Abstract

To expand the chemotherapeutic potential of platinum complexes, different approaches have been followed, two of the most relevant being their administration as the prodrug Pt(iv) and encapsulation in nanocarriers. Herein, we demonstrate how neuromelanin may become a good bioinspiration for the synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs), combining both approaches. For this, complex PtBC reacts with sodium periodate, inducing a melanization process and the formation of nanoparticles. In vitro results on non-malignant human fibroblast cells (1Br3G), human cervical cancer, murine glioma (GL261), and human ovarian cancer confirmed its therapeutic efficacy. The role of the Pt(iv) ion on the cytotoxicity effects was confirmed by comparison with the results obtained for a family of nanoparticles obtained with nordihydroguaiaretic acid under the same experimental conditions. Finally, intranasal administration of the NPs in orthotopic glioblastoma multiforme murine models in female C57BL/6 mice showed excellent in vivo biodistribution and tolerability. Overall, this innovative approach represents a step toward more specific and less toxic therapies in the field of cancer chemotherapy.

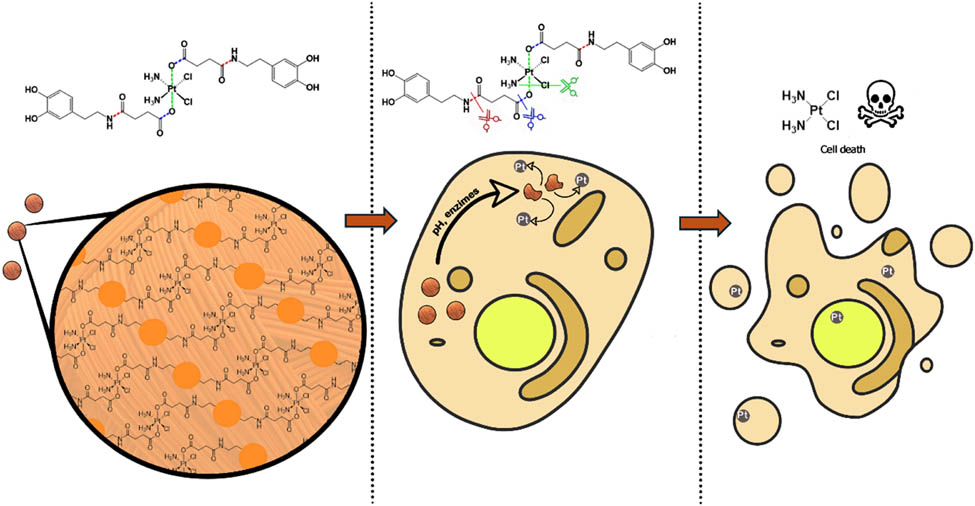

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The serendipitous discovery of the antitumor effectiveness of cisplatin (CDDP) in the late 1960s [1–5] marked a crucial moment in cancer chemotherapy [6–8]. Since then, platinum (Pt)-based anticancer drugs have shown well-defined mechanisms of action and significant therapeutic effects, making them widely used in clinical settings. However, despite their evident efficacy, especially against ovarian tumors, Pt(ii) complexes are non-specific chemotherapeutic drugs that induce systemic toxicity [9–12]. To mitigate secondary effects, various strategies have been employed. The first approach involves the use of Pt(iv) produgs, which have an octahedral geometry. As a result, Pt(iv) complexes are less susceptible to ligand substitution and only reduced to the active Pt(ii) form upon tumor cell internalization, reducing toxicity and secondary administration adverse effects [13–17]. The second strategy involves the use of nanoformulations [18–23]. Owing to their small size and large surface area, nanoparticles enhance both drug bioavailability and permeability retention in tumor tissues [24]. Additionally, nanoparticles can transport and increase the solubility of various therapeutic agents, protect them from degradation and mononuclear phagocyte action, enable targeted release, and allow for real-time in vivo monitoring as well as combined anticancer therapies [25–34]. Accordingly, Pt-based nanoformulations have significantly reduced toxicity and improved drug delivery to tumors, with a concomitant increase in survival rates [35]. However, despite these pioneering successful results, the use of nanoparticles is still at an incipient stage, with the need for more studies to be developed.

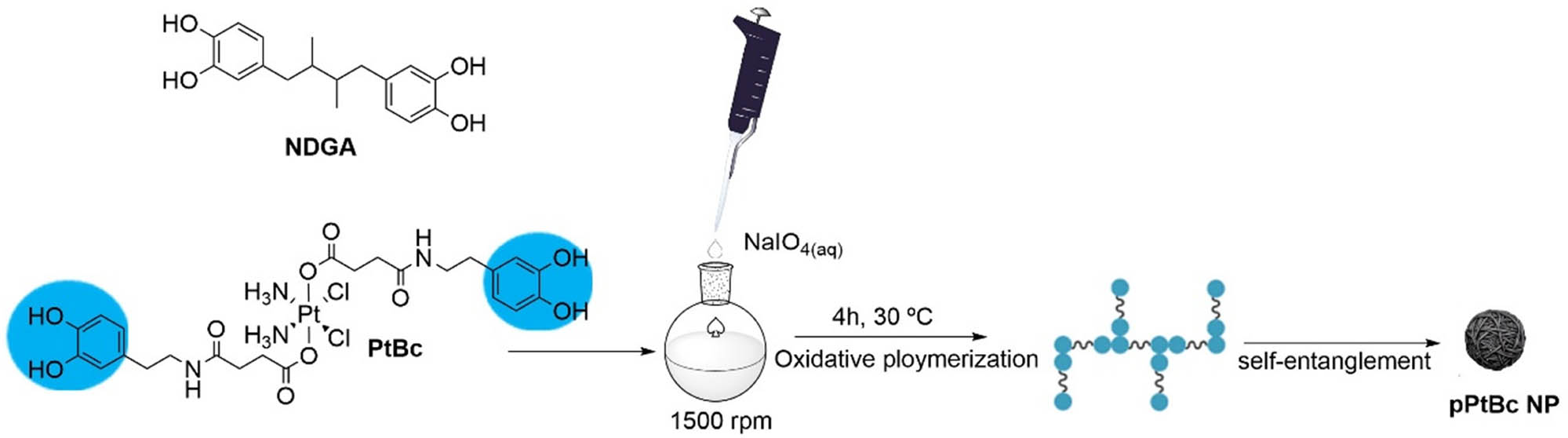

The use of bioinspired approaches in searching for new and innovative solutions to cancer treatment has represented a step forward [36]. Of special interest has been polydopamine in its nanoparticulated state [37,38]. In this context, inspired by neuromelanin particles found in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra, we recently reported the bis-catechol functionalized Pt(iv) prodrug complex PtBC (Scheme 1) and its use to form coordination polymeric nanoparticles (Pt–Fe NCPs) because of the affinity of catechol units to chelate iron metal ions [39]. In vivo intranasal administration of Pt–Fe NCPs in orthotopic preclinical GL261 glioblastoma (GB) multiforme tumor-bearing mice showed enhanced platinum tumor accumulation and prolonged survival of the tested cohort, in some cases even to complete cure [40]. These successful initial findings encouraged us to investigate alternative possibilities to optimize the chemotherapeutic effect of this novel family of nanoparticles. One potential approach involves polymerization of PtBC through a bioinspired melanization process by reaction with sodium periodate, without the need for iron metals [41,42]. In addition to ensure more robust nanoparticles and controlled platinum release, with this approach, we aim to significantly increase the platinum encapsulation efficiency. A schematic representation for the synthesis of the novel nanoparticles (referred to from now on as pPtBC NPs) is shown in Scheme 1.

Schematic protocol for the synthesis of polymeric pPtBC NPs, by reaction of PtBC with sodium periodate (see section 2.3 for more details). For comparison purposes, related nanoparticles were obtained with the same methodology but NDGA as ligand, exhibiting a related topology to that of PtBC, but lacking the Pt(iv) ion.

The in vitro therapeutic efficacy of pPtBC NPs in non-malignant human fibroblast cells (1Br3G), human cervical cancer (HeLa), murine glioma (GL261), and human ovarian cancer showed excellent results. This efficiency was unequivocally attributed to the presence of Pt(iv) ions. This comparison was made with the toxicity results obtained for a related family of nanoparticles obtained under the same experimental conditions but replacing PtBC with bis-catechol nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA). NDGA is a polyphenol with well-described antitumoral capabilities and structurally comparable to that of PtBC; elongated with a sterically bulky center and ending catechol groups, but lacking the Pt core. On top of that, in vivo biodistribution and tolerability of pPtBC NPs have also been thoroughly evaluated via intranasal administration using orthotopic GB murine models.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Solvents and starting materials were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain) and employed in their original state without additional purification unless otherwise specified. PtBC was synthesized following the methodology reported earlier [39].

2.2 Characterization methods

The size distribution and surface charge of the nanoparticles (0.5 mg/mL) were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a ZetasizerNano 3600 instrument (Malvern Instruments, UK), with a size range limit from 0.6 to 6 nm. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained using a SEM (FEI Quanta 650 FEG) at an acceleration voltage of 5–20 kV. SEM samples were prepared by drop-casting the corresponding dispersions of nanoparticles (NPs) on aluminum tape followed by solvent evaporation under room conditions. Before analysis, the samples were metalized with a thin layer of platinum (thickness of 5 nm) using a sputter coater (Emitech K550). NPs size from SEM imaging was obtained using analytical software ImageJ (Copyright (C) 1989, 1991 Free Software Foundation, Inc.) using the integrated particle analysis software from binary file images taken from 8-bit format files from SEM imaging. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using a Tensor 27 spectrometer (Bruker Optik GmbH, Germany) with HBr pellets. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (PerkinElmer Inc. Germany) measurements were recorded using 194Pt, 195Pt, and 196Pt as Pt tracers.

2.3 Synthesis of pPtBC NPs and pNDGA NPs

Synthesis of pPtBC NPs. PtBC (10.0 mg, 0.013 mmol) was dissolved in 6 mL of a 1:1 mixture of ethanol:MilliQ water. Sodium periodate (5.3 mg, 0.024 mmol) was dissolved in 0.4 mL of MilliQ water. The sodium periodate solution was then added dropwise to the PtBC solution and heated to 30°C. Addition was carried out with a syringe pump, and addition was carried over a period of 1 h (6.7 µL/min) under vigorous stirring (1,500 rpm). The reaction was then allowed to evolve for 3 h at 30°C in the dark. The product was then isolated by centrifugation (10 min at 12,000 rpm), washed multiple times with ethanol and water, and resuspended in water for storing, yielding pPtBC NPs as a brown turbid suspension in a 3.0 mg yield (for more information, see Supporting Information S1).

Synthesis of pNDGA NPs. NDGA (20.0 mg, 0.066 mmol) was dissolved in 28 mL of a 1:1 mixture of ethanol:MilliQ water. Sodium periodate (28.2 mg, 0.132 mmol) was dissolved in 4 mL of MilliQ water. The sodium periodate solution was then added dropwise to the NDGA solution. Addition was carried out with a syringe pump, and addition was carried over a period of 1 h (66.7 µL/min) under vigorous stirring (1,500 rpm). The reaction was then allowed to evolve for 3 h in the dark. The product was then isolated by centrifugation (10 min at 12,000 rpm), washed multiple times with ethanol and water, and resuspended in water for storing, yielding 4.5 mg of the pNDGA NPs as a brown turbid suspension (for more information, see Supporting Information S3).

2.4 Drug release assay

Drug release from pPtBC NPs was evaluated using the dialysis method. Concentrated pPtBC NPs (1 mg/mL) were reconstituted in 1 mL of Milli-Q water and placed in dialysis bags (MWCO = 6,000–8,000 Da, where MWCO stands for Molecular Weight Cut-Off). The bags were then immersed in sealed beakers containing 40 mL of PB buffer with pH values set at 7.4 and 5.5. The beakers were then kept at 37°C with gentle stirring throughout the study. At predetermined time points, a 500 mL aliquot was withdrawn from the dialysate and immediately replaced with an equal volume of fresh buffer. The quantity of released Pt was determined using ICP-MS.

2.5 Cell lines culture

Cell lines, including the human cervical cancer cell line HeLa, non-malignant human fibroblast cell line 1Br3G, murine GB cell line GL261, and a pair of human ovarian cancer cell lines, A2780 and its cisplatin-resistant counterpart A2780/cis, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Virginia, USA 30–4,500 K). Specifically, HeLa cells were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM), 1Br3G in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM), GL261 and A2780 in Roswell park memorial institute medium 1640 (RPMI 1640), and A2780/cis in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1 μM of cisplatin. All culture media were enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco®, Invitrogen, UK), 0.285 g/L glutamine, 2.0 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. The cells were grown as adherent monolayers and maintained in an incubator (HERAcell, 150i, Thermo Scientific) at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a relative humidity of 95%, except for 1Br3G, which was maintained at 10% CO2. All cell culture media, FBS, supplements, antibiotics, trypsin, and Trypan Blue were procured from Fisher Scientific (Gibco®, Invitrogen, UK).

2.6 In vitro cytotoxicity assays

Cells (HeLa, 1Br3G, GL261, A2780, and A2780/cis) in the exponential growth phase were seeded into a 96-well plate (Corning, USA) under optimal conditions. Each cell type was seeded at specific densities: HeLa at 2,000 cells/well, 1Br3G at 3,000 cells/well, GL261 at 4,000 cells/well, and both A2780 and A2780/cis at 3,000 cells/well. Specifically, cisplatin-containing cell culture media were replaced with fresh RPMI media without the drug 4 h before seeding. After 24 h of incubation, fresh media containing compounds (pPtBC NPs, PtBC, and cisplatin [CDDP]) at various concentrations (0, 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200 μM referred to Pt concentration) were added, and the plates were incubated for either 24 or 72 h. Subsequently, 10 μL of PrestoBlue® (0.15 mg/mL, Thermo Scientific, USA) was added to each well. The plates were then further incubated for 4 h before measuring the fluorescence at 572 nm with excitation at 531 nm using the microplate reader Victor 3 (Perkin Elmer, USA). For 1Br3G, the incubation time with PrestoBlue® was extended to 7 h to ensure a sufficient difference in fluorescence intensity between concentrations. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism (version 7.0). The calculated IC50s were obtained by Graphpad Prism.

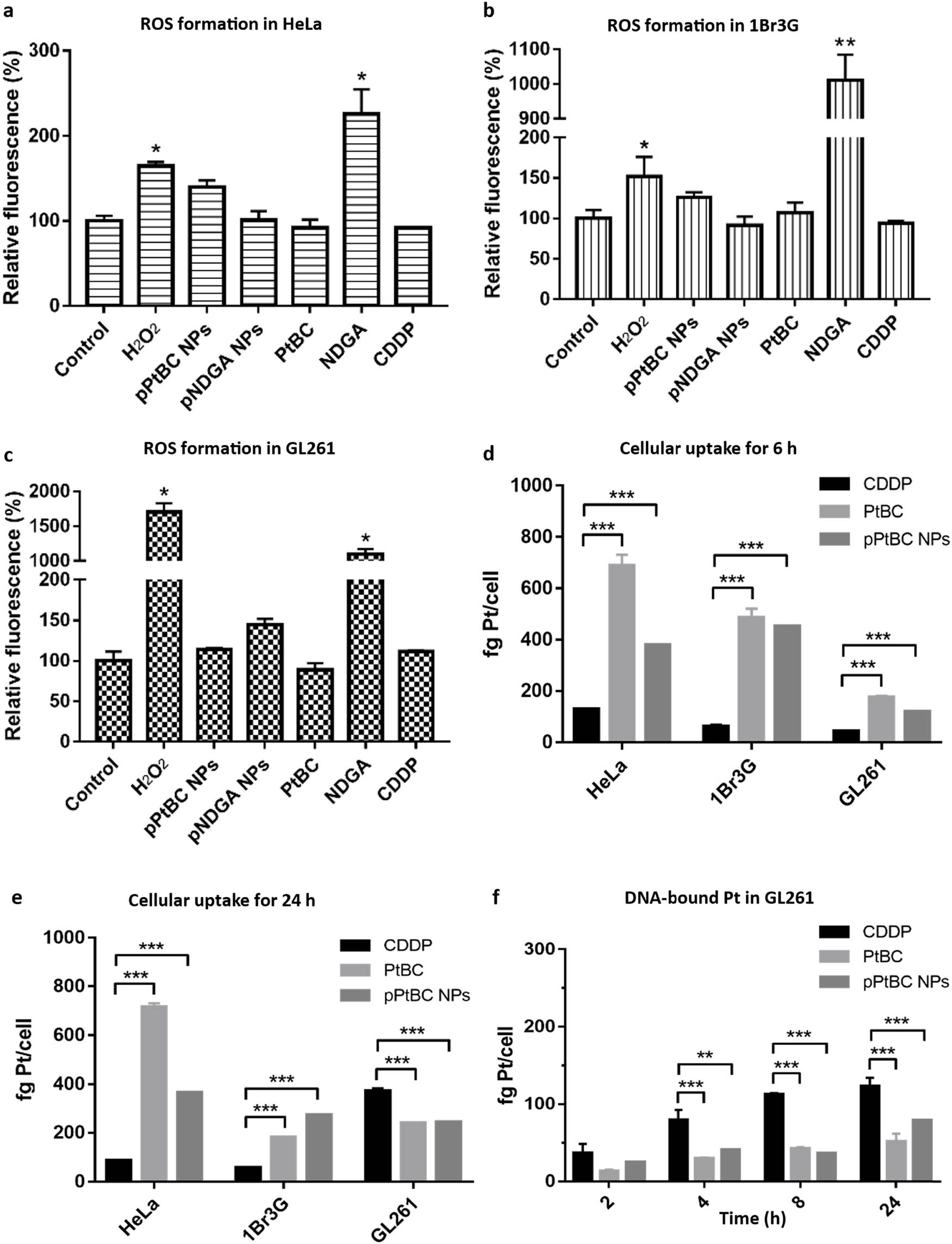

2.7 Estimation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation

HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells were seeded in black 96-well plates (Corning, USA) at a density of 20,000 cells at each well to ensure full confluence. Following a 24-h incubation, the spent medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed with serum-free medium. Subsequently, pre-warmed PBS containing the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFCDA) at a final working concentration of 10 mM was added, and the cells were incubated for 30 min. Once the probe was internalized, the buffer containing the probe was replaced with either medium alone or media-containing compounds (H2O2, pPtBC NPs, pNDGA NPs, PtBC, NDGA, and CDDP) at the IC50 concentration for 24 h. A positive control with 0.1 mM H2O2 was included for comparison. After 24 h, the fluorescence of each well was measured at 530 nm with excitation at 485 nm using a microplate reader (Victor 3, Perkin Elmer, USA). This experiment was independently repeated in triplicate, and the results were normalized based on the negative control, which was loaded with the dye but lacked drug treatment.

2.8 Cellular internalization studies

HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells were seeded in six-well plates (Corning, USA) at a density of 300,000 cells at each well with 1.5 mL of media. Following a 24-h incubation, the old media were replaced with 1 mL of fresh media with or without CDDP, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs at a concentration of 0.1 mM referred to as Pt. The treated cells were allowed to internalize the compounds for 6 and 24 h at the incubator. Another cellular uptake assay was conducted with a reduced concentration of Pt (10 μM) and extended time points of 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. The media were promptly removed, and the cells were washed twice with cold PBS to eliminate excess compounds. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of trypsin was added to each well for 3 min, and a twofold volume of fresh media was added to neutralize the trypsin. After taking an aliquot from each well for cell counting, the remaining cell suspensions were collected into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Corning, USA) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 4 min. The supernatants were discarded, and the cell pellets were stored at −80°C for further quantification by ICP-MS.

2.9 DNA-bound Pt

To elucidate the mechanism of action of our PtBc NPs, we conducted DNA extraction and quantification using ICP-MS to measure the DNA-bound Pt after a 24-h uptake in HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells. Cells in exponential growth phase were seeded onto cell culture dishes under optimal conditions for each cell line, reaching 50–60% confluence within 24 h before treatment. Subsequently, CDDP, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs were added at a concentration of 0.1 mM referred to Pt, and the cells were allowed to incubate for an additional 24 h. Following this incubation period, media containing drugs were removed, and the cells were washed, trypsinized, collected by centrifugation, and rinsed twice with cold PBS to eliminate excess drugs.

The resulting cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (pH 8.0, 150 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.5% [w/v] SDS). The pellets in the buffer were incubated on ice for 15 min and then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. To each supernatant, 0.1 volume of RNase A was added at 0.2 mg/mL and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, Proteinase K was added at 0.1 mg/mL and incubated for 3 h at 56°C. A volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 in volume, Thermo Scientific®) was added and mixed gently. After centrifugation of 3 min at 15,000 rpm, aqueous phases containing DNA were transferred into sterile tubes. DNA was precipitated with 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and 1 volume of absolute ethanol at −20°C overnight. Then, the DNA samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 rpm, and finally, DNA samples were dried and resuspended in 0.1 mL of elution buffer (pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). The concentration of isolated DNA was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm using a NanoDropTM 1,000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The remaining samples were frozen for ICP-MS analysis.

2.10 Sample digestion treatments for ICP-MS measurement

For ICP-MS preparation, all glassware underwent a 48-h immersion in 20% HNO3, whereas plasticware was soaked in 5% HNO3 for 4 h prior to use. The samples were digested using a wet digestion method, with procedures tailored to specific materials.

2.10.1 Chemical samples

The precise amount of the sample was weighed using an analytical balance and transferred to a vial. Concentrated ultrapure HNO3 (69%, Ultratrace®, ppb-trace analysis grade, Scharlab, Spain) was then added. The samples were left in a fume hood for 48 h for complete digestion, then diluted with 0.5% (v/v) ultrapure HNO3 for subsequent measurements.

2.10.2 Cell pellets

Cell pellets were resuspended in approximately 100 mL of concentrated ultrapure HNO3 (69%, Ultratrace®, ppb-trace analysis grade, Scharlab, Spain) and left to digest overnight. The samples were heated to 90°C until the suspensions became clear. Subsequently, the samples were diluted with 0.5% (v/v) ultrapure HNO3 to appropriate volumes for later measurements.

2.10.3 Tissues

Tissues were combined with T-PERTM buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a ratio of 10 mL/g, then cut into small pieces and subjected to sonication using an ultrasonication microtip (Branson Digital Sonifier 450, Emerson, USA) over repetitive cycles of 10 s active and 15 s inactive with an amplitude of 40%. The tissue suspensions were then added with aqua regia (all ppb-trace analysis grade) and heated up to 300°C, with 30% H2O2 added in the later digestion process until the suspensions became clear. The clear solutions were then transferred and diluted with 0.5% (v/v) ultrapure HNO3 to appropriate volumes for the determination of metal contents using ICP-MS.

2.11 Animal studies

Animal experiments and care were conducted in collaboration with duly accredited personnel. Healthy female C57BL/6J mice aged 8–12 weeks, with a body weights ranging from 20 to 24 g, were used for in vivo investigations. The mice were procured from Charles River Laboratories (Charles River Laboratories Internacional, L’Abresle, France) and were accommodated in the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona’s animal facility (Servei d’Estabulari, https://estabulari.uab.cat/; accessed on 24 March 2022). Ethical approval for all animal study protocols was obtained from the local ethics committee (Comissió d’Ètica en l’Experimentació Animal i Humana, https://www.uab.cat/etica-recerca/; accessed on 24 March 2022), following regional and state legislation (protocol CEEAH-4859). The animals were kept in cages with unrestricted access to standard food and water, maintaining consistent housing and environmentally controlled conditions.

2.12 Preclinical model generation and treatment administration

Tumors were induced via intracranial stereotactic injection of 105 GL261 glioma cells in the caudate nucleus. To facilitate intranasal administration, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane for a minute and positioned in a supine orientation. Each nostril received a 2 μL dosage of the pPtBC NPs formulation, spaced with a 1–2 min interval between administrations. The well-being of treated animals was observed, and those exhibiting signs of distress were humanely euthanized in adherence to ethical considerations.

2.13 In vivo MRI studies

Mice bearing GL261 GB tumors underwent MRI scans for tracking alterations in tumor location and volume. The investigations were conducted using a 7T BioSpec 70/30 USR spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin GmbH) at the joint nuclear MR facility of UAB and CIBER-BBN, Unit 25 of NANBIOSIS. In brief, T2-weighted MRIs were acquired using a rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement sequence. Key acquisition parameters included a repetition time (TR)/effective echo time (TEeff) of 4,200/36 ms, echo train length of 8, field of view of 19.2 mm × 19.2 mm, matrix size of 256 × 256 (75 μm/pixel × 75 μm/pixel), 10 slices, slice thickness (ST) of 0.5 mm, inter-slice thickness (IT) of 0.1 mm, number of averages (NA) of 4, and a total acquisition time of 6 min and 43 s. The collected MRI data underwent processing using ParaVision 5.1 software on a Linux platform.

To calculate tumor volume from the MRI acquisitions, ParaVision software delineated regions of interest (ROIs) to measure tumor area in each slice. Subsequently, mice tumor volumes were computed using the following formula:

Here, TV is the tumor volume, AS indicates the number of pixels within the ROI defined by tumor boundaries in each MRI slice, ST is the slice thickness (0.5 mm), IT is the inter-slice thickness (0.1 mm), and 0.0752 signifies the individual pixel surface area in mm².

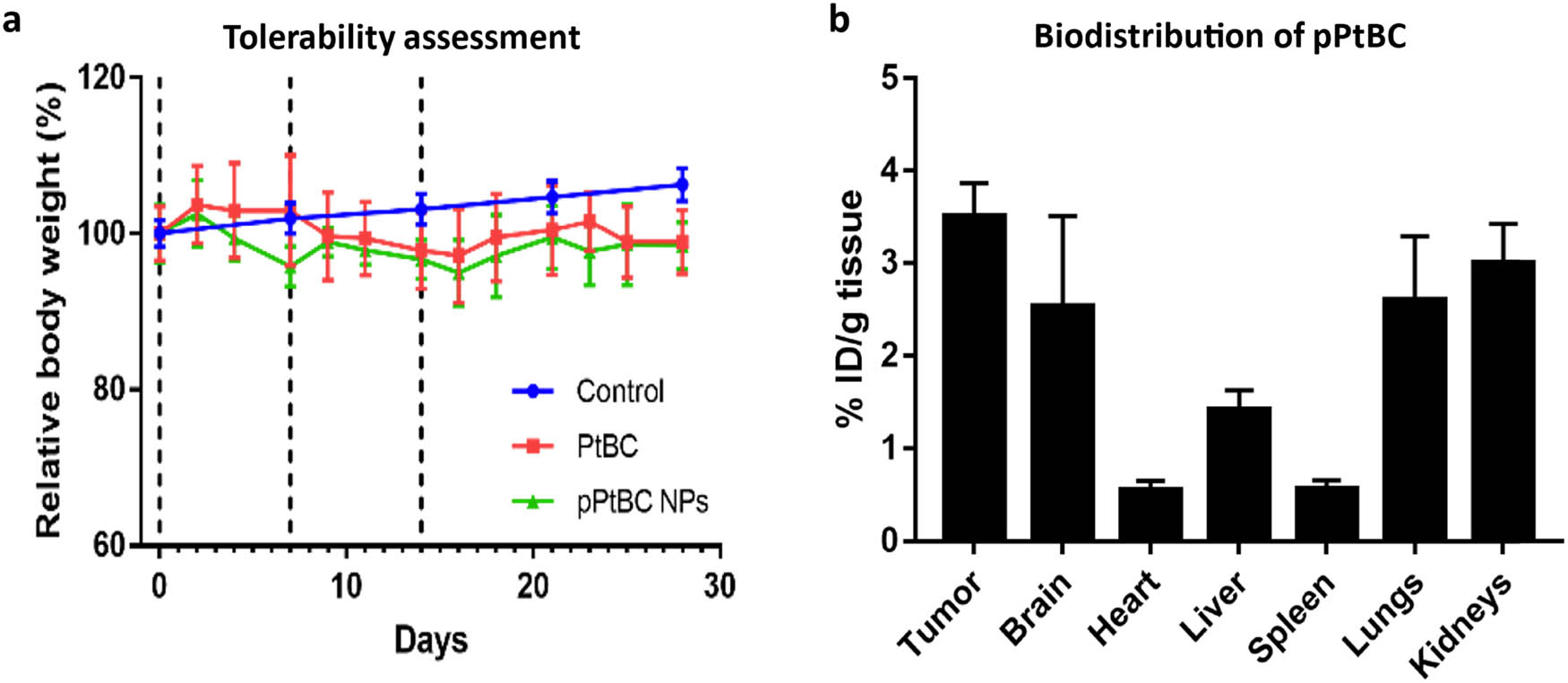

2.14 Tolerability assays

Healthy female C57BL/6 mice, aged 8–12 weeks and weighing 20–24 g, were randomly assigned to three groups: control, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs, with three mice in each group. The drugs were administered intranasally using a micropipette, while the mice were lightly anesthetized and positioned horizontally for the procedure. The dosage started at 0.9 mg Pt/kg body weight and gradually increased incrementally to 1.5 mg Pt/kg over 3 weeks, with doses administered weekly. Initial body weights were recorded, and subsequent monitoring occurred three times a week. Throughout the 4-week study, veterinary personnel closely monitored mice for mortality, food and water consumption, and suffering clinical signs. To assess tolerability in treated mice, we used statistical comparisons among groups utilizing a one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test for three or more groups. A statistically significant P value was considered when less than 0.05.

2.15 In vivo biodistribution study

For the study, Pt NCPs were administered through intranasal delivery at a dosage of 1.5 mg Pt/kg body weight in GL261 GB-bearing mice. After 1 h, the mice were euthanized, and organs such as the brain, tumor, heart, lungs, spleen, liver, and kidneys were removed and weighed. These collected tissues underwent homogenization in T-PER buffer using an ultrasound probe with 30% amplitude and cycles of 10 s on and 15 s off. Next, the samples underwent centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. A portion of each supernatant was extracted for total protein quantification, while the remaining fraction was subjected to digestion following the previously outlined procedure. This prepared the samples for ICP-MS measurement, enabling the determination of Pt concentration.

2.16 Statistical analyses

Unless stated otherwise, values are given as the average plus or minus the standard error. A two-tailed Student’s t-est for independent measurements was employed for making comparisons. Survival rate comparisons were conducted using the log-rank test. The significance threshold for all tests was set at p < 0.05, and values falling between 0.05 and 0.1 were regarded as a “trend toward significance.”

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and characterization

PtBC, obtained as previously described (for more information, see Supporting Information S1), was dissolved in a 1:1 ethanol:water solution and afterwards oxidized by slow and controlled addition of a NaIO4 aqueous solution under vigorous stirring at 30°C to yield pPtBC NPs as spherical nanoparticles of 157 ± 0.5 nm and good homogeneity across all samples, as characterized by SEM imaging (Figure 1a). This size was in accordance with DLS, values, which exhibit a hydrodynamic size of 234.6 ± 0.5 nm and a very low PDI of 0.087 ± 0.022 (ζ-potential was −37.1 ± 0.95 mV) (Figure 1c and d). FT-IR showed peaks in the 1,200–1,400 cm−1 characteristic catechol region, though with a notable shift, the disappearance of the peaks at 1,283, 1,327, and 1,197 cm−1 and the appearance of a new broad peak at 1,279 cm−1 from oxidation products. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry gave a platinum content value of 17%, slightly lower than the expected one of 24% for the theoretical formula; the decrease in Pt content w/w could be attributed to a nanoparticle weight increase due to the incorporation of sodium, and other ions present in the media, into the nanoparticle as a result of the oxidation process dopamine is undergoing (for more information, see Supporting Information S2).

(a) Representative SEM images of pPtBC NPs under a 5 nm Pt thin film coating for imaging. (b) Cumulative Pt release from pPtBC NPs at pH 5.4 and 7.4 and in the presence of GSH (2 and 10 mM). (c) Representative size distribution by DLS. (d) Representative ζ-potential of pPtBC NPs by DLS.

pNDGA NPs were obtained following the same oxidative polymerization. SEM images showed the formation of spherical and homogeneous-shaped nanoparticles of 260 ± 0.5 nm and good homogeneity across all samples. DLS experiments showed sizes of 214.2 ± 0.8 nm with a very low PDI of 0.07 ± 0.02 and a ζ-potential of −28.7 ± 0.5 mV. FT-IR characterization showed a noticeable shift of the peaks characteristic of the catechol region (1,200–1,400 cm−1), and once more the disappearance of peaks at 1,393, 1,354, 1,325, and 1,292 cm−1 along with the appearance of new broad peaks at 1,279 and 1,725 cm−1.

3.2 Platinum-controlled release

A dialysis methodology was used to obtain the 48-h platinum release profile of pPtBC NPs dispersed in a pH 7.4 phosphate buffer solution, mimicking in vitro physiological media, and a pH 5.5 environment simulating the lysosomal conditions [43]. The results, as quantified by ICP-MS, are shown in Figure 1b. In both scenarios, a typical release profile is observed with a disparity in release rates under acidic conditions. The release after 48 h at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 was 43.20 ± 6.92% Pt and 64.34 ± 0.9%, respectively.

Another important consideration is the reductive power, or redox homeostasis, of cells. Glutathione (GSH) and its oxidized form, glutathione disulfide, play pivotal roles in maintaining these redox capabilities within cells. In normal cells, their intracellular concentrations typically range from 1 to 10 mM, but in cancer cells, this concentration can increase up to fourfold [44]. To delve further into the influence of cellular redox state, we conducted the release profile experiments under varying GSH concentrations of 2 and 10 mM, while maintaining the same previous conditions. At pH 7.4 and 2 mM GSH, the measured Pt release was 55.7 ± 2.63%, while it increased up to 78.23 ± 1.05% at 10 mM GSH. On the contrary, pH 5.4 and a 2 mM GSH concentration, the Pt release was already high, reaching 79.16 ± 2.53%, increasing up to 97.7 ± 0.92% at 10 mM. As observed, the combined effect of decreasing pH and the presence of GSH notably increases the release rates in these nanosystems.

3.3 Cytotoxicity effects

The in vitro cytotoxicity of PtBC and pPtBC NPs was evaluated and compared to cisplatin (CDDP) against a set of cancer cell lines: human cervical cancer cell line HeLa, the non-malignant human fibroblast cell line 1Br3G, murine glioma cell line GL261, the ovarian cancer cell line A2780, and the cisplatin-resistant counterpart cell line A2780/cis. It is worth noting that previous studies have shown that nanocarriers can bypass the efflux of resistant cells to free drug, leading to modulating or overcoming cancer cell resistance [45,46]. The assessments were conducted using the well-established PrestoBlue method, with data collected at both 24- and 72-h intervals. The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were calculated using Graphpad Prism and are summarized in Table 1. At 24 h, PtBC and pPtBC NPs showed comparable cytotoxicity for HeLa and 1Br3G, while in the case of GL261 and A2780 cells, the IC50 value for PtBC is almost half of that found for pPtBC NPs. It is worth mentioning that IC50 values in both cases are comparable but slightly higher than those found for CDDP, except for ovarian A2780 cells where, interestingly, PtBC exhibits higher toxicity. After 72 h of exposure, the cytotoxicity difference between PtBC, pPtBC NPs, and CDDP diminished, approaching comparable IC50 values for Hela (even smaller for pPtBC NPs), GL261 cells, and A2780. In the case of 1Br3G and A2780/cis, both PtBC and pPtBC NPs exhibit similar values, but double those found for CDDP; even pathways for NPs uptake and detoxification are greatly influenced by the cell type [47].

IC50s of CDDP, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs against a panel of cell lines

| Compounds | Cell lines | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | 1Br3G | GL261 | A2780 | A2780/cis | ||

| 24 h | CDDP | 15.98 ± 1.04 | 45.07 ± 4.60 | 5.61 ± 0.28 | 13.95 ± 1.24 | 23.68 ± 1.74 |

| PtBC | 29.94 ± 1.04 | 56.09 ± 1.18 | 17.40 ± 1.08 | 10.98 ± 0.56 | 18.39 ± 1.85 | |

| pPtBC NPs | 22.09 ± 1.09 | 56.30 ± 1.32 | 33.56 ± 1.36 | 18.44 ± 2.19 | 31.40 ± 2.28 | |

| 72 h | CDDP | 2.34 ± 0.30 | 4.63 ± 0.42 | 2.16 ± 0.26 | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 5.22 ± 1.21 |

| PtBC | 1.85 ± 0.36 | 10.80 ± 0.60 | 4.17 ± 0.12 | 2.59 ± 0.33 | 9.12 ± 0.69 | |

| pPtBC NPs | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 8.01 ± 0.72 | 4.64 ± 0.05 | 3.10 ± 0.32 | 10.50 ± 0.84 | |

The in vitro cytotoxicity of NDGA and pNDGA NPs was also tested for comparison purposes against the same panel of cancer cells (the results are shown in Table 2). As can be seen there, NDGA showed very low cytotoxicity in all the cell lines except for A2780 or A2780/cis, where surprisingly IC50 values are comparable and even smaller than CDDP. It is worth mentioning that pNDGA NPs were non-toxic in a given concentration range with cell viability close to 100% in all cell lines either for 24 or for 72 h.

IC50s of NDGA and pNDGA NPs against a panel of cell lines

| Compounds | Cell lines | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | 1Br3G | GL261 | A2780 | A2780/cis | ||

| 24 h | NDGA | 164.15 ± 0.02 | NTb | 109.45 ± 1.95 | 8.94 ± 0.69 | 15.67 ± 2.14 |

| pNDGA NPs | NTb | NTb | NTb | NTb | NTb | |

| 72 h | NDGA | 55.65 ± 6.21 | 14.20 | 81.73 ± 2.40 | 7.82 ± 0.39 | 12.96 ± 1.48 |

| pNDGA NPs | NTb | NTb | NTb | NTb | NTb | |

b NT represents non-toxic, meaning the viability of cells remains close to 100% even at the maximum concentration.

3.4 ROS effects

Compounds containing catechol moieties, typically found in polyphenols and flavonoids, have been recognized for their diverse range of beneficial properties, including hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and even anticancer effects [48]. However, it is worth noting that the oxidation of these catechol moieties can also lead to the generation of ROS, potentially resulting in excessive oxidative stress that could harm cells, leading to toxicity, damage, and inflammation [49]. Therefore, it is of particular interest to investigate ROS contribution to the cytotoxic properties of PtBC and pPtBC NPs, using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-DCFCDA in HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells [50]. After 24 h of exposure, strong DCF fluorescence was only observed in all the cells treated with NDGA and H2O2, the positive control. Neither PtBC nor the polymeric pPtBC/pNDGA NPs triggered the formation of ROS in any of the tested cell lines (Figure 2a–c). Notably, CDDP itself did not induce ROS generation.

ROS generation triggered by different compounds and pPtBC NPs in (a) HeLa, (b) 1Br3G, and (c) GL261 cells. The concentration of H2O2 was 0.1 mM, pNDGA NPs at 0.2 mM, and other agents at their corresponding IC50s. Cellular uptake of CDDP, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs in HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells for (d) 6 h and (e) 24 h. All drugs were incubated at a concentration of 100 µM referred to Pt. (f) DNA-bound Pt after exposure to CDDP, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs for 24 h at a concentration of 100 µM referred to Pt. Each value is represented as mean ± SE of three independent experiments. *stands for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.001, *** for p < 0.0001.

3.5 Cellular uptake and DNA-bound Pt

The therapeutic efficacy of an anticancer agent greatly depends on its capacity to accumulate within the target, i.e. its intracellular concentration. This accumulation is directly related to several factors, including uptake pathways kinetics, metabolism, and/or cellular efflux. Increasing the lipophilicity of NPs’ surface was also reported to increase the affinity to the cell membrane, including those of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), as opposed to hydrophilic NPs [51]. The polymeric nature of pPtBC NPs could potentially facilitate their transport, enhancing their cellular uptake within target tumor cells.

PtBC and pPtBC NPs (0.1 mM referred to as Pt) were co-incubated with HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells for 6 h and afterwards digested and analyzed using ICP-MS. As depicted in Figure 2d, the cellular uptake exhibited the following trend PtBC > pPtBC NPs > CDDP. CDDP and PtBC are both small molecules that typically enter cells through passive diffusion, though cellular internalization for CDDP is dominated by the carriers present on the cell membrane, especially copper transporters and organic cation transporters [52,53]. The carrier-mediated endocytosis requires energy consumption, unlike passive diffusion, which might explain the lower cellular uptake of CDDP compared to PtBC. NPs commonly rely on endocytosis pathways, which are also energy dependent. With a relatively high extracellular concentration, PtBC potentially enters cells more easily than the NPs.

After a 24-h exposure (Figure 2e), the cellular uptake of these compounds remained relatively stable in HeLa cells, suggesting a rapid internalization already after 6 h. However, in the other two cell lines, uptake levels continued to fluctuate even after 24 h. In 1Br3G cells, the intracellular level of CDDP was comparable to that of 6 h, while the levels of PtBC and pPtBC NPs decreased dramatically. However, they were still significantly higher than the CDDP level. Interestingly, the trend in GL261 cells inverted totally. The cellular uptake of CDDP increased 8.5 times in comparison to the intracellular concentration at 6 h, surpassing the levels of PtBC or pPtBC NPs.

Additional studies to determine DNA-bound platinum were also done by incubating CDDP, PtBC, and pPtBC NPs (100 µM) with HeLa, 1Br3G, and GL261 cells for 24 h. Then, nuclear DNA was extracted, purified, and quantified by absorbance; meanwhile, the amount of Pt bound to the DNA was quantified using ICP-MS. As illustrated in Figure 2f, the DNA-bound platinum concentration from intrinsically active CDDP was notably higher than that of PtBC and pPtBC NPs in all cell lines, indicating that not all Pt agents entering cells can effectively access the nucleus to bind to DNA. It is worth mentioning that PtBC and pPtBC NPs exhibited comparable anticancer activities over 24 h, suggesting that their cytotoxicity is not limited to Pt–DNA adducts. Increasing reports demonstrated that Pt agents can also bind to other cellular macromolecules such as RNA and proteins and may even induce immunogenic effects [54,55]. For instance, Bose et al. reported platinum complexes with high cytotoxicity like cisplatin, yet it exhibited no DNA binding at all [56].

3.6 In vivo tolerability and biodistribution via Intranasal administration

For these studies, we selected intranasal administration compared to other systemic routes, such as intravenous and intraperitoneal injections. Currently, there is a lack of reports detailing the biodistribution of Pt nanostructured agents through this pathway, even though it could hold significant value for future treatments.

3.6.1 Safety and tolerability

PtBC and pPtBC NPs were assessed in a dose-escalation experiment using wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 J mice. Increasing doses (0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg Pt/kg body weight) were administered over 3 consecutive weeks [57]. Body weight, water/food consumption, and mouse behavior were evaluated three times over 4 weeks, overlaying with the normal body weight progression of C57BL/6 J mice (control). As shown in Figure 3a, the body weights of all treatment groups remained stable as the control group till the end of the study, indicating an absence of evident systemic toxicity. Notably, no treatment-related adverse effects such as mortality, body weight loss, food consumption, or other clinical signs of mucosa damage were observed for all mice during the study relative to control animals. Even at the highest dosage of 1.5 mg Pt/kg body weight, all mice maintained good health status during the study.

(a) Mice tolerability assessment of mice for PtBC and pPtBC NPs over 4 weeks. Both drugs were administered in incremental doses of 0.9, 1.2–1.5 mg Pt/kg body weight via intranasal weekly, n = 3. The control group, comprising n = 360, had data sourced from Jackson Laboratory (https://www.jax.org/jax-mice-and-services/strain-data-sheet-pages/body-weight-chart-000664). (b) Biodistribution of pPtBC NPs in mice bearing GL261 tumors 1 h after administration. Mice were intranasally administered with pPtBC NPs at a dose of 1.5 mg Pt/kg and sacrificed 1 h post-administration. Dashed lines stand for administration days. Each value is represented as mean ± SE, n = 3.

3.6.2 Biodistribution

To assess the accumulation in tumors, these studies were done on mice bearing orthotopic GB tumors with an average size of 24.96 ± 2.7 mm3 and a body weight of 22.7 ± 0.2 g, at the highest dose of 1.5 mg Pt/kg, as part of the tolerability assessment. As depicted in Figure 3b, 1 h post-intranasal administration, Pt predominantly accumulated in the GB tumor, followed by the kidneys, lungs, and brain. Minimal accumulation was observed in the liver, spleen, and heart. Pt retention in the tumor reached the highest level at 3.51 ± 0.36% ID/g, while in the brain, lungs, and kidneys, it measured 2.53 ± 0.98%, 2.6 ± 0.69, and 3.0 ± 0.43% ID/g, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed in Pt retention between the tumor and the organs. However, Pt accumulation in the tumor significantly surpassed that in the heart, liver, and spleen. When considering the tumor and brain collectively, Pt accumulation in the central nervous system was higher than in other organs.

4 Conclusions

A new family of bioinspired platinum-based nanoparticles has been successfully synthesized and characterized. At 72 h, the toxicity of the nanoparticles is close to that of the monomeric unit (in the case of HeLa and 1Br3G even improved), and in both cases, similar or even better than the gold standard cisplatin drug. Additional advantages of the bioinspired nanostructuration are: (I) our NPs present a much better cellular uptake over short periods of time, allowing for a better drug accumulation over the typical short windows before renal clearance; (II) NPs exhibit an effective long-lasting release: even its improved cellular uptake, the cytotoxicity at 24 h and the DNA-bound Pt is lower for NPs while slightly better at 72 h; (III) our NPs favour intranasal administration, overcoming the low drug concentration that cisplatin-based drugs have always struggled to achieve; and (IV) our system exhibits activation and release patterns (pH and GSH sensitivity), classically employed to avoid undesired side effects because of off-target drug activation.

An additional advantage of our approach is the expected reduction of undesired side effects, thanks to (I) the use of an unactive Pt(iv) precursor that is reduced intracellularly to the active Pt(ii) (a widely reported phenomena with several Pt(iv) complexes exhibiting this phenomena [58–60] and the corresponding mechanisms) [61–64]; and (II) the relevance of pH and GSH-sensitive pPtBC NPs to effectively activate the release of the platinum cargo at the desired specific target, thanks to the hydrolysis potential of amide bonds and reduction susceptibility of Pt(iv) complexes in the presence of a reductive environment breaking any axially bonded substitution and realizing Pt(ii) cargo. [65–67] Finally, in vivo experiments demonstrated excellent biocompatibility and tolerability of the nanoparticles as a distinctive pharmacokinetic pathway associated intranasal delivery different from other systemic routes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the “Cell Cultures, Antibody Production and Cytometry Services” of the Institut de Biotecnologia i de Biomedicina (IBB) associated with the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) for their collaboration in the cell culture and cytometric assays.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by grants PID2021-127983OB-C21 and PID2021-127983OB-C22 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/and ERDF. A way of making Europe. F. N. acknowledges support by grant CNS2022-136106 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by European Union NextGeneration EU/PRTR. The ICN2 is funded by the CERCA program/Generalitat de Catalunya and supported by the Severo Ochoa Centres of Excellence program, grant CEX2021-001214-S, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039.501100011033.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. R.G and P.A.: methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, review and editing. X. Mao: methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis. J. Mancebo: synthesis and data curation, formal analysis, visualization, editing. D. Montpeyo: cell culture. F. Novio: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, Writing – review and editing. Julia Lorenzo: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. D. Ruiz-Molina: Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Zhang C, Xu C, Gao X, Yao Q. Platinum-based drugs for cancer therapy and anti-tumor strategies. Theranostics. 2022;12:2115–32.10.7150/thno.69424Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Zhang J, Li X, Han X, Liu R, Fang J. Targeting the thioredoxin system for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:794–808.10.1016/j.tips.2017.06.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Bian M, Fan R, Zhao S, Liu W. Targeting the thioredoxin system as a strategy for cancer therapy. J Med Chem. 2019;62:7309–21.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01595Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Park GY, Wilson JJ, Song Y, Lippard SJ. Phenanthriplatin, a monofunctional DNA-binding platinum anticancer drug candidate with unusual potency and cellular activity profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11987–92.10.1073/pnas.1207670109Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Florea AM, Büsselberg D. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: Cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects. Cancers. 2011;3(1):1351–71.10.3390/cancers3011351Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Ohmichi M, Hayakawa J, Tasaka K, Kurachi H, Murata Y. Mechanisms of platinum drug resistance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(3):113–6.10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Wang D, Lippard SJ. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(4):307–20.10.1038/nrd1691Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Corte-Rodríguez M, Espina M, Sierra LM, Blanco E, Ames T, Montes-Bayón M, et al. Quantitative evaluation of cellular uptake, DNA incorporation and adduct formation in cisplatin sensitive and resistant cell lines: Comparison of different Pt-containing drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;98:69–77.10.1016/j.bcp.2015.08.112Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Qi L, Luo Q, Zhang Y, Jia F, Zhao Y, Wang F. Advances in toxicological research of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Chem Res Toxicol. 2019;32(8):1469–86.10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00204Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Wong E, Giandornenico CM. Current status of platinum-based antitumor drugs. Chem Rev. 1999;99(9):2451–66.10.1021/cr980420vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Wlodarczyk MT, Dragulska SA, Camacho-Vanegas O, Dottino PR, Jarzęcki AA, Martignetti JA, et al. Platinum(II) complex-nuclear localization sequence peptide hybrid for overcoming platinum resistance in cancer therapy. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4(2):463–7.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00921Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Mjos KD, Orvig C. Metallodrugs in medicinal inorganic chemistry. Chem Rev. 2014;114(8):4540–63.10.1021/cr400460sSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Gibson D. Multi-action Pt(IV) anticancer agents; do we understand how they work? J Inorg Biochem. 2019;191:77–84.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.11.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wang Z, Xu Z, Zhu G. A platinum(IV) anticancer prodrug targeting nucleotide excision repair to overcome cisplatin resistance. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55(50):15564–8.10.1002/anie.201608936Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Chen S, Yao H, Zhou Q, Tse MK, Gunawan YF, Zhu G. Stability, reduction, and cytotoxicity of platinum(IV) anticancer prodrugs bearing carbamate axial ligands: Comparison with their carboxylate analogues. Inorg Chem. 2020;59(16):11676–7.10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01541Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Wong DY, Yeo CH, Ang WH. Immuno-chemotherapeutic platinum(IV) prodrugs of cisplatin as multimodal anticancer agents. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(26):6752–56.10.1002/anie.201402879Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Gibson D. Platinum (IV) anticancer agents; are we en route to the holy grail or to a dead end? J Inorg Biochem. 2021;217:111353–63.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2020.111353Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Dhami NK, Pandey RS, Jain UK, Chandra R, Madan J. Non-aggregated protamine-coated poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles of cisplatin crossed blood-brain barrier, enhanced drug delivery and improved therapeutic index in glioblastoma cells: In vitro studies. J Microencapsul. 2014;31(7):685–93.10.3109/02652048.2014.913725Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Depciuch J, Miszczyk J, Maximenko A, Zielinski PM, Rawojć K, Panek A, et al. Gold nanopeanuts as prospective support for cisplatin in glioblastoma nano-chemo-radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):1–11.10.3390/ijms21239082Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Wu H, Cabral H, Toh K, Mi P, Chen YC, Matsumoto Y, et al. Polymeric micelles loaded with platinum anticancer drugs target preangiogenic micrometastatic niches associated with inflammation. J Controlled Release. 2014;189:1–10.10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Kesavan A, Ilaiyaraja P, Beaula WS, Kumari VV, Lal JS, Arunkumar C, et al. Tumor targeting using polyamidoamine dendrimer-cisplatin nanoparticles functionalized with diglycolamic acid and herceptin. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;96:255–63.10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.08.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Barth RF, Wu G, Meisen WH, Nakkula RJ, Yang W, Huo T, et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of cisplatin-containing EGFR targeting bioconjugates as potential therapeutic agents for brain tumors. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:2769–81.10.2147/OTT.S99242Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Thanasupawat T, Bergen H, Hombach-Klonisch S, Krcek J, Ghavami S, Del Bigio MR, et al. Platinum (IV) coiled coil nanotubes selectively kill human glioblastoma cells. Nanomedicine. 2015;11(4):913–25.10.1016/j.nano.2015.01.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Mathew EN, Berry BC, Yang HW, Carroll RS, Johnson MD. Delivering therapeutics to glioblastoma: Overcoming biological constraints. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1711–24.10.3390/ijms23031711Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Harder BG, Blomquist MR, Wang J, Kim AJ, Woodworth GF, Winkles JA, et al. Developments in blood-brain barrier penetrance and drug repurposing for improved treatment of glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2018;8:462.10.3389/fonc.2018.00462Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Zhang Y, Fu X, Jia J, Wikerholmen T, Xi K, Kong Y, et al. Glioblastoma therapy using codelivery of cisplatin and glutathione peroxidase targeting siRNA from iron oxide nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(39):43408–21.10.1021/acsami.0c12042Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Saraiva C, Praça C, Ferreira R, Santos T, Ferreira L, Bernardino L. Nanoparticle-mediated brain drug delivery: Overcoming blood-brain barrier to treat neurodegenerative diseases. J Controlled Release. 2016;235:34–47.10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.05.044Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Hersh DS, Wadajkar AS, Roberts NB, Perez JG, Connolly NP, Frenkel V, et al. Evolving drug delivery strategies to overcome the blood brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(9):1177–93.10.2174/1381612822666151221150733Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Liang S, Zhou Q, Wang M, Zhu Y, Wu Q, Yang X. Water-soluble l-cysteine-coated FePt nanoparticles as dual MRI/CT imaging contrast agent for glioma. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:2325–33.10.2147/IJN.S75174Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Sun H, Chen X, Chen D, Dong M, Fu X, Li Q, et al. Influences of surface coatings and components of FePt nanoparticles on the suppression of glioma cell proliferation. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:3295–307.10.2147/IJN.S32678Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Alfonso-Triguero P, Lorenzo J, Candiota AP, Arús C, Ruiz-Molina D, Novio F. Platinum-based nanoformulations for glioblastoma treatment: the resurgence of platinum drugs? Nanomaterials 13(10):1619–51.10.3390/nano13101619Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Ruiz-Molina D, Mao X, Alfonso-Triguero P, Lorenzo J, Bruna J, Yuste VJ, et al. Advances in preclinical/clinical glioblastoma treatment: Can nanoparticles be of help? Cancers. 2022;14(19):4960–85.10.3390/cancers14194960Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Bigaj-Józefowska MJ, Coy E, Załęski K, Zalewski T, Grabowska M, Jaskot K, et al. Biomimetic theranostic nanoparticles for effective anticancer therapy and MRI imaging. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2023;249:112813.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2023.112813Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Mrówczyński R, Grześkowiak BF. Biomimetic catechol‐based nanomaterials for combined anticancer therapies. Nanoeng Biomater. 2021;1:145–80.10.1002/9783527832095.ch23Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Liu L, Ye Q, Lu M, Lo YC, Hsu YH, Wei MC, et al. A new approach to reduce toxicities and to improve bioavailabilities of platinum-containing anti-cancer nanodrugs. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):10881–92.10.1038/srep10881Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Liebscher J. Chemistry of polydopamine–scope, variation, and limitation. Eur J Org Chem. 2019;2019(31–32):4976–94.10.1002/ejoc.201900445Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Alfieri ML, Weil T, Ng DY, Ball V. Polydopamine at biological interfaces. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;305:102689.10.1016/j.cis.2022.102689Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Alfieri ML, Panzella L, Napolitano A. Multifunctional coatings hinging on the catechol/amine interplay. Eur J Org Chem. 2023;2023(33).10.1002/ejoc.202301002Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Mao X, Wu S, Calero-Pérez P, Candiota AP, Alfonso P, Bruna J, et al. Synthesis and validation of a bioinspired catechol-functionalized pt(IV) prodrug for preclinical intranasal glioblastoma treatment. Cancers. 2022;14(2):410–25.10.3390/cancers14020410Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Mao X, Calero-Pérez P, Montpeyó D, Bruna J, Yuste VJ, Candiota AP, et al. Intranasal administration of catechol-based pt(IV) coordination polymer nanoparticles for glioblastoma therapy. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(7):1221–43.10.3390/nano12071221Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Labet M, Thielemans W. Synthesis of polycaprolactone: A review. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(12):3484–504.10.1039/b820162pSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Wei Q, Zhang F, Li J, Li B, Zhao C. Oxidant-induced dopamine polymerization for multifunctional coatings. Polym Chem. 2010;1(9):1430–3.10.1039/c0py00215aSuche in Google Scholar

[43] Lee SM, O’Halloran TV, Nguyen ST. Polymer-caged nanobins for synergistic cisplatin-doxorubicin combination chemotherapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(48):17130–8.10.1021/ja107333gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Lushchak VI. Glutathione homeostasis and functions: Potential targets for medical interventions. J Amino Acids. 2012;2012:1–26.10.1155/2012/736837Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Liu Z, Wang M, Wang H, Fang L, Gou S. Platinum-based modification of styrylbenzylsulfones as multifunctional antitumor agents: Targeting the RAS/RAF pathway, enhancing antitumor activity, and overcoming multidrug resistance. J Med Chem. 2019;63(1):186–204.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01223Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Mao X, Si J, Huang Q, Sun X, Zhang Q, Shen Y, et al. Self-assembling doxorubicin prodrug forming nanoparticles and effectively reversing drug resistance In vitro and In vivo. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2016;5(19):2517–27.10.1002/adhm.201600345Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Mahmoudi M, Laurent S, Shokrgozar MA, Hosseinkhani M. Toxicity evaluations of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Cell ‘vision’ versus physicochemical properties of nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):7263–76.10.1021/nn2021088Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Kumar N, Goel N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Rep. 2019;24:e00370.10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00370Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Forooshani PK, Meng H, Lee BP. Catechol redox reaction: Reactive oxygen species generation, regulation, and biomedical applications. ACS Symp Ser. 2017;1:179–96.10.1021/bk-2017-1252.ch010Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Eruslanov E, Kusmartsev S. Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;594:57–72.10.1007/978-1-60761-411-1_4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Kreuter J. Drug delivery to the central nervous system by polymeric nanoparticles: What do we know? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;71:2–14.10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Yonezawa A, Masuda S, Yokoo S, Katsura T, Inui KI. Cisplatin and oxaliplatin, but not carboplatin and nedaplatin, are substrates for human organic cation transporters (SLC22A1-3 and multidrug and toxin extrusion family). J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319(2):879–86.10.1124/jpet.106.110346Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Howell SB, Safaei R, Larson CA, Sailor MJ. Copper transporters and the cellular pharmacology of the platinum-containing cancer drugs. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77(6):887–94.10.1124/mol.109.063172Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Tesniere A, Schlemmer F, Boige V, Kepp O, Martins I, Ghiringhelli F, et al. Immunogenic death of colon cancer cells treated with oxaliplatin. Oncogene. 2010;29(4):482–91.10.1038/onc.2009.356Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Chapman EG, DeRose VJ. Enzymatic processing of platinated RNAs. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(6):1946–52.10.1021/ja908419jSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Bose RN, Maurmann L, Mishur RJ, Yasui L, Gupta S, Grayburn WS, et al. Non-DNA-binding platinum anticancer agents: Cytotoxic activities of platinum-phosphato complexes towards human ovarian cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(47):18314–9.10.1073/pnas.0803094105Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Shader RI. Safety versus tolerability. Clin Ther. 2018;40(5):672–3.10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.04.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Varbanov H, Valiahdi SM, Legin AA, Jakupec MA, Roller A, Bernhard K, et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel bis(carboxylato)dichloridobis(ethylamine)platinum(IV) complexes with higher cytotoxicity than cisplatin. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46(11):5456–64.10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.09.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Tolan D, Gandin V, Morrison L, El-Nahas A, Marzano C, Montagner D, et al. Oxidative stress induced by Pt(IV) pro-drugs based on the cisplatin scaffold and indole carboxylic acids in axial position. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29367.10.1038/srep29367Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Mi Q, Shu S, Yang C, Gao C, Zhang X, Luo X, et al. Current status for oral platinum (IV) anticancer drug development. Int J Med Phys Clin Eng Radiat Oncol. 2018;7(2):231–2.10.4236/ijmpcero.2018.72020Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Wexselblatt E, Gibson D. What do we know about the reduction of Pt(IV) pro-drugs? J Inorg Biochem. 2012;117:220–9.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.06.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Kuang X, Chi D, Li J, Guo C, Yang Y, Zhou S, et al. Disulfide bond-based cascade reduction-responsive Pt(IV) nanoassemblies for improved anti-tumor efficiency and biosafety. Colloids Surf B. 2021;203:111766.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111766Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Matthew DH, Trevor WH. Platinum(IV) antitumour compounds: their bioinorganic chemistry. Coord Chem Rev. 2002;232(1–2):49–67.10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00026-7Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Nagyal L, Kumar A, Sharma R, Yadav R, Chaudhary P, Singh R. Bioinorganic chemistry of platinum(IV) complexes as platforms for anticancer agents. Curr Bioact Compd. 2020;16(7):726–37.10.2174/1573407215666190409105351Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Liu XM, Zhu ZZ, He XR, Zou YH, Chen Q, Wang XY, et al. NIR light and GSH dual-responsive upconversion nanoparticles loaded with multifunctional platinum (IV) prodrug and RGD peptide for precise cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(31):40753–66.10.1021/acsami.4c08899Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Schmidt C, Babu T, Kostrhunova H, Timm A, Basu U, Ott I, et al. Are Pt (IV) prodrugs that release combretastatin A4 true multi-action prodrugs? J Med Chem. 2021;64(15):11364–78.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00706Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Gabano E, Ravera M, Osella D. Pros and cons of bifunctional platinum (IV) antitumor prodrugs: two are (not always) better than one. Dalton Trans. 2014;43(26):9813–20.10.1039/c4dt00911hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications