings

- Head repositioning accuracy is influenced by experimental neck pain in those most accurate but not when adding a cognitive task

- Short communications

- Dispositional empathy is associated with experimental pain reduction during provision of social support by romantic partners

- Superior cervical sympathetic ganglion block under ultrasound guidance promotes recovery of abducens nerve palsy caused by microvascular ischemia

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Change in Editorship: A Tribute to the Outgoing Editor-in-Chief

- Editorial comments

- Laboratory biomarkers of systemic inflammation – what can they tell us about chronic pain?

- Considering the interpersonal context of pain catastrophizing

- Systematic review

- Altered pain processing and sensitisation is evident in adults with patellofemoral pain: a systematic review including meta-analysis and meta-regression

- Topical reviews

- Pain revised – learning from anomalies

- Role of the immune system in neuropathic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Cryoneurolysis for cervicogenic headache – a double blinded randomized controlled study

- Interpersonal problems as a predictor of pain catastrophizing in patients with chronic pain

- Pain and small-fiber affection in hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP)

- Predicting the outcome of persistent sciatica using conditioned pain modulation: 1-year results from a prospective cohort study

- Observational studies

- Revised chronic widespread pain criteria: development from and integration with fibromyalgia criteria

- The relationship between patient factors and the refusal of analgesics in adult Emergency Department patients with extremity injuries, a case-control study

- Chronic neuropathic pain after traumatic peripheral nerve injuries in the upper extremity: prevalence, demographic and surgical determinants, impact on health and on pain medication

- Tramadol prescribed use in general and chronic noncancer pain: a nationwide register-based cohort study of all patients above 16 years

- Changes in inflammatory plasma proteins from patients with chronic pain associated with treatment in an interdisciplinary multimodal rehabilitation program – an explorative multivariate pilot study

- Original experimental

- The pro-algesic effect of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) injection into the masseter muscle of healthy men and women

- The relationship between fear generalization and pain modulation: an investigation in healthy participants

- Experimental shoulder pain models do not validly replicate the clinical experience of shoulder pain

- Computerized quantification of pain drawings

- Head repositioning accuracy is influenced by experimental neck pain in those most accurate but not when adding a cognitive task

- Short communications

- Dispositional empathy is associated with experimental pain reduction during provision of social support by romantic partners

- Superior cervical sympathetic ganglion block under ultrasound guidance promotes recovery of abducens nerve palsy caused by microvascular ischemia