Abstract

Chemistry is filled with complex and abstract concepts in interconnected systems. It is considered as the central science for linking with other scientific disciplines. Chemistry cannot be separated from our daily life. But it has been a challenge for school students to learn its concepts at various levels of educational systems. In this article, I will start with an introduction on investigations of students’ conceptions of chemical concepts, teachers’ understanding of students’ knowledge of scientific phenomena, and strategies for promoting students’ conceptual change in learning science, including model-based and modeling-based instruction as well as adoption of innovative technology in learning sciences (such as, the use of facial expressions system augmented reality and virtual reality in learning chemistry). And then, I will describe a few outreach activities on promoting public understanding of chemistry, developing educators’ competence in teaching chemistry, as well as investigation on gender gap in STEM sponsored by ISC, IUPAC and other unions and partners.

Introduction

Chemistry is a science discipline that studies properties and behaviors of chemical matters. It includes chemical elements, compounds, and interactions among atoms, ions, and molecules in a complex system. Chemistry education is to study how researchers or teachers can convey the nature, properties, and structure of matters, as well as impact of chemistry on daily lives effectively and how students construct their knowledge structure and develop inquiry skills in chemistry learning. In this report, I will share some of my main research streams in the area of science education, in particular, in chemistry, over the past 30 years. The research topics include students’ conceptions of chemistry, teacher professional development, instructional strategies for promoting learning in chemistry, computer-based approaches to science learning, assessment of students’ performance in learning chemistry, etc. (see Fig. 1).

A path of my research areas.

Students’ conceptions of chemistry

Research has shown that conceptions are personal, robust, and incoherent [1] and regardless of levels of education, gender, races, or geographic areas, learners have various but similar alternative conceptions about chemical concepts, and more importantly, they are difficult to change [2]. Chemistry is a scientific discipline that is filled with complex and abstract concepts and interactions among the concepts, which increases the difficulties and challenges of its teaching and learning. To construct meaningful representations of scientific phenomenon while learning chemistry, it is important to link the aspects in macroscopic, (sub-)microscopic, and symbolic representations [3], [4], [5], [6] and to connect meaningful representations.

The central concepts to be learned in chemistry at secondary school level include structures and properties of elements, oxidation and reduction, acids and bases, chemical equilibrium, and applications of chemistry. The fundamental concepts of chemistry will serve as vehicles for learning advanced concepts in chemistry. A chemical system involves elements and chemical compounds, their interactions, and factors and impacts of such interactions. Not only is the macroscopic perspective of the scientific phenomenon making learning chemistry challenging, the microscopic, abstract, and symbolic representations of the chemical reactions and theories are also making such conceptualization difficult. Researchers of learning theories have found that students come to classrooms with prior knowledge that often are not consistent with scientific explanations and principles [7], [8], [9] and lacks the ability to visualize. This may be attributed to their capacity of cognitive understanding of the physical world or the context that the learners are in. For instance, students need to understand what the compositions and properties of atoms are to understand how a chemical reaction might occur. They also need to understand the properties and structures of elements and compounds to understand the impact of chemical reactions, such as exothermic or endothermic reactions [10].

Research in chemistry education has found various types of alternative conceptions students own. It is crucial to uncover the kinds of students’ comprehension of chemistry so that useful strategies can be provided to facilitate students’ learning of chemistry. To uncover students’ understanding of science, various approaches have already been taken. One of them is the two-tier test diagnostic assessment tool, the first tier for factual knowledge while the second tier for explanations to the first tier responses proposed by Treagust [11], [12], [13]. It was adopted in an integrated project (including chemistry, biology, and physics) entitled The National Science Concept Learning Study (NSCLS) sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST, former National Science Council) in Taiwan. The tool aims to assess elementary, junior high, and senior high school students’ conceptual understanding of the subjects mentioned above to help us understand chemistry from students’ epistemic points of view. The author of this article was the coordinator of the chemistry group and also the principal investigator of the sub-project on examining secondary school students’ conceptions of gas particles, acid and base, and chemical equilibrium for four years [10]. The chemistry group involved eight professors in chemistry education from different universities and 4–8 in-service teachers from schools at different levels joining each professor’s group.

There were about 3600, 7000, and 3000 students in elementary (grade 4), junior high (grades 8 & 9), and the second year of senior high schools (grade 11), respectively, took the survey. Students were chosen based on the stratified sampling method (e.g., location—south, north, west, and east; school size) [14]. This method was adopted from the Trend of International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Due to the unique contribution of this study, specifically in terms of the sizes of the student samples from different school levels using the two-tier diagnostic tools in this study, the International Journal of Science Education published a special issue titled Taiwan’s National Science Concept Learning Study: A Large Scale Assessment Project using Two-Tier Diagnostic Tests in 2007.

Based upon the analyses, the results showed that 20 % of junior and 8 % of senior high school students thought that the size of the gas particles in a balloon increases when the balloon is expanded by heating [10]. The percentages of such alternative conceptions were not as high as we would expect based on the findings from other studies (e.g., [15], [16], [17], [18]). However, the results still revealed that about 20 % of the junior and senior high school students believed that hydrogen is distributed in the upper portion of the container because it is lighter compared to oxygen (weight model). Close to 35 % of the secondary school students believed that particles are not randomly distributed in a bottle. This finding is consistent with other studies (e.g., [19,20]). Understanding based on personal experiences is not a surprise to be found in this field of science education research because this alternative conception is consistent with students’ epistemic belief that it is easier for heavier objects to sink to the bottom of the bottle compared to lighter objects. Students have little concepts about dissociation of the chemical compounds. Also, close to 30 % of the secondary school students across different levels mistook ethanol (C2H5OH) to be a base because of –OH that is always considered as an indicator for metal hydroxide compounds (e.g., NaOH, Mg(OH)2) [21]. In addition, regardless of student levels, students did not recognize that the shape of sugar changed at the saturate (equilibrium) state ([10,22] cited in [10]). The same technique of two-tier diagnostic instrument was later adopted in Chiang et al.’s study [23] along with a semi-structured interview and a drawing concept map task to investigate 340 grades 10–12 senior high school students’ conceptions of oxidation-reduction reaction in Taiwan. The results show that most 11th graders performed equally well as the 12th graders in questions on the concept of electronic gain and loss in oxidation–reduction reactions, although there are slight differences which are not statistically significant. The 12th graders obtained higher scores in questions for defining the oxidation number and its application; scores increased as the grades increased.

From these studies, we found that moving from concrete levels of the scientific phenomenon and physical experiences to abstract representations was a challenge for students when they construct their cognitive structure of the chemical concepts. The progressive trajectory was slow and gradual but it was still promising as the grades increase [10]. We also noticed that, as expected, the older students outperformed the younger students, not only on the nature of components in a scientific phenomenon but also in the explanations involving the macroscopic and microscopic points of view. This revealed that the accumulative process of scientific concepts overcame the counterintuitive conceptions as learning occurred [10]. Although we could not attribute the increase in new knowledge or the removal of incorrect understanding of chemistry to any particular source from this early study, we later identified some possible sources influencing their understanding, such as daily life experiences, textbooks, discourse, and instruction [24]. The most impressive finding was the Chinese characters that, on the one hand, served to facilitate student understanding of the nature of chemistry (such as acid rain in Chinese implies acidity of the rain), and on the other hand, had a detrimental effect on students’ conceptualization (such as Calcium Carbonate, acid in Chinese, it coincidentally means acidity so the students will mistake it as a kind of acidic compound. Herron [25] once points out that language plays a central role in teaching and learning science. In our study, the types of students’ understanding of certain chemical concepts were apparently influenced by Chinese characters. This diagnostic approach allowed us to make inferences about the impact of our science education system and predict which of the students’ conceptions are learned and which of the students’ conceptions needed more attention in science practice [26]. On the other hand, the micro-level of analysis (second tier) of students’ arguments provided us with explanatory information about how students generate their representations of conceptions in relation to the physical world, scientific symbols, scientific models, and terminologies for learning science.

Teachers’ predictions of students’ conceptions in chemistry

Shulman [27] proposed the idea of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), including knowledge and beliefs about the science curriculum, students’ understanding of specific science topics, assessment in science, instructional strategies, knowledge about learning environment, students’ knowledge, and resources of instruction [27], [28], [29], [30], to improve the effectiveness of instruction, researchers and practitioners reoriented their teaching practice from content-oriented instruction to student-centered instruction. While such competence in chemistry are important (e.g., [31]), among the studies, researchers found that problems usually emerge when secondary school students shifted their perceptions of the physical world from macro to micro levels and from 2D to 3D representations of compounds. One possible explanation was that students lacked practice or the necessary manipulation of concrete objects (such as molecular models) to construct their understanding of 3D structures. Without understanding students’ difficulties, science teachers cannot provide appropriate and meaningful instruction to overcome the difficulties of learning chemistry [30,32]. Researchers advocated that a teacher should understand pupils’ ideas and the origins of such ideas to avoid ineffective communication in the classroom [28,33].

Based upon our findings on students’ alternative conceptions of chemical concepts [10], two studies about teachers’ knowledge of students’ performance on the nature and behavior of gases [34] and acid and base [35] were carried out. Below are the descriptions of the two studies.

