Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

-

Armin Rajabi

, Yap Boon Kar

, Camellia Doroody

, Tiong Sieh Kiong

Abstract

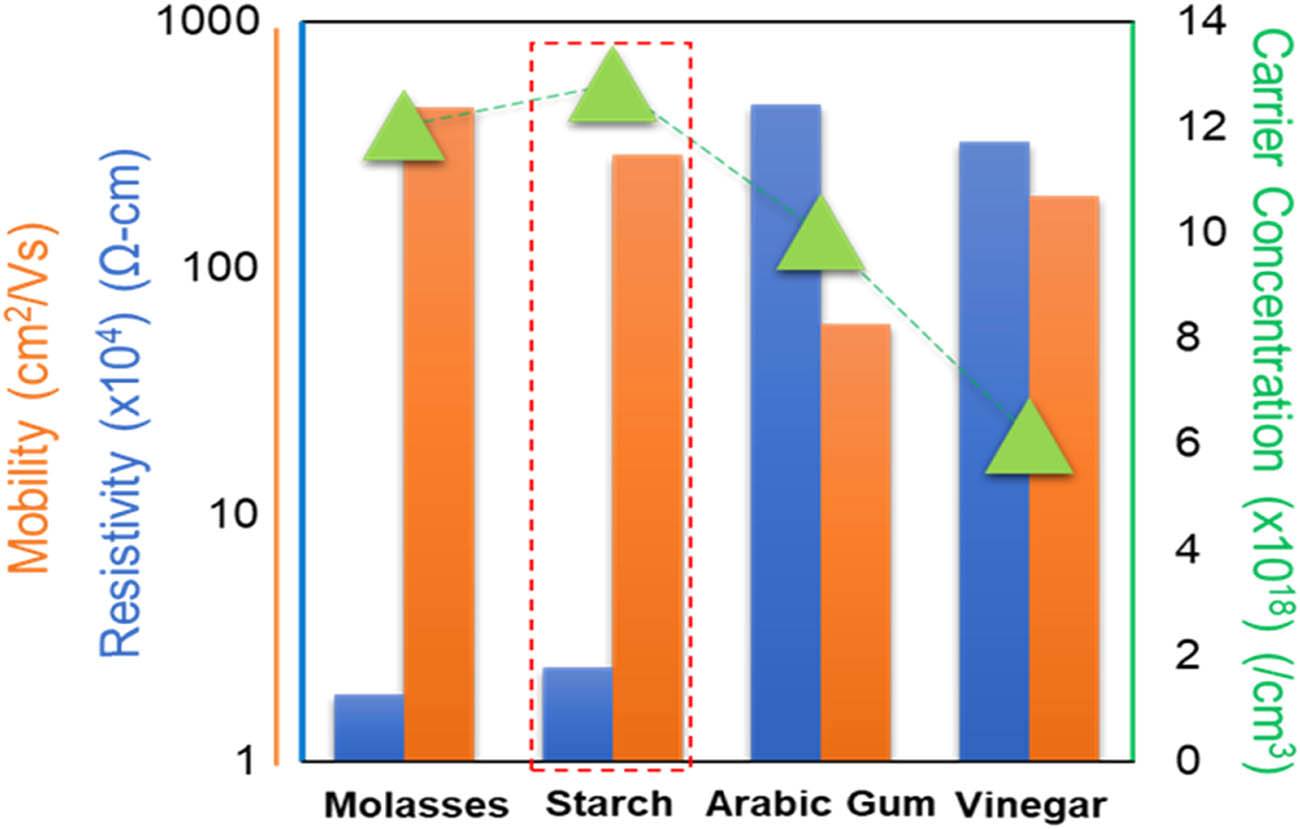

The aim of this study is to explore the potential compatibility of copper oxide nano-powders synthesised via hydrothermal method for solar cell applications by triggering a reaction between copper acetate and various reducing agents derived from natural resources, including Arabic gum, molasses, starch, and vinegar. X-ray diffraction analysis revealed the crystalline phases of the synthesised materials, indicating the successful synthesis of copper oxide material, which was confirmed by identifying patterns that matched specific copper oxide phases. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was employed to analyse the molecular vibrations and chemical compounds present in the reducing agents. The reducing properties of the selected materials and their capacity to convert copper acetate into copper oxide were validated. Field-emission microscopy and transmission electron microscopy analyses of the synthesised copper oxide nanoparticles (NPs) revealed variations in particle size and morphology. These variations were dependent on the particular reducing agent utilised during synthesis. Moreover, the carrier concentration, mobility, and resistivity were evaluated as the electrical properties of the spin-coated copper oxide thin films. Hall effect analysis determined that the choice of reducing agent significantly influenced the carrier concentration (n) and mobility (µ) of the films. Remarkably, nano copper oxide films synthesised using starch exhibited irregular spherical grains with porous surfaces. Starch-synthesised samples showed the highest conductivity of n = 1.2 × 1019 cm−3 when compared with those synthesised with other reducing agents. This suggests that the porous surfaces in the starch-synthesised films may have contributed to their enhanced conductivity compared to films synthesised with alternative reducing agents. In summary, the findings emphasised the influence of the reducing agent on the size, morphology, and electrical conductivity of the copper oxide NPs.

1 Introduction

In recent years, research on green chemistry and its potential to eliminate or reduce hazardous materials in sustainable energy generation and chemical processes has grown significantly. Biopolymer-based reduction agents have emerged as a promising alternative in synthesis reactions because of their environmental friendliness. The development of nanomaterials via green procedures has attracted attention, particularly in the search for nanomaterials that possess excellent stability, selectivity, and reactivity [1,2]. Copper oxide nanoparticles (NPs) possess remarkable ability to be finely tuned in their growth, resulting in diverse structures and properties that provide intriguing possibilities. These NPs have been applied in numerous fields, including magnetic storage, gas sensors, DNA biosensors, lithium-ion batteries, catalysis, cancer treatment, antimicrobial agents, hydrogen generation, optics, and electrocatalysis [3,4]. Notably, copper oxides have emerged as a highly promising material in the field of photovoltaics, serving as an active layer in various types of solar cells and as a passive layer in solar-selective surfaces. This research predates the widespread adoption of silicon solar cells. The abundance of copper further adds to its appeal in solar applications. This unique characteristic makes copper oxide an ideal candidate for integration into solar cells, where it can play a crucial role in energy generation. Copper oxide is available across the stable forms of CuO and Cu2O, both having a direct p-type band gap of 1.7–2.2 eV, with optimal absorption coefficient of 105 cm−1 where it can play a crucial role in energy generation and decarbonisation [5]. For instance, copper oxide can be employed as a conductive ink, facilitating the development of printed electronics [6,7]. With their exceptional conductivity, these inks enable intricate circuitry on various substrates, revolutionising the manufacturing process of electronic devices. Nano copper oxides are also instrumental in the field of touch screen and display technology. By leveraging their electrical semiconductor behaviour, they can be utilised in the fabrication of transparent conductive films. These films act as transparent electrodes that allow the precise detection of touch and enable the creation of interactive displays. The integration of nano copper oxides into touch screens and displays paves the way for advanced and user-friendly interfaces, enhancing the overall consumer experience [8,9]. The implementation of nano copper oxides in solar cell technology and electrical semiconductor behaviour presents exciting possibilities that can revolutionise the solar–thermal field [10]. For instance, the cupric oxide (CuO) thin film is reported to be more attractive as a selective absorber than copper oxide in solar thermal energy collectors because of the former’s strong solar absorptance and low thermal emittance [11]. By harnessing the unique properties of nano copper oxides, researchers and engineers can explore highly efficient and sustainable technologies. High-performance nano copper oxide-based solar cells can significantly enhance the efficiency of solar energy conversion, leading to the increased adoption of renewable energy sources and minimising the emission of carbon gases [12,13]. Furthermore, the utilisation of copper oxides in electrical and electronic applications contributes to the development of energy-efficient devices. Their high electrical semiconductor behaviour allows for efficient energy transfer, reduced power consumption, and extended lifespan of electronic devices. This move towards efficient and sustainable technologies aligns with the global efforts to combat environmental challenges and create a greener future [14,15].

The size and shape of NPs are pivotal in determining their surface arrangement and exposed facets. Therefore, various methods have been employed to synthesise copper oxide NPs with specific size and shape profiles. Different methods have been used to synthesise copper oxide NPs, including electrochemical, sonochemical, laser ablation, ball milling, solution phase synthesis, microwave, and hydrothermal syntheses [16–19].

Amongst these methods, hydrothermal synthesis has drawn increased attention because of its numerous advantages. First, it allows for precise control over particle size, enabling the production of NPs with tailored properties that are optimised for specific applications. This level of control is crucial for optimal performance [20,21]. Second, hydrothermal synthesis promotes high purity by minimising impurities during the closed, pressurised reaction [22]. By constantly controlling the reaction conditions, including temperature, pressure, and reaction time, researchers can minimise impurities and ensure high-purity nanomaterials. Third, hydrothermal synthesis promotes homogeneity, ensuring uniform composition and properties of the synthesised nanomaterials. This feature is particularly important for applications that require uniformity to achieve optimal performance [23,24]. Hydrothermal synthesis offers versatility in terms of the structures and shapes of the synthesised nanomaterials. By carefully adjusting the reaction conditions, researchers can synthesise a diverse range of nanomaterials with different structures and shapes, thereby expanding their applicability in various fields. Another advantage of hydrothermal synthesis is its energy efficiency and scalability, making it suitable for industrial applications where large quantities of NPs are required. The energy-efficient nature of the process and its potential for mass production make it an attractive option for commercial production [25,26]. In the context of sustainability and environmental impact, the aim of the present study is to explore a facile and efficient synthesis of copper oxide NPs by using natural resources of reduction agents via the hydrothermal method. By utilising natural resources as reduction agents, this method offers a sustainable and environmentally friendly approach to NP synthesis. This approach is also economically viable and additive-free, enhancing its appeal as an alternative method. It provides a simple, green, and economical approach to synthesise copper oxide NPs while minimising the use of hazardous materials in solar cell devices and reducing the overall environmental impact [27].

2 Experimental procedure

The synthesis of nano copper oxide involved a hydrothermal procedure with the use of various reduction agents, including Arabic gum, molasses, starch, and vinegar. Initially, 0.1 mol% of copper acetate monohydrate (Cu(CH3COO)2·H2O) was dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of distilled water and ethanol, resulting in a 40 CC solution with a distinct blue colour. Subsequent to the initial preparation, solutions were methodically crafted by incorporating 0.1 mol of reducing agents into 100 mL of distilled water each individually. These solutions were then merged with the original mixture to aid in the synthesis. During this stage, the mixture was continuously agitated at 200 rpm and sustained at 90°C, facilitating the copper ions reduction and initiating synthesis. The subsequent step involved transferring the solution into Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclaves, which were then sealed and maintained at a temperature of 160°C for 12 h. This facilitated the formation of a black-coloured precipitate. The obtained precipitate was thoroughly cleansed alternately with distilled water and ethanol to eliminate impurities. Subsequently, it was dried at 80°C in a hot-air oven for 3 h in order to complete the synthesis process (Figure 1). The powders were analysed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) via a diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Germany) under monochromatic Cu–Kα radiation (λ = 0.1541 nm) at 40 kV and 4 mA to determine their compositional properties. Morphological features were evaluated by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; Zeiss Merlin) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Phillips CM-12). The specific surface area of the particles was measured by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis aided by N2 absorption. A Perkin–Elmer Spectrum 400 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR/FTNIR) spectroscope (Akron, OH, USA) was utilised to investigate the chemical composition of the samples in the 500–4,000 cm−1 region. In the electrical tests, a 0.05 M suspension of the powders was prepared by dispersing 7.2 mg synthesised powder in 1 mL of absolute ethanol (99.9%). This suspension was stirred for 30 min at room temperature to ensure a homogenous dispersion. Soda lime glass substrates, precisely cut to 1.5 × 1.5 cm, underwent ultrasonic cleaning in acetone and methanol for 10 min each. These substrates were then rinsed with deionised water and nitrogen-dried. The film was deposited using a dynamic method, where the spin-coating process was conducted at a rotation speed of 1,000 rpm. The samples were annealed at 100°C for 10 min on a hot plate. The thickness of the resultant film was determined using a Veeco DektakXT surface profilometer. The electrical properties, such as carrier concentration, mobility, and resistivity, were evaluated using an HMS ECOPIA 5500 Hall Effect system. The applied magnetic field was 0.57 T, and the probe current varied from 30 nA to 1 mA for all samples. Calibration was conducted by testing a reference oxide sample under standard conditions.

Schematic diagram of copper oxide preparation.

