Abstract

Hydrophobic cellulosic composites with the nano form of metal oxides possess good absorptive and adsorptive potentials. Native cellulose was regenerated, benzylated, crosslinked and blended with TiO2 nanoparticles to absorb toluene, xylene, chloroform, kerosene and petrol. The composite was fully characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission emission microscopy (TEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The effect of crosslinker, catalyst and time of absorption was investigated. The FTIR shows stretch and bend vibrations of hydroxyl (-OH), alkyl (-CH), aromatic double bond (C=C) for benzyl cellulose while the appearance of new peaks at 816, 769 and 726 cm−1 for Ti-O stretching vibrations confirms the successful synthesis of the composite. The SEM images revealed the transformation of foam-like appearance of benzyl cellulose to a solidified mass after TiO2 compositing. Enhanced oil absorption was seen as the amount of the aluminum sulfate catalyst was doubled as a high Qmax of 24.16, 25.81, 27.22, 24.03 and 24.43 was obtained when the amount of catalyst used was doubled.

1 Introduction

Cellulose is a biopolymeric raw material that is heavily used in the textile, construction, paper and pharmaceutical industries (1, 2) for the production of valuable cellulose-based products in the form of threads or fibers, films and stable microspheres for industrial and domestic use (3, 4). Benzylated celluloses are an interesting set of hydrophobic materials with unique applications as packaging materials, membranes (5, 6) and rheology modifiers with improved surface properties. The benzylation of cellulose increases its plasticity by substituting its hydroxyl group with non-polar benzyl groups which reduces the level of hydrogen bonding in the polymeric state of cellulose.

Titanium oxide is a unique material with a direct band gap (3.07 eV) and large excitation binding energy of 60 meV with long-term chemical stability when exposed to acidic and basic compounds (7). It is widely used in near-UV emission, gas sensors, transparent conductor and piezoelectric applications (8, 9). Titanium oxide nanoparticles have potential applications in various areas including optical, piezoelectric and gas sensing and they also exhibit high catalytic efficiency and strong adsorption ability (10, 11).

Areas which experience oil spillage are characterized with heavy pollution index which affect drinking water, plants, animals and humans that inhabit the oil environment (12). Water pollution by petroleum, spent lubricants and greases is a major challenge to oil producing countries of the world, therefore there is a need to synthesize smart materials with enhanced oil absorptive abilities that can be easily disposed and reused (13). Oil absorbing polymers are crosslinked three-dimensional hydrophobic networks with good swelling properties. The different oil adsorbents which are already in use for clean up purposes at regions with pronounced oil pollution include polypropylene, polyesters, polyurethanes sheets and foams are difficult to store after use while the long chain alkyl acrylate polymers have a tendency to exist in their crystalline state, a property that reduces their oil absorbing capacity (14). The aim of this research is to synthesize new cellulose-based biopolymer composites with good absorbency that can be reused and disposed of properly.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of crosslinked regenerated benzyl cellulose

A 10 g of cellulose was dissolved in 50 ml of 8% sodium hydroxide and 50 ml of 12% urea for 10 min. This suspension was cooled to below −12°C, and stirred vigorously while thawing at ambient temperature until a clear cellulose solution was achieved. Benzyl chloride was added under continuous stirring, after which the temperature was increased to 70°C. After 4 h, the temperature was decreased to room temperature. The benzyl cellulose polymer was then precipitated by pouring the solution into methanol and water mixture (4:1). This final suspension was neutralized with acetic acid, filtered off, washed with the water and methanol mixture and dried at 50°C for 48 h (7, 15).

2.2 Synthesis of crosslinked RBC and nanoTiO2 composite

A stock dispersion of TiO2 was prepared by dispersing TiO2 nanoparticles (2 g/l) in water through a combination of mechanical mixing and sonication. The TiO2 solution was then crosslinked with the benzyl cellulose by mixing them in the presence of 1.5 g adipic acid dissolved in 10 ml glycerol and aluminum sulfate (0.1 and 0.2 g) as the catalyst. The mixture was sonicated until well dispersed and free from agglomeration. The pH of each solution was adjusted using NaOH and HCl (16).

2.3 Oil absorbency over water

A quantity of about 0.02 g of dried oil-absorbent composite with known weight (m1) was put into the filter bag and immersed in xylene, toluene, petrol, diesel and kerosene, respectively, at room temperature after a predetermined time (12 h is needed for full oil absorbency). The filter bag with the composite sample (m1) was immersed in a mixture solvent (oil/water=3/1, v/v) under stirring. After a predetermined time, the sample bag was lifted and drained for 3 min; the sample was immediately taken out and weighed (17). This weight was also marked as m2. The oil absorbencies were average values of three repeated absorption test procedures.

The oil absorbency was calculated by the following formula:

2.4 Oil desorption

A quantity of about 0.02 g of dried oil-absorbent composite weighed beforehand was put into a filter bag and immersed in the oils at room temperature for 12 h. The filter bag with the sample was lifted from the oil and drained for 3 min, the sample was immediately taken out, weighed, and the weight was recorded as m3. Afterward, the sample was immersed into 200 ml distilled ethanol for another 12 h and the filter bag with the sample was lifted from ethanol and drained for 3 min (18). The sample was immediately taken out, weighed, and the weight was recorded as m4. The oil desorption rate was calculated by the following formula:

3 Results and discussion

The presence of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups is seen at 3423 and 1729 cm−1, respectively. The stretching vibration of C-O-C of the anhydroglucose unit is seen at 1043 cm−1 while the peaks at 2916 and 2840 cm−1 represent the C-H stretch (19). Various bending vibrations were observed at 977, 821 and 724 cm−1 for the various CH2 groups in the cellulose biopolymer (8). The appearance of transmittance peaks at 1643 and 882 cm−1 confirms the presence of C=C stretch and bend of a phenyl group and the disappearance of peaks at 2800–2900 cm−1 further confirms the synthesis of a regenerated benzyl cellulose (9, 20). The hydroxyl and alkyl functional groups at 3462, 2913 and 2842 cm−1, respectively were also seen after benzylation of cellulose. After the synthesis of the benzyl cellulose and nano-TiO2 composite, the transmittance peaks at 2336 and 2354 cm−1 for cellulose and the benzylated cellulose reduces greatly while the appearance of new peaks at 816, 769 and 726 cm−1 for Ti-O stretching vibrations confirms the successful synthesis of the composite (21) (Figure 1).

Infrared spectra of cellulose, benzyl cellulose and benzyl cellulose-TiO2.

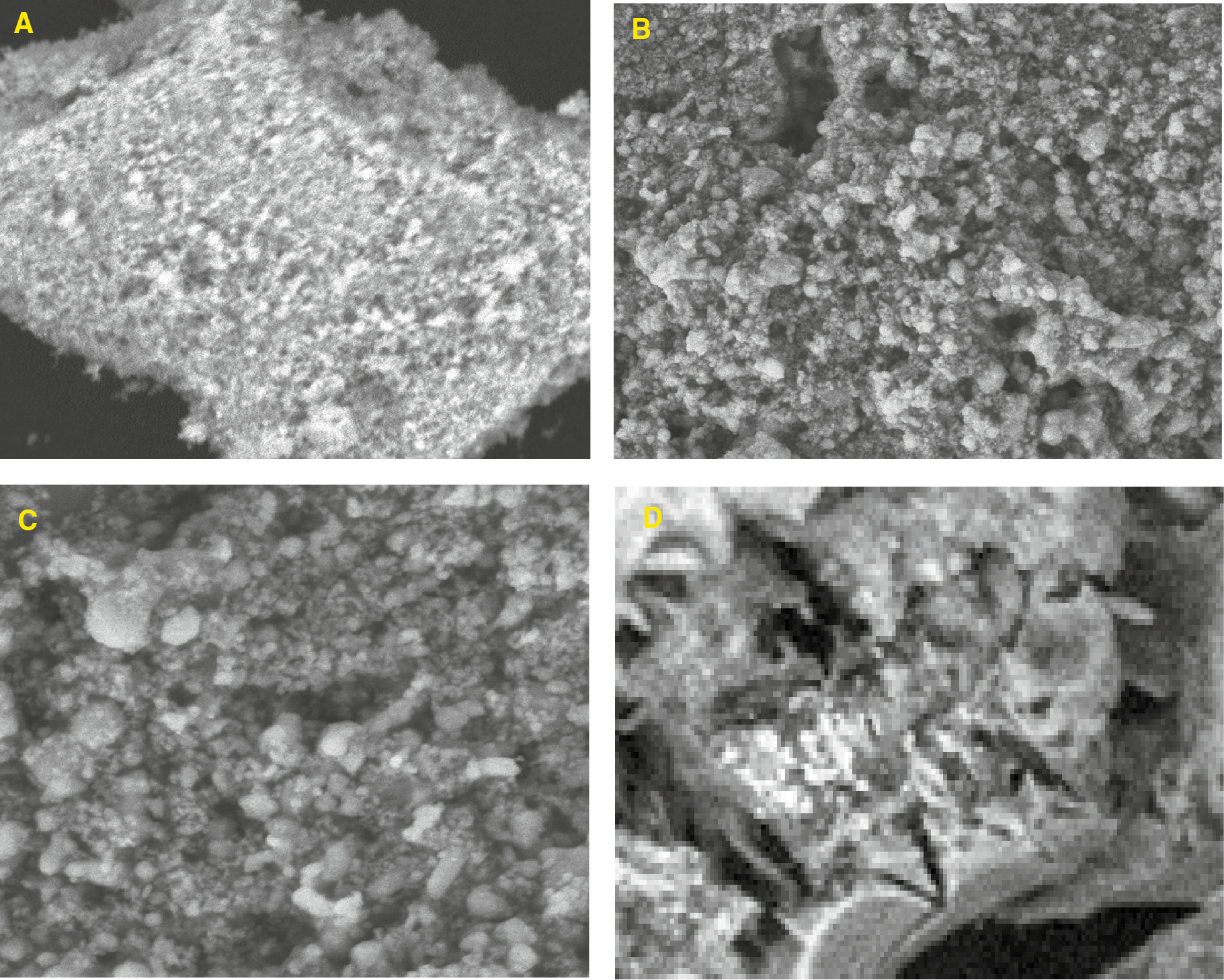

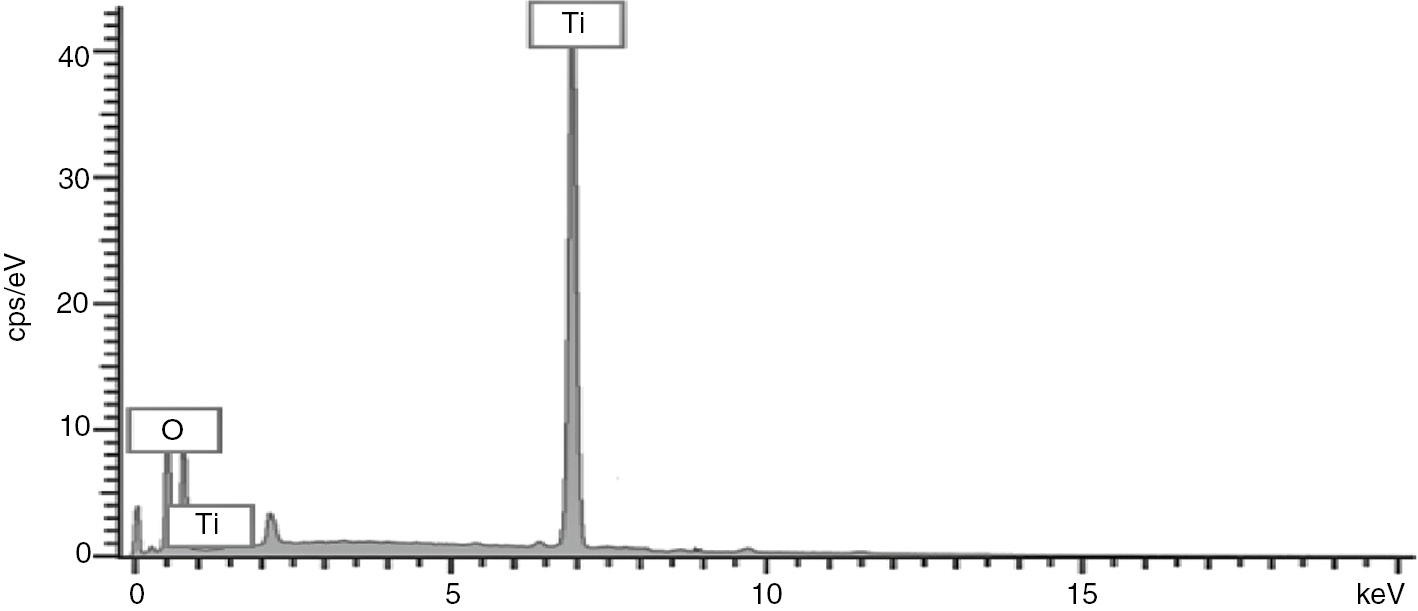

The SEM images in Figure 2 shows different morphological features which differentiates cellulose from benzyl cellulose. The cellulose isolated, which looks like an amorphous matter with a loose foam structure, was transformed into a benzylated form which resembles foam covered with solid bubbles and irregularly sized cavities. From Figures 3–8, after compositing with TiO2, the composite solidifies into a solid hydrophobic structure with a more open cavity. From the SEM photograph, the major thing which fascinates the observer is the disappearance of the ruggedness of the benzyl cellulose surface to form a composite with a much smoother surface and well arranged cavities (22, 23). The composite appears to be more tightly held at the surface as a result of the crosslinking effect. This information from the SEM results show that the composite is fit for absorbing both small and large molecules in their liquid phases (11, 24). The energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) which gives information about the elemental constituents of composite materials also confirms the successful binding of TiO2 to the benzyl surface. The peak at 7 keV reveals the presence of titanium in the composite.

SEM image of (A) cellulose (B) and (C) benzyl cellulose at different magnifications (D) benzyl cellulose-TiO2 nanoparticles composite.

EDX of benzyl cellulose-TiO2 nanoparticles.

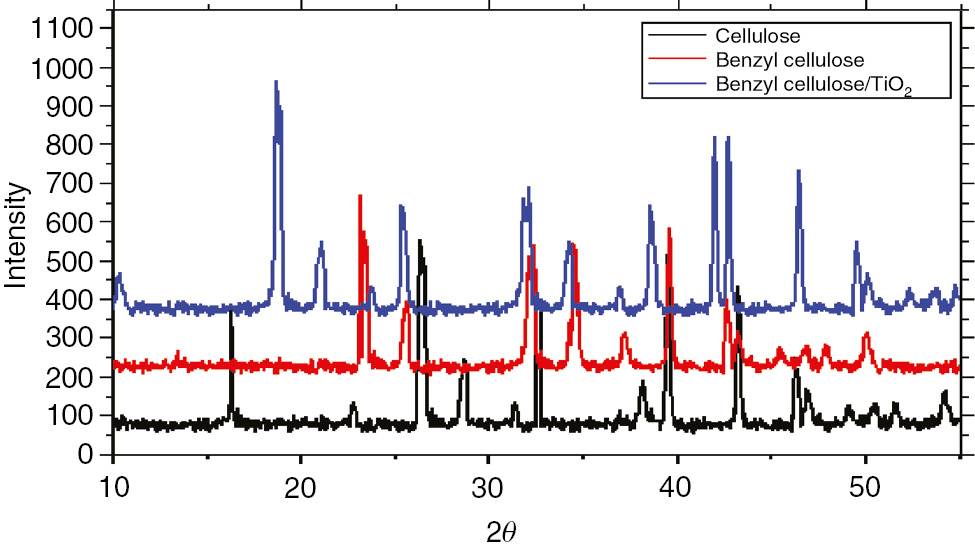

The XRD pattern of cellulose, benzyl cellulose and benzyl cellulose-TiO2.

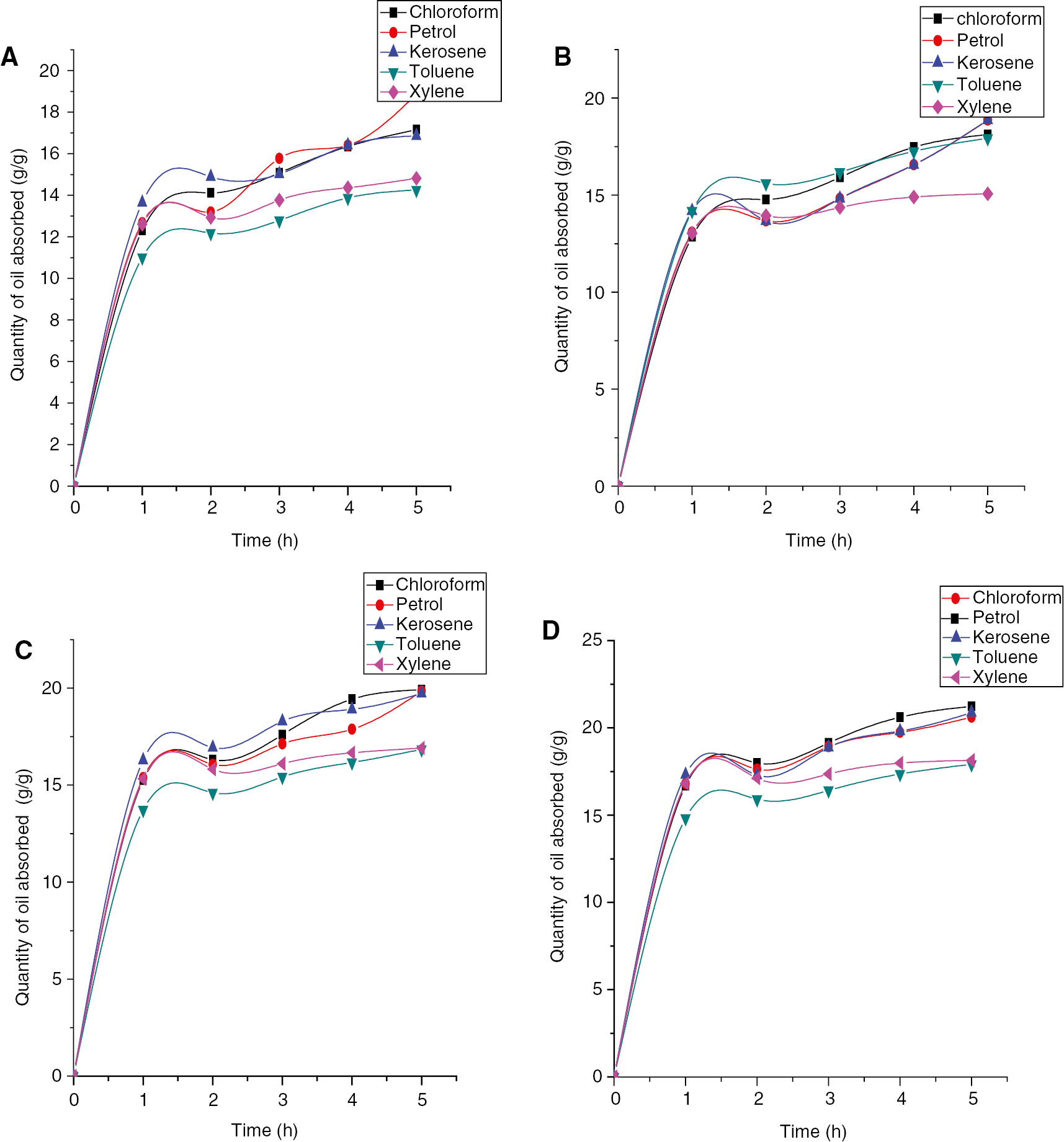

Absorption profile of benzyl cellulose-TiO2 crosslinked with (A) adipic acid-water (B) adipic acid-glycerol (C) adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate catalyst (0.1 g) (D) adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate catalyst (0.2 g).

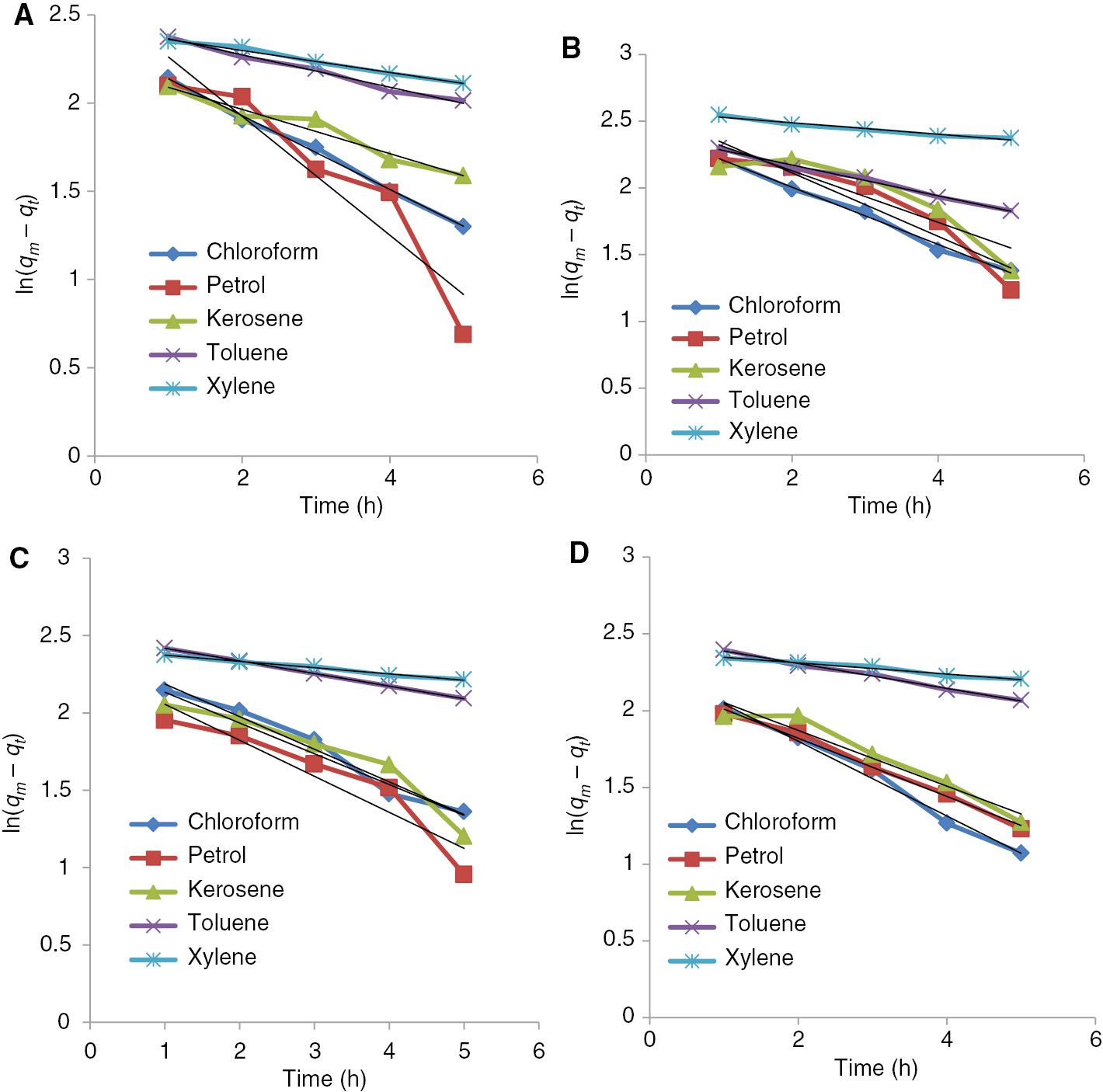

First order absorption kinetics of benzyl cellulose-TiO2 crosslinked with (A) adipic acid-water (B) adipic acid-glycerol (C) adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate catalyst (0.1 g) (D) adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate catalyst (0.2 g).

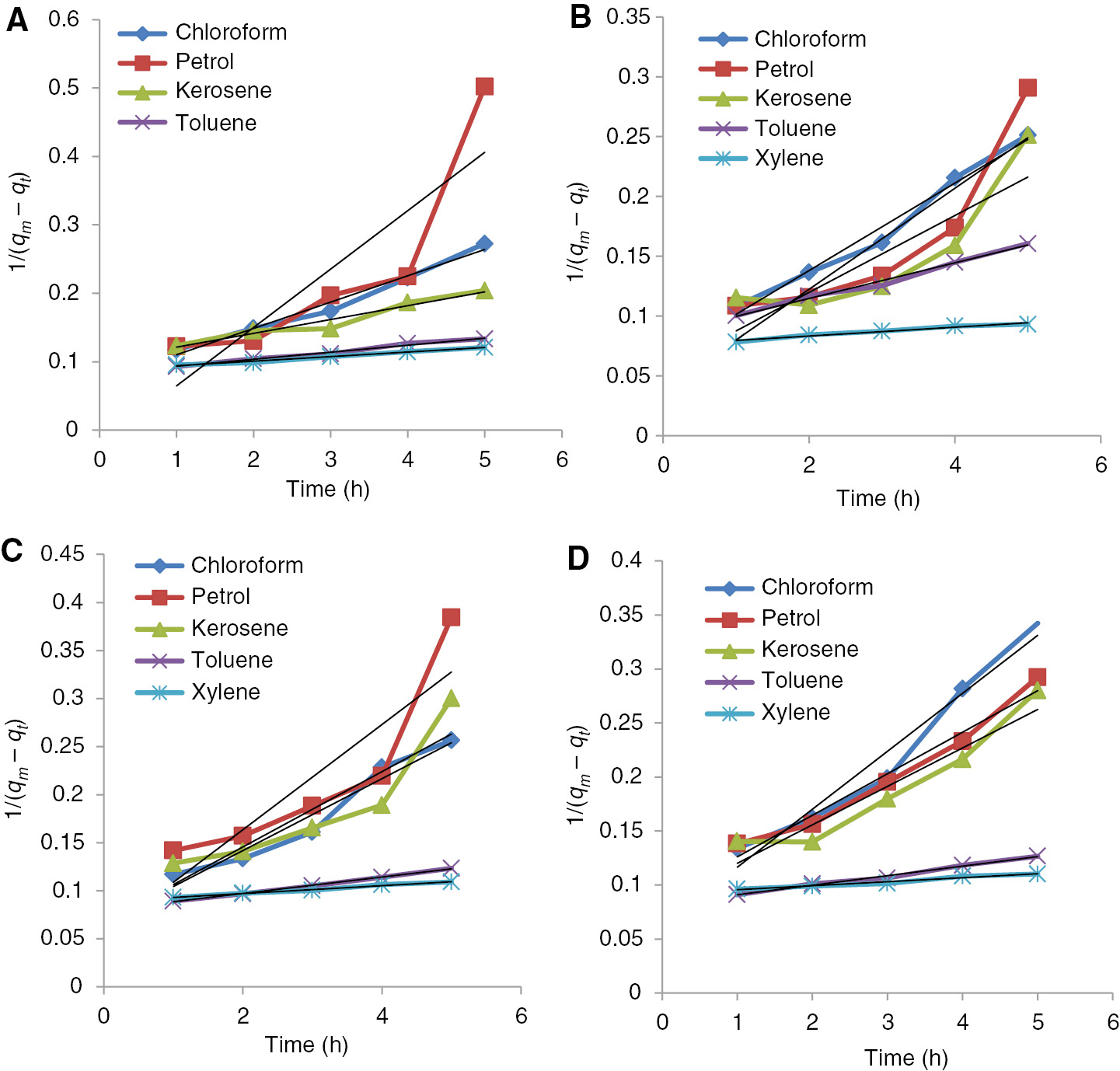

Second order absorption kinetics of benzyl cellulose-TiO2 crosslinked with (A) adipic acid-water (B) adipic acid-glycerol (C) adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate catalyst (0.1 g) (D) adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate catalyst (0.2 g).

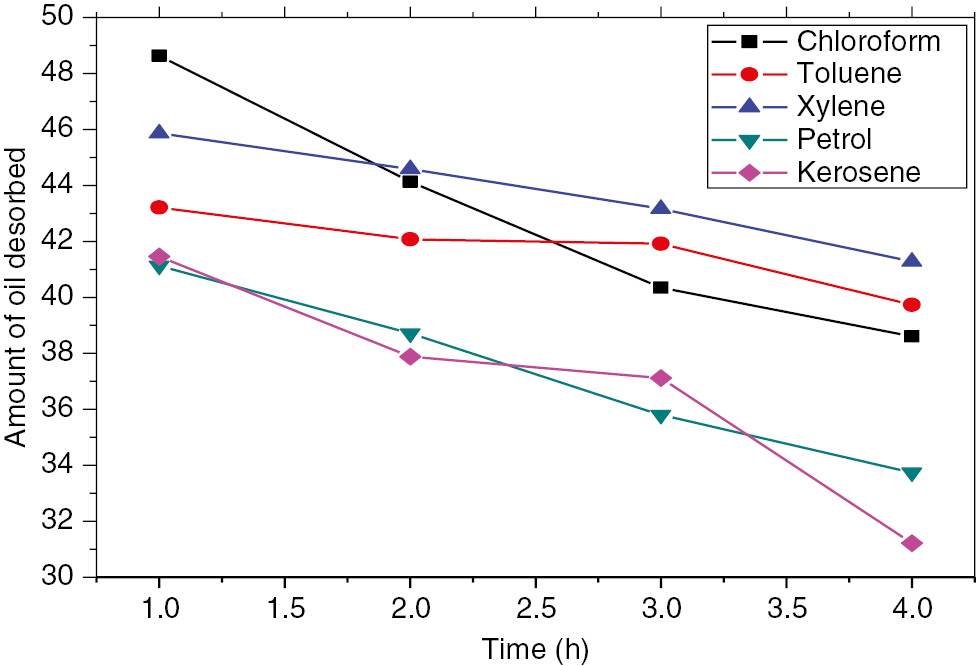

The oil desorption profile.

The peaks at 2θ=13°, 23°, 26°, 33.5° and 39° typical for cellulose I corresponds to (101), (002), (030) and (040), respectively, while the peaks at 2θ=23°, 33°, 40° with corresponding crystallographic planes at (200), (220) and (222) confirms the synthesis of benzyl cellulose (25, 26). The appearance of peaks at 18°, 21°, 39° and 46.5° confirms the presence of TiO2 in the final composite formed.

The figures below show the oil absorption profile of regenerated benzylated cellulose crosslinked with adipic acid-water, adipic acid-glycerol, and adipic acid-glycerol-aluminum sulfate. The quantity of oil absorbed by the hydrophobic matrices increases as the retention time increases. In general, light oils tend to be easily absorbed and desorbed from hydrophobic composites while the heavy oils take time to be absorbed into the pores of oil absorbing polymers; rather the heavy oils stays adsorbed at the surfaces due to their bulky nature (17). Maximum absorption was obtained with kerosene while minimum absorption was obtained with toluene across all the composites prepared. The oil absorbency increased rapidly at the beginning due to the solvation of the network chains. The main driving force of this process was the change in the free energies of mixing and elastic deformation. However, the swelling was limited, that is, with the time increasing the absorption rate became slower and finally reached saturation (18).

For chloroform, the maximum quantity of oil absorbed increased from 20.83 to 23.81 when crosslinked with Al2(SO)4, 22.64–24.195 for toluene, 23.09–26.08 for xylene, 20.85–22.44 for petrol and 21.76–23.17 for kerosene. The improved oil absorption ability might be as a result of the pore regulation of the benzyl cellulose and titanium oxide composite by the positive charge effect of Al3+ on the surface of the composites. The pores tighten up by the Ti4+ and Al3+ interactions and enables the composite to hold more of the oils within its pores. The amount of oil absorbed across all the composite crosslinked at different conditions which ranged from 11.01 to 21.24 shows that the composite is oleophilic (oil loving). Enhanced oil absorption was seen as the amount of the aluminum sulfate catalyst was doubled. A high Qmax of 24.16, 25.81, 27.22, 24.03 and 24.43 g/g was obtained when the amount of catalyst used was doubled; hence, aluminum sulfate can be used to improve the oil absorption capacity of hydrophobic cellulosic composites. From previous work, octadecyl acrylate copolymer which is also an oil absorbent had an oil absorption capacity in the range of 15–21 g/g while isooctyl acrylate copolymer had oil absorption capacity in the range of 18–26 g/g (27).

Absorption of oil onto the absorbent was studied in terms of the kinetics of the absorption mechanism by using two models. Assuming that the absorption kinetic process obeyed the first-order model, the kinetics equation was:

where qt (g/g) was the amount of oil absorbed at time t (h), k1 was the rate constant of the first order equation and qm was the maximum amount of absorption (g/g). The absorption rate constant k1 could be determined experimentally by plotting of ln (qe −qt ) versus t.

Similarly, if the absorption obeyed the second-order kinetics model, kinetics equation became following form:

where k2 (g/g·h) was the rate constant of the second order equation. The rate constant k2 could be obtained by plotting 1/(qe−qt) versus t. k1 and k2 for the oils used were calculated from the slopes. The correlation coefficients for the first-order model were better than the second-order model, indicating that the first order model was more suitable to describe the absorption process (18, 27).

Chloroform absorption for all the crosslinked benzylated cellulose-TiO2 followed first order kinetics except the adipic acid-glycerol crosslinked while petrol absorption followed the first order for all the composites without any exception. The absorption kinetics of kerosene and toluene as shown in the Table 1 followed by second order kinetics except for the absorption by the adipic acid-water crosslinked composite while that of xylene showed first order absorption with the catalytically crosslinked composite and second order absorption for the uncatalytically crosslinked composite.

The first and second order kinetics parameters for all the composites.

| First order | Second order | Qmax | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | k1 | R2 | k2 | |||

| a | Chloroform | 0.985 | 0.0625 | 0.7548 | 0.0854 | 20.83 |

| Petrol | 0.9846 | 0.0914 | 0.9797 | 0.0384 | 22.64 | |

| Kerosene | 0.9554 | 0.1256 | 0.9483 | 0.0203 | 23.09 | |

| Toluene | 0.9965 | 0.2088 | 0.9839 | 0.0067 | 20.85 | |

| Xylene | 0.8837 | 0.3368 | 0.9867 | 0.0103 | 21.76 | |

| b | Chloroform | 0.9532 | 0.0432 | 0.9812 | 0.0365 | 22.11 |

| Petrol | 0.9905 | 0.1156 | 0.7476 | 0.0321 | 24.16 | |

| Kerosene | 0.8602 | 0.1932 | 0.9890 | 0.0149 | 25.81 | |

| Toluene | 0.8805 | 0.2378 | 0.9619 | 0.0037 | 22.31 | |

| Xylene | 0.8926 | 0.2144 | 0.9861 | 0.0138 | 22.85 | |

| c | Chloroform | 0.9880 | 0.0404 | 0.7864 | 0.0548 | 23.81 |

| Petrol | 0.9999 | 0.0813 | 0.8151 | 0.0392 | 24.95 | |

| Kerosene | 0.8058 | 0.1991 | 0.9522 | 0.0374 | 26.08 | |

| Toluene | 0.9712 | 0.2108 | 0.9882 | 0.0041 | 22.44 | |

| Xylene | 0.9831 | 0.2329 | 0.9383 | 0.0086 | 23.17 | |

| d | Chloroform | 0.9658 | 0.0361 | 0.9619 | 0.0537 | 24.16 |

| Petrol | 0.9917 | 0.0816 | 0.9672 | 0.03850 | 25.81 | |

| Kerosene | 0.9393 | 0.1817 | 0.9425 | 0.0356 | 27.22 | |

| Toluene | 0.9631 | 0.2433 | 0.9630 | 0.0037 | 24.03 | |

| Xylene | 0.9917 | 0.1897 | 0.9915 | 0.0088 | 24.43 | |

(a) is adipic acid-water crosslinked composite, (b) is adipic acid-glycerol crosslinked composite, (c) is adipic acid-glycerol-0.1 g Al2(SO)4 crosslinked composite and (d) is adipic acid-glycerol-0.2 g Al2(SO)4 crosslinked composite.

3.1 Oil desorption rate

The desorption studies revealed the gradual release of the oil by the composites in ethanol and the amount of oil desorbed reduces with catalytic crosslinking. About 25% decrease was observed in the desorption rate of chloroform and kerosene after catalytic crosslinking while a 10% decrease was observed in toluene, xylene and petrol, respectively (18, 27).

4 Conclusion

The composite obtained from benzyl cellulose and TiO2 is a new material with good oil absorbency and can be used to mop up oil spillages in regions experiencing oil pollution. The aluminum sulfate used is a more economical catalyst that has caused an improvement in the absorbency properties of the composite on oils after being crosslinked.

References

1. Yakubu A, Umar TM, Mohammed SSD. Chemical modification of microcrystalline cellulose: improvement of barrier surface properties to enhance surface interactions with some synthetic polymers for biodegradable packaging material processing and applications in textile, food and pharmaceutical industry. Adv App Sci Res. 2011;2(6):532–40.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Biswas A, Saha BC, Lawton JW, Shogren RL, Willett JL. Process for obtaining cellulose acetate from agricultural by-products. Carb Pol. 2006;64(1):134–7.10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

3. Olatunji GA. The eighty-eight inaugural lecture, in Journeyto the Promised Land: The Travails of an Organic Chemist, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Yakubu A, Olatunji GA, Mamza, PA. Scanning electron microscopy and kinetic studies of ketene – acetylated wood/cellulose high-density polyethylene blends. Int J Carb Chem. 2012;2012:1–7.10.1155/2012/456491Suche in Google Scholar

5. Ramos LA, Frollini E, Koschella A, Heinze T. Benzylation of cellulose in the solvent dimethylsulfoxide/tetrabutyl ammonium fluoride trihydrate. Cellulose. 2005;12:607.10.1007/s10570-005-9007-2Suche in Google Scholar

6. Li MF, Sun SN, Xu F, Sun RC. Benzylation and characterization of cold NaOH/urea treated cellulose. Eur Polym J. 2011;47:1817.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2011.06.013Suche in Google Scholar

7. Sundman O, Gillgren T, Broström M. Homogenous benzylation of cellulose impact of different methods on product properties. Cell Chem Technol. 2015;49(9–10):745–55.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Qiuxiang Z, Ke Y, Wei B, Qingyan W, Feng X, Ziqiang Z, Ning D, Yan S. Synthesis, optical and field emission properties of three different ZnO nanostructures. Mater Lett. 2007;61:3890.10.1016/j.matlet.2006.12.064Suche in Google Scholar

9. Yuzhen L, Lin G, Huibin X, Lu D, Chunlei Y, Jiannong W, Weikun G, Shihe Y, Ziyu W. Low temperature synthesis and optical properties of small-diameter ZnO nanorods. J Appl Phys. 2006;99:114302.10.1063/1.2200408Suche in Google Scholar

10. Aneesh PM, Vanaja KA, Jayaraj MK. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles by hydrothermal method. Nanophotonics Mater. 2007;IV:6639.10.1117/12.730364Suche in Google Scholar

11. Singh RP, Shukla VK, Yadav RS, Sharma PK, Singh PK, Pandey AC. Extracellular synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticle using seaweeds of gulf of Mannar, India. Adv Mat Lett. 2011;2(4):313–7.10.5185/amlett.indias.204Suche in Google Scholar

12. Soliman FM, Yang W, Guo H, Shinger MI, Idris AM, Hassan ES. Synthesis and characterization of a high oil-absorbing poly (methyl methacrylate-butyl acrylate)/ATP-Fe3O4 magnetic composite material. Am J Polym Sci Technol. 2016;2(1):1–10.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Abdel-Azim A, Abdul-Raheim M, Atta AM, Brostow W, Datashvili T. Swelling and network parameters of crosslinked porous octadecyl acrylate copolymers as oil spill sorbers. e-Polymers. 2009;134:1–14.10.1515/epoly.2009.9.1.1592Suche in Google Scholar

14. Atta AM, El-Ghazaway RAM, Farag RK, Abdel-Azim AA. Crosslinked reactive macromonomers based on polyisobutylene and octadecyl acrylate copolymers as crude oil sorbers. React Funct Polym. 2006;66:931–43.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2006.01.001Suche in Google Scholar

15. Jamshid MR, Kamel EK, Ashkan H, Peyman PS. Effect of glycerol and stearic acid as plasticizer on physical properties of benzylated wheat straw. Iran J Chem Chem Eng. 2014;33(4):2014.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Nejati K, Rezvani Z, Pakizevand R. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and investigation of the ionic template effect on their size and shape. Int Nano Lett. 2011;1(2):75–81.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Atta AM, El-Ghazaway RAM, Farag RK, Abdel-Azim AA. Swelling and network parameters of oil sorbers based on alkyl acrylates and cinnamoyloxy ethyl methacrylate copolymers. J Polym Res. 2006;13:257–66.10.1007/s10965-005-9033-7Suche in Google Scholar

18. Rom M, Dutkiewicz J, Fryczkowska B, Fryczkowska R. The hydrophobisation of cellulose pulp. Fibre Text East Eur. 2007;15(5–6):64–5.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Meruvu H, Vangalapati M, Chippada SC, Bammidi SR. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles and its antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. Rasayan J Chem. 2011;4(1):217–22.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Zhong QP, Matijevic E. Preparation of uniform zinc oxide colloids by controlled double-jet precipitation. J Mater Chem. 1996;3:443.10.1039/jm9960600443Suche in Google Scholar

21. Hui Z, Deren Y, Xiangyang M, Yujie J, Jin X, Duanlin Q. Synthesis of flower-like ZnO nanostructures by an organic-free hydrothermal process. Nanotechnology. 2004;15:622.10.1088/0957-4484/15/5/037Suche in Google Scholar

22. Zhang J, Sun LD, Yin YL, Su HL, Liao CS, Yan CH. Control of ZnO morphology via a simple solution route. Chem Mater. 2002;14:4172.10.1021/cm020077hSuche in Google Scholar

23. Aneesh PM, Vanaja KA, Jayaraj MK. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles by hydrothermal method. Nanophotonic. Mater. 2007;IV:6639.10.1117/12.730364Suche in Google Scholar

24. Cai J, Kimura S, Wada M, Kuga S. Nanoporous cellulose as metal nanoparticles support. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:87–94.10.1021/bm800919eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Shin Y, Bae IT, Arey BW, Exarhos GJ. Facile stabilization of gold-silver alloy nanoparticles on cellulose nanocrystal. J Phys Chem. 2008;112:4844–8.10.1021/jp710767wSuche in Google Scholar

26. Shin Y, Bae IT, Arey BW, Exarhos GJ. Simple preparation and stabilization of nickel nanocrystals on cellulose nanocrystal. Mater Lett. 2007;61:3215–7.10.1016/j.matlet.2006.11.036Suche in Google Scholar

27. Liu H, Gao S, Cai J, He C, Mao J, Zhu T, Chen Z, Huang J, Meng K, Zhang K, Al-Deyab SS, Lai Y. Recent progress in fabrication and applications of superhydrophobic coating on cellulose based substrates. Materials. 2016;9(124):1–37.10.3390/ma9030124Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Full length articles

- Ultralight sponges of poly(para-xylylene) by template-assisted chemical vapour deposition

- Cryostructuring of polymer systems. 44. Freeze-dried and then chemically cross-linked wide porous cryostructurates based on serum albumin

- Macroporous polymer beads derived from a novel coporogen of polyethylene/dichlorobenzene

- Gas separation properties of Troeger’s base-bridged polyamides

- Catalytic crosslinking of a regenerated hydrophobic benzylated cellulose and nano TiO2 composite for enhanced oil absorbency

- On orientation memory in high density polyethylene – carbon nanofibers composites

- Comparative investigation of physical, mechanical and thermomechanical characterization of dental composite filled with nanohydroxyapatite and mineral trioxide aggregate

- Dissipative particle dynamics simulation on the self-assembly of linear ABC triblock copolymers under rigid spherical confinements

- Synthesis and characterization of cellulose acetate naphthoate with good ultraviolet and chemical resistance

- Thermal characterization and flammability of polypropylene containing sepiolite-APP combinations

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Full length articles

- Ultralight sponges of poly(para-xylylene) by template-assisted chemical vapour deposition

- Cryostructuring of polymer systems. 44. Freeze-dried and then chemically cross-linked wide porous cryostructurates based on serum albumin

- Macroporous polymer beads derived from a novel coporogen of polyethylene/dichlorobenzene

- Gas separation properties of Troeger’s base-bridged polyamides

- Catalytic crosslinking of a regenerated hydrophobic benzylated cellulose and nano TiO2 composite for enhanced oil absorbency

- On orientation memory in high density polyethylene – carbon nanofibers composites

- Comparative investigation of physical, mechanical and thermomechanical characterization of dental composite filled with nanohydroxyapatite and mineral trioxide aggregate

- Dissipative particle dynamics simulation on the self-assembly of linear ABC triblock copolymers under rigid spherical confinements

- Synthesis and characterization of cellulose acetate naphthoate with good ultraviolet and chemical resistance

- Thermal characterization and flammability of polypropylene containing sepiolite-APP combinations