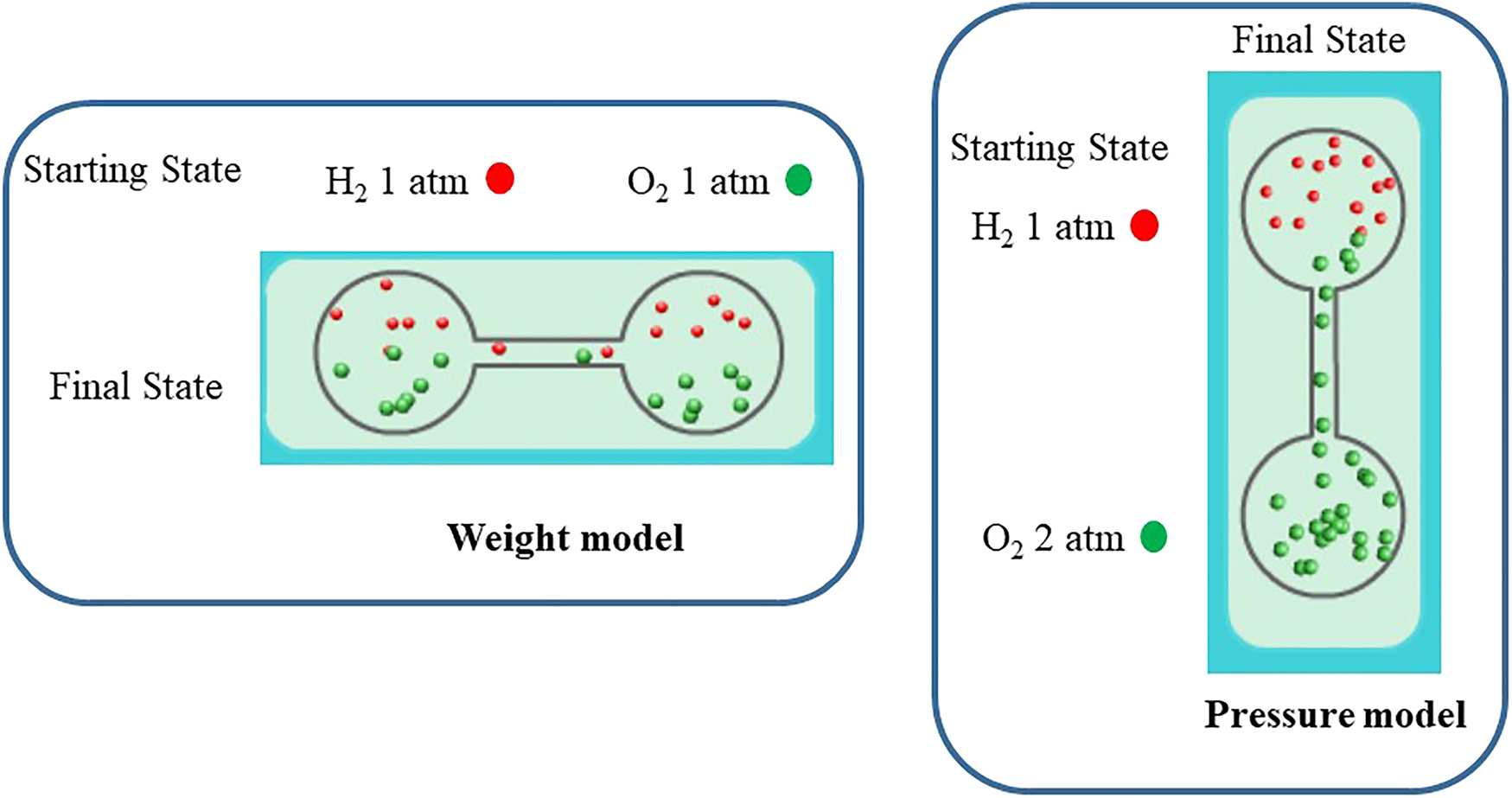

First, Liang, Chou, & Chiu [34] used six two-tier items about the behavior of gas particles in two containers in an animated diagnostic test to test students in middle schools. Teachers were then asked to make predictions of students’ test performance on those items. There were 194 junior high school students (including 102 8th grade and 92 9th grade students), and 31 junior high school physical science teachers in Taiwan who participated in this survey. The test items were designed in parallel in terms of the pressure of the gases and the settings of the apparatus (see Fig. 2). To closely match students’ mental representations of the dynamic nature of the movement of gas particles, the test items were designed with an animation software to allow the molecules to move in ways that reflect students’ descriptions about the behaviors of particles (see Fig. 2, details can be found in [34]). The results revealed that albeit the 9th graders outperformed the 8th graders as expected, only a low percentage of students could answer the entire set of six questions correctly. The students were influenced by the different orientations of the apparatus when the pressure and the amount of gas particles were changed. We found that students changed their models about gas behavior when the orientation of the apparatus changed from a horizontal to a vertical position and vice versa, and that the students had difficulty using a consistent model to answer all of the questions, especially questions involving a change in gas pressure.

Examples of test items in horizontal and vertical settings of the apparatus.

The results also showed that the physical science teachers could not predict students’ understanding of the behavior of gas particles accurately. For instance, the teachers thought the questions presented in horizontal situations were much easier than those questions presented in vertical situations. On the contrary, we found that the effect of pressure made it more difficult for students to correctly answer the test items, whereas some teachers thought that the effect of the orientation of the apparatus made this more difficult for students. The comparison revealed a mismatch between the teachers’ predictions of the students’ difficulties in answering the test items and the reality [34]. Regardless of the orientation of the apparatus and changes of pressures of gases, the results showed that the students lacked the conceptions of random distribution of particles in a closed system, which is a fundamental concept about movement of particles in learning chemistry. Without knowing the core problems that the students confront, it is impossible to construct a scientific and meaningful dialogue between students and teachers and for teachers to deliver sense-making instructional materials and interpretations of the phenomenon when teaching chemistry.

Secondly, students having alternative conceptions about acid and base is not a surprise. In fact, it has been evident for more than 30 years (e.g., 36–44). For instance, students considered acid as harmful [42], believed neutralization would always result in a neutral solution [41], and “OH” in a chemical are always related to basicity (ignoring organic compounds); whereas the symbol “H” is related to acidity [10], bases was far less developed than that of acids [43], strong acids produce a higher hydrogen ion and concentration, and the more H in the formulas, the higher its pH value [37,45], all acids are toxic and make substances corrosive [10,45], and only acids conduct electricity and bases do not [45].

Few teachers are aware of students’ inconsistent models or alternative conceptions of acids and bases [46]. Even if the teachers were aware of the difficulties of learning some specific topics, they would still teach without recognizing the important role of students’ knowledge representations in chemistry learning [37].

In such cases, imprecise predictions of students’ performance were not unique. After the national survey, Lin and Chiu [35] then conducted a case study with a junior high school chemistry teacher, Mrs. Chen, who majored in applied chemistry at a prestigious national university and had six years of teaching experience. She was interviewed before and after instruction to examine teacher–student interactions, discourse, scientific symbols, and representations in textbooks, as well as daily experiences to explore the possible sources influencing students’ mental representations [47–50]. The research found that Mrs. Chen did not use any specific tool to investigate students’ preconceptions about the topics she planned to teach before her teaching and her anticipations were mainly based on her understanding of the intended contents of the textbooks. It reflects a problem of not examining students’ prior knowledge before starting a new topic in teaching practice that might be common in many other school practices.

Based upon the interviews on the students’ mental representations and sources influencing the conceptualization of the intended concepts, Lin and Chiu [35] found that the teacher had a more accurate anticipations of high achievers’ mental models compared to low achieving students’. Also, the teacher made a more accurate prediction on the diverse sources influencing higher achievers’ mental models. It is understandable that high achievers’ had mental models that are more similar to the intended (or target) concepts and the low achievers have various alternative and fragmented conceptions which might not align with the teacher’s knowledge repertoire. In such a situation, designing sense-making materials to remedy their gap of understanding of the concepts might be a challenge [35]. With little understanding of the characteristics and inconsistent nature of lower achievers’ conceptual models and sources of generating learning obstacles (such as daily life experiences), the teacher underestimated the effects of her teaching on the performance of those students and failed to provide appropriate remedial instruction.

In both cases, it highlights the importance of knowing students’ starting points of specific content knowledge by teachers as a professional in science teaching. Teachers’ profession development should not only focus on deepening their understanding of the disciplinary core contents but also on ways to teach students according to their knowledge repertoire in order to make science meaningful to their learning.

Promoting conceptual change and modeling competence

Ontological approach for conceptual change

Although learning chemistry is challenging for many secondary school students and teachers, there are promising instructional strategies to elicit students’ understanding of abstract and complex concepts in chemistry. Researchers proposed various approaches to assist students to conquer the challenges of learning sciences. As a classic research in the area of conceptual change, the Conceptual Change Model proposed by Posner et al. [51] has been adopted in many instructional materials to promote students’ learning of science. Posner et al. [51] advocated four conditions to be fulfilled before conceptual accommodation may occur, namely learner being dissatisfied with the existing conceptions, the new conception being intelligible to the learner, the new conception initially appearing plausible, and seems to be fruitful for extension or to new areas of inquiry. Hewson and his colleagues [52], [53], [54], [55] further articulated conceptual status in “conceptual ecology” that can be used to assess students’ understanding of sciences. That is, as learners are dissatisfied with and in between competing and existing conceptions, there is likelihood for the new conception achieving higher status than the prior conception, a conceptual change will occur. If it does not reach a higher status, the old conception will remain. Such epistemological perspective was widely accepted and adopted as the conditions in instructional design [56]. Along the same line from the epistemological perspective, Vosniadou provided a possible explanation of why students have difficulties in learning science. She proposed that the presuppositions of each concept might support or hinder students to learn a new concept. Such epistemological presuppositions come from their observations and culture. On the contrary, Chi and her colleagues [2,57,58] proposed the Incompatibility Theory to uncover the difficulties of constructing scientific concepts for learners. She claimed that it is easier to change from one naïve conception to scientific concepts (e.g., categories of matters) within an ontological category (such as Matter) than across different ontological categories (such as from Matter to Process). The former reassignment of a specific concept within one ontological category simply involves hierarchical conceptual shifts or incremental changes, but no ontological shifts. While re-organization of a conception requires learners to reassign a concept to a completely different ontological category and thus it might be more difficult to take place. In Chi’s theory, robust “misconceptions” belong to different ontological categories from those for scientific concepts but they may still carry a coherent nature in their knowledge structure. We not only concur with Chi’s theory about conceptual change but we also claimed that “although Posner’s theory is widely accepted by science educators and easy to comprehend and apply to learning activities, … it does not delineate what the nature of a scientific concept is, which causes difficulty in learning the concept (p. 689).” This might be the first argument challenging Posner et al.’s theory. Below is an example that we carried out with the approach of ontological categories for learning chemical equilibrium. A similar approach was adopted for gas properties [59].

In chemistry education, there are very few studies discussing the ontological approach about students’ alternative conceptions and Chiu, Chou, & Liu [56] was one of them. They adopted Cognitive Apprenticeship instruction in guiding students to explore their understanding of the nature of chemical equilibrium. During the intervention, a prompting activity was designed to direct students’ attention to the target content, to make Predictions, Observation, and Explanations [60] of each chemical demonstration, as well as assess their learning while they interacted with the materials and experiments. The results indicated that some of the concepts of chemical equilibrium, such as the dynamic movement of the particles at equilibrium, were more difficult to learn than others. The focus on the nature of the chemical equilibrium of this study was to successfully and significantly help students construct the dynamic nature of the chemical equilibrium via the ontological approach of instruction. Our argument about the flow of the use PSGH theory [51] was echoed by other researchers in the area of conceptual change in science education [61].

Using facial recognition system to diagnose students’ conceptual change

While conceptual change research has shown challenges for students to conceptualize scientific phenomenon, various pedagogical strategies were proposed and implemented. One of the successful strategies was the conceptual conflict approach. The approach is a well-known method designed to move students from holding erroneous understandings to holding scientific concepts. Through presenting counterintuitive events to learners, it has been shown that the dissonance generated within learners propelled them to seek to modify their existing conceptions [62], [63], [64], [65], [66].

However, how do students react to learning new concepts emotionally? In education, it seems that there is no consensus about how emotion impacts learning. Some researchers argued that affect was positively correlated to confusion but negatively correlated to boredom [67]. It was also argued that positive emotions can positively predict student achievements and negative emotions negatively predict achievements [68,69]. However, it was also found that students would have to experience negative emotions as they confront concepts that contradict their preexisting understandings before they could experience the positive emotions [70,71].

As we know little about students’ reactions to counterintuitive scenarios while learning complex scientific concepts, we conducted a series of facial expression studies to investigate how students would react and whether or not the innovative technology, FaceReader, can help us identify the moment of learning.

Our first study about the use of facial microexpression state (FMES) on diagnosing students’ learning was via facing a counterintuitive scientific phenomenon (see Fig. 3) in which seven primary expressions (neutral, happiness, surprise, disgust, sadness, anger and fear; proposed by [72,73]) were registered and analyzed [62]. In the study, a heatless boiling of water experiment and a kinetic experiment with Prediction–Observation–Explanation–Visualization–Comparison (POEVC) design was shown to 48 high school students and 54 university students. The processes of the designs were similar for both experiments. Taking the heatless boiling experiment as an example (see Fig. 3), the students took pretests before the experiment, followed by a demonstration video in which water in a flask was boiled, sealed with a cork, and turned upside down with an ice bag placing on top of the inverted flask. The students were asked to make a prediction of the outcome of the demonstration (Boiling water demonstration video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IyeOfUGBxsA). Also, they were asked to observe the full demonstration of the experiment and asked to explain the reasons behind the result of the demonstration. The microscopic animation of the experiment behind the water boiling was presented to them and followed by a posttest. An interview about comparing their predictions and the outcomes of the experiment was conducted. This study showed that not only is the utilization of facial expression as a welfare assessment tool low [74], the adoption of facial expression in education is also limited.

The pictorial representation of procedures and contents of Example 1 (Boiling water demonstration).

The results showed that the counter-intuitive scenarios did trigger students’ incorrect predictions. Over 75 % of the students made incorrect predictions on both experiments. Among them, the absence of FMES changes indicates a lowered likelihood of conceptual change. Those with FMES change were twice more likely to undergo conceptual change than those without FMES change. Also, about 80 % of those without FMES change experienced no conceptual change. It was evident that FMES change was an effective method for detecting conceptual conflicts and identifying what happened during the learning process [62,75].

To move one more step further, we explored the possibility of utilizing the decision tree method in predicting students’ performance during learning processes, in particular, to understand the relationship between FMES changes and conceptual change when students are faced with different representations. The results showed that with regard to dominant expression distributions, negative expression was higher than the “Surprised” expression in all segments, except during Textual Instruction. Moreover, there is no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the dominant expressions of students with and without conceptual change. Students with positive expressions during Video Segment 1 or Video Segment 2 were found to have no conceptual change. The proportion of students with negative expression as their dominant expression was higher. This was followed by the expression of “Surprised”. Positive expression was the least frequent dominant expression, and it was only found in Video Segment 1 or Video Segment 2. We further used R, a statistical software, to construct the Classification and Regression Trees (CART) [76] and it became apparent that when students’ dominant expression was “Surprised” during the first video segment and “Negative” expressions during the third video segment, it could be predicted that students would fall under the conceptually changed group. When students’ dominant expressions were “Surprised” in both first and third video segments, then we could predict these students would end up in the no conceptual change category. Because this might imply that the students did not understand what happened so they felt surprised even watching the video for the third time. Lastly, if the dominant expression in the first video segment was “Not Surprised”, then it could be predicted that the students would not undergo conceptual change [77]. In these analyses, they were evident that the importance of facial expression of “Surprised” as an indicator to differentiate students as either conceptually changed or no conceptual change in conceptual conflict scenarios. This finding was consistent with our study using the decision tree models to identify three key FMESs, namely Surprised, Sad and Disgusted, that could be used to predict student conceptual change in a conceptual conflict-based scenario [78].

Based upon the findings from previous studies, we were wondering whether the different representation of scientific knowledge can facilitate students’ understanding of the complex knowledge and enhance their willingness to make changes of their conceptual understanding of specific phenomenon. We found that exhibiting negative FMES through all three major representation segments of the instructional process (i.e., scientific demonstration, textual instruction, and animated instruction) suggests a higher probability of conceptual change among students with sufficient background knowledge on the topic. For students with insufficient prior knowledge, the result was the opposite [65]. More importantly, the results show that animated representations were critical to the prediction of students’ conceptual change, followed by textual explanations and finally ends with the video demonstration of the experiment. It suggested that the animations of particles’ movement in the microscopic world can support students’ construction of the dynamic nature of particles, while simply watching the videos of a scientific phenomenon at macroscopic level did not guarantee the learning is occurred. Although these findings are from the second experiment on kinetics, we trust these results share commonalities with the heatless boiling experiment to some extent based upon previous analyses.

Based on the research on students’ learning and the importance of constructing scientific models for understanding scientific phenomenon, the next research stream is in the area of promoting model-based and modeling-based instruction.

Model-based and modeling-based approach

Science is considered as the process of constructing explanatory and predictive conceptual models of natural phenomena (e.g., [79], [80], [81]). Scientists use models to link their hypothesis, data, experiment, and interpretations of scientific phenomenon.

To support such development of meaningful understanding and generate explanatory models, it is necessary to engage students in sense-making work, to support students to do inquiry activities, and to explore models that can help them make judgement and interpretations with evidence collected in the activities [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89]. The goal-oriented approach in practice allows students to conceptualize why they are engaged in scientific activities and moves them from “doing the lesson” to “doing science” [90].

While models and modeling became an important trend of research and practice internationally, many researchers, countries, and organizations have highlighted modeling competence as one of the scientific competencies to be developed during school years [88,91–93].

For instance,it is explicitly stated that engagement in modeling and in critical and evidence-based argumentation invites and encourages students to reflect on the status of their own knowledge and their understanding of how science works in the NGSS [93] in the United States as well as in Taiwan [83]. Moreover, as the students have the opportunity to get themselves involved in the scientific practices, in particular, those stated explicitly in curriculum, it allows them to understand how science works and how it contributes to the development of sophisticated knowledge across different grade levels. In Taiwan, such emphasis on constructing models and making argumentation is also explicitly stated in the learning outcomes on Thinking Skills and Problem Solving as Inquiry Ability in the national curriculum standards [92]. However, too often school curricula fail to focus on the development of scientific models; textbooks also do not make appropriate use of historical and epistemological models, and teaching was found to rely on hybrid models (e.g., with scientific and alternative models) (e.g., [94]).

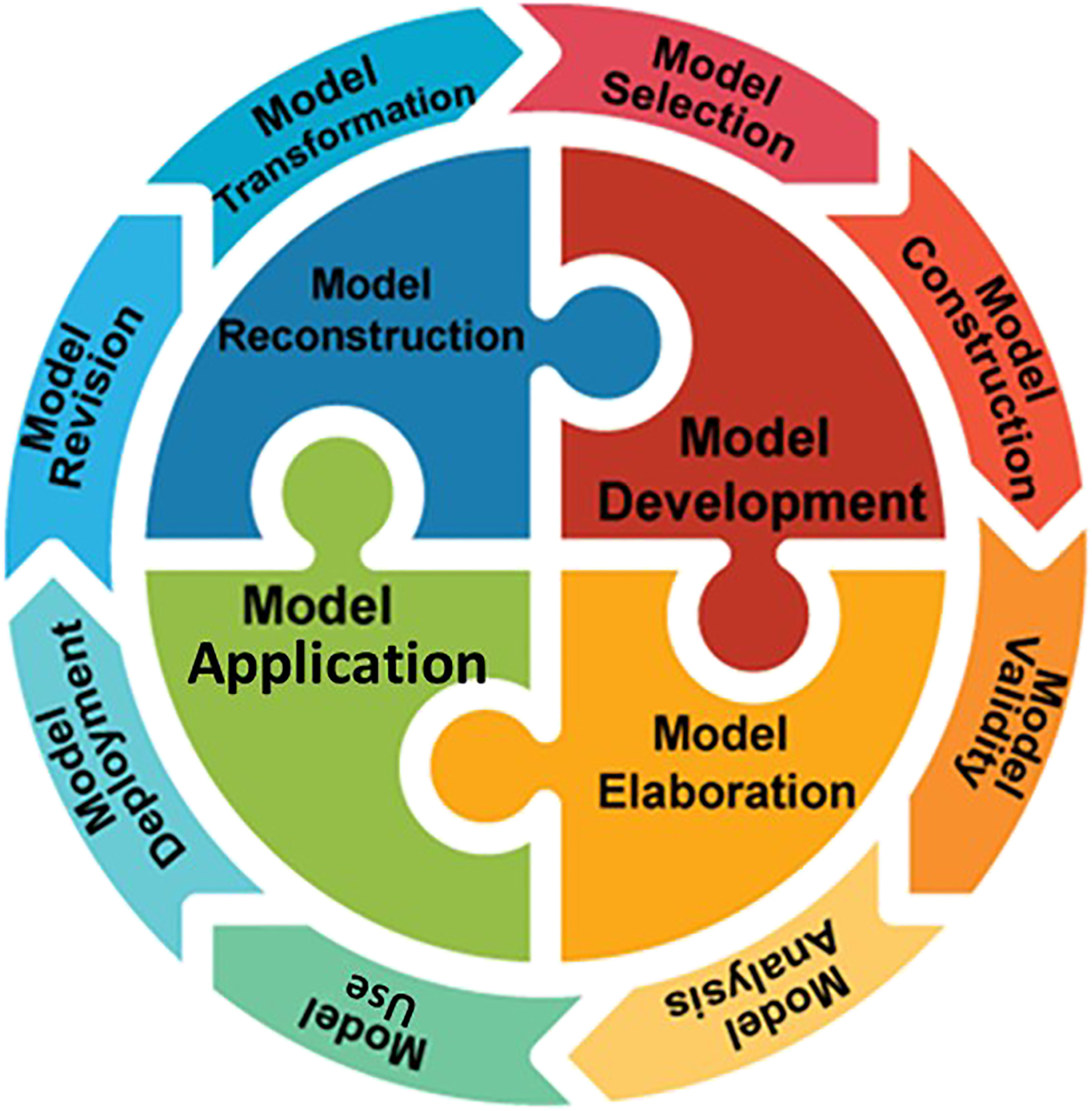

Along the same line, Chiu and Lin [83] proposed a modeling competence framework for curriculum and instructional designs to strengthen students’ modeling competence (see Fig. 4). Such a framework can be also used for assessing students’ modeling competence on constructing scientific knowledge as well as solving problems in complex situations. The framework includes three aspects, namely, knowledge of models and modeling, modeling practice (which includes modeling processes and modeling products), and metacognitive knowledge of models and modeling (see Fig. 4).

![Fig. 4:

The components of modeling competence (modified from [83]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2021-1103/asset/graphic/j_pac-2021-1103_fig_004.jpg)

The components of modeling competence (modified from [83]).

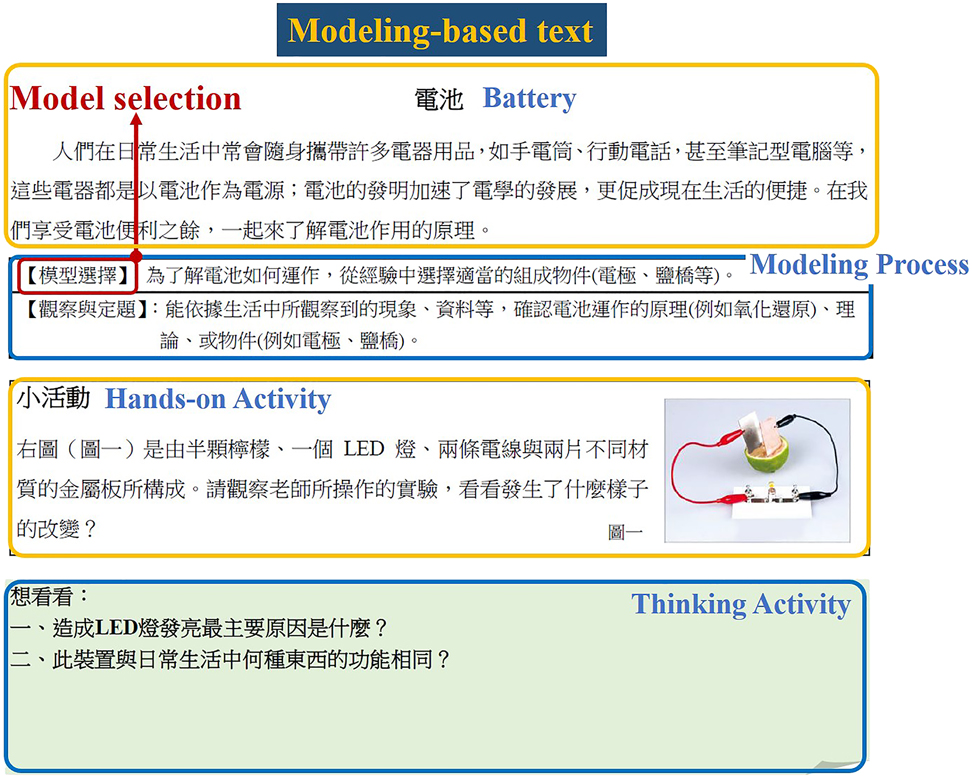

To promote such modeling competence in practice, Chiu and Lin further identified a four-step model titled DEAR (see Fig. 3), a cyclic model for promoting modeling competence. This DEAR model is designed to include model Development (D), model Evaluation (or Elaboration, E), model Application (A), and model Reconstruction (R) (see Fig. 5). It aims to operationalize the design, implementation, and evaluation of efficient modeling-based instruction. The DEAR modeling-based approach provides students with opportunities of constructing their own models within a specific context that they can explore and test their own models, apply their models in problem solving situation, and draw conclusions of such modeling practice. It allows students to learn science and to know how scientists practice science in an authentic context. A series of studies were conducted with the modeling approach at different levels of educational system ranging from elementary and middle schools, to senior high schools (e.g., [95], [96], [97], [98]). For example, the modeling-based text was designed specifically to investigate how students can benefit from the use of guided materials to empower their competence in modeling practice [97], [98], [99]. The reading materials were adopted from our previous work [96] and revised for learning chemical cells (Fig. 6). Taking an experiment about Daniel cell as an example, the components and relation of the Zn–Cu battery experiment were designed to depict the steps of modeling processes in the context of constructing a dual battery. The purposes of these activities were to get students acquainted with modeling processes and to be able to construct and modify their own model of cell battery through a series of guided inquiry. The interview questions were revised from Chang and Chiu [100] and its internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76. The results show that there was a significant difference in the posttest in the Modeling-based Instruction (MBI) group but not in the Comparative Group with no modeling-based approach. The difference between these groups was that MBI was presented with explicit descriptions and representations of modeling processes during instruction. In our study, we took this type of research one more step further. In the MBI group, the students were allowed to design their own procedures of conducting experiments, finding problems, proposing hypothesis, operating experiment, analyzing data and constructing models to interpret data collected in their own designs, and discussing with their chemistry teacher. The findings revealed that: (1) the students in the MBI group significantly outperformed the Comparative group on the overall content knowledge about electrochemical cell (p < 0.001), and (2) the students in the MBI group outperformed the Comparative group on overall modeling competence (p < 0.001). In other words, the results showed that the Modeling-Based Instruction not only facilitates students’ understanding of the fundamental concepts about chemical cells at the macroscopic level, it also supports students to construct the dynamic nature of chemical cells at the microscopic level (e.g., [97,98]). The modeling-based inquiry instruction about modeling processes allowed students to understand the concepts in a more systematic way. Also, such authentic learning environment provided opportunities to students to elaborate their ideas about scientific phenomenon and test their hypothesis with various designs in order to verify and apply in different situations (e.g., [89,101]). Research has argued that implicit and explicit guidance led students to different cognitive performance. In our study, we found the explicit instruction on modeling-based inquiry allowed students to focus their attention and efforts on authentic tasks with a well-designed framework so they could generate quality models of electrochemistry. Modeling-based inquiry has the potential to uncover the complexity of the concepts via systematic approaches in instruction.

DEAR modeling procedures.

An example of the learning materials with goal-oriented modeling steps explicitly stated.

It is clear in research of electric cells that multiple representations, lab instruction, and refutational text can facilitate students’ understanding of principles [102] as well as microscopic and symbolic representations of chemical cells [103,104]. But, these strategies did not successfully improved students’ understanding of the exchange of electrons in a chemical reaction and the directions of ions’ movement in the solution [102,105].

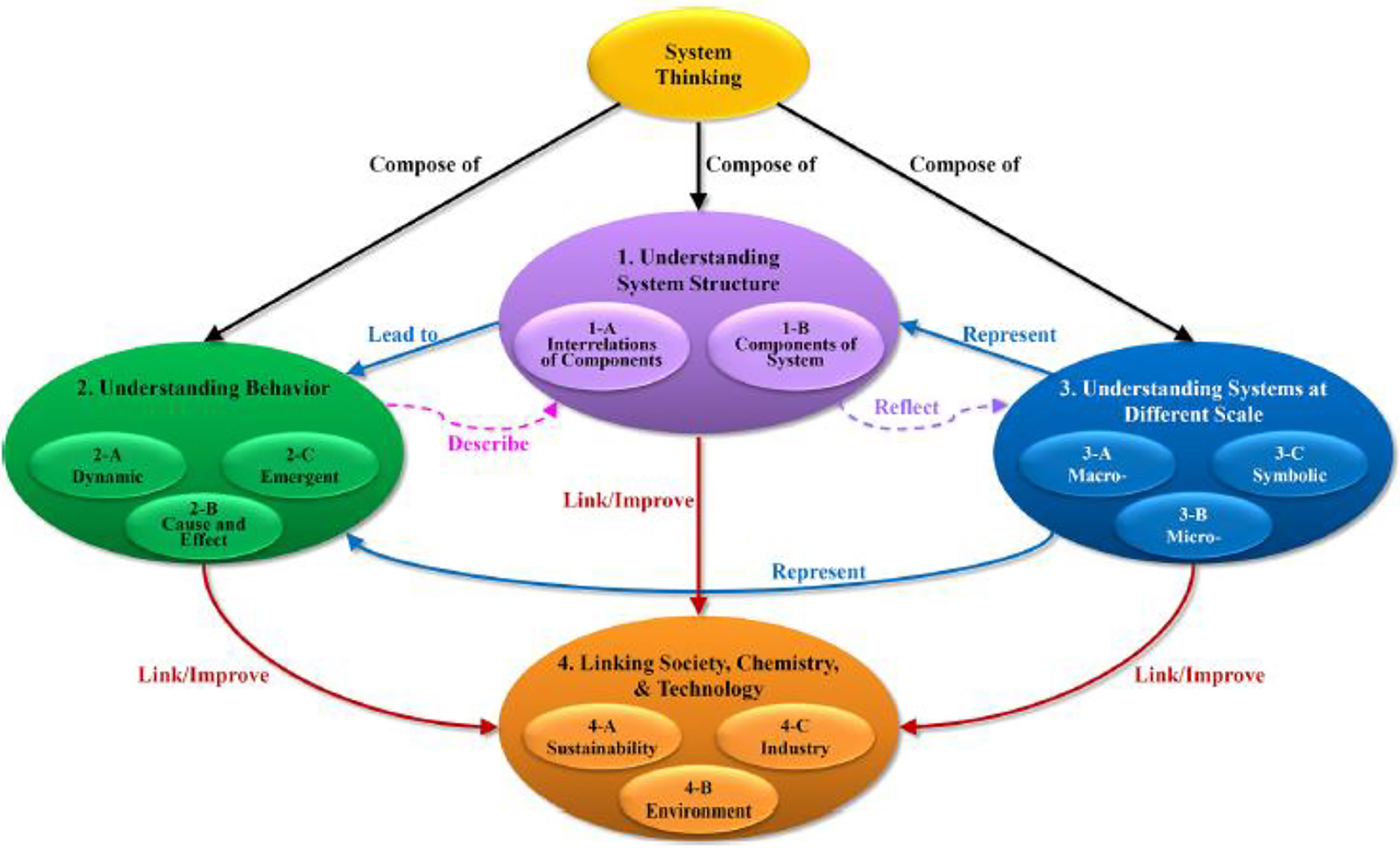

Systems thinking as learning tools

To extend the modeling research, I joined the IUPAC Systems Thinking project, led by Peter Mahaffy of Kings University, Canada, from 2017 to 2019. While Matlin et al. [106] recognized that chemistry has played its roles for the benefit of society and embraced systems thinking in relation to various interconnected systems both locally and globally, Mahaffy et al. [107] further clarified that systems thinking approaches emphasize the interdependence of components of dynamics systems and their interactions with other systems (such as societal and environmental systems). Chiu, Mamlok-Naman, and Apotheker [108] proposed a framework of systems thinking concept which featured with goal-based approach to the systems thinking for chemistry education, including (i) understanding systems structure, (ii) understanding complex behavior, (iii) understanding systems at a different scale, and (iv) linking society, chemistry, and technology (see Fig. 7). The authors adopted this framework to investigate whether chemistry curriculum reflects the emerging need of Systems Thinking in high schools in Israel, the Netherlands, Taiwan, and the USA. The results show that there is an international trend to enhance students’ thinking of interconnections of concepts and relevance in chemistry, yet the degrees of emphasis varied. In all four countries, the first three components are present in the standards of each country. It is recognized that preparing high school students to be literate about structures of systems and complex behavior and relations among the components in a system at different scales is crucial. However, the analysis showed that one of the main differences occurs in the linkage with society. Israel and the Netherlands both have a curriculum that includes sustainability, energy transition, and green chemistry. In Taiwan and in Israel, issues related to sustainability, environment, and society were covered (such as climate change, development and the use of energy, natural disaster and prevention), but not emphasis too much on industrial processes. In the USA, the focus is relatively more content-oriented approach (core ideas and crosscutting concepts), practice of the concepts in science and engineering and links may be made at a later stage. In short, learning expectations were not explicitly mentioned in the fourth dimension (i.e., sustainability). Systems Thinking can be considered as learning tools, instructional tools, and assessment tools to allow students to appreciate the contribution of chemistry in sustainable development as global citizens.

The framework of systems thinking Reprinted with permission from M. H. Chiu, R. Mamlok-Naaman, J. Apotheker. Identifying Systems Thinking Components in the School Science Curricular Standards of Four Countries. J. Chem. Educ., 96(12), 2814–2824 (2019). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

IUPAC projects and activities

In this last section, I would like to introduce the other side of my work on promoting chemistry education and gender equality through the IUPAC community, in particular, on Young Ambassadors for Chemistry (YAC), Flying Chemistry Educators Program (FCEP), and Global Gender Gap projects.

Young ambassadors for chemistry

I became the National Representative of Chemical Society Located in Taipei to the IUPAC in 2002. Ever since then, I was deeply involved in outreach chemistry education activities, including Young Ambassadors for Chemistry (YAC), the Flying Chemistry Educators Program (FCEP), and other IUPAC’s activities on promoting chemistry education. The former aims to promote public understanding of chemistry while the latter tries to provide countries with expertise needed to enhance their chemistry education (see https://iupac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2pages_FCEP_2017.pdf at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels).

The YAC was initiated for promoting public understanding and awareness of chemistry by Dr. Lida Schoen, a titular member of CCE and a senior chemistry educator from the Netherlands. The purposes of this project is to show teachers (all levels, but mainly secondary school) possible meaningful content, to relate to students’ daily life, to adopt student centered methodology (e.g. group work, discussions, collaboration with other subject teachers), and to raise local public awareness events.

The goals of the project are to train teachers to conduct chemistry experiments relevant to daily life (such as the chemistry behind cosmetics) and help teachers train their students to understand the contributions of chemistry to the modern world. The model used in YAC events is the “Train the Trainers” approach to strengthen teachers’ competence on teaching chemistry. Such approach can be extended from educators, teachers, to students and the public to match what the 17th Sustainable Development Goal, “Partnerships for the Goals”, is aiming for.

In general, the YAC has two parts: a 2–3 day workshop with school teachers and a half day event in a public venue (such as train station, park, or shopping malls, etc.) with students and the public including media coverage-students as Young Ambassadors for Chemistry The workshops on the chemical experiments chosen were mainly to introduce contextualized experiments and to bring about a better awareness of some local products to the participants. Compositions, properties, and applications were introduced and discussed during the workshops. To make the workshops and events successful, local organizers (in many cases, they are teachers) play important roles on organizing the event, such as contacting local government officials, industry representatives, school teachers, instructors in science centers, and/or university faculty as well as preparing the chemical compounds for the experiments. From our experiences working with teachers, we noticed that this type of preparation and implementation of daily life-experiences experiments allow them to build up their connections and capacity of hosting their own activities as a sustainable event after YAC has left. Meanwhile, the students gained their confidence and communicative skills while collaborating with their peers to create products under their teachers’ guidance and sharing their knowledge about the experiments with the local public. Learning by doing and learning by communicating with others have been evident.

As a member of the task group, I joined the project in the very beginning in 2004 when the project was launched in Taipei, Taiwan. Since 2004, YAC has organized 40 events in 29 different countries [109] led by Dr. Schoen. Among them, 14 events were supported by IUPAC and its Standing Committee on Chemistry Education (CCE) along with local financial agents. The others were supported by other organizations arranged by Dr. Schoen. The most recent one in Mongolia was organized by a titular member of CCE, Professor Masahiro Kamata. I had the privilege to collaborate and organize the events with them in the YAC projects sponsored by IUPAC and CCE (such as Cambodia, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Panama, the Philippines, & Thailand, etc.) (e.g., [109,110], please see few photos in Fig. 8). What I found from these activities were that most of the local teachers were enthusiastic to adopt our curriculum in their classrooms, and the students’ interest and motivation to learn chemistry increased as they engaged in in-context hands-on activities. While communicating with the public, the students gained confidence about their understanding of chemistry concepts and skills, and the public appreciated chemistry’s impact in their daily life. What is different in schools is that the learning of chemistry in school is often without contexts that are related to students’ daily life. Therefore, students lacked motivation to learn chemistry. The YAC program contributes its impact on raising people’s awareness of what chemistry can do for them and helps form a positive image of chemistry among both the students and the general public.

Examples of YAC events.

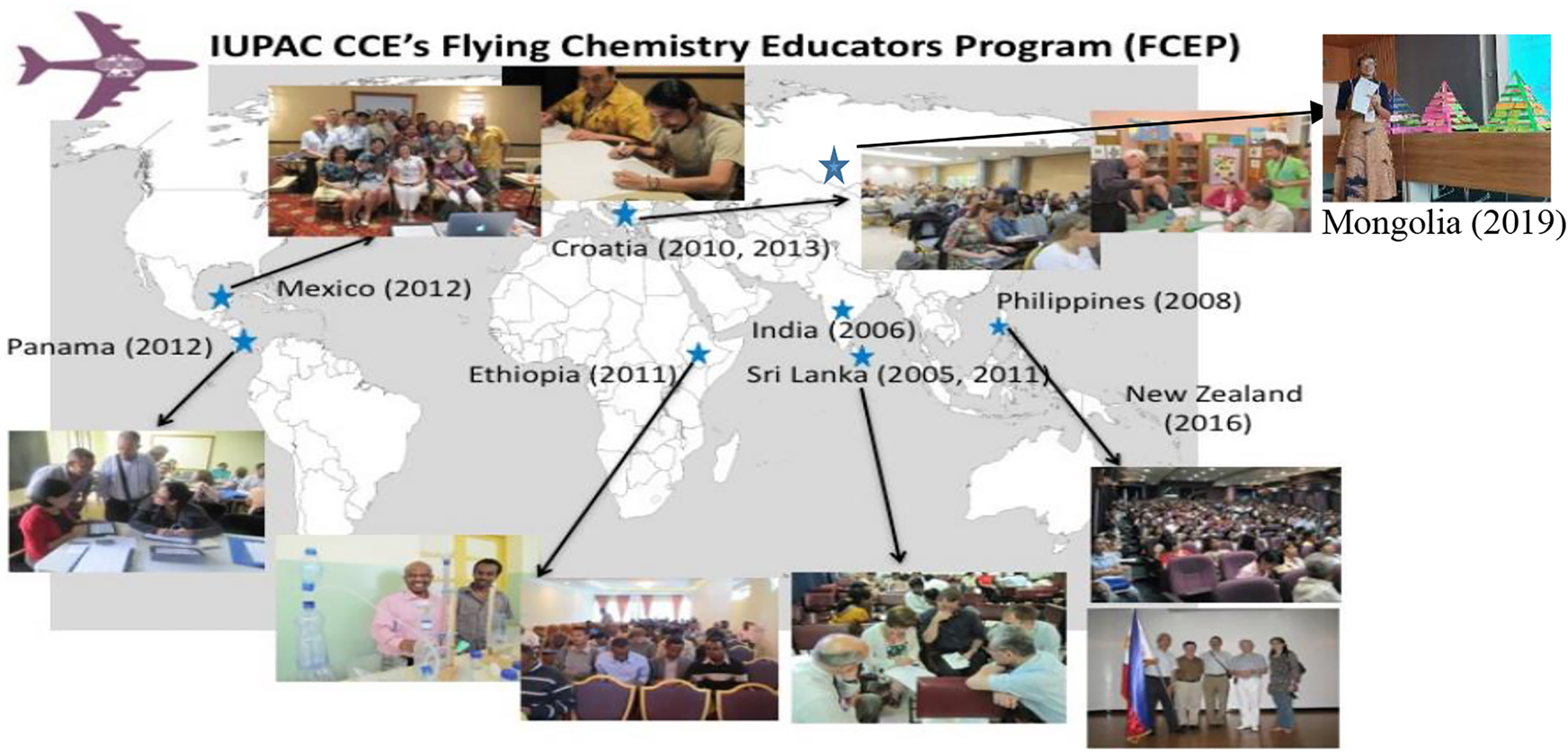

Flying Chemistry Educators Program

This FCEP program (formerly known as Flying Chemists Program, FCP) was initiated by Peter Atkins and Ram Lamba when they were members of IUPAC CCE in 2005. The FCEP was designed to provide emerging countries means to improve the teaching and learning of chemistry at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. Unlike the YAC program, FCEP provides a country with the expertise needed to strengthen its chemistry education program. Resource persons are expected to offer lectures and experiments based upon the local needs for transforming chemistry education. Therefore, FECP is also called a tailor-made program. Due to the unique requests from each country, the resources persons and programs provided to the host countries are different. For instance, the 1st Teacher Workshop in Croatia was held in 2010 through CCE’s titular member, Bob Bucat’s assistance. A group of researchers (including Onno de Yong from Sweden [previously the Netherlands], Tom Greenbow from the USA, Mordechai Livneh from Israel, Metodija Najdoski from North Macedonia, Bob Bucat from Australia, and myself) delivered lectures on various topics (teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge, alternative assessment, instructional strategies for teaching chemistry, etc.) and hands-on activities during four days in November, 2010. Ever since then, the chemistry teachers workshop is conducted every other year hosted by Professor Nenad Judaš and supervised by Professor Bob Bucat. One of my vivid memories of this trip was that all the teachers participated were deeply involved in the lectures, hands-on activities and the discussions of the possibility of implementation in schools all day every day for four days. This FCEP visit was a successful event because of everybody’s engagement. It cannot turn into a sustainable event in Croatia without the dedication and devotion of the organizers and the passionate teachers. There were other cases in other countries that touched my heart as well. What they can give and inspire us is much more than what we can offer. From their feedback, we were grateful to know we were doing the right thing for chemistry education.

Thus far, FCEP has been held in nine countries, namely, India (2005), Sri Lanka (2006), Philippines (2008), Croatia (2010), Ethiopia (2011), Mexico (2012), Panama (2012), New Zealand (2016), and Mongolia (2020) (please see Fig. 9). I had the privilege to join the last seven FCEP events over the past 15 years. I am always touched by the organizers, university lecturers, and school teachers for their passion and open-minded attitude to chemistry education, their steadfastness in face of the challenges, and the willingness to change in their practice.

IUPAC CCE’s Flying Chemistry Educators Programs (FCEP). Modified from https://iupac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2pages_FCEP_2017.pdf.

In sum, FCEP and YAC serve different purposes for promoting chemistry education, the former is to raise the public understanding of chemistry while the latter is to empower chemistry teachers in secondary schools and professors in higher education. Through these programs, we anticipate continued collaboration with local government officials and professionals, to generate short and long term impact and to provide tailor made resources and programs (such as emerging technology, learning and teaching strategies, assessment tools, development of curriculum, and hands-on activities, etc.) for future generations.

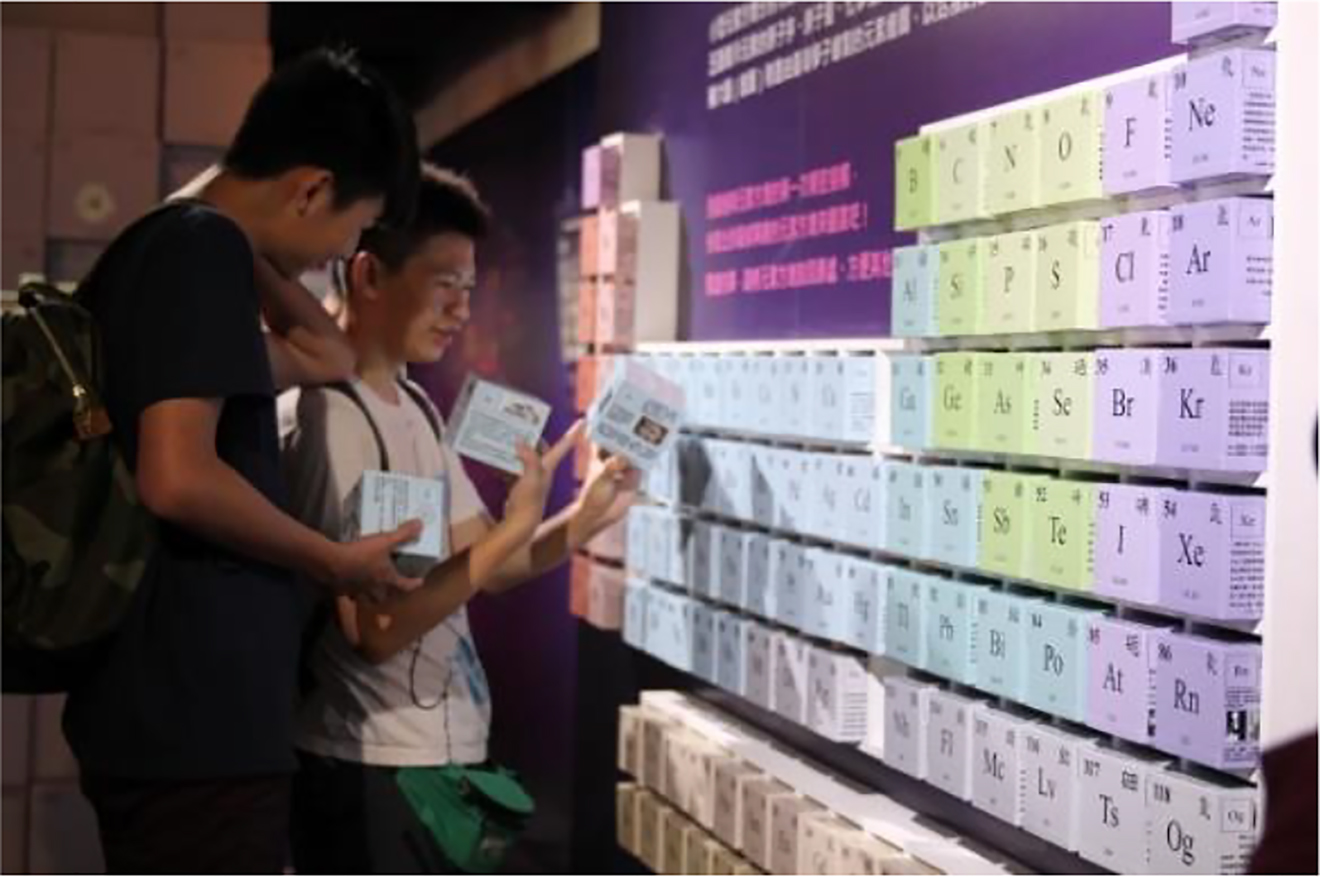

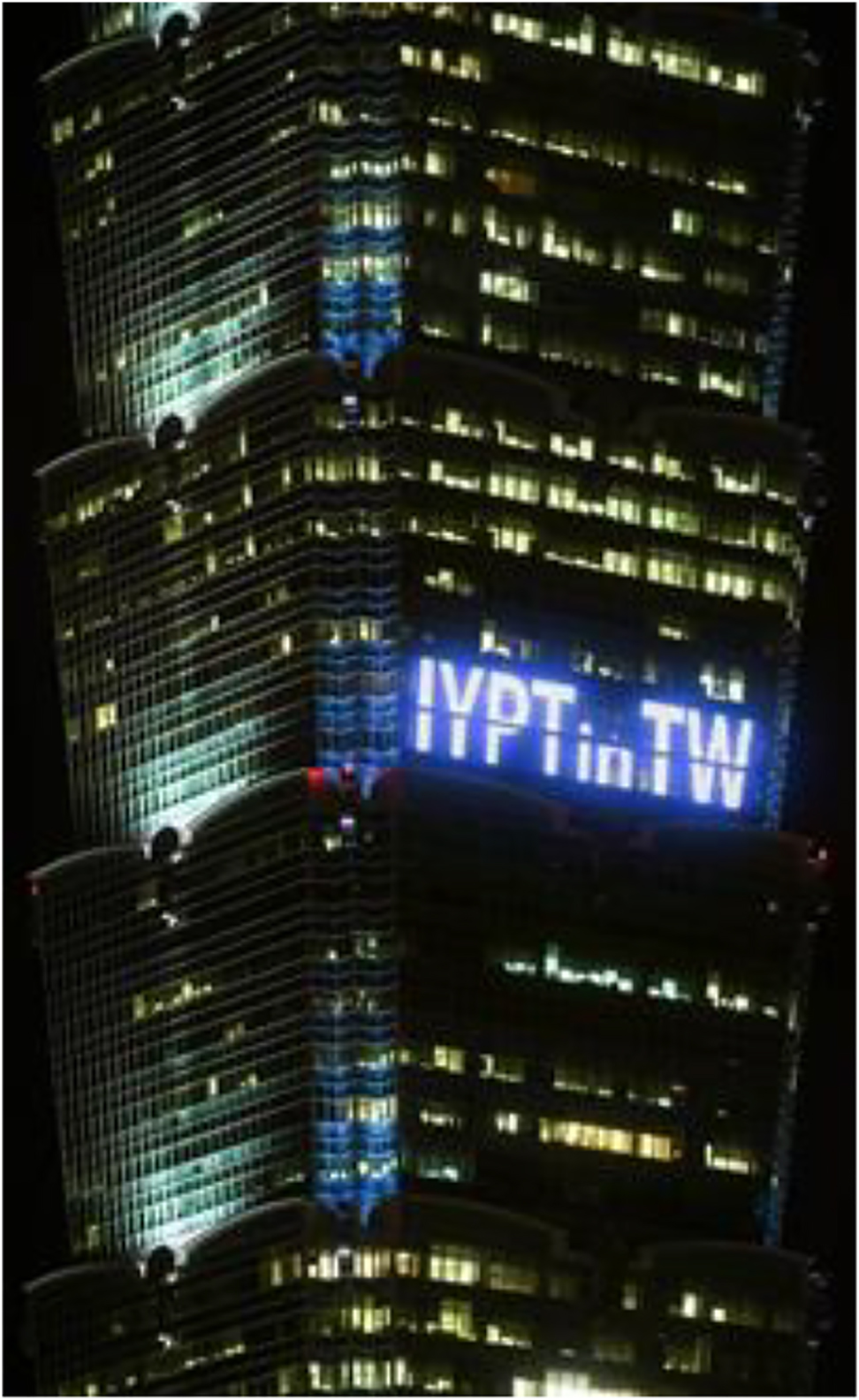

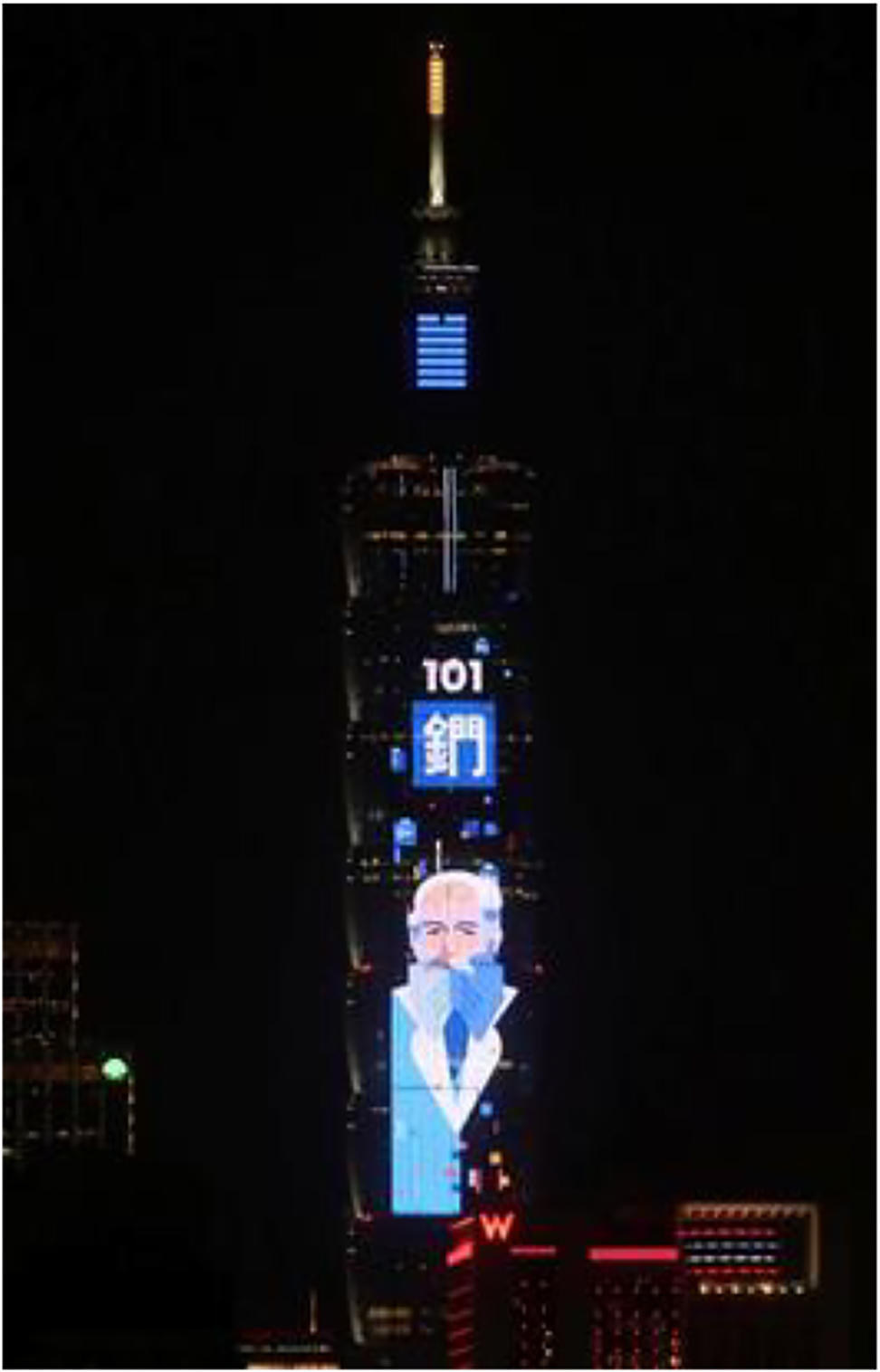

International Year of the Periodic Table

To celebrate United Nations’ International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT) in Taiwan, National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU) and the Chemical Society Located in Taipei (CSLT) held several events, supervised by Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and Ministry of Education (MOE). As the principle investigator, I had the privilege to organize several events to support IUPAC’s IYPT locally as well as globally, such as IYPT special exhibitions in the five major science museums, poster and teaching material on the Periodic Table competitions, online element challenges, decorated MRT trains, Taipei 101 Light Shows, a chemical elements collections App, and an invited talk at the closing ceremony in Tokyo (see Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14). The series of activities had reached audience that includes science educators, school teachers, students, and one million of the general public as well as international visitors.

118 Element cube exhibits.

Periodic table of Chemical Elements for persons with visual impairments (designed by S. P. Yang).

A close-up photo in showing the text “IYPT in TW” on Taipei 101.

Light show counting down from element 1 to 118, and then count back to element 101 and beginning with Mendeleev cartoon portrait.

Inside the compartment of the MRT in Taipei decorated with Mendeleev and Marie Curie as well as a cell phone composed of elements.

Gender gap project

Gender gap in science has been a well-known fact for decades. According to the report of UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), fewer than 30 % of the world’s researchers are women (see http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/women-science). To reduce such a gap, various initiatives were implemented but the gap was not reduced significantly and still exists, in particular, in academia.

The International Science Council (ISC) funded a unique three-year project in 2017–2019 called, “A Global Approach to the Gender Gap in Mathematics, Computing and Natural Sciences: How to measure it, how to reduce it?” [111]. This joint project involved: International Mathematics Union (lead 1), IUPAC (lead 2), and nine other international scientific unions, including the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP), the International Astronomical Union (IAU), the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS), the International Council for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (ICIAM), and the International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (IUHPST). The other four organizations are the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), through its project STEM and Gender Advancement (SAGA); Gender in Science, Innovation, Technology and Engineering (GenderIn-SITE); the Organization of Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD); and the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), through ACM-W. The main goal of the project was to investigate the gender gap in STEM disciplines through three principal tasks, globally and across disciplines. There were tasks involved, namely, (1) a global survey of scientists, (2) an investigation of scientific publication patterns, and (3) a database of good practices to encourage girls and young women to enter and be engaged in STEM fields.

In total, more than 32 000 respondents from 159 countries to the survey were collected and analyses, including 2698 chemists. The results revealed that systematic differences between the experiences of men and women still exist, across all regions, all disciplines, and all development levels. Of course, chemistry was not an exception. Several major findings were revealed: (1) More than six times of women than men in chemistry reported having personally encountered harassment at work or school; (2) Compared to men, women in chemistry tended to report more frequently that the progression of their careers was significantly slower than that of their peers since their careers were strongly affected by their decisions regarding children, marriage, or similar long-term partnership; (3) Females whose career or rate of promotion slowed significantly because they became a parent; (4) More females than males expressed that they felt discriminated against in the assessment or evaluation of their achievements because of their gender; and (5) The gender gap in science does not disappear even with increasing levels of regional economic development, as defined by the Human Development Index (please see the details in [111], [112], [113]).

As for the publication patterns analysis, data from Crossref was used to investigate the proportion of women in six prestigious chemistry journals that were suggested by IUPAC volunteers, namely, Chemical Reviews, the Journal of the American Chemical Society, Chemistry-A European Journal, Nature Chemistry, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, and The Chemical Record. The findings revealed that proportions of women authorship in these journals have been increasing steadily over the past 10–50 years (below 5 % in 1970 up to values in the vicinity of 20 % in the 2010s), a pattern that is not always repeated in other scientific disciplines [113]. The proportion of women authoring papers in top journals has remained static in mathematics and theoretical physics, while it increased in astronomy and chemistry even though the proportions were still low. However, according to a fruitful analysis on their publications by Royal Society of Chemistry [114], it is shown that women submit less often as corresponding authors than as first authors (23.9 % of submissions vs. 33.4 % respectively). Also, women are less likely to submit to journals with higher impact factors. In addition, papers by female corresponding authors are cited less than those from male corresponding authors (papers by female corresponding authors are cited on average 5.6 times; papers by male corresponding authors are cited 7.2 times) ([114], p. 22). Huang et al. [115] analyzed 1.5 million scientists whose publishing careers ended between 1955 and 2010 with a solid methodology. They found that across all years and disciplines, women account for 27 % of authors, however, there were only 12.0 % women authors in 1955 and that fraction steadily increased over the last century, reaching 35 % by 2005. They further pinpointed that in biology and chemistry, men have 19.2 % longer careers on average, resulting in a total productivity gender gap that exceeds 35.1 %. While female scientists are losing at a higher rate at every stage of their career in the academic system, it might not be sufficient to focus on the junior scientists alone. How to support gender-specific sustainability over academic career might be a cornerstone to be focused on for reducing the gender imbalance on productivity and impact [115]. In particular, ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation of publications for women scientists seems to be worse [116], [117], [118], [119].

To raise more attention about gender issues to academia, a collection of 16 articles ranging from scientific, mathematical to computing disciplines was published as a special issue on gender gap of Pure and Applied Chemistry [120]. Furthermore, to make the collaboration sustain, IUPAC and other international organizations are building on the project’s findings to advance gender equity in their disciplines. The Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science, SCGES, was instituted in 2020. IUPAC is a founding member of SCGES along with 15 other international partners.

To summarize, I worked with a group of great scientists who are highly invested in the gender gap issue and these activities provided me with opportunities to interact with scientists and science educators from all over the world and allowed me to develop leadership skills in the project. Their efforts and successes on promoting gender gap in STEM areas deserve recognition from all of us.

Concluding remarks

As a former secondary school chemistry teacher for three years before pursuing my doctoral degree in the United States, I always wondered why students have such difficulty in learning chemistry and how I could provide sense-making strategies to support their learning. During my past 30 years in academia, I have devoted myself to research topics relating to the understanding of students’ learning in chemistry, led integrated research on diagnosing students’ conceptions about key topics in chemistry, and developed instructional strategies to facilitate students’ learning of abstract and complex nature of chemistry. Via the innovative teaching methods, various techniques and products (e.g., augmented reality and virtual reality, [121]) were developed for chemistry teaching and learning, in particular, developing students’ models and modeling competence and providing students with opportunities to reflect on their learning in authentic scientific inquiry practice.

To put my research work into practice, I have also served in international scientific organizations as a volunteer since 2002, to promote science education, and in particular, for chemistry education. I have been deeply involved in various IUPAC projects and activities that inspired me to work with researchers, educators, teachers, and students on promoting chemistry education across the world. These activities also allowed me to interact with scholars who have devoted themselves to science and chemistry education selflessly. Although travels to some of the countries were long and difficult, on occasion we also ran into unexpected inconveniences and problems, all of these were forgotten when I met the enthusiastic teachers and saw students’ expression of satisfaction with our programs. Also, through these activities, I had opportunities to observe the progress of chemistry education and to develop visions, leadership, and knowledge of promoting chemistry education research and practice. This has allowed me to make my contribution to the societies, and meet with great fellows from across the globe, who were not only great to work with, but also awesome models to learn from.

Moreover, I love teaching and interacting with my students. I want my students not to underestimate themselves. They are, and should be, creative, critical, and open-minded to allow various possibilities to be explored. In particular, I would encourage female students and colleagues by saying “Be yourself, be confident, face the challenges and conquer them. And realize your potential for yourself and for others!” As Marie Curie said once, “Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”

It is a great honor to receive the award of 2021 IUPAC Distinguished Women in Chemistry/Chemical Engineering along with so many of my peers. I would like to take this opportunity to thanks my collaborators, teachers, students, colleagues, and friends who support me in various aspects in my career. I would also like to say congratulations to all the awardees as well as those who were nominated but not awarded. Everyone was so exceptional! Finally, I am in debt to my family who have supported me in many ways. For that I am grateful to them, in particular, to my husband, who supported me in my pursuit of my career without reservation.

Finally, I would like to quote the famous poem The Road not Taken by Robert Frost to end this article. Be brave to challenge your potential.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

References

[1] R. Driver. in Children’s Ideas in Science, pp. 145–169, Open University Press, London (1985).Suche in Google Scholar

[2] M. T. H. Chi. J. Learn. Sci. 142, 161 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1402_1.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] A. H. Johnstone. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 7, 75 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.1991.tb00230.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] A. H. Johnstone. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 1, 9 (2000), https://doi.org/10.1039/a9rp90001b.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] K. S. Taber. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 14, 156 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1039/c3rp00012e.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] V. Talanquer. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 33, 179 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690903386435.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] M. H. Chiu, J. W. Lin. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 42, 429 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20062.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] J. H. Wandersee, J. J. Mintzes, J. D. Novak. in Handbook of Research on Science Teaching and Learning, D. L. Gabel (Ed.), Macmillan, New York (1994).Suche in Google Scholar

[9] S. Vosniadou, X. Vamvakoussi, I. Skopeliti. in International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change, pp. 3–34, Routledge, New York (2008).Suche in Google Scholar

[10] M. H. Chiu. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 29, 421 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690601072964.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] D. F. Treagust. Res. Sci. Educ. 16, 199 (1986), https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02356835.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] D. Treagust. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 10, 159 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069880100204.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] D. F. Treagust. in Learning Science in the Schools: Research Reforming Practice, S. M. Glynn, R. Duit (Eds.), pp. 327–346, Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ (1995).Suche in Google Scholar

[14] H. P. Tam, L. A. Li. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 29, 405 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690601072949.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] S. C. Nurrenbern, M. Pickering. J. Chem. Educ. 64, 508 (1987), https://doi.org/10.1021/ed064p508.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] P. Johnson. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 20, 393 (1998), https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069980200402.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] M. J. Sanger, A. J. Phelps. J. Chem. Educ. 84, 870 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1021/ed084p870.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] R. Stavy. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 10, 553 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069880100508.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] D. L. Gabel, D. M. Bunce. in Handbook of Research on Science Teaching and Learning, D. Gabel (Ed.), pp. 301–316, Macmillan Publishing Co, New York (1994).Suche in Google Scholar

[20] S. Novick, J. Nussbaum. Sci. Educ. 62, 273 (1978), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730620303.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] C. S. Juang. The Misconceptions of Secondary School Students on Material Science and Organic Compounds. Annual Report to the National Science Council in Taiwan (in Chinese), National Science Council, Taiwan (2004).Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Y. R. Su. A Study of Elementary School Students’ Misconceptions and Causes About Atoms/Molecules/and Particles. Annual Report to the National Science Council in Taiwan (in Chinese), National Science Council, Taiwan (2004).Suche in Google Scholar

[23] W. W. Chiang, M. H. Chiu, S. L. Chung, C. K. Liu. J. Baltic Sci. Educ. 13, 596 (2014), https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/14.13.596.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] J. W. Lin, M. H. Chiu. in Multiple Representations in Physics Education, pp. 71–91, Springer, Cham (2017).10.1007/978-3-319-58914-5_4Suche in Google Scholar

[25] J. D. Herron. The Chemistry Classroom: Formulas for Successful Teaching, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC (1996).Suche in Google Scholar

[26] M. H. Chiu, C. J. Guo, D. F. Treagust. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 29, 379 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690601072774.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] L. S. Shulman. in A National Board for Teaching? In Search of a Board Standard, Paper commissioned for the Task Force on Teaching as a Profession, Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy, Stanford, CA, USA (1986).Suche in Google Scholar

[28] R. Bucat. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 5, 215 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1039/b4rp90025a.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] P. L. Grossman, P. Smagorinsky, S. Valencia. Am. J. Educ. 108, 1 (1999), https://doi.org/10.1086/444230.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] J. H. Van Driel, O. D. Jong, N. Verloop. Sci. Educ. 86, 572 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10010.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] M. Harle, M. Towns. J. Chem. Educ. 88, 351 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1021/ed900003n.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] O. D. Jong, J. H. Van Driel, N. Verloop. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 42, 947 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20078.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] S. Erduran. Sch. Sci. Rev. 84, 81 (2003).10.4414/saez.2003.09504Suche in Google Scholar

[34] J. C. Liang, C. C. Chou, M. H. Chiu. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 12, 238 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1039/c1rp90029c.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] J. W. Lin, M. H. Chiu. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 32, 1617 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690903173643.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] M. M. Cooper, H. Kouyoumdjian, S. M. Underwood. J. Chem. Educ. 93, 1703 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00417.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] M. R. Jiménez-Liso, L. López-Banet, J. Dillon. Sci. Educ. 29, 1291 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-020-00142-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] M. B. Nakhleh, J. S. Krajcik. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 31, 1077 (1994), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660311004.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] M. N. Petterson, F. M. Watts, E. P. Snyder-White, S. R. Archer, G. V. Shultz, S. A. Finkenstaedt-Quinn. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 21, 878 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1039/c9rp00260j.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] B. Ross, H. Munby. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 13, 11 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069910130102.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] H. J. Schmidt. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 13, 459 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069910130409.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] V. Kind. Beyond Appearances: Students’ Misconceptions About Basic Chemical Ideas, Durham University, Durham, 2nd ed. (2004), http://www.rsc.org/images/Misconceptions_update_tcm18-188603.pdf (accessed Jul 2, 2012).Suche in Google Scholar

[43] D. Cros, M. Chastrette, M. Fayol. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 10, 331 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069880100308.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] J. Oversby. Sch. Sci. Rev. 81, 89 (2000).10.4414/saez.2000.07036Suche in Google Scholar

[45] N. Ültay, M. Çalik. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 12, 57 (2016).Suche in Google Scholar

[46] M. Drechsler, J. Van Driel. Res. Sci. Educ. 38, 611 (2008), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-007-9066-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] J. W. Lin, M. H. Chiu. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 29, 771 (2007a), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690600855559.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] M. H. Chiu. An Investigation of Exploring Mental Models and Causes of Secondary School Students’ Misconceptions in Acids-Bases, Particle Theory, and Chemical Equilibrium. Annual Report to the National Science Council in Taiwan (in Chinese), National Science Council, Taiwan (2004a).Suche in Google Scholar

[49] J. W. Lin, M. H. Chiu. Chem. Educ. J. 9, 1 (2007b).Suche in Google Scholar

[50] J. W. Lin, M. H. Yen, J. C. Liang, M. H. Chiu, C. J. Guo. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2, 2617 (2016).Suche in Google Scholar

[51] G. J. Posner, K. A. Strike, P. W. Hewson, W. A. Gertzog. Sci. Educ. 66, 211 (1982), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730660207.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] P. W. Hewson. Eur. J. Sci. Educ. 3, 383 (1981), https://doi.org/10.1080/0140528810304004.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] P. W. Hewson. Eur. J. Sci. Educ. 4, 61 (1982), https://doi.org/10.1080/0140528820040108.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] P. W. Hewson, M. G. B. Hewson. Instr. Sci. 13, 1 (1984), https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00051837.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] P. Hewson, J. Lemberger. in Improving Science Education: The Contribution of Research, R. Millar, J. Leach, J. Osborne (Eds.), pp. 110–125, Buckingham, UK: Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press (2000).Suche in Google Scholar

[56] M. H. Chiu, C. C. Chou, C. J. R. Liu. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 39, 688 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.10041.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] M. T. H. Chi, J. D. Slotta, N. de Leeuw. Learn. InStruct. 4, 27 (1994), https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(94)90017-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] M. T. H. Chi. in International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change, pp. 61–82, Routledge, New York (2008).Suche in Google Scholar

[59] M. H. Chiu, S. L. Chung. in Concepts of Matter in Science Education, pp. 143–168, Springer, Dordrecht (2013).10.1007/978-94-007-5914-5_7Suche in Google Scholar

[60] R. T. White, R. F. Gunstone. Probing Understanding, The Falmer Press, London (1992).Suche in Google Scholar

[61] R. Duit, D. F. Treagust. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 25, 671 (2003), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690305016.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] M. H. Chiu, C. C. Chou, W. L. Wu, H. Liaw. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 45, 471 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12126.Suche in Google Scholar

[63] G. Lee, T. Byun. Res. Sci. Educ. 42, 943 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-011-9234-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] G. Lee, J. Kwon, S. S. Park, J. W. Kim, H. G. Kwon, H. K. Park. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 40, 585 (2003), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.10099.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] H. Liaw, Y. Yu, C. C. Chou, M. H. Chiu. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 30, 227 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-020-09863-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[66] J. M. Williams, A. Tolmie. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 625 (2000), https://doi.org/10.1348/026151000165896.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] S. Craig, A. Graesser, J. Sullins, B. Gholson. J. Educ. Media Mem. Soc. 29, 241 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1080/1358165042000283101.Suche in Google Scholar

[68] B. C. Heddy, G. M. Sinatra. Sci. Educ. 97, 723 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21072.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] R. Pekrun, E. Vogl, K. R. Muis, G. M. Sinatra. Cognit. Emot. 31, 1268 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1204989.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] A. Bellocchi, S. M. Ritchie. Sci. Educ. 99, 638 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21159.Suche in Google Scholar

[71] A. Bellocchi, S. M. Ritchie, K. Tobin, D. King, M. Sandhu, S. Henderson. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 51, 1301 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21170.Suche in Google Scholar

[72] P. Ekman. Calif. Mental Health Res. Dig. 8, 151 (1970).Suche in Google Scholar

[73] P. Ekman. in Handbook of cognition and emotion, T. Dalgleish, M. Power (Eds.), p. e320, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, New York, NY, Vol. 16 (1999).Suche in Google Scholar

[74] K. A. Descovich, J. Wathan, M. C. Leach, H. M. Buchanan-Smith, P. Flecknell, D. Framingham, S. J. Vick. ALTEX Alter. Anim. Exp. 34, 409 (2017), https://doi.org/10.14573/altex.1607161.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] H. L. Liaw, M. H. Chiu, C. C. Chou. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 15, 824 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1039/c4rp00103f.Suche in Google Scholar

[76] L. Breiman, J. Friedman, R. Olshen, C. Stone. Group 37, 237 (1984).Suche in Google Scholar

[77] M. H. Chiu, Y. R. Yu, H. L. Liaw, C. H. Lin. The Use of Facial Micro-Expression State and Tree-Forest Model for Predicting Conceptual-Conflict Based Conceptual Change, in Electronic Proceedings of the ESERA 2015 Conference. Science Education Research: Engaging Learners for a Sustainable Future, Part 1, J. Lavonen, K. Juuti, J. Lampiselkä, A. Uitto, K. Hahl (Eds.), pp. 184–191, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland (2016).Suche in Google Scholar

[78] M, H. Chiu, H. L. Liaw, Y. R. Yu, C. C. Chou. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 469 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12597.Suche in Google Scholar

[79] S. W. Gilbert. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 28, 73 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660280107.Suche in Google Scholar

[80] E. B. Fretz, H. K. Wu, B. Zhang, E. A. Davis, J. S. Krajcik, E. Soloway. Res. Sci. Educ. 32, 567 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022400817926.10.1023/A:1022400817926Suche in Google Scholar

[81] G. Sensevy, A. Tiberghien, J. Santini, S. Laubé, P. Griggs. Sci. Educ. 92, 424 (2008), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20268.Suche in Google Scholar

[82] L. K. Berland, C. V. Schwarz, C. Krist, L. Kenyon, A. S. Lo, B. J. Reiser. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 53, 1082 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21257.Suche in Google Scholar

[83] M. H. Chiu, J. W. Lin. Discip. Interdscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 1, 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0012-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[84] J. K. Gilbert, R. Justi. Modelling-Based Teaching in Science Education, Springer International Publishing, Basel, Switzerland, Vol. 9 (2016).10.1007/978-3-319-29039-3_4Suche in Google Scholar

[85] L. Grosslight, C. Unger, E. Jay, C. L. Smith. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 28, 799 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660280907.Suche in Google Scholar

[86] A. G. Harrison, D. F. Treagust. Sch. Sci. Math. 98, 420 (1998), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.1998.tb17434.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[87] R. Lehrer, L. Schauble. in The Cambridge handbook of: The learning sciences, pp. 371–387, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England (2006).10.1017/CBO9780511816833.023Suche in Google Scholar

[88] L. T. Louca, Z. C. Zacharia. Educ. Rev. 64, 471 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2011.628748.Suche in Google Scholar

[89] C. V. Schwarz, B. J. Reiser, E. A. Davis, L. Kenyon, A. Achér, D. Fortus, Y. Shwartz, B. Hug, J. Krajcik. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 46, 632 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20311.Suche in Google Scholar

[90] M. P. Jiménez‐Aleixandre, A. Bugallo Rodríguez, R. A. Duschl. Sci. Educ. 84, 757 (2000).10.1002/1098-237X(200011)84:6<757::AID-SCE5>3.0.CO;2-FSuche in Google Scholar

[91] M. Krell, D. Krüger. J. Biol. Educ. 50, 160 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2015.1028570.Suche in Google Scholar

[92] Ministry of Education in Taiwan. Curriculum Standards for Grades 1–12, Ministry of Education, Taipei (2018).Suche in Google Scholar

[93] NGSS Lead States. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, by States, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC (2013).Suche in Google Scholar

[94] J. D. Gobert, A. Pallant. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 13, 7 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jost.0000019635.70068.6f.10.1023/B:JOST.0000019635.70068.6fSuche in Google Scholar

[95] S. L. Chung, M. H. Chiu. Jiaoyu Kexue Yanjiu Qikan 57, 73 (2012).Suche in Google Scholar

[96] J. P. Jong, M. H. Chiu, S. L. Chung. Sci. Educ. 99, 986 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21164.Suche in Google Scholar

[97] M. H. Chiu, M. R. Zeng, S. L. Chung. Modeling-based instruction and assessment for learning electrochemistry at the secondary school. in The NARST International Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018, Mar (2018).Suche in Google Scholar

[98] M. R. Zeng, M. H. Chiu. Chin. J. Sci. Educ. 29, 137 (2021).Suche in Google Scholar

[99] M. H. Chiu, M. R. Zeng, S. L. Chung, J. P. Jong, L. Y. Wang, Y. T. Liao, S. Y. Syu. Modeling-Based Inquiry Instruction for Promoting 10th Graders’ Modeling Competencies and Conceptual Understanding of the Periodic Table, Paper Presented at the NARST 94th Annual International Conference, 7–10 April (2021).Suche in Google Scholar

[100] H. Y. Chang, M. H. Chiu. J. Sci. Educ. 10, 69 (2009).Suche in Google Scholar

[101] J. S. Krajcik, P. E. Simmons, V. N. Lunetta. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 25, 147 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660250206.Suche in Google Scholar

[102] A. S. L. Loh, R. Subramaniam. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 55, 777 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21439.Suche in Google Scholar

[103] K. Osman, T. T. Lee. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 12, 395 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-013-9407-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[104] E. M. Yang, T. Andre, T. J. Greenbowe, L. Tibell. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 25, 329 (2003), https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690210126784.Suche in Google Scholar

[105] G. Tsaparlis. Isr. J. Chem. 59, 478 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1002/ijch.201800071.Suche in Google Scholar

[106] S. A. Matlin, G. Mehta, H. Hopf, A. Krief. Nat. Chem. 8, 393 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.2498.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[107] P. G. Mahaffy, A. Krief, H. Hopf, G. Mehta, S. A. Matlin. Nat. Rev. Chem 2, 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-018-0126.Suche in Google Scholar

[108] M. H. Chiu, R. Mamlok-Naaman, J. Apotheker. J. Chem. Educ. 96, 2814 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00298.Suche in Google Scholar