3 Results and discussion

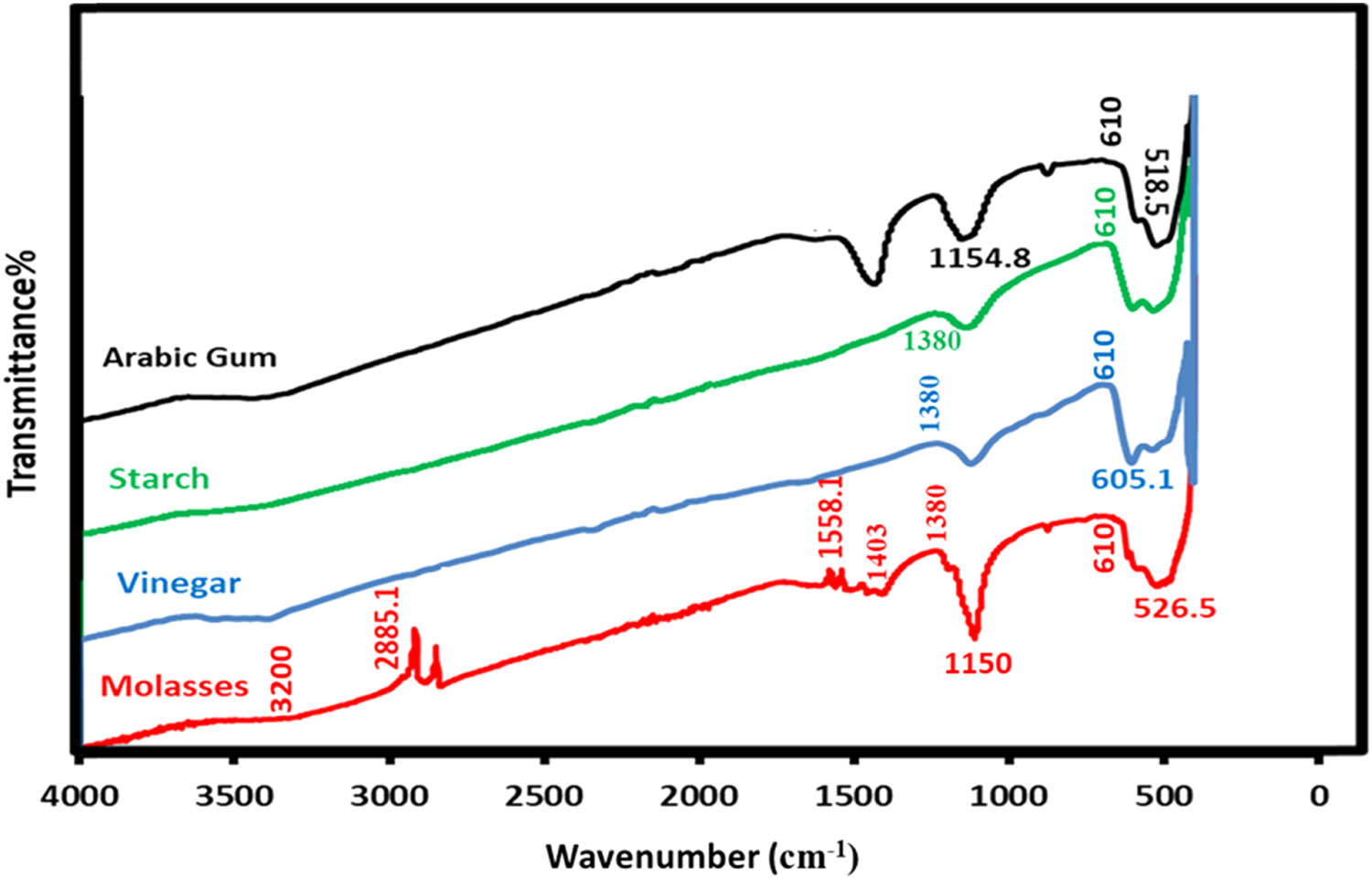

FTIR is an analytical technique used for studying molecular vibrations and identifying chemical compounds based on their characteristic absorption bands. This study synthesised nano powders of copper oxide by using different reducing agents derived from natural resources via the thermal method. The results obtained in this study are shown in Figure 2. Molasses, a by-product of sugar refining, typically shows C–H asymmetric stretching vibrations, primarily in alkyl groups (CH2 and CH), in the range of 2836.1–2885.1 cm−1 [28]. The band at 1,109 cm−1 is often associated with C–O stretching vibrations, suggesting the presence of C–O bonds in the molecular structure of this by-product. The precise interpretation of this band may vary depending on the specific composition and structure of the by-product being analysed. Furthermore, the band at 1,558 cm−1 is often linked to C═C stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of carbon–carbon double bonds (C═C) in the molecular structure of the sugar refining by-product [29]. Additionally, bands observed around 1,050–1,150 cm−1 correspond to C–O stretching vibrations originating from carbohydrates prevalent in molasses. Arabic gum, known for its polymeric nature and inherent reducing capabilities, exhibits distinct absorption bands. A band near 1,500 cm−1 corresponds to the presence of carboxylate groups (–COO–) or carboxylic acids (–COOH). This region is associated with asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate groups. Across all reducing agents, spectral bands within the range of absorption bands at 610 and 1,380 cm−1 were attributed to the Cu–O stretching vibrations and Cu–O–Cu bending vibrations, respectively.

FTIR spectra of the samples at different reduction agent.

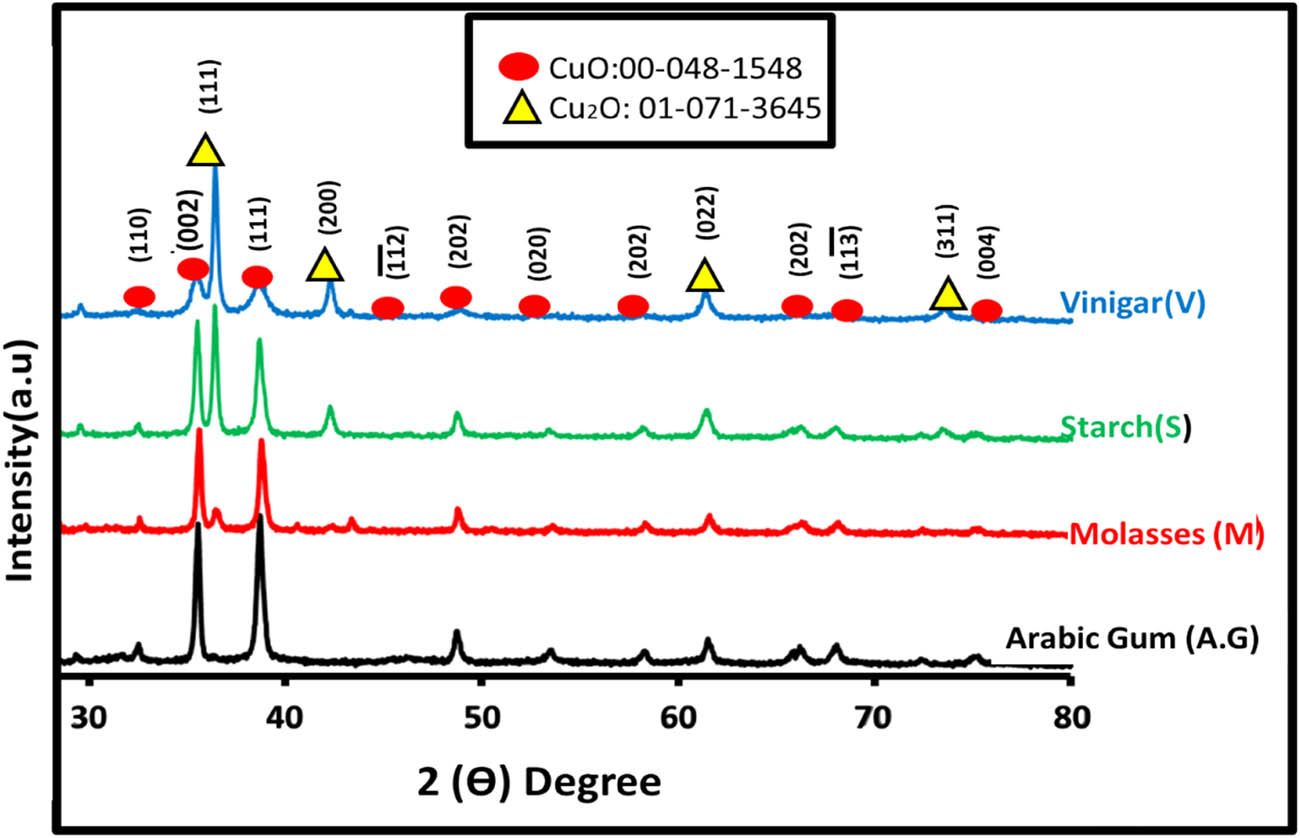

Phase identification of materials synthesised using four reducing agents was performed through XRD analysis, as shown in Figure 3. The discernible peaks in the XRD pattern precisely matched the established diffraction patterns of various copper oxide phases, providing strong validation for the successful synthesis of the desired copper oxide materials. The sharp and well-defined peaks in the XRD spectrum confirmed the crystalline nature of the synthesised copper oxides. Peaks were observed at 36.4, 42.3, 33.4, 35.5, and 38.7°C, corresponding to reflections from the Cu2O (111), Cu2O (200), CuO (110), CuO (002), and CuO (111) planes, respectively. These observations confirmed the polycrystalline nature of all samples, which was aligned with the characteristic peaks of monoclinic CuO (JCPDS 048-1548) and cubic Cu2O (JCPDS 71-3645) structures. The experimental results were consistent with previously reported diffraction patterns of CuO and Cu2O NPs prepared using various methodologies [30,31]. Thus, XRD analysis is reliable and consistent in determining the crystalline phases of the synthesised copper oxide materials. The absence of diffraction peaks corresponding to impurity phases or unreacted precursors emphasised the high degree of conversion achieved during hydrothermal synthesis. This result demonstrated the efficacy of the hydrothermal conditions in promoting copper oxide phase formation while minimising undesired by-products. Notably, the Cu2O (111) peak was absent in the material synthesised by Arabic gum. This result could be attributed to the small quantity of the material, resulting in low crystallinity and weak diffraction signals. A similar reduction in XRD intensity, caused by a low quantity of the phase, was observed in previous studies, providing further support for this explanation [32,33]. Furthermore, carboxylate groups and carboxylic acids, as indicated by FTIR results, can indeed influence the phase formation in synthesised materials. The absence of the Cu2O (111) peak may indeed indicate the predominant presence of CuO in the synthesised material, potentially due to phase transformations or preferential synthesis conditions favouring CuO formation over Cu2O. These compounds can impact the crystal structure and the preferential formation of one copper oxide phase over the other. Additionally, incorporation of carboxylate groups and carboxylic acids can significantly impact the crystallinity of synthesised copper oxide NPs through their interactions with the nucleation and growth processes during synthesis. These functional groups can act as both capping agents and ligands on the NP surface, influencing the formation of nucleation sites. In fact, carboxylate groups and carboxylic acids can provide stabilisation to the NPs, which may affect the arrangement and packing of the crystal lattice during NP formation. These interactions may lead to a more ordered and crystalline structure in the resulting NPs, resulting in sharper and more intense XRD peaks.

XRD patterns of synthesised copper oxide with different reduction agent.

In order to determine the average crystallite size of the particles, the Scherrer formula can be used:

where d represents the average crystallite size of the powder, λ denotes the wavelength of Cu K radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å), β represents the full width at half maximum (FWHM) intensity, θ signifies Bragg’s diffraction angle, and k is a constant typically around 0.9. Furthermore, the microstrain (ε) is derived using equation (2) [34].

The structural parameters of the nano copper oxides synthesised using different reduction agents are presented in Table 1. It can be inferred from Table 1 that the crystal size of nano copper oxides synthesized using vinegar as the reduction agent is the largest when compared to the other reduction agents, a trend that aligns with the findings from TEM analysis. The discrepancy between the results obtained from XRD and TEM can be ascribed to the inherent differences in what each method measures. While TEM provides direct observations of individual particle dimensions, the crystallite size obtained from XRD reflects an average size within the bulk material. This variation is influenced by factors such as crystal facets, stacking faults, and dislocations, which can lead to differences in the size determination between these two techniques [35,36].

Calculated structural parameters

| Parameters | Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinegar (Cu2O) | Starch (Cu2O) | Molasses (CuO) | Arabic gum (CuO) | |

| Miller indices (hkl) | (111) | (111) | (002) | (002) |

| The angle of incidence (θ) | 17.82 | 18.33 | 19.32 | 19.40 |

| FWHM (β) (deg) | 35.517 | 36.469 | 38.684 | 38.700 |

| Crystallite size D (nm) | 53 | 34 | 20 | 32 |

| Lattice a (Å) | 4.016 | 4.033 | 4.899 | 5.034 |

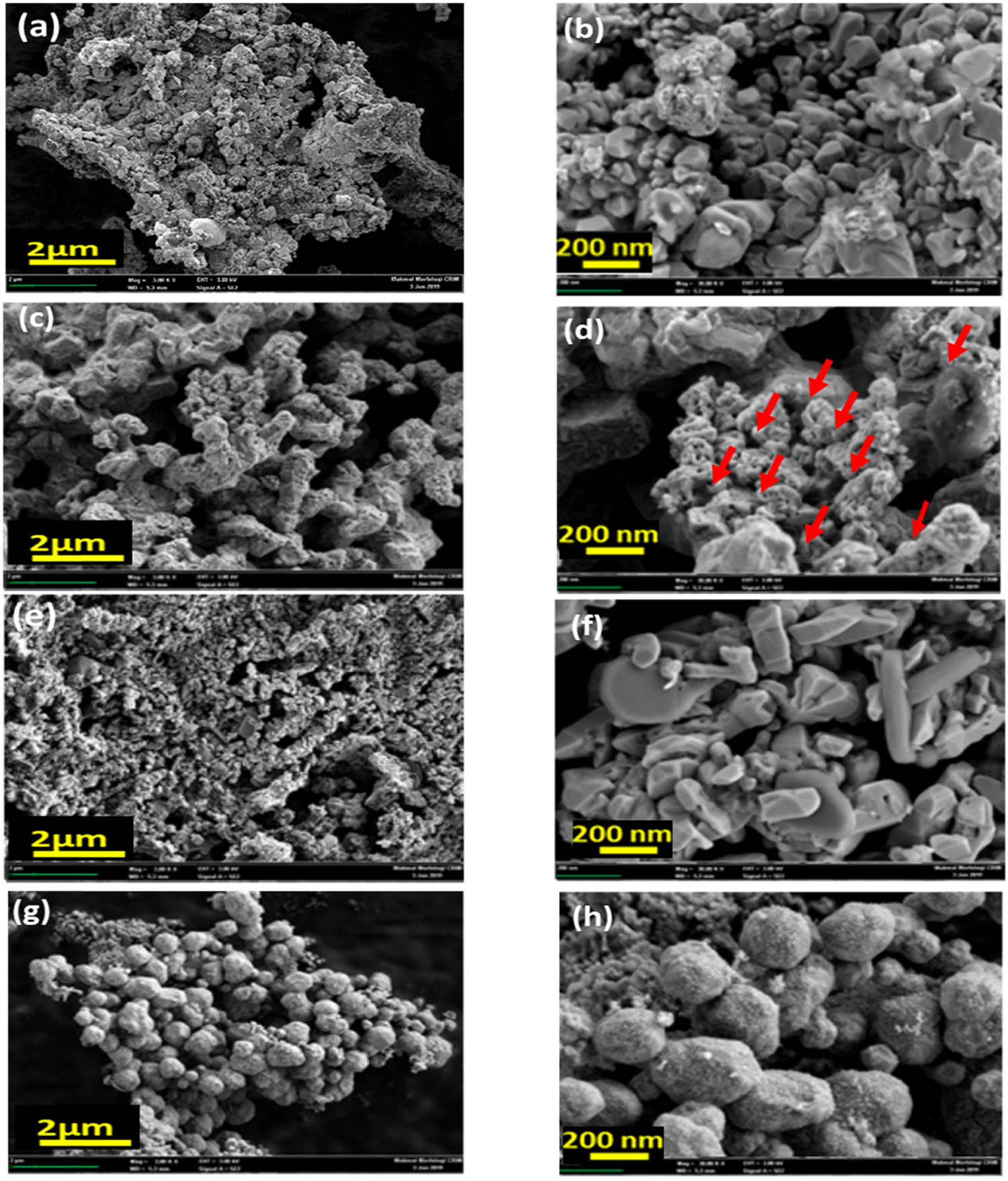

The size and morphology of nano copper oxide are shown in Figure 4. The microstructures of the materials at two magnifications were approximately similar, and agglomeration particles could be observed with almost uniform particle size distribution. In general, the growth mechanism of nano copper using a reduction agent with the hydrothermal method involves the reduction of copper ions, nucleation of small clusters, and their subsequent growth into nano-sized particles. The choice of reduction agent and control of reaction conditions are key factors in tailoring the properties of these NPs for various applications, and the formation of different particle sizes is described in the literature [37–40]. The results showed considerable differences in morphology amongst these powders synthesised by different reduction materials. For instance, the FE-SEM image in Figure 4a and b of the nano CuO synthesised by molasses showed sand-like morphology, which was composed of a series of irregular spherical shapes in the range of 50–200 nm due to powder agglomeration. By contrast, starch showed slightly different forms of morphology in Figure 4c and d. Pores (red arrows) on the surface of the particles helped distinguish them from one another. Starch operates as a stabilizing agent by binding to the surfaces of developing copper oxide NPs. Starch forms a protective biopolymeric layer that envelops the nascent NPs, affecting the particle’s shape, and serves as a shape-controlling and capping agent throughout the growth stages. The same behaviour was also observed in the synthesis of silver NPs [41]. The synthesised samples by Arabic gum in Figure 4f displayed nanorod-like morphology with some agglomeration; the nanorods had a length of 300–400 nm and width of 100 nm, whereas the particles ranged from 60 to 200 nm. The last microstructure presented sphere-like particle morphology. The material had some small quasi-spheres that were randomly stuck to the large particles. Vinegar prevents the NPs from agglomerating or forming irregular shapes by providing a stable environment in the reaction mixture. Considering all the cited cases, it is noted that the morphology of nano copper oxide synthesised using different reduction agents can be attributed to the complex interactions between the reduction agents and copper ions during the synthesis process. Each reduction agent exhibits distinct chemical components and functional groups that influence the reduction kinetics, nucleation, and crystal growth of the copper oxide NPs, resulting in variations in morphology. Arabic gum, with its complex carboxylate groups and carboxylic acids, acts as an effective stabilizer and capping agent, leading to the formation of unique nano copper oxide morphologies. Molasses, a viscous syrup containing sugars and organic compounds, may impart different kinetic and thermodynamic effects on the NP synthesis process, resulting in distinct morphologies. Starch, a polymer consisting of glucose units, and vinegar, containing acetic acid, both exhibit chemical properties that can influence the reduction and growth of copper oxide NPs in ways that lead to varied morphologies. The specific chemical composition and reactivity of each natural reduction agent can lead to different nucleation and growth patterns, ultimately affecting the final morphology of the synthesised nano copper oxide. This highlights the importance of carefully selecting and optimizing the reduction agent for the specific synthesis conditions to achieve the desired NP morphology.

FE-SEM images of the samples with different reduction agent at different magnifications: (a) and (b) molasses, (c) and (d) starch, (e) and (f) Arabic gum, and (g) and (h) vinegar.

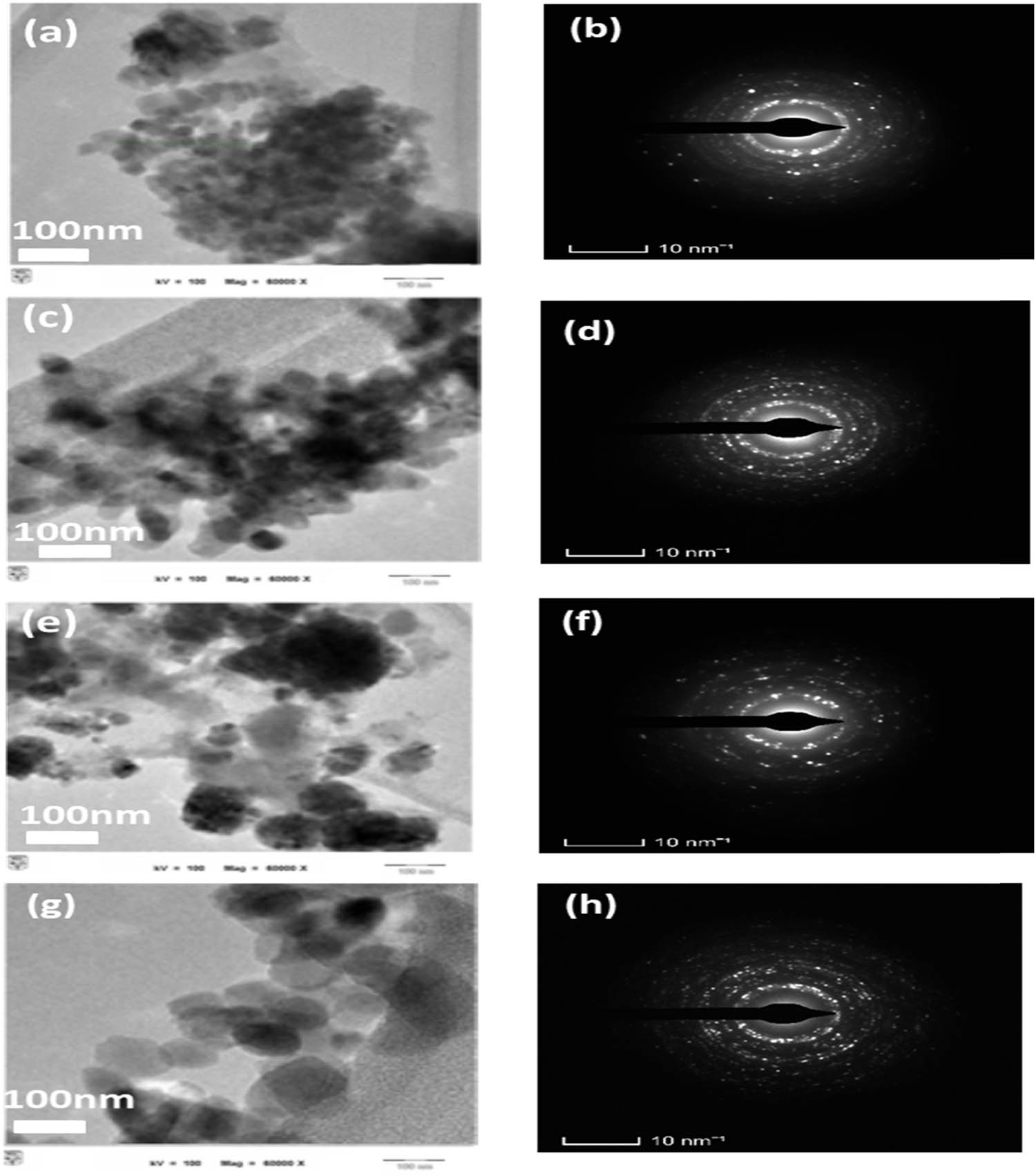

TEM tests were performed to characterise the detailed features of nano copper in this study. As shown in Figure 5, the TEM images revealed that the average particle sizes ranged from 50 to 200 nm for the powders synthesised with molasses, starch, and Arabic gum. Thus, these three methods produced copper NPs that were less than 200 nm. Interestingly, the TEM image of the particles synthesised with vinegar showed a slightly larger particle size of around 300 nm. This difference in particle size could be attributed to the interaction between the copper precursor and vinegar. Notably, the TEM results corroborated the Fe-SEM results, thereby reinforcing the consistency and reliability of the particle size measurements. Furthermore, TEM ring (Figure 5b, d, f, and h) diffraction tests yielded excellent insights into the crystal structure of materials, even those exhibiting a polished surface. CuO (copper(ii) oxide) and Cu2O (copper(i) oxide) are two different compounds with distinct crystal structures. In TEM ring diffraction tests, these compounds exhibited different diffraction patterns because of their unique crystal lattices. CuO has a monoclinic crystal structure; its crystal lattice is not perfectly symmetric, resulting in the presence of multiple diffraction spots in the pattern. These diffraction spots appear as rings or arcs in the patterns (Figure 5f). The arrangement and intensity of these markings provide information about the spatial arrangement of atoms within the CuO crystal lattice. Meanwhile, Cu2O has a cubic crystal structure, which exhibits higher symmetry compared with the monoclinic structure of CuO. The diffraction pattern of Cu2O typically exhibits sharp and distinct spots, forming a clear pattern of spots rather than rings or arcs (Figure 5d and h). Notably, when particles are uniformly distributed, they are likely to exhibit a regular arrangement and alignment within the sample, leading to a symmetrical and well-defined diffraction pattern. By contrast, an uneven or non-uniform distribution of particles can introduce defects, clustering or random orientations within the sample. These irregularities can disrupt the ordered arrangement of particles and produce a diffraction pattern with distorted or diffuse rings instead of sharp and well-defined rings.

TEM images (a), (c), (e), and (g) and ring electron diffraction patterns (b), (d), (f), and (h) of the synthesised powders by different reduction agent: (a) and (b) molasses, (c) and (d) starch, (e) and (f) Arabic gum, and (g) and (h) vinegar.

The core factors of electrical analysis are semiconductor type, conductivity, mobility, and carrier concentration of nano copper oxide films calculated at 25℃ (Figure 6). The equations connecting the carrier concentration, mobility, and resistivity were (n = qημe) and (n = 1/ρ) following Ohm’s law, where n is the conductivity, ρ is the resistivity, q is the electron charge, η is the electron density, and µ is the Hall mobility [42]. Here all the coated films were derived to be p-type, with the carrier concentration equal to the number of holes at equilibrium temperature. The velocity of electrons inside a semiconducting material when an electric field was applied was referred to as mobility. Impurity levels, defects, and carrier concentrations directly alter the carrier mobility in a semiconductor [43], which were observed to decline when Arabic gum and molasses were used as reduction agents. The results of FTIR demonstrated that CH2, CH, and C–O stretching vibrations and carboxylate groups (–COO–) or carboxylic acids (–COOH) were for molasses and Arabic gum, respectively. Furthermore, the agglomeration of large particles could have a significant impact on the electrical properties of materials. One consequence of particle agglomeration was a decrease in mobility and carrier concentration, leading to an increase in resistivity. When particles agglomerated, as in Figure 4e and g, their surface area decreased, reducing the number of available active sites for charge carriers. This reduction in surface area limited the movement of charge carriers, thereby hindering their mobility and increasing the resistivity of the material [40]. Agglomeration can lead to the formation of insulating barriers between particles. These barriers impede the flow of charge carriers and contribute to the increase in resistivity, as observed in the synthesised samples by vinegar. Hall effect analysis demonstrated that starch case was more conductive compared with the other grown films. Consistent with the literature [44], the results confirmed that the surface uniformity and high specific surface (Table 2) resulted in low electrical resistivity (Figure 6). Notably, the increased specific surface area in nano copper could enhance the surface-to-volume ratio. This ratio could influence the carrier concentration by allowing additional charge carriers to reside at the surface of the material. With a large surface area, many charge carriers could be accommodated, which led to an increase in carrier concentration (Figure 4c and d). Furthermore, copper oxide synthesized with molasses demonstrates markedly elevated mobility and slightly lower carrier concentration and resistivity in comparison to starch samples. Reduced carrier concentration can be attributed to the reduced porosity in agglomerated sites and diminished surface area, thereby limiting the availability of active sites, and increased recombination velocity [45,46]. Hence, CuO2 thin films synthesised via starch were concluded to be the most suitable choice as a back surface field (BSF) layer in thin film solar cells with respect to the electrical properties. Improving the electrical properties could enhance the energy conversion efficiency of the solar cell, allowing it to generate more electricity from sunlight. However, Hall measurement alone is not a widespread calculation to resemble the copper oxide thin film potential as BSF in solar cells. Further characterisation is necessary in the future to verify the results.

Electrical properties of the samples at different reduction agents.

BET results with different reduction agent

| Molasses | Starch | Arabic gum | Vinegar |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24.98 m²/g | 42.37 m²/g | 19.915 m²/g | 11.49 m²/g |

4 Conclusion

This study was performed to evaluate the properties of hydrothermally synthesised copper oxide for solar cell applications activated by various natural reducing agents consisting of Arabic gum, molasses, starch, and vinegar. The size and morphology of the synthesised copper oxide NPs were found to significantly affect the electrical properties. FE-SEM results demonstrated that starch functioned as a stabilising agent by binding to the surfaces of developing copper oxide NPs in samples. TEM confirmed the mono crystallinity of Arabic gum samples with asymmetric monoclinic CuO crystals, which differed from the multi-crystalline structure of the other samples with a combination of monoclinic and symmetric cubic crystalline Cu2O structures. Impurities such as CH2 and CH, C–O stretching vibrations, and carboxylate groups (–COO–) or carboxylic acids (–COOH) were measured by FTIR, and their presence was found to increase the resistivity of the copper oxide particles. The findings showed that the nano powders of copper oxide with fine size, porosity, and increased specific surface area in the sample were optimal candidates for photovoltaic applications, which involve semiconductors with high carrier concentration. However, impurities also affected the mobility of the copper oxide particles. Further research is needed to explore the potential of copper oxide NPs synthesised by using natural reducing agents for solar cell applications and to optimise their performance by controlling the particle size, morphology, and impurities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia for their support through the HICoE grant no. 2022003HICOE, as well as Dato’ Low Tuck Kwong International Energy Transition Grant under the project code of 202203001ETG. They would also like to express their gratitude to UNITEN for their support through BOLD Refresh Publication Fund with the project code of J510050002-IC-6 BOLDREFRESH2025 - CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE.

-

Funding information: This research is financially supported by Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia for their support through the HICoE grant no. 2022003HICOE, as well as Dato’ Low Tuck Kwong International Energy Transition Grant under the project code of 202203001ETG. They would also like to express their gratitude to UNITEN for their support through BOLD Refresh Publication Fund with the project code of J510050002-IC-6 BOLDREFRESH2025 - CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Rahman ST, Rhee KY, Park S-J. Nanostructured multifunctional electrocatalysts for efficient energy conversion systems: Recent perspectives. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):137–57.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0008Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Alizadeh N, Salimi A. Multienzymes activity of metals and metal oxide nanomaterials: applications from biotechnology to medicine and environmental engineering. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):1–31.10.1186/s12951-021-00771-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Huang A, He Y, Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Yang Y, Zhang J, et al. A review of recent applications of porous metals and metal oxide in energy storage, sensing and catalysis. J Mater Sci. 2019;54:949–73.10.1007/s10853-018-2961-5Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Patra S, Roy E, Tiwari A, Madhuri R, Sharma PK. 2-Dimensional graphene as a route for emergence of additional dimension nanomaterials. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;89:8–27.10.1016/j.bios.2016.02.067Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Kumar S, Bhawna, Gupta A, Kumar R, Bharti A, Kumar A, et al. New insights into Cu/Cu2O/CuO nanocomposite heterojunction facilitating photocatalytic generation of green fuel and detoxification of organic pollutants. J Phys Chem C. 2023;127(15):7095–106.10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c08094Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Krcmar P, Kuritka I, Maslik J, Urbanek P, Bazant P, Machovsky M, et al. Fully inkjet-printed CuO sensor on flexible polymer substrate for alcohol vapours and humidity sensing at room temperature. Sensors. 2019;19(14):3068.10.3390/s19143068Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Rahman MK, Lee JS, Kwon K-S. Realization of thick copper conductive patterns using highly viscous copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticle ink and green laser sintering. J Manuf Process. 2023;105:38–45.10.1016/j.jmapro.2023.09.006Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Wilson NH, Ragothaman M, Palanisamy T. Bimetallic copper–iron oxide nanoparticle-coated leathers for lighting applications. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2021;4(4):4055–69.10.1021/acsanm.1c00388Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Han S, Chae Y, Kim JY, Jo Y, Lee SS, Kim S-H, et al. High-performance solution-processable flexible and transparent conducting electrodes with embedded Cu mesh. J Mater Chem C. 2018;6(16):4389–95.10.1039/C8TC00307FSuche in Google Scholar

[10] Welegergs G, Mehabaw Z, Gebretinsae H, Tsegay M, Kotsedi L, Khumalo Z, et al. Electrodeposition of nanostructured copper oxide (CuO) coatings as spectrally solar selective absorber: Structural, optical and electrical properties. Infrared Phys Technol. 2023;133:104820.10.1016/j.infrared.2023.104820Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Besisa DH, Ewais EM, Mohamed HH, Besisa N, Mohamed EA. Thermal stress durability and optical characteristics of a promising solar air receiver based black alumina ceramics. Ceram Int. 2023;49(12):20429–36.10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.03.171Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Masudy-Panah S, Zhuk S, Tan HR, Gong X, Dalapati GK. Palladium nanostructure incorporated cupric oxide thin film with strong optical absorption, compatible charge collection and low recombination loss for low cost solar cell applications. Nano Energy. 2018;46:158–67.10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.01.050Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Salim E, Bobbara S, Oraby A, Nunzi J. Copper oxide nanoparticle doped bulk-heterojunction photovoltaic devices. Synth Met. 2019;252:21–8.10.1016/j.synthmet.2019.04.006Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Shah MZU, Sajjad M, Hou H, Rahman S, Mahmood A, Aziz U, et al. A new CuO/TiO2 nanocomposite: an emerging and high energy efficient electrode material for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors. J Energy Storage. 2022;55:105492.10.1016/j.est.2022.105492Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Alcalà J, Roig M, Martín S, Barrera A, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Pomar A, et al. Potential of copper oxide high-temperature superconductors for tailoring ferromagnetic spin textures. Surf Interfaces Met Oxide Thin Films, Multilayers, Nanopart Nano-Compos: In Memory of Prof Dr Hanns-Ulrich Habermeier. 2021;167–82. 10.1007/978-3-030-74073-3_7.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Hekmat WA, Numan N, Alsultany FH, Hashim U. Laser energies effects on physical properties of CuO2 nano-structures. Defect and Diffusion Forum. SWITZ: Trans Tech Publ; 2022. p. 119–27.10.4028/p-4wve98Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Jabbar SM. Synthesis of CuO nano structure via sol-gel and precipitation chemical methods. Al-Khwarizmi Eng J. 2016;12(4):126–31.10.22153/kej.2016.07.001Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Karuppaiyan J, Mullaimalar A, Jeyalakshmi R. Adsorption of dyestuff by nano copper oxide coated alkali metakaoline geopolymer in monolith and powder forms: Kinetics, isotherms and microstructural analysis. Environ Res. 2023;218:115002.10.1016/j.envres.2022.115002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Nourine M, Boulkadid MK, Touidjine S, Akbi H, Belkhiri S. Exploring the potential of nitrocellulose for improving the catalytic efficiency of nano copper oxide in the thermal degradation of ammonium perchlorate. React Kinet, Mech Catal. 2023;136:1–15.10.1007/s11144-023-02469-xSuche in Google Scholar

[20] Gong Y, Xie L, Chen C, Liu J, Antonietti M, Wang Y. Bottom-up hydrothermal carbonization for the precise engineering of carbon materials. Prog Mater Sci. 2022;10:1048.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.101048Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Kuśnieruk S, Wojnarowicz J, Chodara A, Chudoba T, Gierlotka S, Lojkowski W. Influence of hydrothermal synthesis parameters on the properties of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2016;7(1):1586–601.10.3762/bjnano.7.153Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Wang J-Q, Huang Y-X, Pan Y, Mi J-X. New hydrothermal route for the synthesis of high purity nanoparticles of zeolite Y from kaolin and quartz. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016;232:77–85.10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.06.010Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Tsoncheva T, Ivanova R, Henych J, Dimitrov M, Kormunda M, Kovacheva D, et al. Effect of preparation procedure on the formation of nanostructured ceria–zirconia mixed oxide catalysts for ethyl acetate oxidation: homogeneous precipitation with urea vs template-assisted hydrothermal synthesis. Appl Catal A: Gen. 2015;502:418–32.10.1016/j.apcata.2015.05.034Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Wang Y, Li N, Chen M, Liang D, Li C, Liu Q, et al. Glycerol steam reforming over hydrothermal synthetic Ni-Ca/attapulgite for green hydrogen generation. Chin J Chem Eng. 2022;48:176–90.10.1016/j.cjche.2021.11.004Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Wang L, Chang Y, Li A. Hydrothermal carbonization for energy-efficient processing of sewage sludge: A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2019;108:423–40.10.1016/j.rser.2019.04.011Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Lin R, Deng C, Ding L, Bose A, Murphy JD. Improving gaseous biofuel production from seaweed Saccharina latissima: The effect of hydrothermal pretreatment on energy efficiency. Energy Convers Manag. 2019;196:1385–94.10.1016/j.enconman.2019.06.044Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Ndlwana L, Raleie N, Dimpe KM, Ogutu HF, Oseghe EO, Motsa MM, et al. Sustainable hydrothermal and solvothermal synthesis of advanced carbon materials in multidimensional applications: A review. Materials. 2021;14(17):5094.10.3390/ma14175094Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Zhang S, Wang J, Jiang H. Microbial production of value-added bioproducts and enzymes from molasses, a by-product of sugar industry. Food Chem. 2021;346:128860.10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128860Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Li B, Fang J, Xu D, Zhao H, Zhu H, Zhang F, et al. Atomically Dispersed Co Clusters Anchored on N‐doped Carbon Nanotubes for Efficient Dehydrogenation of Alcohols and Subsequent Conversion to Carboxylic Acids. ChemSusChem. 2021;14(20):4536–45.10.1002/cssc.202101330Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Raship N, Sahdan M, Adriyanto F, Nurfazliana M, Bakri A. Effect of annealing temperature on the properties of copper oxide films prepared by dip coating technique. AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing; 2017.10.1063/1.4968374Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Dwivedi LM, Shukla N, Baranwal K, Gupta S, Siddique S, Singh V. Gum Acacia modified Ni doped CuO nanoparticles: an excellent antibacterial material. J Clust Sci. 2021;32:209–19.10.1007/s10876-020-01779-7Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Rezayat M, Karamimoghadam M, Ashkani O, Bodaghi M. Characterization and optimization of Cu-Al2O3 nanocomposites synthesized via high energy planetary milling: a morphological and structural study. J Compos Sci. 2023;7(7):300.10.3390/jcs7070300Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Wu C, Hua W, Zhang Z, Zhong B, Yang Z, Feng G, et al. Design and synthesis of layered Na2Ti3O7 and tunnel Na2Ti6O13 hybrid structures with enhanced electrochemical behavior for sodium‐ion batteries. Adv Sci. 2018;5(9):1800519.10.1002/advs.201800519Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Razi SA, Das NK, Farhad SFU, Bhuiyan MAM. Influence of the CdCl2 solution concentration on the properties of CdTe thin films. Int J Renew Energy Res (IJRER). 2020;10(2):1012–20.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Langford J, Louër D, Scardi P. Effect of a crystallite size distribution on X-ray diffraction line profiles and whole-powder-pattern fitting. J Appl Crystallogr. 2000;33(3):964–74.10.1107/S002188980000460XSuche in Google Scholar

[36] Mitra R, Ungar T, Weertman J. Comparison of grain size measurements by x-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy methods. T Indian Inst Metals. 2005;58:1125.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Ali S, Sharma AS, Ahmad W, Zareef M, Hassan MM, Viswadevarayalu A, et al. Noble metals based bimetallic and trimetallic nanoparticles: controlled synthesis, antimicrobial and anticancer applications. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2021;51(5):454–81.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Rajabi A, Ghazali MJ. Quantitative analyses of TiC nanopowders via mechanical alloying method. Ceram Int. 2017;43(16):14233–43.10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.07.171Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Ayoub I, Kumar V, Abolhassani R, Sehgal R, Sharma V, Sehgal R, et al. Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):575–619.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0035Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Asim N, Su’ait MS, Badiei M, Mohammad M, Akhtaruzzaman M, Rajabi A, et al. Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):1525–54.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0087Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Khan Z, Singh T, Hussain JI, Obaid AY, Al-Thabaiti SA, El-Mossalamy E. Starch-directed green synthesis, characterization and morphology of silver nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2013;102:578–84.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.057Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Zhang X, Xiang G, Zhang J, Yue Z, Liu Y, Zhang J, et al. The preparation of CuO film under different annealing atmospheres and investigation of the excellent electrical and undoped tunable electroluminescence characteristics of Au/i-CuO/n-GaN LED. J Alloy Compd. 2024;973:172885.10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.172885Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Coutts TJ, Young DL, Gessert TA. Modeling, characterization, and properties of transparent conducting oxides. Handb Transparent Conduct. 2011;1:51–110.10.1007/978-1-4419-1638-9_3Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Lee S, McInerney MF. Optimization of bifacial Ge-incorporated Sb2Se3 thin-film solar cells by modeling Cu2O back buffer layer. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cell. 2023;257:112399.10.1016/j.solmat.2023.112399Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Bhattacharya S, John S. Designing high-efficiency thin silicon solar cells using parabolic-pore photonic crystals. Phys Rev Appl. 2018;9(4):044009.10.1103/PhysRevApplied.9.044009Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Farhad SFU, Cherns D, Smith JA, Fox NA, Fermin DJ. Pulsed laser deposition of single-phase n- and p-type Cu2O thin films with low resistivity. Mater & Des. 2020;193:108848.10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108848Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete