Abstract

Viscosity shifts the flow features of a liquid and affects the consistency of a product, which is a primary factor in demonstrating forces that should be overcome when fluids are transported in pipelines or employed in lubrication. In carbon-based materials, due to their extensive use in industry, finding the simple and reliable equations that can predict the rheological behavior is essential. In this research, the rheological nature of graphene/aqueous nanofluid was examined. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and X-ray powder diffraction were used for analyzing the phase and structure. Transmission electron microscopy and field emission scanning electron microscopy were also employed for micro and nano structural-study. Moreover, nanofluid stability was examined via zeta-potential measurement. Results showed that nanofluid has non-Newtonian nature, the same as the power-law form. Further, from 25 to 50°C, at 12.23 s−1, viscosity decreased by 56.9, 54.9, and 38.5% for 1.0, 2.0, and 3.5 mg/mL nanofluids, respectively. From 25 to 50°C, at 122.3 s−1, viscosity decreased by 42.5, 42.3, and 33.3% for 1.0, 2.0, and 3.5 mg/mL nanofluids, respectively. Besides, to determine the viscosity of nanofluid in varied temperatures and mass concentrations, an artificial neural network via R 2 = 0.999 was applied. Finally, the simple and reliable equations that can predict the rheological behavior of graphene/water nanofluid are calculated.

1 Introduction

Nanofluids are modern coolants that have been introduced as an alternative to conventional heat transfer fluids and have earned plenty of recognition because of their remarkable thermal characteristics [1,2,3,4,5]. Nanofluids are composed of nanoparticles (NPs) suspended in base fluids, and in fact, the appearance of NPs with a high heat transfer rate has improved the cooling performance of nanofluids [6,7,8]. So far, many nanofluids have been synthesized, and their thermophysical properties have been measured [9,10,11]. Also, the cooling performance of these nanofluids in various applications has been investigated both experimentally and numerically [12,13,14,15,16]. It has often been noted that the nanofluids improved heat transfer than conventional coolants; however, it cannot be conclusively said that the general hydrothermal efficiency of nanofluids is better than base fluids [17,18,19].

Some of the nanofluid applications are enhancement in wear and friction behavior of varied lubricating oils after adding varied nano additives [20]; alumina-titania Therminol-55 hybrid nanofluid is a heat transfer fluid used in concentrating solar collectors [21]; synergism of graphene (G) with titania increase tribological features and provide a greener and efficient lubrication methodology in turning of M2 steel employing a minimum quantity lubrication method [22].

Aside from the many benefits, nanofluids are not without drawbacks. For example, the NPs enhancement in the base fluid enlarges its viscosity, and therefore, the pumping power required for the flow of nanofluids into a device is often larger than the base fluid [23]. This increase is sometimes so significant that the general hydrothermal efficiency of nanofluid is poorer than base fluid. In such cases, the use of nanofluids is not recommended at all [24]. Commercial obstacles of nanofluid usage in thermal energy application are detected by Alagumalai et al. [25]. According to the before consultation, it could be established that viscosity is one of the highest critical attributes of nanofluids that should be considered. Measurements have shown that many nanofluids are non-Newtonian, meaning that their viscosity at a given temperature is not a fixed number and is a shear rate’s (SR) function [26,27]. Considering these types of nanofluids, rheological behavior must be investigated.

Graphene, a carbon-based material, is a two-dimensional form of carbon that contains atoms located in a single layer [28,29]. Graphene has several applications, some of the most important of which are roll-up and wearable electronics, stimulated aside flexibility, energy depository substances, and polymer formation [30].

Gulzar et al. [21] experimentally studied the rheological features of Therminol-55-Alumina/TiO2 nanofluid. They evaluated the influence of nanoparticle mass fraction (0–0.5%) and temperature (20–60°C) on the outcomes. It was depicted that the nanofluid viscosity rises by boosting nanoparticle fraction and temperature reduction. Aghahadi et al. [31] experimentally examined the rheological features of engine oil-WO2-carbon nanotube (CNT) nanofluid. The impact of NPs volume fraction (0–0.6%) and temperature (20–60°C). They developed a mathematical model to determine the rheological features of nanofluid. Esfe and Rostamian [32] experimentally assessed the change in the viscosity of ethylene glycol–CNT/TiO2 nanofluid via SR, temperature, and NPs vol% parameters. The results showed that nanofluid at low concentrations has Newtonian nature, but increasing the vol% leads to the non-Newtonian nature of nanofluid. Kazemi et al. [33] tested and compared the rheological nature of aqueous–graphene, water–silica, and water–graphene (30%)/silica (70%) nanofluids. It was revealed that all three nanofluids have non-Newtonian behavior and the most severe non-Newtonian behavior belongs to the water–graphene nanofluid. In an empirical contribution, Ma et al. [34] considered the surfactant impact on the rheological behavior of aqueous alumina–CuO and alumina–TiO2 nanofluids. The considered surfactants were sodium dodecyl sulfate, polyvinyl pyrrolidone, and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. Lee et al. [35] explored the temperature impact on the rheological features of carbon-based nanofluids. It was observed that the dynamic viscosity of the examined nanofluid specimen is inferior to the base fluid. While Dalkılıç et al. [36] tested the viscosity aspects of water-based silica–graphite hybrid nanofluids, Sekhar and Sharma [37] also Studied the viscosity and specific heat capacity aspects of water-based alumina nanofluids at minimum particle volume fractions. However, Bahrami et al. [38] did an empirical research on the rheological manner of hybrid nanofluids made of copper/iron oxide in water/ethylene glycol, whose results revealed a non-Newtonian behavior. Zhao et al. [39] did an artificial neural networking (ANN) analysis for entropy/heat generation in the flow of non-Newtonian fluid. Afrand et al. [40] also predicted the viscosity of CNTs/water nanofluid by expanding a desirable ANN based on their empirical data. Moreover, Nguyen et al. [41] studied the efficiency of joined ANN and genetic algorithms on the impact of concentration/temperature in ethanol-based nanofluid.

In many industrial applications, if there are relationships that can anticipate the nanofluid’s thermophysical characteristics with acceptable accuracy, there is no need to measure these properties, which are both time-consuming and costly. This issue has been considered by many researchers, and after measuring the desired property or properties, they have used various techniques to provide an accurate predictive model for that property [42]. One of the methods that have been widely used in the research literature for this mean is the ANN [43,44].

Wahab et al. [45] reported an exergy performance of 14.62% gathered at 0.1% volume fraction and 40 L/m by working liquids of water and graphene nanofluid with 0.05–0.15% volume fractions for the hybrid photovoltaic thermal system. Zheng et al. [46] experimentally evaluated the rheological manner of ethylene glycol–graphene nanofluid at a temperature range of 5–65°C, the mass fraction of NPs of 0–5%, and SR of (0–90 s−1). Hamze et al. [47] investigated shear flow manner of graphene-based nanofluids and also the impact of shearing, and shearing period and temperature on viscosity. Bakhtiari et al. [48] examined the readiness of stable titania–graphene/water nanofluids and developed an equation for heat transfer. Nadooshan et al. [49] measured the rheological manner of magnetite–CNT/ethylene glycol nanofluid to find heat transfer rate, and the results revealed Newtonian behavior for minimum volume fraction and non-Newtonian behavior for maximum volume fraction. Also, Malekahmadi et al. [50] focused on the CNT additive impact on the heat transfer rate of hydroxyapatite/water for dental operations. Shahsavani et al. [51] studied the rheological manner of water–EG/functionalized multi walled CNTs.

As for the research gap, the mentioned studies, and other published papers related to the viscosity of carbon-based materials, did not find the exact correlation for water-based nanofluid containing graphene NPs. Also, the importance of the synthesis process in the viscosity behavior was not mention.

As for the importance, viscosity shifts the flow features of a liquid and affects the consistency of a product; this data is critical in most production steps. Also, viscosity is a primary factor in demonstrating the forces that should be overcome when fluids are transported in pipelines or employed in lubrication. It leads the fluid flow in surface coating, injection molding, and spraying. Viscosity measurement is needed in choosing the antifreeze with minimum viscosity, employed in car engines. Thus, to solve the relevant problems in this regard, we need to measure the viscosity of nanofluids under different conditions, such as SRs, mass concentrations, and temperatures to find the behavior of the fluid. Moreover, we can find out which nanofluid is a better choice for our goal.

As for the key objectives, in the carbon-based materials, especially graphene, due to its extensive use in industry, the exact correlation with the least uncertainty is needed for the scientists to reduce the costs of experiments and the costs in industries. Thus, in this research, after experimental examinations, the numerical study by training ANN models was done to find simple and reliable equations that can predict the rheological manner of water-based nanofluid containing graphene as carbon-based material.

In this study, graphene nanofluid was formed by applying a two-step approach. For this purpose, first, graphene NPs are synthesized by applying the top-down approach. Then, they are dispersed in water at mass concentrations of 1.0–3.5 mg/mL. After preparing the nanofluid samples, their rheological behavior in different mass concentration values and temperatures is measured. Eventually, the ANN technique is selected to obtain a predictive model for the rheological manner of the water–graphene nanofluid.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

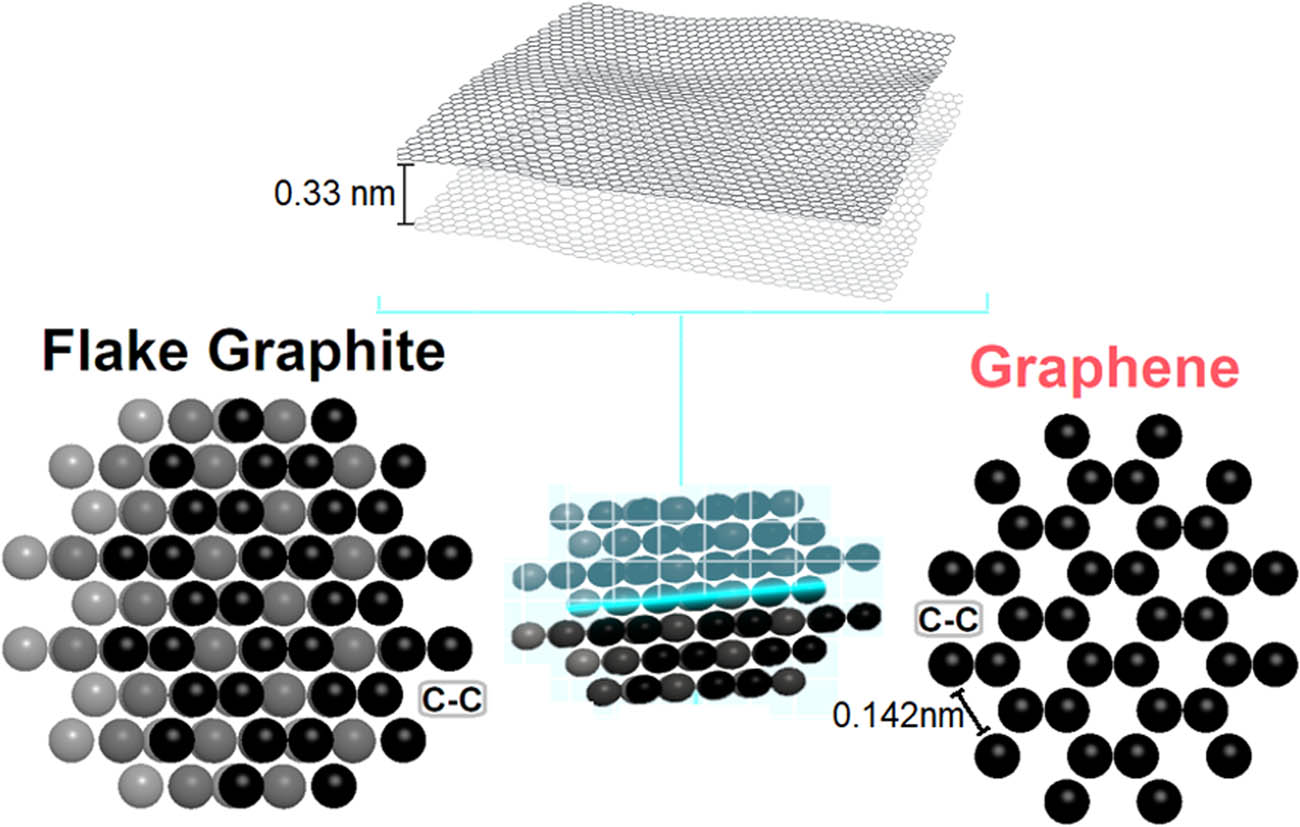

From KaraPA-Iran, graphite in flake form was prepared at 99.8% purity. Moreover, additional materials consumed in the synthesis had purity above 99% and was of analytical grade. Figure 1 displays G/flake graphite (FG) three-dimensional structure design. Further, base fluid and nanomaterial properties are shown in Table 1.

3D-schematic design of graphene and flake graphite.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Solid/nanofluid formation

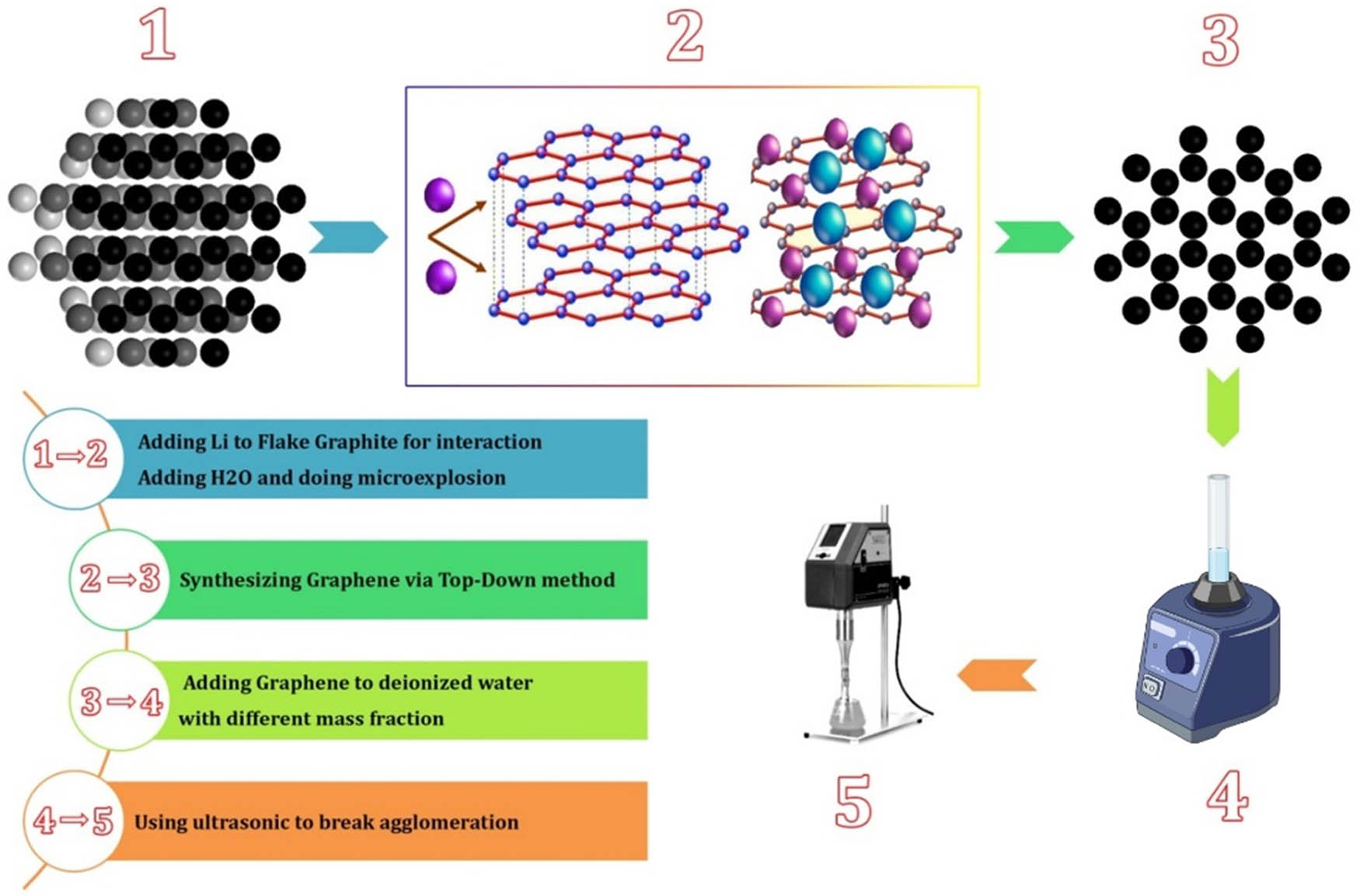

Figure 2 shows graphene powder and nanofluid synthesis and preparation steps. Graphene could be produced by exfoliation of bulk graphite containing direct liquid-phase exfoliation of FG/FG intercalation compound aside from the help of ultrasonication (Figure 2). Lithium is the lightest solid/metal element. In Figure 2, in steps 1 to 2, lithium is employed to be placed between graphite sheets. This helps the micro-explosion between graphite sheets by adding H2O. Further, in steps 2 to 3, when the micro-explosion is completed, the mono-layer sheets of graphene are obtained.

Synthesis steps of powder (schematic diagram from flake graphite to graphene) and preparation steps of nanofluid.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was examined via a D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (Bruker-USA). Moreover, to prove XRD results, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was used. Further, dynamic light scattering (DLS) was tested by a VASCO NP size analyzer (Cordouan Technologies, France). Also, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra was reported using FP-6300 (JASCO, JAPAN). Then, to detect sample morphology, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) was used (Nova NanoSEM 450; FEI, USA) [51].

To measure the thermophysical properties, nanofluid must be prepared first. Graphene must be added to deionized water. Overall mass concentration of graphene consumed in nanofluid can be calculated via equation (1). First, graphene mass is determined via weighing balance in the laboratory, and then the two-stage process is used to prepare the nanofluid. Nanofluids were prepared at mass concentrations of 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.5 mg/mL. In this method, NPs are mixed in base fluid via an appropriate dispersion method, but here, agglomeration is the biggest problem. To achieve good dispersion and avoid agglomeration, 90 min of magnetic stirring and 30 min of sonication are performed via 400 W, 24 kHz UP400St Ultrasonicator (Hielscher, Germany) to prepare a stable suspension [36].

where mass fraction percentage and density are denoted by φ and ρ, respectively. Mass is indicated by “m.”

2.3 Viscosity measurement

In this research, via DV2T viscometer (AMETEK Brookfield, USA), G-distilled water (DW) rheological behavior was determined with 5% uncertainty [52,53]. LV spindle (1–6 MPa s/1–200 RPM) is used to measure rheological behavior [53]. Initially, at room temperature, DV2T was scaled via DW. For every rheological behavior study, tests were repeated 3 times for 25–50°C temperatures at different SRs, independently [54].

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Solid formation

3.1.1 Structural/phase study

3.1.1.1 X-Ray diffraction

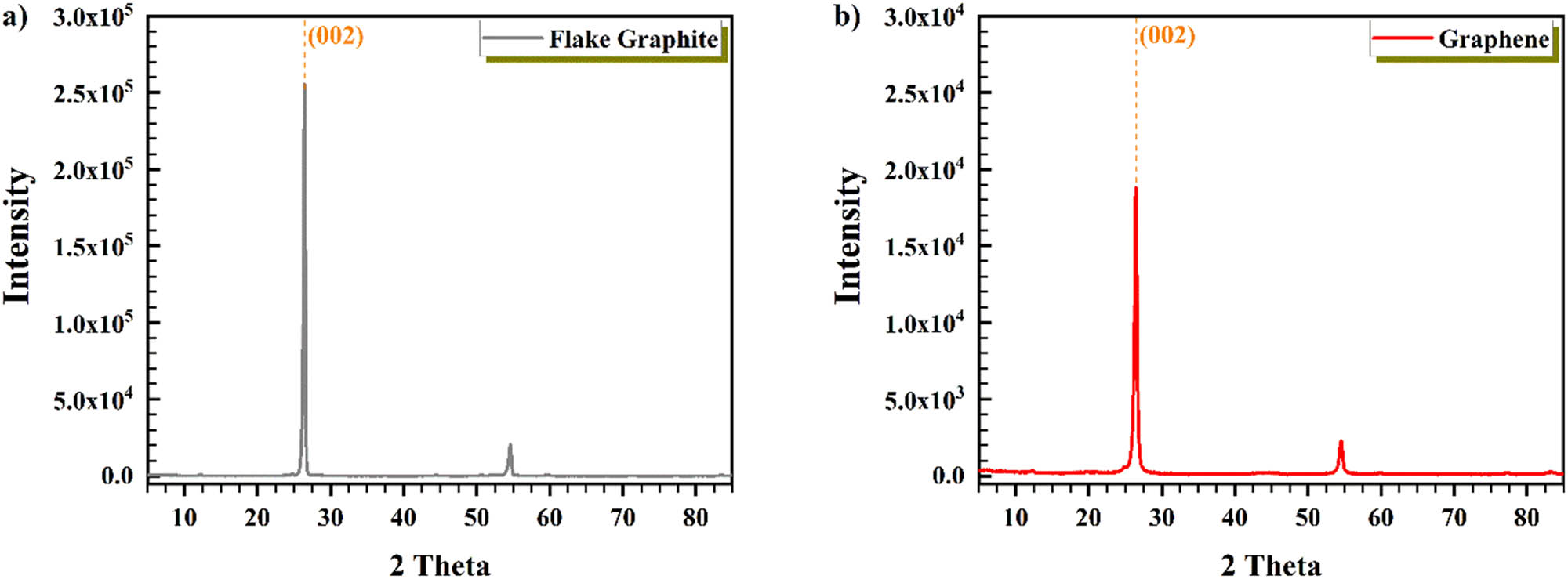

Figure 3 shows the XRD spectra for FG and graphene with a peaked point in (002) surface at 2θ = 26.469°. Low-intensity peaks and (002)-main peak were displayed in the pattern. D-spacing was around 3.362 Ǻ for FG and around 3.363 Ǻ for graphene (Bragg’s law) [55].

XRD pattern of (a) flake graphite and (b) graphene.

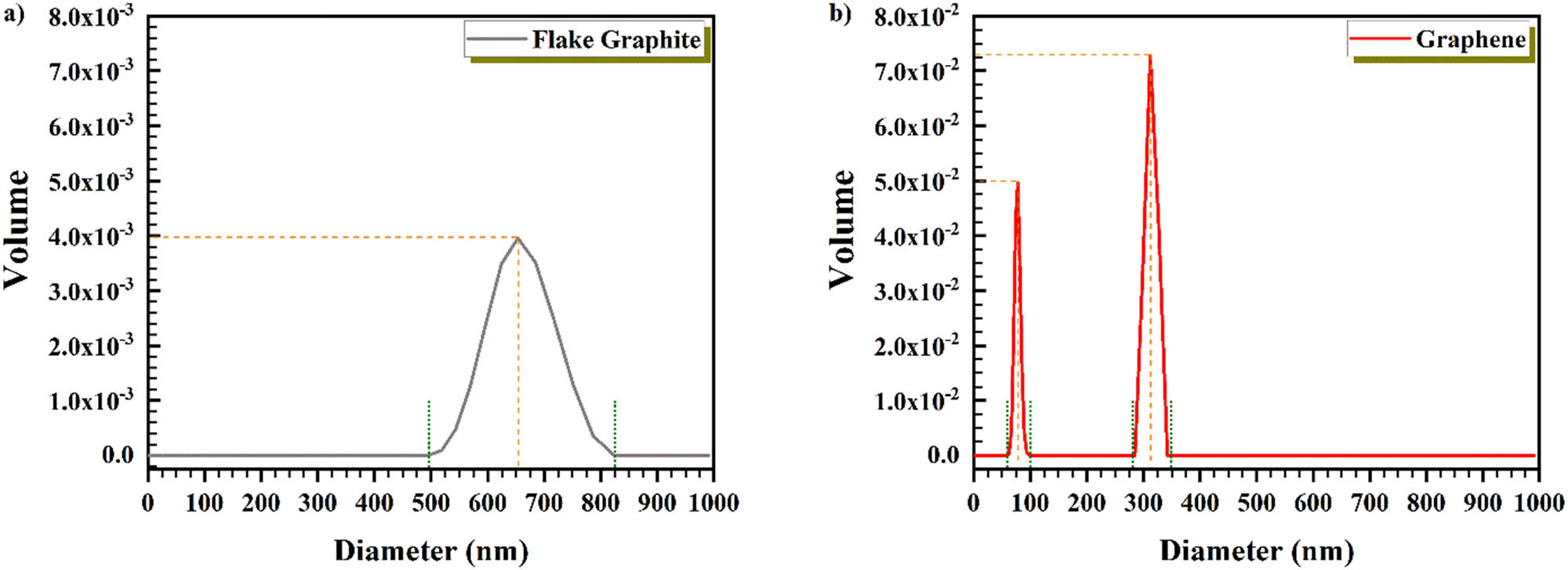

3.1.1.2 DLS

Size distribution for graphite and graphene (water dispersion) was determined by DLS. Graphene has a two-dimensional structure, and a dimension is at the nanoscale. Nevertheless, DLS measured the size of two other dimensions (which are in microscale) alongside its thickness. Figure 4 displays that graphene (49.49 vol% at 76.196 nm and 72.66 vol% at 311.21 nm) has fewer vol% compared to the flake graphite (39.48 vol% at 653.488 nm) [56]. Since graphene has only one dimension in the nanoscale, it is logical that two other dimensions which are in the microscale affect the outcome of DLS and increase the size by more than 100 nm. However, the obtained results also showed that those two dimensions are less than 400 nm which is acceptable.

DLS of (a) flake graphite and (b) graphene.

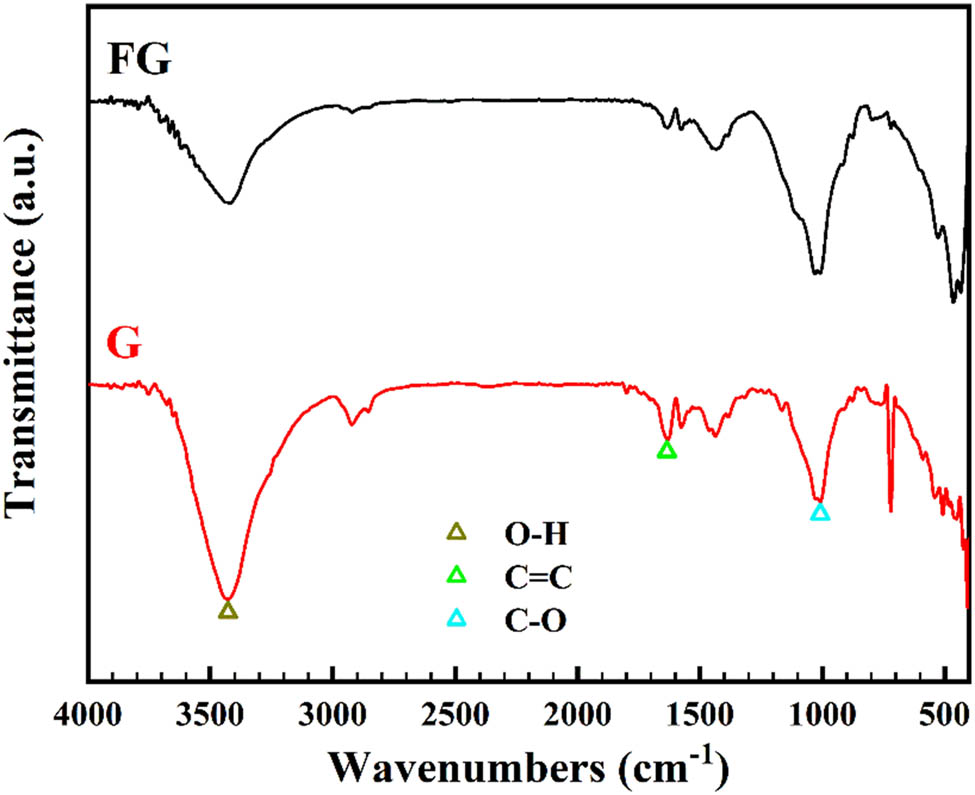

3.1.1.3 FTIR

FTIR spectroscopy was used to study the FG and graphene structure alongside the functional groups. A large peak from 3,000 to 3,732 cm−1 shown in Figure 5 in a large-frequency field is related to the O–H groups of molecules of water for graphene. Likewise, C═C unique peak is shown in 1634.38 cm−1. FG and graphene FTIR in Figure 5, showed that the O–H peak domain has less depth for FG. Aromatic C═C group point at 1624.64 cm−1 in the FG and at 1634.38 cm−1 in graphene. For the FG specimen, C–O has higher intensity (1008.59 cm−1 for G and 1010.99 cm−1 for FG) [57].

FTIR for graphene and flake graphite.

3.1.2 Micro-nano formative study

3.1.2.1 FESEM and EDX analyzer

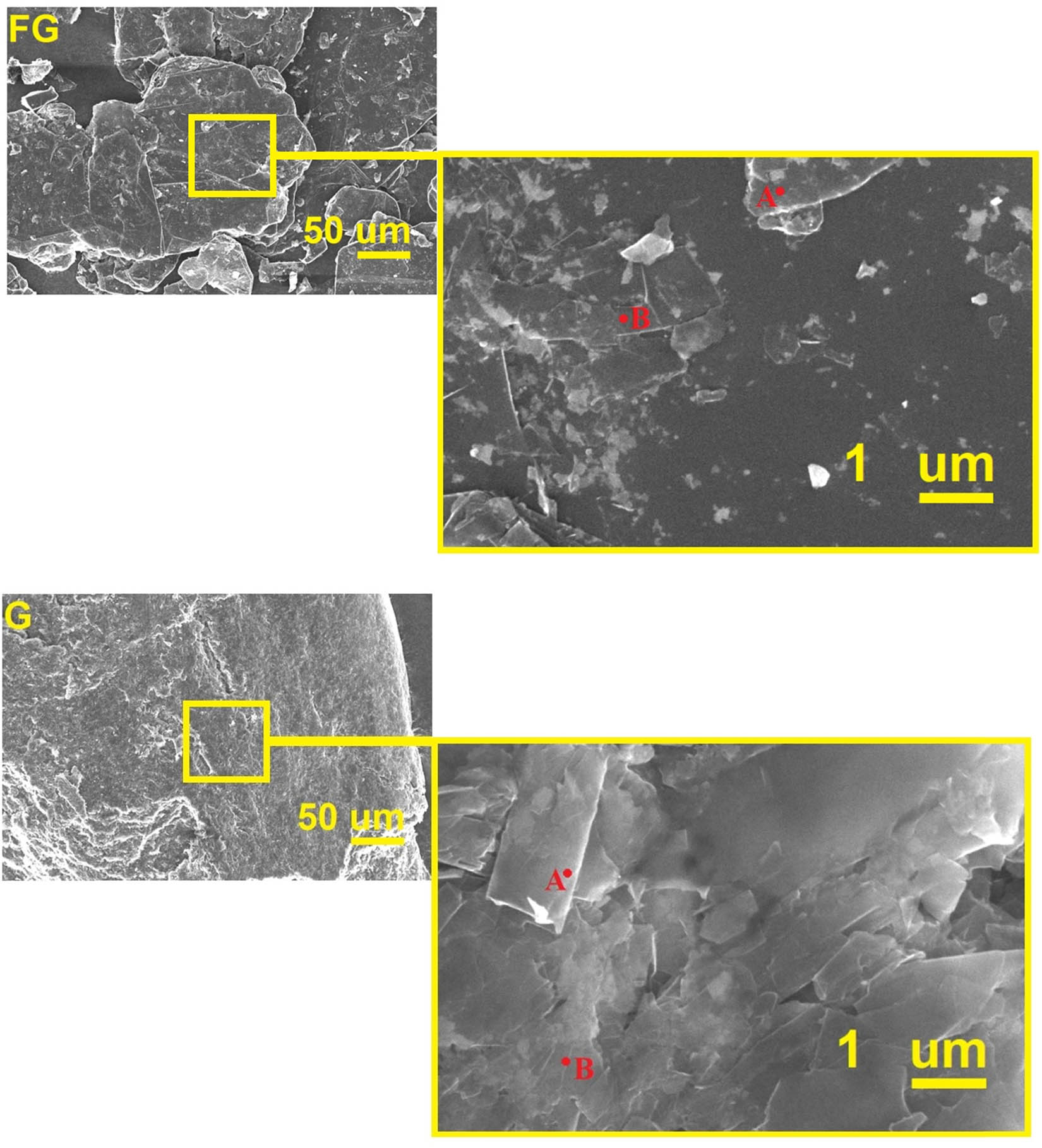

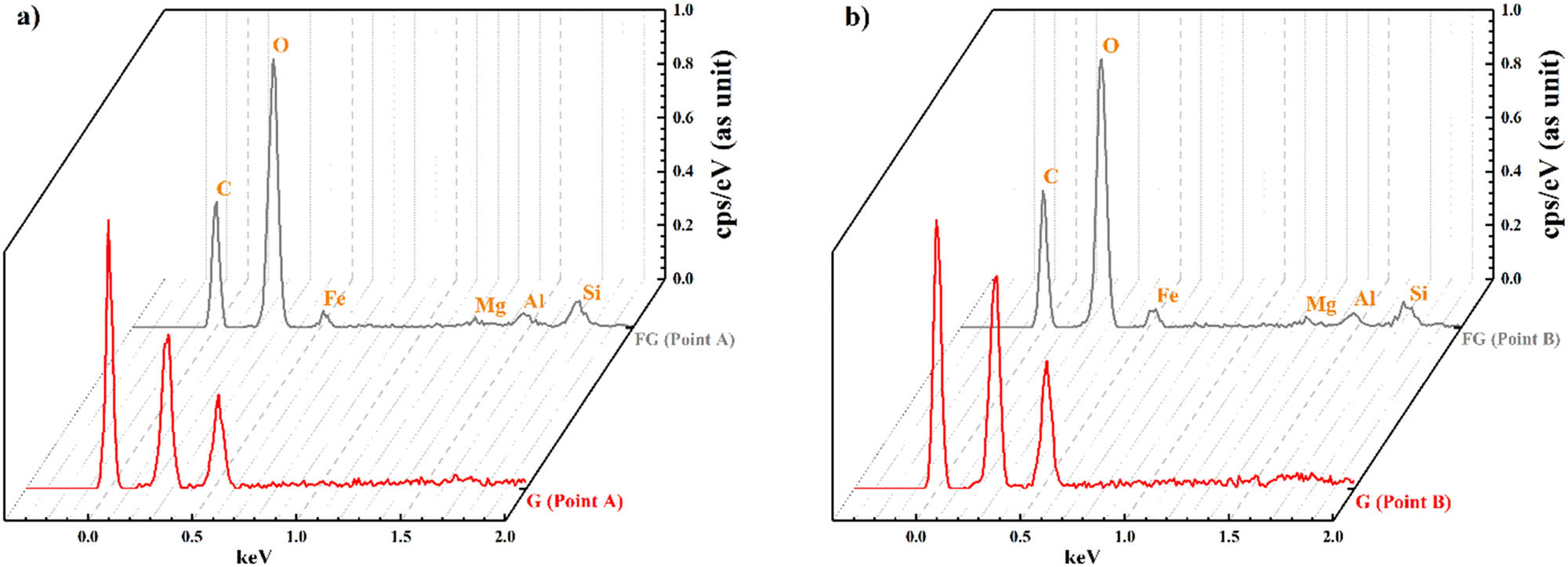

FESEM image of amorphous and disordered two-dimensional graphene is shown in Figure 6 [58]. Graphene thickness is lesser than 100 nm with layer structure. In graphene, folded sections are on top of each other. Flake diameter for graphene layers is reported as 0.5–3.5 µm [58]. Hence, the morphology approved DLS results and showed that all of the dimensions of graphene are less than 400 nm. Also, the one dimension of graphene which is in the nanoscale has less than 100 nm thickness. Two points energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy examined for graphite and graphene. Figure 7 and Table 2 show that FG has about 90.48 at% C, 7.29 at% O, and 2.23 at% Si + N + Al. Nevertheless, graphene is pure at 100 at% C.

FESEM image for graphene and flake graphite.

EDX pattern of flake graphite and graphene for (a) point A and (b) point B.

EDX elemental composition for flake graphite and graphene

| Flake graphite – point A | Graphene – point A | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El AN series unn. C norm. C atom. C error (1 Sigma) | El AN series unn. C norm. C atom. C error (1 Sigma) | ||||||||

| [wt%] | [wt%] | [at%] | [wt%] | [wt%] | [wt%] | [at%] | [wt%] | ||

| C | 86.78 | 86.78 | 90.48 | 14.29 | C | 97.97 | 97.97 | 98.38 | 16.70 |

| O | 9.32 | 9.32 | 7.29 | 4.14 | O | 1.26 | 1.26 | 0.95 | 1.84 |

| Si | 1.78 | 1.78 | 0.79 | 0.16 | N | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 2.34 |

| Al | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.50 | 0.13 | |||||

| N | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 1.95 | |||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Flake graphite – point B | Graphene – point B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El AN series unn. C norm. C atom. C error (1 Sigma) | El AN series unn. C norm. C atom. C error (1 Sigma) | ||||||||

| [wt%] | [wt%] | [at%] | [wt%] | [wt%] | [wt%] | [at%] | [wt%] | ||

| C | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 16.47 | C | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 17.05 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

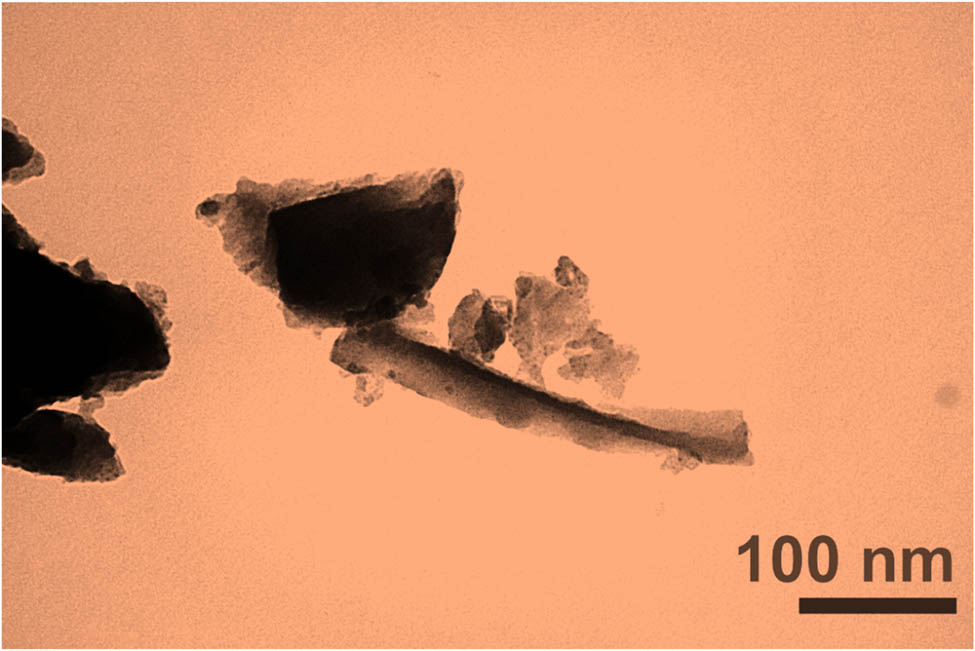

3.1.2.2 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To support that graphene thickness is below 100 nm, TEM was used. For image-making in the TEM method, the electron beam was transferred thru a sample. Figure 8 shows that graphene thickness is lesser than 40 nm with a two-dimensional layer structure [58]. These results were also consistent with that of DLS and FESEM. As can be seen, the thickness of graphene is less than 100 nm.

TEM of graphene.

3.2 Nanofluids formation

3.2.1 Stability of nanofluid

3.2.1.1 Zeta potential

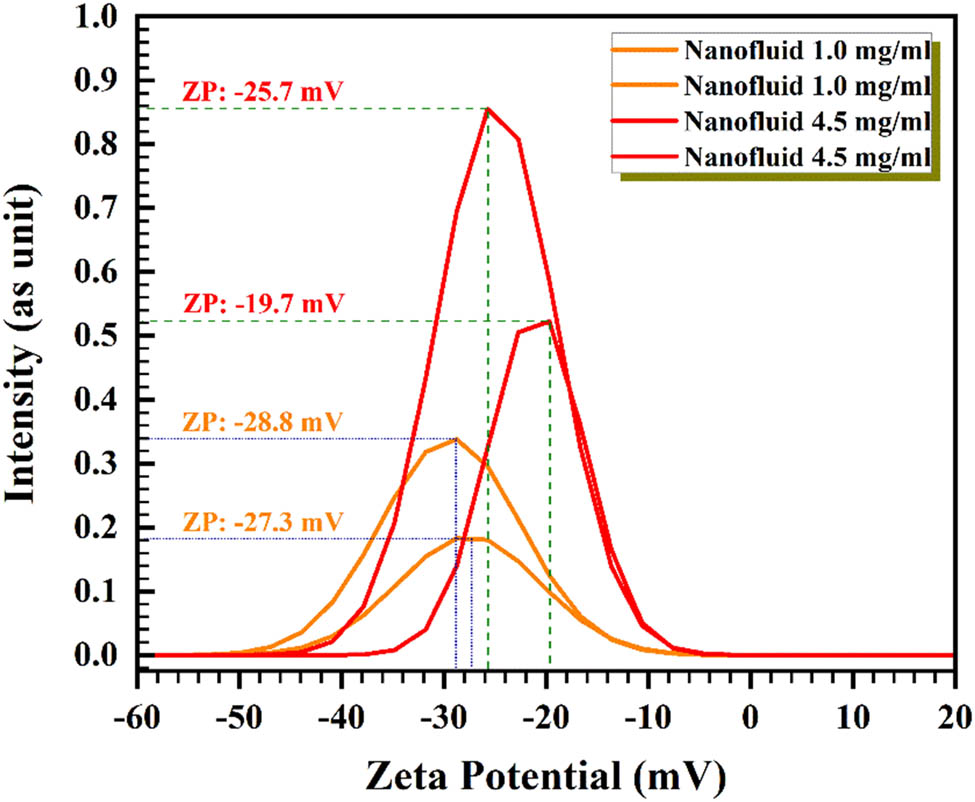

The zeta potential (ZP) of graphene is shown in Figure 9 at mass concentrations of 4.5 and 1.0 mg/mL. The colloid mixture of graphene liquid at the 2–4 pH range shows negative ZP. As announced via ASTM, the absolute zeta potential of 20–30 mV are rather stable, and >±30 mV is extremely stable. ZPs for 1.0 mg/mL, are –28.8 mV (electrophoretic mobility [EM] of –0.000229 cm2/Vs) and –27.3 mV (EM of –0.000214 cm2/Vs), while for 4.5 mg/mL, are –25.7 (EM of –0.000190 cm2/Vs) and –19.7 (EM of –0.000178 cm2/Vs). These amounts show nanomaterial’s moderate stability in water. It can be seen by these values that by increasing the mass concentration, graphene has aggregation behavior [59,60].

ZP pattern of graphene at mass concentrations of 1 and 4.5 mg/mL.

3.2.2 Rheological behavior study

3.2.2.1 Validation

DV2T apparatus validity was determined and related to the ASHRAE handbook [53] to affirm the apparatus correctness. Regarding manual, apparatus uncertainty was satisfying (lesser that 5%) at T = 25°C. Figure 10 displays the maximum error of 4.29% (at T = 40°C) [53].

![Figure 10

Viscosity vs distilled water temperature compared to that in ASHRAE handbook [53].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0155/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0155_fig_010.jpg)

Viscosity vs distilled water temperature compared to that in ASHRAE handbook [53].

3.2.2.2 Mass concentration and temperature effect

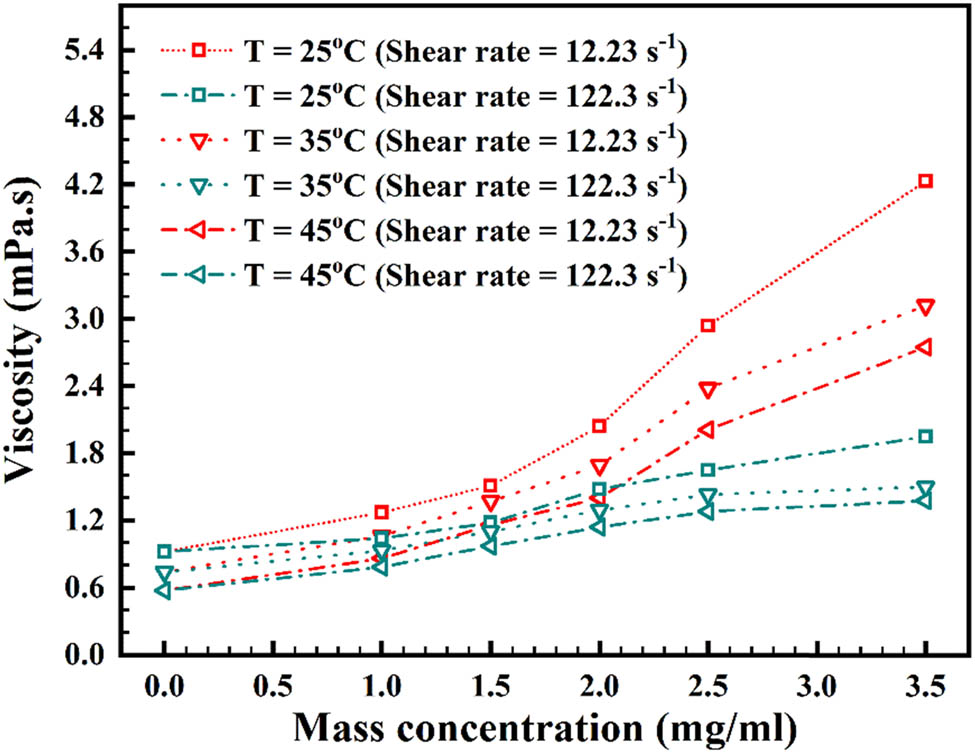

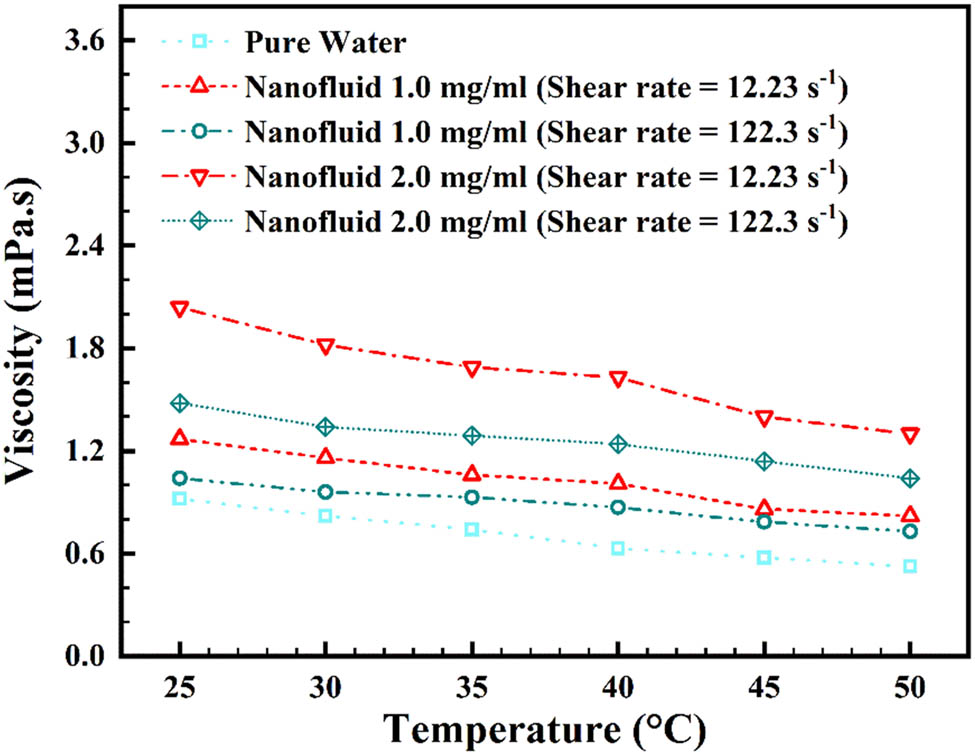

An important stage in determining the nanofluid’s viscosity is to measure it at different mass concentrations and temperatures, to determine whether it exhibits Newtonian/non-Newtonian behavior [61]. For varied temperatures, Figure 11 exhibits viscosity corresponding to mass concentration in 12.23 and 122.3 SRs [62]. At different mass concentrations, Figure 12 exhibits viscosity corresponding to temperature in 12.23 and 122.3 s−1 SRs [63]. On increasing the mass concentration and temperature, there is an increase and decrease in viscosity, respectively. As can be seen, in the 12.23 s−1 SR, from mass concentration of 0.0 to 2.0 mg/mL, the viscosity increment is relatively smooth; but after 2.0–3.5 mg/mL, the enhancement of viscosity is more steep. This is due to the surface tension increment at low speed for the agglomerations. However, this slope increment cannot be seen in the 122.3 s−1 SR, which reveals that with speed increment, the agglomerations are broken, and thus, the friction is decreased. Also, temperature increment causes a decrement in agglomerations, and again, friction is decreased at 45°C.

Change in rheological behavior corresponding to mass concentration at varied temperatures.

Change in rheological behavior corresponding to temperature at varied mass concentrations.

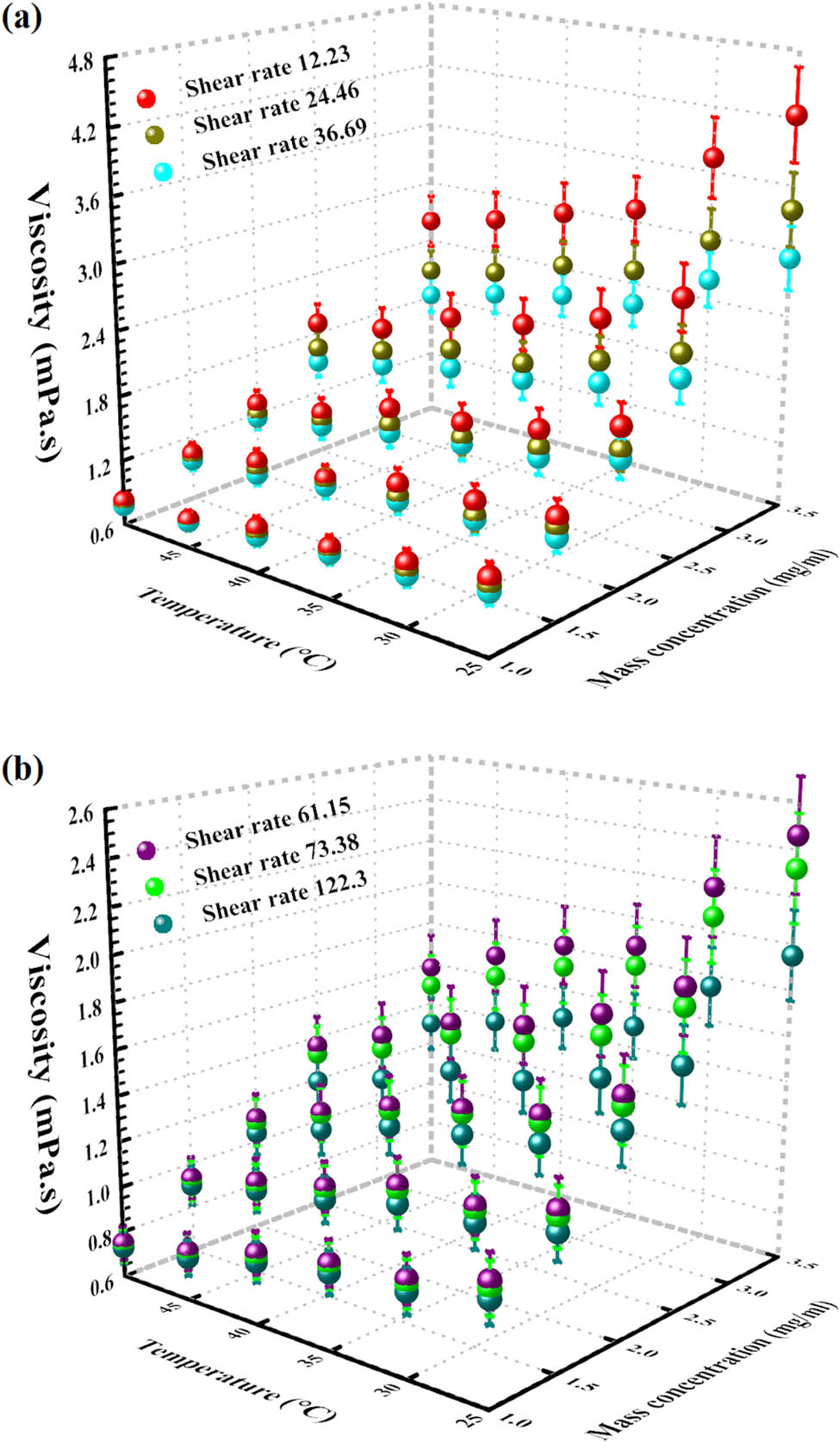

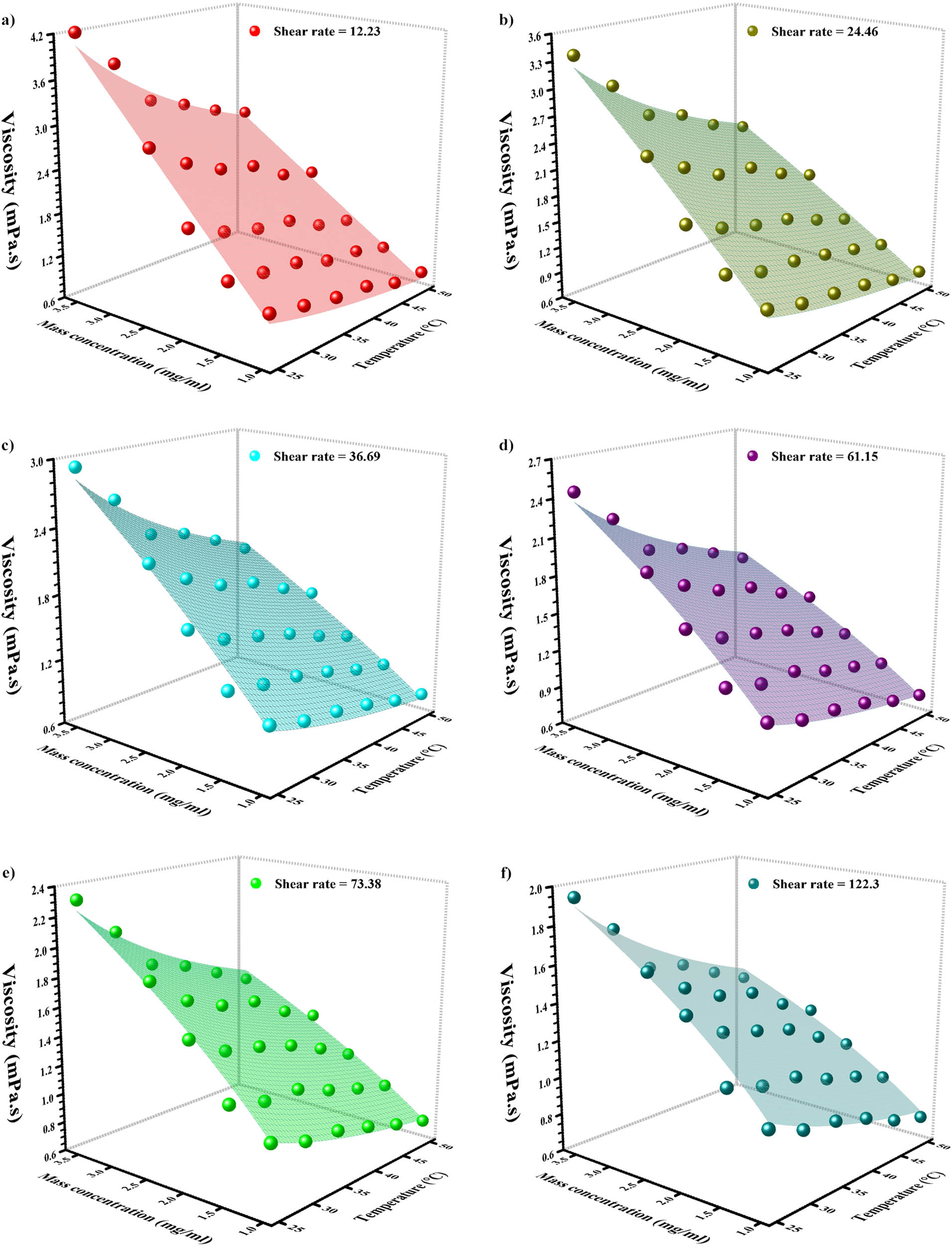

Figure 13 exhibits the rheological behavior 3D data corresponding to various mass concentrations and temperatures from 122.3–12.23 SRs [64]. Viscosity at varied mass concentrations and temperatures is reported in Table 3. As can be seen, with temperature enhancement, there was a decrease in viscosity. Also, the addition of graphene caused an enhancement in viscosity. The viscosity trend is dependent on two variables, temperature and concentration. However, these variables have a different effect on viscosity. To find which one has greater impact, first, a comparison between the minimum and maximum values is needed.

The 3D factual outcome of viscosity at dissimilar temperatures and mass concentrations.

Viscosity at varied temperatures and mass concentrations

| Shear rate (s−1) | T = 25°C (MPa s) | T = 50°C (MPa s) |

|---|---|---|

| Nanofluid 1.0 mg/mL | ||

| 12.23 | 1.27 | 0.82 |

| 122.3 | 1.04 | 0.73 |

| Nanofluid 2.0 mg/mL | ||

| 12.23 | 2.04 | 1.30 |

| 122.3 | 1.48 | 1.04 |

| Nanofluid 3.5 mg/mL | ||

| 12.23 | 4.23 | 2.60 |

| 122.3 | 1.95 | 1.30 |

When the temperature is constant, the mass concentration impact can be measured. For 25°C which is in the room-temperature domain, viscosity for 1.0 mg/mL graphene was 1.27 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.04 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR), while it reached to 2.04 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.48 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) for 2.0 mg/mL graphene, then it reached to 4.23 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.95 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) for 3.5 mg/mL graphene. This means by adding more graphene, from 1.0 to 3.5 mg/mL, viscosity increment was 233.07% (12.23 s−1 SR) and 87.50% (122.3 s−1 SR).

For 50°C, which is in the heating domain, viscosity for 1.0 mg/mL graphene was 0.82 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 0.73 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR), while it reached to 1.30 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.04 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) for 2.0 mg/mL graphene, then it reached to 2.60 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.30 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) for 3.5 mg/mL graphene. This means by adding more graphene, from 1.0 to 3.5 mg/mL, viscosity increment was 217.07% (12.23 s−1 SR) and 78.08% (122.3 s−1 SR).

When the mass concentration is constant, the temperature impact can be measured. For 1.0 mg/mL graphene/water nanofluid, viscosity at 25°C was 1.27 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.04 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR), while it decreased to 0.82 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 0.73 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) on increasing the temperature to 50°C. This means by increasing the temperature, and on reaching the heating domain, from 25–50°C, viscosity decrement was 35.43% (12.23 s−1 SR) and 29.81% (122.3 s−1 SR).

For 2.0 mg/mL graphene/water nanofluid, viscosity at 25°C was 2.04 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.48 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR), while it decreased to 1.30 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.04 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) on increasing the temperature to 50°C. This means by increasing the temperature, and on reaching the heating domain, from 25–50°C, viscosity decrement was 36.27% (12.23 s−1 SR) and 29.73% (122.3 s−1 shear rate).

For 3.5 mg/mL graphene/water nanofluid, viscosity at 25°C was 4.23 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.95 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR), while it decreased to 2.60 MPa s (12.23 s−1 SR) and 1.30 MPa s (122.3 s−1 SR) on increasing the temperature to 50°C. This means that by increasing the temperature and on reaching the a heating domain, from 25°C–50°C, viscosity decrement was 38.53% (12.23 s−1 SR) and 33.33% (122.3 s−1 SR). This means that temperature caused a decrement in viscosity; however, in 3.5 mg/mL graphene, this decrement was more. Further, the rheological behavior of water became as non-Newtonian after adding graphene to water.

3.2.2.3 Non-Newtonian behavior

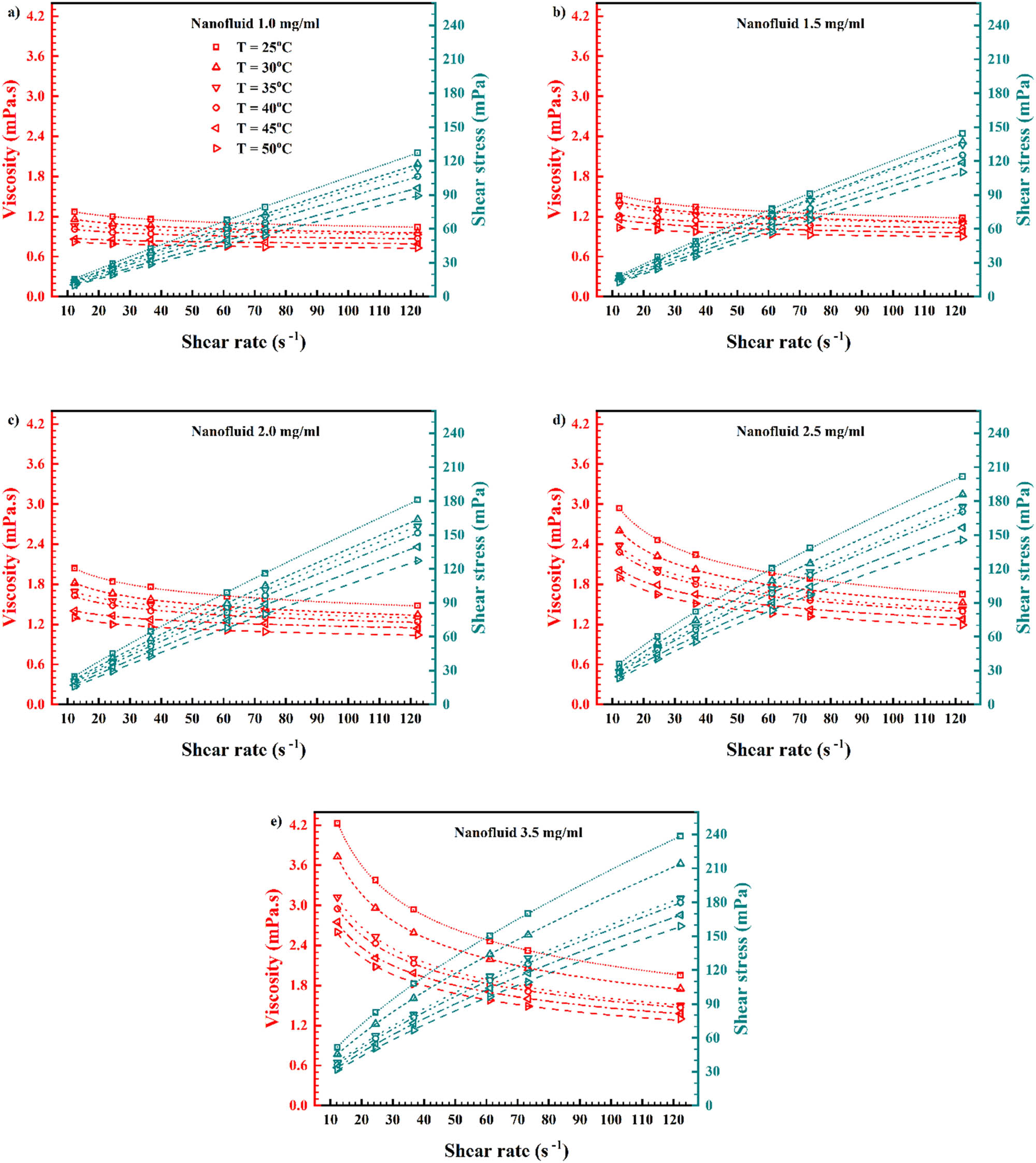

Figure 14 displays the viscosity–shear stress (SS) of nanofluid corresponding to SR for temperatures of 25–50°C and mass concentrations of 1.0–3.5 mg/mL. Nanofluid’s rheological behavior indicated a non-Newtonian manner. Categorizations for non-Newtonian manner are time self-reliant (shear thinning/shear thickening) and time reliant [65]. In G–DW, power is less than one (in the equation of power-law), which causes the shear-thinning (pseudoplastic) [66]. Power law:

where n (dimensionless) is the power law index, m (Pa S

n

) is the flow consistency index, and τ(Pa) denotes SS, and

Viscosity and shear stress values against SR for different mass concentrations and temperatures.

Hence, equation (3) estimates the viscosity:

where “µ” denotes viscosity [67].

The trend for viscosity – SS by SR is non-linear. Therefore, concluding based on the patterns, SS is a variable of temperature and mass concentration. Hence, n or m with varied temperature or mass concentration could be estimated using curve-fitting plus equation (4).

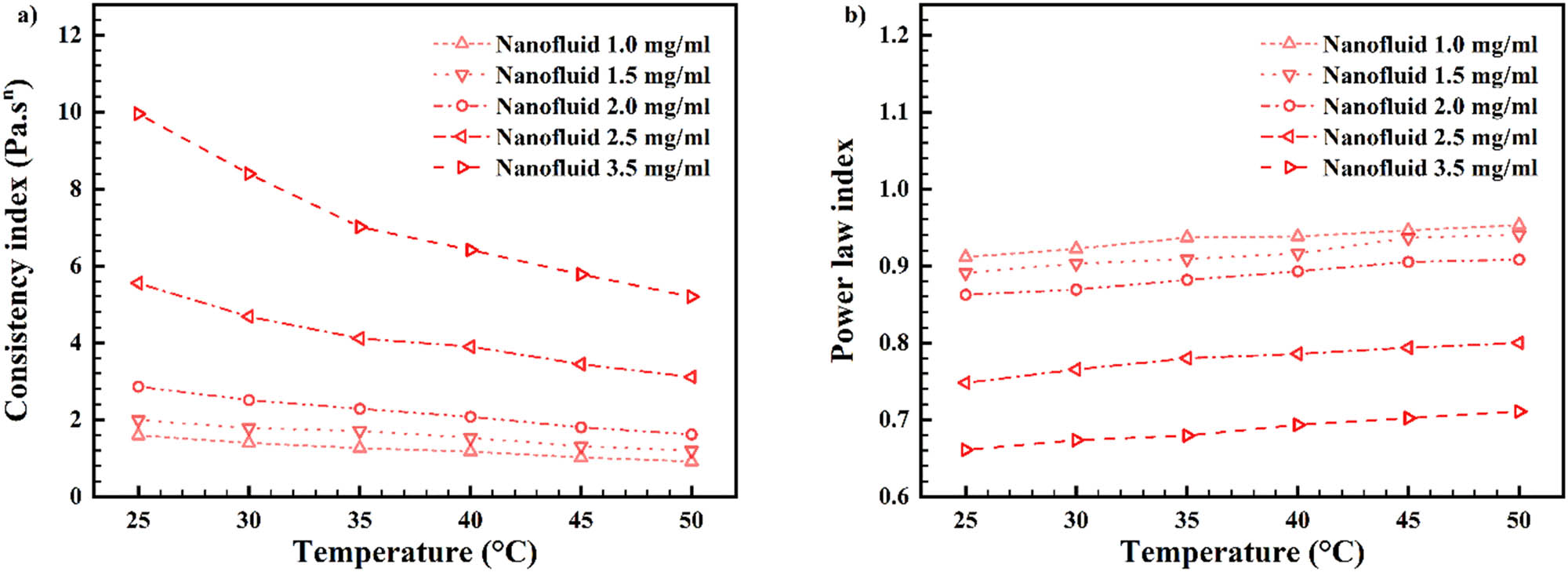

In Figure 15, m (consistency index) and n (power-law index) variations are made known concerning nanofluid’s non-Newtonian nature and Figure 14 data. Figure 15a exhibits consistency index; in conclusion, mass concentration increment caused the “m” increment, but temperature increment for each wt% caused the “m” decrement [68]. Figure 15b exhibits power-law index (n); in conclusion, mass concentration increment caused the “n” decrement, but temperature increment for each wt% caused the “n” increment [69]. This happened because the viscosity decreased after temperature increment, which caused the nanofluid to act the same way as the Newtonian nature of DW base fluid.

Consistency index “m” (a) and power-law index “n” (b) against temperature for various mass concentrations.

3.2.3 Statistical view

3.2.3.1 Recommended equation

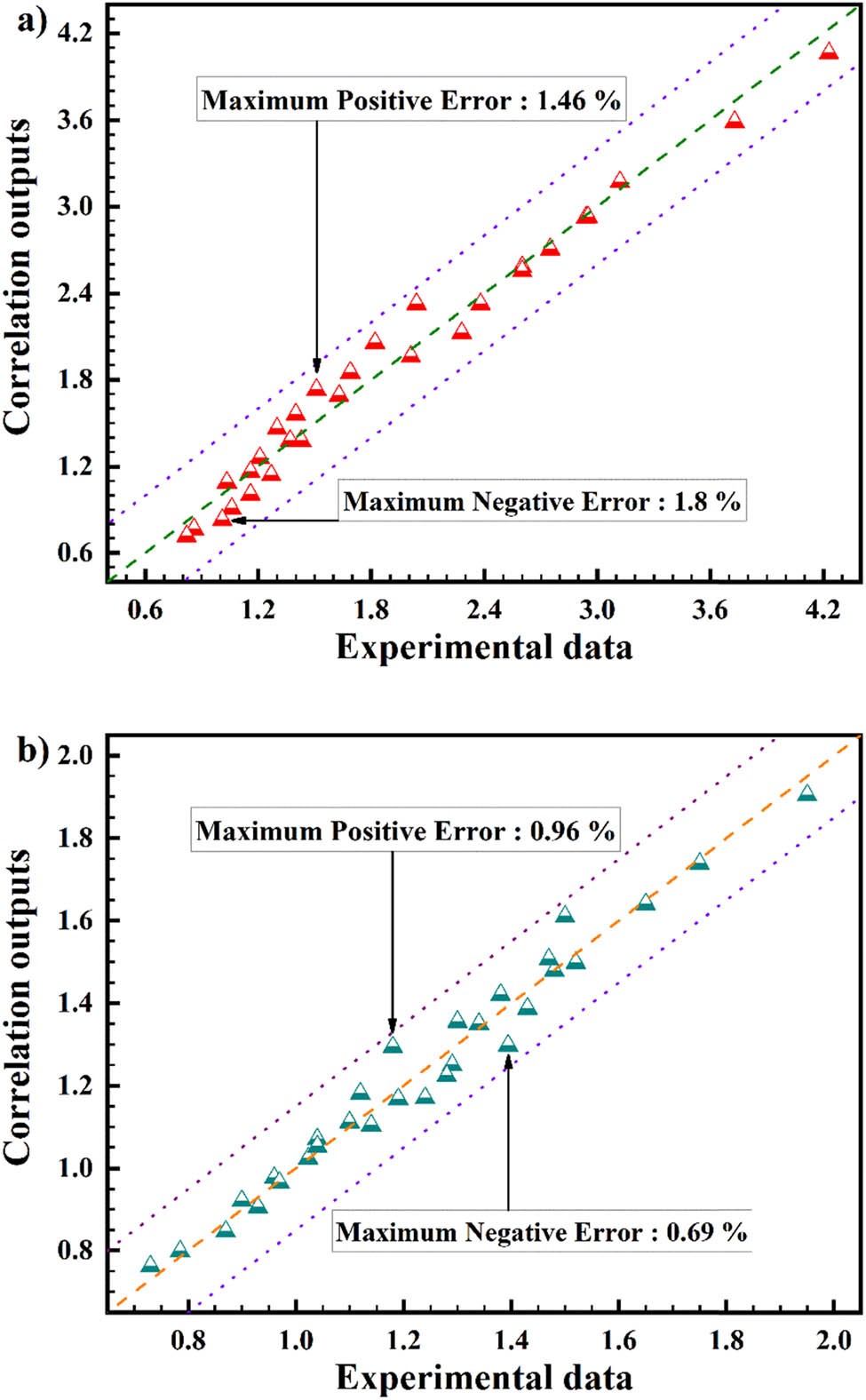

G–DW nanofluid correlation is recommended for estimating viscosity via curve-fitting (equations (5)–(10)). These correlations have R 2 ∼ 0.99 [70]. Three-dimensional fitted correlation on empirical input of 12.23–122.3 SRs is displayed in Figure 16.

Confirmation of recommended correlation with original measurements; Viscosity via mass concentration and nanofluid temperature for varied SRs.

Reduced Chi-Square: 0.00622, R 2 (Coefficient of determination): 0.99687, and adjusted R 2 : 0.99664,

Reduced Chi-Square: 0.00909, R 2 : 0.97995, and adjusted R 2 : 0.97847,

Reduced Chi-Square: 0.00616, R 2 : 0.98006, and adjusted R 2 -Square: 0.97859,

Reduced Chi-Square: 0.00362, R 2 : 0.98062, and adjusted R 2 : 0.97918,

Reduced Chi-Square: 0.00323, R 2 : 0.97934, and adjusted R 2 : 0.97781,

Reduced Chi-Square: 0.0019, R 2 : 0.99872, and adjusted R 2 : 0.99863,

where “T” and “wt” are temperature and mass concentration, respectively, and “T 0” is 25°C, and viscosity is in centipoise [71].

The recommended equation could be confirmed by the original viscosity information. Equation (11) is employed to correlate deviation. The highest deviation of margin exhibited in Figure 17, which quantified 1.8% (for 10 RPM) and 0.96% (for 100 RPM), exhibits such original equation with significant accuracy [71].

Affirmation of original correlation with from factual data for (a) 10 RPM and (b) 100 RPM.

3.2.3.2 ANN

In this study, viscosity for each SR (12.23, 24.46, 36.69, 61.15, 73.38, and 122.3 s−1), in 5 mass concentrations (1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.5 mg/mL), and 6 temperatures (25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50°C) were measured. This means that for each SR, 30 data (5 mass concentrations for 6 temperatures) were measured. However, the gap between the measured values is unknown.

To cut down the data-gathering cost and to find all the data for each mass concentration or temperature, ANN modeling was done with an acceptable margin of deviation. Thus, any researcher who wants to calculate the viscosity of graphene/water at any mass concentration or temperature can use the original equations in this study.

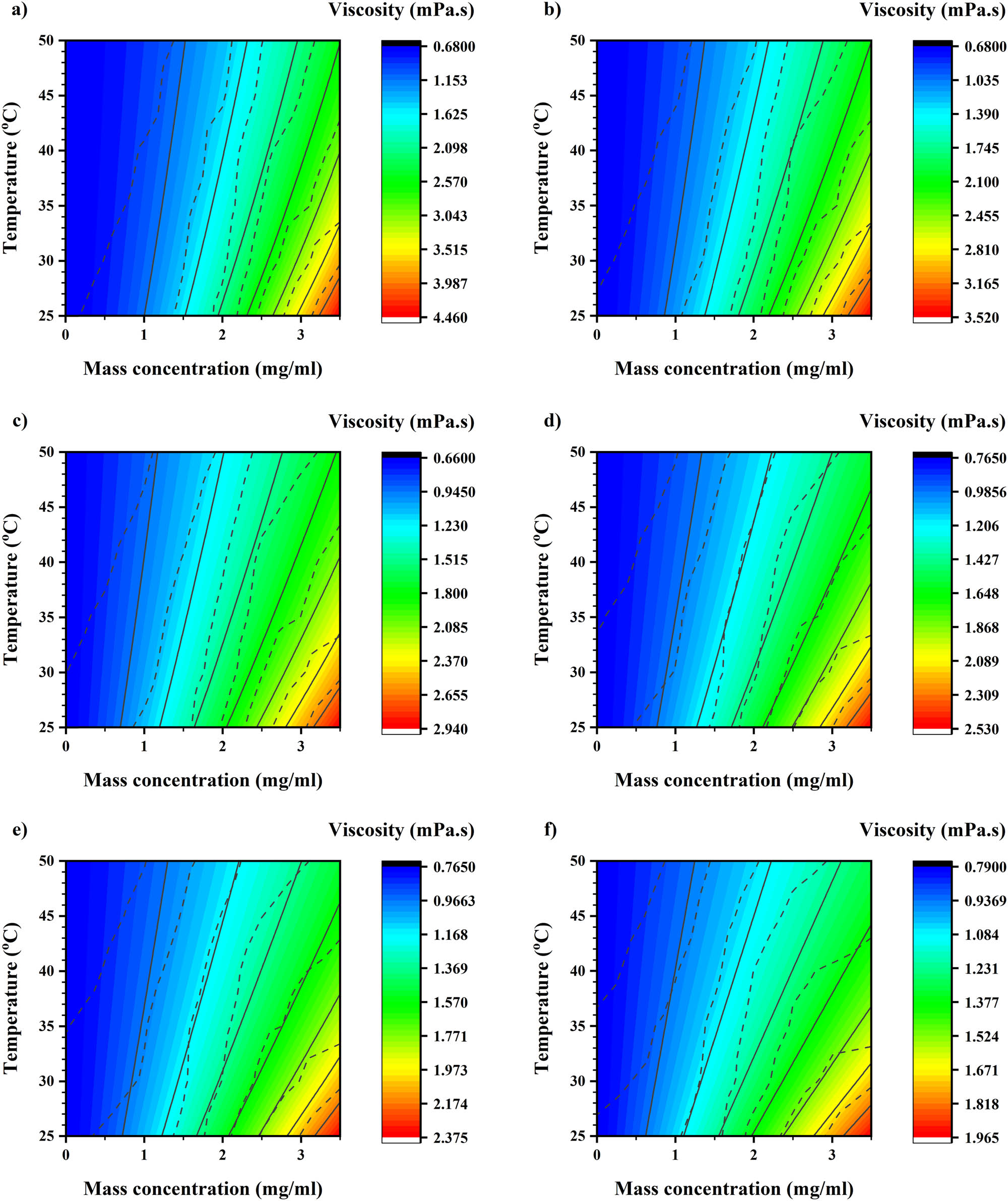

Graphene viscosity was modeled in this study. There are three inputs for this model: SR, mass concentration, and temperature. Also, Output for this model is viscosity [71]. Thus, an ANN was applied. ANN has the output and hidden layers. The output layer has a linear transfer function, while 16 sigmoid neurons are in the hidden layer. For the training algorithm, the Bayesian regularization backpropagation is engaged [72–74]. A model trained for 122.3–12.23 (1/s). Figure 18 displays the main data contour as dashed lines, while the trained data contour is shown as solid lines. It is noticeable that SR critically affects foretoken viscosity. Further, it is detected that viscosity increases with mass concentration increment. However, it decreases with the temperature increment. Also, mass concentration has a major impact [75–77]. ANN is successful in predicting behaviors of the nanofluid stand on viscosity’s analytical variations, which gained in non-modeled temperature, SR, and wt%. The optimum hidden neurons number is 2/3 the size of the input layer plus the size of the output layer. Equations (12) and (13) are the ANN equations set on the empirical viscosity data.

Main outcome (dashed lines) and trained outcome (solid lines) contour at (a) 10, (b) 20, (c) 30, (d) 50, (e) 60, and (f) 100 RPM.

For 12.23 s−1:

And for 122.3 s−1:

where “T” and “wt” are temperature and mass concentration, respectively, “T 0” is 25°C, and viscosity is in centipoise [71].

4 Conclusion

In this research, graphene, a two-dimensional material, was produced via the top-down technique while a homogeneous and stable nanofluid was made. Then, graphene–water nanofluid dynamic viscosity at a temperature range of 25–50°C and mass concentration range of 1.0–3.5 mg/mL was measured. Newtonian behavior appeared in the base fluid, but though graphene was dispersed in DW, nanofluid demonstrated the non-Newtonian (pseudoplastic behavior).

Viscosity shifts the flow features of a liquid which is a primary factor in demonstrating forces that should be overcome when fluids are transported in pipelines or employed in lubrication. Thus, the following results conclude which temperature and which concentration should be used:

For 1.0 mg/mL nanofluid, from 25–50°C at 10 RPM, viscosity decreased by 56.9% and at 100 RPM, viscosity decreased by 42.5%.

For 2.0 mg/mL nanofluid, from 25–50°C at 10 RPM, viscosity decreased by 54.9% and at 100 RPM, viscosity decreased by 42.3%.

For 3.5 mg/mL nanofluid, from 25–50°C at 10 RPM, viscosity decreased by 38.5% and at 100 RPM, viscosity decreased by 33.3%.

Finally, the simple and reliable equations that can predict the rheological behavior of graphene/water nanofluid are calculated with R 2 = 0.99 (deviation).

For future works, the viscosity of other carbon-based materials instead of graphene can be compared with this study. Also, the water can be replaced by oil, ethylene glycol, propylene glycol, etc., and the results can be compared with this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Najran University for funding this work under the Research Collaboration Funding program grant code (NU/RC/SERC/11/9). Also, the authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG).

-

Funding information: Research funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Najran University under the Research Collaboration Funding program grant code (NU/RC/SERC/11/9). Also, the authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Said Z, Hachicha AA, Aberoumand S, Yousef BA, Sayed ET, Bellos E. Recent advances on nanofluids for low to medium temperature solar collectors: energy, exergy, economic analysis and environmental impact. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2021;84:100898. 10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100898.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Asadi A, Aberoumand S, Moradikazerouni A, Pourfattah F, Żyła G, Estellé P, et al. Recent advances in preparation methods and thermophysical properties of oil-based nanofluids: A state-of-the-art review. Powder Technol. 2019;352:209–26. 10.1016/j.powtec.2019.04.054.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Chu YM, Nazir U, Sohail M, Selim MM, Lee JR. Enhancement in thermal energy and solute particles using hybrid nanoparticles by engaging activation energy and chemical reaction over a parabolic surface via finite element approach. Fractal Fract. 2021;5(3):119. 10.3390/fractalfract5030119.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Alqaed S, Mustafa J, Sharifpur M, Cheraghian G. Using nanoparticles in solar collector to enhance solar-assisted hot process stream usefulness. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2022;52(4):101992. 10.1016/j.seta.2022.101992.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Almehmadi FA, Alqaed S, Mustafa J, Jamil B, Sharifpur M. Combining an active method and a passive method in cooling lithium-ion batteries and using the generated heat in heating a residential unit. J Energy Storage. 2022;49:104181. 10.1016/j.est.2022.104181.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Ma M, Zhai Y, Yao P, Li Y, Wang H. Synergistic mechanism of thermal conductivity enhancement and economic analysis of hybrid nanofluids. Powder Technol. 2020;373:702–15. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.07.020.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Mustafa J, Almehmadi FA, Alqaed S. A novel study to examine dependency of indoor temperature and PCM to reduce energy consumption in buildings. J Build Eng. 2022;51(6):104249.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104249Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Alqaed S, Mustafa J, Almehmadi FA. The effect of using phase change materials in a solar wall on the number of times of air conditioning per hour during day and night in different thicknesses of the solar wall. J Build Eng. 2022;51(A):104227.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104227Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Cakmak NK, Said Z, Sundar LS, Ali ZM, Tiwari AK. Preparation, characterization, stability, and thermal conductivity of rGO-Fe3O4-TiO2 hybrid nanofluid: An experimental study. Powder Technol. 2020;372:235–45. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.06.012.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Mustafa J, Alqaed S, Sharifpur M. Incorporating nano-scale material in solar system to reduce domestic hot water energy demand. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2022;49(3):101735.10.1016/j.seta.2021.101735Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Amirahmad A, Maglad AM, Mustafa J, Cheraghian G. Loading PCM into buildings envelope to decrease heat gain-performing transient thermal analysis on nanofluid filled solar system. Front Energy Res. 2021;9:727011.10.3389/fenrg.2021.727011Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Bretado-de los Rios MS, Rivera-Solorio CI, Nigam KD. An overview of sustainability of heat exchangers and solar thermal applications with nanofluids: A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;142:110855. 10.1016/j.rser.2021.110855.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Ma J, Shahsavar A, Al-Rashed AA, Karimipour A, Yarmand H, Rostami S. Viscosity, cloud point, freezing point and flash point of zinc oxide/SAE50 nanolubricant. J Mol Liq. 2020;298:112045. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112045.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Nazeer M, Hussain F, Khan MI, El-Zahar ER, Chu YM, Malik MY. Theoretical study of MHD electro-osmotically flow of third-grade fluid in micro channel. Appl Math Comput. 2022;420:126868. 10.1016/j.amc.2021.126868.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Chu YM, Shankaralingappa BM, Gireesha BJ, Alzahrani F, Khan MI, Khan SU. Combined impact of Cattaneo-Christov double diffusion and radiative heat flux on bio-convective flow of Maxwell liquid configured by a stretched nano-material surface. Appl Math Comput. 2022;419:126883. 10.1016/j.amc.2021.126883.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Wang F, Khan MN, Ahmad I, Ahmad H, Abu-Zinadah H, Chu YM. Numerical solution of traveling waves in chemical kinetics: time-fractional fishers equations. Fractals. 2022;2240051. 10.1142/S0218348X22400515.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Alsarraf J, Shahsavar A, Khaki M, Ranjbarzadeh R, Karimipour A, Afrand M. Numerical investigation on the effect of four constant temperature pipes on natural cooling of electronic heat sink by nanofluids: a multifunctional optimization. Adv Powder Technol. 2020;31(1):416–32. 10.1016/j.apt.2019.10.035.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Niknejadi M, Afrand M, Karimipour A, Shahsavar A, Isfahani AH. Experimental investigation of the hydrothermal aspects of water–Fe3O4 nanofluid inside a twisted tube. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2020;143:1–10. 10.1007/s10973-020-09271-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Mustafa J, Alqaed S, Kalbasi R. Challenging of using CuO nanoparticles in a flat plate solar collector- Energy saving in a solar-assisted hot process stream. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2021;124(2):258–65.10.1016/j.jtice.2021.04.003Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Ashraf A, Shafi WK, Ul Haq MI, Raina A. Dispersion stability of nano additives in lubricating oils–an overview of mechanisms, theories and methodologies. Tribol-Mater Surf Interfaces. 2022;16(1):34–56. 10.1080/17515831.2021.1981720.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Gulzar O, Qayoum A, Gupta R. Experimental study on stability and rheological behaviour of hybrid Al2O3-TiO2 Therminol-55 nanofluids for concentrating solar collectors. Powder Technol. 2019;352:436–44, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0032591019303080.10.1016/j.powtec.2019.04.060Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Anand R, Raina A, Irfan Ul Haq M, Mir MJ, Gulzar O, Wani MF. Synergism of TiO2 and graphene as nano-additives in bio-based cutting fluid – An experimental investigation. Tribol Trans. 2021;64(2):350–66. 10.1080/10402004.2020.1842953.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Alshayji A, Asadi A, Alarifi IM. On the heat transfer effectiveness and pumping power assessment of a diamond-water nanofluid based on thermophysical properties: an experimental study. Powder Technol. 2020;373:397–410. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.06.068.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Maghrabie HM, Attalla M, Mohsen AA. Performance assessment of a shell and helically coiled tube heat exchanger with variable orientations utilizing different nanofluids. Appl Therm Eng. 2021;182:116013. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.116013.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Alagumalai A, Qin C, Vimal KE, Solomin E, Yang L, Zhang P, et al. Conceptual analysis framework development to understand barriers of nanofluid commercialization. Nano Energy. 2022;92:106736. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106736.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Yan SR, Kalbasi R, Nguyen Q, Karimipour A. Rheological behavior of hybrid MWCNTs-TiO2/EG nanofluid: a comprehensive modeling and experimental study. J Mol Liq. 2020;308:113058. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113058.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Tian XX, Kalbasi R, Jahanshahi R, Qi C, Huang HL, Rostami S. Competition between intermolecular forces of adhesion and cohesion in the presence of Graphene nanoparticles: Investigation of Graphene nanosheets/ethylene glycol surface tension. J Mol Liq. 2020;311:113329. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113329.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Chen J, Li Y, Huang L, Li C, Shi G. High-yield preparation of Graphene oxide from small graphite flakes via an improved Hummers method with a simple purification process. Carbon. 2015;81:826–34. 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.10.033.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Fu C, Zhao G, Zhang H, Li S. Evaluation and characterization of reduced Graphene oxide nanosheets as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2013;8 (5):6269–80.10.1016/S1452-3981(23)14760-2Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Alam SN, Sharma N, Kumar L. Synthesis of Graphene oxide (GO) by modified hummers method and its thermal reduction to obtain reduced Graphene oxide (rGO). Graphene. 2017;6(1):1–18. 10.4236/Graphene.2017.61001.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Aghahadi MH, Niknejadi M, Toghraie D. An experimental study on the rheological behavior of hybrid Tungsten oxide (WO3)-MWCNTs/engine oil Newtonian nanofluids. J Mol Structure. 2019;1197:497–507. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.07.080.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Esfe MH, Rostamian SH. Rheological behavior characteristics of MWCNT-TiO2/EG (40%–60%) hybrid nanofluid affected by temperature, concentration, and shear rate: An experimental and statistical study and a neural network simulating. Phys A Stat Mech Its Appl. 2020;553:124061. 10.1016/j.physa.2019.124061.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Kazemi I, Sefid M, Afrand M. A novel comparative experimental study on rheological behavior of mono & hybrid nanofluids concerned Graphene and silica nano-powders: characterization, stability and viscosity measurements. Powder Technol. 2020;366:216–29. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.02.010.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Ma M, Zhai Y, Yao P, Li Y, Wang H. Effect of surfactant on the rheological behavior and thermophysical properties of hybrid nanofluids. Powder Technol. 2021;379:373–83. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.10.089.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Lee J, Chen Y, Liang H, Kim S. Temperature-dependent rheological behavior of nanofluids rich in carbon-based nanoparticles. J Mol Liq. 2021;325:114659. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114659.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Dalkılıç AS, Açıkgöz Ö, Küçükyıldırım BO, Eker AA, Lüleci B, Jumpholkul C, et al. Experimental investigation on the viscosity characteristics of water based SiO2-graphite hybrid nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2018;97:30–8. 10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2018.07.007.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Sekhar YR, Sharma KV. Study of viscosity and specific heat capacity characteristics of water-based Al2O3 nanofluids at low particle concentrations. J Exp Nanosci. 2015;10(2):86–102. 10.1080/17458080.2013.796595.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Bahrami M, Akbari M, Karimipour A, Afrand M. An experimental study on rheological behavior of hybrid nanofluids made of iron and copper oxide in a binary mixture of water and ethylene glycol: non-Newtonian behavior . Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2016;79:231–7. 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2016.07.015.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Zhao TH, Khan MI, Chu YM. Artificial neural networking (ANN) analysis for heat and entropy generation in flow of non‐Newtonian fluid between two rotating disks. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2021. 10.1002/mma.7310.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Afrand M, Nadooshan AA, Hassani M, Yarmand H, Dahari M. Predicting the viscosity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/water nanofluid by developing an optimal artificial neural network based on experimental data. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2016;77:49–53. 10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2016.07.008.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Nguyen Q, Ghorbani P, Bagherzadeh SA, Malekahmadi O, Karimipour A. Performance of joined artificial neural network and genetic algorithm to study the effect of temperature and mass fraction of nanoparticles dispersed in ethanol. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2020. 10.1002/mma.6688.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Shahsavar A, Khanmohammadi S, Afrand M, Goldanlou AS, Rosatami S. On evaluation of magnetic field effect on the formation of nanoparticles clusters inside aqueous magnetite nanofluid: An experimental study and comprehensive modeling. J Mol Liq. 2020;312:113378. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113378.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Çolak AB. A novel comparative analysis between the experimental and numeric methods on viscosity of zirconium oxide nanofluid: Developing optimal artificial neural network and new mathematical model. Powder Technol. 2021;381:338–51. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.12.053.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Sodeifian G, Niazi Z. Prediction of CO2 absorption by nanofluids using artificial neural network modeling. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2021;123:105193. 10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105193.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Wahab A, Khan MA, Hassan A. Impact of Graphene nanofluid and phase change material on hybrid photovoltaic thermal system: Exergy analysis. J Clean Prod. 2020;277:123370. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123370.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Zheng Y, Zhang X, Shahsavar A, Nguyen Q, Rostami S. Experimental evaluating the rheological behavior of ethylene glycol under Graphene nanosheets loading. Powder Technol. 2020;367:788–95. 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.04.039.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Hamze S, Cabaleiro D, Maré T, Vigolo B, Estellé P. Shear flow behavior and dynamic viscosity of few-layer Graphene nanofluids based on propylene glycol-water mixture. J Mol Liq. 2020;316:113875. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113875.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Bakhtiari R, Kamkari B, Afrand M, Abdollahi A. Preparation of stable TiO2-Graphene/Water hybrid nanofluids and development of a new correlation for thermal conductivity. Powder Technol. 2021;385:466–77. 10.1016/j.powtec.2021.03.010.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Nadooshan AA, Eshgarf H, Afrand M. Measuring the viscosity of Fe3O4-MWCNTs/EG hybrid nanofluid for evaluation of thermal efficiency: Newtonian and non-Newtonian behavior. J Mol Liq. 2018;253:169–77. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.012.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Malekahmadi O, Kalantar M, Nouri-Khezrabad M. Effect of carbon nanotubes on the thermal conductivity enhancement of synthesized hydroxyapatite filled with water for dental applications: experimental characterization and numerical study. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;144(6):2109–26. 10.1007/s10973-021-10593-w.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Shahsavani E, Afrand M, Kalbasi R. Experimental study on rheological behavior of water–ethylene glycol mixture in the presence of functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;131(2):1177–85. 10.1007/s10973-017-6711-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Abidi A, Jokar Z, Allahyari S, Sadigh FK, Sajadi SM, Firouzi P, et al. Improve thermal performance of Simulated-Body-Fluid as a solution with an ion concentration close to human blood plasma, by additive Zinc Oxide and its composites: ZnO/Carbon Nanotube and ZnO/Hydroxyapatite. J Mol Liq. 2021;342:117457. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117457.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Ibrahim M, Saeed T, Chu, YM, Ali HM, Cheraghian G, Kalbasi R. Comprehensive study concerned graphene nano-sheets dispersed in ethylene glycol: Experimental study and theoretical prediction of thermal conductivity. Powder Technol. 2021;386(9):51–9. 10.1016/j.powtec.2021.03.028.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] García A, Culebras M, Collins MN, Leahy JJ. Stability and rheological study of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose and alginate suspensions as binders for lithium ion batteries. J Appl Polym Sci. 2018;135(17):46217. 10.1002/app.46217.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Phuoc TX, Massoudi M, Chen RH. Viscosity and thermal conductivity of nanofluids containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes stabilized by chitosan. Int J Therm Sci. 2011;50(1):12–8. 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2010.09.008.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Shahsavar A, Salimpour MR, Saghafian M, Shafii MB. Effect of magnetic field on thermal conductivity and viscosity of a magnetic nanofluid loaded with carbon nanotubes. J Mech Sci Technol. 2016;30(2):809–15. 10.1007/s12206-016-0135-4.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Alsarraf J, Malekahmadi O, Karimipour A, Tlili I, Karimipour A, Ghashang M. Increase thermal conductivity of aqueous mixture by additives Graphene nanoparticles in water via an experimental/numerical study: Synthesise, characterization, conductivity measurement, and neural network modeling. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2020;118:104864. 10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104864.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Sun C, Taherifar S, Malekahmadi O, Karimipour A, Karimipour A, Bach QV. Liquid paraffin thermal conductivity with additives tungsten trioxide nanoparticles: synthesis and propose a new composed approach of fuzzy logic/artificial neural network. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46:2543–52. 10.1007/s13369-020-05151-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Bhattacharjee S. DLS and zeta potential–what they are and what they are not? J Controlled Rel. 2016;235:337–51. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] ASHRAE. 2015 Ashrae handbook; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Jeong J, Li C, Kwon Y, Lee J, Kim SH, Yun R. Particle shape effect on the viscosity and thermal conductivity of ZnO nanofluids. Int J Refrig. 2013;36(8):2233–41. 10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2013.07.024.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Namburu PK, Kulkarni DP, Misra D, Das DK. Viscosity of copper oxide nanoparticles dispersed in ethylene glycol and water mixture. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2007;32(2):397–402. 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2007.05.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Sundar LS, Singh MK, Sousa AC. Investigation of thermal conductivity and viscosity of Fe3O4 nanofluid for heat transfer applications. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2013;44:7–14. 10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2013.02.014.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Yu W, Xie H, Chen L, Li Y. Investigation of thermal conductivity and viscosity of ethylene glycol based ZnO nanofluid. Thermochim Acta. 2009;491(1–2):92–6. 10.1016/j.tca.2009.03.007.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Bashirnezhad K, Bazri S, Safaei MR, Goodarzi M, Dahari M, Mahian O, et al. Viscosity of nanofluids: a review of recent experimental studies. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2016;73:114–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2016.02.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Ahammed N, Asirvatham LG, Wongwises S. Effect of volume concentration and temperature on viscosity and surface tension of Graphene–water nanofluid for heat transfer applications. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;123(2):1399–409. 10.1007/s10973-015-5034-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Khodadadi H, Toghraie D, Karimipour A. Effects of nanoparticles to present a statistical model for the viscosity of MgO-Water nanofluid. Powder Technol. 2019;342:166–80. 10.1016/j.powtec.2018.09.076.Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Nguyen Q, Rizvandi R, Karimipour A, Malekahmadi O, Bach QV. A novel correlation to calculate thermal conductivity of aqueous hybrid graphene oxide/silicon dioxide nanofluid: synthesis, characterizations, preparation, and artificial neural network modeling. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;45(11):9747–58. 10.1007/s13369-020-04885-w.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Karimipour A, Ghasemi S, Darvanjooghi MH, Abdollahi A. A new correlation for estimating the thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of CuO/liquid paraffin nanofluid using neural network method. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2018;92:90–9. 10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2018.02.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[70] Shahsavar A, Khanmohammadi S, Karimipour A, Goodarzi M. A novel comprehensive experimental study concerned synthesizes and prepare liquid paraffin-Fe3O4 mixture to develop models for both thermal conductivity & viscosity: a new approach of GMDH type of neural network. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2019;131:432–41. 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.11.069.Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Toghraie D, Sina N, Jolfaei NA, Hajian M, Afrand M. Designing an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to predict the viscosity of Silver/Ethylene glycol nanofluid at different temperatures and volume fraction of nanoparticles. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2019;534:122142. 10.1016/j.physa.2019.122142.Suche in Google Scholar

[72] Du C, Nguyen Q, Malekahmadi O, Mardani A, Jokar Z, Babadi E, et al. Thermal conductivity enhancement of nanofluid by adding multiwalled carbon nanotubes: Characterization and numerical modeling patterns. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2020. 10.1002/mma.6466.Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Li Y, Moradi I, Kalantar M, Babadi E, Malekahmadi O, Mosavi A. Synthesis of new dihybrid nanofluid of TiO2/MWCNT in water–ethylene glycol to improve mixture thermal performance: preparation, characterization, and a novel correlation via ANN based on orthogonal distance regression algorithm. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;144(6):2587–603. 10.1007/s10973-020-10392-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Karimipour A, Malekahmadi O, Karimipour A, Shahgholi M, Li Z. Thermal conductivity enhancement via synthesis produces a new hybrid mixture composed of copper oxide and multi-walled carbon nanotube dispersed in water: experimental characterization and artificial neural network modeling. Int J Thermophys. 2020;41(8):116. 10.1007/s10765-020-02702-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[75] Jabbari F, Rajabpour A, Saedodin S. Viscosity of carbon nanotube/water nanofluid. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;135(3):1787–96. 10.1007/s10973-018-7458-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[76] Cheraghian G, Afrand M. Nanotechnology for drilling operations. In Emerging nanotechnologies for renewable energy. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2021. p. 135–48. 10.1016/B978-0-12-821346-9.00008-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Alqaed S, Almehmadi FA, Mustafa J, Husain S, Cheraghian G. Effect of nano phase change materials on the cooling process of a triangular lithium battery pack. J Energy Storage. 2022;51(9):104326. 10.1016/j.est.2022.104326.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Saeed Alqaed et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon

- Effects of nano-SiO2 modification on rubberised mortar and concrete with recycled coarse aggregates

- Mechanical and microscopic properties of fiber-reinforced coal gangue-based geopolymer concrete

- Effect of morphology and size on the thermodynamic stability of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Experiment and molecular dynamics calculation

- Mechanical performance of a CFRP composite reinforced via gelatin-CNTs: A study on fiber interfacial enhancement and matrix enhancement

- A practical review over surface modification, nanopatterns, emerging materials, drug delivery systems, and their biophysiochemical properties for dental implants: Recent progresses and advances

- HTR: An ultra-high speed algorithm for cage recognition of clathrate hydrates

- Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites

- A highly sensitive nanobiosensor based on aptamer-conjugated graphene-decorated rhodium nanoparticles for detection of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells

- Progressive collapse performance of shear strengthened RC frames by nano CFRP

- Core–shell heterostructured composites of carbon nanotubes and imine-linked hyperbranched polymers as metal-free Li-ion anodes

- A Galerkin strategy for tri-hybridized mixture in ethylene glycol comprising variable diffusion and thermal conductivity using non-Fourier’s theory

- Simple models for tensile modulus of shape memory polymer nanocomposites at ambient temperature

- Preparation and morphological studies of tin sulfide nanoparticles and use as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of rhodamine B and phenol

- Polyethyleneimine-impregnated activated carbon nanofiber composited graphene-derived rice husk char for efficient post-combustion CO2 capture

- Electrospun nanofibers of Co3O4 nanocrystals encapsulated in cyclized-polyacrylonitrile for lithium storage

- Pitting corrosion induced on high-strength high carbon steel wire in high alkaline deaerated chloride electrolyte

- Formulation of polymeric nanoparticles loaded sorafenib; evaluation of cytotoxicity, molecular evaluation, and gene expression studies in lung and breast cancer cell lines

- Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders

- Influence of loading voltage, domain ratio, and additional load on the actuation of dielectric elastomer

- Thermally induced hex-graphene transitions in 2D carbon crystals

- The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study

- Molecular dynamics study of deformation mechanism of interfacial microzone of Cu/Al2Cu/Al composites under tension

- Nanocolloid simulators of luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic windows

- Compressive strength and anti-chloride ion penetration assessment of geopolymer mortar merging PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 using RBF–BP composite neural network

- Effect of 3-mercapto-1-propane sulfonate sulfonic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone on the growth of cobalt pillar by electrodeposition

- Dynamics of convective slippery constraints on hybrid radiative Sutterby nanofluid flow by Galerkin finite element simulation

- Preparation of vanadium by the magnesiothermic self-propagating reduction and process control

- Microstructure-dependent photoelectrocatalytic activity of heterogeneous ZnO–ZnS nanosheets

- Cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of molybdenum and tungsten disulphide on human bronchial cells

- Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica

- Chemically reactive Maxwell nanoliquid flow by a stretching surface in the frames of Newtonian heating, nonlinear convection and radiative flux: Nanopolymer flow processing simulation

- Nonlinear dynamic and crack behaviors of carbon nanotubes-reinforced composites with various geometries

- Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its therapeutic efficacy against colon cancer

- Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer

- Homotopic simulation for heat transport phenomenon of the Burgers nanofluids flow over a stretching cylinder with thermal convective and zero mass flux conditions

- Incorporation of copper and strontium ions in TiO2 nanotubes via dopamine to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility

- Mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of starch films incorporated with chitosan nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete

- Glucose-responsive nanogels efficiently maintain the stability and activity of therapeutic enzymes

- Tunning matrix rheology and mechanical performance of ultra-high performance concrete using cellulose nanofibers

- Flexible MXene/copper/cellulose nanofiber heat spreader films with enhanced thermal conductivity

- Promoted charge separation and specific surface area via interlacing of N-doped titanium dioxide nanotubes on carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B

- Elucidating the role of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mitigating the disease of the eggplant caused by Phomopsis vexans, Ralstonia solanacearum, and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

- An implication of magnetic dipole in Carreau Yasuda liquid influenced by engine oil using ternary hybrid nanomaterial

- Robust synthesis of a composite phase of copper vanadium oxide with enhanced performance for durable aqueous Zn-ion batteries

- Tunning self-assembled phases of bovine serum albumin via hydrothermal process to synthesize novel functional hydrogel for skin protection against UVB

- A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets

- Lightweight and hydrophobic Ni/GO/PVA composite aerogels for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding

- Research on the auxetic behavior and mechanical properties of periodically rotating graphene nanostructures

- Repairing performances of novel cement mortar modified with graphene oxide and polyacrylate polymer

- Closed-loop recycling and fabrication of hydrophilic CNT films with high performance

- Design of thin-film configuration of SnO2–Ag2O composites for NO2 gas-sensing applications

- Study on stress distribution of SiC/Al composites based on microstructure models with microns and nanoparticles

- PVDF green nanofibers as potential carriers for improving self-healing and mechanical properties of carbon fiber/epoxy prepregs

- Osteogenesis capability of three-dimensionally printed poly(lactic acid)-halloysite nanotube scaffolds containing strontium ranelate

- Silver nanoparticles induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and late non-canonical autophagy in HT-29 colon cancer cells

- Preparation and bonding mechanisms of polymer/metal hybrid composite by nano molding technology

- Damage self-sensing and strain monitoring of glass-reinforced epoxy composite impregnated with graphene nanoplatelet and multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Thermal analysis characterisation of solar-powered ship using Oldroyd hybrid nanofluids in parabolic trough solar collector: An optimal thermal application

- Pyrene-functionalized halloysite nanotubes for simultaneously detecting and separating Hg(ii) in aqueous media: A comprehensive comparison on interparticle and intraparticle excimers

- Fabrication of self-assembly CNT flexible film and its piezoresistive sensing behaviors

- Thermal valuation and entropy inspection of second-grade nanoscale fluid flow over a stretching surface by applying Koo–Kleinstreuer–Li relation

- Mechanical properties and microstructure of nano-SiO2 and basalt-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete

- Characterization and tribology performance of polyaniline-coated nanodiamond lubricant additives

- Combined impact of Marangoni convection and thermophoretic particle deposition on chemically reactive transport of nanofluid flow over a stretching surface

- Spark plasma extrusion of binder free hydroxyapatite powder

- An investigation on thermo-mechanical performance of graphene-oxide-reinforced shape memory polymer

- Effect of nanoadditives on the novel leather fiber/recycled poly(ethylene-vinyl-acetate) polymer composites for multifunctional applications: Fabrication, characterizations, and multiobjective optimization using central composite design

- Design selection for a hemispherical dimple core sandwich panel using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods

- Improving tensile strength and impact toughness of plasticized poly(lactic acid) biocomposites by incorporating nanofibrillated cellulose

- Green synthesis of spinel copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) nanoparticles and their toxicity

- The effect of TaC and NbC hybrid and mono-nanoparticles on AA2024 nanocomposites: Microstructure, strengthening, and artificial aging

- Excited-state geometry relaxation of pyrene-modified cellulose nanocrystals under UV-light excitation for detecting Fe3+

- Effect of CNTs and MEA on the creep of face-slab concrete at an early age

- Effect of deformation conditions on compression phase transformation of AZ31

- Application of MXene as a new generation of highly conductive coating materials for electromembrane-surrounded solid-phase microextraction

- A comparative study of the elasto-plastic properties for ceramic nanocomposites filled by graphene or graphene oxide nanoplates

- Encapsulation strategies for improving the biological behavior of CdS@ZIF-8 nanocomposites

- Biosynthesis of ZnO NPs from pumpkin seeds’ extract and elucidation of its anticancer potential against breast cancer

- Preliminary trials of the gold nanoparticles conjugated chrysin: An assessment of anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of a nanoformulated flavonoid

- Effect of micron-scale pores increased by nano-SiO2 sol modification on the strength of cement mortar

- Fractional simulations for thermal flow of hybrid nanofluid with aluminum oxide and titanium oxide nanoparticles with water and blood base fluids

- The effect of graphene nano-powder on the viscosity of water: An experimental study and artificial neural network modeling

- Development of a novel heat- and shear-resistant nano-silica gelling agent

- Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic

- Entropy production simulation of second-grade magnetic nanomaterials flowing across an expanding surface with viscidness dissipative flux

- Enhancement in structural, morphological, and optical properties of copper oxide for optoelectronic device applications

- Aptamer-functionalized chitosan-coated gold nanoparticle complex as a suitable targeted drug carrier for improved breast cancer treatment

- Performance and overall evaluation of nano-alumina-modified asphalt mixture

- Analysis of pure nanofluid (GO/engine oil) and hybrid nanofluid (GO–Fe3O4/engine oil): Novel thermal and magnetic features

- Synthesis of Ag@AgCl modified anatase/rutile/brookite mixed phase TiO2 and their photocatalytic property

- Mechanisms and influential variables on the abrasion resistance hydraulic concrete

- Synergistic reinforcement mechanism of basalt fiber/cellulose nanocrystals/polypropylene composites

- Achieving excellent oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of TiB2–B4C/carbon aerogel composites by quick-gelation and mechanical mixing

- Microwave-assisted sol–gel template-free synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles obtained from South African coal fly ash

- Pulsed laser-assisted synthesis of nano nickel(ii) oxide-anchored graphitic carbon nitride: Characterizations and their potential antibacterial/anti-biofilm applications

- Effects of nano-ZrSi2 on thermal stability of phenolic resin and thermal reusability of quartz–phenolic composites

- Benzaldehyde derivatives on tin electroplating as corrosion resistance for fabricating copper circuit

- Mechanical and heat transfer properties of 4D-printed shape memory graphene oxide/epoxy acrylate composites

- Coupling the vanadium-induced amorphous/crystalline NiFe2O4 with phosphide heterojunction toward active oxygen evolution reaction catalysts

- Graphene-oxide-reinforced cement composites mechanical and microstructural characteristics at elevated temperatures

- Gray correlation analysis of factors influencing compressive strength and durability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced geopolymer mortar

- Preparation of layered gradient Cu–Cr–Ti alloy with excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity

- Recovery of Cr from chrome-containing leather wastes to develop aluminum-based composite material along with Al2O3 ceramic particles: An ingenious approach

- Mechanisms of the improved stiffness of flexible polymers under impact loading

- Anticancer potential of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using a battery of in vitro tests

- Review Articles

- Proposed approaches for coronaviruses elimination from wastewater: Membrane techniques and nanotechnology solutions

- Application of Pickering emulsion in oil drilling and production

- The contribution of microfluidics to the fight against tuberculosis

- Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements

- Synthesis and encapsulation of iron oxide nanorods for application in magnetic hyperthermia and photothermal therapy

- Contemporary nano-architectured drugs and leads for ανβ3 integrin-based chemotherapy: Rationale and retrospect

- State-of-the-art review of fabrication, application, and mechanical properties of functionally graded porous nanocomposite materials

- Insights on magnetic spinel ferrites for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia applications

- A review on heterogeneous oxidation of acetaminophen based on micro and nanoparticles catalyzed by different activators

- Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems

- Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials

- Efficacious nanomedicine track toward combating COVID-19

- A review of the design, processes, and properties of Mg-based composites

- Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes

- Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based polymer composites: Fundamentals and applications

- Recent progress and challenges in plasmonic nanomaterials

- Apoptotic cell-derived micro/nanosized extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration

- Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review

- Framework materials for supercapacitors

- An overview on the reproductive toxicity of graphene derivatives: Highlighting the importance

- Antibacterial nanomaterials: Upcoming hope to overcome antibiotic resistance crisis

- Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites

- A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics

- Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials

- Recent developments in tensile properties of friction welding of carbon fiber-reinforced composite: A review

- Comprehensive review of the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer with additive of nano-SiO2

- Perspectives in biopolymer/graphene-based composite application: Advances, challenges, and recommendations

- Graphene-based nanocomposite using new modeling molecular dynamic simulations for proposed neutralizing mechanism and real-time sensing of COVID-19

- Nanotechnology application on bamboo materials: A review

- Recent developments and future perspectives of biorenewable nanocomposites for advanced applications

- Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery

- 3D printing customized design of human bone tissue implant and its application

- Design, preparation, and functionalization of nanobiomaterials for enhanced efficacy in current and future biomedical applications

- A brief review of nanoparticles-doped PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite for OLED and OPV

- Nanotechnology interventions as a putative tool for the treatment of dental afflictions

- Recent advancements in metal–organic frameworks integrating quantum dots (QDs@MOF) and their potential applications

- A focused review of short electrospun nanofiber preparation techniques for composite reinforcement

- Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: A review

- Latest developments in the upconversion nanotechnology for the rapid detection of food safety: A review

- Strategic applications of nano-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: Benefits and bottlenecks

- Molecular dynamics application of cocrystal energetic materials: A review

- Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine

- Cutting-edge development in waste-recycled nanomaterials for energy storage and conversion applications

- Biological applications of ternary quantum dots: A review

- Nanotherapeutics for hydrogen sulfide-involved treatment: An emerging approach for cancer therapy

- Application of antibacterial nanoparticles in orthodontic materials

- Effect of natural-based biological hydrogels combined with growth factors on skin wound healing

- Nanozymes – A route to overcome microbial resistance: A viewpoint

- Recent developments and applications of smart nanoparticles in biomedicine

- Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications

- Interfacial interactions and reinforcing mechanisms of cellulose and chitin nanomaterials and starch derivatives for cement and concrete strength and durability enhancement: A review

- Diamond-like carbon films for tribological modification of rubber

- Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) modified cement-based materials: A systematic review

- Recent research progress and advanced applications of silica/polymer nanocomposites

- Modeling of supramolecular biopolymers: Leading the in silico revolution of tissue engineering and nanomedicine

- Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics

- Biogenic synthesis of palladium nanoparticles: New production methods and applications

- A comprehensive review of nanofluids with fractional derivatives: Modeling and application

- Electrospinning of marine polysaccharides: Processing and chemical aspects, challenges, and future prospects

- Electrohydrodynamic printing for demanding devices: A review of processing and applications

- Rapid Communications

- Structural material with designed thermal twist for a simple actuation

- Recent advances in photothermal materials for solar-driven crude oil adsorption

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of MWCNT dispersion effect on the elastic modulus of flexible PDMS/MWCNT nanocomposites

- Mechanical, morphological, and fracture-deformation behavior of MWCNTs-reinforced (Al–Cu–Mg–T351) alloy cast nanocomposites fabricated by optimized mechanical milling and powder metallurgy techniques

- Flammability and physical stability of sugar palm crystalline nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic sugar palm starch/poly(lactic acid) blend bionanocomposites

- Glutathione-loaded non-ionic surfactant niosomes: A new approach to improve oral bioavailability and hepatoprotective efficacy of glutathione

- Relationship between mechano-bactericidal activity and nanoblades density on chemically strengthened glass

- In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation

- Research on a mechanical model of magnetorheological fluid different diameter particles

- Nanomechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–wood–plastic composites

- Investigative properties of CeO2 doped with niobium: A combined characterization and DFT studies

- Miniaturized peptidomimetics and nano-vesiculation in endothelin types through probable nano-disk formation and structure property relationships of endothelins’ fragments

- N/S co-doped CoSe/C nanocubes as anode materials for Li-ion batteries

- Synergistic effects of halloysite nanotubes with metal and phosphorus additives on the optimal design of eco-friendly sandwich panels with maximum flame resistance and minimum weight

- Octreotide-conjugated silver nanoparticles for active targeting of somatostatin receptors and their application in a nebulized rat model

- Controllable morphology of Bi2S3 nanostructures formed via hydrothermal vulcanization of Bi2O3 thin-film layer and their photoelectrocatalytic performances

- Development of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-loaded folate receptor-targeted nanoparticles for prostate cancer treatment

- Enhancement of the mechanical properties of HDPE mineral nanocomposites by filler particles modulation of the matrix plastic/elastic behavior

- Effect of plasticizers on the properties of sugar palm nanocellulose/cinnamon essential oil reinforced starch bionanocomposite films

- Optimization of nano coating to reduce the thermal deformation of ball screws

- Preparation of efficient piezoelectric PVDF–HFP/Ni composite films by high electric field poling

- MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon